1. Introduction

The distinctive nature of rare human monogenic diseases, characterized by the limited number of patients available worldwide and restricted access to the most affected tissues, poses challenges in unravelling of the molecular, cellular, tissue, and organ-level processes that sustain the disease condition and influence the response to treatment. Within this context, the ability to reprogram somatic cells to induce pluripotency has revolutionized the approach to modelling human disease. One of the rare diseases that could benefit from this approach is Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia (NKH), a neurometabolic disorder characterized by severe brain malformations and life-threatening neurological manifestations. Classic NKH (MIM#605899) is an autosomal recessive disorder that results from deficient activity of the multi-enzyme mitochondrial complex Glycine Cleavage System (GCS) [

1]. GCS mediates the decarboxylation of glycine with a concomitant transfer of a one-carbon group to tetrahydrofolate (THF), resulting in the production of 5,10-methylene-THF. In this way, GCS contributes to maintaining the flux of the serine-glycine-one carbon metabolic pathway. The GCS complex consists of four components: a pyridoxal-dependent glycine decarboxylase (GCSP), encoded by the

GLDC gene (MIM*238300) responsible for catalyzing the decarboxylation of glycine with CO

2 release; the amino-methyltransferase, a tetrahydrofolate-dependent GCST protein encoded by the

AMT gene (MIM*238310); a NAD

+-dependent dihydro-lipoamide dehydrogenase; and a small lipoylated H protein encoded by the

GCSH gene (MIM*238330), capable of interacting with the other subunits. The GCSH protein is responsible for the transferring of lipoic acid to other mitochondrial apo-enzymes, including the E2 subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase and the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complexes [

2,

3]. Mutations in

GLDC or

AMT genes can lead to the accumulation of glycine in biological fluids, particularly in cerebrospinal fluid, serving as the biochemical hallmark of NKH. More than 70% of NKH patients carry mutations in the

GLDC gene.

The severe neurological symptoms observed in NKH patients have been linked for years to an excess of glycine, which acts on both NMDA receptors in the cortex and glycine receptors in the spinal cord and brain stem neurons [

4]. However, glycine metabolism is intimately connected to the maintenance of cellular pools of one-carbon residues. These residues are essential not only for donating methyl groups for the synthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and phospholipids but also for remodeling the epigenetic state of the cell. This includes the changes that occur during the reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotent iPSCs [

5].

These two faces for explaining the effect of GCS deficiency in the NKH disease condition were previously proposed [

6] and it seems to be supported by data in

Gldc-/- mice, indicating the involvement of impaired folate 1-carbon metabolism [

7] in specific aspects of NKH pathogenesis. Additionally, a strong relationship exists between neural tube disorders (NTDs) and

GLDC or

AMT mutations [

7,

8].

Several studies have indicated that astrocytes, which comprise most of the cell population in the human brain, play a key role in the serine-glycine-one carbon metabolism. Here, we utilized a human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) model [

9] derived from fibroblasts of a severe NKH patient with hypomorphic

GLDC mutations [

10] to investigate the effects of

GLDC deficiency on cell metabolism, bioenergetics, growth, and cell cycle, from pluripotent iPSCs to differentiated neural cells.

3. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to establish a valid human model of

GLDC deficiency to serve as a basis for testing potential therapeutic strategies in Nonketotic Hyperglycinemia (NKH). We generated a human iPSCs line that exhibited biochemical characteristics of

GLDC deficiency while maintaining pluripotency, the capability to differentiate into three germ layers and genomic stability [

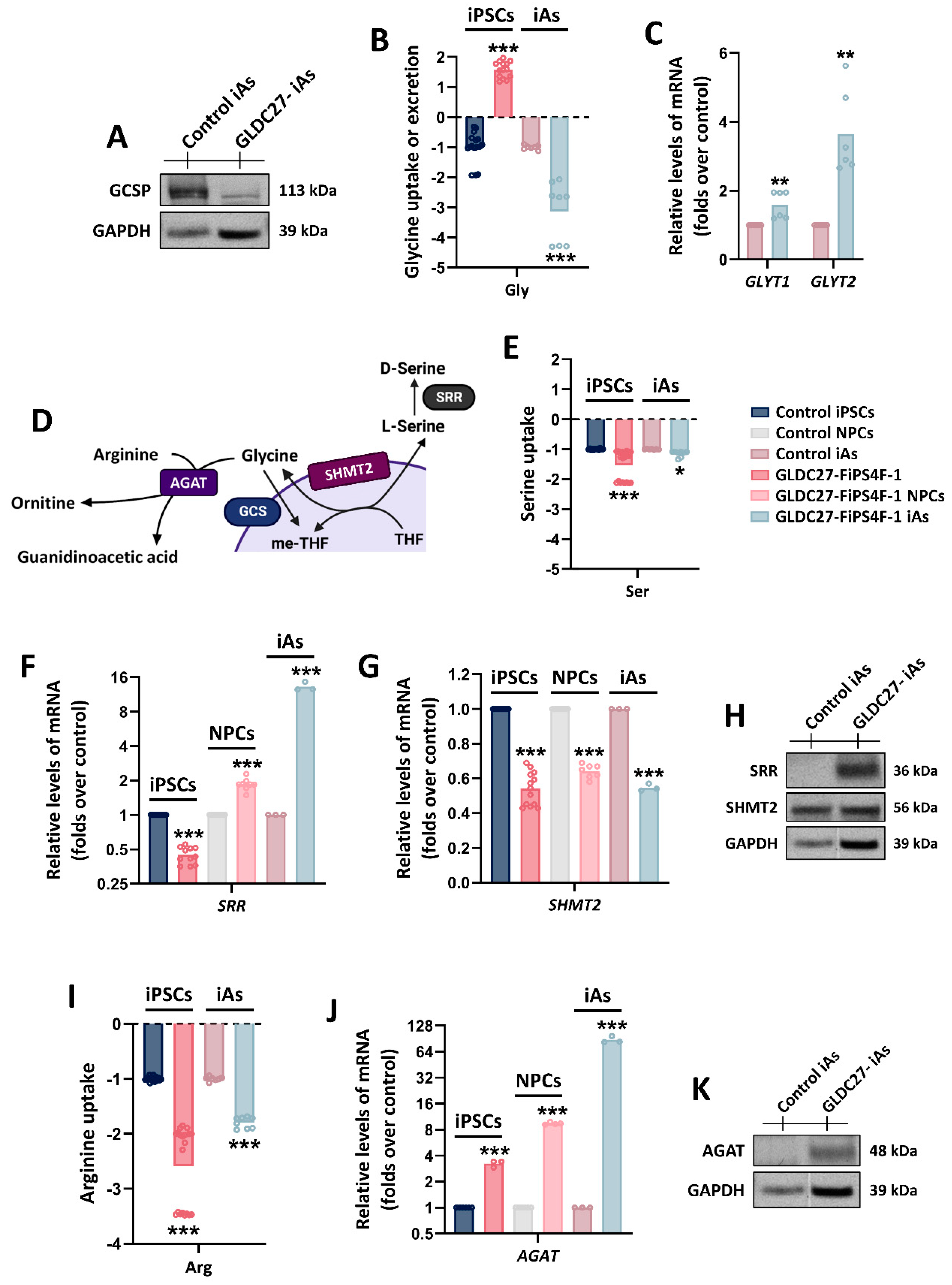

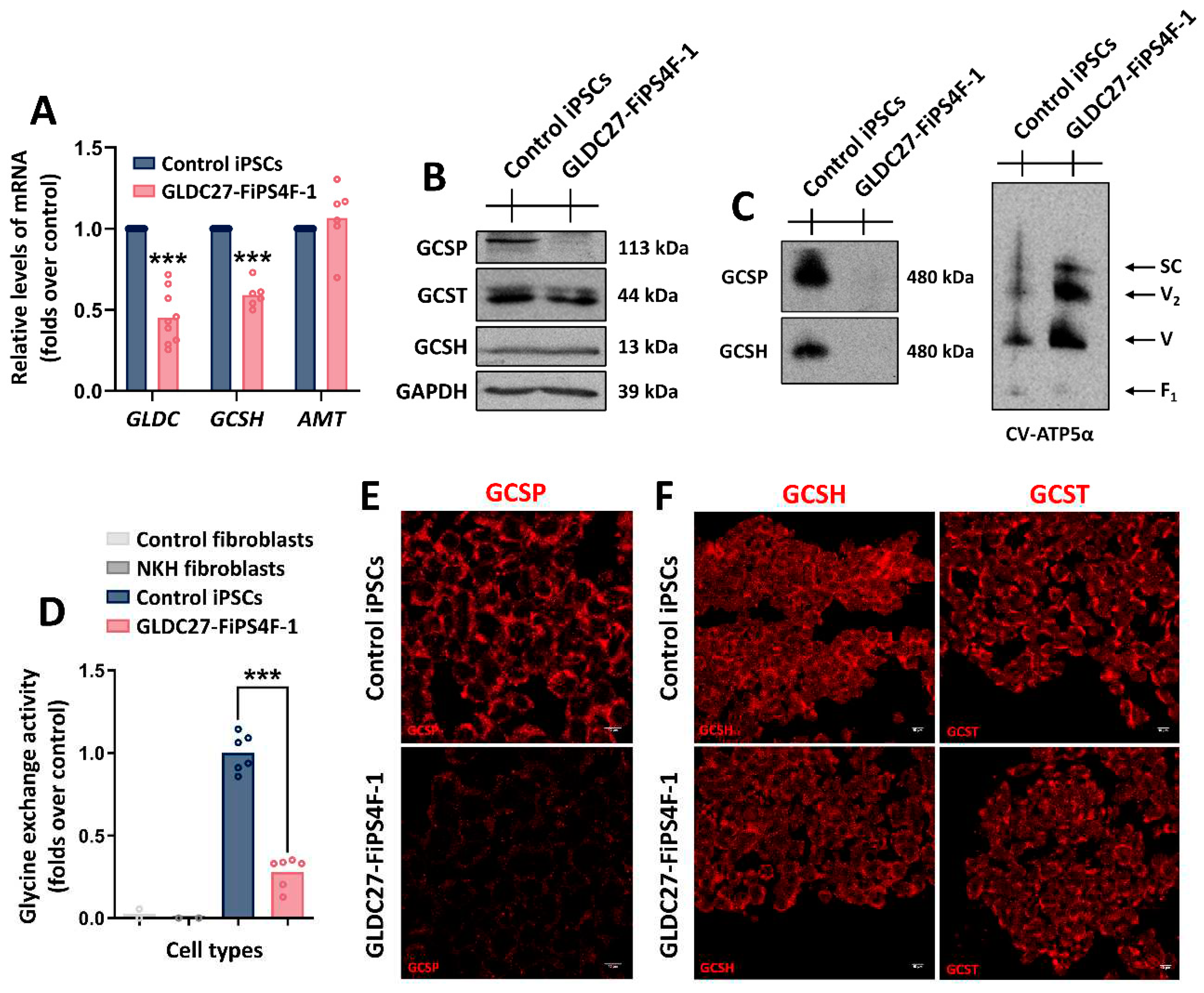

9]. The GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line showed a noteworthy decrease in the amounts of GCSP protein and the assembled GCS complex. The decarboxylase activity in this line was only 15% of that in the control line. Due to the impaired ability of the NKH line to catabolize glycine, there was an accumulation of this amino acid in the culture medium. In contrast, the control line required the uptake glycine. We hypothesize that this remaining GCS activity enables the cells to survive and develop adaptive mechanisms to compensate for the reduced enzyme activity.

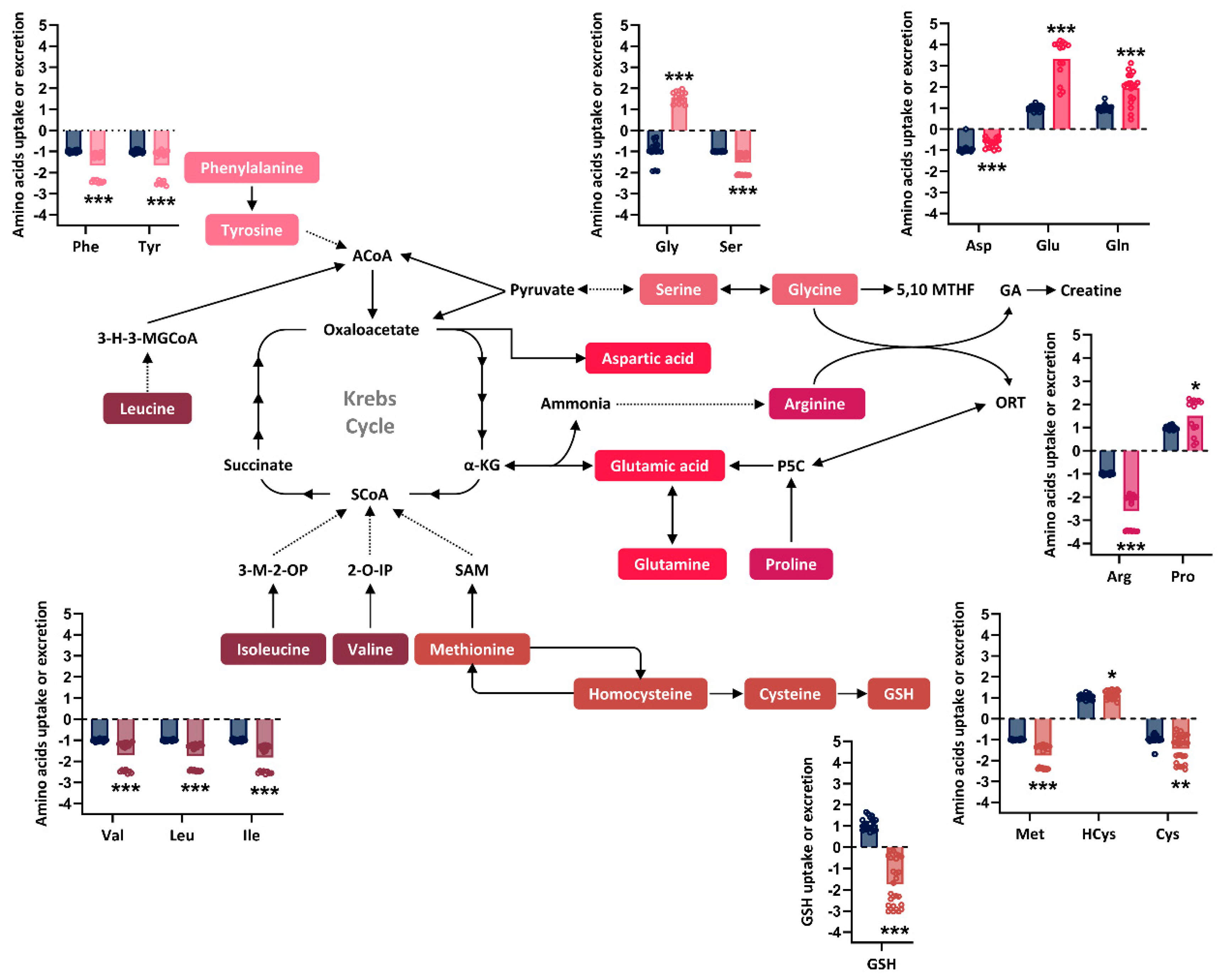

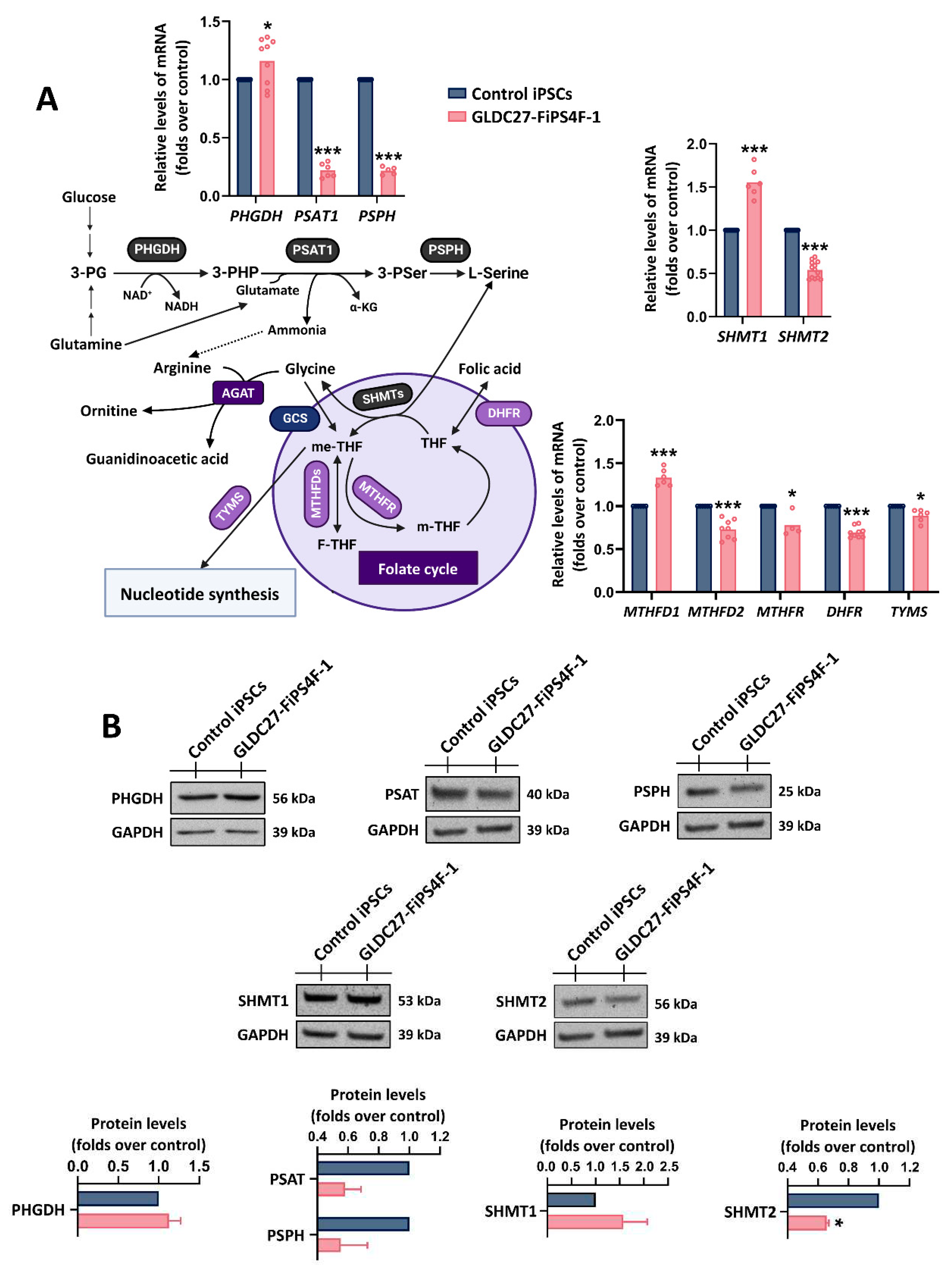

The impact of

GLDC deficiency on cellular metabolism was evaluated by quantifying specific sets of metabolites and proteins. Previous studies had reported disturbances in the serine shuttle and metabolism in NKH patients [

11]. In GLDC27-FiPS4F-1, we observed an increased demand for serine, methionine, and cysteine from the extracellular milieu, which could be understood in the context of the cellular response to maintain 5,10-methylen-THF. We investigated whether this specific metabolite pattern could be explained by a down or up-regulation of specific metabolic pathways related to the serine-glycine-one-carbon metabolism. The “de novo” process of serine synthesis begins with 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG), which is then sequentially processed by the enzymes PHGDH, PSAT1, and PSPH. Our findings indicate a significant increase in

PHGDH expression, accompanied by a decrease in

PSAT1 and

PSPH gene expression in the patient-derived line.

The main function of PHGDH in proliferative cells is to maintain folate stores intended for nucleotide synthesis [

12]. Consistent with the significant reduction in NADH production via the GCS flux, GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 cells seemed to process 3-PG to obtain NADH but reduced the expression of the other enzymes in the pathway, resulting in poor L-serine synthesis. This could justify the increase in serine uptake from the medium. We also detected impairment in mitochondrial

SHMT2 and

MTHFD2 and increases in the cytosolic

SHMT1 and

MTHFD1. These variations from normal flux may reflect a compensatory cytosolic mechanism to reverse the loss of mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism, like that described in [

13] for proliferating mammalian cell lines. Our study found that despite the metabolic shift to meet the proliferative demand of the iPSCs, there was a concomitant alteration in cell growth and cell cycle progression, with a significant number of cells in quiescence. This was consistent with the decreased demand for aspartate and a nearly 50% decline in levels of nucleotide metabolites, as described in [

14]. Furthermore, in line with earlier findings in mouse models and human cells [

15], culture medium from GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 exhibited a substantial decrease in glutathione levels, probably implying a greater necessity to counteract ROS production.

The data support a metabolic rewiring at the pluripotent stage in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1, which is necessary but probably insufficient to meet the changing biosynthetic demands at different cell cycle stages and could influence cell fate during the differentiation process. The expression of GCS in radial glia has been proposed as a relevant factor in the proper development of the cerebral cortex [

16]. We evaluated the capacity of iPSCs to differentiate into astrocytes through an intermediate stage of neural progenitors capable of producing neurons and glial cells.

The loss of

OCT3/4 and

LIN28B markers, accompanied by the gain of

PAX6,

NES, and

SOX1 expression compared to the iPSC stage, confirmed that both cell lines correctly differentiated to the NPC stage [

17]. Differences in morphology and expression of neuroepithelial and neuronal lineage markers, which appeared up-regulated, were observed in the patient-derived NPC line. This observation may indicate premature senescence and differentiation, in agreement with the reduced cell viability and proliferative capacity measured in patient-derived iPSCs [

18,

19]. To characterize iAs, we evaluated an extensive set of astrocytic markers including

GFAP,

S100ß,

ALDH1L1,

AQP4,

APOE,

GLAST, and

GLT-1 [

20,

21,

22]. All markers exhibited significantly higher expression in iAs compared to NPCs, confirming their higher degree of astroglia differentiation. However, we noted differences in the morphology and relative expression of specific markers between control and patient-derived iAs. The control group displayed a quiescent morphology, characterized by reduced expression of

GFAP and

GLAST, and increased level of

GLT-1, all of which are typical of mature astrocytes [

23]. In contrast, the iAs derived from the patient showed a fibrous or radial morphology. Relative to the control group, these cells exhibited reduced

GLT-1 expression and significant increases in

GFAP and

GLAST expression. Such changes have also been observed in radial glia and astrocytes [

24], supporting the notion that a considerable proportion of radial glia cells are present in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs [

25,

26,

27]. Elevated

GFAP expression has also been linked to reactive phenotypes associated with pathological conditions [

20,

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, we observed increased expression of the neuronal markers

MAP2 and

NeuN in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs, indicating the presence of mature neurons in this culture. A ten-fold increase in

SRR gene expression detected in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs culture corroborated these findings [

27]. Additionally, the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs culture exhibited significant increases in glutamate and glycine uptake, along with elevated expression of glycine transporters (

GLYT1 and

GLYT2) [

32,

33]. Considering the presence of neurons, these changes may represent a regulatory response to maintain neurotransmitter balance in an active neural network, as both amino acids serve as neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS) [

30].

Finally, we hypothesized that

GLDC-deficient cells would activate metabolic pathways to re-establish glycine homeostasis. We observed a significant increase in arginine absorption, accompanied by substantial upregulation in

AGAT gene expression at both the iPSC and iA stages. This pattern is compatible with an increased synthesis of guanidinoacetate like that described in the brains of adult

Gldc-deficient mice [

31]. Such upregulation could adjust the intracellular glycine concentration by enhancing the synthesis of guanidinoacetate, acting as an 'exit strategy.'

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture Conditions

Healthy CC2509 fibroblasts (Lonza, Basel, CHE) and patient-derived fibroblasts were cultivated according to standard procedures and used before reaching 10 passages. In brief, the cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) (Sigma- Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 1% (v/v) glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and a 0.1% antibiotic mixture (penicillin/streptomycin) under standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 95% relative humidity, 5% CO2).

4.2. iPSCs Characteristics

One healthy control iPSCs line (registered as FiPS Ctrl2-SV4F-1), matched for age, sex, ethnicity and reprograming method with the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line used in this study, was obtained from the Banco Nacional de Líneas Celulares of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. The GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line was reprogrammed at our laboratory [

9] from NKH patient-derived fibroblasts who suffered a severe clinical course and carried two biallelic variants in the GLDC gene that led to a significant decrease in protein levels and exchange activity in vitro, as previously described [

10]. These were then registered in the Banco Nacional de Líneas Celulares of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III as GLDC27-FiPS4F-1.

4.3. Genetic Background of the iPSCs Lines

Prior to beginning iPSCs differentiation, we identified potential pathogenic nucleotide sequence variations in both cell lines using array CGH and whole exome sequencing. Variants from over 2000 genes were filtered based on minor allele frequency (MAF), while also considering commonly occurring mitochondrial DNA mutations in iPSCs clones. Annex 1 presents a summary of the identified variations in both cell lines.

4.4. Sample Collection and Metabolite Analysis

Harvested at two days of culture in mTeSR, six-well plates of each cell line, as described [

36], were counted. Aliquots of the spent-culture medium and the corresponding cells, without any residual medium, were collected separately and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until analysis. Blank culture medium samples were also collected and stored under the same conditions. Both medium and cell extracts were processed and deproteinized before measurement. Amino acids were measured by Ionic Exchange Chromatography (IEC). Purines and pyrimidines were determined by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) according to [

37,

38]. Total homocysteine, quantified after derivatization with SBD-F by HPLC with fluorescence detection, was measured as described in [

39,

40]. The results of the spent-culture medium represent the consumption or excretion values of the metabolite using the baseline value measured in the blank medium. Raw data were in pmol/µg protein /72h. Total protein concentrations were measured by Bradford’s assay.

4.5. Oxygen Consumption Rate (OCR) Evaluation

Cellular Consumption Respiration (OCR) was analyzed using the Flux Analyzer XFe96 (Agilent-Seahorse) device. We seeded iPSCs or NPCs on Matrigel-coated Seahorse XF96 cell plates. The test was carried out using the Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent). Before measurements, cells were washed and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in CO

2-free conditions in XF DMEM Medium pH 7.4 (Agilent), previously warmed and supplemented with pyruvate, glucose, and glutamine at final concentrations of 1mM, 10mM and 2mM, respectively. Subsequently, various drugs were sequentially injected to reach a final concentration of oligomycin (1.5μM), carbonyl-cyanide-p-trifluoro-methoxy phenylhydrazone (FCCP 20μM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM each). FCCP concentration was previously optimized through titration. Following the completion of the measurement, all wells in the p96 plate were stained with Hoechst (1:100) for 30 min at room temperature. The number of cells per well was quantified for data normalization using the Cytation 5 image reader. The data obtained were processed using software provided by the manufacturer (

seahorseanalytics.agilent.com).

4.6. Cell Viability and Cycle Progression

Cell viability assays were conducted 72 h after plating iPSCs seeded at varying densities (10,000; 20,000 and 40,000 cells per well) using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation kit® on 96-well plates, following the manufacturer’s protocol. For cell cycle analysis via flow cytometry, iPSCs prepared as described in [

27] were treated with Propidium Iodide/RNase Staining Buffer (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 minutes at 37°C in darkness. The data were collected using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and FACSDiva software. The relative percentages of cells in the sub-G1/G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle were determined using FlowJo v.2.0 software.

4.7. RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol and subsequently converted to cDNA with the NZY First-Strand cDNA Synthesis (NZYTech) kit. Amplification was performed using Perfecta SYBR Master Mix (Quantabio) on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). Primers were designed by using the Primer3 software. For data normalization, three different genes -

ACTB, GAPDH and

GUSB - were initially analyzed, with

ACTB proving to be the most stable. Relative quantification was carried out using the standard 2-

ΔΔCt method. See

Table S1 for primers sequences.

4.7. Mitochondrial DNA Content

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content was calculated using quantitative RT-PCR by measuring the threshold cycle ratio (ΔCt) of the mitochondria-encoded genes mtDNA ND1 and 12S and the nuclear 18S. Data were expressed as mtDNA/nuclear DNA (nDNA).

4.8. Enzymatic Activity

GCSP protein enzymatic activity was determined in triplicate using the exchange reaction between radio-labeled bicarbonate NaH

14CO

3 and glycine as described in [

41]. The results were normalized to protein levels measured by Lowry method [

42].

4.9. Protein Levels by SDS Western Blot

Cell lysates were prepared using a lysis buffer (2% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. The resulting supernatants were used for western blotting, with protein concentration determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Electrophoretic separation was performed using two different systems: NuPAGE gradient gels of 4-12% acrylamide or manually prepared 10% acrylamide/bisacrylamide gels. Both systems employed Lonza’s ProSieve™ Color Protein Markers as molecular weight standards. Following electrophoresis, gels were transferred onto 0.2 mm nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot Gel Transfer Stacks Nitrocellulose Regular system. In all studies, detection was achieved using a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody, followed by membrane development with ECL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Band intensities were quantified using a BioRad G-8000 scanner. The specific antibodies used in this study are listed in

Table S2.

4.10. Protein Complex Analysis in Native Conditions

The analysis of the GCS complex was conducted using the NativePAGE™ Novex® Bis-Tris Gel System (Invitrogen). Cell sediments were resuspended in a mixture of 2% digitonin, 4X Sample Buffer and dH

2O and incubated for 15 min at 4°C. This was followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 15 min to collect the supernatant, whose protein concentration was measured using the Bradford method. Prior to loading onto NativePAGE™ Novex 3-12% gels, G-250 additive was added to the samples. The electrophoretic separation was carried out in two phases. After separation, the gels were washed and incubated with 2 x transfer buffer, and then transferred to PVDF membranes with the iBlot™ 2 Gel Transfer Device (Invitrogen). This was followed of an incubation with 8% acetic acid and subsequent washing with 100% methanol. Finally, the immunodetection procedure was performed using primary and secondary antibodies, as detailed in

Table S2.

4.11. Immunofluorescence Staining

For Immunofluorescence staining, cells were fixed in 10% formalin for 20 min at room temperature, washed with 0.1% PBS-Tween, and permeabilized with PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. The cells were then incubated in a blocking solution for a minimum of 30 min. Following this, cells were incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies at appropriate concentrations (

Table S2). Next, secondary antibodies, already conjugated to fluorophores (ThermoFisher), were incubated in the blocking solution at the appropriate concentrations for 30 min. To stain cell nuclei, DAPI at a dilution 1:5,000 (Merck) was used. The cells were then mounted using Prolong Diamond Antifade (ThermoFisher). The samples were examined using an Axiovert200 inverted microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with GFP, DsRed and Cy5 fluorescence filters (10X, 25X and 40X). Image visualization and fluorescence quantification were carried out using the ImageJ-FiJi software.

4.12. Differentiation to Neural Progenitor Cells (NPCs) and induced Astrocytes (iAs)

Both Ctrl2-SV4F-1 and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSC lines underwent differentiation into Neural Progenitor Cells (NPCs) following an adapted protocol as described previously described [

43] and following the supplier’s instructions. We implemented a rigorous standardization of iPSCs reprogramming and differentiation. Both cell lines matched for time in culture and passages. Cells plating densities were optimized to prevent potential alterations due to local growth factors. A panel of cell markers was used to assess cell types along the differentiation pathway, and the quality of cultures was monitored by evaluating cellular functionality.

Briefly, iPSCs were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells per well in Matrigel-coated 6-well plates (Corning) using mTesR plus (STEMCell Technologies) containing 10μM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (STEMCell Technologies). On day 3, the medium was switched to STEMdiffTM SMADi Neuronal Induction Kit (STEMCell Technologies) and refreshed daily. By day 8, the cells were replated at a density of 250,000 cells/cm2 on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates. This process was repeated twice more. After the third passage, the culture medium was changed to STEMdiffTM Neural Progenitor Medium, with daily replacements. At this differentiation stage, cells were analyzed using RT-qPCR and immunofluorescence for expression of the NPCs markers SOX1, PAX6 and NES. Cell banks at this passage were cryopreserved in STEMdiffTM Neural Progenitor Freezing Medium, employing a slow freezing protocol (approximately 1°C/min reduction) according to the supplier’s guidelines.

For astrocyte differentiation, cryopreserved NPCs were thawed in Matrigel-coated 6-well plates. Once 80-90% confluence was reached, NPCs were harvested using AcutaseTM (Millipore) and plated at a density of 2 x 105 cells/cm2 in STEMdiffTM Astrocyte Differentiation Medium (STEMCell Technologies) in a Matrigel® (Corning) precoated 6-well plates. After seven days in culture, with daily medium changes, the first cell colony passage was performed. The cells were dissociated using AcutaseTM (Millipore) and seeded at 1.5 x 105 cells/cm2 in new Matrigel® treated 6-well plates (Corning). This process was repeated twice. From the second passage (day 14 of the differentiation process), the culture medium was changed every 48 hours. Following the third passage, the culture medium was switched to STEMdiffTM Astrocyte Maturation. After three further passages in STEMdiffTM Astrocyte Maturation, the developed cell line was characterized through confocal microscopy, RT-qPCR analysis of specific markers, and functional evaluation of glutamate transport. Additionally, expression analysis of proteins related to NKH pathology, serine-glycine-one-carbon metabolism, and metabolite measurement in the culture medium were conducted at this stage.

4.13. Glutamate Uptake

Glutamate transport was quantified using previously established methods [

44]. In brief, 2.5 x 10

5 iAs cells underwent preincubation with 0.5 ml of HEPES-buffered saline for 10 min, followed by incubation in 250 µL HEPES-buffered saline containing [U-

14C]-glutamate (0.1 pCi) for 15 min. Subsequently, cells were rinsed with 2 x 0.5 ml fresh HEPES-buffered saline (2-4°C) within 5 s and dissolved in 250 µL of 0.2 M NaOH. A 150 µL sample was placed in micro vials and measured for radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter. The collected data were normalized to the protein content measured through Bradford’s assay.

4.14. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance was obtained using a two-tailed Student t-test performed with the GraphPad Prism 6 program. Differences were considered significant at p values of *<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001. GraphPad Prism 6 program and BioRender were used for images.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: PRP, BP. Methodology: LAC, IBA, ER, MC, FGM. Investigation: LAC, IBA, FZ, ER. Resources: MU, BP. Data curation: PRP, IBA, RN. Formal analysis: LAC, PRP. Writing, reviewing, and editing: all authors. Supervision and funding acquisition: PRP and BP

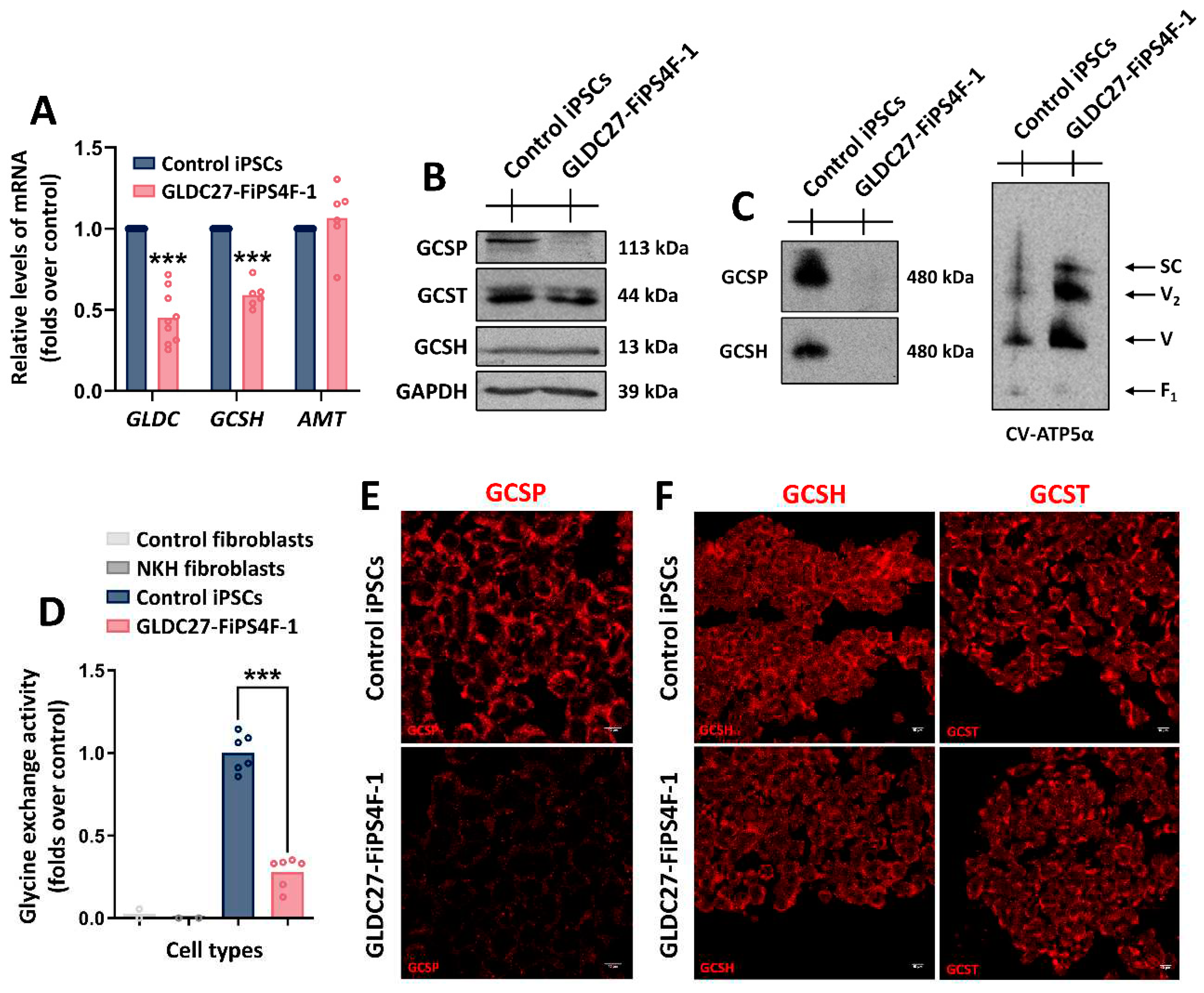

Figure 1.

GCS complex in the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line. (A) Relative quantification of GLDC, GCSH and AMT gene expression in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line related to control iPSCs. Standardization was performed using the endogenous ACTB gene. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative SDS-PAGE western blot of GCSP, GCSH, and GCST proteins in iPSCs lines. GAPDH was used as the loading control. (C) Supramolecular structure analysis using native gels under non-denaturing conditions and GCSP or GCSH antibodies. CV-ATP5α was used as the loading control. (D) Glycine exchange enzyme activity evaluation in control and NKH patient fibroblasts as well as in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs lines. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (E, F) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GCS complex proteins in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs. Scale bar: 10 μm. 40X magnification. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (A, D) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 1.

GCS complex in the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line. (A) Relative quantification of GLDC, GCSH and AMT gene expression in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line related to control iPSCs. Standardization was performed using the endogenous ACTB gene. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative SDS-PAGE western blot of GCSP, GCSH, and GCST proteins in iPSCs lines. GAPDH was used as the loading control. (C) Supramolecular structure analysis using native gels under non-denaturing conditions and GCSP or GCSH antibodies. CV-ATP5α was used as the loading control. (D) Glycine exchange enzyme activity evaluation in control and NKH patient fibroblasts as well as in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs lines. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (E, F) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GCS complex proteins in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs. Scale bar: 10 μm. 40X magnification. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (A, D) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

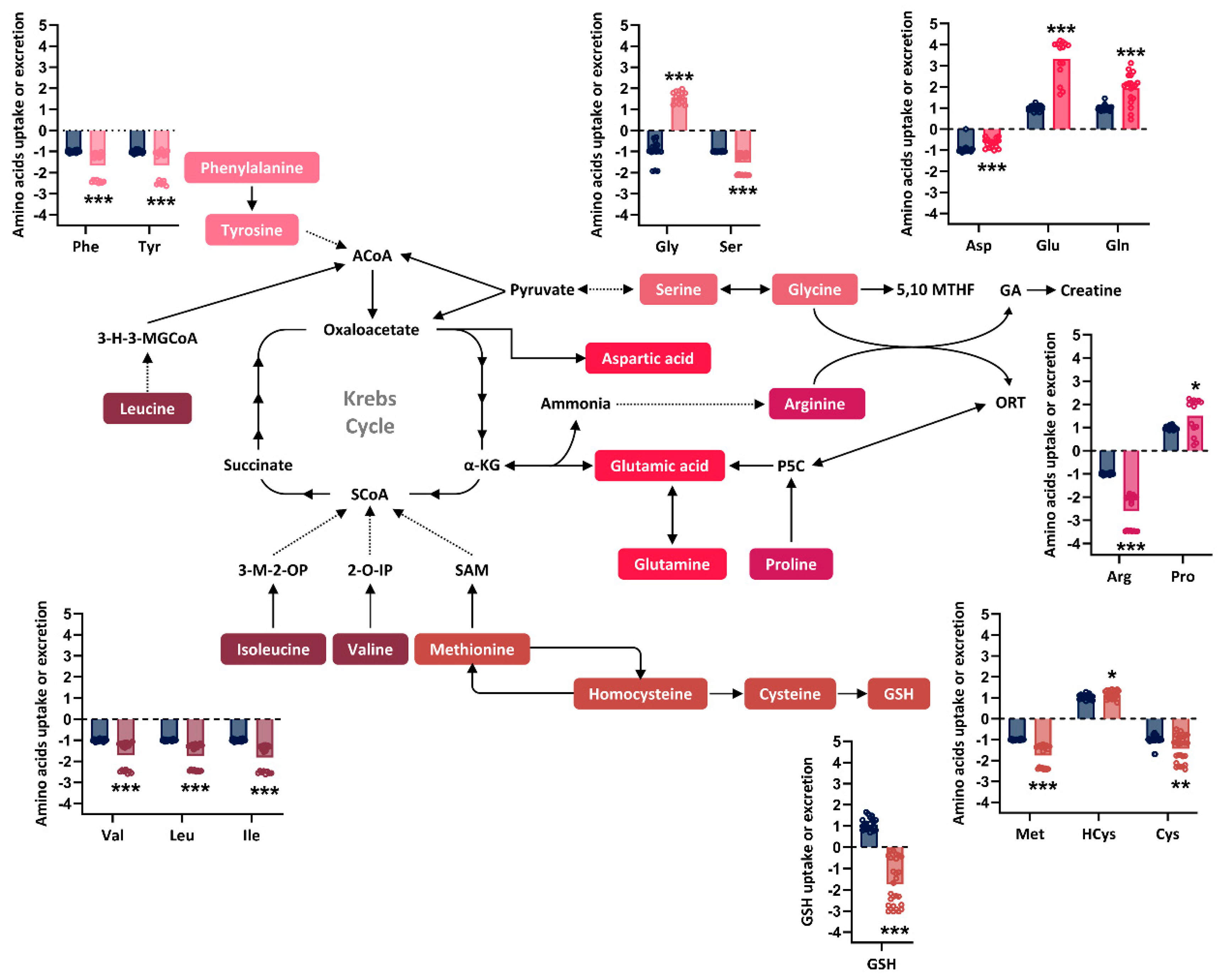

Figure 2.

Relative quantification of amino acids and GSH in the extracellular medium after 72 hours of culture. Simplified overview of amino acids metabolism in the cell. The colors represent different amino acid metabolic groups as defined by the KEGG platform (

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html#amino). Metabolite measurements were performed on n=20-30 samples in iPSCs lines that had undergone 3-6 passages post-thawing. The graphs illustrate the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line (different pink, red and brown shades) capacity for uptake or secretion of various metabolites compared to that of the control iPSCs line (blue). The control line is assigned a value of 1 or -1, indicating whether it (1) or absorbs (-1) the metabolite from the medium. The dotted line represents the 0 value. All values obtained in the measurement are normalized by protein. Baseline values of each metabolite in the medium were used to determine the iPSCs lines’ behavior (either uptake or secretion). Statistical analysis

t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). ACoA: acetyl-CoA; 3-H-3-MGCoA: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA; SCoA: succinyl-CoA; α-KG: α -ketoglutarate; 3-M-2-OP: 3-methyl-2-oxopentanoate; 2-O-IP: 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; 5,10 MTHF: 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; P5C: pyrroline-5-carboxylate; GA: guanidinoacetic acid; ORT: ornithine; GSH: glutathione.

Figure 2.

Relative quantification of amino acids and GSH in the extracellular medium after 72 hours of culture. Simplified overview of amino acids metabolism in the cell. The colors represent different amino acid metabolic groups as defined by the KEGG platform (

https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html#amino). Metabolite measurements were performed on n=20-30 samples in iPSCs lines that had undergone 3-6 passages post-thawing. The graphs illustrate the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 line (different pink, red and brown shades) capacity for uptake or secretion of various metabolites compared to that of the control iPSCs line (blue). The control line is assigned a value of 1 or -1, indicating whether it (1) or absorbs (-1) the metabolite from the medium. The dotted line represents the 0 value. All values obtained in the measurement are normalized by protein. Baseline values of each metabolite in the medium were used to determine the iPSCs lines’ behavior (either uptake or secretion). Statistical analysis

t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). ACoA: acetyl-CoA; 3-H-3-MGCoA: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA; SCoA: succinyl-CoA; α-KG: α -ketoglutarate; 3-M-2-OP: 3-methyl-2-oxopentanoate; 2-O-IP: 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine; 5,10 MTHF: 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; P5C: pyrroline-5-carboxylate; GA: guanidinoacetic acid; ORT: ornithine; GSH: glutathione.

Figure 3.

Serine-glycine-one-carbon metabolism. (A) Relative quantification by RT-qPCR of genes related to serine-glycine metabolism (PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, SHMT1, and SHMT2) and genes involved in one-carbon metabolism (folate cycle) (MTHFD1, MTHFD2, MTHFR, DHFR, and TYMS). Data were standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Data represent the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative western blot and protein quantification using GAPDH as loading control. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates. (A, B) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Serine-glycine-one-carbon metabolism. (A) Relative quantification by RT-qPCR of genes related to serine-glycine metabolism (PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, SHMT1, and SHMT2) and genes involved in one-carbon metabolism (folate cycle) (MTHFD1, MTHFD2, MTHFR, DHFR, and TYMS). Data were standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Data represent the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative western blot and protein quantification using GAPDH as loading control. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates. (A, B) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Nucleotide synthesis, viability, and cell cycle of iPSCs lines. (A) Relative quantification of intracellular purines and pyrimidines derivatives levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 extracts after 72 hours of culture. Nucleotide measurements were performed on n=17 iPSCs samples that had undergone 3-6 passes post-thawing. (B) Relative quantification of GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 cell density at three different platting densities compared to the control line measured after 72 hours of culture. (C) Analysis of cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry. On bars, percentages represent the fraction of cells in each cycle stage. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (D) Schematic representation and relative quantification of cyclin-coding genes and CDKs-coding genes expression involved in cell cycle regulation. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate and was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. (A-D) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Nucleotide synthesis, viability, and cell cycle of iPSCs lines. (A) Relative quantification of intracellular purines and pyrimidines derivatives levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 extracts after 72 hours of culture. Nucleotide measurements were performed on n=17 iPSCs samples that had undergone 3-6 passes post-thawing. (B) Relative quantification of GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 cell density at three different platting densities compared to the control line measured after 72 hours of culture. (C) Analysis of cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry. On bars, percentages represent the fraction of cells in each cycle stage. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (D) Schematic representation and relative quantification of cyclin-coding genes and CDKs-coding genes expression involved in cell cycle regulation. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate and was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. (A-D) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial function of GLDC27-FiPS4F-1. (A) Mitochondrial DNA depletion analysis by evaluation of 12S/18S and ND1/18S ratios measured by RT-PCR. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative SDS-PAGE western blot of OxPhos proteins using an antibody cocktail against different proteins of these complexes. (C) Mitochondrial respiration in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 compared to control iPSCs. Graphs represent the respiratory parameters derived from oxygen consumption (OCR). Rmax: Maximal Respiration; Spare: Spare Capacity; ATP-linked: ATP production. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates with measurements acquired 20 times. (D) Mitochondrial morphology analyzed by transmission electron microscopy in control (left panel) and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 (right panel) iPSCs. Mitochondria are indicated by black and white arrowheads. (A, C) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial function of GLDC27-FiPS4F-1. (A) Mitochondrial DNA depletion analysis by evaluation of 12S/18S and ND1/18S ratios measured by RT-PCR. Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate. (B) Representative SDS-PAGE western blot of OxPhos proteins using an antibody cocktail against different proteins of these complexes. (C) Mitochondrial respiration in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 compared to control iPSCs. Graphs represent the respiratory parameters derived from oxygen consumption (OCR). Rmax: Maximal Respiration; Spare: Spare Capacity; ATP-linked: ATP production. Data represents the average of n=3 biological replicates with measurements acquired 20 times. (D) Mitochondrial morphology analyzed by transmission electron microscopy in control (left panel) and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 (right panel) iPSCs. Mitochondria are indicated by black and white arrowheads. (A, C) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 6.

Characterization of the generated NPCs lines. (A) Schematic representation of characteristic markers in iPSCs differentiation to NPCs. (B, C) Relative gene expression of pluripotency markers (OCT3/4, LIN28B), early neuroepithelium markers (SOX1) and neuroepithelium and radial glia markers (PAX6, NES). Graphs show gene expression levels in both control (C) and GLDC-deficient (-) lines compared to iPSCs lines at days 0 (iPSCs) and 20 (NPCs) of differentiation. (D) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of PAX6, Nestin and OCT3/4 markers in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs. Dapi: Nuclear marker (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifications of 10X. (E) Representative western blot showing GCSP protein levels in NPCs cultures. “GLDC27-NPCs” refers to the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs line. (F) Representative images of NPCs cultures using phase contrast microscopy. (G) Relative gene expression levels of neural lineage markers in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs compared to control NPCs. (B, C, G) Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.00).

Figure 6.

Characterization of the generated NPCs lines. (A) Schematic representation of characteristic markers in iPSCs differentiation to NPCs. (B, C) Relative gene expression of pluripotency markers (OCT3/4, LIN28B), early neuroepithelium markers (SOX1) and neuroepithelium and radial glia markers (PAX6, NES). Graphs show gene expression levels in both control (C) and GLDC-deficient (-) lines compared to iPSCs lines at days 0 (iPSCs) and 20 (NPCs) of differentiation. (D) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of PAX6, Nestin and OCT3/4 markers in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs. Dapi: Nuclear marker (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. Magnifications of 10X. (E) Representative western blot showing GCSP protein levels in NPCs cultures. “GLDC27-NPCs” refers to the GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs line. (F) Representative images of NPCs cultures using phase contrast microscopy. (G) Relative gene expression levels of neural lineage markers in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 NPCs compared to control NPCs. (B, C, G) Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.00).

Figure 7.

Characterization of the generated iAs cultures. (A) Schematic diagram showing the differentiation stages of various cell types derived from neuroepithelial cells and the respective markers expressed in each stage (B) Relative quantification of radial glia markers (PAX6 and VIM) and (C) astrocyte markers (GFAP, S100β, APOE and AQP4) gene expression. (B, C) Graphs show gene expression levels of these markers in both control (C) and GLDC-deficient (-) iAs cultures compared to NPCs lines. (D) Relative quantification of astrocyte markers (GFAP, S100β, APOE, AQP4 and ALDH1L1) expression levels in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs related to control iAs. (E, F) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GFAP and S100β markers. Dapi: Nuclear staining (blue). (E) Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnifications of 40X. (F) Scale bar: 100 μm. Magnifications of 25X. (B, C, D) Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate and was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 7.

Characterization of the generated iAs cultures. (A) Schematic diagram showing the differentiation stages of various cell types derived from neuroepithelial cells and the respective markers expressed in each stage (B) Relative quantification of radial glia markers (PAX6 and VIM) and (C) astrocyte markers (GFAP, S100β, APOE and AQP4) gene expression. (B, C) Graphs show gene expression levels of these markers in both control (C) and GLDC-deficient (-) iAs cultures compared to NPCs lines. (D) Relative quantification of astrocyte markers (GFAP, S100β, APOE, AQP4 and ALDH1L1) expression levels in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs related to control iAs. (E, F) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GFAP and S100β markers. Dapi: Nuclear staining (blue). (E) Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnifications of 40X. (F) Scale bar: 100 μm. Magnifications of 25X. (B, C, D) Data represents the average of n=2 biological replicates conducted in triplicate and was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

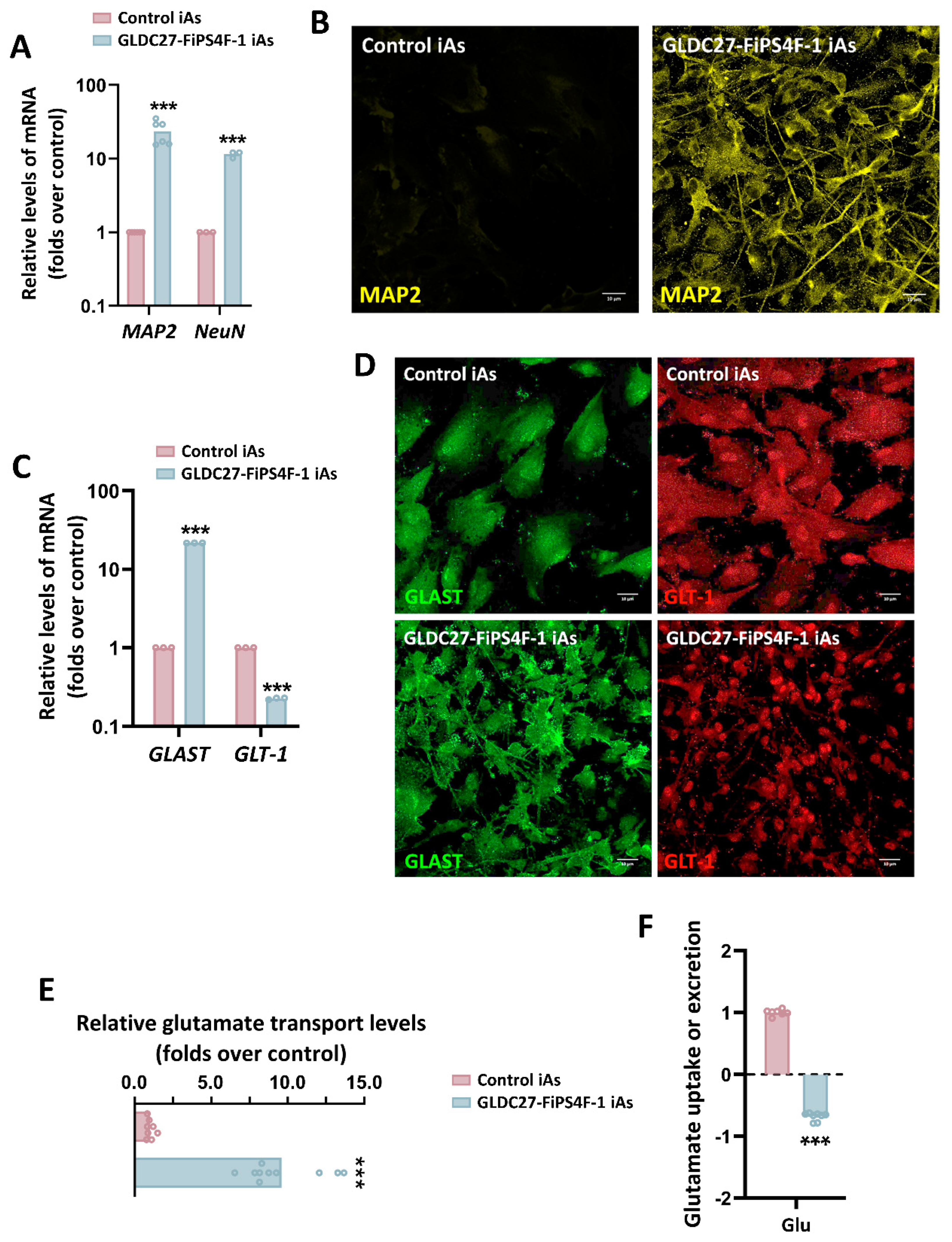

Figure 8.

Presence of mature neurons and functional analysis of the iAs cultures. (A) Relative quantification of mature neuron markers MAP2 and NeuN gene expression levels in GLDC-deficient iAs compared to control iAs. (B) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of neuronal marker MAP2 in both iAs cultures. (C) Relative gene expression levels of GLAST and GLT-1 in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs related to control iAs. (D) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GLAST and GLT-1 markers in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs cultures. (E) Radiolabeled glutamate transport measurement in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs compared to control iAs. Data were evaluated in two complete differentiation processes by quintuplicate. (F) Relative quantification of glutamate extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs after 72 hours of culture. Control iAs were assigned a value of 1. The dotted line represents the 0 value. All values obtained in the measurement were normalized by protein content. A total of n=10 samples were evaluated. (A, C) Data was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Data were analyzed in triplicate (B, D) Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnifications of 40X. (A, C, E, F) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 8.

Presence of mature neurons and functional analysis of the iAs cultures. (A) Relative quantification of mature neuron markers MAP2 and NeuN gene expression levels in GLDC-deficient iAs compared to control iAs. (B) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of neuronal marker MAP2 in both iAs cultures. (C) Relative gene expression levels of GLAST and GLT-1 in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs related to control iAs. (D) Immunofluorescence staining and laser scanning confocal imaging of GLAST and GLT-1 markers in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs cultures. (E) Radiolabeled glutamate transport measurement in GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs compared to control iAs. Data were evaluated in two complete differentiation processes by quintuplicate. (F) Relative quantification of glutamate extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs after 72 hours of culture. Control iAs were assigned a value of 1. The dotted line represents the 0 value. All values obtained in the measurement were normalized by protein content. A total of n=10 samples were evaluated. (A, C) Data was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene. Data were analyzed in triplicate (B, D) Scale bar: 10 μm. Magnifications of 40X. (A, C, E, F) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

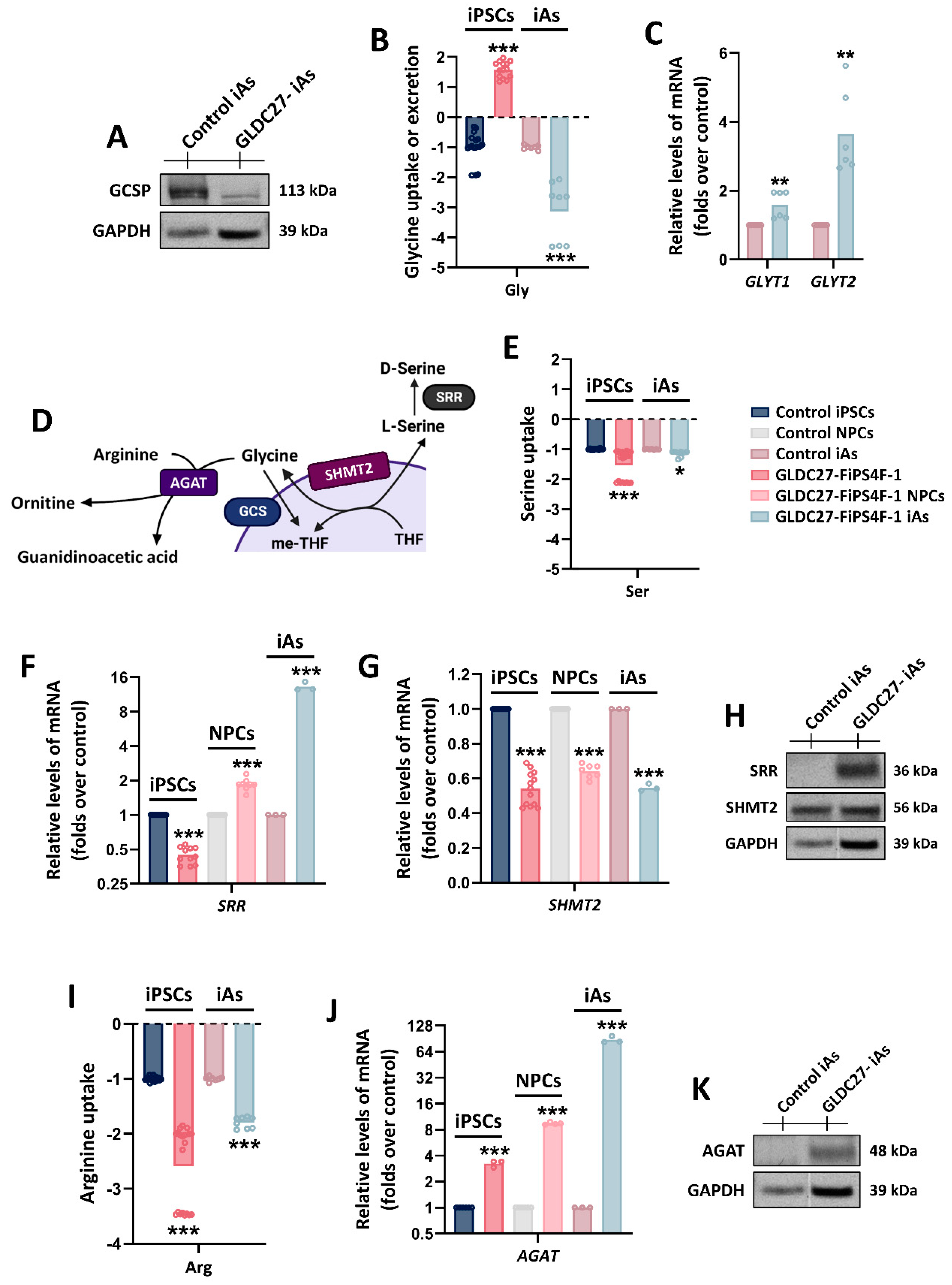

Figure 9.

Glycine homeostasis in GLDC-deficient iAs culture. (A) Representative western blot showing GCSP protein levels in iAs cultures. (B) Relative quantification of glycine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs and iAs after 72 hours of culture. (C) GLYT1 and GLYT2 gene expression levels (involved in glycine transport) in GLDC-deficient iAs related to control iAs. (D) Schematic representation of SHMT2, SRR and AGAT enzymes involvement in serine and creatine metabolism which are closely related to glycine. (E) Relative quantification of serine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSC lines and iAs cultures after 72 hours of culture. (F) Relative quantification of SRR and (G) SHMT2 genes in GLDC-deficient iPSCs, NPCs and iAs compared to control. (H) Representative western blot of SHMT2 and SRR proteins. (I) Relative quantification of arginine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs and iAs after 72 hours of culture. (J) Relative quantification of AGAT gene in GLDC-deficient iPSCs, NPCs and iAs compared to control line. (K) AGAT protein levels in iAs cultures. (A, H, K) GAPDH was used as loading control. “GLDC27-iAs” refers to GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs culture. (B, E, I) Control iPSCs and iAs were given a value of -1. The dotted line represents the 0 value. Positive levels represented a release of the metabolite into the medium while negative levels rendered an uptake from it. All values obtained in the measurement are normalized by protein. A total of n=10 samples were evaluated. (C, F, G, J) Data was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene and analyzed in triplicate. (B, C, E, F, G, I, J) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).

Figure 9.

Glycine homeostasis in GLDC-deficient iAs culture. (A) Representative western blot showing GCSP protein levels in iAs cultures. (B) Relative quantification of glycine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs and iAs after 72 hours of culture. (C) GLYT1 and GLYT2 gene expression levels (involved in glycine transport) in GLDC-deficient iAs related to control iAs. (D) Schematic representation of SHMT2, SRR and AGAT enzymes involvement in serine and creatine metabolism which are closely related to glycine. (E) Relative quantification of serine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSC lines and iAs cultures after 72 hours of culture. (F) Relative quantification of SRR and (G) SHMT2 genes in GLDC-deficient iPSCs, NPCs and iAs compared to control. (H) Representative western blot of SHMT2 and SRR proteins. (I) Relative quantification of arginine extracellular levels in control and GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iPSCs and iAs after 72 hours of culture. (J) Relative quantification of AGAT gene in GLDC-deficient iPSCs, NPCs and iAs compared to control line. (K) AGAT protein levels in iAs cultures. (A, H, K) GAPDH was used as loading control. “GLDC27-iAs” refers to GLDC27-FiPS4F-1 iAs culture. (B, E, I) Control iPSCs and iAs were given a value of -1. The dotted line represents the 0 value. Positive levels represented a release of the metabolite into the medium while negative levels rendered an uptake from it. All values obtained in the measurement are normalized by protein. A total of n=10 samples were evaluated. (C, F, G, J) Data was standardized against the endogenous ACTB gene and analyzed in triplicate. (B, C, E, F, G, I, J) Statistical analysis t student (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001).