Submitted:

07 February 2024

Posted:

08 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

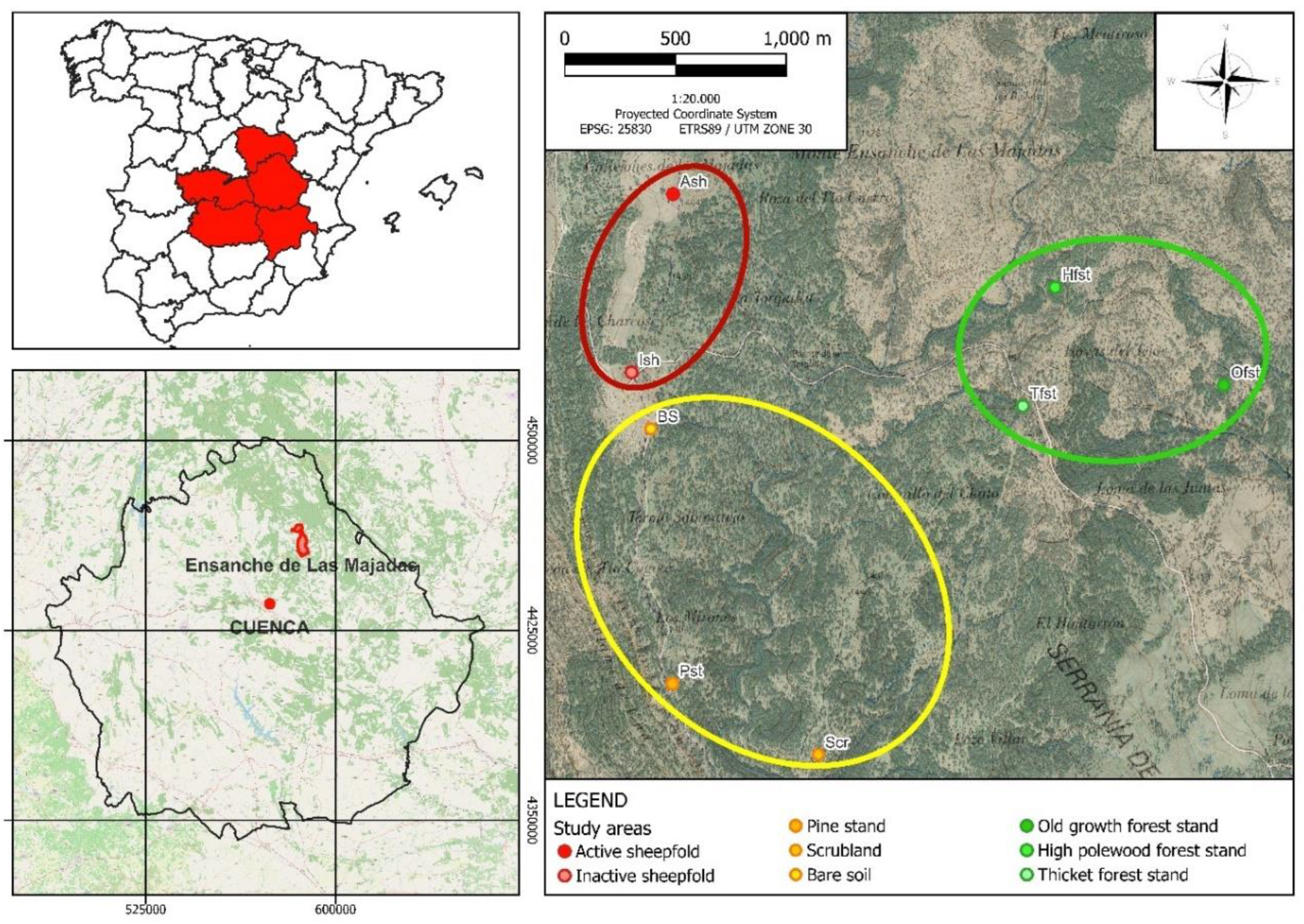

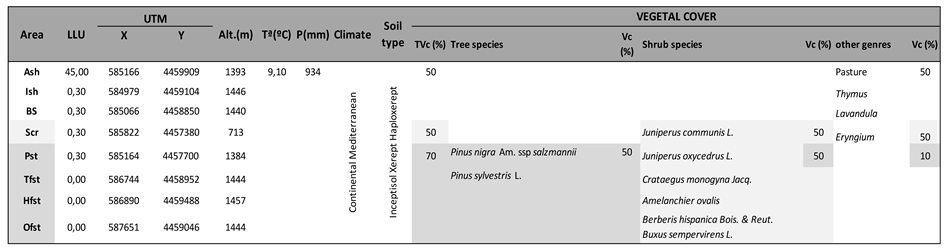

2.1. Study area and experimental design

2.2. Parameters analyzed

2.3. Soil quality index (SQI)

2.4. Soil multiparametrix index development (SSIL)

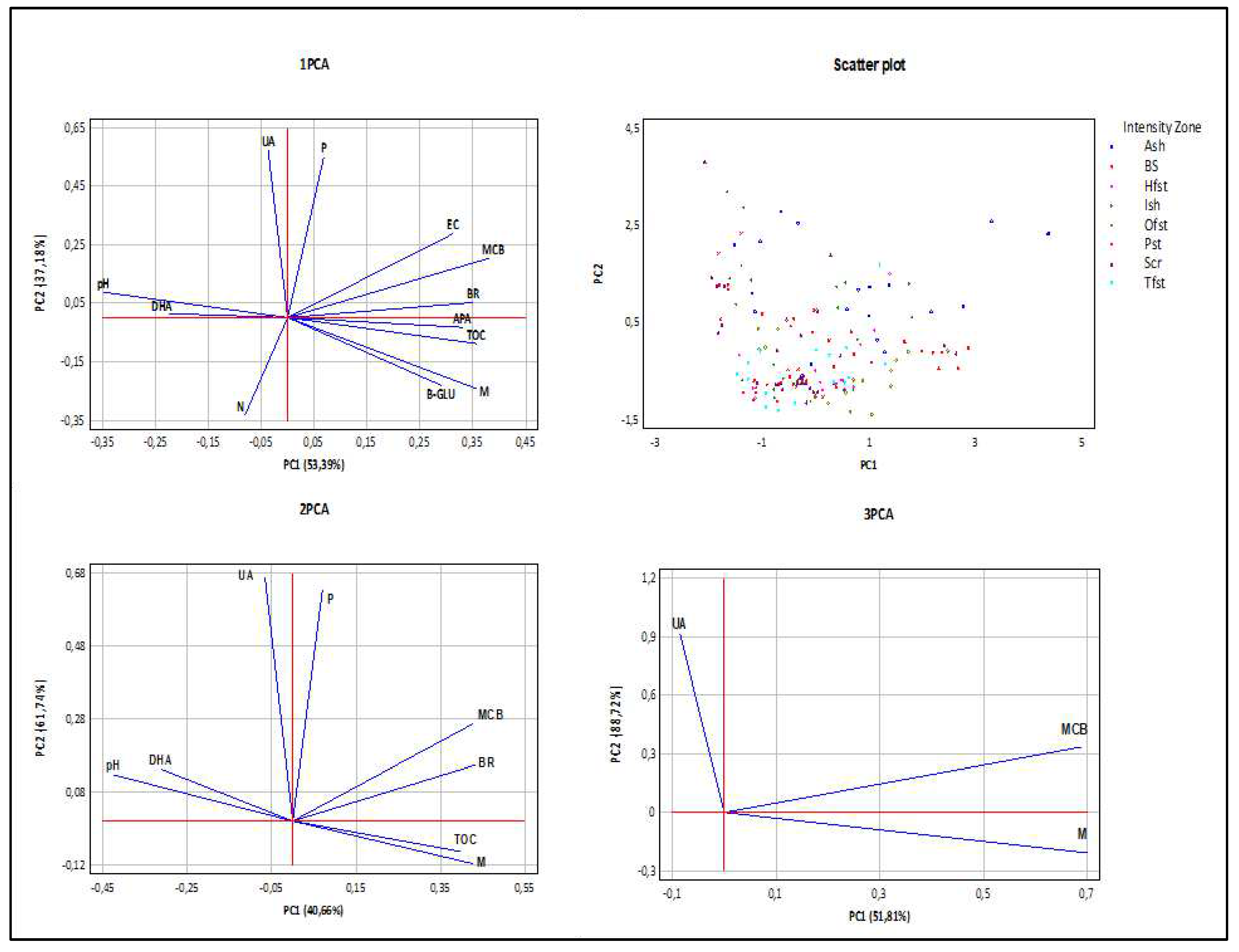

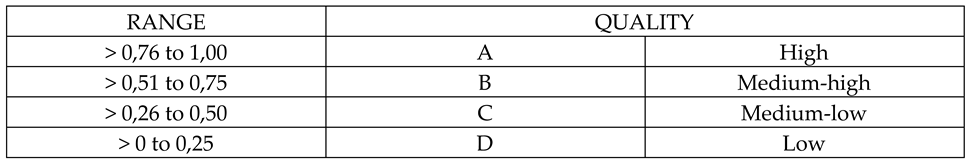

2.5. Statististical analisys

3. Results

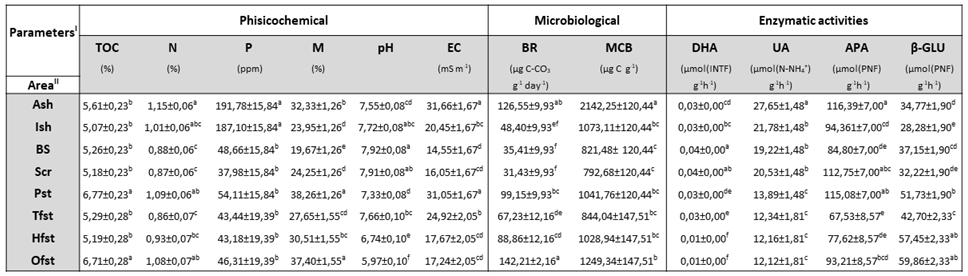

3.1. Physicochemical, Microbiological and Biochemical Characterization of soils

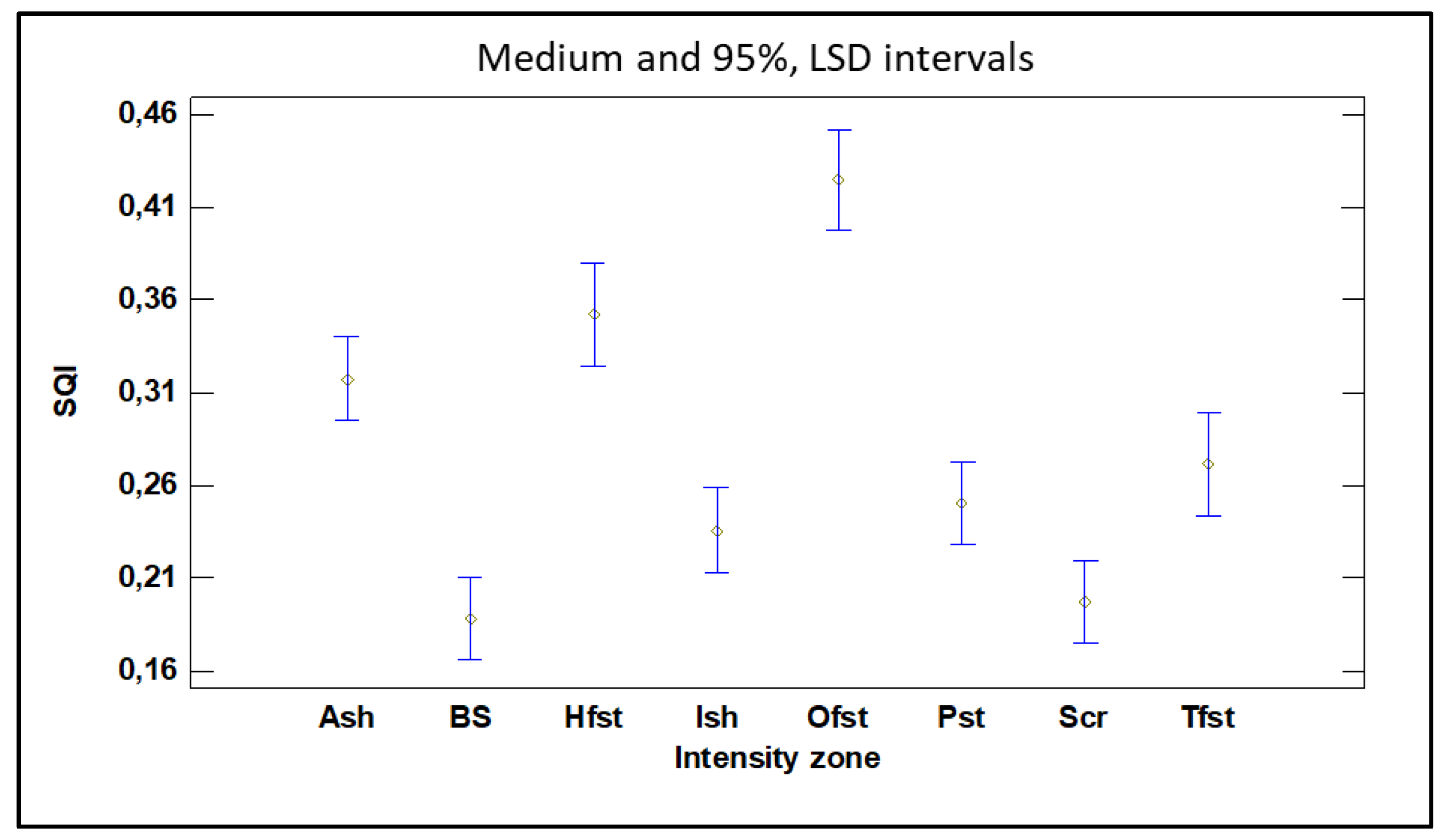

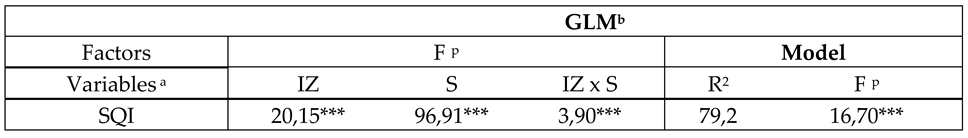

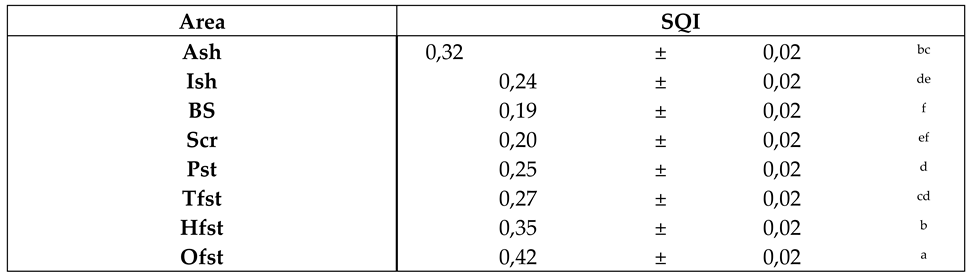

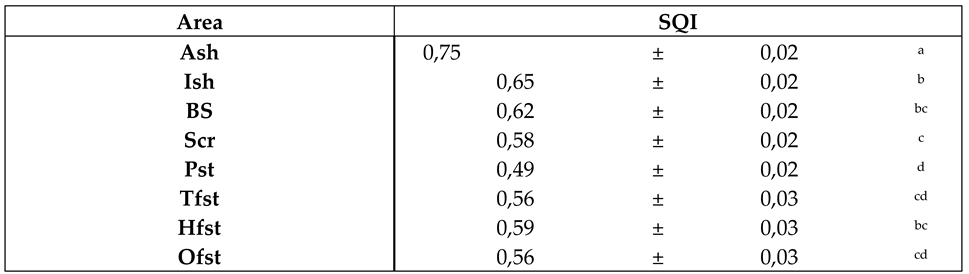

3.2. Sensitivity analysis of the soil quality index SQI applied

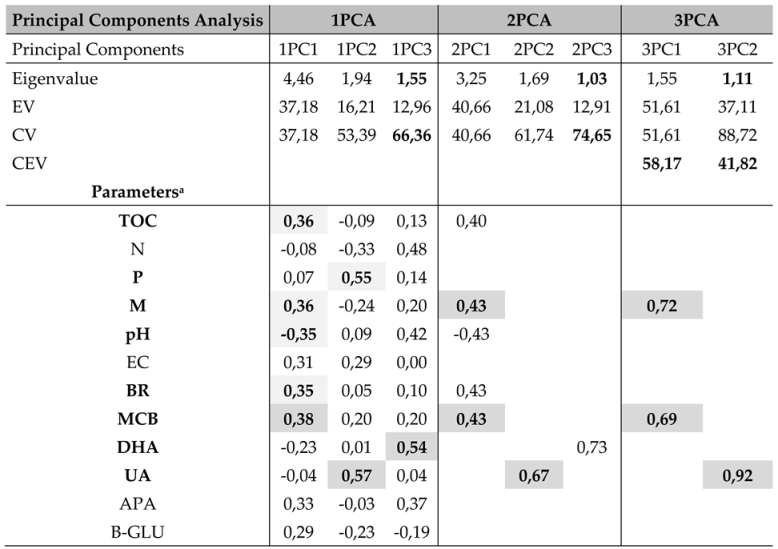

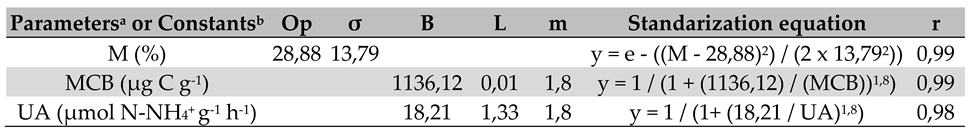

3.3. New soil multiparametric index development (SSIL)

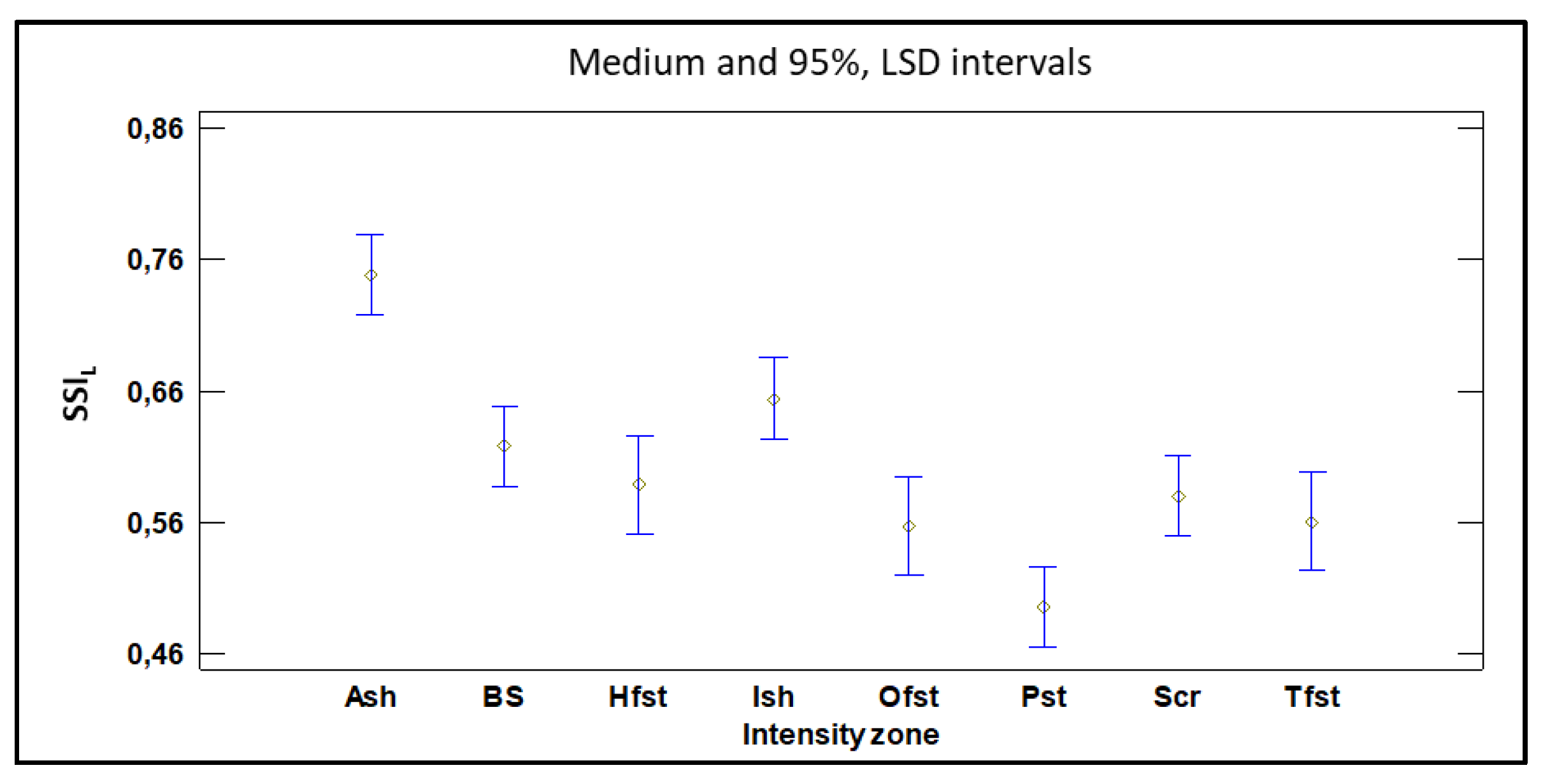

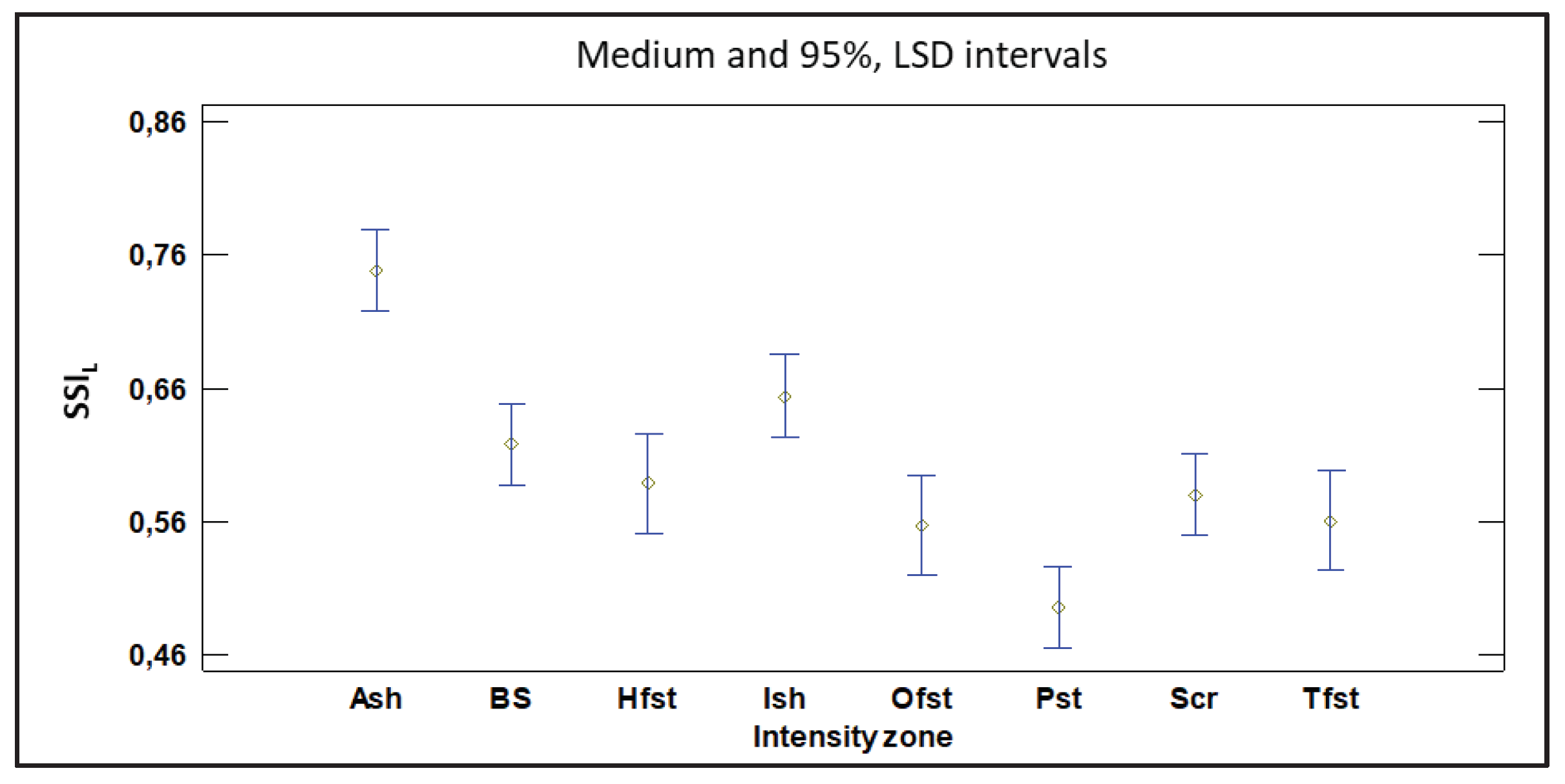

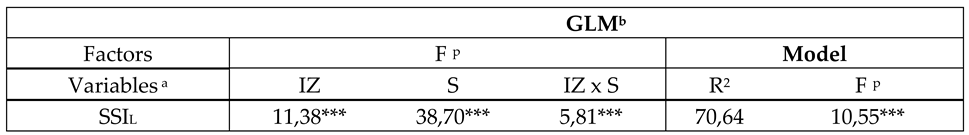

3.4. Sensitivity analysis of the new multiparametric index SSIL

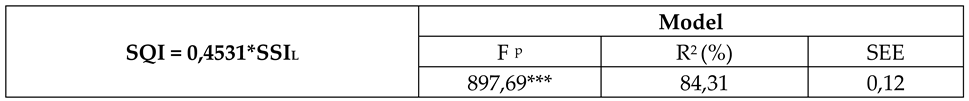

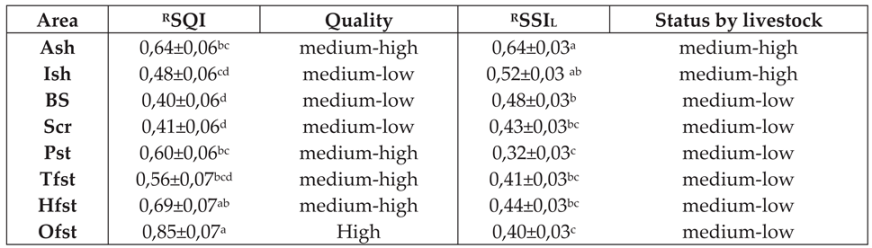

3.5. Correlation between SQI and SSIL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Legazpi, V. La ganadería en la provincia de Cuenca en el siglo XVIII. UCLM, Cuenca, 2000.

- Bokdam, J.; Gleichman, J.M. Effects of Grazing by Free-Ranging Cattle on Vegetation Dynamics in a Continental North-West European Heathland. Journal of Applied Ecology 2000, 37, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D.; Ponder, F.; Hubbard, V.C. Effects of soil compaction, forest leaf litter and nitrogen fertilizer on two oak species and microbial activity. Applied Soil Ecology 2003, 23, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitian, R.; Bardgett, R.D. Plant and soil microbial responses to defoliation in temperate semi-natural grassland. Plant and Soil 2000, 220, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Wardle, D.A. Herbivore-Mediated Linkages between Aboveground and Belowground Communities. Ecology 2003, 84, 2258–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahecha, L.; Gallego, L.A.; Peláez, F.J. Situación actual de la ganadería de carne en Colombia y alternativas para impulsar su competitividad y sostenibilidad. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias 2016, 15, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, 2013.

- Zhang, T.; Li, F.Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Bai, Z.; Suri, G.; Wang, Z. Disentangling the effects of animal defoliation, trampling, and excretion deposition on plant nutrient resorption in a semi-arid steppe: The predominant role of defoliation. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2022, 337, 108068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, B., G. Shuai, J. Zhang, and G.P. Robertson. “Yield Stability Analysis Reveals Sources of Large-Scale Nitrogen Loss from the US Midwest.” Scientific Reports 2019, 9(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Andriulo A., Sasal C., Améndola C., Rimatori, F. Impacto de un Sistema intensivo de producción de carne vacuna sobre algunas propiedades del suelo y del agua. Revista de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, 2003,32(3):27-56. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86432302.

- Yao, Z.; Shi, L.; He, Y.; Peng, C.; Lin, Z.; Hu, M.-a.; Yin, N.; Xu, H.; Zhang, D.; Shao, X. Grazing intensity, duration, and grassland type determine the relationship between soil microbial diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality in Chinese grasslands: A meta-analysis. Ecological Indicators 2023, 154, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, M.; Augustine, D.J. Large Herbivores Suppress Decomposer Abundance in a Semiarid Grazing Ecosystem. Ecology 2004, 85, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, R.; Acosta, J.A.; Bastida, F.; Domínguez, S.G.; Toledo, D.M.; Faz, A. Identification of sensitive indicators to assess the interrelationship between soil quality, management practices and human health. Soil 2015, 1, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Abellán, M.; Wic-Baena, C.; López-Serrano, F.R.; García-Morote, F.A.; Martínez-García, E.; Picazo, M.I.; Rubio, E.; Moreno-Ortego, J.L.; Bastida-López, F.; García-Izquierdo, C. A soil-quality index for soil from Mediterranean forests. European Journal of Soil Science 2019, 70, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akça, R.E. ; de Alba, S. ; Álvarez, A.G. et al., Soil atlas of Europe. Luxembourg : European Soil Bureau Network,. 128 p. 2005.

- Wic Baena, C.; Andrés-Abellán, M.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Martínez-García, E.; García-Morote, F.A.; Rubio, E.; López-Serrano, F.R. Thinning and recovery effects on soil properties in two sites of a Mediterranean forest, in Cuenca Mountain (South-eastern of Spain). Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 308, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedo, J.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Wic-Baena, C.; Andrés-Abellán, M.; de las Heras, J. Experimental site and season over-control the effect of Pinus halepensis in microbiological properties of soils under semiarid and dry conditions. Journal of Arid Environments 2015, 116, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.J.; Black, I.A. Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method. Soil Science 1934, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Total Nitrogen. In Methods of Soil Analysis; 1965; pp. 1149-1178.

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; 1983; pp. 403-430.

- Anderson, J.P.E. Soil Respiration. Methods of Soil Analysis Agronomy Monograph, 1982, 831-871.

- García, C., Gil, F., Hernández, T., & Trasar, C.. Técnicas de análisis de parámetros bioquímicos en suelos: Medida de actividades enzimáticas y biomasa microbiana; CEBAS-CSIC, Ed.; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Murcia. 2003.

- Tabatabai, M.A.a.B., J.M. Use of p-nitrophenol phosphate for the assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biology Biochemistry 1969, 1, 301-307. [CrossRef]

- Kandeler, E.; Stemmer, M.; Palli, S.; Gerzabek, M.H. Xylanase, Invertase and Urease Activity in Particle - Size Fractions of Soils. In Effect of Mineral-Organic-Microorganism Interactions on Soil and Freshwater Environments; Berthelin, J., Huang, P.M., Bollag, J.M., Andreux, F., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1999; pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Orea, D. Evaluación de impacto ambiental: un instrumento preventivo para la gestión ambiental 2º edición ed.; Mundi-Prensa, Ed.; Madrid, 2003.

- Qi, Y.; Darilek, J.L.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W.; Gu, Z. Evaluating soil quality indices in an agricultural region of Jiangsu Province, China. Geoderma 2009, 149, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymore, A.W. Model-Based Systems Engineering. . CRC Press, Boca Raton. 1993.

- Whittaker, C.W., Anderson, M.S. & Reitemeier R.F. . Liming soils: An Aid to Better Farming. . USDA Farmers Bulletins 1959, 2124.

- McDonald, S.E.; Badgery, W.; Clarendon, S.; Orgill, S.; Sinclair, K.; Meyer, R.; Butchart, D.B.; Eckard, R.; Rowlings, D.; Grace, P.; et al. Grazing management for soil carbon in Australia: A review. J Environ Manage 2023, 347, 119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, F.Y.; Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Baoyin, T. Enhancement of nutrient resorption efficiency increases plant production and helps maintain soil nutrients under summer grazing in a semi-arid steppe. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 292, 106840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, X.Z.; Wang, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Hou, F. Grazing-driven shifts in soil bacterial community structure and function in a typical steppe are mediated by additional N inputs. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; You, C.; Tan, B.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Effects of livestock grazing on the relationships between soil microbial community and soil carbon in grassland ecosystems. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 881, 163416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Saucedo, F.; García-Morote, F.A.; Picazo, M.; Wic, C.; Rubio, E.; López-Serrano, F.R.; Andrés-Abellán, M. Responses of Enzymatic and Microbiological Soil Properties to the Site Index and Age Gradients in Spanish Black Pine (Pinus nigra Arn ssp. salzmannii) Mediterranean Forests. Forests 2024, 15, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.S.; Gupta, V.K. Soil microbial biomass: A key soil driver in management of ecosystem functioning. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 634, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Abellán, M.; Picazo-Córdoba, M.I.; García-Saucedo, F.; Wic-Baena, C.; García-Morote, F.A.; Rubio-Caballero, E.; Moreno, J.L.; Bastida, F.; García, C.; López-Serrano, F.R. Application of a Soil Quality Index to a Mediterranean Mountain with Post-Fire Treatments. Forests 2023, 14, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, A.P. Soil Microbiology, Ecology and Biochemistry. ; press, A., Ed.; Colorado USA, 2015.

- Mahdi M., Al-Kaisi, B.L. Soil health and Intensification of Agroecosystems; Elsevier, M.M., Ed.; 2017; p. 418.

- Akhzari, D.; Pessarakli, M.; Ahandani, S. Effects of Grazing Intensity on Soil and Vegetation Properties in a Mediterranean Rangeland. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 2015, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, R.; Sapkota, R.P.; Parajuli, A.; Gautam, B. Impacts of Livestock Grazing on Vegetation and Soil in Lowland Grassland Ecosystem of Nepal. Journal of Institute of Science and Technology 2022, 27, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.S.; Holden, N.M. Indices for quantitative evaluation of soil quality under grassland management. Geoderma 2014, 230-231, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laurentiis, V.; Secchi, M.; Bos, U.; Horn, R.; Laurent, A.; Sala, S. Soil quality index: Exploring options for a comprehensive assessment of land use impacts in LCA. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 215, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedifar, M. Assessing alteration of soil quality, degradation, and resistance indices under different land uses through network and factor analysis. Catena 2023, 222, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).