Submitted:

17 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Method and Details

2.1. Simulation Details

2.2. Model Development

2.2.1. Force Field and Parameters

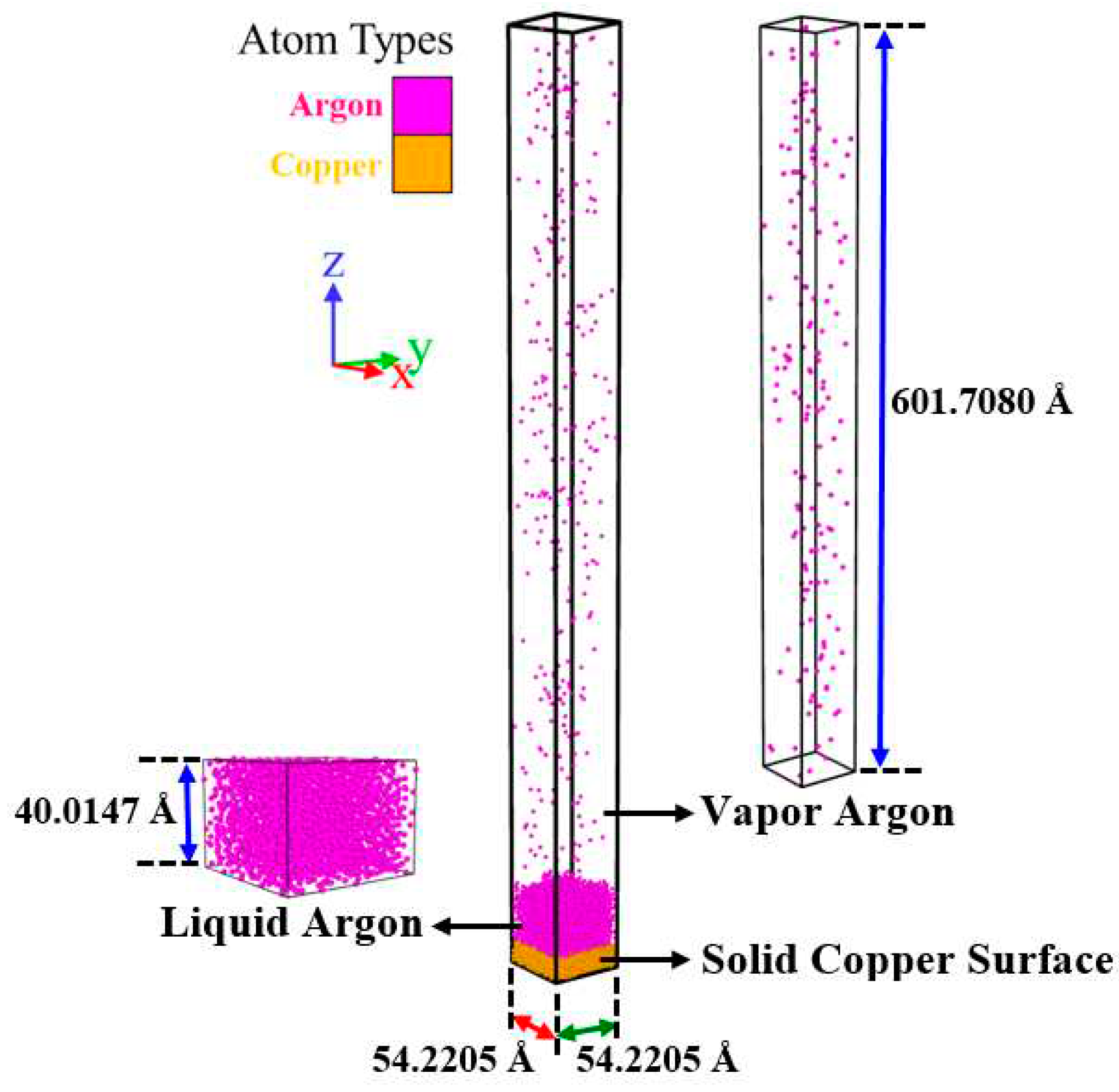

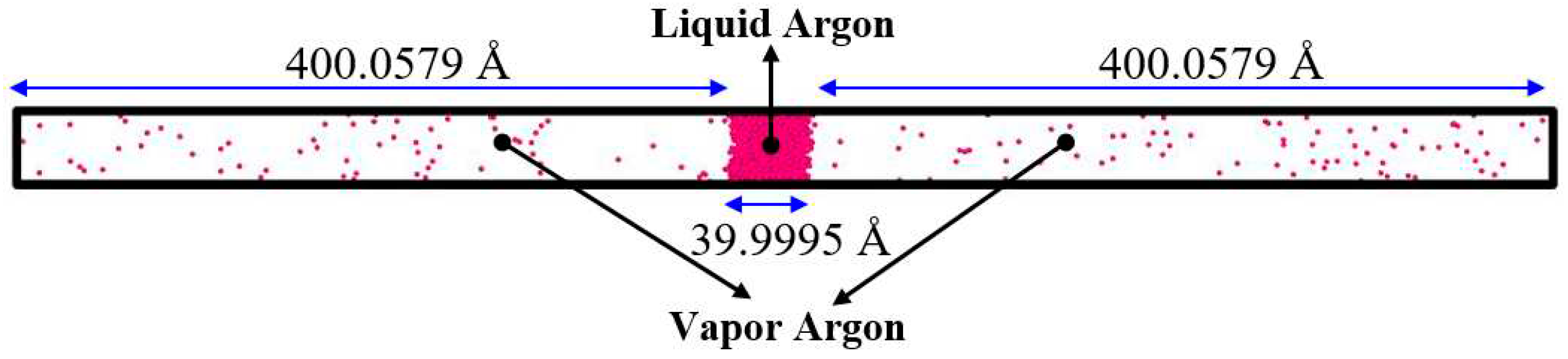

2.2.2. Simulation Boxes

2.3. Computational Runs

2.4. Post-Processing Analysis

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Model Validation

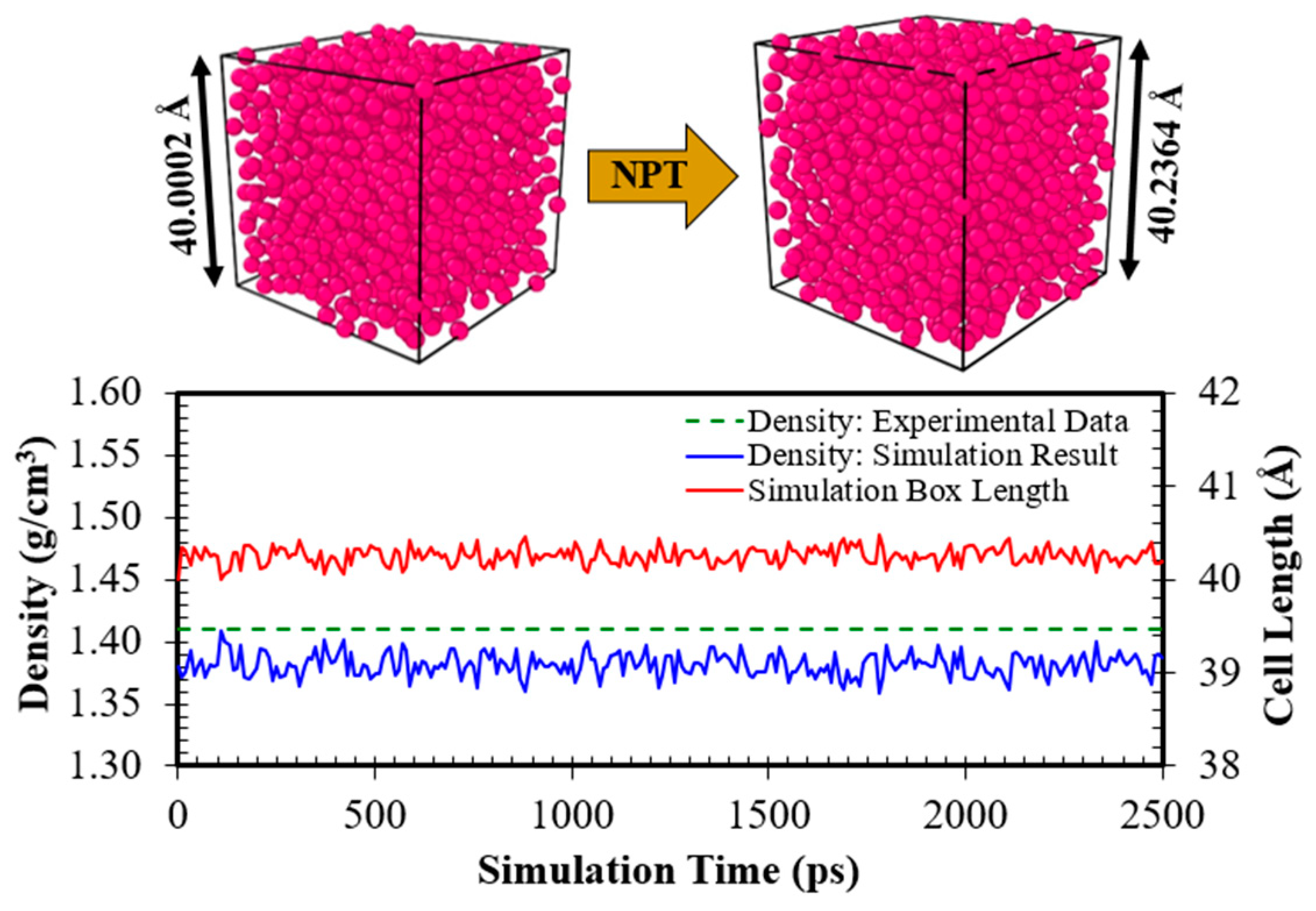

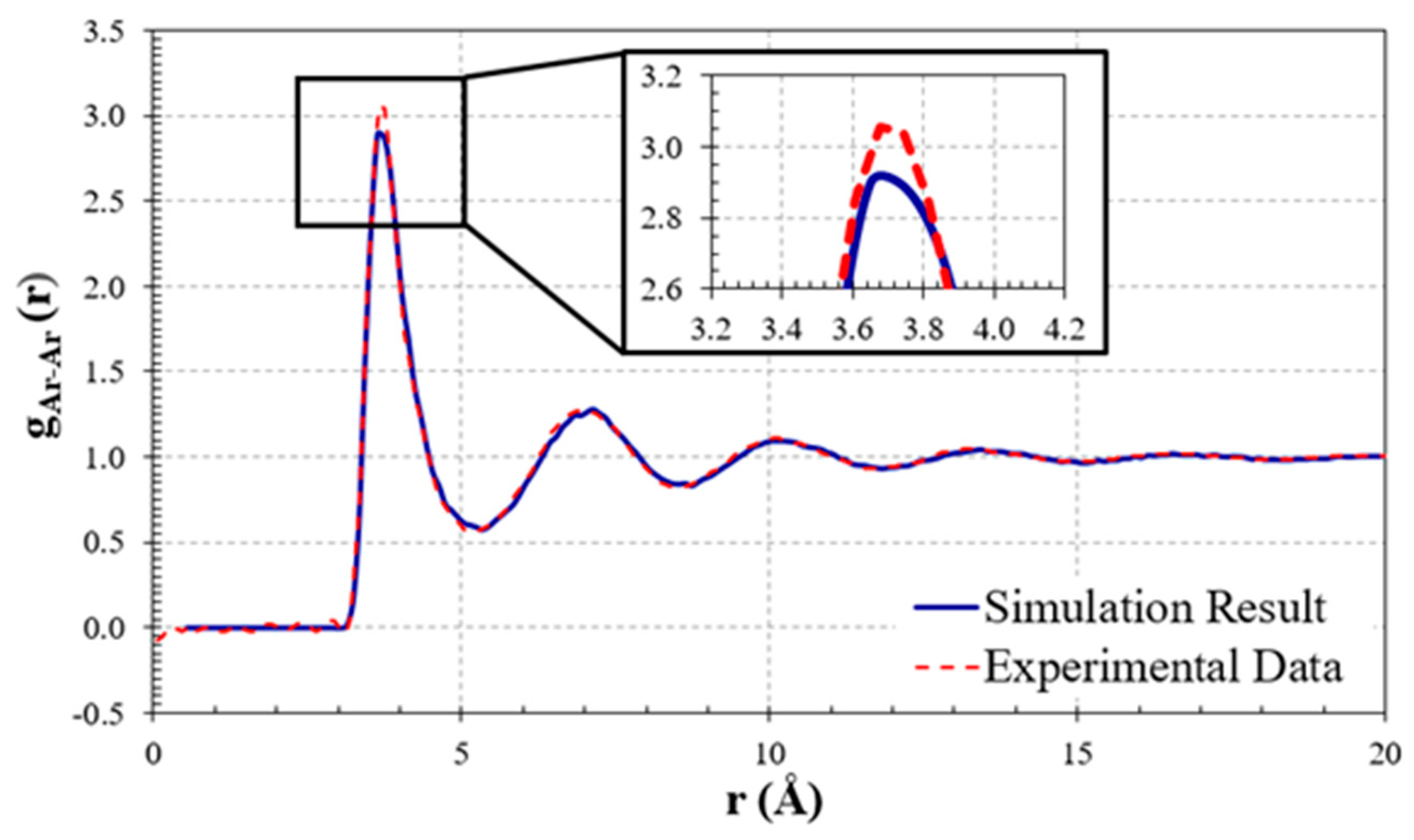

3.1.1. The Simulation Case I: The Liquid Argon System

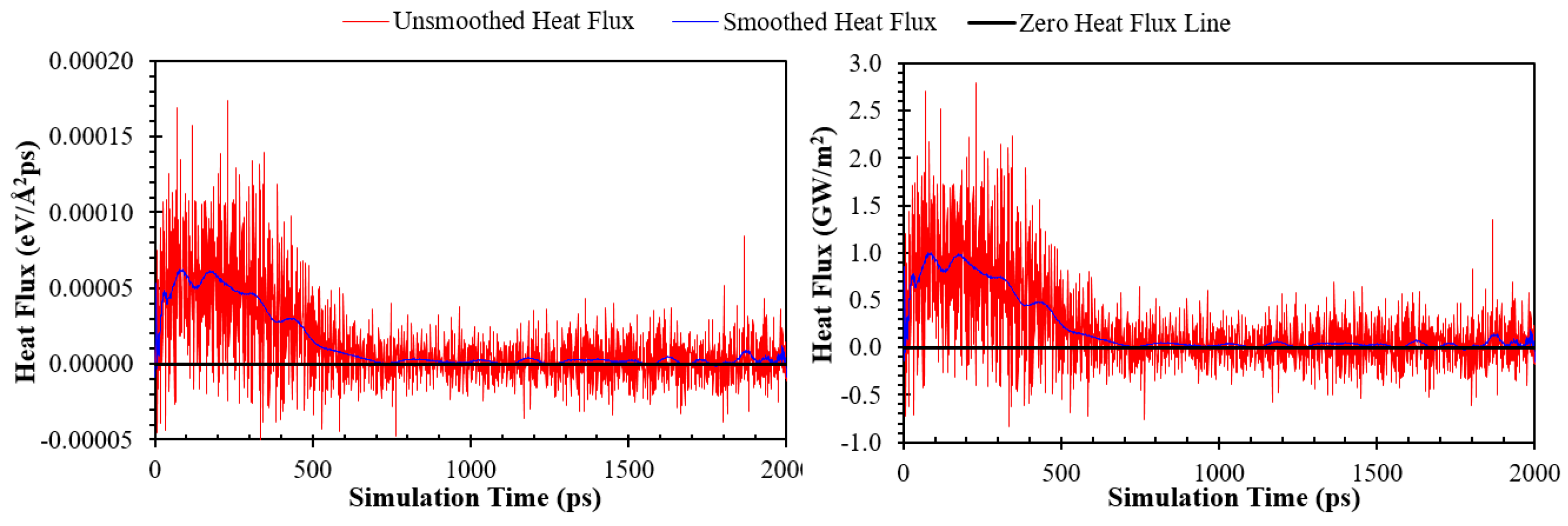

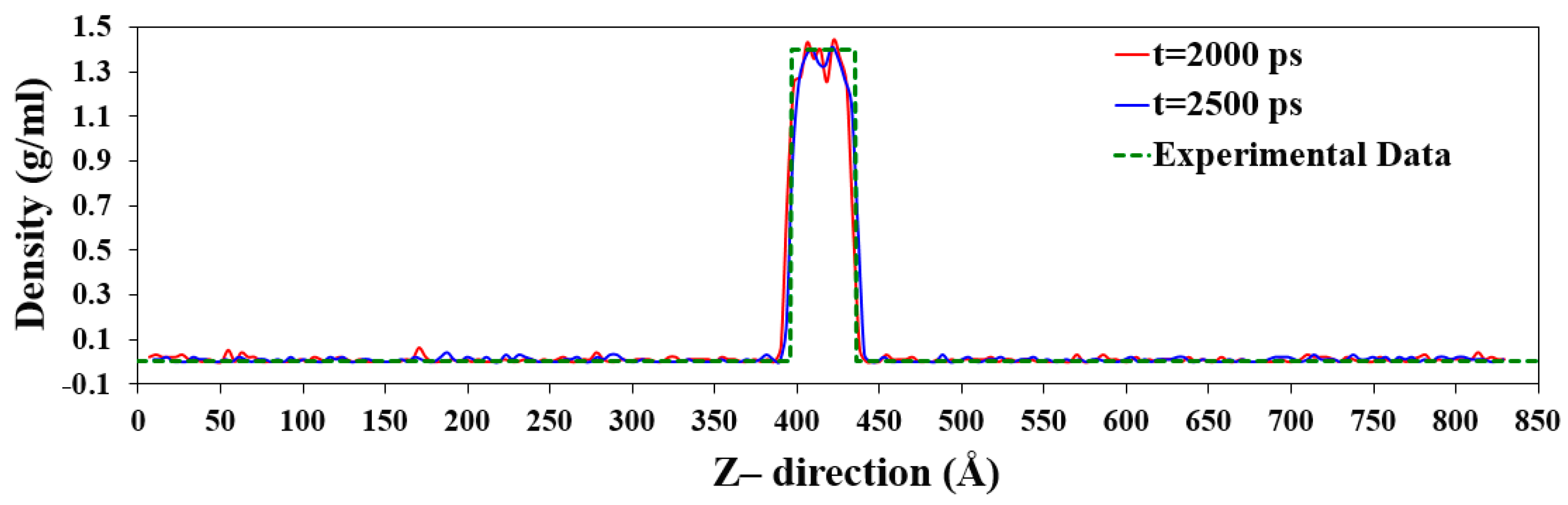

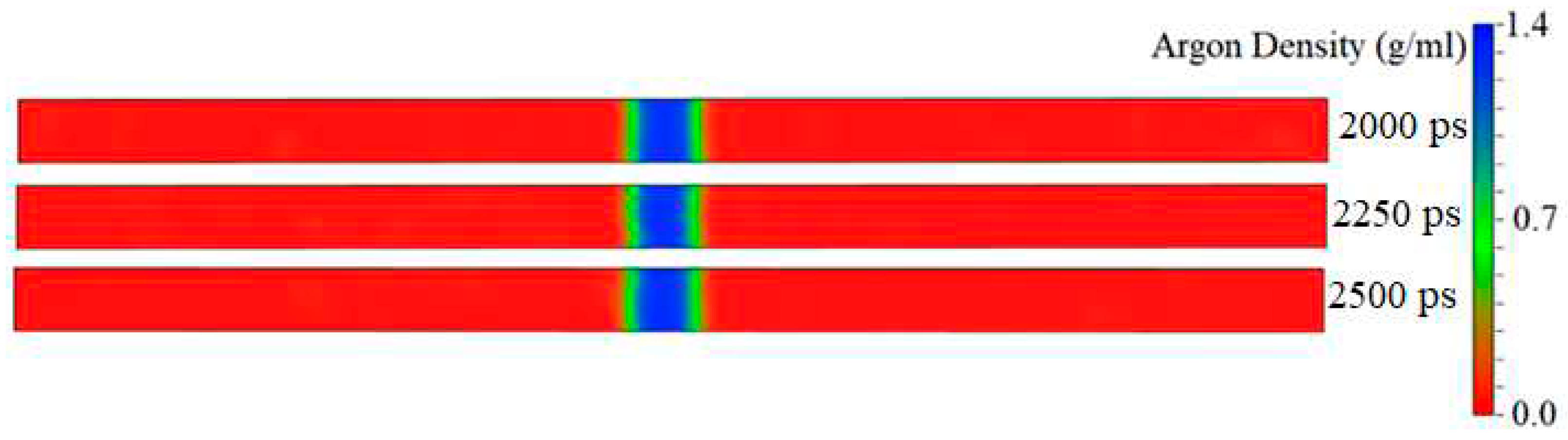

3.1.2. The Simulation Case II: The Liquid-Vapor Argon Coexistence System

3.1.3. The Simulation Case II: The Liquid-Vapor Argon Coexistence System

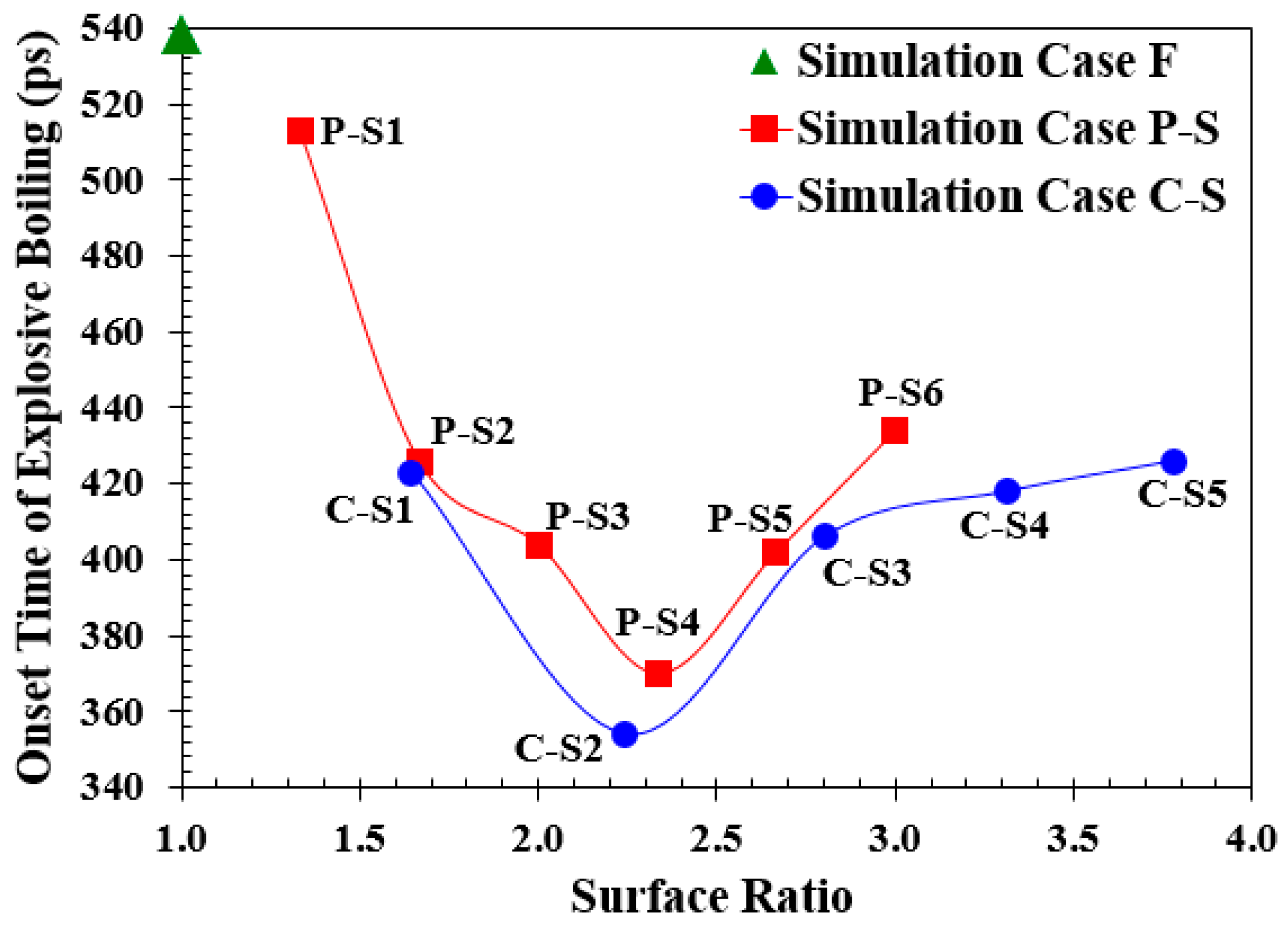

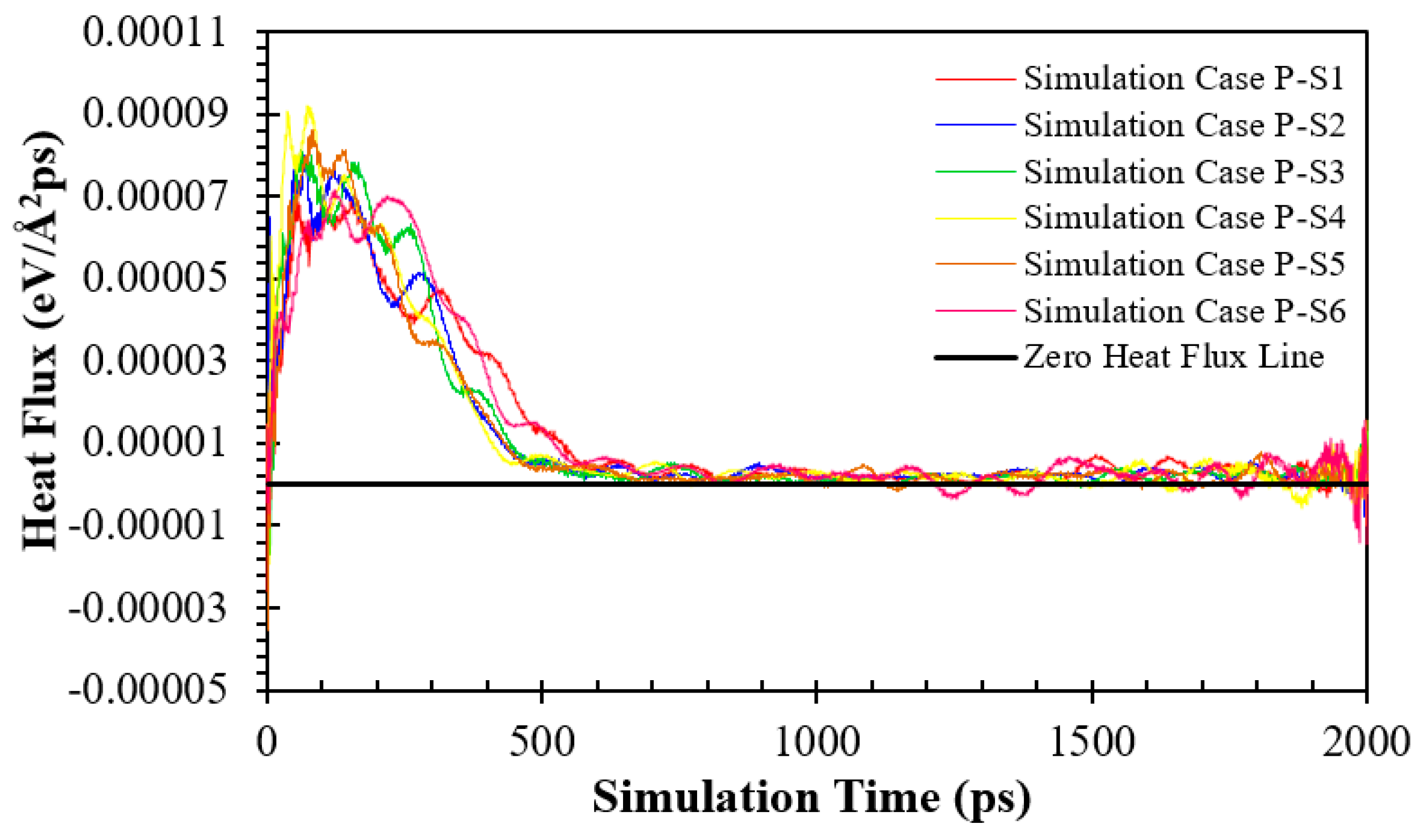

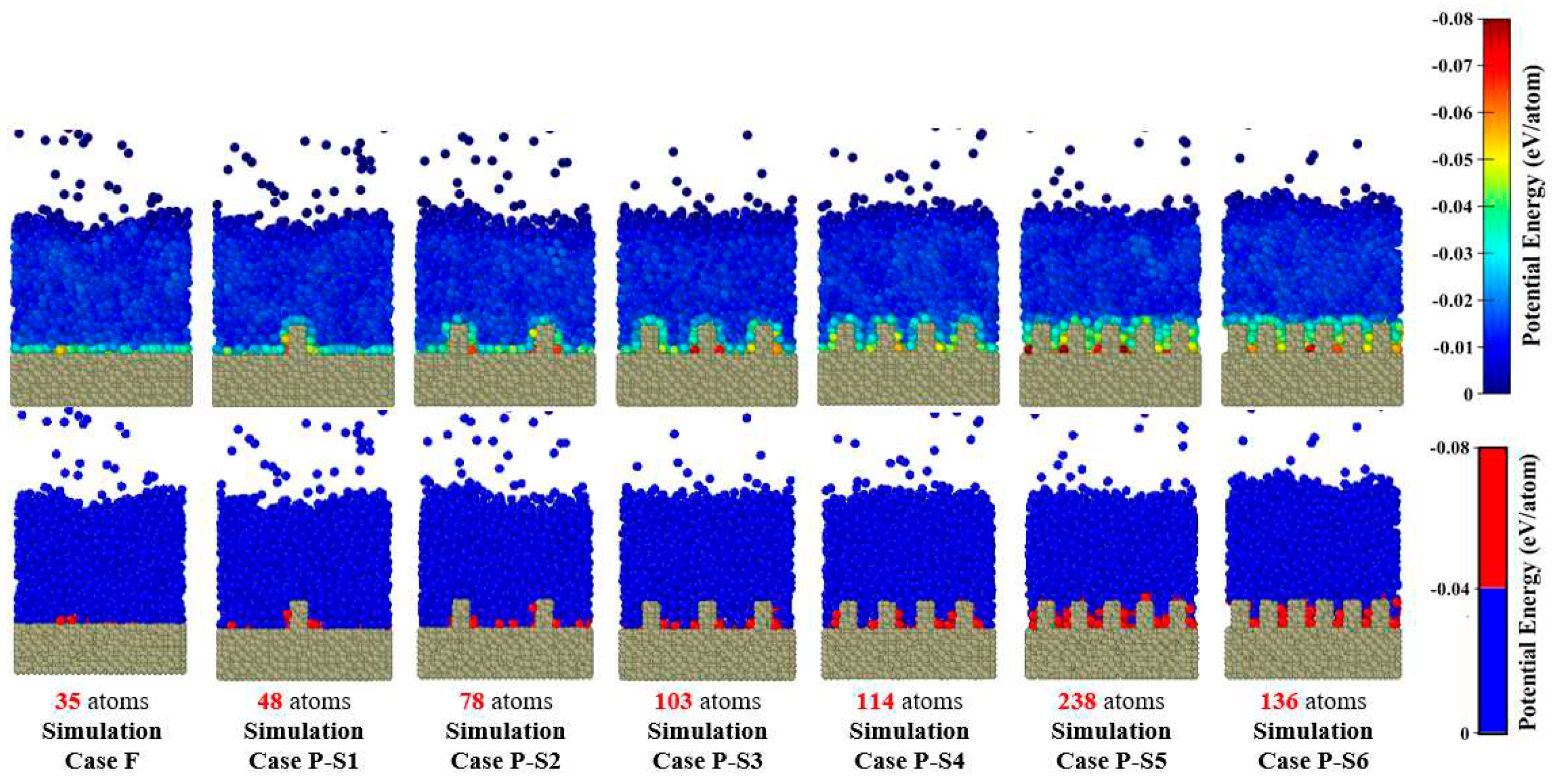

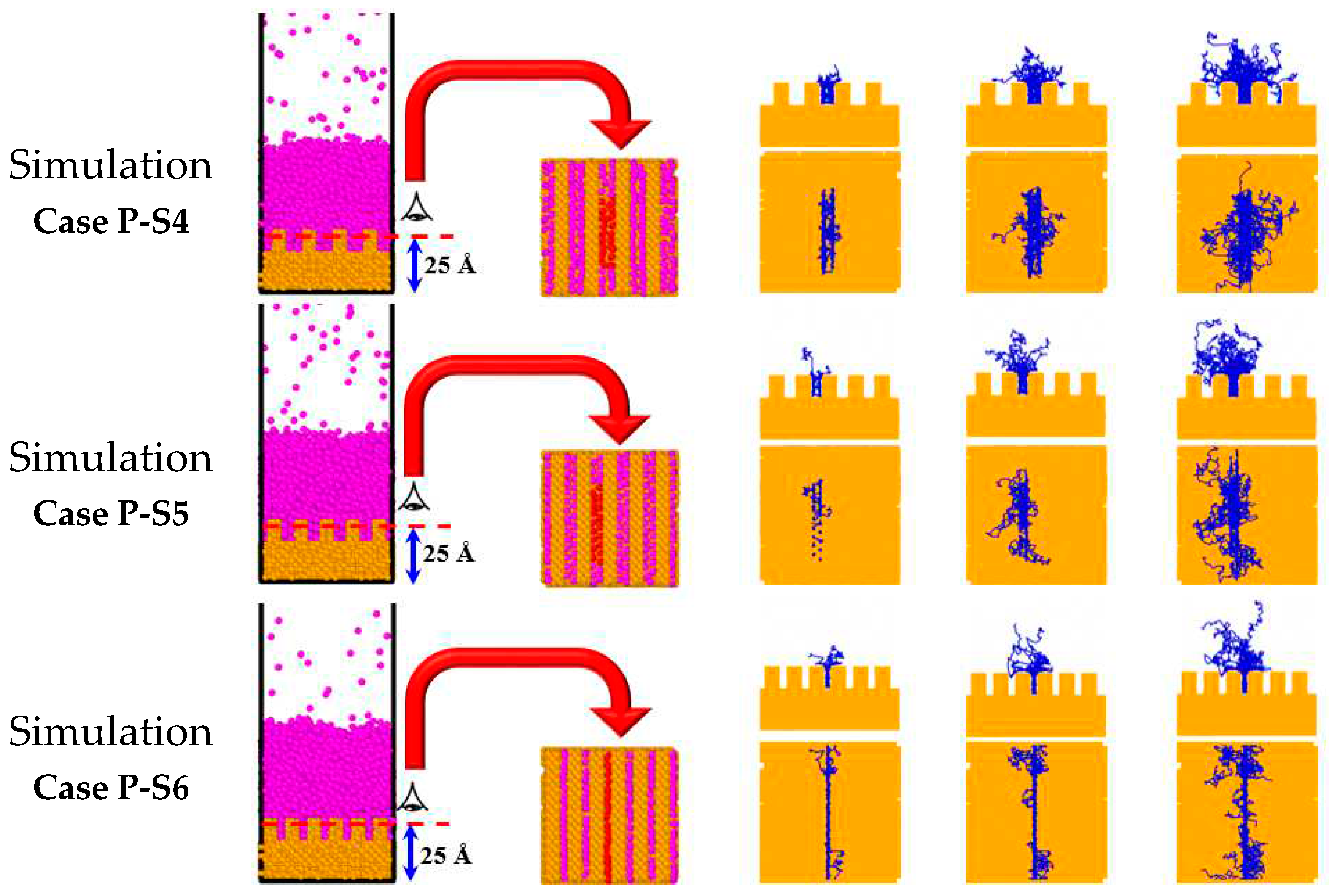

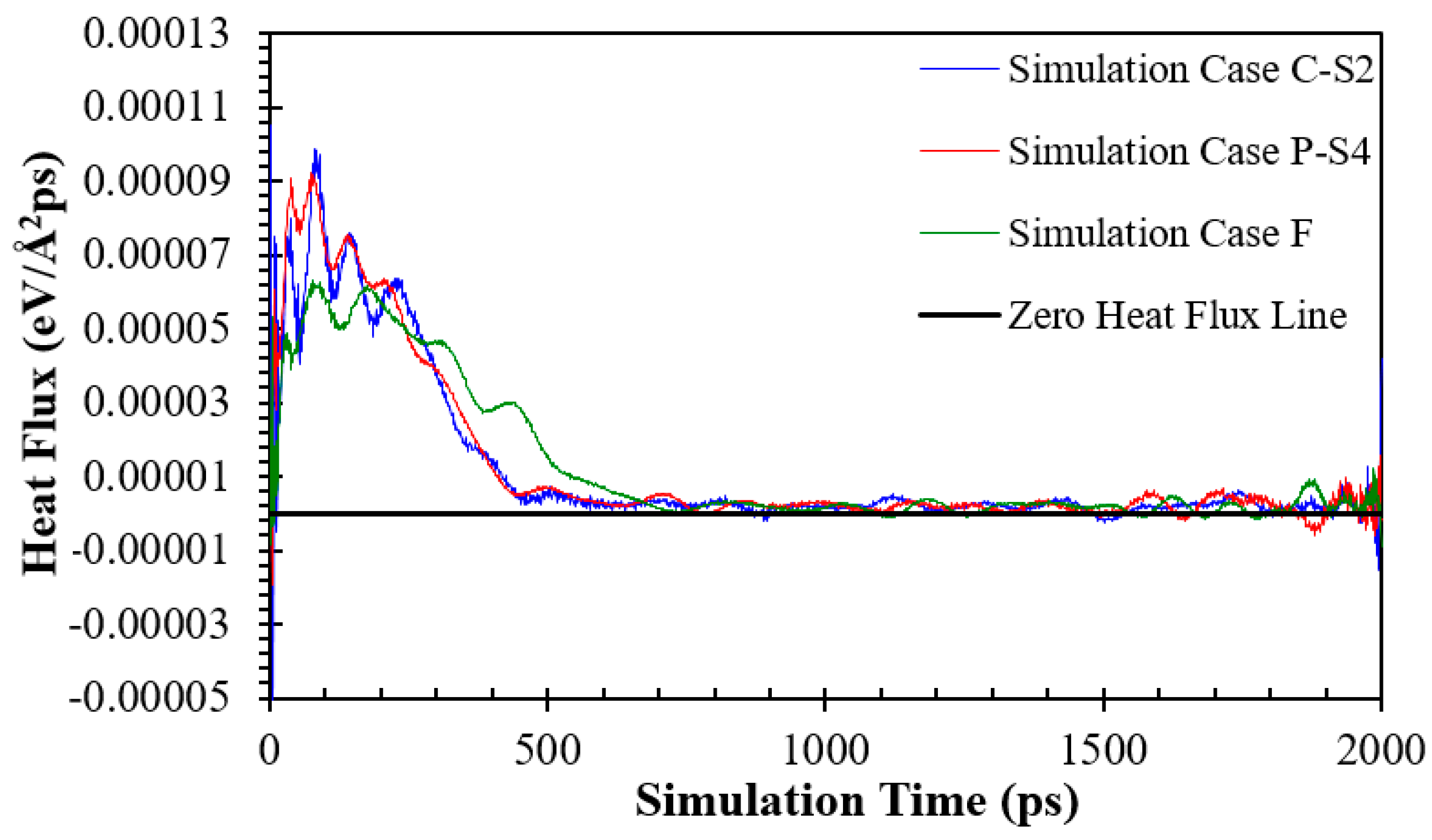

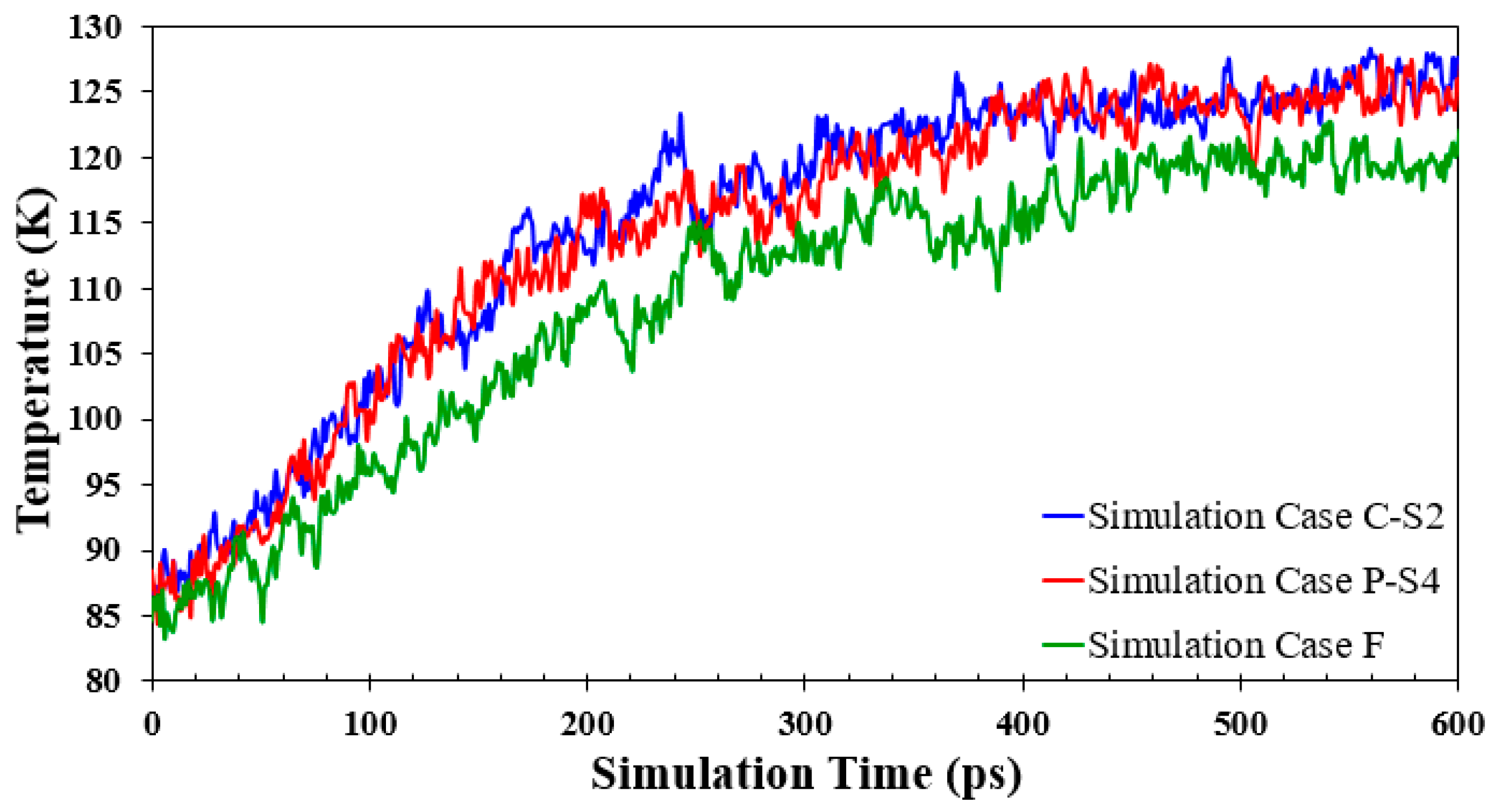

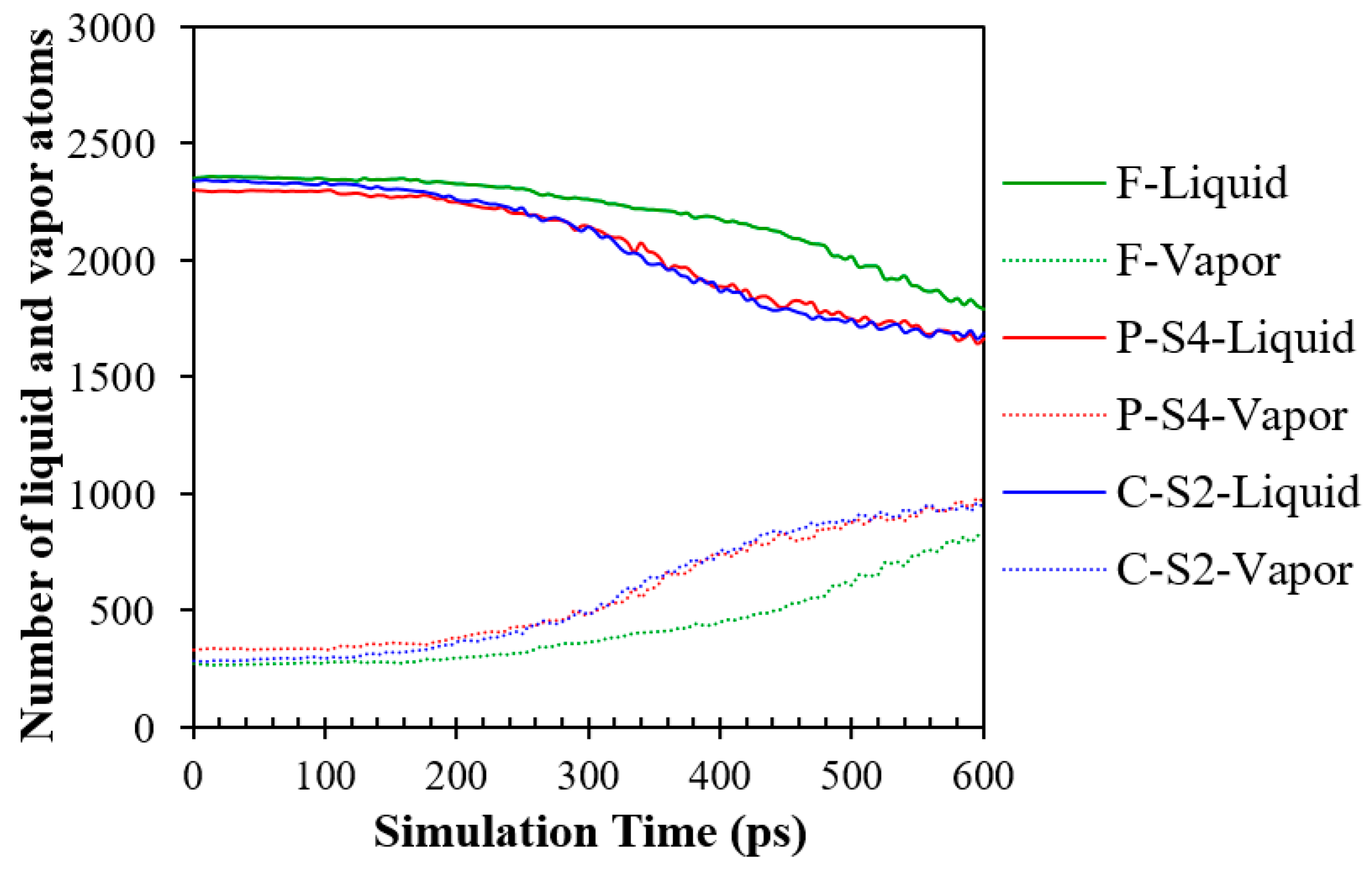

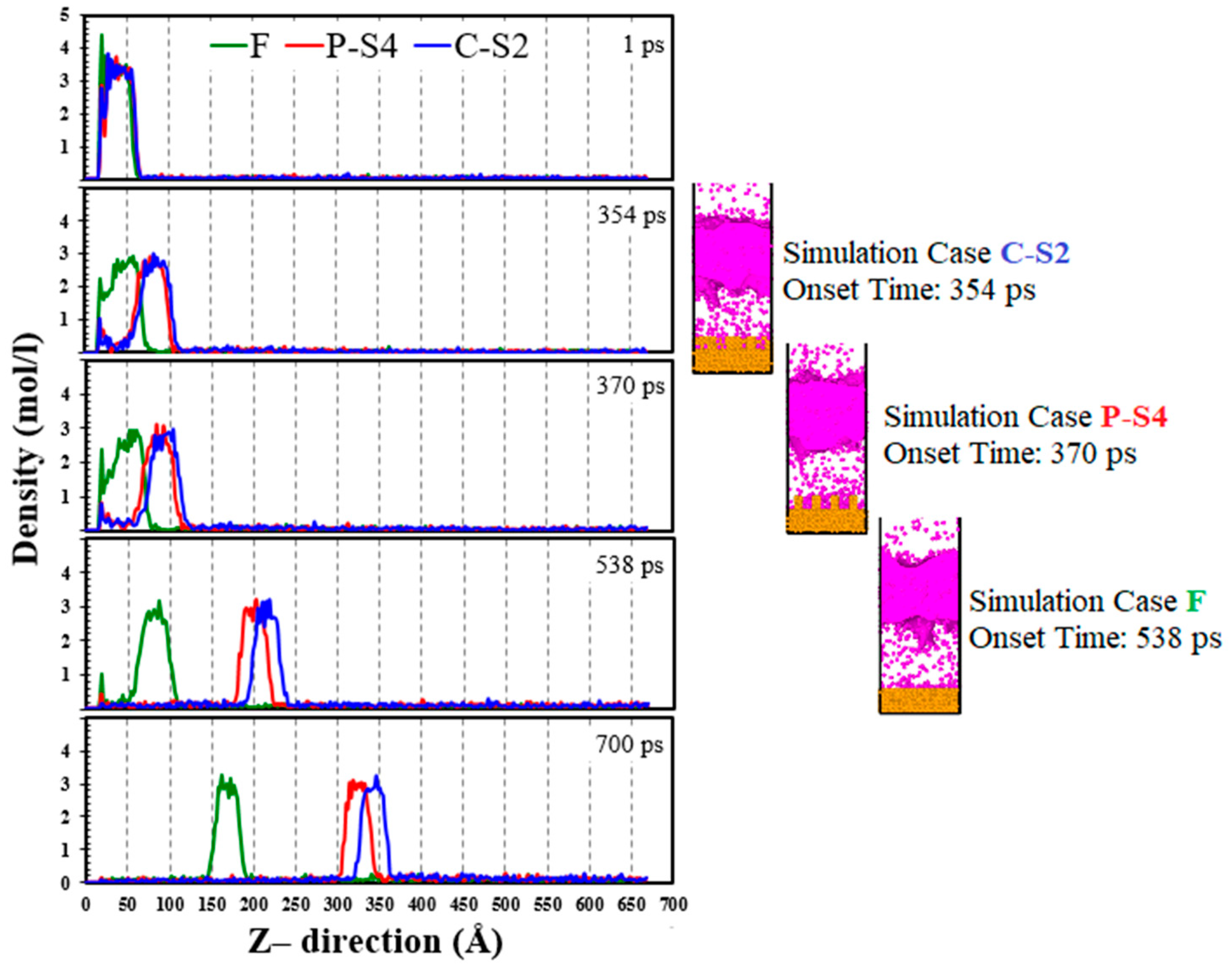

3.2. Simulation Cases A: Effects of Surface Topology and Spacing

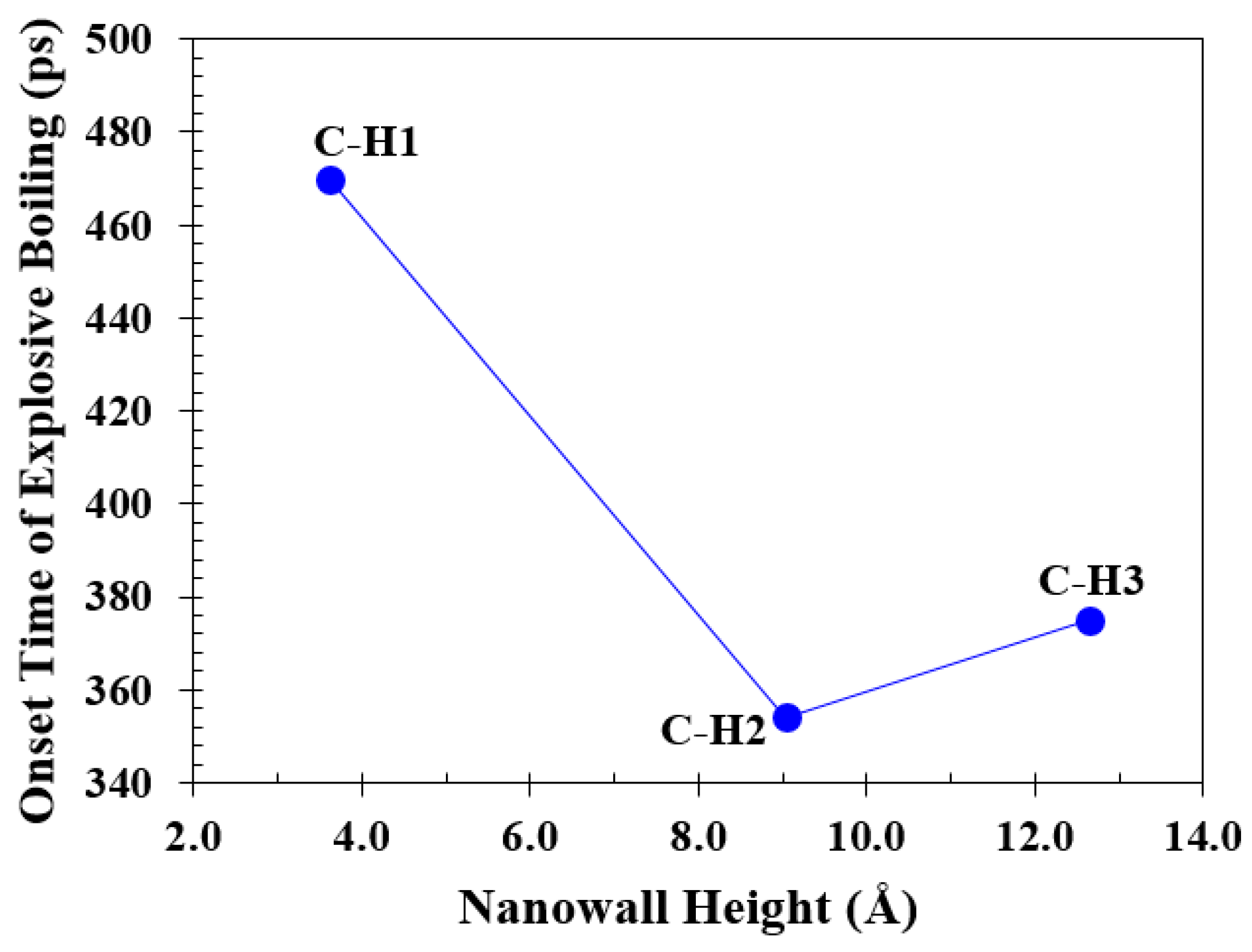

3.3. Simulation Cases B: Effects of Nanowall Height

4. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest Statement

Supplementary Materials

Nomenclature

| A | Nominal surface area | (Å2) |

| Å | Angstrom | - |

| d | Lattice constant | (Å) |

| E | Young’s Modules | (GPa) |

| Total energy of fluid atoms. | (eV) | |

| FCC | Face-centered-cubic | - |

| GW | Gigawatt | - |

| K | Spring constant | (eV/Å2) |

| L-J 12-6 | Lennard-Jones 12-6 | - |

| m | Meter | - |

| MDS | Molecular dynamics simulations | - |

| NVE | Microcanonical ensemble | - |

| NPT | Isothermal–isobaric ensemble | - |

| NVT | Canonical ensemble | - |

| OVITO | Open Visualization Tool | - |

| ps | Picosecond | - |

| q | Heat flux | (eV/Å2ps) |

| r | Distance between the particles | (Å) |

| RDF | Radial distribution function | - |

| t | Time | (ps) |

| T | Temperature | (K) |

| U | Potential energy | (eV) |

| Greek Symbols | ||

| Potential energy factor | ||

| Energy parameter for L-J 12-6 potential | (eV) | |

| Length parameter for L-J 12-6 potential | (Å) | |

| Subscripts | ||

| Ar | Argon | |

| Cu | Copper | |

| i | Particle i | |

| j | Particle j | |

References

- A.M. Morshed, T. C. Paul, J. A. Khan. Effect of nanostructures on evaporation and explosive boiling of thin liquid films: a molecular dynamics study. Applied Physics A 105 (2011) 445–451. [CrossRef]

- P. Bai, L. Zhou, X. Du. Effects of surface temperature and wettability on explosive boiling of nanoscale water film over copper plate. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 162 (2020) 120375. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mao, Y. Zhang. Molecular dynamics simulation on rapid boiling of water on a hot copper plate. Applied Thermal Engineering 62 (2014) 607–612. [CrossRef]

- M. Ilic, V. D. Stevanovic, S. Milivojevic, M. M. Petrovic. New insights into physics of explosive water boiling derived from molecular dynamics simulations. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 172 (2021) 121141. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tang, Y. He, L. Ma, X. Zhang, J. Xue. Molecular dynamics simulation of carbon nanotube-enhanced laser induced explosive boiling on a free surface of an ultrathin liquid film. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 127 (2018) 237–243. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Seyf, Y. Zhang. Molecular dynamics simulation of normal and explosive boiling on nanostructured surface. ASME Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 135 (2013) 121503. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Kudryashov, S. D. Allen. Photoacoustic study of explosive boiling of a 2-propanol layer of variable thickness on a KrF excimer laser-heated Si substrate. Journal of Applied Physics 95 (2004) 5820–5827. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Kudryashov, S. D. Allen. Submicron dynamics of water explosive boiling and lift-off from laser-heated silicon surfaces, Journal of Applied Physics 100 (2006) 104908. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, X. Qin, S. Ahmad, Q. Tong, J. Zhao. Molecular dynamics study about the effects of random surface roughness on nanoscale boiling process. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 145 (2019) 118799. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang, L. Zhou, L. Jin, H. Zhao, X. Du. Effect of nanostructures on rapid boiling of water films: a comparative study by molecular dynamics simulation. Applied Physics A 125 (2019) 142. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou, S. Li, S-Z Tang, D. Zhang, H. Tian. Effect of nanostructure on explosive boiling of thin liquid water film on a hot copper surface: a molecular dynamics study. Molecular Simulation 48 (2022) 221-230. [CrossRef]

- P. Bai, L. Zhou, X. Du. Molecular dynamics simulation of the roles of roughness ratio and surface potential energy in explosive boiling. Journal of Molecular Liquids 335 (2021) 116169. [CrossRef]

- P. Bai, L. Zhou, X. Du. Effects of liquid film thickness and surface roughness ratio on rapid boiling of water over copper plates. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer 120 (2021) 105036. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Seyf, Y. Zhang. Effect of nanotextured array of conical features on explosive boiling over a flat substrate: A nonequilibrium molecular dynamics study. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 66 (2013) 613–624. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, H. Zhang, C. Tian, X. Meng. Numerical experiments on evaporation and explosive boiling of ultra-thin liquid argon film on aluminum nanostructure substrate. Nanoscale Research Letters 158 (2015). [CrossRef]

- T. Fu, Y. Mao, Y. Tang, Y. Zhang, W. Yua. Effect of nanostructure on rapid boiling of water on a hot copper plate: a molecular dynamics study. Heat and Mass Transfer 52 (2016) 1469–1478. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, F. Hao, H. Chen, W. Yuan, Y. Tang, X. Chen. Molecular dynamics simulation on explosive boiling of liquid argon film on copper nanochannels. Applied Thermal Engineering 113 (2017) 208–214. [CrossRef]

- Qasemian, M. Qanbarian, B. Arab. Molecular dynamics simulation on explosive boiling of thin liquid argon films on cone-shaped Al–Cu-based nanostructures. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 145 (2021) 269–278. [CrossRef]

- M-J Liao, L-Q Duan. Explosive boiling of liquid argon films on flat and nanostructured surfaces. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications 78 (2020) 94-105. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, W. Deng, P. Ding, J. Zhao. Investigation of the effects of surface wettability and surface roughness on nanoscale boiling process using molecular dynamics simulation. Nuclear Engineering and Design 382 (2021) 111400. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, S. Qian, Z. Zhang. Investigation of the aggregation morphology of nanoparticle on the thermal conductivity of nanofluid by molecular dynamics simulations. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 127 (2018) 1138–1146. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, X. Xu, J. Liu, Y. Liu, W. Cai, J. Chen. The study of water wettability on solid surfaces by molecular dynamics simulation. Surface Science 714 (2021) 121916. [CrossRef]

- C. Hu, L. Shi, C. Yi, M. Bai, Y. Li, D. Tang. Mechanism of enhanced phase-change process on structured surface: Evolution of solid-liquid-gas interface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 205 (2023) 123915. [CrossRef]

- X. Yin, C. Hu, M. Bai, J. Lv. An investigation on the heat transfer characteristics of nanofluids in flow boiling by molecular dynamics simulations. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 162 (2020) 120338. [CrossRef]

- Paula Leite, R. and M. de Koning, Nonequilibrium free-energy calculations of fluids using LAMMPS. Computational Materials Science 159 (2019) 316–326. Available online: https://lammps.sandia.gov. [CrossRef]

- Stukowski. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVIT- the Open Visualization Tool. Modelling and Simulation in Materials Science and Engineering 18 (2010) 015012. Available online: http://ovito.sourceforge.net/. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, J. Li, B. Yu, D. Sun, Y. Zou, D. Han. Nanoscale Study of Bubble Nucleation on a Cavity Substrate Using Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Langmuir 34 (2018) 14234−14248. [CrossRef]

- M. Zarringhalam, H. Ahmadi-Danesh-Ashtiani, D. Toghraie, R. Fazaeli. Molecular dynamic simulation to study the effects of roughness elements with cone geometry on the boiling flow inside a microchannel. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 141 (2019) 1–8. [CrossRef]

- J. Delhommelle, P. Millié. Molecular physics: an international journal at the interface between chemistry and physics. Molecular physics 99 (2001) 619–625. [CrossRef]

- X.D. Din, E.E. Michaelides. Kinetic theory and molecular dynamics simulations of microscopic flows. Physics of Fluids 9 (1997) 3915–3925. [CrossRef]

- Hens, R. Agarwal, G. Biswas. Nanoscale study of boiling and evaporation in a liquid Ar film on a Pt heater using molecular dynamics simulation. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 71 (2014) 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, Y. Zou, D. Sun, Y. Wang, B. Yu. Molecular dynamics simulation of bubble nucleation on nanostructure surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 118 (2018) 1143–1151. [CrossRef]

- R.P. Reed, A. F. Clark. Materials at low temperatures. American Society for Metals, 1983. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu, Y. Sun. Effect of nanopatterns on Kapitza resistance at a water-gold interface during boiling: A molecular dynamics study. Journal of Applied Physics 112, 053508 (2012). [CrossRef]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database, NIST Chemistry WebBook. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hea, S. Wanga, Y. Tanga, Z. Wub, W. Li. Molecular dynamics simulation on liquid nanofilm boiling over vibrating surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 201 (2023) 123617. [CrossRef]

- X. Deng, X. Xu, X. Song, Q. Li, C. Liu. Boiling heat transfer of CO2/lubricant on structured surfaces using molecular dynamics simulations. Applied Thermal Engineering 219 (2023) 119682. [CrossRef]

- P.R. ten Wolde, D. Frenkel. Computer simulation study of gas–liquid nucleation in a Lennard-Jones system. The Journal of Chemical Physics 109 (1998) 9901. [CrossRef]

- J. Wedekinda, D. Reguera. What is the best definition of a liquid cluster at the molecular scale. The Journal of Chemical Physics 127 (2007) 154516. [CrossRef]

- M. Ilic, V. D. Stevanovic, S. Milivojevic, M. M. Petrovic. Explosive boiling of water films based on molecular dynamics simulations: Effects of film thickness and substrate temperature. Applied Thermal Engineering 220 (2023) 119749. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Yarnell, M.J. Katz, R.G. Wenzel, S.H. Koenig. Structure factor and radial distribution function for liquid argon at 85 °K. Physical Review A 7 (1973) 2130–2144. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, S. Ahmad, J. Chen, J. Zhao. Molecular dynamics study of the nanoscale boiling heat transfer process on nanostructured surfaces. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 191 (2022) 122848. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

||||

| Spherical nanopillar | Cylindrical nanopillar | Conical nanopillar | ||||

|

|

|||||

| Cubical nanopillar | Cubical nanowall | |||||

| Study | Boiling Mode | Mediums of Fluid / Solid | Nanostructure | Substrate Temperature (K) |

||

| Topology (Shape) | Configuration (Size)* | |||||

| Morshed et al. [1] | Normal / Explosive | Argon/ Platinum |

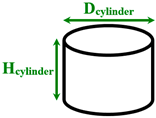

Separated cylindrical nanopillars | Dcylinder= 1.013 Hcylinder= 1.754–4.782 |

130 and 300 | |

| Seyf and Zhang [6] | Normal / Explosive | Argon / Copper |

Separated spherical nanopillars | Dsphere=1–3 | 170 and 290 | |

| Seyf and Zhang [14] | Explosive | Argon / Aluminum and Silver |

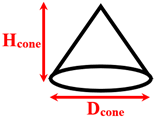

Separated conical nanopillars | Dcone= 1 Hcone= 2–5 |

270 | |

| Wang et al. [15] | Normal / Explosive | Argon / Aluminum |

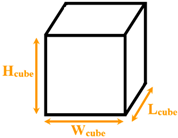

Separated cubical nanopillars | Wcube= 1.8 Lcube= 1.8 Hcube= 1.8225–4.455 |

150 and 310 | |

| Fu et al. [16] | Explosive | Water / Copper |

Separated cubical nanopillars | Wcube= 1.444–2.166 Lcube= 1.444–2.166 Hcube= 1.444–2.166 |

1000 | |

| Zhang et al. [17] | Explosive | Argon / Copper |

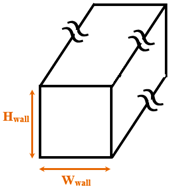

Parallel cubical nanowalls | Wwall= 1.808 Hwall= 1.266–3.434 |

350 | |

| Liu et al. [9] | Explosive | Argon / Copper |

Random roughness surface | – | 300 | |

| Zhang et al. [10] | Explosive | Water / Copper |

Separated cubical nanopillars | Wcube= 1.444 Lcube= 1.444 Hcube= 1.444 |

800 | |

| Liao and Duan [19] | Explosive | Argon / Gold |

Parallel cubical nanowalls | Wwall= 0.612 Hwall= 0.816-2.040 |

120-240 | |

| Liu et al. [20] | Explosive | Argon / Copper |

Random roughness surface | – | 300 | |

| Qasemian et al. [18] | Explosive | Argon / Aluminum and Copper |

Separated conical nanopillars | Dcone= 2.8 Hcone= 2 |

350 | |

| Zhou et al. [11] | Explosive | Water / Copper |

Separated spherical and cylindrical nanopillars | Dsphere=1–1.44 Dcylinder=6 Hcylinder=1.8 |

1000 | |

| Atom pairs | (Å) | (eV) |

| Cu-Cu | 1.9297 | 0.2047 |

| Ar-Ar | 3.4050 | 0.0104 |

| Ar-Cu | 2.6674 | 0.0065 |

|

|

|

|

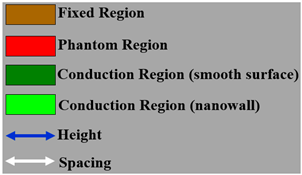

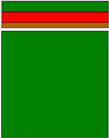

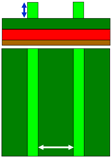

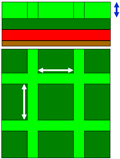

| Surface F | Surface P | Surface C | |

| The top and side schematic views of different copper surface topologies. | |||

| Simulation Case1 | Spacing (Å) | Height (Å) | Surface ratio2 |

| 1. Simulation Cases A: Different topologies with different Spacing: | |||

| F | – | – | 1 |

| P-S1 | 50.6058 | 9.0368 | 1.3333 |

| P-S2 | 23.4956 | 1.6667 | |

| P-S3 | 14.4588 | 2.0000 | |

| P-S4 | 9.0368 | 2.3333 | |

| P-S5 | 7.2294 | 2.6667 | |

| P-S6 | 5.4220 | 3.0000 | |

| C-S1 | 50.6058 | 1.6444 | |

| C-S2 | 23.4956 | 2.2445 | |

| C-S3 | 14.4588 | 2.8000 | |

| C-S4 | 9.0368 | 3.3111 | |

| C-S5 | 7.2294 | 3.7778 | |

| F | – | 1 | |

| P-S1 | 50.6058 | 1.3333 | |

| 2. Simulation Cases B: Cross nanowall surfaces with different Heights: | |||

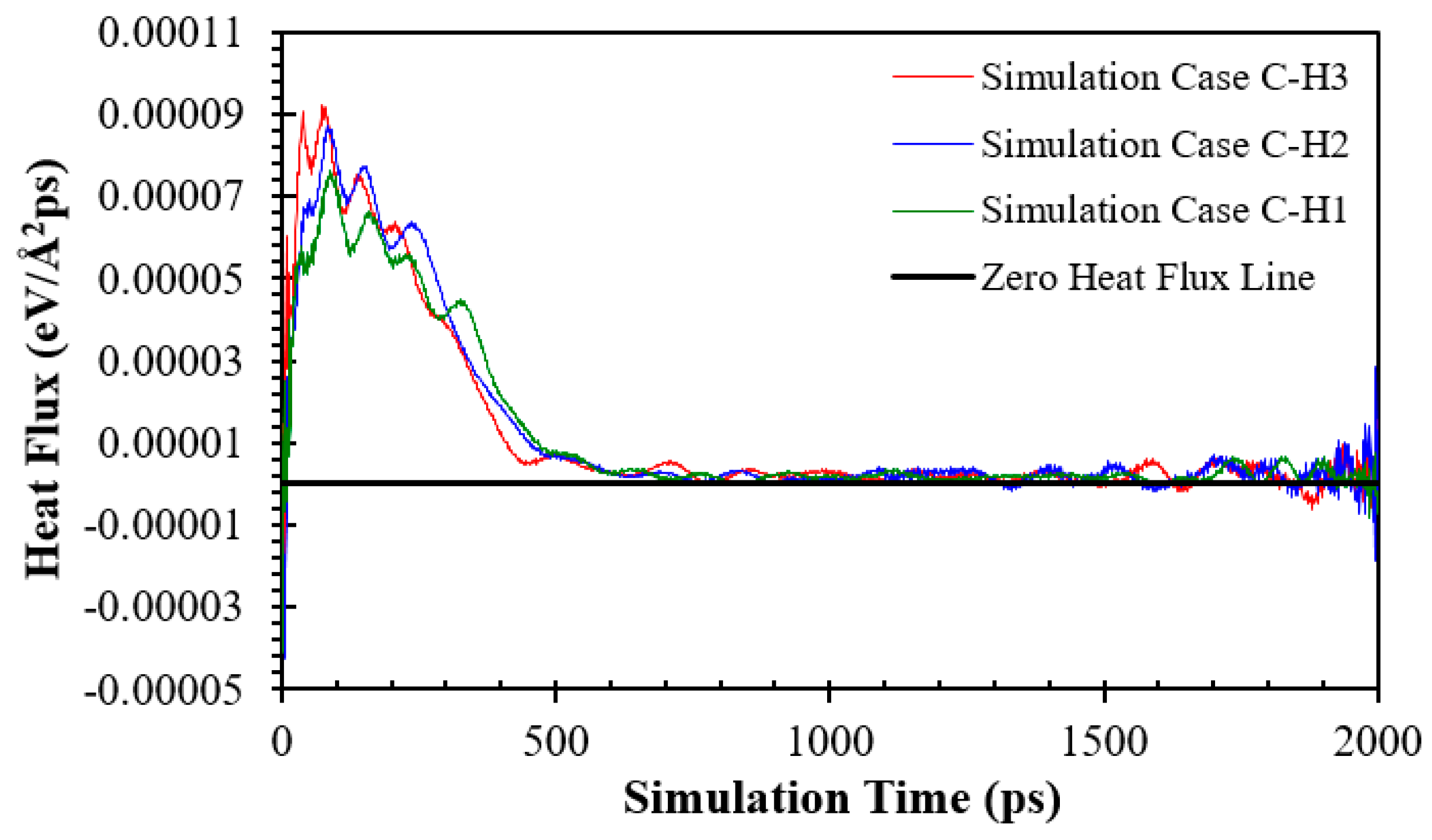

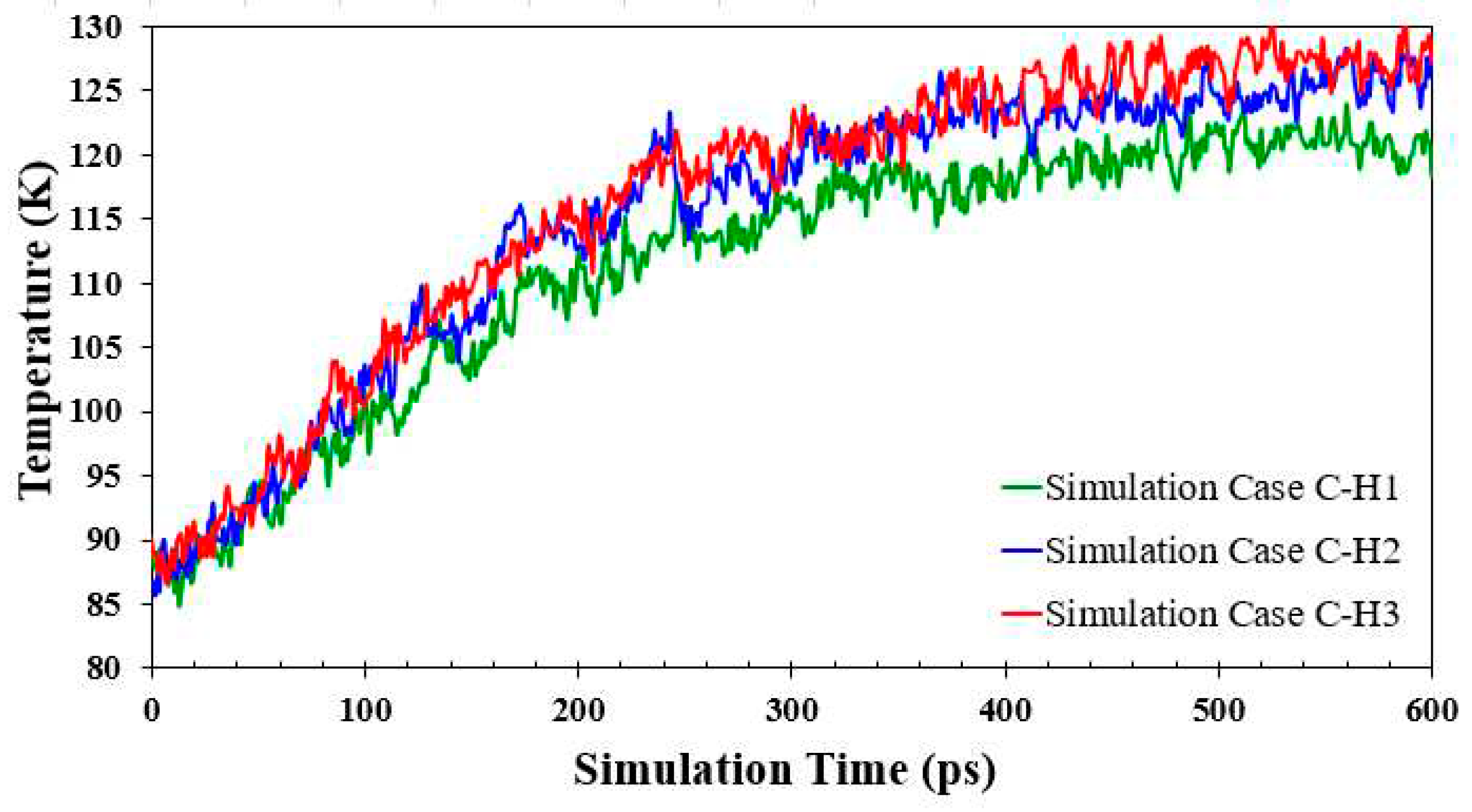

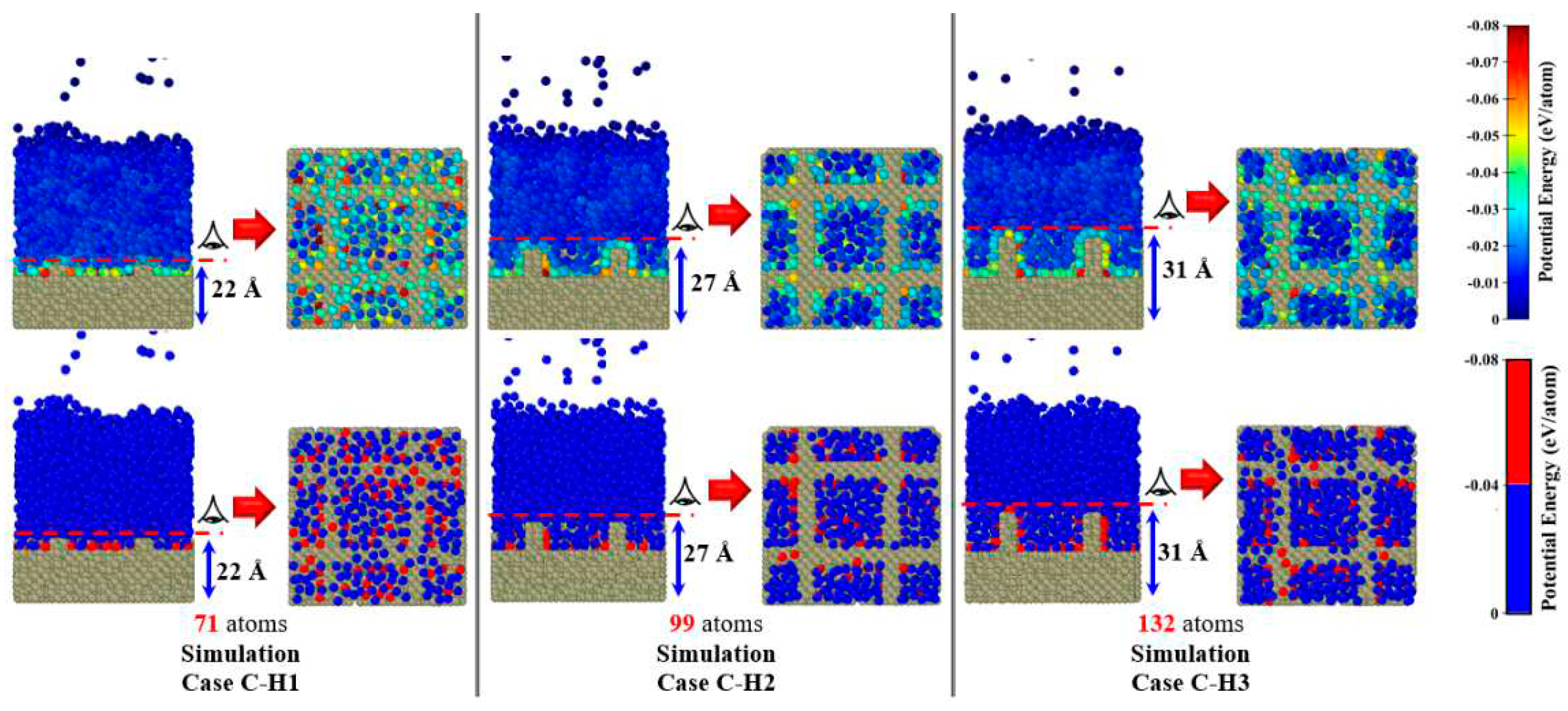

| C-H1 | 23.4956 | 3.6147 | 1.4978 |

| C-H2 | 9.0368 | 2.2445 | |

| C-H3 | 12.6515 | 2.7422 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).