Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

18 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data: Eye-gaze trajectories and ADHD cognitive test

2.2. Lévy-flights and superdiffusion

2.3. Machine learning classification methods

2.3.1. Logistic regression

2.3.2. Support Vector Machines

2.3.3. Decision Trees and Random Forests

3. Results: Lévy-flight exponents classify ADHD children

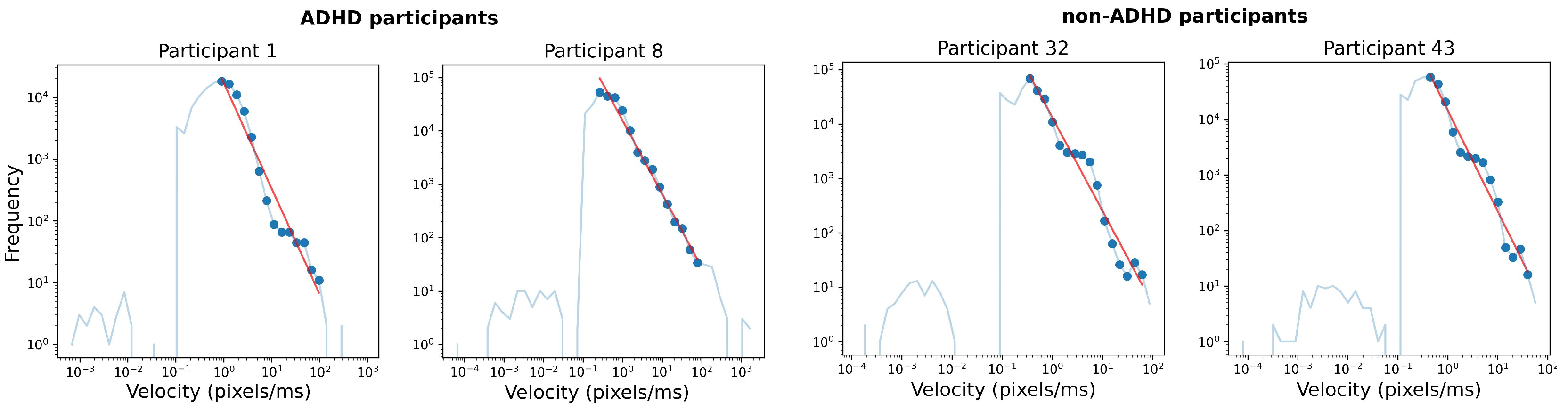

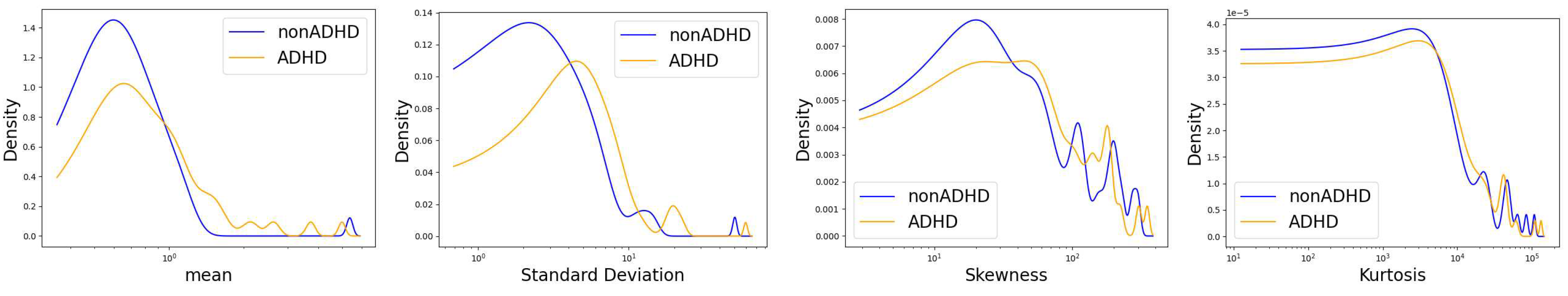

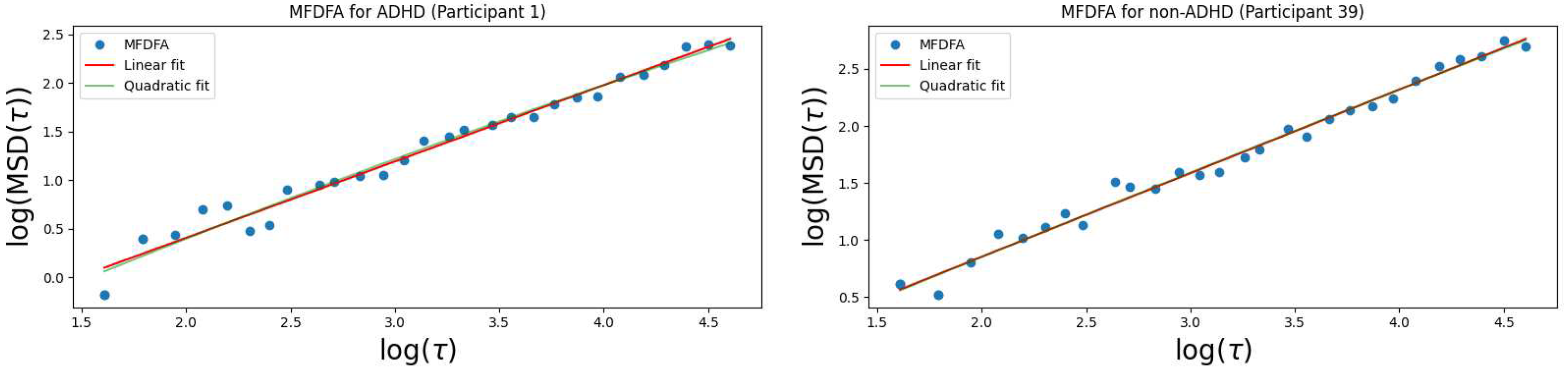

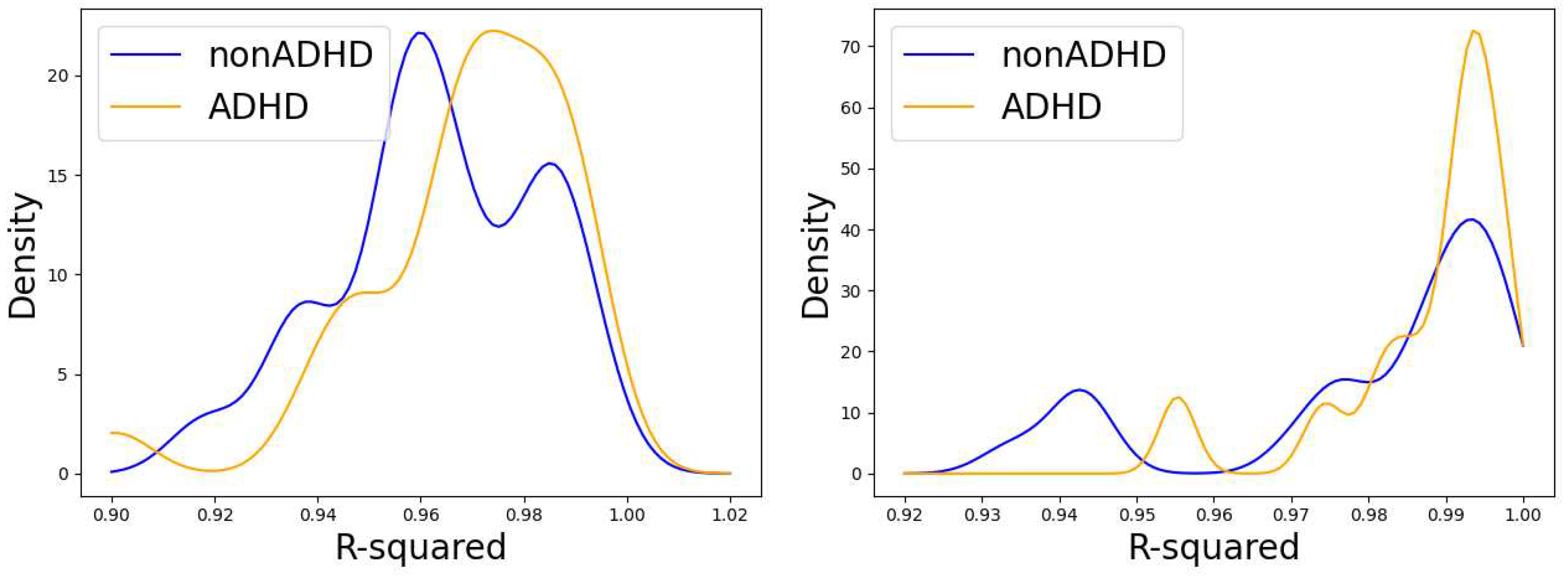

3.1. Eye-gaze dynamics and the Lévy-flight exponent

3.2. Classifying ADHD without eye-tracking

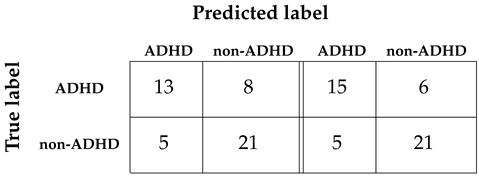

3.3. Classifying ADHD with eye-tracking

4. Conclusions

References

- Lencastre, P.; Bhurtel, S.; Yazidi, A.; e Mello, G.B.; Denysov, S.; Lind, P.G. EyeT4Empathy: Dataset of foraging for visual information, gaze typing and empathy assessment. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Sugiuchi, Y.; Na, J.; Shinoda, Y. Brainstem circuits triggering saccades and fixation. Journal of Neuroscience 2022, 42, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubkov, A.A.; Spagnolo, B.; Uchaikin, V.V. Lévy flight superdiffusion: an introduction. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 2008, 18, 2649–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T.; Kello, C.T.; Kerster, B. Intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to heavy tails in visual foraging. Visual Cognition 2014, 22, 809–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażejczyk, P.; Magdziarz, M. Stochastic modeling of Lévy-like human eye movements. Chaos 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, D.; Geisel, T. The ecology of gaze shifts. Neurocomputing 2000, 32-33, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccignone, G.; Ferraro, M. Modelling gaze shift as a constrained random walk. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2004, 331, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, G.M.; Raposo, E.; Da Luz, M. Lévy flights and superdiffusion in the context of biological encounters and random searches. Physics of Life Reviews 2008, 5, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, G.; Rabani, A.; Benisty, S.; Partridge, J.; Harshey, R.; Be’Er, A. Swarming bacteria migrate by Lévy Walk. Nature communications 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.F.; Ye, D.Y. Improved bacterial foraging optimization algorithm based on Levy flight. Computer System & Applications 2015, 24, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, G.; Afanasyev, V.; Buldyrev, S.; Murphy, E.; Prince, P.; Stanley, E. Lévy flight search patterns of wandering albatrosses. Nature 1996, 381, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.; Humphries, N.; Bradford, R.; Bruce, B. Lévy flight and Brownian search patterns of a free-ranging predator reflect different prey field characteristics. Journal of Animal Ecology 2012, 81, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, I.; Shin, M.; Hong, S.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.; Chong, S. On the levy-walk nature of human mobility. IEEE/ACM transactions on networking 2011, 19, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, F.; Baronchelli, A.; Amaral, L.A. Rationality, irrationality and escalating behavior in lowest unique bid auctions. PloS one 2012, 7, e29910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T.; Turvey, M.T. Human memory retrieval as Lévy foraging. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2007, 385, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credidio, H.; Teixeira, E.; Reis, S.; et al. Statistical patterns of visual search for hidden objects. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénichou, O.; Loverdo, C.; Moreau, M.; Voituriez, R. Intermittent search strategies. Reviews of Modern Physics 2011, 83, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, G.M.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Havlin, S.; Da Luz, M.; Raposo, E.; Stanley, H.E. Optimizing the success of random searches. nature 1999, 401, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, D.W.; Southall, E.J.; Humphries, N.E.; Hays, G.C.; Bradshaw, C.J.; Pitchford, J.W.; James, A.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Brierley, A.S.; Hindell, M.A.; others. Scaling laws of marine predator search behaviour. Nature 2008, 451, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröger, J.L.; Lutz, O.H.M.; Müller, F. What does your gaze reveal about you? On the privacy implications of eye tracking. IFIP International Summer School on Privacy and Identity Management. Springer, 2019, pp. 226–241.

- Berkovsky, S.; Taib, R.; Koprinska, I.; Wang, E.; Zeng, Y.; Li, J.; Kleitman, S. Detecting personality traits using eye-tracking data. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2019, pp. 1–12.

- Kasneci, E.; Kasneci, G.; Appel, T.; Haug, J.; Wortha, F.; Tibus, M.; Trautwein, U.; Gerjets, P. TüEyeQ, a rich IQ test performance data set with eye movement, educational and socio-demographic information. Scientific Data 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, J.G.; Cosnard, A.; Laurens, B.; Asselineau, J.; Biotti, D.; Cubizolle, S.; Dupouy, S.; Formaglio, M.; Koric, L.; Seassau, M.; others. Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease demonstrates increased errors at a simple and automated anti-saccade task. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease 2018, 65, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhera, T.; Kakkar, D. Eye Tracker: An Assistive Tool in Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Emerging Trends in the Diagnosis and Intervention of Neurodevelopmental Disorders; IGI Global, 2019; pp. 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, T.E. The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates. Journal of health economics 2010, 29, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skounti, M.; Philalithis, A.; Galanakis, E. Variations in prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder worldwide. European Journal of Pediatrics 2007, 166, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolraich, M.L.; Jr, J.F.H.; Allan, C.; Chan, E.; Davison, D.; Earls, M.; Evans, S.W.; Flinn, S.K.; Froehlich, T.; Frost, J.; Holbrook, J.R.; Lehmann, C.U.; Lessin, H.R.; Okechukwu, K.; Pierce, K.L.; Winner, J.D.; Zurhellen, W. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2019, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wymbs, B.T.; Canu, W.H.; Sacchetti, G.M.; Ranson, L.M. Adult ADHD and romantic relationships: What we know and what we can do to help. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 2021, 47, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldani, S.; Acquaviva, E.; Moscoso, A.; Peyre, H.; Delorme, R.; Bucci, M.P. Reading performance in children with ADHD: An eye-tracking study. Annals of Dyslexia 2022, 72, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.; Braw, Y.; Elbaum, T.; Wagner, M.; Rassovsky, Y. Eye tracking during a continuous performance test: Utility for assessing ADHD patients. Journal of Attention Disorders 2022, 26, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, J.D.; Rizzo, A.; Geng, J.J.; Schweitzer, J.B. Measuring attentional distraction in children with ADHD using virtual reality technology with eye-tracking. Frontiers in virtual reality 2022, 3, 855895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliappan, N.; Dai, N.; Steinberg, E.; He, J.; Rogers, K.; Ramachandran, V.; Xu, P.; Shojaeizadeh, M.; Guo, L.; Kohlhoff, K.; others. Accelerating eye movement research via accurate and affordable smartphone eye tracking. Nature communications 2020, 11, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Líbano, D.; Wainstein, G.; Carrasco, X.; Aboitiz, F.; Crossley, N.; Ossandón, T. A pupil size, eye-tracking and neuropsychological dataset from ADHD children during a cognitive task. Scientific Data 6 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, C.; Morgan, S.B.; Luscomb, R.L. Cognitive functioning of ADHD and non-ADHD boys on the WISC-III and WRAML: An analysis within a memory model. Journal of Attention Disorders 1996, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Farina, M.; Wendt, G.; Esteves, C.; Argimon, I. WISC-III Sensibility in the identification of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Panamerican Journal of Neuropshychology 2012, 6, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Mandelbrot, B.B. The fractal geometry of nature; Vol. 1, WH freeman New York, 1982.

- Einstein, A. others. On the motion of small particles suspended in liquids at rest required by the molecular-kinetic theory of heat. Annalen der physik 1905, 17, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Klafter, J.; Sokolov, I.M. First Steps in Random Walks: From Tools to Applications; Oxford University Press, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Buldyrev, S.; Goldberger, A.; Havlin, S.; Peng, C.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H. Generalized Levy-Walk Model for DNA Nucleotide Sequences. Physical review. E, Statistical physics, plasmas, fluids, and related interdisciplinary topics 1993, 47, 4514–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bé nichou, O.; Loverdo, C.; Moreau, M.; Voituriez, R. Intermittent search strategies. Reviews of Modern Physics 2011, 83, 81–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjao, L.R.; Hassan, G.; Kurths, J.; Witthaut, D. MFDFA: Efficient multifractal detrended fluctuation analysis in python. Computer Physics Communications 2022, 273, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Logistic | SVC | Decision | Random |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | Tree | Forest | ||

| SKF (k = 5) | 0.724 | 0.540 | 0.611 | 0.680 |

| LOOC | 0.724 | 0.540 | 0.596 | 0.724 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).