1. Introduction

Diarrhoea is the leading cause of death among children less than 5 years of age [

1]. In Africa, viral agents tend to be the major etiology of diarrhoeal diseases [

2]. A variety of etiological agents mainly viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and parasites are responsible for these diarrhoea episodes (Bivins et al., 2017). In Africa, viral agents tend to be the major etiology of diarrhoeal diseases [

2]. Human norovirus is associated with 18% (95% Cl: 17-20%) of diarrhoeal diseases [

3,

4] and is one of the major causes of acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Noroviruses have been associated with the hospitalization of children with acute gastroenteritis with the highest burden in children under five years of age [15]. Noroviruses have different strains that can easily cause diverse mixed infections. Norovirus GII is the most predominant genogroup usually detected among children with norovirus diarrhoea and cause more than 70% of norovirus outbreaks worldwide [11,12]. Globally, the Gll.4 genotype is associated with the majority of norovirus outbreaks since the 1990s [13,14]. Formerly norovirus genotyping has been based on the typing of the capsid region of ORF2. However, due to norovirus frequent recombination mostly at ORF1 and ORF2 junction presently many researchers use both the capsid region of ORF2 and the polymerase region of ORF1 to identify norovirus genotypes [

9]. The norovirus genome is organized into 3 open reading frames (ORFs) as shown in Figure 4: open reading frame 1 (ORF1), open reading frame 2 (ORF2), and open reading frame 3 (ORF3). The ORF1 encodes for non-structural proteins, ORF2 encodes for the major protein (VP1) and ORF3 encodes for the minor protein VP2 [28]. ORF 1 and 2 contain regions A-E that are used for norovirus genotypingDifferent assays using specific primers are found to have different sensitivities for different norovirus genotypes [

10]. The norovirus genome is organized into 3 open reading frames (ORFs) as shown in Figure 4: open reading frame 1 (ORF1), open reading frame 2 (ORF2), and open reading frame 3 (ORF3). The ORF1 encodes for non-structural proteins, ORF2 encodes for the major protein (VP1) and ORF3 encodes for the minor protein VP2 (Kluwer et al.,2013). ORF 1 and 2 contain regions A-E that are used for norovirus genotyping

The findings from GEMS showed that the main contributors to MSD were rotavirus, Cryptosporidium, Shigella, and heat stable Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli (ST-ETEC) [

7] in three countries in South-East Asia (Bangladesh, Pakistan and India) and four countries in Africa (The Gambia, Mali, Mozambique and Kenya) that were studied. The GEMS data from The Gambia reported that norovirus was the third common cause of diarrhoea (Rotavirus-3.2%, Cryptosporidium 1.6%, Norovirus 1.2%, Shigella-4.0%, Adenovirus-2.3%, and ST-ETEC-0.7%) and the detection of both norovirus Gl and Gll genogroups with Gll as the most predominant genogroup [29]. Furthermore, GEMS reanalysis showed that norovirus Gll was more prevalent in The Gambia compared to all the other African countries included in GEMS study sites [29].

Enteric viruses are considered the most significant etiological agents of acute gastroenteritis accounting for approximately 70% of all gastroenteritis episodes (El Qazoui et al., 2014). In Africa, viral agents tend to be the major etiology of diarrhoeal diseases and four viruses are associated with acute gastroenteritis (rotaviruses, noroviruses, astroviruses, and adenoviruses) (Harris et al., 2017). Human norovirus is associated with 18% (95% Cl: 17-20%) of diarrhoeal diseases [3&4] and is one of the major causes of acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide [5,6,7&8]. However, due to norovirus frequent recombination mostly at ORF1 and ORF2 junction presently many researchers use both the capsid region of ORF2 and the polymerase region of ORF1 to identify norovirus genotypes [

9]. Different assays using specific primers are found to have different sensitivities for different norovirus genotypes [

10]. Norovirus GII is the most predominant genogroup usually detected among children with norovirus diarrhoea and cause more than 70% of norovirus outbreaks worldwide [

11,

12]. Globally, the Gll.4 genotype is associated with the majority of norovirus outbreaks since the 1990s [

13,

14]. Formerly norovirus genotyping has been based on the typing of the capsid region of ORF2. Noroviruses have been associated with the hospitalization of children with acute gastroenteritis with the highest burden in children under five years of age [

15] Noroviruses consists of various genogroups, genotypes and variants that can simultaneously infect a host.

2. Rationale

Seroprevalence study conducted in some African countries have indicated widespread of norovirus infection in young children [

16]. The GEMS study conducted in 7 sites in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia provided some estimates of the incidence of norovirus infection in young children with moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) [

17]. The GEMS study has shown that, in The Gambia, norovirus GII was the third most common cause of MSD in young children [

18] and were more prevalent in the Gambia compared to the other African countries.

The study is expected to provide data on the distribution of norovirus genogroups, genotypes, and variants in Gambian children that may inform vaccine choice and vaccine development as well as decision making for control measures. The aim of the study was to determine the genetic diversity of norovirus genogroups, circulating genotypes, and variants among Gambian children with gastroenteritis. The objectives were to describe the most common norovirus genotypes associated with MSD among Gambian children and to compare the frequency of circulating norovirus genotype among children with and without Moderate to severe diarrhea by age.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Study Site and Subjects

Between 2007 and 2012, the Global Enteric Multicentre Study (GEMS) was conducted in The Gambia [

19]. The study was conducted in Basse which is one of the six regions of the country. In the GEMS study, children who sought assistance from sentinel health centers with moderate to severe diarrhoea (MSD) between 2007 to 2012) were enrolled in the study as cases [

20]. Community controls, matched by age and gender, were selected from the population list generated by the demographic surveillance in the study site. A total of 240 archived stool samples that were previously tested positive for norovirus were taken from the GEMS for this study. To ascertain the positivity of these samples, the identified samples were retested, and results compared. Total RNA from all the 240 stool samples were tested by RTPCR to confirm norovirus positivity.

3.2. Detection of Norovirus Genogroups

Samples were screened by using two sets of primers, one targeting the Novovirus GI and another targeting Norovirus GII (

Table 1). Both primer set amplified the capsid and RNA dependent RNA polymerase regions of the norovirus genome. The reverse transcription was performed to produce first-strand DNA using a master mix according to previous work [

21]. A total of 68 samples were confirmed norovirus positive and the concentration of the extracted RNA were determined using the Qubit fluorometer.

3.3. Genomics Ribosomal Depletion and Library Preparation for Sequencing

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) forms about 80-90% of total RNA samples. Total RNA extracted from stool samples using the Qiagen QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (52906) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The RNA extracts were subsequently quantified using the high sensitivity dsDNA qubit kit and the quality assessed using the Agilent Tape station 4200. All the samples had an RNA integrity score (RINe) between the range of 1 to 5. The quantified samples were subjected to ribosomal RNA depletion using the riboMinus transcription isolation kit (Thermofisher), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.4. Purification of Ribosomal Depleted RNA, RNA Quality Check and RNA Fragmentation

The ribosomal depleted RNA were purified using the RNA Clean XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and normalized to 10ng in 10ul of nuclease free water. The normalized samples were fragmented using Covaris and library prepared using the NEBNext

® Ultra™ II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina

® (E7770L). The purified products were PCR enriched and quantified using high sensitivity dsDNA qubit kit and sized using High Sensitivity D1000 Screen Tape on the Agilent Tape station 4200. The digested ligated fragments were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter A63881) according to the NEBNext

® Ultra™ II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina

® protocol (E7770L) (New England Biolabs, UK). The pool was run at a final concentration of 1.8pM on an Illumina NextSeq550 instrument using NextSeq V2.5 reagent kit 150 cycles following the Illumina recommended denaturation and loading recommendations which included the use of 0.2N sodium hydroxide, 200mM Tris-HCL and 1% PhiX spike in (PhiX Control v3 Illumina Catalogue FC-110-3001). The final pool was quantified on a Qubit 3.0 instrument and BioRad CFX96 real-time instrument using the Roche KAPA library quantification for Illumina chemistry and run on a High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Catalogue No.5067-5579) using the Agilent Tapestation 4200. Data was uploaded to Basespace (

www.basespace.illumina.com) where the raw data was converted to FASTQ files for each sample.

3.5. Norovirus Sequence Analysis

Whole genome metagenomics sequencing was performed on all the 68 samples using the Next Seq sequencing machine operating on the Illumina platform. Raw FASTQ files were generated with a minimum coverage depth of 30x. FASTQC (v0.11.5) was used to check the quality of reads where a Phred score below 20 was trimmed off using Trimommatic (v0.39). To determine the number of sequences generated for norovirus in each sample, we used Kraken database (0.10.5beta). Quality trimmed reads were then mapped to the norovirus reference genome (NCBI Reference Sequences for Norovirus Gll MH218685.1, Gl NC_001959.2 and GlV NC_029647.1 complete genome). Reads that mapped to the reference genome were extracted and assembled into contigs using Velvet (1.2.10).

3.6. Primary Norovirus Sequence Analysis

The FastQ files generated by sequencing were quality controlled to check the quality of the cluster sequences obtained (reads) using the fastQC tool and QC scores below 20 were not considered.

de novo assembly of the reads was done using Spades algorithm [

22] to generate nucleotide contigs in FASTA files. The FASTA files of the samples were finally loaded into the Norovirus genotyping tool (Noronet norovirus typing tool version 2.0 and version 3.6) to determine the genotype based on the VP1 capsid sequence of ORF2 and the RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) sequence of the ORF1 of the norovirus genome.

The frequencies and percentages of all norovirus positives in both cases and controls were analysed using STATA (Fisher’s Exact Test). The distribution of norovirus genogroups, genotypes, and Gll.4 variants by gender and age group were also analyzed using STATA (Fisher’s Exact Test). Both crude and adjusted odds ratios including P-values were also analyzed using STATA (Logistic regression modelling). All the nucleotide sequences were translated to protein amino acid files using ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portal).

3.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of the segment of the sample’s genome sequences of the various genotypes was carried out with the aid of the Clustal Omega and Prank tools for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction using the maximum likelihood method. Briefly, sample sequences were submitted to the Clustal Omega and Prank software for analysis . After the analysis, the phylogeny tree text files were imported or pasted to Itol software to view and annotate the tree with Metadata.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmation of the Study Samples

A total of 240 norovirus positive stool samples (Case 121 and Controls 119) from archived diarrhoea stool samples collected during the GEMS were re-tested for norovirus positivity by RT-PCR. Sixty-eight (28.3%) of the samples (Cases 37 and Controls 31) were confirmed norovirus positive by RT-PCR of which 62% (42/68,) belonged to Norovirus genogroup ll (Gll), 37% (25/68) to norovirus genogroup1 and a single co-infection of Gl/Gll was identified. Age group-specific analysis for the prevalence of norovirus among children with diarrhea (cases) and healthy children (control) in the Gambia has revealed that norovirus detection was highest in toddlers (0-11mths) 55% followed by children (12-23mths) 35% and age (24-59mths) 10%. The detection of norovirus by age stratum has shown norovirus detection slightly more in the controls among the age group (0-11mths), detection of cases was more in cases among the age group (12-23mths) and among the age group (24-59mths) the detection of norovirus in both control and cases were similar. A higher prevalence of norovirus Gll amongst the 0-11months, 12-23 months and 24-59 months age groups was 62%, 44% and 16% respectively.

4.2. Frequency of Norovirus Detection in Cases and Controls among Stratified Age Groups

Fourty two (42) samples were sequenced but 41 samples were successfully characterized into genogroups, genotypes, and Gll.4 variants. As a result, the prevalence of norovirus genotypes identified among cases and controls have shown that the prevalence of norovirus genotype was higher in the cases (23/41, 56.1%) compared to the controls 18/41, 43.9%). Age-specific prevalence of norovirus among cases and controls is shown in the (

table 1) below. Norovirus genotype Gll.4 was the most common genotype detected in both cases (39.1%) and controls (33.3%) (

figure 1). The prevalence of norovirus genotypes among the three age strata were almost the same in both cases and controls but, the prevalence of the genotypes in all age strata decreases with a decrease in age. The results from this study have shown that the prevalence of norovirus infection was more common in children aged 0-11 months followed by children aged 12-23 months (

Table 2).

4.3. Norovirus Genogroup Distribution by Season

The Gambia has a tropical climate with two main seasons: dry season/harmattan (November-May) and rainy/wet season (June-October). The findings of this study have shown that the total number of the samples confirmed as norovirus positive (68), and the majority were collected during the dry season 60%(41/68) compared to the samples collected during the wet season 40%. The two main norovirus genogroups (Gll&Gl) associated with diarrhoea in children were detected in both seasons but the frequency differed.

Out of the 41 samples successfully characterised, 19 samples were collected during the dry season and 17 samples during the wet seasons. Norovirus Gll detection was higher during both the dry season (Gll 19/24 (79%), and wet season 11/17 (65%). Children with diarrhoea (cases) were observed more in the dry season 24/41 (59%) than in the wet season 17/41 (41%)

4.4. Norovirus Genotyping

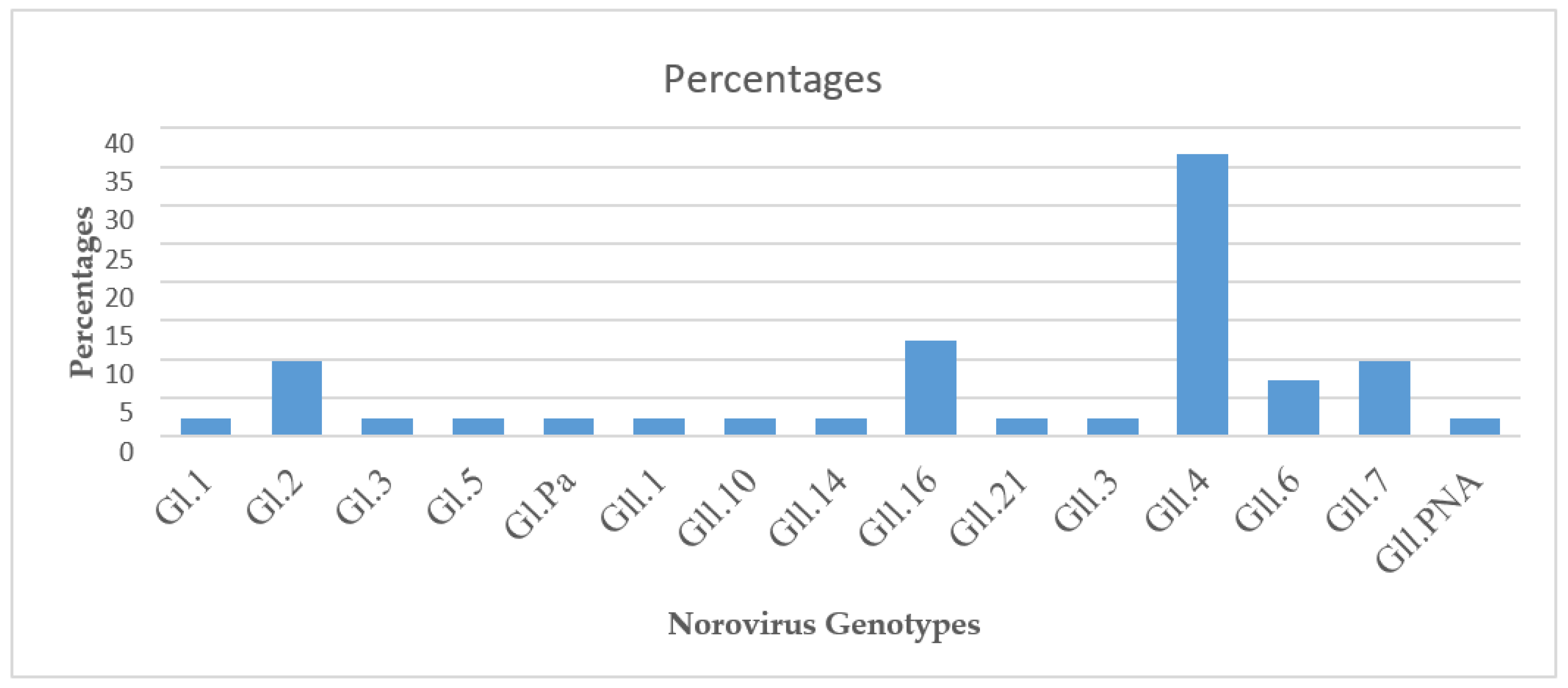

The detection of norovirus in this study showed the circulation of three main norovirus genogroups that infect humans (Gl, Gll, and GlV) as well as several norovirus genotypes but GlV could not be characterized using the Noronet genotyping software used in this study. Among the 68 norovirus positive samples sequenced, 41 samples were successfully characterized into genogroups, genotypes, and Gll.4 variants. Norovirus genotype Gll.4 8(42%) was the predominant genotype followed by Gll.16 5(26%) genotype among the capsid region of ORF2 genotypes (

Table 3). The Noronet genotyping results of the 41 samples revealed norovirus genogroup ll (Gll) 30/41 (73.1%) as the predominant norovirus genogroup circulating in The Gambia between 2007 and 2012 compared to norovirus genogroup1(Gl) 10/41(24.3%) and genogroup lV (GlV) 1/41 (2.4%). A total of 43 norovirus genotypes were identified from the 41 samples sequenced due to the detection of two norovirus genotypes from the same sample. Norovirus Gll.P7 4(50%) was the predominant norovirus genotype identified within the RdRp region of ORF1 genotypes and Gll.4, 11(69%) followed by Gl.2, 3(19%) as the predominant genotype identified in both RdRp and Capsid regions of the norovirus genome (

Table 3). From the analysis, 2.4% (n=1) of the total samples were characterized in the ORF1 (RdRp) region, 31.7% (n=13) of the samples in the ORF2 (capsid) region of the norovirus genome, 56.0% (n=23) of the samples by both ORF1 and ORF2 regions and 9.7% (n=4) sequences could not be assigned to any known genotype by the Noronet norovirus genotyping tool. The norovirus genotypes detected in this study were the same as the genotypes detected in some West African countries, mainly Ghana and Burkina Faso and also in South Africa (GII.P5, GII.P4, GI.P2, GII.4, GI.P3, GI.P6 and Gll.PNA) Mans et al.2016. Genotyping identified 15 norovirus Gl and Gll genotypes, with 5/15 (33%) identified as genogroup 1 (Gl) and10/15, (67%) identified as norovirus genogroup ll (Gll). The most predominant genotypes were (Gll.4) 18/44 (41%) followed by genotype Gll.16 5/44 (11.3%), genotype Gll.7 4/44 (9%), genotype Gl.2 4/44 (9%), genotype Gll.6 3/44 (7%) and the rest of the genotypes were only one genotype (

Figure 1).

Out of the 41 samples successfully genotyped, 23/41 (56%) were collected from children with diarrhoea (case), and 18/41 (44%) from healthy children (control). Seasonal (wet and dry season) distribution of the GII.4 variants showed that the two main Gll.4 variants detected were more during the dry season compared to the wet season. The majority of the Gll.4 variants were detected among children with diarrhoea cases (68%) than in healthy children, controls (32%) and the predominant variant among children with diarrhoea was Apeldoorn_2007. Among children with diarrhoea, Gll.4 9/23 (39%) was the most prevalent genotype identified. Out of the total Gll.4 genotypes, 14(74%) sequences were successfully identified in three unique Gll.4 variant groups: (Apeldoorn_2007, New_orleans_2009, and Osaka_2007) and 5(26%) sequences could not be assigned any Gll.4 variant. Among both cases and controls, norovirus genogroup Gll.4 was the most predominant (37%) compared to the rest of the other 14 individual norovirus genotypes identified in this study.

4.5. Summary Results of the Crude Odds Ratio and the Adjusted Attributable Odds Ratio for Norovirus Gll and Gl of Cases and Controls

Adjusted attributable Odds ratios were calculated for cases and controls in order to see whether the likelihood of the norovirus having is higher with those exposed (Cases) against those not exposed (Controls). This was to examine the likelihood of an outcome in relation to exposure.

Logistic regression modelling was performed using both crude and adjusted odds ratio analysis. Although norovirus Gll was the predominant norovirus genogroup detected among Gambian children <5 years of age, the logistic regression assays did not show association with either norovirus Gll or norovirus Gl genogroups (COR 4.03 Cl: 0.86, 18.85 P-value 0.077).

The crude and adjusted odds ratio analysis for age groups, gender and season to determine their association with norovirus positivity, did not shown any association of age, gender and season with norovirus Gl and Gll genogroups. These results demonstrated that, despite norovirus Gll being the predominant genogroup, it is not statistically associated with norovirus positivity compared to norovirus genogroup Gl and it may also be due to the small number of stool samples of the positive cases analyzed.

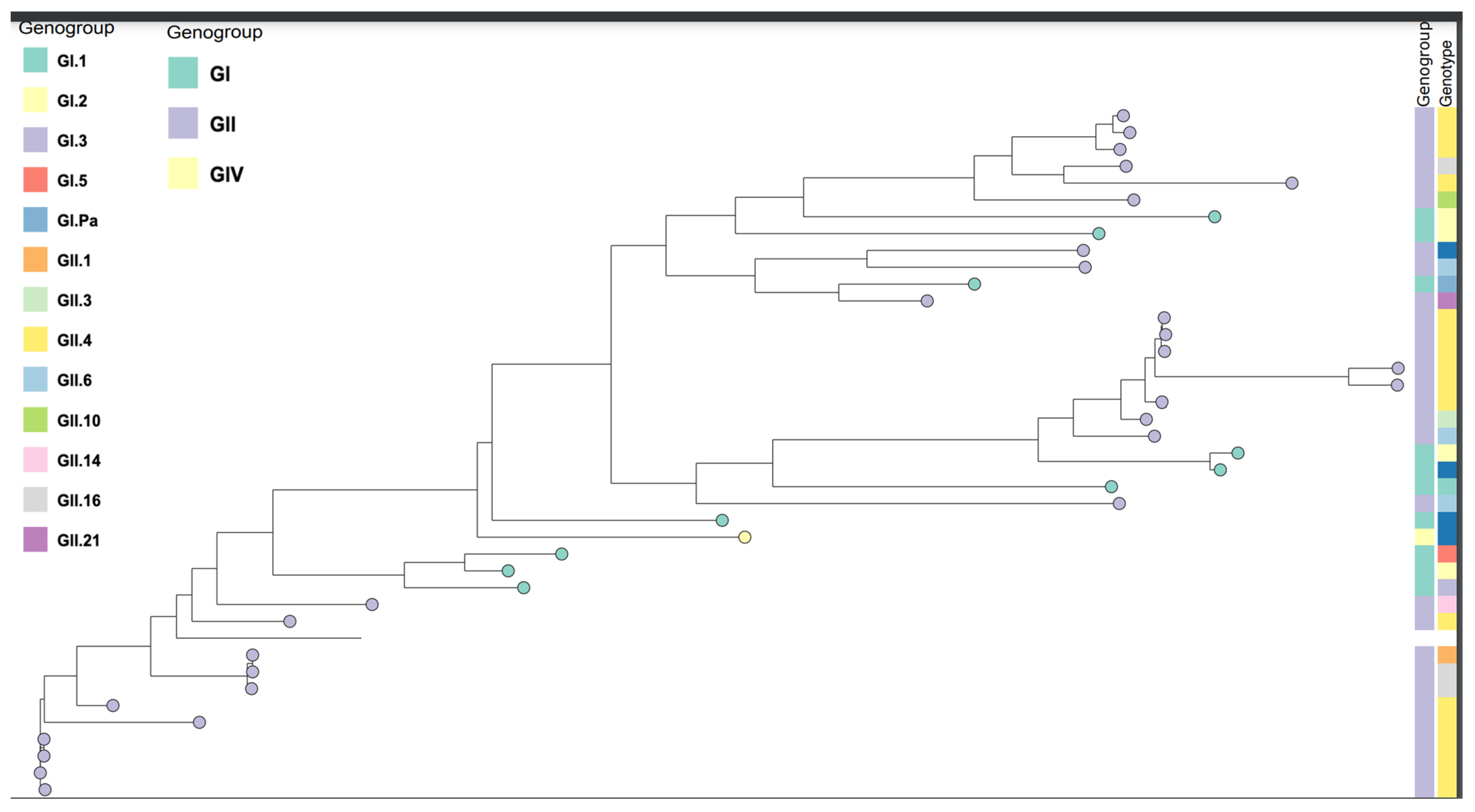

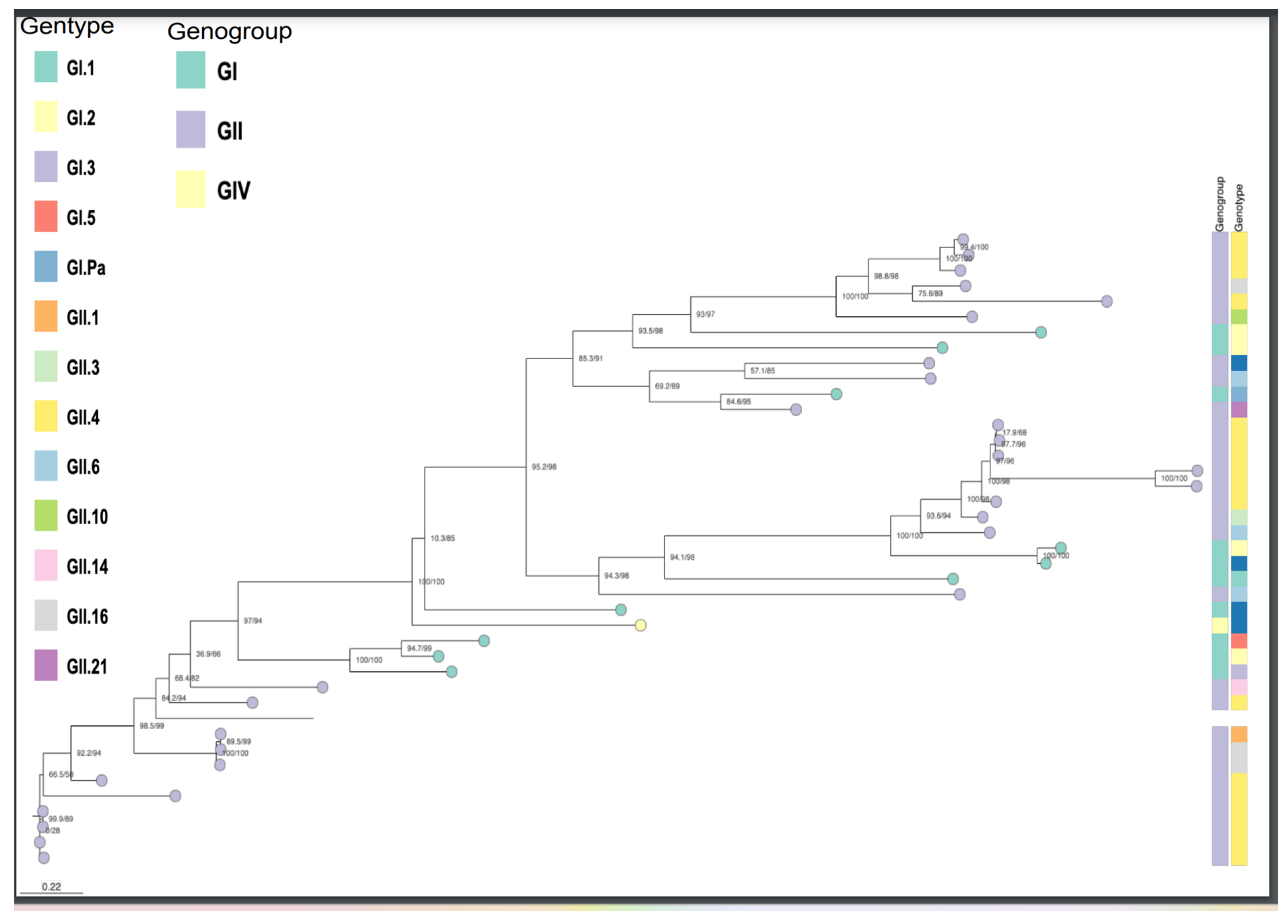

4.6. Phylogenetic Analysis of Norovirus Gl, Gll, GlV Strains Isolated

Phylogenetic analysis of the viral sequences clustered different norovirus genogroups (Gl, Gll &GlV) in three different clusters. Norovirus Gll was classified into four (4) clusters containing ten (10) different genotypes. The rest of the norovirus Gll (3/30, 10%) clustered with norovirus Gl, share common ancestors, and are closely related to Norovirus Gl. The majority of norovirus Gll (27/30, 90%) were found into two main clusters of, (13/27, 48%) and (14/27, 52%). Two of the samples have genotype Gll.4, variant New_orleans_2009, and genotype Gll.21. The likelihood that the sequences of Gl and Gll evolve from common ancestors was found in 27 norovirus Gll genogroups (27/30, 90%) and 9 norovirus Gl genogroup (9/10, 90%). Three of the norovirus Gll (3/30, 10%) sequences clustered with norovirus Gl and they share common ancestors (

Figure 2). The predominant Gll.4 variant (Apeldoorn_2007), has (5/9, 56%) sequence closely similar to each other. Sequence similarity of different norovirus genogroups, genotypes, and Gll.4 variants was determined. Apeldoorn_2007 variant has sequence similarity with variants New_Orleans_2009 and Gll.4 genotypes that could not be assigned to any variant. The three Gll samples that clustered with Gl could be different from the rest of the norovirus Gll identified in this study. Genogroups that could not be assigned any genotype have sequence similarity with genotype Gl.2, Gl.5, Gl.1, Gll.6, and Gl.3. They also have similar sequences to norovirus Gll, genotype Gll.P7/Gll.6 and share common ancestors with both Gl and Gll.

The predominant genotype identified among the Gl sequences was Gl.2 (4/41, 9.7%). There is one Gl sample that is closely related to norovirus Gll and has common ancestors with both Gl and Gll. Multiple sequence alignment showed similarity and differences between norovirus Gl, Gll, and GlV. In the phylogenetic tree analysis, 10 norovirus Gl sequences were analyzed and have presented a great diversity of three different clusters. Gll.4 which has been identified as the predominant genotype in this study, has (13/18, 72%) sequence similarity between individual genotypes. The different norovirus Gll and Gl genotypes detected in this study have shown a big sequence difference among the individual unique genotypes. The three samples were all collected during the wet season with two of the samples from the age group 12-23 months and one 0-11 months. Among the three clusters of Gl, one has a sub-cluster containing a single sample sequence. The samples in each of the Gll clusters have shown a high relationship in terms of age group, case/control, and the season the sample was collected. Sequence similarity was higher among sequences of individual genotypes but lower between the genogroups. This suggests that samples that clustered together share close genetic relationships and the norovirus samples included in this study showed wide diversity in their capsid and polymerase genes.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Capsid and RNA dependent RNA polymerase sequences. Norvirus genogroups, genotypes.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Capsid and RNA dependent RNA polymerase sequences. Norvirus genogroups, genotypes.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Capsid and RNA dependent RNA polymerase sequences. Norvirus genogroups, genotypes.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on the Capsid and RNA dependent RNA polymerase sequences. Norvirus genogroups, genotypes.

5. Discussions

The results generated from this research, revealed distinct and diverse norovirus genotypes based on the RdRp and Capsid regions including norovirus Gll.4 variants that circulated in the Upper River Region (URR) and part of the Central River Region (CRR) of The Gambia during the GEMS study period (2007-2012). Findings showed norovirus Gll.4 genotype as the predominant genotype detected in the samples that were sequenced. Therefore, the detection of norovirus variant (Apeldoorn_2007) as the predominant variant in The Gambia may be due to the dynamic nature of norovirus. The genotyping results revealed 41 genogroups and 16 unique sequence genotypes. The Noronet surveillance data 2005-2016, also showed variant Sydney 2012 as the predominantly detected norovirus variant worldwide since 2012 [

23]. The results of this study indicating norovirus Gll.4 genotype as predominant genotype form 2007-2012, differ from the discoveries of a novel Gll.17 as the predominant genotype in Asia [

24]. The results of this study has shown that variant Apeldoorn_2007 was the predominant Gll.4 variant detected among Gambian children (

Figure 2), differing from the findings in Africa by Makhaola and colleagues on the genetic and epidemiological analysis of norovirus in Botswana (2013-2015) which identified norovirus variant Sydney_2012 13(57%) and the predominant variant and a review by Mans and colleague on the norovirus epidemiology in Africa showing variants New_Orleans_2009 and Sydney 2012 as predominant variants in Africa from 1998-2013. It has also been observed in the UK by Karin Bok and colleague that variant Sydney 2012 was the predominant variant in UK in 2012 [

25]. Noroviruses are dynamic and predominant genotypes and variants could change easily. This finding is in line with the findings by Kreidieh and colleagues that showed norovirus Gll.4 as the predominant norovirus genotype detected in their systematic review on 16 studies conducted in Africa 64% [

26] and a review on norovirus epidemiology in Africa by Janet Mans and colleagues also identified norovirus genotype Gll.4 as the predominant genotype in most of the studies reviewed [

27]. The genotyping results of the nucleotide sequences revealed 16 distinct norovirus genotype sequences and Gll.4 variants among the three age groups of children included in the GEMS study. The norovirus genogroup 4 (GlV) detected in this study is a rare genogroup that is not usually found in diarrhoea disease investigation.

6. Conclusions and Study Limitations

The research identity the norovirus genotypes that circulated among Gambian children less than 5 years of age during 2007-2012 GEMS study and their relationship with other norovirus genotypes worldwide. Norovirus cases were predominantly confirmed to be norovirus genotype Gll.4. The number of samples confirmed norovirus positive by RT-PCR from the archived samples were only 68 norovirus positives cases. A further limitation was that the samples were genotyped using noronet database, norovirus genotyping tool which has limited available data on norovirus sequences in the database. Despite the limitations, this study shows a high proportion of norovirus genogroup ll (Gll), genotype Gll.4, and Gll.4 variant, Apeldoorn_2007 as the most predominant in this study. Norovirus Gll.4 evolves at faster rate than other noroviruses (evolutionary Dynamics) and it generates replacement clusters that constantly evade the immune response within the same genotype. The predominant of this genotype provides Imporatnt information that could be used for norovirus vaccine development, vaccine choice, and decision making on the prevention and control strategies of norovirus gastroenteritis which could have impact on Policy in The Gambia.

This is the first time to report detailed information on the norovirus genotypes in The Gambia. Continuous norovirus surveillance is necessary for the detection of the emerging strains and the provision of data for norovirus vaccine choice and preventive measures in The Gambia the major limitation of this study was that the number of stool samples confirmed positive was small. The number of stools samples confirmed positive from the available archived stool samples was small and could not power the study to show any statistical associations in the analysis. As a result, the findings of the study cannot be used to make any generalization

Funding Source

was supported by a WACCBIP-World Bank ACE Masters/PhD fellowship University of Ghana and The Gambia Government.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that or conflict of interest could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Approval

I got ethical approval from The Gambia Government and Medical Research council of The Gambia Joint Ethical Committee (SCC 1604v3.1).

References

- Chissaque, A., de Deus, N., Vubil, D., & Mandomando, I. (2018). The Epidemiology of Diarrhea in Children Under 5 Years of Age in Mozambique. In Current Tropical Medicine Reports (Vol. 5, Issue 3, pp. 115–124). Springer Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Kabue, J. P., Meader, E., Hunter, P. R., & Potgieter, N. (2016). Human Norovirus prevalence in Africa: a review of studies from 1990 to 2013. Trop Med Int Health, 21(1), 2-17. [CrossRef]

- Lopman, B. Norovirus, 3rd WHO Product Development for Vaccines,Advisory Committee Meeting (PDVAC), CDC, 2016.

- Armah, G. E., Gallimore, C. I., Binka, F. N., Asmah, R. H., Green, J., Ugoji, U., … Gray, J. J. (2006). Characterization of Norovirus Strains in Rural Ghanaian Children With Acute Diarrhoea, 1485(June), 1480–1485. [CrossRef]

- Ben Lopman, R. A., Ralph Baric, Mary Estes, Kim Green, Roger Glass. Global burden of norovirus and prospects for vaccine development, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015.

- Ahmed, S. M., Hall, A. J., Robinson, A. E., Verhoef, L., Premkumar, P., Parashar, U. D., … Lopman, B. A. (2014). The global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 14(8), 725–730. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K. L., Nataro, J. P., Blackwelder, W. C., Nasrin, D., Farag, T. H., Panchalingam, S., . . . Levine, M. M. (2013). Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 382(9888), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M. D., Pires, S. M., Black, R. E., Caipo, M., & Crump, J. A. (2015). World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial , Protozoal , and Viral Diseases , 2010 : A Data Synthesis, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Kroneman, A., Vega, E., Vennema, H., Vinje, J., White, P. A., Hansman, G., . . . Koopmans, M. (2013). Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol, 158(10), 2059-2068. [CrossRef]

- Damascena, L. (2018). Molecular epidemiology and temporal evolution of norovirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Amazonas state, Brazil Molecular epidemiology and temporal evolution of norovirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Amazonas state, Brazil, (April). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. G., Cho, H. G., & Paik, S. Y. (2015). Molecular epidemiology of norovirus in South Korea. In BMB Reports (Vol. 48, Issue 2, pp. 61–67). The Biochemical Society of the Republic of Korea. [CrossRef]

- Desai, R., Hembree, C. D., Handel, A., Matthews, J. E., Dickey, B. W., McDonald, S., . . . Lopman, B. (2012). Severe outcomes are associated with genogroup 2 genotype 4 norovirus outbreaks: a systematic literature review. Clin Infect Dis, 55(2), 189-193. [CrossRef]

- Lindesmith, L. C., Donaldson, E. F., & Baric, R. S. (2011). Norovirus GII.4 strain antigenic variation. J Virol, 85(1), 231-242. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K. L., Hewitt, J., Sitabkhan, A., Eden, J., Lun, J., Levy, A., … White, P. A. (2016). RESEARCH ARTICLE A Multi-Site Study of Norovirus Molecular Epidemiology in Australia and New Zealand, 2013-2014, 2013–2014. [CrossRef]

- Trang, N. Van, Vu, T., Le, T., Huang, P., Jiang, X., & Anh, D. (2014). Association between Norovirus and Rotavirus Infection and Histo- Blood Group Antigen Types in Vietnamese Children, 52(5), 1366–1374. [CrossRef]

- Smith TK, Bos P, Peenze I, Jiang X, Estes MK, Steele AD. Seroepidemiological study of genogroup I and II calicivirus infections in South and southern Africa. J Med Virol. 1999; 59:227–31. PMID:10459161. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K. L., Nataro, J. P., Blackwelder, W. C., Nasrin, D., Farag, T. H., Panchalingam, S., . . . Levine, M. M. (2013). Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 382(9888), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K. L., Nataro, J. P., Blackwelder, W. C., Nasrin, D., Farag, T. H., Panchalingam, S., . . . Levine, M. M. (2013). Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 382(9888), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K. L., Nataro, J. P., Blackwelder, W. C., Nasrin, D., Farag, T. H., Panchalingam, S., . . . Levine, M. M. (2013). Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 382(9888), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K. L., Nataro, J. P., Blackwelder, W. C., Nasrin, D., Farag, T. H., Panchalingam, S., . . . Levine, M. M. (2013). Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. The Lancet, 382(9888), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. P., Watson, M. A., Fankhauser, R. L., & Monroe, S. S. (2004). Genogroup I and II noroviruses detected in stool samples by real-time reverse transcription-PCR using highly degenerate universal primers. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70(12), 7179–7184. [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A., Nurk, S., Antipov, D., Gurevich, A. A., Dvorkin, M., Kulikov, A. S., . . . Pevzner, P. A. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol, 19(5), 455-477. [CrossRef]

- Beck-Friis, T., Sundell, N., Gustavsson, L., Lindh, M., Westin, J., & Andersson, L.-M. (2023). Outdoor Absolute Humidity Predicts the Start of Norovirus GII Epidemics. Microbiology Spectrum, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Yan, S., Li, B., Pan, Y., & Wang, Y. (2014). Genetic diversity and distribution of human norovirus in China (1999-2011). Biomed Res Int, 2014, 196169. [CrossRef]

- Bok, K., & Green, K. Y. (2012). Norovirus Gastroenteritis in Immunocompromised Patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(22), 2126–2132. [CrossRef]

- Kreidieh, K., Charide, R., Dbaibo, G., & Melhem, N. M. (2017). The epidemiology of Norovirus in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: A systematic review. In Virology Journal (Vol. 14, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mans, J., Armah, G. E., Steele, A. D., & Taylor, M. B. (2016). Norovirus Epidemiology in Africa: A Review. PLoS One, 11(4), e0146280. [CrossRef]

- El Qazoui, M., Oumzil, H., Baassi, L., El Omari, N., Sadki, K., Amzazi, S., . . . El Aouad, R. (2014). Rotavirus and norovirus infections among acute gastroenteritis children in Morocco. BMC Infect Dis, 14, 300. [CrossRef]

- Harris, V., Ali, A., Fuentes, S., Korpela, K., Kazi, M., Tate, J., … de Vos, W. M. (2017). Rotavirus vaccine response correlates with the infant gut microbiota composition in Pakistan. Gut Microbes, 0(0), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Wolters Kluwer, L. c. W., Wilkins. (2013). FIELD's VIROLOGY (Vol. volume one).

- Liu, J., Platts-mills, J. A., Juma, J., Kabir, F., Nkeze, J., Okoi, C., … Foundation, M. G. (2016). Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children : a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. The Lancet, 388(10051), 1291–1301. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).