Submitted:

19 January 2024

Posted:

22 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental materials and methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphology

3.2. XRD spectra

3.3. Hardness

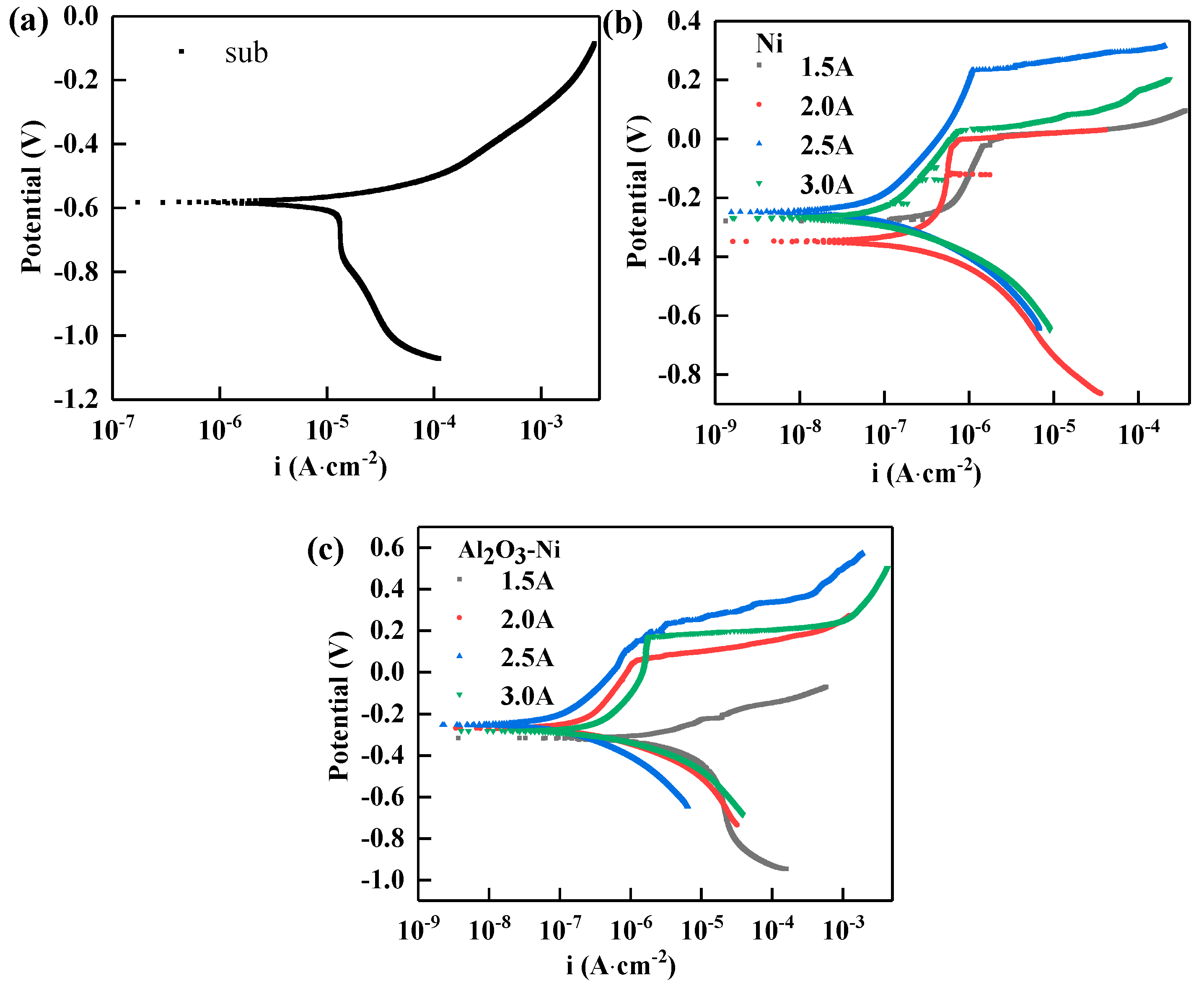

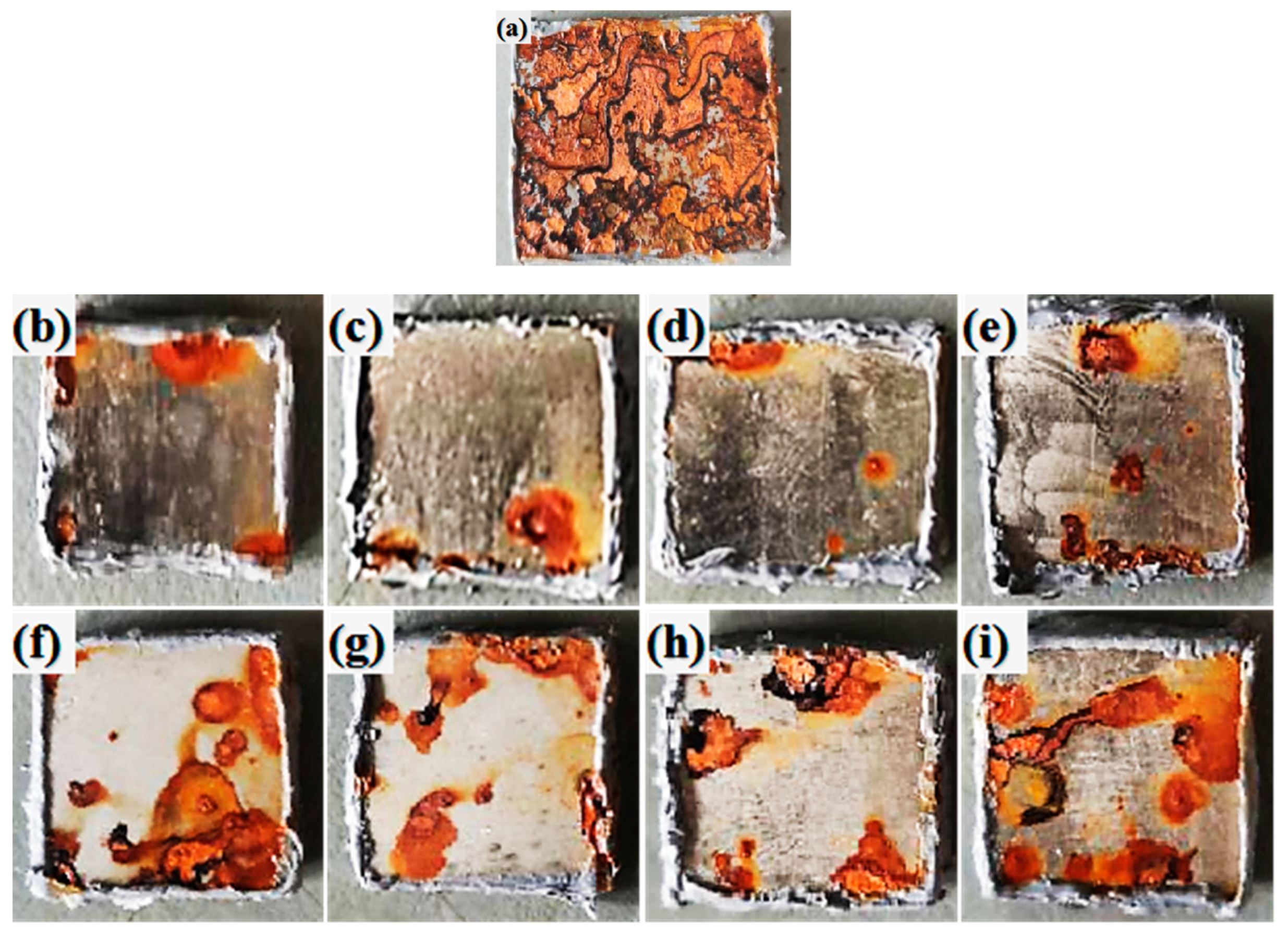

3.4 Corrosion resistance

4. Conclusion

Funding

References

- Pa, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.-L.; Kuo, C.-L.; Su, Y.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Lin, K.-J.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Hwang, W.-S. Effects of Rare Earth Metals on Steel Microstructures. Materials 2016, 9, 417. [Google Scholar]

- Gerengi, H.; Sahin, H.I. Schinopsis lorentzii Extract As a Green Corrosion Inhibitor for Low Carbon Steel in 1 M HCl Solution. Journal of Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 2012, 780–787. [Google Scholar]

- Bazant, Z.P. Physical model for steel corrosion in concrete sea structures—theory. Journal of Structural Divison 1979, 105, 1138–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Han, E.H.; Wang, Z. Effect of tannic acid on corrosion behavior of carbon steel in NaCl solution. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2019, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, J.G. Deterioration of concrete due to reinforcement steel corrosion. Cement & Concrete Composites 1996, 18, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shakoor, R.A.; Kahraman, R.; Waware, U.S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, W. Synthesis and properties of electrodeposited Ni–B–CeO2 composite coatings. Materials & Design 2014, 59, 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Yuxin; Wang; Xin; Shu; Shanghai; Wei; Chuming; Liu; Wei; Gao. Duplex Ni–P–ZrO2/Ni–P electroless coating on stainless steel. Journal of Alloys & Compounds 2015, 630, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, R.A.; Kahraman, R.; Waware, U.; Wang, Y.; Wei, G. Properties of electrodeposited Ni–B–Al2O3 composite coatings. Materials and Design 2014, 64, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, H.H.; Huang, P.C.; Tsai, L.C.; Hou, K.H. Effects of plating parameters on the Ni–P–Al2O3 composite coatings prepared by pulse and direct current plating. Surface & Coatings Technology 2013, 235, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, T.; Krishnaveni, K.; Seshadri, S.K. Electroless Ni–P/Ni–B duplex coatings: preparation and evaluation of microhardness, wear and corrosion resistance. Materials Chemistry & Physics 2003, 82, 771–779. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yan, G.; Liu, H.; Xue, Q.; Tao, X. Effects of bivalent Co ion on the co-deposition of nickel and nano-diamond particles. Surface & Coatings Technology 2005, 191, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N.K.; Masuko, M.; Saji, T. Composite plating of Ni/SiC using azo-cationic surfactants and wear resistance of coatings. Wear 2003, 254, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei; Wang; and; Feng-Yan; Hou; and; Hui; Wang; and; He-Tong. Fabrication and characterization of Ni–ZrO2 composite nano-coatings by pulse electrodeposition. Scripta Materialia 2005, 53, 613–618. [CrossRef]

- Alirezaei, S.; Monirvaghefi, S.M.; Saatchi, A.; ürgen, M.; Kazmanl?, K. Novel investigation on tribological properties of Ni–P–Ag–Al2O3 hybrid nanocomposite coatings. Tribology International 2013, 62, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.H.; Ding, H.Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y. Structure and Mechanical Properties of Ni-P-Nano Al_2O_3 Composite Coatings Synthesized by Electroless Plating. Journal of Iron and Steel Research International 2008, 15, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J. Effect of surfactant on the electrodeposition and wear resistance of Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2006, 434, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goral, A.; Beltowska-Lehman, E.; Indyka, P. Structure characterization of Ni/Al2O3 composite coatings prepared by electrodeposition. Solid State Phenomena 2010, 163, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, H.; Kılıc, F.; Aslan, S.; Alp, A.; Akbulut, H. Characteristics of electro-co-deposited Ni–Al2O3 nano-particle reinforced metal matrix composite (MMC) coatings. Wear 2009, 267, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygieł, B.; Kołodziej, M. Composite Ni/Al2O3 coatings and their corrosion resistance. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 50, 4188–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral; Anna. Nanoscale structural defects in electrodeposited Ni/Al 2 O 3 composite coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2017, 319, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Ramamoorthy, B. Effect of reducing agent and nano Al2O3 particles on the properties of electroless Ni–P coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 307, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Sawada, H.; Nan, W.; Jian, N. Preparation of Ni-P-Al2O3 Composite Film on Mild Steel with High Resistances to Corrosion and Wear. Materials ence Forum 2013, 750, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 胡佳宇; 陈金龙; 陈龙; 李少鹏; 黄登皓; 陈子昂; 陈华建; 谢文玲. 电镀电流密度对Al2O3-Ni复合镀层的耐蚀性影响. 广东化工 2023, 50, 24–26, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Gáliková, Z.; Chovancová, M.; Danielik, V. Properties of Ni-W alloy coatings on steel substrate. Chemical Papers 2006, 60, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziof, S.; Gao, W. The effect of pulse electroplating on Zn–Ni alloy and Zn–Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings. Journal of Alloys & Compounds 2015, 622, 918–924. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuo, K. Electrodeposited Co–Ni–Al2O3composite coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology 2004, 176, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J. Effect of surfactant on the electrodeposition and wear resistance of Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings. Materials Science and Engineering A 2006, 434, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q.; Li, T.; Yue, H.; Kai, Q.; Bai, F.; Jin, J. Preparation and characterization of nickel nano-Al 2O 3 composite coatings by sediment co-deposition. Applied Surface Science 2008, 254, 2262–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, Z.; Bahrololoom, M.E.; Hashemi, B. Electrodeposition of nanocrystalline Ni/Ni–Al2O3 nanocomposite modulated multilayer coatings. Materials & Design 2016, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, B.; Poplawski, K.; Oleszak, D.; Jezierska, E.; Sobiecki, J. Influence of stirring conditions on Ni/Al2O3nanocomposite coatings. Surface Engineering 2016, 32, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husen, J.; Qi, L.; Jin, W.; Xiaolian, W.; Peng, Z.; Shufeng, S. Effect of Substrate Hardness and Coating Thickness on the Hardness of AlCrN. Material Protection and Surface Engineering 2017, 38, 2401–2404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.M.; Wang, Y.; Han, T.; Wu, K.Y.; Xue, J. Electrochemical evaluation of corrosion resistance of NiCrBSi coatings deposited by HVOF. Surface & Coatings Technology 2004, 183, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.-J.; Ning, C.-M.; Shang, L.-L.; Zhang, G.-A.; Liu, X.-Q. Structure and anticorrosion, friction, and wear characteristics of Pure Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC), Cr-DLC, and Cr-H-DLC films on AZ91D Mg alloy. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2019, 28, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygie, B.; Ko?Odziej, M. Composite Ni/Al2O3 coatings and their corrosion resistance. Electrochimica Acta 2005, 50, 4188–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babak; Bakhit; Alireza; Akbari. Effect of particle size and co-deposition technique on hardness and corrosion properties of Ni–Co/SiC composite coating. Surface & Coatings Technology 2012, 206, 4964–4975. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wei, B.; Wu, Z.; Qi, Z.; Wang, Z. A comparative study on the corrosion behaviour of Al, Ti, Zr and Hf metallic coatings deposited on AZ91D magnesium alloys. Surface and Coatings Technology 2016, 303, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui; Xue-jun; Gong; Min; Liu; Chun-hai; Zheng; Xing-wen; Lin; Xiu-zhou. Fabrication and corrosion resistance of a hydrophobic micro-arc oxidation coating on AZ31 Mg alloy. Corrosion Science 2015, 90, 402–412. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, R.-q.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.-k.; Wang, D.-d.; Liu, X.-t.; Zhang, X.-z.; Wu, G.-r.; Shen, D.-j. The electrochemical corrosion behavior of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings fabricated on aluminum in silicate electrolyte. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2019, 28, 3652–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianqing, Z.; Chunan, C. Study and evai_uation on organic coatings by eijectrochemicai impedance spectroscopy. Corrosion and Protection 1998, 19(3), 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Cao, F.; Chang, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhanga, J.; Cao, C. The preparation and corrosion behaviors of MAO coating on AZ91D with rare earth conversion precursor film. Applied Surface Science 2011, 257, 3804–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAMMELT, U.; REINHARD*, G. On the applicability of a constant phase element (CPE) to the estimation of roughness of solid metal electrodes. Electrochimica Acta 1990, 35, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganatha, S.; Venkatesha, T.V.; Vathsala, K. Development of electroless Ni–Zn–P/nano-TiO 2 composite coatings and their properties. Applied Surface Science 2010, 256, 7377–7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compositions | Ni coatings | Ni-Al2O3 coatings |

|---|---|---|

| Ni2SO4·6H2O (g/L) | 26 | 26 |

| NiCl2·6H2O (g/L) | 23 | 23 |

| Boric acid (H3BO3) (g/L) | 30 | 30 |

| Alumina (Al2O3) (g/L) | 0 | 10 |

| Stabilizer | Balance | Balance |

| pH | 4.0-4.2 | 4.0-4.2 |

| Temperature (℃) | 40 | 40 |

| Stirring speed (rpm) | 300 | 300 |

| Current density (A/dm²) | 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 | 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 |

| Electrodeposition time (h) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Sample |

Ec (A/dm2) |

ba (mV/dec) |

-bc (mV/dec) |

icorr (A∙cm-2) |

Ecorr (V) |

Rp (kΩ∙cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | 44.98 | 67.01 | 4.36×10-6 | -0.584 | 2.68 | |

| Ni coated samples | 1.5 | 107.06 | 59.86 | 2.10×10-7 | -0.278 | 79.34 |

| 2.0 | 69.02 | 56.87 | 6.98×10-8 | -0.347 | 193.93 | |

| 2.5 | 88.29 | 71.66 | 2.74×10-8 | -0.245 | 626.99 | |

| 3.0 | 102.92 | 63.69 | 4.10×10-8 | -0.269 | 417.08 | |

| Ni-Al2O3 coated samples | 1.5 | 64.33 | 80.18 | 8.68×10-7 | -0.319 | 17.86 |

| 2.0 | 187.88 | 90.58 | 1.77×10-7 | -0.268 | 147.34 | |

| 2.5 | 166.42 | 95.87 | 5.20×10-8 | -0.254 | 508.22 | |

| 3.0 | 190.91 | 77.87 | 2.08×10-7 | -0.283 | 115.31 |

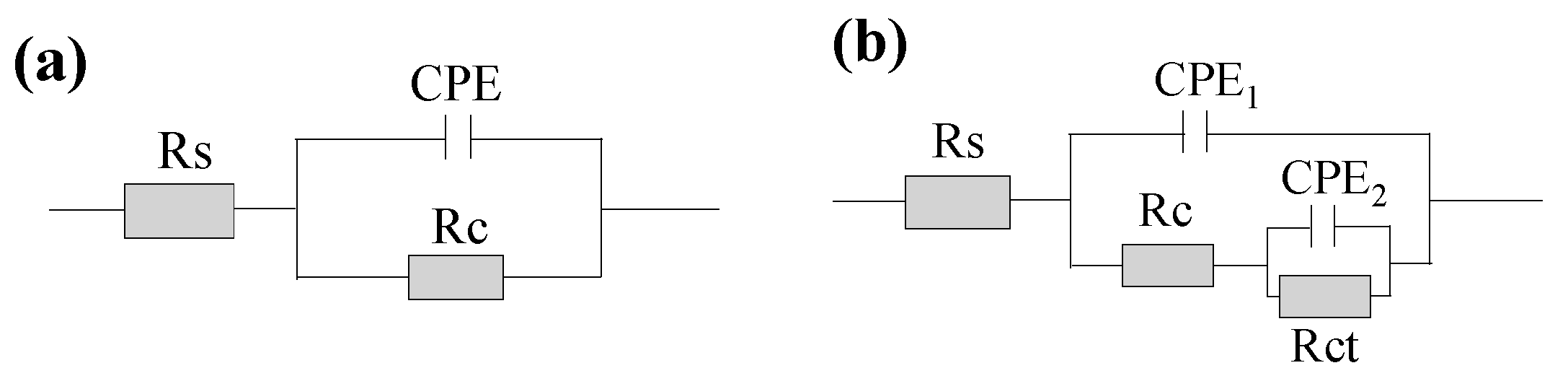

| coating |

Ec (A∙dm-2) |

Rs (Ω∙cm2) |

CPE1 (μF∙cm-2) |

Rc (kΩ∙cm2) |

CPE2 (μF∙cm-2) |

Rct (kΩ∙cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub | 11.42 | 4.56 | 1.48 | |||

| Ni | 1.5 | 10.36 | 3.25 | 1.01 | 2.33 | 1080 |

| 2.0 | 6.25 | 1.99 | 2.56 | 2.14 | 1320 | |

| 2.5 | 11.63 | 2.41 | 5.38 | 3.28 | 1410 | |

| 3.0 | 22.31 | 1.23 | 0.87 | 2.19 | 881 | |

| Ni-Al2O3 | 1.5 | 14.31 | 3.21 | 0.19 | 6.78 | 108 |

| 2.0 | 11.8 | 7.27 | 0.33 | 4.96 | 541 | |

| 2.5 | 8.14 | 2.01 | 0.34 | 3.72 | 556 | |

| 3.0 | 5.18 | 4.86 | 0.13 | 7.29 | 280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).