1. Introduction

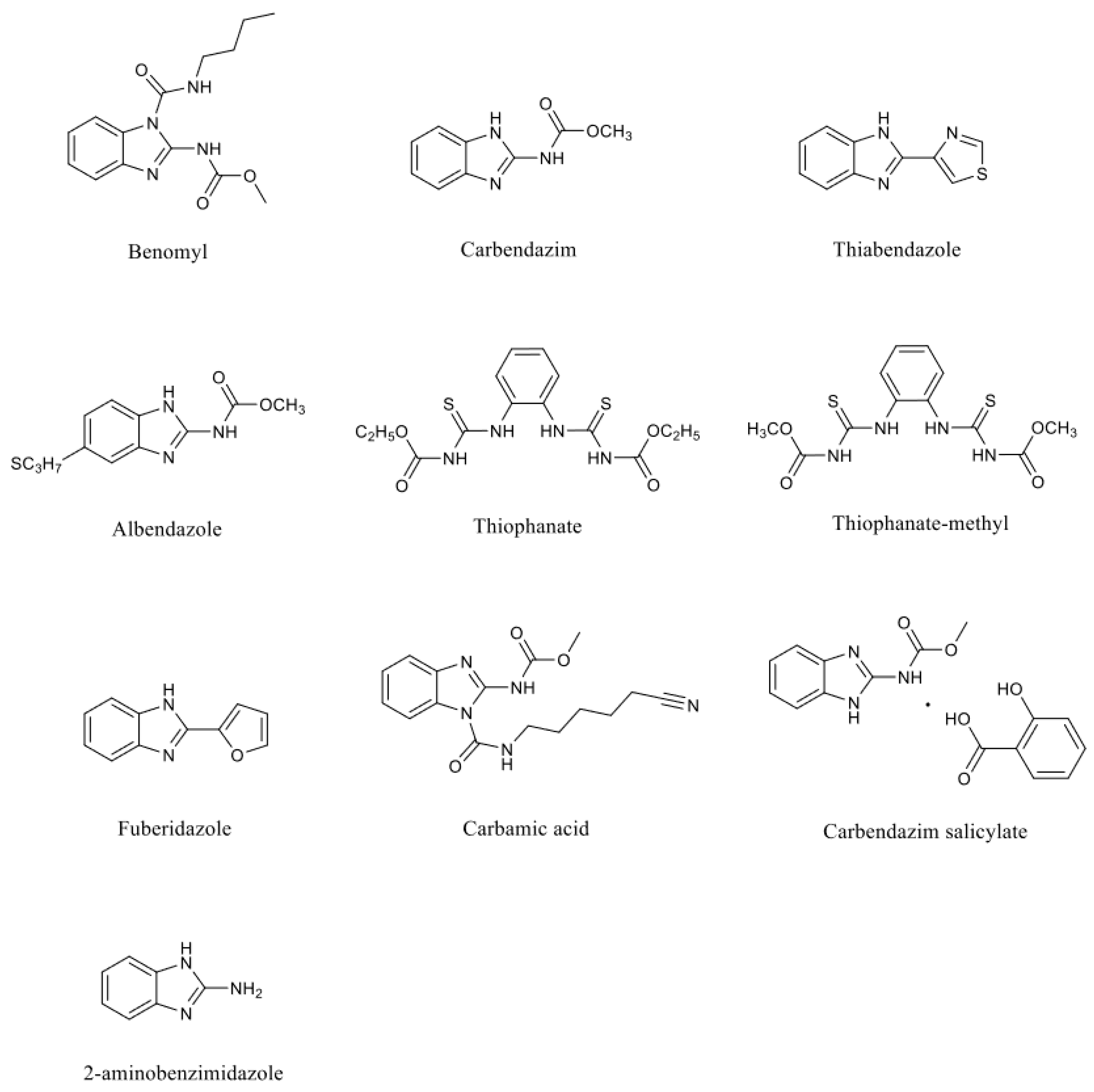

Benzimidazole fungicides are a class of highly effective, low-toxicity, systemic broad-spectrum fungicides based on the benzimidazole ring, which possesses fungicidal activity. The main products include benomyl, carbendazim, thiabendazole, albendazole, thiophanate, thiophanate-methyl, fuberidazole, carbamic acid, and carbendazim salicylate. Although thiophanate-methyl and thiophanate are not based on the benzimidazole ring, they are considered benzimidazole fungicides because they metabolize in plants or on their surfaces into compounds similar to carbendazim or other benzimidazole derivatives, thus exhibiting fungicidal activity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The chemical structures of benzimidazole fungicides (benomyl, carbendazim, thiabendazole, albendazole, thiophanate, thiophanate-methyl, fuberidazole, carbamic acid, carbendazim salicylate) and their main metabolite (2-aminobenzimidazole) are depicted in

Figure 1.

Benzimidazole fungicides are a class of fungicides developed during the 1960s and 1970s [

5]. Benomyl was one of the earlier benzimidazole fungicides, developed by the American company DuPont in 1967. Thiabendazole, originally an intermediate of benomyl, was also developed by DuPont in the same year. Subsequently, the American company Merck successfully developed thiabendazole, which was one of the earliest benzimidazole pesticides to be commercialized and has been in use for several decades [

6]. Thiophanate-methyl was originally developed by the Japanese company Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. Its primary mode of action is to interfere with the formation of fungal hyphae [

7]. In plants, thiophanate-methyl is first converted to carbendazim, which affects the division of fungal cells, causing the germ tubes that sprout from spores to become deformed and thereby killing the fungi [

3,

4,

8,

9]. Thiophanate is quickly converted into ethyl carbendazim when sprayed on plants, which causes abnormal distortion of the germinating bud tube of pathogenic bacteria spores and distortion of the cell wall, affecting the formation of attachment cells. Thiophanate is characterized by high efficiency and low toxicity, long residual period, and also promotes plant growth. Thiophanate is characterized by its high efficiency, low toxicity, long residual effect, and its ability to promote plant growth. Despite being used for several decades, benzimidazole fungicides continue to be widely used today due to their broad-spectrum and highly effective fungicidal activity.

Benzimidazole fungicides possess potent biological activity and are capable of killing a wide range of pathogenic microorganisms. They are used for anticancer, antibacterial, and antiparasitic purposes [

10,

11]. Among their applications, due to their particularly prominent antibacterial activity, they are extensively utilized in the agricultural sectors of grains, fruits, and vegetables to protect crops from pathogenic microorganisms, thereby enhancing crop yield and quality. The mechanism of action of benzimidazole fungicides primarily involves the inhibition of fungal hyphal division and the obstruction of spindle fiber formation during cell mitosis by binding to the microtubule proteins of spindle fibers, effectively suppressing the reproduction and growth of pathogens and achieving antibacterial effects [

12,

13,

14]. These pesticides are convenient to use, exhibit no significant toxicity or side effects on crops, and have a minimal environmental impact, making them favorable agricultural fungicides with promising application prospects. However, benzimidazole fungicides face the issue of strong resistance due to their single target site of action, posing a serious threat to the control of crop diseases in the field, with carbendazim resistance being particularly notable [

15]. To delay or manage pathogen resistance to benzimidazole fungicides, studies suggest mixing or rotating these agents with other fungicides with different mechanisms of action [

16]. Current research on benzimidazole fungicides is primarily focused on carbendazim, thiabendazole, benomyl, and thiophanate-methyl. Research on other benzimidazole fungicides is relatively scarce and not sufficiently in-depth, indicating that these fungicides warrant further development and use. This article primarily provides a comprehensive review of the physicochemical properties, disease control efficacy, toxicological characteristics, and pesticide residue and detection techniques for benzimidazole fungicides (such as benomyl, carbendazim, thiabendazole, albendazole, thiophanate, thiophanate-methyl, fuberidazole, carbamic acid, carbendazim salicylate) and their main metabolite (2-aminobenzimidazole). Based on this information, the paper offers a prospective outlook on the future research directions for benzimidazole fungicides, which may facilitate further development and rational utilization of these compounds.

2. Physical and chemical properties

Benzimidazole is an organic compound with the chemical formula C

7H

6N

2. It forms flaky crystals that are slightly soluble in cold water and ether, more soluble in hot water, and readily soluble in ethanol, acidic solutions, and strong alkaline solutions. The melting point is 171°C, and the boiling point is 360°C, with a CAS number of 51-17-2. Benzimidazole fungicides are a class of fungicides based on the benzimidazole structure, typically appearing as white or yellow crystalline powders with melting points ranging from 200 to 300°C. They are prone to hydrolysis during dissolution. Benzimidazole fungicides are usually basic or neutral, insoluble in most organic solvents and pure water substances, but most can dissolve in strong polar solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide and N,N-dimethylformamide, and in strong acids. The imidazole ring often found in the molecules of benzimidazole fungicides is a highly active structure. Various fungicides with different effects and properties can be synthesized by substituting at different positions on the imidazole ring. Benzimidazole fungicides (such as benomyl, carbendazim, thiabendazole, albendazole, thiophanate, thiophanate-methyl, fuberidazole, carbamic acid, and carbendazim salicylate) and their main metabolite (2-aminobenzimidazole) have physicochemical properties as shown in

Table 1.

Carbendazim has stable chemical properties, and the technical material can be stored for 2 to 3 years in a cool and dry place. The pure product is a light gray or beige powder with a melting point of 302-307℃. At 24℃, its solubility in water is 0.008 g/L, in dimethylformamide is 5 g/L, in acetone is 0.3 g/L, in ethanol is 0.3 g/L, in chloroform is 0.1 g/L, and in ethyl acetate is 0.135 g/L. It hydrolyzes slowly in an alkaline medium and is stable in an acidic medium, capable of forming salts. Thiabendazole pure product is a white crystalline powder, odorless and tasteless, stable in water, acid, and alkaline solutions. The melting point is 298-301°C. At 20°C, its solubility in water is 0.03 g/L, in acetone is 2.43 g/L, in methanol is 8.28 g/L, in xylene is 0.13 g/L, in ethyl acetate is 1.49 g/L, and in octanol is 3.91 g/L. The pure product of benomyl is a white crystalline powder with a melting point of 140°C (decomposition). It is insoluble in water and oil, but soluble in chloroform, acetone, and dimethylformamide. The pure product of albendazole is a white powder with a melting point of 206-212°C. It is odorless and tasteless, insoluble in water, slightly soluble in ethanol, chloroform, hot dilute hydrochloric acid, and dilute sulfuric acid, and soluble in glacial acetic acid. Thiophanate is a colorless flaky crystal with a melting point of 195°C (decomposition). It is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents such as dimethylformamide, acetonitrile, and cyclohexane. It can recrystallize in solvents like ethanol and acetone, and it has stable chemical properties. The pure product of thiophanate-methyl is a colorless crystalline solid, while the technical powder (93%) appears as yellow crystals. It has a melting point of 172°C (decomposition). Its solubility in water and other solvents is very low, but it dissolves easily in dimethylformamide, dioxane, chloroform and is also soluble in solvents such as acetone, methanol, ethanol, and ethyl acetate. It is stable in the presence of acids and bases. The pure form of fuberidazole is a colorless crystalline solid with a melting point of 286°C. At room temperature, it is insoluble in water, but readily soluble in organic solvents such as methanol, ethanol, and acetone. Its solubility in water is 0.0078 g/L, in dichloromethane it is 1 g/L, and in isopropanol, it is 5 g/L. Additionally, it is also soluble in methanol, ethanol, and acetone. It is unstable when exposed to light. The pure form of carbamic acid is a colorless crystal that is insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents such as toluene, dichloromethane, dimethylformamide, and cyclohexane. The wettable powder for carbendazim salicylate is a grayish-white powder, and the soluble agent is a dark brown liquid, both of which are soluble in water. The main metabolite of benzimidazole fungicides, 2-aminobenzimidazole, is a pure substance that appears as white or light yellow crystalline solid. It has a melting point of 226-230°C and a boiling point of 235.67°C. It is soluble in water, ethanol, and acetone, but insoluble in diethyl ether and benzene.

3. Disease prevention and control

In contemporary agricultural production, effective prevention and control of crop diseases is a key factor in ensuring food security and increasing yield. As a broad-spectrum and highly efficient fungicide, benzimidazole fungicides have significant effects in controlling a variety of crop diseases. For example, benomyl has a good inhibitory effect on diseases caused by fungi from the subphyla Ascomycotina, Deuteromycotina, and certain Basidiomycotina[

17], but it is ineffective against rusts, flagella, and zygomycetes. Benomyl is widely used in agriculture to control a variety of crop diseases, including powdery mildew and scab in apples and pears, wheat scab, rice blast, cucurbit scab and anthracnose, eggplant gray mold, tomato leaf mould, scab of cucurbits, allium gray mold rot, celery gray spot disease, asparagus stem blight, citrus scab and gray mold, soybean sclerotinia, peanut brown spot disease, as well as sweet potato black spot disease and dry rot, etc. Carbendazim is effective against diseases caused by fungi such as Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium spp., Alternaria spp., Penicillium spp., Cladosporium spp., Sclerotinia spp., Venturia spp., Plasmopara spp., Rhizoctonia spp., and others. These include wheat diseases such as wheat head blight, loose smut, and glume blotch; oat loose smut; cereal stem rot; powdery mildew in wheat, apples, pears, grapes, and peaches; apple scab; pear black spot; pear ring rot; grape gray mold and white rot; cotton seedling blight and boll rot; peanut leaf spot and root rot; tobacco anthracnose; tomato early blight and gray mold; pineapple disease in sugarcane; beet leaf spot; rice blast, sheath blight, and sesame leaf spot, among others. However, despite its effectiveness against certain pathogens of the Ascomycota subphylum and most pathogens of the Deuteromycota subphylum, it is ineffective against oomycetes and bacteria. Thiabendazole exhibits good antimicrobial effects against the main pathogens in ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, and deuteromycetes. However, it is ineffective against pathogens belonging to genera such as Mucor, Peronospora, Phytophthora, Rhizopus, and Pythium, and it does not show activity against oomycetes and zygomycetes causing smut diseases. Thiabendazole is primarily used for the prevention and treatment of various plant diseases, including citrus green mold, blue mold, and stem-end rot, and is also suitable for post-harvest preservation. Albendazole is effective against diseases caused by various basidiomycetes and ascomycetes, such as rice blast and tobacco anthracnose. Thiophanate can effectively prevent and treat a variety of plant diseases, including Fusarium head blight (scab), powdery mildew, and smut in cereal crops; rice blast, sheath blight, and kernel smut in rice; as well as various fungal diseases in vegetables, fruits, and other crops [

18]. Thiophanate-methyl can control and prevent diseases such as rice blast and sheath blight in rice, rust and powdery mildew in wheat, Fusarium head blight (scab) and smut in cereal crops, sclerotinia in rapeseed, downy mildew in tomatoes, anthracnose and leaf spot in various vegetables, scab in peanuts, as well as powdery mildew and anthracnose in fruit trees [

19]. Fuberidazole exhibits effective antimicrobial properties against major pathogens of Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, and Deuteromycetes, and is suitable for the prevention and control of wheat diseases such as black head mold and snow mold [

20,

21]. Carbamic acid can prevent and treat diseases such as rice bakanae disease, and powdery mildew in apples and pears. Whereas carbendazim salicylate can effectively control a variety of fungal diseases such as wheat scab and cotton wilt. These agents provide a diversified selection to meet the disease management needs of different crops.

4. Toxicological Properties

According to the Chinese pesticide toxicity classification standards (

Table 2) [

22,

23,

24,

25], benzimidazole fungicides such as benomyl, carbendazim, thiabendazole, and carbendazim salicylate are considered low toxicity or slightly toxic pesticides. Pesticides like thiophanate-methyl, thiophanate, fuberidazole, and carbamic acid are classified as moderately low toxicity or low toxicity pesticides. The main metabolite of benzimidazole fungicides, 2-aminobenzimidazole, is of low toxicity. Benzimidazole fungicides possess systemic properties, allowing them to be absorbed into the flesh of agricultural products while killing harmful organisms. The potential dosage present in the produce can cause chronic or acute toxicity to humans, posing a risk to human health. Benzimidazole fungicides have teratogenic and embryotoxic effects on a variety of animals [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The toxicity of benzimidazole fungicides is shown in

Table 3. Studies have shown that carbendazim has certain toxicity to humans and animals, and can cause symptoms of poisoning such as excitement, convulsions, mental confusion, nausea and vomiting, dizziness and headache, chest tightness, and upper abdominal tenderness [

30,

31]. It can also cause liver diseases, as well as chromosomal abnormalities, endocrine system disorders, and teratogenic effects [

32,

33]. Thiabendazole has a certain level of toxicity to humans, primarily affecting the liver, nervous system, and bone marrow [

34,

35]. The main metabolite of benzimidazole fungicides, 2-aminobenzimidazole, is toxic to human skin and eyes [

36]. Based on these findings, countries around the world have imposed strict controls on the use of benzimidazole fungicides, and there are stringent requirements for their residue levels. The standards for pesticide residue limits in China [

37], South Korea [

38], and the European Union [

39], as well as the Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) standards in China and South Korea, are shown in

Table 4.

5. Pesticide Residue and Detection Technology

Benzimidazole fungicides are extensively employed during the growth and storage phases of a variety of crops, including vegetables and fruits, for the control and prevention of fungal diseases. Improper use can result in residues remaining in fruits and vegetables. With the continuous advancement of science and technology, methods for detecting pesticide residues have also been evolving. Detection techniques have progressed from the earliest paper chromatography, thin-layer chromatography, and gel permeation chromatography to current methods such as spectroscopic analysis [

41], immunoassay, gas chromatography (GC) [

42], gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [

43], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [

44], and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [

45]. Currently, in the residual analysis of benzimidazole fungicides reported both domestically and internationally, the focus is primarily on the study of carbendazim and thiabendazole. The detection methods commonly employed are HPLC and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [

46,

47,

48]. Sample pretreatment techniques include liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), solid-phase extraction (SPE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE). With the widespread adoption of the QuEChERS method, which is rapid, simple, inexpensive, effective, reliable, and safe, it is now commonly used for the high-efficiency and rapid pretreatment of samples [

49,

50,

51].

5.1. Spectroscopic Analysis Method

Spectroscopic analysis encompasses methods such as ultraviolet spectrophotometry, fluorescence analysis, phosphorescence, cryoluminescence, and other luminescence analytical techniques. Among these, fluorescence analysis is the most commonly employed, including both fluorescence excitation and emission spectroscopy. Compared to ultraviolet absorption spectrophotometry, fluorescence analytical techniques are extensively applied in the residual analysis of benzimidazole fungicides in environmental and food samples due to their higher sensitivity and the advantage of being rapid and straightforward. Zhong et al. [

36] employed three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy in conjunction with chemometric second-order calibration for the quantitative analysis of thiram and carbendazim in red wine. By utilizing direct quantitative analysis, the method is characterized by short analysis time and high efficiency in extraction and separation. Qamar et al. [

52] employed an ion chromatography system coupled with a post-column photochemical derivatization fluorescence detector for the detection of carbendazim. Under optimized conditions, the method exhibited a strong linear response with correlation coefficients greater than or equal to 0.9966, demonstrated good reproducibility, and achieved high recovery rates.

5.2. Gas Chromatography

In the 1970s, gas chromatography made significant contributions to the enhancement of pesticide residue detection techniques due to its high separation efficiency and sensitivity. Gas chromatography employs an inert gas as the mobile phase to separate and identify substances, and is suitable for the analysis of volatile and chemically stable compounds. However, it is not appropriate for pesticides with high boiling points and thermal instability. For example, carbendazim, a benzimidazole fungicide, is a thermally unstable compound and is not suitable for direct analysis by gas chromatography. However, Xu et al. [

42] established a derivatization gas chromatography-nitrogen-phosphorus detection method for the determination of carbendazim residues in environmental water samples, which has the characteristics of high accuracy, good reproducibility and low detection limit.

5.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) combines the high-efficiency separation capability of chromatography with the accurate identification ability of mass spectrometry. This not only enhances the separation efficiency but also improves the accuracy of identification, achieving the goals of both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Zhang et al. [

53] detected the residue of tthiabendazole in longan samples by gas chromatography, which is a simple, sensitive and accurate method, and it is a more ideal method for the detection of thiamethoxam residue in longan.

5.4. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is an analytical detection technique that developed in the 1970s and is one of the most commonly used analytical methods. Currently, 80% of compounds require separation and detection by high-performance liquid chromatography. In national standards, the detection and analysis of carbendazim, thiabendazole, thiram, and benomyl are carried out using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. For example, studies have reported the detection of carbendazim residues in edible mushrooms, soybeans, wine, rapeseed, asparagus, American ginseng herbs, dendrobium, longan, and fruit juices by HPLC [

54,

55,

56]. Giowanni et al. [

58] employed HPLC with a diode-array detector (DAD) to detect the residues of thiabendazole and propiconazole in bovine liver. Al-Ebaisat [

58] utilized a combination of high-performance liquid chromatography and solid-phase extraction to measure the levels of carbendazim and benomyl in tomato paste. The recovery rate was 90.0-95.5%, with a detection limit of 5 μg/kg. Liang et al. [

59] utilized matrix solid-phase dispersion (MSPD) combined with dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (DLLME), which was optimized by chemometric methods. They applied this optimized method (MSPD-DLLME-HPLC-UV) for the detection of carbendazim, thiabendazole and thiophanate in vegetable samples, and achieved effective extraction, purification and quantification of these substances. The method showed good linearity in the concentration range of 0.25-5 μg/g and the recoveries were in the range of 65.4-124.0%.

5.5. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

The principle of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) involves initially ionizing the sample to be analyzed, then separating it according to the mass-to-charge ratio to obtain a mass spectrum. By using the mass spectral information of the sample and its fragments, qualitative and quantitative analysis of the test sample can be conducted. It is an important method for determining organic compounds. Wu et al. [

60] used LC-MS to detect the residues of procymidone in watermelon, achieving an average recovery rate of 82.3%-93.6%. Similarly, employing LC-MS technology, Kim et al. [

61] detected residues of procymidone and thiabendazole in bean sprouts, with recovery rates ranging from 89.5% to 103.2% when the added concentration was 20-40 mg/kg. Blasco et al. [

62] applied LC-MS techniques to determine the content of procymidone in peaches and nectarines. Bean et al. [

63] used G-protein immunoadsorbent column coupled with reverse-phase liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to detect procymidone in lake water and soil samples. The advantage of this method is that it utilizes immunoadsorbent extraction technology, which can reduce matrix interference and increase the accuracy of sample detection. Wang [

64] determination of carbendazim in orange juice using QuEChERS and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Since benomyl is very unstable and easily decomposes into carbendazim when exposed to organic solvents or water. Dong et al. [

65] employed the QuEChERS method for extraction and HPLC-MS/MS for the determination of thiabendazole and carbendazim in watercress, with an average recovery rate of 96.2%-102.9%. The limit of quantification was 0.01 mg/kg.

5.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a technique where an antigen or antibody is linked to an enzyme to form an enzyme-labeled antigen or antibody complex. Upon the addition of a substrate, the enzyme catalyzes a reaction that produces a colored substance. The intensity of the color is directly proportional to the amount of the product, allowing for qualitative and quantitative analysis based on the shade of the color. This technique offers advantages such as speed, sensitivity, and ease of standardization. For example, the researchers designed and synthesized the hapten of carbendazim based on its molecular structure and specific functional groups, prepared artificial antigens and antibodies, and established and optimized a method for the indirect competitive ELISA for the quantitative detection of carbendazim. This provides a foundation for the development of test kits suitable for the rapid, on-site detection of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. Šmídová et al. [

66] proposed an immunoassay for the detection of thiabendazole residues in food, with a detection limit of 0.005 mg/kg in apple juice, and a detection limit of 0.05 mg/kg in pears and oranges. Blažková et al. [

67] established a rapid detection method for thiabendazole residues in fruit juices based on a strip-based immunoassay. Using carbon nanoparticles as markers, the non-direct competitive immunoassay for thiabendazole can be completed in 10 minutes under optimal conditions. The method is precise, stable, and specific, with a detection limit of 0.25 ppb and a recovery rate of 89.9 to 123.6%. Estevez et al. developed a sensitive and specific competitive immunoassay method based on Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for the detection of thiabendazole in oranges. They used an indirect assay format by immobilizing the thiabendazole-protein conjugate on a gold film surface. The analyte from the oranges was extracted with methanol, achieving satisfactory recovery rates. The sensitivity and reliability tests on orange samples confirmed the effectiveness and dependability of the SPR sensor, making it suitable for determining thiabendazole in food products.

6. Conclusions

Benzimidazole fungicides occupy an important position in the field of agricultural disease prevention and control due to their broad-spectrum antifungal activity. Current research on benzimidazole fungicides is mainly focused on carbendazim, thiabendazole, benomyl, and thiophanate-methyl, and their antifungal spectrum is broader and more effective. Pesticide residue detection often uses liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. With the changes in crop diseases and considerations for environmental safety and food safety, the development of benzimidazole fungicides is showing new trends. Future research will focus more on the development of high-efficiency, low-toxicity, low-residue environmentally friendly green pesticides. At the same time, due to the serious resistance issues of benzimidazole fungicides, subsequent research will further address the resistance problems of these fungicides. Finally, benzimidazole fungicides can be used in combination with intelligent pesticide application technologies, which will make the use of benzimidazole fungicides more precise, thereby enhancing their application value and environmental safety in agricultural production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., M.Z. and S.T.; resources, S.B.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, R.W.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, S.B. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guizhou Province (Grant No. Qian Ke He Ji Chu ZK [2022]Zhong Dian 025); the High School Science and Technology Talent Support Project of Guizhou Province, China (Grant No. Qian Jiao He KY Zi [2021]037); the Opening Foundation of the Key Laboratory of Green Pesticide and Agricultural Bioengineering, the Ministry of Education, Guizhou University (Grant No. Qian Jiao Ji [2022]433); the Guizhou Industry Polytechnic College Faculty-level Research Project (Grant No. 2023ZK10); the Guizhou Industry Polytechnic College Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (Grant No. 2023CXTD03); the Guizhou Industry Polytechnic College Faculty-level Research Project (Grant No. 2023ZK11); the High-Level Talent Initial Funding of Guizhou Industry Polytechnic College (Grant No. 2023-RC-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sun, X.; Liu, C.J.; Yang, B.B.; Geng, R.H.; Wang, D.L. Residue analysis and risk assessment of dietary intake of thiophanate-methyl and its metabolite in Hemerocallis citrina Baroni. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2022, 13.

- Xiao, L.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.T.; Liu, Z.Q.; Liu, C.L.; Liu, Y.P.; Li, X.G. Residues and dissipation of thiophanate-methyl and its metabolites carbendazim in citrus. Agrochemicals 2018, 57, 276-278.

- Ahmed, M.U.; Hasan, Q.; Hossain, M.M.; Saito, M.; Tamiya, E. Meat species identification based on the loop mediated isothermal amplification and electrochemical DNA sensor. Food Control 2010, 21, 599-605. [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, F.; Yu, C.; Pan, C. Spinach or amaranth may represent highest residue of thiophanate-methyl with open field application on six leaf vegetables. B. Environ. Contam. Tox. 2013, 90, 477-481. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, H.Q.; Wang, Y.L. Progress in the synthesis and application of benzimidazoles and their derivatives. Chinese J. Org. Chem. 2008, 28, 210.

- Danaher, M.; De Ruyck, H.; Crooks, S.R.; Dowling, G.; O'Keeffe, M. Review of methodology for the determination of benzimidazole residues in biological matrices. J. Chromatogr. B 2007, 845, 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Li, F. J.; Komura, R.; Nakashima, C.; Shimizu, M.; Kageyama, K.; Suga, H. Molecular diagnosis of thiophanate-methyl-resistant strains of Fusarium fujikuroi in Japan. Plant Dis. 2002, 106, 634-640. [CrossRef]

- Prousalis, K.P.; Polygenis, D.A.; Syrokou, A.; Lamari, F.N.; Tsegenidis, T. Determination of carbendazim, thiabendazole and o-phenylphenol residues in lemons by HPLC following sample clean-up by ion-pairing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 379, 458-463. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, G.; Lan, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Determination, dissipation dynamics, terminal residues and dietary risk assessment of thiophanate-methyl and its metabolite carbendazim in cowpeas collected from different locations in China under field conditions. J. Sci. Food Agr. 2021, 101, 5498-5507.

- Zhang, Y.X. Determination of benzimidazoles residues in beef by HPLC. Livestock and pouliry industry, 2006, 6-7.

- Zhang, S.X.; Li, J.S.; Qian, C.F. Matrix solid-phase dispersion-high performance liquid chromatographic multi-residue analysis of benzimidazoles in bovine muscle tissue. Chin. J. Vet. Sci. 2000, 20, 569-571.

- Chen, Y. Study on analysis method of benzimidazole fungicide residues and residue status in fruits. CAAS Dissertation 2008.

- Fujimura, M.; Oeda, K.; Inoue, H.; Kato, T. A single amino-acid substitution in the beta-tubulin gene of Neurospora confers both carbendazim resistance and diethofencarb sensitivity. Curr. Genet. 1992, 21, 399-404. [CrossRef]

- Albertini, C.; Gredt, M.; Leroux, P. Mutations of the β-tubulin gene associated with different phenotypes of benzimidazole resistance in the cereal eyespot fungi Tapesia yallundae and Tapesia acuformis. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 1999, 64, 17-31. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Lu, Y.J.; Zhou, M.G. Research progress on benzimidazole fungicides, the third academic seminar on chemical control of plant diseases. Phytopathology Society, Zhangjiajie 2002.

- Mao,Y.S.; Duan, Y.B.; Zhou, M.G. Research progress of the resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2022, 24, 937-948. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.W. Study on the LC-MS/MS methods for detecting benzimidazole fungicides and metabolites in concentrated fruit juice. Guangxi Univ. 2013.

- Xiong, J.F.; Li, J.X.; Mo, G.Z.; Huo, J.P.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, Z.Y. Benzimidazole derivatives: selective fluorescent chemosensors for the picogram detection of picric acid. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11619-11630. [CrossRef]

- Fussell, R.J.; Hetmanski, M.T.; Macarthur, R.; Findlay, D.; Smith, F.; Ambrus, Á.; Brodesser, P.J. Measurement uncertainty associated with sample processing of oranges and tomatoes for pesticide residue analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1062-1070. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xuan, L.N.; Zhao, H.C.; Cheng, J.; Fu, X.Y.; Li, S.; Jing, F.; Liu, Y.M.; Chen, B.Q. Synthesis and antitumor activities of 1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives possessing benzisoselenazolone scaffold. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2014, 30, 764-769.

- Xue,W.; Gong, H.Y.; Chou, Q.J.; Zhao, H.J.; Li, H.C.; Han, F.F.; Xia, L.J. Synthesis of oxime ester derivatives of curcumin and their antibacterial activity study. Chemical Reagents 2013, 35, 201-205.

- Duan, L.F. FAO standards for the identification of highly hazardous pesticides. Pesticide Science and Administration, 2019, 40, 8-8.

- Xu, D.G.; Feng, C.G. Pesticide toxicity classification and recommendations. Plant Doctor 2015, 28, 35-37.

- Liu, W.P.; Zhang, Y. Progress in potential toxicity of chiral pesticides. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric. Life Sci. ) 2012, 38, 63-70.

- Xu, P.Y.; Wu, D.S. New progress in the study of organophosphorus pesticide toxicity. J. Prev. Med. Health Inf. 2004, 20, 389-392.

- Yoon, C.S.; Jin, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Yeo, C.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Hwang, Y.G.; Hong, S.J.; Cheong, S.W. Toxic effects of carbendazim and n-butyl isocyanate,metabolites of the fungicide benomyl,on early development in the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. Environ. Toxicol. 2008, 23, 131-144.

- Wei, Z.H.; Xu, J.; Guo, M.X.; Shi, A.M.; Sun, J.Z. Research progress on domestic carbendazim. J. Anhui Agri. Sci. 2015, 43, 125 -127+141.

- Roepcke, C.B.; Muench, S.B.; Schulze, H.; Bachmann, T.; Schmid, R.D.; Hauer, B. Analysis of phosphorothionate pesticides using a chloroperoxidase pretreatment and acetylcholinesterase biosensor detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8748-8756. [CrossRef]

- Knäbel, A.; Meyer, K.; Rapp, J.; Schulz, R. Fungicide field concentrations exceed focus surface water predictions: urgent need of model improvement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 455-463. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.C.; Wang, X.F. Research progress of toxicology of carbendazim. Occup and Health 2008, 24, 1834-1835.

- Song, Y.C.; Yu, C.G.; Wang, X.F. Research progress on reproductive toxicity of carbendazim. Chin. Occup Med. 2010, 37, 505-507.

- Song, Y.C. Study on the mechanism of the carbendazim-induced reproductive toxicity in male rats. University of Jinan 2011.

- Sun, Y,X. Pesticide residue and hazard analysis in vegetables. Mod. Agric. 2020, 9, 64-66.

- Gao, Z.X.; Wu, Y.H.; Zheng, H.F.; Ao, K.H.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Q.H.; Huang, C. Residue analysis of triabendazole in peruvian ground cherry by RP-HPLC-PDA. Food Sci. 2012, 10, 204-207.

- Ekman, E.; Faniband, M.H.; Littorin, M.; Maxe, M.; Jönsson, B.A.; Lindh, C.H. Determination of 5-hydroxythiabendazole in human urine as a biomarker of exposure to thiabendazole using LC/MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 973, 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.D. Fluorescence approaches for rapid determination of benzimidazole fungicides in food. Xiamen Univ. 2014.

- GB 2763-2021 National Food Safety Standard - Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticides in Food.

- Ministry of Food anddrug Safety of the South Korea. Pesticide MRLs in Food. http://www.mfds.go.kr/index.do#info.

- European Commission (EU). European Commission. EU-Pesticides database. https://ec. europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/mrls/? event=search.pr.

- Sun, J.L.; Qi, J.S. Modern pesticide application technology series: fungicides volume. 2014.

- Del Pozo, M.; Hernández, L.; Quintana, C. A selective spectrofluorimetric method for carbendazim determination in oranges involving inclusion-complex formation with cucurbit [7] uril. Talanta 2010, 81, 1542-1546. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Zou, Q.L.; Zhong, G.J.; Yang, Y.S. Determination of carbendazim in water samples by derivative gas chromatography method. Environ. Monit. Chin. 2012, 28, 41-43.

- Trenholm, R.A.; Vanderford, B.J.; Holady, J.C.; Rexing, D.J.; Snyder, S.A. Broad range analysis of endocrine disruptors and pharmaceuticals using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Chemosphere, 2006, 65, 1990-1998. [CrossRef]

- Zamora, O.; Paniagua, E.E.; Cacho, C.; Vera-Avila, L.E.; Perez-Conde, C. Determination of benzimidazole fungicides in water samples by on-line MISPE–HPLC. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 393, 1745-1753. [CrossRef]

- Mezcua, M.; Agüera, A.; Lliberia, J.L., Cortés, M.A.; Bagó, B.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Application of ultra performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry to the analysis of priority pesticides in groundwater. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1109, 222-227. [CrossRef]

- Soler, C.; Mañes, J.; Picó, Y. Comparison of liquid chromatography using triple quadrupole and quadrupole ion trap mass analyzers to determine pesticide residues in oranges. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1067, 115-125. [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y.; la Farré, M.; Soler, C.; Barceló, D. Identification of unknown pesticides in fruits using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry: Imazalil as a case study of quantification. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1176, 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.L.; Liu, X.G.; Xu, J.; Dong, F.S.; Liang, X.Y.; Li, M.M.; Duan, L.F.; Zheng, Y.Q. Simultaneous determination of spirotetramat and its four metabolites in fruits and vegetables using a modified quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe method and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1299, 71-77. [CrossRef]

- Schenck, F.J.; Hobbs, J.E. Evaluation of the quick,easy,cheap,effective,rugged,and safe (QuEChERS) approach to pesticide residue analysis. B. Environ. Contam. Tox. 2004, 73, 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Lehotay, S.J.; Son, K.A.; Kwon, H.; Koesukwiwat, U.; Fu, W.; Mastovska, K.; Hoh, E.; Leepipatpiboon, N. Comparison of QuEChERS sample preparation methods for the analysis of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 2548-2560. [CrossRef]

- Wilkowska, A.; Biziuk, M. Determination of pesticide residues in food matrices using the QuEChERS methodology. Food chem. 2011, 125, 803-812. [CrossRef]

- Subhani, Q.; Huang, Z.P.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Zhu, Y. Simultaneous determination of imidacloprid and carbendazim in water samples by ion chromatography with fluorescence detector and post-column photochemical reactor. Talanta 2013, 116, 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.H.; Wu, N.C.; Yin, G.H.; Wu, X.F. Determination of thiabendazole, paclobutrazol and hexaconazole pesticide residues in longan using GC-MS/MS. Agrochemicals 2014, 53, 423-425.

- Gao, R.; Zhao, R.Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.H.; Xiao, H. Determination of carbendazim residues in rapeseed by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Nanjing Med. Univ.: Nat. Sci. Ed. 2004, 24, 425-426.

- Liu. C.L.; Liu, F.M.; Li, L.; Lan, R.H.; Jiang, S.R. The determination of carbendazim and imidacloprid residues in asparagus by high performance liquid chromatography. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2004, 6, 93-96.

- Peng, F.; Tian,J.G.; Jin, H.Y.; Du, Q.P. Determ ination of residual carbendazim in chinese traditional medicine of ginseng by HPLC. Chinese Pharm. J. 2007, 42, 475-477.

- Caprioli, G.; Cristalli, G.; Galarini, R.; Giacobbe, D.; Ricciutelli, M.; Vittori, S.; Zou, Y.T.; Sagratini, G. Comparison of two different isolation methods of benzimidazoles and their metabolites in the bovine liver by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography–diode array detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 1779-1785. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ebaisat, H. Determination of some benzimidazole fungicides in tomato puree by high performance liquid chromatography with SampliQ polymer SCX solid phase extraction. Arab. J. Chem. 2011, 4, 115-117. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Zhao, Y.X.; Li, P.; Yu, Q.L. Matrix solid-phase dispersion based on cucurbit[7]uril-assisted dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography for the determination of benzimidazole fungicides from vegetables. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1658, 462592. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hu, J. Residue analysis of albendazole in watermelon and soil by solid phase extraction and HPLC. Anal. Lett. 2014, 47, 356-366. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.G.; Park, D.W.; Kang, G.R.; Kim, T.S.; Yang, Y.; Moon, S. J.; Choi, E.A.; Ha, D.R.; Kim, E.S.; Cho, B.S. Simultaneous determination of plant growth regulator and pesticides in bean sprouts by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Food chem. 2016, 208, 239-244. [CrossRef]

- Blasco, C.; Fernández, M.; Picó, Y.; Font, G.; Mañes, J. Simultaneous determination of imidacloprid, carbendazim, methiocarb and hexythiazox in peaches and nectarines by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta, 2002, 461, 109-116.

- Bean, K. A.; Henion, J. D. Determination of carbendazim in soil and lake water by immunoaffinity extraction and coupled-column liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1997, 791, 119-126. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Determination of carbendazim in orange juice using QuEChERS and LC/MS/MS. Lc Gc Europe 2012, 11-11.

- Dong, B.; Hu, J. Residue dissipation and dietary intake risk assessment of thiophanate-methyl and its metabolite carbendazim in watercress under Chinese field conditions. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 561-574. [CrossRef]

- Šmídová, Z.; Blažková, M.; Fukal, L.; Rauch, P. Pesticides in food–immunochromatographic detection of thiabendazole and methiocarb. Czech J. Food Sci. 2009, 27, S414-S416. [CrossRef]

- Blažková, M.; Rauch, P.; Fukal, L. Strip-based immunoassay for rapid detection of thiabendazole. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 2122-2128. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).