1. Introduction

Platycodon (

Platycodon grandiflorus), commonly known as balloon flower, is a perennial herb belonging to the family Campanulaceae. It is also referred to as "ling-danghua" in Chinese and is known as "Hulundanchagan" in Mongolian. The roots of this plant are extensively used in traditional Chinese medicine, while its above-ground parts are consumed as a vegetable. It is primarily distributed across various provinces in Northeast, North, East, and Central China, as well as Guangdong, northern Guangxi, Guizhou, southeastern Yunnan (Mengzi, Yanshan, Wenshan), Sichuan (east of Pingwu, Liangshan), Shaanxi, and other regions. It is also found in parts of Korea, Japan, and southern regions of the Russian Far East and East Siberia. Platycodon typically thrives in sunny grasslands and shrublands at elevations below 2000 meters and is less commonly found in forest understories [

1]. Due to its high medicinal and food value, the market demand for Platycodon is increasing, and artificial cultivation has become the main way to supply the market.

Medical research and analysis show that Platycodon contains a variety of active chemical components, mostly comprising Platycodon total saponins [

2]. In addition, Platycodon also contains polysaccharides, flavonoids, amino acids, fatty oils, fatty acids, inorganic elements, vitamins and volatile oils [

3], and a large amount of unsaturated fatty acids. Therefore, Platycodon has high medicinal and edible value. Studies have shown that Platycodon saponin has weight-loss activity [

4]. Platycodon also has the effects of reducing tobacco toxicity and controlling the increase in blood alcohol content in the human body [

5]. Therefore, Platycodon can also be processed into thin strips to make cold dishes, and some can also be made into pickles, cans, and other products; it is a very popular functional health food [

6]. The demand for medicinal and health food production of Platycodon has increased, and Platycodon has become an important crop in agricultural production. At the same time, it will bring greater economic benefits to the development of Platycodon planting areas. Therefore, research on Platycodon has attracted widespread attention.

The limited availability of land resources suitable for cultivating authentic medicinal herbs is influenced by factors such as soil conditions and planting restrictions. Continuous cropping or replanting is common in this context [

7]. Crop rotation is a beneficial measure to overcome the obstacles of continuous cropping; however, the intercropping duration for medicinal plants is often lengthy. For instance, Scrophularia ningpoensis requires an interval of 3–4 years before it can be planted again in the same soil. Ginseng and American ginseng may need more than 30 years before being replanted at the same location [

8]. Intercropping with Salvia miltiorrhiza can take as long as 8 years [

9]. These extended intercropping intervals significantly impact the stability of the supply of traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. Therefore, finding methods to alleviate the challenges of continuous cropping is crucial for the sustainable development of the traditional Chinese medicine industry.

However, the issue of continuous Platycodon cropping seriously hampers the sustainable development of its cultivation. Previous studies have shown that the continuous cultivation of Platycodon for 2 years results in a significantly decreased yield and quality, while continuous cultivation for 4–5 years may lead to severe root rot, causing a reduction in yield of over 50% or even complete crop failure [

10]. Despite attempts to address obstacles to continuous cropping through pest control, disease management, and cultivation techniques, the results remain unsatisfactory [

11]. Moreover, the allelopathic effects of Platycodon leaves have been characterized, revealing their strong allelopathic inhibitory effect on the growth of lettuce seedlings and hypocotyls of the test plants [

12]. Considering the decline in emergence rates and growth damage observed in replanted crops, it is reasonable to speculate that Platycodon may induce autotoxicity through the release of allelopathic substances.

Allelopathy is a phenomenon in which plants influence the growth of surrounding plants (or microorganisms) by releasing natural compounds, resulting in inhibitory or stimulatory effects [

13]. This phenomenon was first named "allelopathy" by German botanist Hans Molisch in 1937, and the compounds causing allelopathy are referred to as allelochemicals. Allelochemicals are primarily released via three pathways: volatilization from the aboveground parts of plants, leaching or shedding from plant debris, and root exudation. They affect not only the growth of neighboring plants, but may also impact the plant’s own community or its own growth [

14].

Continuous cropping poses a significant challenge in the cultivation of medicinal herbs, and over 40% of medicinal herbs are artificially cultivation in China. Among the cultivated varieties, root-based medicinal herbs make up approximately 70% and obstacles to continuous cropping are prevalent in their cultivation processes [

15,

16]. Medicinal herbs such as

Rehmannia glutinosa,

Pinellia ternata,

Pseudostellaria heterophylla,

Panax ginseng,

Lilium brownii,

Panax pseudoginseng,

Panax quinquefolius, and

Salvia miltiorrhiza all face issues related to continuous cropping obstacles [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The phrase “continuous cropping obstacles” refers to the phenomenon whereby consecutive planting in the same plot of land results in a decline in seedling emergence and growth inhibition [

25]. The main causes include an increase in soil-borne pathogens or the exacerbation of pests and diseases [

26], impaired absorption of soil nutrients, deterioration of soil physicochemical properties, and allelopathy [

27,

28]. Autotoxicity caused by allelopathic substances released by plants is a crucial factor contributing to the formation of obstacles to continuous cropping. Numerous studies have shown a close correlation between the health of medicinal plants under continuous cropping conditions and the content of root exudates, especially by observing the accumulation of organic acids in continuously cropped soil. These organic acids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, coumarins, flavonoids, and other compounds have been identified as allelopathic substances [

29]. Some root exudates induce the production of reactive oxygen species, disrupt root tip cells, and affect the levels of chlorophyll and osmoregulatory substances, thus inhibiting the growth of roots and shoots. The allelopathic inhibitory feedback exhibited by roots is more pronounced than that of stems and leaves, which may be a primary mechanism through which allelopathic substances influence the content of active components, especially underground parts, in medicinal plants [

30]. Since Platycodon is a type of root-based medicinal herb, the allelopathic effects of root exudates are crucial elements that need to be measured and analyzed when examining the causes of obstacles to continuous cropping.

The allelopathic activity of the entire Platycodon plant and its various parts with respect to its seed germination and seedling growth were investigated, and strong allelopathic inhibitory effects were observed. This suggests that the continuous cropping obstacles associated with Platycodon may arise from autotoxicity caused by allelochemicals released by the plant itself [

31]. During the process of continuous cropping obstacle formation, root exudates are also one of the important influencing factors. Therefore, studying the impact of root exudates on plant growth is a key aspect in elucidating the reasons behind continuous cropping obstacles [

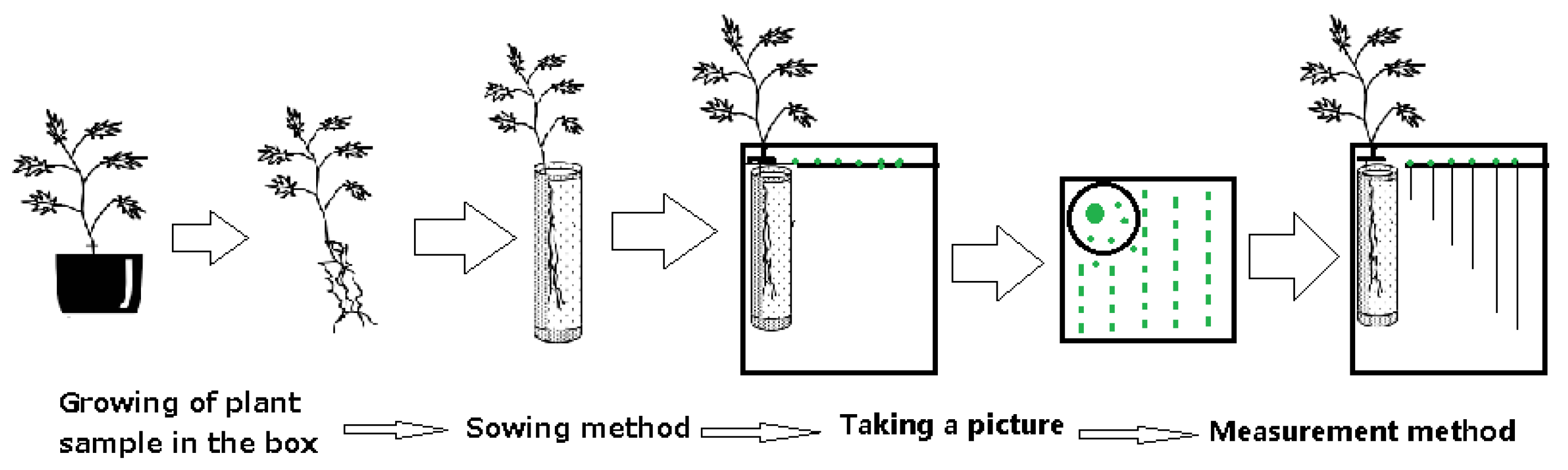

32]. However, there is currently more research on the impact of aboveground allelochemicals on seedling growth and germination, while studies on the allelopathic effects of the root exudates of Platycodon are relatively scarce. In this study, the allelopathic effects of Platycodon roots and their exudates was initially measured to explore the potential role of the roots in the formation of obstacles to continuous cropping. Subsequently, the allelopathic effects of Platycodon root exudates were comprehensively assessed using the Plant Box method (Figure 2) to better infer the impacts resulting from their contribution to continuous cropping obstacles. Finally, to understand the allelopathic effects of the various parts and root exudates of Platycodon, activated carbon, an effective material in controlling allelopathic inhibition in crops such as asparagus and peach trees was introduced to test its effects on the absorption of Platycodon self-released allelopathic substances.

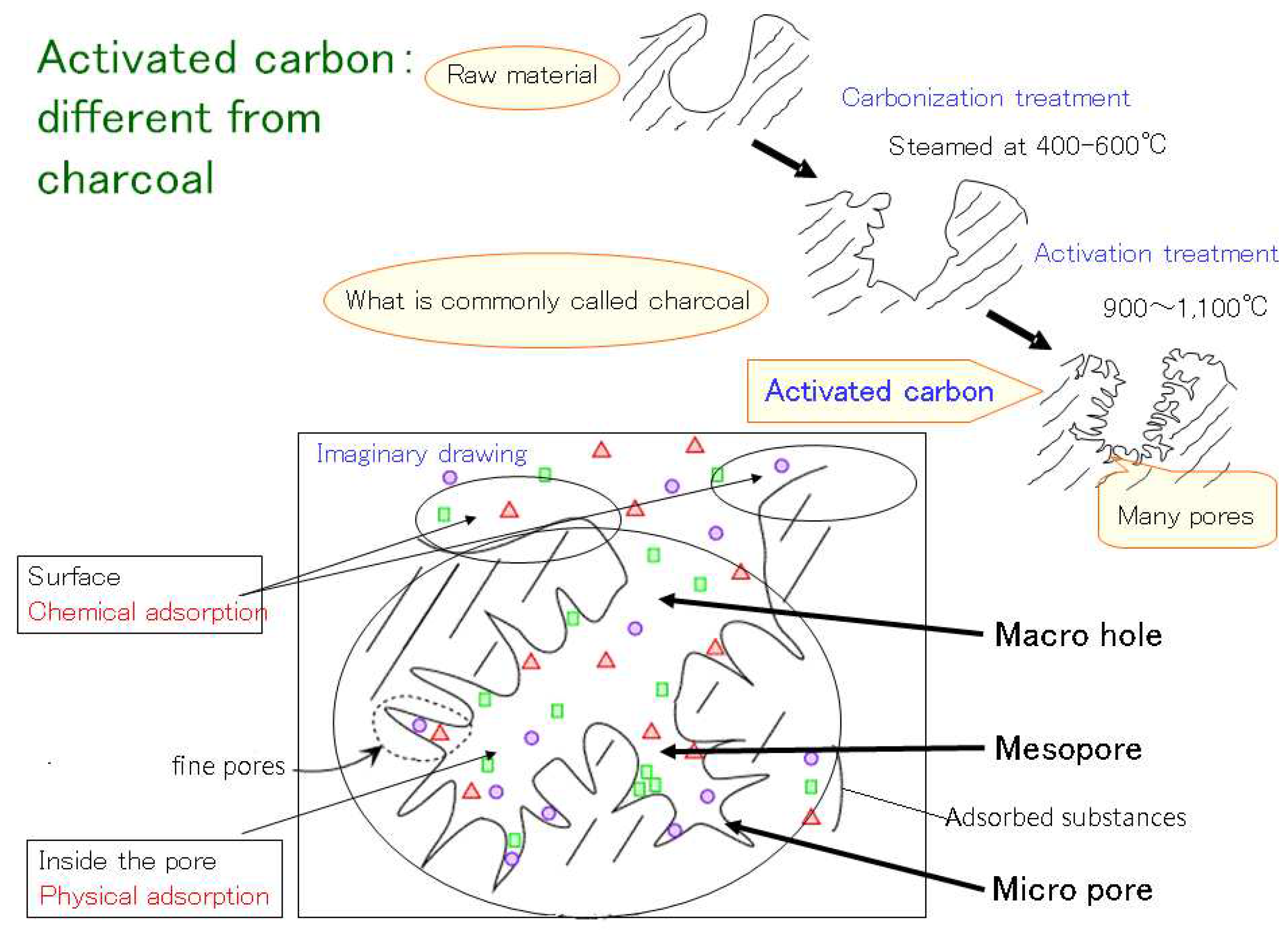

The definition of activated carbon is not precise, and it is generally described as a substance with a large surface area and strong adsorption capacity that is mainly composed of carbon [

33]. Activated carbon has various applications, such as serving as a deodorant in refrigerators and an adsorbent in industries. Its raw materials mainly include wood charcoal, coconut shells, and brown coal. In the agricultural field, the use of activated carbon has been studied for several types of plants, and some have even been put into practical use in Japan. For example, although there are studies on the role of activated carbon in alleviating continuous cropping obstacles in crops such as cucumber, beans, sugar beets, and asparagus [

34,

35,

36,

37], research on such obstacles related to Platycodon is relatively limited. Therefore, the aim of this study was to test the absorptive effects of activated carbon on the allelopathic effects of the various parts and root exudates of Platycodon toward establishing a scientific basis for the study of materials that alleviate obstacles to continuous cropping. This study aimed to demonstrate the role of potential autotoxicity of Platycodon from the perspective of allelopathy. Additionally, This study aims to incorporate activated carbon agents to alleviate continuous cropping obstacles in Chinese Platycodon cultivation.

3. Results

3.1. Bioassay Tests for Assessing the Allelopathic Activity of Platycodon Parts at Different Ages

First assessment (after 60 days): The results revealed that among the various parts of Platycodon, the leaves exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect upon the first assessment. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the inhibition rates of the lettuce radicals and hypocotyls were 73.9% and 56.2%, respectively. The next-highest inhibitory effect was shown by the root (41.2%, 43.1%) and the lowest by the stem (22.7%, 5.4%), respectively. At a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, the leaves also caused the highest reduction in radicals and hypocotyls (88.1%, 61.1%), roots (70.9%, 52.6%), and stem (77.2%, 54.2%), respectively.

Second assessment (after 90 days): At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the inhibition percentages, from the highest to the lowest, were as follows: leaves (79.8%, 65.0%), roots (42.6%, 35.9%), and stem (46.8%, 32.4%) in radicals and hypocotyls, respectively. At 50 mg/10 mL, the leaves (92.4%, 34.9%), stem (77.5%, 60.0%), and roots (57.4%, 40.0%) continued to display inhibitory effects. Additionally, during the flowering season of Platycodon, the flower part also demonstrated inhibitory effects, with inhibition rates of 67.4% and 49.0% at 10 mg/10 mL and 81.2% and 59.7% at 50 mg/10 mL. Third assessment (after 150 days): At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the inhibition percentages in radicals and hypocotyls, respectively, were as follows: leaves (84.4%, 64.2%), roots (76.4%, 68.9%), and stem (69.5%, 54.8%). At 50 mg/10 mL, the leaves caused (95.4%, 86.9%), roots (92.3%, 82.6%), and stem (30.5%, 45.3%). Overall, according to the three assessments, at a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the average inhibition rates for the leaves and roots were 79.4% and 53.4%, respectively, and at a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, the average inhibition rates for the leaves and stem were 91.9% and 78.3%, respectively (

Table 1).

These results indicate that various parts of Platycodon at different ages possess a significant allelopathic inhibitory effect on the growth and germination of lettuce seedlings. The greatest inhibitory effect was cause by the leaves at different ages. The inhibition rates increased with as the concentration of Platycodon residues increased.

3.2. Effect of Activated Carbon on the Adsorption of Allelopathic Substances from Various Platycodon Components

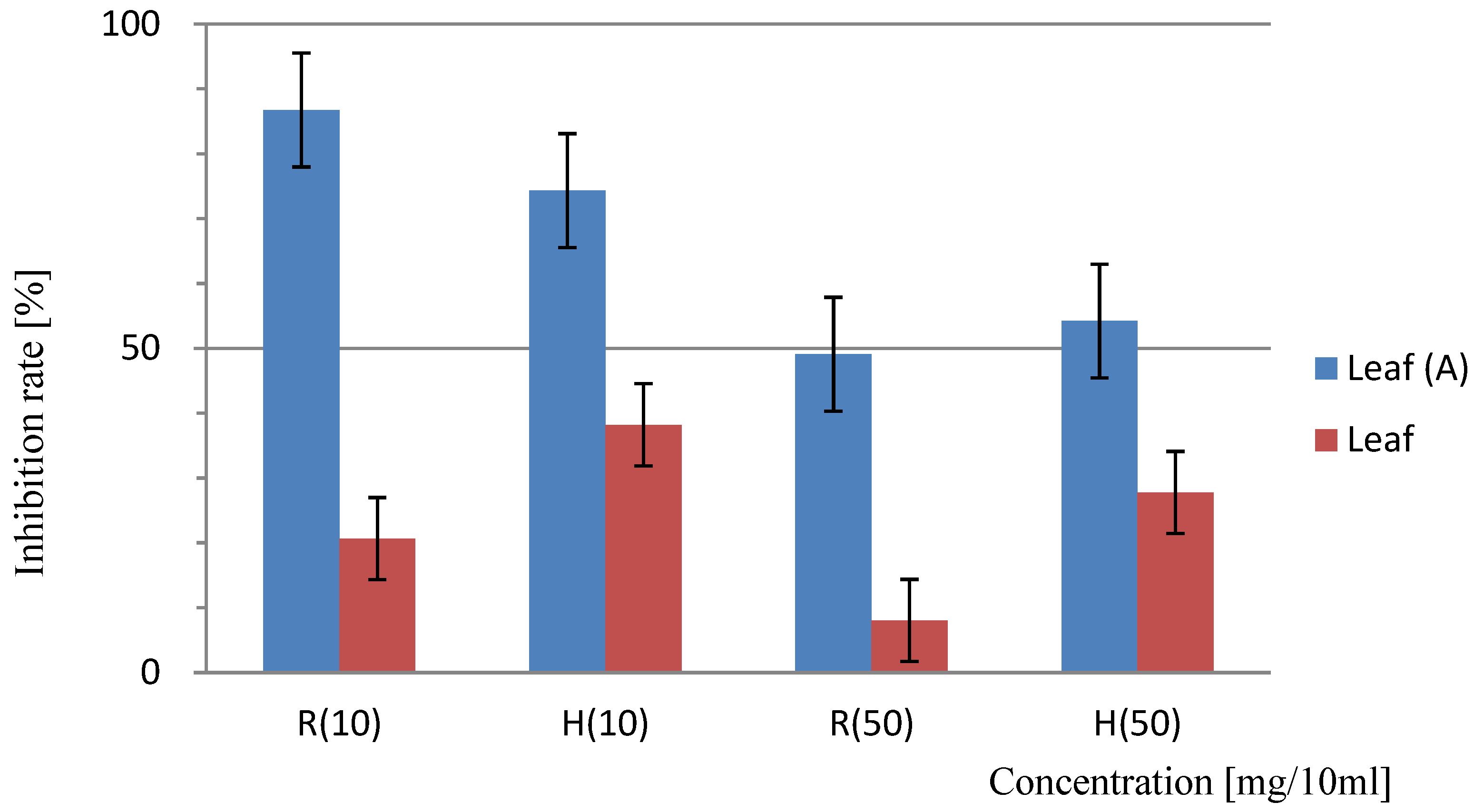

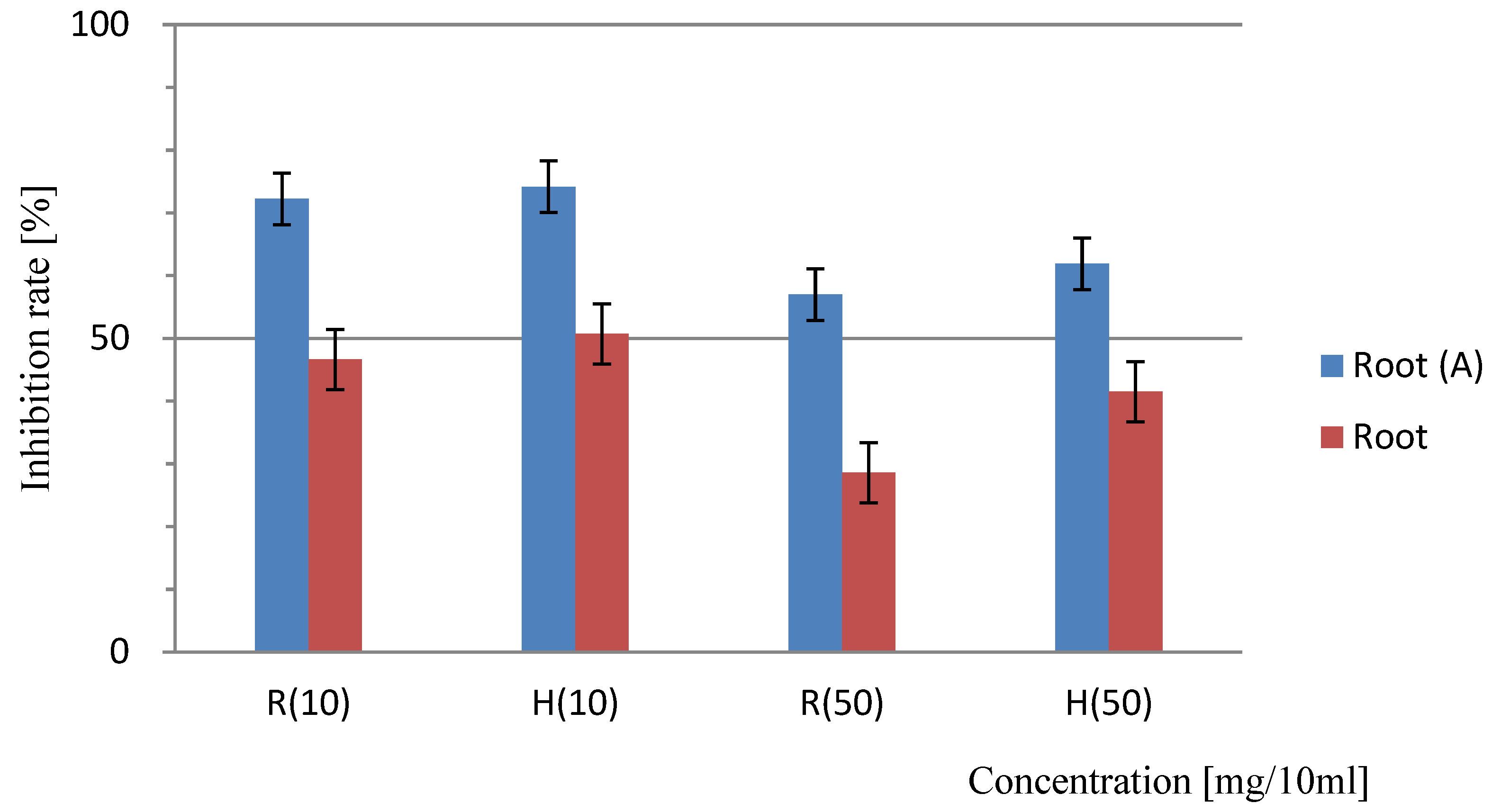

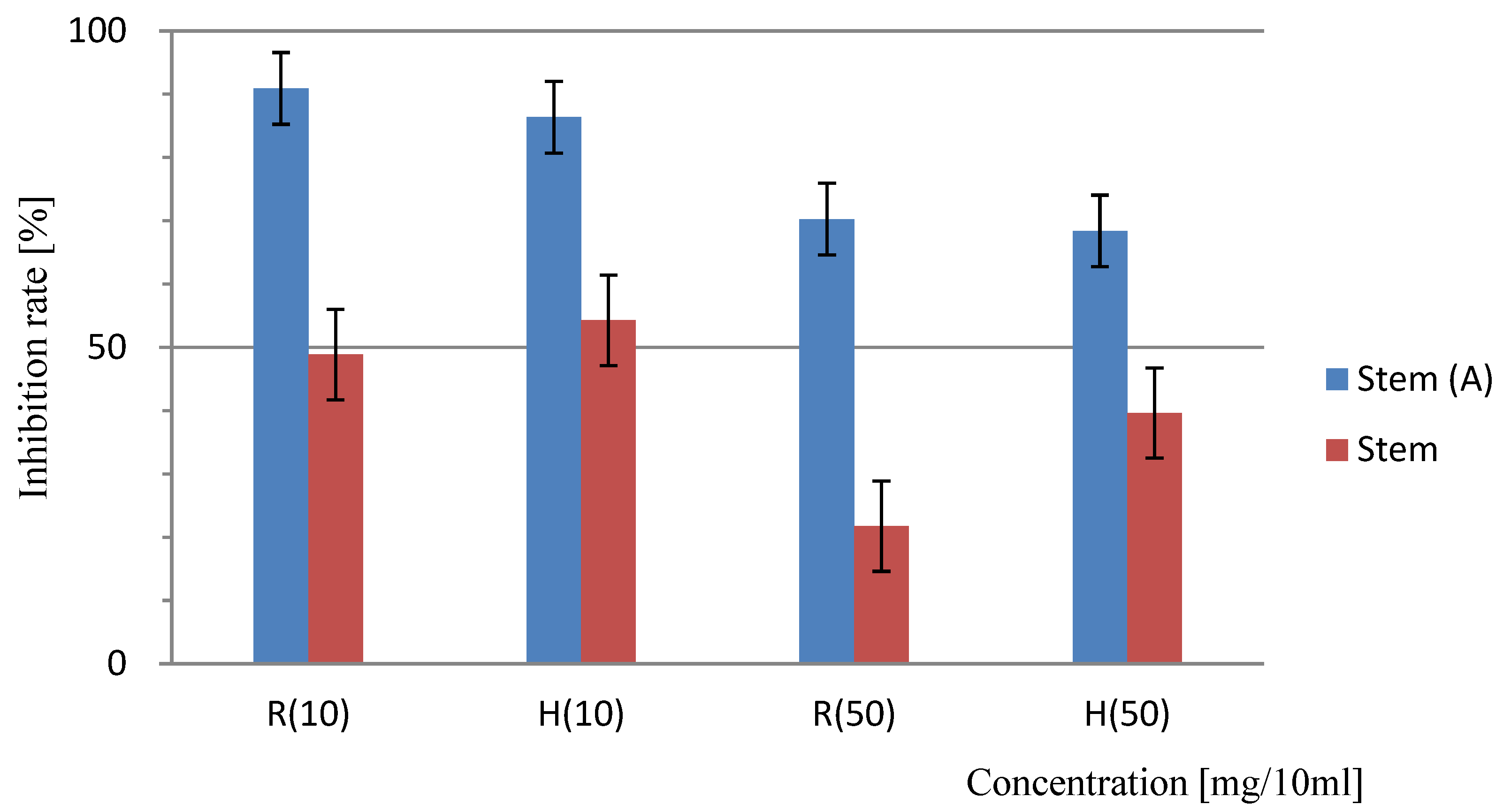

In this experiment, the activated carbon mixed with agar media at a ratio (1:25) was utilized as part of the Sandwich method to investigate its ability to reduce the negative effect of allelochemicals. The results of the first test (after 90 days) showed inhibitory effects on the growth of lettuce seedling roots and hypocotyls at a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL in the following order: roots (35.7%, 35.1%), leaves (9.7%, 19.1%), and stem (-18.9%, -6.2%). For the stem test, the growth rate of the test plants exceeded that of the control group; thus, it is represented with negative values for statistical purposes. At a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, inhibitory effects on the growth of lettuce seedlings roots and hypocotyls were observed in the following order: leaves (45.5%, 37.4%), stem (31.5%, 28.5%), and roots (24.5%, 27.2%), respectively.

In the second test (after 150 days), at a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the inhibitory effects on the growth of lettuce seedling roots and hypocotyls were observed in the following order: stem (37.1%, 33.5%), roots (19.9%, 16.6%), and leaves (16.8%, 32.3%). On the other hand, at a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, the inhibitory effects on growth were observed in the following order: roots (61.6%, 49.0%), leaves (56.4%, 54.2%), and stem (28.0%, 34.7%) for radicales and hypocotyls, respectively. The stem’s germination rate was 92.3% at a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, while that of all other tested areas was 100%.

The average results of the two tests showed that at a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the average inhibition rates were 13.3% for the leaves, 27.8% for the roots, and 9.1% for the stem. At a concentration of 50 mg/10 mL, the average inhibition rates were 50.9% for the leaves, 43.0% for the roots, and 29.7% for the stem. Overall, the addition of the activated carbon reagent reduced the allelopathic inhibition rates by various parts of Platycodon (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

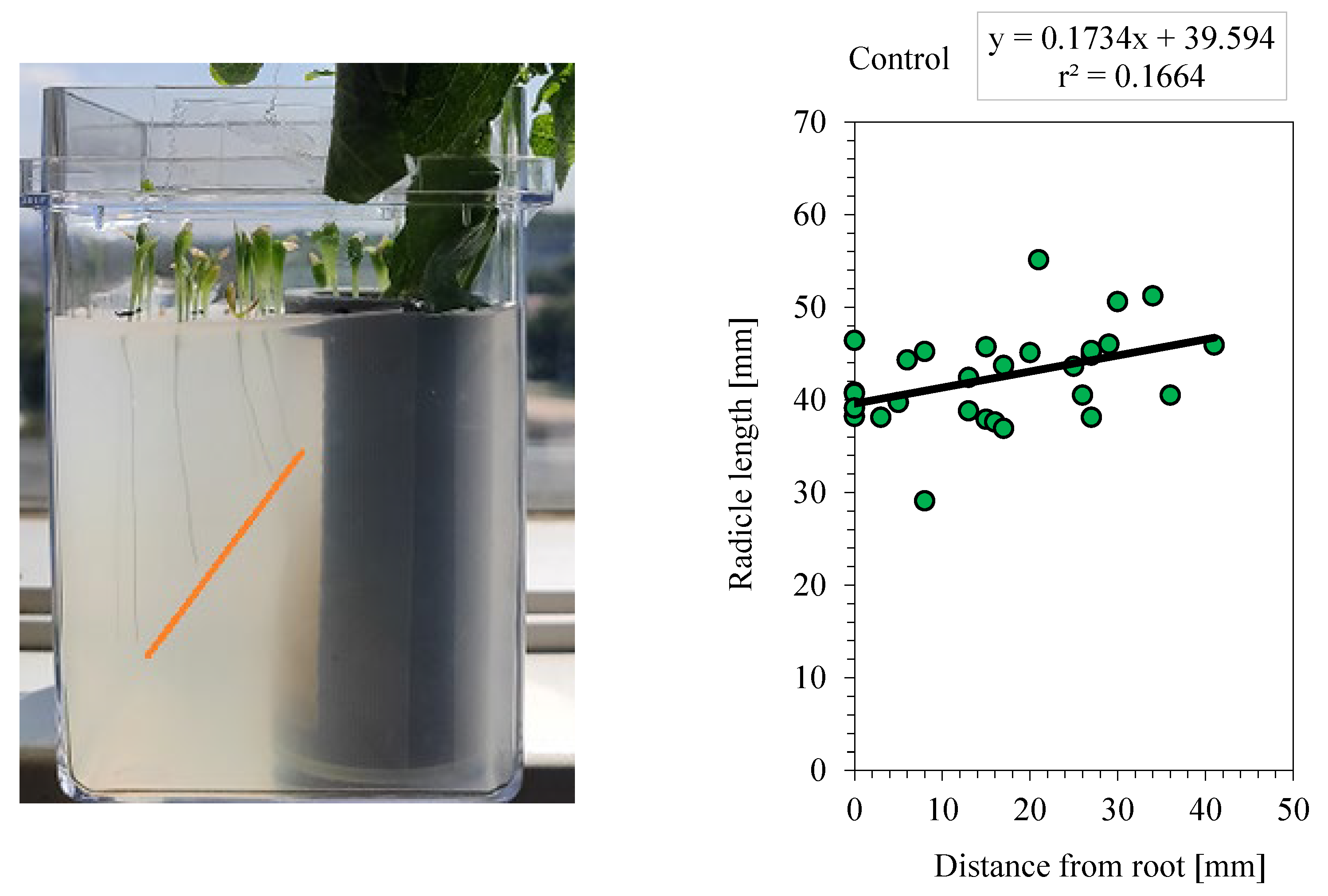

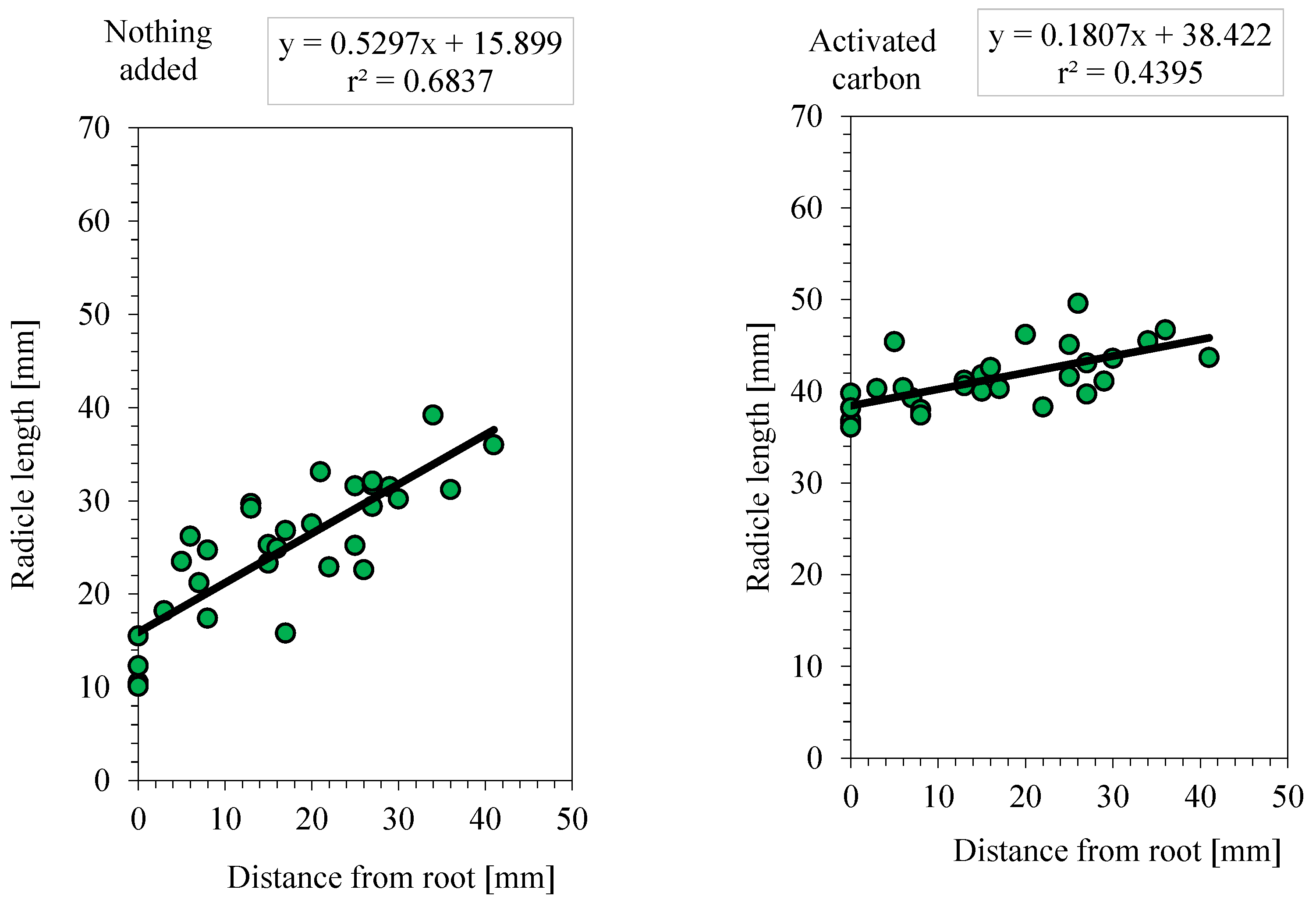

The results of the Plant Box method revealed a certain level of allelopathic inhibition in the roots of the test seedlings (

Figure 7).

In the first test (after 60 days), Zone 1 exhibited an average inhibition rate of 28.6% in the radicals and 23.9% in the hypocotyls of the tested lettuce seedling. The inhibition rate was higher for the roots closer to the test seedlings and decreased with a higher increase in distance. The germination rate was 90.9%. Zone 2 displayed average inhibition rates of 34.4% in the radicals and 10.4% in the hypocotyls; these also decreased with distance, and there was a germination rate of 100%. Zone 3 showed average inhibition rates of 33.5% in the radicals and 14.9% in the hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 93.9%. Overall, the results from the three test zones indicated that the root secretions of Platycodon had a certain allelopathic inhibitory effect against growth of the tested lettuce plant, with average inhibition rates of 33.1% in radicals and 16.4% in hypocotyls, and an average germination rate of 94.9%.

For the second test (after 90 days), Zone 1 exhibited average inhibition rates of 46.7% in radicals and 21.8% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 96.9%. Zone 2 displayed average inhibition rates of 48.3% in radicals and 9.80% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 100%. Zone 3 showed average inhibition rates of 41.7% in radicals and 12.4% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 100%. This indicated that the root secretions of Platycodon had average inhibitory effects of 45.6% on the radicals and 14.7% on the hypocotyls of lettuce, with an average germination rate of 98.9%.

3.3. Plant Box Method: Allelopathic Activity of Root Secretions from Platycodon

In the third test (after 150 days), Zone 1 exhibited average inhibition rates of 57.7% in radicals and 22.3% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 90.9%. Zone 2 displayed average inhibition rates of 55.9% in radicals and 28.6% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 87.9%. Zone 3 showed average inhibition rates of 59.6% in radicals and 31.9% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 96.9%. Zone 4 exhibited average inhibition rates of 57.7% in radicals and 20.4% in hypocotyls, with a germination rate of 93.9%. The results from these four test zones indicated that the roots of Platycodon had an average inhibitory effect of 57.7% on the roots and 25.8% on the seedlings, with an average germination rate of 92.4% (

Table 2).

3.4. Effect of Activated Carbon on the Adsorption of Allelopathic Substances from Platycodon Roots

The results of using the Plant Box method to assess the absorption effect of activated carbon revealed that following the first test (after 90 days), Zone 1 exhibited an average inhibition rate of -34.2% in the radicals and -18.5% in the hypocotyls of the tested lettuce plant. This suggests that the addition of activated carbon significantly eliminated the inhibitory effect of root secretions from Platycodon. This effect promotes the growth of lettuce seedlings, with an average germination rate of 97.9%.

For the second test (after 150 days), Zone 1 displayed average inhibition rates of -10.4% in radicals and 5.13% in hypocotyls, while Zone 2 showed inhibition rates of 23.3% in radicals 8.8% in hypocotyls. Zone 3 exhibited inhibition rates of 3.0% in radicals and 2.0% in hypocotyls, and Zone 4 had inhibition rates of -13.7% in radicals and 3.8% in hypocotyls. The average inhibition rates for radical and hypocotyl growth throughout the four test zones were 0.8% and 9.1%, respectively, with a germination rate of 92.8% (

Figure 8).

Author Contributions

Author contributions: Conceptualization, L.B., Y.F., S.M.; Methodology, Y.F., S.M.; Software, X.Z., G.K.; Validation, L.B., Y.F., K.S.; Formal analysis, L.B., X.Z., G.K.; Investigation, S.M., Y.F.; Data management, L.B., S.M., Y.F.; Preparation of draft, L.B., T.I.; Writing—review and editing, L.B., S.M., Y.F., K.S.; Visualization, T.I., X.Z.; Supervision, Y.F., S.M.; Funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

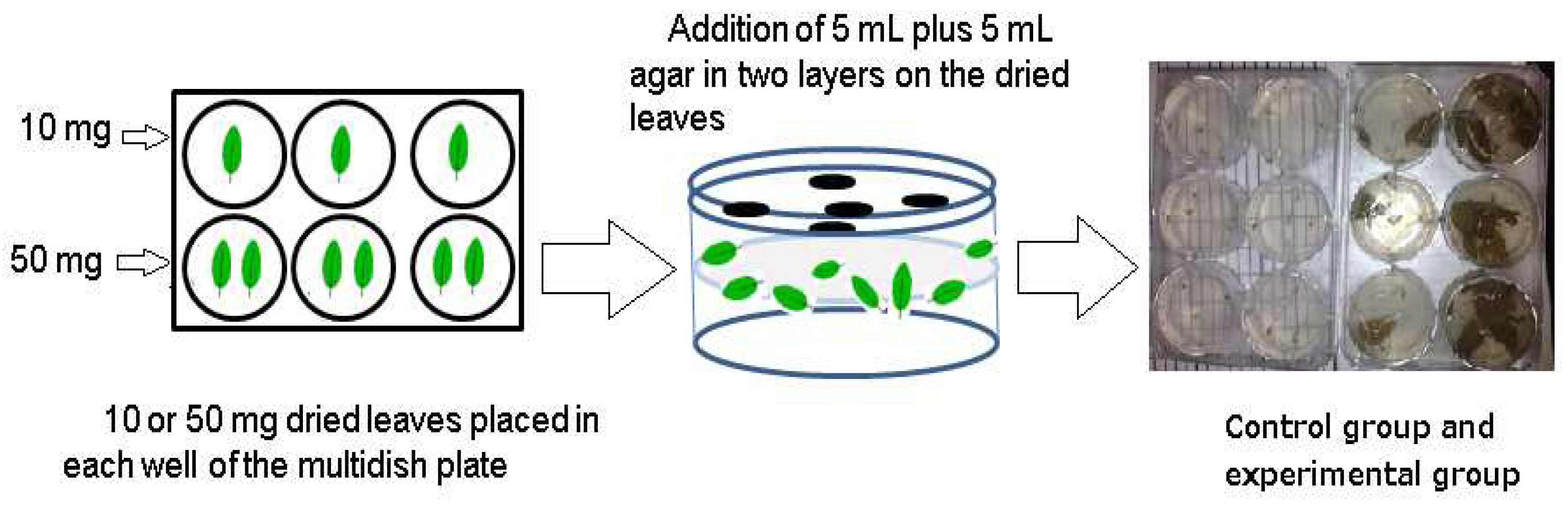

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Sandwich Method.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of Sandwich Method.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the Plant Box method.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the Plant Box method.

Figure 3.

Model of Activated carbon adsorbing substances.

Figure 3.

Model of Activated carbon adsorbing substances.

Figure 4.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon leaves. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 2.1%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0%). Bars indicate SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference, R (50) =P<0.005 differences.

Figure 4.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon leaves. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 2.1%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0%). Bars indicate SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference, R (50) =P<0.005 differences.

Figure 5.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon roots. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 0.4%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0% ). Bars indicate SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, R (50) =P<0.001 H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Figure 5.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon roots. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 0.4%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0% ). Bars indicate SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, R (50) =P<0.001 H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Figure 6.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon stems. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 0.5%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0%). Bars indicate the SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, R (50) =P<0.001 H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Figure 6.

Sandwich method for the determination of the allelopathic effects of Platycodon stems. “A” indicates the results of the trial with activated charcoal; results lacking identification represent the trial without the addition of activated charcoal. At a concentration of 10 mg/10 mL, the difference between the results of the non-added and added activated carbon test areas was 0.5%, and this was a significant difference (<5.0%). Bars indicate the SD, T-test: R (10) =P<0.001, H (10) =P<0.001, R (50) =P<0.001 H (50) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Figure 7.

Results of the allelopathic effects of the root secretions of Platycodon. Control: [r = 0.40; y = 0.17 x + 39.6; n = 29]; root elongation = 100%, Nothing added: [r = 0.82; y = 0.53x + 15.9; n =32]; root elongation = 40.4%, Activated carbon: [r =0.66; y = 0.18x +38.4; n =30]; root elongation =97.0%.

Figure 7.

Results of the allelopathic effects of the root secretions of Platycodon. Control: [r = 0.40; y = 0.17 x + 39.6; n = 29]; root elongation = 100%, Nothing added: [r = 0.82; y = 0.53x + 15.9; n =32]; root elongation = 40.4%, Activated carbon: [r =0.66; y = 0.18x +38.4; n =30]; root elongation =97.0%.

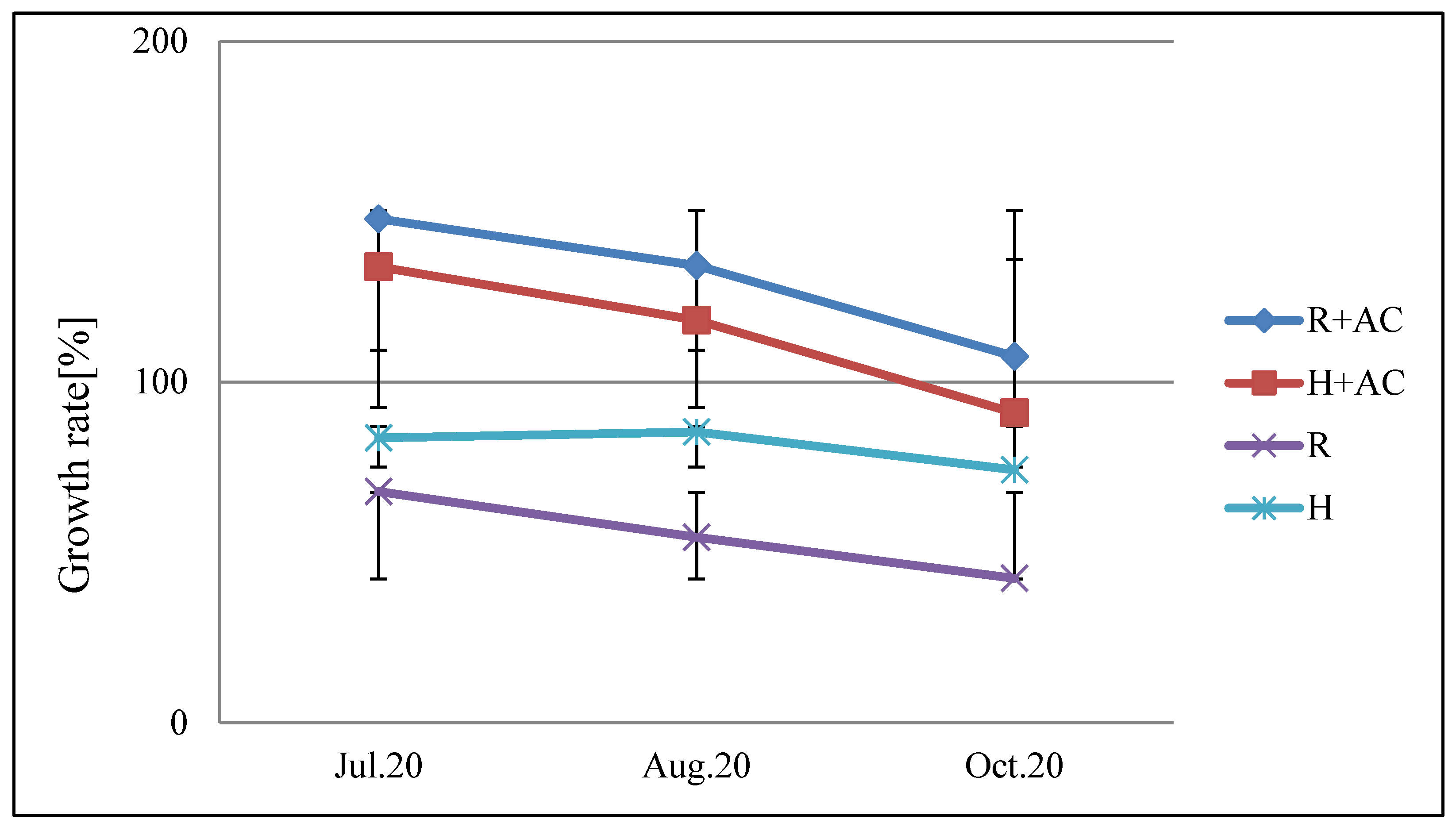

Figure 8.

Effect of activated carbon on the allelopathic activity of root secretions from Platycodon. R: growth rate of young roots of test plants; H: growth rate of test plant seedlings; R+AC: growth rate of radicals of lettuce after adding activated carbon; R+AC: growth rate of hypocotyls after adding activated carbon. When the germination rate of the test plants was not added with activated carbon (95.5%), the test area with activated carbon was added (94.8%). Bars indicate the SD. The significant difference in the root growth rate between adding and not adding activated carbon was 0.3%, and the intentional difference in the seedling growth rate was 3.1%, which was less than 5.0%. T-test: R, H (Jul.20) =P<0.001, R, H (Aug.20) =P<0.001, R, H (Oct.20) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Figure 8.

Effect of activated carbon on the allelopathic activity of root secretions from Platycodon. R: growth rate of young roots of test plants; H: growth rate of test plant seedlings; R+AC: growth rate of radicals of lettuce after adding activated carbon; R+AC: growth rate of hypocotyls after adding activated carbon. When the germination rate of the test plants was not added with activated carbon (95.5%), the test area with activated carbon was added (94.8%). Bars indicate the SD. The significant difference in the root growth rate between adding and not adding activated carbon was 0.3%, and the intentional difference in the seedling growth rate was 3.1%, which was less than 5.0%. T-test: R, H (Jul.20) =P<0.001, R, H (Aug.20) =P<0.001, R, H (Oct.20) =P<0.001 significant difference.

Table 1.

Allelopathic activity of different Platycodon components according to the Sandwich method.

Table 1.

Allelopathic activity of different Platycodon components according to the Sandwich method.

| 10 mg |

50 mg |

| Date Part R |

H |

G |

R |

H |

G |

| Jul. 20 |

Leaf |

26.1±1.3 |

43.8±1.4 |

100±0.0 |

11.9±1.0 |

38.9±1.7 |

86.7±11.5 |

| Root |

58.8±0.7 |

56.9±0.3 |

100±0.0 |

29.1±0.5 |

47.4±0.3 |

100±0.0 |

| Stem |

77.3±2.2 |

94.6±2.5 |

100±0.0 |

22.8±1.3 |

45.8±1.4 |

93.3±8.9 |

| Aug. 20 |

Leaf |

20.2±1.3 |

34.9±1.6 |

93.3±8.9 |

7.6±1.4 |

31.4±2.3 |

86.7±10.9 |

| Root |

57.4±1.4 |

64.1±1.1 |

100±0.0 |

48.9±0.7 |

60.0±0.6 |

100±0.0 |

| Stem |

53.1±1.7 |

67.6±1.9 |

100±0.0 |

22.5±1.5 |

40.0±2.0 |

100±0.0 |

| Oct.20 |

Leaf |

15.6±1.6 |

35.8±2.1 |

100±0.0 |

4.6±0.5 |

13.1±0.7 |

93.3±8.9 |

| Root |

23.6±3.5 |

31.0±2.6 |

93.3±8.9 |

7.7±0.7 |

17.0±0.9 |

100±0.0 |

| Stem |

30.5±3.4 |

45.2±3.1 |

100±0.0 |

19.9±2.5 |

33.1±2.5 |

100±0.0 |

| AIR |

Leaf |

79.4 |

61.8 |

0 |

91.9 |

72.2 |

6.7 |

| Root |

53.4 |

49.3 |

2.2 |

71.4 |

58.5 |

4.4 |

| Stem |

46.3 |

30.8 |

2.2 |

78.3 |

60.4 |

2.2 |

Table 2.

The absorption effect of activated carbon on allelopathic substances from various Platycodon components.

Table 2.

The absorption effect of activated carbon on allelopathic substances from various Platycodon components.

| 10 mg |

50 mg |

| Date Part R |

H |

G |

R |

H |

G |

| Aug. 20 |

Leaf |

90.2±2.7 |

80.9±1.8 |

100±0.0 |

54.5±3.1 |

62.6±3.2 |

100±0.0 |

| Root |

64.3±2.8 |

67.9±1.8 |

100±0.0 |

75.6±2.5 |

72.8±1.4 |

100±0.0 |

| Stem |

118.9±3.6 |

106.2±2.4 |

100±0.0 |

68.5±2.1 |

71.5±1.6 |

93.3±8.9 |

| Oct.10 |

Leaf |

83.2±1.3 |

67.7±0.9 |

100±0.0 |

43.6±1.6 |

45.9±2.2 |

100±0.0 |

| Root |

80.1±4.2 |

83.4±3.4 |

100±0.0 |

38.4±1.7 |

50.9±0.9 |

100±0.0 |

| Stem |

62.9±1.8 |

66.6±1.5 |

100±0.0 |

71.9±2.0 |

65.3±1.8 |

100±0.0 |

| AIR |

Leaf |

13.3 |

25.7 |

0 |

50.9 |

45.8 |

0 |

| Root |

27.8 |

24.3 |

0 |

43.0 |

38.1 |

0 |

| Stem |

9.1 |

13.6 |

0 |

29.7 |

31.6 |

2.2 |