Submitted:

09 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

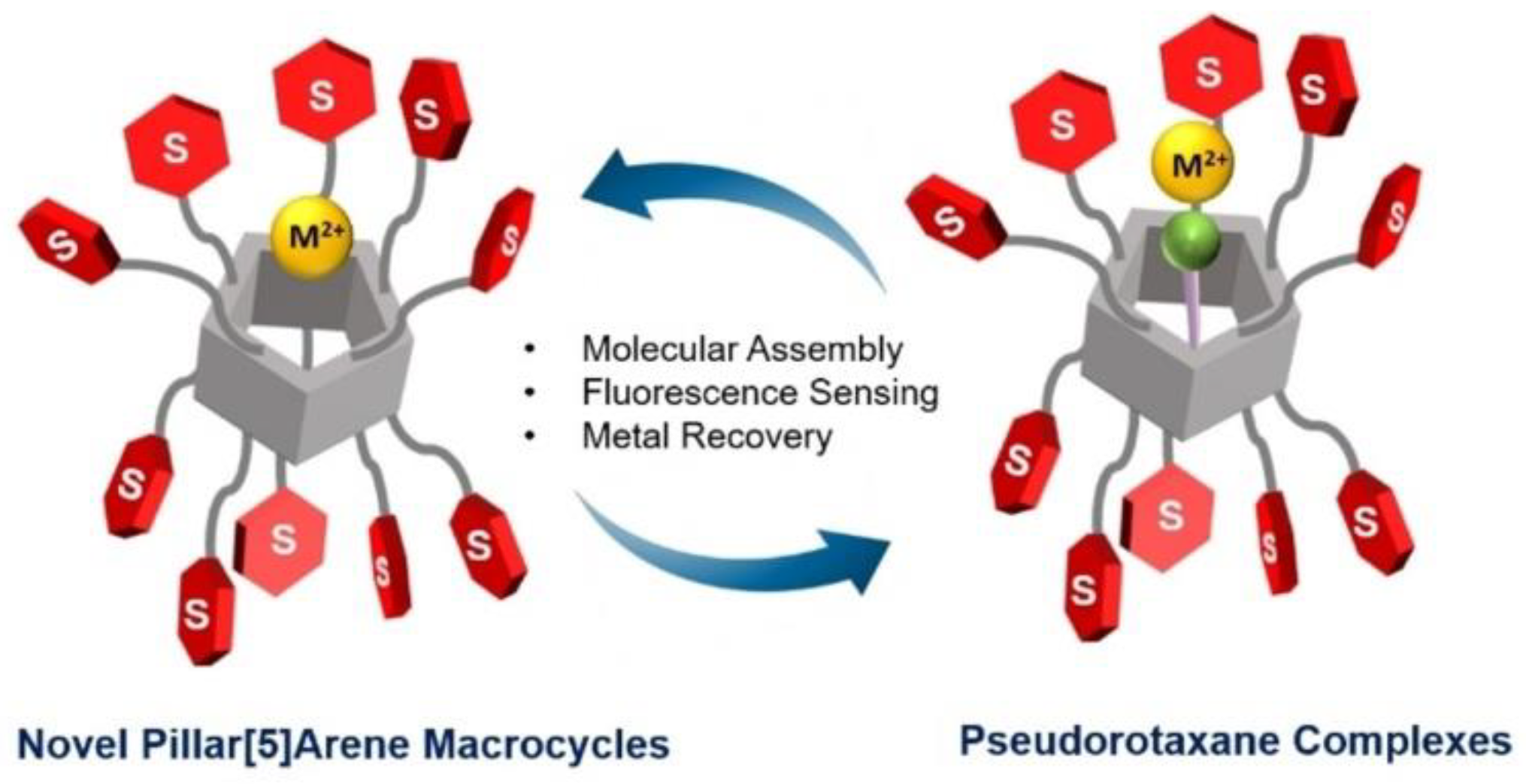

1. Introduction

2. Fluorescence Sensors

2.1. Single-stimulus responsive sensors

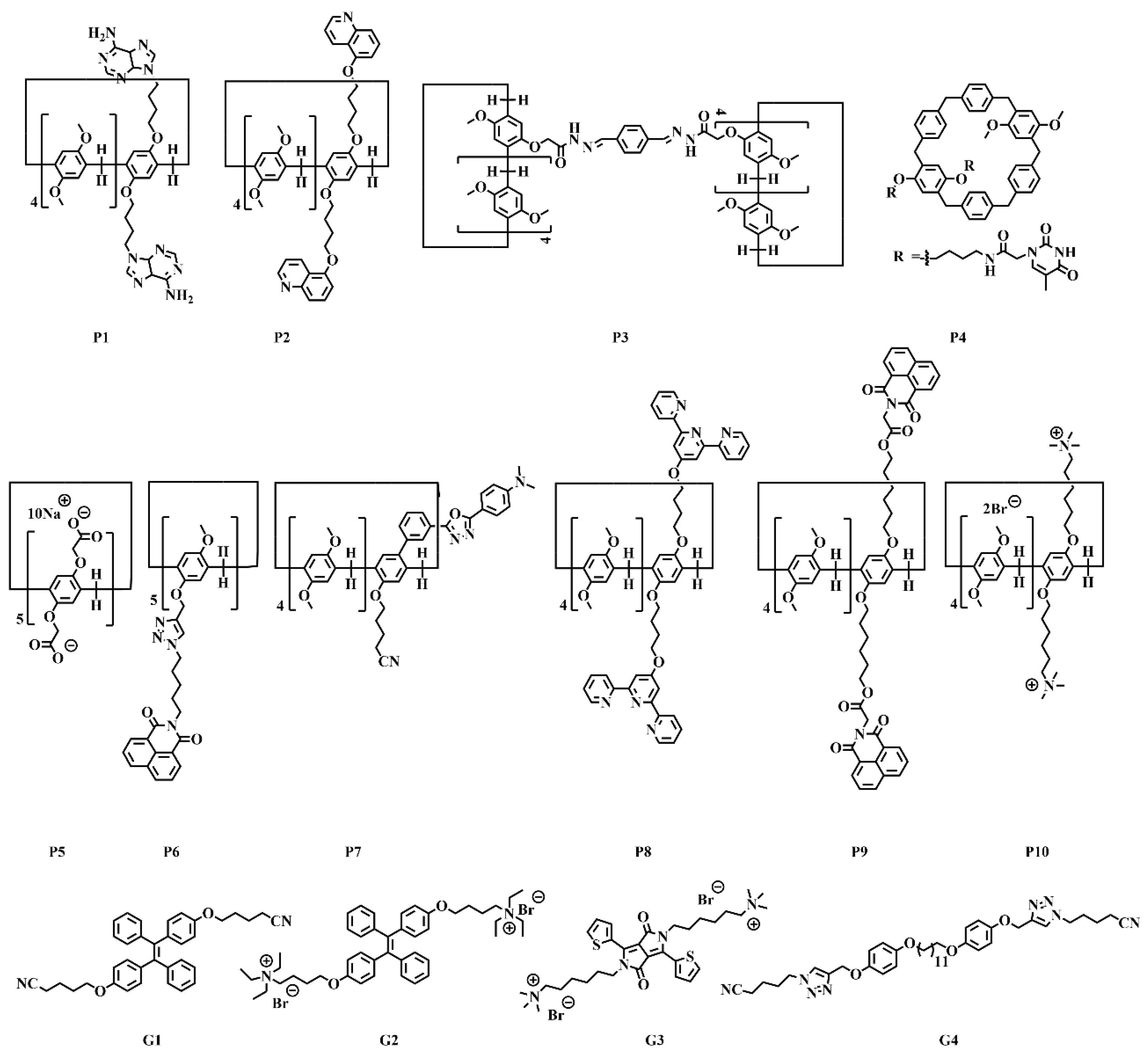

| Pillar[n]arenes | Guests | Coordinated metal ions |

Sensing properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | G1 | Ag+ | Analyte: Ag+. Detection type: turn−on. λex/λem: 310/470 nm. LOD: 1.50 × 10−7 mol/L. Liner range: 0−8.00 × 10−6 mol/L. Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 1/99. |

[38] |

| P2 | − | Ag+ | Analyte: hydrazine hydrate. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 310/450 nm. LOD: 2.68 × 10−8 mol/L. Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 4/1. |

[39] |

| P3 | − | Hg2+ | Analyte: Hg2+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 332/486 nm. LOD: 4.30 × 10−8 mol/L. Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 1/1. |

[40] |

| P4 | G2 | Hg2+ | Analyte: Hg2+. Detection type: turn−on. λex/λem: 312/388 nm. LOD: 3.00 × 10−7 mol/L. Liner range: 0−1.50 × 10−5 mol/L. Solvent: CHCl3/acetone/H2O = 1/4/495. |

[41] |

| P5 | G3 | Hg2+ | Analyte: Hg2+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 510/565 nm. LOD: 7.17 × 10−7 mol/L. Solvent: H2O. |

[42] |

| P6 | − | Cu2+ | Analyte: Cu2+. Detection type: ratiometric. λex/λem: 333/384 nm. LOD: 1.85 × 10−7 mol/L. Solvent: CH2Cl2/CH3CN = 1/1. |

[43] |

| P7 | − | Cu2+ | Analyte: Cu2+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem = 310/411 nm. Solvent: chloroform |

[44] |

| P8 | G4 | Zn2+ | Analyte: nitrobenzene. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 295/460 nm. LOD: 1.66 × 10−4 mol/L. Liner range: 1.00−5.00 × 10−5 mol/L. Solvent: CH3CN/CHCl3 = 1/1. |

[45] |

| P9 | − | Fe3+ | Analyte: Fe3+, L-Cys. Detection type: turn−off/on. λex/λem: 375/535 nm. LOD: 6.06 × 10−8 mol/L (Fe3+); 1.00 × 10−8 mol/L (L-Cys). Solvent: cyclohexanol. |

[46] |

| P9, P10 | P10 | Fe3+ | Analyte: Fe3+, H2PO4−. Detection type: turn−off/on. λex/λem: 375/530 nm. LOD: 7.54 × 10−9 mol/L. Solvent: cyclohexanol/H2O = 1/20. |

[47] |

2.2. Dual-stimuli responsive sensors

2.3. Multi-stimuli responsive sensors

3. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aggregation-induced emission | AIE |

| Critical gelation concentration | CGC |

| Fluorescence resonance energy transfer | FRET |

| Hydrazine hydrate | DH |

| Restriction of intramolecular rotation | RIR |

| Limit of detection | LOD |

| Nitro aromatic compound | NAC |

| Photo-induced electron transfer | PET |

| Supramolecular assembly induced emission enhancement | SAIEE |

| Supramolecular organic framework | SOF |

| Supramolecules polymer network | SPN |

| Tetraphenylvinyl | TPE |

| Trifluoroacetic acid | TFA |

| Triethylamine | TEA |

References

- Belmont-Sánchez, J.C.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; García-Rubiño, M.E.; Matilla-Hernández, A.; Niclós-Gutiérrez, J.; Castiñeiras, A.; Frontera, A. Supramolecular nature of multicomponent crystals formed from 2,2′-thiodiacetic acid with 2,6-diaminopurine or N9-(2-Hydroxyethyl)adenine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groschel, A.H.; Mueller, A.H.E. Self-assembly concepts for multicompartment nanostructures. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11841–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujahid, A.; Afzal, A.; Dickert, F.L. . Transitioning from Supramolecular Chemistry to Molecularly Imprinted Polymers in Chemical Sensing. Sensors 2023, 23, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, Z.; Dou, Y.; Kim, J.; Dou, X. Two-step self-assembly of hierarchically-ordered nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 11688–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; He, X.; Jiang, H.; Tang, H.; Cao, D.; Tang, B. A conjugated polymeric supramolecular network with aggregation-induced emission enhancement: an efficient light-harvesting system with an ultrahigh antenna effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9908–9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, D.; Shi, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.; Hao, X.Q.; Song, M.P. Tailored supramolecular cage for efficient bio-labeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, C. Morphology transformation of self-assembled organic nanomaterials in aqueous solution induced by stimuli-triggered chemical structure changes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 16059–16104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.F.; Ren, T.L.; Wang, C.; Li, D.L. Selective and accurate detection of nitrate in aquaculture water with surface-enhanced raman scattering (SERS) using gold nanoparticles decorated with β-cyclodextrins. Sensors 2024, 24, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.Y.; Bae, J.; Ryu, J.H.; Lee, M. Ordered nanostructures from the self-assembly of reactive coil-rod-coil molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 650–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, R. Structural and biomechanical properties of supramolecular nanofiber-based hydrogels in biomedicine. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, T.P.; Nedumpurath, P.J.; Karunakaran, S.C.; Schuster, G.B.; Hud, N.V. One-pot formation of pairing proto-RNA nucleotides and their supramolecular assemblies. Life 2023, 13, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoriu, A.; Chiriac, A.P.; Rusu, A.G.; Ghilan, A.; Ciolacu, D.E.; Stoica, I.; Nita, L.E. Morphological evaluation of supramolecular soft materials obtained through co-assembly processes. Gels 2023, 9, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, N.S.; Jin, L.Y. Applications of supramolecular polymers generated from pillar[n]arene-based molecules. Polymers 2023, 15, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Liu, P.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, N.; Jin, L.Y. Supramolecular nanoassemblies of rim-differentiated pillar[5]arene-rod-coil macromolecules via host-guest interactions for the sensing of cis-trans isomers of 1,4-diol-2-butene. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1291, 136054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Q. , He, C. Novel porous beta-cyclodextrin/pillar[5]arene copolymer for rapid removal of organic pollutants from water. Carbohyd. Polym. 2019, 216, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.W.; Chen, L.J.; Wang, C.; Tan, H.W.; Yu, Y.H.; Li, X.P.; Yang, H.B. Cross-linked supramolecular polymer gels constructed from discrete multi-pillar[5]arene metallacycles and their multiple stimuli-responsive behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8577–8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, X.Y.; Yang, Y.W. Pyridine-conjugated pillar[5]arene: from molecular crystals of blue luminescence to red-emissive coordination nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11976–11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Shi, B.; Xing, H.; Sun, Y.; Lu, S.; Shangguan, L.; Li, X.; Huang, F.; Stang, P. J. Formation of planar chiral platinum triangles via pillar[5]arene for circularly polarized luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17340–17345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Yin, X.; Wang, D.; Han, T.; Tang, B.Z. Synergistically boosting the circularly polarized luminescence of functionalized pillar[5]arenes by polymerization and aggregation. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2305149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhang, Q.W.; Gu, Q.; Liu, Z.; He, X.; Tian, Y. Pillar[5]arene-based fluorescent sensor array for biosensing of intracellular multi-neurotransmitters through host–guest recognitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, W.; Sun, Y.; Lu, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Stang, P.J. Pillar[5]arene-containing metallacycles and host-guest interaction caused aggregation-induced emission enhancement platforms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16930–16934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogoshi, T.; Yamagishi, T.; Nakamoto, Y. Pillar-shaped macrocyclic hosts pillar[n]arenes: new key players for supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7937–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescop, C. Coordination-driven syntheses of compact supramolecular metallacycles toward extended metallo-organic stacked supramolecular assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Onge, P.B.J.; Chen, T.C.; Langlois, A. Iron-coordinating π-conjugated semiconducting polymer: morphology and charge transport in organic field-effect transistors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 8213–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.L.; Xiao, X.; Cong, H. Cucurbit[n]uril-based coordination chemistry: from simple coordination complexes to novel poly-dimensional coordination polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9480–9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Saha, M.L.; Stang, P.J. Hierarchical assemblies of supramolecular coordination complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2047–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Wang, L.; Lv, X.; Chao, J.; Wei, X.; Wang, P. Dual-responsive [2]Pseudorotaxane on the basis of a pH-Sensitive pillar[5]arene and its application in the fabrication of metallosupramolecular polypseudorotaxane. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 2716–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shangguan, L.; Shi, B. A multi-responsive cross-linked supramolecular polymer network constructed by mussel yield coordination interaction and pillar[5]arene-based host–guest complexation. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12230–12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhong, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Muddassir, M.; Daniel, O.; Raj Jayswal, M.; Prakash, O.; Dai, Z.; Ma, A. New transition metal coordination polymers derived from 2-(3,5-Dicarboxyphenyl)-6-carboxybenzimidazole as photocatalysts for dye and antibiotic decomposition. Molecules 2023, 28, 7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castriciano, M.A.; Zagami, R.; Mazzaglia, A.; Romeo, A.; Monsù Scolaro, L. A kinetic investigation of the supramolecular chiral self-assembling process of cationic organometallic (2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine)methylplatinum(II) complexes with poly(L-glutamic acid). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Guo, X.; Chang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Jin, L.Y.; Feng, S. A mitochondria-tracing fluorescent probe for real-time detection of mitochondrial dynamics and hypochlorous acid in live cells. Dyes Pigment. 2022, 201, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sedgwick, A.C.; Hirao, T.; Sessler, J.L. Supramolecular fluorescent sensors: an historical overview and update. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2021, 427, 213560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Chen, D.X.; Qiu, Y.C.; Yang, X.Y.; Xu, B; Tian, W. J.; Yang, Y.X. Stimuli-responsive blue fluorescent supramolecular polymers based on a pillar[5]arene tetramer. Chem Commun. 2014, 50, 8231–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J.; Chen, M.H.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.H. Electrospun fibrous mats with conjugated tetraphenylethylene and mannose for sensitive turn−on fluorescent sensing of escherichia coli. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5177–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Hu, X.Y.; Chen, D.; Shi, J.B.; Dong, Y.P.; Lin, C.; Pan, Y.; Wang, L.Y. Pillar[5]arene-based side-chain polypseudorotaxanes as an anion-responsive fluorescent sensor. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 2224–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tang, B.Z. Fluorescent sensors based on aggregation-induced emission: recent advances and perspectives, ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1382–1399. 2.

- Shi, H.P.; Wang, S.J.; Qin, L.Y.; Gui, C.; Zhang, X.L.; Fang, L.; Chen, S.M.; Tang, B.Z. Construction of two AIE luminogens comprised of a tetra-/tri-phenylethene core and carbazole units for non-doped organic light-emitting diodes, Dyes Pigment. 2018, 149, 323–330. 149.

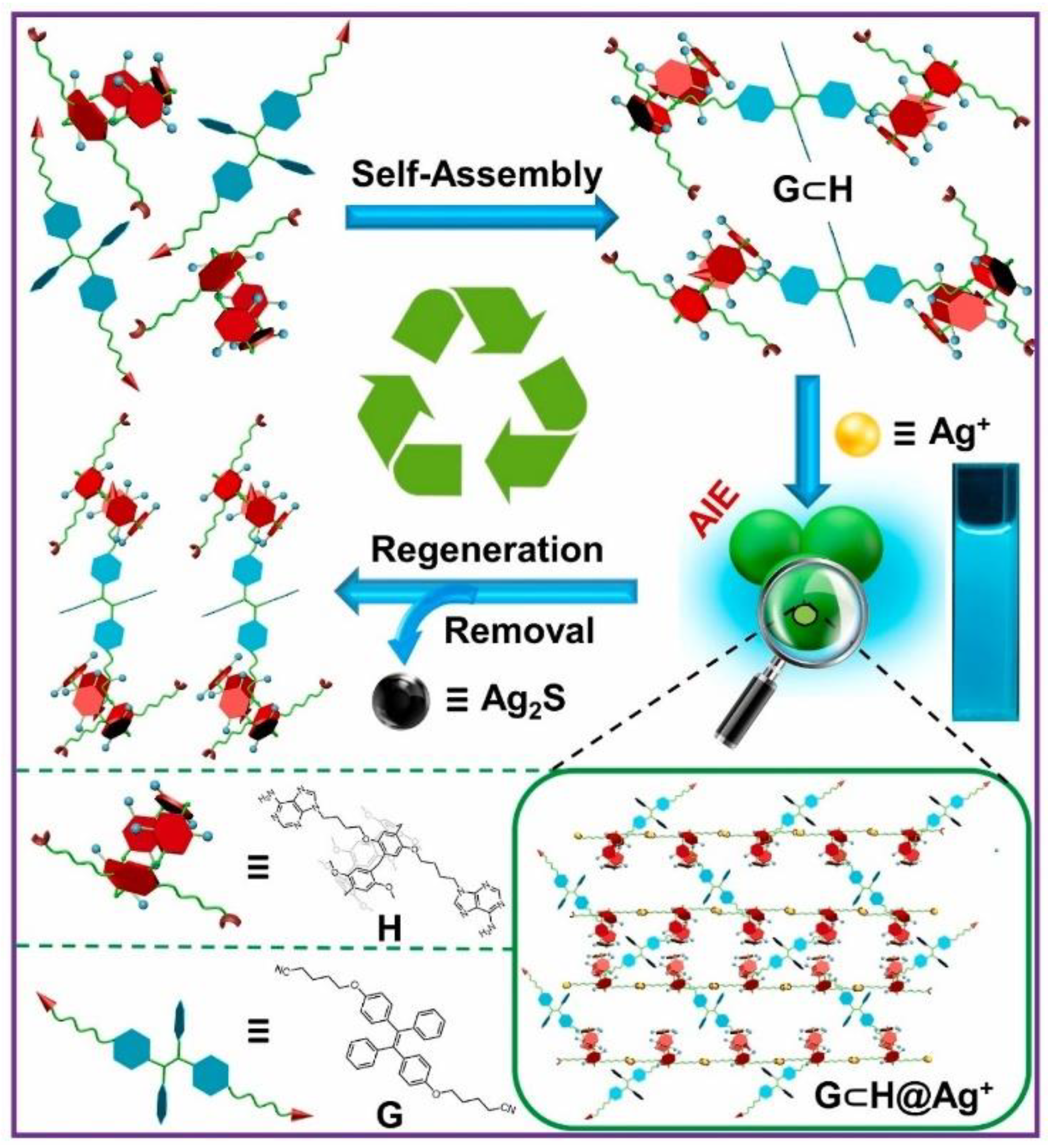

- Wang, W.M.; Dai, D.; Wu, J.R.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.W. Renewable supramolecular assembly-induced emission enhancement system for efficient detection and removal of silver(I). Dyes Pigment. 2022, 207, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

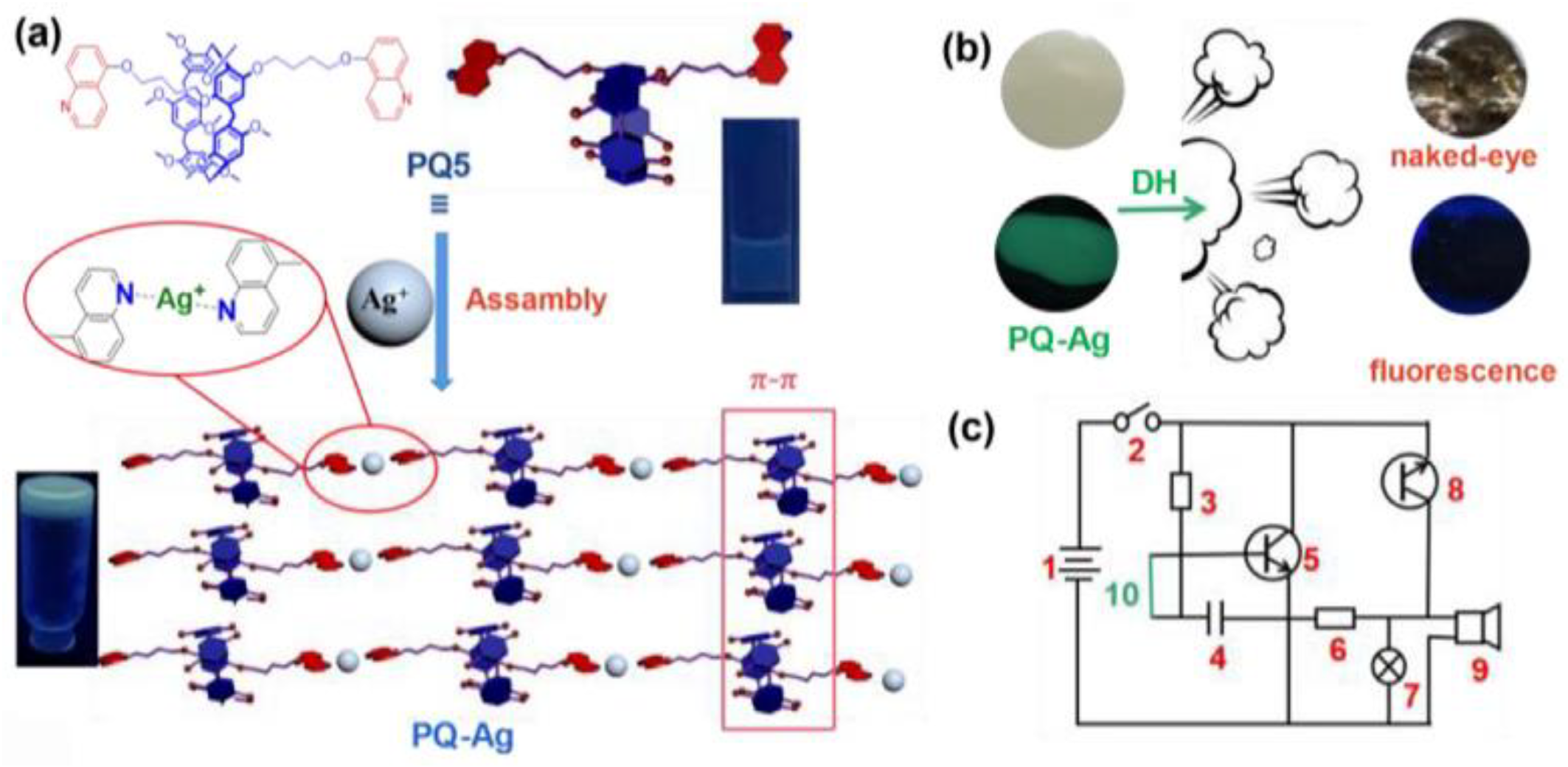

- Jia, Y.; Guan, W.L.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.P.; Shi, B.; Yao, H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wei, T.B.; Lin, Q. Novel conductive metallo-supramolecular polymer AIE gel for multi-channel highly sensitive detection of hydrazine hydrate. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Jiang, X.M.; Ma, X.Q.; Liu, J.; Yao, H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wei, T.B. Novel bispillar[5]arene-based AIEgen and its’ application in mercury(II) detection. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 272, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

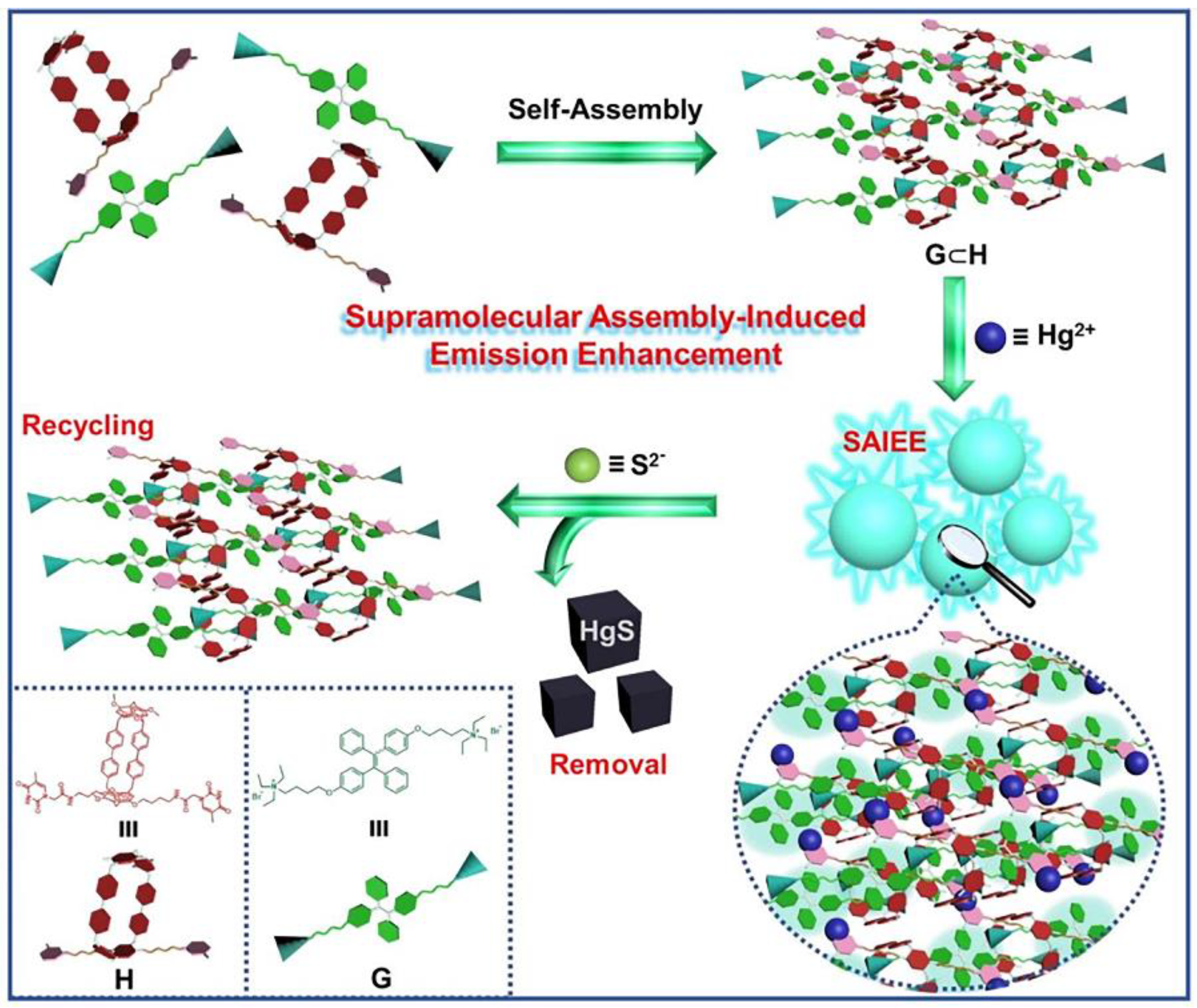

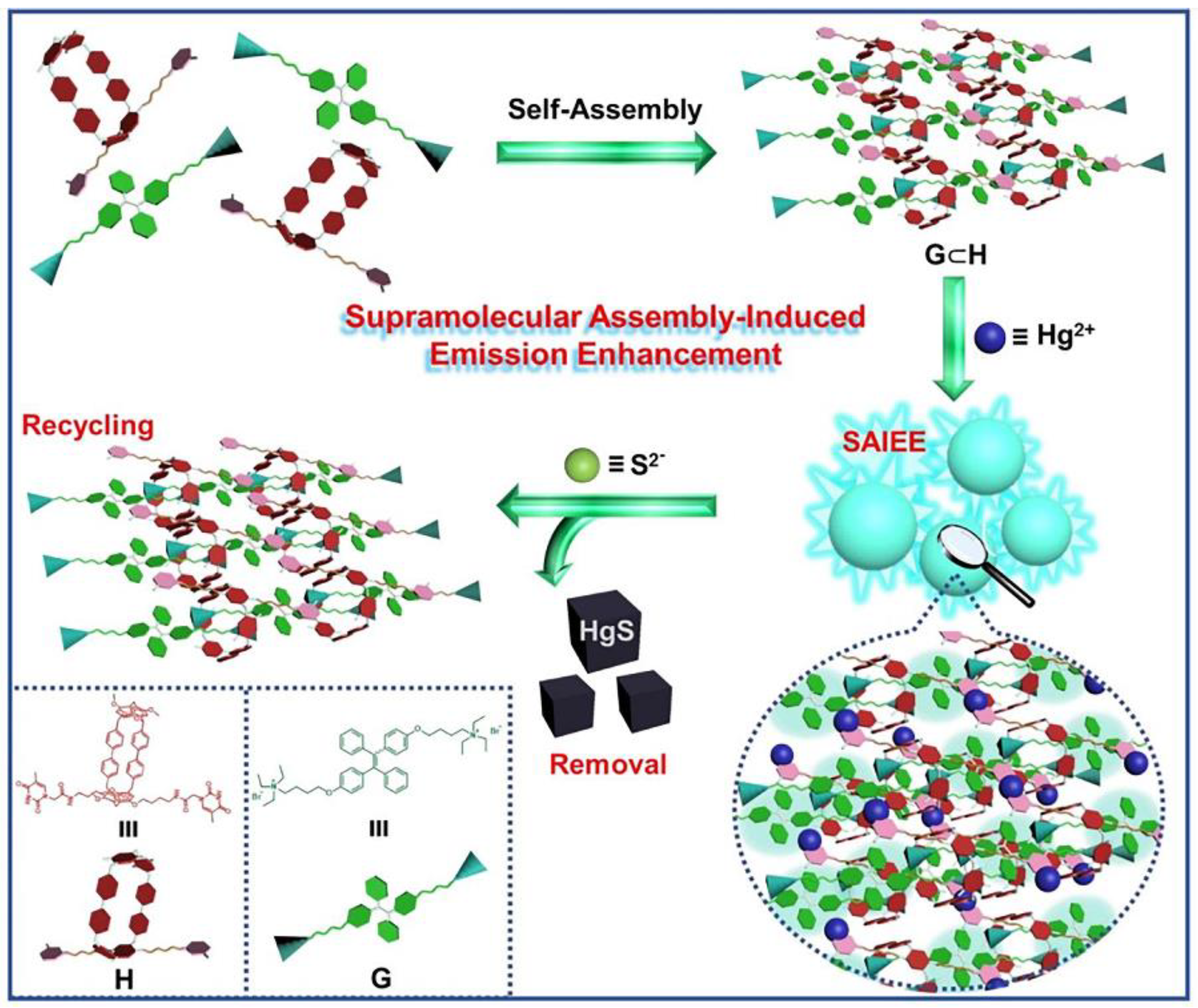

- Dai, D.H.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.Y.; Wu, J.R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.M.; Yang, Y.W. Supramolecular assembly-induced emission enhancement for efficient mercury(II) detection and removal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4756–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Ran, X.; Tang, H.; Cao, D. Green, efficient detection and removal of Hg2+ by water-soluble fluorescent pillar[5]arene supramolecular self-assembly. Biosens. 2022, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Chen, C.Y.; Gao, L.; Li, Y.; Lee, Z.H.; Zhao, H.; Sue, A.C.; Chang, K.C. Highly selective Cu2+ detection with a naphthalimide-functionalised pillar[5]arene fluorescent chemosensor. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Han, J. Supramolecular brush polymers prepared from 1,3,4-oxadiazole and cyanobutoxy functionalised pillar[5]arene for detecting Cu2+. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.; Xu, Y.H.; Han, Y.; Yan, C.G.; Su, D.W.; Wang, C.Y. Pillar[5]arene-based “three-components” supramolecular assembly and the performance of nitrobenzene-based explosive fluorescence sensing. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Li, Y.F.; Zhong, K.P.; Qu, W.J.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B.; Lin, Q. A bis-naphthalimide functionalized pillar[5]arene-based supramolecular π-gel acts as a multi-stimuli-responsive material. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 16167–16173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Li, Y.F.; Zhong, K.P.; Qu, W.J.; Chen, X.P.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B.; Lin, Q. A novel pillar[5]arene-based supramolecular organic framework gel to achieve an ultrasensitive response by introducing the competition of cation⋯π and π⋯π interactions. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 3624–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Chen, X.P.; Liang, G.Y.; Zhong, K.P.; Lin, Q.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B. A novel water soluble pillar[5]arene and phenazine derivative self-assembled pseudorotaxane sensor for the selective detection of Hg2+ and Ag+ with high selectivity and sensitivity. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 10148–10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

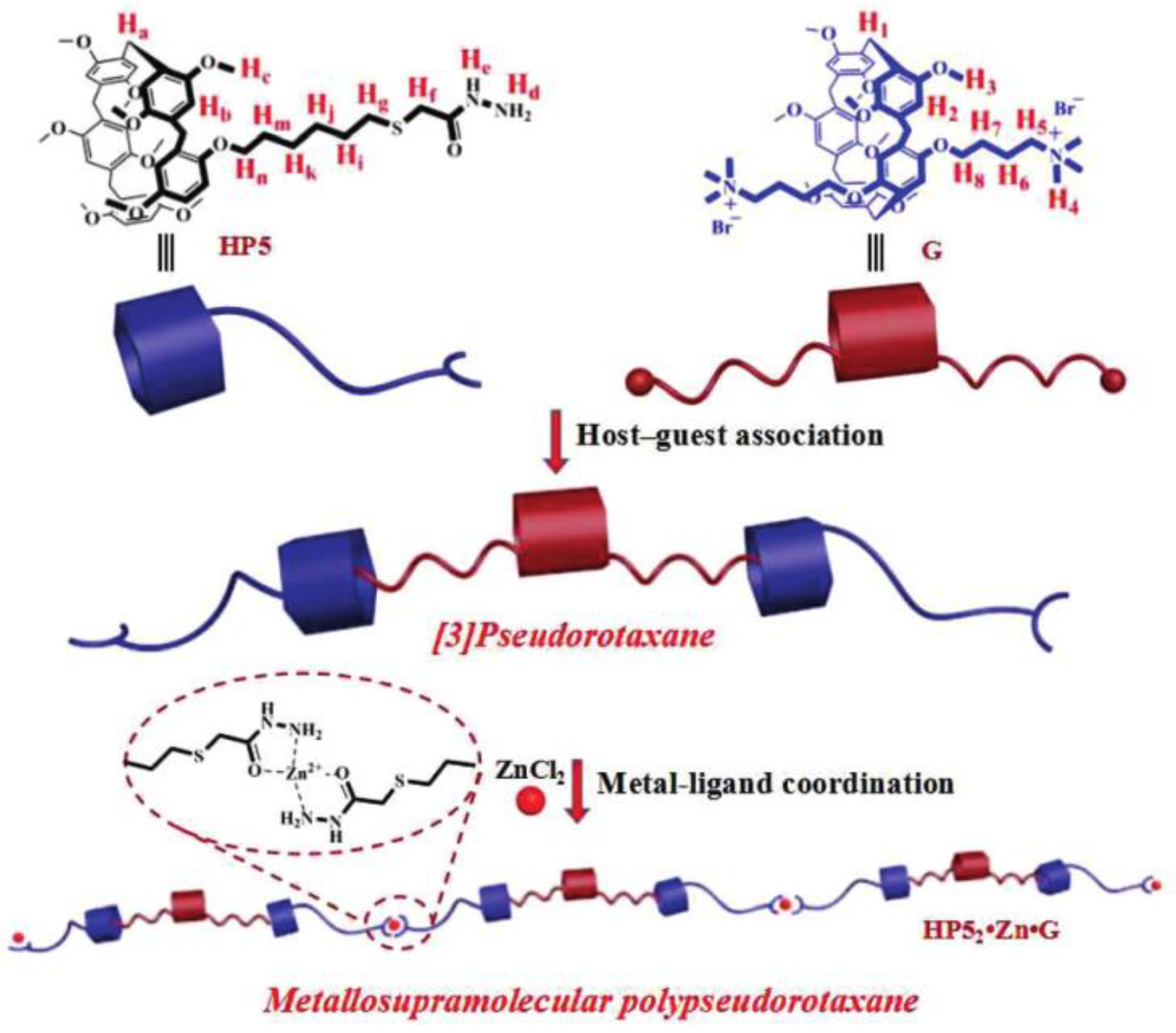

- Ding, J.D.; Chen, J.F.; Lin, Q.; Yao, H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wei, T.B. A multi-stimuli responsive metallosupramolecular polypseudorotaxane gel constructed by self-assembly of a pillar[5]arene-based pseudo[3]rotaxane via zinc ion coordination and its application for highly sensitive fluorescence recognition of metal ions. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 5370–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

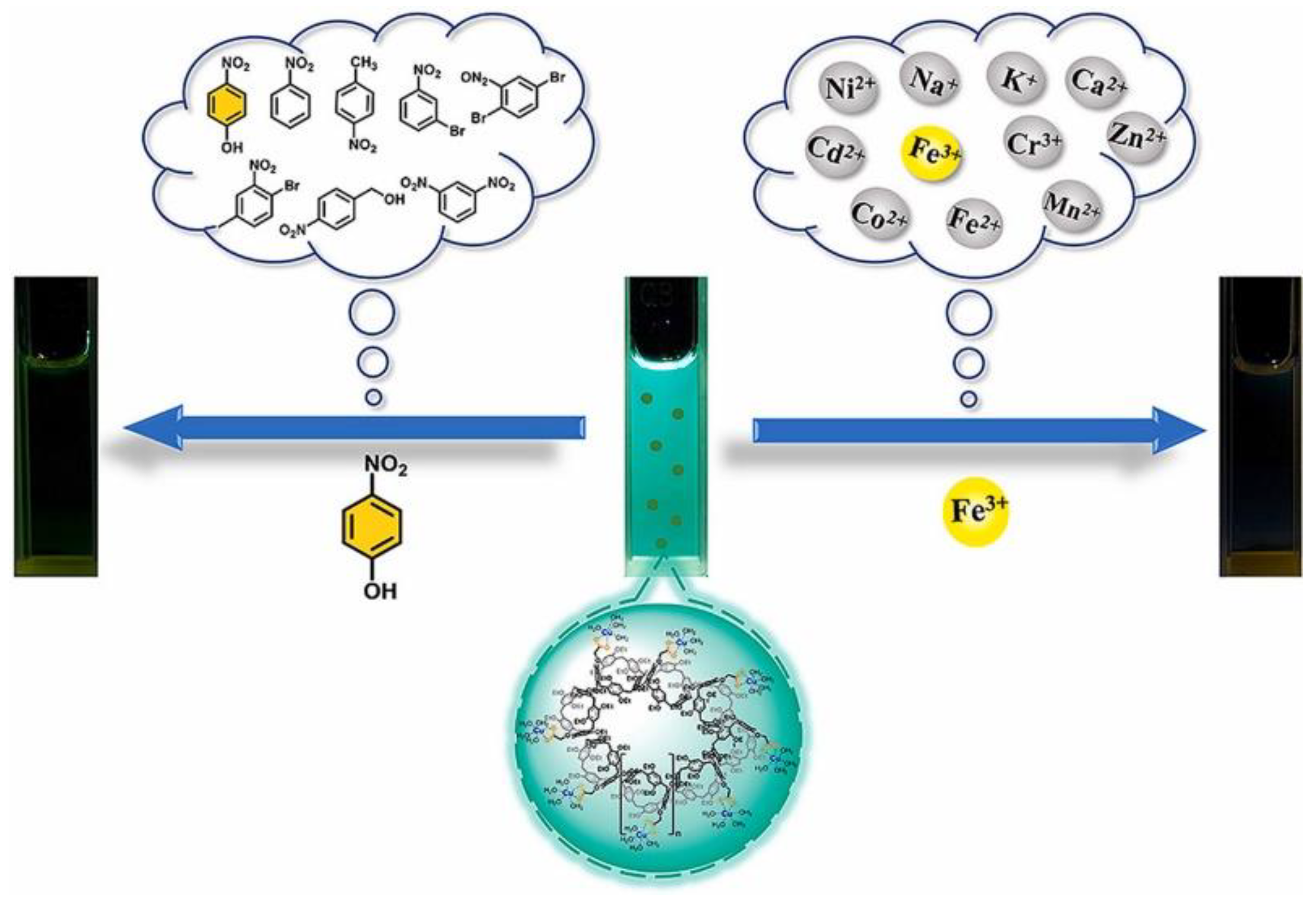

- Yu, D.; Deng, W.; Wei, X. Supramolecular aggregate of pillar[5]arene-based Cu(II) coordination complexes as a highly selective fluorescence sensor for nitroaromatics and metal ions. Dyes Pigment. 2023, 210, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todee, B.; Sanae, P.; Ruengsuk, A.; Janthakit, P.; Promarak, V.; Tantirungrotechai, J.; Sukwattanasinitt, M.; Limpanuparb, T.; Harding, D.J.; Bunchuay, T. Switchable metal-ion selectivity in sulfur-functionalised pillar[5]arenes and their host-guest complexes. Chem. Asian J. 2023, e202300913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; He, J.X.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.F.; Fang, H.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B.; Lin, Q. Novel pillar[5]arene-based supramolecular organic framework gel for ultrasensitive response Fe3+ and F− in water. Mat. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 100, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.M.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B.; Shi, B.; Lin, Q. Supramolecular AIE polymer-based rare earth metallogels for the selective detection and high efficiency removal of cyanide and perchlorate. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.W.; Ou, B.; Jiang, S.T.; Yin, G.Q.; Chen, L.J.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Yang, H.B. Cross-linked AIE supramolecular polymer gels with multiple stimuli-responsive behaviours constructed by hierarchical self-assembly. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.X.; Zhang, Y.M.; Hu, J.P.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, W.J.; Yao, H.; Wei, T.B.; Lin, Q. Novel fluorescent supramolecular polymer metallogel based on Al3+ coordinated cross-linking of quinoline functionalized-pillar[5]arene act as multi-stimuli-responsive materials. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.W. Stimuli-responsive fluorescent supramolecular polymer network based on a monofunctionalized leaning tower[6]arene. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 2299–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

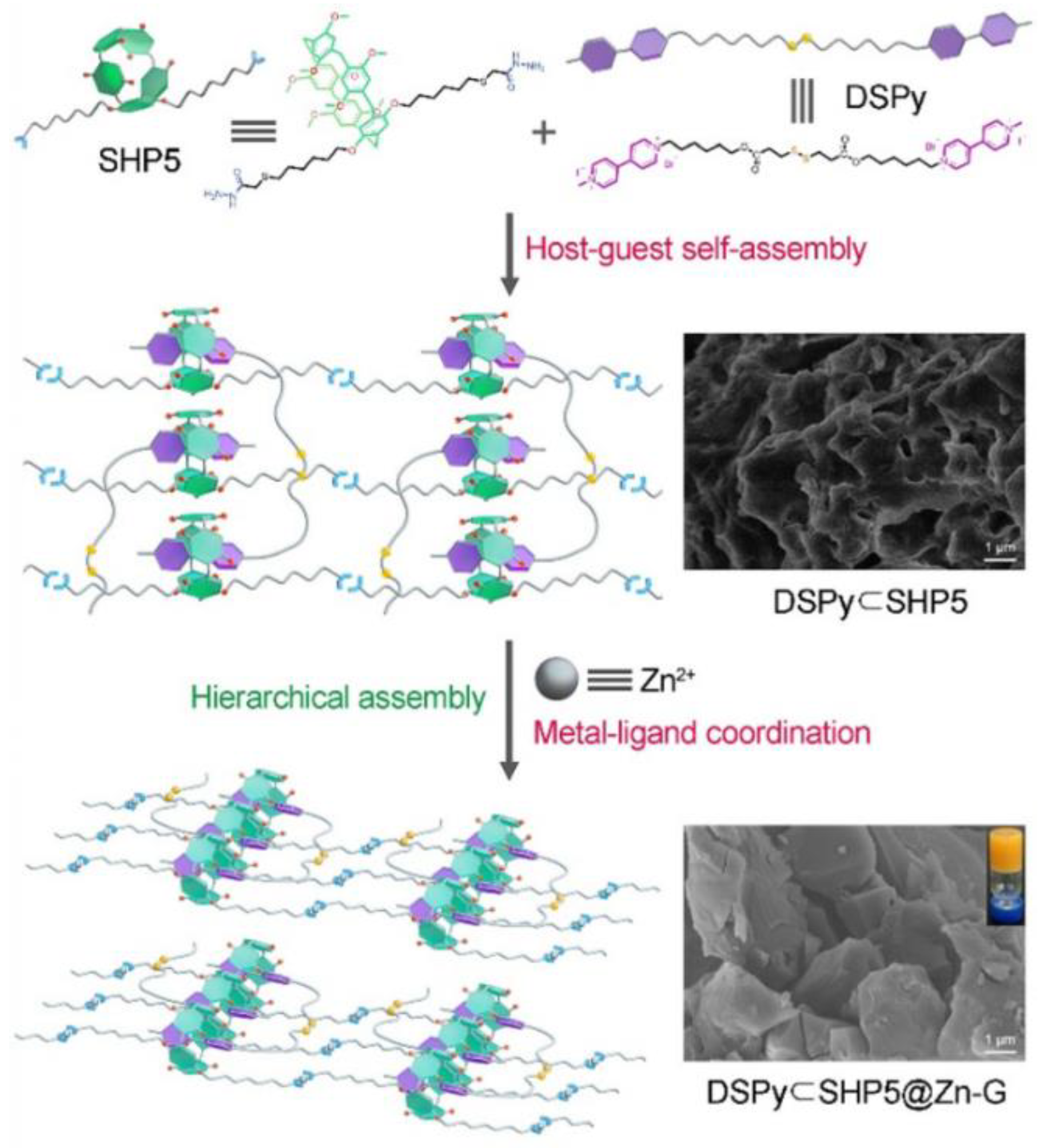

- Li, Y.F.; Guan, W.L.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Yang, Y.W. A multi-stimuli-responsive metallosupramolecular gel based on pillararene hierarchical assembly. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

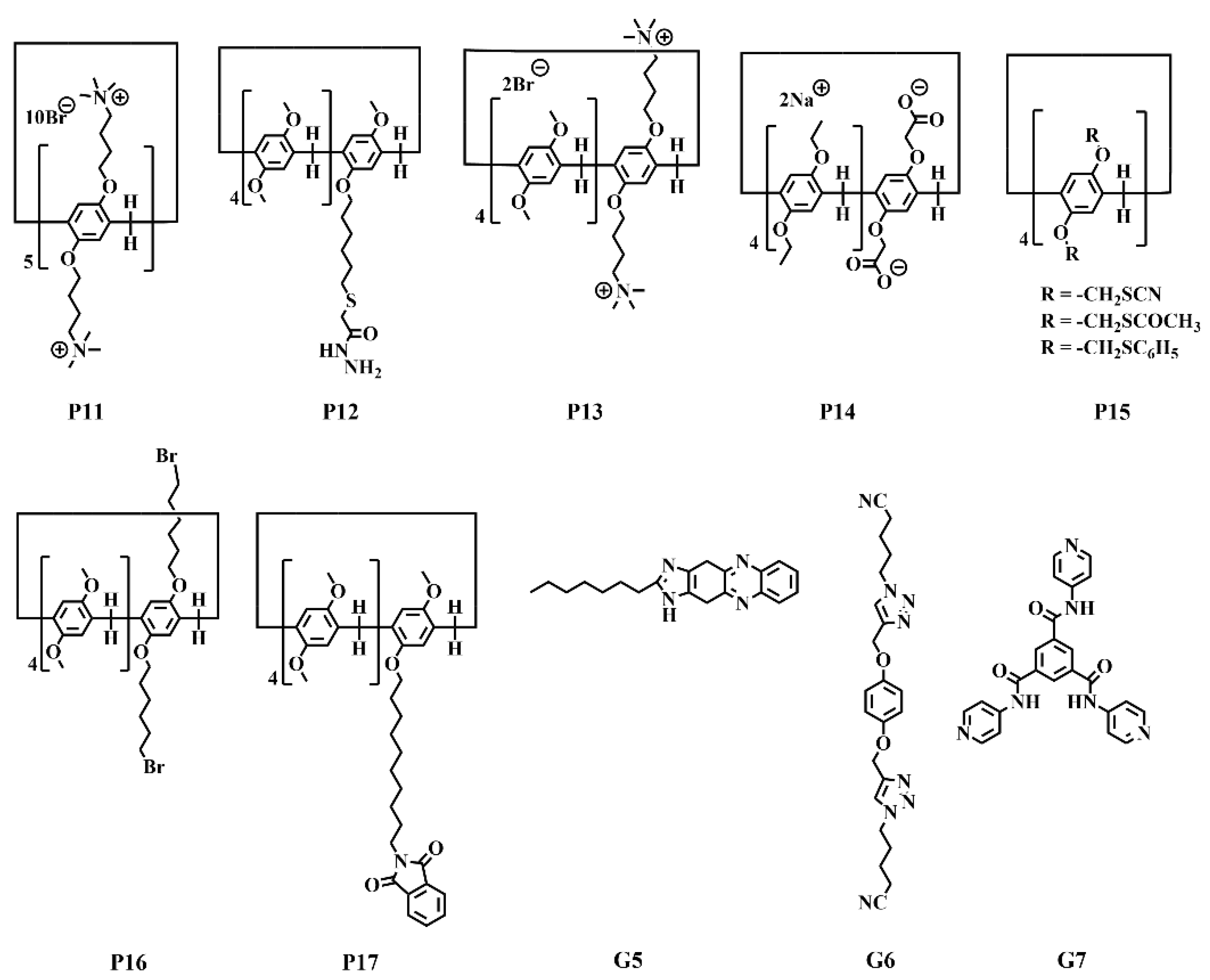

| Pillar[n]arenes | Guests | Coordinated metal ions |

Sensing properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P11 | G5 | Ag+, Hg2+ | Analyte: Ag+, Hg2+. Detection type: ratiometric/turn−on. λex/λem: 385/545 nm. LOD: 1.20 × 10−8 mol/L (Ag+); 5.00 × 10−7 mol/L (Hg+). Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 1/1. |

[48] |

| P12, P13 | P13 | Fe3+, Cu2+ | Analyte: Fe3+, Cu2+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 330/460−560 nm. LOD: 8.53 × 10−10 mol/L (Fe3+); 4.57 × 10−8 mol/L (Cu2+). |

[49] |

| P14 | − | Cu2+ | Analyte: nitroaromatics, Fe3+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 380/487 nm. LOD: 3.90 × 10−7 mol/L (Fe3+); 4.90 × 10−6 mol/L (nitroaromatics). Liner range: 0−1.20 × 10−3 mol/L (Fe3+); 0−1.80 × 10−4 mol/L (nitroaromatics). Solvent: DMF/H2O = 1/4. |

[50] |

| P15 | G6 | Cu2+, Hg2+ | Analyte: Cu2+, Hg2+. Detection type: turn−off. λex/λem: 293/324 nm. Solvent: CH3CN/water = 1/1. |

[51] |

| P2, P16 | P16 | Fe3+ | Analyte: Fe3+, F−. λex/λem: 290/470 nm. LOD: 1.02 × 10−10 mol/L (Fe3+); 9.79 × 10−9 mol/L (F−). Liner range: 0−1.18 eq. (Fe3+); 0−0.86 eq. (F−). Solvent: cyclohexanol/H2O = 3/17. |

[52] |

| P17 | G7 | Eu3+, Tb3+ | Analyte: cyanide, perchlorate. Detection type: turn−on. λex/λem: 290/470 nm. LOD: 5.96 × 10−8 mol/L (cyanide); 3.36 × 10−6 mol/L (perchlorate). Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 2/1. |

[53] |

| Pillar[n]arenes | Guests | Coordinated metal ions |

Sensing properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

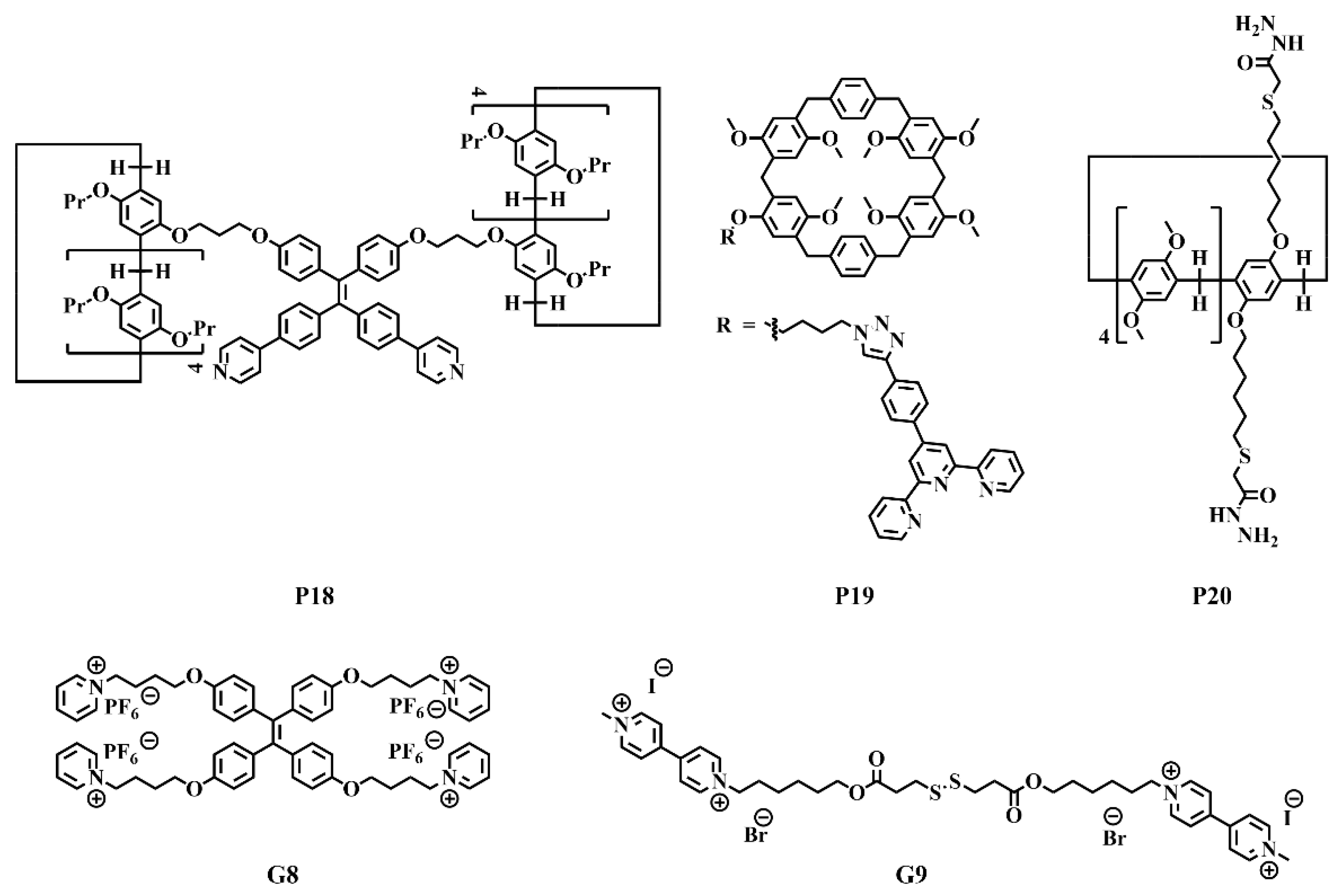

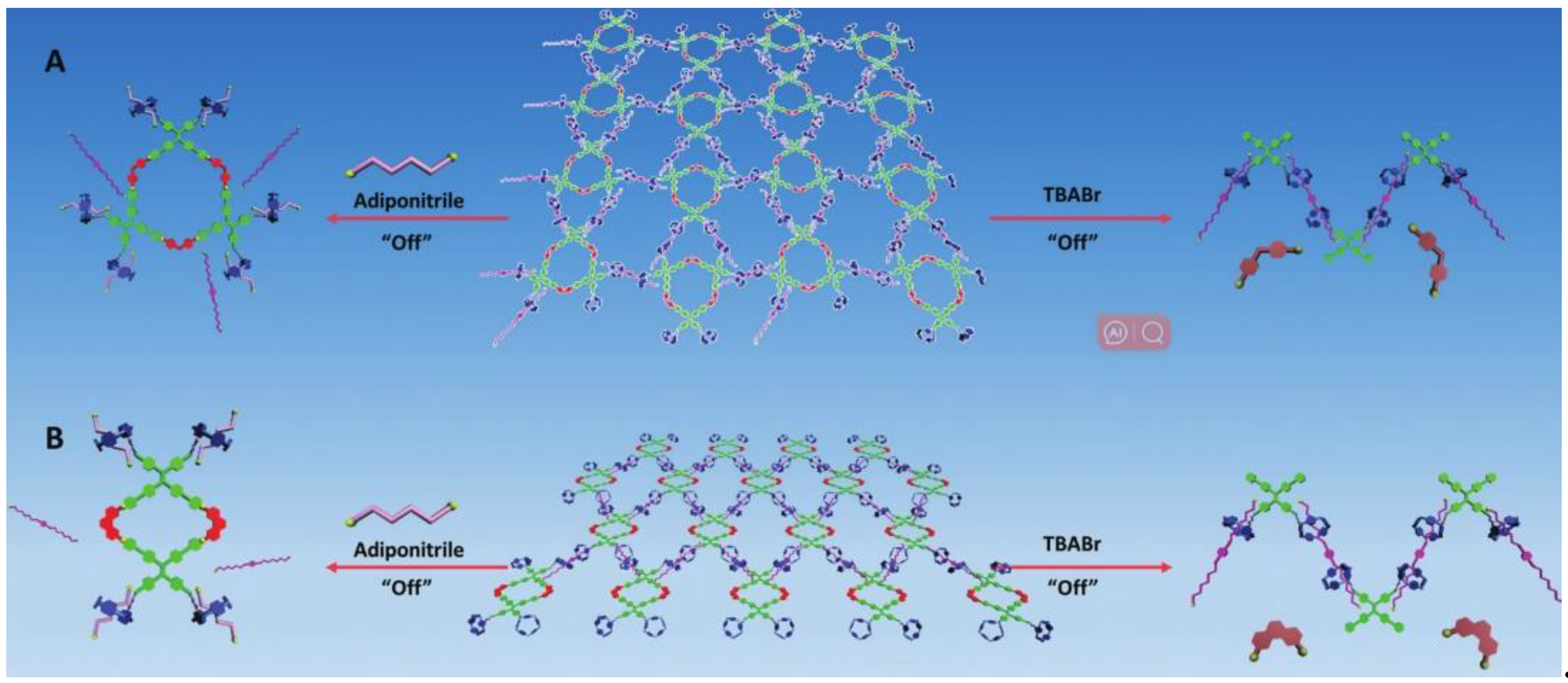

| P18 | − | Pt2+ | Analyte: temperature, competitive guest molecules, halides. λex/λem: 336/500 nm. Solvent: acetone/water = 1/19. |

[54] |

| P2 | − | Al3+ | Analyte: Fe3+, F−, trifluoroacetic acid, triethylamine. Detection type: turn−off/on. λex/λem: 380/ 470 nm. LOD: 4.39 × 10−9 mol/L (Fe3+); 2.75 × 10−8 mol/L (F−); 1.80 × 10−5 mol/L (trifluoroacetic acid); 1.80 × 10−5 mol/L (triethylamine). Solvent: DMSO/H2O = 4/1. |

[55] |

| P19 | G8 | Zn2+ | Analyte: competitive binding agents, trifluoroacetic acid, pillar[5]arene. λex/λem: 349/385 nm. Solvent: CHCl3/CH3CN = 4:1. |

[56] |

| P20 | G9 | Zn2+ | Analyte: thermal, redox, pH, competitive guests. λex/λem: 375/385 nm. Solvent: DMSO:H2O = 7/3. |

[57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).