Submitted:

02 February 2024

Posted:

02 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vineyards

2.4. Treatment Plots, Cultural Practices, and Weather Data Survey

2.5. Disease Assessment

2.6. Yield Quantity and Qualitative Parameters of the Berries

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

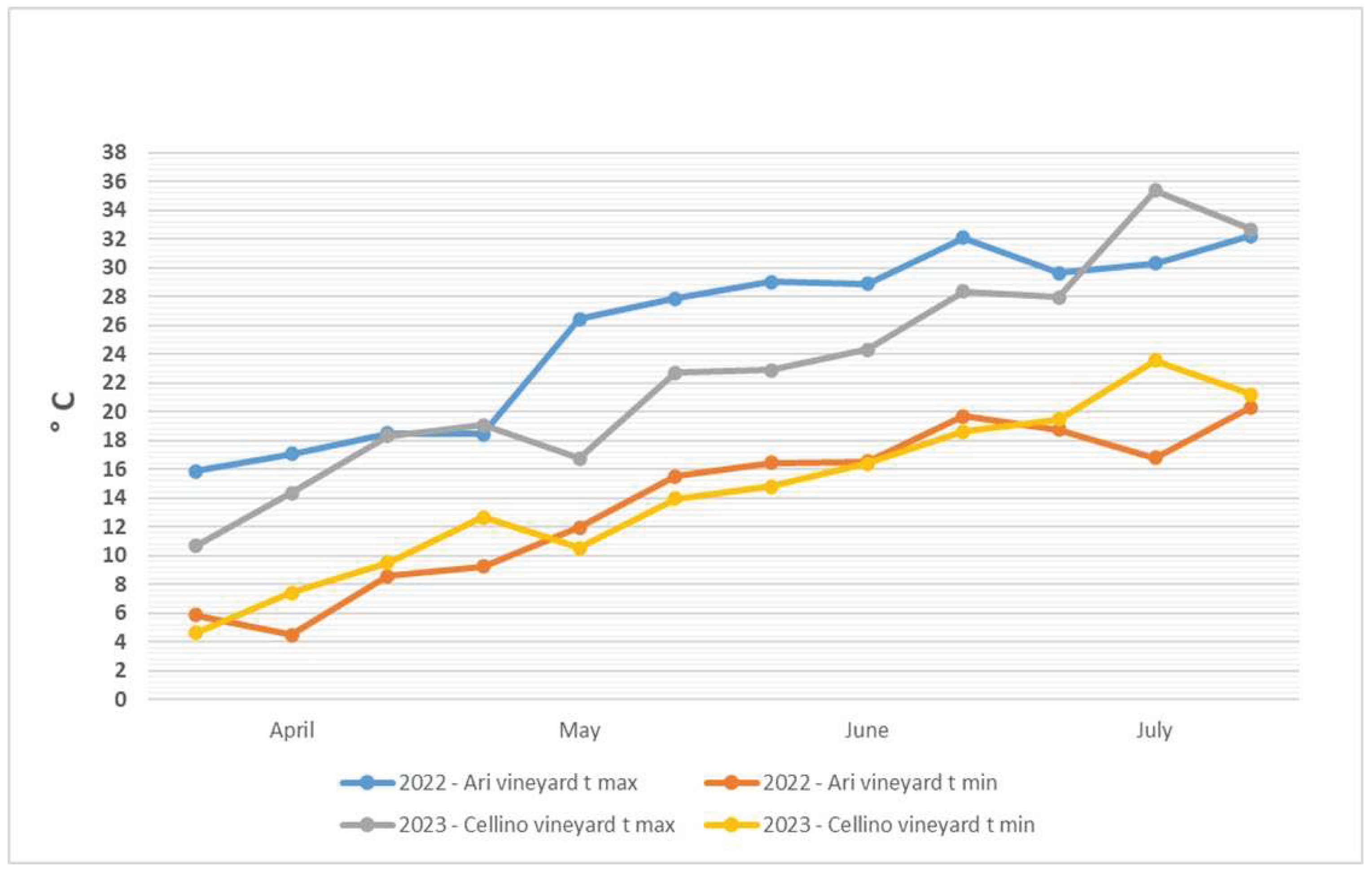

3.1. Rainfall and Temperatures Recorded at Ari Vineyard in 2022

3.2. Rainfall and Temperatures Recorded at Cellino Vineyard in 2023

3.3. Incidence and Severity of the Disease at Ari Vineyard in 2022

3.3.1. Progression of the Disease in the Untreated Control Plants

3.3.2. Incidence and Severity of the Disease on the Leaves of the Treatments

3.3.3. Incidence and Severity of the Disease on the Bunches of the Treatments

3.4. Incidence and Severity of the Disease at Cellino Vineyard in 2023

3.4.1. Progression of the Disease in the Untreated Control Plants

3.4.2. Incidence and Severity on the Leaves and Bunches of the Treatments

3.5. Effect of the Leaf Applications on Yield Quantity and Qualitative Parameters of the Berries

3.5.1. Ari Vineyard

3.5.2. Cellino Vineyard

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Wilcox, W.F.; Dry, I.B.; Seem, R.C.; Milgroom, M.G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): A fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology, and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.C.; Gadoury, D.M. Powdery mildew of grape. In: Kumar, J.; Chaube, H.S.; Singh, U.S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.N. (Eds.), Plant diseases of international importance. Volume III. Diseases of fruit crops. 1992, pp.129-146.

- Gadoury, D.M.; Pearson, R.C. Ascocarp dehiscence and ascospore discharge. Phytopathology 1990a, 80, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Pearson, R.C. Germination of ascospores and infection of Vitis by Uncinula necator. Phytopathology 1990b, 80, 1198–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essling, M.; McKay, S.; Petrie, P.R. Fungicide programs used to manage powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) in Australian vineyards. Crop Prot. 2021, 139, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, B.; Zito, S.; Calonnec, A. Climate vs. grapevine pests and diseases worldwide: The first results of a global survey. OENO One 2017, 51, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Wilcox, W.F.; Rumbolz, J.; Gubler, W.D. Powdery mildew. In: Compendium of Grapevine Diseases (2nd edn.) (Wilcox, W.F., Gubler, W.D. and Uyemoto, J., eds). 2011, APS Press.

- Sall, M.A.; Wyrsinski, J. Perennation of powdery mildew in buds of grapevines. Plant Dis. 1982, 66, 678–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.C.; Gärtel, W. Occurrence of hyphae of Uncinula necator in buds of grapevine. Plant Dis. 1985, 69, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.K. The influence of annual weather patterns on epidemics of Uncinula necator in Rheinhessen. Vitic. Enol. Sci. 1990, 45, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Pearson, R.C. Heterothallism and pathogenic specialization in Uncinula necator. Phytopathology 1991, 81, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, I.S.; Ghule, S.B.; Sawant, S.D. Molecular analysis reveals that lack of chasmothecia formation in Erysiphe necator in Maharashtra, India is due to presence of only MAT1-2 mating type idiomorph. VITIS-J. Grapevine Res. 2015, 54, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi, P.; Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Pearson, R.C. Distribution and retention of chasmothecia of Uncinula necator on the bark of grapevines. Plant Dis. 1995, 79, 15–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffi, T.; Rossi, V.; Legler, S.E.; Bugiani, R. A mechanistic model simulating ascosporic infections by Erysiphe necator, the powdery mildew fungus of grapevine. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.N.; Wilcox, W.F. Effects of fruit zone leaf removal, training system, and variable irrigation on powdery mildew development on Vitis vinifera L. Chardonnay. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011a, 62, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.N.; Meyers, J.; Grove, G.G.; Wilcox, W.F. Quantification of powdery mildew severity as a function of canopy variability and associated impacts on sunlight penetration and spray coverage within the fruit zone. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011b, 62, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, G.D.; Thind, T.S.; Tajinder, S. Occurrence of cleistothecia of Uncinula necator on grapes. Plant Dis. Res. 1996, 11, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, V.; Caffi, T.; Legler, S.E. Dynamics of ascospore maturation and discharge in Erysiphe necator, the causal agent of grape powdery mildew. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, D.; Pellegrini, E.; Pertot, I. Occurrence of Erysiphe necator chasmothecia and their natural parasitism by Ampelomyces quisqualis. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Magarey, P.A.; Emmett, R.; Magarey, R. Effects of environment and fungicides on epidemics of grape powdery mildew: Considerations for practical model development and disease management. Vitic. Enol. Sci. 1997, 52, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Ficke, A.; Wilcox, W.F. Ontogenic resistance to powdery mildew in grape berries. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficke, A.; Gadoury, D.M.; Seem, R.C.; Dry, I.B. Effects of ontogenic resistance upon establishment and growth of Uncinula necator on grape berries. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Délye, C.; Laigret, F.; Corio-Costet, M.F. A mutation in the 14-alpha demethylase gene of Uncinula necator that correlates with resistance to a sterol biosynthesis inhibitor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2966–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunova, A.; Pizzatti, C.; Saracchi, M.; Pasquali, M.; Cortesi, P. Grapevine Powdery Mildew: Fungicides for Its Management and Advances in Molecular Detection of Markers Associated with Resistance. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission – Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of The Council on the sustainable use of plant protection products. 2021/2115. Brussels, 22.06.2022, COM (2022) 305 final.

- Hinckley, EL.S.; Crawford, J.T.; Fakhraei, H. A shift in sulfur-cycle manipulation from atmospheric emissions to agricultural additions. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, D.J.; Huffaker, C.B. Predator (Metaseiulus occidentalis) – prey (Pronematus spp.) interactions under sulfur and cattail pollen applications in a non-commercial vineyard. Entomophaga 1974, 19, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarey, P.A.; Magarey, R.D.; Emmett, R.W. Principles for managing the foliage diseases of grapevines with low input of pesticides. 6th International Congress on Organic Viticulture, Basel, Switzerland, 2000, Vol. 200, pp. 140-148.

- Robinson, J.C.; Pease, W.S. Preventing pesticide-related illness in California agriculture. California Policy Seminar, 1993, Berkeley, University of California.

- Mehler, L.N.; Schenker, M.B.; Romano, P.S.; Samuels, S.J. California surveillance for pesticide-related illness and injury: Coverage, bias, and limitations. J. Agromedicine 2006, 11, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.; Salmon, E.S. The fungicidal properties of certain spray-fluids VIII. The fungicidal properties on mineral, tar and vegetable oils. J. Agric. Sci. 1931, 21, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, W.D.; Ypema, H.L.; Ouimette, D.G.; L.J. Occurrence of resistance in Uncinula necator to triadimefon, myclobutanil and fenarimol in California grapevine. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 902–909. [CrossRef]

- Pertot, I.; Caffi, T.; Rossi, V.; Mugnai, L.; Hoffmann, C.; Grando, M.S.; Gary, C.; Lafond, D.; Duso, C.; Thiery, D.; Mazzoni, V.; Anfora, G. A critical review of plant protection tools for reducing pesticide use on grapevines and new perspectives for the implementation of IPM in viticulture. Crop Prot. 2017, 97, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legler, S.E.; Caffi, T.; Rossi, V. Activity of different plant protection products against chasmothecia of grapevine powdery mildew. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, (4 suppl), 417-417.

- Rossi, V.; Caffi, T.; Legler, S.E.; Bugiani, R.; Frisullo, P. Dispersal of the sexual stage of Erysiphe necator in northern Italy. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin 2011, 66, 115–121.

- Caffi, T.; Legler, S.E.; Bugiani, R.; Rossi, V. Combining sanitation and disease modelling for control of grapevine powdery mildew. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 135, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legler, S.E.; Caffi, T.; Rossi, V. A model for the development of Erysiphe necator chasmothecia in vineyards. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legler, S.E.; Caffi, T.; Rossi, V. A nonlinear model for temperature-dependent development of Erysiphe necator chasmothecia on grapevine leaves. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Salinari, F.; Poni, S.; Caffi, T.; Bettati, T. Addressing the implementation problem in agricultural decision support systems: The example of vite.net®. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 100, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, O.; Fedele, G.; Salotti, I.; Rossi, V. Infection risk-based application of plant resistance inducers for the control of downy and powdery mildews in vineyards. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, E.; Dolzani, C.; Stefanini, M.; Gratl, V.; Bettinelli, P.; Nicolini, D.; Betta, G.; Dorigatti, C.; Velasco, R.; Letschka, T.; et al. R-Loci Arrangement Versus Downy and Powdery Mildew Resistance Level: A Vitis Hybrid Survey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisp, P.; Wicks, T.J.; Lorimer, M.; Scott, E.S. An evaluation of biological and abiotic controls for grapevine powdery mildew. 1. Greenhouse studies. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbore, J.; Bruez, E.; Vallance, J.; Grizard, D.; Regnault-Roger, C.; Rey, P. Protection of grapevines by Pythium oligandrum strains isolated from Bordeaux vineyards against powdery mildew, Biocontrol of major grapevine diseases: Leading research; CABI: Wallingford UK, 2016; pp. 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Caffi, T.; Legler, S.E.; Furiosi, M.; Salotti, I.; Rossi, V. 4 Application of Ampelomyces quisqualis in the Integrated Management of grapevine powdery mildew. Microbial Biocontrol Agents: Developing Effective Biopesticides. 2022, 69–89.

- Pugliese, M.; Monchiero, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Garibaldi, A. Application of laminarin and calcium oxide for the control of grape powdery mildew on Vitis vinifera cv. Moscato. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2018, 125, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Rotolo, C.; Gerin, D.; Abate, D.; Pollastro, S.; Faretra, F. Global transcriptome analysis and differentially expressed genes in grapevine after application of the yeast-derived defense inducer cerevisane. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2020–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, F.; Vitale, A.; Panebianco, S.; Lombardo, M.F.; Cirvilleri, G. COS-OGA applications in organic vineyards manage major airborne diseases and maintain the postharvest quality of wine grapes. Plants 2022, 11, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furiosi, M.; Rossi, V.; Legler, S.; Caffi, T. Study on fungicides’ use in viticulture: Present and future scenarios to control powdery and downy mildew. In BIO Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: 2022, Vol. 50, p. 03006.

- Epstein, E. The anomaly of silicon in plant biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994, 91, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datnoff, L.E.; Deren, C.W.; Snyder, G.H. Silicon fertilization for disease management of rice in Florida. Crop Prot. 1997, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savant, N.K.; Snyder, G.H.; Datnoff, L.E. Silicon management and sustainable rice production. Adv. Agron. 1997, 58, 151–199. [Google Scholar]

- Tubaña, B.S.; Heckman, J.R. Silicon in Soils and Plants. In Silicon and Plant Diseases; Springer Int. Publ.: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 7–51. [Google Scholar]

- Laane, H.M. The Effects of the application of foliar sprays with stabilized silicic acid: An overview of the results from 2003–2014. Silicon 2017, 9, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laane, H.M. The Effects of Foliar Sprays with Different Silicon Compounds. Plants 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, J.G.; Bowen, P.A.; Ehret, D.L.; Glass, A.D.M. Foliar applications of potassium silicate reduce severity of powdery mildew of cucumber, muskmelon, and zucchini squash. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.A.; Karoliussen, I.; Rohloff, J.; Strimbeck, R. Foliar application of silicon fertilizers inhibit powdery mildew in greenhouse cucumber. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, P.A.; Menzies, J.G.; Ehret, D.L.; Samuels, L.; Glass, A.D.M. Soluble silicon sprays inhibit powdery mildew development on grape leaves. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guével, M.H.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, E.E. Effect of root and foliar applications of soluble silicon on powdery mildew control and growth of wheat plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 119, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Veto, L.J.; Sholberg, P.L.; Wardle, D.A.; Haag, P. Use of potassium silicate for the control of powdery mildew [Uncinula necator (Schwein) Burrill] in Vitis vinifera L. cultivar Bacchus. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1996, 47, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soratto, R.P.; Fernandes, A.N.; Crusciol, C.A.C.; de Souza-Schlick, G.D. Yield, tuber quality, and disease incidence on potato crop as affected by silicon leaf application. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2012, 47, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olle, M.; Schnug, E. The effect of foliar applied silicic acid on growth and chemical composition of tomato transplants. J. Kulturpflanzen 2016, 68, 241–243. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, N.B.; Chandrashekhar, N.; Mahendra, A.C.; Patil, S.U.; Thippeshappa, G.N.; Laane, H.M. Effect of foliar spray of soluble silicic acid on growth and yield parameters of wetland rice in hilly and coastal zone soils of Karnataka, South India. J. Plant. Nutr. 2011, 34, 883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedarnath, R.K.T.; Prakash, N.B.; Achari, R. Efficacy of foliar sprays of silicon (OSAB) on powdery mildew (Oidium neolycopersici) disease reduction in tomato. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Silicon in Agriculture, Bengaluru, India, 24–28 October 2017; p. 92. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Realpe, O.H.R.; Laane, H.M. Effect of the foliar application of soluble silicic acid and low dose boric acid on papaya trees. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Silicon in Argriculture, Natal, South Africa, 26–31 October 2008; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, N.B.; Chandrashekhar, N.; Mahendra, A.C.; Thippeshappa, G.N.; Patil, S.U.; Laane, H.M. Effect of oligomeric silicon and low dose boron as foliar application on wetland rice. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Silicon in Agriculture, Natal, South Africa, 26–31 October 2008; p. 86. 59.

- Epstein, E. Silicon. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, E. Silicon in Plants: Facts vs. Concepts. In Studies in plant science. Elsevier, 2001. Vol. 8, p. 1-15.

- Datnoff, L.E.; Elmer, W.H.; Huber, D.M. Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease. St. Paul, MN: The American Phytopathological Society, 2007.

- Van, B.J.; De Vleesschauwer, D.; and Hofte, M. Towards establishing broadspectrum disease resistance in plants: Silicon leads the way. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Kim, K.W.; Park, E.W.; Choi, D. Silicon-induced cell wall fortification of rice leaves: A possible cellular mechanism of enhanced host resistance to blast. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domiciano, G.P.; Rodrigues, F.A.; Guerra, A.M.N.; Vale, F.X.R. Infection process of Bipolaris sorokiniana on wheat leaves is affected by silicon. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2013, 38, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.S.; Rodrigues, F.A.; Schurt, D.A.; Souza, N.F.A.; Cruz, M.F.A. Cytological aspects of the infection process of Pyricularia oryzae on leaves of wheat plants supplied with silicon. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2013, 38, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshi, H. Studies on the nature of rice blast resistance. Kyusu. Imp. Univ. Sci. Fakultato Terkultura Bull. 1941, 9, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, A. and Takahashi, E. The role of silicon in the mineral nutrition of the rice plant, In Proceedings of a Symposium of the International Rice Research Institute, John Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1965, pp. 123–146.

- Blaich, R.; Grundhὅfer, H. Silicate incrusts induced by powdery mildew in cell walls of different plant species. J. Plant Dis. Protect. 1998, 105, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chérif, M.; Benhamou, N.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon induced resistance in cucumber plants against Pythium ultimum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1992a, 41, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chérif, M.; Menzies, J.G.; Benhamou, N.; Bélanger, R.R. Studies of silicon distribution in wounded and Pythium ultimum infected cucumber plants. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1992b, 41, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chérif, M.; Asselin, A.; Bélanger, R.R. Defense responses induced by soluble silicon in cucumber roots infected by Pythium spp. Phytopathology 1994, 84, 236–242. [CrossRef]

- Fawe, A.; Abou-Zaid, M.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon-mediated accumulation of flavonoid phytoalexins in cucumber. Phytopathology 1998, 88, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawe, A.; Menzies, J.G.; Chérif, M.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon and disease resistance in dicotyledons. In Silicon in Agriculture (Datnoff, L.E., Snyder, G.H. and Korndo¨fer, G.H., Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2001, pp. 159–170.

- Bélanger, R.R.; Benhamou, N.; Menzies, J.G. Cytological evidence of an active role of silicon in wheat resistance to powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici). Phytopathology 2003, 93, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.A.; Benhamou, N.; Datnoff, L.E.; Jones, J.B.; Bélanger, R.R. Ultrastructural and cytochemical aspects of silicon-mediated rice blast resistance. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.A.; McNally, D.J.; Datnoff, L.E.; Jones, J.B.; Labbe’, C.; Benhamou, N.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon enhances the accumulation of diterpenoid phytoalexins in rice: A potential mechanism for blast resistance. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Oliveira, R.; Nascimento, K.; Rodrigues, F. Biochemical responses of coffee resistance against Meloidogyne exigua mediated by silicon. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, A.A.; Rodrigues, F.; Do Nascimento, K.J. Physiological and biochemical aspects of the resistance of banana plants to Fusarium wilt potentiated by silicon. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauteux, F.; Chain, F.; Belzile, F.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. The protective role of silicon in the Arabidopsis-powdery mildew pathosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 17554–17559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vleesschauwer, D.; Djavaheri, M.; Bakker, P.; Hofte, M. Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374r-induced systemic resistance in rice against Magnaporthe oryzae is based on pseudobactin-mediated priming for a salicylic acid-repressible multifaceted defense response. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1996–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.M.; Chao, T.C.; Wang, J.F.; Liu, A.C.; Ho, F.I.; Cheng, C.P. Virus-induced gene silencing reveals the involvement of ethylene-, salicylic acid- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-related defense pathways in the resistance of tomato to bacterial wilt. Physiol. Plant. 2009, 136, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareeb, H.; Bozsó, Z.; Ott, P.G.; Repenning, C.; Stahl, F.; Wydra, K. Transcriptome of silicon-induced resistance against Ralstonia solanacearum in the silicon non-accumulator tomato implicates priming effect. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 75, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauteux, F.; Remus-Borel, W.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon and plant disease resistance against pathogenic fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 249, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivancos, J.; Labbe, C.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon-mediated resistance of Arabidopsis against powdery mildew involves mechanisms other than the salicylic acid (SA)-dependent defence pathway. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollomon, D.W. Fungicide resistance: Facing the challenge. Plant Prot. Sci. 2015, 51, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, C.T.; Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Ontogenic resistance to Uncinula necator varies by genotype and tissue type in a diverse collection of Vitis spp. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wasfy, M.M.M. The synergistic effects of using silicon with some vitamins on growth and fruiting of flame seedless grapevines. Stem Cell 2014, 5, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bhavya, H.K.; Nache Gowda, V.V.; Jaganath, S.; Sreenivas, K.N.; Prakash, N.B. Effect of foliar silicic acid and boron acid in Bangalore blue grapes. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Silicon in Argriculture, Beijing, China, 11–19 September 2011; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramteke, S.D.; Kor, R.J.; Bhanga, M.A.; Khot, A.P.; Zende, N.A.; Datir, S.S.; Ahire, K.D. Physiological studies on effects of Silixol on quality and yield in Thompson seedless grapes. Ann. Plant Physiol. 2012, 26, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, E. Silicon Solutions—Helping Plants to Help Themselves; Sestante: Bergamo, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-6642-151-1. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Afonso, J.; Nogueira, M.; Oliveira, A.A.; Cosme, F.; Falco, V. Silicates of potassium and aluminium (Kaolin); comparative foliar mitigation treatments and biochemical insight on grape berry quality in Vitis vinifera L. (cv. Touriga National and Touriga Franca). Biology 2020, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sut, S.; Malagoli, M.; Dall’Acqua, S. Foliar application of silicon in Vitis vinifera: Targeted metabolomics analysis as a tool to investigate the chemical variations in berries of four grapevine cultivars. Plants 2022, 11, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Active Ingredients |

Trade Name | Company | Formulation | Active Ingredient Concentration (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulphur | Tiovit Jet | Syngenta Group, Basel, Switzerland | water dispersible microgranules |

80 |

| Sulphur | ZolfoLiquido 40 | SAIM srl, Napoli, Italy | liquid suspension | 40 |

| Calcium Silicate | Barrier SiCa | Cosmocel, San Nicolas de los Garza, N.L., Mexico | liquid suspension | 21 CaO + 24 SiO2 |

| Silicon oxide + Iron | Optisyl | Manica S.p.A., Rovereto (TN), Italy |

liquid suspension | 16.5 SiO2 + 2 Fe |

|

Equisetum arvense L. |

Equisetum arvense | Agrisystem, Lamezia Terme (CZ), Italy |

liquid suspension | 0,2 |

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | ||

| Ari vineyard | Dose (Kg/L ha−1) | Cellino vineyard | Dose (Kg/L ha−1) |

| Sulphur 80% | 5* − 8 ** | Sulphur 40% | 5 |

| Calcium Silicate + Sulphur 80% | 1.5 + 3* − 4.8** | Calcium Silicate + Sulphur 40% | 1.5 + 2.5 |

| (Silicon oxide + Iron) + Sulphur 80% | 0.5 + 3* − 4.8** | / | / |

| Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur 80% | 3.0 + 3* − 4.8** | Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur 40% | 3.0 + 2.5 |

| Untreated control | / | Untreated control | / |

| Leaves | Bunches | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Treatment | Incidence | Severity | Incidence | Severity |

| (%) | (%) | ||||

| 1—Sulphur * | 1.67 b | 0.11 b | 27.67 b | 4.35 b | |

| 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 12.00 c | 0.39 d | |

| 20/06/2022 | 3—Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 14.33 bc | 0.61 d |

| BBCH 73 | 4—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 22.33 bc | 2.04 c |

| 5—Untreated control | 38.00 a | 6.11 a | 54.33 a | 11.42 a | |

| 1—Sulphur | 9.67 b | 0.56 b | 30.00 b | 7.35 b | |

| 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 15.33 c | 1.86 c | |

| 30/06/2022 | 3—Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 18.33 bc | 6.05 b |

| BBCH 75 | 4—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 23.67 bc | 3.56 bc |

| 5—Untreated control | 45.00 a | 9.40 a | 67.00 a | 24.23 a | |

| 1—Sulphur | 16.00 b | 2.37 b | 34.00 b | 6.48 b | |

| 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 0.00 c | 0.00 c | 20.33 c | 3.80 b | |

| 11/07/2022 | 3—Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 0.00 c | 0.00 c | 21.67 bc | 5.33 b |

| BBCH 77 | 4—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 2.33 c | 0.17 c | 29.00 bc | 5.56 b |

| 5—Untreated control | 50.33 a | 13.49 a | 85.00 a | 51.33 a | |

| 1—Sulphur | 23.33 b | 11.95 b | 37.67 b | 9.39 b | |

| 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 0.00 d | 0.00 d | 23.33 c | 6.13 b | |

| 03/08/2022 | 3—Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 7.67 c | 2.85 c | 23.00 c | 8.27 b |

| BBCH 81 | 4—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 10.00 c | 1.85 c | 30.67 bc | 7.32 b |

| 5—Untreated control | 63.33 a | 52.30 a | 91.33 a | 64.07 a | |

| 1—Sulphur | 32.67 b | 15.15 b | 40.33 b | 12.77 b | |

| 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 14.33 d | 1.40 d | 27.33 d | 8.15 c | |

| 13/09/2022 | 3—Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 23.33 c | 3.53 c | 31.67 cd | 9.88 bc |

| BBCH 89 | 4—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 16.67 d | 2.25 cd | 35.33 bc | 10.38 bc |

| 5—Untreated control | 79.00 a | 55.82 a | 93.00 a | 78.90 a | |

| Leaves | Bunches | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Treatment | Incidence | Severity | Incidence | Severity |

| (%) | (%) | ||||

| 1—Sulphur * | / | / | 4.33 b | 1.20 b | |

| 13/07/2023 | 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | / | / | 0.33 c | 0.05 c |

| BBCH 75 | 3—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | / | / | 1.67 c | 0.13 c |

| 4—Untreated control | / | / | 9.33 a | 2.57 a | |

| 1—Sulphur | / | / | 22.00 b | 4.82 b | |

| 18/08/2023 | 2—Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | / | / | 7.00 c | 0.82 c |

| BBCH 89 | 3—Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | / | / | 11.00 c | 1.72 c |

| 4—Untreated control | / | / | 47.33 a | 13.87a | |

| Treatment | Yield * (Kg vine−1) |

Soluble solids (° Brix) | pH | Total acidity (g L−1) | Grape seed weight (g) | Grape berry weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulphur ** | 14.40 b | 16.67 c | 3.29 b | 7.10 a | 0.4 a | 2.4 b |

| Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 17.45 a | 19.03 a | 3.59 a | 4.90 b | 0.5 a | 2.6 a |

| Silicon oxide + Iron + Sulphur | 16.36 a | 18.53 ab | 3.53 a | 5.17 b | 0.5 a | 2.5 ab |

| Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 15.79 a | 19.13 a | 3.55 a | 5.27 b | 0.5 a | 2.6 a |

| Untreated control | 4.75 c | 17.93 b | 3.35 b | 6.30 a | 0.4 a | 2.4 b |

| Treatment | Yield * (Kg vine−1) |

Soluble solids (° Brix) |

pH | Total acidity (g L−1) |

Grape seed weight (g) | Grape berry weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulphur * | 1.63 a | 16.25 a | 2.63 a | 17.87 a | 0.3 a | 1.28 a |

| Calcium Silicate + Sulphur | 1.86 a | 17.45 a | 2.67 a | 16.10 a | 0.3 a | 1.33 a |

| Equisetum arvense L. + Sulphur | 1.87 a | 17.12 a | 2.71 a | 16.27 a | 0.3 a | 1.34 a |

| Untreated control | 1.44 b | 16.22 a | 2.60 a | 17.47 a | 0.3 a | 1.26 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).