Submitted:

12 February 2024

Posted:

13 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

2. Different Water Management Practices for Rice Cultivation

2.1. Continuous Flooding (CF)

2.2. Alternate Wetting and Drying

2.3. Popular Methods around the Globe

| S. No | Technologies for Conserving Water in Rice Cultivation. | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

[70,71,72] |

|

[68] | |

|

[73] | |

| 2 |

|

[10,74] |

|

[36,75] | |

|

[76,77] | |

|

||

|

[73] | |

|

[78] | |

|

[73] | |

|

[79] | |

|

[73] | |

|

[1] |

2.4. Heavy Metal Pollution in Paddy Soil

2.5. Sources

2.5.1. Natural Ways of Cd Origination (Geogenic)

2.5.2. Anthropogenic Sources of Cd Input

2.6. Chinese Paddy Fields and Heavy Metal (HM)

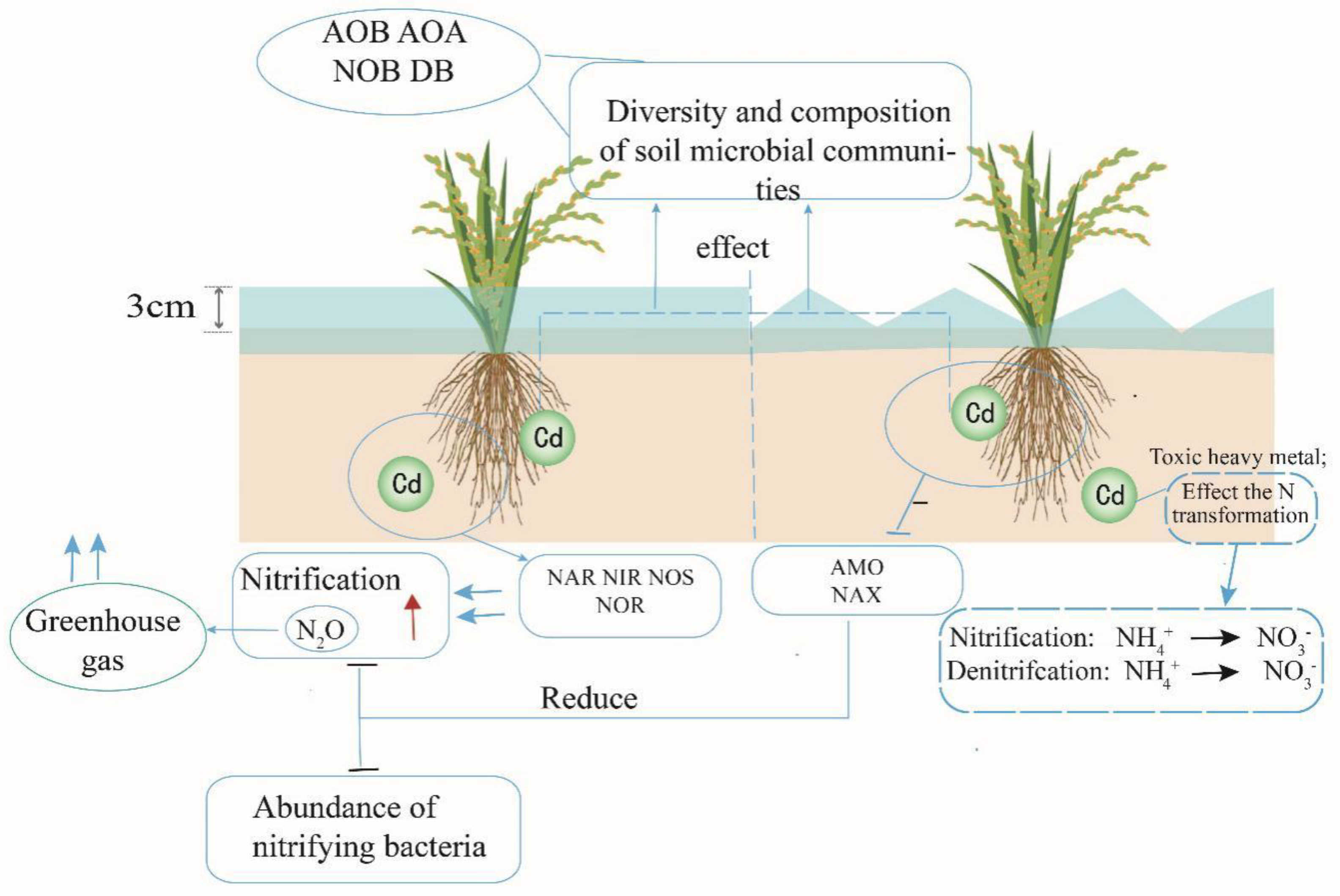

3. HM and Soil N Transformation

3.1. The Significance of Nitrification and Denitrification Processes in Paddy Soils

3.2. Nitrification

3.3. Denitrification

3.4. Production of N2O

3.5. Reduction of N2O

3.6. Effect of Cd on N Cycle in Paddy Soils

3.6.1. Nitrification

3.6.2. Denitrification

3.6.3. Greenhouse Gases from Paddy Fields under Metals Contamination

3.7. Different Forms of Cd and Its Mineralization under the Change in Redox Conditions of the Soil

4. Toxic Effects of Cd on Rice

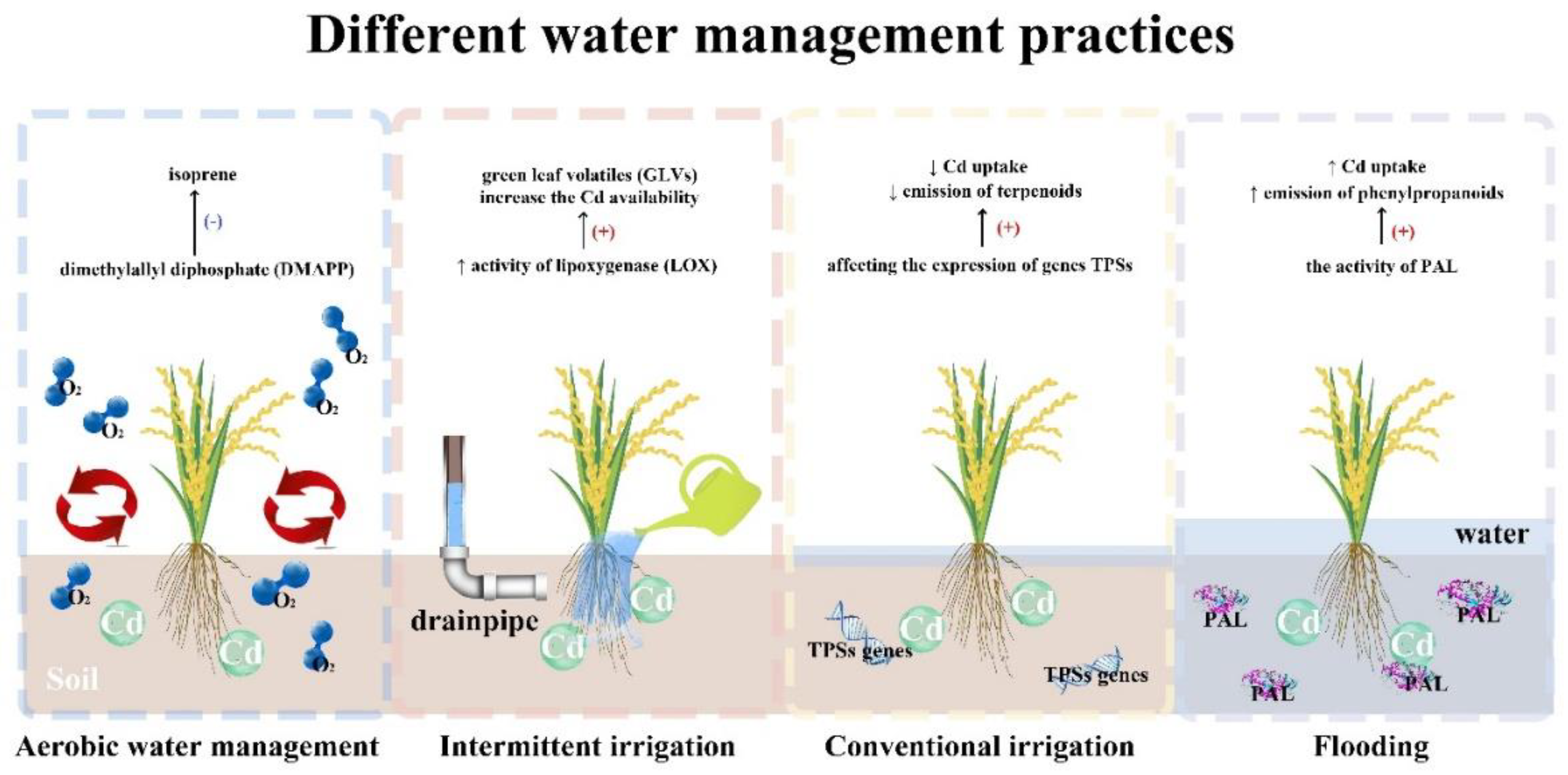

5. HM and VOCs in Paddy Soil under DWMP

5.1. Volatile Terpenoids

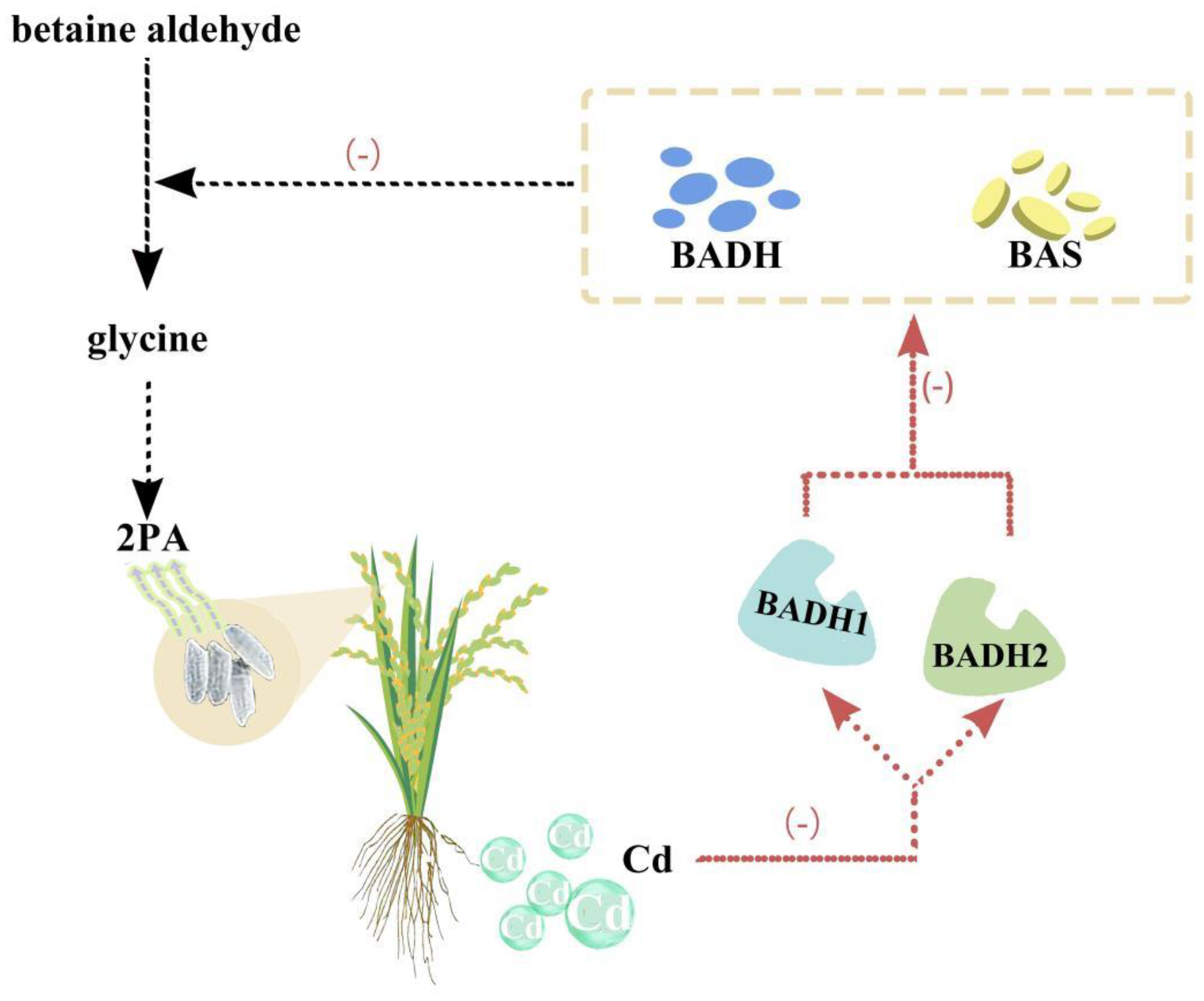

5.2. Effects of Heavy Metals on Rice Fragrance

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

References

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; McDaniel, M.D.; Sun, L.; Su, W.; Fan, X.; Liu, S.; Xiao, X. Water-saving irrigation is a ‘win-win’management strategy in rice paddies–With both reduced greenhouse gas emissions and enhanced water use efficiency. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 228, 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohidem, N.A.; Hashim, N.; Shamsudin, R.; Che Man, H. Rice for food security: Revisiting its production, diversity, rice milling process and nutrient content. Agriculture 2022, 12, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rahman, A.R.; Zhang, J. Trends in rice research: 2030 and beyond. Food and Energy Security 2023, 12, e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Improving nutritional quality of rice for human health. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2020, 133, 1397–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.H.; Wang, W.; Yin, C.M.; Hou, H.J.; Xie, K.J.; Xie, X.L. Water consumption, grain yield, and water productivity in response to field water management in double rice systems in China. PloS one 2017, 12, e0189280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouna, A.; Dzomeku, I.K.; Shaibu, A.-G.; Nurudeen, A.R. Water Management for Sustainable Irrigation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Production: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Cui, J.; Lu, B.; Brian, B.J.; Ding, J.; She, D. Impacts of controlled irrigation and drainage on the yield and physiological attributes of rice. Agricultural Water Management 2015, 149, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Ul-Allah, S.; Siddique, K.H. Physiological and agronomic approaches for improving water-use efficiency in crop plants. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 219, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Yu, M.; Tang, C.; Zhang, L.; Muhammad, N.; Zhao, H.; Feng, J.; Yu, L.; Xu, J. The negative impact of cadmium on nitrogen transformation processes in a paddy soil is greater under non-flooding than flooding conditions. Environment international 2019, 129, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Tang, C.; Yu, M.; Muhammad, N.; Zhao, H.; Xu, J. Water regime is important to determine cadmium toxicity on rice growth and rhizospheric nitrifier communities in contaminated paddy soils. Plant and Soil 2022, 472, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Lam, S.K.; Wolf, B.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Chen, D.; Li, Z.; Yan, X. Simultaneous quantification of N2, NH3 and N2O emissions from a flooded paddy field under different N fertilization regimes. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Ashida, N.; Kai, A.; Isobe, K.; Nishizawa, T.; Otsuka, S.; Yokota, A.; Senoo, K.; Ishii, S. Presence of Cu-Type (NirK) and cd1-Type (NirS) Nitrite Reductase Genes in the Denitrifying Bacterium Bradyrhizobium nitroreducens sp. nov. Microbes and environments 2018, 33, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Z.; Ma, J.; Xu, H.; Jia, Z. Differential contributions of ammonia oxidizers and nitrite oxidizers to nitrification in four paddy soils. The ISME journal 2015, 9, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Yao, P.; Liu, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, M.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.-H. Diversity, abundance, and niche differentiation of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in mud deposits of the eastern China marginal seas. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkovic, V.; Markovic, D.; Rensing, M. Plant volatiles as cues and signals in plant communication. Plant, cell & environment 2021, 44, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, S.E.; Schiestl, F.P. Rapid plant evolution driven by the interaction of pollination and herbivory. Science 2019, 364, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.-S.; Zhang, B.; Zhan, H.; Lv, Y.-L.; Jia, X.-L.; Wang, T.; Yang, N.-Y.; Lou, Y.-X.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Hu, W.-J. Phenylpropanoid derivatives are essential components of sporopollenin in vascular plants. Molecular plant 2020, 13, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusia, J.; Peñuelas, J. Bidirectional interaction between phyllospheric microbiotas and plant volatile emissions. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of terpenes and recent advances in plant protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosset, A.; Blande, J.D. Volatile-mediated plant–plant interactions: volatile organic compounds as modulators of receiver plant defence, growth, and reproduction. Journal of experimental botany 2022, 73, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Lo, L.S.H.; Liu, H.; Qian, P.-Y.; Cheng, J. Study of heavy metals and microbial communities in contaminated sediments along an urban estuary. Frontiers in Marine Science 2021, 8, 741912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Li, G.-X.; Sun, G.-X.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Meharg, A.A.; Zhu, Y.-G. The role of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes in the coupling of element biogeochemical cycling. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 613, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.M.; Tardy, V.; Bonnineau, C.; Billard, P.; Pesce, S.; Lyautey, E. Changes in sediment microbial diversity following chronic copper-exposure induce community copper-tolerance without increasing sensitivity to arsenic. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 391, 122197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.; Zhang, C.; Mathews, E.; Tang, C.; Franks, A. Microbial community dynamics in the rhizosphere of a cadmium hyper-accumulator. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 36067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Luan, Y.; Ning, Y.; Wang, L. Effects and mechanisms of microbial remediation of heavy metals in soil: a critical review. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehe, E.M.; Weigold, P.; Adaktylou, I.J.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Kraemer, U.; Kappler, A.; Behrens, S. Rhizosphere microbial community composition affects cadmium and zinc uptake by the metal-hyperaccumulating plant Arabidopsis halleri. Applied and environmental microbiology 2015, 81, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, G.; D’Egidio, S.; Sanangelantoni, A.M. The bacterial rhizobiome of hyperaccumulators: future perspectives based on omics analysis and advanced microscopy. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 5, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Ponce, B.; REZA-VÁZQUEZ, D.M.; Gutierrez-Paredes, S.; María de Jesús, D.; Maldonado-Hernandez, J.; Bahena-Osorio, Y.; Estrada-De los Santos, P.; WANG, E.T.; VÁSQUEZ-MURRIETA, M.S. Plant growth-promoting traits in rhizobacteria of heavy metal-resistant plants and their effects on Brassica nigra seed germination. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Peijnenburg, W.; Liu, W.; Lu, T.; Hu, B.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z.; Qian, H. Rhizosphere microbiome assembly and its impact on plant growth. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2020, 68, 5024–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oves, M.; Qari, H.A.; Khan, M.S. Sinorhizobium saheli: Advancing Chromium Mitigation, Metal Adsorption, and Plant Growth Enhancement in Heavy Metal-Contaminated Environments. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Dong, Y. Trifolium repens L. regulated phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soil by promoting soil enzyme activities and beneficial rhizosphere associated microorganisms. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 402, 123829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Meng, D.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Tao, J.; Gu, Y.; Zhong, S.; Yin, H. Comparative genomic analysis reveals the distribution, organization, and evolution of metal resistance genes in the genus Acidithiobacillus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2019, 85, e02153-02118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lei, X.; Qin, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, M.; Chen, S. Fe (III) reduction due to low pe+ pH contributes to reducing Cd transfer within a soil-rice system. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 415, 125668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, D.; Wang, R.; Gao, X.; Wang, K.; Lin, Z.; Ge, J.; Liu, T.; Wei, S.; Chen, W.; Xie, R. Cultivar-specific response of bacterial community to cadmium contamination in the rhizosphere of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environmental Pollution 2018, 241, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Science advances 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallareddy, M.; Thirumalaikumar, R.; Balasubramanian, P.; Naseeruddin, R.; Nithya, N.; Mariadoss, A.; Eazhilkrishna, N.; Choudhary, A.K.; Deiveegan, M.; Subramanian, E. Maximizing water use efficiency in rice farming: A comprehensive review of innovative irrigation management technologies. Water 2023, 15, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Ramesh, K.; Jinger, D.; Rajpoot, S.K. Effect of potassium fertilization on water productivity, irrigation water use efficiency, and grain quality under direct seeded rice-wheat cropping system. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2022, 45, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, U.; Raja, P.; Jayakumar, M.; Subramoniam, S.R. Use of efficient water saving techniques for production of rice in India under climate change scenario: A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 309, 127272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Lin, Y.-P.; Lur, H.-S. Evaluating and adapting climate change impacts on rice production in Indonesia: a case study of the Keduang subwatershed, Central Java. Environments 2021, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet-Loredo, A.; López-Belchí, M.D.; Cordero-Lara, K.; Noriega, F.; Cabeza, R.A.; Fischer, S.; Careaga, P.; Garriga, M. Assessing Grain Quality Changes in White and Black Rice under Water Deficit. Plants 2023, 12, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linquist, B.A.; Anders, M.M.; Adviento-Borbe, M.A.; Chaney, R.L.; Nalley, L.L.; da Rosa, E.F.; van Kessel, C. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and grain arsenic levels in rice systems. Glob Chang Biol 2015, 21, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray-Cabrera, I.; Cruz-Villacorta, L.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Bonilla-Cordova, M.; Heros-Aguilar, E.; Flores del Pino, L. Effect of Alternate Wetting and Drying on the Emission of Greenhouse Gases from Rice Fields on the Northern Coast of Peru. Agronomy 2024, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.-K.; Lim, E.M.; Kim, J.; Kang, M.-J.; Choi, G.; Moon, J. Risk Management of Methane Reduction Clean Development Mechanism Projects in Rice Paddy Fields. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Zhu, K.; Hua, X.; Harrison, M.T.; Liu, K.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y. Integrated management approaches enabling sustainable rice production under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 281, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chou, M.-L.; Jean, J.-S.; Liu, C.-C.; Yang, H.-J. Water management impacts on arsenic behavior and rhizosphere bacterial communities and activities in a rice agro-ecosystem. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 542, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, K.A.; Millar, G.M.; Norton, G.J.; Price, A.H. Alternate wetting and drying in Bangladesh: Water-saving farming practice and the socioeconomic barriers to its adoption. Food and Energy Security 2018, 7, e00149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaili, W.S.H. Adoption of technology to improve self-sufficiency in paddy plantations in Brunei: Challenges and mitigation strategies for intermediate stakeholders. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; 2023; p. 012011. [Google Scholar]

- Mote, K.; Rao, V.P.; Ramulu, V.; Kumar, K.A.; Devi, M.U.; Sudhakara, T. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation technology for sustainable rice (Oryza sativa) production. Paddy and Water Environment 2023, 21, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z. Managing irrigation water for sustainable rice production in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 245, 118928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haonan, Q.; Jie, W.; Shihong, Y.; Zewei, J.; Yi, X. Current status of global rice water use efficiency and water-saving irrigation technology recommendations. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Ledo, A.; Cheng, K.; Albanito, F.; Lebender, U.; Sapkota, T.B.; Brentrup, F.; Stirling, C.M.; Smith, P.; Sun, J. Re-assessing nitrous oxide emissions from croplands across Mainland China. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 268, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Zhai, L.; Zhou, F.; Ye, Y.; Ruan, S.; Wen, W. Effects and potential of water-saving irrigation for rice production in China. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 217, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Q.; Du, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, S. Water resource management for irrigated agriculture in China: Problems and prospects. Irrigation and Drainage 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Furman, A. Soil redox dynamics under dynamic hydrologic regimes-A review. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 763, 143026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Kong, Y.; Pan, W.; Wu, L.; Jin, Q. Alternate wetting–drying enhances soil nitrogen availability by altering organic nitrogen partitioning in rice-microbe system. Geoderma 2022, 424, 115993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, M.; Sanaullah, M.; Razavi, B.S.; Kuzyakov, Y. Effect of land use and management practices on microbial biomass and enzyme activities in subtropical top-and sub-soils. Applied Soil Ecology 2017, 113, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soremi, P.A. CHANGES IN MICROBIAL BIOMASS CARBON, NITROGEN AND GRAIN YIELD OF LOWLAND RICE VARIETIES IN RESPONSE TO ALTERNATE WET AND DRY WATER REGIME IN THE INLAND VALLEY OF DERIVED SAVANNA. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (Belgrade) 2019, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Pan, G. Effect of mid-season drainage on CH4 and N2O emission and grain yield in rice ecosystem: A meta-analysis. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 213, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Wu, X.; Yu, Y.; Luo, S.; Hu, R.; Lu, G. Effects of mild alternate wetting and drying irrigation and mid-season drainage on CH4 and N2O emissions in rice cultivation. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 698, 134212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, M.; Li, X.; Dai, Q.; Xu, K.; Guo, B.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Huo, Z. Effects of Soil Types and Irrigation Modes on Rice Root Morphophysiological Traits and Grain Quality. Agronomy 2021, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Cao, C. The different influences of drought stress at the flowering stage on rice physiological traits, grain yield, and quality. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, G.J.; Shafaei, M.; Travis, A.J.; Deacon, C.M.; Danku, J.; Pond, D.; Cochrane, N.; Lockhart, K.; Salt, D.; Zhang, H.; et al. Impact of alternate wetting and drying on rice physiology, grain production, and grain quality. Field Crops Research 2017, 205, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneepitak, S.; Ullah, H.; Paothong, K.; Kachenchart, B.; Datta, A.; Shrestha, R.P. Effect of water and rice straw management practices on yield and water productivity of irrigated lowland rice in the Central Plain of Thailand. Agricultural Water Management 2019, 211, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Akbar, N.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ali, N.; Ahmad, M.; Anjum, S.A.; Farooq, M. Influence of water management techniques on milling recovery, grain quality and mercury uptake in different rice production systems. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 243, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, R.; Moretto, G.; Barberis, M.; Frosi, I.; Papetti, A. Rice Byproduct Compounds: From Green Extraction to Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Carrijo, D.R.; Nakayama, Y.; Linquist, B.A.; Green, P.G.; Parikh, S.J. Impact of Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation on Arsenic Uptake and Speciation in Flooded Rice Systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2019, 272, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, B.; Bhupenchandra, I.; Devi, S.; Kumar, A.; Chongtham, S.; Singh, R.; Babu, S.; Bora, S.; Devi, E.; Verma, G. Aerobic Rice and its significant perspective for sustainable crop production. Indian Journal of Agronomy 2021, 66, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathi, T.; Vanitha, K.; Mohandass, S.; Vered, E. Evaluation of drip irrigation system for water productivity and yield of rice. Agronomy Journal 2018, 110, 2378–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Singh, O.; Berliner, J.; Pokhare, S. System of crop rotation: a prospective strategy alleviating grain yield penalty in sustainable aerobic rice production. International Journal of Plant Production 2021, 15, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoy-Pascual, K.; Lampayan, R.M.; Remocal, A.T.; Orge, R.F.; Tokida, T.; Mizoguchi, M. Optimizing the lateral dripline spacing of drip-irrigated aerobic rice to increase water productivity and profitability under the water-limited condition. Field Crops Research 2022, 287, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masseroni, D.; Ricart, S.; De Cartagena, F.R.; Monserrat, J.; Gonçalves, J.M.; De Lima, I.; Facchi, A.; Sali, G.; Gandolfi, C. Prospects for improving gravity-fed surface irrigation systems in Mediterranean European contexts. Water 2017, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Sharma, K. Rice Productivity and Water Use Efficiency under Different Irrigation Management System in North-Western India. Indian Journal of Extension Education 2022, 58, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, P.; Fernández-Rodríguez, D.; Abades, D.P.; Rato-Nunes, J.M.; Albarrán, Á.; López-Piñeiro, A. Combined use of olive mill waste compost and sprinkler irrigation to decrease the risk of As and Cd accumulation in rice grain. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 835, 155488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mubangizi, A.; Wanyama, J.; Kiggundu, N.; Nakawuka, P. Assessing Suitability of Irrigation Scheduling Decision Support Systems for Lowland Rice Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa—A Review. Agricultural Sciences 2023, 14, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.F.-u.; Sander, B.O.; Quilty, J.R.; de Neergaard, A.; van Groenigen, J.W.; Jensen, L.S. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and reduced irrigation water use in rice production through water-saving irrigation scheduling, reduced tillage and fertiliser application strategies. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 739, 140215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlangeni, A.T. Methylation of arsenic in rice: Mechanisms, factors, and mitigation strategies. Toxicology Reports 2023, 11, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Tang, S.; Pan, W.; Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Ni, L.; Mao, X.; Sun, T.; Fu, H.; Han, K. Long-term application of controlled-release fertilizer enhances rice production and soil quality under non-flooded plastic film mulching cultivation conditions. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2023, 358, 108720. [Google Scholar]

- Ghulamahdi, M.; Sulistyono, E.; Lubis, I.; Sastro, Y. Response of rice peat humic acid ameliorant. saturated,. soil. culture.(SSC) within tidal. swamps. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; 2023; p. 012009. [Google Scholar]

- Isnawan, B.; Hariyono, H.; Gumilar, A. Selection of Intermittent Irrigation to Increase Growth and Yield of Some Local Rice Varieties (Oryza sativa L.) in the Rainy Season. Jurnal Ilmiah Multidisiplin Indonesia (JIM-ID) 2023, 2, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mubeen, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Cadmium contamination in agricultural soils and crops. In Theories and Methods for Minimizing Cadmium Pollution in Crops: Case Studies on Water Spinach; Springer, 2022; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Dumat, C.; Khalid, S.; Niazi, N.K.; Antunes, P.M. Cadmium bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil-plant system. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2017, 241, 73–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mar, S.S.; Okazaki, M. Investigation of Cd contents in several phosphate rocks used for the production of fertilizer. Microchemical Journal 2012, 104, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridullah, F.; Umar, M.; Alam, A.; Sabir, M.A.; Khan, D. Assessment of heavy metals concentration in phosphate rock deposits, Hazara basin, Lesser Himalaya Pakistan. Geosciences Journal 2017, 21, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumaza, B.; Kechiched, R.; Chekushina, T.V.; Benabdeslam, N.; Senouci, K.; Merzeg, F.A.; Rezgui, W.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Harizi, K. Geochemical distribution and environmental assessment of potentially toxic elements in farmland soils, sediments, and tailings from phosphate industrial area (NE Algeria). Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 465, 133110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canty, M.J.; Scanlon, A.; Collins, D.M.; McGrath, G.; Clegg, T.A.; Lane, E.; Sheridan, M.K.; More, S.J. Cadmium and other heavy metal concentrations in bovine kidneys in the Republic of Ireland. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 485-486, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti, V.; Saini-Eidukat, B.; Hopkins, D.; DeSutter, T. Naturally elevated metal contents of soils in northeastern North Dakota, USA, with a focus on cadmium. J Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, T.C.; Braungardt, C.B.; Rieuwerts, J.; Worsfold, P. Cadmium contamination of agricultural soils and crops resulting from sphalerite weathering. Environmental Pollution 2014, 184, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimann, C.; Fabian, K.; Flem, B. Cadmium enrichment in topsoil: Separating diffuse contamination from biosphere-circulation signals. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 651, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imseng, M.; Wiggenhauser, M.; Keller, A.; Müller, M.; Rehkämper, M.; Murphy, K.; Kreissig, K.; Frossard, E.; Wilcke, W.; Bigalke, M. Fate of Cd in Agricultural Soils: A Stable Isotope Approach to Anthropogenic Impact, Soil Formation, and Soil-Plant Cycling. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birke, M.; Reimann, C.; Rauch, U.; Ladenberger, A.; Demetriades, A.; Jähne-Klingberg, F.; Oorts, K.; Gosar, M.; Dinelli, E.; Halamić, J. GEMAS: Cadmium distribution and its sources in agricultural and grazing land soil of Europe — Original data versus clr-transformed data. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2017, 173, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, S.M.; Pena, L.B.; Barcia, R.A.; Azpilicueta, C.E.; Iannone, M.F.; Rosales, E.P.; Zawoznik, M.S.; Groppa, M.D.; Benavides, M.P. Unravelling cadmium toxicity and tolerance in plants: Insight into regulatory mechanisms. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2012, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, F.; Guo, S.; Zhao, M. Cadmium concentration and its typical input and output fluxes in agricultural soil downstream of a heavy metal sewage irrigation area. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 412, 125203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, S.; Sher, F.; Chen, J.; Xin, Y.; You, Z.; Wen, L.; Hu, M.; Qiu, G. A review on recycling and reutilization of blast furnace dust as a secondary resource. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 2021, 7, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Ai, F.; Jin, L.; Zhu, N.; Meng, X.-Z. Identification of industrial sewage sludge based on heavy metal profiles: a case study of printing and dyeing industry. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Xu, B.; Zhu, L.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. Source identification and potential ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in PM2.5 from Changsha. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 493, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.I.; Haider, R.; Ahmad, K.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Mehmood, N.; Memona, H.; Akhtar, S.; Ugulu, I. The Effects of Irrigation with Diverse Wastewater Sources on Heavy Metal Accumulation in Kinnow and Grapefruit Samples and Health Risks from Consumption. Water 2023, 15, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, M.; Lin, L.; Scholz, M. Review of remediation practices regarding cadmium-enriched farmland soil with particular reference to China. Journal of environmental management 2016, 181, 646–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.-H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S.-H.; Pan, S.-F.; Ji, X.-H. Input and output of cadmium (Cd) for paddy soil in central south China: fluxes, mass balance, and model predictions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 21847–21858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, F.; Cai, T.; Zhao, W.; Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Bian, J.; Fu, J.; Ouyang, L. The Relationship between Cadmium-Related Gene Sequence Variations in Rice and Cadmium Accumulation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; de Klein, C.A.M.; Ledgard, S.F.; Saggar, S. Management options to reduce nitrous oxide emissions from intensively grazed pastures: A review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2010, 136, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, G.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, C.; Kong, L. Cadmium (Cd) distribution and contamination in Chinese paddy soils on national scale. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 17941–17952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.-Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J.; Li, F.; Deng, D.-M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C. Cadmium availability in rice paddy fields from a mining area: The effects of soil properties highlighting iron fractions and pH value. Environmental Pollution 2016, 209, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.N.; Lei, M.; Sun, G.; Huang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Deacon, C.; Meharg, A.A.; Zhu, Y.G. Occurrence and partitioning of cadmium, arsenic and lead in mine impacted paddy rice: Hunan, China. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Li, L.Q.; Pan, G.X. [Variation of Cd, Zn and Se contents of polished rice and the potential health risk for subsistence-diet farmers from typical areas of South China]. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2009, 30, 2792–2797. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Luo, L.; Zhang, C.; Pélissier, P.M.; Parizot, B.; Qi, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. Rice plants respond to ammonium stress by adopting a helical root growth pattern. Plant J 2020, 104, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Qin, W.; Ashraf, U. Deep fertilization improves rice productivity and reduces ammonia emissions from rice fields in China; a meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2022, 289, 108704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, R.; Hu, S.; Qiao, Z.; Wang, S.; Mi, X. NH4+-N/NO3−-N ratio controlling nitrogen transformation accompanied with NO2−-N accumulation in the oxic-anoxic transition zone. Environmental Research 2020, 189, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Song, B.; Phillips, R.L.; Chang, J.; Song, M.J. Ecological and physiological implications of nitrogen oxide reduction pathways on greenhouse gas emissions in agroecosystems. FEMS microbiology ecology 2019, 95, fiz066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Shao, D.; Gu, W. Effects of temperature and soil moisture on gross nitrification and denitrification rates of a Chinese lowland paddy field soil. Paddy and Water Environment 2018, 16, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Sheng, R.; Wei, W.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, W. Differential contributions of electron donors to denitrification in the flooding-drying process of a paddy soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2022, 177, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Hua, Z.; Xue, H.; Mei, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, S. Comparison of nitrogen loss weight in ammonia volatilization, runoff, and leaching between common and slow-release fertilizer in paddy field. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2021, 232, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Mo, L.-Y.; Fang, Y.-T.; Di, H.J.; Wang, J.-T.; Shen, J.-P.; Zhang, L.-M. Rates and microbial communities of denitrification and anammox across coastal tidal flat lands and inland paddy soils in East China. Applied Soil Ecology 2021, 157, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Niu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, X.G. Waterlogging increases organic carbon decomposition in grassland soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2020, 148, 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-G.; Xue, L.-H.; Li, H.-B.; Yang, L.-Z. Roles of bulk and rhizosphere denitrifying bacteria in denitrification from paddy soils under straw return condition. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2021, 21, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.-J.; Cui, H.-L.; Nie, S.-A.; Long, X.-E.; Duan, G.-L.; Zhu, Y.-G. Microbiomes inhabiting rice roots and rhizosphere. FEMS microbiology ecology 2019, 95, fiz040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyan, S.K.; Bhatia, A.; Tomer, R.; Harit, R.C.; Jain, N.; Bhowmik, A.; Kaushik, R. Mitigation of yield-scaled greenhouse gas emissions from irrigated rice through Azolla, Blue-green algae, and plant growth–promoting bacteria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 51425–51439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B. A three-year experiment of annual methane and nitrous oxide emissions from the subtropical permanently flooded rice paddy fields of China: Emission factor, temperature sensitivity and fertilizer nitrogen effect. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2018, 250, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidthaisong, A.; Cha-un, N.; Rossopa, B.; Buddaboon, C.; Kunuthai, C.; Sriphirom, P.; Towprayoon, S.; Tokida, T.; Padre, A.T.; Minamikawa, K. Evaluating the effects of alternate wetting and drying (AWD) on methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a paddy field in Thailand. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2018, 64, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranatunga, T.; Hiramatsu, K.; Onishi, T.; Ishiguro, Y. Process of denitrification in flooded rice soils. Reviews in Agricultural Science 2018, 6, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A.; Borges, A.V.; Brouyère, S. Dynamics and emissions of N2O in groundwater: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 584, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Lindsey, S. Effects of biochar and 3, 4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP) on soil ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and nos ZN 2 O reducers in the mitigation of N 2 O emissions from paddy soils. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2021, 21, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Tian, R.; Vancov, T.; Ma, F.; Fang, Y.; Liang, X. Response of N2O emission and denitrifying genes to iron (II) supplement in root zone and bulk region during wetting-drying alternation in paddy soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2024, 194, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martikainen, P.J. Heterotrophic nitrification–An eternal mystery in the nitrogen cycle. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2022, 168, 108611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, P.; Laanbroek, H.J.; Nicol, G.W.; Renella, G.; Cardinale, M.; Pietramellara, G.; Weckwerth, W.; Trinchera, A.; Ghatak, A.; Nannipieri, P. Biological nitrification inhibition in the rhizosphere: determining interactions and impact on microbially mediated processes and potential applications. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2020, 44, 874–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.-Y.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Kits, K.D.; Mueller, A.J.; Rhee, S.-K.; Hink, L.; Nicol, G.W.; Bayer, B.; Lehtovirta-Morley, L.; Wright, C. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea possess a wide range of cellular ammonia affinities. The ISME journal 2022, 16, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, H.; Lin, Y.-P.; Anthony, J. Ammonia oxidizing archaea and bacteria in east Asian paddy soils—A mini review. Environments 2017, 4, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kan, J.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qian, G.; Miao, Y.; Leng, X.; Sun, J. Archaea dominate the ammonia-oxidizing community in deep-sea sediments of the Eastern Indian Ocean—from the equator to the Bay of Bengal. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, H.-F.; Kang, Y.-C.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Y.-R.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Y.; Li, P.; Yang, F. Comammox plays a functionally important role in the nitrification of rice paddy soil with different nitrogen fertilization levels. Applied Soil Ecology 2024, 193, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xiao, X.; Li, C.; Cheng, K.; Pan, X.; Li, W. Effects of rhizosphere and long-term fertilisation practices on the activity and community structure of ammonia oxidisers under double-cropping rice field. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science 2019, 69, 356–368. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ni, L.; Song, Y.; Rhodes, G.; Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q. Dynamic response of ammonia-oxidizers to four fertilization regimes across a wheat-rice rotation system. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Ye, J.; Perez, P.G.; Huang, D.-F. Abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in rhizosphere and bulk paddy soil under different duration of organic management. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2011, 5, 5560–5568. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; He, M.; Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Dan, X.; He, X.; Meng, L.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Z. Rice genotype affects nitrification inhibition in the rhizosphere. Plant and Soil 2022, 481, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, H.; Dumont, M.G.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J. Nitrosospira cluster 3-like bacterial ammonia oxidizers and Nitrospira-like nitrite oxidizers dominate nitrification activity in acidic terrace paddy soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2019, 131, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wright, A.L.; Shi, X.; Jiang, X. Different ammonia oxidizers are responsible for nitrification in two neutral paddy soils. Soil and Tillage Research 2019, 195, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, K.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Liao, Y.; Xu, J.; Di, H. Ammonia oxidizers and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria respond differently to long-term manure application in four paddy soils of south of China. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 633, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ding, W.; Liu, D.; He, T.; Yoo, G.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Z.; Fan, J. Wheat straw-derived biochar amendment stimulated N2O emissions from rice paddy soils by regulating the amoA genes of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2017, 113, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Long, X.-E.; Tang, Y.-f.; Wen, J.; Su, S.; Bai, L.; Liu, R.; Zeng, X. Effects of different fertilizer application methods on the community of nitrifiers and denitrifiers in a paddy soil. Journal of soils and sediments 2018, 18, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.; Zheng, M. Nitrite oxidation in wastewater treatment: microbial adaptation and suppression challenges. Environmental Science & Technology 2023, 57, 12557–12570. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.M.; Parthasarathy, A.K.; Matkar, A.R.; Mahamuni-Badiger, P.; Hwang, S.; Gurav, R.; Dhanavade, M.J. Nitrite-oxidizing Bacteria: Cultivation, Growth Physiology, and Chemotaxonomy. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J.; Sanford, R.A.; Chee-Sanford, J.; Ooi, S.K.; Löffler, F.E.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Yang, W.H. Beyond denitrification: the role of microbial diversity in controlling nitrous oxide reduction and soil nitrous oxide emissions. Global change biology 2021, 27, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, Z. Response of bacteria harboring nirS and nirK genes to different N fertilization rates in an alkaline northern Chinese soil. European Journal of Soil Biology 2017, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gao, X.; Xia, T.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Wang, D.; Xu, S. Community Structure and Diversity of nirS-type Denitrifying Bacteria in Paddy Soils. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J.; Yang, P.; Shang, X.; Rahman, M.M.; Yan, X. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation and denitrification in a paddy soil as affected by temperature, pH, organic carbon, and substrates. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2018, 54, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Shao, D.; Gu, W. Effects of temperature and soil moisture on gross nitrification and denitrification rates of a Chinese lowland paddy field soil. Paddy and Water Environment 2018, 16, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, I.S.; Medhi, K. Nitrification and denitrification processes for mitigation of nitrous oxide from waste water treatment plants for biovalorization: Challenges and opportunities. Bioresource technology 2019, 282, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.I.; Hink, L.; Gubry-Rangin, C.; Nicol, G.W. Nitrous oxide production by ammonia oxidizers: physiological diversity, niche differentiation and potential mitigation strategies. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Xie, D.; Ni, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Z. Nitrous oxide produced directly from ammonium, nitrate and nitrite during nitrification and denitrification. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 388, 122114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; De Vos, P.; Willems, A. Influence of nitrate and nitrite concentration on N2O production via dissimilatory nitrate/nitrite reduction to ammonium in Bacillus paralicheniformis LMG 6934. MicrobiologyOpen 2018, 7, e00592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roco, C.A.; Bergaust, L.L.; Bakken, L.R.; Yavitt, J.B.; Shapleigh, J.P. Modularity of nitrogen-oxide reducing soil bacteria: linking phenotype to genotype. Environmental Microbiology 2017, 19, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, J.M.; Blackwell, N.; Ruser, R.; Kappler, A.; Kleindienst, S.; Schmidt, C. N2O formation by nitrite-induced (chemo) denitrification in coastal marine sediment. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conthe, M.; Wittorf, L.; Kuenen, J.G.; Kleerebezem, R.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.; Hallin, S. Life on N2O: deciphering the ecophysiology of N2O respiring bacterial communities in a continuous culture. The ISME journal 2018, 12, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-y.; LU, S.-e.; XIANG, Q.-j.; YU, X.-m.; Ke, Z.; ZHANG, X.-p.; TU, S.-h.; GU, Y.-f. Responses of N2O reductase gene (nosZ)-denitrifier communities to long-term fertilization follow a depth pattern in calcareous purplish paddy soil. Journal of integrative agriculture 2017, 16, 2597–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Suter, H.; He, J.-Z.; Hu, H.-W.; Chen, D. Nitrogen addition decreases dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in rice paddies. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2018, 84, e00870–00818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Qin, S.; Pang, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhao, X.; Clough, T.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Zhou, S. Rice root Fe plaque enhances paddy soil N2O emissions via Fe (II) oxidation-coupled denitrification. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2019, 139, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Hong, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, F.; Ye, J.; Lu, J.; Long, A. Denitrification contributes to N2O emission in paddy soils. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1218207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Uzair, M.; Maqbool, Z.; Fiaz, S.; Yousuf, M.; Yang, S.H.; Khan, M.R. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in aerobic rice based on insights into the ecophysiology of archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidizers. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 913204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q. Effects of combined biochar and organic fertilizer on nitrous oxide fluxes and the related nitrifier and denitrifier communities in a saline-alkali soil. Science of the total environment 2019, 686, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TENORIO, J.I.R. WHEAT CULTIVAR INFLUENCE OVER NITROGEN-FIXING BACTERIAL COMMUNITIES IN AN ANDISOL AND A NOVEL PGPB TRACKING METHOD FOR AZOSPIRILLUM SPP. BASED ON CRISPR LOCI-TARGETED PCR. UNIVERSIDAD DE LA FRONTERA, 2020.

- Masocha, B.L.; Dikinya, O.; Moseki, B. Bioavailability and contamination levels of Zn, Pb, and Cd in sandy-loam soils, Botswana. Environmental Earth Sciences 2022, 81, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska-Malina, J. Functions of organic matter in polluted soils: The effect of organic amendments on phytoavailability of heavy metals. Applied Soil Ecology 2018, 123, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrasek, G.; Begić, H.B.; Zovko, M.; Filipović, L.; Meriño-Gergichevich, C.; Savić, R.; Rengel, Z. Biogeochemistry of soil organic matter in agroecosystems & environmental implications. Science of the total environment 2019, 658, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Shamshad, S.; Rafiq, M.; Khalid, S.; Bibi, I.; Niazi, N.K.; Dumat, C.; Rashid, M.I. Chromium speciation, bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil-plant system: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podar, D.; Maathuis, F.J. The role of roots and rhizosphere in providing tolerance to toxic metals and metalloids. Plant, cell & environment 2022, 45, 719–736. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Rhizosphere size and shape: Temporal dynamics and spatial stationarity. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2019, 135, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Vibhandik, R.; Agrahari, R.; Daverey, A.; Rani, R. Role of Root Exudates on the Soil Microbial Diversity and Biogeochemistry of Heavy Metals. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Garg, N. Microbial community in soil-plant systems: Role in heavy metal (loid) detoxification and sustainable agriculture. In Rhizosphere Engineering; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 471–498. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Kjellerup, B.V. Biogeochemical cycling of metals impacting by microbial mobilization and immobilization. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2018, 66, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Hao, R.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J. A review on mechanism of biomineralization using microbial-induced precipitation for immobilizing lead ions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 30486–30498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, L.; Teng, K.; Ma, J.; Xiang, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, G.; Yang, B.; Fang, J. Potential roles of the rhizospheric bacterial community in assisting Miscanthus floridulus in remediating multi-metal (loid) s contaminated soils. Environmental Research 2023, 227, 115749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palacios, P.; Crowther, T.W.; Dacal, M.; Hartley, I.P.; Reinsch, S.; Rinnan, R.; Rousk, J.; van den Hoogen, J.; Ye, J.-S.; Bradford, M.A. Evidence for large microbial-mediated losses of soil carbon under anthropogenic warming. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2021, 2, 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Bai, J.; Zhai, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Hu, X. Microbial diversity and functions in saline soils: A review from a biogeochemical perspective. Journal of Advanced Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, N.; Abdullahi, A.A.; Abdulkadir, A. Heavy metals and soil microbes. Environmental chemistry letters 2017, 15, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, X.; Zhong, X.; Lv, J. Contribution of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria to nitrogen transformation in a soil fertilized with urea and organic amendments. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 20722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fait, G.; Broos, K.; Zrna, S.; Lombi, E.; Hamon, R. Tolerance of nitrifying bacteria to copper and nickel. Environ Toxicol Chem 2006, 25, 2000–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, T.; Pan, G.; Crowley, D.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Abundance, Composition and Activity of Ammonia Oxidizer and Denitrifier Communities in Metal Polluted Rice Paddies from South China. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; Yu, S.; Li, F. Variations of abundance and community structure of ammonia oxidizers and nitrification activity in two paddy soils polluted by heavy metals. Geomicrobiology Journal 2019, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Meng, D.; Li, J.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yan, M. Response of soil microbial communities and microbial interactions to long-term heavy metal contamination. Environmental Pollution 2017, 231, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Chen, C.; Ke, T.; Wang, M.; Sima, M.; Huang, S. Long-term metal pollution shifts microbial functional profiles of nitrification and denitrification in agricultural soils. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 830, 154732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G. Abundance and structure composition of nirK and nosZ genes as well as denitrifying activity in heavy metal-polluted paddy soils. Geomicrobiology Journal 2018, 35, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Pan, G. Abundance, composition and activity of denitrifier communities in metal polluted paddy soils. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 19086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruyters, S.; Mertens, J.; T’Seyen, I.; Springael, D.; Smolders, E. Dynamics of the nitrous oxide reducing community during adaptation to Zn stress in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2010, 42, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Rao, Y.; Huang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, K.; Liang, X.; Ling, Q.; Liu, K.; Ma, J.; Yu, F. Impact of environmental factors on the ammonia-oxidizing and denitrifying microbial community and functional genes along soil profiles from different ecologically degraded areas in the Siding mine. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 326, 116641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, R.; Ye, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Q.; Tu, R.; Zhang, L.; Gao, H. Greenhouse gas emissions from synthetic nitrogen manufacture and fertilization for main upland crops in China. Carbon balance and management 2019, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahrl, F.; Li, Y.; Su, Y.; Tennigkeit, T.; Wilkes, A.; Xu, J. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use in China. Environmental Science & Policy 2010, 13, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P.; Groffman, P.M. Chapter 14 - Nitrogen transformations. In Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry (Fifth Edition); Paul, E.A., Frey, S.D., Eds.; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 407–438. [Google Scholar]

- Kuypers, M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIE, Z.-j.; QIN, S.-y.; LIU, H.-e.; ZHAO, P.; WU, X.-t.; GAO, W.; LI, C.; ZHANG, W.-w.; SUI, F.-q. Effects of combined application of nitrogen and zinc on winter wheat yield and soil enzyme activities related to nitrogen transformation. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizers 2020, 26, 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Han, J.; Shi, L. Effects of drying-rewetting cycles on ferrous iron-involved denitrification in paddy soils. Water 2021, 13, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.W.; Kim, P.J.; Khan, M.I.; Lee, S.-J. Effect of rice planting on nitrous oxide (N2O) emission under different levels of nitrogen fertilization. Agronomy 2021, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhu, G. Contribution of Ammonium-Induced Nitrifier Denitrification to N2O in Paddy Fields. Environmental Science & Technology 2023, 57, 2970–2980. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y. Quantifying direct N2O emissions in paddy fields during rice growing season in mainland China: Dependence on water regime. Atmospheric Environment 2007, 41, 8030–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B.; Yan, P.; Zhou, G.; Xin, X. Effects of straw amendment and moisture on microbial communities in Chinese fluvo-aquic soil. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2014, 14, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Yuan, X.; Xiong, T.; Tan, Y.Z.; Wang, H. Physicochemical properties, metal availability and bacterial community structure in heavy metal-polluted soil remediated by montmorillonite-based amendments. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 128010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, P.; Bellitürk, K.; Görres, J.H. Phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil by switchgrass: A comparative study utilizing different composts and coir fiber on pollution remediation, plant productivity, and nutrient leaching. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Hesham Ael, L.; Qiao, M.; Rehman, S.; He, J.Z. Effects of Cd and Pb on soil microbial community structure and activities. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2010, 17, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cao, W.; Jiang, H.; Cui, J.; Shi, C.; Qiao, X.; Zhao, J.; Si, W. Impact of heavy metal pollution on ammonia oxidizers in soils in the vicinity of a Tailings Dam, Baotou, China. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology 2018, 101, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.O.; Balgobind, A.; Pillay, B. Bioavailability of heavy metals in soil: impact on microbial biodegradation of organic compounds and possible improvement strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 10197–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Si, S.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, P.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X. Synergistic passivation performance of cadmium pollution by biochar combined with sulfate reducing bacteria. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 32, 103356. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yan, M.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, H. Effects of redox potential on soil cadmium solubility: insight into microbial community. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2019, 75, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Flandes, S.; González, B.; Ulloa, O. Redox traits characterize the organization of global microbial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 3630–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Hua, M.; Li, W.; Wen, Y.; Li, T.; He, X. Assessing the fractionation and bioavailability of heavy metals in soil–rice system and the associated health risk. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, L.; Luo, Y.; Christie, P. Effects of organic matter fraction and compositional changes on distribution of cadmium and zinc in long-term polluted paddy soils. Environmental Pollution 2018, 232, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Ashraf, M.N.; Abbas, A.; Li, J.; Farooq, M. Cadmium stress in paddy fields: effects of soil conditions and remediation strategies. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 754, 142188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukowski, A.; Dec, D. Influence of Zn, Cd, and Cu fractions on enzymatic activity of arable soils. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2018, 190, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J.; Zhou, Y.-F. Chapter Five - Retention of heavy metals by dredged sediments and their management following land application. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press, 2022; Volume 171, pp. 191–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, E.; Šutriepka, M. Effect of drying on the sorption and desorption of copper in bottom sediments from water reservoirs and geochemical partitioning of heavy metals and arsenic. J Hydrol Hydromech 2008, 55, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, G.F.; Groenenberg, J.E. Effects of soil oven-drying on concentrations and speciation of trace metals and dissolved organic matter in soil solution extracts of sandy soils. Geoderma 2011, 161, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu JunZeng, X.J.; Lv YuPing, L.Y.; Yang ShiHong, Y.S.; Wei Qi, W.Q.; Qiao ZhenFang, Q.Z. Water saving irrigation improves the solubility and bioavailability of zinc in rice paddy. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Xu, Y. Effects of clay combined with moisture management on Cd immobilization and fertility index of polluted rice field. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 158, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Qiao, Z.; Yang, S.; Gao, X. Binding forms and availability of Cd and Cr in paddy soil under non-flooding controlled irrigation. Paddy and water environment 2014, 12, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohne, T.; Rinklebe, J.; Diaz-Bone, R.A.; Du Laing, G. Controlled variation of redox conditions in a floodplain soil: Impact on metal mobilization and biomethylation of arsenic and antimony. Geoderma 2011, 160, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arao, T.; Kawasaki, A.; Baba, K.; Mori, S.; Matsumoto, S. Effects of water management on cadmium and arsenic accumulation and dimethylarsinic acid concentrations in Japanese rice. Environmental Science & Technology 2009, 43, 9361–9367. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Bae, D.W.; Kim, S.H.; Han, H.J.; Liu, X.; Park, H.C.; Lim, C.O.; Lee, S.Y.; Chung, W.S. Comparative proteomic analysis of the short-term responses of rice roots and leaves to cadmium. Journal of Plant Physiology 2010, 167, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, M.; Zou, X.; Yin, C.; Lin, Y. Research advances in cadmium uptake, transport and resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Cells 2022, 11, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterckeman, T.; Thomine, S. Mechanisms of cadmium accumulation in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2020, 39, 322–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Rizvi, H.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Hannan, F.; Qayyum, M.F.; Hafeez, F.; Ok, Y.S. Cadmium stress in rice: toxic effects, tolerance mechanisms, and management: a critical review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 17859–17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, N.; Tajudin, M.; Khandaker, M.; Majrashi, A.; Alenazi, M.; Abdullahi, U.; Mohd, K. Cadmium toxicity symptoms and uptake mechanism in plants: a review. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2022, 84, e252143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Saifullah; Malhi, S.S.; Zia, M.H.; Naeem, A.; Bibi, S.; Farid, G. Role of mineral nutrition in minimizing cadmium accumulation by plants. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2010, 90, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Haxim, Y.; Islam, W.; Ahmad, M.; Ali, S.; Wen, X.; Khan, K.A.; Ghramh, H.A.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Impact of Cadmium Stress on Growth and Physio-Biochemical Attributes of Eruca sativa Mill. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, C.B.; Hashimoto-Sugimoto, M.; Negi, J.; Israelsson-Nordström, M.; Azoulay-Shemer, T.; Rappel, W.J.; Iba, K.; Schroeder, J.I. CO2 Sensing and CO2 Regulation of Stomatal Conductance: Advances and Open Questions. Trends Plant Sci 2016, 21, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Joshi, J.; Kataria, S.; Verma, S.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Jain, M.; Pathak, K.; Rastogi, A.; Brestic, M. Regulation of the Calvin cycle under abiotic stresses: An overview. Plant life under changing environment 2020, 681–717. [Google Scholar]

- Dikšaitytė, A.; Kniuipytė, I.; Žaltauskaitė, J.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Asard, H.; AbdElgawad, H. Enhanced Cd phytoextraction by rapeseed under future climate as a consequence of higher sensitivity of HMA genes and better photosynthetic performance. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 908, 168164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, A.; He, N.; Yang, D.; Liu, M. Exogenous silicon alleviates cadmium toxicity in rice seedlings in relation to Cd distribution and ultrastructure changes. Journal of soils and sediments 2018, 18, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, D.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Effect of water-driven changes in rice rhizosphere on Cd lability in three soils with different pH. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2020, 87, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bao, Q.; Chu, Y.; Sun, H.; Huang, Y. Jasmonic acid alleviates cadmium toxicity through regulating the antioxidant response and enhancing the chelation of cadmium in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environmental Pollution 2022, 304, 119178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahad, S.; Rehman, A.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Saud, S.; Kamran, M.; Ihtisham, M.; Khan, S.U.; Turan, V.; ur Rahman, M.H. Rice responses and tolerance to metal/metalloid toxicity. In Advances in rice research for abiotic stress tolerance; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Yotsova, E.K.; Dobrikova, A.G.; Stefanov, M.A.; Kouzmanova, M.; Apostolova, E.L. Improvement of the rice photosynthetic apparatus defence under cadmium stress modulated by salicylic acid supply to roots. Theoretical and Experimental Plant Physiology 2018, 30, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkovic, V.; Markovic, D.; Dahlin, I. Decoding neighbour volatiles in preparation for future competition and implications for tritrophic interactions. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2016, 23, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; O’Neill Rothenberg, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ke, Y.; Wang, H.C. Volatile organic compounds as mediators of plant communication and adaptation to climate change. Physiologia Plantarum 2022, 174, e13840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñuelas, J.; Staudt, M. BVOCs and global change. Trends in Plant Science 2010, 15, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.M.; Blande, J.D.; Souza, S.R.; Nerg, A.M.; Holopainen, J.K. Plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in ozone (O3) polluted atmospheres: the ecological effects. J Chem Ecol 2010, 36, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, F.; Schnitzler, J.P. Abiotic stresses and induced BVOCs. Trends Plant Sci 2010, 15, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhu, G.; He, W.; Xie, J.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, T. Soil cadmium stress reduced host plant odor selection and oviposition preference of leaf herbivores through the changes in leaf volatile emissions. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 814, 152728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbiani, S.; Colzi, I.; Taiti, C.; Nissim, W.G.; Papini, A.; Mancuso, S.; Gonnelli, C. Smelling the metal: volatile organic compound emission under Zn excess in the mint Tetradenia riparia. Plant Science 2018, 271, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Huang, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Wu, L.; Song, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Han, C.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Y.; et al. Water management affects arsenic and cadmium accumulation in different rice cultivars. Environ Geochem Health 2013, 35, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, L.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, H.; Tian, S. Sulfur and water management mediated iron plaque and rhizosphere microorganisms reduced cadmium accumulation in rice. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Saito, T.; Lämsä, M.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.M.; Suzuki, M.; Ohyama, K.; Muranaka, T.; Ohara, K.; Yazaki, K. Plants utilize isoprene emission as a thermotolerance mechanism. Plant Cell Physiol 2007, 48, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattini, M.; Loreto, F.; Fini, A.; Guidi, L.; Brunetti, C.; Velikova, V.; Gori, A.; Ferrini, F. Isoprenoids and phenylpropanoids are part of the antioxidant defense orchestrated daily by drought-stressed Platanus × acerifolia plants during Mediterranean summers. New Phytol 2015, 207, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picazo-Aragonés, J.; Terrab, A.; Balao, F. Plant volatile organic compounds evolution: Transcriptional regulation, epigenetics and polyploidy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delory, B.M.; Delaplace, P.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; du Jardin, P. Root-emitted volatile organic compounds: can they mediate belowground plant-plant interactions? Plant and Soil 2016, 402, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, N.H.; Vo, H.T.; van Doan, C.; Hamow, K.A.; Le, K.H.; Posta, K. Volatile organic compounds shape belowground plant–fungi interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1046685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlemann, J.K.; Klempien, A.; Dudareva, N. Floral volatiles: from biosynthesis to function. Plant Cell Environ 2014, 37, 1936–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Klempien, A.; Muhlemann, J.K.; Kaplan, I. Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytologist 2013, 198, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichersky, E.; Noel, J.P.; Dudareva, N. Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science 2006, 311, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, I.T.; Halitschke, R.; Paschold, A.; von Dahl, C.C.; Preston, C.A. Volatile signaling in plant-plant interactions: “talking trees” in the genomics era. Science 2006, 311, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusià, J.; Peñuelas, J. β-Ocimene, a Key Floral and Foliar Volatile Involved in Multiple Interactions between Plants and Other Organisms. Molecules 2017, 22, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusia, J.; Peñuelas, J. Floral volatile organic compounds: Between attraction and deterrence of visitors under global change. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2013, 15, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waelti, M.O.; Page, P.A.; Widmer, A.; Schiestl, F.P. How to be an attractive male: floral dimorphism and attractiveness to pollinators in a dioecious plant. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2009, 9, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Rizvi, H.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Hannan, F.; Qayyum, M.F.; Hafeez, F.; Ok, Y.S. Cadmium stress in rice: toxic effects, tolerance mechanisms, and management: a critical review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 17859–17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Shi, W.; Ji, Q.; He, F.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Xu, M. Badh2, encoding betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase, inhibits the biosynthesis of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, a major component in rice fragrance. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1850–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Wang, W.; Yamaji, N.; Fukuoka, S.; Che, J.; Ueno, D.; Ando, T.; Deng, F.; Hori, K.; Yano, M.; et al. Duplication of a manganese/cadmium transporter gene reduces cadmium accumulation in rice grain. Nature Food 2022, 3, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).