1. Introduction

Due to climate change, resilience in agriculture is becoming increasingly important, such as soil improvement measures for water retention during heavy rainfall events and droughts [1, 2]. Conventionally composted substrates show limited usable effects on soil improvement under aspects of climate change and soil improvement [3, 4]. At the same time, the efficient use of natural resources is becoming increasingly important due to competing uses and rising demand, as illustrated by the European Action Plan for the Circular Economy, among others [

5].

Because of growing interest in circular economy and with the amendment of the EU Fertiliser Products Regulation in 2019, which now takes fertilisers based on recycled and organic material into account, material by-products from various sectors are increasingly being taken into account in research and development. These include the recycling of sewage sludge and the production of fertilisers from by-products of pulp and paper production. [

6]. This article deals with the use of biomass residues from the agricultural industry and landscape conservation for production of plant - based bio char as a further approach to the use of material side streams. By using high-quality bio char, soil-improving effects [

7] can be achieved on the one hand, and approaches for the robust sequester of carbon and thus the reduction of greenhouse gases [

8] can be combined on the other. Various industrial pyrolysis systems are available for production of plant carbon from residues [

9]. Thermo Catalytic Reforming (TCR) results in molar H/C ratios < 0,6 at plant based biochar. According to the current state of science high content of stable carbon leads to the expectation of a high soil persistence and thus a long term carbon sequestration. For biochar from TCR no significant decomposition by soil organisms to methane has to be expected [

10].

The main objective of the present work is to assess the usability of such bio char compared to the conventional use of compost substrates for soil improvement. In addition to the availability of raw materials for plant charcoal production, legal aspects of fertiliser approval are considered, and insight is given into the initial results of a long-term trial that has been started to investigate soil amelioration measures using plant charcoal from the TCR process. In a comparative balance of mass and energy streams the production of compost substrates are compared with those of plant based biochar in order to provide an initial comparison of the two production methods, using plant residues in meaning of circular economy. The advantages and risks that has to be taken into account in the production and use of such bio char are presented according to the current state of knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

The legal framework for the use of materials and methods for soil improvement is presented in a European and regional context. Existing authorisation possibilities are listed and approaches to solving still open legal requirements are named.

Using Geo Information System (QGIS3.18) the material flows of forestry, agricultural and landscaping residues were identified in the region of the "InterPyro" real laboratory and site assessments for the construction of plants for the production of plant carbon were carried out. For this purpose, geo-remote sensing data of land use systems from the European CORINE Land Cover 2018 [

11] were extended in a GIS by characteristic values of net primary production of the CLC categories and the total biomass reproduction rate in the Börde district was determined [12: 13; 14; 15]. Furthermore, the biogenic material quantities already circulating in the economic cycle from the sectors agriculture, municipal waste management, green space management, forestry and bioenergy were researched and validated by expert interviews. The spatial analysis was supplemented by the transport routes of the green waste collections, in a transport radius within 20 km.

Plant based biowaste was used to produce biochar on a technicum scale TCR-plant. The biochar was compounded 1:1 by mass with digestate from biogas production to prepare “loaded biochar” for comparative soil improvement trials in agricultural test-field Gatersleben-Strenzfeld. Initial effects on soil properties in first year of a planned long time field for high-quality biochar where compared to known effects during application of substrates from composted biowaste to identify possible further potentials fostering circular economy from production of compost and biochar.

3. Results

3.1. Regulatory Framework

3.1.1. European and National Guidelines and Regulations

Table 1.

Overview of relevannt europoean and national guidlines.

Table 1.

Overview of relevannt europoean and national guidlines.

| regulation |

background |

scope |

content |

| EU-Düngeprodukteverordnung (EU) 2019/1009 |

European regulatory framework on the sale and use of fertilizers in all EU member states |

European Union |

Determination of the requirements to be met by fertilizer products marketed in the EU. EU fertilizer products must fulfill the requirements of the relevant product function category (PFC) and component material category (CMC) and be labeled in accordance with the labeling requirements of the Regulation. |

| Düngemittelverordnung (DÜMV) |

Placing on the market of fertilisers, soil additives, growing media and plant additives |

Germany |

Determination of approved fertilizer types as well as definition of their minimum concentrations, components, contaminant limits and method of production |

| Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz (KrWG) |

Production and marketing of biochar as a product based on biomass |

Germany |

In §5 KrWG definition of requirements to be fulfilled in order to reach the end of the waste status. |

| Bundes-Immissionsschutzgesetz (BImSchG) |

Installation and operation of a pyrolysis system |

Germany |

Determination of regulatory requirements for the construction and operation of systems based on throughput capacity and type of feedstocks. |

The European Fertiliser Products Regulation governs the supply and marketing of fertilizer products on the European internal market. With the amendment of the EU-Düngeprodukteverordnung in 2019 (VO (EU) 2019/1009), fertilizers produced from recycled or organic material were included, thus opening the way for the use of other plant residues besides wood waste. The EU-Düngeprodukteverordnung includes requirements to be fulfilled for marketing with CE labeling regarding:

3.1.2. German Regulatory Framework

In order to ensure that products made from biomass can be produced and marketed in Germany regardless of their form of use, §5 of the german Kreislaufwirtschaftsgesetz (KrWG) defines the following requirements for the end of waste status:

Designation of a purpose for the resulting substance (e.g., the use of biochar as a soil additive).

existing demand for the product e.g a real existing market

fulfillment of all technical as well as legal requirements for the intended use

exclusion of harmful effects on humans or the environment by the product.

In case of further treatment of feedstock biomasses, additional regulations such as the BioAbfV and the AbfKlärV come in to count. For the construction and operation of a pyrolysis system, the german Bundes-Immissionsschutzgesetz (BImSchG) defines regulatory requirements based on the throughput capacity and type of feedstock.

At the national level, the Düngemittelverordnung (DÜMV), which regulates the application of fertilizers, soil additives, substrates and plant aids, applies across Germany. The DÜMV includes:

types of fertilizers permitted in Germany

the definition of minimum contents, constituents, pollutant limits

specifications on the method of production

Within the framework of the DÜMV, biochar is currently neither listed as a fertilizer or as a soil additive. The registration of products into the German fertilizer list is undertaken by a scientific committee for fertilization issues, which is appointed by the Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (BMEL). The list of fertilizers approved in Germany and published in constant updates within the DÜMV receives special attention in the agricultural sector. This was confirmed by the interviews and workshops that took place within the project "InterPyro" and the exchange of experiences with farmers, who pointed out the regular look at the updated fertilizer list as agricultural practice.

3.1.3. Certificates for Biochar Used in Agriculture

Existing and used quality certificates provide practical examples of compliance with qualities and evidence of pollution levels in the biochar.

The EBC is a voluntary industry standard in Europe, developed by the Ithaka Institute and managed by Carbon Standard International (CSI). The guidelines of the certificate set requirements for the input materials used, the characteristics of the biochar, the pyrolysis technology as well as the workplace and consumer protection. There are certification levels depending on the intended use of the biochar. The EBC-Agro and EBC-AgroBio certification levels fulfill the requirements for fertilizers defined by the EU-Düngeprodukteverordnung.

The IBC is a voluntary certification program, currently limited to the U.S. and Canada, developed by the International Biochar Initiative. Within the program, standards such as maximum concentrations for potentially toxic elements and compounds are prescribed for biochar applied to soil.

Currently, the marketing of biochar for soil improvement purposes is restricted primarily by the nationally applicable DÜMV, which excludes biochar as a fertilizer and soil additive. This regulatory barrier can be avoided by manufacturers by referring to the EU-Düngeprodukteverordnung. In order for farmers to benefit from the positive effects of biochar, binding quality standards for biochar used in agriculture should be established in addition to the adaptation of the national regulatory framework. The existing certification programs can be used for this purpose. An example of linking the regulatory framework to existing certifications is already taking place in Switzerland. Due to the high standards of the EBC, the certification of biochar with certification level EBC-AgroBio provides the conditions for the use of biochar as a soil conditioner in Switzerland.

A detailed overview of the legal framework can be found in the WissensWiki, created as part of the project "InterPyro" and constantly updated at

https://websites.fraunhofer.de/innolab/index.php/TCR_Pyrolyse.

3.2. Material Flow Analysis

Due to its natural endowment with the highest soil value figures, the Börde district is intensively agricultural, with 73% of the land used for crop production. The net primary production of biomass in this land use system alone is 1,090 kilotonnes per year. A further 551 kilotonnes of biomass are reproduced annually in the forest land use system. This results in an estimated carbon gain (40% in agricultural products, 46% in wood source) of 660 kilotonnes (436 kt C from agrucultural products plus 230 kt C from forest). This corresponds to an annual photosynthetic capacity of 2.42 million tonnes of CO2-Eq.

3.2.1. Recycling Paths of the Residual Material

Research into the recycling paths revealed that in the past years since 2018, 20,000 tonnes of damaged wood - just under 10% of the natural reproduction capacity - has been produced annually can be brought in relation to unplanned climate change, which leaves the region as cheap firewood and is presumably traded on the global timber market with an unknown destination. The carbon bound in the wood escapes into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide through oxidation and additionally fuels global warming. The energetic use of damaged wood also leads to environmental impacts, as does the open rotting of landscape maintenance material. Large quantities of the carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere by plant growth and the carbon stored in the biomass continue to be subject to decomposition processes or the generation of e.g. fine dust. Of the plant production in agriculture, at least 40% of the biomass is accounted for by-product straw, which usually remains on the field after harvesting and is only rarely used in small quantities, for instance as stable bedding. Green cuttings from landscape conservation are collected by the municipal service in annual quantities of 6000 t, of which 4700 t are burnt in a wood chip plant in Magdeburg. Another 320 tonnes of green waste per year is collected by private businesses and 1785 tonnes by municipalities and is composted.

3.3. First Evaluation of a Long-Term Trial on the Use of Vegetable Carbon

At the Bernburg-Strenzfeld agricultural trial site of the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences, existing soils were prepared using “loaded biochar” in form of compound from biochar with digestate of biogas-production and pure digestate from production of biogas as basis for defined crop rotations.

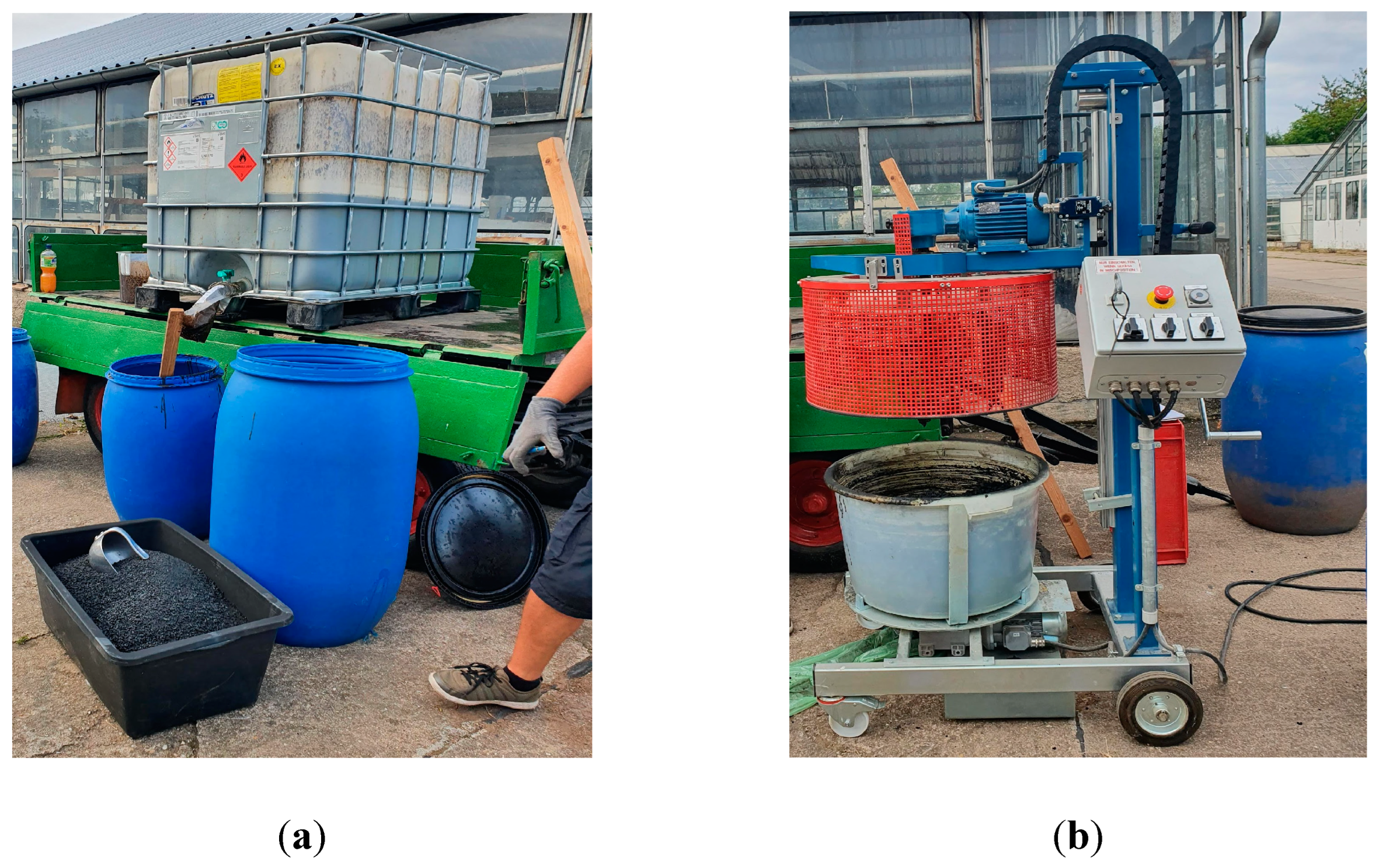

3.3.1. Preparation for the Agricultural Field Trial

The high quality charcoal for field trial was produced from dead wood by thermocatalytic reforming. As deliverer of nutritions a digestate from procuction of bio gas was chosen, comparable to mist. Following established standards the used two single components where characterised (

Table 2).

After being provided at the agricultural test site, the biochar was loaded with digestate from production of biogas in ratio 1:1 (by mass) for 8 days (

Figure 1).

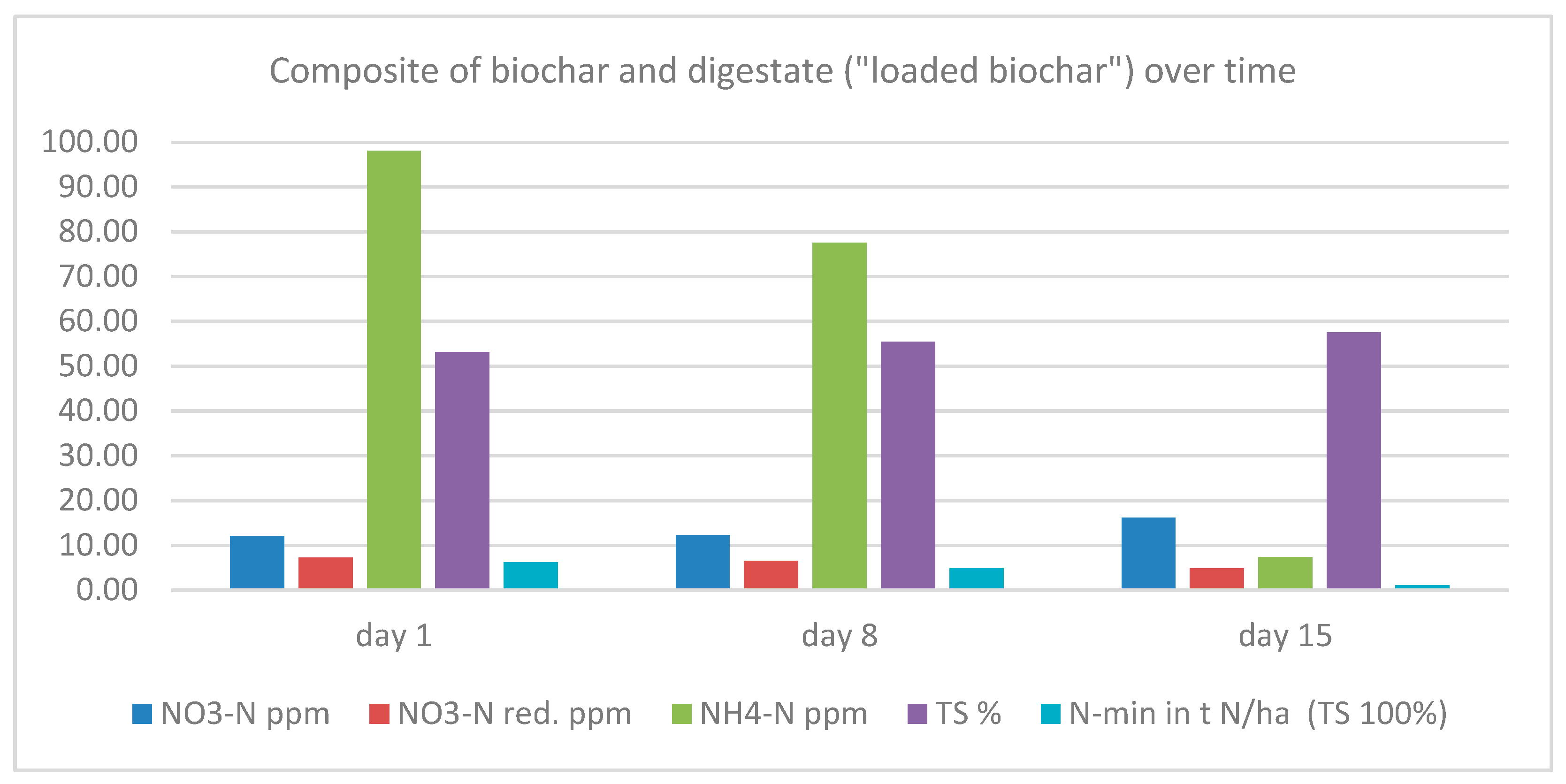

When both components, biochar and digestate from production of biogas will be mixed and cured to a composite on one side the Ammonia-N will be absorbed.

This effects a extreme lowering of emsission from NH3 and slowing the formation of NO3-N, which leads in significant reduced washout and denitrification when the substrate is used as a soil improver. Also the typical smell of fermentation substrate (digestate) is complete absent after a curing time of 1 till two weeks.

3.3.2. Implementation of the Agricultural Field Trial

For the agricultural field trial, a baseline determination of the soil parameters was carried out on the open agricultural test field Bernburg-Strenzfeld in July 2021. The application of the plant charcoal loaded digestate and the pure digestate took place in August 2021 in the root horizon of the comparison areas.

Soil preparation was carried out by incorporating the two substrates at the level of the root horizon 15 cm below the surface using a heavy cultivator in two passes. The charcoal loaded with digestate was applied at a mass/area ratio of 46t/ha, while the comparison plot was applied at the same mass ratio of 15t/ha digestate of fermentation residue.

In October field tests where begun with intercrop of yellow mustard was seeded at a depth of 3 cm, with seed emergence 10 days later. Further determinations of soil parameters were carried out in November 2021, February and March 2022. After the intercrop of yellow mustard, silage maize was sown on the plots in April 2022, with assessment in July 2022. The harvest of the silage maize in September 22 was followed by the sowing of winter wheat.

3.3.3. Observation and Evaluation of Emergence in the Agricultural Field Trial

The field trial takes place on a test field at the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences, at the Bernburg-Strenzfeld site, the soil is a chernosem. Topsoil is 40 cm thick and lies on a subsoil of loess with a thickness of 80 cm on limestone. Due to the test field being classified as fertile (soil typical for the Börde region), effects in humus formation and nutrient replenishment are expected in the usual, consumptive crop rotations of silage maize and winter wheat. In addition to a normal soil, plots were prepared with fermentation residue and fermentation residue + charcoal to “loaded charcoal”.

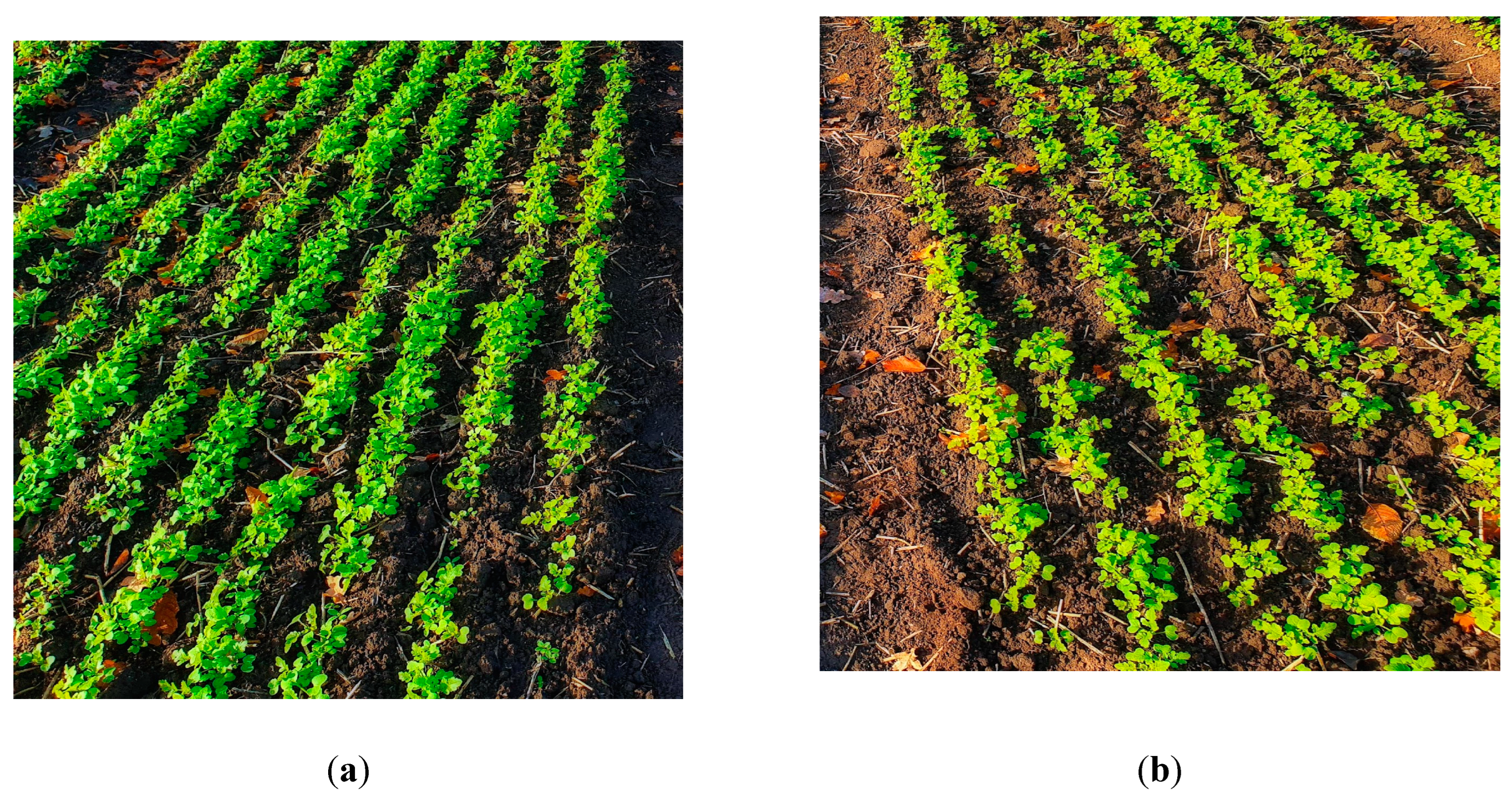

Figure 3.

The plant growth in the first year of the agricultural field trial to evaluate soil improvement with the use of plant carbon is shown: (a) high-quality plant carbon loaded with nutrients from digestate based of fermentation residues from bioga-production is showing dense rows in the intercrop and a richer green colour (b) unimproved digestate of fermentation residues from biogas-production as substrate showing lower dense rows in the seed emergence of the intercrop and a less green colour.

Figure 3.

The plant growth in the first year of the agricultural field trial to evaluate soil improvement with the use of plant carbon is shown: (a) high-quality plant carbon loaded with nutrients from digestate based of fermentation residues from bioga-production is showing dense rows in the intercrop and a richer green colour (b) unimproved digestate of fermentation residues from biogas-production as substrate showing lower dense rows in the seed emergence of the intercrop and a less green colour.

In the course of the field trial, missing areas from the plant growth have grown together over time, to a large extent, so that a subjective visual assessment in the course of the trial showed hardly any differences.

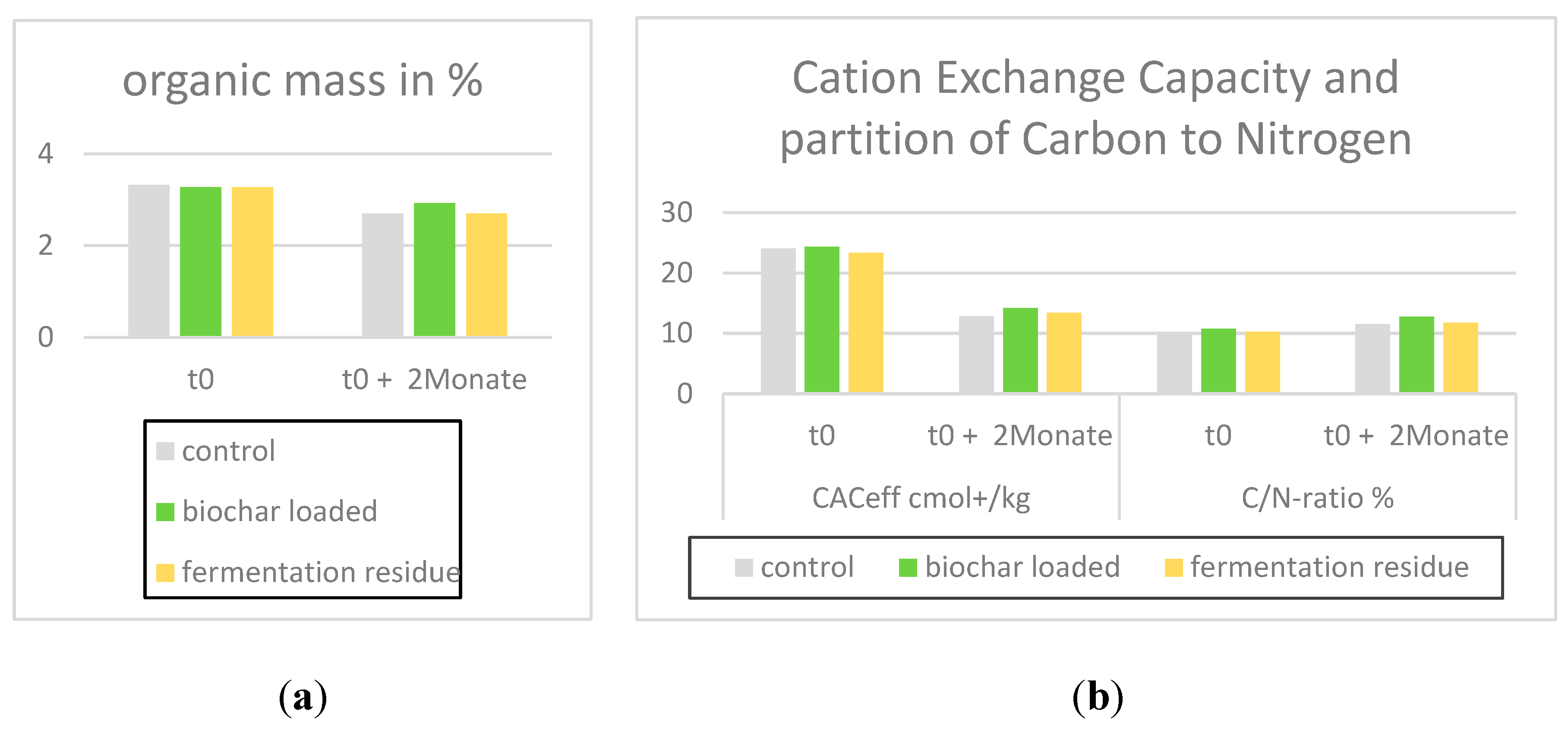

As

Figure 4 shows, the use of high-quality plant charcoal that was loaded with organic nutrients does not have a significant effect on the currently available series of measurements of soil parameters. The measured soil parameters correspond to the objective optical assessments of the seed emergence of the intercrop yellow mustard, see

Figure 3.

3.3.4. Comparative Assessment of Compost and “Loaded Biochar” from Biowaste

For a comparative representation of the material and energy flows for the production of compost in a closed composting plant, a data set from the secondary database Ecoinvent 3.9 was used, see

Table 3. Input of 2 kg biowaste is resulting in 1 kg compost.

The material and energy flows for the production of high-quality biochar based on biowaste and loaded with digestate from biogas production were used from an expert interview with Fraunhofer UMSICHT in 2022. Input of 1.5 kg biowaste to TCR pyrolysis at 450°C in stage one and 600°C in stage two results in 0.5 kg biochar and is compounded with 0.5 kg digestate from bio gas production. One should note the significant energetic by product heat and electricity from TCR. In experiments the production of biochar from biowaste in form of plant waste from municipal green space maintenance was carried out successful by Fraunhofer UMSICHT. During such experiments for biowaste from green cuts caloric value of 14 MJ/kg dry biowaste was measured, what is only slight decrease compared to deadwood. For drying biowaste thermal by product from TCR is used.

Table 4.

Material and energy flows for TCR pyrolysis and loading of the plant charcoal with digestate, . according to expert interview with Fraunhofer UMSICHT 2022. Inputmaterial is 1.5 kg biowaste and 0.5 kg fermentation residue, to produce 1 kg of “Loaded biochar”from 0.5 kg biochar and 0.5 kg digestate.

Table 4.

Material and energy flows for TCR pyrolysis and loading of the plant charcoal with digestate, . according to expert interview with Fraunhofer UMSICHT 2022. Inputmaterial is 1.5 kg biowaste and 0.5 kg fermentation residue, to produce 1 kg of “Loaded biochar”from 0.5 kg biochar and 0.5 kg digestate.

| input |

input and unit |

activity |

output |

product and unit |

| biowaste |

1.5 kg |

Drying biowaste, TCR pyrolysis at 450°C and 600°C |

„loaded biochar“ |

1 kg |

| fermentation residue |

0.5 kg |

Stirring and shelf time 14d |

| heat |

0.7 kWh |

|

|

1.2 kWh |

| electricity |

0.07 kWh |

|

|

1 kWh |

| diesel |

0 |

|

|

0 |

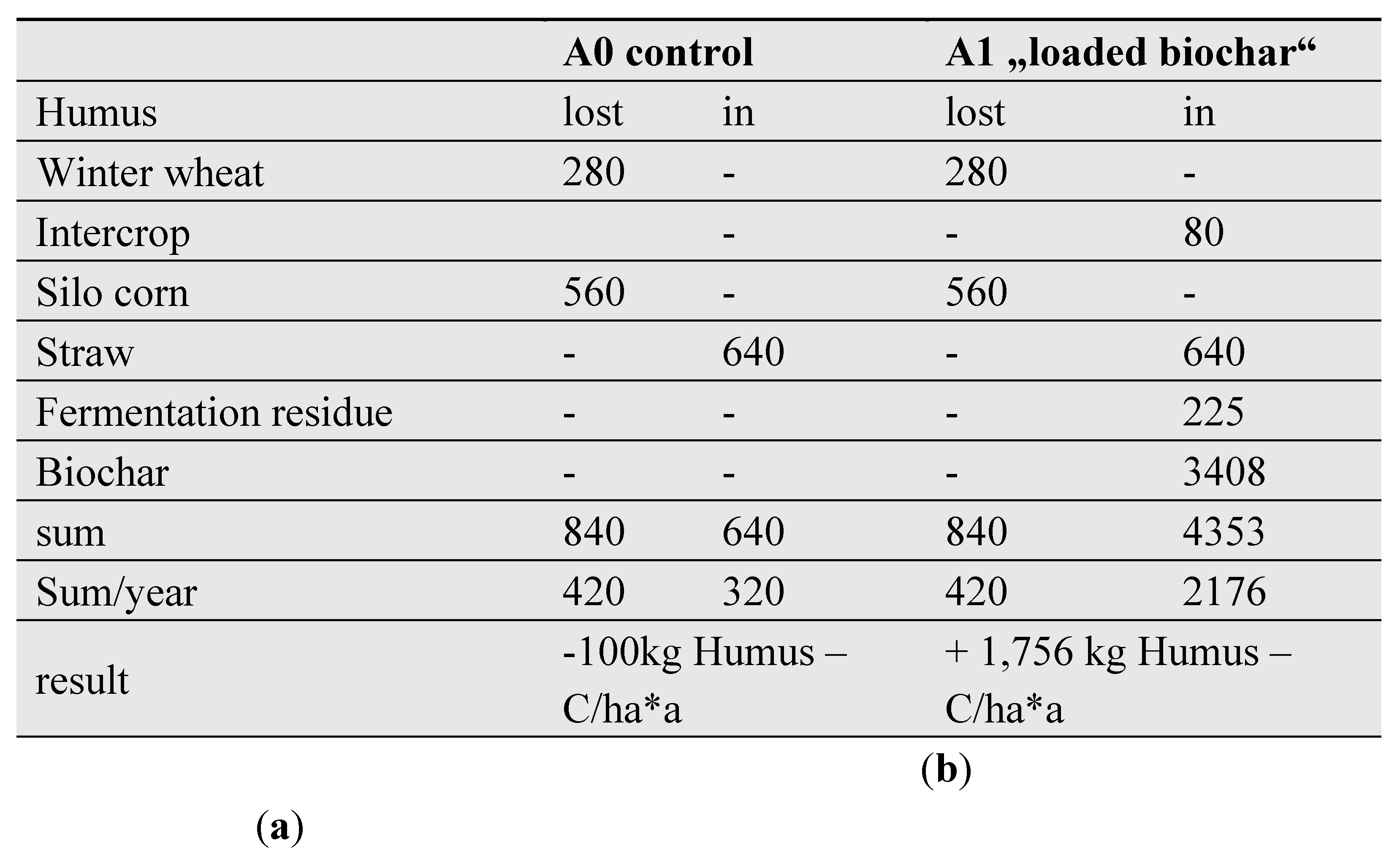

3.3.5. Comparative Presentation of the Substrates in Their Soil Effectiveness

Soil samples show that the control variant after a crop rotation of winter wheat and silage maize has a requirement of 100 kg humus C/ha*a supply, while the soils on the plots supplied with high-quality bio char, loaded with organic fertiliser from fermentation residues after the crop rotation of winter wheat, intercrop yellow mustard followed by silage maize show a significant surplus of 1.756 kg humus C/ha*a.

Irrespective of the time spent on sowing and cultivating the intercrop yellow mustard, the significant increase in humus shows the positive effectiveness of high-grade bio char loaded with organic fertiliser, even on loess soil, under cultivation of a soil-consuming crop rotation.

Figure 5.

Shown are the hummubilance of: (a) Crop rotation on control plot without charcoal or digestate; (b) Crop rotation under application of Biochar loaded with digestate.

Figure 5.

Shown are the hummubilance of: (a) Crop rotation on control plot without charcoal or digestate; (b) Crop rotation under application of Biochar loaded with digestate.

4. Discussion

In field trials on good soils (loess soil), the “loaded biochar” obtained from pyrolysis in thermocatalytic reforming and compounded with digestate from biogas production /1:1 mass %) shows a significant increase in humus build-up compared to unprepared soil in control, during first year of long time field trial. Also no negative effects can be observed in soil samples perpared with “loaded biochar” in comparison to soil prepared with digestate from fermentation residues, as representant for compost, nor soil without preparation as control. Neither negative effects on nutrient availability nor on soil persistence of the charcoal used. An improved water availability with the use of biochar is assumed because of observed robust seed emerging in field trial. The energetic by-products from pyrolysis processed as thermocatalytic reforming (TCR) are significant and can be economically utilised, for example to run TCR energetic sufficient and feeding waste heat into district heating networks, if a suitable location for the pyrolysis utility is chosen.

Regional value creation is higher with biogas production than compared to conventional composting, as energetic by-products at least in form of district heat, can be utilised.

In the short time horizon available so far, soil improvement effects have been observed that are not worse than the soil improvement effects described in the literature when using compost substrates. Since the field trial was carried out on a loess subsoil, the improvement of soil parameters achieved is worth mentioning, because according to the literature, soil improvement by plant charcoal usually occurs to a measurable extent in tropical regions, on poor soils.

Over the longer time horizon, a CO2 sink is conceivable due to the stable O/C ratio of high-quality plant carbon. On the basis of the currently available measurement reports of the soil parameters, it is not possible to make a prediction on the soil persistence of the substrate for the use of the plant carbon from the TCR process in subsoil loess. However, participation in the CO2 certificate trade can already be integrated into the value chain of plant carbon via the voluntary European Biochar Certificate of the Ithaka Institute Switzerland. The amendment of the European Fertiliser Ordinance, which now also includes vegetable carbon as a soil additive, makes it possible to plan economically for the use of vegetable carbon, also from other feedstocks.

In future, the long-term time horizon with regard to soil improvement with the use of high quality biochar is necessary in order to observe erroneous conclusions, e.g. the decomposition of carbon by soil organisms, and thus to exclude harmful climate gas emissions. In addition to deadwood and green waste, other feedstock sources should be included in this study, in particular the by-products straw from crop production and fermentation residues from biomethane production. In this way untapped potential for urgently needed removal of CO2 from the atmosphere can be activated and value creation improved at the regional level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Video S1: soil preparation using bio char at the citizen science-site in Hecklingen, Saxony-Anhalt.

Author Contributions

"Concept, S.W.; Method, S.W. and M.S. and J.D.; Data, S.W. and M.S. and J.D.; Writing - Creation of the original draft, S.W.; Writing - Review and Editing, A.H. and S.W.; Visualisation, S.W. and J.D.; Funding, S.W. For an explanation of the terms, please refer to the CRediT taxonomy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was carried out within the framework of the project "REGION.innovativ – InterPyro: Intercommunal application of pyrolysis technology with biomass waste as a feedstock for CO2-negative energy production and soil improvement in rural areas" and was financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the funding code 033L240E.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for funding the research work within the funding programme "REGION.innovativ" and the x anonymous reviewers for their constructive advice.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3-169.

- 2. Smith, P., Nkem, J.; Calvin, K.; Campbell, D.; Cherubini, F.; Grassi,G.; Korotkov, V.; Hoang, A.L.; Lwasa, S.; McElwee, P.; Nkonya, E.; Saigusa, N.; Soussana, J.-F.; Taboada, M.A. Interlinkages Between Desertification, Land Degradation, Food Security and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes: Synergies, Trade-offs and Integrated Response Options. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Shukla, P.R. .; Skea, J.; Calvo Buendia, E.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D. C.; Zhai, P. ; Slade, R.; Connors, S.; van Diemen, R.; Ferrat, M.; Haughey, E.; Luz, S.; Neogi, S.; Pathak, M. ; Petzold, J.; Portugal Pereira, J.; Vyas, P.; Huntley, E.; Kissick, K.; Belkacemi, M.; Malley, J. (eds.): Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK and New York, 2019; pp. 551-672.

- Knappe, F.; Vogt, R.; Lazar, S.; Höke, S. Optimierung der Verwertung organischer Abfälle. 31/2012. Umweltbundesamt, Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2012.

- Lazar, S.; Höke, S.; Knappe, F.; Vogt, R. Optimierung der Verwertung organischer Abfälle Materialband „Wirkungsanalyse Boden“. 32/2012. Umweltbundesamt, Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2012.

- Euopäische Kommission. Ein neuer Aktionsplan für die Kreislaufwirtschaft Für ein saubereres und wettbewerbsfähigeres Europa; Brussels, Belgium 2020.

- Experiences of UPM's and Yara's recycled fertiliser project taken to good use. Available online: https://www.upm.com/about-us/for-media/releases/2019/01/experiences-of-upms-and-yaras-recycled-fertiliser-project-taken-to-good-use/ (acessed on 14.09.2023).

- Radloff, S. Modellgestützte Bewertung der Nutzung von Biokohle als Bodenzusatz in der Landwirtschaft. Academic doctor degree, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany, 18.04.2016.

- Terlouw, T.; Bauer,C.; Rosa, L.; Mazzotti, M. Life cycle assessment of carbon dioxide removal technologies: a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci., 2021, 14, pp. 1701-1721.

- Bulach, W.; Dehoust, G.; Möck, A.; Oetjen-Dehne, R.; Kaiser, F.; Radermacher, J.; Lichtl, M. Ermittlung von Kriterien für hochwertige anderweitige Verwertungsmöglichkeiten von Bioabfällen. Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2021.

- Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E.; Neugschwandtner, R.W.; Konvalina, P.; Kopecký, M.; Moudrý, J.; Perná, K.; Murindangabo, Y.T. The Impact of Pyrolysis Temperature on Biochar Properties and Its Effects on Soil Hydrological Properties. Sustainability 2022, 14, pp. 1-15.

- Corine Land Cover (2018) h ttps://gdz.bkg.bund.de/index.php/default/digitale-geodaten/digitale-landschaftsmodelle/corine-land-cover-5-ha-stand-2018-clc5-2018.html, Access 2023/12/06.

- Begon, M.; Townsend, C.; Harper, J.; Sauer, K.-P. Ökologie Heidelberg: Spektrum Akad. Verlag (Spektrum-Lehrbuch) 1998.

- Heinrich, D.; Hergt, M.; Fahnert, R.; Fahnert, R. dtv-Atlas Ökologie. 5., durchges. Aufl., Orig.-Ausg. München: Dt. Taschenbuch-Verl. (dtv, 3228) 2002.

- Kuttler, W.; Steinecke, K.; Fischer, I. Handbuch zur Ökologie. Berlin: Analytica (Handbuch zur angewandten Umweltforschung, 1) 1993.

- Smith, T. M.; Smith, R. L.; Kratochwil, A. Ökologie. Dt. Ausg., 6., aktualisierte Aufl. [der amerikan. Ausg.]. München: Pearson Studium (bio - Biologie) 2009.

- Dinkel F.; Zschokke M.; Schleiss K. Treatment of biowaste, industrial composting. GLO. ecoinvent 3.9.1.

- Schleiss, K. Treatment of biowaste, industrial composting. GLO, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Symeonidis, A. Treatment of biowaste, open dump. GLO, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Simons, A. Transport, freight, lorry 16-32 metric ton, EURO6 - RER - transport, freight, lorry 16-32 metric ton, EURO6, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Valsasina, S. Market for transport, freight, lorry 16-32 metric ton, EURO6 - RER - transport, freight, lorry 16-32 metric ton, EURO6, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Heck, T. Mini CHP plant production, components for heat only - CH - mini CHP plant, components for heat only, CH, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Heil, A. Composting facility construction, open - CH - composting facility, open, CH, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

- Kellenberger, D. Building construction, hall, wood construction - CH - building, hall, wood construction, CH, ecoinvent version 3.9.1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).