1. Introduction

As B.S. McEwen & H. Akil have rightly stated, stress biology is one of the best understood systems in affective neuroscience and is an ideal target for addressing the pathophysiology of many brain-related diseases [

1]. The hippocampus is the brain structure, essential for both episodic and declarative memory and emotions, being at the crossroads of our response to stressful situations and other experiences. The hippocampus is selectively vulnerable to different unfavorable external and internal factors, and hippocampal dysfunction and atrophy was reported during aging and in different psychiatric and neurological disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, epilepsy, brain trauma, cognitive decline (e.g. Alzheimer's disease) [

2,

3,

4]. No wonder that atrophy of the hippocampus is one of the usual characteristics of common psychiatric disorders since most of these disease are stress-associated, and the hippocampus is specifically vulnerable to adverse effects of stress. Hippocampal atrophy may precede the development of disease symptoms or proceed simultaneously with the development of symptoms.

2. Stress, glucocorticoids and the hippocampus

Normal functioning of the major neurohumoral adaptive system of the body, endocrine stress axis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is implementing release of adrenal glucocorticoids (GCs), cortisol or corticosterone, both according to the circadian cycle and episodic stress-induced secretion. GC release from the adrenals in hourly pulses and after stress supports resilience (the ability to cope with threats, adversity, and trauma), being essential for body homeostasis and adaptation to stressogenic factors [

3,

4]. Effects of GCs are cell-specific and context-dependent, arranging the individual's response to changing environments. GCs have specific receptors in virtually all cells in the brain and periphery which enables to regulate metabolic, cardiovascular, immune, neuroendocrine processes, and behavioural activities as well. Circadian and acute stress-induced increases in GCs are necessary adaptive changes underlying survival of hippocampal neurons and memory formation. In addition to the documented immune suppressive actions of GCs, circadian elevations potentiate acute defensive responses by priming immune reactions [

5].

In adult mammals and humans, GCs promote resilience, in particular, by controlling and coordinating essential mechanisms of the hippocampal neuroplasticity, including glutamatergic neurotransmission, neuroinflammation, neurotrophic factors, neurogenesis, functioning of microglia and astrocytes, etc. [

6,

7]. GCs modify neural activity via two specific receptor types, high affinity mineralocorticoid (MR) and lower affinity glucocorticoid receptors (GR). Both MR and GR regulate gene transcription (act as transcription factors) and can rapidly operate non-genomically enhancing or suppressing neural activity [

8,

9,

10]. As a result, GCs regulate cellular function over diverse time scales.

According to E.R. de Kloet's neat expression, functional profile of the binary brain corticosteroid receptor system is "mediating, multitasking, coordinating, integrating" [

11]. MR and GR operate as a binary system together with neurotransmitter and neuropeptide signals to modulate stress reactions. The balance in signals mediated by MR and GR in specific brain regions , mainly in the limbic system, is vital for neuronal activity, stress response, adaptation, ample behavioral programming. This balanced function of MR and GR can be modified epigenetically, e.g. by a history of traumatic (early) life events and the experience of repeated stressors as well as by predisposing genetic variants in signaling pathways of these receptors [

5,

11]. Disturbed MR/GR balance makes nervous tissue susceptible to injuries; such damage can adversely affect stress response and increase the risk for psychopathology. MR occupation is believed to support pro-survival processes, specific GR overactivation favors neurodegeneration, while the continued co-activation of MR and GR during chronic stress results in less severe harmful effects [

12]. Though GRs are ubiquitously expressed in every cell in the nervous system, the expression level varies, suggesting that diverse cell types react differently to GR activation. Stress/GCs induce cell type-specific plasticity changes in neurons, Schwann cells, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes. The stress-induced plasticity may become maladaptive and contribute to neuropsychiatric disorders [

13]. The mechanisms affecting signaling through GRs are numerous and their study is one of the hot points in translational neuroscience since GR malfunction may be an essential link in the pathogenesis of virtually all brain diseases. One of example of such mechanisms is GR phosphorylation upon BDNF signaling in the neurons of the mesolimbic (reward) and corticolimbic (emotion) neural networks underlying the development of maladaptations to stress [

14].

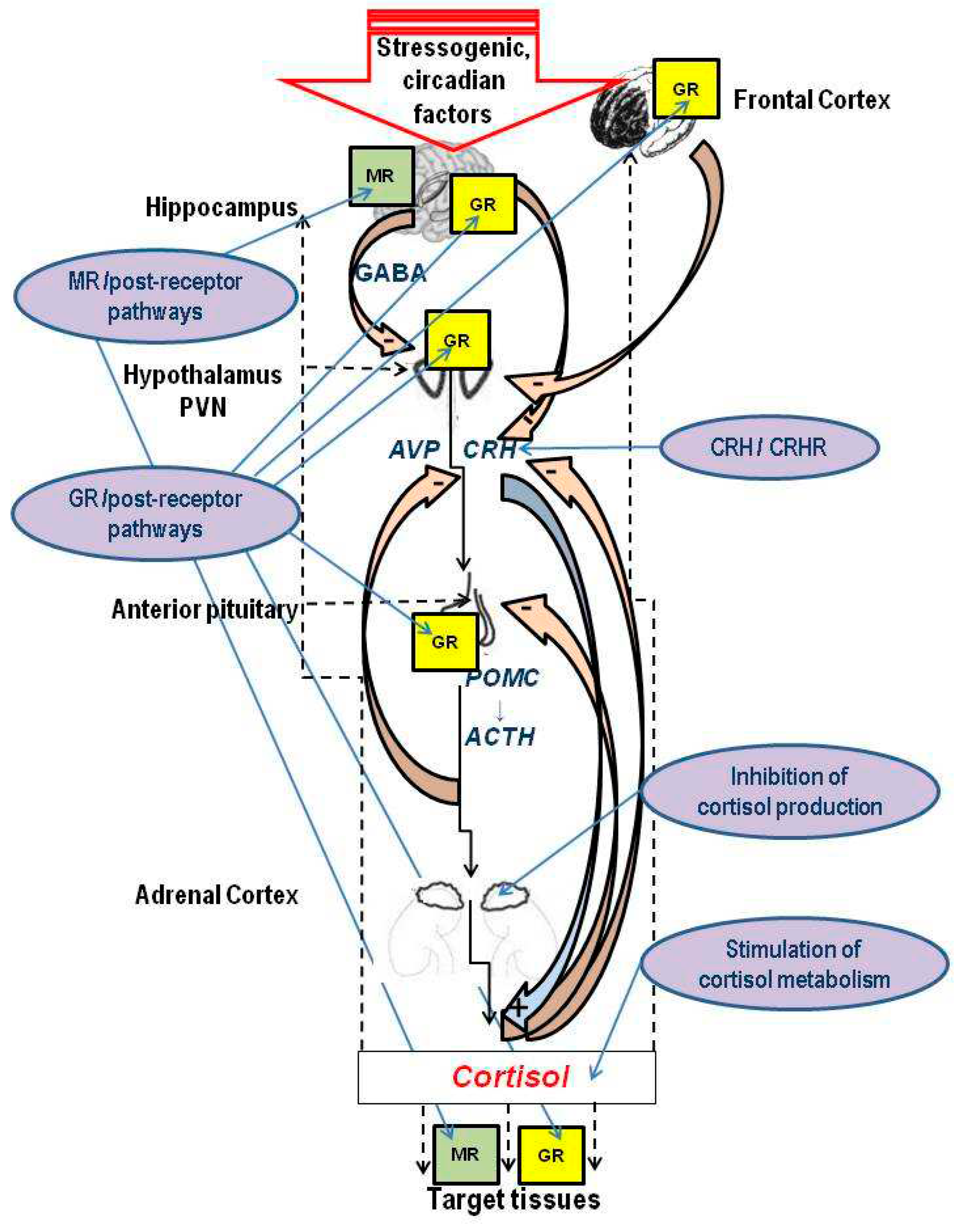

Activity of the HPA axis is tuned by GC feedback. Negative feedback by GCs involves various machinery directed to limiting HPA axis activation to prevent deleterious effects of GC overproduction. Ample GC release is tightly regulated by an intricate neural circuitry controlling hypothalamic corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) and vasopressin secretion, and in this way regulating pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (

Figure 1). Rapid feedback mechanisms involve nongenomic actions of GCs through MR and GR, mediate the instant inhibition of hypothalamic CRH and hypophyseal ACTH release, while long-term mechanisms are mediated by genomic actions through GR and involve the modulation of limbic circuitry and peripheral metabolic processess [

5,

8]. GCs, via genomic and nongenomic mechanisms, regulate hypothalamic stress neuron function and output through synaptic plasticity, changes in intrinsic excitability, and modulation of neuropeptide production [

15].

3. HPA dysfunction and mood diseases: Rationale for antiGC development

Brain cells are continuously exposed to GCs, which, in normal circumstances, is the key condition of ample stress response. However, chronically elevated levels of GCs resulting in sustained GC exposure have adverse influence on the brain, in particular, the hippocampus, where excessive GCs impair synaptic plasticity inducing neuronal cell damage, dendritic atrophy, reduction of hippocampal neurogenesis, hyperglutamatergic states and attenuation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and signaling [

7,

16,

17]. Chronic hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing's syndrome may be regarded as an extreme human model to study effects of cortisol excess on the brain. In Cushing's syndrome, hypersecretion of cortisol is associated with a high incidence of depression and anxiety, impairments in memory, and hippocampal atrophy [

18]. These patients display hippocampal damage with functional decline preceding structural abnormalities (as detected by brain imaging), while normalization of hypercortisolism stops the progression of hippocampal damage [

19].

Survivors of critical illness have been reported to be at considerably elevated risk of developing long-term cognitive impairment and psychiatric disorders [

20]. A critical illness is accompanied by an acute elevation of blood cortisol, which usually returns to normal after recovery; however, occasionally, prolonged deregulation of the HPA axis takes place. Excess of GCs can induce long-term changes to the adaptive neuroplasticity of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, at all levels, from structural and cellular plasticity to neuronal networks. This mechanism is believed to contribute to impairments of affective sphere underlying mental disorders [

7,

21]. While GCs, well known as anti-inflammatory drugs, may be neuroprotective during illness, they may also exacerbate inflammation-related neural damage, continual glucocorticoid elevations increasing the risk of unfavorable neuropsychiatric outcomes. Though a hypothesis describing how the anti-inflammatory effects of GCs may transform into the pro-inflammatory ones in the hippocampus have been proposed [

20,

22], mechanisms of such a functional transformation remain obscure.

A number of experimental studies demonstrated that treatment with compounds possessing anti-glucocorticoid properties (antiGCs) can improve cellular effects of chronic stress and thus provide a potentially important guide for therapy of stress-related disorders [

2]. Theoretically, multiple levels of potential "antiGC" targets include: a) the hypothalamic level: targeting CRH and CRH receptors; b) the pituitary level: targeting ACTH generation; c) the adrenal level: targeting cortisol metabolism in the adrenals; d) targeting extra-adrenal cortisol metabolism, and e) the receptor level: targeting GR, MR, and respective post-receptor signal transduction pathways (

Figure 1). Since the limbic system controlling the HPA axis is among the target tissues of cortisol, targeting MRs and GRs of the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala forms an additional, supra-hypothalamic level of the HPA axis regulation. According to the available data, most promising results of the preclinical and/or clinical studies include: effects of GR antagonists, extrahypothalamic actions on CRH using CRH receptors antagonists, inhibition of cortisol production in adrenals by blocking steroid 11-hydroxylase that converts 11-desoxycortisol to cortisol with metyrapon, reducing activity of reconverting enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (cortisone reductase, 11β-HSD1) with specific inhibitors [

23].

Figure 1.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and potential targets of antiglucocorticoid therapies [

4,

5,

8,

12,

16,

23].

Figure 1.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and potential targets of antiglucocorticoid therapies [

4,

5,

8,

12,

16,

23].

The schematic image shows a cascade nature of the HPA axis, the main neuroendocrine axis underlying stress response. The key events of this cascade include the release of the secretagogues corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP) from the medial parvocellular paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus in the portal circulation of pituitary; cleavage of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and ACTH release from the pituitary into systemic circulation; synthesis of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans or corticosterone in others species, including rodents) in the adrenal cortex and their release into the systemic circulation; binding of glucocorticoids (GCs) with glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) in the central and peripheral target tissues, including the brain after passing the blood-brain-barrier, and thus executing cellular effects of GCs. GRs are expressed in most brain structures and regions associated with the HPA axis, while limbic structures, primarily the hippocampus, are also rich in MR. Multi-level feedback loops from the hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenals as well as signals from the hippocampus and frontal cortex contribute to the regulation of the HPA axis, in particular tuning the circadian changes of circulating levels of GCs and decreasing them after the end of the stressor. The excitatory hippocampal output provides the inhibitory GABAergic input to the PVN, while gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibits secretion of hypothalamic hormones. Circulating GCs inhibit secretion of CRH from the hypothalamus and the secretion of ACTH from the pituitary, while circulating ACTH also inhibits hypothalamic secretion of CRH.

Main approaches to antiglucocorticoid therapies include: targeting CRH and CRH receptors, targeting cortisol synthesis in the adrenals and extra-adrenal cortisol catabolism as well as GR, MR, and respective post-receptor signal transduction pathways. Since the limbic system controlling the HPA axis is one of the target tissues of cortisol, targeting MR and GR of the hippocampus, frontal cortex and amygdala may provide HPA axis regulation on supra-hypothalamic level.

4. What cortisol level is abnormal: Cautionary notes

Abnormal HPA axis and high blood cortisol levels have been implicated in a variety of mood disease as well as neurodegenerative diseases, epilepsy and a number of other brain diseases. However, the aim of the following cautionary notes is to draw attention to some ambiguity of "high cortisol" definition. Normal values of cortisol for a blood sample taken at 8 in the morning are 5 to 25 mcg/dL or 140 to 690 nmol/L.[

24]. In other words, the minimal and maximal cortisol levels in the normal range may differ by five times! Normal values depend on the time of day, the clinical context and may vary slightly among different laboratories, however, in any case it is obvious that "normal" cortisol levels may differ dramatically between different individuals apart from circadian changes. This may be less important in studies comparing different cohorts of patients falling into the normal interval, though the variability of cortisol levels within a group can create a problem since bigger groups are needed for a decent statistical analysis. An alternative would be select within one cohort of patients groups with higher or lower cortisol in the biomaterial and compare the subgroups, how it was done in studies exploring cortisol involvement in consequences of focal brain damage [

25,

26,

27].

However, once we turn from cohorts to individual patient without previous history of cortisol measurement, we face a difficult problem understanding how tricky is it to evaluate a personal cortisol norm. Indeed, this is an important issue since in mood disorders baseline cortisol may be associated with the efficacy of antiGC therapy [

28]. Lack of consideration of this factor may be among major causes of inconsistencies in the results of antiGC treatment effectiveness reported by different groups.

5. GR antagonism

The GR antagonism is believed to be of considerable therapeutic value in stress-related psychopathologies. There is a body of pre-clinical evidence that GR antagonists should prevent pro-inflammatory effects caused by GC overdrive [

9]. Yet, it has been shown that blockade of all GR-dependent processes in the brain may exert unfavorable effects, such as elevated endogenous cortisol levels [

29] which is not surprising considering an essential role of GR in balancing stress response.

5.1. Mifepristone (RU 486) as a prototypic GR antagonist

Though a number of substances with different mechanisms of action (

Figure 1) have been used as antiGC treatment in both experimental and clinical premises, the majority of the published data is related to mifepristone (RU 486, 11-[4-(dimethylamino) phenyl]-17-hydroxy-17-[1-propynyl]-[11,17]-oestra-4,9-diene-3-one). Mifepristone (MIF), used mainly for termination of pregnancy, is a synthetic orally active steroid with powerful antiGC, antiprogestogen and a weak anti-androgen activity acting as a competitive receptor antagonist at the progesterone receptor in the presence of progesterone, and as a partial agonist in the absence of progesterone [

30]. MIF at higher doses than needed for progesterone antagonism shows an 18-fold higher affinity for GR than cortisol.

In experiments, MIF was able to inhibit the GC overdrive in different animal models of CNS disorders, from various stress-induced pathologies, to diabetes, alcohol abstinence and Alzheimer's disease. Atrophy of the hippocampus and its impaired function induced by either a single traumatic experience, chronic stress, early adversity or exogenous corticosterone can be rapidly restored with a brief MIF treatment. This striking effect of the mixed progesterone/glucocorticoid antagonist is mimicked by more specific anti-GCs such as e.g. CORT 108297, Dazucorilant, or CORT 113176. MIF and related GR antagonists rapidly reverse neurodegeneration and excessive neuronal activation, restore neurogenesis and ameliorate hippocampal cognitive deficits [

30,

31]. In the rodent hippocampus, MIF and related more selective GR antagonists can rapidly reset markers of pro-inflammatory activity, excitotoxicity, neuronal activation, and structural features of hippocampal atrophy [

31]. According to a recent analysis [

32], MIF is able to "reset" stress system activity as a result of prevention by GR antagonism the damaging effects of high GC concentrations via GR overactivation; continuing rebound suppression of HPA axis activity; action of MIF as an agonist in transrepression promoter of cell- and context-dependent recruitment of coactivators and co-repressors in brain stress circuitry; augmentation of brain MR activation and modifying MR:GR balance. The GRs targeted by MIF are located in elements of the HPA axis, but most probably also in limbic-frontocortical and mesocortical dopaminergic circuits involved in mood, anxiety, reward, and motivation.

Effect of MIF on the HPA axis is dependent on the dose, route, and daily frequency of administration (available data are summarized in [

9] and [

32]). As compared with experimental animals, in humans bio-availability of MIF is expanded because it circulates bound to ɑ1 glycoprotein and therefore has a longer half-life than in rodents where this binding protein is absent. In spite of problems in specificity, MIF has been shown to be clinically effective in the treatment of pathological conditions characterized by hypercortisolemia. During last decades medical uses of MIF are being actively explored for Cushing's syndrome and major psychotic depression [

33]. MIF is an effective drug for the treatment of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome of all etiologies, and in mental diseases effects of MIF spread beyond the affective symptoms. MIF (Korlym®), indicated for treatment of hyperglycemia in patients with Cushing’s syndrome, causes a significant metabolic improvement, lessens depressive symptoms, improves cognitive performance, and increases quality of life [

34]. MIF treatment appears to be effective and well tolerated in the treatment of psychosis in psychotic major depression [

35]. However, it should be noted that the data on MIF effects in mental diseases remain contradictory, at least partially because of its non-specificity regarding antiGC mechanisms.

5.2. Development of GR antagonists

Although clinical usage of the currently available antiGC drugs remains limited by their low specificity and some adverse side effect profiles, development of drugs specifically targeting the GR may lead to innovative strategies in the treatment of mood disorders.

Unpredictably, selective GR modulators are ligands that can act both as agonist and as antagonist like the high-affinity GR ligand C108297 (4Ar)-4a-(ethoxymethyl)-1- (4-fluorophenyl)-6-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]sulfonyl-4,5,7,8-tetrahydropyrazolo[3–g]isoquinoline), shown to be a selective GR modulator in the rat brain. C108297 possesses a unique interaction profile between GR and its downstream effector molecules, the nuclear receptor coregulators, as compared with the full GR agonist dexamethasone and GR antagonist MIF. C108297 has incomplete agonistic activity suppressing CRH gene expression and enhancing GR-dependent memory consolidation, though it lacks agonistic effects on the expression of CRH in the central amygdala and antagonizes GR-mediated reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis after chronic corticosterone exposure [

9]. It is suggested that C108297 represents a class of ligands with a potential to more selectively abolish pathogenic GR-dependent processes in the brain, while retaining beneficial aspects of GRs. CORT108297 pharmacologically disrupts GR signaling and reverses at least some of the effects of adolescent stress on emotional behavior and circuit development in rodents [

36]. CORT108297 prevents the GC-induced decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis in normal mice, normal rats, and Wobbler mice, prevents spinal cord pathology, while displaying anti-inflammatory and anti-glutamatergic activity; it also inhibits diet-induced obesity and inflammation [

30,

32]. MIF, C-108297, and another GR antagonist, C-113176, reversed the precipitation of Alzheimer-like pathology and cognitive impairment in an animal model generated by hippocampal amyloid-β25−35 administration. Thus, more selective GR modulators may be used for targeted treatment.

5.3. Endogenous antiGCs

Unlike cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulphated form DHEA(S), endogenous neuroactive steroids with antiGC properties, have been associated with neuroprotection and healthy aging. From the functional perspective, DHEA may be regarded an endogenous antiGC. An imbalance in the cortisol/DHEA(S) ratio has been implicated in the pathophysiology of stress-related psychiatric disorders [

37]. Elevated cortisol/DHEA ratios may be a state marker of depressive illness and may contribute to the associated deficits in learning and memory [

38]. Cortisol and DHEA(S) levels correlated with symptom severity in first-episode psychosis. In a large longitudinal cohort study of older men and women higher DHEA(S) levels were associated with reduced risk of developing depressive symptoms [

39]. There is some evidence that DHEA may have an antiGC effect, offering protection against the deleterious effects of cortisol, and the cortisol/DHEA ratio may be a practical biological marker of treatment-resistant depression [

40]. Administration of DHEA similar to other antiGC treatments may reduce neurocognitive deficits in depression [

38], however, treatment with exogenous DHEA does not seem to have advantages as compared with other antiGC interventions.

Noteworthy, quite a different approach to experimental anti-glucocorticoid gene therapy, overexpressing a GC-degrading enzyme, 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (type II) in hippocampal neurons, reversed the impairing effects of elevated corticosterone on spatial memory, hippocampal neuronal excitability, and synaptic plasticity in mice [

41]. These data suggest that another promising approach of antiGC gene therapy may be further explored.

6. AntiGC treatment of affective disorders

6.1. Major depressive disease

It is believed that major depressive disease (MDD) is associated with changes in neuroplasticity in specific regions of the brain, in particular limbic ones, these changes being associated with symptom severity, negative emotional rumination and fear learning. MDD is associated with atrophy of neurons in the cortical and limbic brain regions that control mood and emotion. Antidepressant therapy beneficially affects neuroplasticity and can reverse the neuroanatomical changes found in depressed patients.[

42]. Since GCs control signal transduction pathways associated with the neurogenesis in the hippocampus, antiGCs, like conventional antidepressants, may recover depressive symptoms by boosting hippocampal neurogenesis [

43].

Deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been described in patients with MDD, similarly to many other psychiatric conditions. There is persistent rise in the levels of cortisol (end product of the HPA axis) and impairment of the negative feedback inhibition mechanism of the HPA axis. Hypercortisolism, and its resistance to dexamethasone suppression were well documented in MDD patients. It therefore seemed reasonable that drugs which interfere with cortisol biosynthesis might bring about a remission [

44], and cortisol-lowering treatments were suggested to be of clinical benefit in selected individuals with MDD and other hypercortisolemic conditions [

45]. The new therapy strategies include use of different drugs classified as "antiGCs" (inhibition of hypothalamic CRH release, antagonism at CRH1 receptors, antagonism at vasopressin V1b receptors, inhibition of cortisol synthesis, antiGC treatment with DHEA, treatment with GR antagonists and agonists, etc.) [

46]. Importantly, effective antidepressant treatments are believed to trigger and maintain GR-related cellular processes necessary for recovery from MDD. Classic antidepressants act indirectly, by affecting the dynamic interplay between serotonin neurotransmission and the HPA axis [

47].

The antiGC strategies in hypercortisolemic states with special focus onmood diseases have been discussed from early 90th. The analysis of behavioral effects of anticortisolemic drugs administration in Cushing's syndrome and MDD (frequently associated with cortisol hypersecretion) from small-scale studies suggested that such interventions lessen depressive symptoms and provide hope for the development of a novel class of antidepressant agents for hypercortisolemic depressed patients [

48]. Ketoconazole administration in hypercortisolemic depression was associated with decreases in serum cortisol levels and in depression ratings [

49,

50,

51]. GC antagonist MIF (RU 486) was also effective in preliminary studies on MDD patients [

52]. Ketoconazole, MIF and DHEA were discussed as potential novel mood-altering agents and antiGC drug treatment was suggested as useful in certain subgroups of patients with MDD [

53].The preclinical tests demonstrated an antidepressant-like profile for metyrapone blocking cortisol steroidogenesis by acting as a reversible inhibitor of 11β-hydroxylase [

54].

It should be noted that the degree and specific features of HPA axis dysfunction is very variable in patients with MDD. There may be many factors affecting the pattern of HPA axis disturbances, this issue remaining largely unexplored. In patients with MDD, HPA axis dysfunction may be age-dependent. R. Hirtz et al. showed that adrenal steroid metabolome in adolescent MDD displays a distinct steroid pattern indicating specific features of the HPA axis disturbances. They also suggested that cortisol/DHEA ratio may be used in psychiatry to identify patients who would potentially benefit from antiGC treatment or patients with a high risk for recurrence in case HPA axis remains dysfunctional [

55]. The individual differences in specific HPA abnormalities may at least partially explain why the results of numerous studies focusing on the use HPA-modulating drugs to treat MDD remain contradictory and the efficacy of these medications for MDD is still doubtful. Though preclinical data suggest that CRH1 receptor antagonists are useful in the treatment of depression, there is no confirmed evidence from controlled studies of their clinical efficacy in depressed patients. The beneficial effects of neuroactive steroid DHEA, the cortisol synthesis inhibitor metyrapone and the GR antagonist MIF in MDD has been demonstrated in some small, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. However, several recently completed trials failed to significantly separate MIF from placebo in MDD [

46]. Yet, a meta-analysis recently performed by Y. Ding showed that the effectiveness of HPA-targeting medications for MDD was significant, while subgroup analysis showed that patients with MDD may benefit from MIF and V1B receptor antagonist treatments that have tolerable side effects [

56].

6.2. Treatment-resistant depression

Many patients with MDD have treatment-resistant depression (TRD), demonstrating no adequate response to two consecutive courses of antidepressants. Hypercortisolaemia, well described in depression, may be an important factor associated with treatment resistance. In general, deregulation of the HPA axis is associated with no response to antidepressants and relapse following successful treatment. The treatment resistance in MDD has been also associated, both prospectively and retrospectively, with increased inflammation, and inflammatory activity may be another key factor influencing responses to antidepressants. Preclinical data showed that co-administration of corticosteroids resulted in a reduction in the ability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to increase forebrain 5-hydroxytryptamine, while co-administration of antiGCs had the opposite effect [

57]. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of augmentation of serotonergic antidepressants with metyrapone, showed that this cortisol synthesis inhibitor was superior to placebo in reducing the score according to Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale in MDD patients [

58]. However, metyrapone, potentially effective in MDD, did not reduce cortisol in patients with TRD, probably due to GC system overcompensation [

59]. Another study reported that metyrapone used for the augmentation of serotonergic antidepressants in TRD did not show efficacy in a broadly representative population of such patients [

60]. The results of a randomized controlled trial of augmentation by metyrapone of antidepressants in MDD showed that though metyrapone augmentation was well tolerated, it seemed ineffective in the treatment of TRD [

61]. Most authors suggest that future research should target antiGC treatments at patients with confirmed hypercortisolaemia. This may be a reasonable approach since a following meta-analysis of cortisol levels in the samples of patients treated with cortisol synthesis inhibitors (metyrapone and ketoconazole) and GR antagonist (MIF) showed that only patients with higher baseline cortisol levels benefited from treatment with cortisol synthesis inhibitors; in other words cortisol was a predictive biomarker for a successful treatment of patients with mood disorders with these medications [

28].

6.3. Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia

Since augmented cortisol levels are reported in bipolar disorder, and hypercortisolaemia may aggravate both neurocognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, antiGC treatments, particularly corticosteroid receptor antagonists, were suggested to improve neurocognitive functioning and attenuate depressive symptoms. In a small study with a double-blind crossover design on 20 patients with bipolar disorder, MIF elicited selective improvement in neurocognitive functioning and mood suggesting that GR antagonists may have useful cognitive-enhancing and possibly antidepressant properties in bipolar disorder [

62]. A preliminary evidence was provided that MIF treatment resulted in a slight but significant decrease in HPA axis activity and peripheral cortisol level decline in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia [

63]. In a small scale placebo controlled study, ketoconazole treatment of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder was associated with significant improvements in observer-rated depression, but not in subjectively rated depression, psychotic symptom ratings, or cognitive performance scores [

64]. These pilot data partially support the hypothesis that antiGCs reduce depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, though studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

Patients with neuropsychiatric disorders (i.e., mood disorders and schizophrenia) display all key features of inflammation, including augmented circulating levels of inflammatory inducers, activated sensors, and inflammatory mediators targeting all tissues [

65]. From the stress response perspective, inflammation may be regarded as a type of allostatic load involving the immune, endocrine, and nervous systems [

66]. Proinflammatory cytokines modulate mood behavior and cognition by inducing neuroinflammation, in particular in the hippocampus and other selected limbic structures. Neuroinflammation is involved in the pathophysiology of stress-associated mood diseases (e.g. MDD) by rising proinflammatory cytokines in brain tissue, activating neuroendocrine responses, in particular, the HPA axis, escalating GC resistance, promoting excitotoxicity, reducing brain monoamine levels (in particular, influencing serotonin metabolism), affecting neurogenesis, and thus impairing all levels of neuroplasticity [

7]. Both cytokines and GCs can have pro-inflammatory actions in the brain [

67]. Neuroinflammation contributes to non-responsiveness to current therapies, response to conventional antidepressants being associated with a reduction in inflammatory biomarkers, while resistance to treatment - with augmented inflammation [

68].

6.4. Beyond affective symptoms: Cognitive dysfunction, metabolic disturbances, diabetes

Importantly, pharmacological manipulations with GCs may be productive both for mood change and memory deficit. This is expected since the fact that prolonged elevation in GC level may result in disturbances of mood and cognition seems undoubted. In patients with endogenous depression, hypercortisolaemia may be associated with cognitive dysfunction and possibly a decrease in hippocampal volume [

18]. In each of these conditions, reduction of GC level, either through discontinuation of steroid treatment or through usage of antiGC agents, ameliorates the unfavorable effects on behavior. Conversely, traditional antidepressant agents may, in addition, stabilize mood through effects on the HPA axis. There is an extensive body of evidence that, especially in elderly, depression is associated with significant cognitive impairment. The comorbidity of both syndromes can be explained by the existence of several overlapping pathophysiological processes playing a key role in the etiology of both depression and dementia. A "stress syndrome" manifested in elevated cortisol levels, has been observed in up to 70% of depressed patients and also in Alzheimer's disease pathology. Stress-induced hippocampal neuronal damage results in both emotional and cognitive impairment, both of them mediated by neuroinflammatory mechanisms [

69]. MDD is prodromal to, and a component of Alzheimer's disease, it may also be a trigger for developing Alzheimer's disease. HPA axis is disturbed in both pathologies, and GCs have marked degenerative actions on the hippocampus [

67].

Another potential application of antiGC drugs is to alleviate adverse side effects of drugs used for treatment of mental diseases. For example, antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, are associated with considerable weight gain and metabolic disturbances. There are preliminary data showing that coadministration of miricorilant, a selective GR modulator, with olanzapine can ameliorate these effects [

70].

Clinical studies report a frequent coexistence of depression and diabetes, both diseases being associated with comparable alterations in the structure and function of the hippocampus and with comparable disturbances in cognitive processes. Some morphological and functional transformations going on in these diseases are associated with augmented GCs, proinflammatory cytokine and hyperglutamatergic states [

7,

71]. Excess GCs induced by stress not only affect hippocampal synaptic plasticity but also impair brain glucose metabolism and reduce insulin sensitivity thus limiting energy supply for support of proper neuronal plasticity. Dysfunctional HPA axis represent a neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes. Individuals with mood disorders have a higher prevalence of hypercortisolemia accompanied by insulin resistance. The use of antiGC agents in treatment of mood disorders associated with metabolic dysfunction is debated. Treatment with antiGC agent, MIF, of patients receiving treatment for depressive disorders and euthymic at baseline contributed to improvements in attention and verbal learning which were associated with reduction of fasting plasma glucose [

72].

7. Conclusions

The stress response engulfs different brain regions and levels from molecular to neuronal circuits. “It is the whole brain, not just a small piece of it, that manages stress responses and tries its best to integrate the capacities of the entire mind-body of the organism”[

31]. This is absolutely right, and yet we focus on the hippocampus in this review. First, the hippocampus is the brain structure coordinating and controlling both cognitions, and emotions. Following the discovery of receptors of GCs in the hippocampus and other brain regions, research has focused on understanding the effects of GCs in the brain and their role in regulating emotion and cognition. Second, the hippocampus is selectively vulnerable to stress, GCs and neuroinflammation and, thus, studying this structure can facilitate understanding some key mechanisms of mood diseases and their comorbidities. Third, as compared with other brain regions, the limbic system is more extensively explored with respect to stress response and controlling involvement of the HPA axis in stress-associated brain pathologies.

GCs are vital for adaptation to stressors (allostasis) and in maladaptation resulting from allostatic load and overload occurring during chronic stress and reshaping the HPA axis [

73]. AntiGCs may have antidepressant effects and have been reported to be efficacious in the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders. Yet, there are some contradictions between the data of different studies related to methodological differences between them with respect to the drugs used, patient cohorts, and study design. That's why the use of antiGCs in the treatment of mood disorders is still at the proof-of-concept stage. Though targeting the HPA axis and receptors of GCs is very promising, additional large randomized controlled trials are still needed to justify the findings [

74].

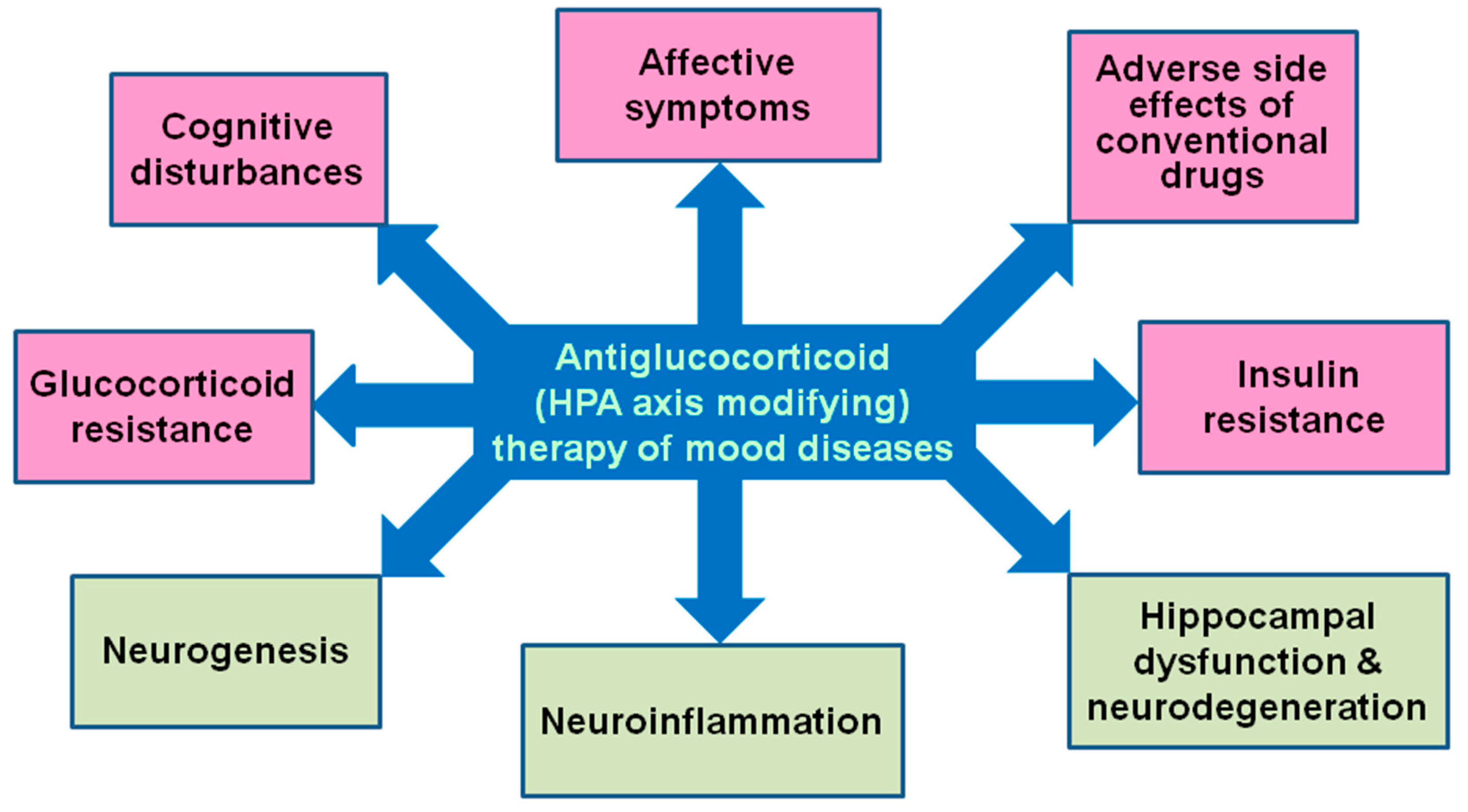

Noteworthy, chronic excess of GCs is associated not only with mood diseases, but also with cognitive decline, metabolic disorders, diabetes. AntiGC (HPA axis modifying) therapy has a potential to alleviate affective symptoms, cognitive disturbances, GC and insulin resistance and adverse side effects of conventional drugs through beneficial effects on hippocampal dysfunction and neurodegeneration, as well as neuroinflammation and neurogenesis (

Figure 2). GC levels rise rapidly following status epilepticus and remain elevated for weeks after the injury. The GR specific modulator CORT108297 normalized corticosterone levels and reduced brain pathology following status epilepticus [

75]. It is becoming clear that stress/GC-associated neuroinflammation-mediated pathology of the limbic system and, specifically, the hippocampus, is a general feature typical for many brain diseases that share common mechanisms. Novel MR-GR modulators are becoming available that may reset a deregulated stress response system [

6,

23,

76] and be used in treatment of a variety of brain diseases.

Antiglucocorticoid therapy (mifepristone as an example) in clinical studies (and in rodent models of affective diseases) can ameliorate affective symptomes, reduce cognitive disturbances, overcome adverse side effects of conventional drugs, decrease glucocorticoid and insulin resistance. In animal studies, antiglucocorticoid treatment reverse or prevent hippocampal dysfunction and neurodegeneration, reduces neuroinflammation and improves disturbed neurogenesis.

Funding

This research was not supported by external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbrevations

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; antiGC, antiglucocorticoid; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; GC, glucocorticoid; DHEA(S), dehydroepiandrosterone(sulfate); GR, glucocorticoid receptor; MDD, major depression disease; MIF, mifepristone; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; TRD, treatment-resistant depression.

References

- McEwen, B.S., Akil. H. Revisiting the Stress Concept: Implications for Affective Disorders. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40,:12-21. [CrossRef]

- Dhikav, V., Anand, K.S. Is hippocampal atrophy a future drug target? Med. Hypotheses. 2007, 68, 1300-1306. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, N.V. Functional Neurochemistry of the Ventral and Dorsal Hippocampus: Stress, Depression, Dementia and Remote Hippocampal Damage. Neurochem Res. 2019, 44, 1306-1322. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, N V. Biochemical Mechanisms and Translational Relevance of Hippocampal Vulnerability to Distant Focal Brain Injury: The Price of Stress Response. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2019, 84, 1306-1328. [CrossRef]

- Uchoa, E.T., Aguilera, G., Herman, J.P., Fiedler, J.L., Deak, T., de Sousa, M.B. Novel aspects of glucocorticoid actions. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 26, 557-572. [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, E.R., Joëls, M. The cortisol switch between vulnerability and resilience. Mol. Psychiatry. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, N.V. Glucocorticoids Orchestrate Adult Hippocampal Plasticity: Growth Points and Translational Aspects. Biohemistry (Mosc.) 2023, 88, 565-589. [CrossRef]

- Joëls, M., Sarabdjitsingh, R.A., Karst, H. Unraveling the time domains of corticosteroid hormone influences on brain activity: rapid, slow, and chronic modes. Pharmacol Rev. 2012, 64, 901-938. [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, E.R., de Kloet, S.F., de Kloet, C.S., de Kloet, A.D. Top-down and bottom-up control of stress-coping. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 31, e12675. [CrossRef]

- Daskalakis, N.P., Meijer, O.C., de Kloet, E.R. Mineralocorticoid receptor and glucocorticoid receptor work alone and together in cell-type-specific manner: Implications for resilience prediction and targeted therapy. Neurobiol. Stress. 2022,18, 100455. [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, E.R. Functional profile of the binary brain corticosteroid receptor system: mediating, multitasking, coordinating, integrating. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013, 719, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N., Cerqueira, J.J., Almeida, O.F. Corticosteroid receptors and neuroplasticity. Brain Res. Rev. 2008, 57, 561-570. [CrossRef]

- Madalena, K.M., Lerch, J.K. The Effect of Glucocorticoid and Glucocorticoid Receptor Interactions on Brain, Spinal Cord, and Glial Cell Plasticity. Neural Plast. 2017, 8640970. [CrossRef]

- Jeanneteau, F., Borie, A., Chao, M.V., Garabedian, M.J. Bridging the Gap between Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Glucocorticoid Effects on Brain Networks. Neuroendocrinology. 2019, 109, 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S., Iremonger, K.J. Temporally Tuned Corticosteroid Feedback Regulation of the Stress Axis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 783-792. [CrossRef]

- Suri, D., Vaidya, V.A. Glucocorticoid regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor: relevance to hippocampal structural and functional plasticity. Neuroscience. 2013, 239, 196-213. [CrossRef]

- Podgorny, O.V., Gulyaeva, N.V. Glucocorticoid-mediated mechanisms of hippocampal damage: Contribution of subgranular neurogenesis. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 370-392. [CrossRef]

- Reus, V.I., Wolkowitz, O.M. Antiglucocorticoid drugs in the treatment of depression. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2001, 10, 1789-1796. [CrossRef]

- Resmini, E., Santos, A., Webb, S.M. Cortisol Excess and the Brain. Front. Horm. Res. 2016, 46, 74-86. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.R., Spencer-Segal, J.L. Glucocorticoids and the Brain after Critical Illness. Endocrinology. 2021, 162, bqaa242. [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, N.V. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity: An Expanding Universe. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2017, 82, 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Bolshakov, A.P., Tret'yakova, L.V., Kvichansky, A.A., Gulyaeva, N.V. Glucocorticoids: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of Hippocampal Neuroinflammation. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 2021, 86, 156-167. [CrossRef]

- Martocchia, A., Stefanelli, M., Falaschi, G.M., Toussan, L., Rocchietti March, M., Raja, S., Romano, G., Falaschi, P. Targets of anti-glucocorticoid therapy for stress-related diseases. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2013,;8, 79-87. [CrossRef]

- Appendix B - Common Laboratory Tests. in: Pharmacotherapy Principles and Practice, 6th Edition. Chisholm-Burns, M. A., Schwinghammer, T. L., Malone, P. M., Kolesar, J. M., Lee, K.C., Bookstaver P. B., eds. McGraw-Hill Medical 2022.

- Wang, J., Guan, Q., Sheng, Y., Yang, Y., Guo, L., Li, W., Gu, Y., Han, C. The potential predictive value of salivary cortisol on the occurrence of secondary cognitive impairment after ischemic stroke. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 1103–1108. [CrossRef]

- Ben Assayag, E., Tene, O., Korczyn, A. D., Shopin, L., Auriel, E., Molad, J., Hallevi, H., Kirschbaum, C., Bornstein, N. M., Shenhar-Tsarfaty, S., Kliper, E., Stalder, T. High hair cortisol concentrations predict worse cognitive outcome after stroke: Results from the TABASCO prospective cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017, 82, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Tene, O., Hallevi, H., Korczyn, A. D., Shopin, L., Molad, J., Kirschbaum, C., Bornstein, N. M., Shenhar-Tsarfaty, S., ., Kliper, E., Auriel, E., Usher, S., Stalder, T., Ben Assayag, E. The Price of Stress: High Bedtime Salivary Cortisol Levels Are Associated with Brain Atrophy and Cognitive Decline in Stroke Survivors. Results from the TABASCO Prospective Cohort Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 65, 1365–1375. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, G., Enache, D., Gianotti, L., Schatzberg, A.F., Young, A.H., Pariante, C.M., Mondelli, V. Baseline cortisol and the efficacy of antiglucocorticoid treatment in mood disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019, 110, 104420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104420.

- Zalachoras, I., Houtman, R., Atucha, E., Devos, R., Tijssen, A.M., Hu, P., Lockey, P.M., Datson, N.A., Belanoff, J.K., Lucassen, P.J., Joëls, M., de Kloet, E.R., Roozendaal, B., Hunt, H., Meijer, O.C. Differential targeting of brain stress circuits with a selective glucocorticoid receptor modulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci .U. S. A. 2013, 110, 7910-7915. [CrossRef]

- De Nicola, A.F., Meyer, M., Guennoun, R., Schumacher, M., Hunt, H., Belanoff, J., de Kloet, E.R., GonzalezDeniselle, M,C. Insights into the Therapeutic Potential of Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulators for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2137. [CrossRef]

- de Kloet, E.R. Glucocorticoid feedback paradox: a homage to Mary Dallman. Stress. 2023, 26, 2247090. [CrossRef]

- Dalm, S., Karssen, A.M., Meijer, O.C., Belanoff, J.K., de Kloet, E.R.. Resetting the Stress System with a Mifepristone Challenge. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 39, :503-522. [CrossRef]

- Kakade, A.S., Kulkarni, Y.S. Mifepristone: current knowledge and emerging prospects. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 2014, 112, 36-40. PMID: 25935948.

- Fleseriu, M., Biller, B.M., Findling, J.W., Molitch, M.E., Schteingart, D.E., Gross, C.; SEISMIC Study Investigators. Mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, produces clinical and metabolic benefits in patients with Cushing's syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 2039-2049. [CrossRef]

- DeBattista, C., Belanoff, J., Glass, S., Khan, A., Horne, R.L., Blasey, C., Carpenter, L.L., Alva, G. Mifepristone versus placebo in the treatment of psychosis in patients with psychotic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006, 60, 1343-1349. [CrossRef]

- Cotella, E.M., Morano, R.L., Wulsin, A.C., Martelle, S.M., Lemen, P., Fitzgerald, M., Packard, B.A., Moloney, R.D., Herman, J.P. Lasting Impact of Chronic Adolescent Stress and Glucocorticoid Receptor Selective Modulation in Male and Female Rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020, 112, 104490. [CrossRef]

- Garner,B., Phassouliotis, C., Phillips, L.J., Markulev, C., Butselaar, F., Bendall, S., Yun, Y., McGorry, P.D. Cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulphate levels correlate with symptom severity in first-episode psychosis. J. Psychiat.r Res. 2011, 45, 249-255. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.H., Gallagher, P., Porter, R.J. Elevation of the cortisol-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio in drug-free depressed patients. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002, 159, 1237-1239. [CrossRef]

- Souza-Teodoro, L.H., de Oliveira, C., Walters, K., Carvalho, L.A. Higher serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate protects against the onset of depression in the elderly: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA). Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016, 64, 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Markopoulou, K., Papadopoulos, A., Juruena, M.F., Poon, L., Pariante, C.M., Cleare, A.J. The ratio of cortisol/DHEA in treatment resistant depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009, 34, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Dumas, T.C., Gillette, T., Ferguson, D., Hamilton, K., Sapolsky, R.M. Anti-glucocorticoid gene therapy reverses the impairing effects of elevated corticosterone on spatial memory, hippocampal neuronal excitability, and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 1712-1720. [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, I., Drăgo,i A.M., Trifu, S.C., Cristea, M.B. Neuroplasticity and depression: Rewiring the brain's networks through pharmacological therapy (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1131. [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, C.P,. van Hooijdonk, L.W., Morrow, J.A., Peeters, B.W., Hamilton, N., Craighead, M., Vreugdenhil, E. Antiglucocorticoids, neurogenesis and depression. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 249-264. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.E. Antiglucocorticoid therapies in major depression: a review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997, 22 Suppl 1, S125-S132. PMID: 9264159. [CrossRef]

- Wolkowitz ,O.M., Reus, V.I. Treatment of depression with antiglucocorticoid drugs. Psychosom. Med. 1999, 6, 698-711. [CrossRef]

- Schüle, C., Baghai, T.C., Eser, D., Rupprecht, R. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system dysregulation and new treatment strategies in depression. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 1005-1019. [CrossRef]

- Maric, N.P., Adzic, M. Pharmacological modulation of HPA axis in depression - new avenues for potential therapeutic benefits. Psychiatr. Danub. 2013, 25, 299-305. PMID: 24048401.

- Wolkowitz, O.M., Reus, V.I., Manfredi, F., Ingbar, J., Brizendine, L. Antiglucocorticoid strategies in hypercortisolemic states. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1992, 28, 247-251. PMID: 1480727.

- Wolkowitz, O.M., Reus, V.I., Manfredi ,F., Ingbar, J., Brizendine, L., Weingartner, H. Ketoconazole administration in hypercortisolemic depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1993, 150, 810-812. [CrossRef]

- Anand, A., Malison, R., McDougle, C.J., Price, L.H. Antiglucocorticoid treatment of refractory depression with ketoconazole: a case report. Biol. Psychiatry. 1995, 37, 338-340. [CrossRef]

- Wolkowitz, O.M., Reus, V.I., Chan, T., Manfredi, F., Raum, W., Johnson, R., Canick, J. Antiglucocorticoid treatment of depression: double-blind ketoconazole. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999, 45,1070-1074. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.E., Filipini, D., Ghadirian, A.M. Possible use of glucocorticoid receptor antagonists in the treatment of major depression: preliminary results using RU 486. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1993, 18, 209-213. PMID: 8297920.

- Reus, V.I., Wolkowitz, O.M., Frederick, S. Antiglucocorticoid treatments in psychiatry. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997, 22 Suppl 1, S121- S124. [CrossRef]

- Healy, D.G., Harkin, A., Cryan, J.F., Kelly, J.P., Leonard, B.E. Metyrapone displays antidepressant-like properties in preclinical paradigms. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1999, 145, 303-308. [CrossRef]

- Hirtz, R., Libuda, L., Hinney, A., Föcker, M., Bühlmeier, J., Holterhus, P.M., Kulle, A., Kiewert, C., Hauffa, B.P., Hebebrand, J., Grasemann, C. The adrenal steroid profile in adolescent depression: a valuable bio-readout? Transl. Psychiatry. 2022, 12, 255. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Wei, Z., Yan, H., Guo, W. Efficacy of Treatments Targeting Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Systems for Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 732157. [CrossRef]

- McAllister-Williams, R.H., Smith, E., Anderson, I.M., Barnes, J., Gallagher, P., Grunze, H.C., Haddad, P.M., House, A.O., Hughes, T., Lloyd, A.J., McColl, E.M., Pearce, S.H., Siddiqi, N., Sinha, B., Speed, C., Steen, I.N., Wainright, J., Watson, S., Winter, F.H., Ferrier, I.N. Study protocol for the randomised controlled trial: antiglucocorticoid augmentation of anti-Depressants in Depression (The ADD Study). BMC Psychiatry. 2013, 13, 205. [CrossRef]

- Sigalas, P.D., Garg, H., Watson, S., McAllister-Williams, R.H., Ferrier, I.N. Metyrapone in treatment-resistant depression. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 2, 139-149. [CrossRef]

- Strawbridge, R., Jamieson, A., Hodsoll, J., Ferrier, I.N., McAllister-Williams, R.H., Powell, T.R., Young, A.H., Cleare, A.J., Watson, S. The Role of Inflammatory Proteins in Anti-Glucocorticoid Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 784. PMID: 33669254. [CrossRef]

- McAllister-Williams, R.H., Anderson I,M., Finkelmeyer, A., Gallagher, P., Grunze, H.C., Haddad, P.M., Hughes, T., Lloyd, A.J., Mamasoula, C., McColl, E., Pearce, S., Siddiqi, N., Sinha, B.N., Steen, N., Wainwright, J., Winter, F.H., Ferrier, I.N., Watson, S.; ADD Study Team. Antidepressant augmentation with metyrapone for treatment-resistant depression (the ADD study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016, 3, 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, I.N., Anderson, I.M., Barnes, J., Gallagher, P., Grunze, H.C.R., Haddad, P.M., House, A.O., Hughes, T., Lloyd, A.J., Mamasoul,a C., McColl. E., Pearce, S., Siddiqi, N., Sinha, B., Speed, C., Steen, N., Wainwright, J., Watson, S., Winter, F.H., McAllister-Williams ,R.H.; the ADD Study Team. Randomised controlled trial of Antiglucocorticoid augmentation (metyrapone) of antiDepressants in Depression (ADD Study). Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015, PMID: 26086063. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.H., Gallagher, P., Watson, S., Del-Estal D., Owen, B.M., Ferrier, I.N. Improvements in neurocognitive function and mood following adjunctive treatment with mifepristone (RU-486) in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004, 29, 1538-1545. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P., Watson, S., Elizabeth Dye, C., Young, A.H., Nicol Ferrier, I. Persistent effects of mifepristone (RU-486) on cortisol levels in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 1037-1041. [CrossRef]

- Marco, E.J., Wolkowitz, O.M., Vinogradov, S., Poole, J.H., Lichtmacher, J., Reus, V.I. Double-blind antiglucocorticoid treatment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a pilot study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002, 3,156-161. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.E, Teixeira, A.L. Inflammation in psychiatric disorders: what comes first? Ann. N. Y. Acad .Sci. 2019, 1437, 57-67. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.W., Kim, Y.K. The role of neuroinflammation and neurovascular dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018 ,11, 179-192. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J., Lucassen, P.J. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: Genes, steroids, cytokines and neurogenesis - What do we need to know? Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2016, 41, 153-171. [CrossRef]

- Adzic, M., Brkic, Z., Mitic, M., Francija, E., Jovicic, M.J., Radulovic, J., Maric, N.P. Therapeutic Strategies for Treatment of Inflammation-related Depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 176-209. [CrossRef]

- Linnemann, C., Lang, U.E. Pathways Connecting Late-Life Depression and Dementia. Front. Pharmacol. 2020,11, 279. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.J., Donaldson, K., Strem, M., Tudor, I.C., Sweet-Smith, S., Sidhu, S. Effect of Miricorilant, a Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator, on Olanzapine-Associated Weight Gain in Healthy Subjects: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 632-637. [CrossRef]

- Detka, J., Kurek, A., Basta-Kaim, A, Kubera, M., Lasoń, W., Budziszewska, B. Neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 1591-1600. [CrossRef]

- Roat-Shumway, S., Wroolie, T.E., Watson, K., Schatzberg, A.F., Rasgon N.L. Cognitive effects of mifepristone in overweight, euthymic adults with depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239,242-246. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.D., Kogan, J.F., Marrocco, J., McEwen, B.S. Genomic and epigenomic mechanisms of glucocorticoids in the brain. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017,13, 661-673. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, P., Malik, N., Newham, J., Young, A.H., Ferrier, I.N., Mackin, P. Antiglucocorticoid treatments for mood disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, CD005168. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD005168. [CrossRef]

- Wulsin, A.C., Kraus, K.L., Gaitonde, K.D., Suru, V., Arafa, S.R., Packard, B.A., Herman, J.P., Danzer, S.C. The glucocorticoid receptor specific modulator CORT108297 reduces brain pathology following status epilepticus. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 341, 113703. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, O.C., Koorneef, L.L., Kroon, J. Glucocorticoid receptor modulators. Ann. Endocrinol (Paris). 2018, 79, 107-111. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).