1. Introduction

Leptospira, major agents of zoonotic disease, cause considerable morbidity and, in some instances, significant mortality in humans [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The genus

Leptospira comprises over 20 species based on DNA relatedness, with more than 350 serovars identified based on surface agglutinating lipopolysaccharide antigens [

7]. These species are broadly categorized into three groups. Saprophytic species like

Leptospira biflexa are not associated with disease. Pathogenic species such as

Leptospira interrogans and

Leptospira borgpetersenii cause leptospirosis globally, ranging from mild or asymptomatic infection to severe forms resulting in multiple organ failure and death. An intermediate group, including

Leptospira fainei and

Leptospira licerasiae, may be associated with infection and mild disease.

Despite the clinical significance of leptospirosis, there is a notable lack of comprehensive data regarding the protective mechanisms employed by leptospires against antibiotics and phages.

Leptospira spp. exhibit intrinsic resistance to various antimicrobial agents, though the specific mechanisms responsible remain unidentified [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, resistance to sulfonamides, neomycin, actidione, polymyxin, nalidixic acid, vancomycin, and rifampicin has facilitated the development of selective media for isolating leptospires [

10].

Current recommendations for treating human leptospirosis involve penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime [

1,

11]. Alternatives, particularly for those with allergies or in non-hospital settings, include oral doxycycline or azithromycin. In veterinary settings, a penicillin-streptomycin combination is the preferred therapy for acute leptospirosis, although ampicillin, amoxicillin, tetracyclines, tulathromycin, and third-generation cephalosporins have also been utilized [

12]. Tilmicosin presents an additional alternative [

13].

Renewed interest in bacteriophages as alternatives to antibiotics and their role in bacterial evolution has emerged, yet little is known about phage diversity within the

Leptospira genus [

14,

15].

Saint Girons et al. first isolated bacteriophages from

Leptospira species in 1990, but their exploration remains limited [

16]. Schiettekatte et al. demonstrated that leptophages utilize lipopolysaccharides (LPS) as receptors on bacterial cells [

15]. Bacteria engage in a continuous arms race, evolving defence mechanisms against the expanding arsenal of phage weapons [

17]. These defence systems, discovered in recent years, protect against phage through various molecular mechanisms. Anti-phage defence systems exhibit a non-random distribution in microbial genomes, often forming "defence islands" where multiple systems cluster together [

18,

19,

20].

The strain FDAARGOS_203, being a reference strain, provides a unique opportunity to explore the genetic basis of antibiotic and phage resistance in Leptospira interrogans. Through a comprehensive examination of the genome, we aim to contribute valuable insights into the genetic factors governing AMR and anti-phage defence, enhancing our understanding of leptospirosis and paving the way for more effective therapeutic interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The genome of

Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain FDAARGOS_203 was downloaded in FASTA format files from the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) database (GenBank: GCA_002073495.2) [

21]. Leptospiral genome was annotated using RAST tool kit (RASTtk) [

22].

2.2. Detection of AMR Genes

The genomes were then analyzed using the PATRIC tool from the BV-BRC to identify antimicrobial resistance genes [

23]. The Genome Annotation Service in PATRIC uses k-mer-based AMR genes detection method, which utilizes PATRIC’s curated collection of representative AMR gene sequence variants, and assigns to each AMR gene functional annotation, broad mechanism of antibiotic resistance.

2.3. Detection of Antiviral Systems

DefenseFinder was used to identify anti-phage defense systems [

24]. DefenseFinder utilizes MacSyFinder27, a program dedicated to the detection of macromolecular systems, functioning with one model per system [

25]. This approach involves a two-step process: first, the detection of all proteins involved in a macromolecular system through a homology search using Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles; second, the application of decision rules to retain only the HMM hits that satisfy the genetic architecture of the system of interest. Genomic features such as phage and genomic island sequences were recognized using online bioinformatic tools such as Island Viewer.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

The closest reference and representative genomes were identified by Mash/MinHash [

26]. PATRIC global protein families (PGFams) were selected from these genomes to determine the phylogenetic placement of this genome [

27]. The protein sequences from these families were aligned with MUSCLE, and the nucleotides for each of those sequences were mapped to the protein alignment [

28]. The joint set of amino acid and nucleotide alignments were concatenated into a data matrix, and RaxML was used to analyze this matrix, with fast bootstrapping was used to generate the support values in the tree [

29].

2.5. Figures and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using SRplot and jvenn [

30,

31].

3. Results

3.1. Genome Assembly and Annotation

The Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain FDAARGOS_203 genome was assembled and analyzed for its genetic content. The assembly consisted of 2 contigs, totaling 4,630,574 base pairs, with an average G+C content of 35.05% (

Table 1).

Quality control measures, such as removal of low-quality reads and trimming of adapters, were performed prior to assembly. The genome was then annotated using RAST tool kit (RASTtk) and assigned a unique genome identifier of 173.581. The genome contained 4,479 protein-coding sequences (CDS), 37 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 3 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes. The annotation revealed 2,305 hypothetical proteins and 2,174 proteins with functional assignments (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

The genome exhibited a variety of proteins with Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, Gene Ontology (GO) assignments, and proteins mapped to KEGG pathways, contributing to the overall functional diversity (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Protein Features.

Table 3.

Protein Features.

| Feature |

Value |

| Hypothetical proteins |

671 |

| Proteins with functional assignments |

556 |

| Proteins with EC number assignments |

517 |

| Proteins with GO assignments |

4,061 |

| Proteins with Pathway assignments |

4,160 |

| Proteins with PATRIC genus-specific family (PLfam) assignments |

671 |

| Proteins with PATRIC cross-genus family (PGfam) assignments |

556 |

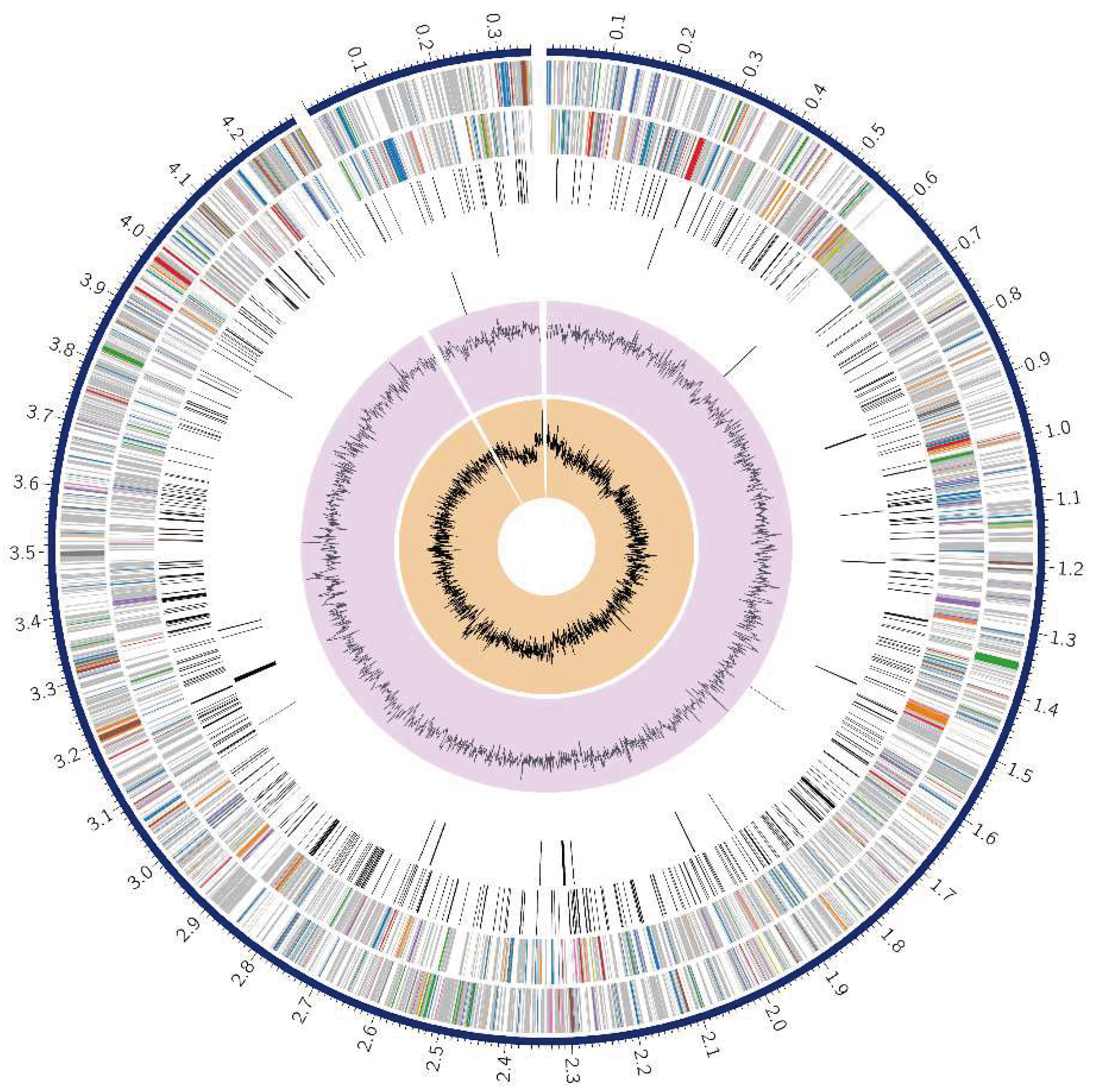

A circular graphical representation displayed the genome annotations, including contigs, CDS on the forward and reverse strands, RNA genes, and features related to antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors (

Figure 1).

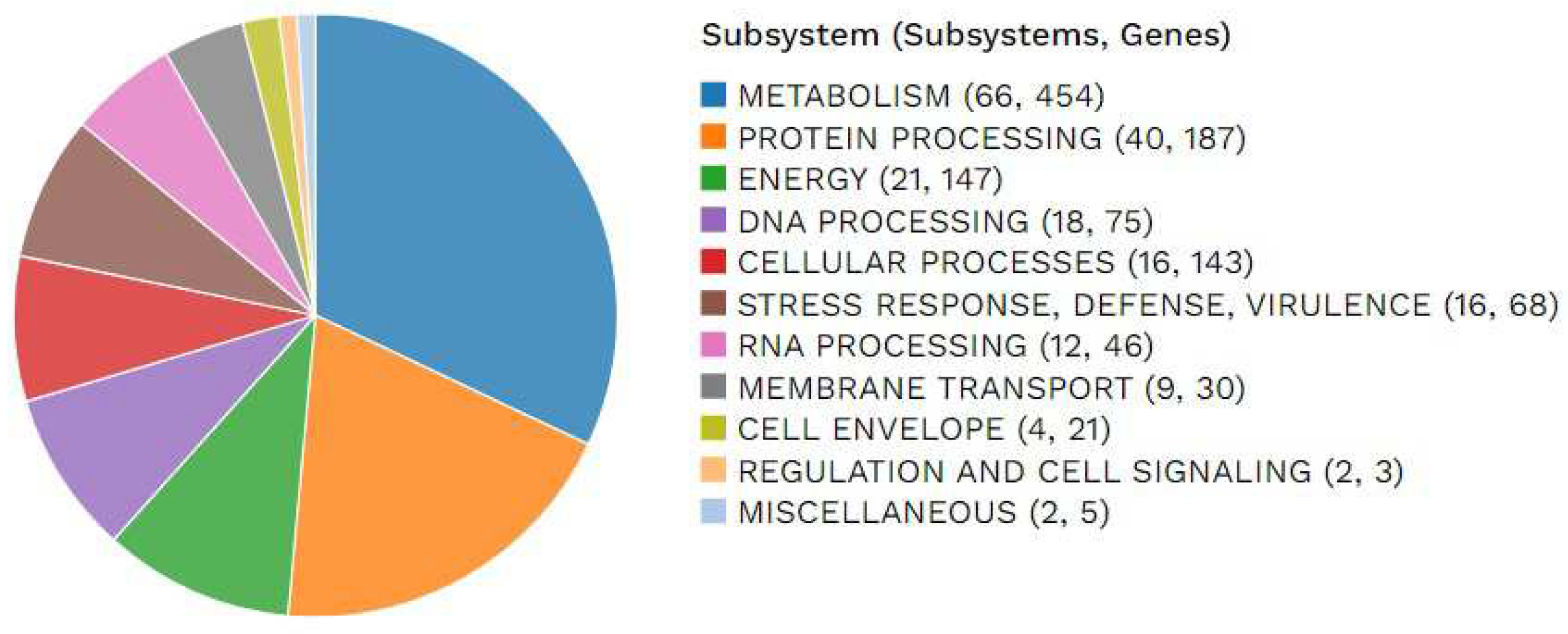

The distribution of subsystems unique to this genome was illustrated, providing an overview of its functional organization (

Figure 2).

3.2. Specialty Genes

Several genes annotated in the genome demonstrated homology to known transporters, virulence factors, drug targets, and antibiotic resistance genes. Specifically, 22 antibiotic resistance genes were identified using the PATRIC database, along with one drug target and 67 transporter genes (

Table 4). The antibiotic resistance genes targeted various essential cellular functions, such as cell wall synthesis, DNA replication, and protein synthesis (

Table 4).

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

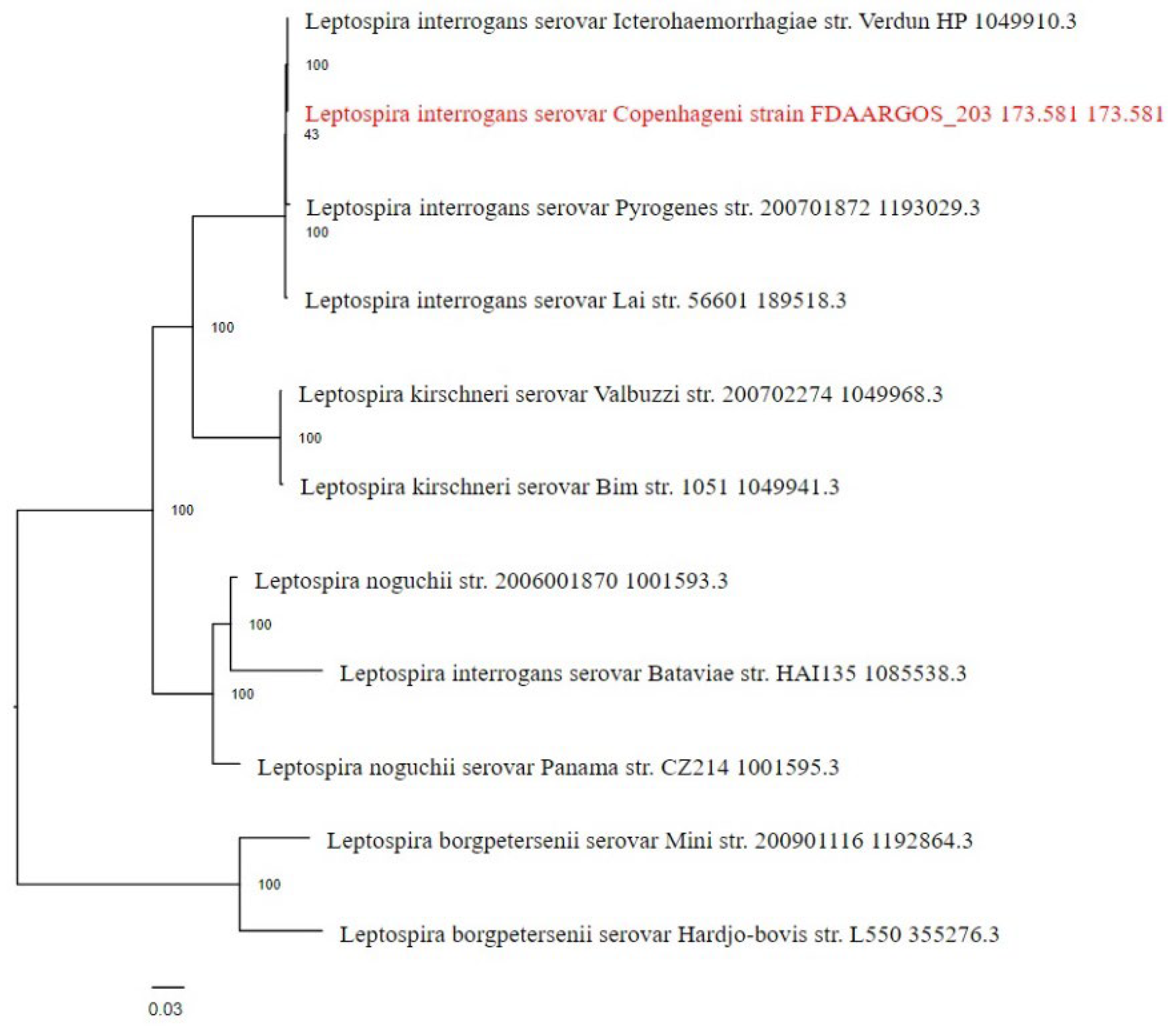

The phylogenetic placement of the Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain FDAARGOS_203 genome was determined using reference and representative genomes. The analysis, conducted with RaxML and fast bootstrapping, identified closely related genomes based on Mash/MinHash comparisons. The resulting tree (

Figure 3) provides insights into the evolutionary relationships of this strain within the broader context of Leptospira species.

3.4. Anti-Phage Systems

The genome analysis also revealed the presence of various anti-phage defense systems. Multiple defense islands, housing systems such as RM_Type_IV, PrrC, Borvo, CAS_Class1-Subtype-IC, CAS_Class1-Subtype-IB. These defense mechanisms likely play a crucial role in protecting the bacterium from phage attacks and contribute to its survival in various environments.

3.5. AMR Genes

A study of the genome of the Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain FDAARGOS_203 showed a group of genes that are resistant to antibiotics. These genes target essential cellular functions, including protein synthesis, DNA replication, and cell wall synthesis. Notably, the gidB gene was identified, suggesting its role in conferring resistance through absence. Additionally, GdpD and PgsA genes were associated with altering cell wall charge, contributing to antibiotic resistance (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Our study was conducted to analyze for the first time the genome of a reference strain of Leptospira for the presence of anti-phage systems and mechanisms of resistance to antibiotics. This study provides a solid foundation for initiating new research in this field.

We identified only two studies that investigated

Leptospira anti-phage systems, both of which focused solely on Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPRs) and their subtypes [

32,

33]. CRISPR Types I and III are considered dominant for

Leptospira. However, our discovery revealed additional methods of protection against leptophages, specifically RM_Type_IV, PrrC, and Borvo.

The detection of Type IV restriction-modification (R-M) system is particularly interesting. R-M systems, the most studied class of defense systems since their discovery in the 1960s, recognize specific DNA motifs and are categorized into four broad types (I–IV) [

34]. Type IV R-M systems have only a restriction endonuclease (REase) that cleaves foreign DNA with methylation at the same site as the recognition motif [

35]. The finding of Type IV requires further research.

If the R-M system is compromised by a phage inhibitor as the primary defense, PrrC can still provide a secondary line of defense [

36]. PrrC is an anticodon nuclease that specifically targets tRNALys, inhibiting protein synthesis and leading to cell death [

37,

38,

39]. Borvo, which possesses a CHAT protease domain protein, results in cell death despite its unknown mechanism of immunity [

40].

Leptospires have evolved several defense mechanisms against bacteriophages, and CRISPR is just one of them. Our findings make a significant contribution to future research, particularly for the development of potential drugs for treating leptospirosis in animals or humans.

Additionally, we identified 20 genes responsible for leptospirosis resistance to antibiotics. The apparent absence of significant antimicrobial resistance emergence in Leptospira raises the question of why this has not occurred (18). Speculatively, in the environment, leptospires coexist with numerous bacterial species, but the lack of therapeutically useful antimicrobial agents results in minimal selective pressure (19). Leptospiral infections are typically monomicrobial, limiting opportunities for horizontal resistance gene acquisition. Moreover, there is no experimental evidence of foreign DNA uptake by Leptospira spp., although genomic analyses support this notion. Finally, human leptospirosis is a dead-end infection, with human-to-human transmission being extremely rare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K. and P.P.; software, P.P.; validation, O.K. and P.P.; formal analysis, O.K.; investigation, P.P.; data curation, P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P. and O.K.; writing—review and editing, V.O.; visualization, P.P.; supervision, O.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adler B, de la Peña Moctezuma A. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Vet Microbiol. 2010, 140, 287–296. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petakh, P.; Isevych, V.; Kamyshnyi, A.; Oksenych, V. Weil's Disease-Immunopathogenesis, Multiple Organ Failure, and Potential Role of Gut Microbiota. Biomolecules. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Isevych, V.; Griga, V.; Kamyshnyi, A. The risk factors of severe leptospirosis in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine–search for „red flags”. Arch Balk Med Union. 2022, 57, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Isevych, V.; Mohammed, I.B.; Nykyforuk, A.; Rostoka, L. Leptospirosis: Prognostic Model for Patient Mortality in the Transcarpathian Region, Ukraine. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, NY). 2022, 22, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petakh, P.; Nykyforuk, A. Predictors of lethality in severe leptospirosis in Transcarpathian region of Ukraine. Le infezioni in medicina. 2022, 30, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petakh, P.; Rostoka, L.; Isevych, V.; Kamyshnyi, A. Identifying risk factors and disease severity in leptospirosis: A meta-analysis of clinical predictors. Tropical doctor. 2023, 53, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouts, D.E.; Matthias, M.A.; Adhikarla, H.; Adler, B.; Amorim-Santos, L.; Berg, D.E.; et al. What Makes a Bacterial Species Pathogenic?:Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Genus Leptospira. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016, 10, e0004403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, B.; Faine, S.; Christopher, W.L.; Chappel, R.J. Development of an improved selective medium for isolation of leptospires from clinical material. Vet Microbiol. 1986, 12, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod Kumar, K.; Lall, C.; Raj, R.V.; Vedhagiri, K.; Sunish, I.P.; Vijayachari, P. In Vitro Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Pathogenic Leptospira Biofilm. Microbial drug resistance (Larchmont, NY). 2016, 22, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberg, A. Studies on the effect of antibiotic substances on leptospires and their cultivation from material with a high bacterial count. Zentralblatt fur Bakteriologie 1 Abt Originale A: Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Infektionskrankheiten und Parasitologie. 1981, 249, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haake, D.A.; Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis in humans. J Leptospira leptospirosis.

- Ellis, W.A. Animal leptospirosis. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2015, 387, 99–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alt, D.P.; Zuerner, R.L.; Bolin, C.A. Evaluation of antibiotics for treatment of cattle infected with Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar hardjo. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2001, 219, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doss, J.; Culbertson, K.; Hahn, D.; Camacho, J.; Barekzi, N. A Review of Phage Therapy against Bacterial Pathogens of Aquatic and Terrestrial Organisms. Viruses 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiettekatte, O.; Vincent, A.T.; Malosse, C.; Lechat, P.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Veyrier, F.J.; et al. Characterization of LE3 and LE4, the only lytic phages known to infect the spirochete Leptospira. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 11781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girons, I.S.; Margarita, D.; Amouriaux, P.; Baranton, G. First isolation of bacteriophages for a spirochaete: Potential genetic tools for Leptospira. Research in Microbiology. 1990, 141, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernheim, A.; Sorek, R. The pan-immune system of bacteria: Antiviral defence as a community resource. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2020, 18, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, S.; Melamed, S.; Ofir, G.; Leavitt, A.; Lopatina, A.; Keren, M.; et al. Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science 2018, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. Comparative genomics of defense systems in archaea and bacteria. Nucleic acids research. 2013, 41, 4360–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochhauser, D.; Millman, A.; Sorek, R. The defense island repertoire of the Escherichia coli pan-genome. PLoS genetics. 2023, 19, e1010694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available from: https://www.bv-brc.org/.

- Brettin, T.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; et al. RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattam, A.R.; Davis, J.J.; Assaf, R.; Boisvert, S.; Brettin, T.; Bun, C.; et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial Bioinformatics Database and Analysis Resource Center. Nucleic acids research. 2017, 45, D535–d42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abby, S.S.; Néron, B.; Ménager, H.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. MacSyFinder: A Program to Mine Genomes for Molecular Systems with an Application to CRISPR-Cas Systems. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e110726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesson, F.; Hervé, A.; Mordret, E.; Touchon, M.; d’Humières, C.; Cury, J.; et al. Systematic and quantitative view of the antiviral arsenal of prokaryotes. Nature Communications. 2022, 13, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; et al. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome biology. 2016, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.J.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Shukla, M.; et al. PATtyFams: Protein Families for the Microbial Genomes in the PATRIC Database. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic acids research. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A.; Hoover, P.; Rougemont, J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Systematic biology. 2008, 57, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; et al. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardou, P.; Mariette, J.; Escudié, F.; Djemiel, C.; Klopp, C. jvenn: An interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senavirathna, I.; Jayasundara, D.; Warnasekara, J.; Matthias, M.A.; Vinetz, J.M.; Agampodi, S. Complete genome sequences of twelve strains of Leptospira interrogans isolated from humans in Sri Lanka. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2023, 113, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Yi, Y.; Che, R.; Zhang, Q.; Imran, M.; Khan, A.; et al. Characterization of CRISPR-Cas systems in Leptospira reveals potential application of CRISPR in genotyping of Leptospira interrogans. APMIS : Acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2019, 127, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.P.; Rocha, E.P.C.; MacLean, R.C. Restriction-modification systems have shaped the evolution and distribution of plasmids across bacteria. Nucleic acids research. 2023, 51, 6806–6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, M.; Mao, C.; Wang, C.; Yuan, P.; Wang, T.; et al. A Type I Restriction Modification System Influences Genomic Evolution Driven by Horizontal Gene Transfer in Paenibacillus polymyxa. 2021, 12.

- Gao, Z.; Feng, Y. Bacteriophage strategies for overcoming host antiviral immunity. 2023, 14.

- Kaufmann, G.; David, M.; Borasio, G.D.; Teichmann, A.; Paz, A.; Amitsur, M.; et al. Phage and host genetic determinants of the specific anticodon loop cleavages in bacteriophage T4-infected Escherichia coli CTr5X. Journal of molecular biology. 1986, 188, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirotkin, K.; Cooley, W.; Runnels, J.; Snyder, L.R. A role in true-late gene expression for the T4 bacteriophage 5′ polynucleotide kinase 3′ phosphatase. Journal of molecular biology. 1978, 123, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huiting, E.; Bondy-Denomy, J. Defining the expanding mechanisms of phage-mediated activation of bacterial immunity. Current opinion in microbiology. 2023, 74, 102325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, A.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Doron, S.; Bernheim, A.; Hör, J.; et al. An expanded arsenal of immune systems that protect bacteria from phages. Cell Host & Microbe. 2022, 30, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).