1. Introduction

The concept of "visual preference" could be interpreted as a psychological assessment of the observed human interaction with the environment [

1,

2]. In essence, people evaluate their surroundings and respond to them in terms of affective reactions [

3]. In the context of visual preference in highway landscapes, the focus lies on the interaction between road users and the scenery outside their windows while traveling at high speeds [

4]. For highway users, a journey becomes exhilarating when the highway offers scenic vistas with a high preference level and showcases unique landscape elements [

5]. This includes the impact of roadside landscaping on road users and their ability to navigate, control, and enjoy their journeys [

2]. Therefore, highway landscapes must provide road users with a comfortable, pleasant, safe, and visually appealing environment for driving and relaxation [

5,

6].

The highway landscape includes all forms of landscapes that drivers or passengers may encounter along the highway [

5]. These landscapes are characterized by undulating terrain, rich flora and fauna, water resources, man-made elements, and solid natural ecology [

7]. Besides, it symbolizes the harmony of highway design and construction with the original natural environment and the additional man-made landscape of the surrounding area [

8]. Specifically, highway landscape elements are not just physical components but key contributors to the overall highway landscape aesthetics. They play a crucial role in shaping visual landscape scenes and offer valuable insights for aesthetic analysis [

2]. Highway landscapes are also a good indication of preserving and evolving local culture, offering intrinsic character and diversity that contributes to regional cultural identity [

5,

8]. This cultural resonance plays a pivotal role in shaping visual preference [

4].

However, visual preferences have changed dramatically in recent years. In particular, urbanization has increased in recent decades, affecting people's preferences and perceptions of landscapes [

9]. Urbanization has radically altered the composition and arrangement of land uses and progressively transformed traditional rural landscapes into urban ones [

10]. Similarly, as urban areas rapidly grow and develop, mass transportation becomes essential, leading to the construction and expansion of roads and highways [

11]. While highways are built to cater to human needs, their construction often has detrimental effects on the natural surroundings, especially in terms of land coverage and ecosystem improvement [

12,

13]. Notably, highway development frequently disregards or destroys valuable natural and historical landscapes, resulting in the loss of precious areas [

14]. Martín et al. [

8] have also verified the construction of a major highway can have profound implications for the environment and resources of a region, leading to a dramatic transformation of the area's landscape ecology and scenic beauty. Moreover, highway infrastructure has contributed significantly to environmental change, manifesting in alterations in land use, cover, and the loss of green areas [

14]. Unfortunately, many highways have been constructed without proper visual preference assessment and consideration of the surrounding environment, damaging and losing valuable visual landscapes [

13]. Hence, evaluating visual preference becomes crucial when considering constructed highways and their adjacent landscapes or those currently undergoing construction.

While the growth of transportation systems has afforded individuals more travel options, the visual preference for road landscapes, particularly on highways, has not received sufficient attention. Although evaluation criteria have been briefly in the literature, there is no unified and complete criterion for assessing the preference for highway landscapes. Therefore, this research aims to systematically review the existing literature on the evaluation of preference for highway landscapes and subsequently formulate comprehensive criteria for such evaluations. To comprehensively capture these criteria, it is necessary to examine the relationship between highway landscapes and users, user’s preference for highway landscapes, preference approaches, and variables used in preference.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Keyword Selection

The search for the selected keywords could be divided into visual preference assessment and highway landscape. In the realm of visual preference assessment, keywords such as "visual preference," "visual perception," "preference assessment," and "perception assessment" have been included in the systematic literature review. Landscape preferences could be seen as a combination of biophysical characteristics of the environment and human perceptions [

15]. To some extent, perception offers the sensory input and initial interpretation of the environment [

16]. On the other hand, preference reflects individual inclinations and choices based on that interpretation [

17]. In the field of landscape studies, visual perception research delves into the fundamental concept of beauty, exploring aspects such as goodness, attractiveness, and preference [

18]. The relationship between the two is complex, with each influencing and shaping the other in a constant feedback loop. Hence, “visual perception” was also added to keywords.

In the case of highway landscapes, the search was conducted by entering only “highway landscape” or “highway landscape character,” which yielded a limited number of results. To increase the credibility of the research findings, the search criteria were extended to include “road landscape” and “street landscape.” This broader inclusion is justified by the recognition that road landscapes are inherently linear, following the path of a road or highway [

14]. This linearity influences the traveler's visual experience and shapes the landscape's composition [

12]. Therefore, “highway landscape,” “highway landscape character,” “road landscape,” and “street landscape” were added to the systematic literature review search. To summarize, the keywords of the systematic literature review in the search were “visual preference" OR “visual perception” OR "preference assessment" OR “perception assessment” AND "highway landscape character" OR "highway landscape" OR “road landscape” OR “street landscape.”

2.2. Relevant Literature Screening

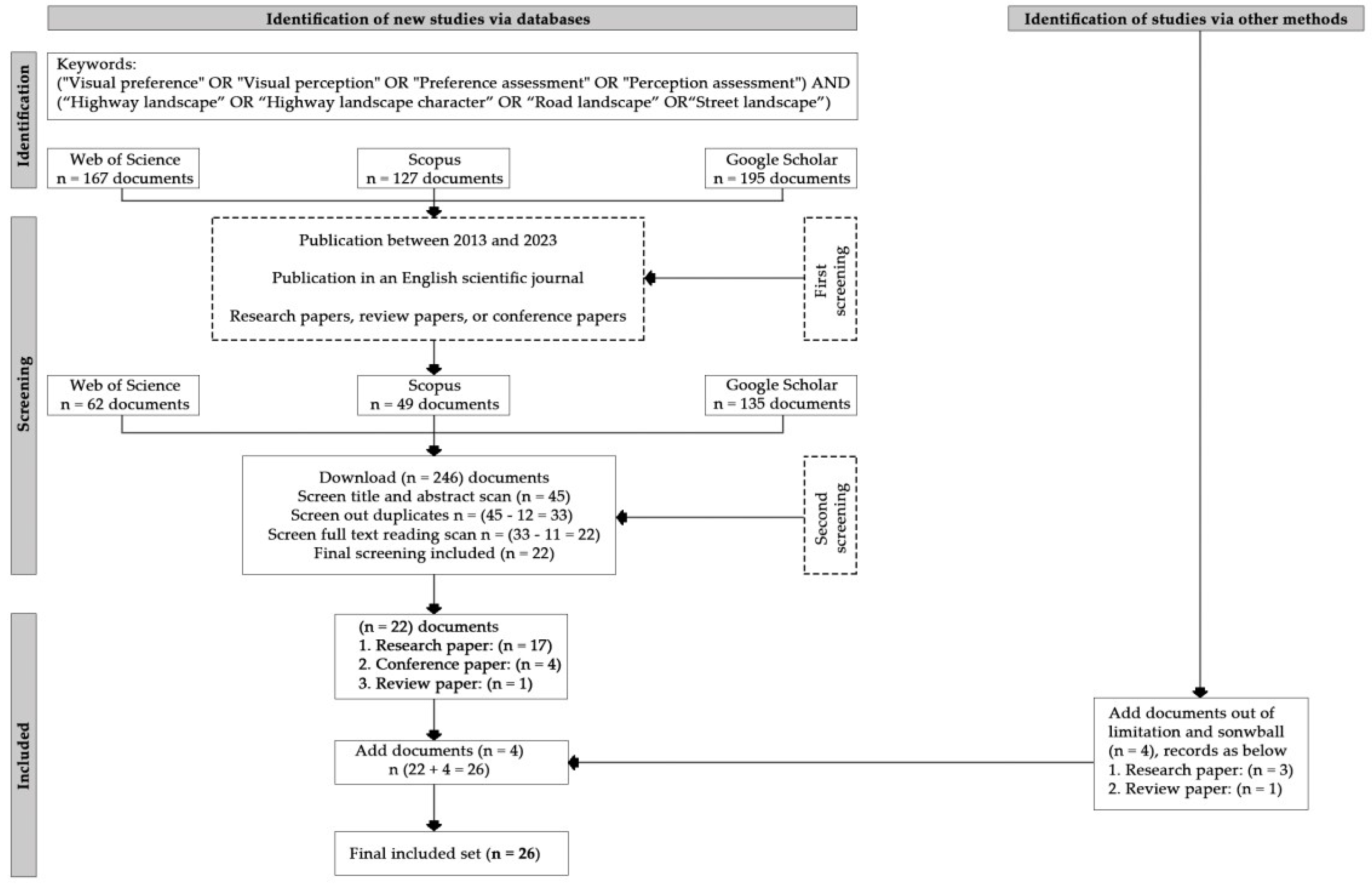

The methodology used to screen the relevant literature for this study was based on a keyword search and followed the guidelines of a systematic literature review (

Figure 1). Initially, three databases -Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar- were chosen to screen the literature preliminarily. Articles meeting the following criteria were selected for inclusion in this study: (1) publication between 2013 and 2023; (2) publication in an English scientific journal; (3) classified as research papers, review papers, or conference papers. The time period from 2013 to 2023 was selected due to a significant increase in the number of research studies focusing on the visual quality of road landscapes, especially from 2013 onwards. After screening and examining papers based on the given criteria, 22 out of 246 papers finally met the final requirements. To supplement this limited number of studies, the "snowballing" approach was employed. This technique helps to comprehensively gather topic-specific resources and expand the literature review, ensuring that the systematic review captures relevant information extensively. Typically, relevant literature is typically added by reviewing the references and citations of the selected papers. In this context, four relevant papers have been added. Although these papers were published earlier than 2013, they are highly relevant to this review. Each of these papers discusses the connection between highway landscapes and preferences, making them valuable additions to the overall literature. Finally, 26 papers were ultimately selected – 20 research papers, four conference papers, and two review papers published between 2003 and 2023.

2.3. Data Collection

For this study, a thorough analysis and reading were conducted on the selected articles, and the related information was gathered and organized in an Excel spreadsheet. The recorded information consists of several elements, such as the author's name, publication date, title, research question and objectives, research methodology, variables, limitations, and other relevant aspects. A comprehensive overview of the collected data is presented in

Appendix A;

Table A1, and

Table A2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the literature screening process for systematic search reviews.

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the literature screening process for systematic search reviews.

3. Results

3.1. The Relationship between Highway Landscape and Users

Roads are widely acknowledged as the primary way of experiencing and understanding contemporary-day landscapes, presenting an initial understanding of the geography of the locations visited [

19]. The highway, as a medium for the combination of the natural landscape and man-made structures, emphasizes the importance of landscape design and environmental regeneration [

20].

A highway with scenic and unique landscape characters could delight highway users’ visual experience. The enhanced visual appeal and diverse environment around the road also help users better understand the connection between the roadway and its surroundings [

5,

21]. Besides, this pleasure experience actually stems from the ability of individuals in a state of high-speed driving to freely exchange visual information with the landscape outside via the window [

4]. The landscape's aesthetic appeal perceived by highway users depends on the physical and psychological distance between the observer and the landscape [

2]. Constructing an aesthetically pleasing and acceptable road or line of vision requires careful consideration of the initial elements within the road user's line of sight [

5]. This process, a complex and elusive concept, not only describes the intrinsic characteristics of the landscape but also reflects the subjective human responses to the landscape experience [

12].

In addition to the visual appeal of highways, roads and corridors serve as prominent visual focal points, being highly visible and frequently used, making them effective in grabbing people's attention and shaping their perspectives [

22]. In this context of high-speed movement, vision predominates the immediate foreground landscape, tending to fade away, while attention is more consistently directed towards distant views [

6]. Notably, on the highway, the driver experiences the perspective through the window quite differently compared to the passenger [

6]. High-speed driving limits the driver's field of vision, causing them to primarily perceive the broader and more straightforward aspects of the highway landscape. In contrast, passengers have the luxury of focusing more on the road, significantly influencing their perceptions and preferences. Besides, highway users who traveled infrequently (once or twice a month or less) are generally more satisfied with the types and arrangement of vegetation along the roadside compared to those who traveled daily or weekly [

2]. This may be seen in the fact that less frequent travelers are more content with the roadside vegetation, possibly because previous experiences influenced their perceptions of the route less. Therefore, highway landscapes, being linear, impose limitations on road users in terms of visual angle, distance, and landscape identification in their attempts to appreciate them (Wang et al., 2013). This type of linear character emphasizes the importance of the arrangement of elements that make up the landscape and its visual sequence [

12].

3.2. User’s Preference for Highway Landscape

Generally, most studies divide road landscapes into natural and cultural categories [

4]. For highways or general road landscapes, users prefer natural landscapes more than cultural or man-made landscapes [

2,

5,

13,

18,

22,

24]. In natural landscapes on highways, mountains, forests, and green fields play an active role in preference [

5]. Specifically speaking, the roadside vegetation in the highway's natural landscape is the most crucial landscape element among users and contributes to the scenic beauty of the highway [

2]. The users prefer diverse vegetation types rather than uniform plant species combinations [

25]. The preferred combination of vegetation types consists of trees in the background, followed by shrubs in the middle, and grass and flowering plants in the foreground [

2,

25]. However, the roadside vegetation has negative responses, which may be due to the narrow visual space created by dense trees and shrubs, resulting in poor or limited sight lines [

26]. Besides, lack of maintenance and management of vegetation can also create a negative visual experience for users [

24]. It is important to note that excessive and dense tree planting along roadways does not necessarily enhance the visual quality for the general public. Therefore, proper ecological management of vegetation on both sides of the road is critical, enhancing the visual quality of natural heritage [

6].

Cultural aspects, encompassing land use and historical structures, and transitional connections involving environmental changes in elevation all shape the viewer's experience [

14]. However, cultural landscapes generally have a more pronounced influence on highway scenery, not only by obstructing vistas but also by reducing visual quality [

22]. Certain areas of the environment are labeled as 'confining' and 'hazardous,' mainly due to obstructed views caused by buildings [

18]. This has been attributed to the constant alteration of the landscape’s innate nature of the scenery by human activities [

11]. It is worth noting that in cultural landscapes in road environments, historical landscapes are visually preferred over modern ones [

2], which may be due to unique landscape elements. In summary, cultural landscapes, such as cultural landmarks, buildings, and public facilities (street lighting and billboards), are less significant to users' overall aesthetic appeal [

2].

The comprehensive landscape environment of a highway necessitates a harmonious integration of both nature and culture. Planning that solely prioritizes the preservation of the natural landscape and overlooks cultural elements is impractical. Cultural landscapes carry their significance. At the same time, an overabundance of repetitive natural landscapes may lead to aesthetic fatigue among users. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt a balanced and well-considered approach that takes into account both the cultural and natural aspects when planning highways. In short, road landscapes are public spaces that require considering more user perspectives during development or renovation planning. It is crucial to thoroughly understand road users' assessments of the visual preference of road landscapes to inform future road landscape planning, especially in scenic road planning [

26].

3.3. Assessment Approaches of Highway Landscape Visual Preference

By definition from the European Landscape Convention, "landscapes are areas perceived by people, and landscape characteristics are the result of the action and interaction of natural and human factors". This means that people's preferences and perceptions of a certain landscape are based on their comprehension of the landscape and the extent of complexity and interaction it provides [

27]. Through a systematic review of the literature, three main approaches have emerged in exploring methods to assess visual preferences for highways: the public perception approach, the expert approach, and a mixture of the two approaches.

The public perception approach is a subjective way of assessing highway landscape preference by grading and ranking it based on people's perceptions [

3,

8,

11,

18]. This approach treats the highway landscape's preference as a personal value and employs in-person interviews or visual representations, including photo-based surveys [

2,

5]. Therefore, this approach comprehensively analyzes the factors influencing people's perceptions of highway environment and relationships [

8]. The point of this approach is to achieve a consensus by considering each person's perception of the highway landscape [

12,

25].

Understanding public preferences for road landscapes not only enables the consideration of public interest and opinion in planning and design but also aids in evaluating public policy and enhancing better design and planning by decision-makers and designers [

24,

28]. However, there are also some disadvantages to this approach. For example, participants might not understand the questions correctly and give unplanned responses [

29]. The analysis and interpretation of data from surveys could be restricted due to variances in reactions or lack of responses. While survey methods offer valuable insights into individual perspectives, there is a risk that a researcher's intentions might be inadvertently communicated or misinterpreted during the survey process. Besides, photographs in the survey are a very effective and concise way of visually assessing highway landscapes. Still, a limitation of photographs is their inability to convey the potential diversity of the landscape fully [

4]. Sometimes, the image quality in photographs is difficult to ensure, impacting visual appreciation and assessment [

6].

On the other hand, the expert approach employs a method for the properties of the highway visual landscape, which is viewed as a fundamental characteristic of the highway landscape [

14,

20]. This approach is essentially a systematic evaluation of the physical attributes of the highway landscape and the relationships between these attributes, following established norms and standards [

30]. In this approach, it is essential to identify key indicators of visual highway preference that can be assessed quantitatively in terms of their physical or aesthetic components or other relevant factors [

11]. For example, the study of environmental quality and landscape preferences uses indicator parameters related to highway landscape scenes with typical elements [

4]. However, this approach is flawed because it relies solely on expert knowledge and is based on underdeveloped criteria and invalid assessment parameters [

7,

19,

31]. Furthermore, scholars lack agreement regarding the effects of certain indicators utilized for evaluating the visual preference of the highway landscape. Different experts can give different results for the same highway landscape scenario. Simultaneously, it overlooks the observer's subjective perceptions, personal preferences, and psychological factors, including the possibly hidden characteristics of the landscape [

14]. Therefore, experts' approach can be questioned in terms of accuracy, validity, and reliability.

Researchers have attempted to combine both methods, adapting their integrative approach to the particular context to establish a more definite link between highway landscape features and observers [

26]. To achieve a balanced relationship between indicators of the physical characteristics of the landscape and human subjective perception, some studies have embraced a comprehensive evaluation method in road landscape [

32,

33]. The integrated assessment approach not only attempts to bridge the gap between traditional quantitative assessments of physical features and the inherent subjectivity of human perception but also strives to balance the two. It seeks to comprehensively understand the intricate relationship between physical environmental features and how individuals perceive and interact with their surroundings. Therefore, this research approach helps integrate and shape a nuanced understanding of road landscape preference.

3.4. Assessment Variables of Highway Landscape Preference

Landscapes are a response to the general visual aspects of a place, involving the process of recognizing and experiencing specific elements and features within a particular framework [

12]. The visual assessment of landscapes extends beyond assigning a numerical value to the visual quality of a setting, incorporating a range of visual concepts that articulate various aspects of the landscape [

30]. When evaluating the visual preference of road environments, it is essential to consider multiple physical properties as variables. These may include, but are not limited to, flora, vistas, geographical features, land use, seasons, maintenance, and so on [

13].

The physical attributes of highway landscapes are a characteristic that mainly evokes individuals' visual and psychological evaluation of highway landscapes [

4]. Moreover, these attributes play a crucial role in shaping opinions regarding the preference for the highway landscape [

12]. For example, Clay and Smidt [

12] have identified four descriptive metrics (naturalness, vividness, variety, and unity) commonly employed to evaluate the visual preference of landscapes along U.S. federal and state roads. Blumentrath and Tveit [

19] have recommended a set of 12 visual characters, including imageability, legibility, variety, naturalness, and so on, to assess the preference of roadway visuals and propose their connection to aesthetic design in roadways, mainly focusing on everyday roads. Ernawati [

3] has tried to evaluate pedestrians' preferences by assessing complexity, coherence, imageability, and visual preferences using a Likert scale. However, Martín et al. [

30] have entailed selecting pertinent indicators in line with Tveit et al.'s [

34] theoretical framework in visual landscape character to depict the landscape features surrounding motorways. While various articles have introduced variables influencing road landscape preferences, the establishment of a unified and comprehensive standard remains unaddressed. Thus, this study needs to identify several variables contributing to developing a cohesive criterion.

In general, naturalness on the road is crucial for human visual preferences [

5,

13,

25]. The abundance of natural elements has a generally positive effect on human preference [

18], specifically the vegetation along the roadside [

2]. Moreover, it is also recognized that incorporating elements of the natural environment into a project does not necessarily diminish its visual preference [

14]. However, in many cases, transportation projects prioritize functionality and transport requirements without adequately considering environmental integration during the initial design process [

14]. This oversight can result in the creation of excessive and nonsensical man-made landscapes, ultimately leading to visual obstruction and reduced preference for visual appeal. It is evident that naturalness plays an important role in highway landscapes.

However, the mere presence of natural elements on the highway does not always guarantee a positive effect on preferences. The narrow visual space created by too much road vegetation is usually less preferred by people [

24]. The degree of enclosure, which influences the field of view, negatively correlates with the general preference; higher levels of enclosure reduce aesthetic attraction [

4]. Therefore, the level of openness is closely linked to landscape preferences [

2]. Moreover, when there is an expansive field of vision, diverse elements are perceived as more enjoyable than crowded social spaces [

18]. Landscape diversity is a favorable visual attribute that enhances road scenery for drivers [

26]. Coherence and legibility are related to diversity. Coherence is the harmonious and unified combination of diverse elements to create a cohesive landscape vision on the road [

19]. Legibility refers to the degree to which road users can understand the road, including the diversity and coherence of road landscape elements [

19]. Good roadway guidance and simple, easy-to-understand landscaping contribute to legibility [

26]. Imageability is related to the interpretation of the entire landscape scene, which contributes to its memorability and recognizability [

19]. Ernawati [

3] has mentioned that when it comes to streetscapes, people's preferences are consistently influenced by coherence and imageability. Therefore, the assessment of landscape preferences on the highway is mainly based on six variables: naturalness, openness, diversity, coherence, legibility, and imageability.

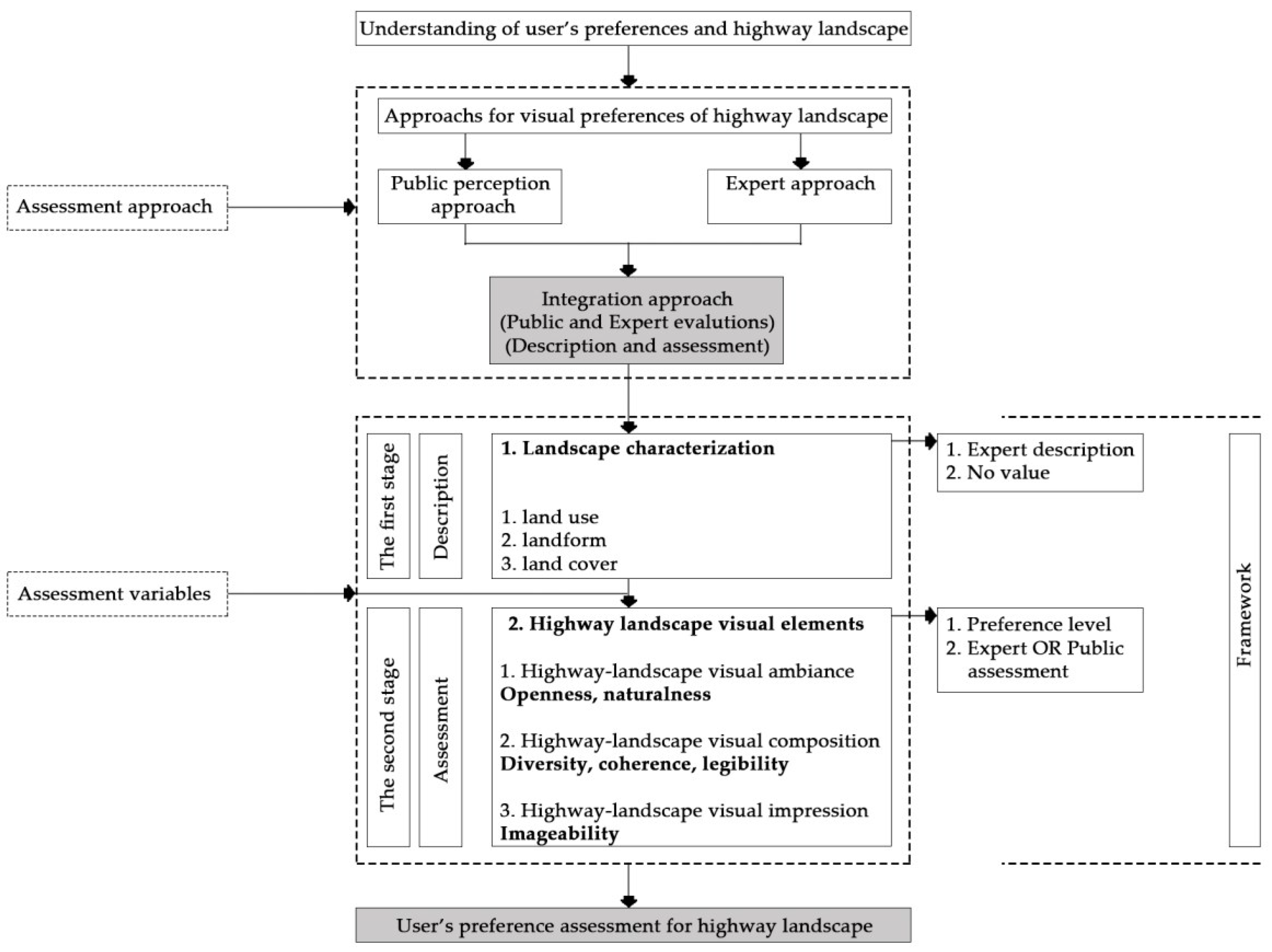

3.5. Highway Landscape Visual Preference Framework

Landscape assessment involves describing and assessing the character of a landscape, followed by planning decisions that highlight its uniqueness and emphasize the character of an area, particularly in terms of protecting the existing natural environment [

13]. This assessment process can, therefore, be divided into two stages. The initial stage, called landscape characterization, is the way of defining, classifying, and mapping out the distinctive landscape character of a landscape area, describing its character and how one place differs from another. To complete landscape characterization, essential data are reviewed, and each type of landscape is classified and labeled [

5,

8]. However, there has not been a single landscape characterization approach suitable for all purposes [

8,

22]. These approaches emphasize various aspects of landscape characterization and time and space descriptions according to their needs. It is crucial to note that characterization is primarily conveyed through a written description, offering valuable insights for decision-making by experts [

24]. This stage is a procedure with little or no value until the second stage, when the landscape characterization is assessed and considered valuable. Hence, this systematic study identified three fundamental physical characteristics—land use, landform, and land cover—as crucial factors in the classification of highway landscape characterization.

Next, the second stage is an assessment of these place landscapes’ character or elements to integrate them into the appropriate management, planning, and conservation choices. At this point, the assessment variables summarized in the previous section can serve as a criterion for evaluating the highway preference level. These variables are organized into three main criteria: highway-landscape visual ambiance (openness, naturalness), highway-landscape visual composition (diversity, coherence, legibility), and highway-landscape visual impression (imageability). Thus, we have developed a framework for preferences regarding highway landscapes (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This study began by establishing a fundamental conceptual understanding of highway landscapes and user preferences. Subsequently, we analyzed and interpreted the research methodology of the selected literature on preferences, including the variables applied in the methodology or findings, to develop a model for assessing highway landscape preferences. In the early days, due to a lack of knowledge, the potential significance of highways in appreciating the environment was overlooked [

6]. Until the mid-20th century in the U.S., the growing interest in the visual quality of highway landscapes began primarily [

12]. During this period, many tourist attractions in the U.S. were closely associated with automobile travel, making the highway environment pivotal to drivers and passengers. As leisure activities on the road increased, evaluation of the quality of the highway environment between destinations became increasingly important. It was during this era that the visual assessment of highway landscapes began to be recognized. However, recent research over the past decade has still revealed a lack of rigorous and consistent criteria for assessing highway landscape preferences. Most studies have relied on consensus decisions by respondents to determine preferences, or expert judgments based on other criteria, or both together. Despite the crucial position of roads in landscapes, there is limited theoretical discussion regarding road aesthetics, leading to a range of imprecise terminologies [

19]. There is always uncertainty and no definitive, unified assessment criteria for highway preference studies. Therefore, this study proposes a uniform and well-established criterion model for comprehensively assessing highway landscape preferences.

Road landscapes, encountered daily by individuals, play a crucial role in introducing individuals to new regions, encouraging exploration of the surrounding environment, and, to some extent, shaping their perception [

26]. The impact of highway landscapes is not only limited to the human eye but also reaches into the realm of the human psyche. When driving on a highway, the road user observes the spatial arrangement of the surrounding landscape, influencing their psychological reactions such as feelings of security, tension, and panic [

8,

23]. These sensations vividly demonstrate the impact of the highway environment on human emotions, transforming the highway into a dynamic space that responds to both visual and emotional stimuli. Therefore, a genuine highway goes beyond just enhancing the natural, built, and social surroundings; it also fulfills the requirements for transportation accessibility and emotional well-being. Roads impact not only the environmental resources of a region but also shape a distinct way of perceiving the environment, serving as resources that connect individuals with the landscape, functioning not only as transport routes [

30].

The natural elements have a dominant influence within a highway landscape, exceeding the prevalence of cultural aspects. Roadside greenery not only enhances the visual appeal of roads but also plays a role in preventing erosion and protecting against damage [

32]. Fathi and Masnavi [

2] have also explored the significance of the aesthetic appeal and scenic quality of existing roadside vegetation along highways, emphasizing the need to consider the importance of incorporating driver preferences when developing management strategies for enhancing the scenic beauty of roadside vegetation. A greater emphasis on natural surroundings inside the highway environment - together with trees, mountains, and water features - tends to beautify the general attraction [

4]. However, an overabundance of those elements can overwhelm individuals cognitively. Therefore, it is important to maintain a balance between enhancing the beauty of natural elements and avoiding too much impact on cognition. This ensures that the road provides a harmonious environment for users to have a comfortable and safe visual driving experience without inducing visual or cognitive fatigue.

Moreover, the presence of man-made structures within road environments consistently appears to have a detrimental effect on road users' overall appreciation of the landscape. Historically, human interventions in landscapes have regularly been driven by economic needs, and highways represent a significant intervention in the landscapes [

11]. Highways often create man-made boundaries because of inadequate control by route operators, neglecting nature's landscape. Highway infrastructure has also contributed to anthropogenic changes in the surrounding environment, resulting in land use and cover alterations and the loss of greenery [

14]. Therefore, highway authorities face the task of developing a highway project harmonizing with its environment while ensuring visual, cultural, and environmental compatibility [

2].

A highway landscape visual preference assessment comprises a systematic and scientific inquiry into the current state of the landscape environment. The evaluation considers formal aesthetics and road users' values, thus offering a comprehensive overview of the landscape environment along the roadside. Assessing landscape vision is inherently complicated due to the task of capturing the nuanced human perceptual experience, specifically while dealing with transient landscape elements [

12]. Human visual cognitive behavior involves more than just gathering external information; it is a complex mental process combining judgments and noticing visible specifics. Scientific evidence emphasizes the significance of the roadside landscape and its visual attributes for road users' perceptions [

22]. A reliable highway environmental assessment system offers a comprehensive assessment and understanding of the environmental conditions in and around the highway [

20]. Therefore, this study attempts to propose a comprehensive framework for characterizing and evaluating highway landscape characters and their preferences.

5. Limitation and Future Studies

This study systematically reviews users' preferences toward highway landscape character. However, there are still some flaws in this study. Firstly, the number of keywords was limited. In future research, keywords such as “preference criteria,” “preference factors,” or “preference indicators” could be included to enhance the understanding of preference variables and framework. Next, the number of papers selected was limited and even more limited in specifically discussing highway landscapes. This narrow focus may have influenced the study's findings. Therefore, future screenings should broaden their literature review to include a wider range of articles that may be relevant or linked to road or highway landscape preferences. Lastly, while the study identified the variables and factors influencing highway landscape preferences, it did not provide an in-depth discussion, assessment, and validation of each variable. Therefore, it is crucial for future research to explore these variables more deeply, offering adequate theoretical and practical definitions for the preference assessment framework.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed 26 papers tabulated on highway landscape preferences and found a complex relationship between users and highway landscapes and trends in users' preferences for highway landscapes. Highways integrate natural and man-made landscapes and provide a way for users to understand the landscape. At the same time, users' appreciation and understanding of highway landscapes are limited by some intrinsic and extrinsic conditions. Generally, users prefer natural landscapes over cultural landscapes, highlighting the importance of roadside vegetation. Although cultural landscapes generally have a negative impact on user preferences, they are an integral part of the highway landscape. Therefore, it is essential to take a balanced approach that integrates both natural and cultural elements in highway planning. This approach ensures aesthetics and prevents visual fatigue for users while emphasizing the importance of inclusive planning, which considers user preferences for the future highway landscape.

The article analyzed the research methods used to assess highway landscape preferences, identifying the factors and variables involved. It presents a discussion and summary of the variables used to assess preferences and links them to a comprehensive assessment framework based on a combination of expert and public perceptions. However, the framework requires validation and evaluation in the next step. Overall, the results of this study bridge the uncertainty of highway landscape preference assessment and establish a basic standard for professionals to refer to.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G., S.A.B. and S.M.; methodology, H.G. and M.J.MY.; data analysis, H.G., S.A.B. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, M.J.MY., S.M. and B.X.; visualization, S.M. and R.M.; supervision, M.J.MY. and B.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Visual Resource Stewardship Conference 2023.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary table of all 26 documents.

Table A1.

Summary table of all 26 documents.

| No. |

Document |

First Autor |

Year |

Journal |

Method |

Research Scope |

| 1 |

Research |

Carolina G. Ojeda Leal

Pontificia |

2023 |

Landscape Online |

Qualitative

(A comparison method) |

Highway landscape |

| 2 |

Research |

Hangyu Gao |

2023 |

Land |

Quantitative (Survey) |

Rural road landscape |

| 3 |

Research |

Xiaochun Qin |

2023 |

Environmental Impact Assessment Review |

Quantitative

(Real-time evaluation and data processing system) |

Highway

landscape |

| 4 |

Research |

Shengneng Hu |

2023 |

Sustainability |

Qualitative

(Set-pair analysis method) |

Highway landscape |

| 5 |

Research |

Jing Zhao |

2022 |

Sustainability |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Model assessment) |

Street landscape |

| 6 |

Research |

Han, J. |

2022 |

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences |

Quantitative (Multi-technical method) |

Street landscape |

| 7 |

Research |

Hui He |

2021 |

Frontiers in Psychology |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Greenway landscape |

| 8 |

Conference |

Ernawati, J. |

2021 |

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Urban street landscape |

| 9 |

Conference |

Fu Zheng |

2021 |

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science |

Qualitative

(Descriptive method) |

Expressway landscape |

| 10 |

Research |

Paul Sneha |

2020 |

Journal of Engineering Science |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Urban Landscape quality index and analytical hierarchy process, AHP) |

City road landscape |

| 11 |

Research |

Vugule Kristine |

2020 |

Landscape Architecture and Art |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Case study, scenario method, and survey) |

Road landscape |

| 12 |

Conferences |

Zhouyi Huang |

2019 |

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science |

Qualitative

(Descriptive method) |

Highway landscape |

| 13 |

Research |

Eroğlu, Engin |

2018 |

Tarim Bilimleri Dergisi |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Roadside poplar planting |

| 14 |

Research |

Ojeda, Carolina G. |

2018 |

Landscape Online |

Qualitative (Photographic material, field notes, and on-site observations) |

Highway landscape |

| 15 |

Research |

Martín, Belén |

2018 |

Sustainability |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Motorway landscape |

| 16 |

Research |

Liang Cheng |

2017 |

ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information |

Quantitative

(Visual perception indices) |

Street landscape |

| 17 |

Conferences |

Bojing Liao |

2017 |

MATEC Web of Conferences |

Quantitative

(Holistic technique) |

Rural highway landscape |

| 18 |

Research |

Martín, Belén |

2016 |

Journal of Environmental Management |

Quantitative

(Indicators) |

Road landscape |

| 19 |

Review |

Blumentrath, Christina |

2014 |

Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice |

Qualitative

(Review) |

Road landscape |

| 20 |

Research |

Fathi, M. |

2014 |

International Journal of Environmental Research |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Highway landsacpe |

| 21 |

Research |

Dan Wang |

2013 |

Applied Mechanics and Materials |

Qualitative

(Descriptive method) |

Highway landscpe |

| 22 |

Research |

Jaal, Z. |

2013 |

WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Expressway landscape |

| 23 |

Review |

Jaal, Zalina |

2012 |

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences |

Qualitative

(Descriptive method) |

Highway landscape |

| 24 |

Research |

Froment, José |

2006 |

Landscape and Urban Planning |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Highway landscape |

| 25 |

Research |

Clay, Gary R. |

2004 |

Landscape and Urban Planning |

Quantitative

(Survey) |

Highway landscape |

| 26 |

Research |

Akbar, K. F. |

2003 |

Landscape and Urban Planning |

Quantitative

(Simulation and survey) |

Roadside vegetation |

Table A2.

Total number of publications from 21 documents.

Table A2.

Total number of publications from 21 documents.

| Code |

Categories |

Number of Publications |

| A |

Document |

|

| |

Research papers |

20 |

| |

Review papers |

2 |

| |

Conference papers |

4 |

| |

|

26 |

| B |

Year |

|

| |

2023 |

4 |

| |

2022 |

2 |

| |

2021 |

3 |

| |

2020 |

2 |

| |

2019 |

1 |

| |

2018 |

3 |

| |

2017 |

2 |

| |

2016 |

1 |

| |

2014 |

2 |

| |

2013 |

2 |

| |

2012 |

1 |

| |

2006 |

1 |

| |

2004 |

1 |

| |

2003 |

1 |

| |

|

26 |

| C |

Journal |

|

| |

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science |

3 |

| |

Landscape and Urban Planning |

3 |

| |

Sustainability |

3 |

| |

Landscape Online |

2 |

| |

Applied Mechanics and Materials |

1 |

| |

Environmental Impact Assessment Review |

1 |

| |

Frontiers in Psychology |

1 |

| |

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences |

1 |

| |

International Journal of Environmental Research |

1 |

| |

ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information |

1 |

| |

Journal of Environmental Management |

1 |

| |

Journal of Engineering Science |

1 |

| |

Land |

1 |

| |

Landscape Architecture and Art |

1 |

| |

MATEC Web of Conferences |

1 |

| |

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences |

1 |

| |

Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice |

1 |

| |

Tarim Bilimleri Dergisi |

1 |

| |

WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment |

1 |

| |

|

26 |

| D |

Method |

|

| |

Quantitative (Survey) |

10 |

| |

Quantitative (Technical method) |

3 |

| |

Quantitative (Factors) |

2 |

| |

Qualitative

(Descriptive method) |

4 |

| |

Qualitative

(A comparison method) |

1 |

| |

Qualitative

(Set-pair analysis method) |

1 |

| |

Qualitative

(Photographic material, field notes, and on-site observations) |

1 |

| |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Model assessment) |

1 |

| |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Urban landscape quality index and analytical hierarchy process, AHP) |

1 |

| |

Quantitative and Qualitative

(Case study, scenario method, and survey) |

1 |

| |

|

26 |

| E |

Research scope |

|

| |

Highway landscape |

14 |

| |

Road landscape |

7 |

| |

Street landscape |

4 |

| |

Greenway landscape |

1 |

| |

|

26 |

References

- Stamps, A.E. Mystery, complexity, legibility and coherence: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.S.; Masnavi, M.R. Assessing environmental aesthetics of roadside vegetation and scenic beauty of highway landscape: Preferences and perception of motorists. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernawati, J. The role of complexity, coherence, and imageability on visual preference of urban street scenes. IOP. Conf. 2021, 764, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Fang, M.; Yang, D.; Wangari, V.W. Quantitative evaluation of attraction intensity of highway landscape visual elements based on dynamic perception. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaal, Z.; Abdullah, J.; Ismail, H. Malaysian North South Expressway landscape character: analysis of users’ preference of highway landscape elements. WIT. Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 179, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froment, J.; Domon, G. Viewer appreciation of highway landscapes: The contribution of ecologically managed embankments in Quebec, Canada. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2006, 78, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Qin, Z. Research on Evaluation Index System of Mountain Expressway Landscape Coordination. IOP. Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 676, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, B.; Arce, R.M.; Otero, I.D.; Loro, M. Visual Landscape Quality as Viewed from Motorways in Spain. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křováková, K.; Semerádová, S.; Mudrochová, M.; Skaloš, J. Landscape functions and their change – a review on methodological approaches. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 75, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman RT, T. Town ecology: for the land of towns and villages. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 2209–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, C.G. Assessment of Landscape Changes caused by Highway Construction: Case Study of Ruta del Canal Pargua Highway in Chile. Landsc. Online. 2023, 98, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, G.R.; Smidt, R.K. Assessing the validity and reliability of descriptor variables used in scenic highway analysis. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2004, 66, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaal, Z.; Abdullah, J. User’s Preferences of highway Landscapes in Malaysia: A review and analysis of the literature. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 36, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, C.G. Visual scale and Naturalness of Roadside Vegetation Landscape. An exploratory study at Pargua Highway, Puerto Montt – Chile. Landsc. Online. 2018, 58, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, G.; Tasser, E.; Tappeiner, U. Using conjoint analysis to gain deeper insights into aesthetic landscape preferences. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Culture and the perception of the environment. In Bush Base: Forest Farm: Culture, Environment, and Development; Croll, E., Parkin, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1992; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wíldavsky, A. Choosing Preferences by Constructing Institutions: A Cultural Theory of preference formation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1987, 81, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Yu, Y. Greenway Cyclists’ Visual Perception and Landscape Imagery Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumentrath, C.; Tveit, M.S. Visual characteristics of roads: A literature review of people’s perception and Norwegian design practice. Transp. Res. Part. A. Policy. Pract. 2014, 59, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Tong, W.; Mao, K. Study on Highway Landscape Environment assessment and grading Method. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, F.; Xu, R. Research on highway landscape design based on driver’s visual characteristics. IOP. Conf. 2019, 330, 022127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, E.; Acar, C. A visual assessment of roadside poplar plantings in Turkey. Tarim Bilim. Derg. 2018, 24, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Qin, X.; Wang, C. Research for Aesthetic and visual Quality Management in Highway landscape. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 368-370, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Bakar, S.A.; Maulan, S.; Yusof, M.J.M.; Mundher, R.; Zakariya, K. Identifying visual quality of rural road landscape character by using public preference and heatmap analysis in Sabak Bernam, Malaysia. Land, 2023, 12, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, K.F.; Hale, W.H.; Headley, A.D. Assessment of scenic beauty of the roadside vegetation in northern England. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2003, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vugule, K.; Stokmane, I.; Bell, S. Use of mixed methods in road landscape perception studies: an example from Latvia. Landsc. Archit. Art. 2020, 15, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Consensus in factors affecting landscape preference: A case study based on a cross-cultural comparison. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 252, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.; Wang, F. An aesthetic design method of landscape visualization Restoration for a rural highway around the Nanwan Lake: a case study in the Shihe district, Xinyang City, Henan province. MATEC. Web. Conf. 2017, 104, 0–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, S. RESIDENT’S SATISFACTION IN STREET LANDSCAPE USING THE IMMERSIVE VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENT-BASED EYE-TRACKING TECHNIQUE AND DEEP LEARNING MODEL. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLVIII-4/W4-2022 2022, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, B.; Ortega, E.; Otero, I.D.; Arce, R.M. Landscape character assessment with GIS using map-based indicators and photographs in the relationship between landscape and roads. J. Environ. Manage. 2016, 180, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Chu, S.; Zong, W.; Li, S.; Wu, J.; Li, M. Use of tencent street view imagery for visual perception of streets. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Roy, T.K. An assessment of road landscape by analysing people’s perception and expert opinion of Khulna City, Bangladesh. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, Q. Intelligent Assessment for Visual Quality of Streets: Exploration based on Machine Learning and Large-Scale Street View data. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, Å.; Fry, G. Key concepts in a framework for analysing visual landscape character. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).