Submitted:

12 February 2024

Posted:

14 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Patient history

1.2. Physical examination

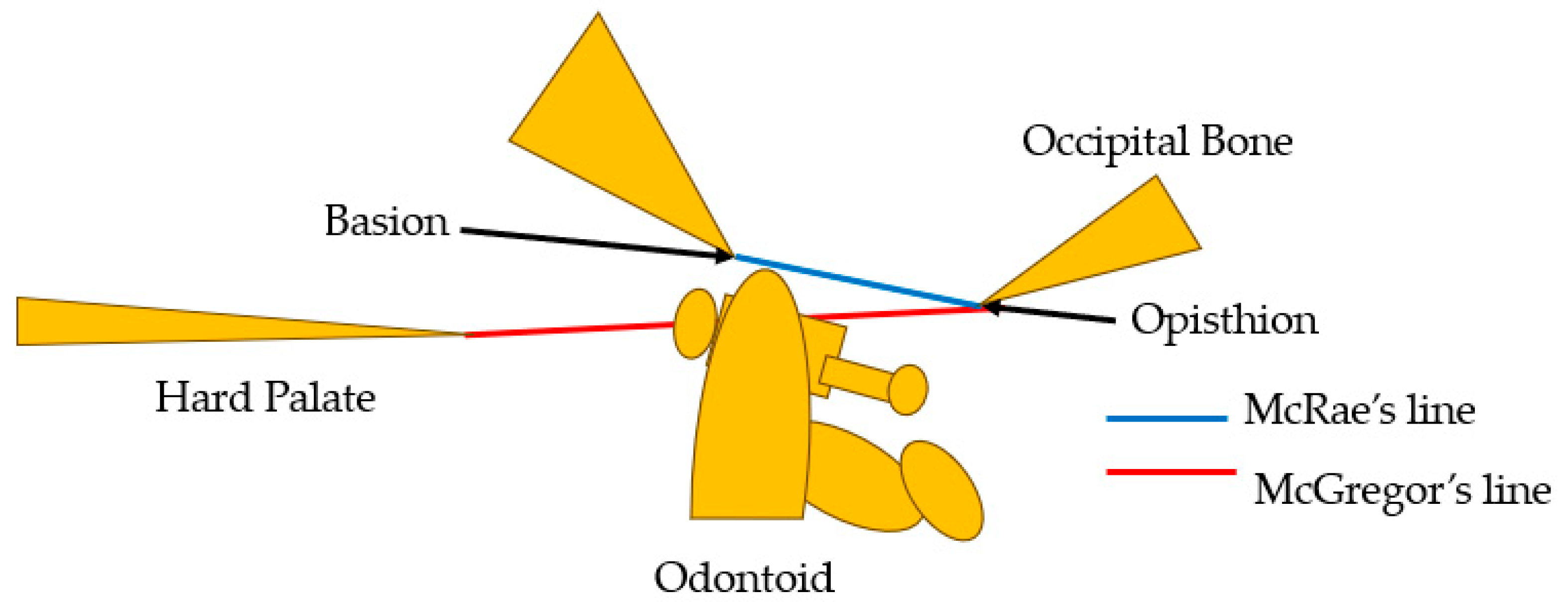

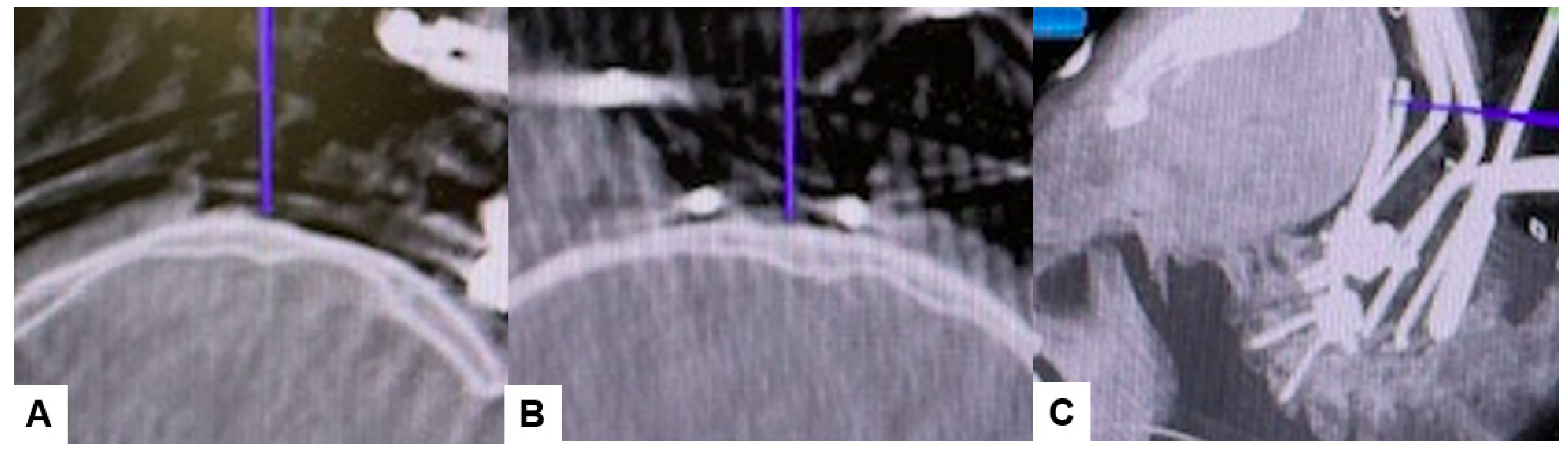

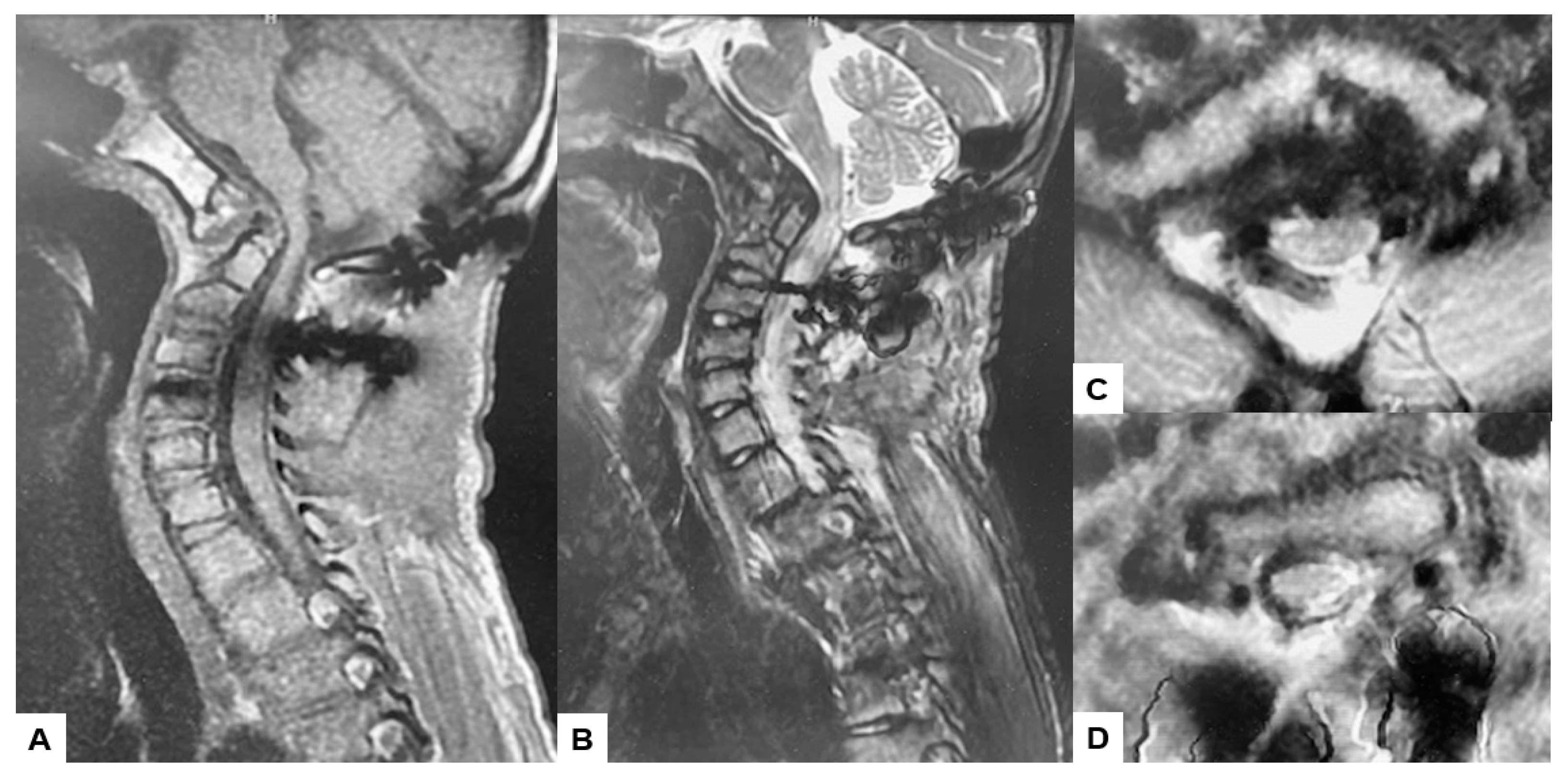

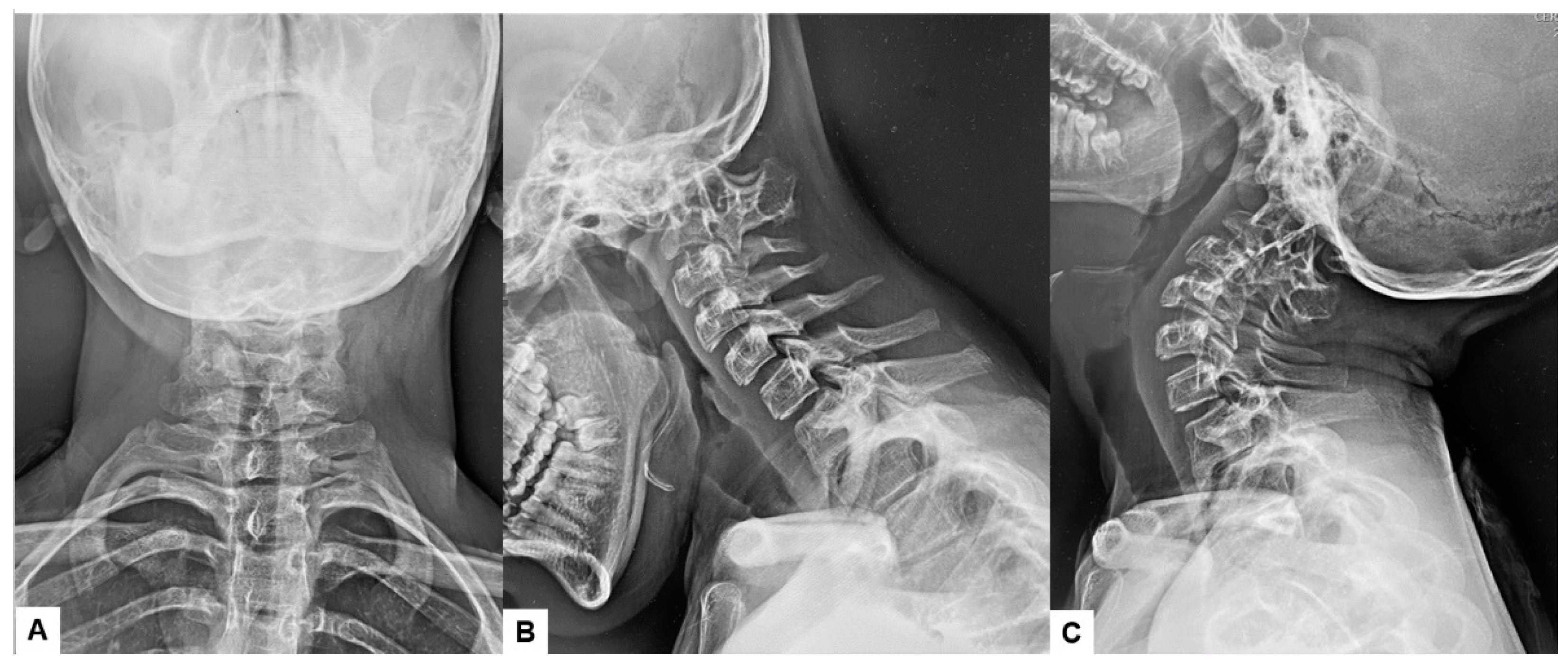

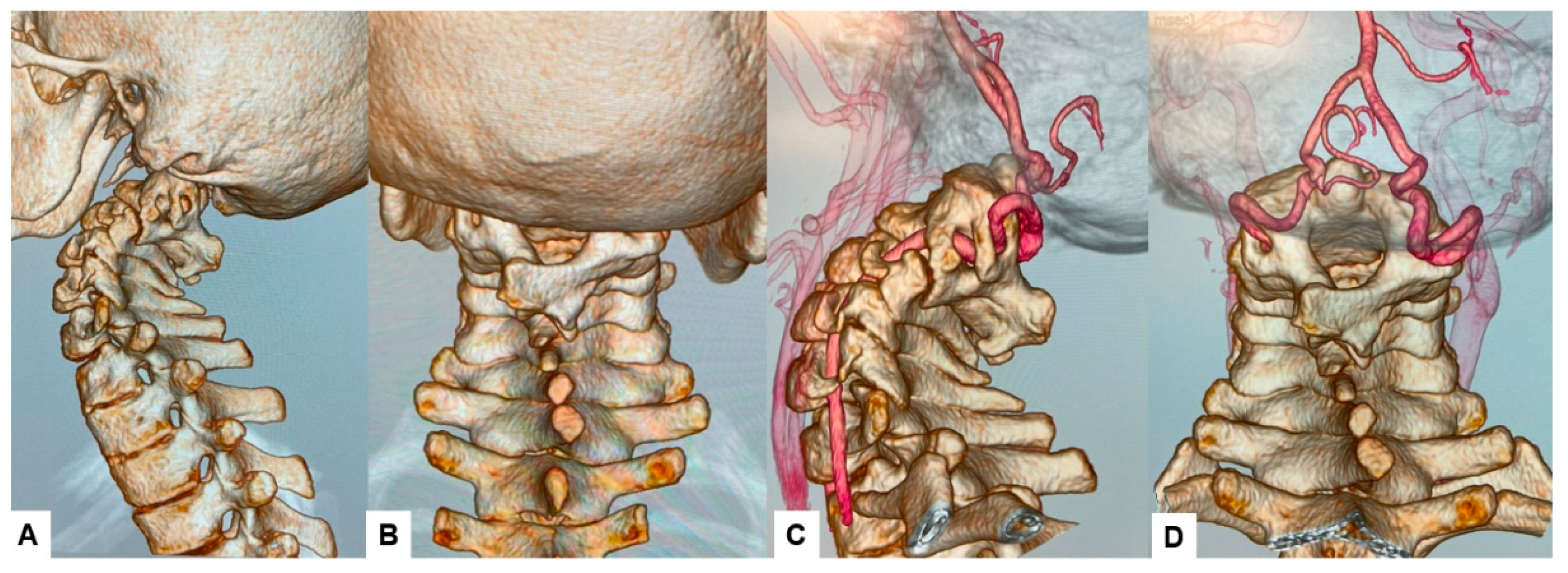

1.3. Preoperative imaging

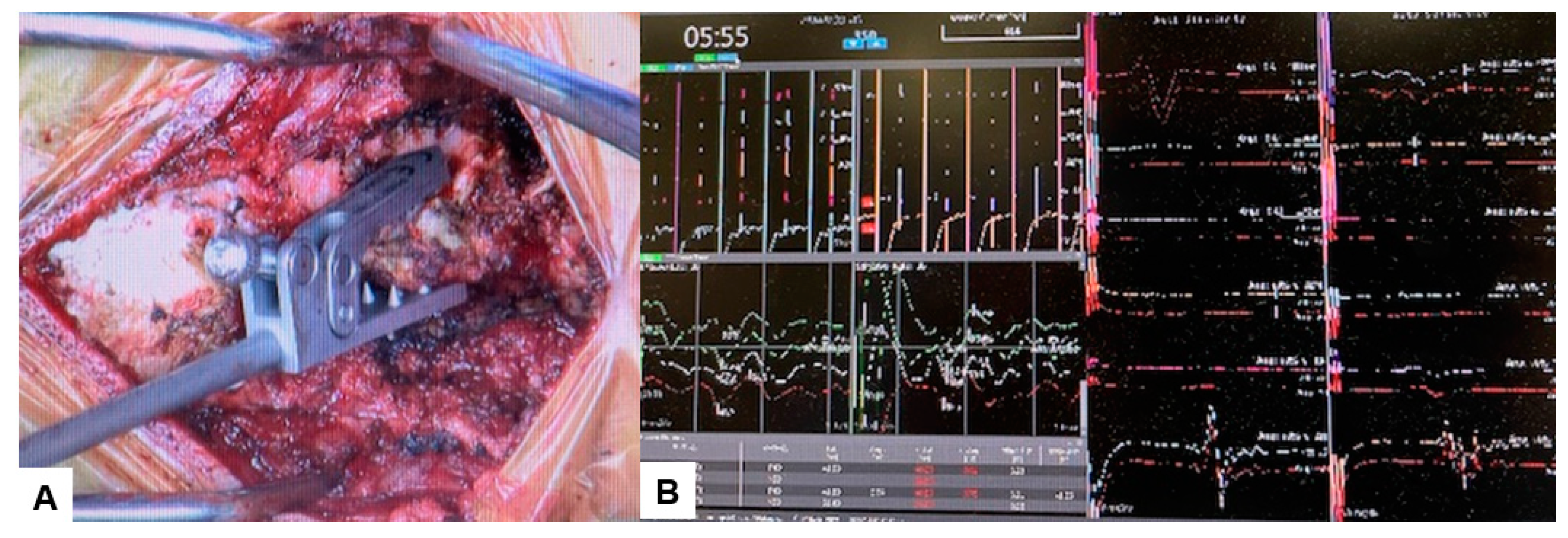

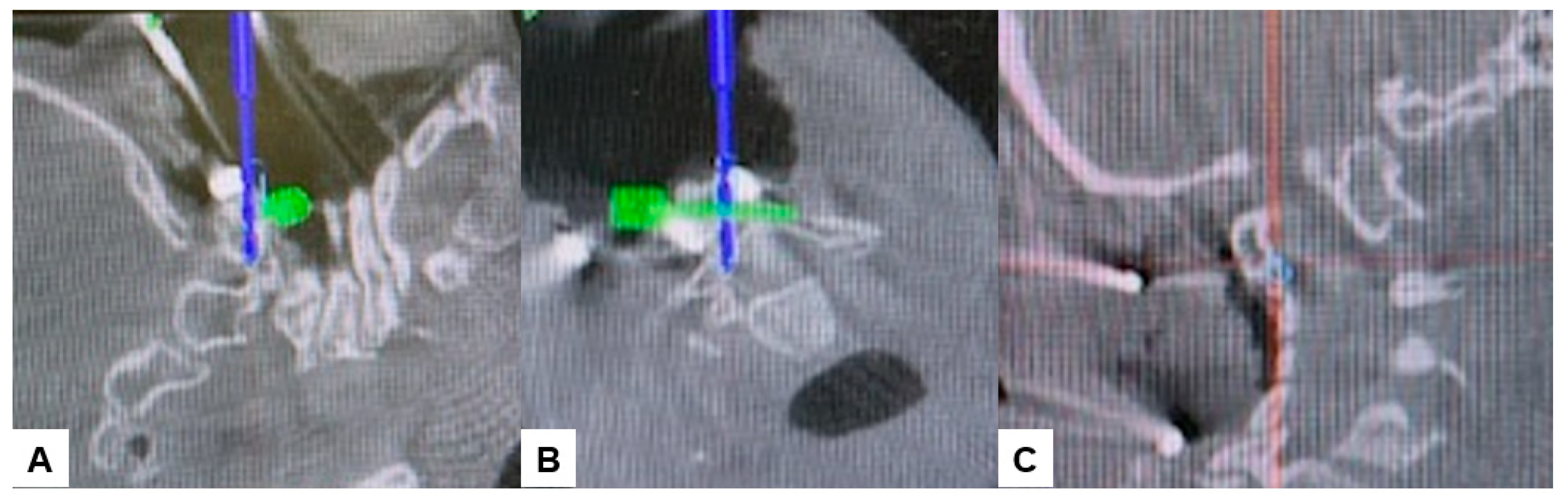

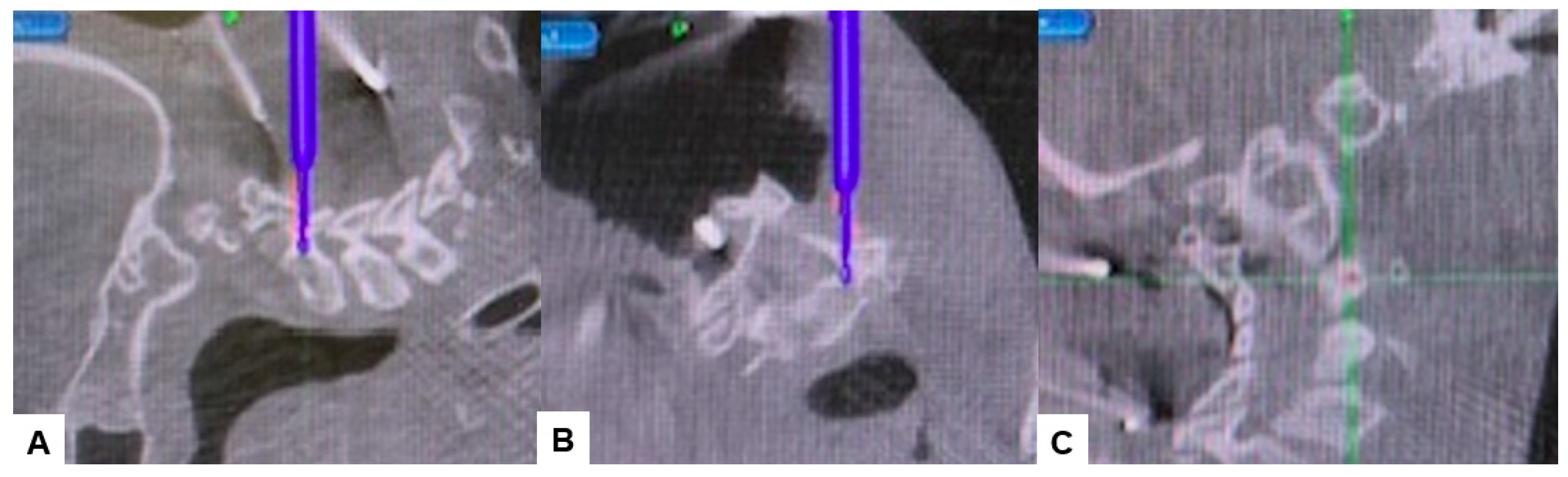

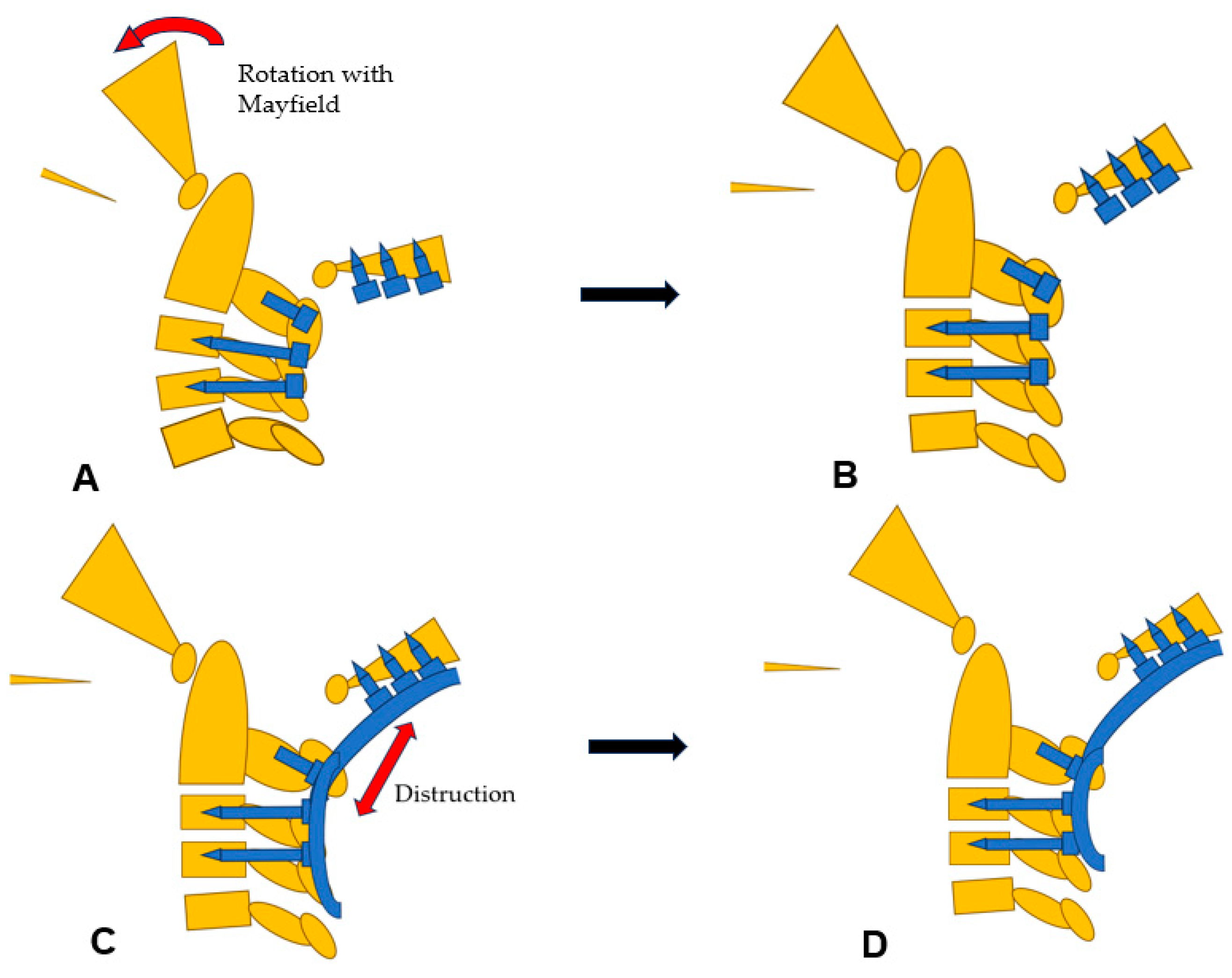

1.4. Surgery

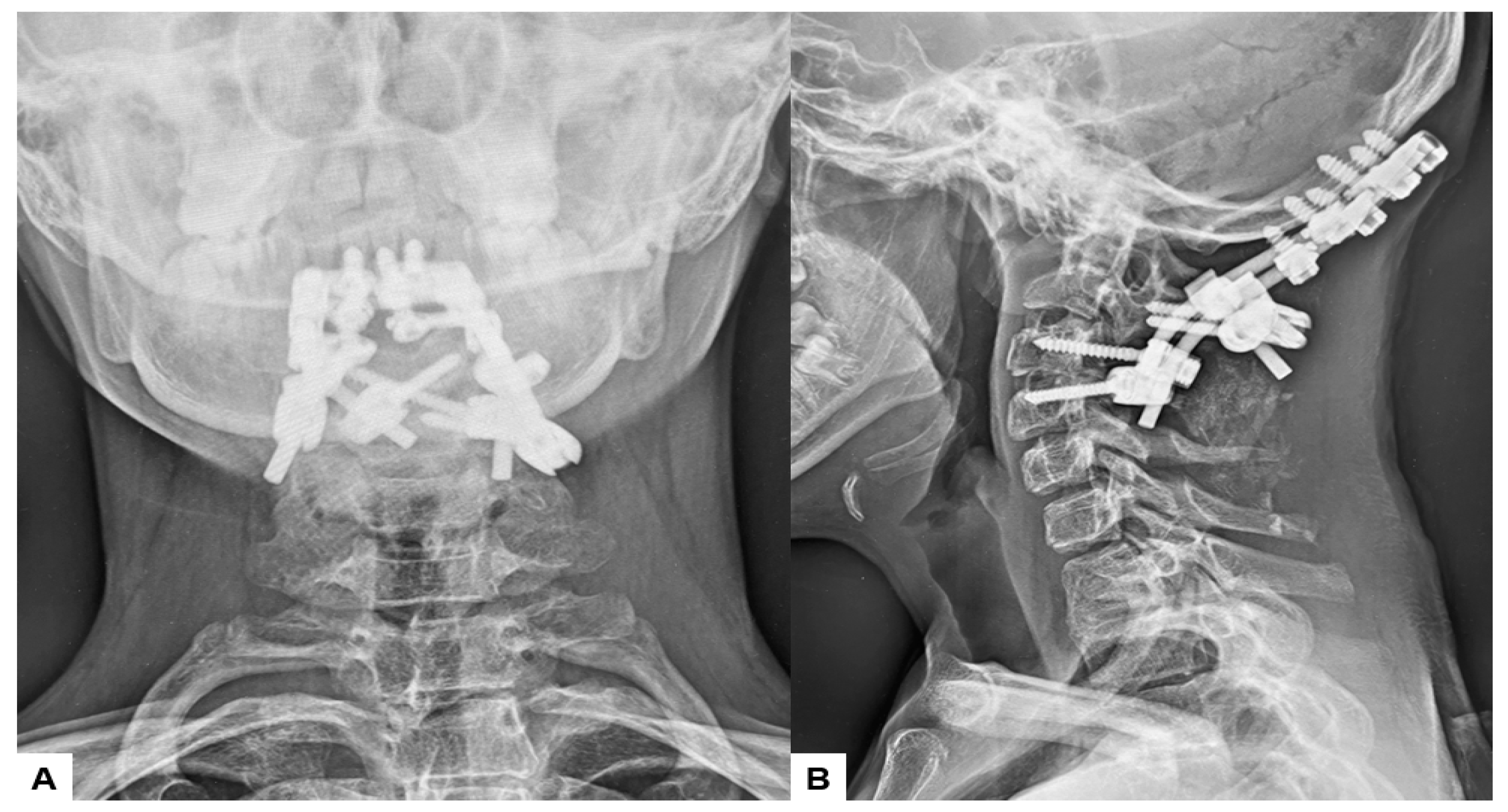

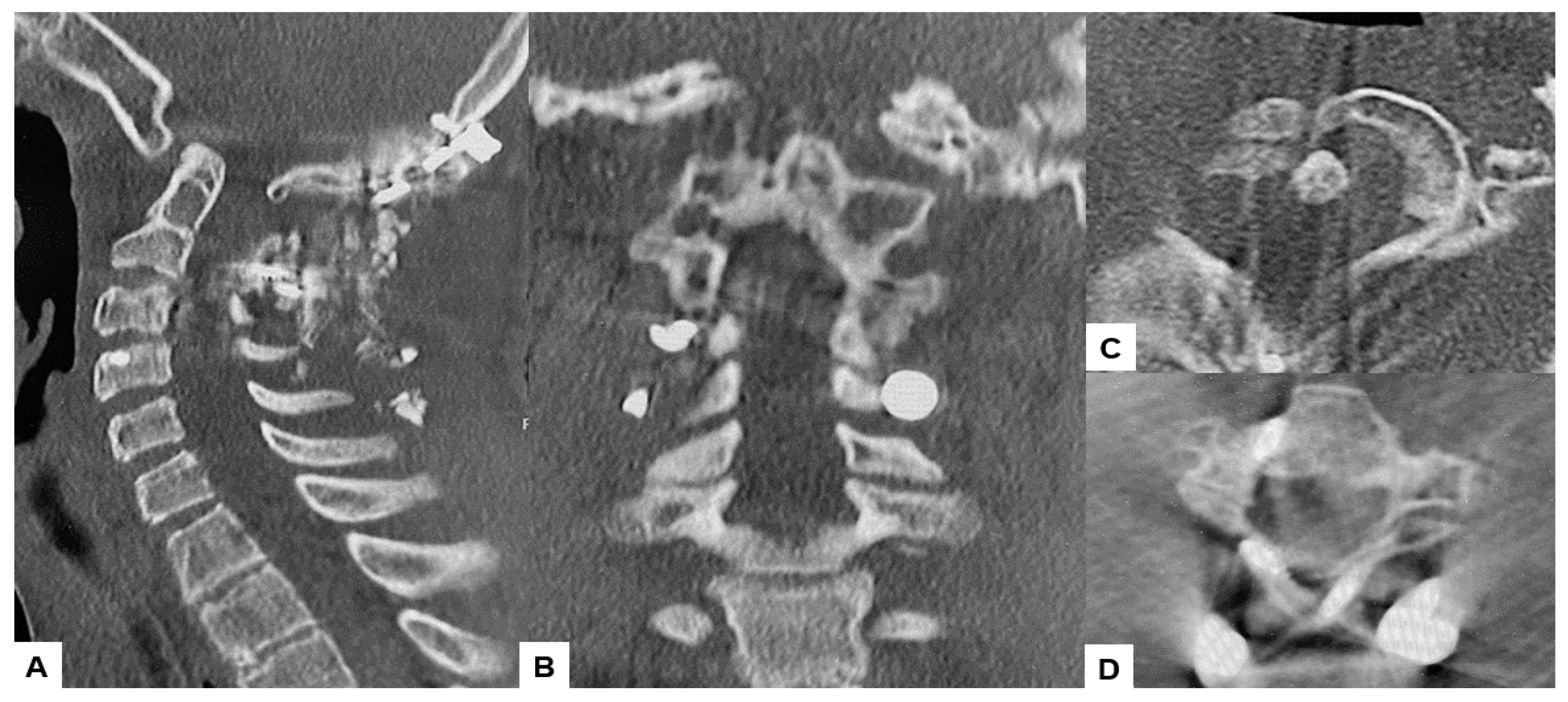

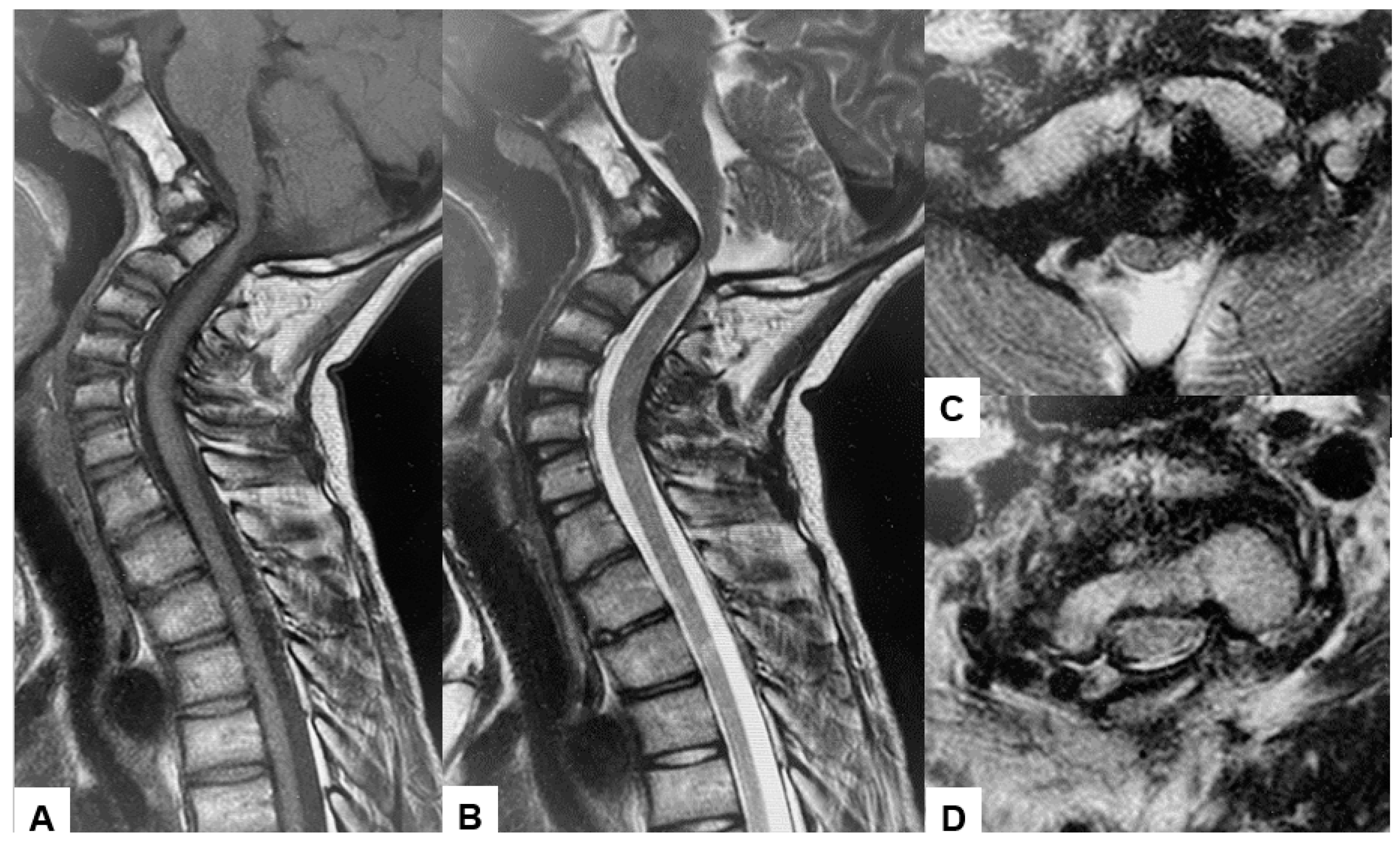

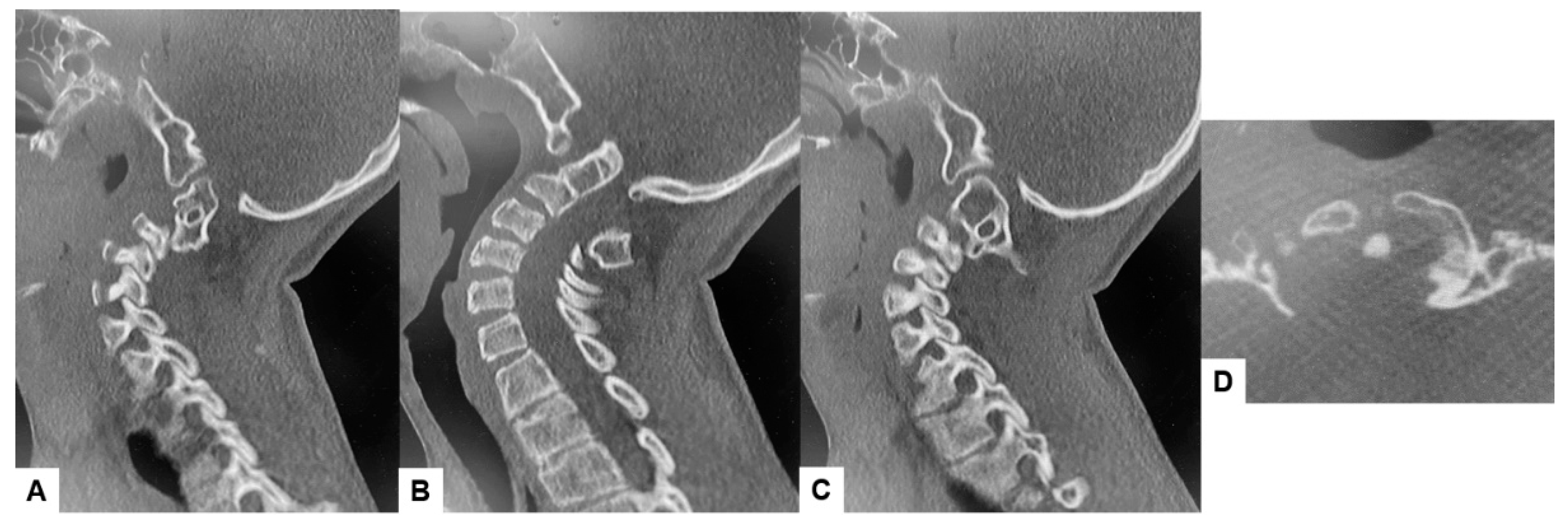

1.5. Postoperative imagings

1.6. One year follow-up

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da Silva, E.O. Autosomal recessive Klippel-Feil syndrome. J Med Genet. 1982, 19, 130–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippel, M.; Feil, A. Un cas d’absence des vertebres cervicales. Avec cage thoracique remontant jusqu’a la base du crane (cage thoracique cervicale). Nouv Iconog Salpetriere. 1912, 25, 223–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nagib, M.G.; Maxwell, R.E.; Chou, S.N. Identification and management of high-risk patients with Klippel-Feil syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1984, 61, 523–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, J.F. Ueber die Kretinen, einebesondereMenschenabart in den Alpen. Gotha, in der EttingerschenBuchhandlung. 1790. [Google Scholar]

- Joaquim AF, Ghizoni E, Giacomini LA, Tedeschi H, Patel AA. Basilar invagination: surgical results. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2014; 5, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Goel, A. Instability and basilar invagination. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2012, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüller, A. Zur Röntgendiagnose der basilären impression des schädels. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1911, 61, 2594–99. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, M. The significance of certain measurements of the skull in the diagnosis of basilar impression. Br J Radiol 1948, 21, 171e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, D.L.; Barnum, A.S. Occipitalization of the atlas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1953, 70, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, J.N.P.O.; Santos, B.A.D.; Nascimento, I.F.; Martins, L.A.; Tavares, C.B. Basilar invagination associated with chiari malformation type I: A literature review. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2019, 74, e653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, K.M.; Spivak, J.M.; Bendo, J.A. Embryology of the spine and associated congenital abnormalities. Spine J 2005, 5, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg MS (2010) Klippel–Feil syndrome. In: Greenberg MS (ed) Handbook of neurosurgery, 7th edn. Thieme Medical Publishers,New York, pp 253–254.

- Thomsen, M.N.; Schneider, U.; Weber, M.; Johannisson, R.; Niethard, FU. Scoliosis congenital anomalies associated with Klippel–Feil syndrome types, I. –.I.I.I. Spine 1997, 22, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, M.R.; Dormans, J.P.; Kusumi, K. Klippel-Feil syndrome: clinical features and current understanding of etiology. Clin Orthop Relat Res July 2004 (424):183–90. [CrossRef]

- Donnally, I.I.I.C.J.; Munakomi, S.; Varacallo, M. Basilar Invagination. [Updated 2023 Aug 13]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.A.; Botelho, R.V. The odontoid process invagination in normal subjects, Chiari malformation and Basilar invagination patients: pathophysiologic correlations with angular craniometry. Surg Neurol Int. 2015, 6, 118–7806160322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, D.L.; Barnum, A.S. Occipitalization of the atlas. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1953, 70, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chamnan, R.; Chantarasirirat, K.; Paholpak, P.; Wiley, K.; Buser, Z.; Wang, J.C. Occipitocervical measurements: correlation and consistency between multi-positional magnetic resonance imaging and dynamic radiographs. Eur Spine J. 2020, 29, 2795–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.P.; Zhang, R.J.; Zhang, H.Q.; Jiang, Z.F.; Shang, J.; Shen, C.L. Effect of High-Riding Vertebral Artery on the Accuracy and Safety of C2 Pedicle Screw Placement in Basilar Invagination and Related Risk Factors. Global Spine J. 2024, 14, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Jian, F. Computed tomographic angiography to analyze dangerous vertebral artery anomalies at the craniovertebral junction in patients with basilar invagination. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021, 200, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.P.; Zhang, R.J.; Jiang, Z.F.; Tao, E.X.; Shang, J.; Shen, C.L. Ideal entry point and trajectory for C2 pedicle screw placement in basilar invagination patients with high-riding vertebral artery based on 3D computed tomography. Spine J. 2022, 22, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joaquim, A.F.; Tedeschi, H.; Chandra, P.S. Controversies in the surgical management of congenital craniocervical junction disorders - A critical review. Neurol India. 2018, 66, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Al Jishi, A. Commentary: Comprehensive Drilling of C1-2 Facets in Congenital Atlanto-Axial Dislocation and Basilar Invagination: Critical Review. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019, 16, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim, A.F.; Tedeschi, H.; Chandra, P.S. Controversies in the surgical management of congenital craniocervical junction disorders - A critical review. Neurol India. 2018, 66, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A. Basilar invagination, Chiari malformation, syringomyelia: a review. Neurol India. 2009, 57, 235–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfin, S.R.; Botte, M.J.; Waters, R.L.; Nickel, V.L. Complications in the use of the halo fixation device. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1986, 68, 320–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumi K, Takada T. Shono Y, Kaneda K, Fujiya M. Posterior occipitocervical reconstruction using cervical pedicle screws and plate-rod systems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999 Jul 15:24(14):1425–34. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.H.; VanGilder, J.C.; Graf, C.J.; McDonnell, D.E. Craniocervical abnormalities. A comprehensive surgical approach. J Neurosurg. 1980, 53, 444–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A. Craniovertebral junction instability: a review of facts about facets. Asian Spine J. 2015, 9, 636–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zileli, M.; Akıntürk, N. Complications of occipitocervical fixation: retrospective review of 128 patients with 5-year mean follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2022, 31, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.K.; Pattankar, S.; Srivastava, A.K. Arterial Fencing: A Challenge During Complex Craniovertebral Junction Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain VK, Mittal P, Banerji D et al. Posterior occipitoaxial fusion for atrantoaxial dislocation associated with occipitalizedatlas. J Neurosurg 1996, 84, 559–564.

- Ishikawa Y, Kanemura T, Yoshida G, et al. Intraoperative, full-rotation, three-dimensional image (O-arm)-based navigation system for cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011, 15, 472–478.

- Wada K, Tamaki R, Yui M, et al. C1 lateral mass screw insertion caudally from C2 nerve root —an alternate method for insertion of C1 screws: a technical note and preliminary clinical results. J Orthop Sci. 2017, 22, 213–217. [CrossRef]

- El-Gaidi, M.A.; Eissa, E.M.; El-Shaarawy, E.A. Free hand placement of occipital condyle screws: a cadaveric study. Eur Spine J 2014, 23, 2182–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson MD, Lehman RA, Jr, Sasso RC, et al. Biomechanical analysis of occipitocervical stability afforded by three fixation techniques. Spine J 2011, 11, 245–50. [CrossRef]

- Takigawa T, Simon P, Espinoza Orias AA, et al. Biomechanical comparison of occiput-C1-C2 fixation techniques: C0-C1 transarticular screw and direct occiput condyle screw. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012, 37, E696–701. [CrossRef]

- Van de Kelft, E.; Costa, F.; Van der Planken, D.; Schils, F. A prospective multicenter registry on the accuracy of pedicle screw placement in the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral levels with the use of the O-arm imaging system and Stealth Station navigation. Spine. 2012, 37, E1580–E1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Spratt, K.F.; Spengler, D.; Brick, C.; Reid, S. Spinal pedicle fixation: reliability and validity of roentgenogram-based assessment and surgical factors on successful screw placement. Spine. 1988, 13, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Rizzolo, S.J.; Balderston, R.A. Placement of pedicle screws in the thoracic spine. Part II: an anatomical and radiographic assessment. J Bone Jt Surg. 1995, 77, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, B.D.; Baumhauer, J.F.; Morgan, T.L.; Rechtine, G.R. Cervical spine imaging using standard C-arm fluoroscopy: patient and surgeon exposure to ionizing radiation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008, 33, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco A, Venugopal P, Shetty AP, et al. Morphometric evaluation of occipital condyles: defining optimal trajectories and safe screw lengths for occipital condyle-based occipitocervical fixation in Indian population. Asian Spine J 2018, 12, 214–23. [CrossRef]

| Author | Safe permissible sagittal plane angulation (degrees) | Medial plane angulation (degrees) | Screw length† (mm) | Screw diameter (mm) |

| La Marca et al. | 30 caudal | 10 medial | 22 (intraosseous) | 3.5 |

| Uribe et al. | Zero to 5 cranial | 15 medial | 20 (intraosseous) | 3.5 |

| El-Gaidi et al. | 4±6.2 caudad angulation (range, from 5 cranially to 12 caudally) | 30±6.7 (range, 20–40) medial | 22±3.1 (intraosseous) | 3.5 |

| Bosco et al. | From 0 to 5 cranial | 23–38 medial | 19.9±2.3 (intraosseous) | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).