Submitted:

29 January 2024

Posted:

29 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Stimuli-responsive principles of soft actuators

Fluidic stimuli

Electrical stimuli

Thermal stimuli

Magnetic stimuli

Light stimuli

Chemical stimuli

3. Stimuli-responsive materials for soft actuators

Electroactive polymers

| Materials | Stimulus sources | Response time | Mechanical properties | Crosslinking methods | Durability | Refs |

| Ecoflex 00-30 | Fluidic stimuli | ~50 ms | E=~0.1MPa | Thermal curing | 1×105 cycles | [30] |

| IPMCs | Electrical stimuli | ~20-90 s | NA | Ionic crosslinking | NA | [104] |

| IGMN | Electrical stimuli | ~50 s | E=~0.35MPa | Ionic crosslinking | 7.6×104 cycles | [105] |

| PEDGA, PEDOT: PSS | Electrical stimuli | ~0.8 s | E=~11-15MPa | Ionic crosslinking | 5×103 cycles | [107] |

| PDMS | Electrical stimuli | ~1.67 ms | E=~4 MPa | Thermal curing | NA | [35] |

| PDMS | Electrical stimuli | 5 ms | NA | Thermal curing | 5×104 cycles | [113] |

| FSNPs, Ecoflex 00-30 | Electrical stimuli | 1.43 ms | G= 27-979 kPa | Thermal curing | 2.6×105 cycles | [116] |

| Fe3O4 nanoparticles, Fe-alginate, PAAm | Magnetic stimuli | NA | τ= 200–1000 kPa | Ionic crosslinking | NA | [120] |

| Carbonyl iron microparticles, TPU | Magnetic stimuli | 25 ms | NA | Thermal curing | NA | [121] |

| NdFeB microparticles, Ecoflex 00-10 | Magnetic stimuli | NA | E=~78.6 ± 4.8kPa | Thermal curing | NA | [67] |

| Iron microparticles, PDMS | Magnetic stimuli | 35.8 ms | E=~2 MPa | Thermal curing | 5×103 cycles | [68] |

| NdFeB, FSNPs, Ecoflex 00-30 Part B, SE 1700 | Magnetic stimuli | ~0.1 s | G=330 kPa | Thermal curing | NA | [130] |

| PEG1000, HDI, HABI | Light stimuli | ~35 s | τ=2.88 MPa | Light-crosslinking | 500 cycles | [142] |

| BN, AlN, Si3N4, NIPAM | Light stimuli | ~30 s | E=9.71 ± 0.06 kPa | Photopolymerization | > 10 cycles | [144] |

| PNIPAAM, AuNPs, rGO | Light stimuli | < 1 s | τ= 8–18 kPa | Photopolymerization | NA | [148] |

| RM 257, HDT | Light stimuli | < 0.2 s | τ= 3–4 MPa | Light-crosslinking | 1×106 cycles | [162] |

| PLCMs, MDI, HEMA | Light stimuli | 4-8 s | E=~11-20 MPa | Light-crosslinking | NA | [165] |

| Ni, Cr, SMP | Electrothermal stimuli | 20 s | E=~3.33-125.65 MPa | NA | NA | [166] |

| Graphene oxide, SU-8 | Humidity stimuli | ~22-26 s | τ=~30-90 MPa | Photopolymerization | > 500 cycles | [177] |

| PVDF, PPy | Solvent stimuli | 3.1-9.2 s | E=~2.53 GPa | Thermal curing | NA | [180] |

| PAAc | pH stimuli | ~120 s | E=~300 MPa | Photopolymerization | > 10 cycles | [184] |

Magnetic soft composites

Hydrogels and Liquid crystal elastomers

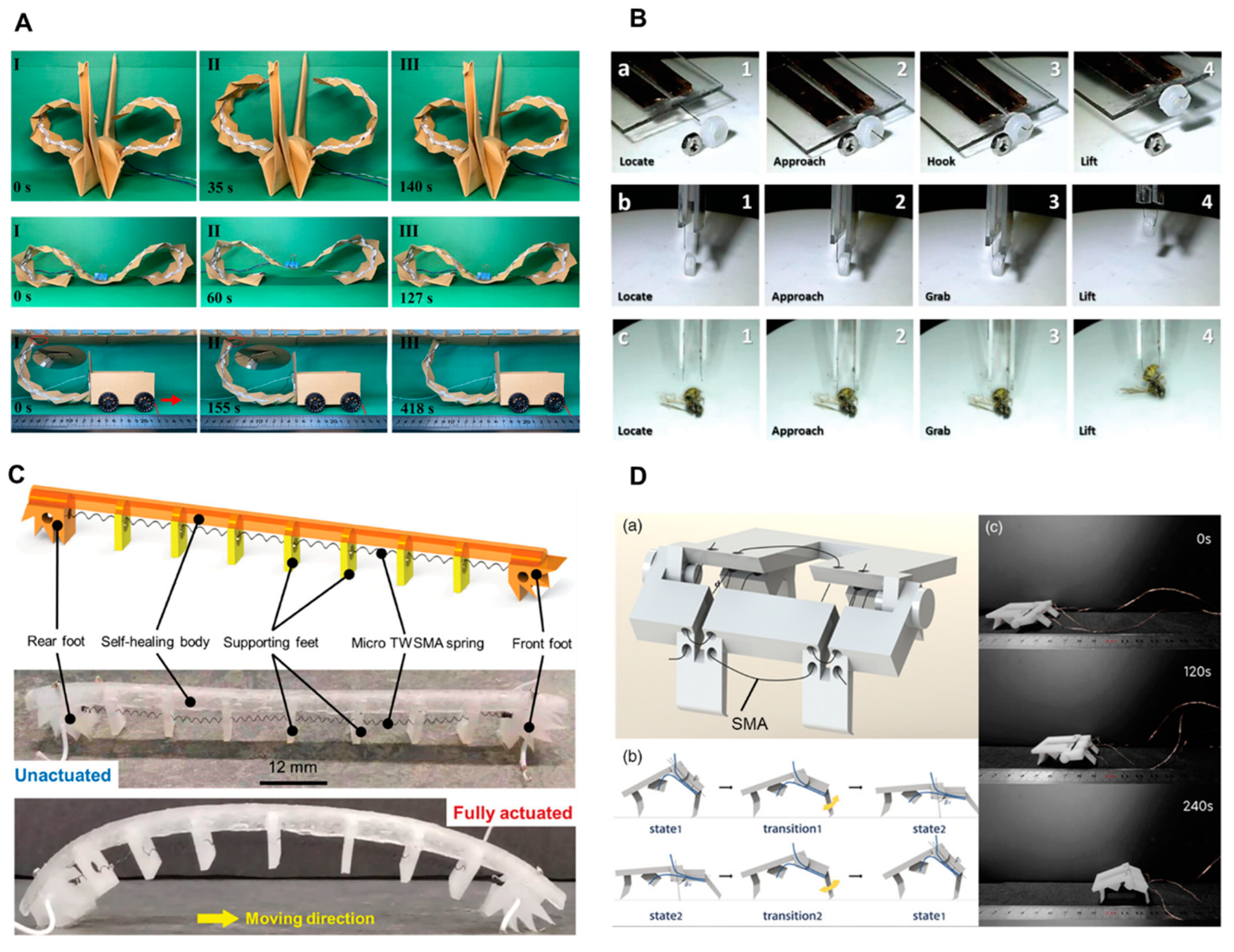

Shape memory alloys

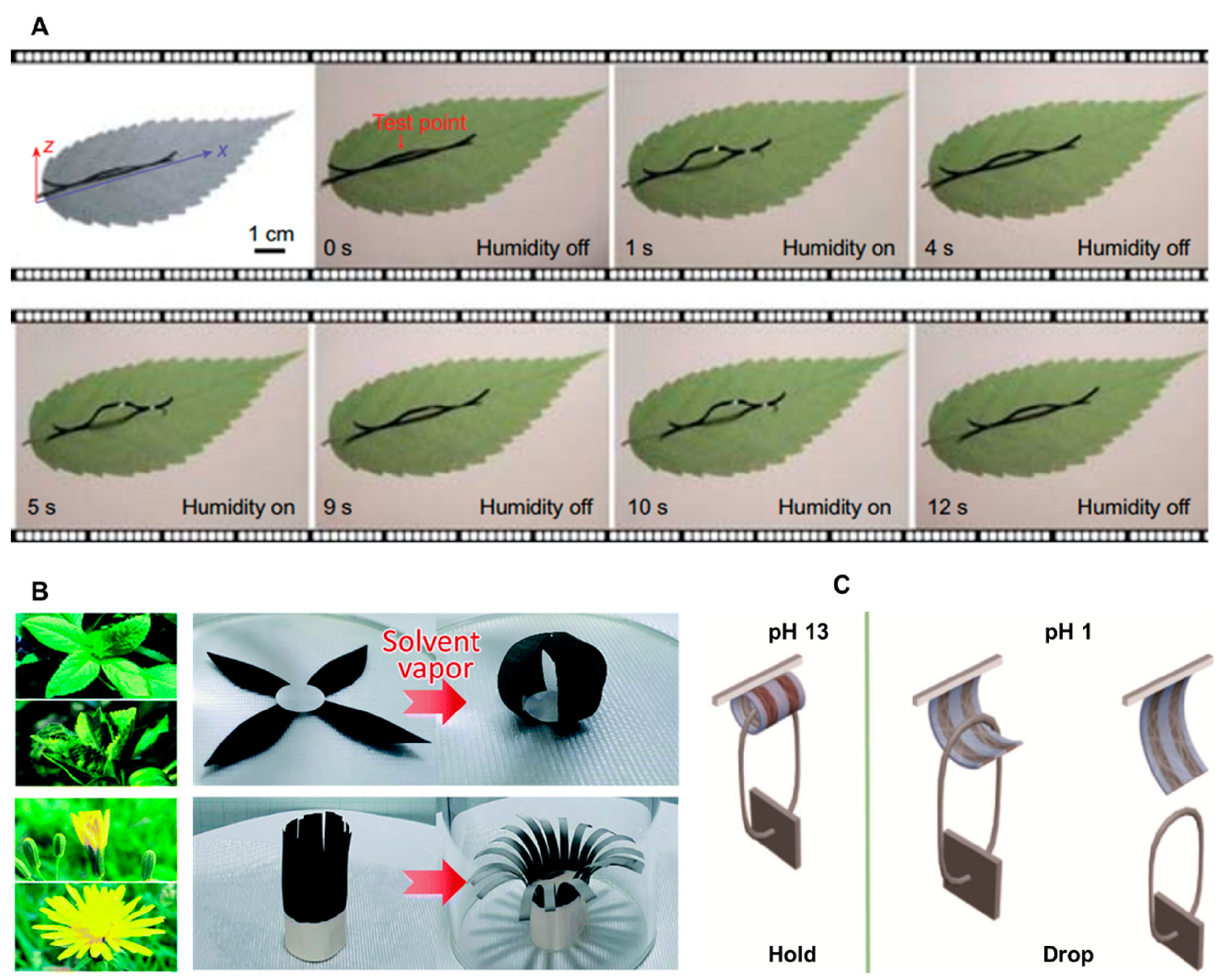

Chemical-responsive materials

4. Conclusions and outlook

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Sitti, M. Miniature soft robots — road to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetti, M.; Laschi, C.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P. Biomedical applications of soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, T.J.; Pikul, J.; Shepherd, R.F. 3D printing of soft robotic systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschi, C.; Mazzolai, B.; Cianchetti, M. Soft robotics: Technologies and systems pushing the boundaries of robot abilities. Sci. Robot. 2016, 1, eaah3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, J.; Lu, B.; Gu, G. 3D-printed PEDOT:PSS for soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pal, A.; Aghakhani, A.; Pena-Francesch, A.; Sitti, M. Soft actuators for real-world applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 7, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintake, J.; Cacucciolo, V.; Floreano, D.; Shea, H., Soft Robotic Grippers. Adv Mater 2018, 30 (29). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ng, C.J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Panjwani, S.; Kowsari, K.; Yang, H.Y.; Ge, Q. Miniature Pneumatic Actuators for Soft Robots by High-Resolution Multimaterial 3D Printing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, K.; Wang, S.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. A Soft and Bistable Gripper with Adjustable Energy Barrier for Fast Capture in Space. Soft Robot. 2023, 10, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirfakhrai, T.; Madden, J.D.W.; Baughman, R.H. Polymer artificial muscles. Mater. Today 2007, 10, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, C.; Goldberg, N.N.; Deheyn, D.D.; Cai, S.; Tolley, M.T. Translucent soft robots driven by frameless fluid electrode dielectric elastomer actuators. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, L.; Petersen, K.H.; Lum, G.Z.; Sitti, M. Soft Actuators for Small-Scale Robotics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Yang, D.; Ren, L.; Wei, G.; Gu, G. X-crossing pneumatic artificial muscles. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yuan, F.; Liu, J.; Tian, L.; Chen, B.; Fu, Z.; Mao, S.; Jin, T.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; et al. Octopus-inspired sensorized soft arm for environmental interaction. Sci. Robot. 2023, 8, eadh7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerbeek, I.M.; De Sa, C.M.; Shepherd, R.F. Soft optoelectronic sensory foams with proprioception. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Li, S.; Barreiros, J.; Tu, Y.; Pollock, C.R.; Shepherd, R.F. Stretchable distributed fiber-optic sensors. Science 2020, 370, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, B.; Shah, D.; Li, J. X.; Thuruthel, T. G.; Park, Y. L.; Iida, F.; Bao, Z. A.; Kramer-Bottiglio, R.; Tolley, M. T., Electronic skins and machine learning for intelligent soft robots. Sci Robot 2020, 5 (41). [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Deswal, S.; Christou, A.; Sandamirskaya, Y.; Kaboli, M.; Dahiya, R. Neuro-inspired electronic skin for robots. Sci. Robot. 2022, 7, eabl7344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justus, K.B.; Hellebrekers, T.; Lewis, D.D.; Wood, A.; Ingham, C.; Majidi, C.; LeDuc, P.R.; Tan, C. A biosensing soft robot: Autonomous parsing of chemical signals through integrated organic and inorganic interfaces. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Parada, G.A.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Gilbert, H.; Sitti, M. Magnetically Actuated Soft Capsule Endoscope for Fine-Needle Biopsy. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Chen, L.; Aras, K.; Liang, C.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, K.; Faye, N.R.; Sun, B.; Kim, J.-H.; et al. Catheter-integrated soft multilayer electronic arrays for multiplexed sensing and actuation during cardiac surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, G.; Zhang, N.; Xu, H.; Lin, S.; Yu, Y.; Chai, G.; Ge, L.; Yang, H.; Shao, Q.; Sheng, X.; et al. A soft neuroprosthetic hand providing simultaneous myoelectric control and tactile feedback. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 7, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Restrepo, V.; Goswami, D.; Martinez, R.V. Exploiting Mechanical Instabilities in Soft Robotics: Control, Sensing, and Actuation. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.Y.; Chirarattananon, P.; Fuller, S.B.; Wood, R.J. Controlled Flight of a Biologically Inspired, Insect-Scale Robot. Science 2013, 340, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Hu, W.; Dong, X.; Sitti, M. Multi-functional soft-bodied jellyfish-like swimming. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitesides, G.M. Soft Robotics. Angew Chem Int Edit 2018, 57, 4258–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Volder, M.; Reynaerts, D., Pneumatic and hydraulic microactuators: a review. J Micromech Microeng 2010, 20 (4). [CrossRef]

- Mosadegh, B.; Polygerinos, P.; Keplinger, C.; Wennstedt, S.; Shepherd, R.; Gupta, U.; Shim, J.; Bertoldi, K.; Walsh, C.J.; Whitesides, G.M. Pneumatic Networks for Soft Robotics that Actuate Rapidly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.F.; Ilievski, F.; Choi, W.; Morin, S.A.; Stokes, A.A.; Mazzeo, A. D.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Whitesides, G.M. Multigait soft robot. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 20400–20403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, G.; Zou, J.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, X. Soft wall-climbing robots. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Qin, L.; Liu, J.; Ren, Q.; Foo, C.C.; Wang, H.; Lee, H.P.; Zhu, J. Untethered soft robot capable of stable locomotion using soft electrostatic actuators. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2018, 21, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graule, M.A.; Chirarattananon, P.; Fuller, S.B.; Jafferis, N.T.; Ma, K.Y.; Spenko, M.; Kornbluh, R.; Wood, R.J. Perching and takeoff of a robotic insect on overhangs using switchable electrostatic adhesion. Science 2016, 352, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Liu, X.; Cacucciolo, V.; Imboden, M.; Civet, Y.; El Haitami, A.; Cantin, S.; Perriard, Y.; Shea, H. An autonomous untethered fast soft robotic insect driven by low-voltage dielectric elastomer actuators. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, D. SHAPE MEMORY ALLOYS Towards practical actuators. Nat Mater 2015, 14, 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, H.; Wang, W.; Han, M.-W.; Kim, T.J.; Ahn, S.-H. An Overview of Shape Memory Alloy-Coupled Actuators and Robots. Soft Robot. 2017, 4, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, S.; Onal, C.D.; Cho, K.-J.; Wood, R.J.; Rus, D.; Kim, S. Meshworm: A Peristaltic Soft Robot With Antagonistic Nickel Titanium Coil Actuators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2012, 18, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Shea, H. Reconfigurable and Latchable Shape-Morphing Dielectric Elastomers Based on Local Stiffness Modulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.D.; Li, N.; de Andrade, M.J.; Fang, S.; Oh, J.; Spinks, G.M.; Kozlov, M.E.; Haines, C.S.; Suh, D.; Foroughi, J.; et al. Electrically, Chemically, and Photonically Powered Torsional and Tensile Actuation of Hybrid Carbon Nanotube Yarn Muscles. Science 2012, 338, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; de Andrade, M.J.; Fang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, E.; Li, N.; Kim, S.H.; Wang, H.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Sheath-run artificial muscles. Science 2019, 365, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanik, M.; Orguc, S.; Varnavides, G.; Kim, J.; Benavides, T.; Gonzalez, D.; Akintilo, T.; Tasan, C.C.; Chandrakasan, A.P.; Fink, Y.; et al. Strain-programmable fiber-based artificial muscle. Science 2019, 365, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Neri, W.; Zakri, C.; Merzeau, P.; Kratz, K.; Lendlein, A.; Poulin, P. Shape memory nanocomposite fibers for untethered high-energy microengines. Science 2019, 365, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, C.S.; Lima, M.D.; Li, N.; Spinks, G.M.; Foroughi, J.; Madden, J.D.W.; Kim, S.H.; Fang, S.; de Andrade, M.J.; Göktepe, F.; et al. Artificial Muscles from Fishing Line and Sewing Thread. Science 2014, 343, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Sun, D.; Lin, L. Soft magnetic composites for highly deformable actuators by four-dimensional electrohydrodynamic printing. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2021, 231, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Hu, R.; Xie, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Han, X.; Cao, Q.; Li, L. Reconfigurable magnetic soft robots with multimodal locomotion. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D. Design, fabrication and application of magnetically actuated micro/nanorobots: a review. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 152001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, D.; Zheng, J.; Wu, D. A magnetic soft robot with multimodal sensing capability by multimaterial direct ink writing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verra, M.; Firrincieli, A.; Chiurazzi, M.; Mariani, A.; Secco, G.L.; Forcignanò, E.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P.; Ciuti, G.; et al. Robotic-Assisted Colonoscopy Platform with a Magnetically-Actuated Soft-Tethered Capsule. Cancers 2020, 12, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Sitti, M. Design and Rolling Locomotion of a Magnetically Actuated Soft Capsule Endoscope. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2011, 28, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Tan, D.; Li, Q.; Song, B.; Wu, Z.-S.; del Campo, A.; Kappl, M.; Wang, Z.; Gorb, S.N.; et al. Bioinspired footed soft robot with unidirectional all-terrain mobility. Mater. Today 2020, 35, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, B.; Milana, E.; Baeyens, A.; Broeders, E.; Christiaens, J.; Collin, K.; Reynaerts, D.; De Volder, M. Hardware Sequencing of Inflatable Nonlinear Actuators for Autonomous Soft Robots. Adv. Mater. 2018, 31, e1804598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Vogt, D.M.; Rus, D.; Wood, R.J. Fluid-driven origami-inspired artificial muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 13132–13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siéfert, E.; Reyssat, E.; Bico, J.; Roman, B. Bio-inspired pneumatic shape-morphing elastomers. Nat. Mater. 2018, 18, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, R.; Alici, G.; Li, W. A Soft Mechatronic Microstage Mechanism Based on Electroactive Polymer Actuators. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2015, 21, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiesmaili, E.; Clarke, D.R. Reconfigurable shape-morphing dielectric elastomers using spatially varying electric fields. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chortos, A.; Hajiesmaili, E.; Morales, J.; Clarke, D.R.; Lewis, J.A. 3D Printing of Interdigitated Dielectric Elastomer Actuators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelrine, R.; Kornbluh, R.; Pei, Q.; Joseph, J. High-Speed Electrically Actuated Elastomers with Strain Greater Than 100%. Science 2000, 287, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duduta, M.; Hajiesmaili, E.; Zhao, H.; Wood, R.J.; Clarke, D.R. Realizing the potential of dielectric elastomer artificial muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 2476–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotikian, A.; Truby, R. L.; Boley, J. W.; White, T. J.; Lewis, J. A., 3D Printing of Liquid Crystal Elastomeric Actuators with Spatially Programed Nematic Order. Adv Mater 2018, 30 (10). [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Song, H.; Jiang, R.; Song, J.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Programming a crystalline shape memory polymer network with thermo- and photo-reversible bonds toward a single-component soft robot. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaao3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Bilal, O.R.; Shea, K.; Daraio, C. Harnessing bistability for directional propulsion of soft, untethered robots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 5698–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotikian, A.; McMahan, C.; Davidson, E.C.; Muhammad, J.M.; Weeks, R.D.; Daraio, C.; Lewis, J.A. Untethered soft robotic matter with passive control of shape morphing and propulsion. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Mu, X.; Ling, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Guo, C.; Watson, M.C.; Yu, Y.; et al. Stimuli-responsive composite biopolymer actuators with selective spatial deformation behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 14602–14608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Bhattacharya, K. Photomechanical coupling in photoactive nematic elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2020, 144, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Zhao, X. Magnetic Soft Materials and Robots. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5317–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Francesch, A.; Zhang, Z.; Marks, L.; Cabanach, P.; Richardson, K.; Sheehan, D.; McCracken, J.; Shahsavan, H.; Sitti, M. Macromolecular radical networks for organic soft magnets. Matter 2024, 7, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Fukuda, T.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y. A bioinspired multilegged soft millirobot that functions in both dry and wet conditions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Lum, G.Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, R.; Ren, Z.; Onck, P.R.; Sitti, M. Bioinspired cilia arrays with programmable nonreciprocal motion and metachronal coordination. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, G.Z.; Ye, Z.; Dong, X.; Marvi, H.; Erin, O.; Hu, W.; Sitti, M. Shape-programmable magnetic soft matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E6007–E6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H. R.; Boehler, Q.; Cui, H. Y.; Secchi, E.; Savorana, G.; De Marco, C.; Gervasoni, S.; Peyron, Q.; Huang, T. Y.; Pane, S.; Hirt, A. M.; Ahmed, D.; Nelson, B. J., Magnetic cilia carpets with programmable metachronal waves. Nat Commun 2020, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.J.; Kaliakatsos, I.K.; Abbott, J.J. Microrobots for Minimally Invasive Medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 12, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-W.; Uslu, F.E.; Katsamba, P.; Lauga, E.; Sakar, M.S.; Nelson, B.J. Adaptive locomotion of artificial microswimmers. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jang, Y.; Choe, J.K.; Lee, S.; Song, H.; Lee, J.P.; Lone, N.; Kim, J. 3D-printed programmable tensegrity for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Yu, D.; Xia, Z.; Wan, H.; Liu, C.; Yin, T.; He, Z. Ferromagnetic Liquid Metal Putty-Like Material with Transformed Shape and Reconfigurable Polarity. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2000827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitti, M.; Wiersma, D.S. Pros and cons: magnetic versus optical microrobots. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Humidity- and photo-induced mechanical actuation of cross-linked liquid crystal polymers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancia, F.; Ryabchun, A.; Nguindjel, A.-D.; Kwangmettatam, S.; Katsonis, N. Mechanical adaptability of artificial muscles from nanoscale molecular action. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahsavan, H.; Aghakhani, A.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Y.; Davidson, Z.S.; Priimagi, A.; Sitti, M. Bioinspired underwater locomotion of light-driven liquid crystal gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 5125–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuenstler, A.S.; Kim, H.; Hayward, R.C. Liquid Crystal Elastomer Waveguide Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Leow, W.R.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; He, K.; Qi, D.; Wan, C.; Chen, X. 3D Printed Photoresponsive Devices Based on Shape Memory Composites. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.A.-C.; Gillen, J.H.; Mishra, S.R.; Evans, B.A.; Tracy, J.B. Photothermally and magnetically controlled reconfiguration of polymer composites for soft robotics. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wei, A.; Xiao, P.; Liang, Y.; Lu, W.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Yang, G.; Yao, H.; et al. Asymmetric elastoplasticity of stacked graphene assembly actualizes programmable untethered soft robotics. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, J.-K.; Aurelio, D.; Li, W.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.H.; Liscidini, M.; Rogers, J.A.; Omenetto, F.G. Light-activated shape morphing and light-tracking materials using biopolymer-based programmable photonic nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Ciou, J.-H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lee, P.S. Leaf-inspired multiresponsive MXene-based actuator for programmable smart devices. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lau, G.C.; Yuan, H.; Aggarwal, A.; Dominguez, V.L.; Liu, S.; Sai, H.; Palmer, L.C.; Sather, N.A.; Pearson, T.J.; et al. Fast and programmable locomotion of hydrogel-metal hybrids under light and magnetic fields. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Iscen, A.; Sai, H.; Sato, K.; Sather, N.A.; Chin, S.M.; Álvarez, Z.; Palmer, L.C.; Schatz, G.C.; Stupp, S.I. Supramolecular–covalent hybrid polymers for light-activated mechanical actuation. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. et al. Photothermal bimorph actuators with in-built cooler for light mills, frequency switches, and soft robots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 340, 1808995.

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, B.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H. Direct Laser Writing of Superhydrophobic PDMS Elastomers for Controllable Manipulation via Marangoni Effect. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Dong, B.; Sitti, M. In-air fast response and high speed jumping and rolling of a light-driven hydrogel actuator. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.L.; Du, C.; Dai, Y.; Daab, M.; Matejdes, M.; Breu, J.; Hong, W.; Zheng, Q.; Wu, Z.L. Light-steered locomotion of muscle-like hydrogel by self-coordinated shape change and friction modulation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xuan, C.; Qian, X.; Alsaid, Y.; Hua, M.; Jin, L.; He, X. Soft phototactic swimmer based on self-sustained hydrogel oscillator. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, A.; Naidu, A.; Napier, B.S.; Li, W.; Rodriguez, C.L.; Crooker, S.A.; Omenetto, F.G. Flexible magnetic composites for light-controlled actuation and interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 8119–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kim, T.; Guidetti, G.; Wang, Y.; Omenetto, F.G. Optomechanically Actuated Microcilia for Locally Reconfigurable Surfaces. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2004147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, B.; Sun, H. Light-Mediated Manufacture and Manipulation of Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8328–8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wang, L.; Feng, W. Light-driven bimorph soft actuators: design, fabrication, and properties. Mater. Horizons 2020, 8, 728–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Han, D.; Mao, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H. Bioinspired Soft Robots Based on the Moisture-Responsive Graphene Oxide. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. J. Lin, S. Y. Zhang, Y. Xiao, C. J. Zhang, J. X. Zhu, J. W. C. Dunlop, et al., Organic molecule-driven polymeric actuators. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2019, 40, 1800896.

- Tan, H.; Liang, S.; Yu, X.; Song, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, L. Controllable kinematics of soft polymer actuators induced by interfacial patterning. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 5410–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Naumov, P.; Du, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Vapomechanically Responsive Motion of Microchannel-Programmed Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Du, X.; He, P.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Guo, W. Smart Bilayer Polyacrylamide/DNA Hybrid Hydrogel Film Actuators Exhibiting Programmable Responsive and Reversible Macroscopic Shape Deformations. Small 2020, 16, e1906998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.; Kim, S.J.; Park, M.J. Low-voltage-driven soft actuators. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4895–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Cohen, Y.; Anderson, I.A. Electroactive polymer (EAP) actuators—background review. Mech. Soft Mater. 2019, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Cho, J.; Song, D.S.; Jang, J.H.; Jho, J.Y.; Park, J.H. High-Performance Electroactive Polymer Actuators Based on Ultrathick Ionic Polymer–Metal Composites with Nanodispersed Metal Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 21998–22005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Santaniello, T.; Bettini, L.G.; Minnai, C.; Bellacicca, A.; Porotti, R.; Denti, I.; Faraone, G.; Merlini, M.; Lenardi, C.; et al. Electroactive Ionic Soft Actuators with Monolithically Integrated Gold Nanocomposite Electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Kong, X.; Ni, Y.; Ren, Z.; Li, S.; Nie, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Ionic polymer-metal composites actuator driven by the pulse current signal of triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barpuzary, D.; Ham, H.; Park, D.; Kim, K.; Park, M.J. Smart Bioinspired Actuators: Crawling, Linear, and Bending Motions through a Multilayer Design. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 50381–50391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Q. Field-Activated Electroactive Polymers. MRS Bull. 2008, 33, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Plamthottam, R.; Pei, Q. Dielectric Elastomer Artificial Muscle: Materials Innovations and Device Explorations. Accounts Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Review of Dielectric Elastomer Actuators and Their Applications in Soft Robots. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Fang, C.; Lu, Y.; Gao, X.; Cao, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.L. TENG-Bot: Triboelectric nanogenerator powered soft robot made of uni-directional dielectric elastomer. Nano Energy 2021, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.-H.; Jeong, S.M.; Hwang, G.; Kim, H.; Hyeon, K.; Park, J.; Kyung, K.-U. Dielectric Elastomer Actuator for Soft Robotics Applications and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Hussain, A.M.; Duduta, M.; Vogt, D.M.; Wood, R.J.; Clarke, D.R. Compact Dielectric Elastomer Linear Actuators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Luo, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, D.; Li, P. A bio-inspired soft-rigid hybrid actuator made of electroactive dielectric elastomers. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 21, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, X.; Mao, J.; Zhao, J.; Gao, X.; Li, T.; Luo, Y. Intrinsically Anisotropic Dielectric Elastomer Fiber Actuators. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortos, A.; Mao, J.; Mueller, J.; Hajiesmaili, E.; Lewis, J.A.; Clarke, D.R. Printing Reconfigurable Bundles of Dielectric Elastomer Fibers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Ma, Y. Zhang, Y. Liang, L. Ren, W. Tian, L. Ren, High-performance ionic-polymer metal composite: toward large-deformation fast-response artificial muscles. Advanced Functional Materials 2019, 30, 1908508.

- Cezar C A, Kennedy S M, Mehta M, et al. Biphasic ferrogels for triggered drug and cell delivery. Advanced healthcare materials 2014, 3, 1869–1876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrínyi M, Barsi L, Büki A. Deformation of ferrogels induced by nonuniform magnetic fields. The Journal of chemical physics 1996, 104, 8750–8756. [CrossRef]

- Haider H, Yang C H, Zheng W J, et al. Exceptionally tough and notch-insensitive magnetic hydrogels. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 8253–8261. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmauch M M, Mishra S R, Evans B A, et al. Chained iron microparticles for directionally controlled actuation of soft robots. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2017, 9, 11895–11901.

- Kim J, Chung S E, Choi S E, et al. Programming magnetic anisotropy in polymeric microactuators. Nature materials 2011, 10, 747–752. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb R M, Martin J J, Soheilian R, et al. Actuating soft matter with magnetic torque. Advanced Functional Materials 2016, 26, 3859–3880. [CrossRef]

- Roeder L, Bender P, Tschöpe A, et al. Shear modulus determination in model hydrogels by means of elongated magnetic nanoprobes. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2012, 50, 1772–1781. [CrossRef]

- Lisjak, D.; Mertelj, A. Anisotropic magnetic nanoparticles: A review of their properties, syntheses and potential applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 95, 286–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert J, Roitsch S, Schmidt A M. Covalent Hybrid Elastomers Based on Anisotropic Magnetic Nanoparticles and Elastic Polymers. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2021, 3, 1324–1337. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Stogin, B.B.; Sun, N.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Wong, T. A Switchable Cross-Species Liquid Repellent Surface. Adv. Mater. 2016, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen L, Springsteen K, Feldstein H, et al. Development and validation of a dynamic model of magneto-active elastomer actuation of the origami waterbomb base. Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics 2015, 7, 011010. [CrossRef]

- Crivaro A, Sheridan R, Frecker M, et al. Bistable compliant mechanism using magneto active elastomer actuation. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2016, 27, 2049–2061. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yuk, H.; Zhao, R.; Chester, S.A.; Zhao, X. Printing ferromagnetic domains for untethered fast-transforming soft materials. Nature 2018, 558, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnetic Multimaterial Printing for Multimodal Shape Transformation with Tunable Properties and Shiftable Mechanical Behaviors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 12639–12648. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, O. Wang, Y. Tian, et al. Selective Laser Sintering-Based 4D Printing of Magnetism-Responsive Grippers. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2021, 13, 12679–12688.

- Shcherbakov V P, Winklhofer M. Bending of magnetic filaments under a magnetic field. Physical Review E 2004, 70, 061803. [CrossRef]

- Dzhezherya Y I, Xu W, Cherepov S V, et al. Magnetoactive elastomer based on superparamagnetic nanoparticles with Curie point close to room temperature. Materials & Design 2021, 197, 109281.

- Fahrni F, Prins M W J, Van IJzendoorn L J. Magnetization and actuation of polymeric microstructures with magnetic nanoparticles for application in microfluidics. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 2009; 321, 1843–1850.

- Evans, B.A.; Fiser, B.L.; Prins, W.J.; Rapp, D.J.; Shields, A.R.; Glass, D.R.; Superfine, R. A highly tunable silicone-based magnetic elastomer with nanoscale homogeneity. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Huang, T.-Y.; Luo, Z.; Testa, P.; Gu, H.; Chen, X.-Z.; Nelson, B.J.; Heyderman, L.J. Nanomagnetic encoding of shape-morphing micromachines. Nature 2019, 575, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadhel A, Kosel J. Magnetic nanocomposite cilia tactile sensor. Advanced Materials, 2015; 27, 7888–7892.

- Zhang J, Ren Z, Hu W, et al. Voxelated three-dimensional miniature magnetic soft machines via multimaterial heterogeneous assembly. Science robotics, 2021; 6, eabf0112.

- Kennedy, S.; Roco, C.; Déléris, A.; Spoerri, P.; Cezar, C.; Weaver, J.; Vandenburgh, H.; Mooney, D. Improved magnetic regulation of delivery profiles from ferrogels. Biomaterials 2018, 161, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X.; Lu, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T. Recent Progress in Biomimetic Anisotropic Hydrogel Actuators. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.-L.; Su, Y.-X.; Yin, H.; Li, C.; Zhu, M.-Q. Visible-light-driven isotropic hydrogels as anisotropic underwater actuators. Nano Energy 2021, 85, 105965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yin, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, T. Shape Morphing of Hydrogels in Alternating Magnetic Field. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21194–21200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang Gao, Xiuyuan Han, Jiaojiao Chen, Yudong Pan, Meng Yang, Linhe Lu, Jian Yang, Zhigang Suo, Tongqing Lu. Hydrogel–mesh composite for wound closure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118, e2103457118.

- Yang, H.; Ji, M.; Yang, M.; Shi, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Qi, H.J.; Suo, Z.; Tang, J. Fabricating hydrogels to mimic biological tissues of complex shapes and high fatigue resistance. Matter 2021, 4, 1935–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Pan, Y.; Du, Z.; Blanchet, J.; Suo, Z.; Lu, T. High-throughput experiments for rare-event rupture of materials. Matter 2022, 5, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, D.; Xue, Y.; Yang, X.; Che, L.; Li, D.; Xiao, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Versatile and Simple Strategy for Preparing Bilayer Hydrogels with Janus Characteristics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 4579–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Alsaid, Y.; Wang, X.; Hua, M.; Galy, T.; Gopalakrishna, H.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Liu, N.; et al. Artificial phototropism for omnidirectional tracking and harvesting of light. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhang, X.; Du, F.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lei, Z.; Lu, W.; Zhang, F.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; et al. Self-regulated underwater phototaxis of a photoresponsive hydrogel-based phototactic vehicle. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 19, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ruan, Q.; Nasseri, R.; Zhang, H.; Xi, X.; Xia, H.; Xu, G.; Xie, Q.; Yi, C.; Sun, Z.; et al. Light-Fueled Hydrogel Actuators with Controlled Deformation and Photocatalytic Activity. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2204730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Zhu, Y. Lu, L. X. Jiang, Y. L. Yu, Liquid crystal soft actuators and robots toward mixed reality. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2009835. [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Teh, Y.S.; Bhattacharya, K. Collective behavior in the kinetics and equilibrium of solid-state photoreaction. Extreme Mech. Lett. 2020, 43, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Bhattacharya, K. Photomechanical coupling in photoactive nematic elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2020, 144, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Cheng, H. Zeng, Y. F. Li, J. X. Liu, D. Luo, A. Priimagi, et al., Light-fueled polymer film capable of directional crawling, friction-controlled climbing, and self-sustained motion on a human hair. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2103090. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Yong, K.-T.; Gu, G. Stimuli-responsive functional materials for soft robotics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8972–8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Lv, J.-a.; Zhu, C.; Qin, L.; Yu, Y. Photodeformable Azobenzene-Containing Liquid Crystal Polymers and Soft Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bisoyi, H.K.; Huang, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, Q. Healable and Rearrangeable Networks of Liquid Crystal Elastomers Enabled by Diselenide Bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 16394–16398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Bai, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Wiesner, L.W.; Silberstein, M.; Shepherd, R.F. Digital light processing of liquid crystal elastomers for self-sensing artificial muscles. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, P.; Yang, X.; Bisoyi, H.K.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xue, P.; Shi, S.; Priimagi, A.; Wang, L.; et al. Stimulus-driven liquid metal and liquid crystal network actuators for programmable soft robotics. Mater. Horizons 2021, 8, 2475–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-C.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Tong, X.; Zhao, Y. Selective Decrosslinking in Liquid Crystal Polymer Actuators for Optical Reconfiguration of Origami and Light-Fueled Locomotion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5332–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verpaalen, R.C.P.; da Cunha, M.P.; Engels, T.A.P.; Debije, M.G.; Schenning, A.P.H.J. Liquid Crystal Networks on Thermoplastics: Reprogrammable Photo-Responsive Actuators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4532–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Annapooranan, R.; Zeng, J.; Chen, R.; Cai, S. Electrospun liquid crystal elastomer microfiber actuator. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Guo, Y.; Bae, J.; Choi, S.; Song, H.Y.; Park, S.; Hyun, K.; Ahn, S. 4D Printing of Hygroscopic Liquid Crystal Elastomer Actuators. Small 2021, 17, 2100910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-C.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Cheng, R.-D.; Hou, J.-B.; Zhao, Y. Dynamic Liquid Crystalline Networks for Twisted Fiber and Spring Actuators Capable of Fast Light-Driven Movement with Enhanced Environment Adaptability. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 6541–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Song, Y. Zhang, J. Bao, et al. Photo-responsive Programmable Shape-Memory Soft Actuator Based on Liquid Crystalline Polymer/Polyurethane Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213771. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Gao, E.; Tian, B.; Liang, J.; Liu, Q.; Xue, E.; Shao, Q.; Wu, W. Modularized Paper Actuator Based on Shape Memory Alloy, Printed Heater, and Origami. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Hyun-Taek, F. Seichepine, G. Yang. Microtentacle Actuators Based on Shape Memory Alloy Smart Soft Composite. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 2002510. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yuan, C.; Wan, C.; Gao, X.; Bowen, C.; Pan, M. Soft Self-Healing Robot Driven by New Micro Two-Way Shape Memory Alloy Spring. Adv. Sci. 2023, 11, e2305163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-Y.; Fang, Q.-Y.; Xu, Z.-L.; Li, X.-J.; Ma, W.-X.; Chu, M.-S.; Lim, J.H.; Chuang, K.-C. Knitting Shape-Memory Alloy Wires for Riding a Robot: Constraint Matters for the Curvilinear Actuation. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulakkal, M.C.; Trask, R.S.; Ting, V.P.; Seddon, A.M. Responsive cellulose-hydrogel composite ink for 4D printing. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, P.; Liu, R.; Song, B. Rational design of a porous nanofibrous actuator with highly sensitive, ultrafast, and large deformation driven by humidity. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2020, 330, 129236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Jia, S.; Ma, C.; Shao, Z. Tough and Multifunctional Composite Film Actuators Based on Cellulose Nanofibers toward Smart Wearables. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38700–38711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Han, B.; Zhu, L.; Dong, B.; Sun, H.-B. Gradient Assembly of Polymer Nanospheres and Graphene Oxide Sheets for Dual-Responsive Soft Actuators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37130–37138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Huang, G. Zhu, S. Z. Wang, Q. Y. Li, J. Viguie, H. He, et al., A gradient poly(vinyl alcohol)/polysaccharides composite film towards robust and fast stimuli-responsive actuators by interface co-precipitation. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2021, 9, 22973–22981. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Hu, Z. Poly (vinyl alcohol) based gradient cross-linked and reprogrammable humidity-responsive actuators. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2021, 349, 130735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Cao, R.; Ye, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, Y.; Ge, D.; Yang, X. A bio-inspired homogeneous graphene oxide actuator driven by moisture gradients. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 3126–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-N.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Han, D.-D.; Mao, J.-W.; Chen, Z.-D.; Sun, H.-B. Programmable deformation of patterned bimorph actuator swarm. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Gao, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Ma, Z.-C.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Q.-D.; Sun, H.-B. Multi-field-coupling energy conversion for flexible manipulation of graphene-based soft robots. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.V.; Pan, K. An asymmetric graphene oxide film for developing moisture actuators. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 14060–14066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, J.E.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, S.; Zhang, K.A.I.; Byun, J. Controllable porous membrane actuator by gradient infiltration of conducting polymers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 5007–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, G.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Programmable micropatterned surface for single-layer homogeneous-polymer Janus actuator. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 430, 133052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Serpe, M.J. Stimuli-responsive polymers for sensing and actuation. Mater. Horizons 2019, 6, 1774–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Serpe, M.J. Harnessing the Power of Stimuli-Responsive Polymers for Actuation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Kang, D.; Lee, H.; Koh, W.-G. Multi-stimuli responsive and reversible soft actuator engineered by layered fibrous matrix and hydrogel micropatterns. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 427, 130879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, B.; Li, X.; Dong, L.; Zhang, M.; Zou, J.; Gu, G. Dexterous electrical-driven soft robots with reconfigurable chiral-lattice foot design. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, X.; Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, B.; Yin, S.; et al. Self-powered soft robot in the Mariana Trench. Nature 2021, 591, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shan, X.; Li, R.; Hou, C. Review on the Vibration Suppression of Cantilever Beam through Piezoelectric Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, J.; Wu, J.; Xin, X.; Li, Z.; Yuan, X.; Shen, X.; Dong, S. Piezoelectric Actuators and Motors: Materials, Designs, and Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, J.; Wu, P.; Zhao, G.; Qu, Q.; Yu, X. Recent Advances in Electrically Driven Soft Actuators across Dimensional Scales from 2D to 3D. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Ma, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Chu, Y.; Karakurt, I.; Bogy, D.B.; Lin, L. A Flexible Piezoelectret Actuator/Sensor Patch for Mechanical Human–Machine Interfaces. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7107–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafkhani, S.; Kokabi, M. High performance flexible actuator: PVDF nanofibers incorporated with axially aligned carbon nanotubes. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2021, 222, 109060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Varghese, A.; Sharma, A.; Prasad, M.; Janyani, V.; Yadav, R.; Elgaid, K. Recent development and futuristic applications of MEMS based piezoelectric microphones. Sensors Actuators A: Phys. 2022, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Unnikrishnan, L.; Nayak, S.K.; Mohanty, S. Advances in Piezoelectric Polymer Composites for Energy Harvesting Applications: A Systematic Review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2018, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fath, A.; Xia, T.; Li, W. Recent Advances in the Application of Piezoelectric Materials in Microrobotic Systems. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Han, S.A.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Lee, S.-W. Biomolecular Piezoelectric Materials: From Amino Acids to Living Tissues. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yim, J.K.; Liang, J.; Shao, Z.; Qi, M.; Zhong, J.; Luo, Z.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Insect-scale fast moving and ultrarobust soft robot. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yim, J.K.; Chen, H.; Miao, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Qiu, W.; et al. Electrostatic footpads enable agile insect-scale soft robots with trajectory control. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, G.W.; Getzler, Y.D.Y.L. Chemical recycling to monomer for an ideal, circular polymer economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R., Yang, J. and Suo, Z. Fatigue of hydrogels. European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids 2019, 74, 337–370. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Dhyani, A.; Repetto, T.; Gayle, A.J.; Cho, T.H.; Dasgupta, N.P.; Tuteja, A. Durable Liquid- and Solid-Repellent Elastomeric Coatings Infused with Partially Crosslinked Lubricants. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 22466–22475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, N.; Tierney, R.; Li, H.; Corsetti, M.; Williams, L.; Wong, P.K.; Wong, T.-S. Viscoelastic solid-repellent coatings for extreme water saving and global sanitation. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).