1. Introduction

There has been a growing interest in synthesizing fibers based on natural polymers. The advantages of natural polymers include biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and non-toxicity [

1]. Although most natural polymers are of limited use due to the challenges of fiber production [

2], it has been possible to prepare fibers from collagen, gelatin, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid [

3,

4]. Gelatin is a biopolymer obtained by partial hydrolysis of collagen, the most abundant structural protein in animal connective tissues such as skin, tendons, cartilage, and bones. The traditional sources of collagen are bovine or porcine tissues, but the use of other lesser-known raw materials, such as poultry or fish, is on the rise. In particular, the consumption of chicken meat is increasing every year, but so is the number of by-products, such as offal, paws, or bones, which have no further use as secondary raw materials. They are most often incinerated or added to compound feed [

5]. Before the gelatin extraction step, collagen tissues are usually treated in an acidic or alkaline way, which, using more aggressive chemicals, is not environmentally friendly but also not friendly to the source material. As an alternative method, a suitable proteolytic enzyme is being offered [

6].

Polymer fibers are produced in several different ways. The most well-known is electrospinning, drawing from a solution, meltblown, and centrifugal spinning [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Electrospinning is a process that produces fibers with diameters between tens of nanometers and units of micrometers; typically, fiber diameters are in the hundreds of nanometers. With this technology, we can obtain fibers from polymer solutions and melt them from the free surface (needleless electrospinning) or a needle (needle electrospinning). The electrospinning device consists of two oppositely charged electrodes, one in contact with a liquid (polymer solution) or melt. A so-called Taylor cone or multiple cones are formed when a critical electrical voltage is reached. The critical value of the electrical voltage is the value above which the spinning process occurs. Parameters such as the shape and arrangement of the electrodes and spinning collector determine the final form of the fibers. Furthermore, the properties of the spinning solution, such as its viscosity, surface tension, electrical conductivity, are essential. Environmental conditions, such as temperature and humidity, also affect the fibers' form [

7].

The principle of drawing is the production of fibers from a polymer solution or melt using a micropipette with a diameter of a few micrometers. The micropipette moves at different speeds depending on the polymer or polymer solution. The resulting fiber is deposited on the mat's surface, where it comes into contact with the micropipette. The method is demanding in terms of the properties of the polymer solution or melt, which are required to have good viscoelasticity and cohesion yet have minimal requirements for equipment [

8]. Meltblown is a technology in which fibers are formed by hot air flowing around spinning nozzles at high speed. First, the polymer is melted using a melt extruder. The melt then passes through a dosing gear pump into a spinning system, from where it is pulled off by a stream of hot air and formed into a filament. Meltblown is typical for its extensive range of possible fiber diameters. However, owing to the need to heat a large amount of air, it is also energy-consuming [

9].

Centrifugal spinning is beginning to be included among spinning methods. The technology primarily uses centrifugal forces. With centrifugal spinning, fibers are prepared from both polymer solution and melt. In many cases, it can be more cost-effective than the current technologies. This is in terms of energy (no need to heat the air) and material consumption (solvent savings). In addition, no electrical conductivity is required from the polymer liquids. However, there are also many disadvantages, such as the relatively large diameter of the resulting fibers [

10].

To improve the mechanical and physical properties of gelatin it is possible to induce crosslinking, which consists of the formation of covalent bonds between gelatin molecules. This can be achieved in three ways - chemically, physically, and enzymatically [

11]. Chemically crosslinked gels are obtained by radical polymerization of monomers with low molecular weight crosslinking agents. Water-soluble polymers containing a hydroxyl group can be crosslinked with glutaraldehyde. This crosslinking occurs only at low pH and high temperature. Glutaraldehyde is also used as a crosslinking agent with polymers containing an amino group under milder conditions than polymers with an -OH group. Glutaraldehyde is a toxic compound exhibiting cell growth inhibition. Therefore, other alternatives are being developed for industrial crosslinking applications, and glutaraldehyde is gradually phased out. The EU legislation allows an acceptable maximum limit of 2 mg of glutaraldehyde per kilogram of product [

12]. The US legislation allows the use of glutaraldehyde as a cross-linker for food purposes but does not specify the amount [

13].

Physical crosslinking occurs via hydrogen or ionic bonding by exposure to UV radiation, plasma, or thermally. These bonds between chains are easily formed, but the crosslinking lacks stability due to the sol-gel transition caused by changes in temperature, pH, or ionic strength. Aqueous solutions of gelatin, for example, become gels when cooled but turn back into sol when the temperature is raised. Such gels are called reversible. Physical crosslinking via hydrogen bonds only occurs if the carboxyl groups are protonated, the pH thus being an important factor. The advantage of thermal crosslinking can be due to its simple design and the fact that it does not require additional chemicals or expensive equipment. Thermally crosslinked gelatin fibers exhibit a higher degree of crosslinking than plasma-treated gelatin fibers [

14]. Enzymes called transglutaminases are used for enzymatic crosslinking, which causes the formation of a crosslinked structure between free amino groups in proteins. The bonds formed by transglutaminases have a high resistance to proteolytic degradation. Enzymatic crosslinking is a suitable choice in food applications where the need for chemical crosslinking agents, as in chemical crosslinking, is eliminated. The crosslinking reaction occurs via lysine and glutamine in the collagen structure [

15].

Besides crosslinking agents and plasticizers, other active substances (e.g. antioxidants or antimicrobial substances) can be added to provide additional desired properties [

16], for example essential oils (tea tree, rosemary, clove, lemon, oregano, etc.) and bioactive compounds (bee pollen, ethanol extract of propolis, dried pomegranate extract, etc.) [

17,

18], phenolic acids (gallic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid or ferulic acid), flavonoids (catechin, flavone or quercetin) [

19], or propolis extract [

20]. Various organic acids, such as lactic or citric acid, influence the rheological properties [

21].

Biopolymer fibers can be applied in medicine. The highly porous network of fibrous materials increases cellular activity, which is vital for tissue engineering and wound dressing applications. These matrixes protect the wound from inflammation, absorb blood, and do not cause allergic reactions [

22,

23]. Besides gelatin, other biopolymers, such as collagen or chitosan, also meet these characteristics [

24,

25].

This work tested the properties of fibers prepared by centrifugal spinning from chicken gelatin. The extraction of gelatin was carried out by a patented method using a proteolytic enzyme. This work aims to characterize the properties of these fibers and compare them with fibers prepared from traditional gelatins (pork, beef) from previous studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Chemicals

Chicken gelatin (197.3±1.6 Bloom) prepared from chicken paws (Raciola, Uherský Brod, Czech Republic), porcine gelatine (198.4±2.1 Bloom), bovine gelatine (197.7±1.3 Bloom) supplied by Jelínek & syn Profikoření, Ltd., Havířov, Czech Republic, 25 % glutaraldehyde (Penta Ltd., Praha, Czech Republic). Protamex® endopeptidase (Novozymes, Copenhagen, Denmark), used for conditioning of purified collagen.

2.2. Appliances and Tools

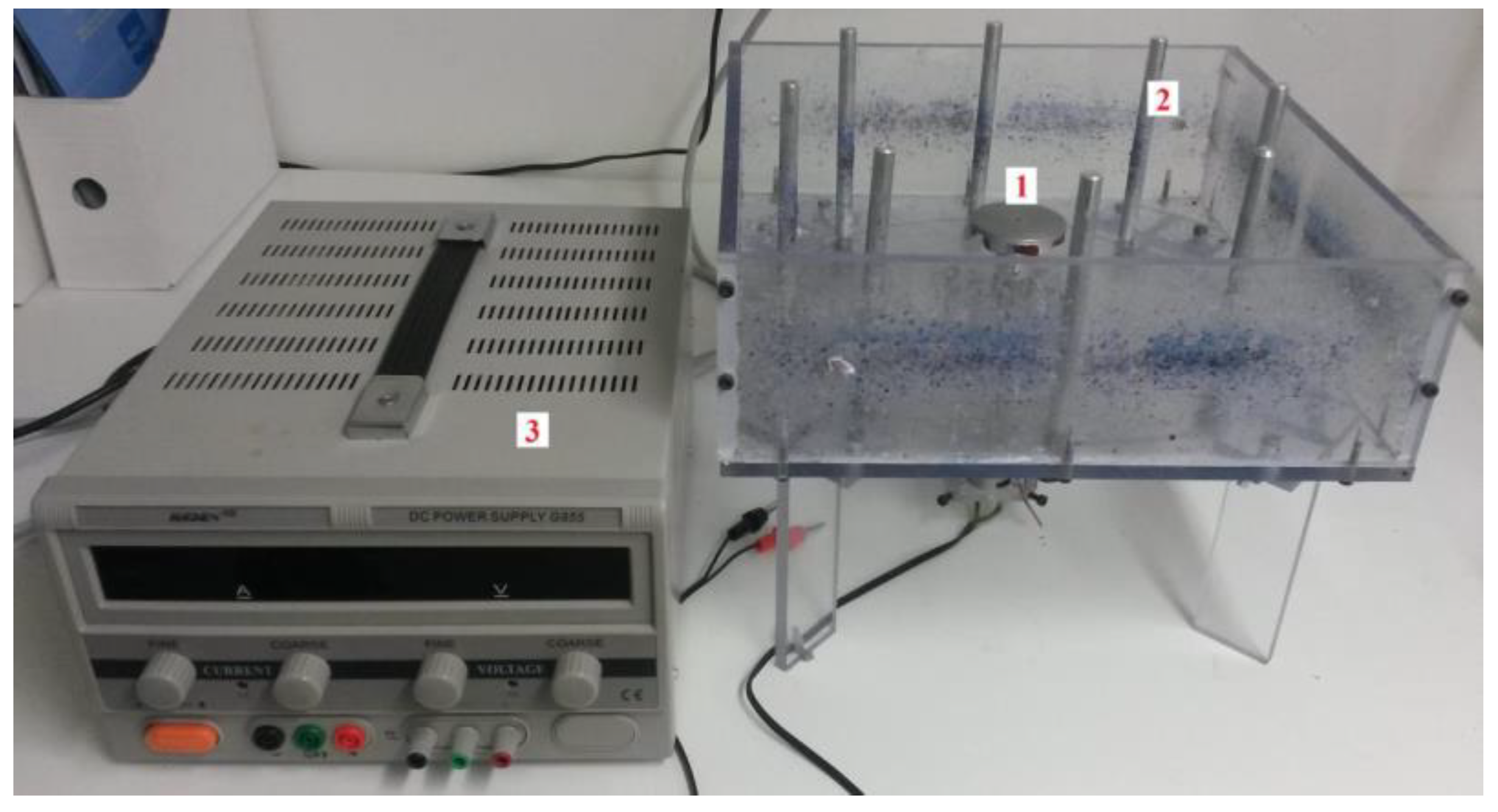

Needle-free spinning device assembled at the Department of Nonwovens and Nanofibrous Materials, Faculty of Textiles, Technical University of Liberec (Liberec, Czech Republic), see

Figure 1. Centrifugal spinning was carried out on portable laboratory equipment using the needle-free fiber production principle. This device comprises a collector of eight metal rods arranged in a 260 mm diameter circle. In the center of the circle is a spinneret, a flat disk 50 mm in diameter. The spinneret is driven by a DC motor, which is connected to a laboratory power supply with adjustable voltage and current to control the magnitude of the rotation and, thus, the peripheral speed of the rotating disk. The spinning system is housed in a polycarbonate (PC) box, which protects fibers flying out. The following have also been used: scanning electron microscope Phenom XL-G2 (Termo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic), Bruker ALPHA (Billerica, MA, USA), Scale Kern 440-49 N (Kern & Sohn GmbH, Balingen, Germany) and other laboratory equipment.

Table 1 shows the dependence of the speed of a 50 mm diameter spinneret on the electrical voltage. This conversion table was measured using a non-contact speedometer. Each device's corresponding peripheral speeds and the electric voltage's selected values are highlighted in the same color.

2.3. Processing of Chicken Paws into Gelatin

Gelatin was prepared by a biotechnological process from chicken paws according to Patent CZ 307665—Biotechnology based production of food gelatin from poultry by-products [

27]. Separation of soluble proteins (albumins, globulins) from chicken paws was performed according to the procedure from a previously published work, only with minor modifications [

28]. The tissue was then defatted in a 1:1 mixture of ethanol and petroleum ether. The raw material was shaken with the above mixture in a ratio of 1:6 for three days, with the solvent being changed every 24 hours. Purified collagen was mixed with distilled water in a ratio of 1:10; the pH was adjusted to 6.5–7.0. Then, the proteolytic enzyme Protamex

® was added in an amount of 0.4% to the collagen dry matter, and the mixture was shaken for 15 h. Conditioned collagen was mixed with distilled water in a ratio of 1:8; gelatin was extracted at 65±0.4 °C for four h; gelatin solution was dried at 55±0.4 °C in a thin film [

6].

2.4. Fibres Preparation

The fiber formation process was carried out as follows. Firstly, a laboratory power supply was switched on and connected to a DC motor to drive the spinneret, which began to rotate. The required electric voltage (6 V or 10 V) and the speed of the spinneret were set on the laboratory power supply. A polymer gelatin solution with a volume of 20 mL, a concentration of 40±0.3%, and a temperature of 60±0.2 °C was gradually injected into the center of the rotating spinneret using a syringe of the same volume for 120 s. Initially, no fibers were formed. At first, a continuous polymer film "with fingers" formed on the disk, and as the amount of solution dosed increased, fibers began to appear at the edge of the collector. Centrifugal spinning on a needle-free device and subsequent drying of the fibers prior to removal from the collector was carried out at 21.9±0.3 °C and 33.1±0.2% relative humidity. Half of the pork, beef, and chicken gelatine fiber samples were crosslinked in a desiccator with glutaraldehyde vapor for three days at 21.5±0.5 °C.

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

For each sample, the spectra were measured using a Bruker ALPHA infrared spectroscope with Fourier transformation using the ATR method with a platinum crystal. The samples were exposed to infrared light in the wavelength range from 400 to 4000 cm-1. A total of 32 images were taken during one measurement.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Samples were imaged using a Phenom XL-G2 scanning electron microscope at 330x magnification. The accelerating voltage used was 10 kV. For better imaging, the samples were powder coated with a thin layer of gold-palladium mixture [

29,

30,

31].

2.7. Swelling and Solubility

Samples of 1.5 cm x 1.5 cm were weighed and washed with 20 mL of demineralized water for 10 min, 30 min, 60 min, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h at 21.5±0.5 °C. After being removed from the container, they were weighed again and placed in a dryer at 60.0±0.6 °C for two h and weighed again.

The swelling index is determined as the quotient of the weight after removal from the container of water and the initial weight of the sample. Solubility is also a dimensionless quantity given as a percentage calculated as the quotient of the weight loss between the initial and final values.

3. Results

3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

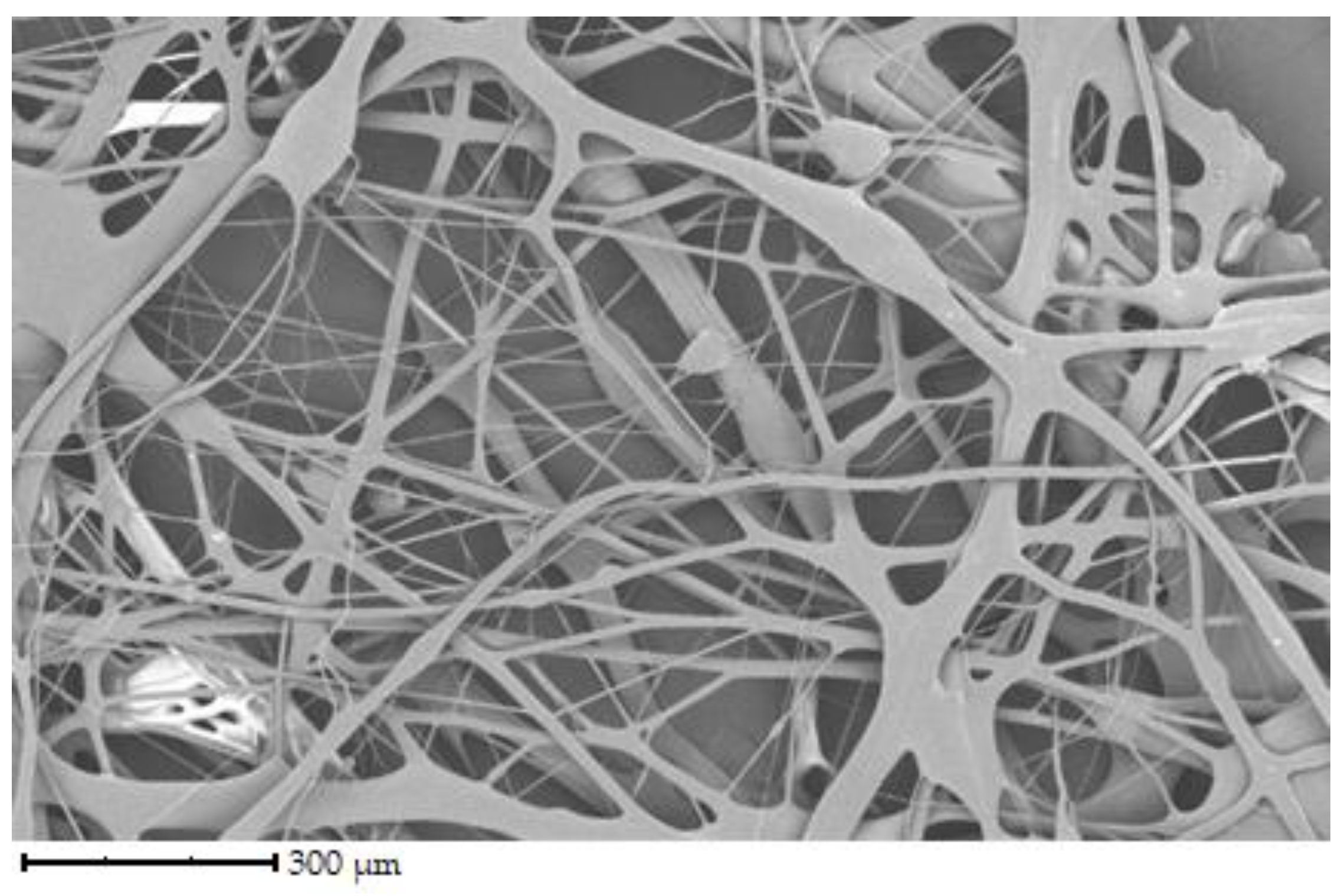

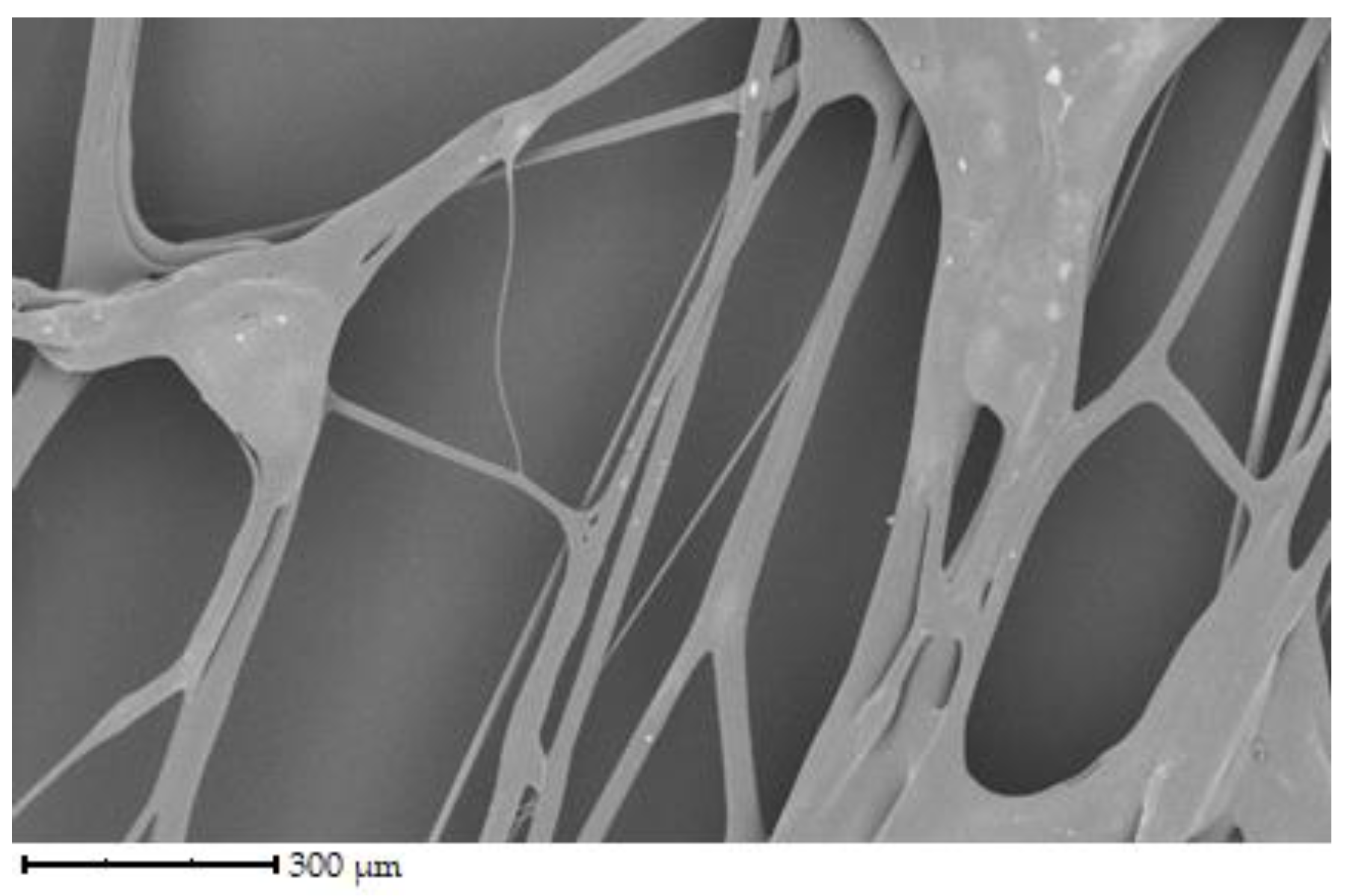

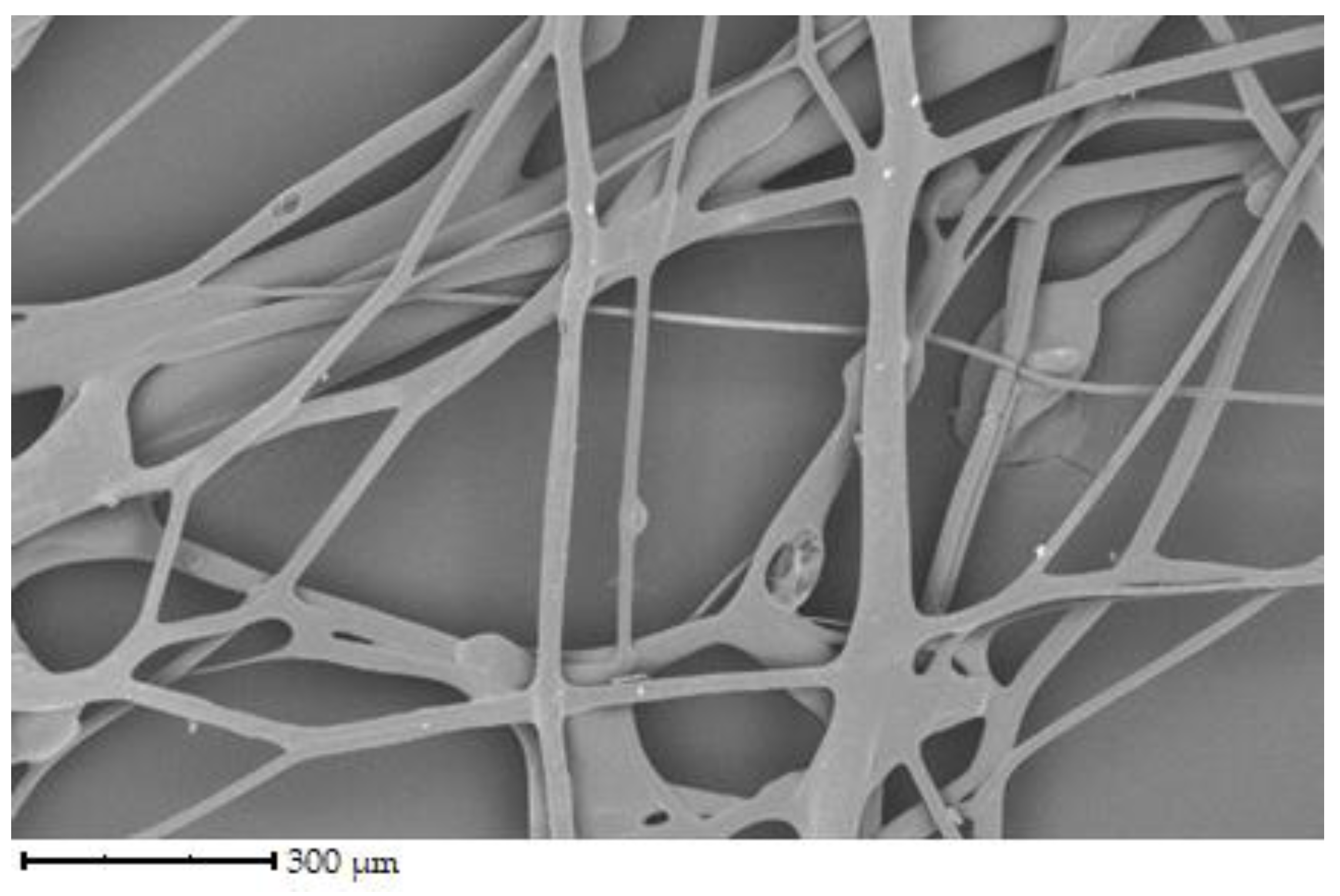

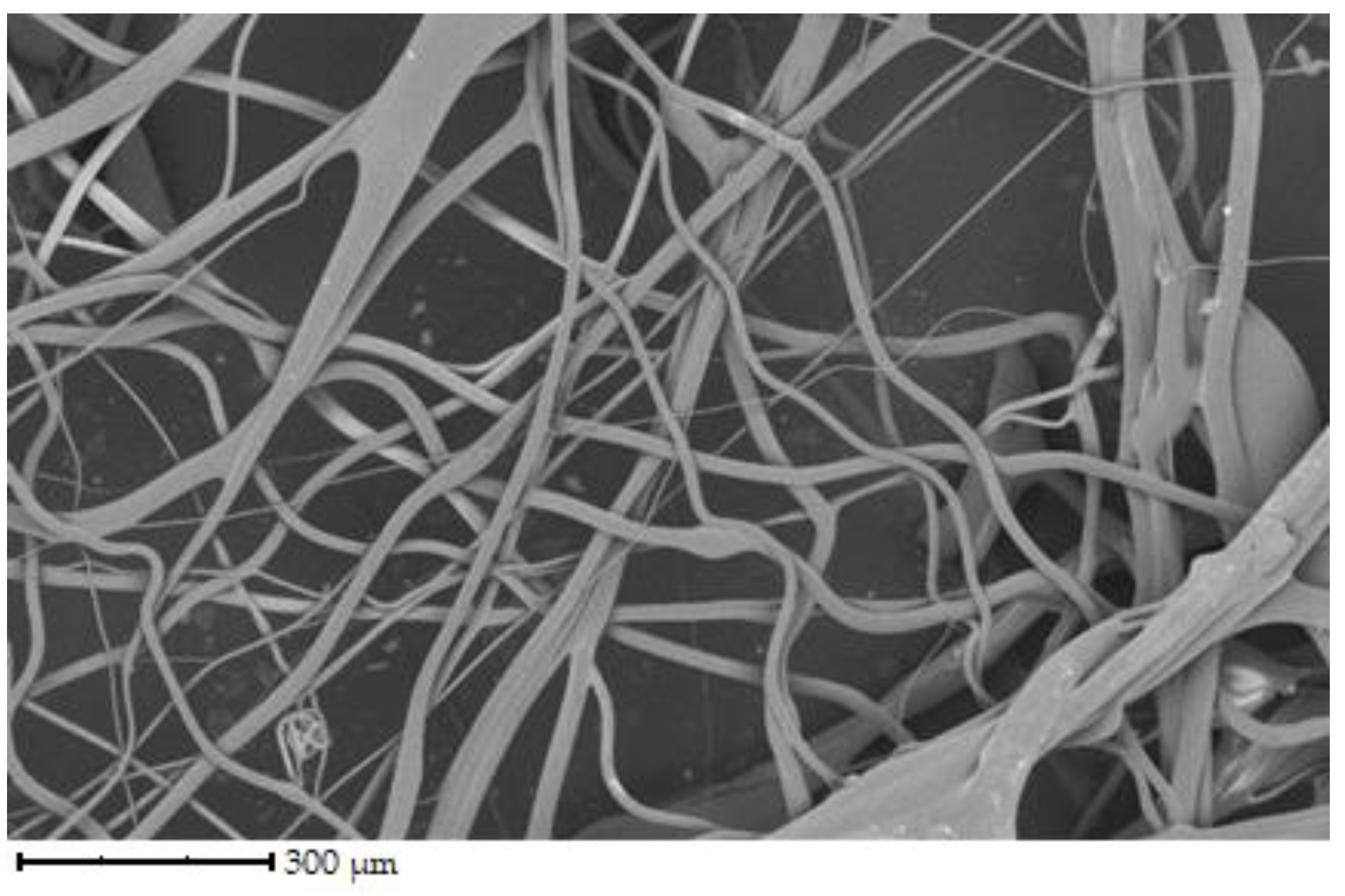

The initial set of samples shows the structure of uncross-linked fibers from chicken, porcine, and bovine gelatin that were not further crosslinked (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Figure 2 shows the fiber structure of chicken gelatin. The fibers form an interconnected network. The diameter of the fibers ranges from 1 to 100 µm. According to the image, the fibers are straight and curved, have different directions, and have a smooth surface. Compared to the other samples, this is the densest network, yet there are spaces between the fibers.

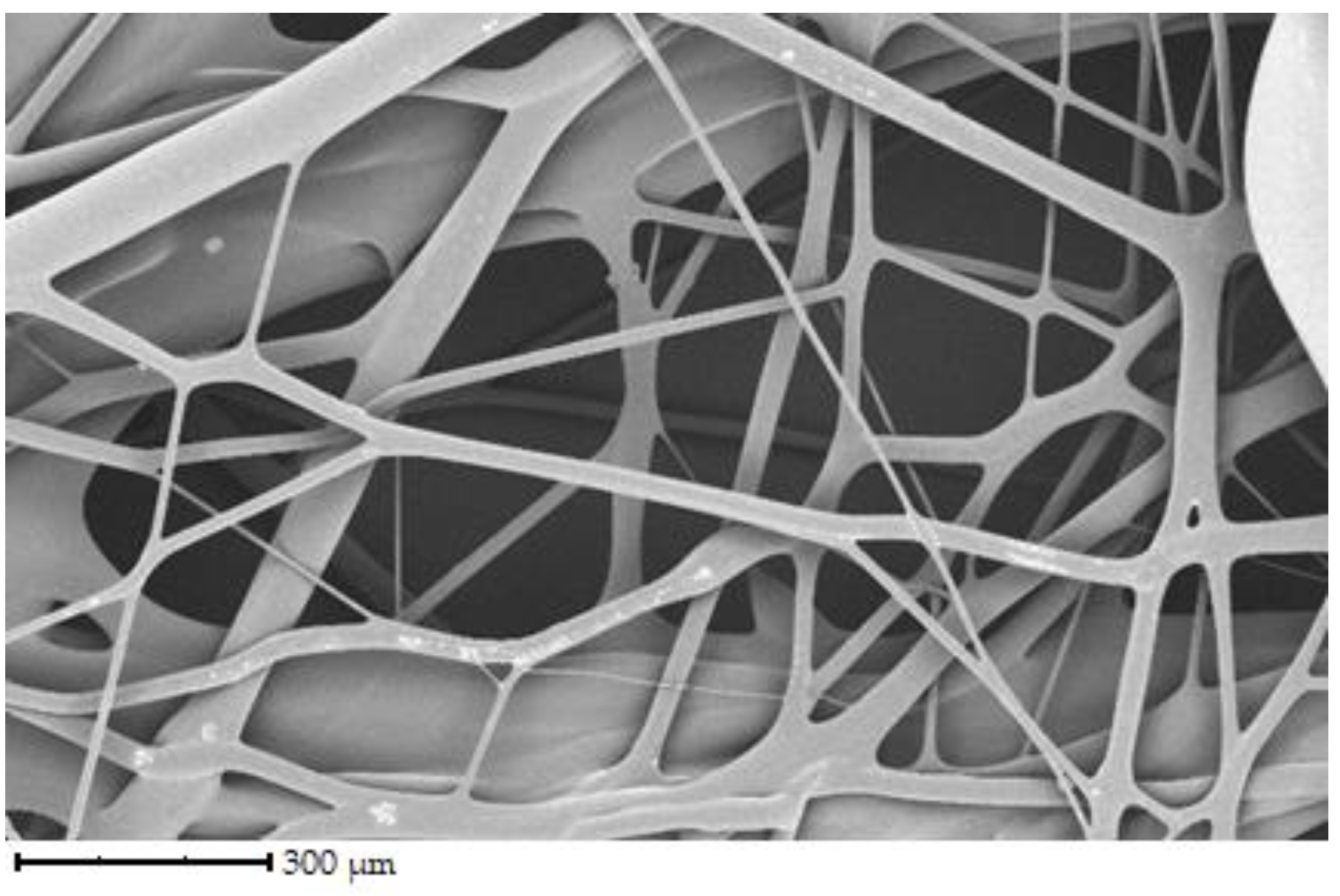

Figure 3 shows the fibers of porcine gelatin. Compared to chicken gelatin, the fibers have a larger diameter, lower density, and therefore greater spacing. The structure is as disordered regarding the direction of the fibers as in the previous case, but the network is not so interwoven. According to the image, the surface of the fibers is smooth, and the fibers are straight, without primary curvatures.

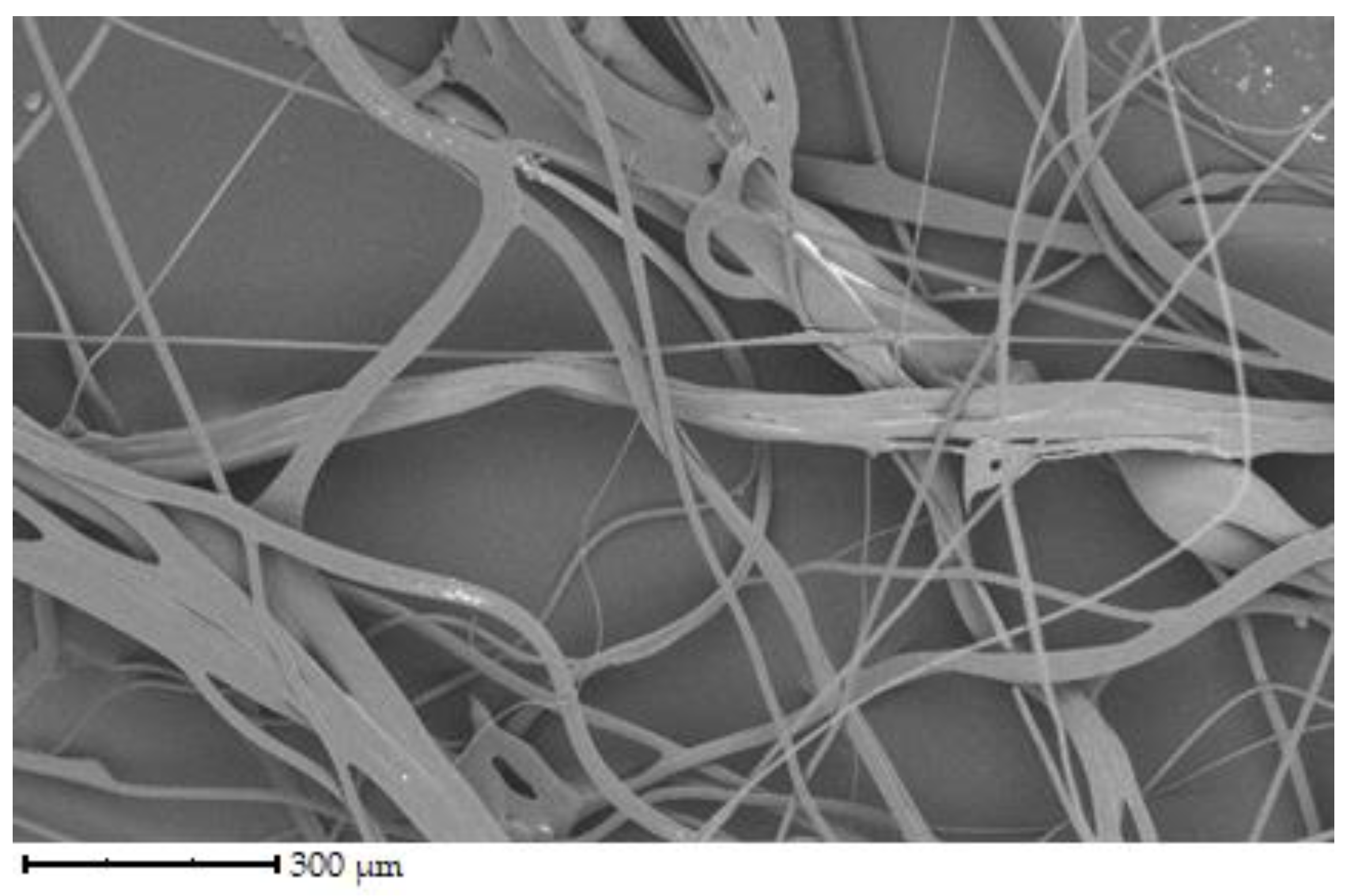

Figure 4 shows fibers of bovine gelatin. Fiber diameter is similar to the previous sample of pork gelatine. According to the image, the fiber density is higher than porcine gelatin but noticeably lower than that of chicken gelatin.

The second set of samples shows chicken, porcine, and bovine gelatin fibers crosslinked with glutaraldehyde vapor (see

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). It is evident from the images that the crosslinking does not affect the morphology observed in the images. It is done to improve the mechanical and physical properties of the material. The structure and diameter of the fibers are similar to the previous series of samples.

The fibers have different directions and are interwoven. The diameter of the fibers ranges from 1 to 100 µm. The denser network is made up of chicken gelatin. The fibers are smooth in all cases, with a few exceptions.

The prepared fibers have a larger diameter than nanofibers from other studies. The different methods of preparation of the polymer spinning solution may cause this fact. The speed of centrifugal spinning may also influence the diameter and overall morphology of the fibers. Traditionally, gelatin is spinned from an acetic acid solution [

32], or a mixture of acetic acid and formic acid [

33]. For this study, it was a 40% aqueous solution of gelatin.

Gungor et al. studied the effect of spinneret speed and solution concentration on the formation, shape, and arrangement of gelatin nanofibers. Gelatin fibers were prepared from a solution of bovine gelatin in acetic acid. The best quality fibers were obtained by combining a 20% gelatin solution and a rotation speed of 7000 rpm [

32]. Mîndru et al. observed the effect of airflow on the preparation of gelatin fibers from a mixture of acetic and formic acid. Fibers with diameters ranging from 2 to 12 µm were prepared by this method. [

33].

Chaochai et al. prepared gelatin fibers by spinning them from aqueous gelatin solution. Crosslinking was carried out using denacol and glutaraldehyde vapor. Fiber diameters were around 60 μm [

34]. Nagura et al. spinned bovine gelatin from a 20% aqueous methanol solution. Heat treatment immediately crosslinked the fibers under vacuum and immersion in various epoxy compounds such as ethylene glycol, diglycidyl ether, etc. They also prepared the fibers from an aqueous solution of citric acid. According to the results obtained, these fibers exhibit considerable mechanical strength and water resistance [

35]. Arai et al. have developed a method of producing gelatin fibers by coacervation. They produced narrow gelatin fibers with a diameter of over 10 μm and were able to shape them further [

36]. Arican et al. prepared gelatin nanofiber masks. They evaluated the morphology, porosity, and fiber diameter in relation to solution concentration and rotation speed [

37].

3.2. FTIR analysis

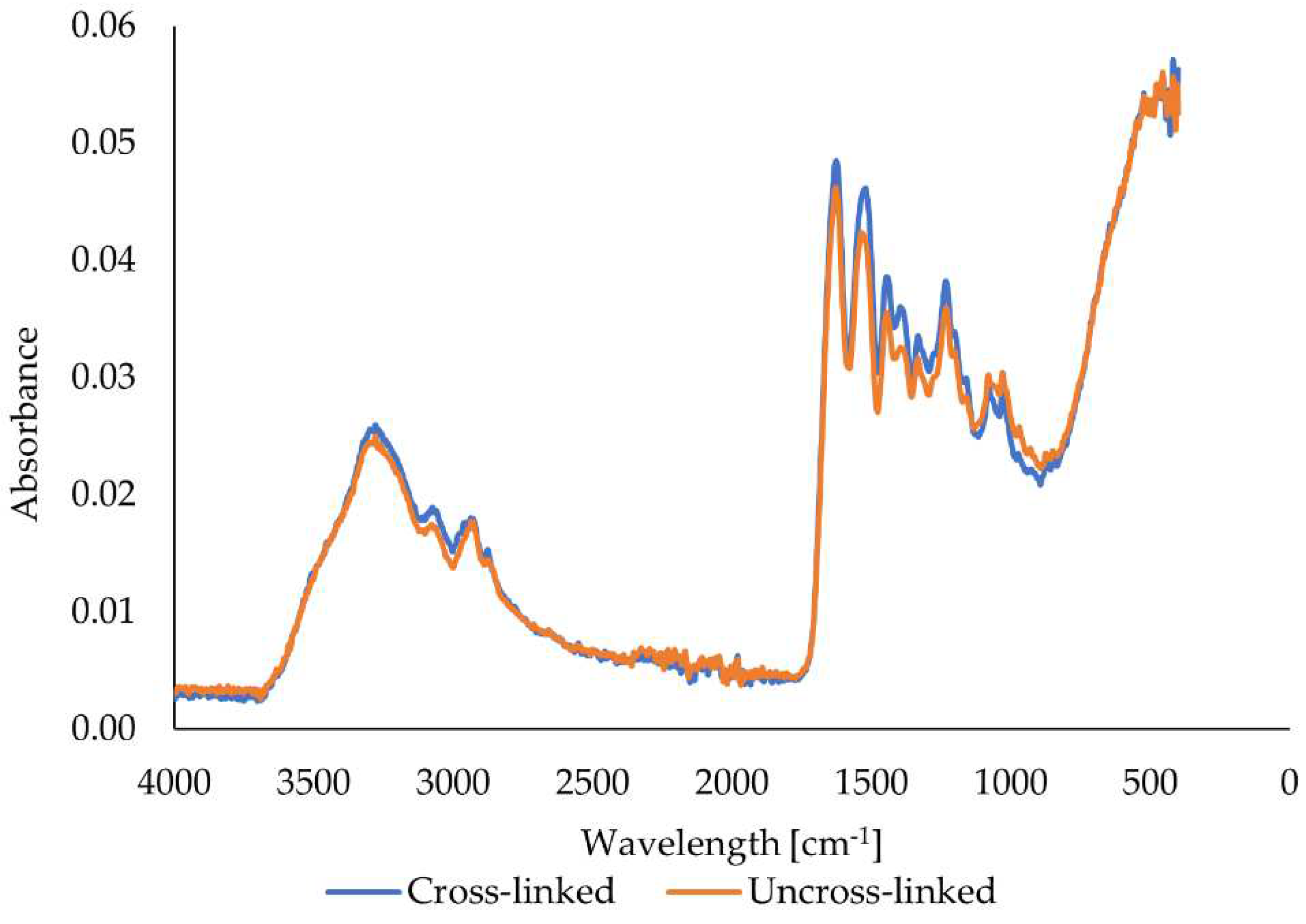

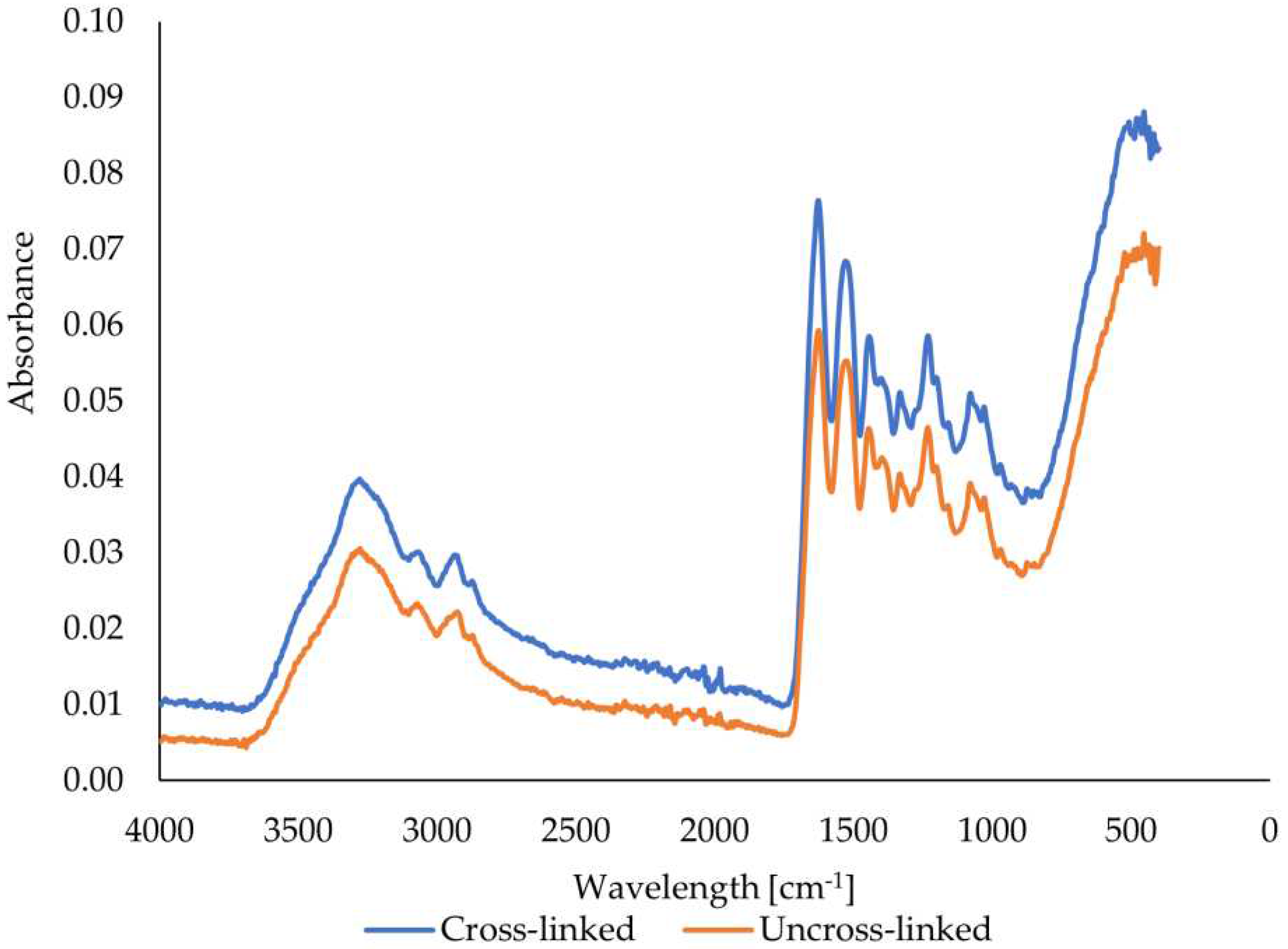

The FTIR method observed the effect of glutaraldehyde crosslinking on functional groups in gelatin fibers (see

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Each figure compares the spectrum of uncross-linked and crosslinked fibers depending on the origin of the gelatin.

Figure 8 shows that the peaks in the spectrum of the scanned beef gelatin fibers are located in the bands around 3278, 1628, 1537, and 1243 cm

-1. These values correspond to amide A (stretching and oscillation of N-H), amide I (oscillation and stretching of C=O and C-N bonds), amide II (N-H bending), and amide III (bending of N-H bonds) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The band around the amide I peak comprises stretching vibrations of C=O (70–85%) and C-N (10–20%) bonds. Amide I is considered the most efficient peak for protein structure analysis using infrared spectroscopy. The exact position of the amide I band depends on the hydrogen bridges and the conformation of the protein structure. In general, most proteins have multiple types of secondary structure (α-helix, β-sheet, or random structure) simultaneously, so the peak in the amide I band often shows multiple arms. The range and intensity of the amide II peak are generally much more sensitive to hydration than to changes in secondary structure [

41,

42]. The FTIR spectra of the bovine gelatin fibers show an increase in the intensity of all peaks when comparing the uncross-linked and crosslinked samples. However, the increase in intensity is not significant. An increase in intensity, even if only slight, implies the formation and presence of more bonds, which are characterized by specific wavelengths resulting from cross-linking. The graph also shows that no new peaks were formed, as the shape of the two curves is almost identical except for slightly different peak intensities.

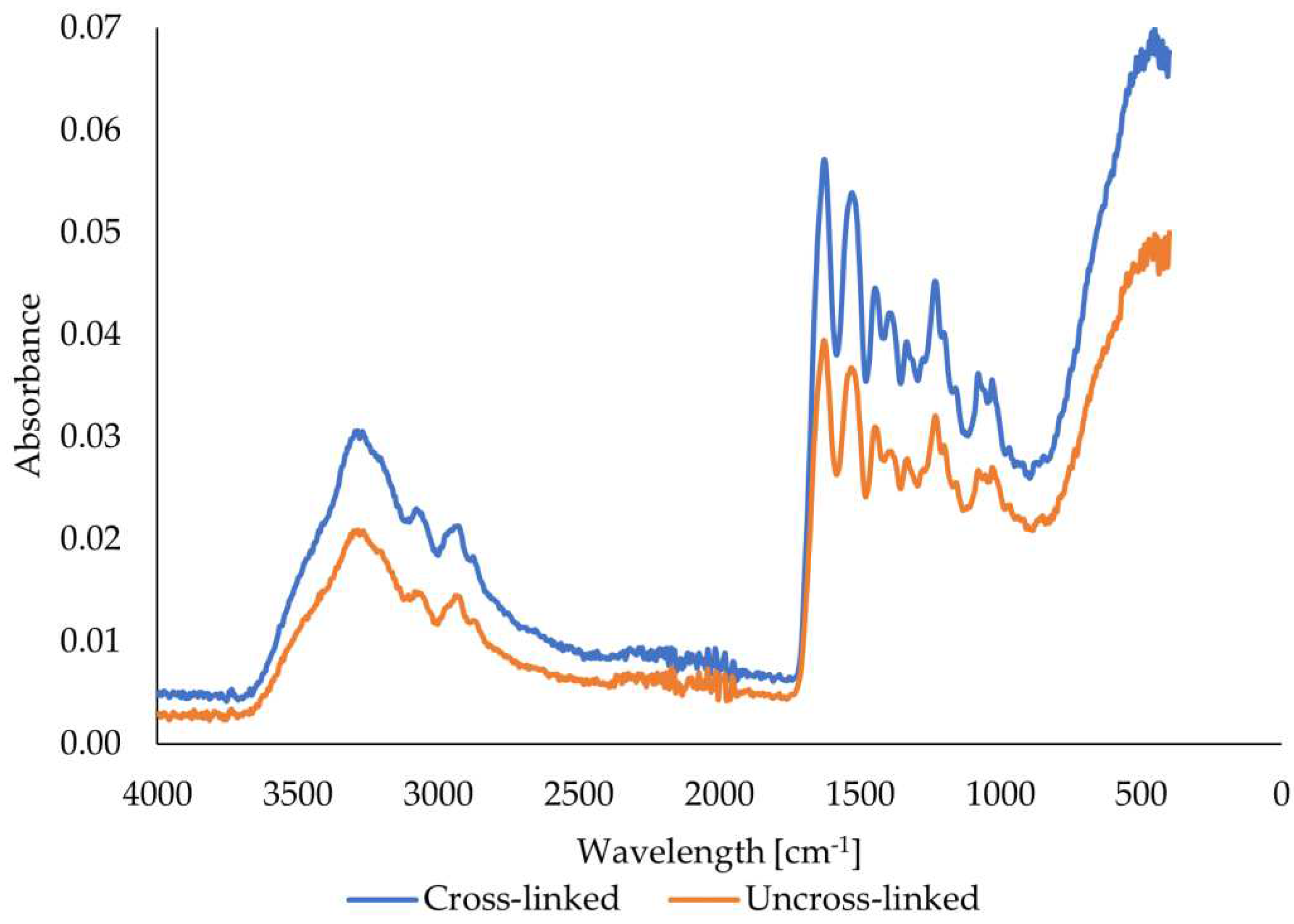

The peaks in the spectrum of the scanned pork gelatin fibers (

Figure 9) are located in the bands around 3278, 1628, 1528, and 1232 cm

-1. These peaks, in bands similar to those in the bovine gelatin fiber spectrum, correspond to amide A (stretching and oscillation of N-H), amide I (oscillation and stretching of C=O and C-N bonds), amide II (N-H bending), and amide III (bending of N-H bonds) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The FTIR spectra of the porcine gelatin fibers show an increase in the intensity of all peaks comparing the uncross-linked and crosslinked samples. The increase in intensity is significant in contrast to the fibers from bovine gelatin. The increase in intensity implies the formation and presence of more bonds, which are characterized by specific wavelengths resulting from cross-linking. The figure also shows that no new peaks were formed here either, as the shape of both curves is almost identical except for the different peak intensities.

The peaks in the spectrum of the scanned chicken gelatin fibers (

Figure 10) are located in the bands around 3270, 1628, 1529, and 1232 cm

-1. These peaks, in bands similar to those in the spectra of bovine and porcine gelatin fibers, correspond to amide A (stretching and oscillation of N-H), amide I (oscillation and stretching of C=O and C-N bonds), amide II (N-H bending) and amide III (bending of N-H bonds) [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The increase in intensity is significant compared to bovine gelatin fibers. The increase in intensity implies the formation and presence of multiple bonds, which are characterized by specific wavelengths resulting from cross-linking. The figure also indicates that no new peaks were formed in this case either, as the shape of both curves is almost identical except for the different peak intensities. All prepared fibers show peaks in the same wavelength regions regardless of the origin of the gelatin and the use of a cross-linker, differing only in intensity.

3.3. Swelling and solubility

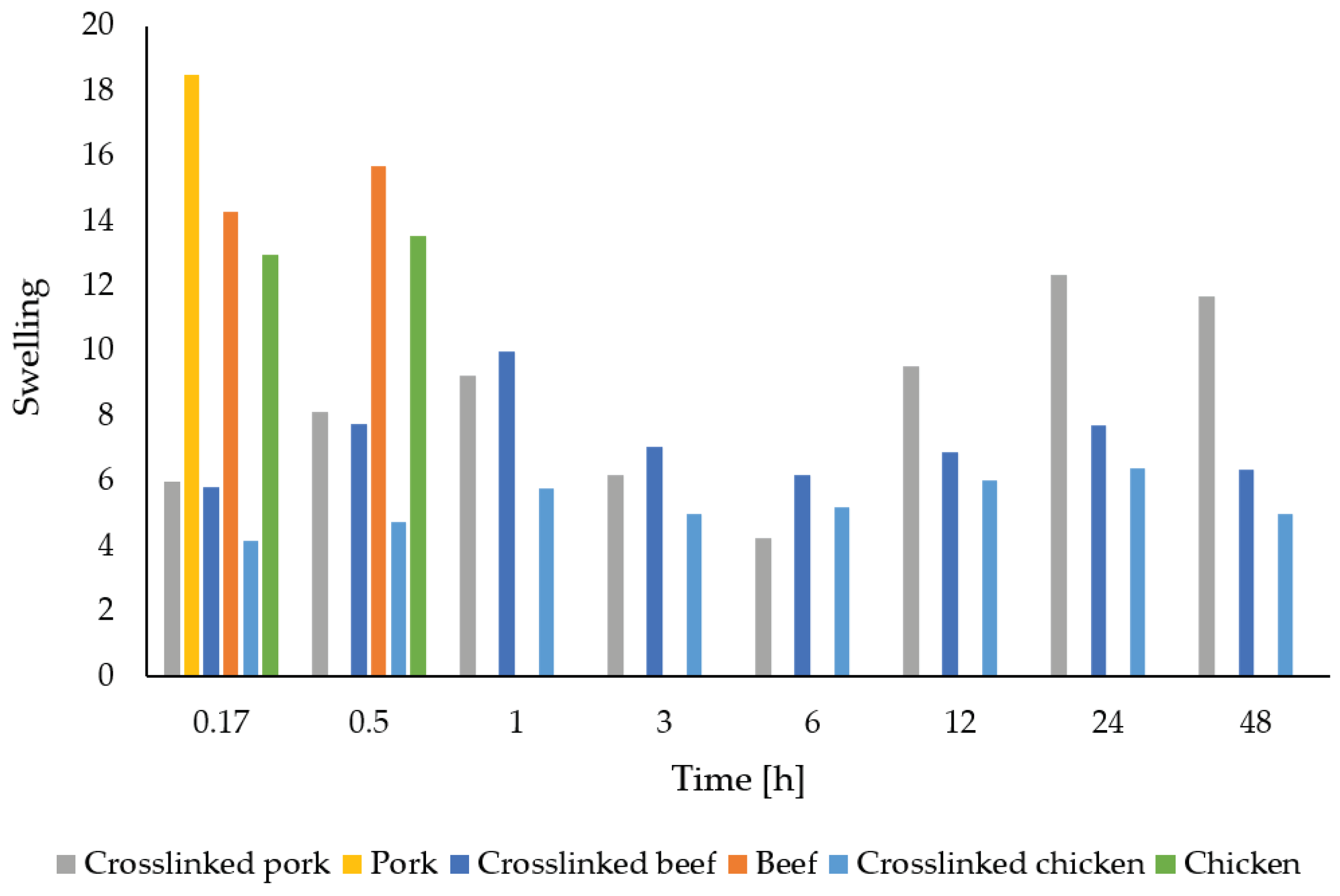

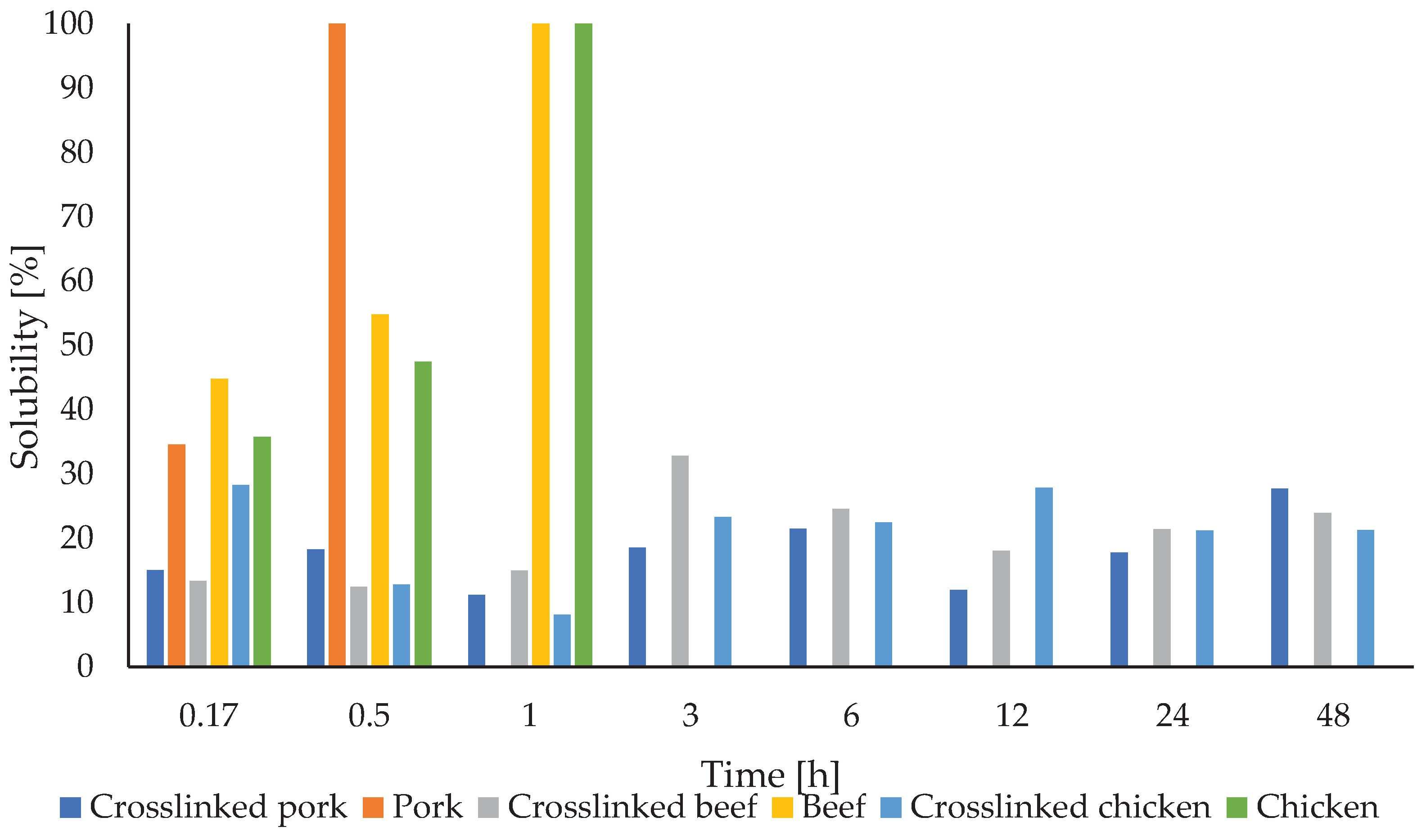

Table 2 reports the results of swelling and solubility of gelatin fibers depending on the origin of the source material and the presence of a cross-linker.

When immersed in distilled water at laboratory temperature, uncross-linked porcine gelatin fibers interact with water relatively quickly, swell, and the fiber structure disintegrates. With time, the entire sample dissolves in the water. In this case, the solubility is the most rapid of all the samples studied. The effect of glutaraldehyde vapor crosslinking on fiber stability is noticeable. Water is absorbed when the sample interacts with water, and its weight increases. However, the structure of the fibers, unlike in the case of the uncross-linked samples, remains preserved even after subsequent drying of the sample. The swelling values increased throughout the experiment as the swelling rate increased with increasing immersion time. The highest swelling rate was observed when the sample was immersed in water for 24 hours. On the contrary, the lowest increase in weight occurred at six hours of exposure to water.

When immersed in distilled water at laboratory temperature, uncross-linked bovine gelatin fibers interact with water relatively quickly, swell, and the fiber structure breaks down. The swelling index is approximately twice that of crosslinked samples. Over time, the entire sample dissolves in the water; after only 10 minutes of immersion, the sample loses almost half of its weight, especially its fibrous structure. Again, the effect of glutaraldehyde vapor crosslinking on the stability of the fibers is noticeable. When the sample is immersed in water, its weight increases due to water uptake. The fiber structure is stable even after subsequent drying of the sample. The swelling values of the bovine gelatin fibers were around the same value throughout the experiment and did not increase in relation to the time of immersion of the sample in water. The highest swelling rate was observed when the sample was immersed in water for 1 hour. Conversely, the lowest weight increase occurred at the shortest contact with water. For solubility, it was similar to swelling; this parameter also did not show a significant increasing trend with increasing exposure time. The highest solubility was found when immersed in water for 3 hours, while the lowest losses were observed when immersed in water for 30 minutes.

When immersed in distilled water at laboratory temperature, uncross-linked chicken gelatin fibers interact with water relatively quickly, swell, and the fiber structure disintegrates. Over time, the entire sample dissolves entirely in the water. The use of a cross-linker has a significant effect on the stability of the chicken gelatin fibers. Water is absorbed when the sample interacts with water, and its weight increases. However, the structure of the fiber is preserved even after subsequent drying of the sample. The swelling values were around the same value throughout the experiment and did not increase about the time of interaction with water. The highest swelling rate was observed when the sample was immersed in water for 24 hours. Conversely, the lowest weight increase occurred with the shortest exposure to water. For solubility, it was similar to swelling; this parameter also did not show a significant increasing trend with increasing exposure time. The highest solubility was observed when interacting with water for 10 minutes, while the lowest losses occurred when immersed in water for 1 hour.

The comparison of gelatin fiber swelling is better visualized in the graphical representation (

Figure 11). The fibers from crosslinked chicken gelatin have, with one exception, the lowest weight increase. A sinusoidal curve is also evident for the crosslinked fibers.

Figure 12 shows more clearly the evolution of solubility over time. Again, the solubility rate has a variable character for the crosslinked samples. Fibers from crosslinked chicken gelatin have comparable solubility to bovine and porcine.

Nagura et al. observed the effect of cross-linkers on the swelling of gelatin fibers. They compared the change in fiber length before and after the experiment. The lowest swelling was observed when crosslinking with citric acid, while the highest increase in fiber length was observed when using diglycerol-triglycidyl ether in a pH [

35].

Gill et al. crosslinked gelatin fibers with glyoxal and observed the effect of crosslinking time and cross-linker concentration on the swelling of the sample. Again, they focused on the change in fiber length. The swelling decreased with increasing cross-linker concentration and with increasing crosslinking time [

43].

Padrão et al. prepared fibers from fish gelatin crosslinked with glutaraldehyde vapor. In this study, they defined swelling as weight gain. Within 5 minutes, the fiber reached its maximum water absorption and no longer increased in weight [

44].

Etxabide et al. crosslinked gelatin fibers by ribose Maillard reaction; besides the influence of cross-linker concentration, they observed the effect of glycerol content as a plasticizer. Swelling values (defined as weight increase) were similar among the samples and generally higher than our results. Similar to our study, solubility was defined as weight loss compared to the original weight. The solubility values are very similar to those in our study. Uncross-linked fibers were completely dissolved, while for crosslinked samples, the dissolution loss was between 10 and 20% [445].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.; methodology, J.M. and P.M.; software, J.M; validation, P.M, J.M. and P.P.; formal analysis, J.M.; resources, R.G.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, P.M. and R.G.; visualization, P.M.; supervision, P.P..; project administration, J.M. and P.M.; funding acquisition, J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.