Submitted:

09 February 2024

Posted:

09 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Rationale

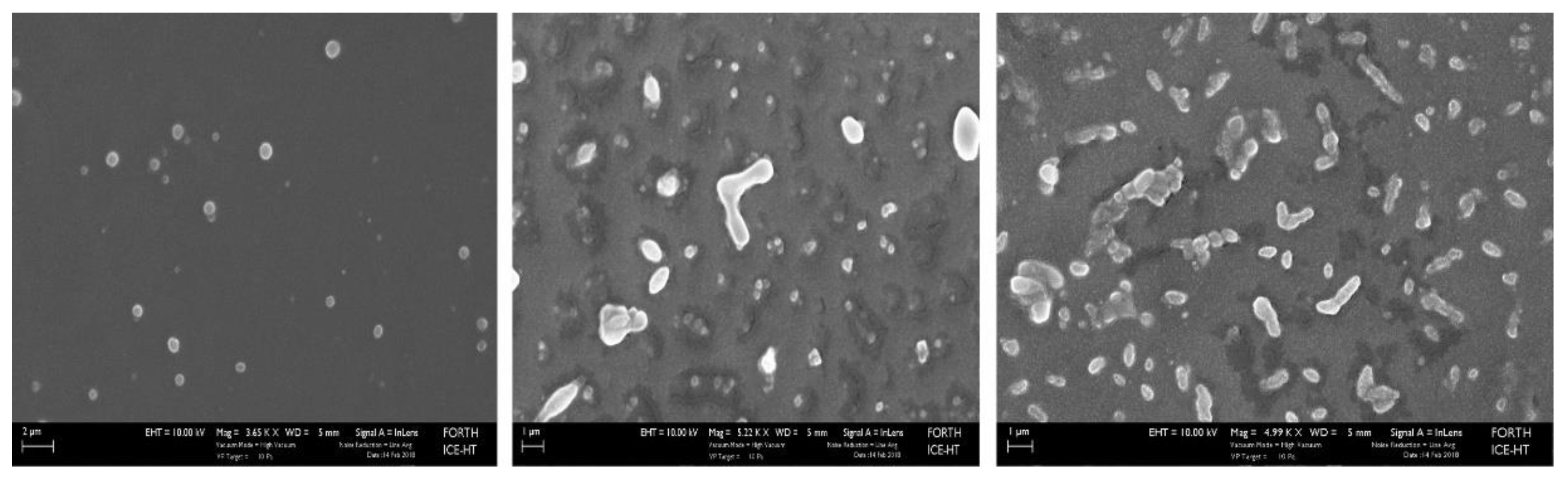

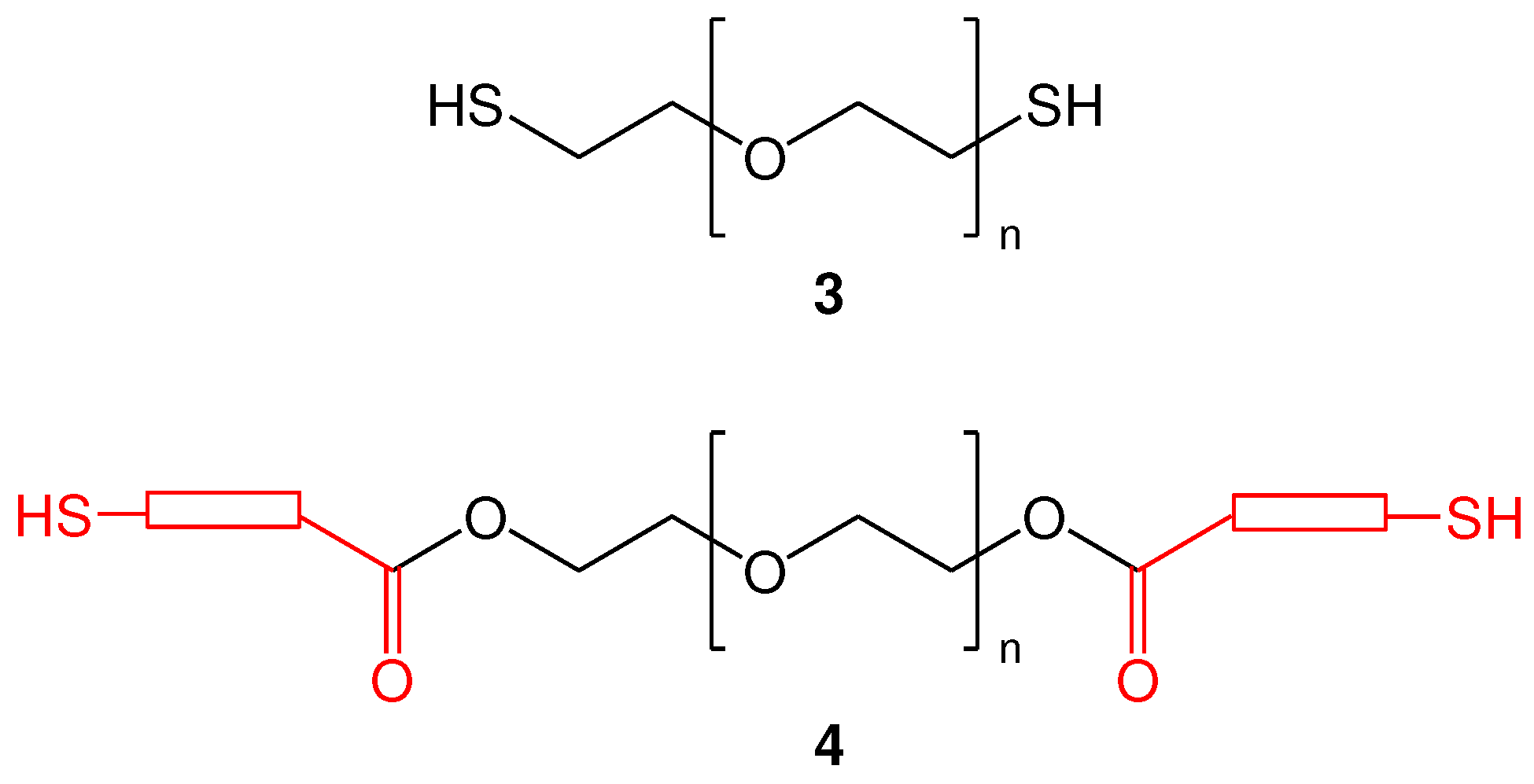

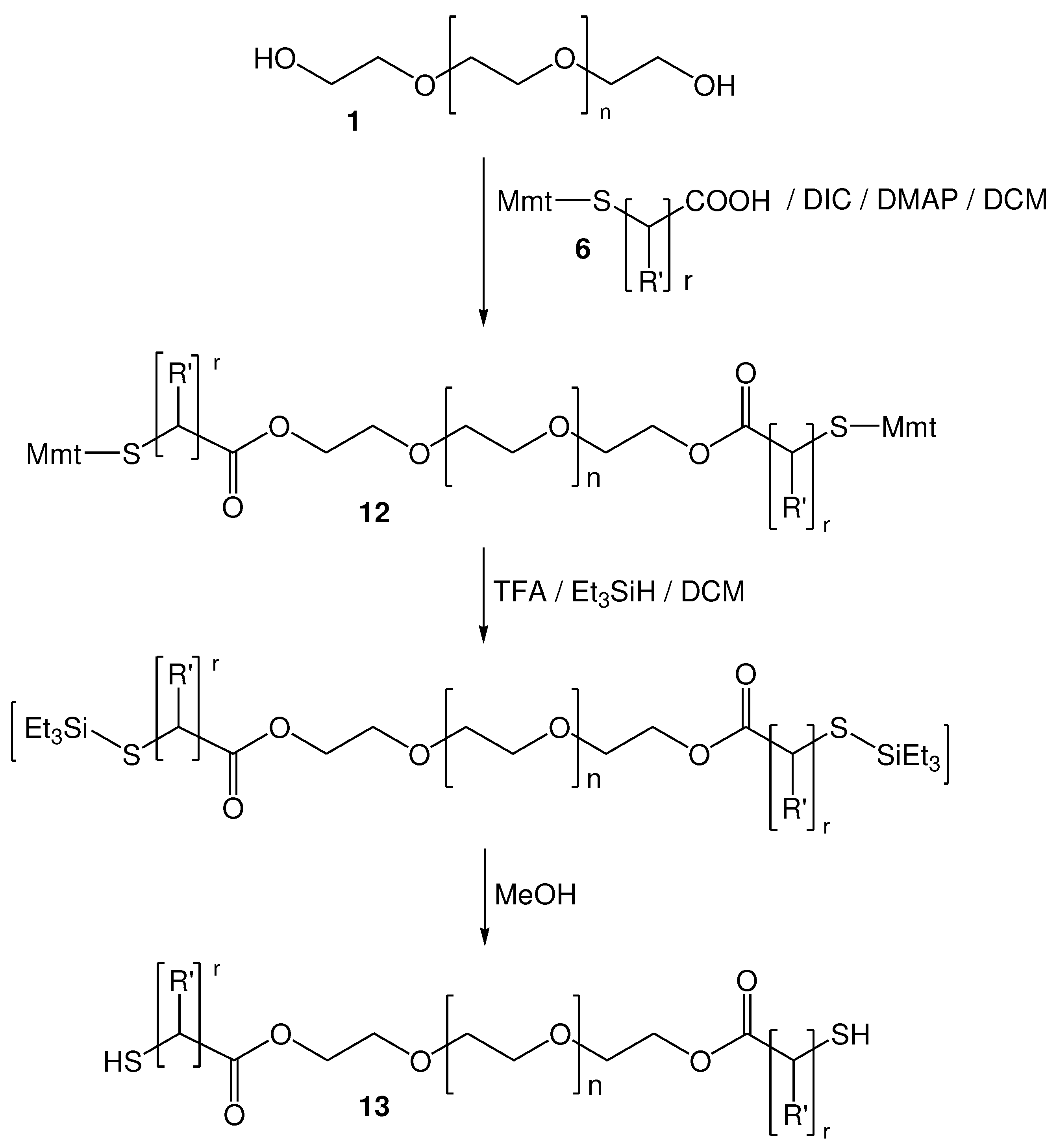

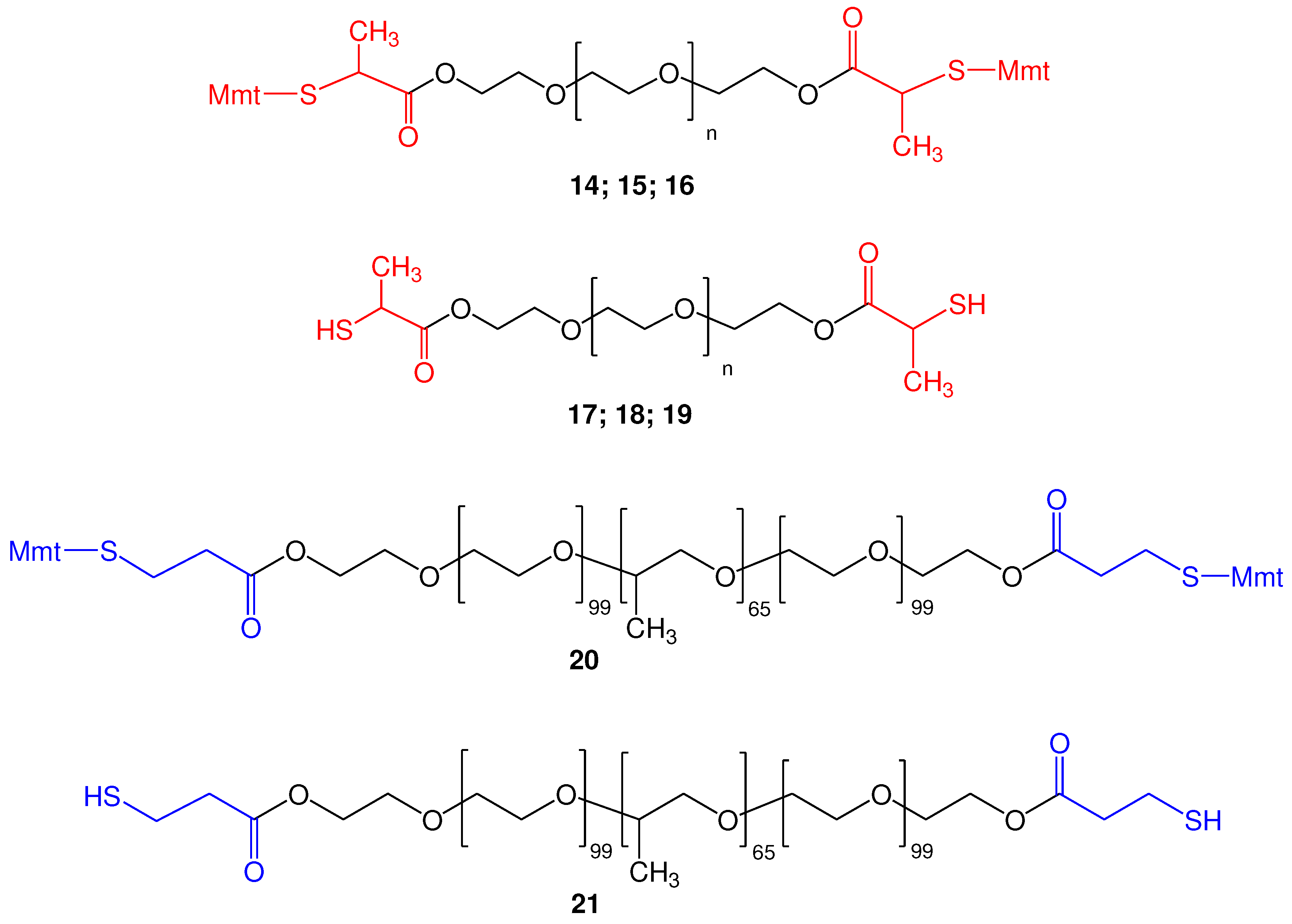

2.2. Synthesis of functionalized α,ω-bis-mercaptoacyl poly(alkyl oxide)s

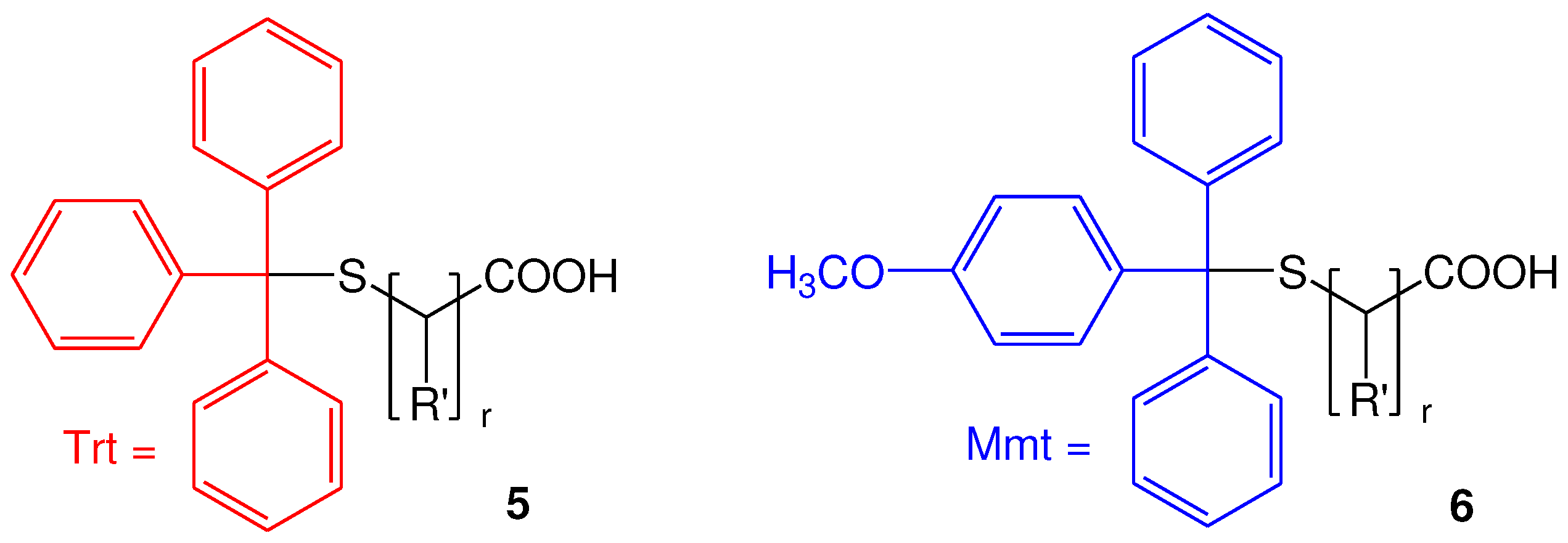

2.2.1. Selection and Synthesis of S-Mmt mercapto acids

2.2.2. Synthesis of di-S-Mmt-PEG-dithiols and PEG-dithiols

2.2.3. Synthesis of di-S-Mmt-pluronic-dithiols and pluronic-dithiols

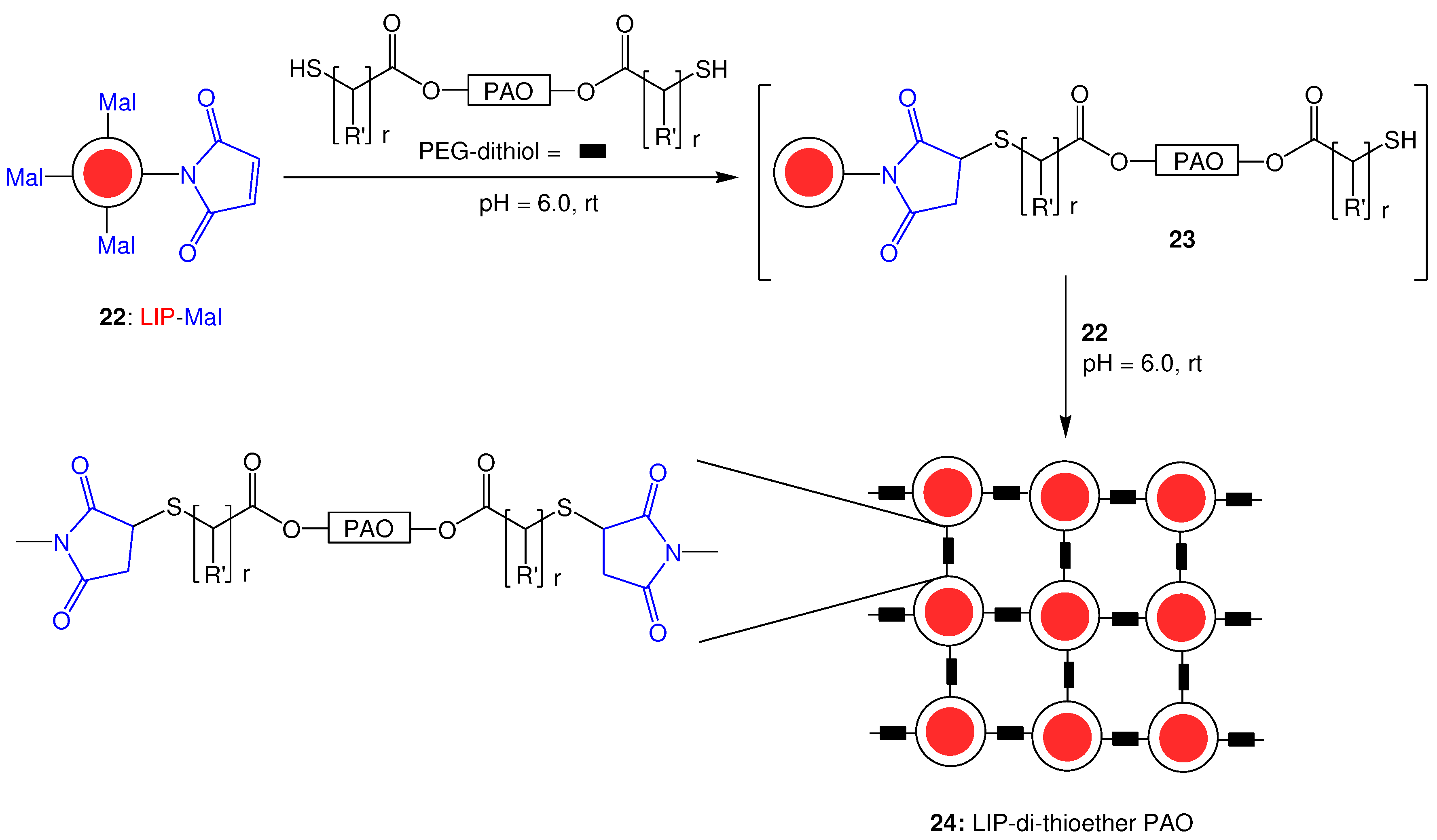

2.3. Thia-Michael reaction with pre-formed liposomes maleimides

2.3.1. General method

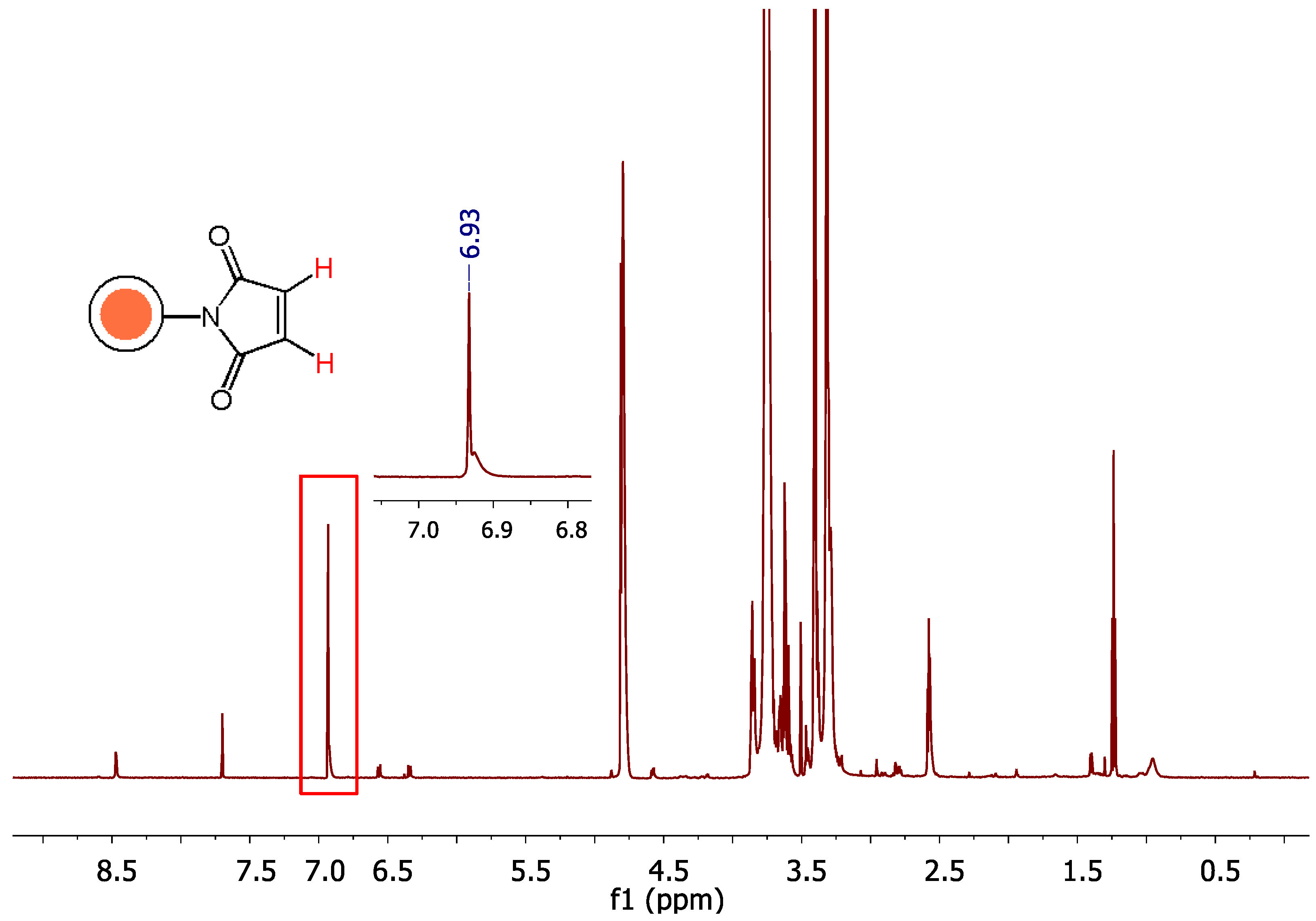

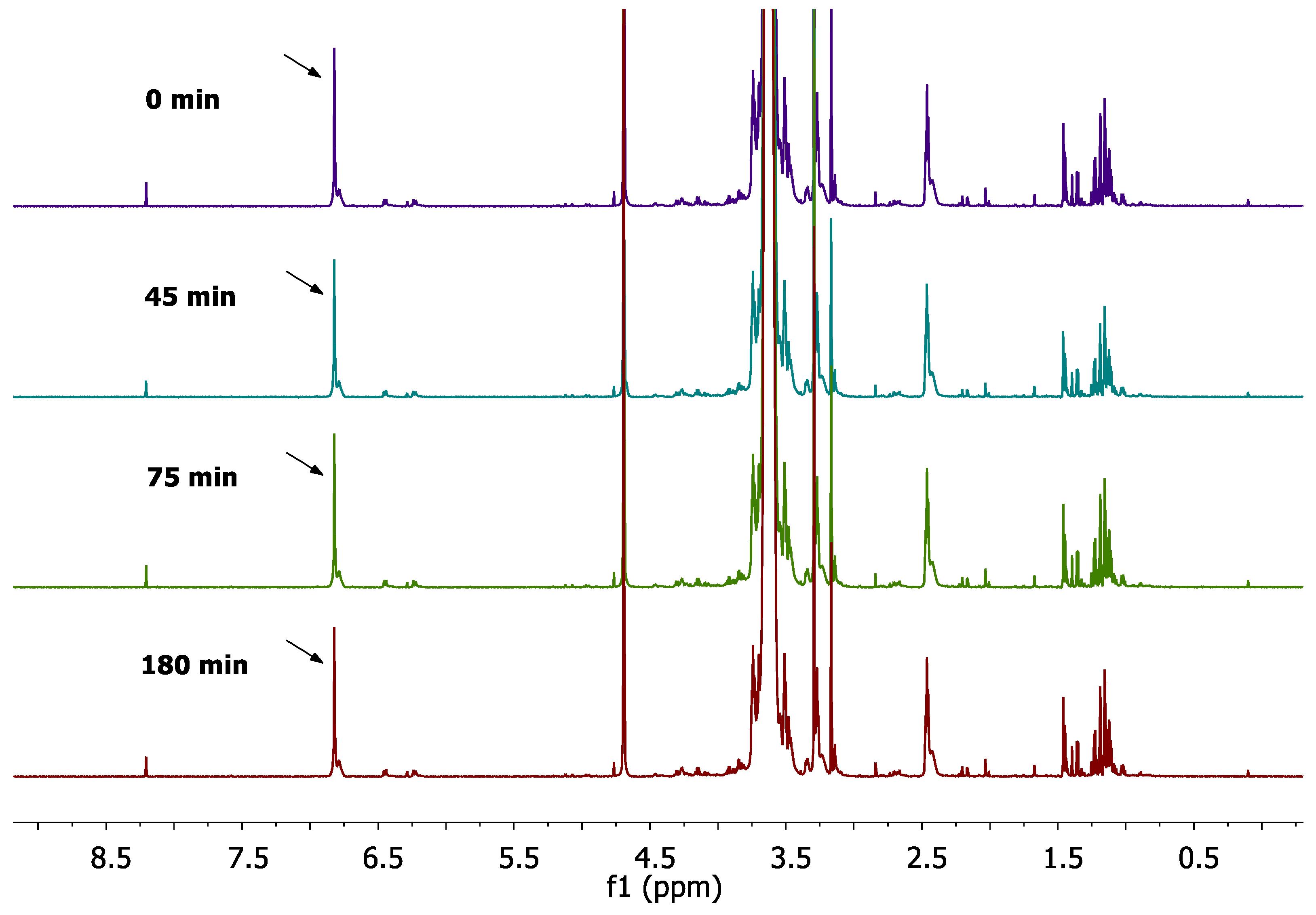

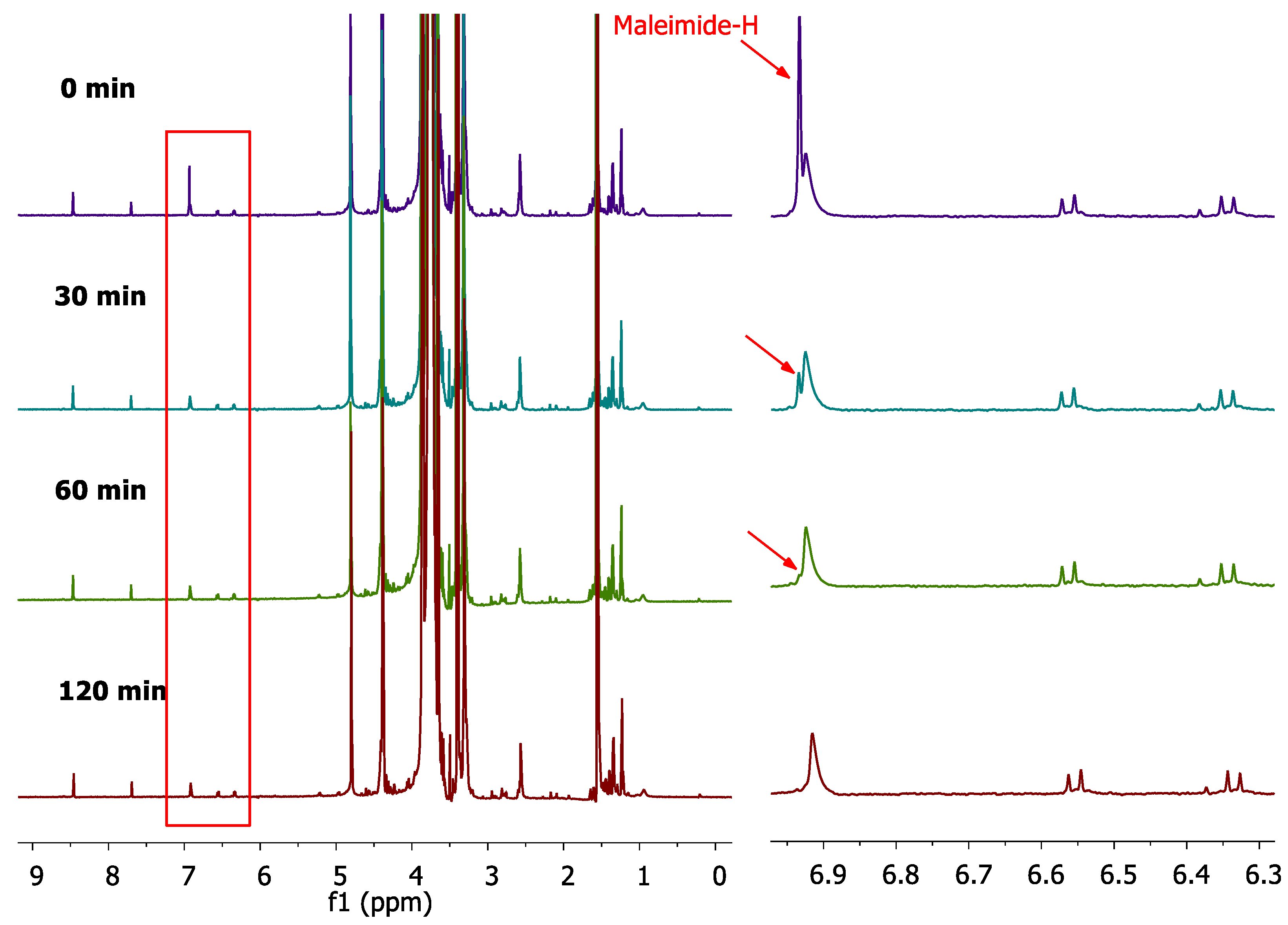

2.3.2. Monitoring of the reaction progress; Optimization

2.4. Effect of thioether cross-linking on liposome size

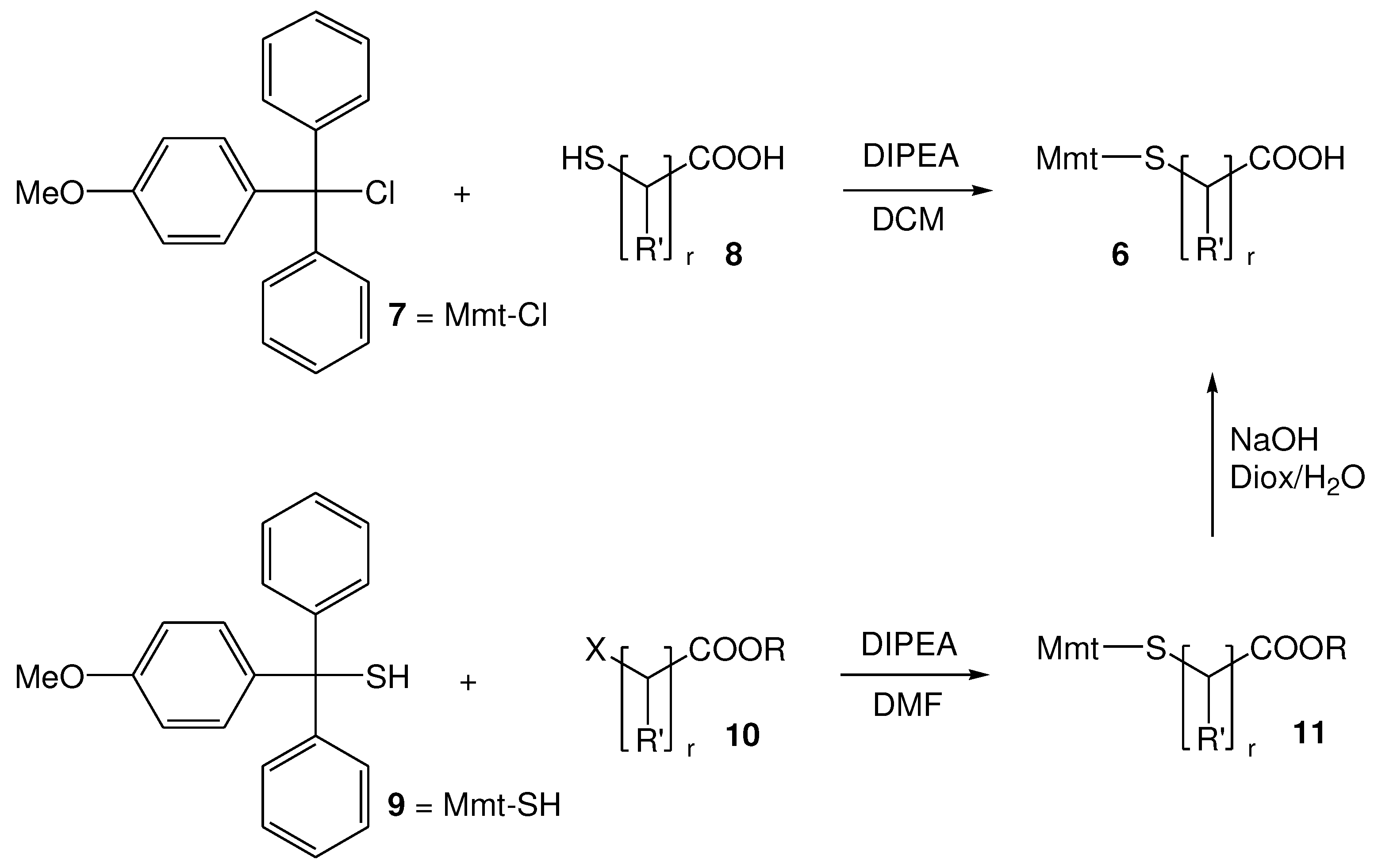

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images

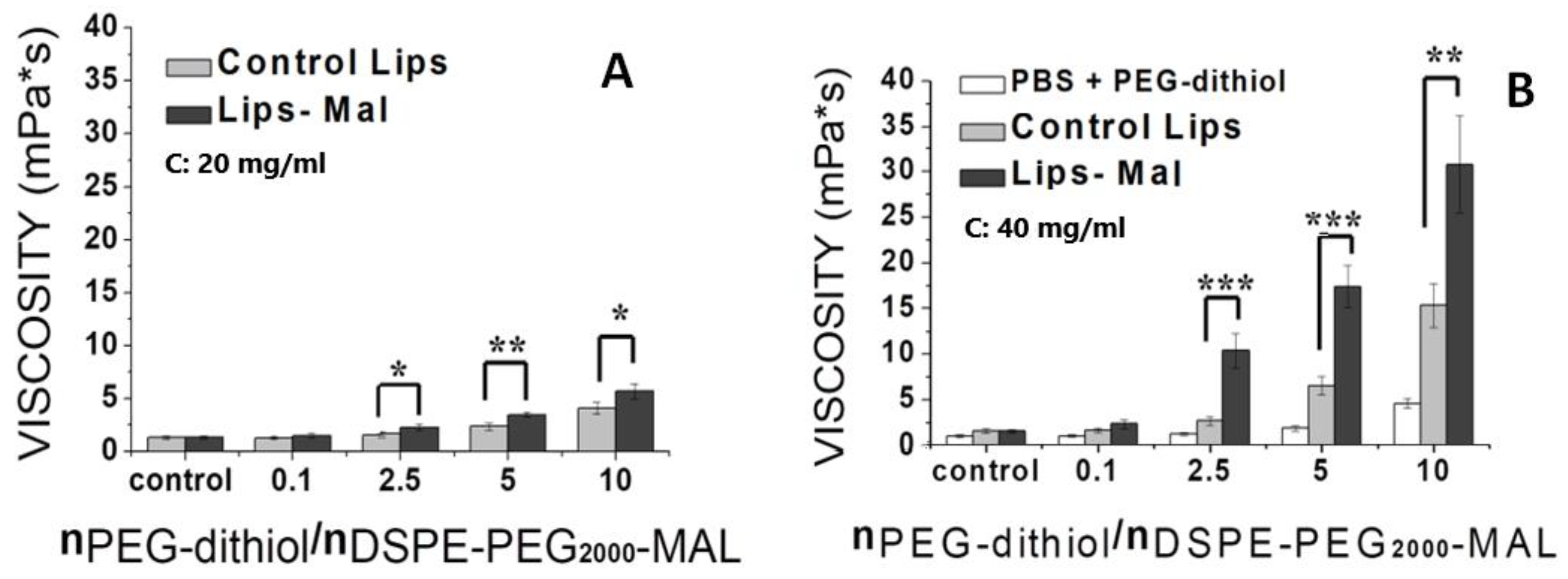

2.6. Effect of thioether cross-linking on liposome scaffold viscosity

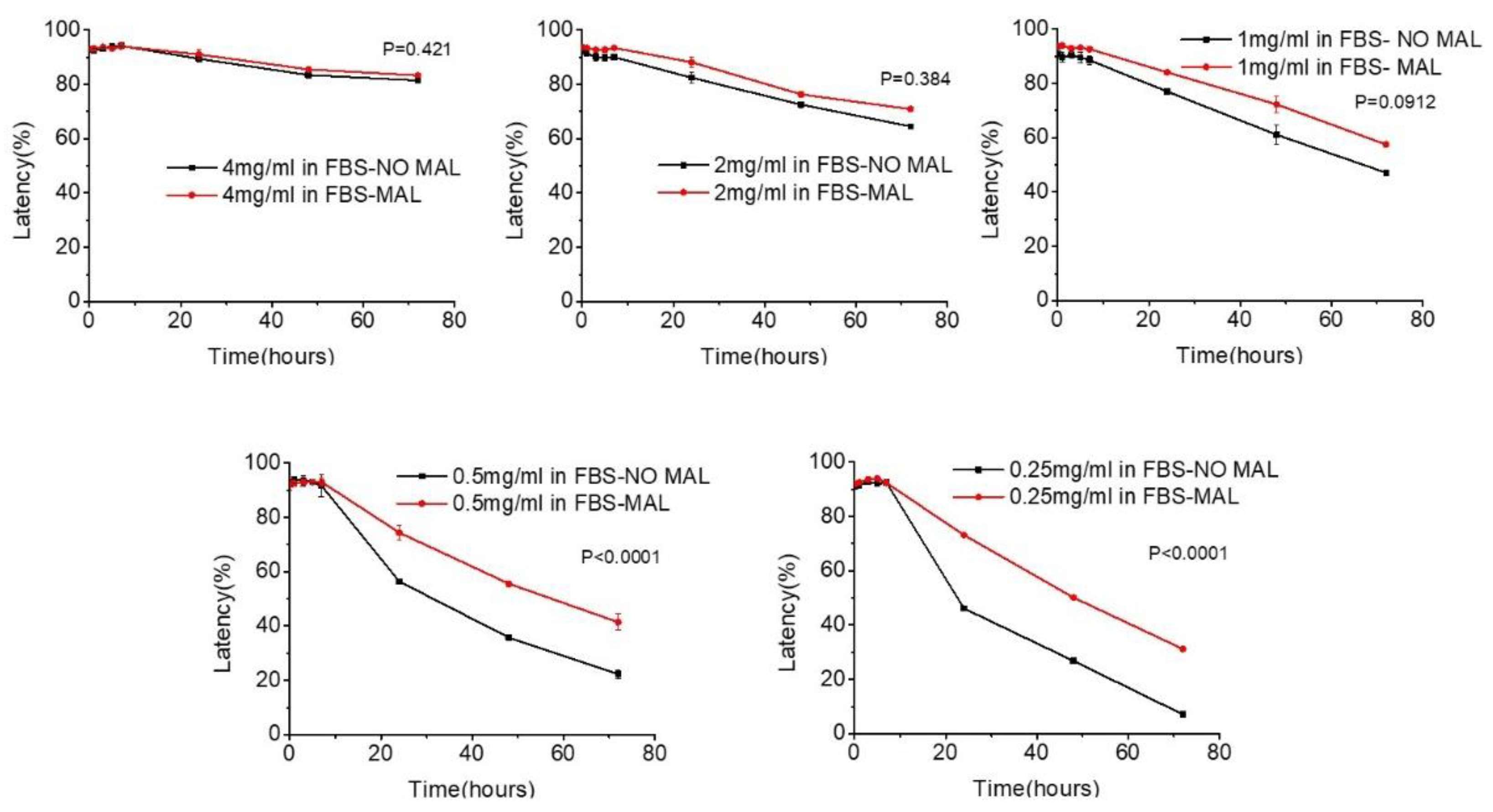

2.7. Evaluation of thioether cross-linked liposomes as drug eluting systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

3.1.1. Synthesis of α,ω-bis-mercaptoacyl poly(alkyl oxide)s

3.1.2. Liposome preparations

3.1.3. Liposome physicochemical characterization

3.2. Synthetic Procedures

3.2.1. S-Mmt-mercaptopropionic acids (S-Mmt-2-mercaptopropionic acid 6a; S-Mmt-3-mercaptopropionic acid 6b)

3.2.2. Di-S-Mmt-di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG10.000 (14)

3.2.3. Di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG10.000 (17)

3.2.4. Di-S-Mmt-di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG4.000 (15)

3.2.5. Di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG4.000 (18)

3.2.6. Di-S-Mmt-di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG1.000 (16)

3.2.7. Di-2-mercaptopropionyl PEG1.000 (19)

3.2.8. Di-S-Mmt-di-3-mercaptopropionyl Pluronic (20)

3.2.9. Di-3-mercaptopropionyl Pluronic (21)

3.2.10. Liposome Preparation Procedure

3.2.11. Reaction of di-thioether-PEGs with pre-formed LIP-maleimides

3.2.12. Liposome Integrity Studies

3.2.13. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bré, L.P.; Zheng, Y.; Pêgo, A.P.; Wang, W. Taking tissue adhesives to the future: From traditional synthetic to new biomimetic approaches. Biomater. Sci. 2013, 1, 239-253. [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.S.; Xu, Q.; Kim, N.; Hanes, J.; Ensign, L.M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 99, 28-51. [CrossRef]

- Veronese, F.M.; Pasut, G. PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today (2005) 10, 1451–1458. [CrossRef]

- Alconcel, S.N.S.; Baas, A.S.; Maynard, H.D. FDA-approved poly(ethylene glycol)–protein conjugate drugs. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1442–1448. [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Kazemi, S.; Askari, F. Pluronic as nano-carier for drug delivery systems. Nanomed. Res. J. 2018, 3, 174-179. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qiu, H.; Yin, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Polymeric Drug Delivery System Based on Pluronics for Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2012, 26, 3610. [CrossRef]

- Batrakova, E.V.; Kabanov, A.V. Pluronic block copolymers: evolution of drug delivery concept from inert nanocarriers to biological response modifiers. J. Control. Release 2008, 130, 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Hutanu, D.; Frishberg, M.D.; Guo, L.; Darie, C.C. Recent Applications of Polyethylene Glycols (PEGs) and PEG Derivatives. Mod. Chem. Appl. 2014, 2, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Kozlowski, A. Poly(ethylene glycol) derivatives with proximal reactive groups. US Patent: US6437025B1.

- Ravasco, J.M.; Faustino, H.; Trindade, A.; Gois, P.M.P. Bioconjugation with Maleimides: A Useful Tool for Chemical Biology. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 25, 43-59. [CrossRef]

- Renault, K.; Fredy, J.W.; Renard, P.Y.; Sabot, C. Covalent Modification of Biomolecules through Maleimide-Based Labeling Strategies. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2497-2513. [CrossRef]

- Kharkar, P.M.; Rehmann, M.S.; Skeens, K.M.; Maverakis, E.; Kloxin, A.M. Thiol-ene Click Hydrogels for Therapeutic Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 165-179. [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, C.E.; Bowman, C.N. Thiol-ene click chemistry, Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2010, 49, 1540-1573. [CrossRef]

- Goessl, A.; Tirelli, N.; Hubbell, J.A. A Hydrogel System for Stimulus-Responsive, Oxygen-Sensitive In Situ Gelation. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2004, 15, 895-904. [CrossRef]

- Buwalda, S.J.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J. In Situ Forming Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Poly(L-Lactide) Hydrogels via Michael Addition: Mechanical Properties, Degradation, and Protein Release. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2012, 213, 766–775. [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, C.; van der Aa, L.J.; Zhong, Z.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J. Novel In Situ Forming, Degradable Dextran Hydrogels by Michael Addition Chemistry: Synthesis, Rheology, and Degradation. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 1165–1173. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, K.; Hirase, T.; Nemoto, S.; Hatta, T.; Nagasaki, Y. Facile Construction of Sulfanyl-Terminated Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Brushed Layer on a Gold Surface for Protein Immobilization by the Combined use of Sulfanyl-Ended Telechelic and Semitelechelic Poly(Ethylene Glycol)s. Langmuir 2008, 24, 9623-9629. [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Baldwin, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kiick, K.L. Production of Heparin-Functionalized Hydrogels for the Development of Responsive and Controlled Growth Factor Delivery Systems. J. Control. Release 2007, 122, 287-296. [CrossRef]

- Belair, D.G.; Miller, M.J.; Wang, S.; Darjatmoko, S.R.; Binder, B.Y.; Sheibani, N.; Murphy, W.L. Differential Regulation of Angiogenesis using Degradable VEGF-Binding Microspheres. Biomaterials 2016, 93, 7-37. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Feng, Z.G.; Zhang, A.Y.; Sun, L.G.; Qian, L. Synthesis and Characterization of Three-Dimensional Crosslinked Networks Based on Self-Assembly of α-Cyclodextrins with Thiolated 4-arm PEG using a Three-Step Oxidation. Soft. Matter. 2006, 2, 343-349. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.J.; Brash, J.L. Synthesis and Characterization of thiol-terminated Poly(Ethylene Oxide) for Chemisorption to Gold Surface. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 594-607. [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.K.S.; Depew, M.C. Some Mechanistic Insights in the Behaviour of Thiol Containing Antioxidant Polymers in Lignin Oxidation Processes. Res. Chem. Intermed. 1996, 22, 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Long, H.; Malkoch, M.; Kristofer Gamstedt E., Berglund, L.; Hult, A. Characterization of Well-Defined Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels Prepared by Thiol-Ene Chemistry. Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 4044-4054. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Xin, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhou, L.L.; Peng, L.; Yuan, J.Y. Facile and Efficient Fabrication of Photoresponsive Microgels via Thiol-Michael Addition. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33, 1952-1957. [CrossRef]

- Zustiak, S.P.; Leach, J.B. Hydrolytically Degradable Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Scaffolds with Tunable Degradation and Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1348-1357. [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Lee, S.; Bararpour, L.; Yang, F. Long-term Controlled Protein Release from Poly(ethylene glycol) Hydrogels by Modulating Mesh Size and Degradation. Macromol. Biosci. 2015, 15, 1679-1686. [CrossRef]

- Picheth, G.F.; da Silva, L.C.E.; Giglio, L.P.; Plivelic, T.S.; de Oliveira, M.G. S-nitrosothiol-terminated Pluronic F127: Influence of microstructure on nitric oxide release. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 576, 457–467. [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Zhang, H.; Song, L.; Cui, L.; Cao, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Z.; Yang, H. Thiol/acrylate-modified PEO-PPO-PEO triblocks used as reactive and thermosensitive copolymers. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 2621–2628. [CrossRef]

- Mulay, P.; Shrikhande, G.; Puskas, J. Synthesis of Mono- and Dithiols of Tetraethylene Glycol and Poly(ethylene glycol)s via Enzyme Catalysis. Catalysts 2019, 9, 228. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Du, C.; Guo, N.; Teng, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Yu, P.; Galons, H. Composition design and medical application of liposomes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 164, 640-653. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 1372. [CrossRef]

- Bulbake, U.; Doppalapudi, S.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W. Liposomal Formulations in Clinical Use: An Updated Review. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zylberberg, C.; Matosevic, S. Pharmaceutical liposomal drug delivery: a review of new delivery systems and a look at the regulatory landscape. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 3319-3329. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Kiick, K.L. Liposome-cross-linked hybrid hydrogels for glutathione- triggered delivery of multiple cargo molecules. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 601-614. [CrossRef]

- Spears, R. J.; McMahon, C.; Chudasama, V. Cysteine protecting groups: applications in peptide and protein science. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11098-11155. [CrossRef]

- Mourtas, S.; Gatos, D.; Kalaitzi, V.; Katakalou, C.; Barlos, K. S-4-Methoxytrityl mercapto acids: synthesis and application. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 6965-6967. [CrossRef]

- Neises, B.; Steglich, W. Simple Method for the Esterification of Carboxylic Acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1978, 17, 522-524. [CrossRef]

- Tsakos, M.; Schaffert, E.S.; Clement, L.L.; Villadsen, N.L.; Poulsen, T.B. Ester coupling reactions – an enduring challenge in the chemical synthesis of bioactive natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 605-632. [CrossRef]

- McCourt, R.O.; Scanlan, E.M. A Sequential Acyl Thiol-Ene and Thiolactonization Approach for the Synthesis of δ-Thiolactones. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3460-3464. [CrossRef]

- Espeel, P.; Du Prez, F.E.; One-pot multi-step reactions based on thiolactone chemistry: A powerful synthetic tool in polymer science. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 62, 247-272. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Makimura, K.; Matsuoka, S. Thiol-Mediated Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cysteine-Derived β-Thiolactone and Unique Features of Product Polythioester. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1135−1141. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.A.; Blanchette, M.; Baker, M.L.; Guindon, C.A. Trialkylsilanes as scavengers for the trifluoroacetic acid deblocking of protecting groups in peptide synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 2739-2742. [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-K.; Schla, M. A Catalytic Synthesis of Thiosilanes and Silthianes: Palladium Nanoparticle-Mediated Cross-Coupling of Silanes with Thio Phenyl and Thio Vinyl Ethers through Selective Carbon-Sulfur Bond Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7386–7392. [CrossRef]

- Kleckner, I.R.; Foster, M.P. An introduction to NMR-based approaches for measuring protein dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011, 1814, 942-968. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.G.; Kroenke, C.D.; Loria, J.P. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Meth. Enzymol. 2001, 339, 204–238. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.G.; Grey, M.J.; Wang, C. Solution nmr spin relaxation methods for characterizing chemical exchange in high-molecular-weight systems. Meth. Enzymol. 2005, 394, 430–465. [CrossRef]

- Immordino, M.L.; Dosio, F.; Cattel, L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 1, 297-315.

- Marazioti, A.; Papadia, K.; Kannavou, M.; Spella, M.; Basta, A.; de Lastic, A-L; Rodi, M.; Mouzaki, A.; Samiotaki, M.; Panayotou, G.; Stathopoulos, G.T.; Antimisiaris, S.G. Cellular vesicles: New insights in engineering methods, interaction with cells and potential for brain targeting. JPET 2019, 370, 772–785. [CrossRef]

| Control Lips + PEG-dithiol | PC-Lip-Mal + PEG-dithiol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No b | mol PEG-dithiol/ mol Maleimide | Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | PDI | Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | PDI |

| 1 | - | 105.10 ± 2.07 | 0.158 | 101.80 ± 0.47 | 0.190 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 96.48 ± 0.74 | 0.199 | 128.90 ± 1.3 | 0.199 |

| 3 | 5 | 111.60 ± 0.95 | 0.231 | 121.30 ± 1.4 | 0.318 |

| 4 | 10 | 105.50 ± 3.7 | 0.260 | 153.10 ± 10.4 | 0.409 |

| Control Lips + PEG-dithiol | PC-Lip-Mal + PEG-dithiol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No b | mol PEG-dithiol/ mol Maleimide | Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | PDI | Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | PDI |

| 1 | - | 89.38 ± 0.85 | 0.154 | 90.93 ± 0.98 | 0.178 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 89.06 ± 0.79 | 0.169 | 138.30 ± 2.2 | 0.244 |

| 3 | 5 | 91.90 ± 1.6 | 0.246 | 140.20 ± 3.4 | 0.260 |

| 4 | 10 | 100.60 ± 1.4 | 0.261 | 148.00 ± 4.5 | 0.375 |

| Lipid Composition |

Mean hydrodynamic diameter (nm) |

PDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Reaction |

After reaction |

Before reaction |

After Reaction |

|

| Control Lips | 99.4 ± 0.543 | 100.8 ± 0.757 | 0.180 | 0.192 |

| HPC-Lip-Mal | 100.3 ± 0.621 | 145.7 ± 2.875 | 0.199 | 0.317 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).