1. Introduction

One of the present challenges in the field of water/wastewater treatment is represented by the development of low-cost advanced treatment methods able to degrade/remove hazardous, non-biodegradable pollutants.

Most conventional municipal wastewater treatment plants (MWWTPs) use activated sludge treatment as a secondary treatment step to remove organics, suspensions, and nutrients, but are inefficient at removing refractory contaminants such as pharmaceuticals and personal care compounds, endocrine disruptors, pesticides, additives, microplastics as well as their degradation intermediates [

1,

2]. Exposure to such organic compounds has been proven to negatively affect both human and living organisms. Even if complex organic compounds are hard to be degraded by conventional biological processes, advanced oxidation processes such as photo catalysis are capable of relatively easily degrading them. The photocatalytic process involves three main stages: photo generation of charge carriers; charge carriers diffusion to the catalyst surface and redox reactions on the catalyst surface. Moreover, if compared with other conventional wastewater treatment methods, such as coagulation – flocculation, ion exchange, or adsorption, presents the advantage of being environmentally friendly due to its mineralisation capability.

On the other hand, the most advanced MWWTP uses membrane-based processes as a tertiary treatment step to achieve outflow quality indicators suitable for reuse for various purposes [

3], but faces problems related to membrane fouling and related decrease of membrane operational life and increase of membrane cleaning operations and costs related to its replacement. Since organic compounds are important contributors to membrane fouling, advanced oxidation processes (heterogeneous photocatalysis included) have been investigated to improve the membrane’s separation performance and lifetime.

The coupling of membrane-based processes with heterogeneous photo catalysis (photocatalytic membrane reactors - PMRs) has proven to be an efficient and effective alternative for municipal wastewater treatment. Among the main two PMR configurations, the slurry-PMR system showed promising results compared to both PMR design with immobilized catalyst and other tertiary treatment processes such as chlorination, constructed wetlands, microalgae cultivation, ozonation, and photo-Fenton methods [

4].

Several authors have investigated the coupling of membrane filtration with photo catalysis to overcome issues related to membrane fouling and the need to remove some pollutants from the permeate water [

5,

6]. The advantages of heterogeneous photocatalysis among other advanced oxidation processes are represented mainly by good reaction rate and efficiencies. The most widely used photocatalyst is TiO

2 which is chosen for its chemical inertness, low cost, availability, non-toxicity, and recyclability. However, TiO

2 photocatalyst is inactive under visible light due to its wide band gap (3.2 eV), rapid recombination of holes / electrons pairs, and limited adsorption range in visible light (only about 4% of the solar spectrum). In this context, TiO

2 doping with metals is one of the most investigated and studied methods to improve TiO

2 photocatalytic activity and to ensure its adsorption spectrum shift towards the visible domain. This approach has been proven to be a useful tool for improving the visible light response of the catalyst and can be easily implemented by using the well-known sol-gel method.

The majority of investigated PMRs operate under UV irradiation [

7,

8], but there are research studies aimed at testing PMRs under visible light and/or simulated solar light as a sustainable method to solve environmental problems, of which the following are mentioned: photocatalytic membrane fouling control in wastewater treatment [

3]; degradation of various organic compounds using visible light driven photocatalytic membrane [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]; development of new visible light active photo catalysts for advanced degradation of refractory organic compounds from wastewater systems [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

In this context, the present work attempts to investigate the performance potential of a solar driven PMR with a suspended catalyst, using 1% wt. Fe-doped TiO2 photo catalyst and a polysulfone-based membrane, for the advanced treatment of municipal wastewater.

2. Materials and Methods

Iron-doped catalysts were synthesized by the sol-gel method (alkoxide route) using titanium isopropoxide (Sigma Aldrich) and FeCl

3 (Sigma Aldrich). Ethanol (Chimreactiv) was used as a solvent. Titanium isopropoxide was dissolved in ethanol at room temperature under continuous stirring and then a mixture of ultrapure water and ethanol was added to perform the hydrolysis step. Afterward, the solution of FeCl

3 in ethanol was added dropwise (in small portions under vigorous stirring). Resulted solutions were maintained under vigorous stirring for 3 hours at room temperature. The resulting sols were converted into gels by drying at 80

0C for 24 hours [

23,

24] and then thermally treated at 300

0C (catalyst sample FT1) and 400

0C (catalyst sample FT2) for 2 hours. Titanium dioxide anatase form (Merck) was used as a reference for the assessment of prepared catalyst photocatalytic activity.

The polysulfone-based membrane was prepared via phase inversion process, immersion precipitation techniques using: polysulfone (Psf) M

w = 35000 g/mol (Sigma Aldrich) as the base polymer, and 1-methyl- 2-pyrrolidone (NMP), purity >99.5% (Merck), as solvent. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) K30 (40000 g/mol) (Fluka) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400, M=3500-4000 g/mol (Scharlau), were used as additives [

25]. Ultrapure water was obtained utilizing a Milli – Q Integral 15, Merck, Millipore equipment and used as a non-solvent in the coagulation bath. Ethanol 96% purity (Chimreactiv) and glycerine 99.5% (Chempur) were selected for post-treatment and conditioning of the membranes. The membrane was obtained as follows: Psf and additives were dissolved in NMP under continuous stirring (at room temperature, for 24 h); the polymeric solution was cast on a flat glass sheet using a “doctor blade“ device with a 300 µm slot (speed 1m/min); casted membrane was immersed within ultrapure water coagulation bath (for 5 minutes); resulted membrane was repeatedly washed with ultrapure water and was subject to conditioning (using a 10% ethanol solution); membranes were stored in 10% glycerine solution and before use were immersed for 2h in a 10 % ethanol solutions and repeatedly washed with ultrapure water.

An FEI Quanta FEG 250 scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fischer) was used for morphological characterization and EDX (energy dispersive X–ray spectroscopy) analyses. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) technique was applied for microstructural analysis of the catalyst samples. The studied samples were ground to powder form and then placed in the standard quartz trays of the diffractometer. Data acquisition was performed with the Ultima IV diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) using monochromatized Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å) from a fixed anode X-ray tube operated at a voltage of 40 kV, and a current of 30 mA, respectively. Diffractograms were recorded for the angular 2-theta range of 10 – 90 degrees, in Bragg-Brentano geometry, in continuous scan mode, at a speed of 1 degree/minute, with a step width of 0.02 degrees. The crystal microstructure analysis was performed using the functionalities of the PDXL software version 2.2. and ICDD database PDF4+ version 2022.

A led driven lamp with 35W power consumption, 380-800 nm wavelength, and 1000 lumens luminous flow was used to simulate solar radiation. Provided light irradiance (µmol quanta/m2 s) was measured with a full spectrum meter Apogee MQ 500 (Apogee instruments). The tests were performed during the winter period, with a mean daylight irradiance below 500 µmol/m2/s. In the case of photo-degradation tests carried out under simulated solar light, the light irradiance was adjusted to match the intensity of natural daylight.

A custom-made installation was operated for the photocatalytic degradation tests. The installation (presented in

Figure 1) consists of the following main elements:

Four transparent PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) tubes with an outer diameter of 16 mm, an inner diameter of 12 mm, and a length of 1 m;

Submerged feed/recirculation pump (with the possibility to adjust the flow). A constant recirculation flow of approximately 1 L/min was used during degradation tests;

Portable aeration pump with a flow of 1 L/min. Aeration was operated using a 30-minutes ON/30-minutes OFF algorithm;

Feed/recirculation vessel with a capacity of 2 L.

The membrane separation step was performed using a KMS Laboratory Cell – CF2 system (Koch Membrane Systems) operating in tangential flow at a working pressure of 2.5 bars. The membrane module presents the following main characteristics: maximum operating volume – 600 mL; minimum operating volume – 50 mL; effective membrane surface: 28 cm2; maximum operation pressure (without nitrogen pressurisation) – 6 bars.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Photocatalyst Synthesis Characterization

3.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

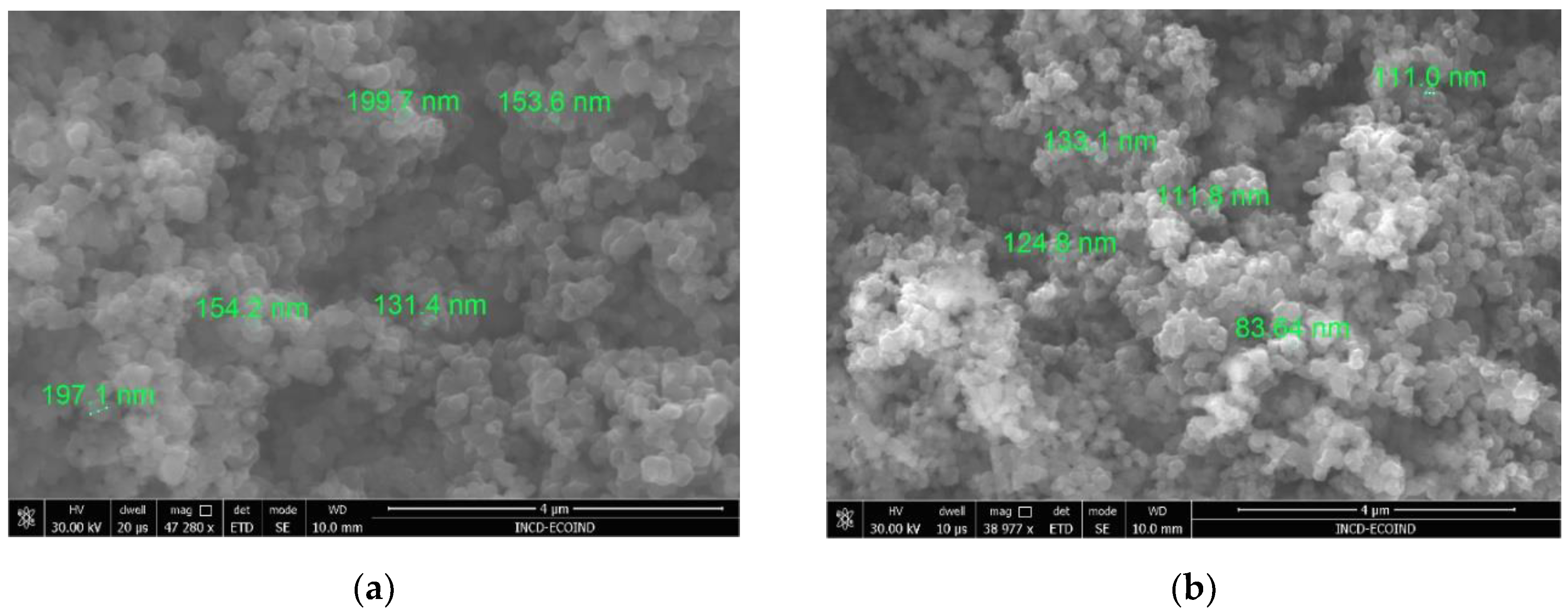

Morphological analyses of the catalyst powders revealed that the FT1 catalyst presents dimensions varying from 130-200 nm and FT2 particles dimensions are in the range of 80-130 nm (see

Figure 2). These results are in agreement with the outcomes of other studies, which have shown that increasing the thermal treatment temperature results in smaller particle dimensions [

26].

3.1.2. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX)

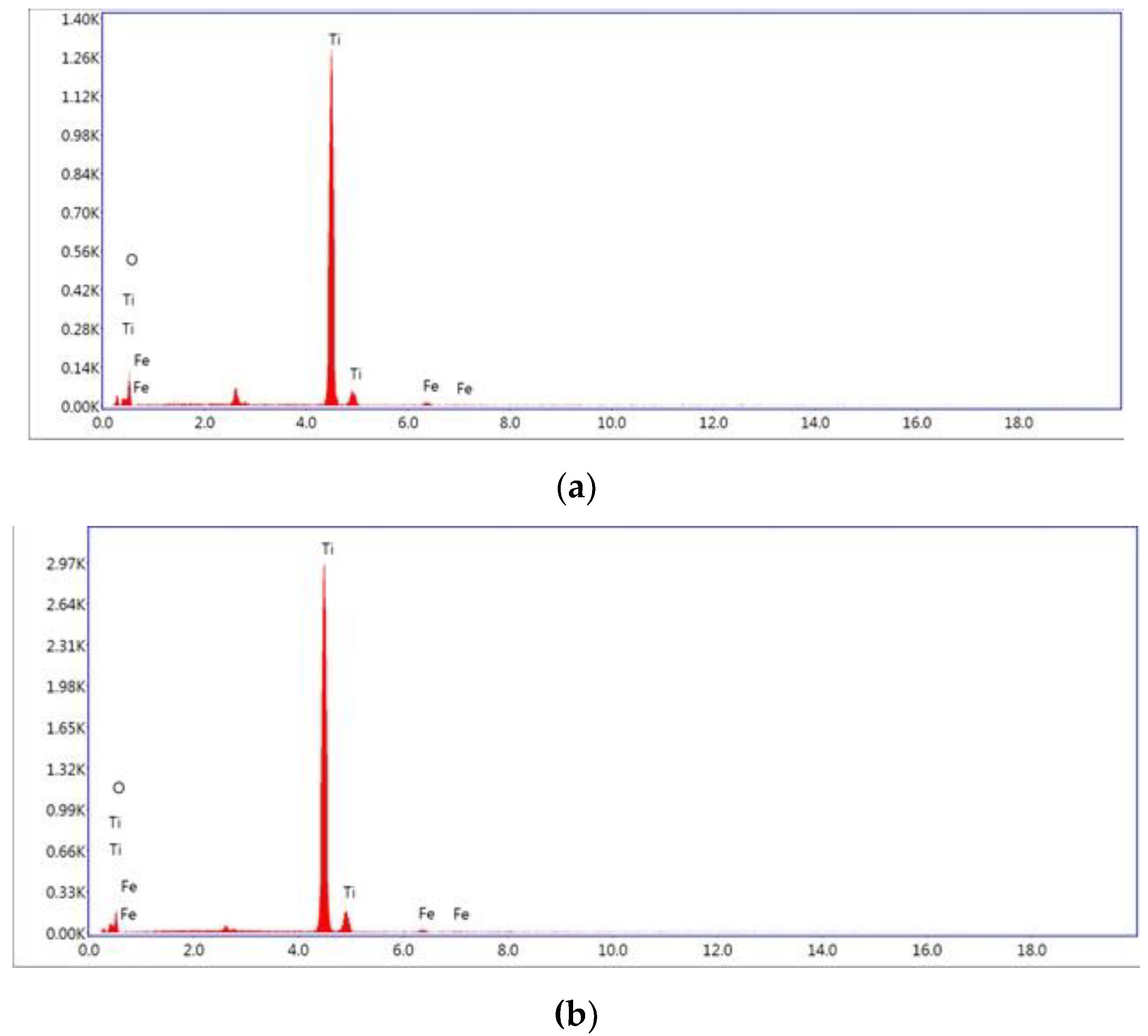

EDX analysis confirmed the presence of Fe within the catalyst structure (see

Figure 3) with a weight percentage of about 1% compared to TiO

2 (see

Table 1). The atomic percentages also confirm the Ti/O ratio of about 1 to 2 (see

Table 1).

3.1.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The raw data from the XRD scans were transferred to PDXL software for Rietveld analysis. This method refines the crystal structure parameters by fitting a calculated pattern obtained from lattice parameters, crystal system, atomic coordinates, etc. to a measured diffraction pattern using the least squares method. Crystal models were built using information from ICDD, 00-064-0863 (TiO2 – anatase), and 01-079-6031 (TiO2 – rutile).

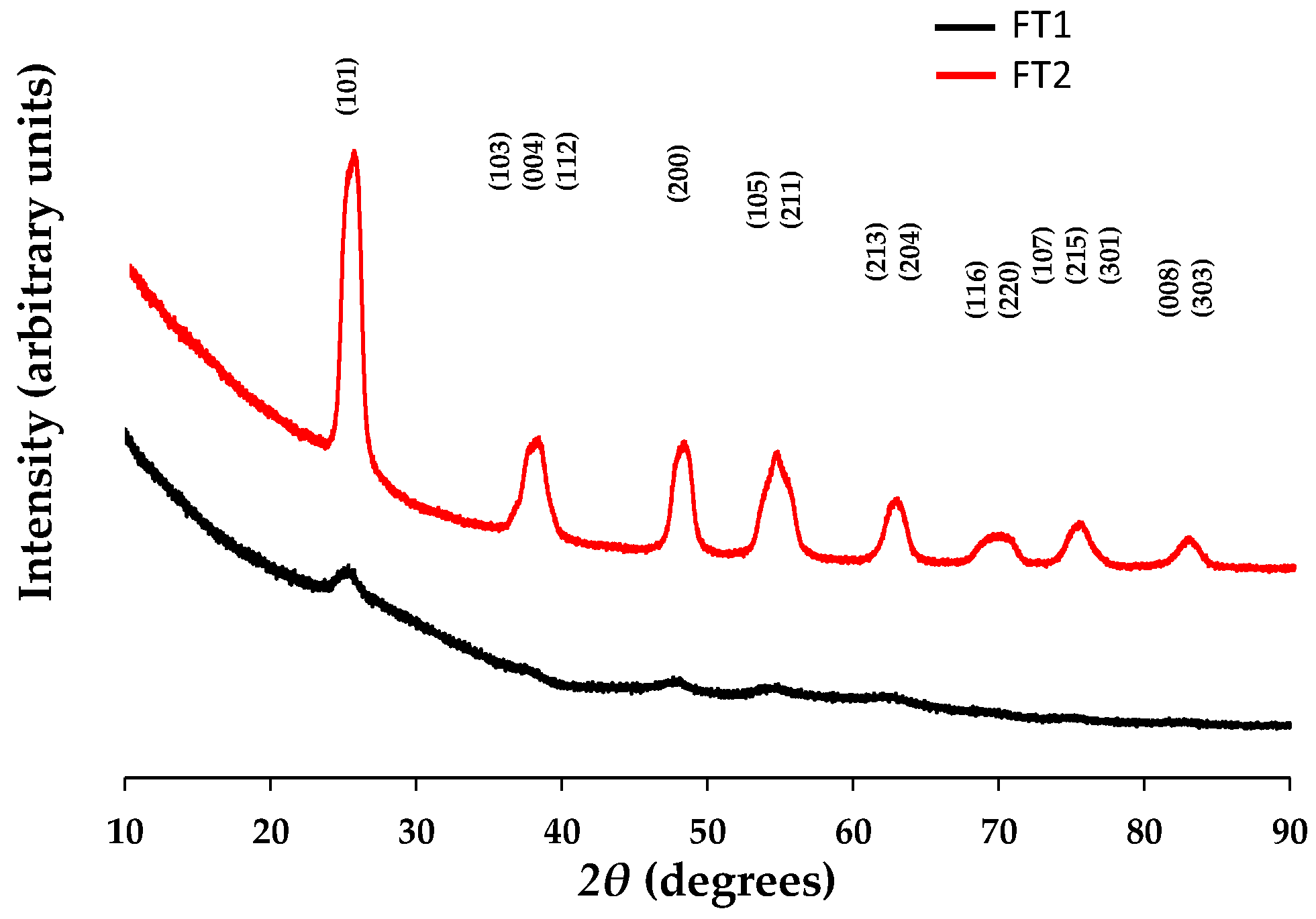

According to the shape of the X-ray patterns (see

Figure 4) recorded for the catalyst, it can be observed that the sample thermally treated at 300 °C seems to develop an XRD amorphous structure. Samples with the same composition but annealed at 400 °C show a clear crystalline structure, where the characteristic peaks of TiO

2 anatase can be clearly noticed at two-theta values around 25, 38, 48, 54, 63, 69, 75, and 82 degrees.

Table 2 presents the microstructural data recorded as resulted from the XRD analysis of the prepared catalysts.

The XRD analysis showed that the registered diffraction peaks were assigned to the tetragonal anatase phase of titanium dioxide with the space group indicated in

Table 2. This can be considered, on the one hand, as a confirmation of the TiO

2-anatase crystalline phase in all the synthesized samples and, on the other hand, as a confirmation that, despite some microstructural changes (

i.e., D-spacings), the structure of the anatase titanium dioxide in the studied catalysts holds at both temperatures. Experiments showed a decrease in FWHM values with the rise of the synthesis temperature for all three peaks analyzed. For instance, the FWHM value decreases from 7.41 degrees at 300 °C to 1.401 at 400 °C for the (200) peak (at 2θ of 48°), or from 5.23 degrees at 300 C to 1.78 at 400 C for the (004) peak. The peaks broadening correlate with crystallite dimensions lower than 1000 Å,

Depending on the desired properties of the synthesized materials (i.e., catalytic activity, efficiency, etc.), this experimental finding may lead to the conclusion that the choice of thermal treatment temperature is essential to achieve the aimed functionalities. Thus, higher temperatures may result in better organized microstructures, while lower temperatures may lead to materials with various defects (dislocations, vacancies, interstitials, substitutionals, or others). It is worth mentioning that for crystallites smaller than 30 Å, the X-ray diffraction peaks become so broad and low, that they are indistinguishable. However, from the perspective of ensuring good contact of the catalyst with the reaction environment, smaller particle dimensions offer a higher contact surface, and thus synthesis at lower temperatures may be an advantage for the doped-TiO2 compositions studied in the present research. Implicitly, the synthesis procedures may be closer to green chemistry principles.

On the other hand, when looking in

Table 2 at the crystallite size as evaluated with the Williams Hall method (whole XRD patterns), it can be observed that average crystallite size values for samples synthetized at 400 °C are higher than for the same situation at 300 °C. An important notice is that crystallite sizes of Fe-doped TiO

2 were found to be lower than the commercial TiO

2 catalysts, used as reference material. However, these results are in contradiction with those obtained by scanning electronic microscopy, a possible explanation being that Fe-doped TiO

2 particles treated at lower temperatures (300 °C) tend to agglomerate more than those treated at higher temperatures (400 °C).

3.2. Experimental Photo-Degradation Tests

Photo catalytic activity of prepared photo catalysts has been evaluated using both natural and simulated solar light and has been expressed as COD removal efficiency. The presence of iron dopant assures enhancement of titanium dioxide photo catalytic activity.

Experimental tests were performed using real wastewater from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. For all tests, the irradiation period was kept constant at 7 hours (from 9 AM to 4 PM).

For the photocatalytic step, our results can be described by a first-order kinetic (equation 1) that can be linearized according to the equation 2:

Where: [COD]0 = wastewater sample initial COD; [COD] = wastewater sample COD at a given time; k = apparent kinetic rate constant of the first order reaction model; t = reaction (irradiation time)

For the membrane process, the ultrapure water and separation flows were calculated using the following formula:

Where: J = ultrapure water flow or separation flow; V = volume of ultrapure water or wastewater sample passing through the membrane; S = effective membrane area (in this particular case = 28 cm2); T = time in which V volume was collected

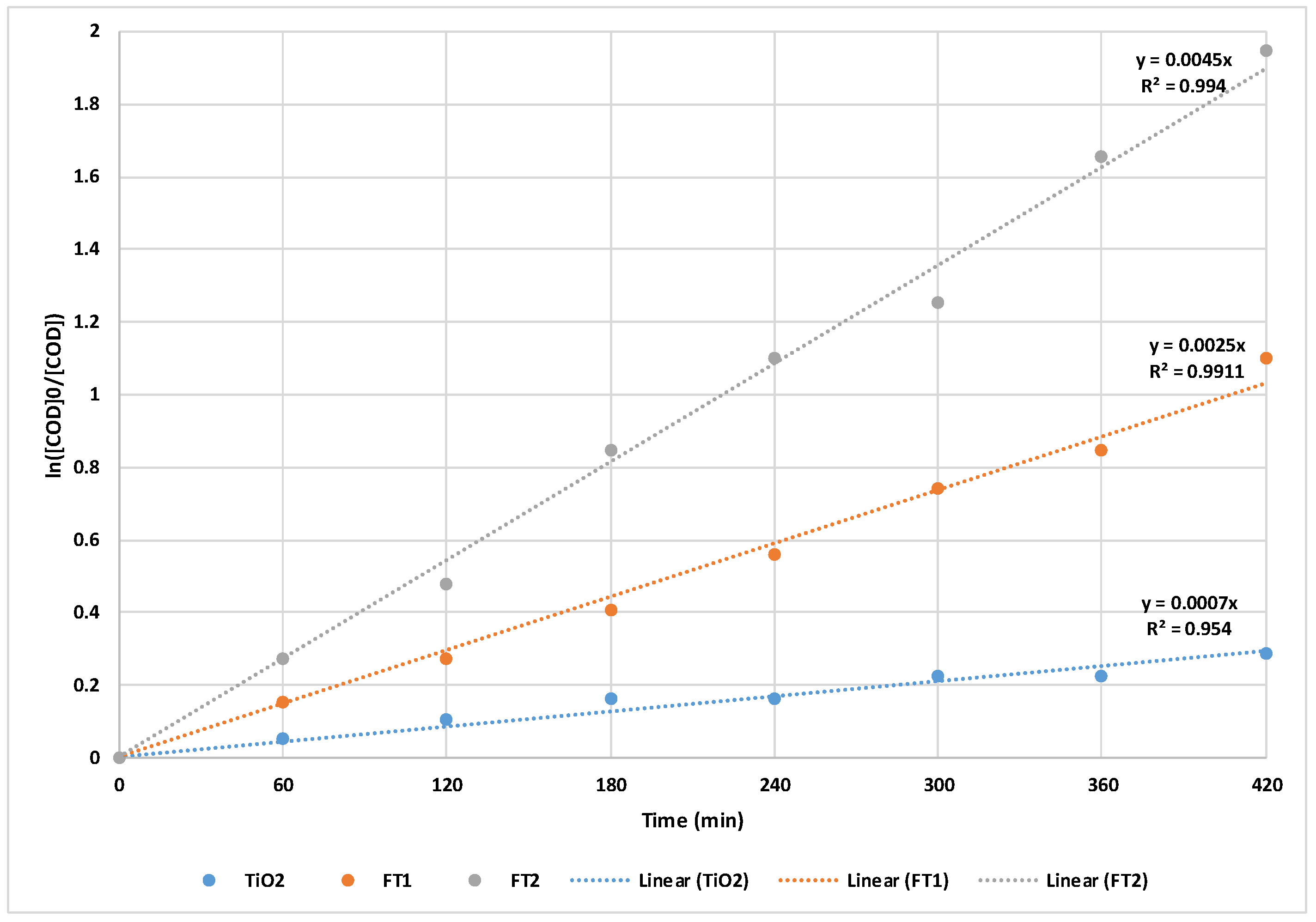

3.2.1. Experimental Photo-Degradation Tests Using Simulated Solar Light

The experiments were carried out over 7 hours. Samples were analysed at 1-hour intervals and the COD value of the outflow was recorded. Experiments were also performed using commercial TiO

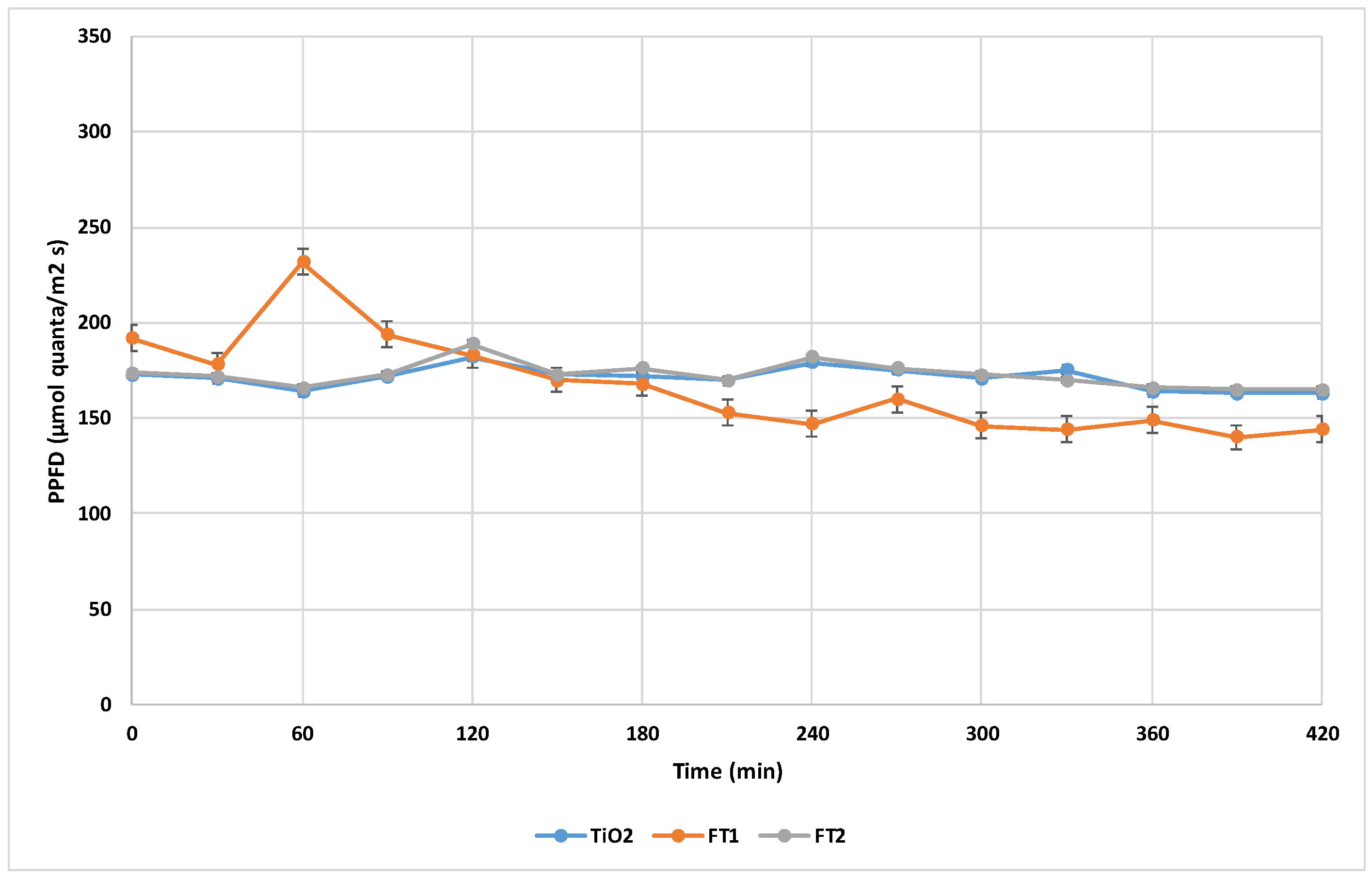

2 anatase form as a reference for comparison with iron doped catalysts. The initial catalyst concentration was kept constant at 100 mg/L for all degradation tests. PPFD (Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density) was monitored at half-hour intervals (presented in

Figure 5). The COD initial concentration varied between 176-184.8 mg O2/L.

The iron doped catalyst thermally treated at 400

0C – FT2 proved to achieve the highest COD removal efficiency (85.71%) after 7 hours of irradiation compared to the FT1 sample (annealed at 300

0C) which attained a COD removal efficiency of 66.67% (see

Table 3). Both synthesized doped catalysts exhibit higher efficiencies compared to commercial TiO

2, for which a COD removal efficiency of only 25.00% was reached, after 7h of irradiation. The results are in good correlation with previous research on the degradation of organic compounds using Fe-doped TiO

2 catalysts [

25].

This fact is also supported by the linearized pseudo-first order kinetic equations concerning COD removal (presented in

Figure 6). The pseudo-first order rate constants for the simulated sunlight experiments were calculated from the slope of the linear plots (under equations 1 and 2) and varied in the following order: k

FT2 = 7.50 x 10

-5 s

-1 > k

FT1 = 4.17 x 10

-5 s

-1 > k

TiO2 = 1.17 x 10

-5 s

-1.

It can be observed that both the apparent rate constant and degradation efficiency increase with the increase of annealing temperature from 300 to 400 C. That behavior can be explained by the increase of crystallite size with temperature which results in more active sites available for degradation.

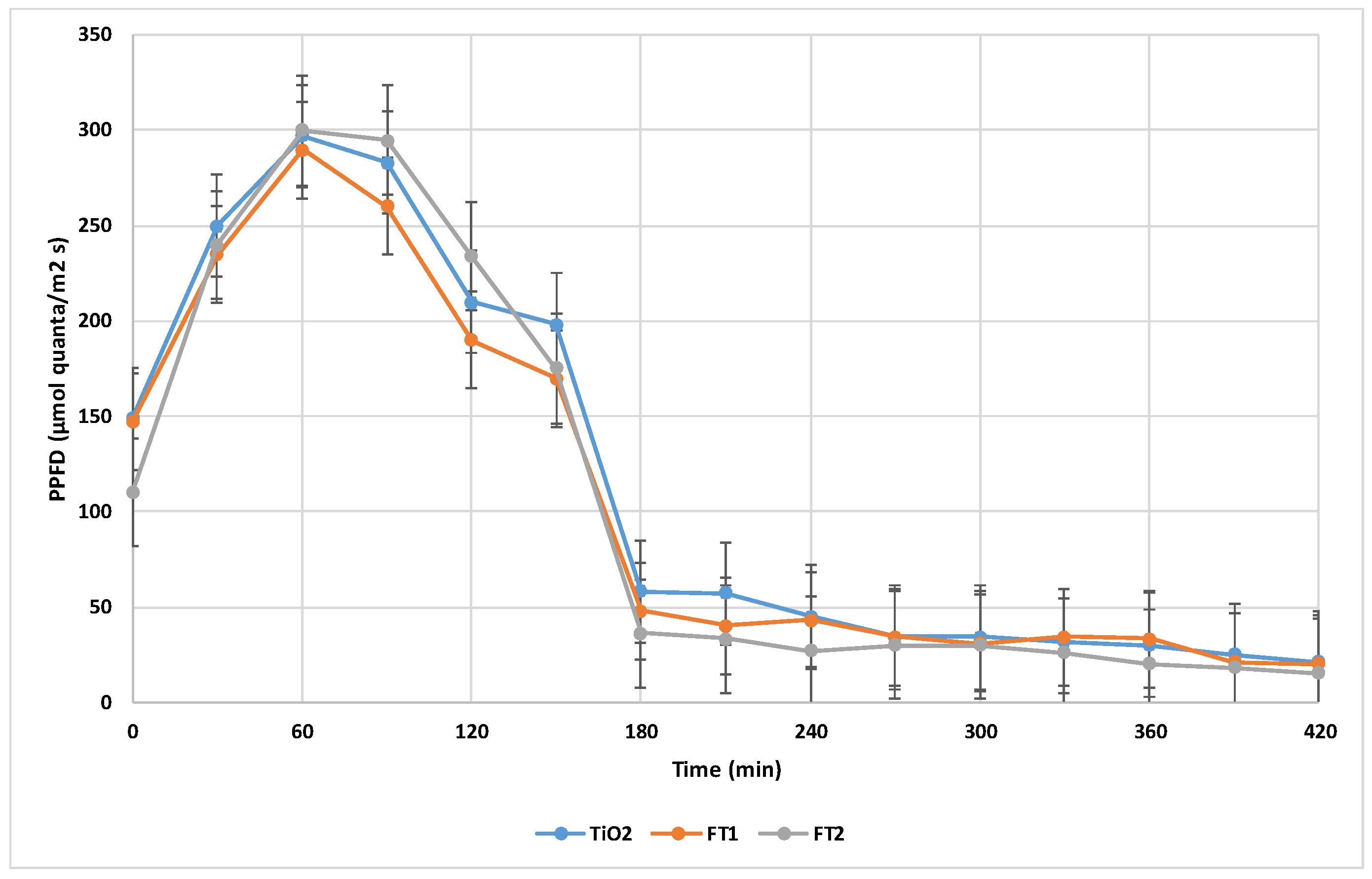

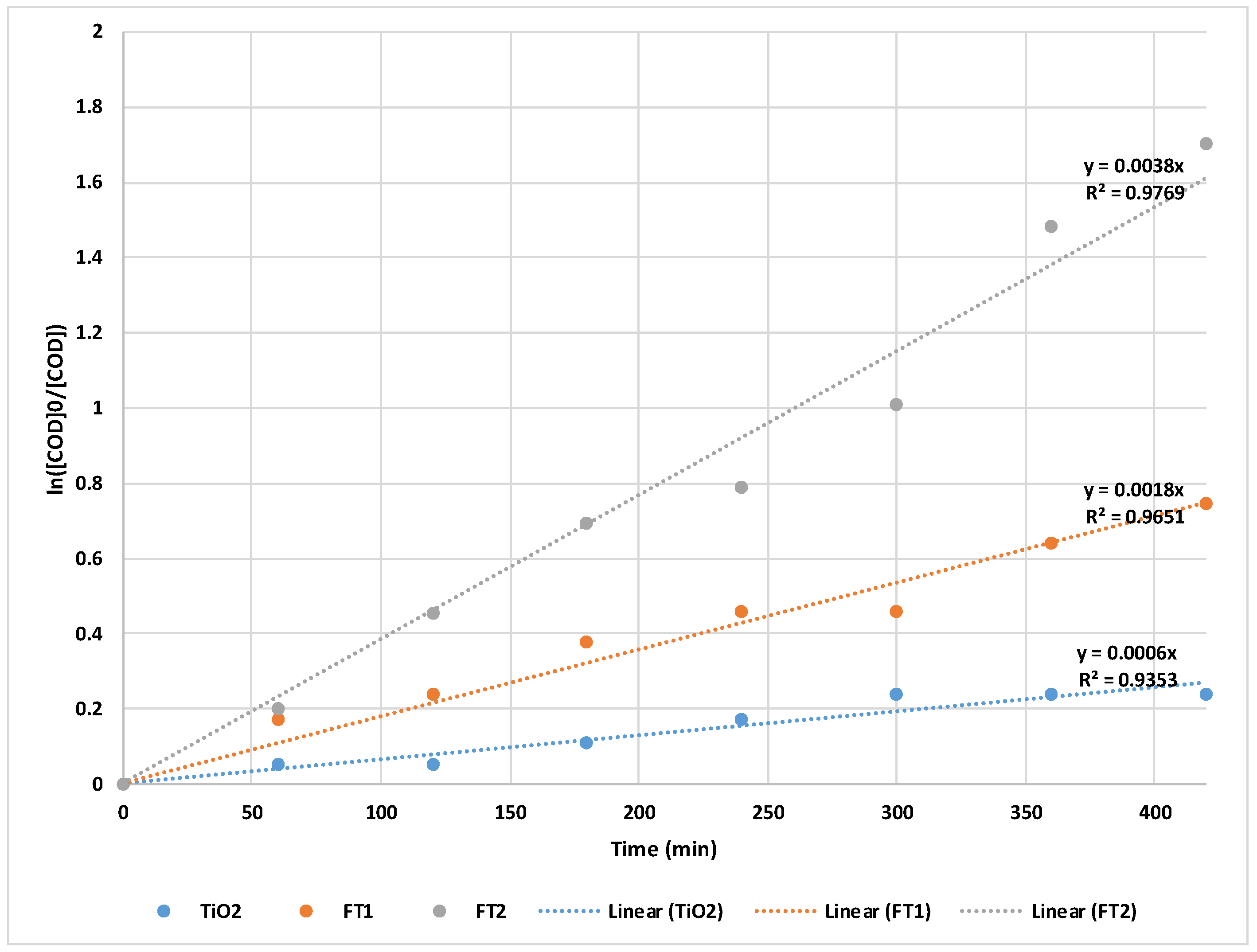

3.2.1. Experimental Photo-Degradation Tests Using Natural Solar Light

The experimental degradation tests were performed under the same conditions as for simulated sunlight. Because experiments were performed in winter, the recorded PPFD varied widely during the 7-hour test period (see

Figure 7). However, the profile of PPFD vs. daytime presented a similar pattern for all degradation tests. Initial COD concentration varied in the domain 167.2 – 193.6 mg O2/L.

The best COD removal efficiency was also achieved by the FT2 catalyst with a value of 81.82% after 7 hours of irradiation (close to that obtained using simulated solar light). The FT1 catalyst led to a COD removal efficiency of up to 52.63%, (see

Table 4) while the use of commercial TiO

2 resulted in a COD removal efficiency of only 21.05%. Linearized pseudo-first order kinetic equations (following equations 1 and 2) also supported the fact that FT2 proved to be more efficient for COD removal compared to FT1 and TiO

2 (presented in

Figure 8).

The pseudo-first order rate constants for the natural solar light experiments were calculated from the slope of the linear plots and were found to vary in the following order: kFT2 = 6.33 x 10-5 s-1 > kFT1 = 3.00 x 10-5 s-1 > kTiO2 = 1.00 x 10-5 s-1. Similar to the experiments using simulated solar light, both apparent rate constant and degradation efficiency increase with the increase of annealing temperature from 300 °C to 400 °C.

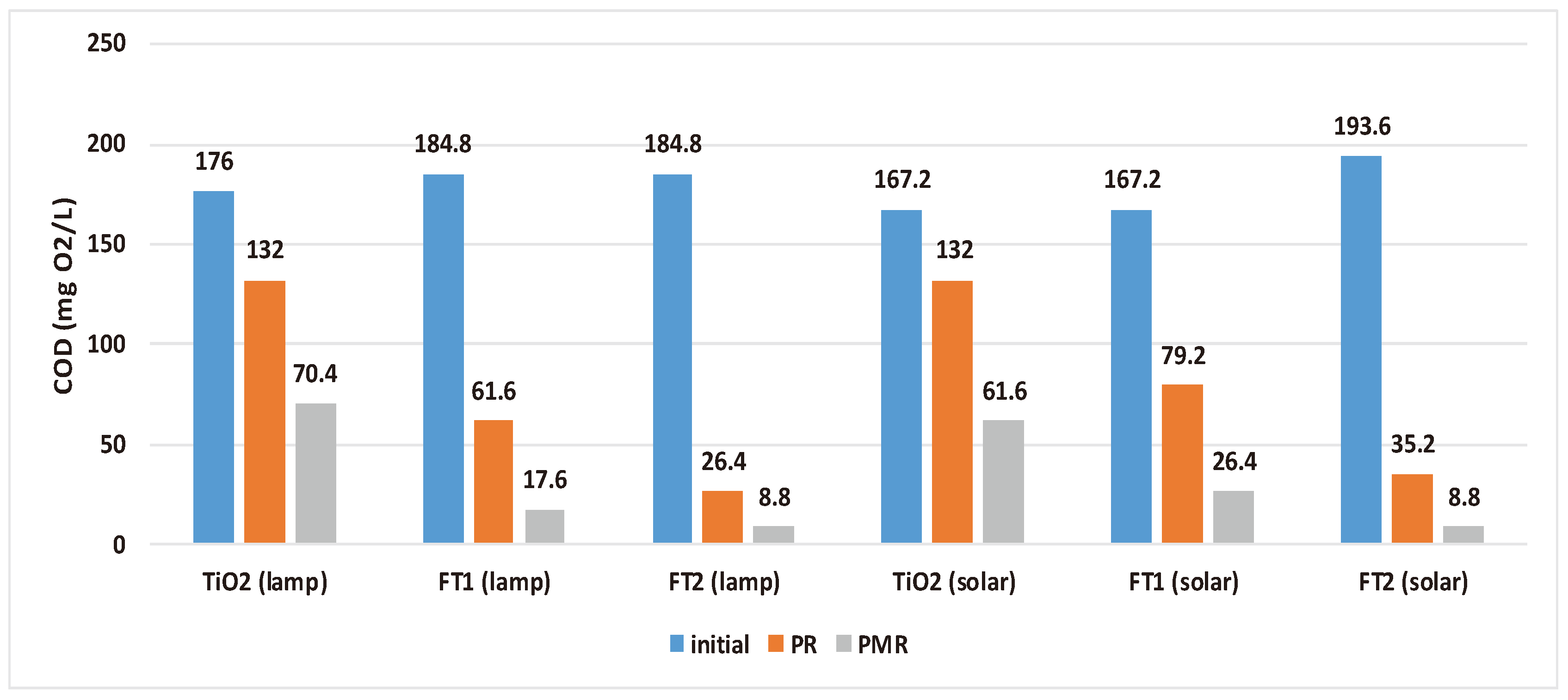

3.3. Overall COD Removal Efficiency of Solar PMR

The polymeric membrane was obtained starting from a 10% polysulfone (Psf) solution and was used in all separation experiments. The working pressure was maintained at 2.5 bar. All outflow volume resulting from the photocatalytic step was subject to a membrane separation process at a concentration ratio of 1 to 2. Experimental results from the membrane separation step revealed that the membrane also acted as a barrier to organic compounds with overall COD removal efficiency reaching 95.24% (for simulated solar light PMR) and 95.45% (for solar driven PMR) compared to 85.71% and 81.82%, respectively when only the photocatalytic step was used. As expected, the best results were obtained for wastewater treated with FT2 catalyst (residual COD = 8.8 mg O

2/L). The FT1 catalyst also exhibited good results in terms of COD removal reaching efficiencies of 90.48% (for simulated solar light) and 84.21% (for solar driven PMR) (see

Table 5). The use of commercial TiO

2 resulted in overall PMR COD removal efficiencies situated in the range of 60-64% (see

Figure 9).

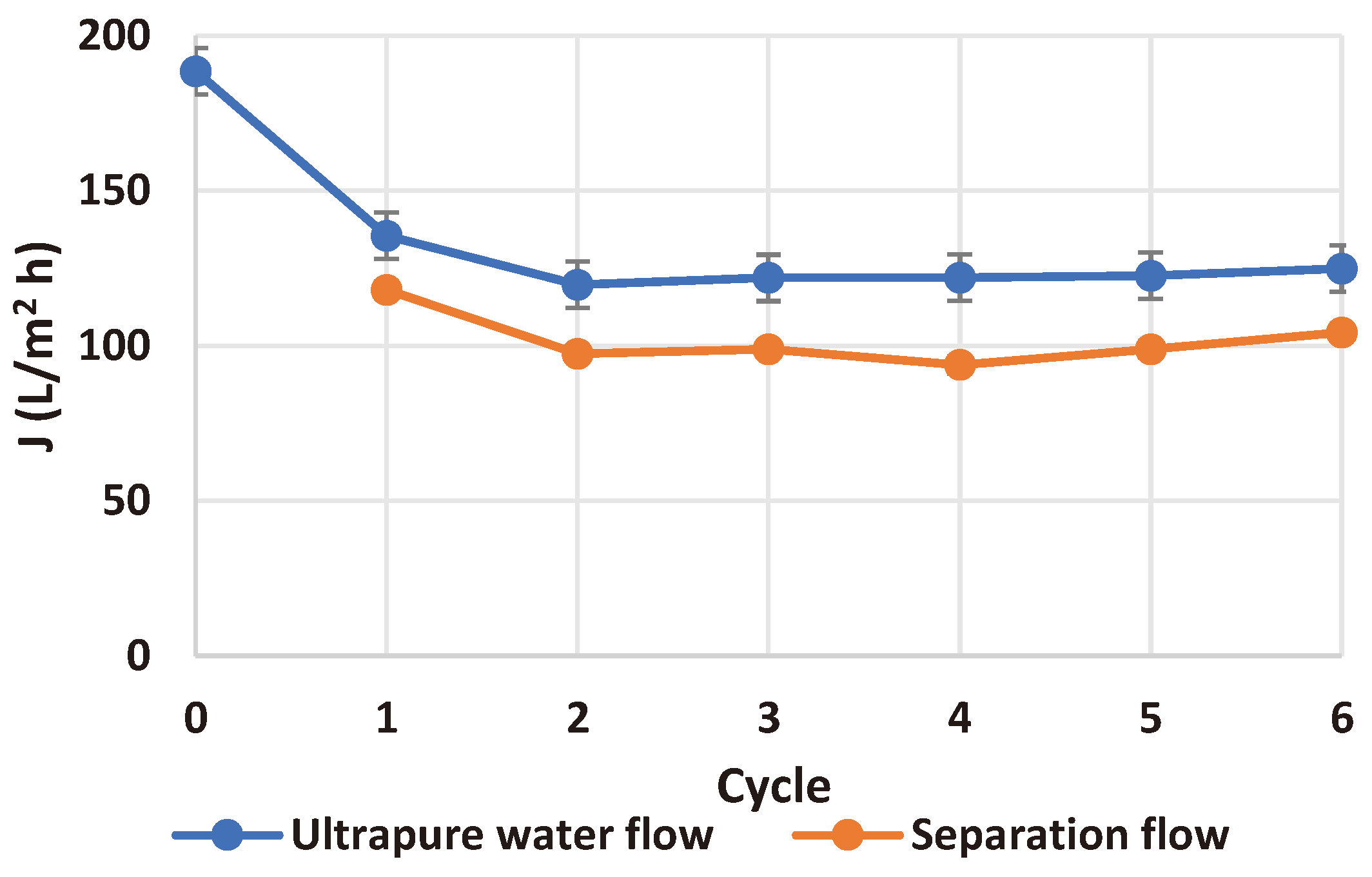

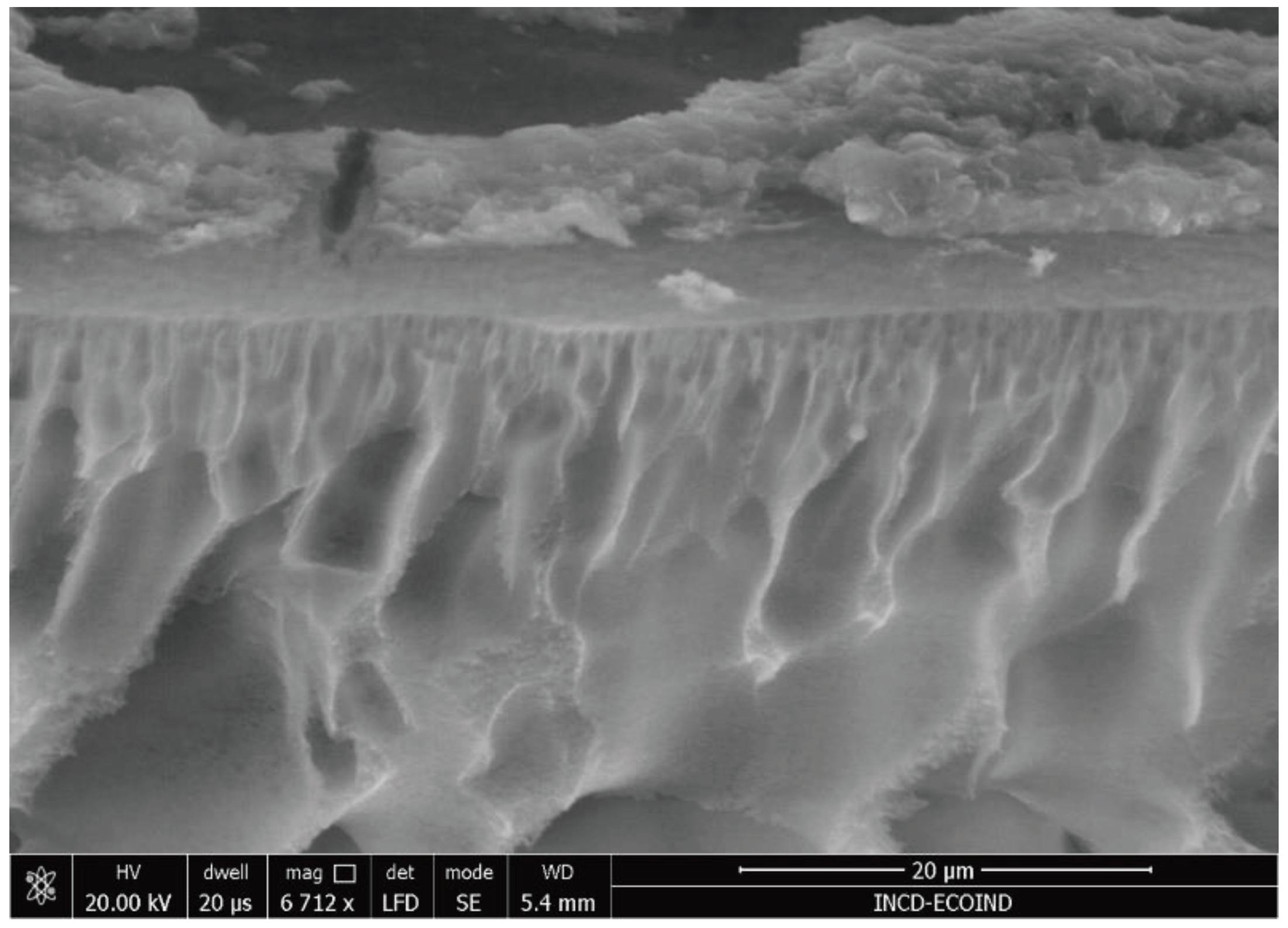

To assess membrane fouling, the ultrapure water flow rate was determined initially and after each separation flow (using equation 3), and the obtained results (presented in

Figure 10) proved that the membrane could be used for at least six catalyst separation cycles, even though membrane fouling was emphasized by the SEM images (see

Figure 11).

All the ultrapure water flows determined after the separations are in the range of 115-135 L/m2 h with an overall difference of less than 16% and an average value of 124.43 L/m2 h.

On the other hand, all the separation flows were determined to be between 90-120 L/m2 h (overall difference less than 25%, average value 101.89 L/m2 h), proving that the photocatalytic step prolongs the membrane lifetime and avoids the issues related to membrane fouling.

It should be stressed that the overall COD removal efficiency is comparable to similar results obtained for solar driven advanced oxidation, membrane-based, or hybrid processes that can be found in the literature [

3,

28,

29]. Therefore, the proposed hybrid PMR system using a visible active photocatalyst in suspension coupled and polymeric membrane process seems to be a viable alternative for the tertiary treatment of municipal wastewater especially when the treated outflow is intended to be reused for various purposes.

4. Conclusions

A solar driven slurry PMR using 1%wt Fe doped TiO2 photocatalysts and a 10% Psf membrane was tested for COD removal using real wastewater under both simulated and natural solar light.

Iron doped titania catalysts were synthesized by the well-known sol-gel method and characterized by SEM, EDX, and XRD. The 1% wt Fe-TiO2 photo catalyst annealed at 400 0C was found to be more efficient than the one annealed at 300 0C. Both synthesized iron doped titania photo catalysts exhibited an improved photocatalytic performance in comparison with TiO2 for the degradation of organic compounds from real wastewater. Iron ceptance by the anatase lattice in the prepared catalysts was proved by the EDX and XRD analyses. Photo degradation experiments using real wastewater proved that iron doping of TiO2 resulted in higher organic compounds degradation efficiency and rate compared with commercial TiO2 (anatase form). A polymeric membrane was prepared using the phase inversion method, immersion precipitation technique starting from a 10% Psf solution, and used in all separation experiments

COD removal efficiencies reached values up to more than 95% under both simulated and natural solar light (for iron doped titania catalyst annealed at 400 0C). The photocatalytic step prevented membrane fouling after six catalyst separation cycles and also acted as a barrier for some organic compounds.

The experimental results proved that the slurry type solar driven PMR should be a suitable alternative for the tertiary treatment of municipal wastewater, but more tests on pilot PMR are needed to obtain data related to its sustainability compared to other processes already used in the tertiary step of wastewater treatment (especially for the visible light-driven PMRs).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.C., L.A.C. and O.T.; methodology, M.A.C.; investigation, C.N., M.B. and I.A.I.; data curation, L.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, O.T., M.A.C. and L.A.C.; supervision, M.A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out under the Nucleu Program within the National Research Development and Innovation Plan 2022-2027 with the support of the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization, contract no. 3N/2022, Project code: PN 23 22 03 01.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Garcia, J.; Garcia-Galan, M.J.; Day, J.W.; Boopathy, R.; White, J.R.; Wallace, S.; Hunter, R.G. A review of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment: Increasing removal with wetlands and reducing environmental impacts. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pandit, P.P.; Chopade, R.L.; Nagar, V.; Aseri, V.; Singh, A.; Awasthi, K.K.; Awasthi, G.; Sankhla, M.S. Eradication of microplastics in wastewater treatment: Overview. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.S.; Kalash, K.R.; Ahmed, A.N.; Albayati, T.M. Performance of a solar photocatalysis reactor as pretreatment for wastewater via UV, UV/TiO2 and UV/H2O2 to control membrane fouling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, R.; Severino, A.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. Which configuration of photocatalytic membrane reactors has a major potential to be used at an industrial level in tertiary sewage wastewater treatment? Catalysts 2023, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argurio, P.; Fontananova, E.; Molinari, R.; Drioli, E. Photocatalytic membranes in photocatalytic membrane reactors. Processes 2018, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filpo, G.; Pantuso, E.; Armentano, K.; Formoso, P.; Di Profio, G. , Poerio, T.; Fontananova, E.; Meringol, C.; Mashin, A.I.; Nicoletta, F.P. Chemical vapor deposition of photocatalyst nanoparticles on PVDF membranes for advanced oxidation processes. Membranes 2018, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, L.A.; Nitoi, I.; Batrinescu, G.; Cristea, I.; Nechifor, G. Degradation of tricolosan from aqueous systems using a photocatalytic membrane reactor. In Proceedings of the 15th International Multidisciplinary GeoConferences SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 18-24 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, M.A.; Chiriac, F.L.; Ionescu, I.A.; Constantin, L.A. Trials on ciprofloxacin removal from wastewater using a photocatalytic membrane reactor. Rom. J. Ecol. Environ. Chem. 2023, 5(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roso, M.; Boaretti, C.; Bonora, R.; Modesti, M.; Lorenzetti, A. Nanostructured active media for volatile organic compounds abatement: The synergy of graphene oxide and semiconductor coupling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 16635–16644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Quan, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Su, Y.; Li, Z. Constructing a visible-light-driven photocatalytic membrane by g-C3N4 quantum dots and TiO2 nanotube array for enhanced water treatment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Tran, Q.B.; Ly, Q.V.; Hai, L.T.; Le, D.T.; Tran, M.B.; Ho, T.T.T.; Nguyen, X.C.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Lam, S.S.; Do, H.-T.; Kim, S.Y.; Tung, T.V.; Le, Q.V. Enhanced visible photocatalytic degradation of diclofenac over N-doped TiO2 assisted with H2O2: A kinetic and pathway study. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8361–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, M.-S.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-R.; Huang, P.-H.; Tung, K.-L. Phosphorus - doped g-C3N4 integrated photocatalytic membrane reactor for wastewater treatment. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 580, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasekou, C.P.; Moustakas, N.G.; Morales-Torres, S.; Pastrana-Martinez, L.M.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Silva, A.M.T.; Dona-Rodriguez, J.M.; Romanos, G.E.; Falaras, P. Ceramic photocatalytic membranes for water filtration under UV and visible light. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 178, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashar, A.; Bhatti, I.A.; Ashraf, M.; Tahir, A.A.; Aziz, H.; Yousuf, M.; Ahmad, M.; Mahsin, M.; Bhutta, Z.A. Fe3+@ZnO/polyester based solar photocatalytic membrane reactor for abatement of RB5 dye. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Huang, L.; Lin, H. Magnetic field assisted arrangement of photocatalytic TiO2 particles on membrane surface to enhance antifouling performance for water treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 570, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, C.; He, A.; Yang, S.-J.; Wu, G.-P.; Darling, S.B.; Xu, Z.-K. Photocatalytic nanofiltration membranes with self-cleaning properties for wastewater. Adv, Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Han, K.; Zhou, G.; Ye, H.; Zhang, X.; Ju, J.; Li, X. Facile synthesis of highly dispersed Ag doped graphene oxide/titanate nanotubes as a visible light photocatalytic membrane for water treatment. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6256–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyarnezhad, S.; Marino, T.; Parsa, J.B.; Galiano, F.; Ursino, C.; Garcia, H.; Puche, M.; Figoli, A. Polyvinylidene fluoride-graphene oxide membranes for dye removal under visible light irradiation. Polymers 2020, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassseh, N.; Taghavi, L.; Barikbin, B.; Nasseri, M.A. Synthesis and characterisation of a novel FeNi3/SiO2/CuS magnetic nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in simulated wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, P. Immobilized TiO2 reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites on optical fibers as high performance photocatalysts for degradation of pharmaceuticals. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 310, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaludin, R.; Rasdi, Z.; Othman, M.H.D.; Kadir, S.H.S.A.; Nor, N.S.M.; Khan, J.; Zain, W.N.W.M.; Ismail, A.F.; Rahman, M.A.; Jaafar, J. Visible light active photocatalytic dual layer hollow fiber (DLHF) membrane and its potential in mitigating the detrimental effects of bisphenol A in water. Membranes 2020, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitoi, I; Constantin, L.A.; Oancea, P.; Cristea, I.; Crisan, M. TiO2 solar light photocatalysis a promising treatment method for wastewater with trinitrotoluene content. In Proceedings of the 15th International Multidisciplinary GeoConferences SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 18-24 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, M.; Raileanu, M.; Dragan, N.; Crisan, D.; Ianculescu, A.; Nitoi, I.; Oancea, P.; Somacescu, S.; Stanica, N.; Vasile, B.; Stan, C. Sol-gel iron-doped TiO2 nanopowders with photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. A: Gen 2015, 504, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic, Z.Z.; Dojcoinovic, M.P.; Vujancevic, J.D.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; Ognjanovic, M.; Tadic, N.B.; Stojadinovic, S.; Brankovic, G.O.; Nikolic, M.V. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under natural sunlight using iron titanate nanoparticles prepared by a sol-gel modified method. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 20078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, L.A.; Constantin, M.A.; Ionescu, I.A.; Puiu, M.D. Polysulfone and cellulose acetate–based membranes’ potential application to photocatalytic membrane reactors. Rom. J. Ecol. Environ. Chem. 2023, 5(2), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, L.A.; Ionescu, I.A.; Constantin, M.A.; Stefanescu, M.; Marin, N.M. Metal – titanium dioxide doped catalysts for wastewater treatment under simulated solar light. In Book of Abstracts of the 26th International Symposium The Environment and the Industry SIMI, Bucharest, Romania, 27-29 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nitoi, I.; Oancea, P.; Raileanu, M.; Crisan, M.; Constantin, L.; Cristea, I. UV-VIS photocatalytic degradation of nitrobenzene from water using heavy metal doped titania. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 21, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, V.M.; Feroz, S.; Dutta, S. Solar nanophotocatalytic pretreatment of seawater: Process optimization and performance evaluation using response surface methodology and genetic algorithm. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Z.; Lee, C.-G.; Li, Q.; Khan, S.J.; Ahmad, N.M.; Jamal, Y.; Huang, X.; Javed, H. Bi-polymer electrospun nanofibers embedding Ag3PO4/P25 composite for efficient photocatalytic degradation and antimicrobial activity. Catalysts, 2020, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).