1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the commercial use of nuclear energy, the issue of disposal of nuclear waste has remained largely unresolved. Currently proposed recycling methods [

1], such as hydrometallurgical-water extraction processes or pyrometallurgical salt-mediated separation and subsequent electrorefining, use numerous solvents or are still ineffective and environmentally unfriendly. This is especially true for the widely applied extraction method PUREX (Plutonium-Uranium Recovery by Extraction) which allows to separate plutonium and uranium in a liquid-liquid system (see [

1,

2] for an overview). A similar method can also be applied for separation of americium and curium [

3,

4].

Here, we present a novel recycling method based on distillation of the spent nuclear fuel (SNF), which is particularly (but not only) useful for the new generation of nuclear reactors working at high temperatures with liquid fuels. The mostly developed concepts are Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) [

5] or Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR) [

6,

7]. Whereas the former applies fluorides or chlorides of fissile isotopes simultaneously as fuel and coolant, the latter has separate loops for liquid chloride or metallic fuel and metallic coolant, being liquid lead. The fast-neutron version of MSR and DFR can burn down even not fissile isotopes of uranium and plutonium and in combination with the distillation-based reprocessing of SNF of older reactor generations can lead an environment friendly solution of modern nuclear power plants. First of all, the method proposed is a dry method without any solvents and can be used for separation of a large number chemical elements, which significantly reduces amount of the nuclear waste and recover the most valuable of them (e.g., rare earth elements as it has still been investigated in a conceptual design for NdFeB magnet recycling in [

8]). Additionally, as it will be shown here, the method is very effective and of large separation accuracy, limiting the burden on the environment.

2. Pyroprocessing Separation Plant

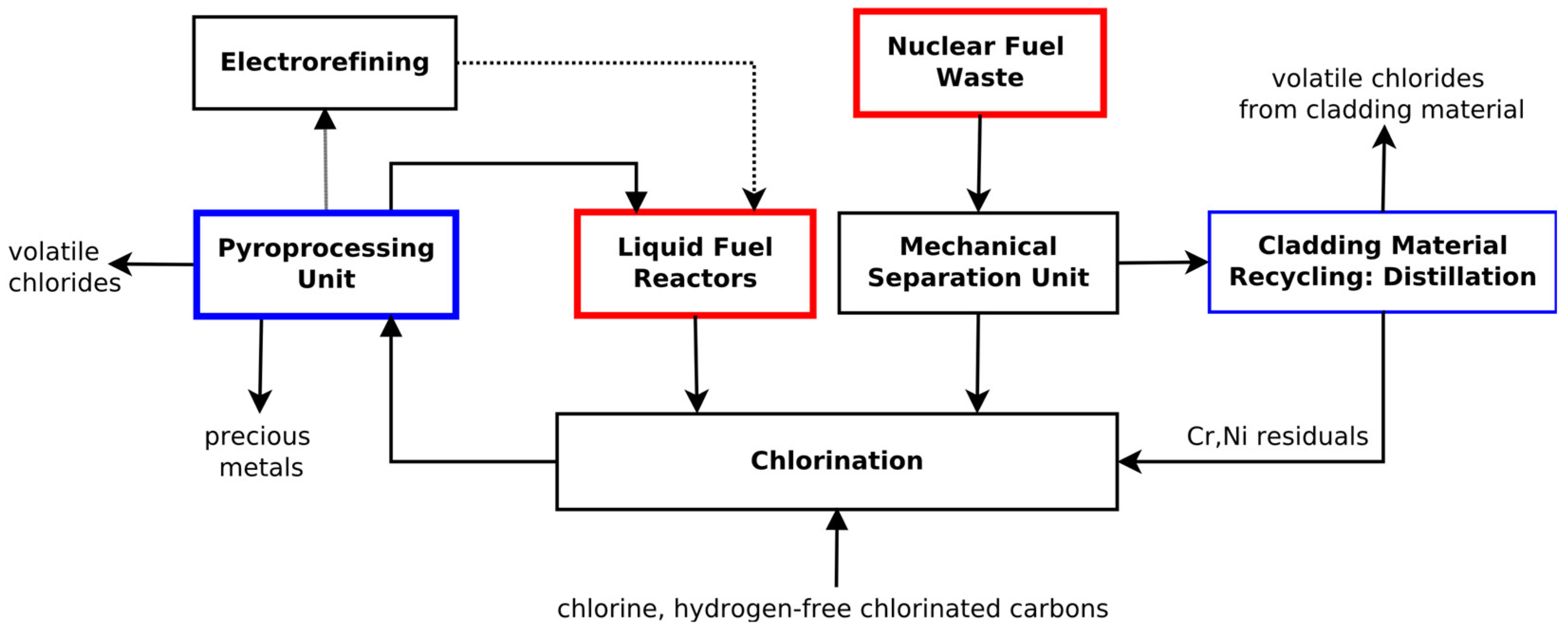

In

Figure 1, a model of a pyroprocessing separation plant that take into account different physical and chemical properties of recycled materials is presented. Starting with SNF in form of spent uranium rods a mechanical separation unit will be necessary to prepare the material for the following chlorination process. The zirconium cladding material of the fuel rods can also be shredded and recycled. Chlorination can be performed by means of carbon dioxide-forming tetrachloromethane [

9]. Application of chlorides with their strongly different boiling points will allow to volatilize the recycled material and use distillation as the main separation method.

After chlorination, the actinides can be separated from fission products in the pyroprocessing separation unit (PPU) and further used as fuel material for liquid fuel reactors. The distillation process should be designed in such a way that individual chemical elements have to be separated with a high accuracy. Electrorefining [

9] can be additionally used here for the eventual reduction of chlorides or metallic components, depending on the type of the fuel needed for the liquid fuel reactor [

10,

11,

12].

The PPU utilizes an entirely new reprocessing approach. For safety reasons, a closed distillation system is supposed in order to exclude leakages and emissions of radioactivity or chemically harmful components down to well below the ppm range. Contrary to chemical industry, the operation time of the facility needed for separation of different chemical elements is much less important than their final purity of the ppm range. Thus, a distillation column concept proposed here follows the principle of a fractionated discontinuous separation column under high reflux ratios, where fractions are usually obtained as a condensed distillation product due to decreasing volatility of the subsequent separated fractions. We are going, however, considerably further and would like to apply the total-reflux principle according to which the distillation column would operate as a closed system in two cyclically repeating operating steps for each separable fraction.

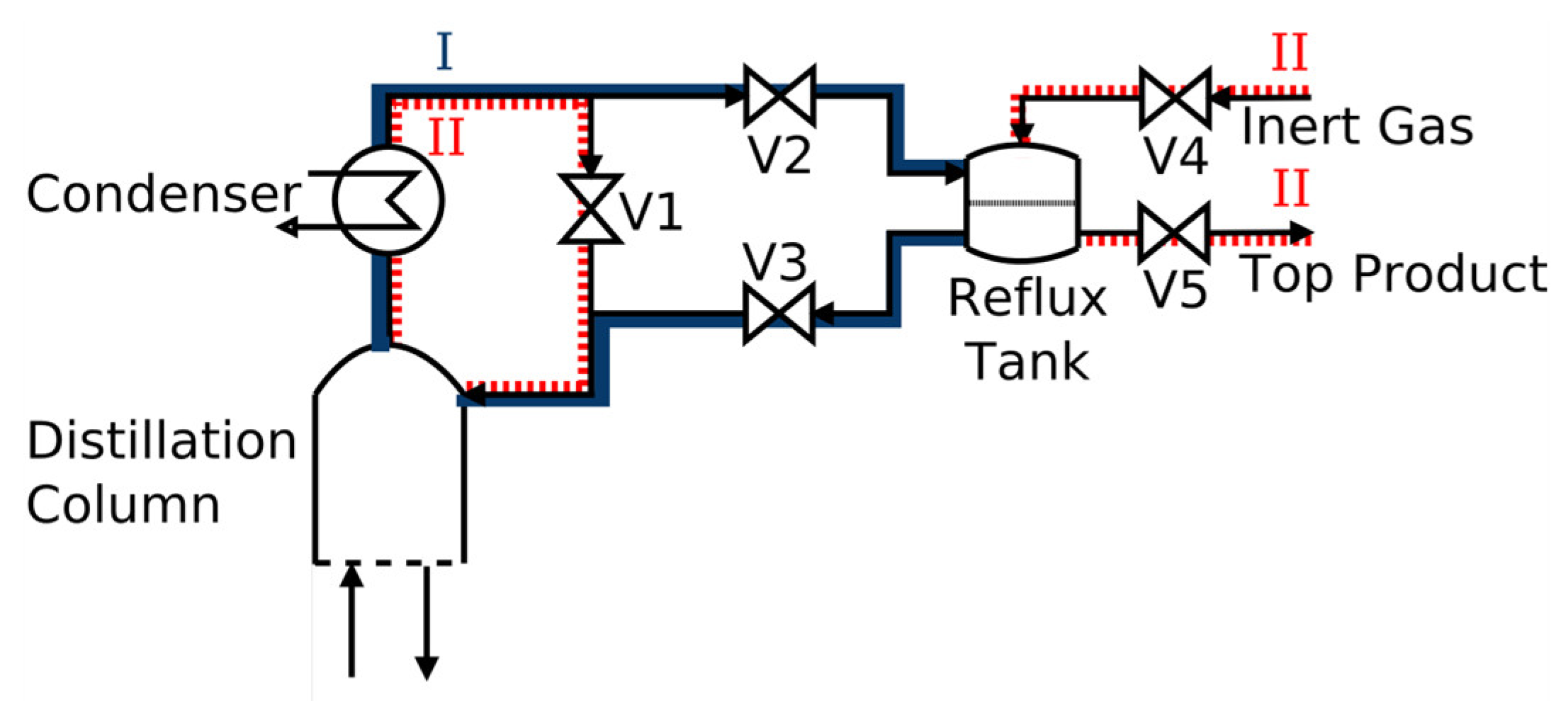

The two operation steps of the distillation column are illustratively shown in

Figure 2. In the first operating step, the distillation feed mixture is initially fed into the evaporator while the distillation column is preheated. Then, a steady-state total reflux condition is reached in the column, and the entire reflux is collected in the reflux tank from where the distillation product is completely recycled back to the distillation column. In the second operating step, the distillation product is removed by closing the reflux tank and removing the product by closing valves V2 and V3 and opening product removal valve V5. During the removal of the distillation product, inerting through the open V4 maintains a constant pressure in the system. Meanwhile, the remaining molten salt mixture circulates in the distillation column, being directly condensed out from the condenser and directly fed back to the column. The two main operating steps should be repeated in progressing process cycles (PPC) until all distillation product fractions have been obtained.

3. 3. Total-Reflux Distillation Process

In the following, we would like to demonstrate effectiveness of the proposed total-reflux distillation process for the reprocessing of nuclear waste.

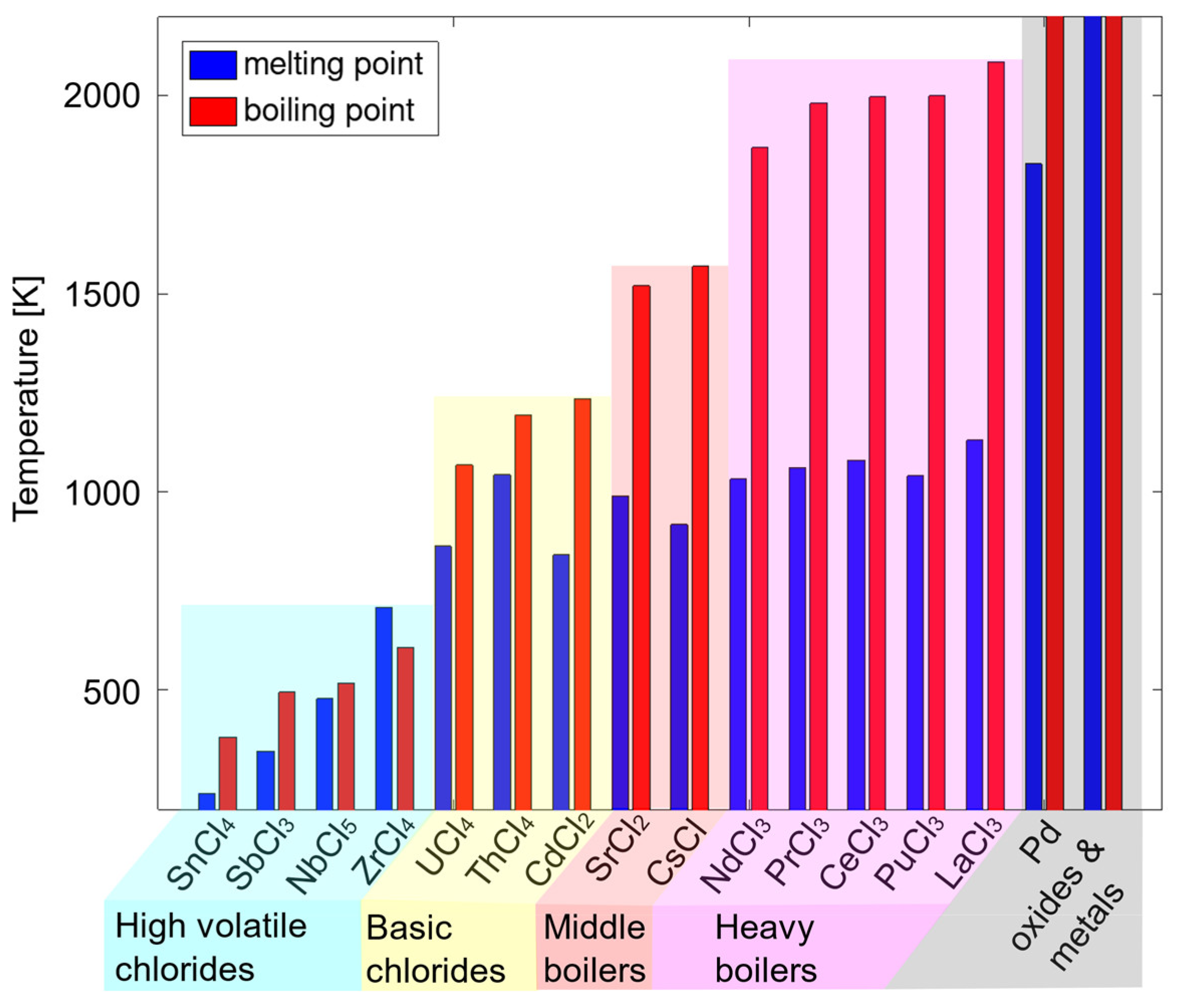

Figure 3 displays melting and boiling points of some chlorides representing both fissile actinides and fission products.

The high volatile chlorides require a special distillation treatment discussed already in our previous paper [

13]. The basic, middle and heavy boilers can be then divided into less and more volatile chloride groups defined by the 1600 K boiling point, defined by the critical temperature of uranium tetrachloride of 1598 K [

14]. The two groups will undergo the distillation procedure in two different distillation columns. Additionally, there is a small group of non-volatile unchlorinated components which can be treated separately as more precious metallic components.

Since no experimental data of the vapour-liquid equilibria of any of binary mixtures of here discussed chlorides are available, the only method to simulate the total-reflux column is to utilize the idealized phase equilibria condition. Two models were used for the simulation of the total-reflux column. The first one is an independently developed code, which essentially requires no critical data of the pure components. The calculations are based on the Raoult’s law using partial vapour pressures [

13]. The program code was written in Octave (a freely available software for solving mathematical and numerical problems [

15]). To validate the simulation results of the Octave model, the ChemSep Lite total-reflux column model according to [

16] has been also applied which, however, requires considerably more substance property data, including critical data of the pure substances. The ideal phase equilibrium conditions and ideal enthalpy calculation of heat capacities for the ChemSep total-reflux column model could be easily adjusted analogous to the Octave model.

Composition of the main “thermal fission” products of the spent nuclear uranium rods is taken from [

17,

18,

19] and used as the chlorinated feed material. Then, the data for chlorides assuming 100% conversion rate have been used for chlorination. The unchlorinated metallic components should first be separated, for example, by electrorefining, and the feed mixture is then to split into two different distillation columns for a more and less volatile parts (see above). The feed mixture consists to 95 mole % of the uranium tetrachloride, other actinide chlorides make less than 1 mole % and the rest are the fission products. The uranium chlorides can be predominantly separated in the first column for more volatile components together with cadmium and cesium (see Figure 5). However, some small contributions are still visible in the second column for the less volatile part (see

Figure 4). Contrary to the first column, the second one should work in more than only one progressing process cycles (PPC).

Figure 4 shows exemplary the total-reflux simulations over five PPC within the Octave model of a twenty-six-stage total-reflux column. The distillation products already obtained in a previous cycle will be removed from the feed mixture of the next cycle. In the first PPC, the high-purity mixture of uranium and neptunium tetrachloride free of other chlorides is clearly evident in the first separation stage. In the last separation stage, plutonium trichloride is purified as a heavy-boiling product with possible impurities of uranium trichloride of about 3·10-3 to 5·10-3 mole%. In the second PPC, essentially the same chloride components as in the first PPC are enriched, but with higher proportions of uranium tetrachloride as a light boiler and higher uranium trichloride impurities (not shown in

Figure 4). Since light and heavy boiling components are withdrawn after each PPC, the boiling range of the chlorides remaining in the column decreases after each PPC. Thus, the increase of component contributions with the stage number is not so strong for higher PPC. In the third PPC, curium trichloride is obtained as a high-boiling distillation product with minor impurities of samarium trichloride within the range of 3·10-3 to 6·10-3 mole% and neodymium trichloride obtained as a high-pure heavy boiling product free from other chloride components. In the subsequent fourth and fifth PPC, the impurities then increase significantly due to the broadening of the range of medium-boiling components occurring, which then lead to higher product impurities. Thus, in the fourth PPC, samarium trichloride is obtained as a high-boiling component with the impurities of americium trichloride, cesium chloride and strontium dichloride shown in

Figure 4, as well as a high-boiling product composition of cesium chloride and europium trichloride with some impurities of americium trichloride in the ppm range. In fifth PPC, only cesium chloride with the low americium trichloride impurities shown can be possibly obtained as the heavy-boiling distillation product. For higher separation accuracies of these chlorides, a separation column with more separation stages would be required.

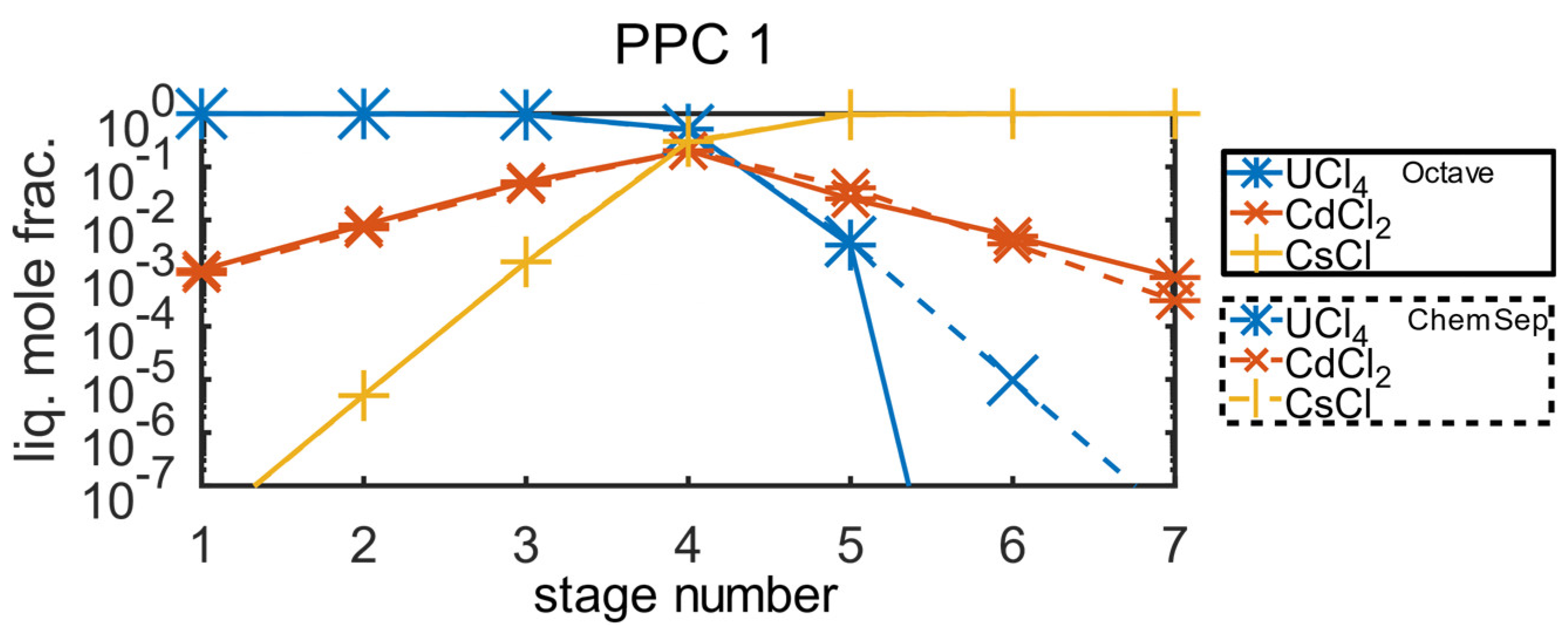

In

Figure 5, simulations performed within Octave and ChemSep models are compared. They are in an excellent agreement. A small deviation in the separation ability of uranium tetrachloride in the sixth separation stage can be visible in the logarithmic scale. This probably arises from different data used for the vapour pressure of uranium tetrachloride.

5. Conclusions

We can conclude that the Octave model shows reliable and realistic simulation results under idealized phase equilibrium conditions. On the other hand, depletion of uranium tetrachloride as a high boiler component can be also observed in enrichment of cesium chloride in the seventh separation stage. Both distillation products are impurified with a small amount of cadmium dichloride, but free of the other components. The calculations unambiguously confirm that the separation accuracy better than 10-4 mole% can be achieved for both uranium tetrachloride and cesium chloride. This is especially important for uranium component which makes up 95-mol% of all recycled material. From remaining 5-mol%, most of the chloride components can be also recovered as high-purity distillation products, including other actinide chlorides e.g., curium trichloride or plutonium trichloride.

Summarizing, we have shown that the proposed here pyroprocessing plant utilizing distillation process with total-reflux columns in a closed system can separate spent nuclear fuel very effectively with a very high accuracy. The recycling method enables segregation the nuclear waste into individual chemical elements, which allows to take into account the lifetime of radioactive isotopes. In this way, the amount of radioactive material intended for storage for more than 300 years can be significantly reduced and at the same time, valuable elements can be recovered for further use. While the study has been focused on recycling of standard uranium fuel rods, the proposed chlorination and distillation method can be particularly well applied to the next generation of fast nuclear reactors operating at high temperature using actinide chlorides as liquid fuel.

Author Contributions

D.B. – Conceptualization, lnvestigation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original stuff; K.C. – Conceptualization, Formal analysis, lnvestigation, Writing—original stuff, Supervision; D.W. – Validation, Data curation, Writing—reviewer; S.G. – lnvestigation, Methodology, Writing—reviewer; A.H. – Conceptualization, Software, Writing—reviewer; G.R. – Conceptualization, Validation, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. F. Simpson, J.D. Law, 2010, “Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing”, Technical report: INL/EXT-10-17753, Idaho National Laboratory.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- C. H. Castaño, “Nuclear fuel reprocessing”, Nuclear Energy Encyclopedia: Science, Technology, and Applications, John Wiley and Sons, 2011, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 121 126.

- X. Hérès, E. Ameil, I. Martinez, P. Baron, C. Hill, “The separation of extractants implemented in the Diamex-Sanex process”, IAEA inproceedings Atalante: Nuclear fuel cycle for a sustainable future (1), 2011.

- G. Modolo, A. Geist, M. Miguirditchian, “Minor actinide separations in the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuels”, Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy (Elsevier), 2015, pp. 245 287. [CrossRef]

- W. L. Carter, R. B. Lindauer, L. E. McNeese, “Design on an engineering-scale, vacuum distillation experiment for molten-salt reactor fuel”, Technical report: ORNL TM-2213, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1986.

- A. Huke, G. Ruprecht, D. Weißbach, S. Gottlieb, A. Hussein, and K. Czerski, “The Dual Fluid Reactor – A novel concept for a fast nuclear reactor of high efficiency,” Annals of Nuclear Energy (Elsevier), 2015, vol. 80, pp. 225–235. [CrossRef]

- J. Sierchuła, D. Weissbach, A. Huke, G. Ruprecht, K. Czerski, and M. P. Da¸browski, “Determination of the liquid eutectic metal fuel dual fluid reactor (DFRm) design – steady state calculations,” International Journal of Energy Research, 2019, vol. 43, no. 8, pp. 3692–3701. [CrossRef]

- D. Böhm, K. Czerski, S. Gottlieb, A. Huke and G. Ruprecht, “Recovery of Rare Earth Elements from NdFeB Magnets by Chlorination and Distillation”. processes 2023, 11, 577. [CrossRef]

- D. Böhm,K. Czerski, A. Huke, J.-C. Lewitz, D. Weißbach, S. Gottlieb, G. Ruprecht, 2020, “New Methods for Nuclear Waste Treatment of the Dual Fluid Reactor Concept”, Acta Physica Polonica B, vol. 51, pp. 893–898. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (contributor), 2000. “Electrometallurgical Techniques for DOE Spent Fuel Treatment: Final Report”, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (contributor), 1995, Electrometallurgical Techniques for DOE Spent Fuel Treatment – Status Report on Argonne National Laboratory’s R&D Activity Through Spring, Technical Report: 000087511 (No. DOE/EA-1148-R-053).

- S. D. Herrmann, S. X. Li, M. F. Simpson, S. Phongikaroon, 2006, “Electrolytic Reduction of Spent Nuclear Oxide Fuel as Part of an Integral Process to Separate and Recover Actinides from Fission Products.” Separation Science and Technology, vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 1965–83. [CrossRef]

- Perry, R. & Green, D. Green, D. (Ed.), 1997, “Perry’s Chemical Engineers Handbook 7th, Section 13: Distillation; Distillation”, McGraw-Hill, New York, ISBN: 0-07-049841-5.

- R. Keim, C. Keller, D. Brown, 1979, „Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie (Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic and Organometallic Chemistry). System-Nr. 55. Uranium Suppl. Vol. C.9.: Compounds with Chlorine, Bromine, Iodine.“, 8th edition Springer, Berlin, ISBN: 9783540933939.

- Eaton, John W., 2012, “GNU Octave and Reproducible Research.” Journal of Process Control, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1433–38. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Kooijman, R. Taylor, 2007-2019, “The ChemSep Book”, vol 2., public domain book for the use of ChemSep Software.

- Schwenk-Ferrero, 2013, “German Spent Nuclear Fuel Legacy: Characteristics and High-Level Waste Management Issues.” Science and Technology of Nuclear Installations, vol. 2013, pp. 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Koning, R. Forrest, M. Kellett, R. Mills, H. Henriksson, Y. Rugama, 2006, “The JEFF-3.1 Nuclear Data Library”, JEFF Report 21, OECD/NEA, Paris, France, ISBN 92-64-02314-3.

- “Cumulative Fission Yields C3 table”, International Atomic Energy Agency - Nuclear Data Section P.O. Box 100, Wagramer Strasse 5, A-1400 Vienna, Austria, 2022. https://www-nds.iaea.org/sgnucdat/c3.htm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).