1. Introduction

In machine learning, multi-view data involve multiple distinct sets of attributes (“views”) for a common set of observations. For example, a text document can be represented by different views, such as bag-of-words, topic models, or sentiment analysis. A multi-view latent space representation tries to project the original multi-view data into a lower and more meaningful space that is common to all views. Approaches such as Consensus PCA, Stepwise Common Principal Components (Stepwise CPCs), Generalized Canonical Correlation Analysis (GCCA), Latent Multi-view Subspace Clustering and Multi-View Clustering in Latent Embedding Space [1–5], to name just a few, try to capture underlying factors or concepts that characterize the data in the latent space while filtering out noise and redundancy. For multi-view clustering (MVC) applications, performing cluster analysis in the latent space generally results in more accurate and consistent cluster partitioning [6]. It is noteworthy that these approaches allow newly collected data (i.e. data that is not part of the data used to train/learn the model) to be embedded in the latent space, and thus are not limited to the purpose of multi-view clustering.

In the particular case where each view has the same attributes but is considered in a different context, the data is a multidimensional array of order 3 that can be thought of as a tensor. For example, an RGB image has three color channels: Red, Green and Blue, and each color channel is a two-dimensional matrix in which the intensity of the respective color is stored for each pixel. Non-negative Tensor Factorization (NTF) is a powerful latent space representation technique that is designed to analyze multidimensional arrays of order 3 or more. For example, color and spatial information of the image are captured by NTF non-negative factors, which can be used for various tasks such as image compression, enhancement, segmentation, classification and fusion [7].

Unfortunately, NTF cannot be applied to multi-view data when the views have heterogeneous content, such as a text document representation. Numerous algorithms have been proposed for this type of data, some of which have become popular in the machine learning community. For example, the MVLEARN package uses the Scikit-Learn API to make it easily accessible to Python users [8]. Nevertheless, none of the algorithms proposed in this package can benefit from the NTF approach, as a heterogeneous data structure is assumed.

Some methods first convert each view into a similarity matrix between the observations. Since all views refer to the same observations, the similarity matrices have the same shape regardless of the view they come from, resulting in a tensor of similarity matrices. MVC is performed on these similarity matrices, sometimes using tensor-based approaches, such as Essential Tensor Learning for Multi-view Spectral Clustering or Multi-view Clustering via Semi-non-negative Tensor Factorization [9,10]. However, these approaches cannot be applied to other tasks, such as data reduction. This is owing to the fact that the representations of such similarity matrices are not really a projection of the data from multiple views into a common latent space with a small number of common attributes, such as underlying factors or concepts.

As with all factorization methods, the factorization rank must be determined in advance [11,12]. However, non-negative factorization methods such as NMF or NTF are not subject to orthogonality constraints and can therefore create a new dimension by, for example, splitting some factors into two parts to achieve a better approximation. Therefore, finding the correct rank should not be as critical as in mixed signed factorization approaches such as SVD, where components with low variance tend to represent the noisy part of the data: a low rank leads to different mechanisms being intertwined in a single component, while a higher rank allows disentangling such mechanisms [13].

Despite their name, the NMF and NTF approaches are not limited to data with non-negative data. For example, mixed data can be split into its positive part and the absolute value of its negative part, resulting in two different non-negative views that can be analyzed by NTF [14].

In the context of heterogeneous views, we present in this article the Integrated Sources Model (ISM), which embeds each view into a common latent space. The embedded views have the same format and can be further analyzed by NTF. In addition to the NTF components, a view-mapping matrix is estimated to obtain an interpretable link between the dimensions of the latent space and the original attributes from each view.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

UCI Digits Data: The data can found at Datasets - Datasets - UCI Machine Learning Repository and contains 6 heterogenous views: 76 Fourier coefficients of the character shapes, 216 profile correlations, 64 Karhunen-Love coefficients, 240 pixel averages of the images from 2x3 windows, 47 Zernike moments and 6 morphological features, where each class contains 200 labeled examples.

Signature 915 Data: The data can be found at

https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/38/4/1015/6426077#supplementary-data in supplementary table S4 (list of 915 marker genes and corresponding cell types) and GEO Accession viewer (

nih.gov) (expression data). In 4 views corresponding to different patients, the expressions of 915 marker genes are measured across 16 different cell-types. In other words, this dataset contains 4 views of the 915 gene markers (one view per patient) measured in 16 different cell-types.

2.2. Methods

In this section, we present three workflows. The first workflow consists of training the ISM model to generate a latent space representation and view-mapping. The second workflow enables the projection of new observations obtained in multiple views into the latent space. The third workflow contains the detailed analysis steps for each example.

Workflow 1: Latent space representation and view-mapping

The training of the ISM model can be divided into 5 units as described in

Figure 1. The first 4 process units enable the discovery of the latent space in an “embedding” space. Once the latent space has been found, it is assimilated with the embedding space. During the fifth "straightening" unit, the latent space remains fixed, while the sequence of units 3, 4 and 2 is repeated to further parsimonize the view-mapping until the degree of sparsity remains unchanged. The sizes of the embedding space and the latent space are discussed in the section describing the third workflow.

Figure 1.

Training of the ISM model.

Figure 1.

Training of the ISM model.

Unit 1: Initialization

A non-negative matrix factorization is first performed on the matrix

of the

concatenated views

, resulting in the decomposition:

where

represents the transformed data, the columns of

contain the loadings of the

attributes across all views on each component,

is the embedding size and

is the total number of observations.

|

Unit 1 Initialization |

|

Unit 2: Parsimonization

The initial degree of sparsity in

is crucial to the embedding dimensions from being overly distorted between the different views during the embedding process, as will be seen in the next section. This is achieved by applying a hard-threshold to each column of the

matrix. The threshold is based on the reciprocal of the Herfindhal-Hirschman index [15], which provides an estimate of the number of non-negligible values in a non-negative vector. For columns with strongly positively skewed values, the use of the L2 norm for the estimate’s denominator can lead to excessively sparse factors, which in turn can lead to an overly large approximation error during embedding. Therefore, the estimate is multiplied by a coefficient whose default value was set at 0.8 after extensive testing with various data sets.

|

Unit 2 Parsimonization |

|

Unit 3: Embedding

and are further updated along each view, yielding matrices of common shape (number of observations factorization rank ) corresponding to the transformed views.

NMF multiplicative updates are used during view matching to leave the zeros in the primary

matrix unchanged. Further optimizations of the simplicial cones

for each view

are therefore limited to the non-zero loadings so that they remain tightly connected. This ensures that the transformed views

form a tensor. Multiplicative updates usually start with a linear rate of convergence, which becomes sublinear after a few hundred iterations [16]. By default, the number of iterations is set to 200 to ensure a reasonable approximation to each view, as required for the latent space representation described in the next section.

|

Unit 3 Embedding |

|

Unit 4: Latent space representation and view-mapping

The resulting tensor

is analyzed using NTF, which leads to the decomposition:

where

and

is the dimension of the latent space. The components

,

and

enable the reconstruction of the horizontal, lateral and frontal slices of the embedding tensor: the loadings of the views on each component are contained in the matrix

; the integrated multiple views, or

meta-scores, are contained in the matrix

; and the matrix

represents the latent space in the form of a simplicial cone contained in the embedding space. Finally, the view-mapping matrix

is updated by applying steps 3-8 of unit 4. Its sparsity is ensured by further applying the parsimonization unit 2.

|

Unit 4 Latent space representation & View-mapping |

|

Unit 5: Straightening

The sparsity of the view-mapping matrix

can be further optimized together with the meta-scores

and the view-loadings

by repeating units 3, 4 and 2 until the number of 0-entries in

remains unchanged. To achieve this, the embedding is restricted to the latent space defined by the simplicial cone formed by

. In this simplified embedding space,

becomes the Identity matrix

and remains fixed in the updating process of

and

. In other words, embedding and latent spaces are being assimilated during the straightening process.

|

Unit 5 Straightening |

|

Workflow 2: Projection of new observations

For new observations

comprising

views,

, ISM parameters

,

and view-mapping matrix

can be used to project

on the latent ISM components, as described in workflow 2.

|

Workflow 2 Projection of new observations |

|

Workflow 3: Data analysis

The data from the UCI Digits and Signature 915 datasets are analyzed using several alternative approaches: ISM, Multi-View Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MVMDS), NMF, NTF and Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Because PCA and NMF are not multi-view approaches, they are applied to the concatenated views. To facilitate interpretation, the transformed data is projected onto a 2D map before being subjected to k-means clustering, where k is the known number of classes. Within each cluster, the class that contains the majority of the points, i.e. the main class, is identified. If two clusters share the same main class, they are merged, unless they are not contiguous (ratio of the distance between the centroids to the intra-cluster distance between points > 1). In this case, the non-contiguous clusters are excluded because they are assigned to the same class, which should appear homogeneous in the representation. Similarly, any cluster that does not contain an absolute majority is not considered clearly representative of the class to which it is assigned and is excluded. A global purity index is then calculated for the remaining clusters. To enhance clarity, the clusters are visualized using 95% confidence ellipses, while the classes are represented using as distinct colors as possible.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is applied to the 2D map projection. MDS uses a simple metric objective to find a low-dimensional embedding that accurately represents the distances between points in the latent space [17]. MDS is therefore agnostic to the intrinsic clustering performances of the methods that we want to evaluate. Effective embedding methods, e.g., UMAP or t-SNE, are not as optimal for preserving the global geometric structure in the latent space [18]. For example, a resolution parameter needs to be defined for the UMAP embedding of single-cell data, whereby a higher resolution leads to a higher number of clusters. In addition, the subtle differences between some cell types from one family can be smoothed out if the dataset contains transcriptionally distinct cell types from multiple families, as is the case with immune cells (second dataset in the article).

In terms of the factorization rank, which must be determined in advance, ISM benefits from the advantages of the NMF and NTF components, where the selection of the correct rank should not be so critical, allowing the rank to be set to the number of known classes. However, the dimension of the ISM embedding space must also be determined during the discovery step, i.e. before the embedding and latent spaces are finally unified. This is done by inspecting the approximation error in the neighborhood of the chosen rank. The rank for PCA and MVMDS is set by inspecting the screeplot of the variance ratio.

The analysis of the Signature 915 data also examines the biological relevance of the distance between clusters in each latent multi-view space.

Detailed analysis steps are provided in workflow 3.

|

Workflow 3 Analysis steps |

|

3. Results

Workflow 3 contains detailed calculation steps for the purity index; it was applied on the two data sets.

3.1. UCI Digits Data

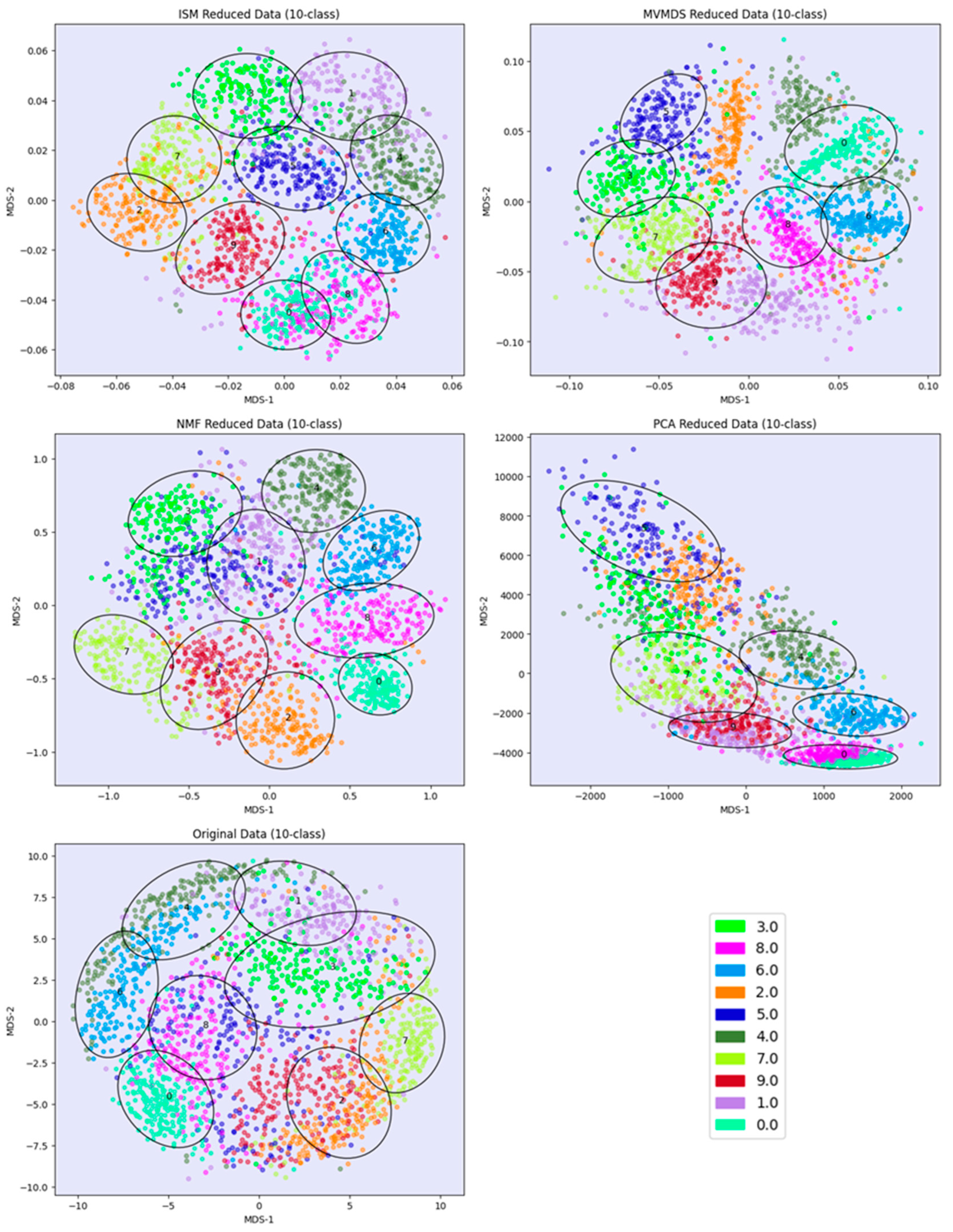

PCA and MVMDS use a 10-factorization rank. ISM uses a primary embedding of dimension 9 and a 10-factorization rank. The clusterings of the digits along ISM, Multi-View Multi Dimensional Scaling (MVMDS), NMF and PCA components are shown in 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of transformed data (

Figure 2). The Karhunen-Love coefficients contain data with mixed signs, so the corresponding view is split into its positive part and the absolute value of its negative part when applying the non-negative approaches ISM and NMF. The clustering based on the application of MDS on the concatenated views is also shown. A k-means clustering with 10 classes is performed for each approach to identify digit-specific clusters containing an absolute majority of a given digit. ISM is the only method that separates the 10 classes of digits, with some of the classes forming isolated clusters, and with a higher purity index than all other competing approach except NMF, which gives a slightly higher index than ISM (5.84 versus 5.81,

Table 1). However, the digits 5 and 3 are mixed together so that one less digit is recognized. This illustrates the complementarity between the number of recognized classes and the purity index.

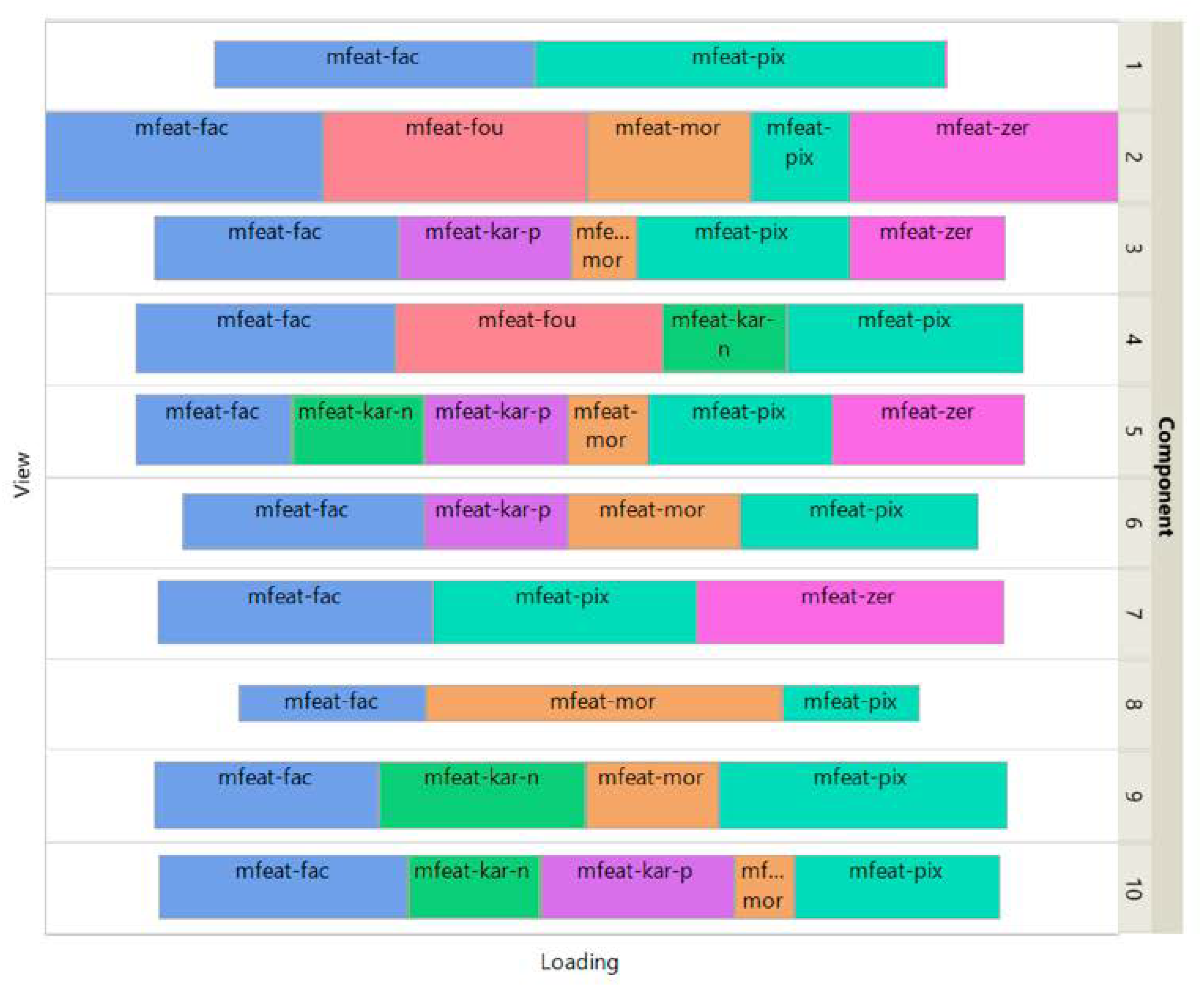

Figure 3 shows how the views affect the individual ISM components by using a treemap chart. For each component, each view corresponds to a rectangle within a rectangular display, where the size of the rectangle represents the loading of the view. It is noteworthy that some components are only supported by a few views, e.g., component 1 (2 views) and 8 (3 views), while others involve most views, e.g., component 5 (6 views). As each component is associated with a digit, this emphasizes the specifics and complementarity of the image representations that are dependent on the respective digit. It is also interesting to note that for some components, the loadings of the views are diametrically opposed to the respective number of attributes, e.g. for component 8 the view of 240 pixel averages has the lowest loading, while the view of 6 morphological features has the highest loading. This clearly shows that the views are evenly balanced regardless of their respective number of attributes when using ISM.

Table 1.

Number of found clusters and purity for 4 latent-space methods and using the concatenated data.

Table 1.

Number of found clusters and purity for 4 latent-space methods and using the concatenated data.

|

Method

|

Number of clusters

|

Purity

|

| ISM |

10 |

5.81 |

| MVMDS |

7 |

4.06 |

| NMF |

9 |

5.84 |

| PCA |

6 |

2.87 |

| Concatenated data |

8 |

3.34 |

Figure 2.

UCI Digits Data: clustering of digit images along ISM, Multi-View Multi Dimensional Scaling (MVMDS), NMF and PCA components in 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of transformed data. The left bottom view contains the MDS projection of the concatenated views.

Figure 2.

UCI Digits Data: clustering of digit images along ISM, Multi-View Multi Dimensional Scaling (MVMDS), NMF and PCA components in 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of transformed data. The left bottom view contains the MDS projection of the concatenated views.

Figure 3.

UCI Digits Data: treemap of ISM view weights.

Figure 3.

UCI Digits Data: treemap of ISM view weights.

3.2. Signature 915 Data

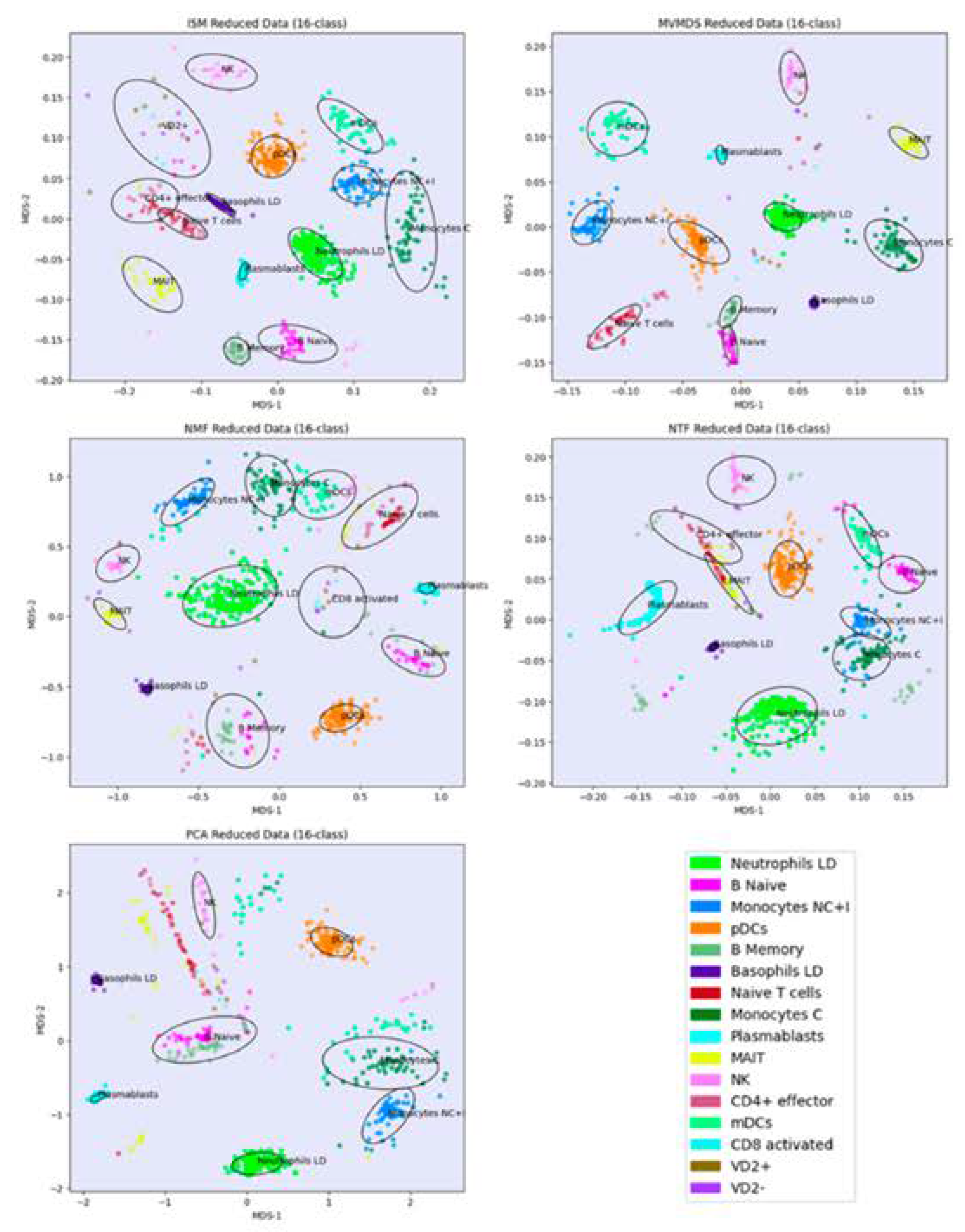

Prior to the analysis, each marker gene was normalized using the mean of the 4 highest expression values corresponding to the mean expression in the respective cell-type. PCA and MVMDS use a 10-factorization rank. ISM uses a primary embedding of dimension 16 and a 16-factorization rank. The clusterings of the marker genes along ISM, MVMDS, NMF, NTF and PCA components are shown in 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of the transformed data (

Figure 4). A k-means clustering with 16 classes is performed for each approach to identify cell type-specific clusters containing an absolute majority of the marker genes of a given cell type. ISM outperforms the other methods with 14 cell type-specific clusters, and with a higher purity index than any other approach (

Table 2). As seen in the example of the UCI digits, the NMF purity index is close to the ISM index (11.24 versus 11.46). However, the naïve B cells are divided into two groups on either side of the neutrophil LD cells, resulting in one less cell type being recognized.

Regarding the positioning of the clusters on the 2D map, MVMDS places monocyte C and monocyte NC+I opposite of each other, contrary to all other approaches and, more importantly, against biological intuition. The ISM method outperforms other methods on this dataset as it reveals a tight proximity between transcriptionally and functionally close cell types of the major immune cell families. Indeed, three cell types from the myeloid lineage, including monocytes C, monocytes NC+I and mDC, were grouped together. The same trend is observed for three cell types from the B cell family, where only ISM revealed close proximity of naïve B cells, memory B cells and plasmablasts, out of the five methods considered. The most challenging cell types were in the T cell family, where ISM was able to identify clusters for three cell types (CD4+ effectors, naïve T cells and VD+ gamma delta non-conventional T cells) and place them in close proximity. VD+ gamma delta non-conventional T cells have also some similarities with NK cells in terms of expression of some receptors, and only the ISM method was able to recognize both cell types and place them in close proximity to reveal their similarity. The ISM method was also able to capture some other subtle similarities between two types of dendritic cells, mDC and pDC, which correspond to antigen-presenting cells.

Figure 4.

Signature 915 Data: clustering of cell-type marker genes along ISM, MVMDS, NMF, NTF and PCA components in the 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of the transformed data.

Figure 4.

Signature 915 Data: clustering of cell-type marker genes along ISM, MVMDS, NMF, NTF and PCA components in the 2D scatterplots of the MDS projection of the transformed data.

Table 2.

Number of found clusters and purity for 5 latent-space methods and using the concatenated data.

Table 2.

Number of found clusters and purity for 5 latent-space methods and using the concatenated data.

|

Method

|

Number of clusters

|

Purity

|

| ISM |

14 |

11.46 |

| MVMDS |

12 |

11.19 |

| NMF |

13 |

8.78 |

| NTF |

11 |

8.39 |

| PCA |

8 |

6.68 |

| Concatenated data |

9 |

7.21 |

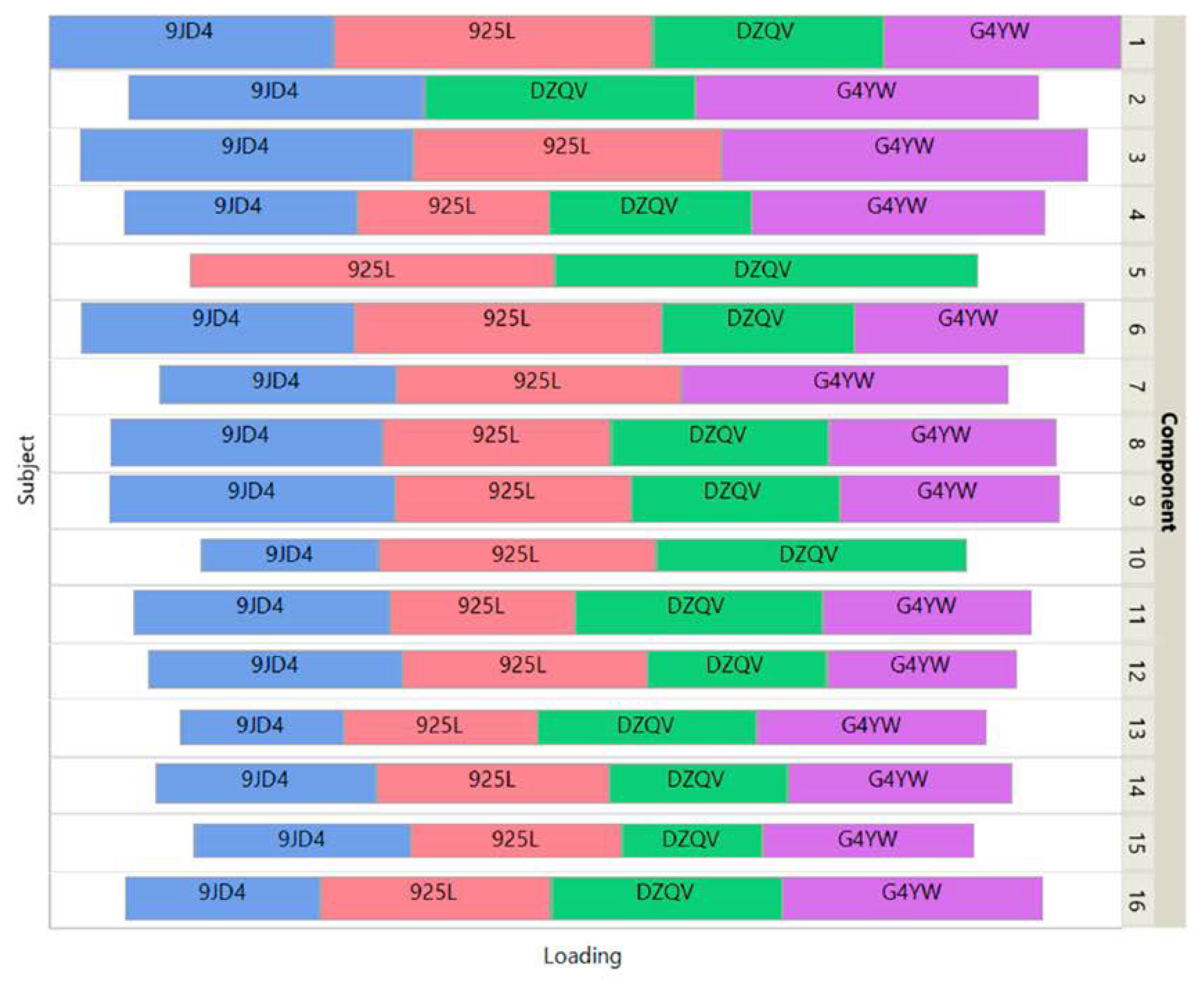

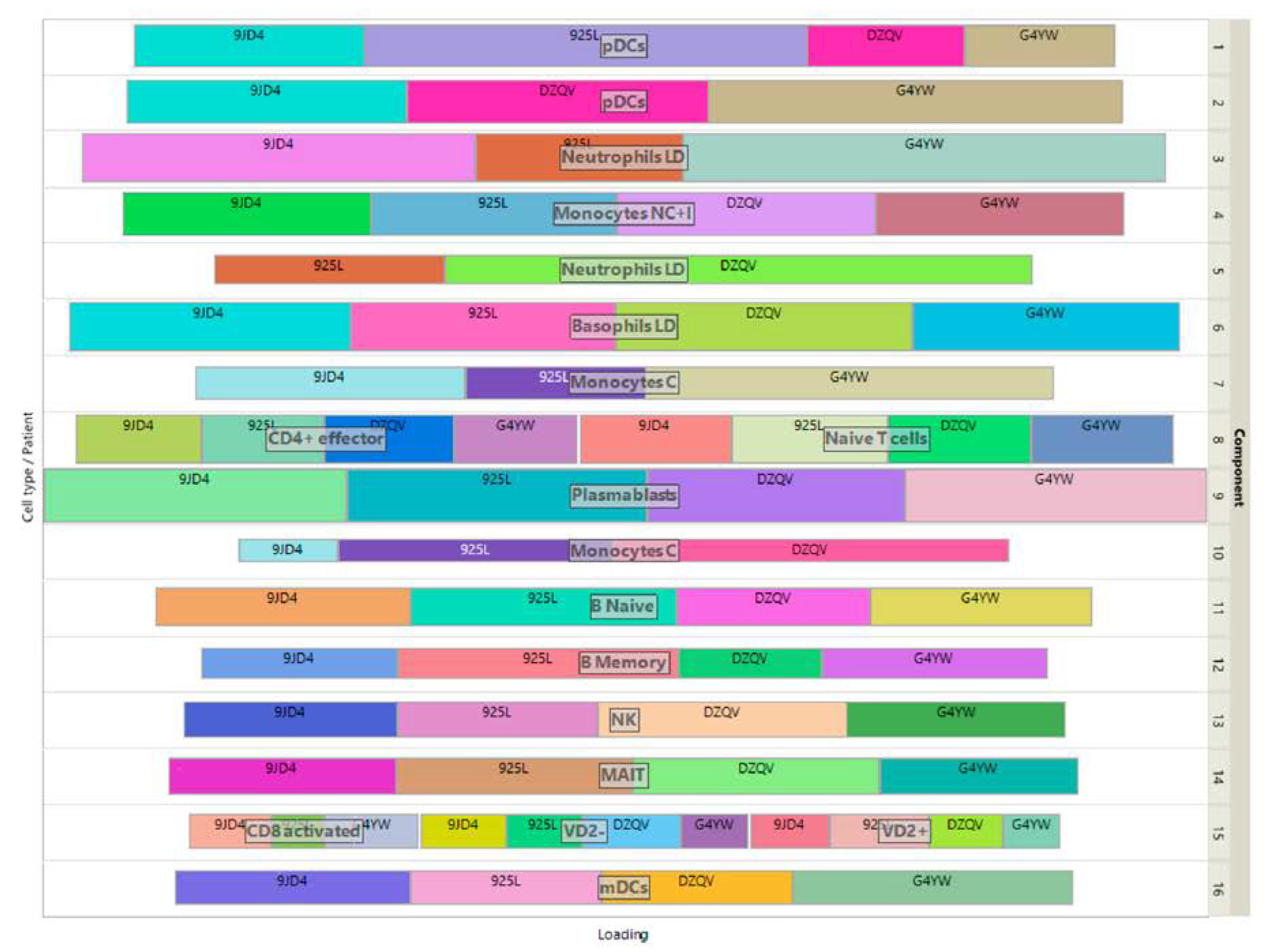

Figure 5 shows how the 4 patients impact the individual ISM components by using a treemap chart. For each component, each patient corresponds to a rectangle within a rectangular display, where the size of the rectangle represents the loading of the patient. In contrast to the UCI digits data, most components are supported by 3 patients (3 components) or 4 patients (11 components). Two components involve only 2 patients.

Figure 5.

Signature 915 Data: treemap of ISM view weights.

Figure 5.

Signature 915 Data: treemap of ISM view weights.

The loadings of the view-mapping matrix are shown in

Figure 6 by using a treemap chart. Recall that each attribute of this dataset is a combination of a patient and a cell-type, in which the expressions of 915 marker genes were measured. For each component, such a combination corresponds to a rectangle within a rectangular display, where the size of the rectangle represents the loading of the combination. ISM components 1 and 2 are both associated with the same cell type pDC, while component 15 is simultaneously associated with CD8-activated, VD2- and VD2+ cells. In the final clustering, the cluster comprising these 3 cell types has no main type and is therefore discarded, resulting in 13 identified cell-types.

Figure 6.

Signature 915 Data: treemap of ISM loadings of the view-mapping matrix.

Figure 6.

Signature 915 Data: treemap of ISM loadings of the view-mapping matrix.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, ISM is the first approach that allows heterogeneous views to be transformed into a three-dimensional array to which NTF can be applied to extract consistent information from all views. Other recent methods, such as Regularized Multi-Manifold NMF [19] or Multi-View Clustering in Latent Embedding Space [5], propose new algorithms that insert terms in the NMF loss function to minimize the difference between the consensus components and the view-specific components, thus circumventing the embedding in a three-dimensional array. However, these algorithms have yet to be adopted by the Machine Learning community and optimized in terms of performance and convergence. In contrast, ISM consists of a workflow of proven algorithms, NMF and NTF, which are already optimized in terms of performance and convergence. Thus, ISM provides the Machine Learning community with a powerful and scalable tool.

NMF and NTF are known to produce more interpretable and meaningful factors as they cannot cancel each other out due to the non-negativity of their loadings. Similarly, ISM, as a workflow involving NMF and NTF steps, produces latent factors whose interpretation is greatly facilitated thanks to the non-negativity of the attribute loadings that define them, as illustrated by the signature 915 data example.

Sparsity is an important element of the ISM workflow, which further facilitates the interpretation of latent factors. It is important to note that no parameter for sparsity needs to be defined, as the hard threshold calculation for latent factors is automatically selected as the reciprocal of the Herfindhal-Hirschman index. For factors with strongly positively skewed values, the use of the L2 norm for the denominator of the index can lead to excessively sparse factors, which in turn can lead to an overly large approximation error during embedding. Therefore, this threshold can be scaled down by a multiplicative factor to achieve a better mapping to each view, which can lead to greater consistency in the analysis, as long as the intrinsic nature of the embedding tensor is preserved, i.e. the embedding dimensions remain comparable in the different views. In our workflow implementation, the default value for the multiplicative factor was set to 0.8 after extensive testing with various data sets.

The embedding size is an additional parameter that allows ISM to be tuned to a desired level of specificity across views. A large embedding size, such as the factorization rank multiplied by the number of views, allows each view to find its specificities in some dimensions of the embedding. In contrast, a small embedding size, such as the factorization rank, leads to more consensual latent factors with attributes from different views due to the rarity of components in the latent space. This is in sharp contrast to other approaches to latent spaces such as GCCA or stepwise CPCs, which create a latent space that attempts to maximize the correspondence between views and filters out their specificities.

ISM intrinsic view loadings also enable the automatic weighting of the views within each latent factor. This allows the simultaneous analysis of views of very different sizes without the need for prior normalization to give each view the same importance, as is the case with Consensus PCA, for example.

It should be noted that the preliminary NMF in unit 1 of workflow 1 combines the data before applying NTF, which is reminiscent of the "attention" mechanism used in transformers before applying a light neural network [20]. This could explain why ISM can outperform NTF when applied to a multidimensional array, i.e. even if the data structure is suitable for the direct application of NTF, as shown by the clustering of marker genes achieved in the application example. This could also explain why, although NMF performance is close to ISM performance in terms of the purity index, ISM outperforms NMF in both examples in terms of number of recognized classes and, in the second example, by generating a better positioning of recognized cell types on the 2D map projection.

Like other latent space methods, ISM is not limited to the purpose of multi-view clustering. The ISM components, as well as the view-mapping matrix, can be used for data reduction on newly collected data (i.e. data that is not part of the data used to train/learn the model) by fixing these components in the ISM model.

Data reduction for newly collected data is still feasible even if some of the views contained in the training data are missing, as the ISM parameters are compartmentalized by view, in contrast to latent factors provided by other latent space factorization methods.

ISM is not limited to views with non-negative data. Each mixed-signed view can be split into its positive part and the absolute value of its negative part, resulting in two different non-negative views, similar to the scheme applied by NTF to centered data [14].

An important limitation of ISM and of other multi-view latent space approaches is the required availability of multi-view data for all observations in the training set. For financial or logistical reasons, a particular view may be missing in a subset of the observations, and this subset is in turn dependent on the view under consideration. We are currently evaluating a variant of ISM that can process multi-view data with missing views. In this approach, sets of views that have enough common observations are integrated with ISM separately. By using the model parameters, the transformation into the latent ISM space can be expanded to

all views over

all observations belonging to the set, resulting in much larger transformed views than the original intersection would allow. This

expansion process enables the integration of the ISM-transformed data from the different view sets, again using the ISM. For this reason, we call this variant the Integrated Latent Space Model, ILSM. Interestingly, a similar integrated latent space approach has already been proposed to study the influence of social networks on human behavior [21]. After masking a large number of views, the dataset of UCI digits was analyzed using ILSM. A more detailed description of the expansion process (Workflow S1,

Figure S1) and promising results (

Figure S2) can be found in the supplementary materials.

The ISM implementation relies on state-of-the-art algorithms that are already available in "off-the-shell" NMF and NTF packages (sklearn.decomposition.NMF — scikit-learn 1.4.0 documentation, adnmtf PyPI) and are invoked via a simple workflow implemented in a Jupyter Python notebook that is accessible to the vast majority of the Machine Learning community.

5. Conclusion

To illustrate the key benefits of ISM, we present some potential applications that are currently being evaluated and the results of which will be published in future articles.

In longitudinal clinical studies, where participants are followed up later in the study, the ISM model can be trained at baseline and applied to subsequent data to calculate meta-scores. The fact that the associated components are fully interpretable increases the appeal of ISM meta-scores to clinicians, in contrast to mixed-sign latent factors provided by other factorization methods.

Let’s consider complex multidimensional multi-omics data from one and the same set of cells (single cell technology). In fact, there is a growing amount of single-cell data corresponding to different molecular layers of the same cell. Data integration is a challenge as each modality can provide a different clustering stemming from a specific biological signal. Therefore, data integration and its projection into a space must (i) preserve the consensus between two clusterings and (ii) highlight the differences that each modality may bring. The ISM view loadings can address these two key requirements: Components with similar contributions from each molecular layer highlight a consensus that can be inferred from the clustering based on the ISM meta-scores of such components. In contrast, components with differing contributions from each molecular layer highlight the specificities of each modality, which can be inferred from the clustering based on the ISM meta-scores of such components.

The area of spatial mapping, including spatial imaging and spatial transcriptomics, is expanding at an unprecedented pace. An effective method for integrating different levels of information such as gene or protein expression and spatial organization of cell phenotypes is an unmet methodological need. We believe that ISM can integrate these different levels of information, as shown in the analysis of the UCI digits data, to capture the constituents that allow spatial patterns to be distinguished across all levels.

The identification of new chemotypes with biological activity which is similar to that of a known active molecule is an important challenge in drug discovery known as "scaffold hopping" [23]. In this context, we are currently analyzing the fingerprints of the docking of tens of thousands of molecules to dozens of proteins, with protein-associated fingerprints forming the different views of each molecule. The goal is to use the ISM-transformed fingerprints to predict scaffold-hopping chemotypes. Given the enormous size of the dataset – each fingerprint contains more than 100 binary digits – the ILSM strategy is being evaluated as a possible way to reduce computational problems, as smaller sets of views can be analyzed on smaller subsets of observations before integrating them in their entirety.

6. Implementation

For k-means, MDS and PCA, Scikit-learn [22] is used. The mvlearn package [8] is used for MVMDS.

NMF and NTF are performed with the package adnmtf.

ISM is implemented in a Jupyter Python notebook.

Matplotlib, Pyplot tutorial — Matplotlib 3.8.2 documentation is used to create the clustering figures.

Treemaps are obtained with the Graph Builder platform from JMP®, Version 17.2.0. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2023.

The distinctipy package is used to generate colors that are visually distinct from one another.

7. Patents

Paul Fogel has filed a Provisional Application # 63/616,801 under 35 USC 111(b) with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) under the title “THE INTEGRATED SOURCES MODEL: A GENERALIZATION OF NON-NEGATIVE TENSORFACTORIZATION FOR THE ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE HETEROGENEOUS DATA VIEWS.”

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: ILSM analysis of the UCI digits data with masked views.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.F. and G.L.; methodology, software and visualization: P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P. F., C.G. and G.B; writing—review and editing: F.A., C.G and G.L.; investigation: G.B. and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article and the ISM Jupyter python notebook can be downloaded from the Advestis part of Mazars GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks to Prasad Chaskar, Translational Medicine Senior Expert Data Science Lead at Galderma, for stimulating discussions, especially on potential limitations arising from missing views when training latent models with multiple views; to Philippe Pinel, Center for Computation Biology, Mines Paris/PSL and Iktos SAS, Paris France, for discussions on addressing ISM calculation challenges in Computational Biology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smilde, A.K., Westerhuis, J.A., & de Jong, S. (2003). A framework for sequential multiblock component methods. Journal of Chemometrics, 17. [CrossRef]

- Trendafilov, N.T. (2010). Stepwise estimation of common principal components. Comput. Stat. Data Anal., 54, 3446-3457. [CrossRef]

- Tenenhaus, A., & Tenenhaus, M. (2013). Regularized generalized canonical correlation analysis for multiblock or multigroup data analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res., 238, 391-403. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Hu, Q., Fu, H., Zhu, P.F., & Cao, X. (2017). Latent Multi-view Subspace Clustering. 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 4333-4341. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Huang, L., Wang, C., & Huang, D. (2020). Multi-View Clustering in Latent Embedding Space. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L., Lin, P., Vasilakos, A.V., & Wang, S. (2020). An overview of recent multi-view clustering. Neurocomputing, 402, 148-161. [CrossRef]

- Cichocki, A., Zdunek, R., Phan, A., & Amari, S. (2009). Nonnegative Matrix and Tensor Factorizations - Applications to Exploratory Multi-way Data Analysis and Blind Source Separation. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 25, 142-145. [CrossRef]

- Perry, R., Mischler, G., Guo, R., Lee, T.V., Chang, A., Koul, A., Franz, C., & Vogelstein, J.T. (2020). mvlearn: Multiview Machine Learning in Python. ArXiv, abs/2005.11890. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Lin, Z., & Zha, H. (2018). Essential Tensor Learning for Multi-View Spectral Clustering. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 28, 5910-5922. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Gao, Q., Wang, Q., Xia, W., & Gao, X. (2023). Multi-View Clustering via Semi-non-negative Tensor Factorization. ArXiv, abs/2303.16748. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, P., Geissler, C., Morizet, N., & Luta, G. (2023). On Rank Selection in Non-Negative Matrix Factorization Using Concordance. Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Maisog, J.M., DeMarco, A.T., Devarajan, K., Young, S., Fogel, P., & Luta, G. (2021). Assessing Methods for Evaluating the Number of Components in Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Mathematics (Basel, Switzerland), 9. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, P., Hawkins, D.M., Beecher, C., Luta, G., & Young, S.S. (2013). A Tale of Two Matrix Factorizations. The American Statistician, 67, 207 - 218. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, P., Geissler, C., Von Mettenheim, J., & Luta, G. (in press). Applying non-negative tensor factorization to centered data. Bankers, Markets & Investor, 174.

- Hirschman, A.O. (1964). The Paternity of an Index. The American Economic Review, 54, 761-762.

- Badeau, R., Bertin, N., & Vincent, E. (2010). Stability Analysis of Multiplicative Update Algorithms and Application to Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 21, 1869-1881. [CrossRef]

- Demaine, E.D., Hesterberg, A., Koehler, F., Lynch, J., & Urschel, J.C. (2021). Multidimensional Scaling: Approximation and Complexity. International Conference on Machine Learning. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z., Lei, Y.L., Wang, R., & Xie, Y. (2022). Supervised capacity preserving mapping: a clustering guided visualization method for scRNA-seq data. Bioinformatics, 38, 2496 - 2503. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Zhao, L., Zong, L., Liu, X., & Yu, H. (2014). Multi-view Clustering via Multi-manifold Regularized Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, 1103-1108. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, Ashish, Noam M. Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser and Illia Polosukhin. “Attention is All you Need.” Neural Information Processing Systems (2017). [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Jin, I.H., & Jeon, M. (2021). How Social Networks Influence Human Behavior: An Integrated Latent Space Approach for Differential Social Influence. Psychometrika, 88, 1529 - 1555. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Louppe, G., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Weiss, R.J., Vanderplas, J., Passos, A., Cournapeau, D., Brucher, M., Perrot, M., & Duchesnay, E. (2011). Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. ArXiv, abs/1201.0490. [CrossRef]

- Pinel, P., Guichaoua, G., Najm, M., Labouille, S., Drizard, N., Gaston-Mathé, Y., Hoffmann, B., & Stoven, V. (2023). Exploring isofunctional molecules: Design of a benchmark and evaluation of prediction performance. Molecular Informatics, 42. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).