Submitted:

27 January 2024

Posted:

31 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and General Growth Conditions

2.2. Phage Enrichment, Isolation, Purification and Amplification

2.3. Phage Host Range and Specificity

2.4. Bacteriophage-Based Biocontrol Assays In Vitro

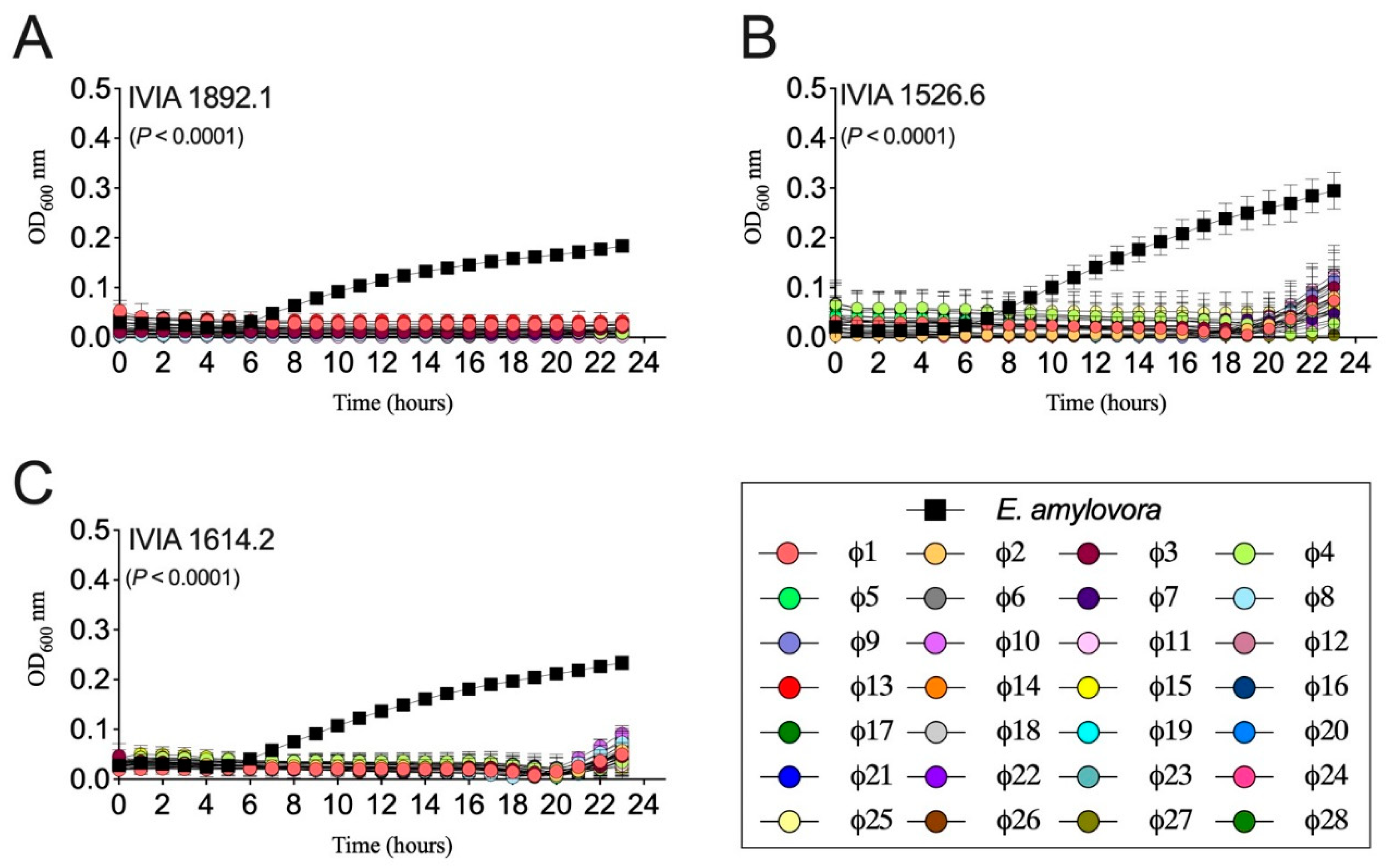

2.4.1. E. amylovora Biocontrol In Vitro by Single Phages.

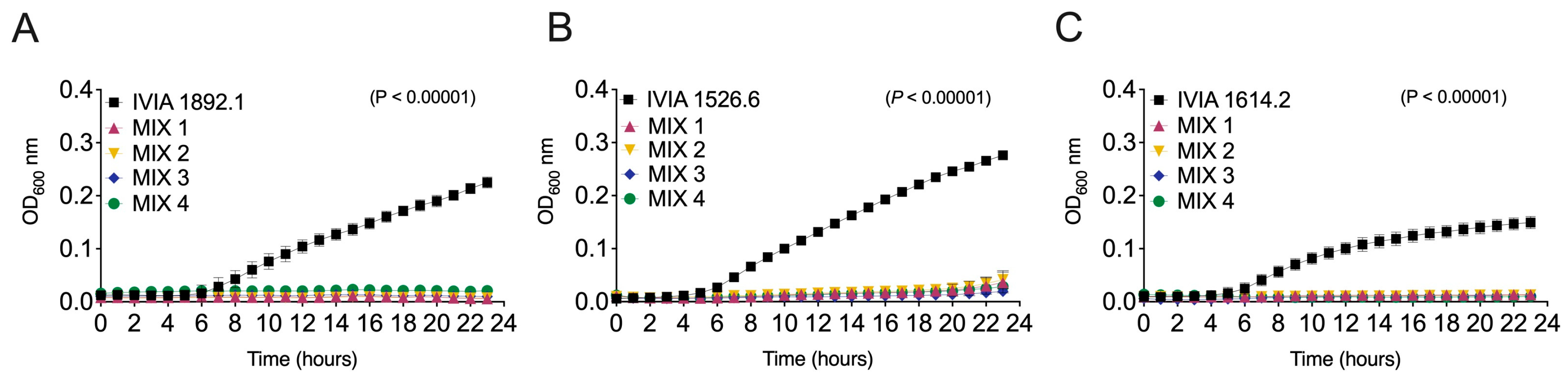

2.4.2. E. amylovora Biocontrol In Vitro by Phage Combinations

2.5. Bacteriophage-Based Biocontrol Assays Ex Vivo

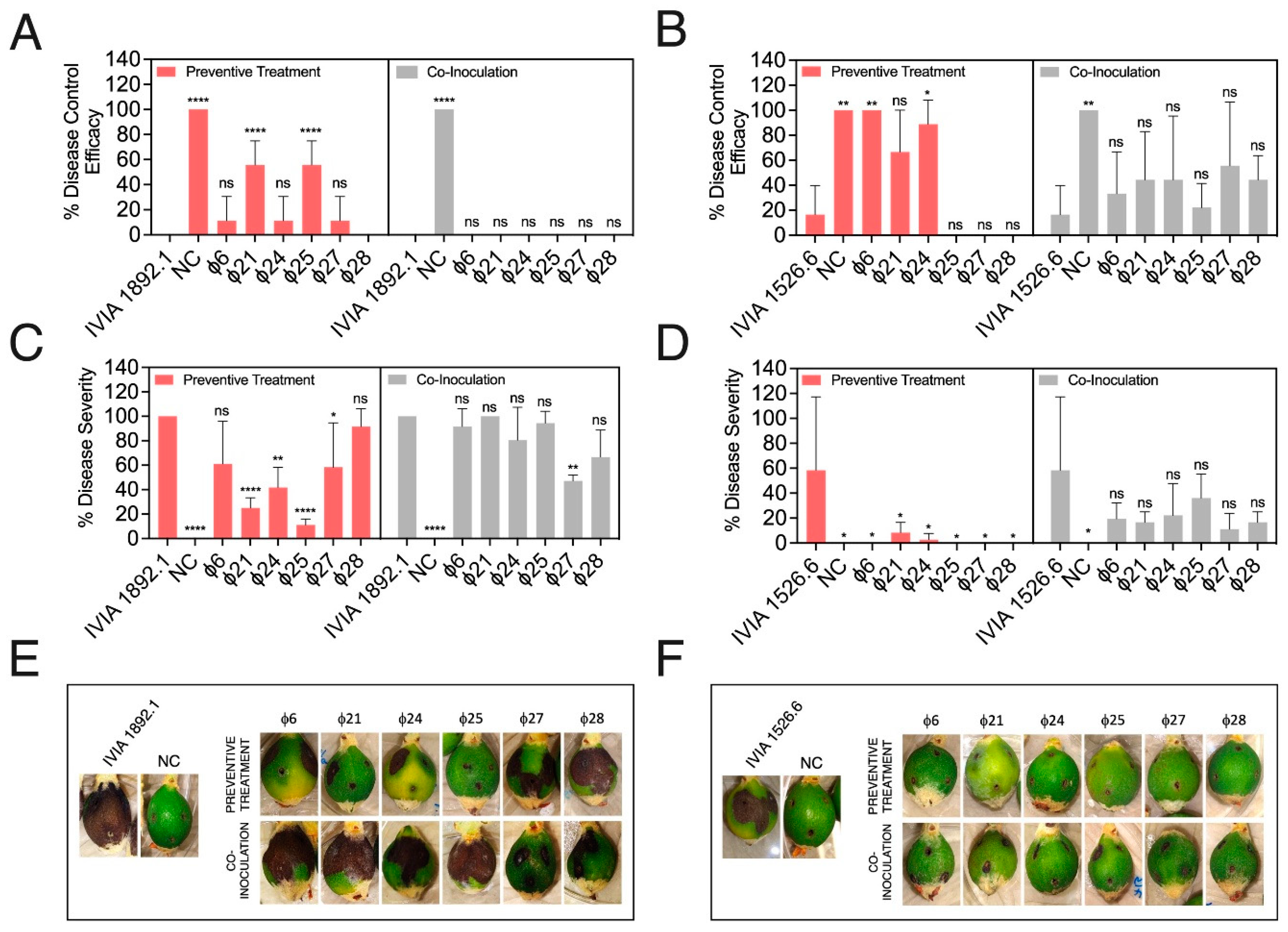

2.5.1. E. amylovora Biocontrol on Immature Fruits by Single Phages

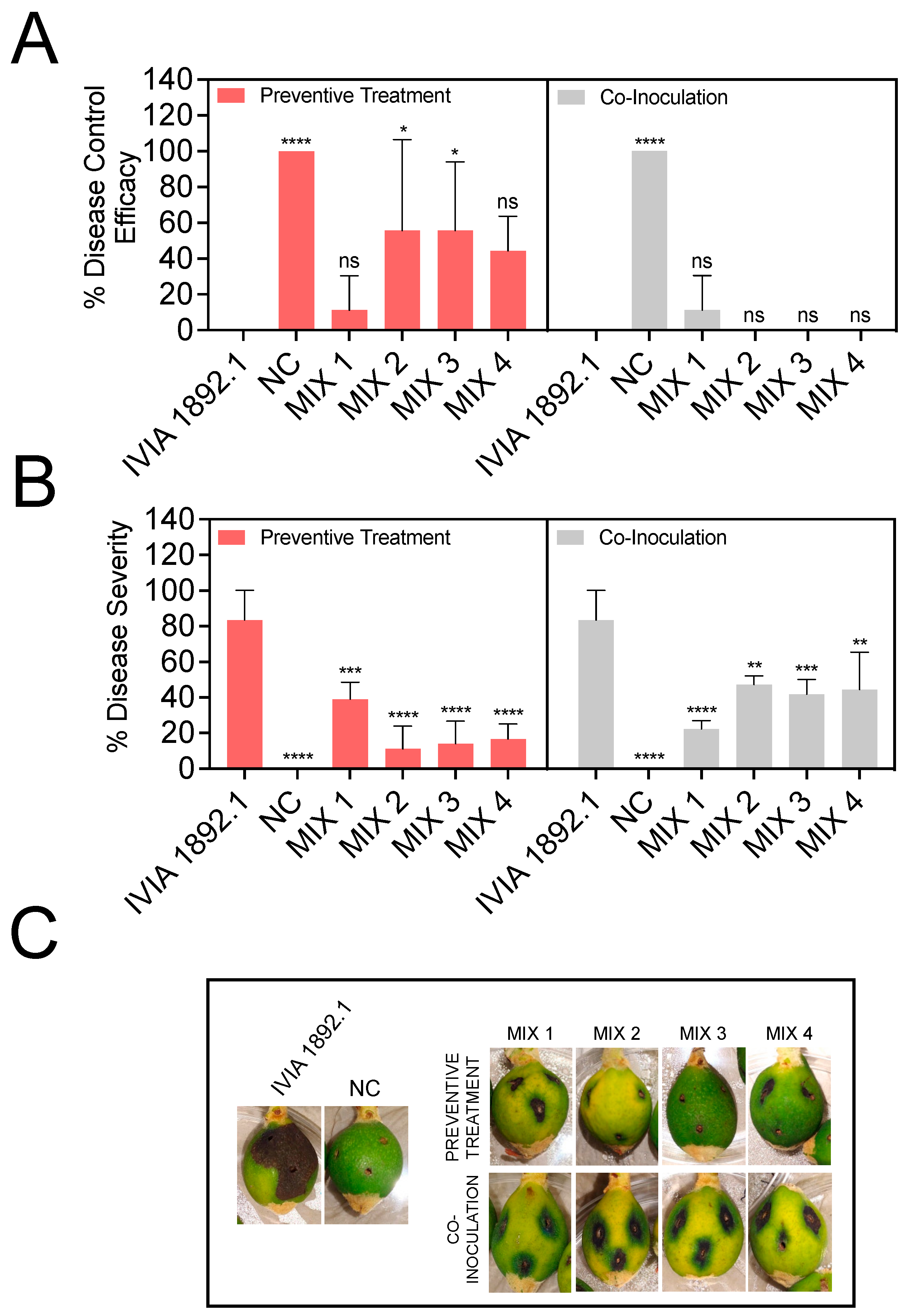

2.5.2. E. amylovora Biocontrol on Immature Fruits by Phage Combinations

2.6. Phage Morphology

2.7. Phage Molecular Characterization

2.7.1. Phage Genome Sequencing

2.7.2. Phage Genome Annotation

2.7.3. Phage Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation of Mediterranean E. amylovora-Specific Bacteriophages was Linked to the Presence of Symptomatic Plant Material

3.2. Mediterranean Bacteriophages were Active against E. amylovora Strains from Different Locations and Hosts

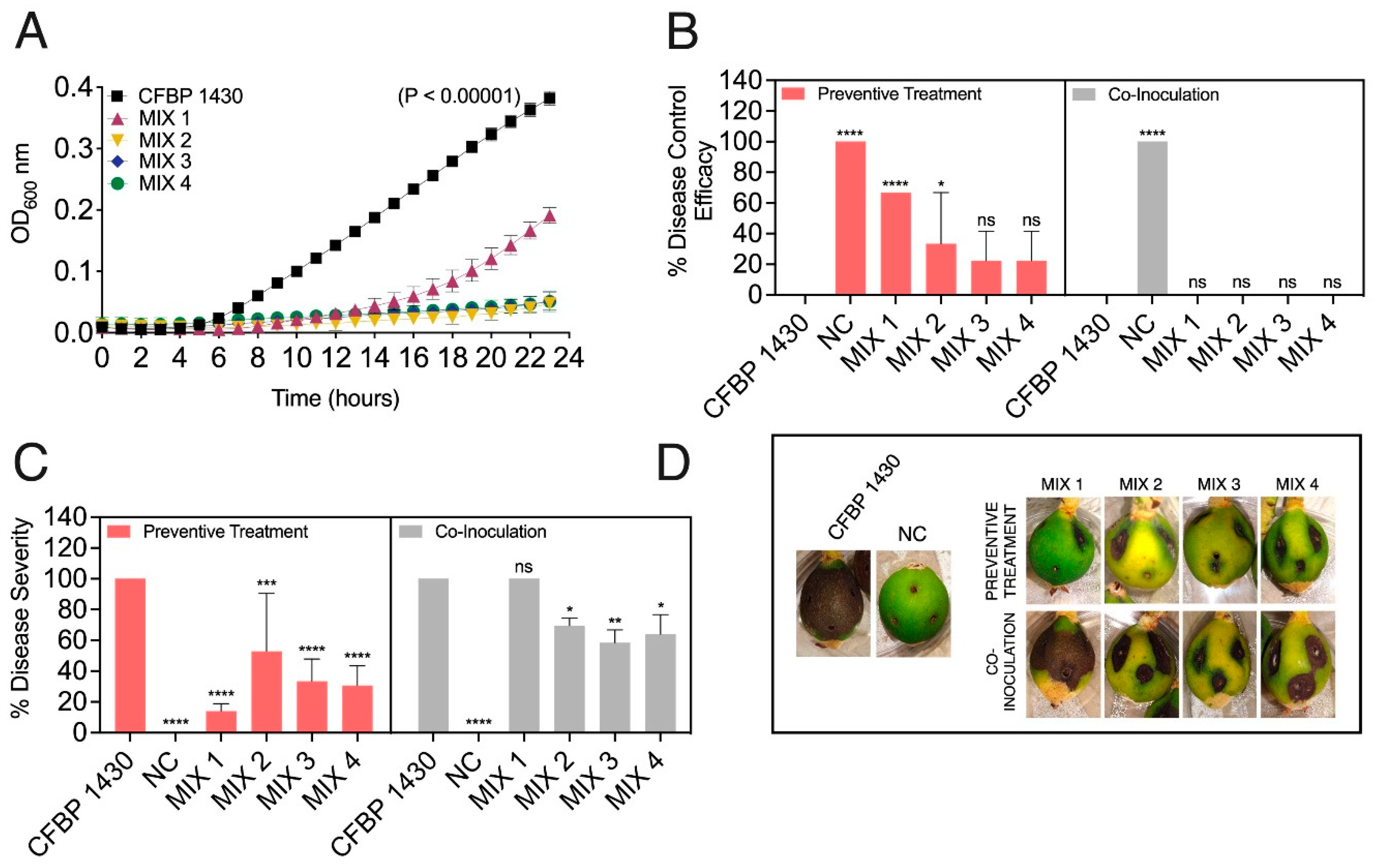

3.3. The Designed Phage Mixes Control E. amylovora Populations Under In Vitro Conditions

3.4. Preventive Application of Phage Mixes Increases the Disease Control Efficacy and Reduces Symptom Severity with Respect to Individual Phages in Detached Fruit Assays

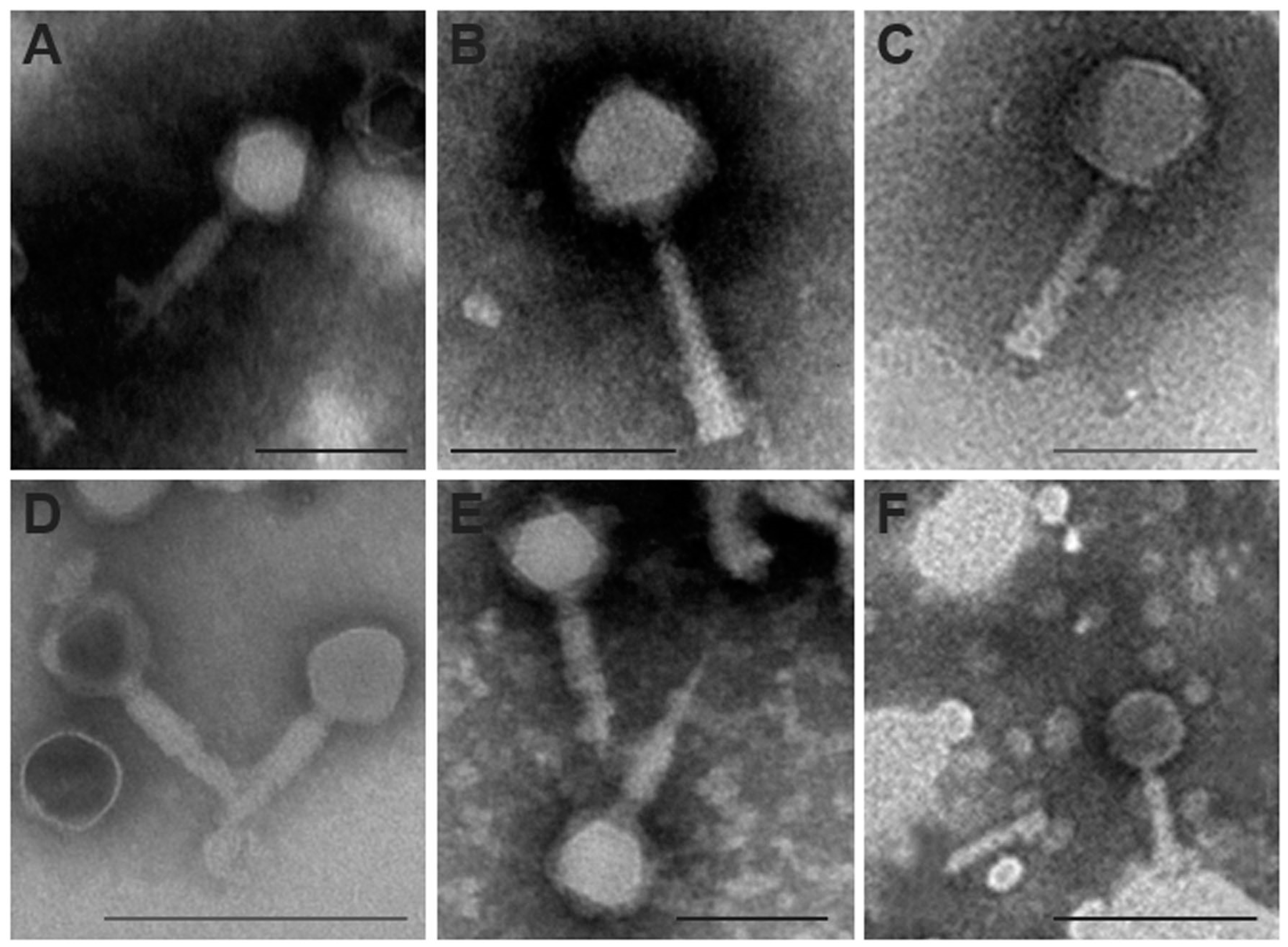

3.5. Mediterranean E. amylovora Phages are Myovirus

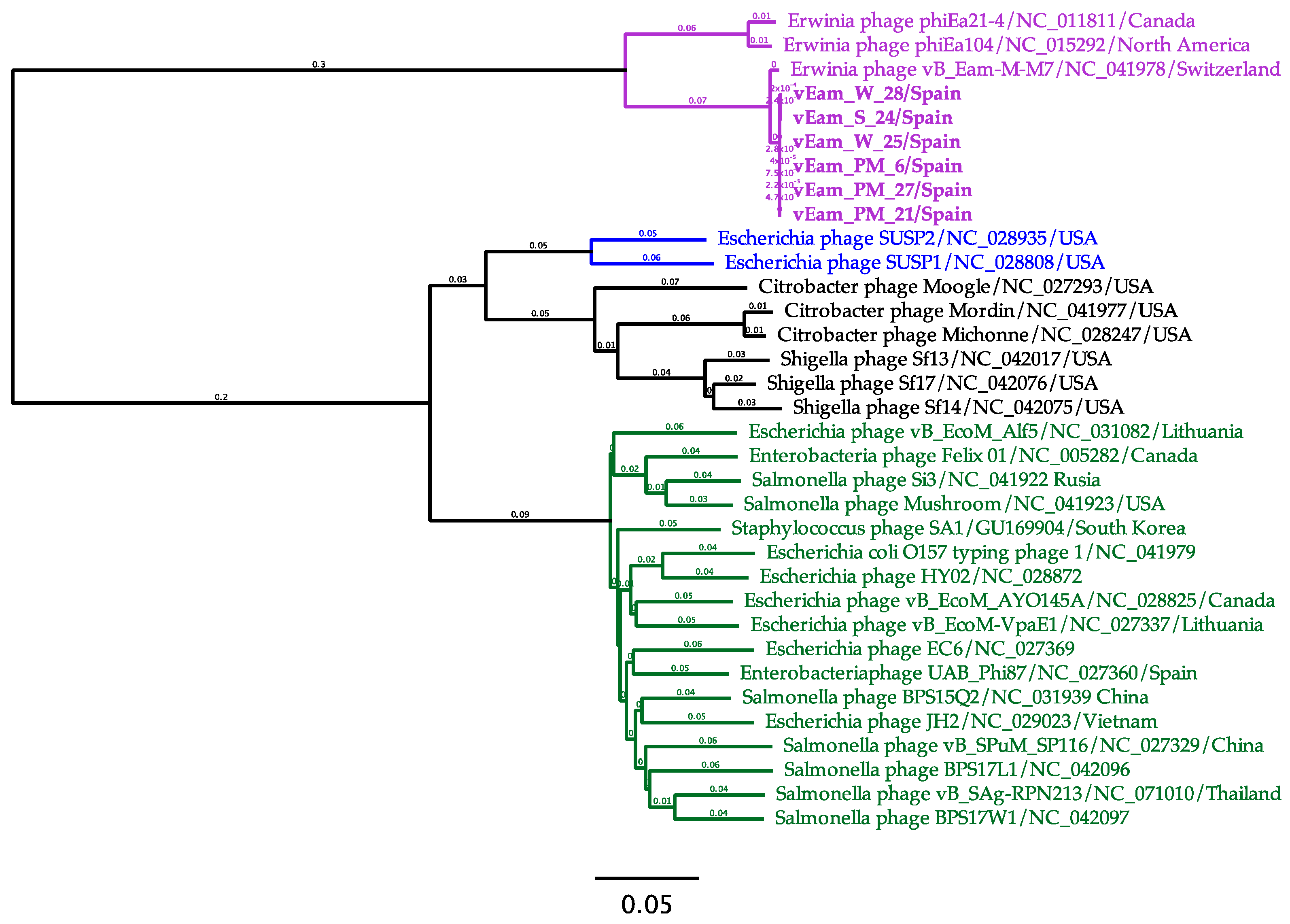

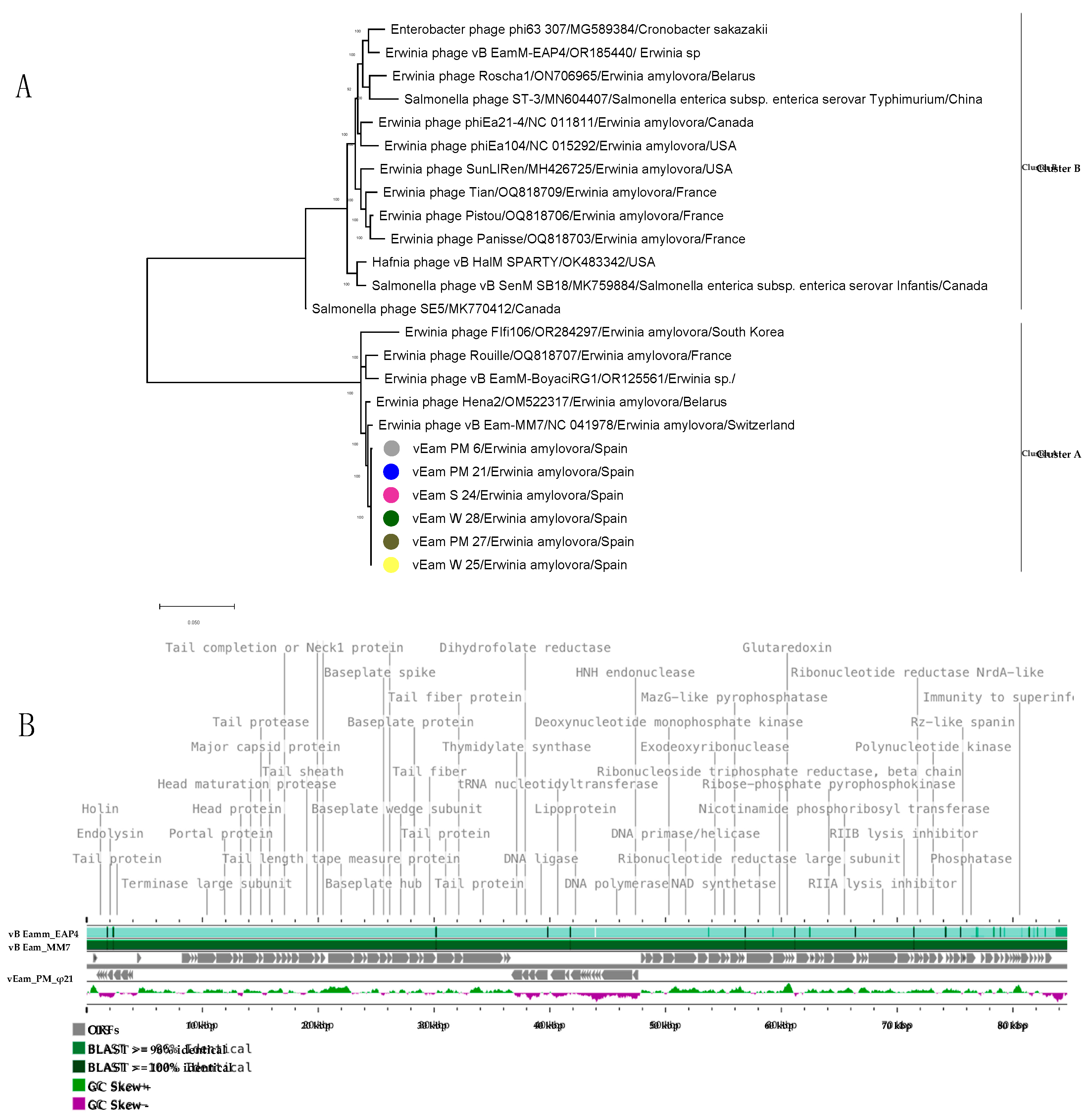

3.6. Mediterranean E. amylovora Bacteriophages are Members of the Genus Kolesnikvirus

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winslow, C.-E.A.; Broadhurst, J.; Buchanan, R.E.; Krumwiede, C.; Rogers, L.A.; Smith, G.H. The Families and Genera of the Bacteria: Final Report of the Committee of the Society of American Bacteriologists on Characterization and Classification of Bacterial Types. J Bacteriol 1920, 5, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.; Gupta, R.S. Genome-Based Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the “Enterobacteriales”: Proposal for Enterobacterales Ord. Nov. Divided into the Families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae Fam. Nov., Pectobacteriaceae Fam. Nov., Yersiniaceae Fam. Nov., Hafniaceae Fam. Nov., Morganellaceae Fam. Nov., and Budviciaceae Fam. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016, 66, 5575–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momol, M.T.; Aldwinckle, H.S. Genetic Diversity and Host Range of Erwinia amylovora. In Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora.; CABI Publishing, 2000; pp. 55–72.

- Van Der Zwet, T.; Orolaza-Halbrendt, N.; Zeller, W.; American Phytopathological Society. Fire Blight : History, Biology, and Management. 2012, 421.

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S. V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 Plant Pathogenic Bacteria in Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusberti, M.; Klemm, U.; Meier, M.S.; Maurhofer, M.; Hunger-Glaser, I. Fire Blight Control: The Struggle Goes On. A Comparison of Different Fire Blight Control Methods in Switzerland with Respect to Biosafety, Efficacy and Durability. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015, 12, 11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, S.G.; Santander, R.D.; Meredith, C.L.; Pavlović, Ž.M. Fire Blight Rootstock Infections Causing Apple Tree Death: A Case Study in High-Density Apple Orchards with Erwinia amylovora Strain Characterization. Frontiers in Horticulture 2023, 2, 1082204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Erwinia amylovora EPPO Global Database. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/ERWIAM (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Anonymous. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 of 28 November 2019 Establishing Uniform Conditions for the Implementation of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 of the European Parliament and the Council, as Regards Protective Measures against Pests of Plants, and Repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 690/2008 and Amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2019. 2019, 1–279.

- Tancos, K.A.; Borejsza-Wysocka, E.; Kuehne, S.; Breth, D.; Cox, K.D. Fire Blight Symptomatic Shoots and the Presence of Erwinia amylovora in Asymptomatic Apple Budwood. Plant Dis 2017, 101, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, H.; McGhee, G.C.; Sundin, G.W.; Adaskaveg, J.E. Characterization of Streptomycin Resistance in Isolates of Erwinia amylovora in California. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, G.W.; Wang, N. Antibiotic Resistance in Plant-Pathogenic Bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2018, 56, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholberg, P.L.; Bedford, K.E.; Haag, P.; Randall, P. Survey of Erwinia amylovora Isolates from British Columbia for Resistance to Bactericides and Virulence on Apple. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2001, 23, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daoude, A.; Arabi, M.I.E.; Ammouneh, H. Studying Erwinia amylovora Isolates from Syria for Copper Resistance and Streptomycin Sensitivity. Journal of Plant Pathology 2009, 91, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Osdaghi, E.; Behlau, F.; Köhl, J.; Jones, J.B.; Aubertot, J.N. Thirteen Decades of Antimicrobial Copper Compounds Applied in Agriculture. A Review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2018 38:3 2018, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Reeder, R. Antibiotic Use on Crops in Low and Middle-Income Countries Based on Recommendations Made by Agricultural Advisors. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience 2020, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Das, K.R.; Naik, M.M. Co-Selection of Multi-Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens in Metal and Microplastic Contaminated Environments: An Emerging Health Threat. Chemosphere 2019, 215, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kering, K.K.; Kibii, B.J.; Wei, H. Biocontrol of Phytobacteria with Bacteriophage Cocktails. Pest Manag Sci 2019, 75, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, F.C.; Squitti, R.; Ventriglia, M.; Cerchiaro, G.; Daher, J.P.; Rocha, J.G.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Moonen, A.C. Agricultural Use of Copper and Its Link to Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteban-Herrero, G.; Álvarez, B.; Santander, R.D.; Biosca, E.G. Screening for Novel Beneficial Environmental Bacteria for an Antagonism-Based Erwinia amylovora Biological Control. Microorganisms 2023, Vol. 11, Page 1795 2023, 11, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.B.; Svircev, A.M.; Obradović, A.Ž. Crop Use of Bacteriophages. Bacteriophages 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, B.; Jones, J.; Iriarte, F.; Momol, M. Phage Therapy for Plant Disease Control. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2010, 11, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doffkay, Z.; Dömötör, D.; Kovács, T.; Rákhely, G. Bacteriophage Therapy against Plant, Animal and Human Pathogens. Acta Biologica Szegediensis 2015, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer, C.; McAuliffe, O.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; O’Mahony, J.; Coffey, A. Bacteriophages and Bacterial Plant Diseases. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 212667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; Biosca, E.G. Bacteriophage-Based Bacterial Wilt Biocontrol for an Environmentally Sustainable Agriculture. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svircev, A.; Roach, D.; Castle, A. Framing the Future with Bacteriophages in Agriculture. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, N.T.; Oh, C.S. Bacteriophage Usage for Bacterial Disease Management and Diagnosis in Plants. Plant Pathol J 2020, 36, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtappels, D.; Fortuna, K.; Lavigne, R.; Wagemans, J. The Future of Phage Biocontrol in Integrated Plant Protection for Sustainable Crop Production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2021, 68, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, K.J.; Holtappels, D.; Venneman, J.; Baeyen, S.; Vallino, M.; Verwilt, P.; Rediers, H.; De Coninck, B.; Maes, M.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; et al. Back to the Roots: Agrobacterium-Specific Phages Show Potential to Disinfect Nutrient Solution from Hydroponic Greenhouses. Appl Environ Microbiol 2023, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Born, Y.; Fieseler, L.; Marazzi, J.; Lurz, R.; Duffy, B.; Loessner, M.J. Novel Virulent and Broad-Host-Range Erwinia amylovora Bacteriophages Reveal a High Degree of Mosaicism and a Relationship to Enterobacteriaceae Phages. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 5945–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulé, J.; Sholberg, P.L.; Lehman, S.M.; O’Gorman, D.T.; Svircev, A.M. Isolation and Characterization of Eight Bacteriophages Infecting Erwinia amylovora and Their Potential as Biological Control Agents in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2011, 33, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.K.; Király, L.; Schwarczinger, I. Phage Therapy for Plant Disease Control with a Focus on Fire Blight. Cent Eur J Biol 2012, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, B.; Song, S.; Lee, Y.W.; Roh, E. Isolation of Nine Bacteriophages Shown Effective against Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Pathol J 2022, 38, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPont, S.T.; Cox, K.; Johnson, K.; Peter, K.; Smith, T.; Munir, M.; Baro, A. Evaluation of Biopesticides for the Control of Erwinia amylovora in Apple and Pear. Journal of Plant Pathology 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, F.B.; Balogh, B.; Momol, M.T.; Smith, L.M.; Wilson, M.; Jones, J.B. Factors Affecting Survival of Bacteriophage on Tomato Leaf Surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 1704–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayder, S.; Kammerecker, S.; Fieseler, L. Biological Control of the Fire Blight Pathogen Erwinia amylovora Using Bacteriophages. Journal of Plant Pathology 2023 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.B.; Vallad, G.E.; Iriarte, F.B.; Obradović, A.; Wernsing, M.H.; Jackson, L.E.; Balogh, B.; Hong, J.C.; Momol, M.T. Considerations for Using Bacteriophages for Plant Disease Control. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, e23857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayder, S.; Parcey, M.; Nesbitt, D.; Castle, A.J.; Svircev, A.M. Population Dynamics between Erwinia amylovora, Pantoea agglomerans and Bacteriophages: Exploiting Synergy and Competition to Improve Phage Cocktail Efficacy. Microorganisms 2020, Vol. 8, Page 1449 2020, 8, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertani, G. Studies on Lysogenesis. I. The Mode of Phage Liberation by Lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1951, 62, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.J.; Svircev, A.M.; Smith, R.; Castle, A.J. Bacteriophages of Erwinia amylovora. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 2133–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimaru, C.; Klos, E. New Medium for Detecting Erwinia amylovora and Its Use in Epidemiological Studies. Phytopathology 1984, 74, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.O.; Ward, M.K.; Raney, D.E. Two Simple Media for the Demonstration of Pyocyanin and Fluorescin. J Lab Clin Med 1954, 44, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lelliott, R.; Stead, D. Methods for the Diagnosis of Bacterial Diseases of Plants. 1987.

- EPPO PM 7/20 (3) Erwinia amylovora. EPPO Bulletin 2022, 52, 198–224. [CrossRef]

- Santander, R.D.; Biosca, E.G. Erwinia amylovora Psychrotrophic Adaptations: Evidence of Pathogenic Potential and Survival at Temperate and Low Environmental Temperatures. PeerJ 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosca, E.G.; Català-Senent, J.F.; Figàs-Segura, À.; Bertolini, E.; López, M.M.; Álvarez, B. Genomic Analysis of the First European Bacteriophages with Depolymerase Activity and Biocontrol Efficacy against the Phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Viruses 2021, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasband, W. ImageJ 1.53m 2022. Available at: https://ij.imjoy.io/ [Accessed December 29, 2023].

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A New Generation of Protein Database Search Programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brettin, T.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; Olson, R.; Overbeek, R.; Parrello, B.; Pusch, G.D.; et al. RASTtk: A Modular and Extensible Implementation of the RAST Algorithm for Building Custom Annotation Pipelines and Annotating Batches of Genomes. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Tynecki, P.; Guziński, A.; Kazimierczak, J.; Jadczuk, M.; Dastych, J.; Onisko, A. PhageAI - Bacteriophage Life Cycle Recognition with Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.07.11.198606. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kuronishi, M.; Uehara, H.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. ViPTree: The Viral Proteomic Tree Server. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besarab, N. V.; Akhremchuk, A.E.; Zlatohurska, M.A.; Romaniuk, L. V.; Valentovich, L.N.; Tovkach, F.I.; Lagonenko, A.L.; Evtushenkov, A.N. Isolation and Characterization of Hena1 – a Novel Erwinia amylovora Bacteriophage. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2020, 367, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biosca, E.G.; Santander, R.D.; Ordax, M.; Marco-Noales, E.; López, M.M. Erwinia amylovora Survives in Natural Water. Acta Hortic 2008, 793, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, R.D.; Català-Senent, J.F.; Marco-Noales, E.; Biosca, E.G. In Planta Recovery of Erwinia amylovora Viable but Nonculturable Cells. Trees - Structure and Function 2012, 26, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, R.D.; Oliver, J.D.; Biosca, E.G. Cellular, Physiological, and Molecular Adaptive Responses of Erwinia amylovora to Starvation. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2014, 88, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, E.; Figàs-Segura, À.; Álvarez, B.; Biosca, E.G. Development of TaqMan Real-Time PCR Protocols for Simultaneous Detection and Quantification of the Bacterial Pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum and Their Specific Lytic Bacteriophages. Viruses 2023, Vol. 15, Page 841 2023, 15, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; López, M.M.; Biosca, E.G. Influence of Native Microbiota on Survival of Ralstonia solanacearum Phylotype II in River Water Microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 7210–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alič, Š.; Naglič, T.; Tušek-Žnidarič, M.; Ravnikar, M.; Rački, N.; Peterka, M.; Dreo, T. Newly Isolated Bacteriophages from the Podoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Myoviridae Families Have Variable Effects on Putative Novel Dickeyas spp. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, M.; El Handi, K.; Valentini, F.; De Stradis, A.; Achbani, E.H.; Benkirane, R.; Resch, G.; Elbeaino, T. Identification and Characterization of Erwinia Phage IT22: A New Bacteriophage-Based Biocontrol against Erwinia amylovora. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Cui, Z.; Wang, J.; Childs, K.L.; Sundin, G.W.; Cooley, D.R.; Yang, C.H.; Garofalo, E.; Eaton, A.; Huntley, R.B.; et al. Comparative Genomics of Spiraeoideae-Infecting Erwinia amylovora Strains Provides Novel Insight to Genetic Diversity and Identifies the Genetic Basis of a Low-Virulence Strain. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, 1652–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayder, S.; Parcey, M.; Castle, A.J.; Svircev, A.M. Host Range of Bacteriophages Against a World-Wide Collection of Erwinia amylovora Determined Using a Quantitative PCR Assay. Viruses 2019, Vol. 11, Page 910 2019, 11, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.K.; Nilsson, A.S. Isolation of Phages for Phage Therapy: A Comparison of Spot Tests and Efficiency of Plating Analyses for Determination of Host Range and Efficacy. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0118557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Ward, S.; Hyman, P. More Is Better: Selecting for Broad Host Range Bacteriophages. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Moreirinha, C.; Lewicka, M.; Almeida, P.; Clemente, C.; Romalde, J.L.; Nunes, M.L.; Almeida, A. Characterization and in vitro Evaluation of New Bacteriophages for the Biocontrol of Escherichia coli. Virus Res 2017, 227, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, M.; Świder, O.; Średnicka, P.; Shymialevich, D.; Ilczuk, T.; Koperski, Ł.; Cieślak, H.; Sokołowska, B.; Juszczuk-Kubiak, E. Newly Isolated Virulent Salmophages for Biocontrol of Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella in Ready-to-Eat Plant-Based Food. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.E.; Delbrück, M. Mutations of Bacteria from Virus Sensitivity to Virus Resistance. Genetics 1943, 28, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechslin, F. Resistance Development to Bacteriophages Occurring during Bacteriophage Therapy. Viruses 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, B.; López, M.M.; Biosca, E.G. Biocontrol of the Major Plant Pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum in Irrigation Water and Host Plants by Novel Waterborne Lytic Bacteriophages. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 492073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, S.J.; Samson, J.E.; Moineau, S. Bacteriophage Resistance Mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmerer, M.; Molineux, I.J.; Bull, J.J. Synergy as a Rationale for Phage Therapy Using Phage Cocktails. PeerJ 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naknaen, A.; Samernate, T.; Wannasrichan, W.; Surachat, K.; Nonejuie, P.; Chaikeeratisak, V. Combination of Genetically Diverse Pseudomonas Phages Enhances the Cocktail Efficiency against Bacteria. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Quiroz, R.C.; Camilli, A.; Silva-Valenzuela, C.A. Role of Bacteriophages in the Evolution of Pathogenic Vibrios and Lessons for Phage Therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol 2023, 1404, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapes, A.C.; Trautner, B.W.; Liao, K.S.; Ramig, R.F. Development of Expanded Host Range Phage Active on Biofilms of Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bacteriophage 2016, 6, e1096995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castledine, M.; Padfield, D.; Sierocinski, P.; Pascual, J.S.; Hughes, A.; Mäkinen, L.; Friman, V.P.; Pirnay, J.P.; Merabishvili, M.; De Vos, D.; et al. Parallel Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phage Resistance and Virulence Loss in Response to Phage Treatment in vivo and in vitro. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, P.; Tabla, R.; Anany, H.; Bastias, R.; Brøndsted, L.; Casado, S.; Cifuentes, P.; Deaton, J.; Denes, T.G.; Islam, M.A.; et al. ECOPHAGE: Combating Antimicrobial Resistance Using Bacteriophages for Eco-Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems. Viruses 2023, Vol. 15, Page 2224 2023, 15, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstoy, I.; Kropinski, A.M.; Brister, J.R. Bacteriophage Taxonomy: An Evolving Discipline. Methods in Molecular Biology 2018, 1693, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.; Shkoporov, A.N.; Lood, C.; Millard, A.D.; Dutilh, B.E.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; van Zyl, L.J.; Aziz, R.K.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M.; et al. Abolishment of Morphology-Based Taxa and Change to Binomial Species Names: 2022 Taxonomy Update of the ICTV Bacterial Viruses Subcommittee. Arch Virol 2023, 168, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, R.A.; Pitman, A.R.; Fineran, P.C. Advances in Bacteriophage-Mediated Control of Plant Pathogens. Int J Microbiol 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly-Chatain, M.H. The Factors Affecting Effectiveness of Treatment in Phages Therapy. Front Microbiol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| E. amylovora strain code | Host | Geographical origin | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | |||

| UPN1 527 | Malus x domestica | Navarra | 1997 |

| IVIA2 1526.6 | Cotoneaster sp. | Guipúzcoa | 1996 |

| IVIA 1554 | Crataegus sp. | Segovia | 1996 |

| IVIA 1596 | Pyrus sp. | Spain | 1996 |

| IVIA 1614.1 | Pyracantha sp. | Spain | 1996 |

| IVIA 1614.2 | Cotoneaster sp. | Segovia | 1996 |

| IVIA 1626.6 | M. domestica | Navarra | 1996 |

| IVIA 1892.1 | Pyrus sp. | Guadalajara | 1998 |

| UV3 P3P2AA1 | Pyrus communis | Valencia* | 2018 |

| UV P4P2AA1 | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| UV P2P4TA1 | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| UV P2P4TA2.1 | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| UV P2EP4Tex | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| UV P3P4TA1 | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| UV P3P4TA2 | P. communis | Valencia | 2018 |

| International | |||

| CFBP4 1430 | Crataegus oxyacantha | France | 1972 |

| NCPPB 5 311 | P. communis | Canada | 1952 |

| Ea273 | Malus sp. | USA | 1971 |

| CGJ2 | Malus sp. | Serbia | 2003 |

| Bacterial species | Strain code | Host | Geographical origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clavibacter michiganensis | IVIA1 873 | Solanum lycopersicum | Spain |

| Dickeya sp. | IVIA 4830 | S. lycopersicum | Spain |

| Pectobacterium atrosepticum | IVIA 3447 | S. tuberosum | Spain |

| P. carotovorum | IVIA 3902 | S. lycopersicum | Spain |

| Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi | IVIA 1628.3 | Olea europaea | Spain |

| Rhizobium radiobacter | C58 | Prunus avium | USA |

| R. rhizogenes | K84 | Non-pathogenic | Australia |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | IVIA 1670 | S. tuberosum | Spain |

| Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni | CITA2 33 | Prunus amygdalus | Spain |

| X. vesicatoria | CECT3 792 | Unknown | Israel |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | CECT 5173 | Freshwater | France |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | CECT 928 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Bacillus cereus | CECT 495 | Chicken and turkey manure | Unknown |

| Enterococcus faecalis | CECT 481 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Escherichia coli | CECT 101 | Unknown | United Kingdom |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | CECT 143 | Unknown | United States |

| Kocuria rhizophila | CECT 241 | Soil | Unknown |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | CECT 378 | Pre-filter tanks, town water works | United Kingdom |

| Proteus hauseri | CECT 484 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica | CECT 443 | Human food poisoning | United Kingdom |

| Serratia marcescens | CECT 159 | Unknown | Unknown |

| Staphylococcus aureus | CECT 4013 | Bovine mammary gland | Unknown |

| Host strain code | UV E. amylovora bacteriophages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ϕ1 | ϕ2 | ϕ3 | ϕ4 | ϕ5 | ϕ6 | ϕ7 | ϕ8 | ϕ9 | ϕ10 | ϕ11 | ϕ12 | ϕ13 | ϕ14 | ϕ15 | ϕ16 | ϕ17 | ϕ18 | ϕ19 | ϕ20 | ϕ21 | ϕ22 | ϕ23 | ϕ24 | ϕ25 | ϕ26 | ϕ27 | ϕ28 | |

| E. amylovora UPN 527 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1526.6 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1554 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1596 | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | + | W | - | - | W | W | - | - | - | W | W | - | W | + | W | - | -/+ | W | + | -/+ | -/+ |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1614.1 | + | + | W | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | W | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | + | + |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1614.2 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | -/+ | + |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1626.6 | W | W | - | W | W | W | - | - | - | W | - | - | W | - | - | W | W | - | - | - | -/+ | - | - | -/+ | -/+ | W | W | -/+ |

| E. amylovora IVIA 1892.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | -/+ | + | + | -/+ | -/+ |

| E. amylovora UV P3P2AA1 | W | - | W | W | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | W | - | W | W | W | W | W | + | - | - | W | + | + | W | W |

| E. amylovora UV P4P2AA1 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| E. amylovora UV P2P4TA1 | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | -/+ | + | + | -/+ | -/+ |

| E. amylovora UV P2P4TA2.1 | + | + | W | + | + | W | W | W | W | W | - | - | + | + | W | - | - | - | - | - | W | W | - | -/+ | + | W | + | -/+ |

| E. amylovora UV P2exP4T | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | W | W | + | - | W | W | + | + | + | W |

| E. amylovora UV P3P4TA1 | + | + | - | + | + | W | W | W | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | + | + |

| E. amylovora UV P3P4TA2 | + | + | W | + | + | W | W | W | W | + | + | + | + | W | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | + | + | + | W | + | + | + |

| E. amylovora CFBP 1430 | - | - | - | W | - | W | - | W | - | W | + | + | - | + | + | W | W | + | + | + | -/+ | + | + | + | -/+ | - | -/+ | W |

| E. amylovora NCPPB 311 | W | W | + | W | W | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | + | W | W | + | W | W | W | + | + | W | W |

| E. amylovora GJ-2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | W | W | W | W | + | + | W | W | W | W | W | W | + | W | W | W | + | W | + | W |

| E. amylovora 273 | - | - | - | - | - | W | - | - | - | W | - | W | - | - | W | W | - | W | W | W | W | W | - | W | - | W | - | - |

| C. michiganensis IVIA 873 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dickeya sp. IVIA 4830 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. atrosepticum IVIA 3447 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. carotovorum IVIA 3902 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. savastanoi IVIA 1628.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R. radiobacter C58 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R. rhizogenes K84 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R. solanacearum IVIA 1670 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X. arboricola pv. pruni CITA 33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X. vesicatoria CECT 792 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A. hydrophila CECT 5173 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A. faecalis CECT 928 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| B. cereus CECT 495 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| E. faecalis CECT 481 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| E. coli CECT 101 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| K. pneumoniae CECT 143 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| K. rhizophila CECT 241 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. fluorescens CECT 378 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. hauseri CECT 484 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| S. enterica CECT 443 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| S. marcescens CECT 159 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| S. aureus CECT 4013 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| E. amylovora strains lysed (%) | 84 | 68 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 100 | 84 | 90 | 79 | 74 | 58 | 68 | 84 | 84 | 63 | 84 | 90 | 74 | 80 | 79 | 90 | 74 | 68 | 74 | 84 | 95 | 68 | 68 |

| Non-E. amylovora species lysed (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).