1. Introduction

Victims that are exposed to radiation are frequently exposed to other trauma, for instance, wounds, brain injuries, bone fractures, burns, or hemorrhage (Hemo). After the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, appreciable cases of these combined injuries were detected [

1,

2]. Furthermore, many victims at the Chernobyl reactor meltdown were exposed to radiation combined with another trauma [

3]. In rodent models, combined radiation and trauma injury (CI) increased organ damage and fatality after otherwise nonlethal irradiation [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Secondary consequences to survivors of these combined injuries are known to show exacerbated acute radiation syndrome (ARS), including enteropathy (GI-ARS) associated with hematopoietic syndrome (H-ARS) [

8,

9]. Most importantly, the bone and bone marrow damage caused by CI is more than that caused by either single trauma alone [

10,

11]. The acute loss of bone mass after CI occurs because of a rapid rise in activation and activity of osteoclasts [

10] in conjunction with attenuated activity of osteoblasts [

12], resulting in decreases in formation and volume of bone [

13]. Therefore, under a nuclear attack, nuclear accident, or exposure to a radioactive dispersal device (RDD), the unfavorable decline in bone formation and volume can cause a long-term health impact in first responders and survivors [

14,

15].

Either Hemo or radiation injury (RI) can result in similar outcomes depending on the % of blood loss or the radiation dose. Hemo at 40% of total blood volume, which was classified as level 4 damage [

16] increases the concentration IL-10 and TNF-α in blood, activates NF-κB and iNOS expression in murine small intestine, and increases cell apoptosis in various murine tissues [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Likewise, sub-lethal ionizing radiation also increases these parameters [

4] in addition to initiating deleterious hematopoietic changes [

8]. Even though Hemo at 20% of total blood volume was classified as damage level 2 and causing no harm, [

16], when it occurred following radiation exposure it resulted in a 25% increase in mortality above that of radiation alone (50% mortality) or Hemo alone (0% mortality) [

6]. When the Hemo is internal, a combined radiation + Hemo condition may be difficult to diagnose. If blood cell depletion could be used as an indicator of the synergistic effects of these two traumas it would allow the diagnosis of combined radiation-Hemo injury leading to more aggressive treatment strategies than a single injury would require and thus better survival under scenarios of nuclear accidents possibly involving Hemo.

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of radiation injury (RI) followed by non-lethal Hemo (i.e., CI) on blood cell depletion to develop indicators to identify Hemo occurrence concurrently with irradiation. We hypothesize that the combined trauma of Hemo following radiation would be more detrimental to CBC depletion than either assault alone. Mice were used to test the hypothesis because studies with a whole animal include interaction among organs and molecular components of transcription factors, cytokines and microRNA that are relevant to human biology. Our data support the contention that changes in CBC depletion derived from CI mice compared to single injury mice can act as the needed indicators.

3. Discussion

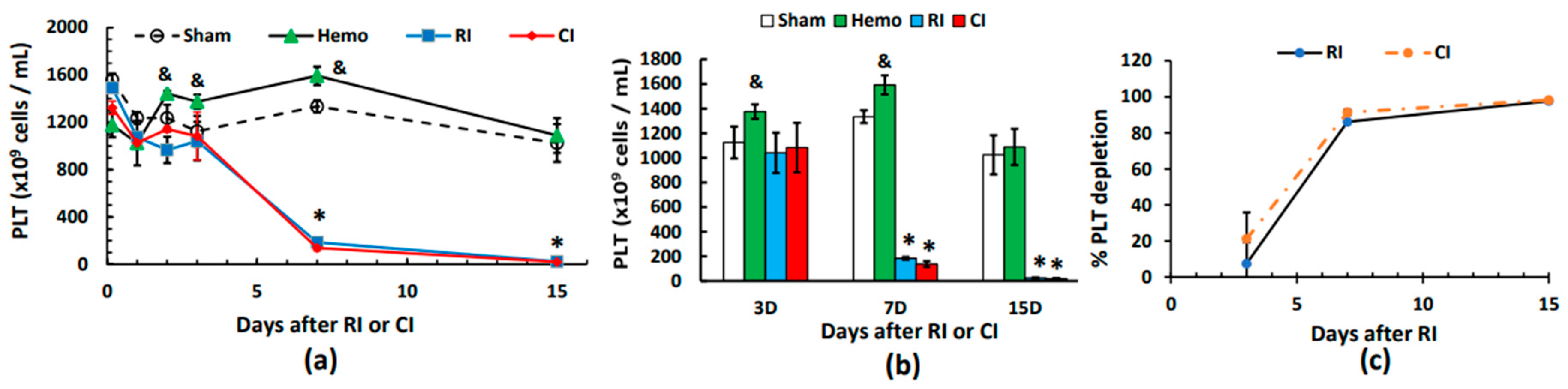

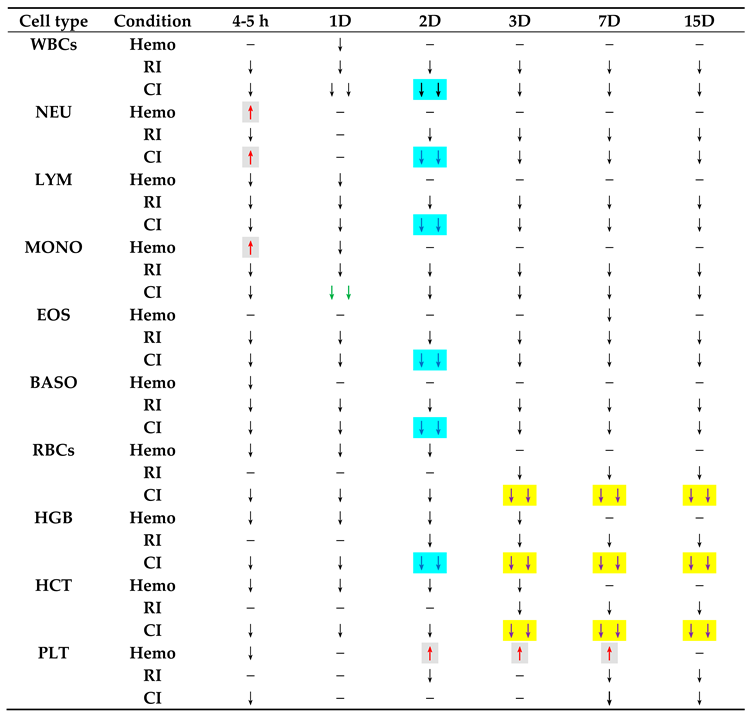

High dose radiation exposure accompanied with Hemo is one of the common CI expected after radiological exposure [

23]. Herein, we report that WBCs are early indicators (within 3 days) and RBCs are later indicators (later than 3 days up to 15 days) for radiation victims with Hemo. In contrast to WBCs and RBCs, no differential platelet depletion was found between RI and CI. This platelet result is inconsistent with that was found in combined radiation injury with wound trauma [

8], suggesting that hemorrhage trauma is less impactful to platelets compared with wounding.

Hemo at 20% of total blood volume was classified as not requiring fluid resuscitation [

16]. Hemo significantly increased neutrophils (

Figure 1c) and platelets (

Figure 7a,b); the phenomenon was similar to that after wounding because of the need of wound healing and protection against bacterial infection [

4].

RI is known to result in endothelium injury [

24,

25] that is exacerbated by CI due to upregulation of both EPO and HIF-1α [

6]. The important issue is to differentiate between the RI victims and CI victims, particularly those with internal bleedings. Our data suggest differential blood counts can be used to determine this depending on the time increments after the incident. As shown on

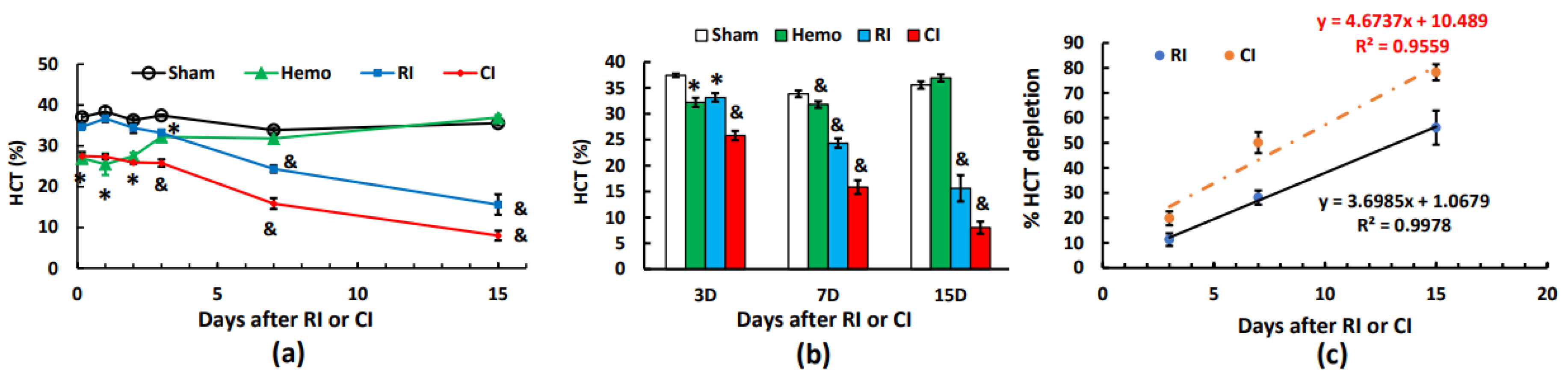

Table 1, if the blood samples were collected with 4-5 hours after the incident, Hemo victims showed increases in neutrophils and monocytes and decreases in other WBCs, RBCs and platelets; RI victims showed decreases in WBCs but not in RBCs and platelets; CI victims showed increases in neutrophils and decreases in RBCs and platelets. On day 1, Hemo victims show normal neutrophils, decreased RBCs, and normal platelets; RI victims showed decreased WBCs and normal RBCs and normal platelets; CI victims showed further decreased monocytes, and normal RBCs and platelets. On day 2, Hemo victims fully recovered WBCs but RBCs remained low and platelets were increased above the baseline; RI victims showed decreased WBCs, normal RBCs, and decreased platelets. CI victims showed further decreases in WBCs and RBCs but normal platelets. On day 3, Hemo victims showed normal WBCs, RBCs but increased platelets above the baseline; RI victims showed decreased WBCs and RBCs and normal platelets; CI showed same decreases in WBCs, and further decreased in RBCs but normal platelets. Like on day 3, on day 7, Hemo victims showed normal WBCs and RBCs but increased platelets; RI showed decreased WBCs and RBCs but increases in platelets above the basal level; CI victims appeared decreased WBCs, further declined RBCs and platelets. On day 15, Hemo victims displayed normal CBCs; RI victims appeared low in WBCs and platelets but further lower in RBCs. Collectively the data suggest that on day 1 monocyte counts can distinguish RI from CI, whereas on day 2 all WBC subgroups can separate RI from CI. From day 3 and on, RI and CI victims could be separated by severity of RBC depletion.

Due to operation and management aspects for triage during day 1 and day 2, collection of blood samples and CBC data from victims/patients will not be available in reality. Nevertheless, these samples and their data should be present during day 3, and changes in RBCs will be Could be used to distinguish the victims/patients having been exposed to nothing, Hemo, RI, or CI. The question of whether the severity of CBC depletion caused by RI or CI can be prorated to estimate the radiation dose requires further exploration. In the case of radiation combined with skin-wound trauma, the impact of CI on severity of mortality was proportional to the size of the skin-wound [

26]. However, longitudinal analysis of leukocyte total and differential count of nonhuman primates after total body irradiation [

27] indicates that this long-term effect probably presents a benefit for a triage such scenarios post-CI.

Members of the scientific community interested in responses to irradiation combined with hemorrhage should be aware that this report provides preliminary data obtained from a mouse model that may be helpful in an emergency to evaluate human victims suffering radiological accidents or nuclear detonation. This data must next be validated in minipigs or nonhuman primates to investigate if a similar change can be found and confirmed.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Ethics Statement

A facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-International (AAALACI) was used to perform the research project. Animals and their proposed procedures were under review and approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute.

5.2. Animals and Experimental Design

Male CD2F1 mice (10 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Labs (Indianapolis, IN). They were acclimated to their surroundings for 14 days before beginning the study. They were randomly placed in cages with 8 mice per cage at a temperature of 68-75ºF in a light-controlled room with a 12-hr light-dark cycle. They were randomly divided to four experimental groups with N=6/group: Sham (0 Gy), Hemorrhage (Hemo, 20% total blood volume), Radiation Injury (RI), or RI+Hemo. After Hemo, RI, or RI+Hemo, mice were placed into clean cages with 2-4 mice per cage. Proper food (standard rodent chow, Harlan Teklad 8604) and acidified water were provided to mice ad libitum. The health status of each animal was monitored and recorded daily according to the approved IACUC protocol.

5.3. Gamma Irradiation

Mice were placed in well-ventilated acrylic restrainers and exposed to a single whole-body 8.75 Gy

60Co γ-photon radiation at a dose rate of approximately 0.6 Gy/min in a

60Co facility (Nordion Inc., Otawa, Canada) at AFRRI. Dosimetry was performed using the alanine/electron paramagnetic resonance system. Calibration of the dose rate with alanine was traceable to the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Physics Laboratory of the United Kingdom. Sham-irradiated mice were placed in the same acrylic restrainers, taken to the radiation facility, and restrained for the time required for irradiation. We selected 8.75 Gy for the biomarker elucidation, because this dose has previously been studied with this mouse strain in the literature [

6,

28].

5.4. Hemorrhage (Hemo)

Within 2 hours post-RI, mice were anesthetized under isoflurane (~3%) plus 97% oxygen and bled 0% (Sham, RI) or 20% (Hemo, CI) of total blood volume via the submandibular vein as previously described [

29]. Briefly, the jaw of the anesthetized mouse was cleaned with a 70% EtOH wipe, and glycerol was applied to the surface of the jaw to allow for ease of collection and measurement of blood loss. A 5 mm Goldenrod animal lancet (MEDIpoint, Inc; Mineola, NY) for facial vein blood samples was used to puncture the submandibular vein of the mouse and heparinized hematocrit collection tubes (75 mm; Drummond Scientific Co.; Broomall, PA) were marked and used to collect the appropriate amount of blood to ensure 20% of total blood volume was extracted during the hemorrhage process. The volume of blood collected was based upon each individual mouse’s body mass [

30]. Euthanasia was conducted according to the recommendations and guidelines of the American Veterinary Medical Association at the end of each specific time-point.

5.5. Assessment of Blood Cell Profile in Peripheral Blood

For counts of blood cells (CBC) studies, mice at specific endpoints were placed under anesthesia by isoflurane inhalation (~3%) plus 97% oxygen for the entire period of blood collection. After blood collection, animals were immediately euthanized by a confirmatory cervical dislocation.

Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes 30d after RI or CI and assessed with the ADVIA 2120 Hematology System (Siemens, Deerfield, IL). Differential analysis was conducted using the peroxidase method and the light scattering techniques recommended by the manufacturer.

5.6. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM (N=6 per group per time-point). ANOVA, Bonferroni’s inequality test, and Student’s t- test were used for comparison of groups. For all data, statistical significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Figure 1.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on white blood cells and neutrophils. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 hr, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) WBC throughout 15 days; (b) WBCs on day 1 and day 2; (c) neutrophils throughout 15 days; (d) neutrophils on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; WBC: white blood cells; NEU: neutrophils; D: day.

Figure 1.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on white blood cells and neutrophils. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 hr, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) WBC throughout 15 days; (b) WBCs on day 1 and day 2; (c) neutrophils throughout 15 days; (d) neutrophils on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; WBC: white blood cells; NEU: neutrophils; D: day.

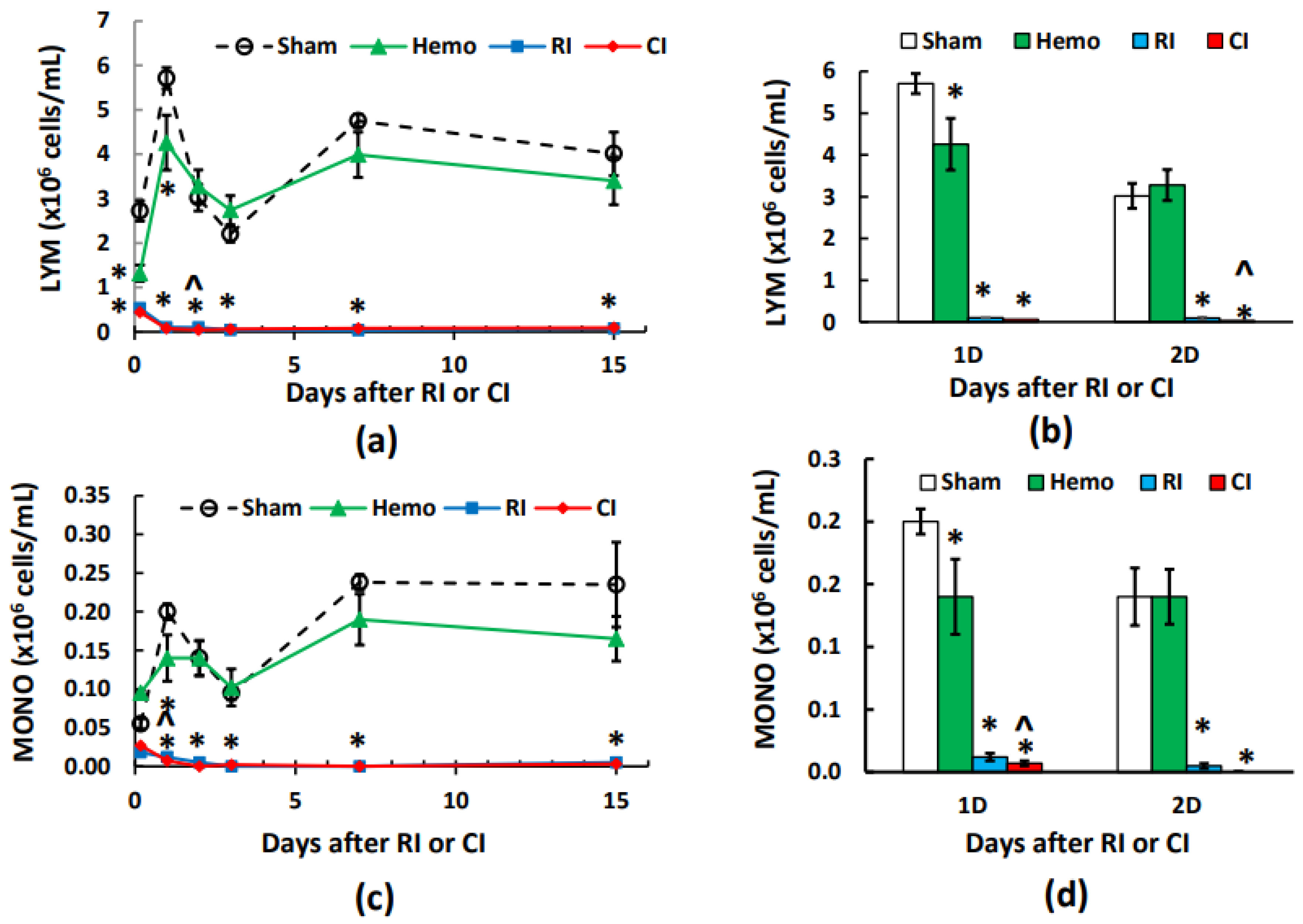

Figure 2.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on lymphocytes and monocytes. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 hr, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Lymphocytes throughout 15 days; (b) Lymphocytes on day 1 and day 2; (c) Monocytes throughout 15 days; (d) Monocytes on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; LYM: lymphocytes; MONO: monocytes; D: day.

Figure 2.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on lymphocytes and monocytes. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 hr, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Lymphocytes throughout 15 days; (b) Lymphocytes on day 1 and day 2; (c) Monocytes throughout 15 days; (d) Monocytes on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; LYM: lymphocytes; MONO: monocytes; D: day.

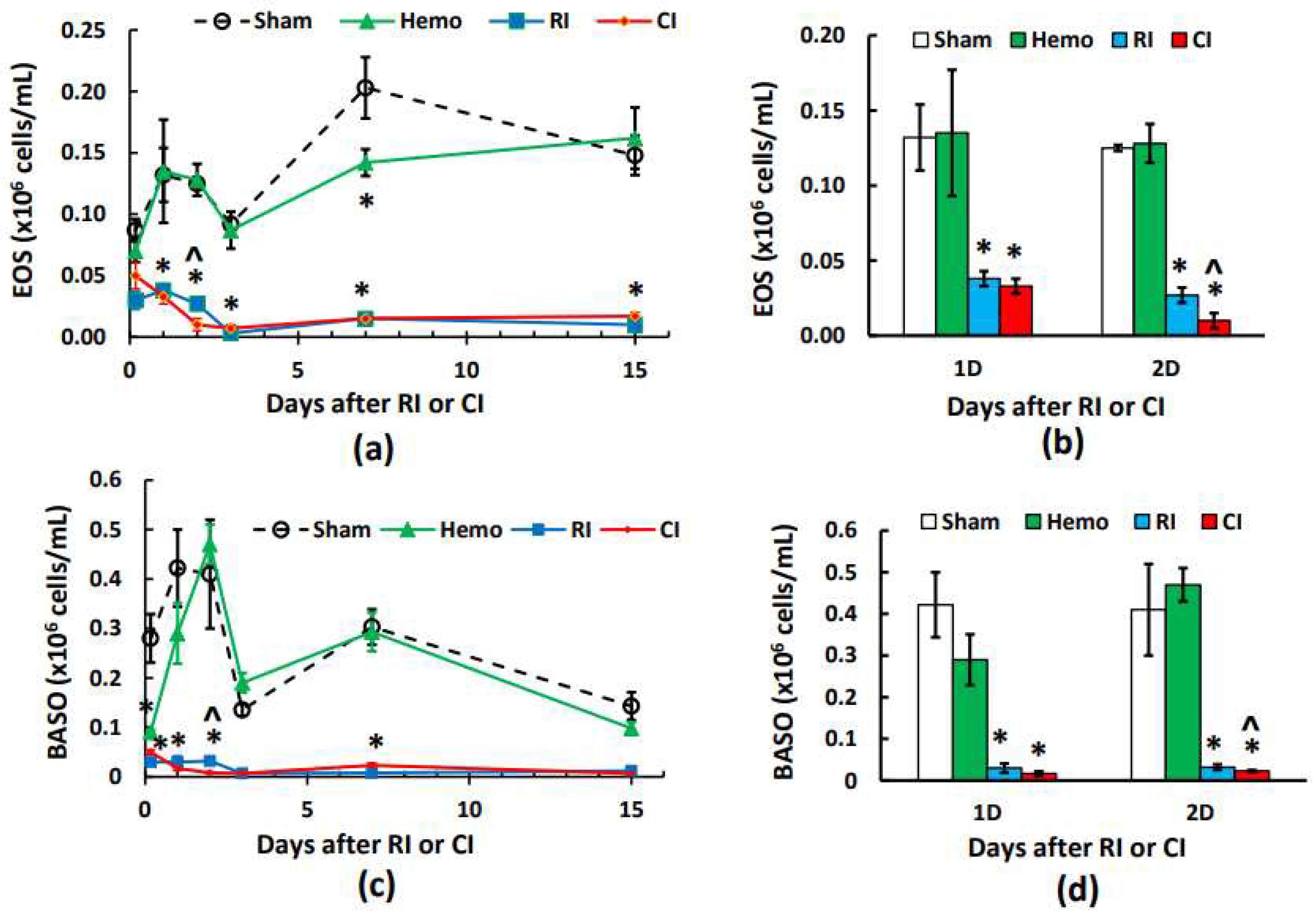

Figure 3.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on eosinophils and basophils. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Eosinophils throughout 15 days; (b) Eosinophils on day 1 and day 2; (c) Basophils throughout 15 days; (d) Basophils on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; EOS: eosinophils; BASO: basophils; D: day.

Figure 3.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on eosinophils and basophils. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Eosinophils throughout 15 days; (b) Eosinophils on day 1 and day 2; (c) Basophils throughout 15 days; (d) Basophils on day 1 and day 2. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; ^p<0.05 vs. Sham, Hemo, and RI at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; EOS: eosinophils; BASO: basophils; D: day.

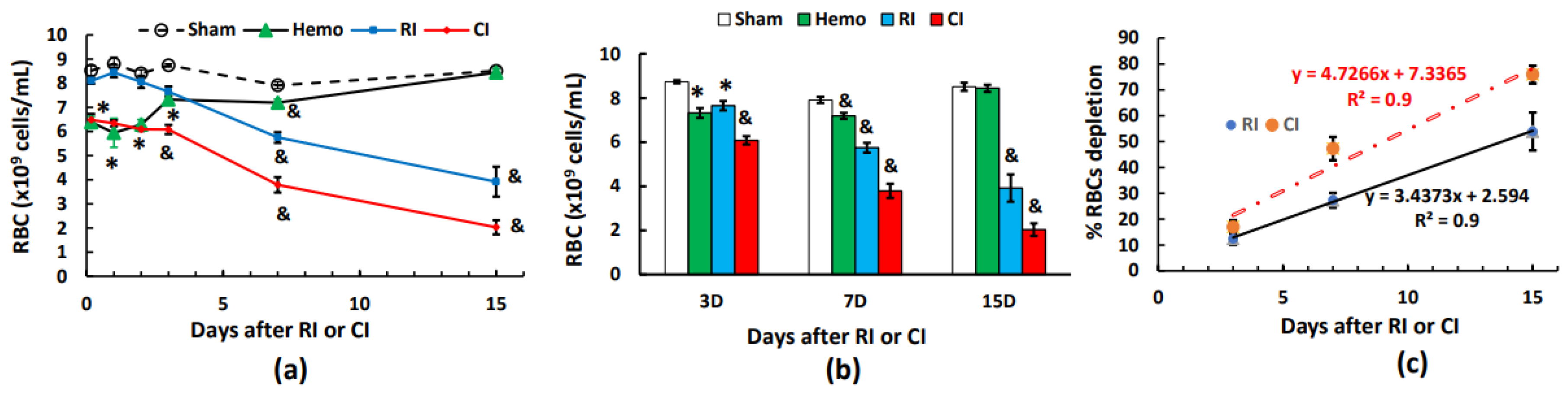

Figure 4.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on red blood cells. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Red blood cells throughout 15 days; (b) Red blood cells on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Red blood cells on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 4.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on red blood cells. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Red blood cells throughout 15 days; (b) Red blood cells on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Red blood cells on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

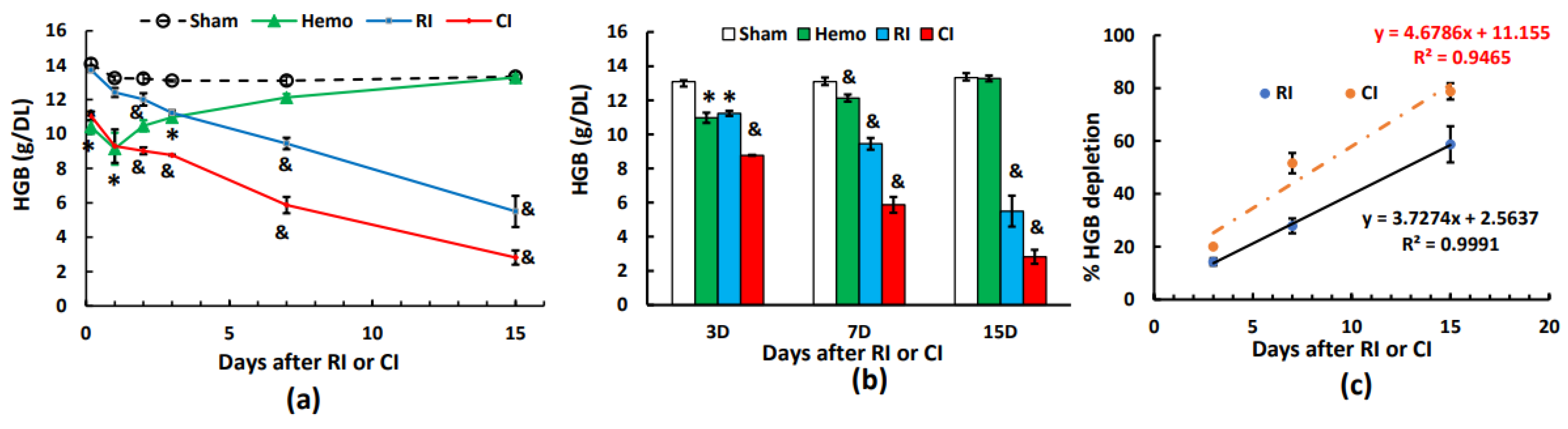

Figure 5.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on hemoglobin levels. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Hemoglobin levels throughout 15 days; (b) Hemoglobin levels on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Hemoglobin levels on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 5.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on hemoglobin levels. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Hemoglobin levels throughout 15 days; (b) Hemoglobin levels on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Hemoglobin levels on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 6.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on hematocrit readings. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Hematocrit readings throughout 15 days; (b) Hematocrit readings on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Hematocrit readings on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20%; HCT: hematocrits; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 6.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on hematocrit readings. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Hematocrit readings throughout 15 days; (b) Hematocrit readings on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Hematocrit readings on days 3, 7, and 15 with slops for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20%; HCT: hematocrits; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 7.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on platelets. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Platelets throughout 15 days; (b) Platelets on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Platelets on days 3, 7, and 15 with a non-linear relationship for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Figure 7.

Effects of radiation alone or combined radiation injury with hemorrhage on platelets. Animals were exposed to 8.75 Gy alone or followed by 20% hemorrhage. Complete blood cells were counted in blood collected in sham mice, Hemo alone mice, radiation alone mice, or radiation+Hemo mice at 4-5 h, and on days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 15. Data are mean±sem with N=6 per group per time point. (a) Platelets throughout 15 days; (b) Platelets on days 1, 2, and day 3; (c) Platelets on days 3, 7, and 15 with a non-linear relationship for RI and CI, respectively. *p<0.05 vs. Sham group; &p<0.05 vs. the rest 3 groups at the specific time point. Hemo: 20% hemorrhage; RI: 8.75 Gy; CI: 8.75 Gy+20% hemorrhage; RBC: red blood cells; D: day; R2: correlation coefficient.

Table 1.

Relative CBC changes to respective sham groups on different time points.

Table 1.

Relative CBC changes to respective sham groups on different time points.