1. Introduction

Steel, a fundamental material in numerous industries such as construction, manufacturing and energy, was produced in the order of 1.9 billion tons worldwide in 2022 [

1]. Despite its widespread benefits, steel production is associated with significant environmental problems, in particular high energy consumption and significant

emissions. With steel demand expected to increase by 30% over the next three decades, there is an urgent need for more sustainable production methods [

2]. Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) offer a promising solution as they enable steel production from scrap steel and direct reduced iron (DRI). In addition, recent advances in EAF technology have led to improvements such as shorter tap-to-tap times, lower energy consumption through the introduction of carbon monoxide post-combustion and melt stirring techniques. Furthermore, digitalization and the application of advanced technologies, e.g., machine learning, have shown great potential for further optimization of the steel production process, i.e., temperature soft sensors [

3] and slag foaming estimation [

4]. These technologies enable the analysis and utilization of large datasets and provide valuable insights for optimizing production parameters and reducing environmental impact. In the metallurgical industry, especially in the EAF operation, accurate real-time measurements of key performance indicators (KPIs) are essential for high productivity. However, challenges such as cost and data acquisition limitations often hinder the direct measurement of critical variables. Soft sensors, which use indirect measurements to estimate hard-to-measure process variables, have proven to be a cost-effective and adaptable solution. These models, ranging from fuzzy [

3] and neural network models [

4] to comprehensive theoretical models [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], are central to improving process control and plant efficiency.

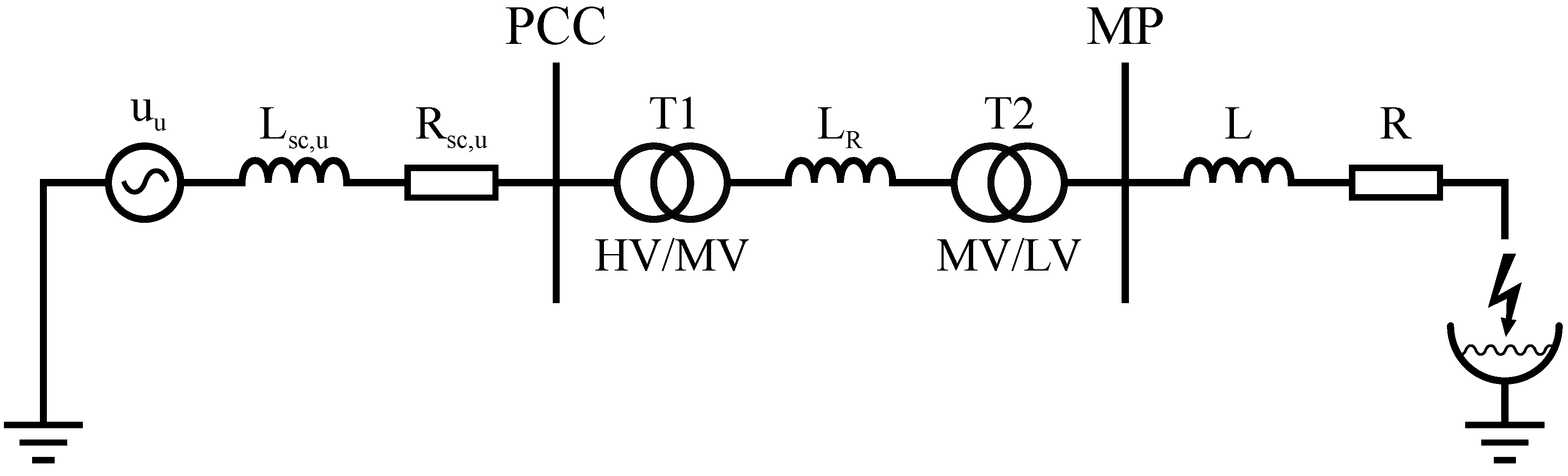

One of the critical aspects of three-phase alternating current (AC) EAFs is the architecture of the power supply system, depicted in

Figure 1. This system consists of a series of components, starting with the intake of electric power from the utility grid, referred to as

. At the point of common coupling (PCC), which is characterized by the short-circuit resistance

and the inductance

, the grid is connected to a high/medium voltage step-down transformer (HV/MV T1). The secondary side of HV/MV T1 then feeds into the arc furnace transformer, a medium/low voltage transformer (MV/LV T2), via a series reactor

which serves to increase the overall reactance of the system [

10]. The MV/LV T2 is equipped with a variable tapping mechanism that makes it possible to adjust the turns ratio under load and thus regulate the voltage supplied to the EAF. The measuring point (MP) is located on the secondary side of the arc furnace transformer and enables the measurement of the line-to-ground voltages and line currents. The line current flows through conductors consisting of flexible cables and tubular conductors leading to the graphite electrodes, which are modeled as reactance

R and inductance

L. At the point where these electrodes meet the conductive metal scrap, an electric arc is formed, which closes the circuit that is grounded via the furnace hearth. The dynamic control of the arc intensity is ensured by the precise vertical adjustment of the electrodes. This adjustment is performed by an electrode control system designed to maintain specific current or impedance parameters for each line [

11].

In an effort to increase efficiency and reduce operating costs of the EAFs, great attention is being paid to optimizing the electric arcs, which are responsible for a significant portion of the energy consumption. It is estimated that around 80% of the energy emitted by an electric arc occurs as radiation [

5]. This underlines the importance of directing this radiation to the heating of scrap and molten steel rather than letting it dissipate on the furnace roof and cooling panels. The intensity of arc radiation is directly proportional to arc length and voltage, which means that longer arcs generally emit more radiation. However, longer arcs can affect stability and lead to increased radiation dispersion away from the melt. The use of foaming slag is therefore crucial for the complete coverage of arcs to minimize radiation losses and improve energy transfer to the molten metal [

12], as well as to stabilize the arc’s burning behavior and increase the efficiency of the power input [

13]. A major challenge is to accurately measure the coverage of the arc by slag, as direct visual access is not possible and the installation of sensors inside the furnace is impractical [

14]. Various methodologies, such as laser vibrometry [

4,

14], imaging through the slag gate [

4] and analyzing the secondary side transformer voltage [

15] and current [

13] have been explored. One notable approach is the use of a laser vibrometer to measure real-time vibrations of the furnace shell in combination with the operator’s estimation of arc coverage. This data is then used to train an artificial neural network that estimates the arc coverage [

14]. However, it is important to note that these estimates depend on the experience of the operator. In addition, Martell et al. [

15] have proposed an arc coverage index based on the third and ninth harmonic values of the voltage between the virtual-neutral and ground. While this index provides a general assessment of arc coverage, it does not provide insight into individual arc coverage. Furthermore, Sedivy et al. [

13] proposed an index for foaming slag that suggests an inverse relationship to the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) of the current. Finally, Son et al. [

4] developed a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network model for estimating slag foaming height in EAF steelmaking by integrating preprocessed EAF heat data with reference data from measured furnace shell vibration and digital imaging [

4]. However, a critical challenge is estimating the height of the foaming slag from images taken through the slag gate. This process is inherently complex as the initial level of the molten metal surface is indeterminate, making the accurate determination of the height of the slag foam much more difficult.

Another crucial aspect of the EAF operation is arc stability, which significantly affects both electrical phenomena and operational power level. Arc instability can affect the system’s ability to deliver high-power, leading to operational inefficiencies. Conversely, stable arcs enable higher power output, resulting in shorter tapping times, higher productivity and steel quality [

16]. Various methodologies have been used to evaluate arc stability, including analysis of secondary-side transformer voltages or line currents [

15,

16,

17] and the evaluation of acoustic signals [

18]. An important stability indicator in the frequency domain is the THD of the voltage or current signal [

17]. THD values vary in the different EAF heating stages and generally show increased values during the initial bore-down and early melting stages, which then decrease during the refining stages. Martell et al. [

16] have introduced a stability index based on the RMS voltage between the virtual-neutral of the EAF delta transformer and ground. In addition, arc stability can be evaluated by analyzing acoustic signals, where a stability index is derived by examining both the time and frequency domain of these signals [

18]. Arc stability is not only a reflection of the electrical behavior in the furnace, but also a crucial process variable that, together with the specific heat stage, determines the EAF’s operational power level. Understanding and controlling arc stability is critical to operational efficiency as it allows the power profile to be adjusted to the stability conditions of the arc. Effective control strategies in this area require comprehensive arc models. A variety of approaches to arc modeling can be found in the literature, including linear and nonlinear, static and dynamic methods that include both time-variant and invariant aspects as well as black-box and white-box approaches [

19]. The following sections provide an overview of these arc models and explain their application and effectiveness in the operation of EAF.

The origins of arc models can be traced back almost a century, with Cassie’s model being introduced in 1939 [

20] and Mayr’s model in 1943 [

21]. The Mayr model was developed specifically for low-current applications and is particularly effective in the zero-crossing region, whereas the Cassie model is more suitable for high-current situations. The relatively simple Cassie and Mayr differential equation models can effectively model the key characteristics of the arc as a circuit element, with arc resistance defined as a dynamic variable. Based on the simplifications of principal power-loss mechanisms and energy storage in the arc column, they serve as valuable tools to understand arcing phenomena. In an effort to develop more comprehensive models, several approaches have been proposed to merge the arc models of Cassie and Mayr. One approach is to use a current-based transition function, where a Mayr model is active near zero current, while the Cassie arc model is active at higher currents [

22,

23]. Another possibility is to generalize the Cassie and Mayr arc model by introducing an additional parameter denoted as

[

19,

24,

25]. Setting

to zero yields the Mayr model, while setting it to one produces the Cassie model. The theoretical range for

is between 0.5 and 1, as stated by Lee et al. [

24], although it is worth noting that experimental data suggests that

values greater than one are possible. Khakpour et. al [

26] proposed an improved Mayr arc model in which the dissipated power at current passage through the zero point was defined in terms of the arc current and the estimated arc diameter. The hyperparameters of the arc model were then estimated using measurements from a dedicated experimental setup. In addition to the EAFs, the circuit breaker models [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] also utilize the arc models with more advanced adaptations of Mayr’s and Cassie’s models, i.e., the Schwarz arc model, the Habedank arc model and the KEMA arc model [

30,

31]. However, these models introduce additional parameters, which makes their identification even more difficult.

In 1990, Acha et al. [

32] introduced a novel arc modeling methodology known as the power balance equation. This dynamic arc model is based on a system of differential equations, collectively referred to as the power balance equation. The basic premise of this approach revolves around establishing an equilibrium in which the total power generated in the arc equals the power dissipated to the surroundings and the power contributing to the arc’s internal energy. The radius of the arc is chosen as the state variable and forms the core of the differential equation. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to analyzing and determining the parameters inherent in the power balance equation. Various methodologies have been explored, including analytical solutions [

33,

34], as well as optimization techniques such as Monte Carlo [

35], genetic algorithms [

35,

36,

37] and particle swarm optimization [

36]. In addition, efforts have been made to understand the stochastic properties of these parameters using approaches such as the ARIMA model [

35] and the LSTM neural network [

37]. In the paper [

33] it has been found that the parameters significantly change during the EAF stages, i.e., melting stage and the refining stage. However, it is worth noting that these methods often restrict the power balance equation to a particular scenario characterized by the values

and

.

MagnetoHydroDynamic (MHD) models represent the most complete type of plasma modeling and provide comprehensive insights into the behavior of electric arcs. These models require the solution of a complex set of differential equations that include Maxwell’s equations, the Navier-Stokes equations modified by the Lorentz force, and the energy equations that account for the Joule heating effect [

38]. MHD theory was also applied to understand the parameter values of the Cassie-Mayr hybrid arc model [

23]. However, despite their thoroughness, a major challenge in MHD modeling is the scarcity of precise data on the physical properties of the plasma gas. Furthermore, the need for fine discretization in these models, which is essential for accurate system estimations, leads to significant computational requirements, making industrial real-time applications a challenge. In response, Channel Arc Models (CAM) were developed as a more computationally tractable alternative. These models introduce several simplifications to reduce complexity. Key assumptions include the establishment of a local thermodynamic equilibrium, the conception of the arc as an ionized gas channel with axial symmetry, and the homogeneity of current and temperature distributions across the channel diameter [

39,

40,

41]. Although CAM are less complex than MHD models, they still pose the task of estimating numerous model parameters. While this parameter estimation requirement is less daunting than for MHD models, it remains a non-trivial aspect of channel arc modeling that affects both the accuracy of the model and its applicability in various industrial scenarios.

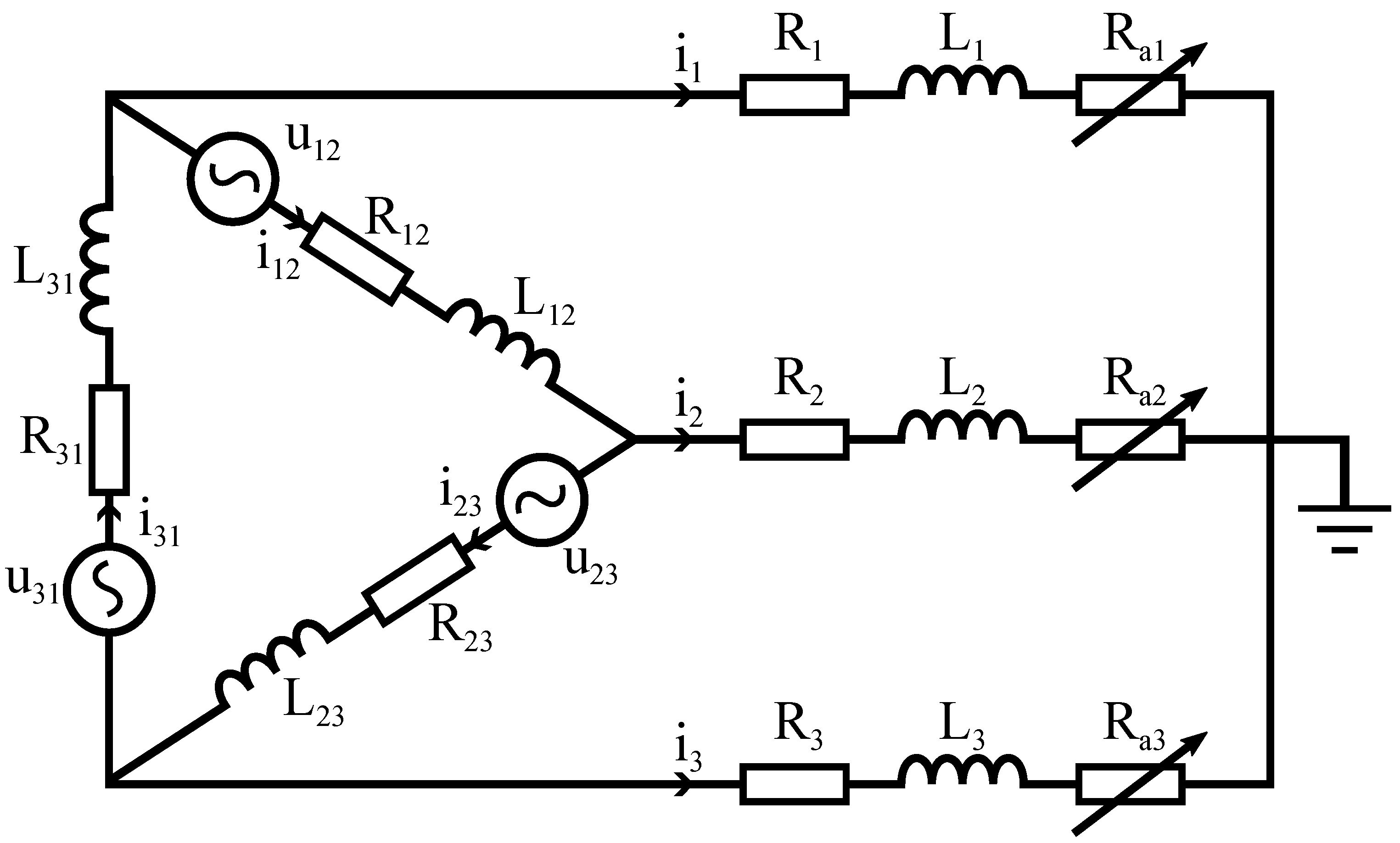

This article presents a holistic approach for the electrical analysis of three-phase AC EAF and introduces a novel Arc Quality Index (AQI) based on the Cassie-Mayr arc model. The approach is based on a three-phase equivalent circuit that integrates the Cassie-Mayr arc model to capture the nonlinear and time-varying load characteristics of electric arcs. The model also takes into account the processes of arc breakage and ignition, thus improving the accuracy in representing the dynamic behavior of arcs, especially during the chaotic melting stage. The parameters of the Cassie-Mayr arc model, in particular the arc time constant and the Cassie-Mayr constant for each electrode, are determined using a particle swarm optimization technique. This estimation is performed using real furnace data collected during a single heat that included both the melting and refining stages. The optimization objective or fitness function is defined by minimizing the discrepancy between the harmonic content of the measured and simulated voltage and current signals. The AQI is formulated based on the deviations from the optimum conditions utilizing the Cassie-Mayr arc parameters and the RMS value of arc resistance. This index provides a thorough qualitative assessment of arc quality, analogous to indices such as the arc coverage index and the arc stability index. In addition, the AQI is based solely on the measurements of current and voltage, which can be measured on-site to assess arc quality. Effective monitoring and control of the AQI enables operators to improve the operation of the EAF and thus increase the efficiency of steel production. Achieving high AQI values is desirable, at least in the later stages of EAF operation, in order to minimize energy losses caused by radiation. At this point, the extent of arc coverage by slag proves to be a decisive factor for the AQI value and the overall EAF. Consequently, operators can take targeted measures to improve AQI, including adjustments to reduce arc length and initiatives to increase slag height, thereby optimizing operating conditions and energy utilization. This research demonstrates the importance of understanding arc dynamics in EAFs to promote more efficient and sustainable steel production techniques. Contributions of the work include: the development of a holistic electrical circuit for EAF based on the Cassie-Mayr arc model, an optimization method for parameter estimation of the Cassie-Mayr model across all three lines, and the formulation of a novel arc quality index that integrates aspects of arc stability and coverage.

3. Parameter Optimization

This section describes the methodology used to estimate the arc parameters in an EAF during the melting and refining stages. The dataset utilized for the analysis consists of line-to-ground voltage measurements, denoted by

(where the subscript

l denotes the line

and

m denotes the measurement), and line current measurements, represented by

. To enable effective parameter estimation, the analysis focuses on a single signal period and assumes that the arc parameters remain constant within this time frame. This hypothesis simplifies the analysis while maintaining its relevance within the dynamic environment of the EAF. This approach is in line with similar practices in the field, where the authors have opted for a half-period for optimization [

19,

36]. The main objective is to estimate two critical Cassie-Mayr parameters for each line

l: the arc parameter

and the time constant

. To achieve this, the Equation (

25) is used to simulate the EAF system over a complete signal period. The simulated line-to-ground voltage

and the line current

are derived from the state space vector and its derivative, where

s denotes the simulated values. The line-to-ground voltage

is calculated as follows:

The analytical process includes a Fourier series analysis to determine the magnitude of the measured and simulated signals for harmonics up to the

-th order. This harmonic analysis is crucial for capturing the complex electrical behavior of the EAF. The term

h in the analysis stands for the

h-th harmonic and enables a detailed investigation of the electrical properties at different harmonic levels. For example,

stands for the magnitude of the

l-th line-to-ground voltage measurement for the

h-th harmonic, which provides insight into the harmonic distribution and its impact on the operation of the EAF. To optimize arc parameters, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) was employed, leveraging its capability for nonlinear function optimization [

43,

44]. This technique involves multi-candidate solutions, known as ’particles’, concurrently exploring the search space to minimize a predefined fitness function. Particles dynamically adjust their positions based on their own experiences and those of their neighbors. The fitness function is defined as follows:

where

and

represent the voltage and current fitness functions for the

l-th line, respectively. The hyperparameter

, ranging from 0 to 1, balances the focus between minimizing voltage

and current

components. Higher

values prioritize voltage minimization, while lower values focus on current minimization. The fitness functions for voltage and current part are thus defined as follows:

where the minimization of the root mean square of the magnitude differences of measured and simulated signals for harmonics up to

is desired. Furthermore, the fitness functions are normalized by the maximum fundamental harmonic of the measured signal in all the lines. This ensures that the values of the

and

are comparable in scale, which enables parameter

to be more easily tuned.

3.1. Initial Parameter Selection

Before optimization, initialization of the three-phase Cassie-Mayr model of the EAF is essential. The initialization includes the determination of the initial condition of the state vector

and the initial phase angle of the secondary voltages of the transformers

. The initial states of the first two line currents,

and

, are determined directly on the basis of the measured line currents

and

. However, as the phase current

is not measured directly, its initial state is estimated using the phasor analysis as follows:

where the initial state

is defined as the real part of

. In addition, the initial phase angle of the secondary transformer voltages is initialized using the following expression:

The initial arc resistances

in the model are calculated according to the Equation (

31) as follows:

Note that the initial arc resistance tends to infinity as the current

approaches zero, which is a mathematical consequence of their inverse relationship. To take this into account and maintain numerical stability, the resistance is saturated at the threshold

. In addition, the arc voltage

cannot be measured directly and is therefore estimated using the basic relationship equation from (

32) as follows:

where

k represents the

k-th measurement and

denotes the estimated derivative of the current. Since the phase

and the initial phase current

are estimated using phasors, the nonlinear nature of the system leads to some estimation errors. To improve the model initialization, the system is simulated over a complete time period, with the final simulation value serving as initial conditions

. This procedure assumes that the arc has reached a stable state at the end of the simulation period. Given the periodicity of the system, a consistent value of the state vector is expected over successive periods. However, the applicability of this method depends on the stability of all arcs within the system – a condition that is not always fulfilled during the melting phase. Therefore, this reinitialization strategy is only applied if no interruptions of the arcs occur during the entire simulation period.

3.2. Equivalent Circuit Parameter Selection

The grid in this study was operated at a fundamental frequency of 50 Hz and the short-circuit power at the PCC rated at 3000 MVA. However, it is important to note that this value can drop significantly under worst-case conditions. In accordance with the observations of Ciotti et al. [

10], the reactance/resistance ratio of the grid, expressed as

, was set to a value of 8. Similarly, the reactance/resistance ratio for the step-down transformer

was set to 10. The reactance/resistance ratio and the percentage impedance of the arc furnace transformer depend on the transformer tap position, which changes during the heat. The values for the short-circuit resistance

and reactance

were derived from the transformer data sheet. However, no values were given for individual phases in this data sheet, so uniform values were assumed for all phases for the purposes of this study.

In the field of arc voltage and arc length modeling, the determination of the parameters is crucial, as described in the Equation (

28). The anode and cathode voltage drop

and the electric field intensity

E are of particular interest. Recent studies have suggested different ranges for these parameters. Pauna et al. [

12] suggest

values between 10 V and 80 V and

E values between 500 V

m and 3000 V

m, indicating a large variability in arcing conditions. In contrast, Nikolaev et al. [

42] recommend a narrower range for

(20 V to 40 V) and

E (600 V

m to 1000 V

m). Garcia-Segura et al. [

11] provide more specific values and argue for

at 40 V and

E at 1150 V

m. In the absence of precise measurements of arc length in our operational context, we took an empirical approach to parameter selection and adjusted our values to these recommendations. We set

to 40 V in agreement with Garcia-Segura et al. [

11] and chose

E at 1000 V

m. For the power loss factor in Equation (

22), determining the length of the arc, temperature and conductivity is challenging due to measurement issues. We estimate the arc length using the Equation (

28) and the effective arc voltage. According to Pauna et al. [

12], the arc conductivity

is influenced by both the temperature and the length. Following the suggestion of Logar et al. [

45] suggestion, we set the specific conductivity to a constant value of

S

m. While Logar suggests an arc temperature of 4500 K, our analysis has shown that reducing this parameter to 3000 K minimizes the mean error in the fitness function (

33). The resistance

that defines the threshold at which the arc extinguishes is set to the value of 250 m

.

In the process of optimizing parameters using particle swarm optimization (PSO), it is imperative to initially establish the boundaries within which these parameters will vary. Lee et al. [

24] postulated a theoretical range for

ranging from 0.5 to 1. In addition, they hypothesized that

can exceed this range based on empirical observations. To capture a broader range of possible values and increase the robustness of our search, we delimited the range for

as

and

. In addition, the arc time constant, a critical parameter in our model, was determined by synthesizing findings from previous studies and empirical experiments. Nikolaev et al. [

42] determined that the arc time constant is between 0.2 ms and 5 ms. At the same time, the analysis of the data of Golestani et al. [

19] showed that their arc time constant was between 0.4 ms and 2 ms. Considering these results, we set the bounds for the arc time constant in our study as

ms and

ms. This range is intended to reflect the different results observed in previous research while allowing a comprehensive exploration of the possible values in the context of PSO framework.

3.3. Hyperparameter Selection

In formulating our optimization strategy, particular emphasis was placed on balancing the importance of voltage and current within the objective function, as shown in Equation (

33). This balance is achieved by including the parameter

. We have assigned a value of 0.5 to

to ensure equal weighting of voltage and current in the optimization process. Furthermore, the fitness functions for voltage and current defined in the Equations (

34) and (

35) are based on Fourier series analysis. This analytical approach requires the specification of the number of harmonics

. After careful consideration and experimental verification, we have decided to set

to 10. This decision is supported by the realization that the inclusion of a much higher number of harmonics does not significantly increase the accuracy of the analysis. For the optimization procedure, the number of particles

was set to 15 and the maximum number of PSO iterations

was set to 200.

3.4. Parameters Estimation Algorithm

Algorithm describes the procedure for optimizing the parameters of the Cassie-Mayr model in a three-phase AC system. This algorithm uses particle swarm optimization (PSO) to effectively tune the model parameters to ensure an accurate representation of the arc phenomena in EAFs. This algorithm is designed to systematically process the available EAF data and adjust and refine the parameters of the Cassie-Mayr model for each line. The process is iterative and utilizes the strengths of PSO to converge to the most accurate parameter set that reflects the complex dynamics of the EAF system. The fitness of each particle in the swarm is evaluated using predefined criteria, which facilitates the identification of the optimal parameter set for the model.

|

Algorithm 1: Three-phase Cassie-Mayr model optimization |

- 1:

Define PSO hyperparameters: , , ,

- 2:

Define power supply parameters - 3:

Define arc parameters: , , E, , , - 4:

Define the range of arc parameters: ,

- 5:

repeat Through all the data - 6:

Acquire one period of measurements: ,

- 7:

Define ULV based on T and calculate,

- 8:

Based on estimate: ,

- 9:

Initialize: x(0), φ - 10:

repeat Through all PSO iterations - 11:

Calculate arc parameters αl, τl according to PSO rules - 12:

Simulate one period of operation - 13:

Calculate fitness for all particles - 14:

until Niter ≤

- 15:

Save best paarticle: αl, τl

- 16:

until No data is left |

5. Results

This section presents the results obtained with the proposed procedure to optimize the parameters of the Cassie-Mayr model followed by the AQI. This includes data collected during a single heat spanning from the last bucket loading through the refining stage to the final heat tapping. The voltage and current signals were sampled at a frequency of 5 kHz, resulting in a dataset covering slightly less than 1000 seconds of EAF operation. The optimization algorithm described in Algorithm uses one period of data to determine the arc parameters. It was determined that not every period should be used in this procedure, and a sampling frequency of 8 Hz was chosen as appropriate to capture the rapidly changing arc parameters while ensuring detailed and granular analysis.

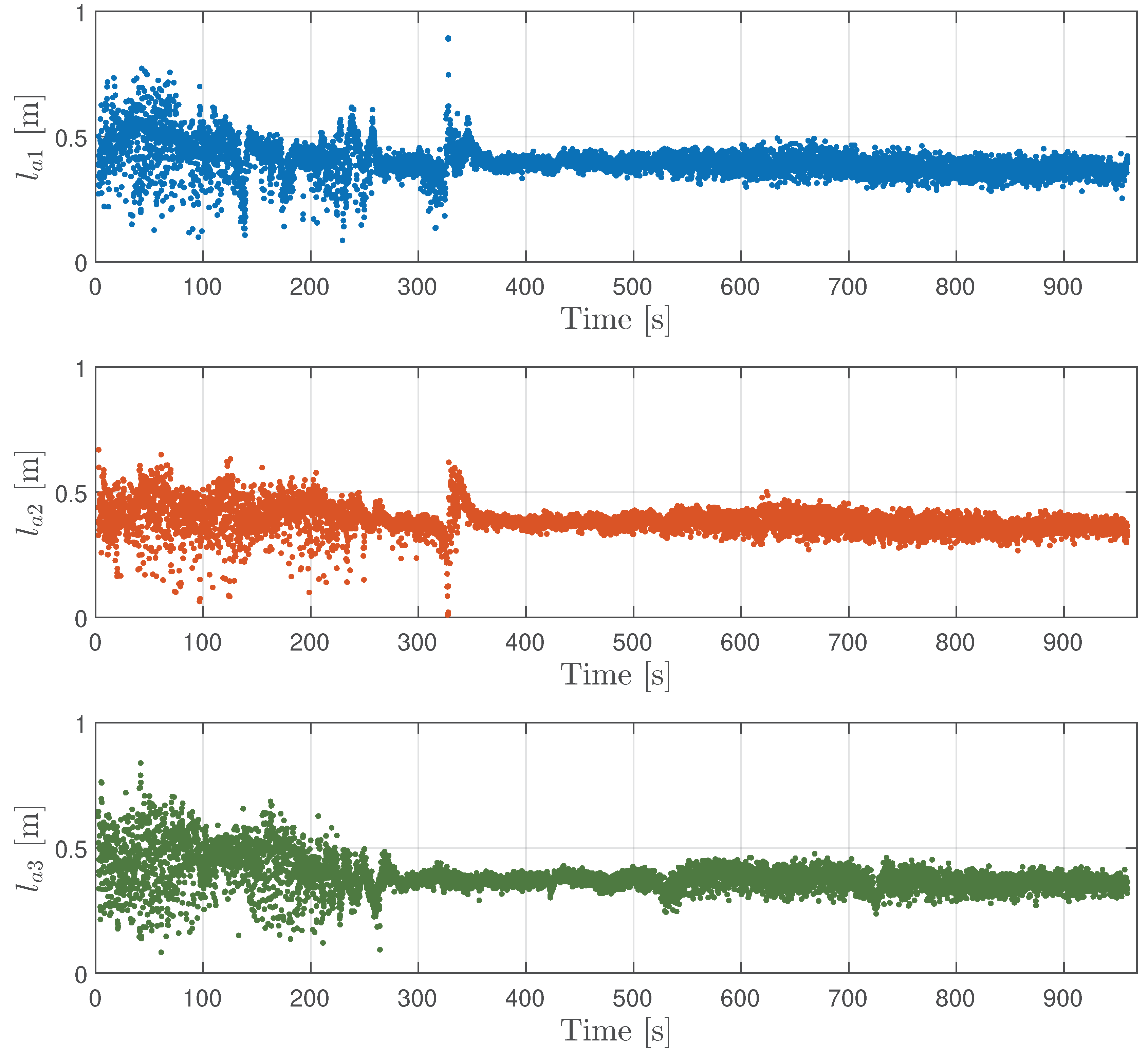

For the complete dataset, the estimated arc length values for all three lines were calculated using the Equation (

28), as shown in

Figure 3. The estimate of the arc length is based on the effective arc voltage observed over one period of the signal. It can be seen from the

Figure 3 that the arc length exhibits greater variability during the initial melting stage than in the later refining stage.

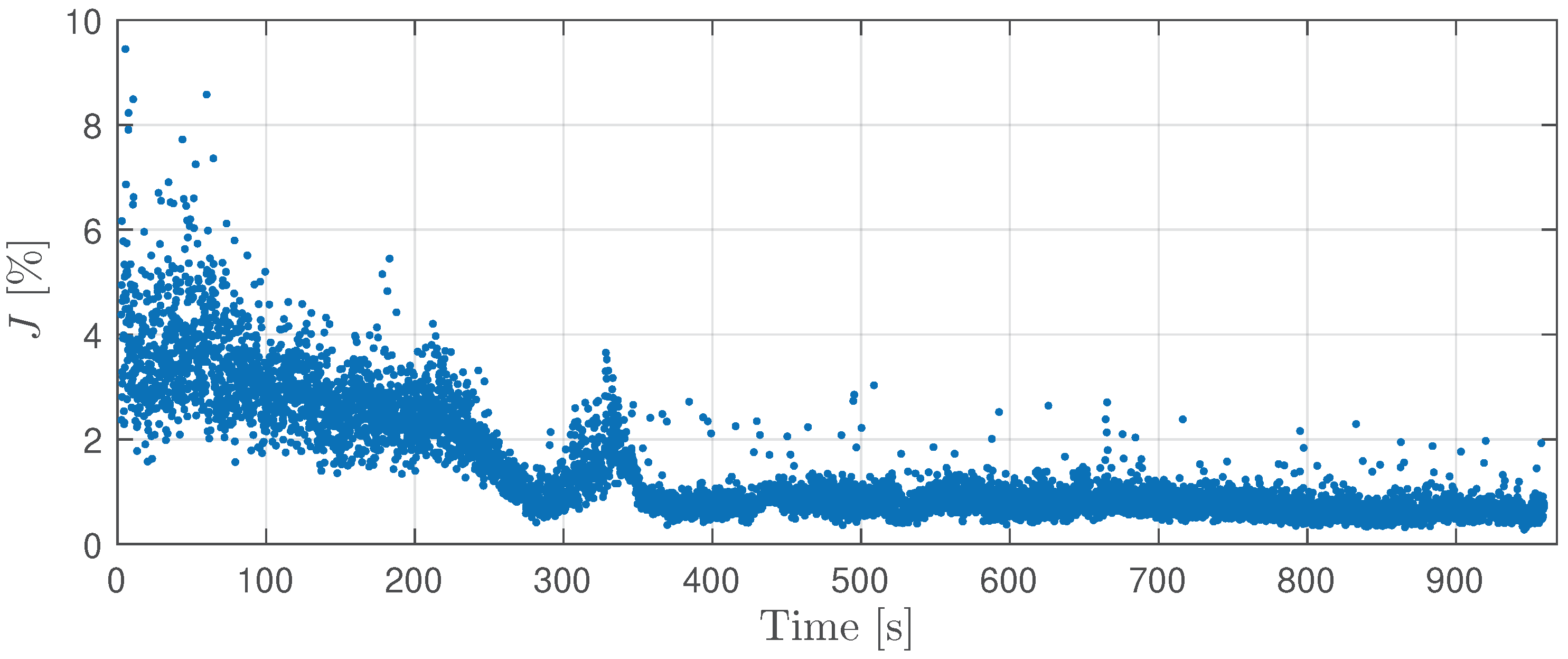

The optimization described in Algorithm was used for estimating the parameters of the Cassie-Mayr model in a three-phase AC system over the entire dataset. The performance of this algorithm is quantitatively evaluated using the values of the fitness function shown in

Figure 4. Analysis of

Figure 4 shows that the fitness function has higher values during the melting stage, indicating less stable arc conditions. When the process moves to the refinig stage, a clear stabilization of the arc can be observed, which is reflected in lower values of the fitness function. In

Table 1, the mean values of the fitness function in the different operating stages are explained in more detail: "All" (for the entire dataset), "Melting" (specifically for the melting phase) and "Refining" (for the refining phase). This table also shows the mean values of the voltage and current components of the fitness function. It is noteworthy that the mean current fitness function

has consistently lower values than the mean voltage fitness function

across all stages.

Below we will examine the graphical representations of the results in two specific cases: during the melting stage and the refining stage. But first, it is important to note that the signals are normalized with respect to the peak values of line-to-ground voltage

and line current

, which are calculated as follows:

where the square root of two is used to obtain the peak value from the RMS value.

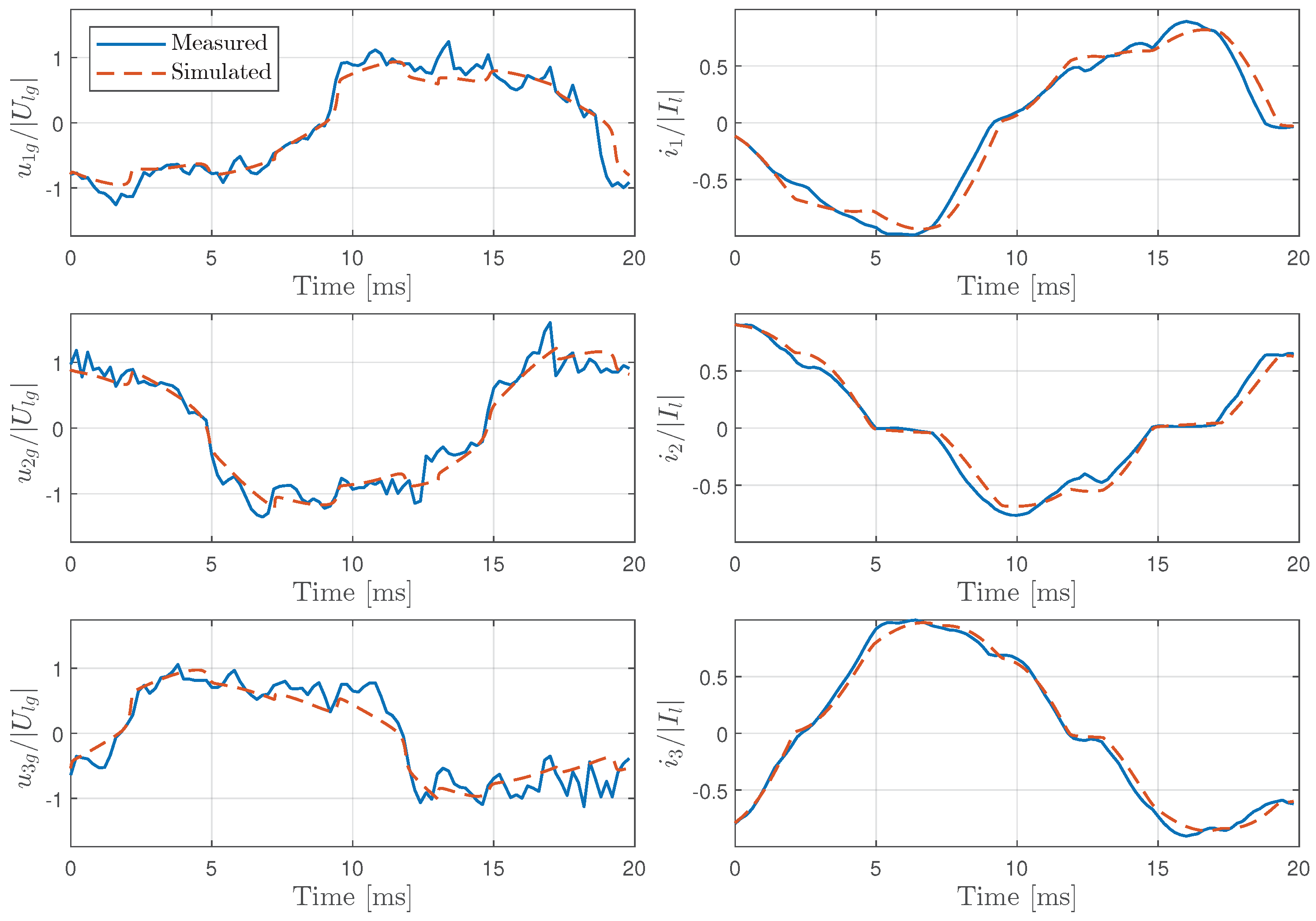

Figure 5 shows a detailed analysis of the line-to-ground voltages and line currents during a specific interval of the melting stage, comparing measured and simulated signals. It is noteworthy that four arc interruptions occur during this period — two in the second line and one each in the first and third lines. This observation highlights the inherent instability of the arc during the melting stage, a critical aspect of the EAF process. The model successfully captures the dynamics of these arc interruptions, proving its effectiveness in replicating arc behavior.

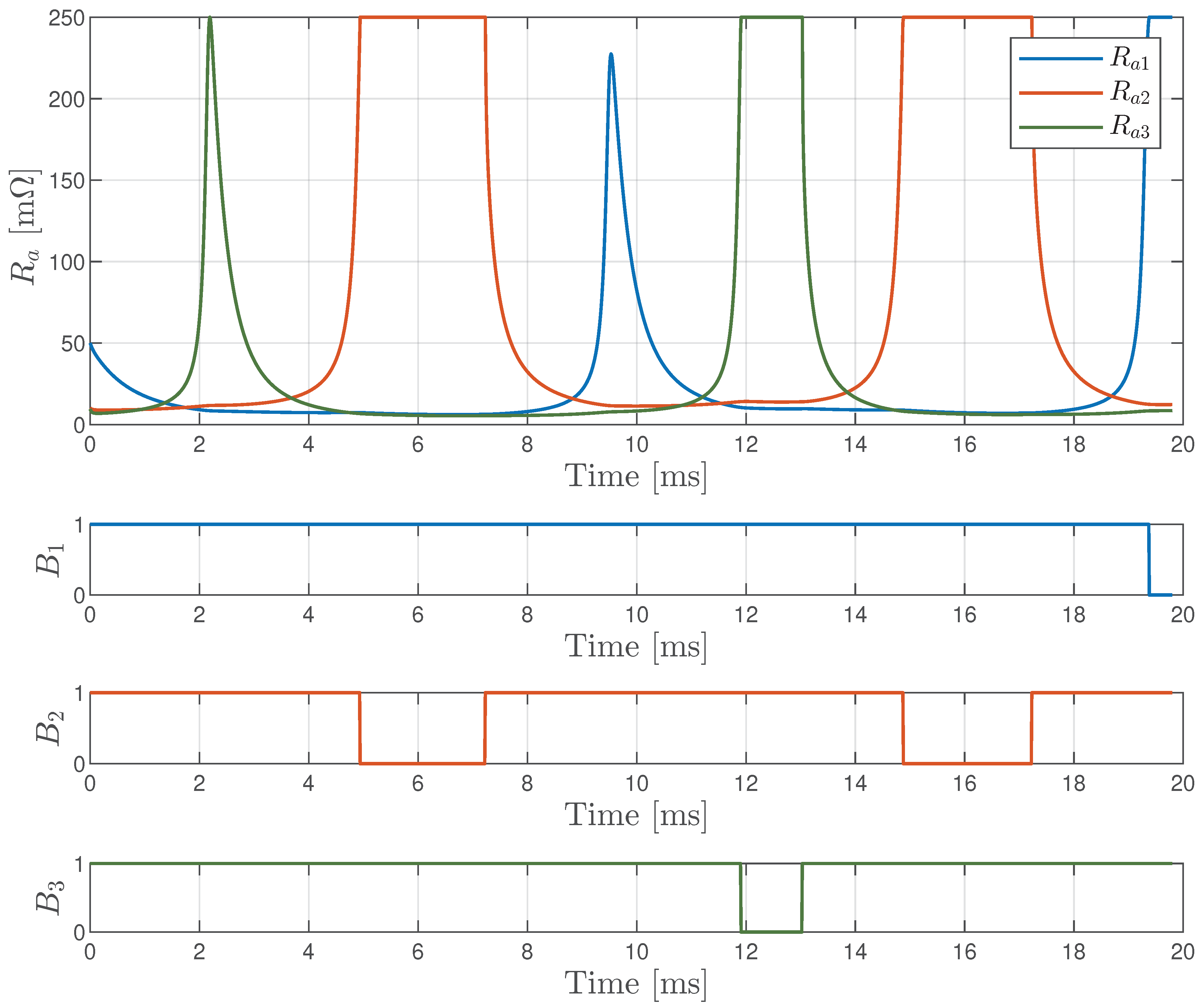

Figure 6 shows the calculated arc resistance for all three lines based on the Cassie-Mayr model, which corresponds to the same time period shown in

Figure 5. In addition, the operating state of the arc is represented by a binary variable

that distinguishes between active and extinguished states. This figure clearly illustrates the four cases of arc interruptions mentioned above. In particular, the second line shows the longest interruptions, which exceed a duration of 2 ms. Interestingly, the initial peak of arc resistance in the third line approaches the threshold value

, but it remained slightly below this limit.

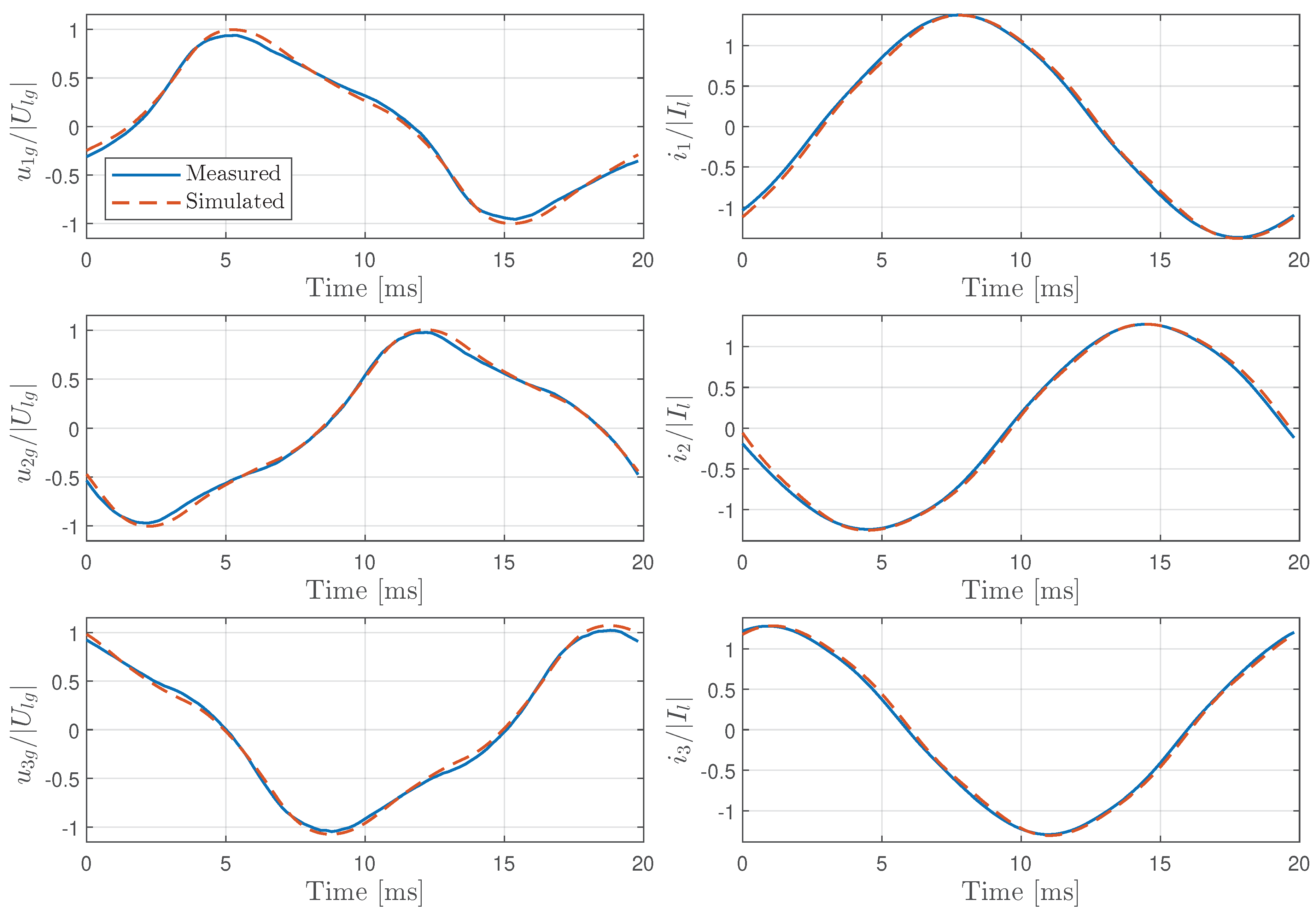

Figure 7 shows a descriptive example of a particular interval during the refining stage of an EAF, showing both the observed and simulated line-to-ground voltages and line currents. A notable aspect of this figure is the high degree of correlation between the simulated signals and the actual measured data, indicating the accuracy of the model in capturing the electrical behavior during the refining process.

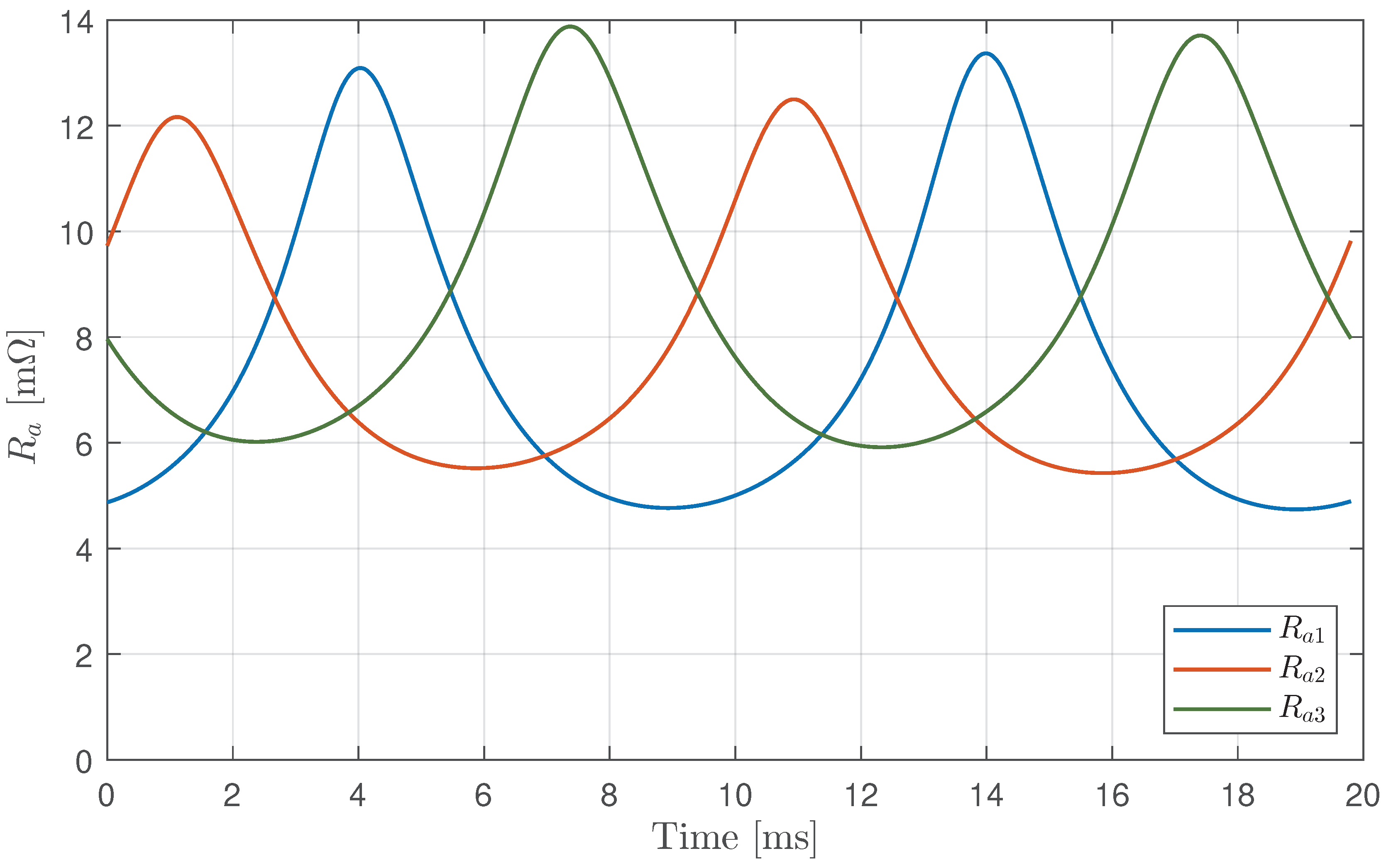

In addition,

Figure 8 shows the arc resistances for all three lines during the refining stage. These resistances were calculated using the Cassie-Mayr model, which is based on data from the same time period as

Figure 7. In comparison to the resistance profiles observed during the melting stage (

Figure 6), a strong contrast is evident. During the refining stage, the arc resistances are significantly lower and show a periodic pattern, indicating stable arc operation with no signs of instability.

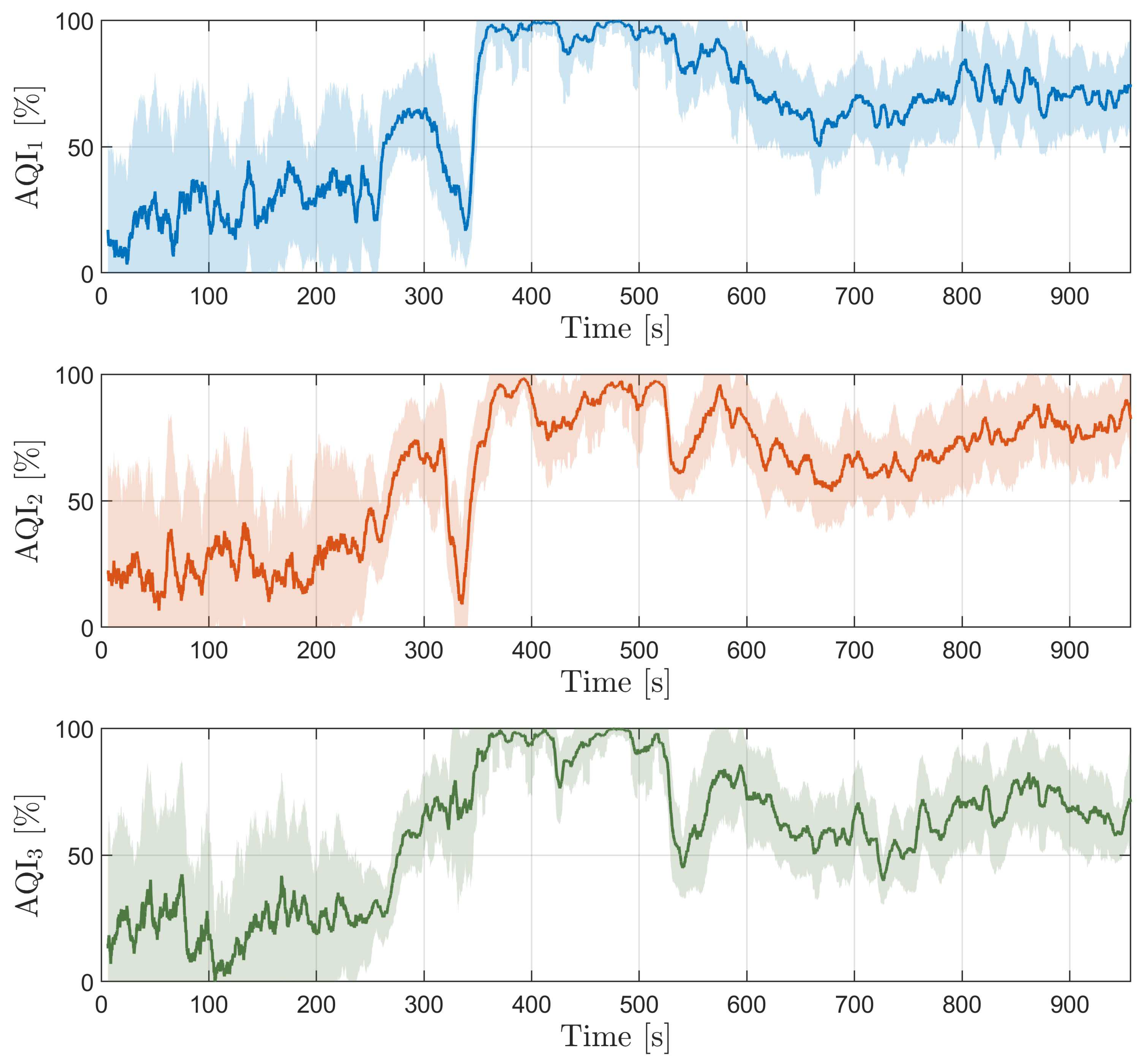

A graphical analysis of the AQI across all three lines of an EAF, from the final part of the melting stage to the refining stage is shown in

Figure 9. The AQI provides a quantitative assessment of arc performance and stability, with higher values indicating more favorable arc conditions. To improve the interpretability of the data and reduce the impact of transient fluctuations, a smoothing process was applied using a moving average filter and a standard deviation for the moving average. The filtering is applied over the past 50 samples, effectively tracing the underlying AQI trends and clarifying the development curve over time. Through a careful Cassi-Mayr parameter

analysis, we set the optimal value for the arc parameter

. In order for AQI to provide a qualitative assessment of the arc quality, we set the value between 0 and 1, resulting in the following parameters:

and

.

Figure 9 serves as an important analytical tool for evaluating EAF performance and provides important insights into the melting and refining processes. The visual representation of the AQI enables the identification of operating patterns and areas for improvement. The initial low AQI values reflect the instability of the arc during the melting stage, which is confirmed by the variable arc length estimates in

Figure 3. A significant dip in AQI around 350 s in the first and second lines, which is not reflected in the third line, shows the ability of the index to distinguish between different lines. When the process enters the refining phase around 400 s, a significant improvement in arc quality is observed. AQI values close to 100 % denote that the arcs are operating in stable conditions and are completely covered by the slag. A slight decreasing trend in AQI values beyond 500 s is attributed to insufficient arc coverage by the slag.