Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

08 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

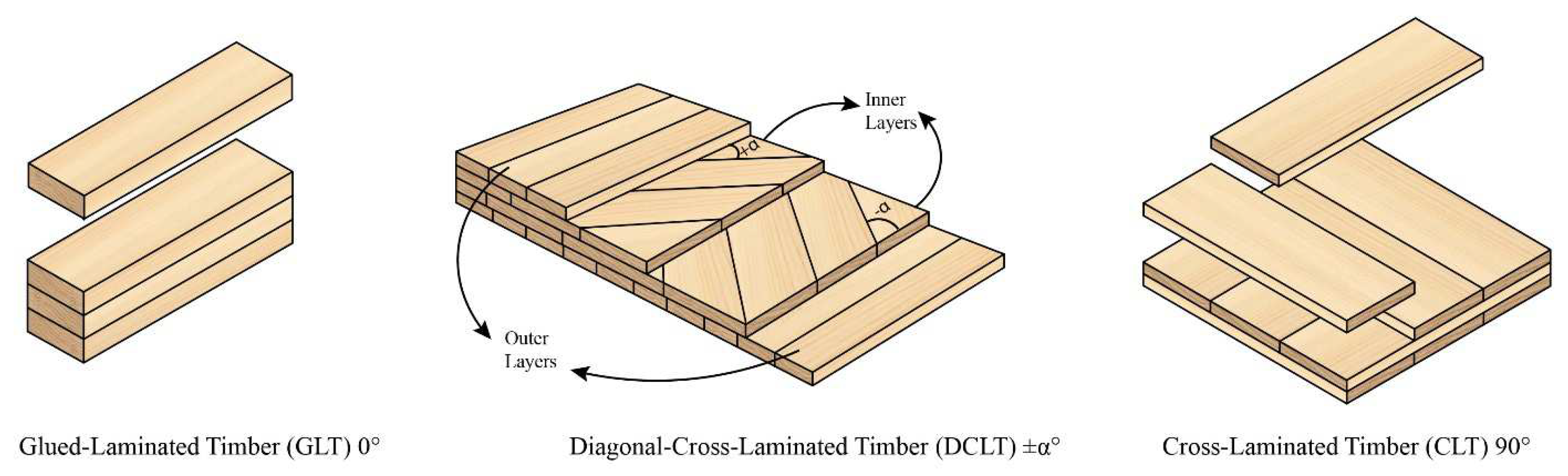

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

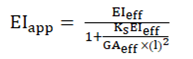

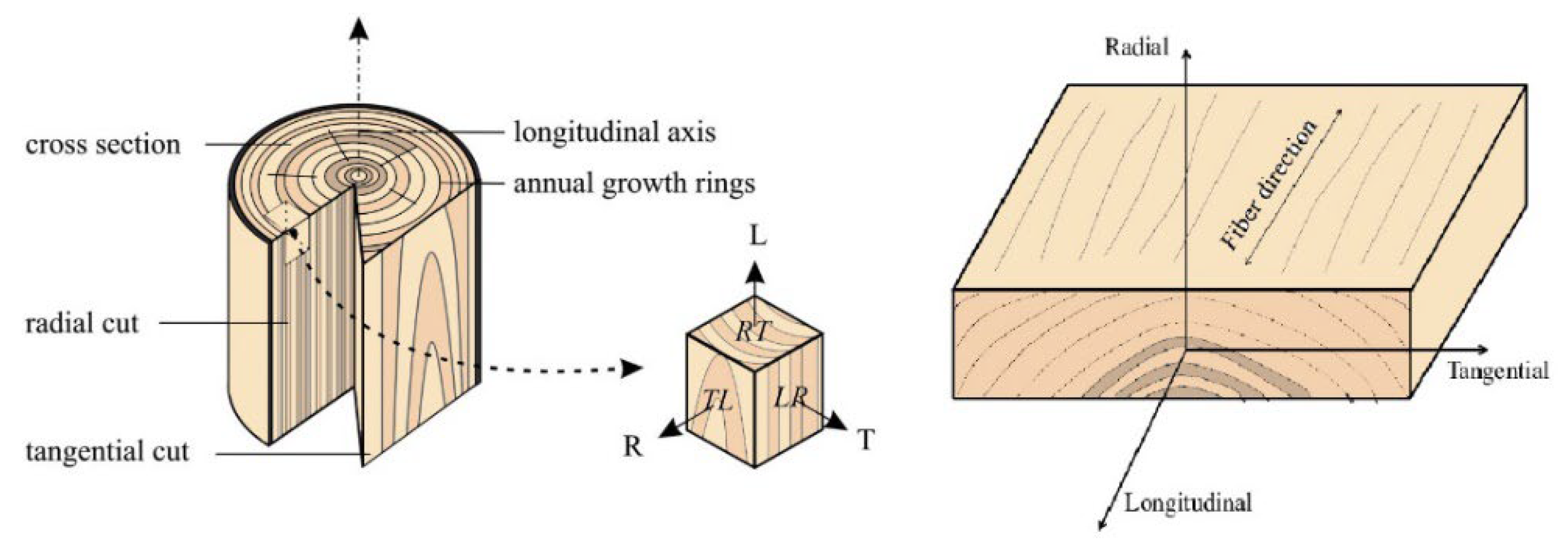

2.1. Theoretical Investigations

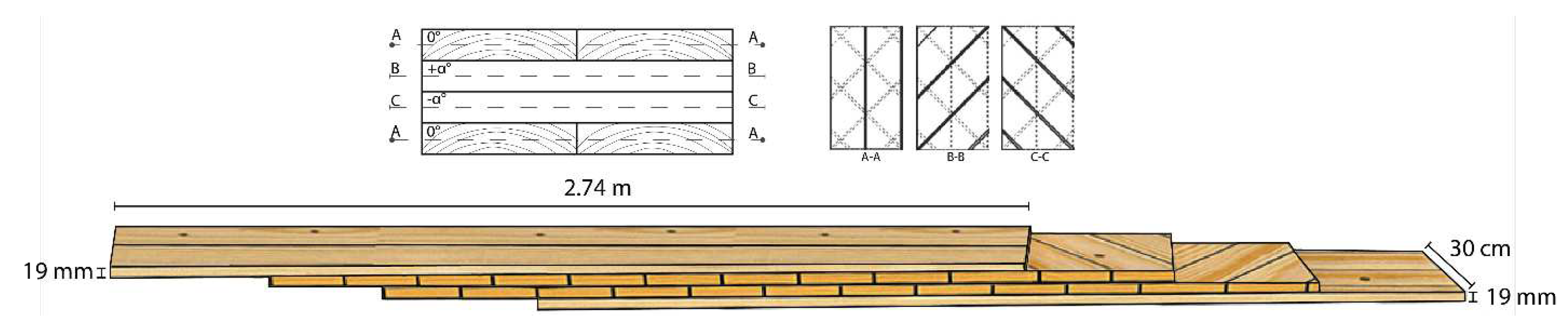

2.2. DCLT Panel Preparation

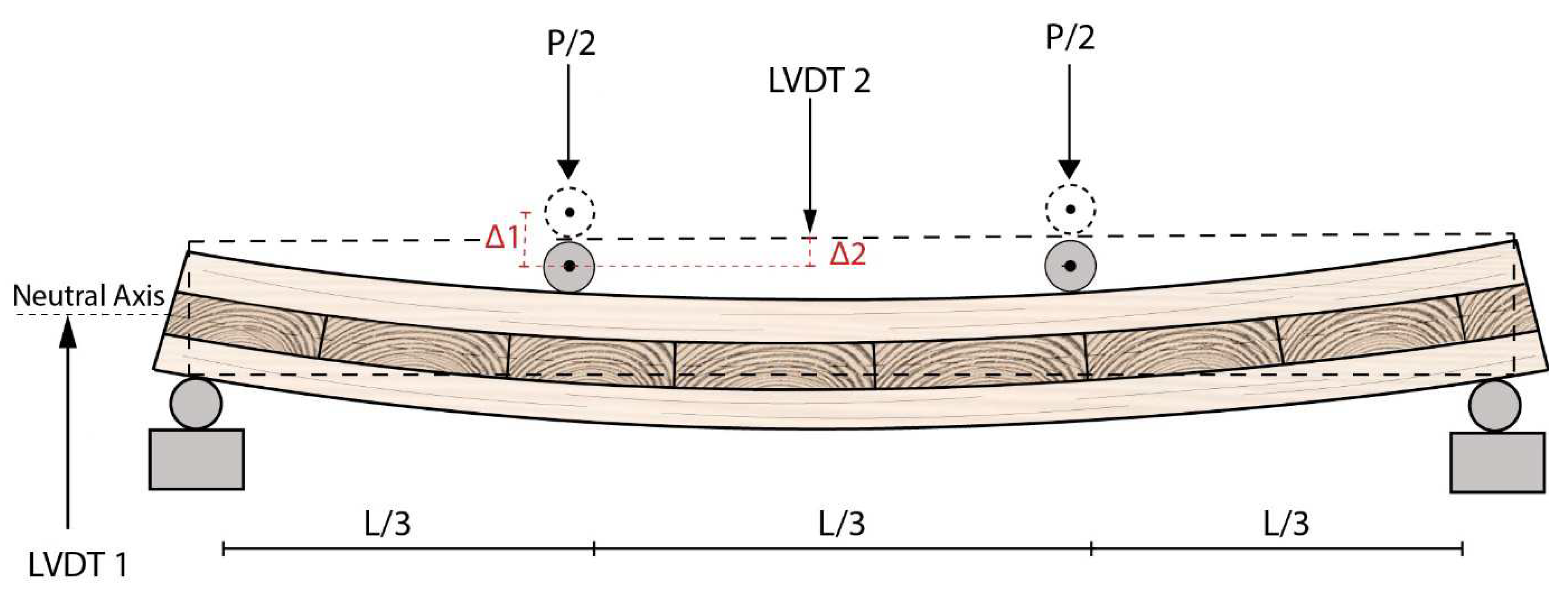

2.3. Third-point Bending Test

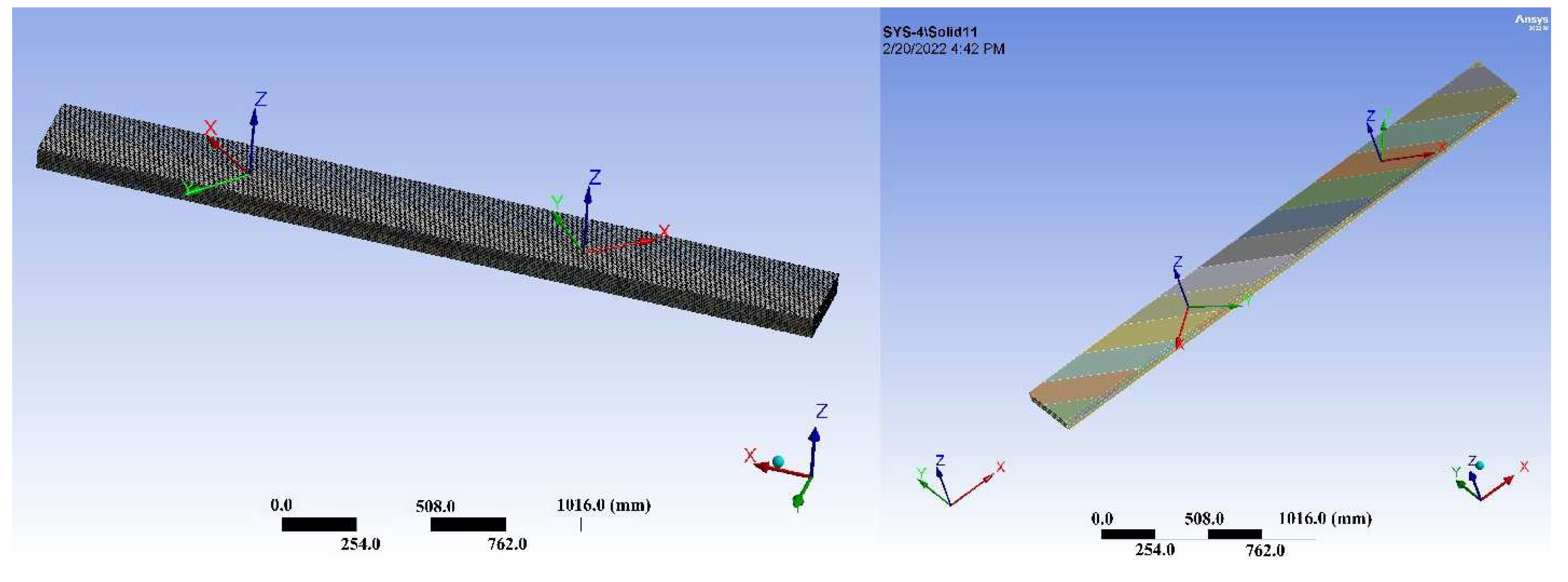

2.4. Finite Element Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hankinson’s Theory Results

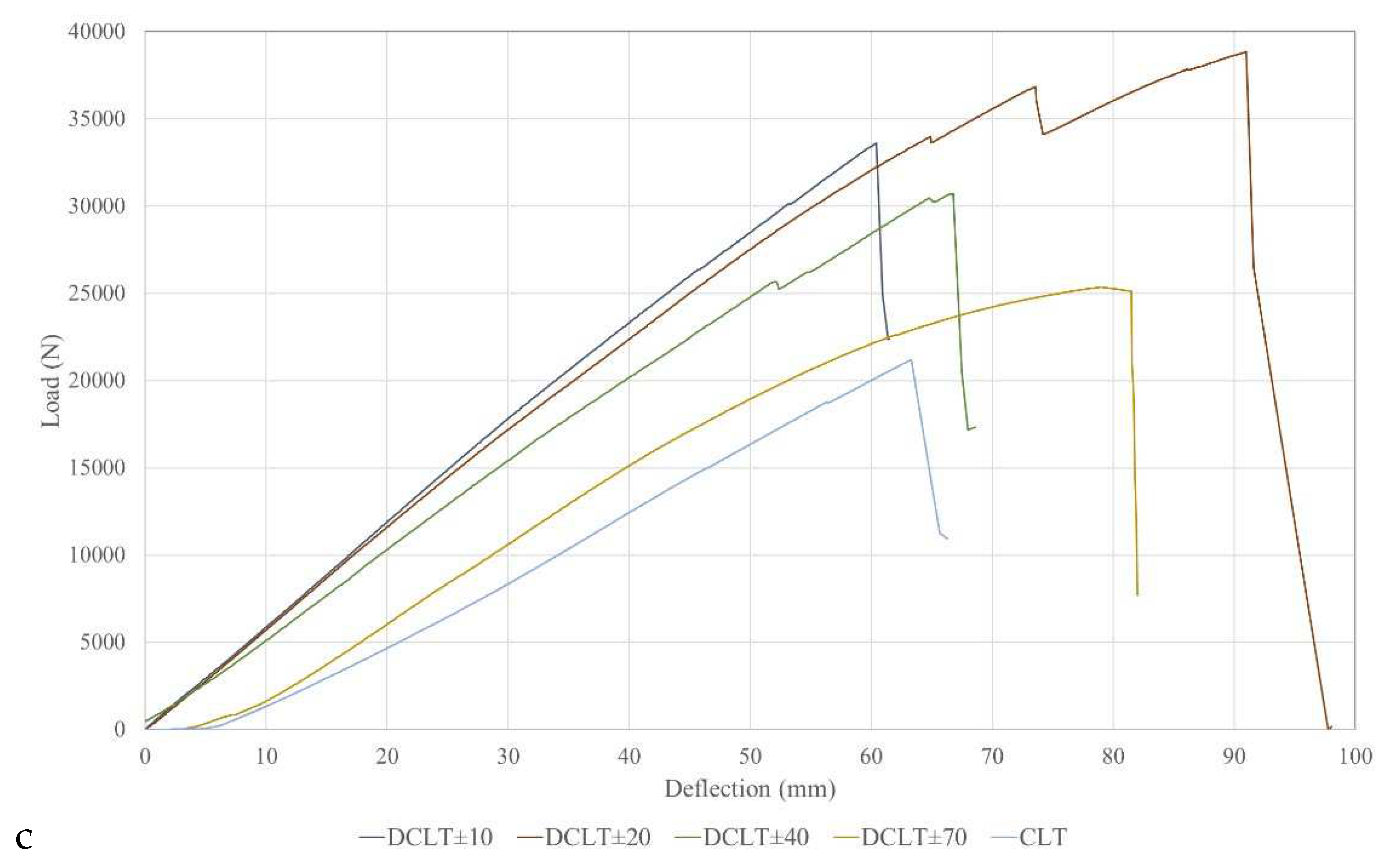

3.2. Third-point Bending Test Results

3.3. Finite Element Analysis

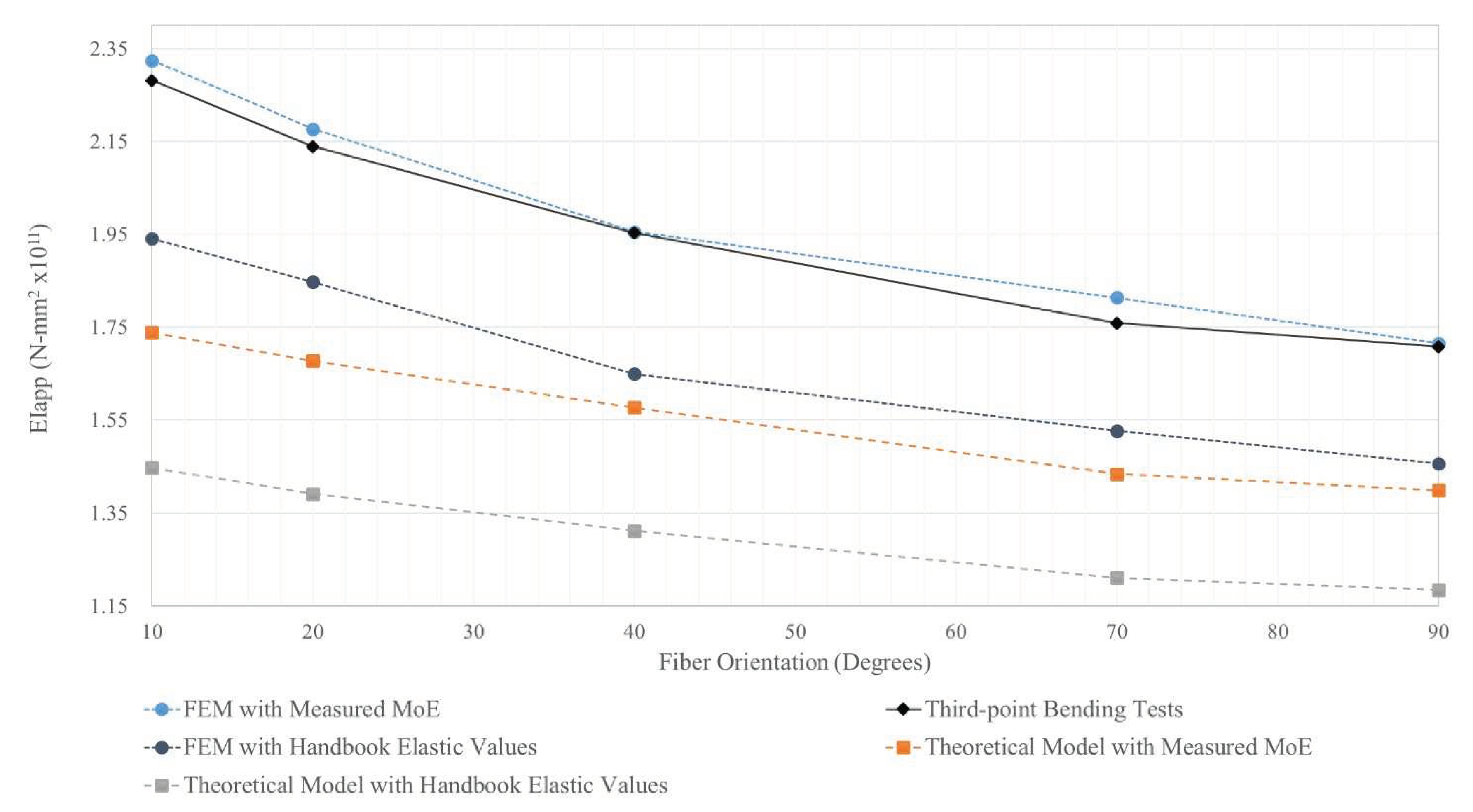

3.4. DCLT’s Bending Stiffness Comparison Between the Methods

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Bejtka, Cross (CLT) and diagonal (DLT) laminated timber as innovative material for beam elements, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT) Scientific Publishing, 2011.

- M. Arnold, P. Dietsch, R. Maderebner, S. Winter, Diagonal laminated timber—Experimental, analytical, and numerical studies on the torsional stiffness, Construction and Building Materials. 322 (2022) 126455. [CrossRef]

- S. Kurzinski, P. Crovella, W. Smith, Evaluating the Effect of Inner Layer Grain Orientation on Dimensional Stability in Hybrid Species Cross-and Diagonal-Cross-laminated Timber (DCLT), Mass Timber Construction Journal, 6 (2023) 11-16.

- D. Buck, X.A. Wang, O. Hagman, A. Gustafsson, Bending properties of Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) with a 45° alternating layer configuration, BioResources. 11 (2016) 4633–4644. [CrossRef]

- Bahmanzad, P.L. Clouston, S.R. Arwade, A.C. Schreyer, Shear Properties of Symmetric Angle-Ply Cross-Laminated Timber Panels, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering. 32 (2020) 04020254. [CrossRef]

- M. Yoshito, K. Hiroe, T. Yukari, N. Yasue, Relationship between the Strength and Grain Orientation of Wood: Examination and modification of the Hankinson’s Formula, The University of Tokyo Graduate School of Agriculture and Life Sciences Exercise Forest. 93 (1995) 1–5.

- Bahmanzad, P.L. Clouston, S.R. Arwade, A.C. Schreyer, Shear Properties of Eastern Hemlock with Respect to Fiber Orientation for Use in Cross Laminated Timber, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering. 32 (2020) 04020165. [CrossRef]

- L. Franzoni, A. Lebée, F. Lyon, G. Foret, Influence of orientation and number of layers on the elastic response and failure modes on CLT floors: modeling and parameter studies, European Journal of Wood and Wood Products. 74 (2016) 671–684. [CrossRef]

- H. Kreuzinger, Platten, Scheiben und Schalen, Bauen Mit Holz. 101 (1999) 34–39.

- E. Karacebeyli, B. Douglas, CLT Handbook - US Edition, FPInnovations and Binational Softwood Lumber Council, Point-Claire, Quebec, 2013.

- S. Kurzinski, P.L. Crovella, Predicting the Strength and Serviceability Performance of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Panels Fabricated with High-Density Hardwood, WCTE 2021, Santiago, Chile, 2021.

- American Lumber Standard Committee (ALSC), Northeastern Lumber Manufacturers Association, Standard Grading Rules for Northeastern Lumber, Northeastern Lumber Manufacturers Association, Maine, USA., 2021.

- American National Standard Institute, ANSI-APA/PRG 320 - Standard for Performance-Rated Cross-Laminated Timber, APA – The Engineered Wood Association, New York, NY, 2019.

- R.S. Shoberg, Engineering Fundamentals of Threaded Fastener Design and Analysis, RS Technologies. (2000) 1–39. Available online: http://www.hexagon.de/rs/engineering fundamentals.pdf.

- American Society for Testing and Materials Committee, ASTM D198- 15, (2015).

- National Instruments Corporation, LabVIEW, Austin, Texas, USA. (2021).

- ANSYS Inc, ANSYS® Workbench, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, USA. (2022).

- Forest Products Laboratory, USDA Wood handbook—Wood as an engineering material. General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190., Madison, WI: U.S, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation., Microsoft Excel, Redmond, Washington, USA. (2021).

| Species | Poisson’s ratio | Shear Modulus (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Specific Gravity | ||||||

| νlt | νlr | νtr | Glr | Glt | Grt | Et | Er | El | SG | |

| Black locust (Wood Handbook MoE) |

0.286 | 0.220 | 0.196 | 1,301 | 899 | 274 | 862 | 1,697 | 14,134 | 0.69 |

| Eastern White Pine (Wood Handbook MoE) |

0.233 | 0.223 | 0.220 | 624 | 592 | 76 | 467 | 766 | 8,549 | 0.35 |

| Black locust (Measured MoE) |

0.286 | 0.220 | 0.196 | 1,587 | 1,096 | 334 | 1,051 | 2,070 | 17,236 | 0.69 |

| Eastern White Pine (Measured MoE) |

0.233 | 0.223 | 0.220 | 548 | 520 | 67 | 411 | 673 | 7,515 | 0.35 |

| Group | Bounding Box Diagonal Size (cm) | Average Surface Area (cm2) | Minimum Edge Length Size (cm) | Numbers of Nodes | Number of Elements |

| DCLT ±10 | 276.93 | 803.67 | 0.96 | 2,111,626 | 413,142 |

| DCLT ±20 | 276.93 | 584.96 | 0.12 | 1,983,392 | 387,159 |

| DCLT ±40 | 277.08 | 383.61 | 0.43 | 1,466,501 | 283,758 |

| DCLT ±70 | 276.93 | 322.12 | 1.90 | 388,696 | 66,528 |

| CLT | 276.93 | 307.03 | 1.90 | 913,030 | 174,240 |

| EIApp (N-mm2x1011) |

|||||

| 10° | 20° | 40° | 70° | 90° | |

| Handbook Values | 1.45 | 1.39 | 1.31 | 1.21 | 1.18 |

| MoE of the Layers | 1.74 | 1.68 | 1.58 | 1.43 | 1.40 |

| % Increase to CLT | 23% | 18% | 12% | 3% | -- |

| EIApp. (N-mm2x1011) |

Grain Orientation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10° | 20° | 40° | 70° | 90° | |

| Mean | 2.28 | 2.14 | 1.95 | 1.76 | 1.71 |

| % Increase to CLT | 33% | 25% | 14% | 3% | -- |

| CV | 2.62 | 5.93 | 3.37 | 7.42 | -- |

| Min | 2.23 | 2.00 | 1.90 | 1.67 | 1.71 |

| Max | 2.35 | 2.26 | 2.02 | 1.91 | 1.71 |

| EIApp (N-mm2x1011) |

Grain Orientation | ||||

| 10° | 20° | 40° | 70° | 90° | |

| Handbook Values | 1.94 | 1.85 | 1.65 | 1.53 | 1.46 |

| MoE of the Layers | 2.32 | 2.18 | 1.96 | 1.81 | 1.72 |

| % Increase to CLT | 33% | 26% | 13% | 6% | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).