1. Introduction

The conventional perspective on spastic paresis, especially in hemiparesis, has long held that the difficulty in raising the foot during the swing phase of gait is primarily due to the activation of plantar flexor stretch reflexes triggered by ankle dorsiflexion [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, classic anti-spasticity interventions (“antispastic” drugs, Bobath-type therapies, etc.) may prove highly disputable if spasticity, as defined by stretch reflex enhancement, assessed at rest [

7] is proven to be a non significant factor in the gait impairment observed in hemiparesis. The modulation of stretch reflexes is notably diminished in hemiparesis [

8,

9], which may contribute to the limitations observed in single joint movements, including those involving the knee [

10] or the ankle [

5], as well as in multi-joint movements like cycling [

11] and locomotion [

12,

13]. However, it is worth noting that, when directly measured, spasticity has shown poor correlation with impairment in voluntary movement [

10,

14,

15,

16,

17]. A number of studies have shown that stretch reflex hyperexcitability, which is evident at rest, disappears during muscle activation [

18,

19,

20]. Modulation in stretch reflexes during the gait cycle have been well-documented, in the mesencephalic cat [

21] as in healthy individuals, with particular emphasis during the mid-swing phase, and these modulations only partially correlate with EMG changes or soleus muscle length [

22,

23]. A decrease in H-reflex excitability throughout the swing phase is in fact described in adult hemiparesis [

15] and in individuals with cerebral palsy [

24].

Spastic Cocontraction, a phenomenon originating from descending pathways, has been defined as a misdirection of the supraspinal drive that abnormally activates muscle antagonists during an intended movement, especially when the antagonist is stretched [

25,

26,

27]. While excessive plantar flexor activation, stemming from descending pathways rather than reflexes, has been reported has a potential contributing factor to the reduction of ankle dorsiflexor agonist moment during swing phase in spastic paresis [

7,

25,

26,

28,

29,

30], quantifying antagonist cocontraction during a dynamic condition as gait remains challenging and attempts have been scarce. The aim of this study was to quantify the recruitment of agonist dorsiflexors and ankle plantar flexor cocontraction during the swing phase of gait in individuals with hemiparesis, by integrating kinematic and EMG recordings during three periods of the swing phase (initial, mid and terminal swing; [

31]). The study involved a group of individuals with hemiparesis of which a subgroup (45%) had undergone prior tibial nerve neurotomy [

32], resulting therefore in the absence of residual plantar flexor spasticity. We compared this sample of hemiparetic subjects to healthy individuals walking at two different velocities, comfortable and slow, to account for any velocity-related kinematic or EMG modifications [

30,

33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the relevant research Ethics Committee (

Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France IX; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01415700; P070155; ID-RCB number 2007-A01444-49). Kinematic and EMG evaluations were carried out in Laboratory of Analysis and Restoration of Movement (ARM) at Henri Mondor Hospital (AP-HP, Créteil, France). Healthy subjects and subjects with chronic hemiparesis were recruited from the Neurosurgery Unit of Henri Mondor Hospital (Créteil, France); The number of subjets was arbitraly fixed to 11 per group. Inclusion criteria for the healthy subjects were: absence of neurological disorder and age < 75 years. The subjects with hemiparesis were already enrolled in an ongoing clinical research protocol that involved a comparison of ankle foot orthoses with implanted peroneal nerve stimulations, as treatments for the dorsiflexion deficit in hemiparesis during gait [

34]. Inclusion criteria for the subjects with hemiparesis were: age ≥18 years, central nervous lesion that occurred at least 12 months before enrolment; ability to walk over a distance of 50 m with or without assistive device; impaired paretic ankle dorsiflexion during the swing phase of gait as per the investigator; ability to walk with an ankle foot orthosis; possibility to stimulate the peroneal nerve; absence of neurotomy in the paretic lower limb in the past 12 months before enrolment; absence of neurolytic alcohol or phenol block in the past 6 months; absence of botulinum injection in the paretic lower limb in the past 4 months; written consent for participation. Non-inclusion criteria were: maximal passive ankle dorsiflexion in the paretic limb with knee extended <0° (i.e., Tardieu X

V1 gastrocnemius <90°) [

33,

34]; use of orthopaedic shoes covering the malleolus; any contraindication to general anaesthesia; ongoing use of another implanted stimulator (included cardiac pacemaker); systemic use of synaptic depressors, such as neuroleptics, gamma-amino-butyric ascid (GABA)-ergic agents, antidepressants or any other drug that might affect walking ability; untreated epilepsy; peripheral nervous system lesion; pregnant or nursing woman; absence of affiliation to healthcare coverage.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

Subjects with hemiparesis were first assessed for ankle plantar flexor spasticity at rest using the Tardieu scale, which determined the spasticity angle and grade both for soleus (knee flexed) and for gastrocnemius (knee extended) [

35,

36].

2.2.1. EMG Assessment

Following clinical evaluation, pairs of surface electrodes (Arbo H135TSG) were applied after skin cleaning to reduce impedance, to monitor dorsiflexor and plantar flexor muscle activity. Electrode placement followed the recommendations outlined by Basmajian and Blumenstein, 1980 [

37]. Surface EMG recordings used an 8-channel Bluetooth device (Mega Electronics Ltd., Kuopio, Finland) to monitor ankle dorsiflexor (Tibialis anterior, TA) and plantar flexor activity (Soleus, SO and Gastrocnemius Medialis, GM). Subjects initially sat with the hip flexed at 90°, knee extended (0°) and ankle in neutral posture (0°). The paretic leg was analysed in subjects with hemiparesis and the right leg in healthy subjects. All subjects were asked to perform maximum isometric dorsiflexor and plantar flexor contractions. Maximal contractions were repeated twice and verbally encouraged to obtain the best maximal muscle activation [

38]. The recorded EMG signals were amplified (x1000), filtered using a high pass filter of 30Hz and then rectifiedto generate an amplitude profile. All calculations and data processing were performed using a custom program developed with Matlab (R2022b, Natick, Massachusetts - USA).

2.2.2. Kinematic Gait Analysis

Twenty-nine reflective markers (1 cm diameter) were mounted on the head, back, shoulder, elbow, wrist, pelvis, thigh, knee, leg and foot for each subject, according to the Helen Hayes recommendations [

39]. Following calibration in the static position, subjects with hemiparesis walked at comfortable speed over an 8-meter walkway (GAITRite Platinum, dimensions 0.61*7.92m, Fe=60Hz, CIR Systems, Inc., Sparta, NJ, USA). Healthy subjects were asked to walk at two self-selected speeds: comfortable first and then slow. Kinematic and EMG data were collected simultaneously on both sides for each subject. Six trials at each velocity with at least one stride for each side [

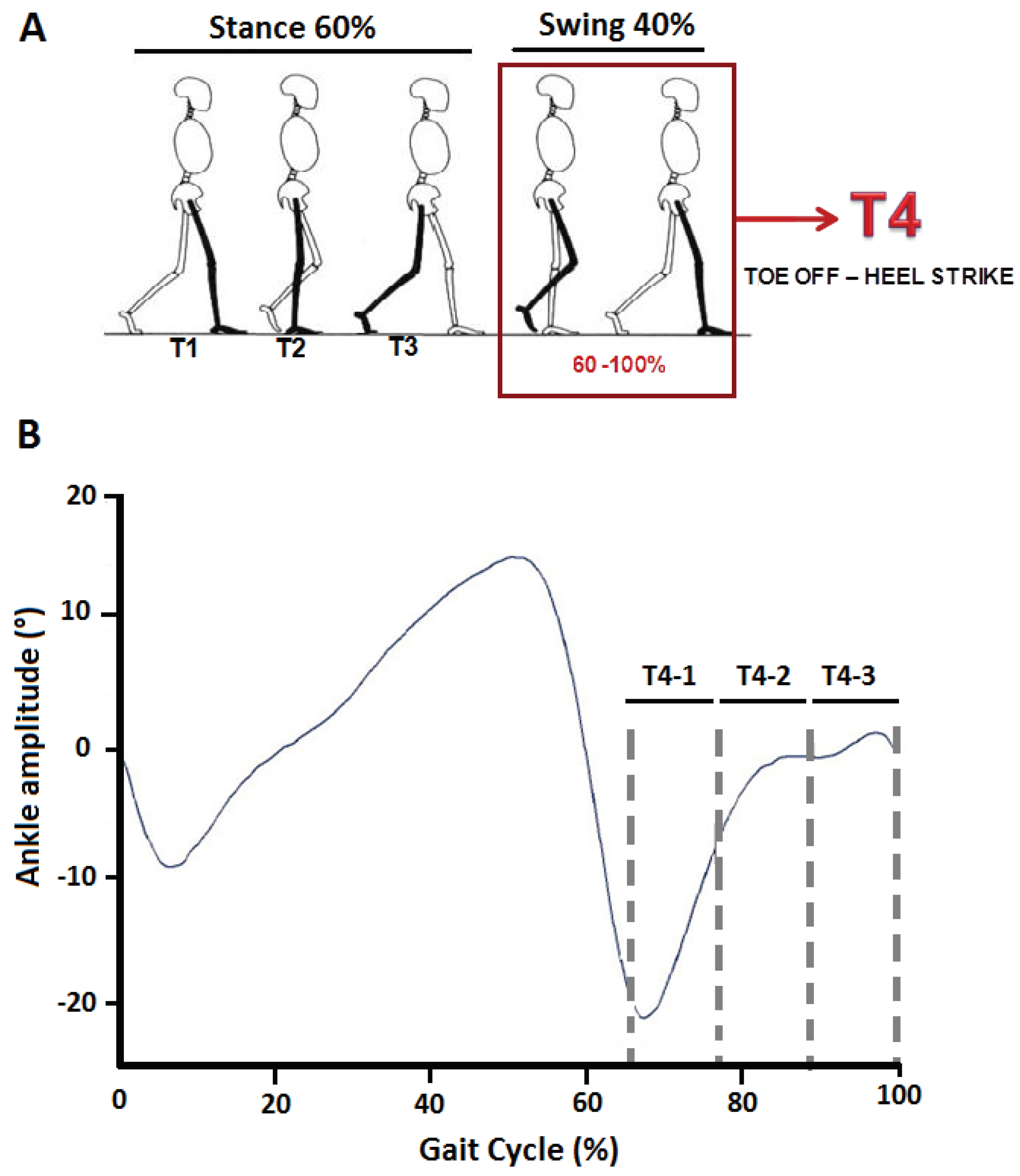

40] were recorded using the Motion Analysis Capture System (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). Kinematic signals were amplified (x100) and filtered using a 3Hz Butterworth filter. For each side of the body, duration of the gait cycle was defined as the time between two consecutive heel contacts (ipsilateral) on the ground. Ground reaction forces were obtained from six force platforms (dimensions 0.60*0.40 m, Bertec Corporation, Columbus, OH, USA) integrated into the walking pathway and used for calculation of spatial parameters. Once the phases of the gait cycle were detected, each gait cycle was divided into four phases, 3 stance periods (T1-T2-T3) and the swing phase, from toe-off until heel-strike, representing 60-100% of the gait cycle (T4,

Figure 1A). The swing phase (T4) was further divided into three equal periods: T4-1, T4-2 and T4-3,

Figure 1B). For each period, we calculated the minimal (min) and maximal (max) ankle dorsiflexion (ADF) excursions, obtained by calculation of the position change of the foot to the tibia relative to the reference position of the ankle (bipodal support). At least eight gait cycles from each lower limb were used for the kinematic and EMG analysis.

2.3. Data Processing

From the filtered and rectified EMG, we obtained: (i) the Root Mean Square (RMS) during maximum voluntary isometric effort (RMS

MAX), calculated over the 500 ms around the peak voltage [

41], for the TA (Tibialis Anterior), GM (Gastrocnemius Medialis) and SO (Soleus) muscles; (ii) the RMS of the same muscles throughout the entire swing phase (RMS

T4), then over the three sub-periods of the swing phase (RMS

T4-1, RMS

T4-2, RMS

T4-3). From these measurements we derived the following coefficients:

Coefficient of AGonist activity in TA (CAGTA) by calculating the ratio of the RMSTA-T4/RMSTA-MAX of TA throughout swing phase and over each of the three predefined periods of the swing phase [27; 17];

Coefficient of ANtagonist activity in GM and SO (CANGM, CANSO) by calculating the ratios RMSGM-T4/RMSGM-MAX and RMSSO-T4/RMSSO-MAX, throughout the swing phase, then over the three sub-periods of the swing phase [26; 17];

Minimum (min) and maximum (max) amplitude of ankle flexion (ADF) across the entire swing phase (T4) and over each of the three predefined periods of the swing phase, measured at comfortable velocity for hemiparetic subjects and at comfortable and slow velocity for healthy subjects.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis (means, standard deviations) to characterize the spatial-temporal parameters (velocity, percentage of swing phase, stride length and cadence) in hemiparetic subjects and healthy subjects in both velocity conditions (comfortable and slow). We then performed a two-way ANOVA (group x swing period) to compare kinematic and EMG variables between groups and across the three swing periods for both velocity conditions. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using Bonferroni corrections. We used Kruskal-Wallis tests to detect an interaction between patient groups with and without tibial neurotomy during the whole swing phase (T4) and a Wilcoxon test to identify differences between both groups across the three periods of the swing phase (T4-1, T4-2, T4-3). Significance was set at p< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Eleven subjects with chronic hemiparesis (age 51 ± 14, mean ± SD) delay post-lésion

12.2y ± 15.8y, mean ± SD) and 11 healthy subjects (age 48 ± 22) were included in the study. Among the 11 subjects with hemiparesis, five had previously undergone tibial neurotomy overa year before inclusion in the research protocol. The surgical procedure had involved partial selective section of the nerves that supply the soleus and the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius muscles. This procedure was carried out following a vertical skin incision below the popliteal fossa and the identification of all tibial nerve branches. Subsequently, the branches leading to the soleus and medial and lateral gastrocnemius muscles were exposed and dissected, and partially sectioned using an operating microscope. To determine the extent of nerve sectioning, tripolar stimulation was employed to assess the remaining nerve conduction of the denervated muscles, enabling the surgeons to halt the sectioning process once the desired reduction of nerve conduction was achieved.

Table 1 display spasticity angles and grades for both soleus (knee flexed) and gastrocnemius-soleus complex (knee extended) measured by using the Tardieu Scale [

35] and gait velocity for the hemiparetic subjects untreated (n=6) and treated with tibial neurotomy (n=5).

3.2. Spatial-Temporal Parameters

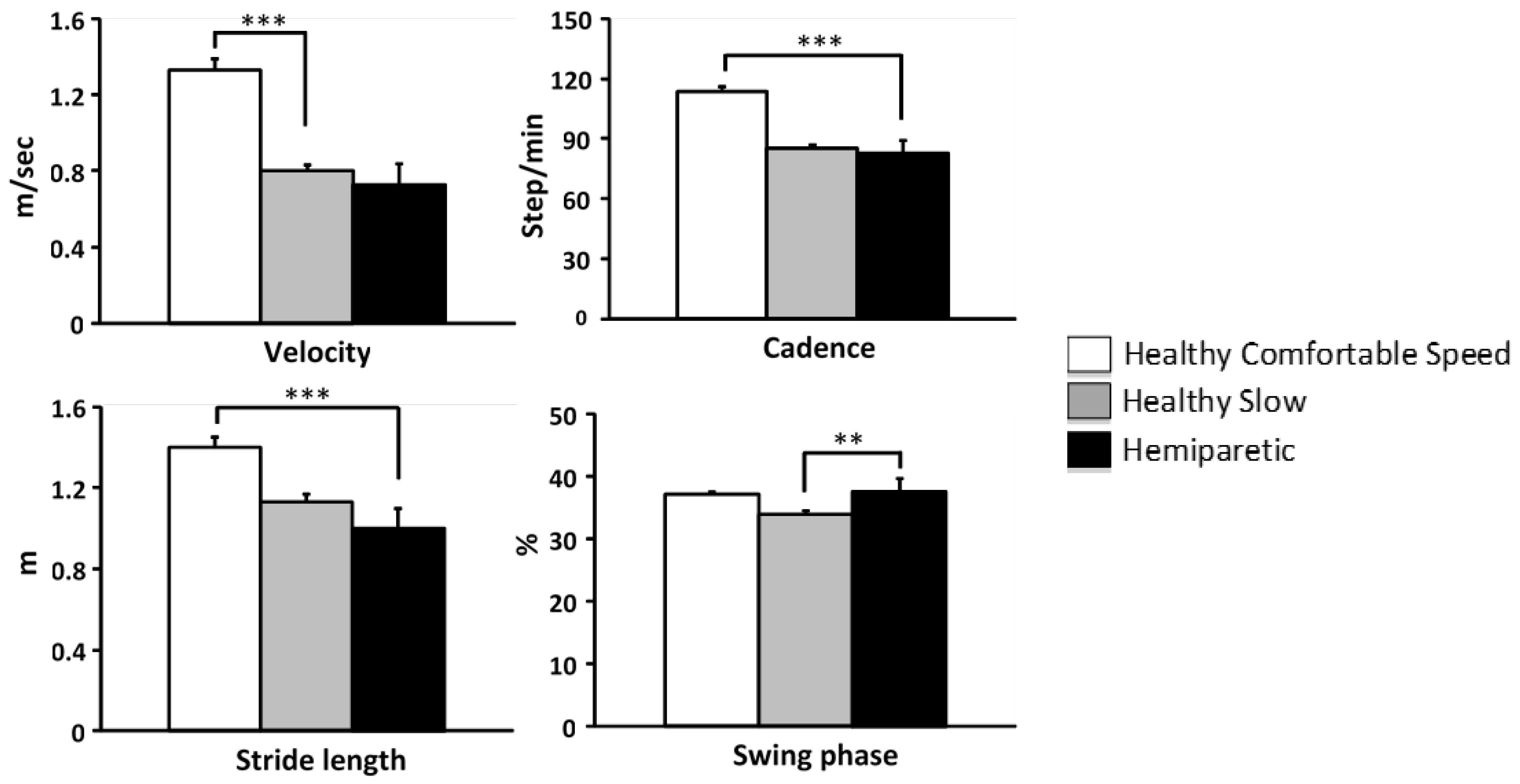

The one-way (group) ANOVA test revealed lesser velocity in hemiparetic subjects relative to healthy subjects at comfortable velocity (

p<0.0001) but not relative to healthy subjects at slow velocity (NS;

Figure 2). Cadence and stride length were lower in hemiparetic subjects than in control subjects at comfortable velocity (cadence, F=297.04,

p<0.0001; stride length, F=252.99,

p=0.0001), but no different from healthy subjects walking at slow velocity (cadence, NS, stride length, NS,

Figure 2). The proportion of the swing phase relative to the gait cycle in hemiparetic subjects was greater than in controls walking slowly (F=6.98,

p<0.01,

Figure 2).

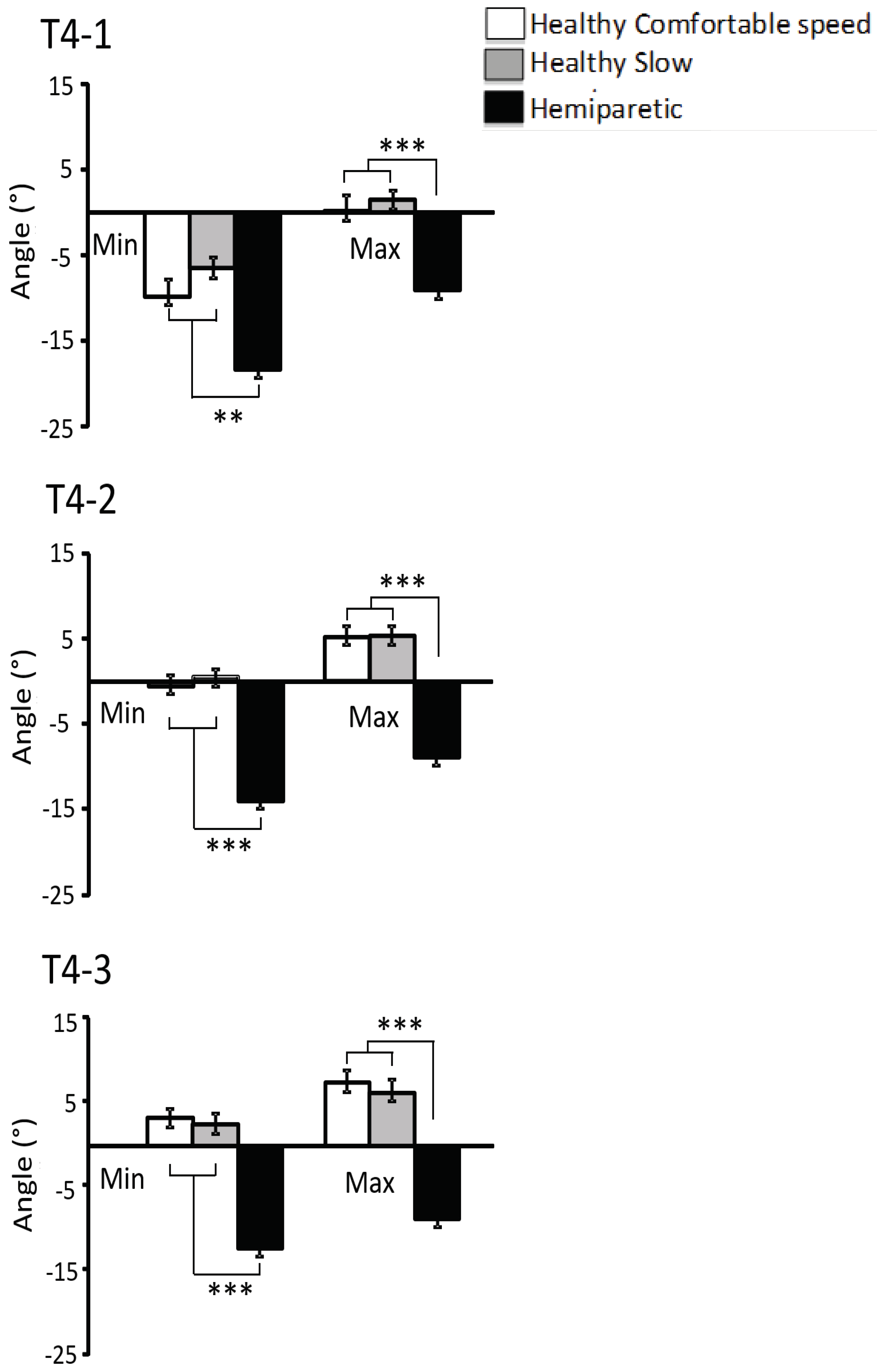

3.3. Ankle Kinematics

Minimal ankle dorsiflexion amplitudeADF

min(defined as negative ankle joint angle), was lower in hemiparetic than in control subjects at comfortable and slow velocity throughout swing phase: ADF

min T4: -20 ± 3° in hemiparetic subjects vs -10 ± 2°,

p<0.0001 in control subjects at comfortable velocity and vs. -7 ± 2°,

p<0 0001 in control subjects at slow velocity, and whichever the period of swing phase (T4-1,

p<0.01, T4-2,

p<0.001, T4-3,

p<0.001,

Figure 3).

Maximum ankle dorsiflexion amplitude, ADF

max, was lower in hemiparetic than in control subjects at comfortable and slow velocity throughout swing phase (ADF

max T4: -6 ± 2° in hemiparetic subjects vs. 8 ± 1°,

p<0.0001 in control subjects at comfortable velocity, vs. 8 ± 1°,

p<0.0001 in control subjects at slow velocity) and whichever the sub-period of the swing phase (T4-1,

p<0.001, T4-2,

p<0.001, T4-3,

p<0.001,

Figure 3).

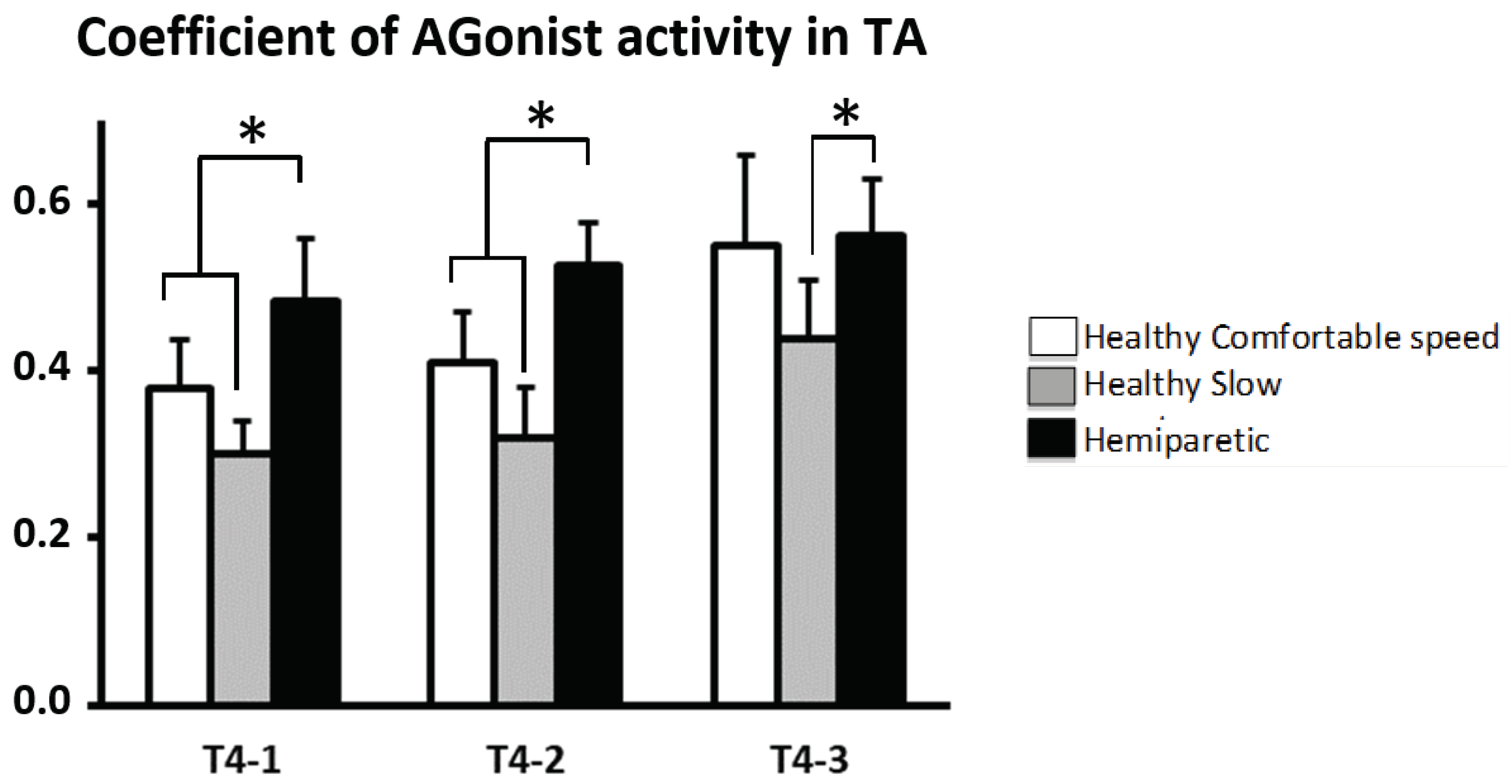

3.4. EMG of Agonist Muscle during Swing Phase

CAG

TA: throughout swing phase (T4) there was a difference between hemiparetic and controls: CAG

TA-T4, 0.48 ± 0.26 (

p<0.001) in healthy subjects vs. 0.57 ± 0.05 in subjects with hemiparesisat comfortable walking velocity and 0.38 ± 0.05 (

p<0.0001) in healthy subjects at slow walking velocity. The subjects with hemiparesis showed increased CAG

TA across T4-1 and T4-2 compared to healthy subjects at comfortable walking velocity (T4-1: healthy group, 0.38 ± 0.06; hemiparetic group, 0.48 ± 0.08,

p <0.05 ; T4-2: healthy group, 0.41 ± 0.06; hemiparetic group, 0.53 ± 0.05,,

p <0.05) and across the three sub-periods of swing phase compared to healthy subjects at slow walking velocity (T4-1: healthy group, 0.30 ± 0.05; hemiparetic group, 0.48 ± 0.08,

p<0.05; T4-2: healthy group, 0.31 ± 0.05, hemiparetic group, 0.53 ± 0.05,

p<0.05; T4-3: healthy group, 0.45 ± 0.05, hemiparetic group, 0.56 ± 0.07,

p<0.05,

Figure 4).

3.5. EMG in Antagonist Muscles during Swing Phase

CAN

GM is higher in subjects with hemiparesis compared to healthy subjects walking at comfortable velocity (CAN

GM-T4: healthy group, 0.15 ± 0.01, hemiparetic group, 1.21 ± 0.21,

p<0.0001) also compared to healthy subjects walking at slow velocitie (0.13 ± 0.01,

p<0.0001). When considering each period of the swing phase separately, subjects with hemiparesis showed an increased CAN

GM across the three periods(

p<0.001,

Figure 5A).

CAN

SO is higher in subjects with hemiparesis (CAN

SO-T4: healthy group at comfortable walking velocity, 0.07 ± 0.01; at low walking velocity, 0.06 ± 0.01; hemiparetic group, 1.22 ± 0.13;

p<0.0001). CAN

SO was majored in each period of swing (

p<0.0001,

Figure 5B).

3.6. Comparison of CANs with and without Tibial Neurotomy

Throughout the swing phase CANs were higher in subjects with hemiparesis and tibial neurotomy vs. without neurotomy (CAN

SO, without, 1.48 ± 0.2, with, 0.95 ± 0.3, Kruskal-Wallis,

p<0.001; CAN

GM, without, 1.50 ± 0.2, with, 1.00 ± 0.3,

p=0.07). These increases remained observed in each period of the swing phase for the CAN

SO (T4-1,

p<0.001; T4-2,

p<0.01; T4-3,

p<0.05) and only the initial and middle swing for CAN

MG (T4-1,

p<0.001; T4-2,

p=0.03; T4-3, NS,

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

In this study, the investigation of plantar flexor cocontraction during the swing phase of hemiparetic gait as compared to speed-matched healthy gait, revealed several key findings. The swing phase was relatively slower in hemiparetic gait and there was a severe deficiency in the amplitude of ankle dorsiflexion throughout the entire swing phase. The deficit in ankle dorsiflexion was associated with a major increase in plantar flexor cocontraction. Notably, this cocontraction was even more pronounced in the five out of 11 hemiparetic subjects who had previously undergone tibial neurotomy. Conversely, the coefficient of agonist recruitment of tibialis anterior in subjects with hemiparesis was greater than in healthy subjects. These events may suggest an appropriate attempt of the automatic command of gait to compensate for the reduced plantar flexor extensibility by increasing agonist dorsiflexor recruitment, which may imply increased plantar flexor cocontraction due to the misdirection of the supraspinal drive that came as a consequence of lesion-induced spinal plasticity with rerouting of a number of the descending pathyways both to agonist and to antagonist motor neurons.

4.1. Relative Slowing of Swing Phase in Hemiparetic Gait and Ankle Kinematics

The well-documented slowed velocity of hemiparetic gait [

42,

43,

44,

45] guided our decision to have healthy control individuals deliberately walk slowly. This adjustment was made to align the motor command conditions with those observed in hemiparesis, thereby ruling out the possibility that some kinematic and EMG changes during swing phase in hemiparetic subjects might be attributable to anticipated speed-related changes [

33,

46]. The slow velocity self-selected by the healthy individuals in this study turned out to be similar to the comfortable velocity of hemiparetic subjects, enabling comparisons between the two groups from this perspective. The observations related to stride length, cadence, and swing phase duration demonstrated velocity-related patterns in healthy subjects, which align with previous research findings [

44,

47,

48]. Similarly, the reductions in gait velocity, stride length and cadence in our hemiparetic group were akin to previous data in hemiparesis [

33,

49,

50,

51]. However, even when comparing with speed-matched controls, the swing phase duration was about 10% slower in subjects with hemiparesis. This likely goes to indicate that the most significant impairment of gait in chronic hemiparesis manifests during swing - or pre-swing -, more so than during stance. The lacks of knee flexion (not quantified here), therefore of gastrocnemius tension release and the deficit ofactive dorsiflexion during swing phase in hemiparetic subjects are well established data [

12,

29,

33,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Notably, the relative deficit in dorsiflexion amplitude appeared to worsen as the swing phase progressed, as was observed in other samples of subjects with hemiparesis [

29]. Indeed, in contrast to healthy subjects who gradually increased ankle dorsiflexion across the three periods of swing, hemiparetic subjects exhibited overall quasi-constant plantar flexed position throughout the entire swing. This observation makes it unlikely that any significant component of plantar flexor activity during swing might have been triggered by stretch reflexes, pointing to a different underlying mechanism.

4.2. Tibialis Anterior Agonist Recruitment Behavior over the Swing Phase of Gait

In healthy individuals, ankle dorsiflexion was associated with an increase in tibialis anterior activity, more pronounced as walking velocity increased (both raw – not shown - and normalized EMG values increased with velocity in this study), which is consistent with well-known data [

44,

55,

56]. At faster speeds, limb segments move through greater range of motion in shorter times and therefore require higher muscle activity. On the other hand, a decrease in raw tibialis anterior activity observed on the paretic side in subjects with hemiparesis also corroborates previous findings [

6,

12,

49,

57,

58] as well as its association with limited ankle dorsiflexion [

15,

52,

59,

60]. A key observation in this study was the increased coefficient of agonist recruitment in our subjects with hemiparesis walking on solid ground, compared to speed-matched controls, which may depars from the “close-to-normal” pattern of recruitment observed in studies that attempted to explore tibialis anterior recruitment duing treadmill walking in hemiparesis [

61]. The impression is that motor command in hemiparesis appropriately takes the limited available agonist torque-producing and firing capacity into account and compensates by increasing the relative effort of TA recruitment [

49,

56,

62]. Such enhanced effort may help to anticipate abnormal resistances coming from reduced passive extensibility of the plantar flexors [

7,

63,

64,

65,

66]. Active resistance from plantar flexors ended up also markedly increased compared to controls, with about 250% increase in coefficient of antagonist activation of medial gastrocnemius and soleus. An excessive stretch reflex responsein TA triggered during pre-swing plantar flexion could also be suggested among potential factors that may have contributed to an over-recruitement of TA as discussed by Ghédira et al. [

29], who reported a similar increase i relative TA recruitment in the first third of the swing phase of gait.

4.3. Plantar Flexors Cocontraction Behavior over the Swing Phase of Gait

Despite the diversity of methods for calculating cocontraction in the literature, including the present Coefficient of ANtagonist Activity method using normalization to the maximal voluntary isometric contraction [

6,

12,

26,

27,

29,

52,

54,

67,

68,

69,

70], excessive plantar flexor activity during hemiparetic gait has frequently been reported in comparaison to healthy subjects [

12,

26,

27,

44,

49,

53,

68,

70]. The significant increases in GM and SO antagonist activation observed in this study seem to point to antagonist cocontraction of plantar flexors during swing phase as a major factor limiting active ankle dorsiflexion. In fact, it was remarkable that in some cases, coefficients of antagonist activation in subjects with hemiparesis exceeded 1, indicating greater recruitment of plantar flexors as antagonists during natural dorsiflexion efforts, such as in the swing phase of gait, than their maximal voluntary recruitment assessed in a seated position with the knee straight. However, it is worth noting that the maximal active recruitment of plantar flexors might have been greater if it had been measured in standing position, as recently used in adult [

29] and demonstrated in children [

71]. Reported coefficients of antagonist activation where around 60% of the maximal firing rate capacity in both paretic populations. The better neural activation capacity of plantar flexors through this more functional, position of overall body extensionand of anticipated anti-gravity action represents rather a more physiological-based opportunity, where segmental and descending pathways might be better elicited. Agonist plantar flexors from a standing condition used as normative values to derive cocontraction indices may consequently have higher validity and relevance for extrapolation when scaling EMG data [

72].

In this study, it is also notable that CAN

GM kept increasing throughout the swing phase (

Figure 5A) much like CAG

TA. It is difficult to establish from the present data whether one “followed” the other. In other words, one may wonder whether activation-dependent cocontraction (misdirection of the descending drive, [

25,

26,

27]) merely followed the gradually increased effort directed to the dorsiflexors, or whether agonist recruitment simply attempted to compensate for increasing antagonist resistance. The increased gastrocnemius cocontraction might relate to the knee re-extension that occurs during the late phase of swing [

26] due to the enhanced muscle spindle activity with stretched position of the cocontracting muscle [

25,

26]. Such knee extension places the GM under increased tension by lengthening (eccentric contraction), which could facilitate GM motor neurons and exacerbate the impact of any misdirected descending signal on these motor neurons, accordingto the phenomenon previously described for spastic cocontraction [

7,

26,

27]. In the specific case of soleus, increased afferent activity from gastrocnemius spindles during knee re-extension may fail to inhibit and in fact trigger heteronymous facilitation of soleus motor neurons [

73,

74], contributing to their increased coactivation.

4.4. Spasticity Playing a Role in Plantar Flexor Cocontraction?

First performed by Stoffed in 1912, selective tibial nerve neurotomy is one of the mainstream procedures in the treatment of dynamic equinusdeformity in paretic children and adults [

75,

76]. This peripheral surgical technique, which involves sectioning part of the motor nerve fascicles or branches innervating spastic muscles, has been reported to ensure long-term functional improvement in patients with spastic equinus foot [

77,

78,

79,

80]. In the present study, the totality of the hemiparetic subjects who underwent tibial neurotomy less than a year before, showed suppression of spasticity as confirmed by the spasticity angle of the Tardieu scale (

Table 1), which provides a precise evaluation of stretch hyperreflexia irrespective of muscle contracture [

81]. By interrupting both afferent (Ia and II) and efferent motor (α and γ) underlying the myotatic reflex, tibial neurotomy is indeed known to permanently suppress spasticity [

82,

83,

84]. At this point the presence of antagonist plantar flexor cocontraction during the swing phase of gait in individuals with no residual plantar flexor spasticity raises questions about the underpinning of spastic cocontraction and in fact further points to a primarily central mechanism [

7]. The present study shows indeed that plantar flexor cocontraction during gait occurred even in subjects with prior tibial neurotomy who had no residual spasticity in the plantar flexors, and it also occurred in the first sub-period of swing despite absence of dorsiflexion movement in most subjects. Spastic cocontraction, unlike plantar flexor spasticity measured at rest, appears to be an importantcontributor to the deficit in active dorsiflexion during the swing phase of gait. The present findings tend to confirm that this phenomenon, which is worsened when the cocontracting muscle is placed under tension in stretched position [

25,

26,

27,

29], is primarily a descending phenomenon. Correlation between cortical β-band electroencephalogram activity and spastic cocontraction in a stroke population has been recently reported [

85], providing further evidence for the role of the supraspinal centers in this phenomenon.

5. Conclusions

Investigation after investigation, spastic paresis confirms to be primarily a “disease of the antagonist”[

7,

86], i.e., a motor command disorder in which the ability to reduce passive and active resistances from the antagonist is more impaired than the ability to recruit the agonist. The use of EMG to quantify spastic cocontraction during the dynamic condition of gait in subjects with and without prior tibial neurotomy seems a relevant tool offering discriminative insights into the origin and physiological mechanisms of spasticity and spastic cocontraction. The results of this study underscore the need for expanding the assessment of spastic cocontraction impact on active/functional movements and on its supraspinal origin. Quantitative measure of antagonist muscle overactivity during gait will consequently enable more consistent diagnosis and provide simplified and specified guidance towards the

coupled treatment strategy ratio of botulinum toxin/rehabilitation techniques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MV, EH and JMG ; methodology, MV, EH and JMG; software, MB and AM; formal analysis, MV and MB; investigation, MV, MB, EH and MG; resources, WS, HP, JMG, NB and PD; data curation, MV, MB, EH and MG; writing—original draft preparation, MV and MB; writing—review and editing, all co-authors; visualization, MV and MB; supervision, WS, HP, JMG, NB and PD; project administration, WS, HP, JMG, NB and PD; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Please turn to the CRediT taxonomyfor the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the relevant research Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile-de-France IX; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01415700; P070155; ID-RCB number 2007-A01444-49). Kinematic and EMG evaluations were carried out in Laboratory of Analysis and Restoration of Movement (ARM) at Henri Mondor Hospital (AP-HP, Créteil, France).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Phelps, W.M. Cerebral Birth Injuries: Their Orthopaedic Classification and Subsequent Treatment. Clin. Orthop. 1966, 47, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobath, B. Adult Hemiplegia: Evaluation and Treatment; Heinemann Medical, 1978; ISBN 978-0-433-03334-9.

- Pierrot-Deseilligny, E.; Mazières, L. [Reflex circuits of the spinal cord in man. Control during movement and their functional role (1)]. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 1984, 140, 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny, E.; Mazières, L. [Reflex circuits of the spinal cord in man. Control during movement and functional role (2)]. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 1984, 140, 681–694. [Google Scholar]

- Corcos, D.M.; Gottlieb, G.L.; Penn, R.D.; Myklebust, B.; Agarwal, G.C. Movement Deficits Caused by Hyperexcitable Stretch Reflexes in Spastic Humans. Brain J. Neurol. 1986, 109 (Pt 5) Pt 5, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiavi, R.; Bugle, H.J.; Limbird, T. Electromyographic Gait Assessment, Part 2: Preliminary Assessment of Hemiparetic Synergy Patterns. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 1987, 24, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gracies, J.-M. Pathophysiology of Spastic Paresis. II: Emergence of Muscle Overactivity. Muscle Nerve 2005, 31, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, M.F.; Hui-Chan, C. Are H and Stretch Reflexes in Hemiparesis Reproducible and Correlated with Spasticity? J. Neurol. 1993, 240, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinkjaer, T.; Toft, E.; Hansen, H.J. H-Reflex Modulation during Gait in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Spasticity. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1995, 91, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, D.L. C0-Contraction and Stretch Reflexes in Spasticity during Treatment with Baclofen. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1977, 40, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benecke, R.; Conrad, B.; Meinck, H.M.; Höhne, J. Electromyographic Analysis of Bicycling on an Ergometer for Evaluation of Spasticity of Lower Limbs in Man. Adv. Neurol. 1983, 39, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knutsson, E.; Richards, C. Different Types of Disturbed Motor Control in Gait of Hemiparetic Patients. Brain J. Neurol. 1979, 102, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, J.; Barbeau, H. A Dynamic EMG Profile Index to Quantify Muscular Activation Disorder in Spastic Paretic Gait. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1989, 73, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, W.M. Editorial: Spasticity: The Fable of a Neurological Demon and the Emperor’s New Therapy. Arch. Neurol. 1974, 31, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, V.; Quintern, J.; Berger, W. Electrophysiological Studies of Gait in Spasticity and Rigidity. Evidence That Altered Mechanical Properties of Muscle Contribute to Hypertonia. Brain J. Neurol. 1981, 104, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsson, E.; Mårtensson, A. Dynamic Motor Capacity in Spastic Paresis and Its Relation to Prime Mover Dysfunction, Spastic Reflexes and Antagonist Co-Activation. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1980, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ghédira, M.; Pradines, M.; Mardale, V.; Gracies, J.-M.; Bayle, N.; Hutin, E. Quantified Clinical Measures Linked to Ambulation Speed in Hemiparesis. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2022, 29, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.K.; Berger, W.; Trippel, M.; Dietz, V. Stretch-Induced Electromyographic Activity and Torque in Spastic Elbow Muscles. Differential Modulation of Reflex Activity in Passive and Active Motor Tasks. Brain J. Neurol. 1993, 116 (Pt 4) Pt 4, 971–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkjaer, T.; Magnussen, I. Passive, Intrinsic and Reflex-Mediated Stiffness in the Ankle Extensors of Hemiparetic Patients. Brain J. Neurol. 1994, 117 (Pt 2) Pt 2, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Crone, C.; Christenhuis, D.; Petersen, N.T.; Nielsen, J.B. Modulation of Presynaptic Inhibition and Disynaptic Reciprocal Ia Inhibition during Voluntary Movement in Spasticity. Brain J. Neurol. 2001, 124, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akazawa, K.; Aldridge, J.W.; Steeves, J.D.; Stein, R.B. Modulation of Stretch Reflexes during Locomotion in the Mesencephalic Cat. J. Physiol. 1982, 329, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenna, P.; Frigo, C. Excitability of the Soleus H-Reflex Arc during Walking and Stepping in Man. Exp. Brain Res. 1987, 66, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett M; Ireland A; Luckwill RG Changes in Excitability of the Hoffmann Reflex during Walking in Man. J Physiol 1984.

- Crenna, P. Spasticity and “spastic” Gait in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1998, 22, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracies, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Gandevia, S.C.; Burke, D. Gracies, J.M.; Wilson, L.; Gandevia, S.C.; Burke, D. Stretched Position of Spastic Muscles Aggravates Their Cocontraction in Hemiplegic Patients. In Proceedings of the Annals of Neurology; LIPPINCOTT-RAVEN PUBL 227 EAST WASHINGTON SQ, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19106, 1997; Vol. 42, pp. T183–T183.

- Vinti, M.; Couillandre, A.; Hausselle, J.; Bayle, N.; Primerano, A.; Merlo, A.; Hutin, E.; Gracies, J.-M. Influence of Effort Intensity and Gastrocnemius Stretch on Co-Contraction and Torque Production in the Healthy and Paretic Ankle. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinti, M.; Bayle, N.; Hutin, E.; Burke, D.; Gracies, J.-M. Stretch-Sensitive Paresis and Effort Perception in Hemiparesis. J. Neural Transm. Vienna Austria 1996 2015, 122, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardieu G Les Feuillets de l’Infirmité Motrice Cérébrale; Association Nationale des IMC; 1972.

- Ghédira, M.; Albertsen, I.M.; Mardale, V.; Loche, C.-M.; Vinti, M.; Gracies, J.-M.; Bayle, N.; Hutin, E. Agonist and Antagonist Activation at the Ankle Monitored along the Swing Phase in Hemiparetic Gait. Clin. Biomech. Bristol Avon 2021, 89, 105459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement; 4. ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2009; ISBN 978-0-470-39818-0. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function; SLACK: Thorofare, NJ, 1992; ISBN 978-1-55642-192-1. [Google Scholar]

- Buffenoir, K.; Rigoard, P.; Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Filipetti, P.; Decq, P. Lidocaine Hyperselective Motor Blocks of the Triceps Surae Nerves: Role of the Soleus versus Gastrocnemius on Triceps Spasticity and Predictive Value of the Soleus Motor Block on the Result of Selective Tibial Neurotomy. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 87, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.F.; Condon, S.M.; Price, R.; deLateur, B.J. Gait Abnormalities in Hemiplegia: Their Correction by Ankle-Foot Orthoses. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1987, 68, 763–771. [Google Scholar]

- Hutin, E.; Ghédira, M.; Vinti, M.; Tazi, S.; Gracies, J.-M.; Decq, P. Comparing the Effect of Implanted Peroneal Nerve Stimulation and Ankle-Foot Orthosis on Gait Kinematics in Chronic Hemiparesis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 55, jrm7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracies, J.-M.; Burke, K.; Clegg, N.J.; Browne, R.; Rushing, C.; Fehlings, D.; Matthews, D.; Tilton, A.; Delgado, M.R. Reliability of the Tardieu Scale for Assessing Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracies, J.M.; Marosszeky, J.E.; Renton, R.; Sandanam, J.; Gandevia, S.C.; Burke, D. Short-Term Effects of Dynamic Lycra Splints on Upper Limb in Hemiplegic Patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basmajian, J.V.; Blumenstein, R. Electrode Placement in EMG Biofeedback; Williams & Wilkins, 1980; ISBN 978-0-683-00376-5.

- Sahaly, R.; Vandewalle, H.; Driss, T.; Monod, H. Surface Electromyograms of Agonist and Antagonist Muscles during Force Development of Maximal Isometric Exercises--Effects of Instruction. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 89, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.B.; Õunpuu, S.; Tyburski, D.; Gage, J.R. A Gait Analysis Data Collection and Reduction Technique. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1991, 10, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, A.B.; Winter, D.A.; Marteniuk, R.G.; Hayes, K.C. How Many Strides Are Required for the Analysis of Electromyographic Data in Gait? Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1986, 18, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamjian, J.A.; Walker, F.O. Serial Neurophysiological Studies of Intramuscular Botulinum-A Toxin in Humans. Muscle Nerve 1994, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, D.H.; Schottstaedt, E.R.; Larsen, L.J.; Ashley, R.K.; Callander, J.N.; James, P.M. Clinical and Electromyographic Study of Seven Spastic Children with Internal Rotation Gait. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1969, 51, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J.; Hoffer, M.M.; Giovan, P.; Antonelli, D.; Greenberg, R. Gait Analysis of the Triceps Surae in Cerebral Palsy. A Preoperative and Postoperative Clinical and Electromyographic Study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1974, 56, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.P.; Mollinger, L.A.; Gardner, G.M.; Sepic, S.B. Kinematic and EMG Patterns during Slow, Free, and Fast Walking. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 1984, 2, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutin, E.; Ghédira, M.; Loche, C.-M.; Mardale, V.; Hennegrave, C.; Gracies, J.-M.; Bayle, N. Intra- and Inter-Rater Reliability of the 10-Meter Ambulation Test in Hemiparesis Is Better Barefoot at Maximal Speed. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2018, 25, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A.; Mcfadyen, B.J.; Dickey, J.P. Adaptability of the CNS in Human Walking. In Adaptability of Human Gait; Patla, A.E., Ed.; Advances in Psychology; North-Holland, 1991; Vol. 78, pp. 127–144.

- Andriacchi, T.P.; Ogle, J.A.; Galante, J.O. Walking Speed as a Basis for Normal and Abnormal Gait Measurements. J. Biomech. 1977, 10, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Gait Performance of Hemiparetic Stroke Patients: Selected Variables. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1987, 68, 777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Peat, M.; Dubo, H.I.; Winter, D.A.; Quanbury, A.O.; Steinke, T.; Grahame, R. Electromyographic Temporal Analysis of Gait: Hemiplegic Locomotion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1976, 57, 421–425. [Google Scholar]

- Brandstater, M.E.; de Bruin, H.; Gowland, C.; Clark, B.M. Hemiplegic Gait: Analysis of Temporal Variables. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1983, 64, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olney, S.J.; Griffin, M.P.; McBride, I.D. Temporal, Kinematic, and Kinetic Variables Related to Gait Speed in Subjects with Hemiplegia: A Regression Approach. Phys. Ther. 1994, 74, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, W.; Horstmann, G.; Dietz, V. Tension Development and Muscle Activation in the Leg during Gait in Spastic Hemiparesis: Independence of Muscle Hypertonia and Exaggerated Stretch Reflexes. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1984, 47, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, S.; Krajnik, J.; Luecke, D.; Jahnke, M.T.; Gregoric, M.; Mauritz, K.H. Ankle Muscle Activity before and after Botulinum Toxin Therapy for Lower Limb Extensor Spasticity in Chronic Hemiparetic Patients. Stroke 1996, 27, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamontagne, A.; Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F. Coactivation during Gait as an Adaptive Behavior after Stroke. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, M.; Basmajian, J.V.; Quanbury, A.O. Multifactorial Analysis of Walking by Electromyography and Computer. Am. J. Phys. Med. 1971, 50, 235–258. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.F.; Winter, D.A. Electromyographic Amplitude Normalization Methods: Improving Their Sensitivity as Diagnostic Tools in Gait Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1984, 65, 517–521. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsson, E. Gait Control in Hemiparesis. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1981, 13, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J.; Waters, R.L.; Perrin, T. Electromyographic Analysis of Equinovarus Following Stroke. Clin. Orthop. 1978, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, A.; Malouin, F.; Richards, C.L.; Dumas, F. Mechanisms of Disturbed Motor Control in Ankle Weakness during Gait after Stroke. Gait Posture 2002, 15, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Otter, A.R.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Mulder, T.; Duysens, J. Abnormalities in the Temporal Patterning of Lower Extremity Muscle Activity in Hemiparetic Gait. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burridge, J.H.; Wood, D.E.; Taylor, P.N.; McLellan, D.L. Indices to Describe Different Muscle Activation Patterns, Identified during Treadmill Walking, in People with Spastic Drop-Foot. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001, 23, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, S.; Gravel, D.; Arsenault, A.B.; Bourbonnais, D.; Goyette, M. Dynamometric Assessment of the Plantarflexors in Hemiparetic Subjects: Relations between Muscular, Gait and Clinical Parameters. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1997, 29, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fitts, S.S.; Hammond, M.C.; Kraft, G.H.; Nutter, P.B. Quantification of Gaps in the EMG Interference Pattern in Chronic Hemiparesis. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1989, 73, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, D.; Vanden Noven, S. Weakness in Patients with Hemiparesis. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 1989, 43, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracies, J.-M. Pathophysiology of Spastic Paresis. I: Paresis and Soft Tissue Changes. Muscle Nerve 2005, 31, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradines, M.; Ghédira, M.; Bignami, B.; Vielotte, J.; Bayle, N.; Marciniak, C.; Burke, D.; Hutin, E.; Gracies, J.-M. Do Muscle Changes Contribute to the Neurological Disorder in Spastic Paresis? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 817229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubo, H.I.; Peat, M.; Winter, D.A.; Quanbury, A.O.; Hobson, D.A.; Steinke, T.; Reimer, G. Electromyographic Temporal Analysis of Gait: Normal Human Locomotion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1976, 57, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, K.; Winter, D.A. Quantitative Assessment of Co-Contraction at the Ankle Joint in Walking. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1985, 25, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, D.L.; Martellotta, T.L.; Sullivan, D.J.; Granata, K.P.; Abel, M.F. Muscle Force Production and Functional Performance in Spastic Cerebral Palsy: Relationship of Cocontraction. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000, 81, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnithan, V.B.; Dowling, J.J.; Frost, G.; Volpe Ayub, B.; Bar-Or, O. Cocontraction and Phasic Activity during GAIT in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 36, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vinti, M.; Saikia, M.J.; Donoghue, J.; Mankodiya, K.; Kerman, K.L. A Modified Surface EMG Biomarker for Gait Assessment in Spastic Cerebral Palsy. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2021, 80, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage James R.; Schwartz Michael H.; Koop Steven E.; Novacheck Tom F. The Identification and Treatment of Gait Problems in Cerebral Palsy; Wiley.; 2009; ISBN 978-1-898683-65-0.

- Meunier, S.; Pierrot-Deseilligny, E.; Simonetta, M. Pattern of Monosynaptic Heteronymous Ia Connections in the Human Lower Limb. Exp. Brain Res. 1993, 96, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny, E.; Burke, D. The Circuitry of the Human Spinal Cord: Its Role in Motor Control and Movement Disorders; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Decq, P.; Cuny, E.; Filipetti, P.; Kéravel, Y. Role of Soleus Muscle in Spastic Equinus Foot. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1998, 352, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffenoir, K.; Decq, P.; Lefaucheur, J.-P. Interest of Peripheral Anesthetic Blocks as a Diagnosis and Prognosis Tool in Patients with Spastic Equinus Foot: A Clinical and Electrophysiological Study of the Effects of Block of Nerve Branches to the Triceps Surae Muscle. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005, 116, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindou, M.; Mertens, P. Selective Neurotomy of the Tibial Nerve for Treatment of the Spastic Foot. Neurosurgery 1988, 23, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujeau, T.; Lefaucheur, J.-P.; Slavov, V.; Gherardi, R.; Decq, P. Long Term Course of the H Reflex after Selective Tibial Neurotomy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux, M.; Buisset, N.; Daveluy, W.; Kozlowski, O.; Blond, S. Long-Term Effect of Tibial Nerve Neurotomy in Stroke Patients with Lower Limb Spasticity. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 278, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollens, B.; Deltombe, T.; Detrembleur, C.; Gustin, T.; Stoquart, G.; Lejeune, T.M. Effects of Selective Tibial Nerve Neurotomy as a Treatment for Adults Presenting with Spastic Equinovarus Foot: A Systematic Review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracies, J.-M. Coefficients of Impairment in Deforming Spastic Paresis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fève, A.; Decq, P.; Filipetti, P.; Verroust, J.; Harf, A.; N’Guyen, J.P.; Keravel, Y. Physiological Effects of Selective Tibial Neurotomy on Lower Limb Spasticity. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1997, 63, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deltombe, T.; Gustin, T. Selective Tibial Neurotomy in the Treatment of Spastic Equinovarus Foot in Hemiplegic Patients: A 2-Year Longitudinal Follow-up of 30 Cases. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamora, J.-P.; Deltombe, T.; Gustin, T. Effects of Diagnostic Tibial Nerve Block and Selective Tibial Nerve Neurotomy on Spasticity and Spastic Co-Contractions: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 55, jrm4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalard, A.; Amarantini, D.; Tisseyre, J.; Marque, P.; Gasq, D. Spastic Co-Contraction Is Directly Associated with Altered Cortical Beta Oscillations after Stroke. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, G.; Rondot, P.; Dalloz, J.C.; Tabary, J.C.; Mensch, J.; Monfraix, C. [Suggested classification of muscle stiffness of cerebral origin; research on a method for evaluating therapy]. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 1957, 97, 264–275. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).