Submitted:

22 March 2023

Posted:

23 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dimension Extraction

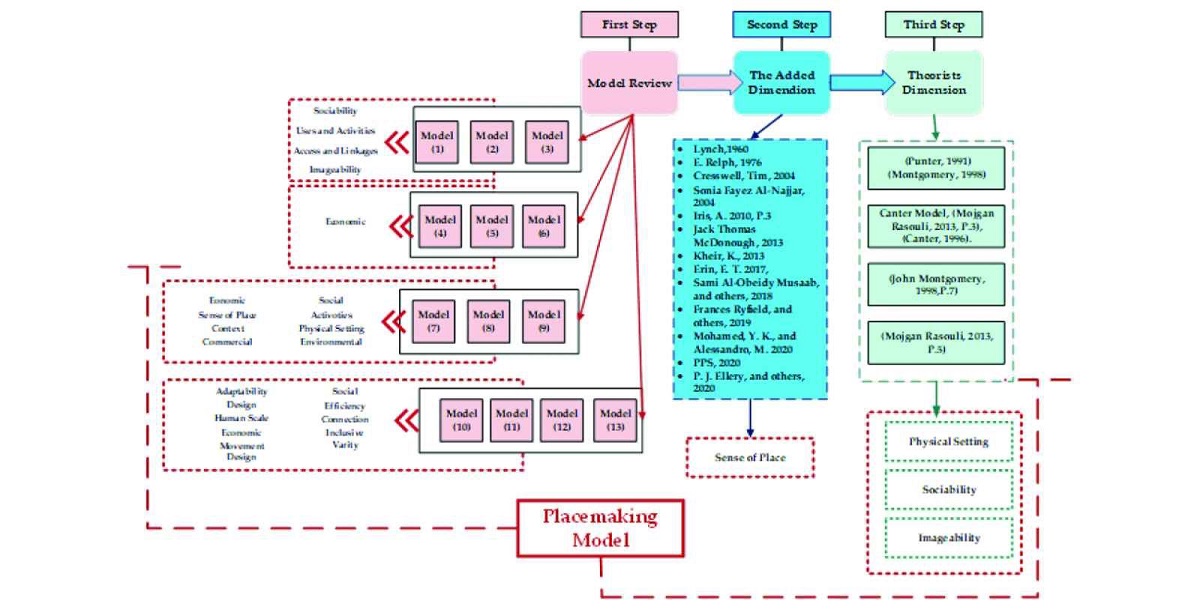

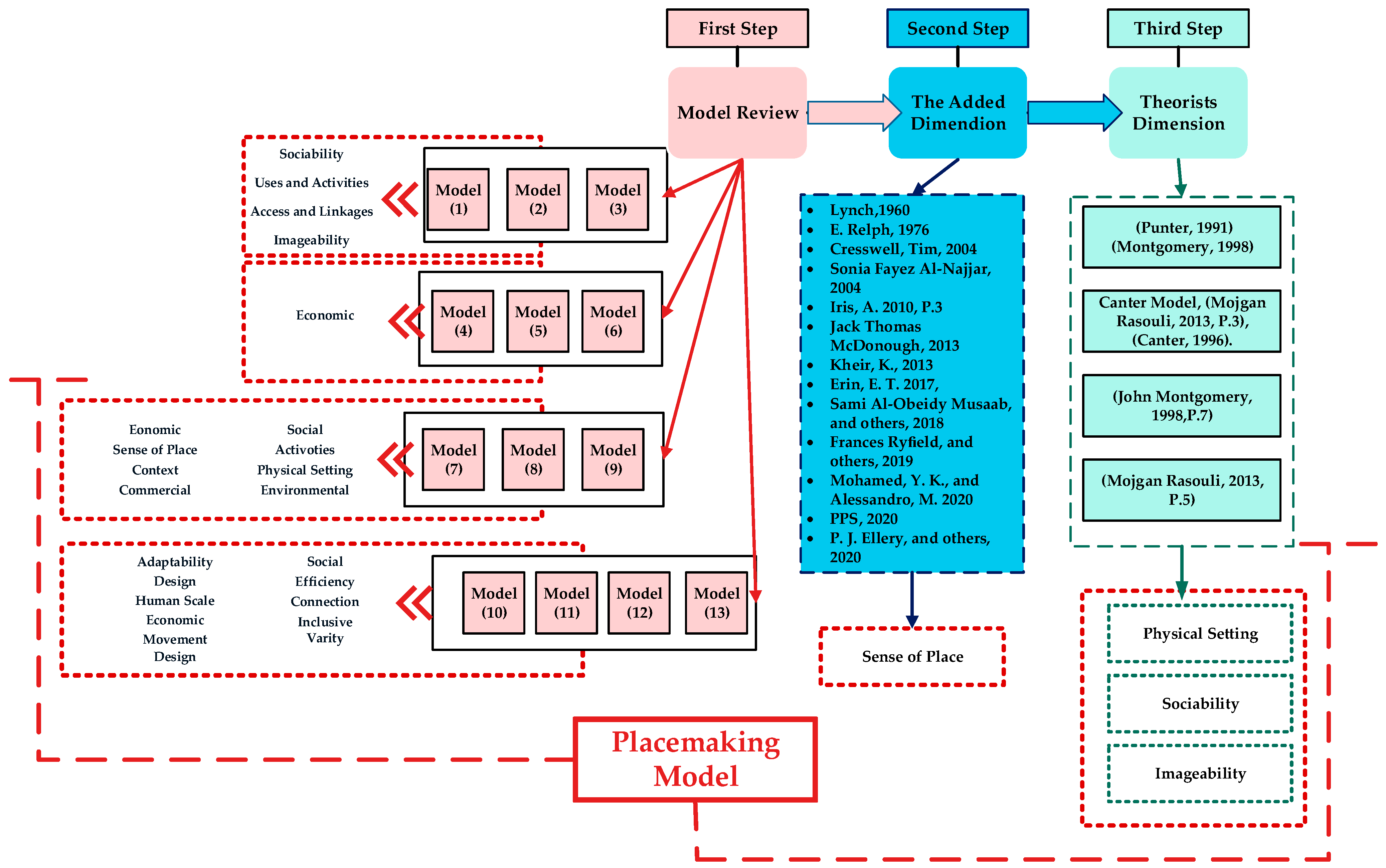

2.1.1. First Step (Models Review)

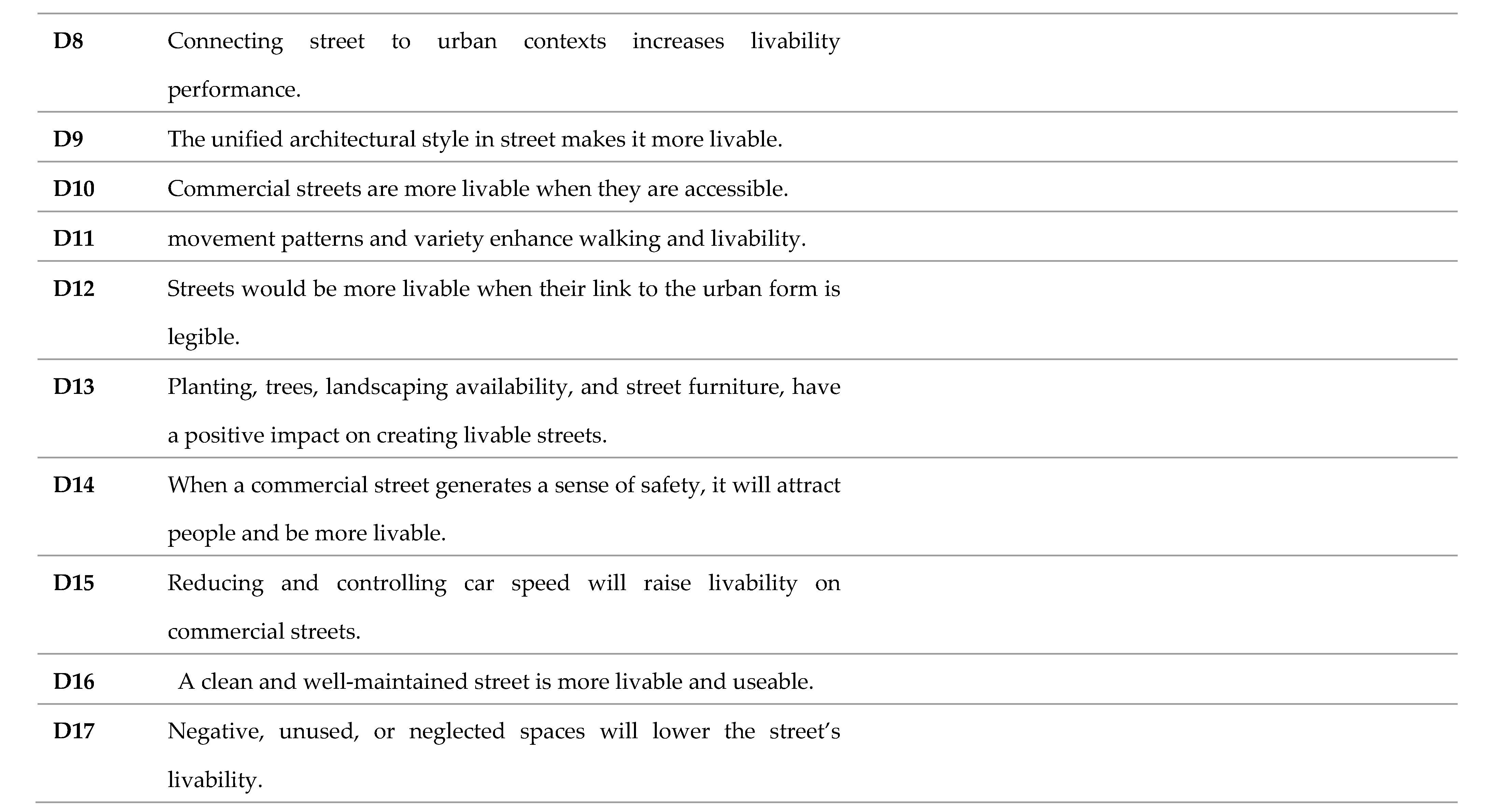

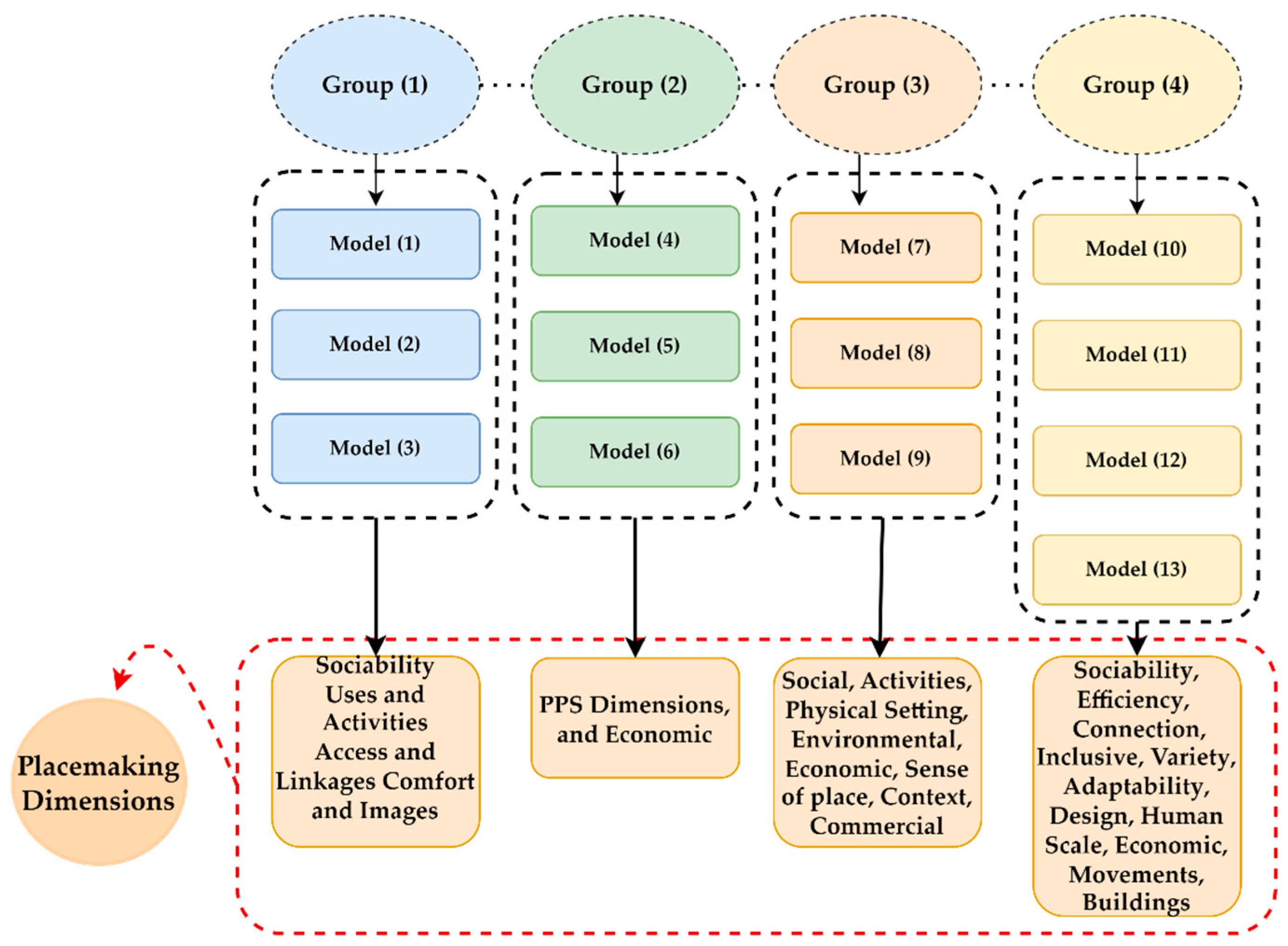

- Thirteen models adopted by researchers, architectural theorists, and urban designers were reviewed to evaluate placemaking within a commercial street. The most frequent dimensions were: Sociability, Accessibility, Uses and Activities, Comfort, and Imageability.

- The dimensions were regrouped into four groups based on the common dimensions among the models. As well as the derivation of the new dimension between them

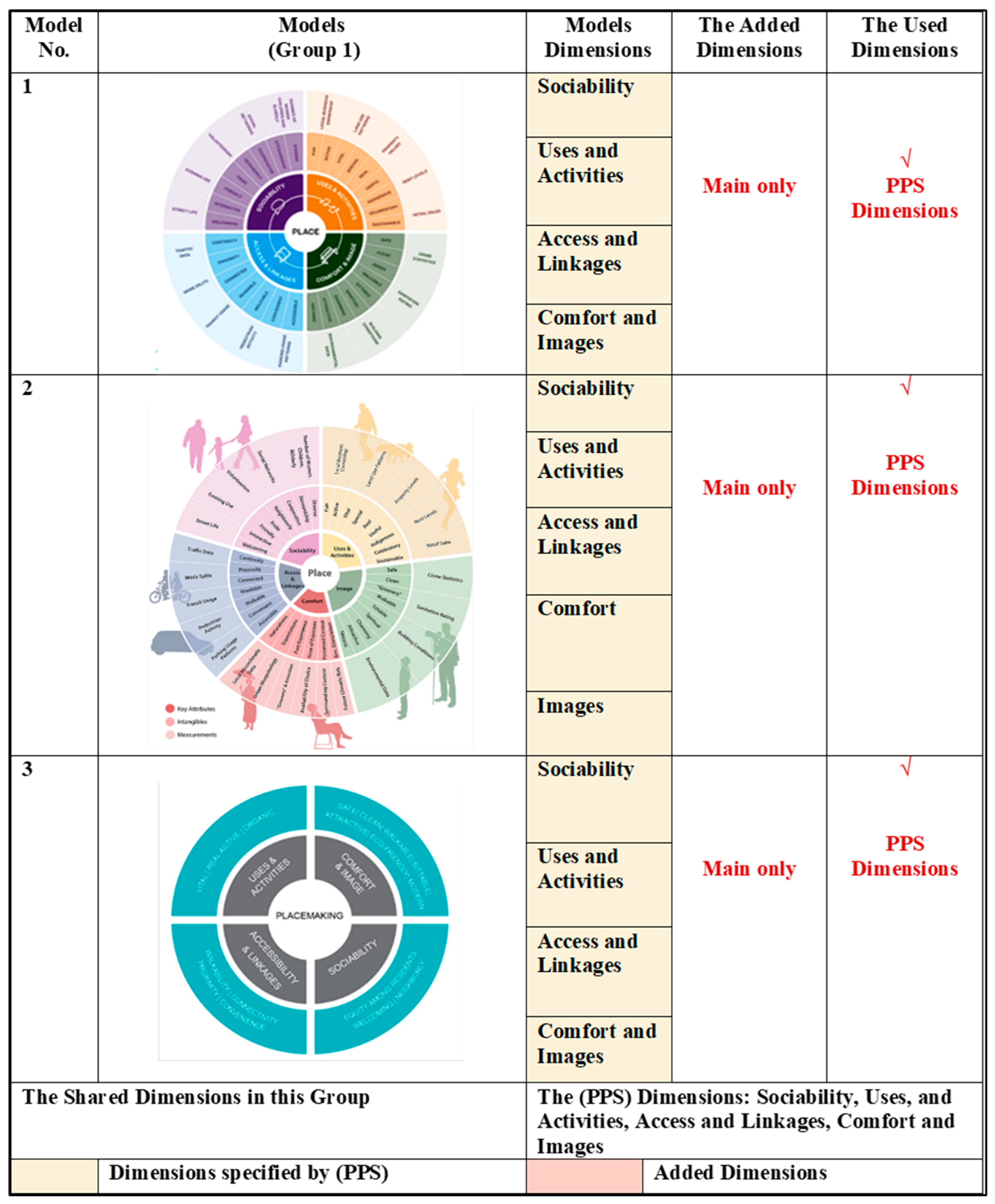

- First group with three models out of thirteen, all four dimensions were adopted for evaluating and redeveloping streets, this group relied on the dimensions of (PPS), which become the basis for their research and practical assessment. Figure 1, Appendix A1. [7], [9], [10]

- The second group with three models shared the same basic dimensions. Other dimensions were added according to the context of the research sample, site analysis, and conservation since the selected site was within a conservation area. Both climatic and economic were added to the considerations of the selected samples, Appendix A2, [11], [12], [13].

- Dimensions such as design, environmental, urban context, historical, spatial, human scale, climatic, and sense of place were mentioned individually and according to the research need and problem in this group. The researchers praised the importance of these dimensions, considered one of the basic pillars of placemaking that was not used previously. Appendix A4. [17], [18], [19], [20]. (The compared dimensions table in Appendix part A).

- By comparing the dimensions of the aforementioned models presented by the researchers, an extrapolation was made to determine the most important and repeated factors to use within the model and the Framework, both (Theoretical and Practical).

- The least frequent dimensions in the previous studies were also included in the theoretical framework. A comprehensive evaluation list for placemaking was extracted, to evaluate livability in the commercial street, Figure 2.

2.1.2. Second Step (The Added Dimension)

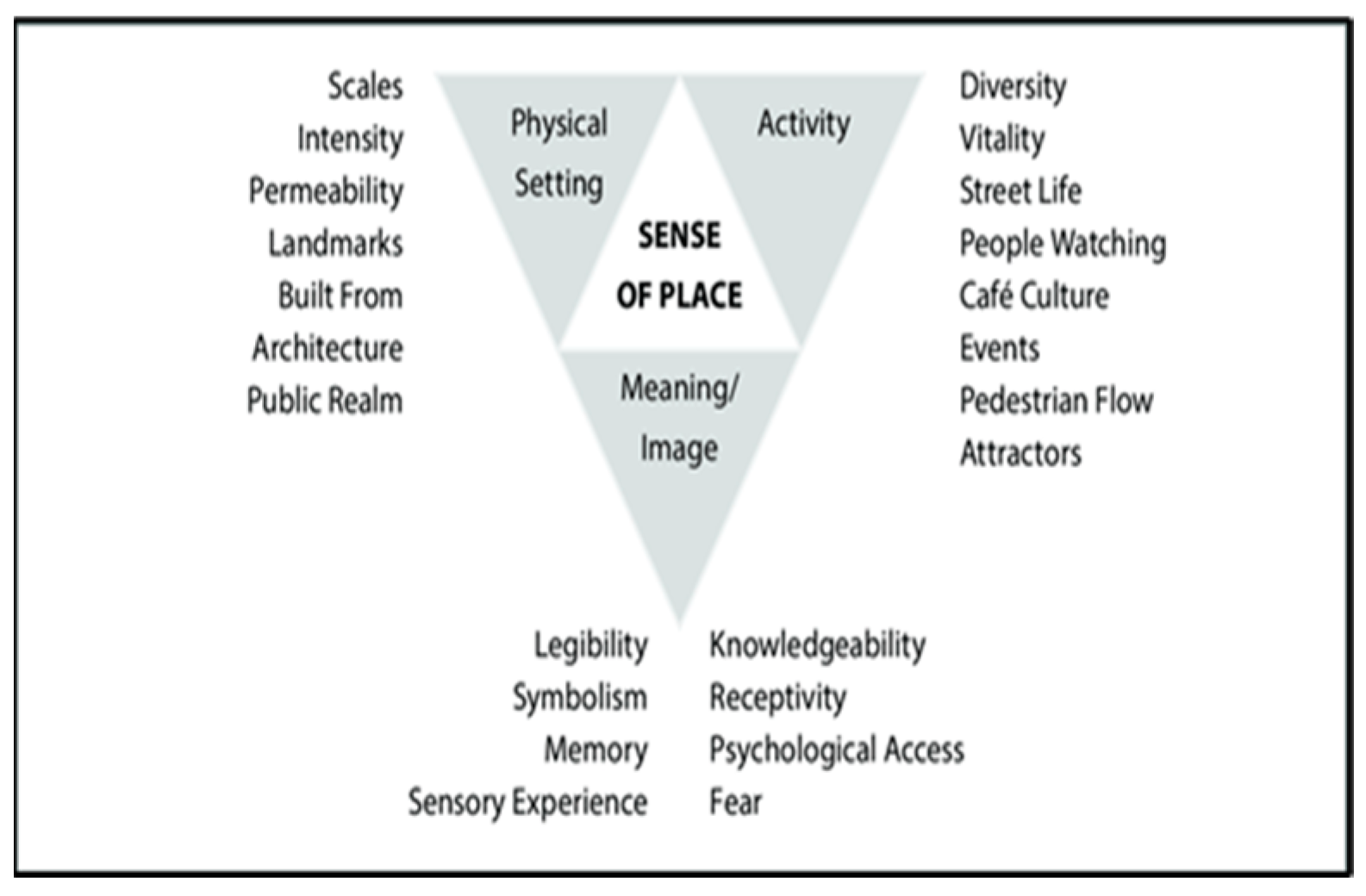

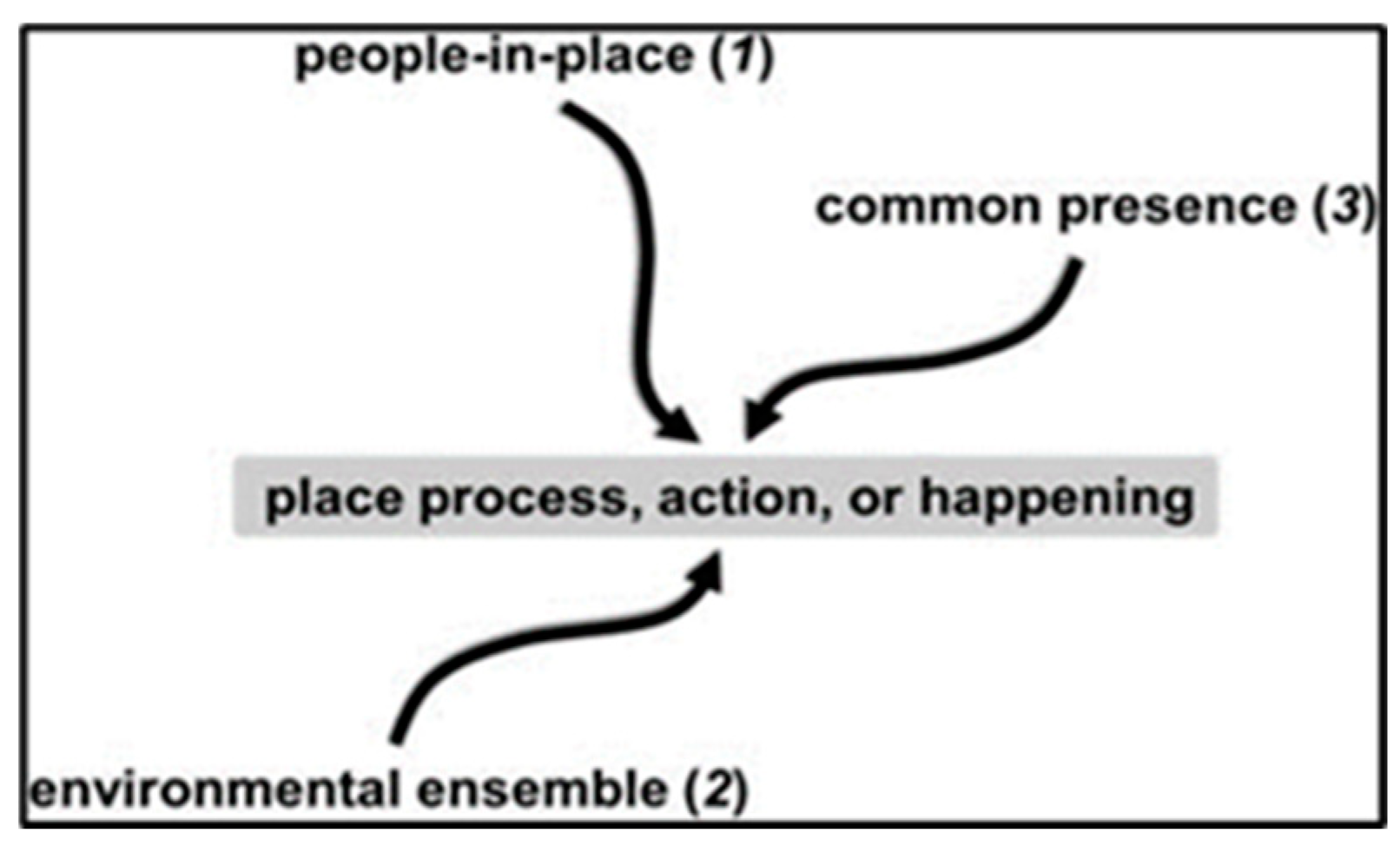

2.1.2.1. Sense of Place

2.1.2.2. Sense of Place and Placemaking

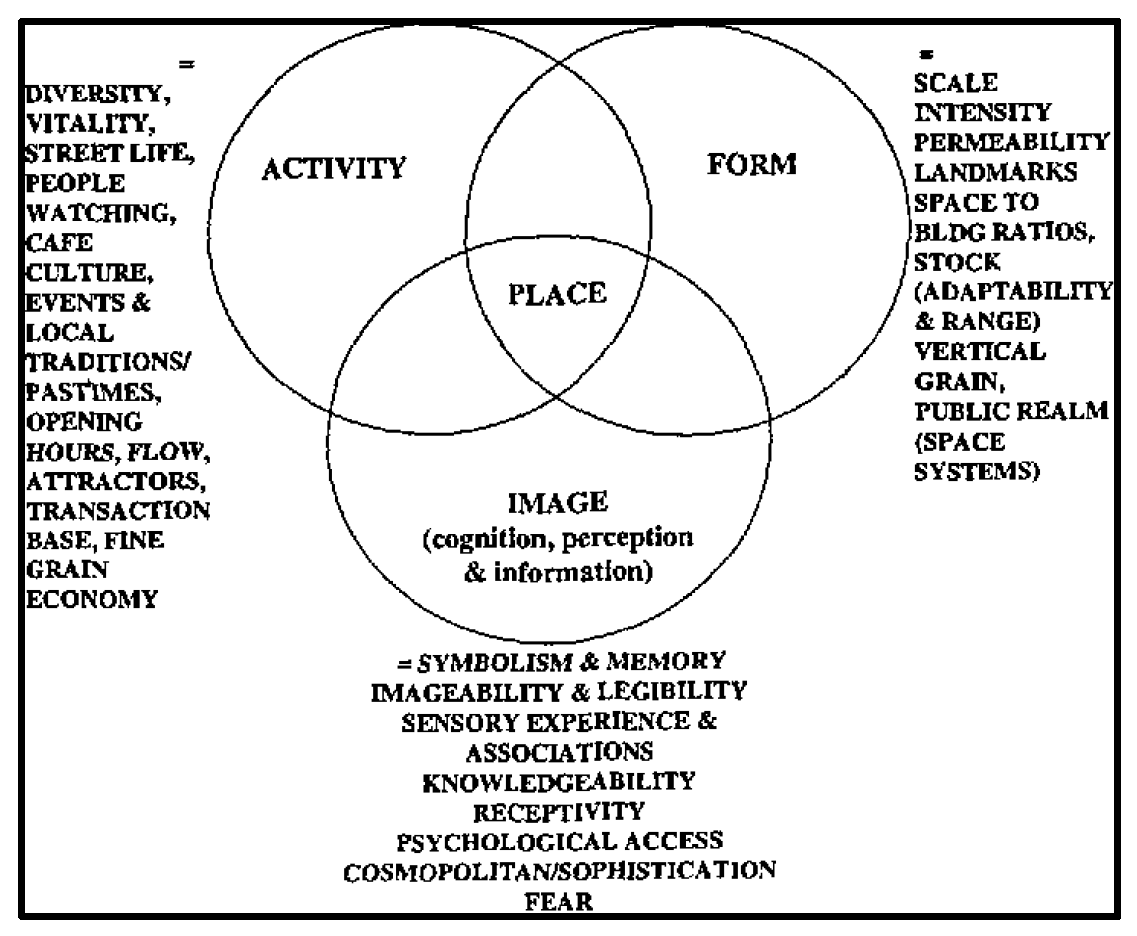

2.1.3. Third Step (Theorists Dimensions)

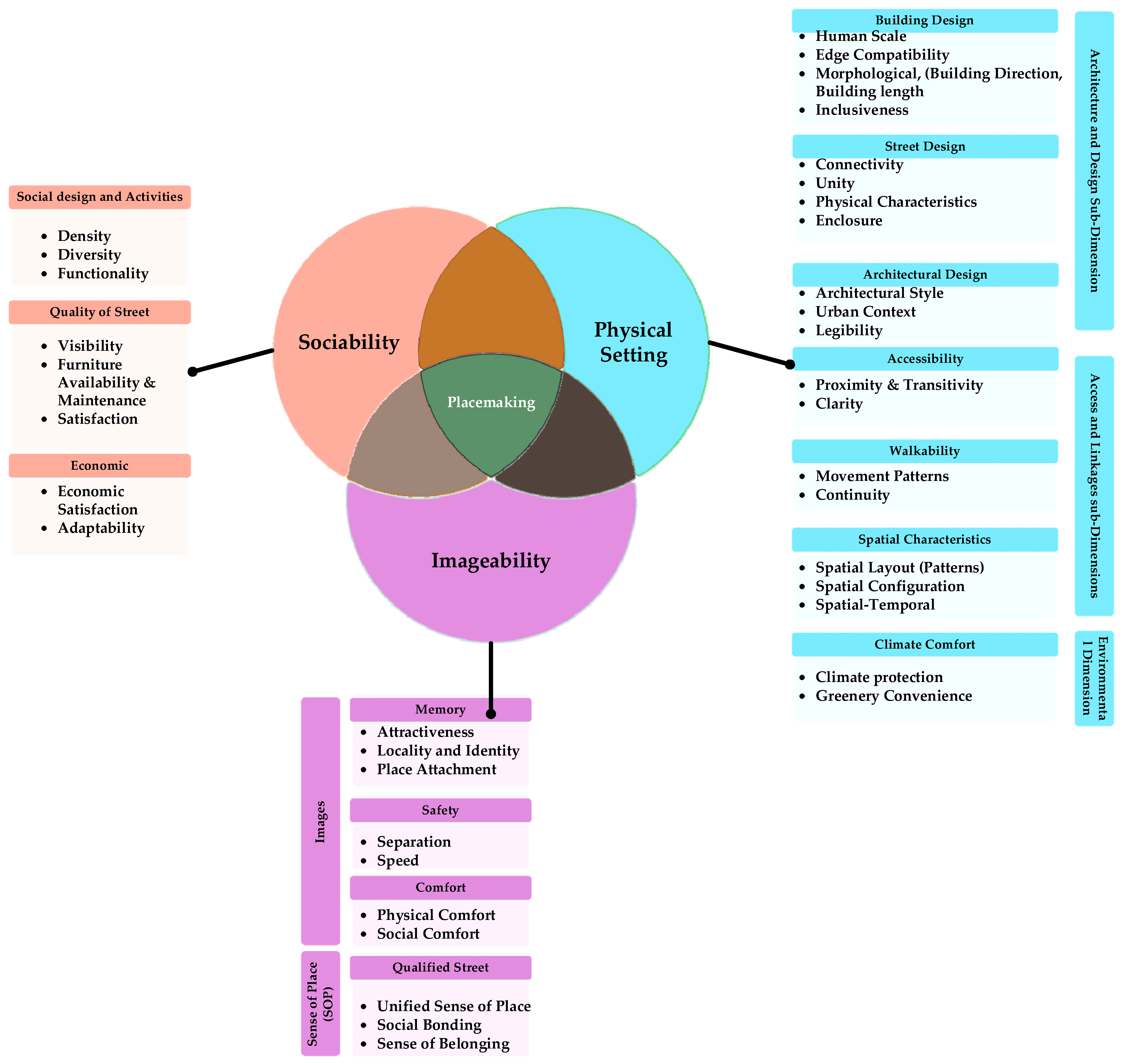

2.2. Placemaking Model

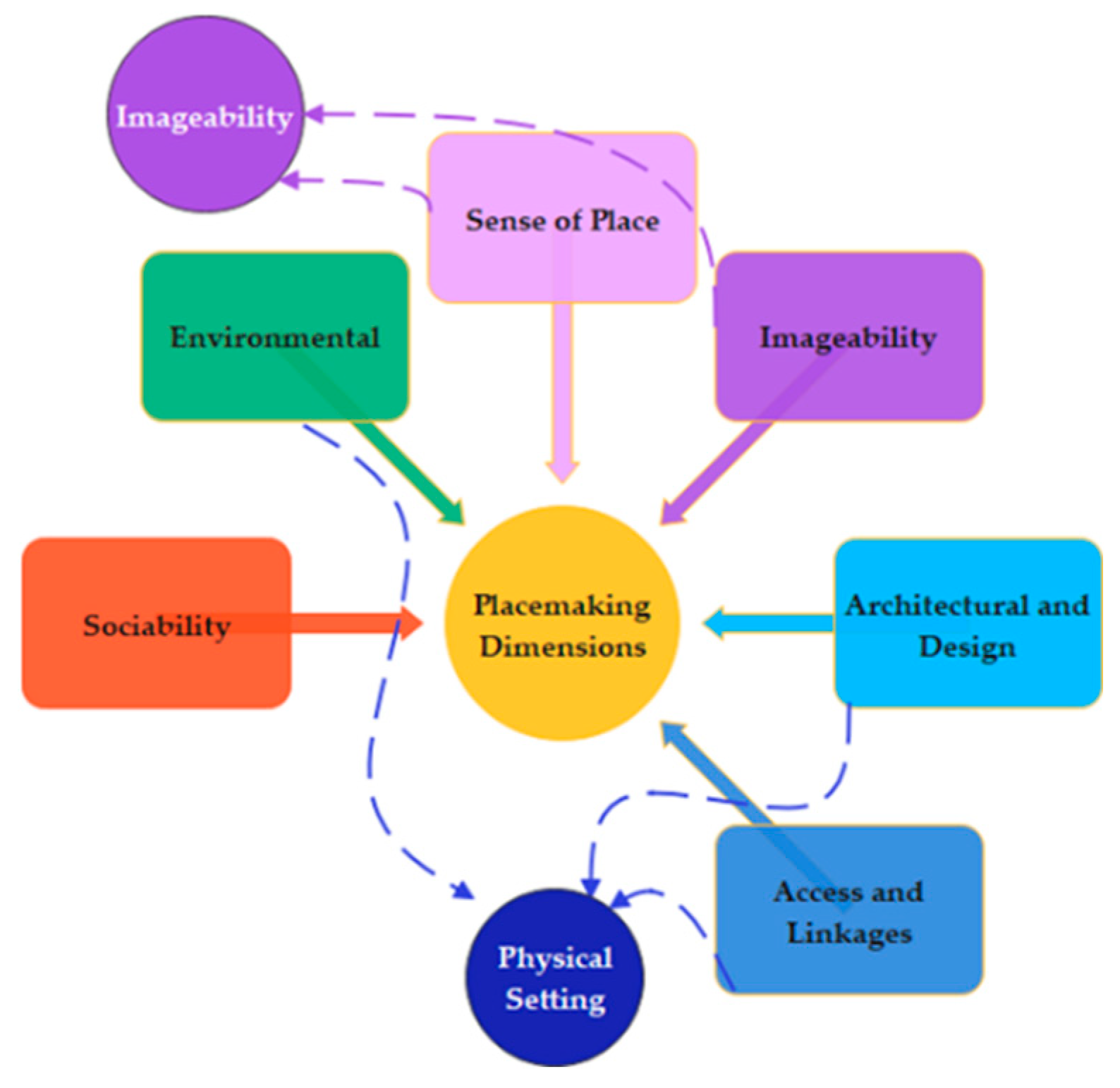

- Dimensions have been compared to identify the more influential ones in place and placemaking.

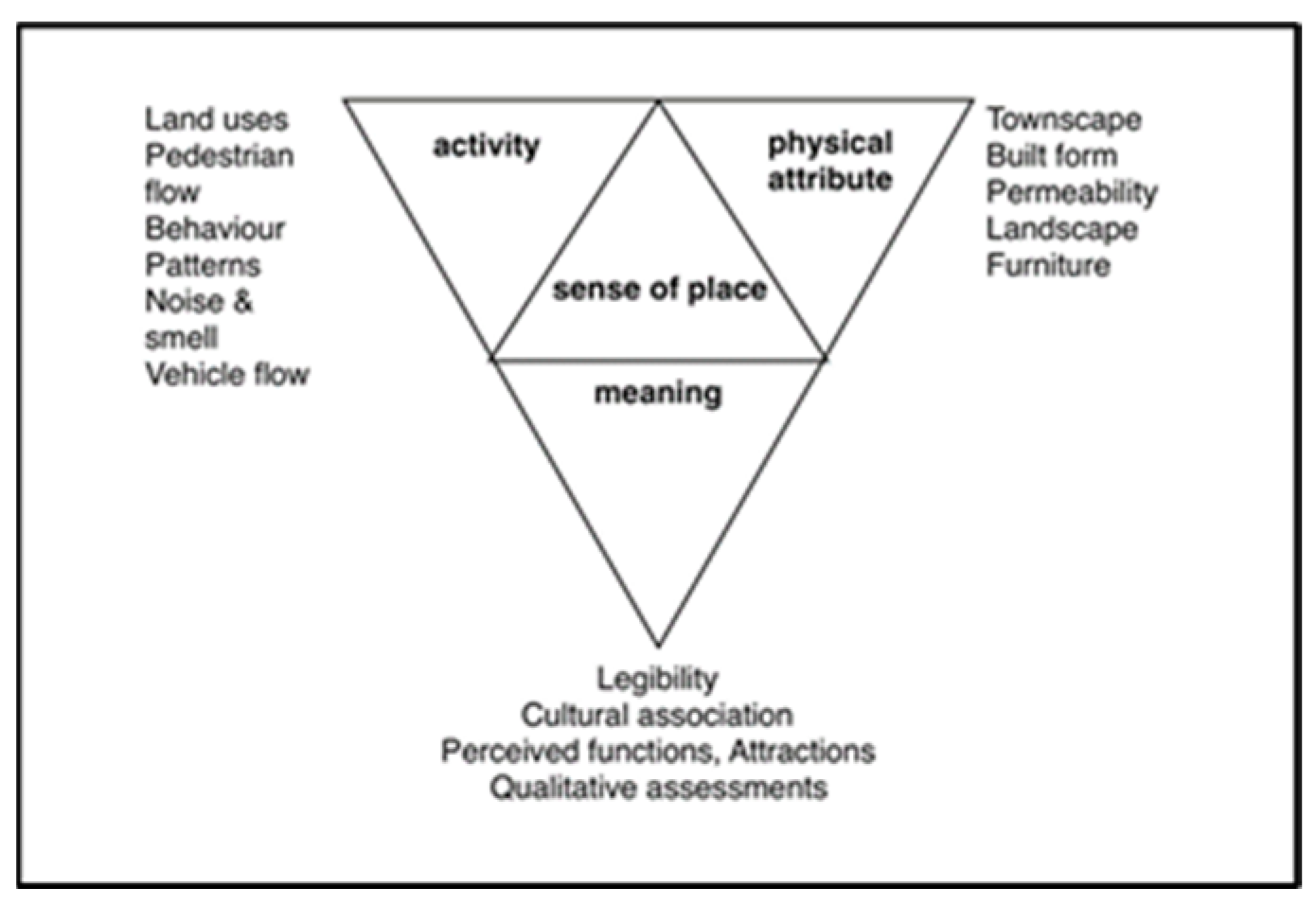

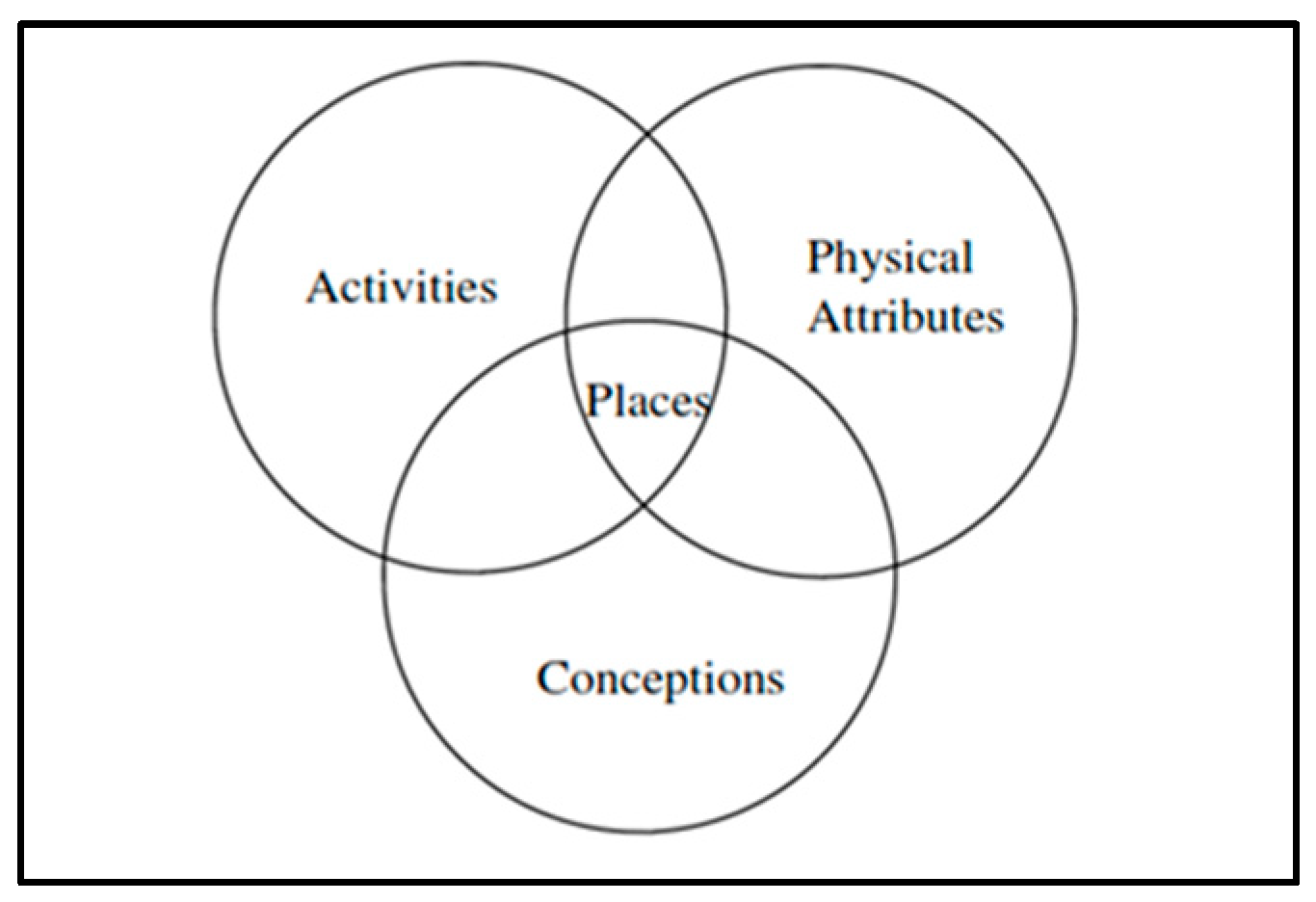

- By reviewing the models and according to previous studies that developed or applied the models, all of them indicated the importance of the four dimensions within the strategies of place; Sociability, Access and linkages, Uses and Activities, and Comfort and Images, [7], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. As for the theorists of the place, Punter, Canter, Montgomery, Mojgan, and Seamon, [36], [38], [39], [40], [41], agreed on the presence of three basic dimensions that have an impact on raising the quality of the place, which are the social aspect, the physical setting, and the meaning or sense of the place, and by comparing the practical and theoretical sides of both models and the theorists, the model was restructured to suit the local commercial street.

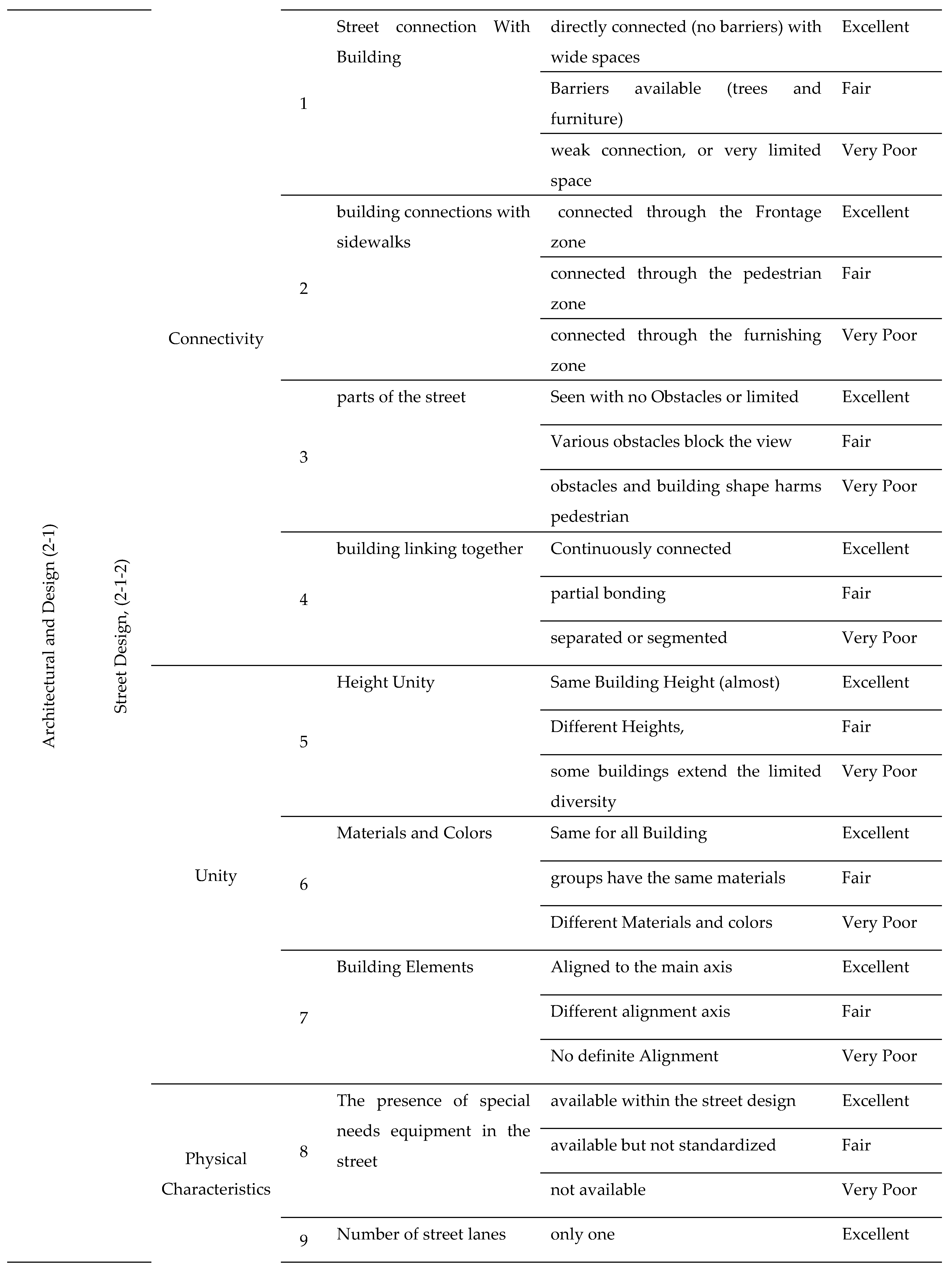

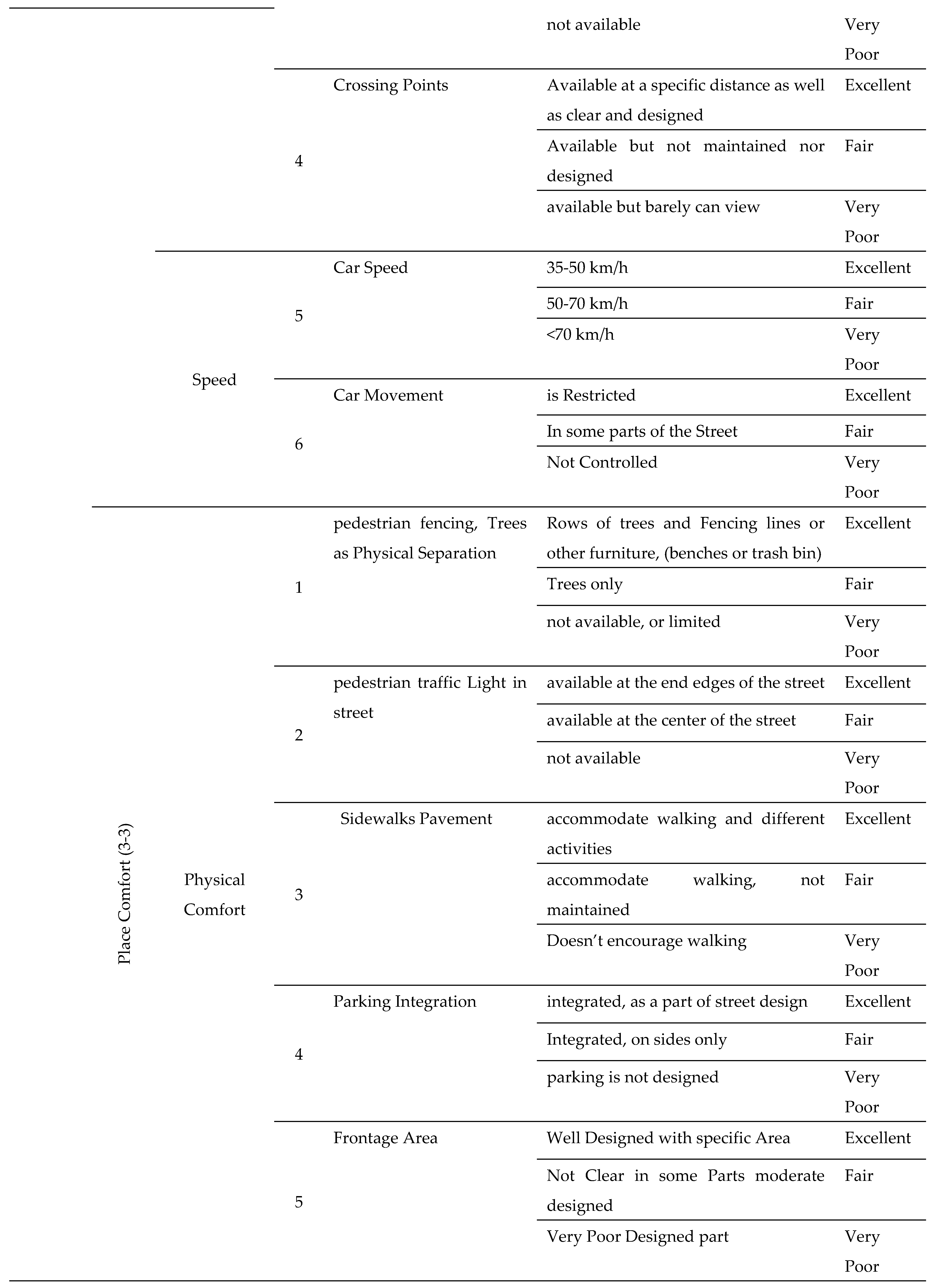

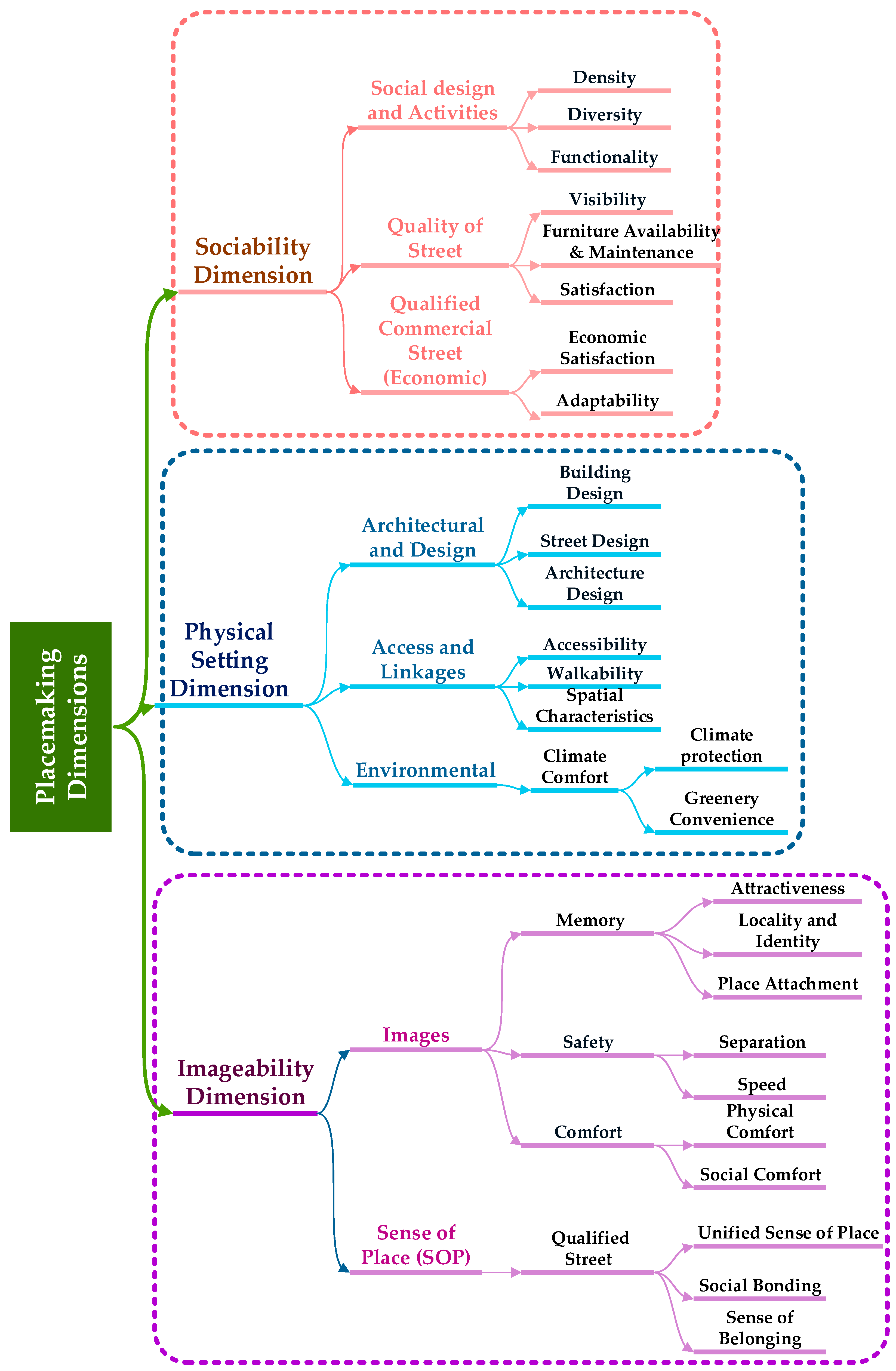

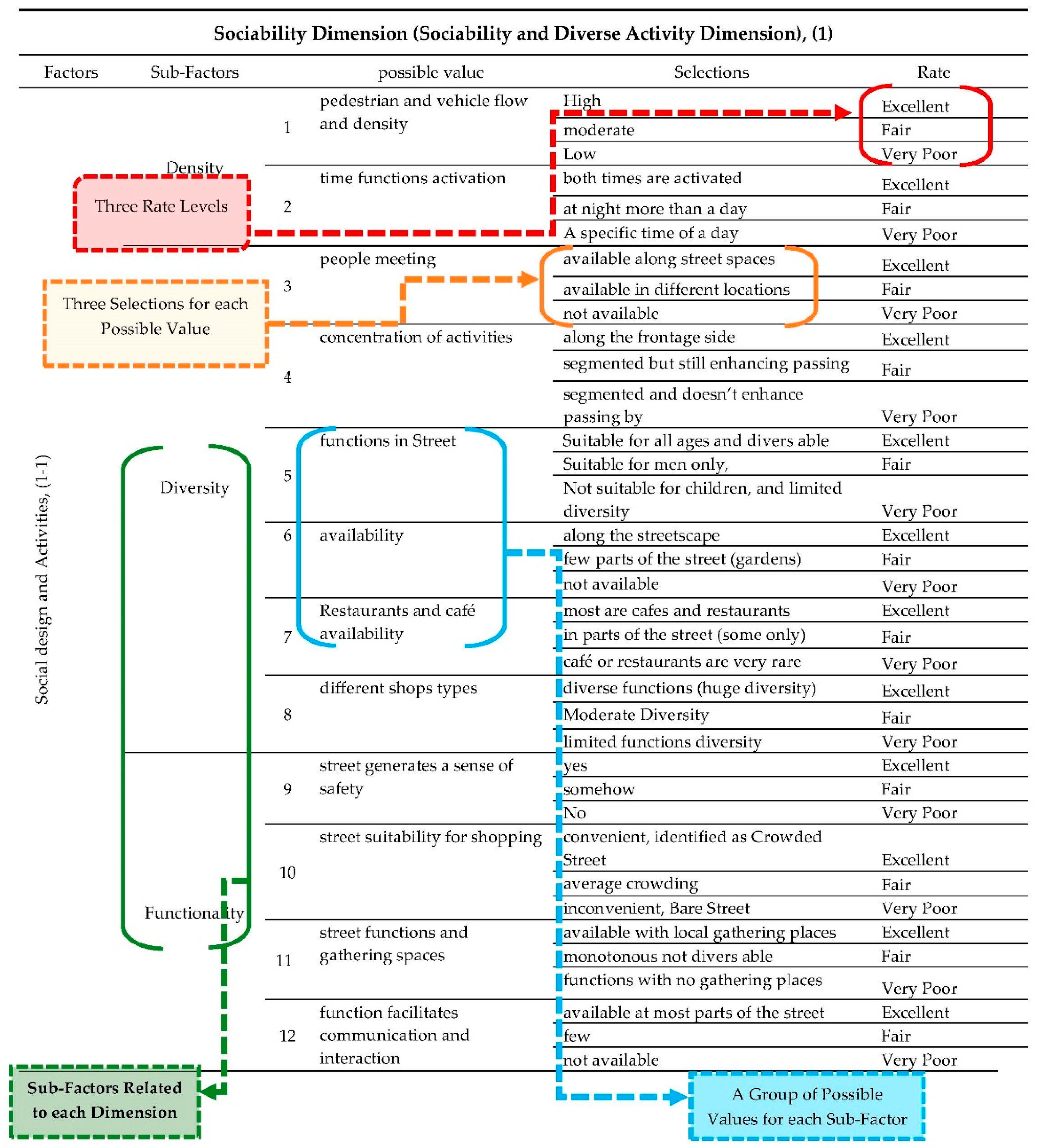

- According to the previous literature, the aforementioned (Theoretical Framework) was reconfigured into a (Practical Framework) consisting of three main pillars. Consequently, the organization of these three dimensions has been reduced and restructured as shown in Table 1.

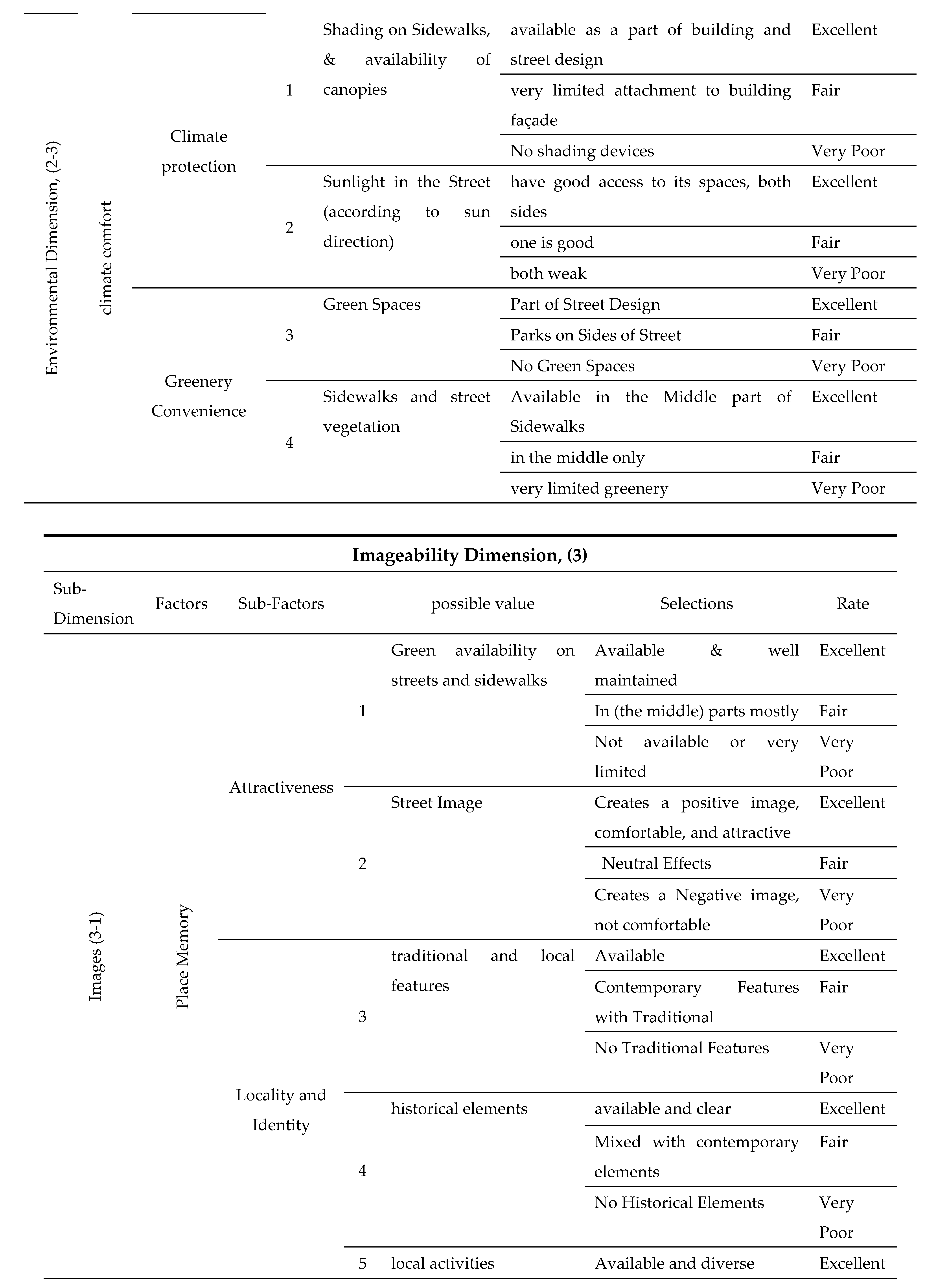

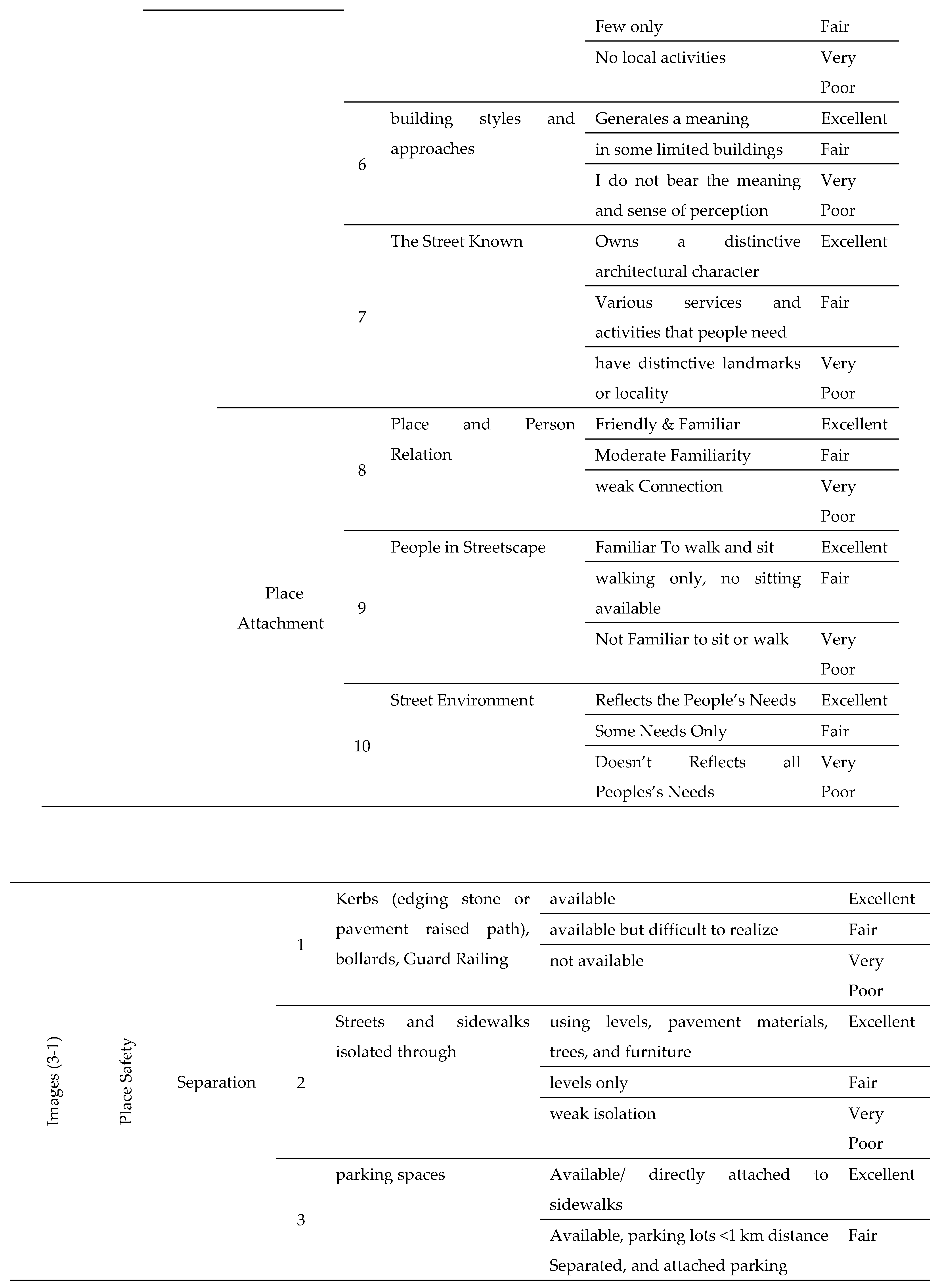

- The research decided to identify three basic dimensions: Physical Setting, Sociability, and Imageability. Each dimension is subdivided into another secondary dimension, factors, secondary factors, and possible values, Figure 11.

- The research adopted these dimensions and factors to place the foundation of the Practical Framework. The placemaking framework has been identified, constituting the appropriate approach for assessing P.M. strategies in commercial streets.

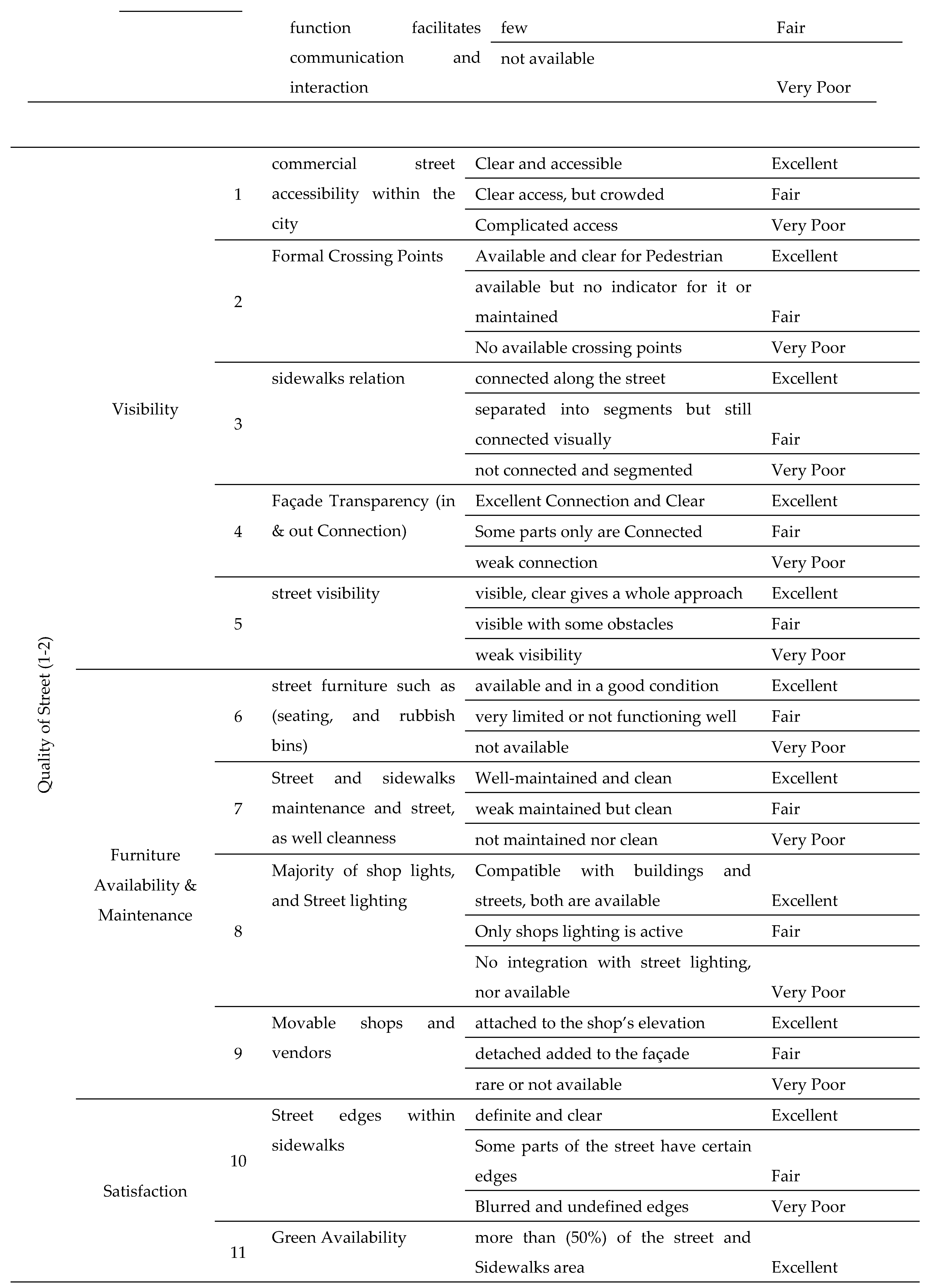

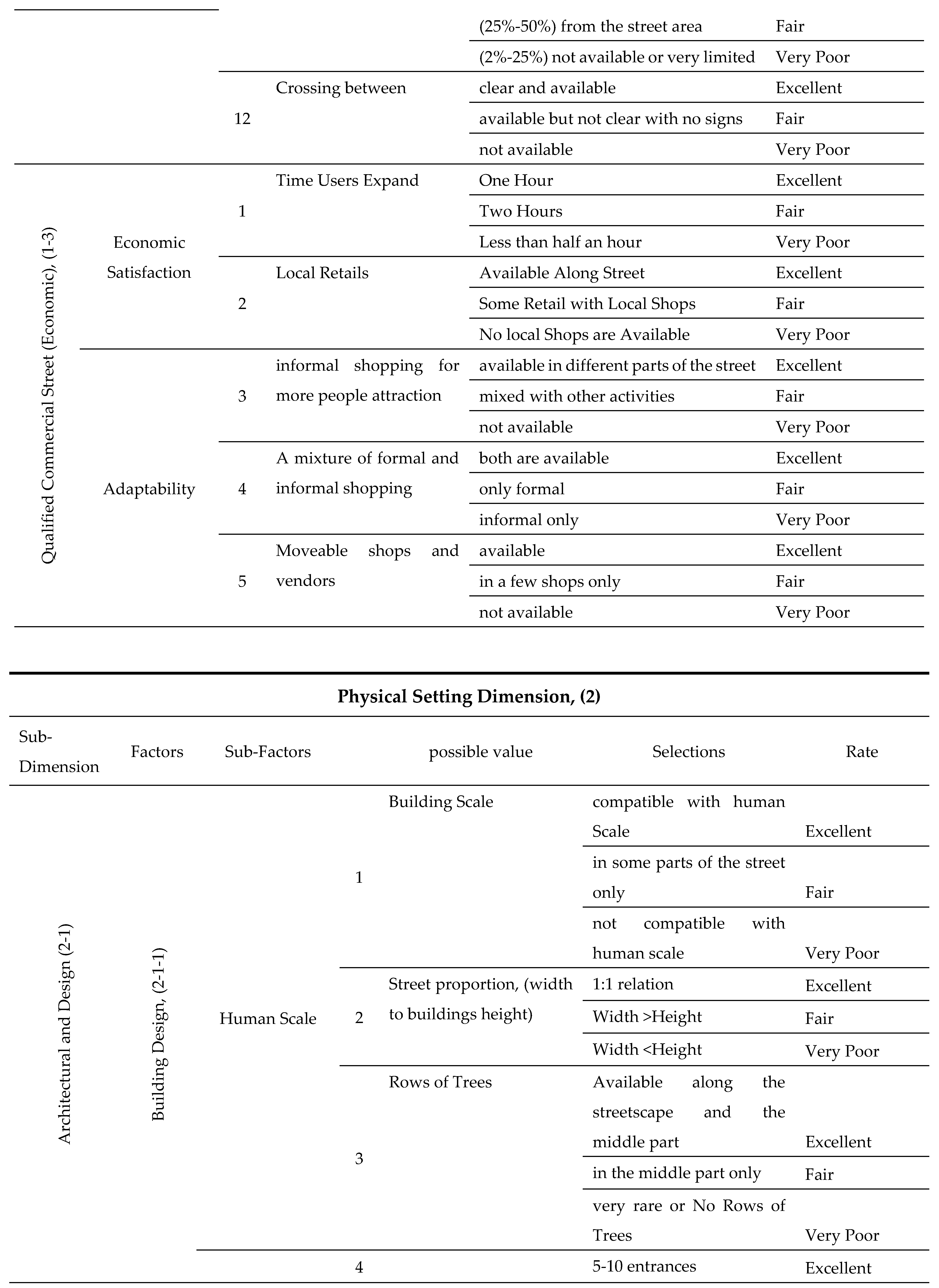

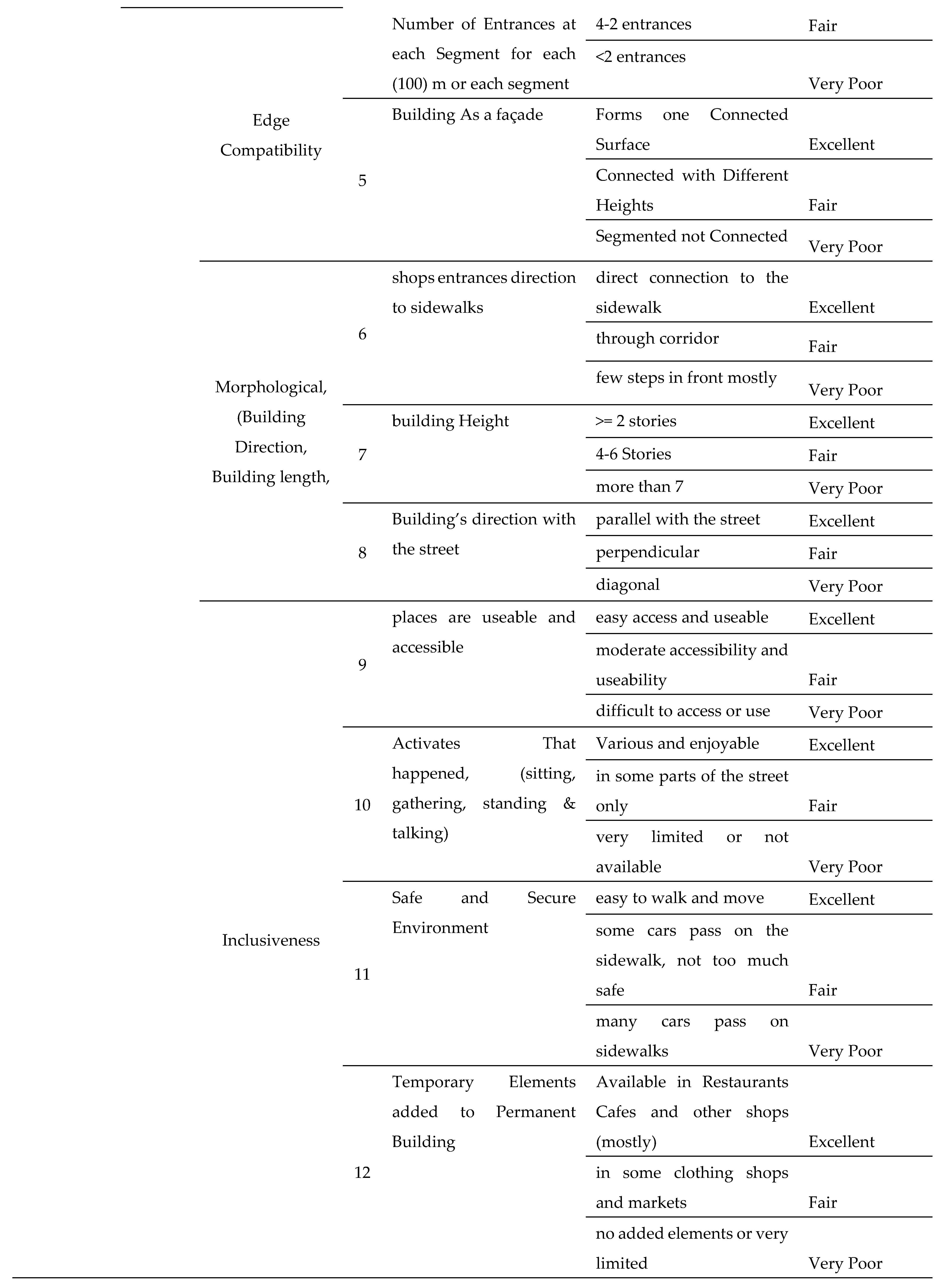

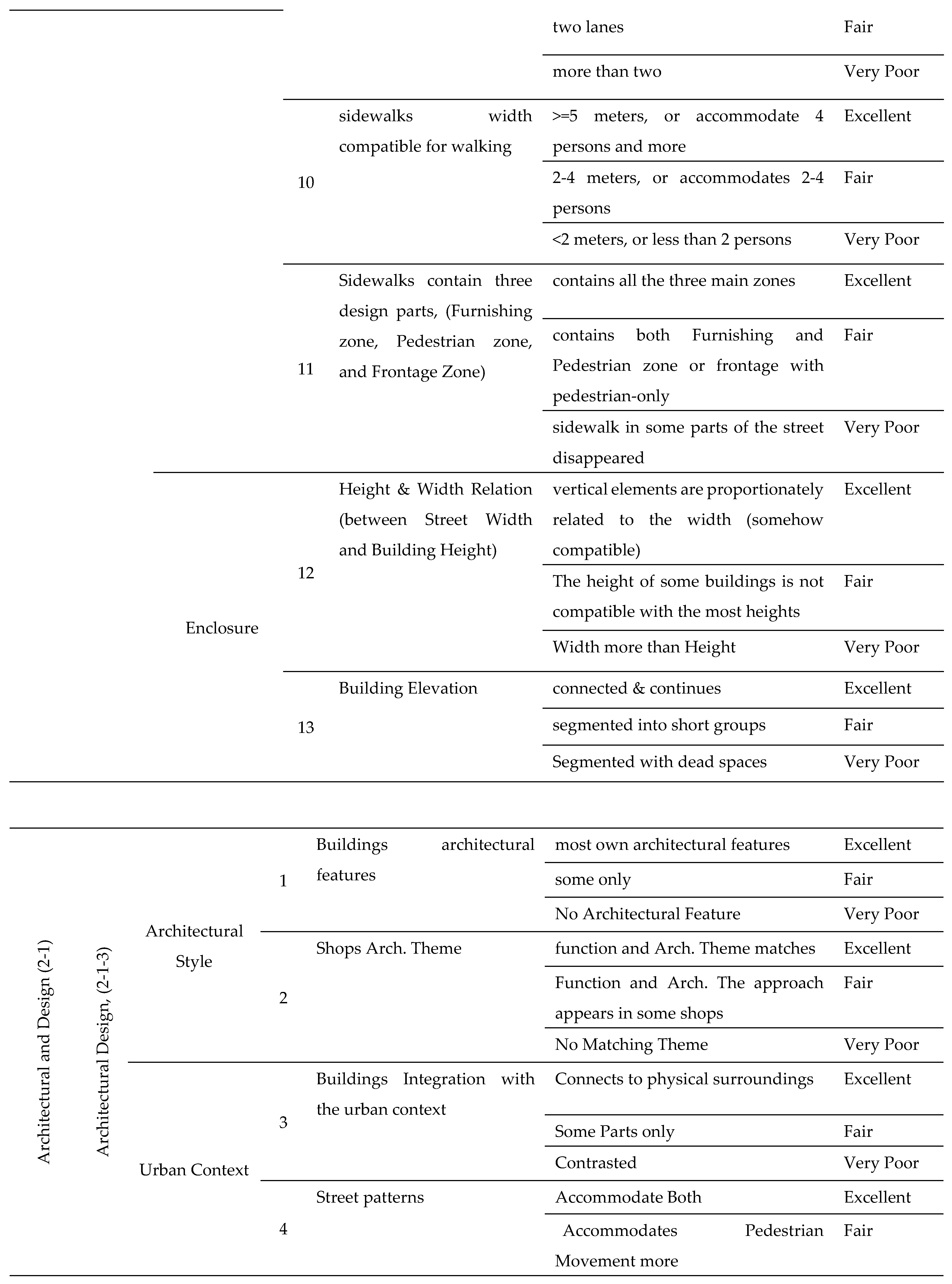

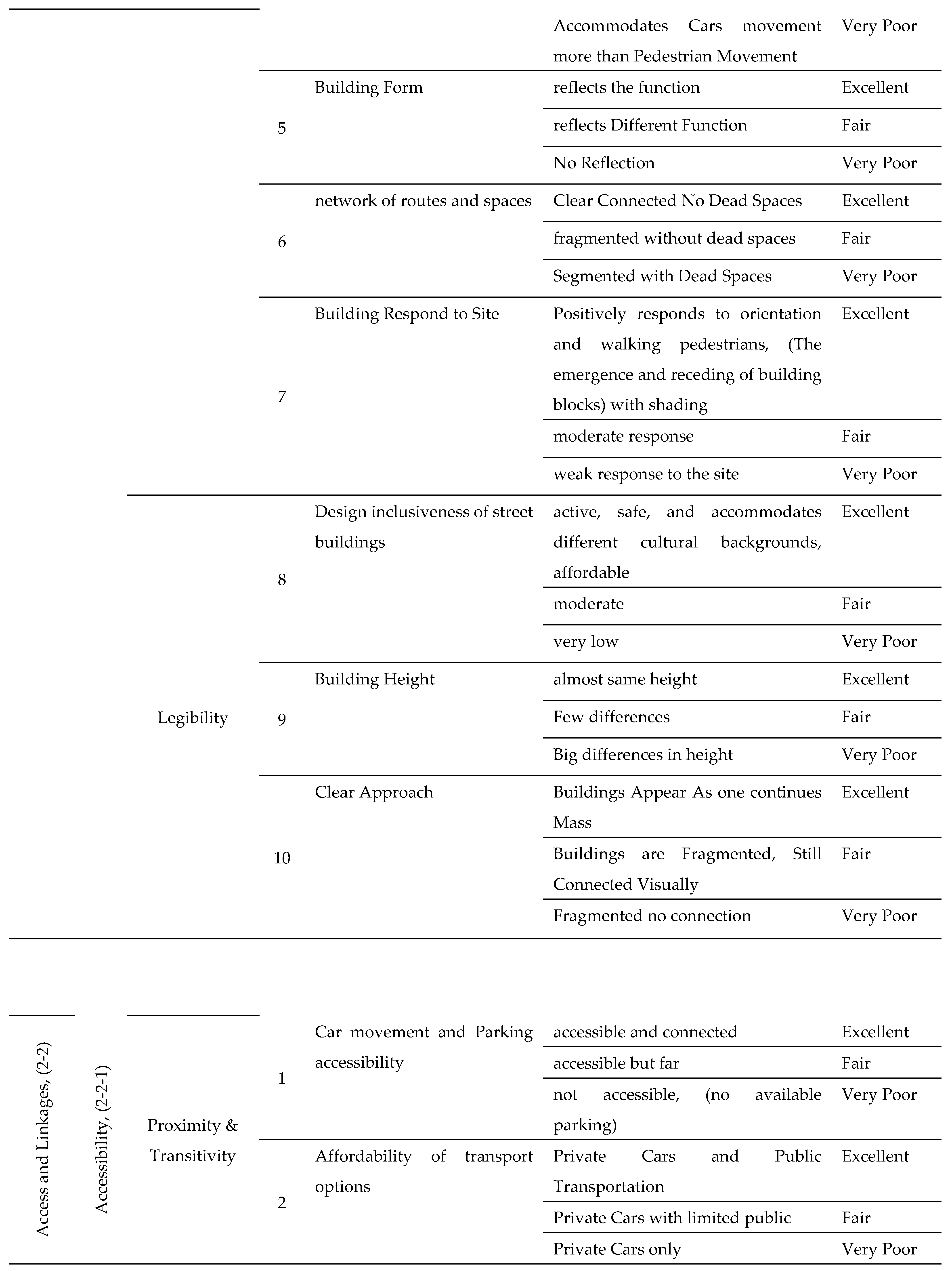

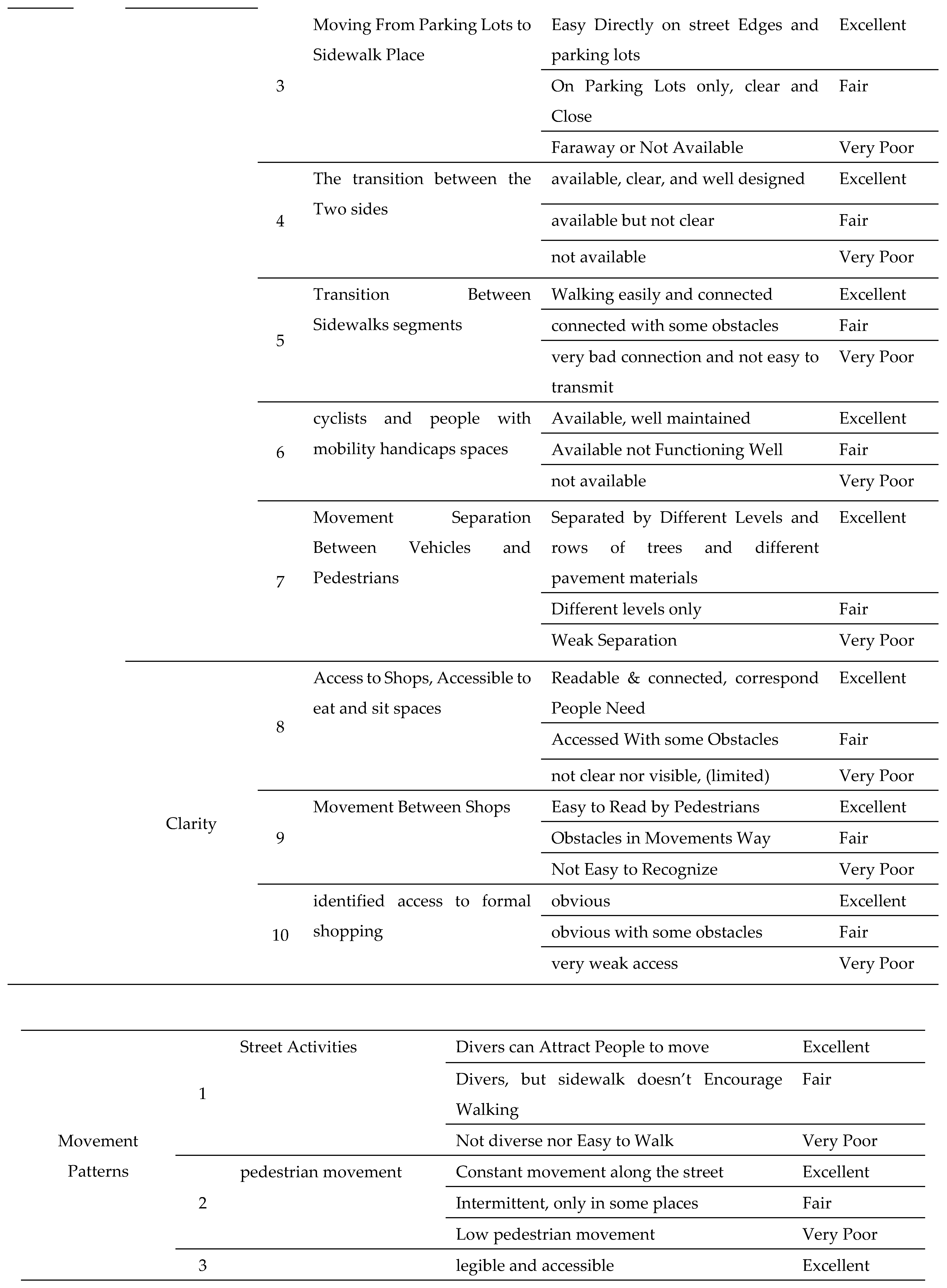

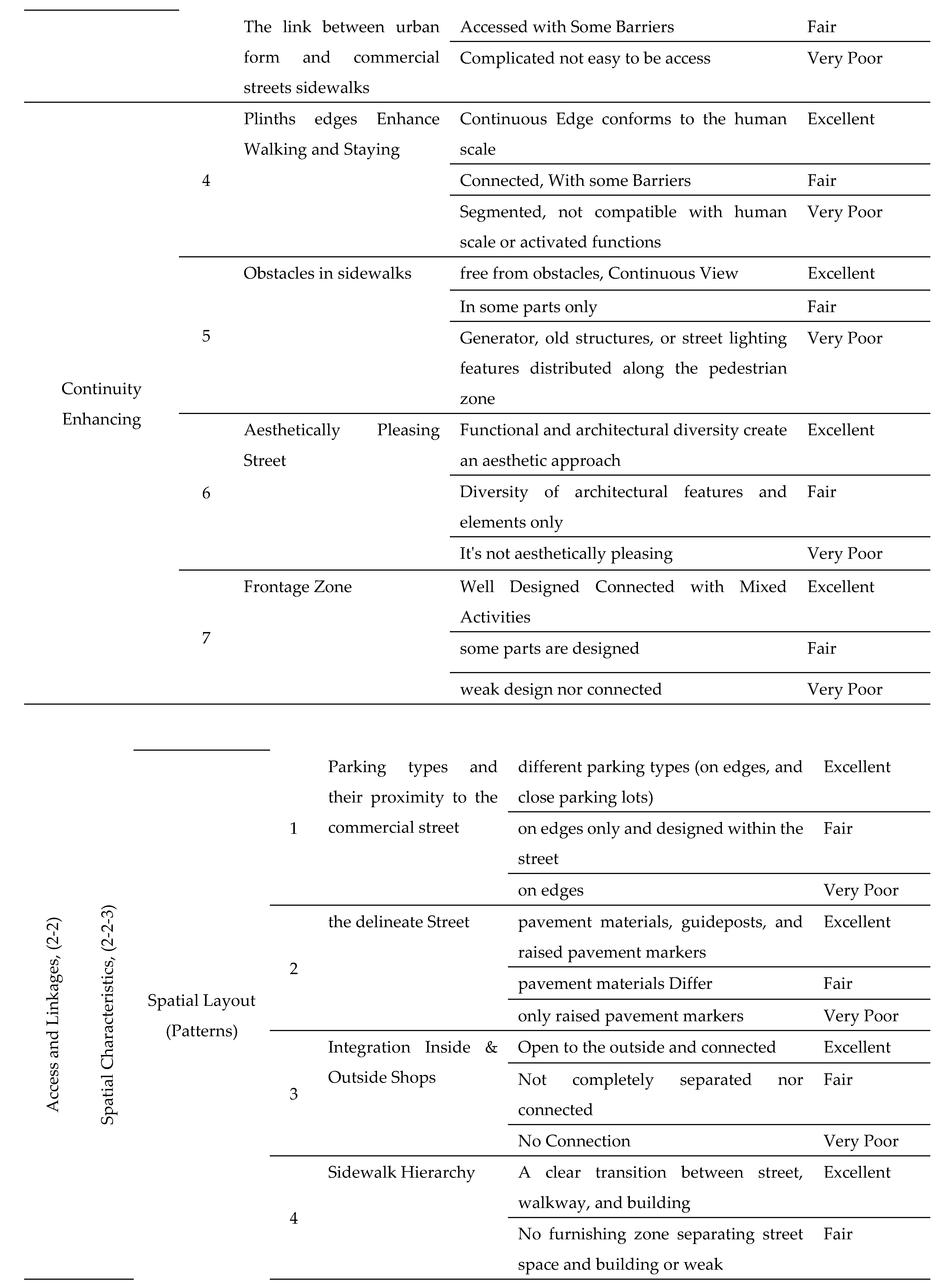

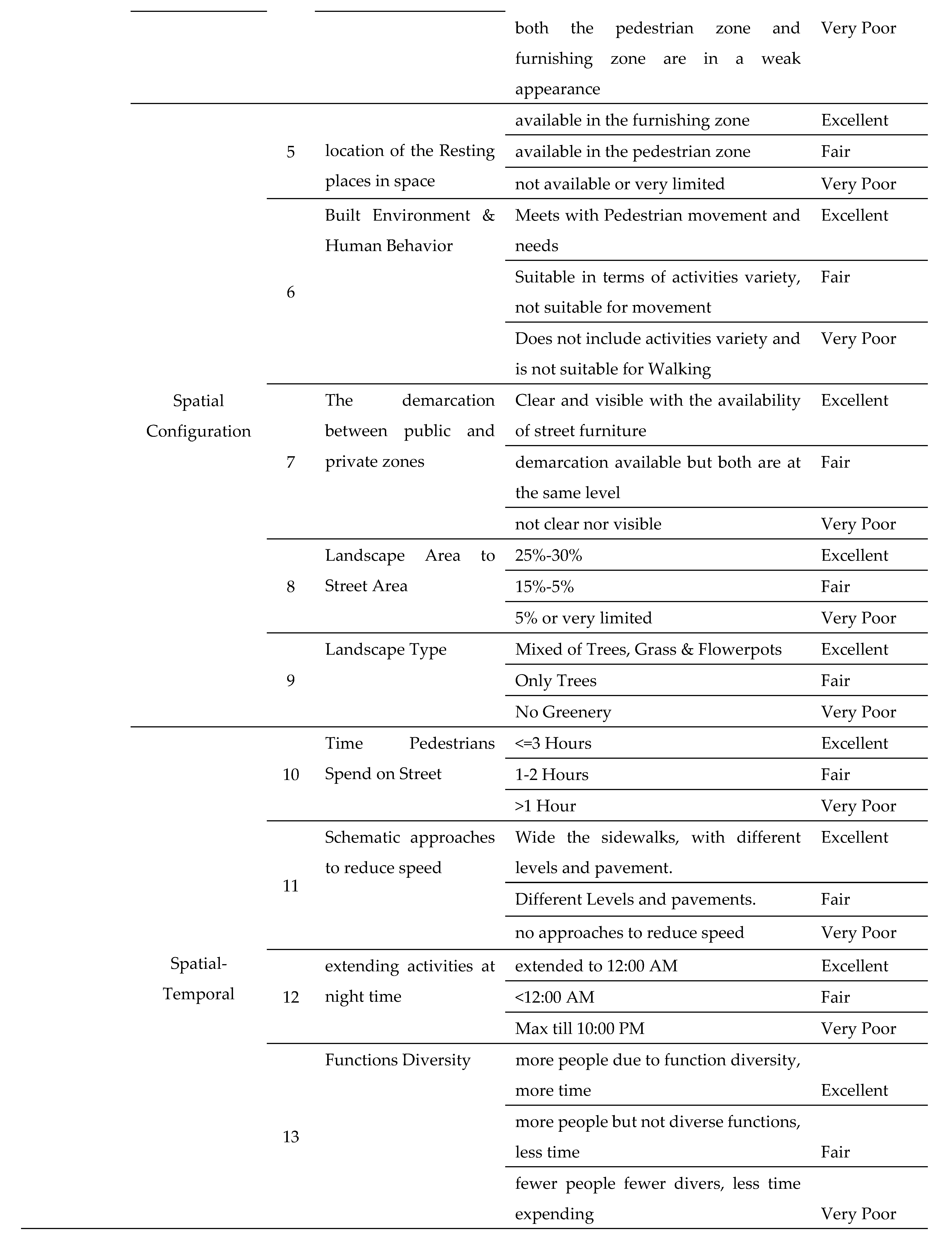

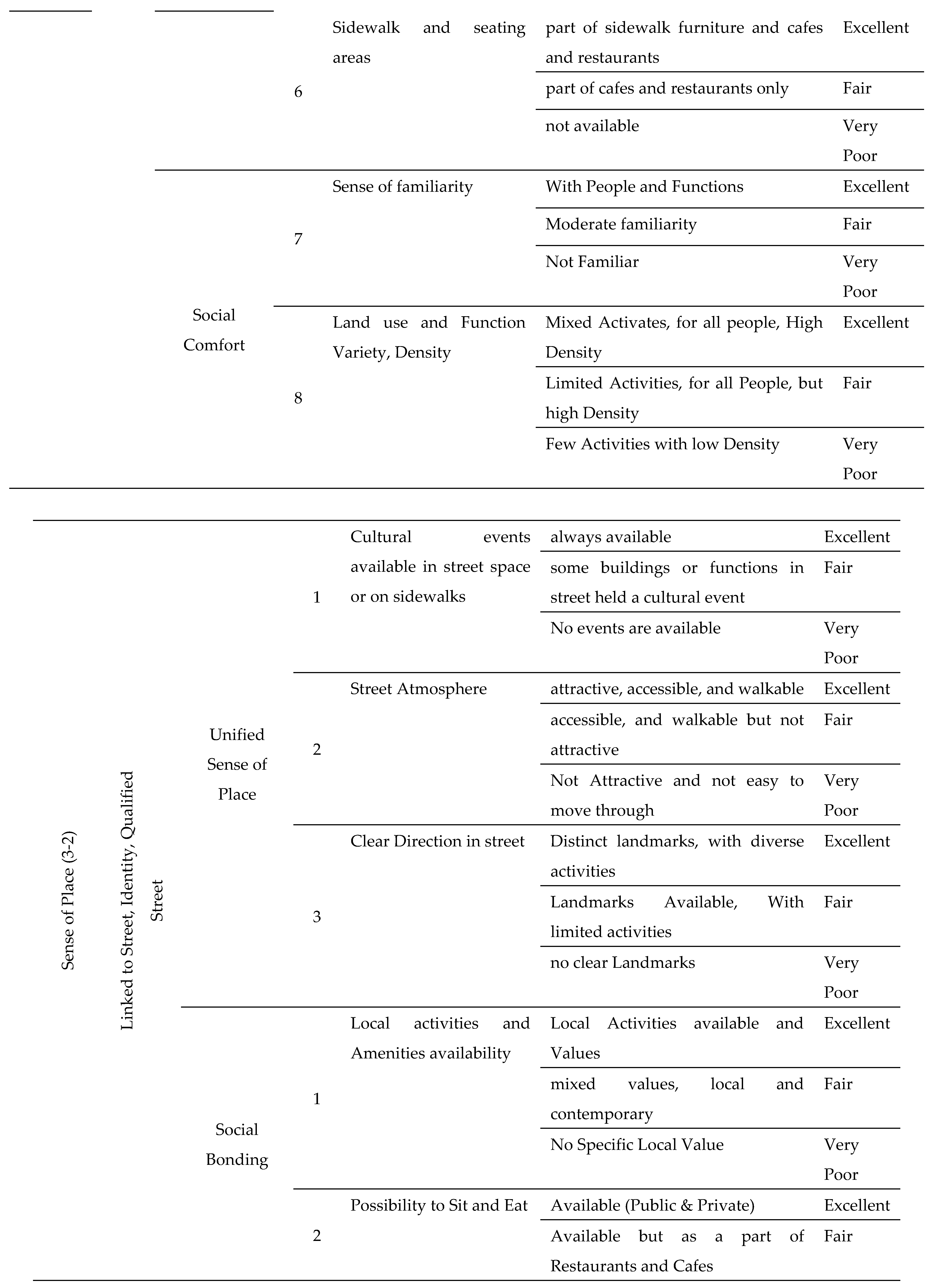

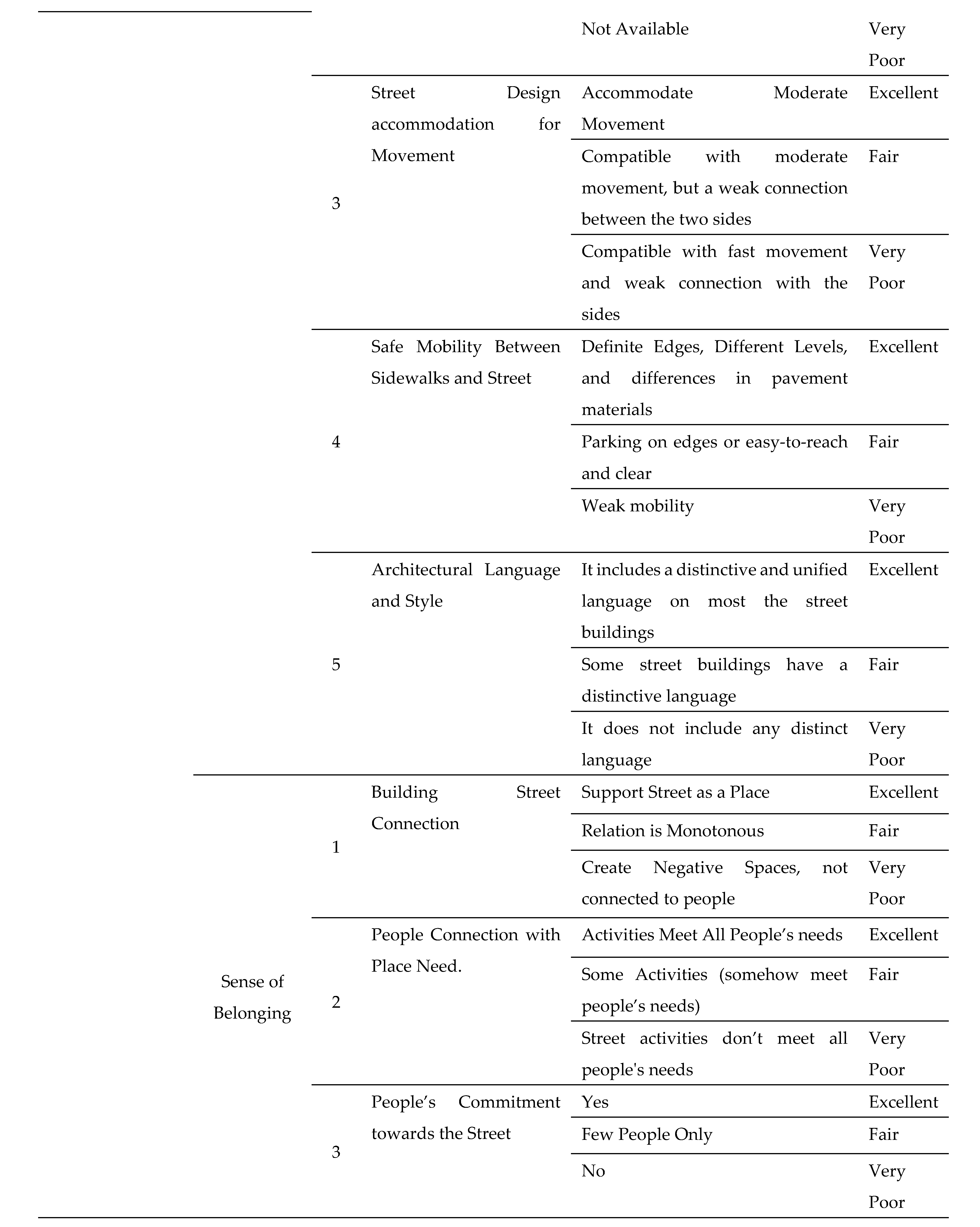

- The practical framework consists of 5 sequences, starting with dimensions, sub-dimension, factors, sub-factors, and possible values which have detailed selections regarding every single factor that appeared as a descriptive approach to identify the best or worse phenomena in the street, example for the Practical Framework Table 2. For more details, the whole (practical Framework) is available in appendix part B.

- Three basic dimensions identified within the model and the Framework, are as follows:

2.2.1. Sociability Dimension

2.2.2. Physical Setting Dimension

2.2.3. Imageability Dimension

2.3. Placemaking Framework

2.4. Study Method

2.4.1. Selecting the Street

- The first stage is to identify several streets to which the specifications for commercial streets apply.

- The research decided to select the connector streets between the circles of Erbil city, as it was categorized by a set of characteristics that qualified it to be crowded and diverse commercial streets.

- The width of the selected streets is between (20-50) m, and the lengths ranged from (600-2000) m.

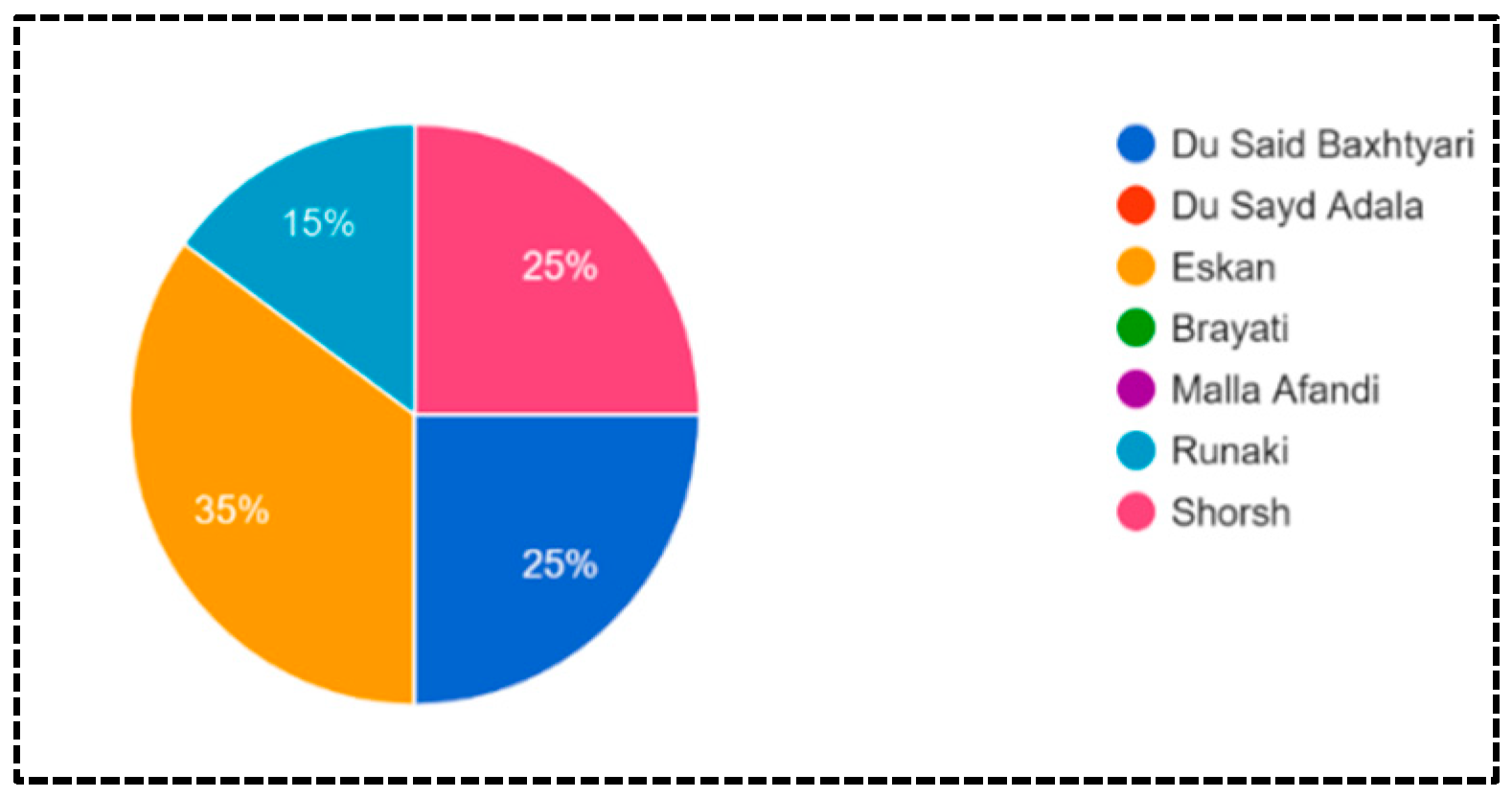

- A quick pilot study was conducted in which people were asked about their opinion of the most lively and livable street, Figure 13. Among the seven commercial streets, Eskan with the higher rate (35%) has been selected as the research sample.

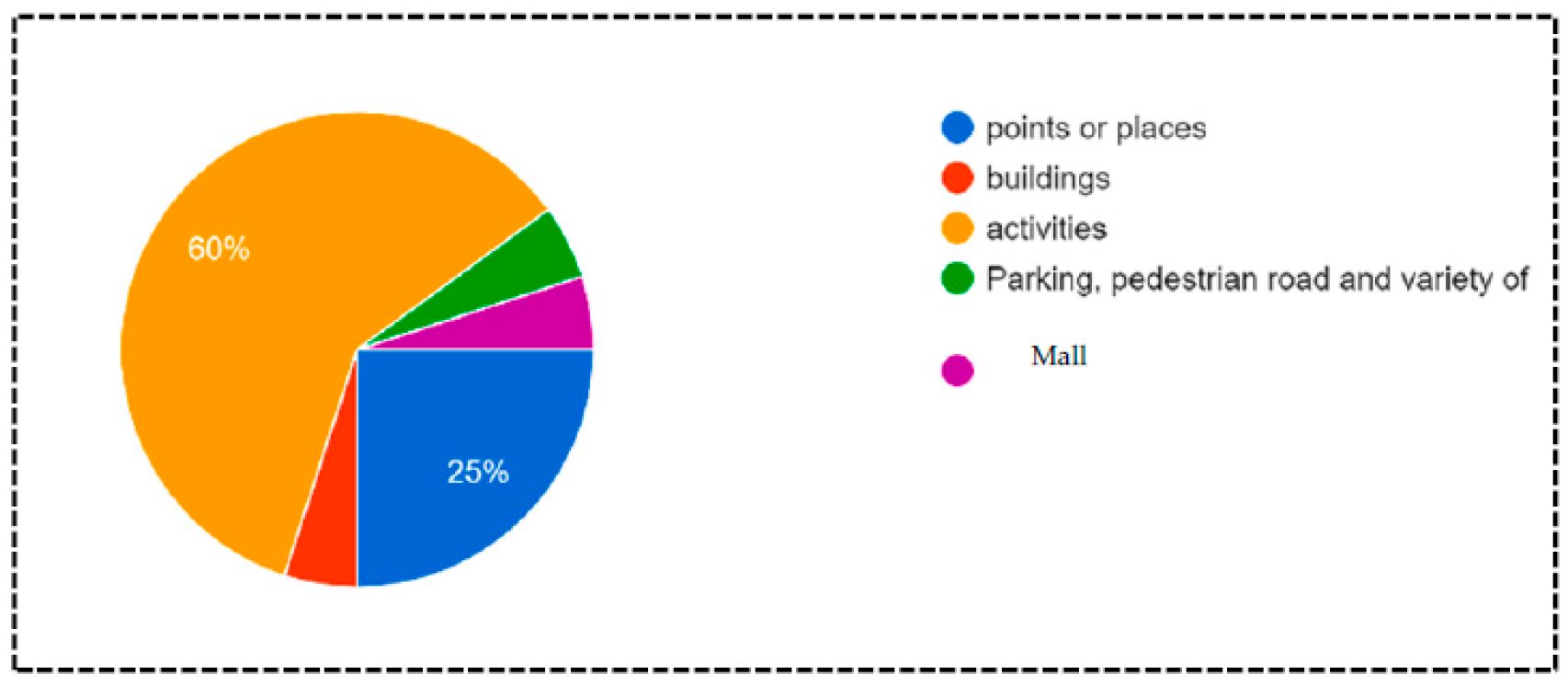

- People identified the reason for choosing this street as being multi-functional and diverse, with attraction points, in addition to being a street that contains two parking spaces. Figure 14.

- Eskan Street was adopted as a research sample to apply a placemaking Framework, and assess livability.

2.5. Case Study

2.6. Street Description

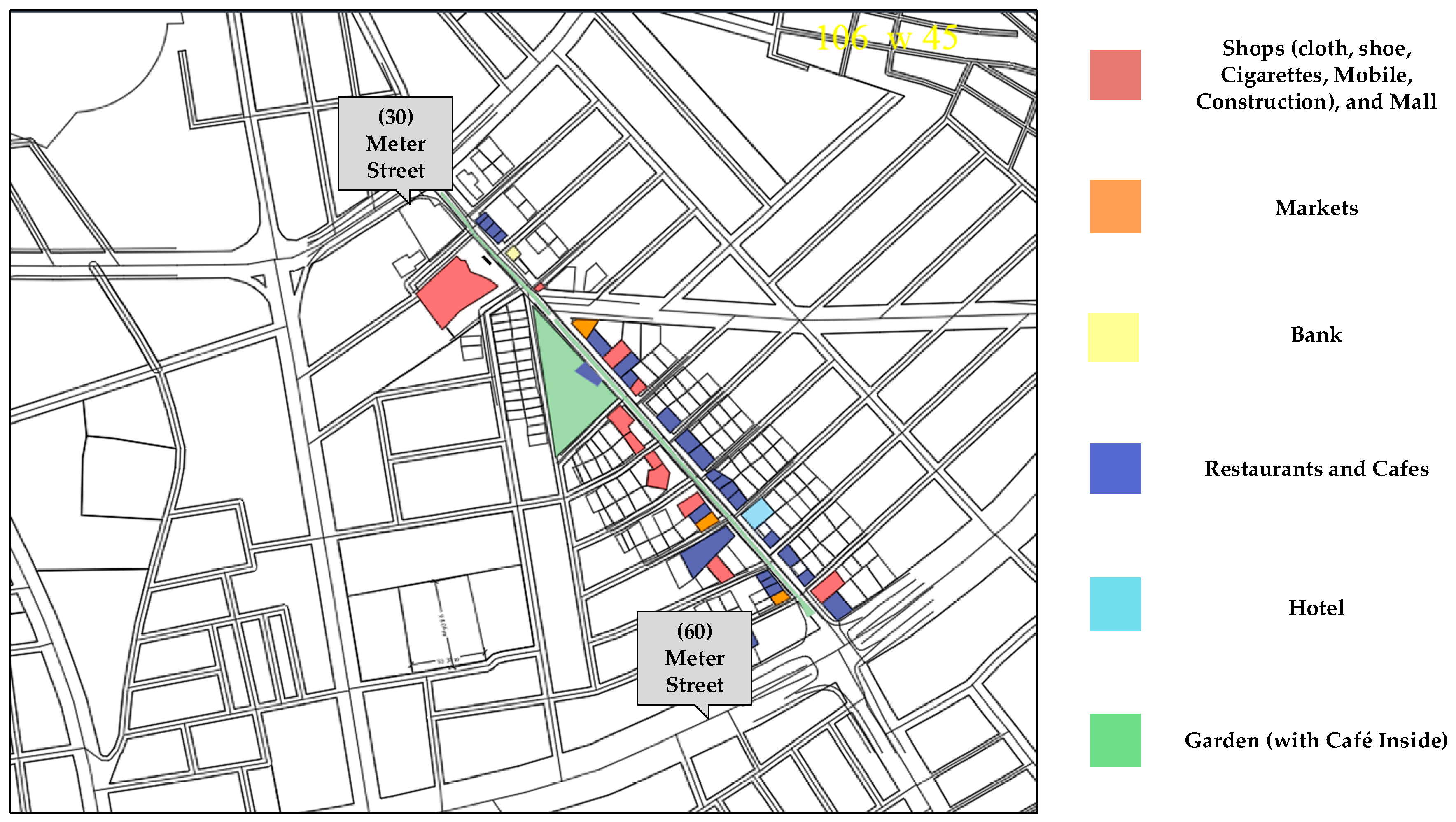

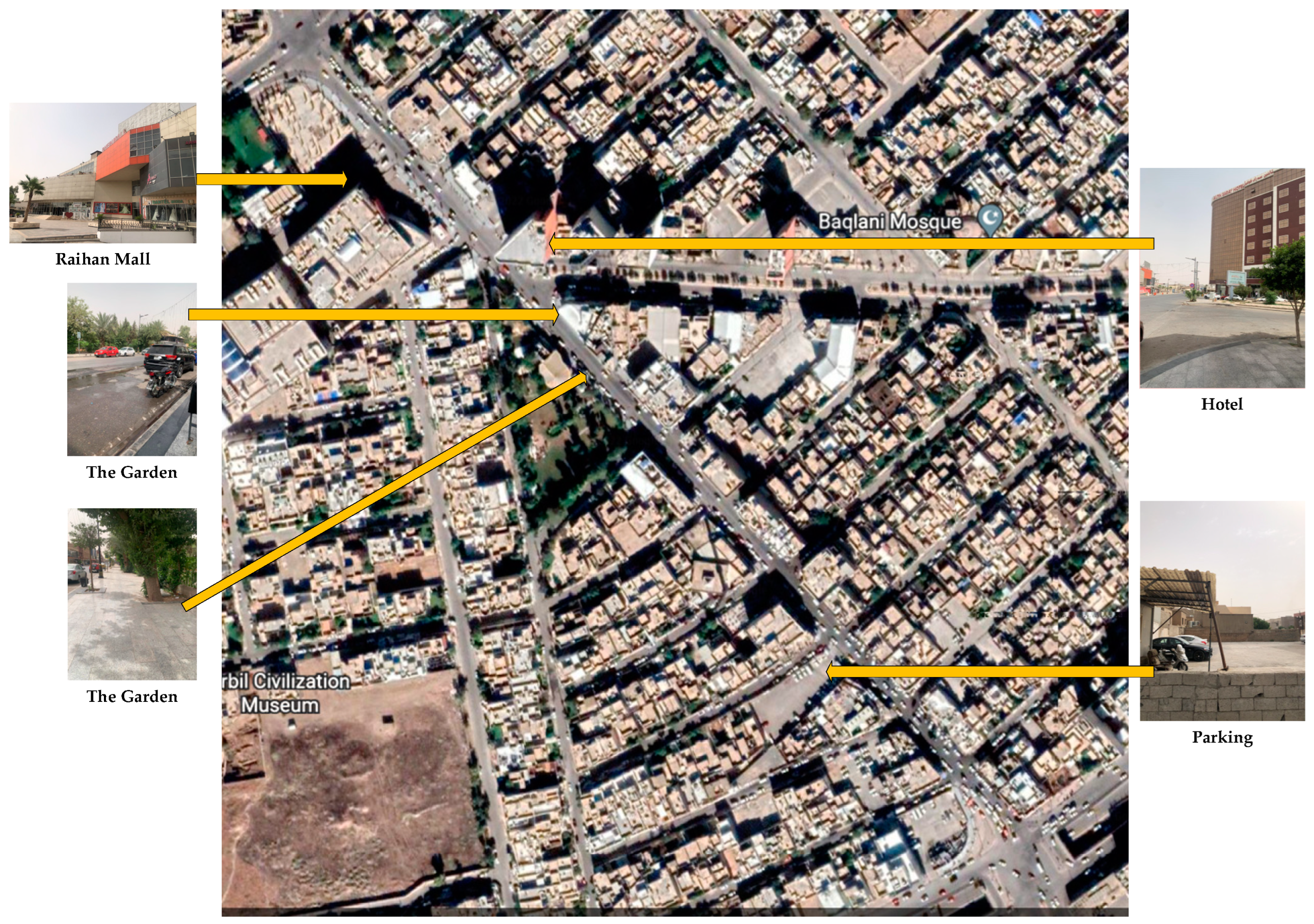

- Eskan Street is one of the crowded streets frequented by many Erbil residents as well as tourists, the street connects two vital streets in Erbil city, the (30) Street, and the (60) Street, Figure 15.

- The street is distinguished by its many activities and the variety of restaurants and cafes, most of which are local dishes.

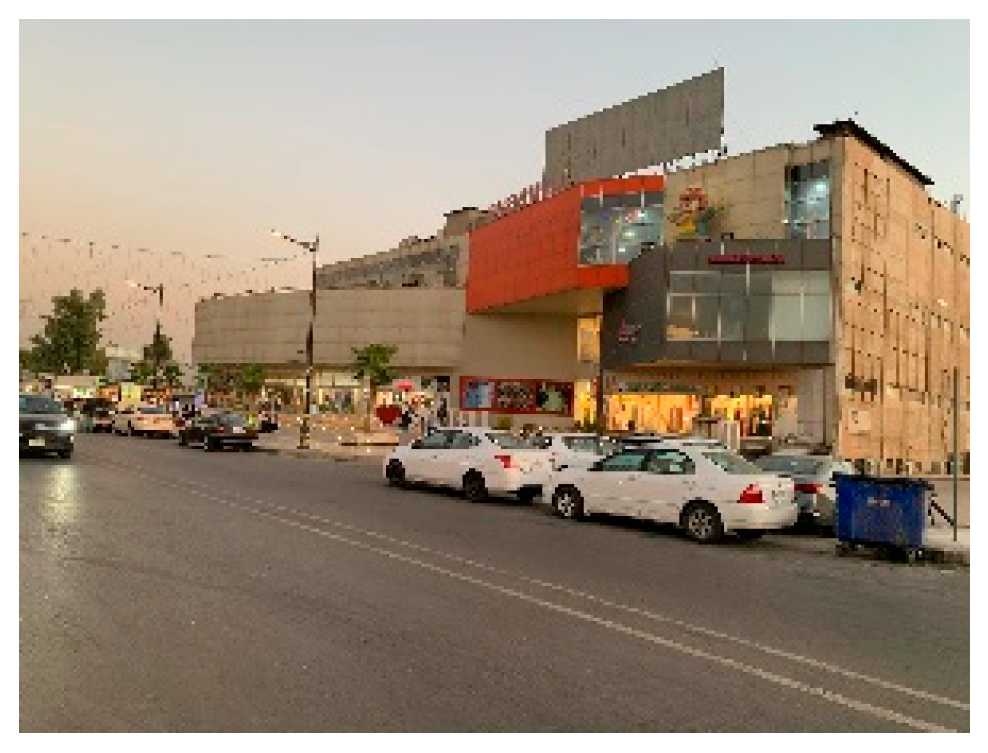

- It also includes other activities such as hotels and motels, markets, mobile shops, car accessories, and clothes shops, in addition to tailors and barber shops. At the end of the street, towards the city center to (30) street, there is a large mall with many shops and various activities. Figure 16.

- The street includes several cafes, which are considered a good entertaining place for many young people.

- It contains a large garden that occupies the left side of the street, with an area of approximately (6,592) m2 as a cafeteria.

- The length of the street is approximately (670) meters with an area of (12,226) square meters and a width of (20) meters.

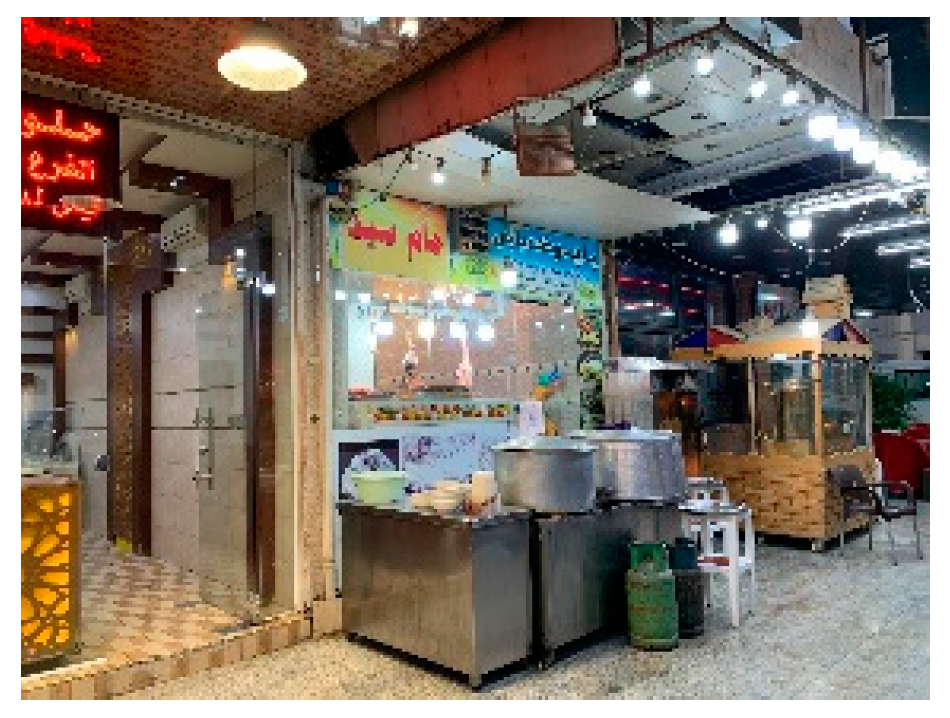

- The street contains many carts and booths selling local foods and juices, varying according to the seasons of the year.

2.7. Methods

2.7.1. Field Survey

- The research depended on several ways to collect data, the first of which is the field survey, it was divided into three main parts, the physical part including; urban, design, architectural details, and factors related to both street and sidewalks, furniture, street vegetation, and diverse activities. The social aspect and the imageability aspect.

- The field survey included three basic times: 9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 9:00 p.m. Information was entered into the survey table to determine diversity, social difference, and people density to which activities according to the times between day and night.

- The field survey was carried out during two seasons (summer and winter).

- In Summer, the survey began on (15 June to 15 July) and three times per day, from (9:00 am-1:00 pm, from 2:00 pm-5 pm, and then from 6:00 to 9:00, to midnight.

- For the period between (9:00 a.m.-1:00 p.m.), most of the activities that operate during this period are supermarkets, mobile, and construction shops, and the most effective ones are restaurants and cafeterias that serve breakfast for people going to work. Since the location of the street has a close connection with Erbil city center, where most of the businesses take a place, people use these restaurants for breakfast before going to work. Then density gradually reduces for an hour (but never decreases).

- Density and overcrowding increase again and for the period between (12:00 p.m.-2:00 p.m.) due to the lunch period.

- The fact that the street offers local and popular dishes and their prices are affordable in addition to the location of the street within the city, was among the reasons for the density.

- In summer, for the period between (2:00 p.m. -6:00 p.m.) people’s motion decreases due to the intense heat, and the density gradually returns from (6:30 p.m.-12:00 a.m.). On holidays (Friday and Saturday) People stay up until 2:00 am.

- The survey times included these periods to determine the people density and most used activities.

- Some construction shops and mobile services end at (6:00 p.m.). Continuing to work are sweet shops, markets, and defiantly restaurants and cafeterias.

- In summer, the garden operates from 6:00 p.m.-12:00 a.m. It is rarely used during the day due to the heat. The garden returns to work after daytime hours at night.

- The survey was repeated to identify the most important changes and activities that flourish in winter.

- The survey was for a month as well, and it lasted from (15-December-15-January), and for three times: (9:00 a.m., 1:00 p.m., and 4:00 p.m.).

- Juice shops have changed to shops serving tea, coffee, and traditional sweets.

- The use of the garden changed from hours after (6:00 pm) to daytime hours from (12:00 p.m.- 5:00 pm at sunset).

- In winter, activities did not continue till midnight, most of them ended at 8:00 and 9:00 p.m.

- In general, the use of the street in the summer lasted longer hours than the day, but the movement usually increases in summer after (6:00 p.m.), since the temperature decreases and it facilitates the movement of people in extremely hot weather.

- On the other hand, after (6:00 p.m.) in winter, the movement of people decreased, so it was noticed that some shop owners put temporary structures made of nylon material, with a fireplace on wood and gas within the space of the street in order to create a comfortable atmosphere for use by people.

2.7.2. Observation

- The movement of people and the density were monitored and on which activities the density of people was higher.

- The most frequently used activities and the ages and genders of the people who mostly use the street.

- Formal and informal activities, as in Erbil culture people like eating and drinking local foods, booths, and carts present affordable local food.

- Pedestrian movement, ease of walking, accessibility, sidewalk width, suitability for movement, and the number of people within sidewalk space.

- Transfer between the two sides and the appropriate physical features and elements that facilitate the transition.

- Amenities and furniture and their availability within street space and sidewalks.

3. Results & Discussion

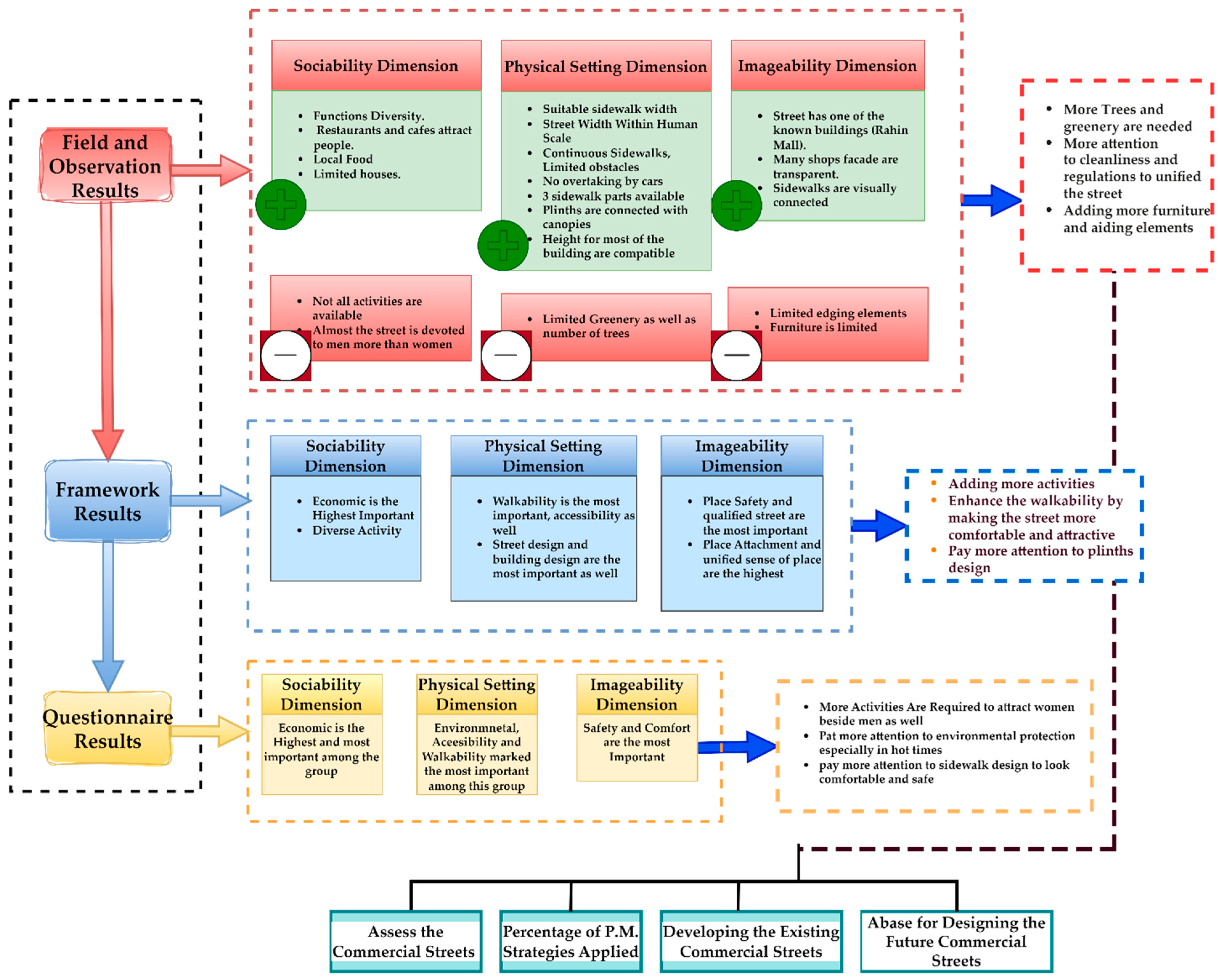

3.1. Field and Observation Results

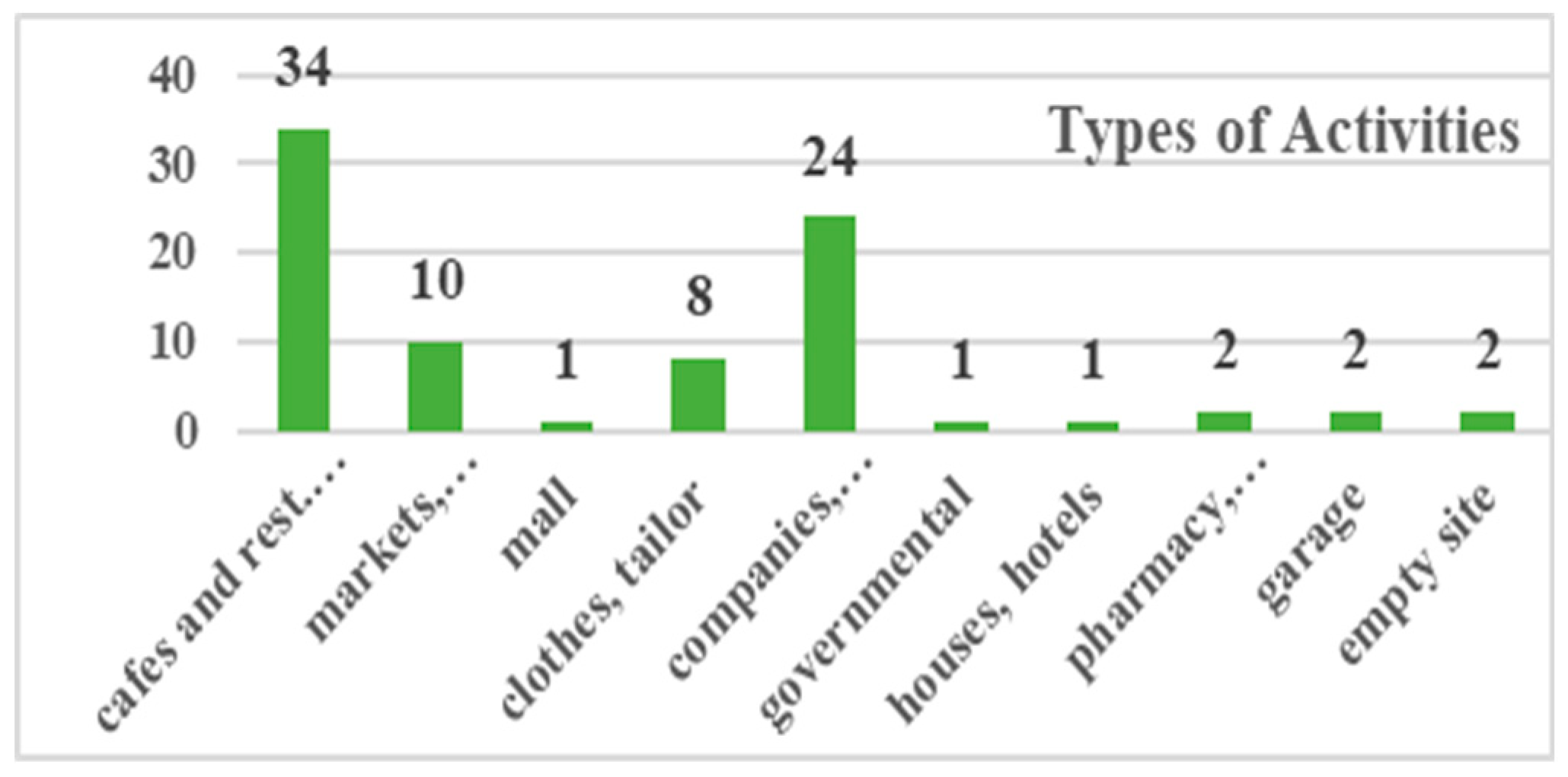

3.1.1. Activities and land use in Street, (Sociability)

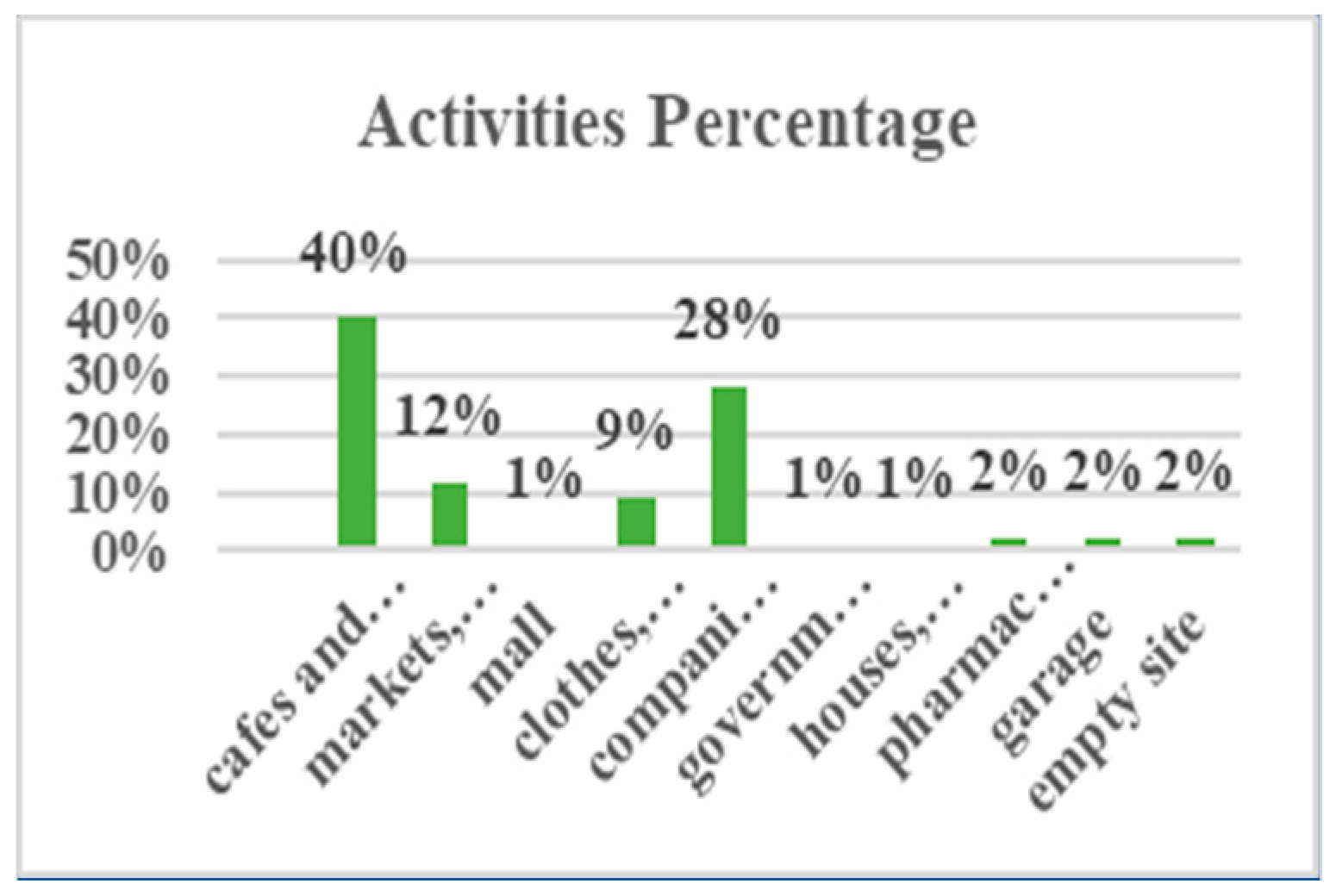

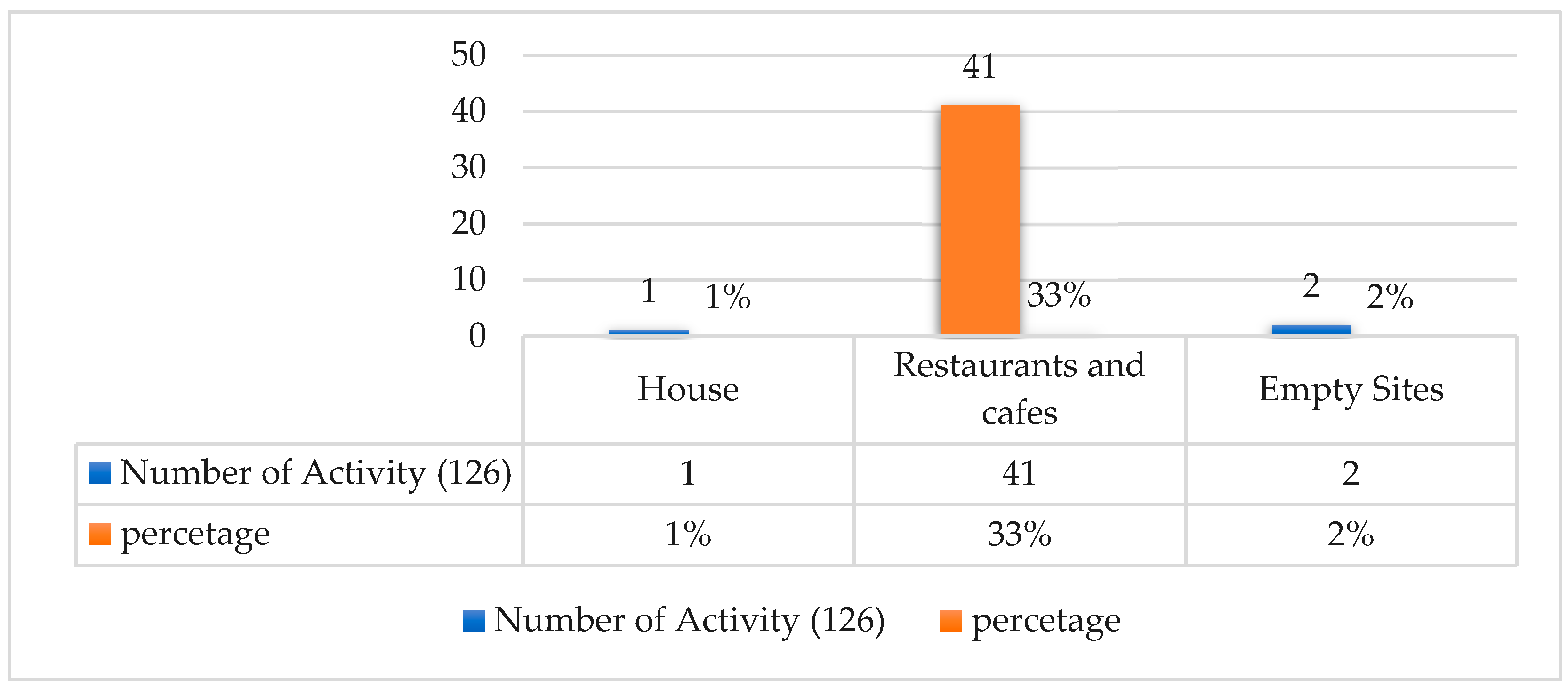

- Types of uses and functions have been identified in the street on both sides, the street has a variety of uses, but the largest percentage was for restaurants and cafes, followed by construction companies, real estate, car accessories, clothing stores, and tailors in the third rank. Figure 17, Figure 18.

- Activities were mostly restaurants and cafeterias, the food served in the restaurants varied greatly between local and fast food, and this affects attracting many people, mainly men.

- The street contains many other shops that meet people's daily needs.

- A large mall from the (30) street side occupied with many shops, services, and clothes frequented by people from all parts of the city. Figure 19.

- The number of restaurants and cafeterias had a great impact on attracting people, especially young people. In some important events such as the (world cup), which was held in December 2022, the street is closed and cars are prevented from passing in, to provide a suitable environment for people to move safely and to exploit the street and accept the largest number of people since the sidewalks cannot bear a large number of people, Figure 20.

- One of the attraction points for people is the presence of food and juice carts and booths, with a variety of meals change what serves between the seasons from juices and cold drinks in summer, and hot local foods and drinks in the winter such as (tea, baklava, hummus, broad bean, and turnip). Many people buy these foods or stop by to eat with friends, creating a social gathering, and the feeling of vitality is very evident. Figure 21 and Figure 22.

- The street is crowded all day, except in the early morning hours, at night the traffic is highest, and the speed of the car does not exceed (30) km per hour, this will provide some protection for pedestrians when transitioning between two sides of the street.

- Among the things that negatively affect the continuity of people’s walkability are the presence of activities that interrupt the shop’s continuity or that may not work after (4 p.m.), and empty sites.

- One of the positive points, Eskan Street was almost devoid of houses and empty or unbuilt sites. This encouraged the continuity of commercial facades and thus strengthened the spatial connection, Figure 23. The presence of houses causes the creation of intermittent and dead commercial facades, which affects the facade continuity and people's walkability.

- Building plinths are continuous with diverse activities, and have excellent lighting at night, with a suitable pedestrian area accommodating four people, Figure 24. Plinths are a very important part of buildings, the ground floor, and the city at eye level. A building may be unpleasant, but with a lively plinth, the experience can be positive. The other way around is possible as well as the building can be very beautiful, but if the ground floor is a dead wall, the experience on the street level is hardly positive, [5] (p.18).

- Most of the visitors and users of the street were men. About fifty men walking or buying in the street there were approximately two women. This is one of the negative points of the commercial street.

3.1.2. Physical Setting

- The street sidewalks were distinguished by several positive points that encourage walking, including the width that occupies four people, approximately (5) meters width, and in some parts of it especially in front of the mall, reaches (10) meters.

- Good tiling quality with unified material, most are continued without interruptions (almost the same level), and continuous sidewalk encourages walkability.

- Minimum width of the sidewalk in commercial streets within the central area is (4.8) m, [53] (p.3).

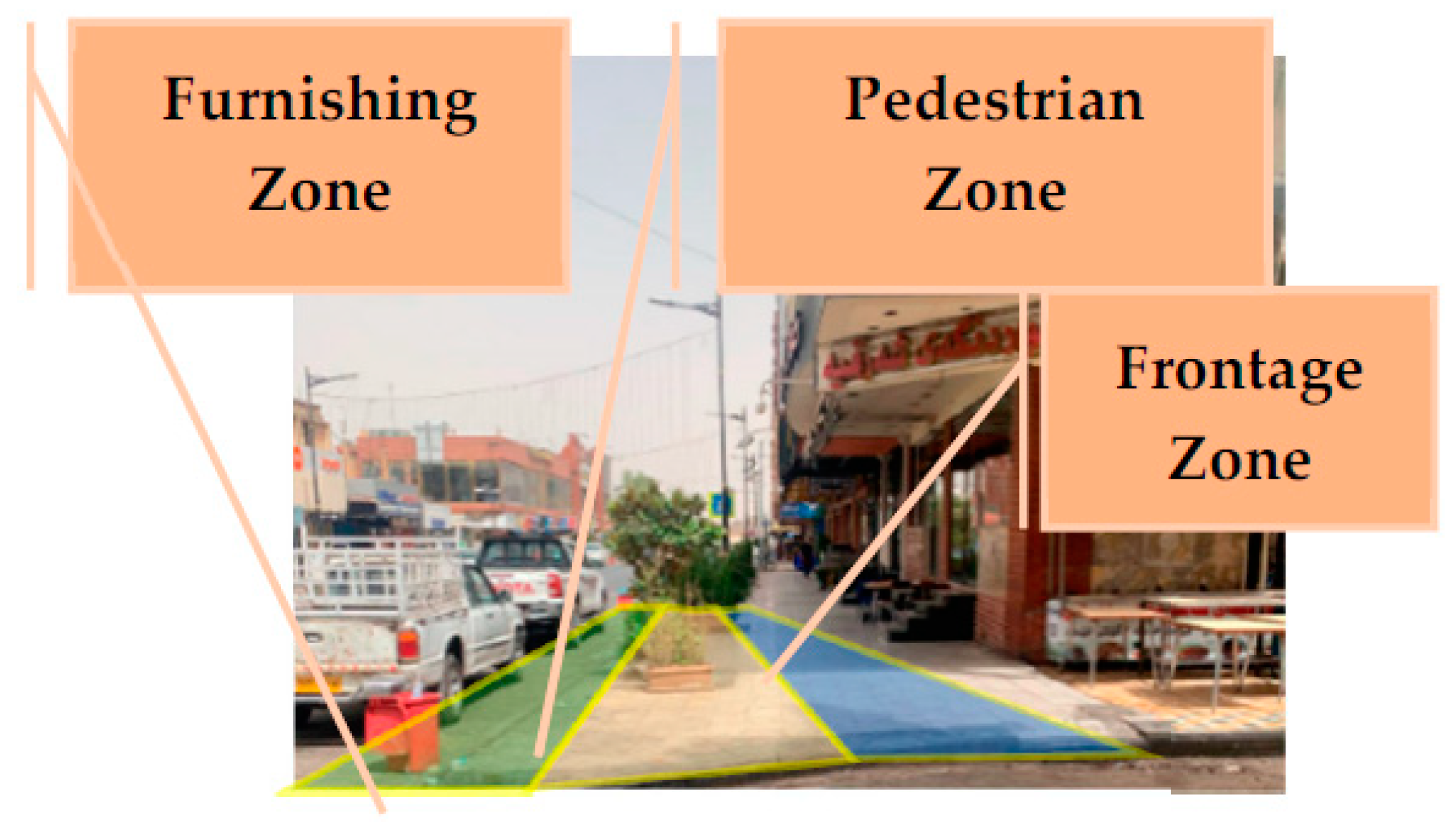

- Sidewalk design includes three design components: frontage zone, pedestrian zone, and furnishing zone. Figure 25.

- The height of the sidewalks was appropriate in a way that prevents any overtaking by cars on the sidewalks or cutting off pedestrian traffic.

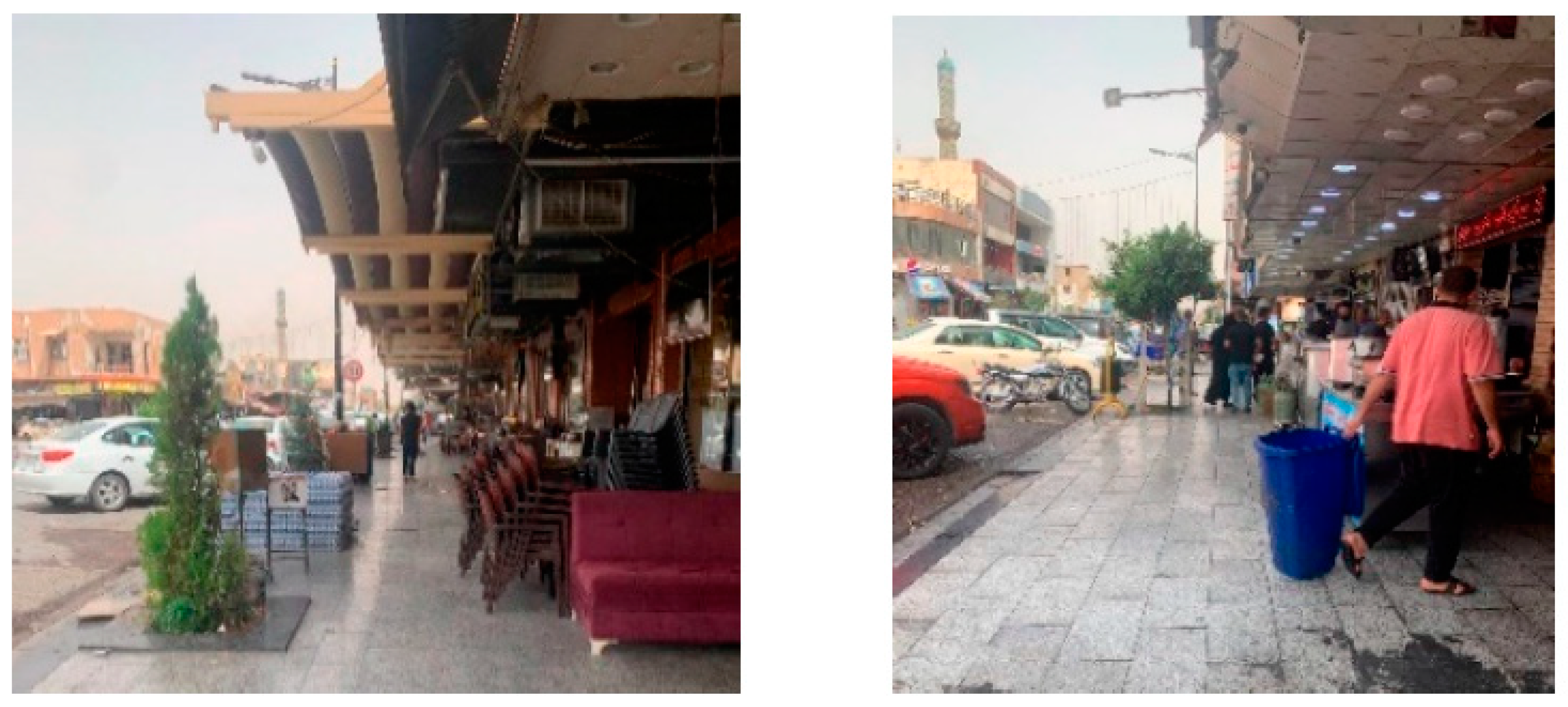

- Despite the lack of canopies that protect pedestrians, most of the buildings had setbacks on the ground floor to allow forming a cover for pedestrians from the sun while walking, Figure 26.

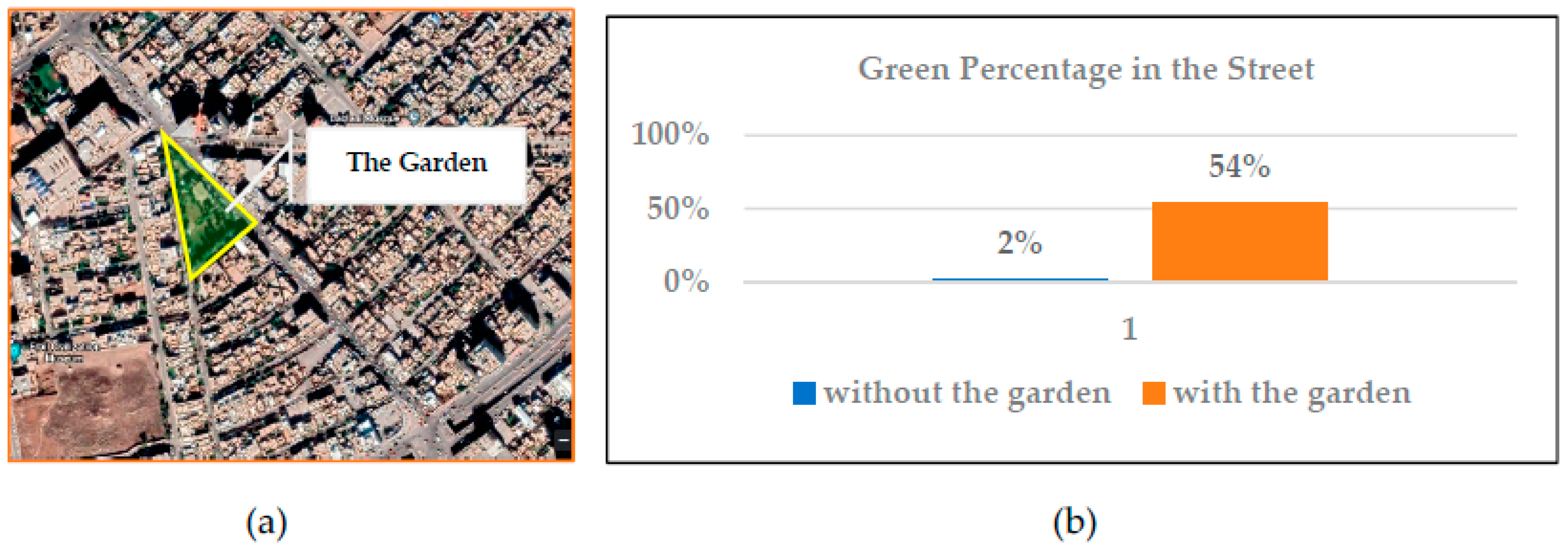

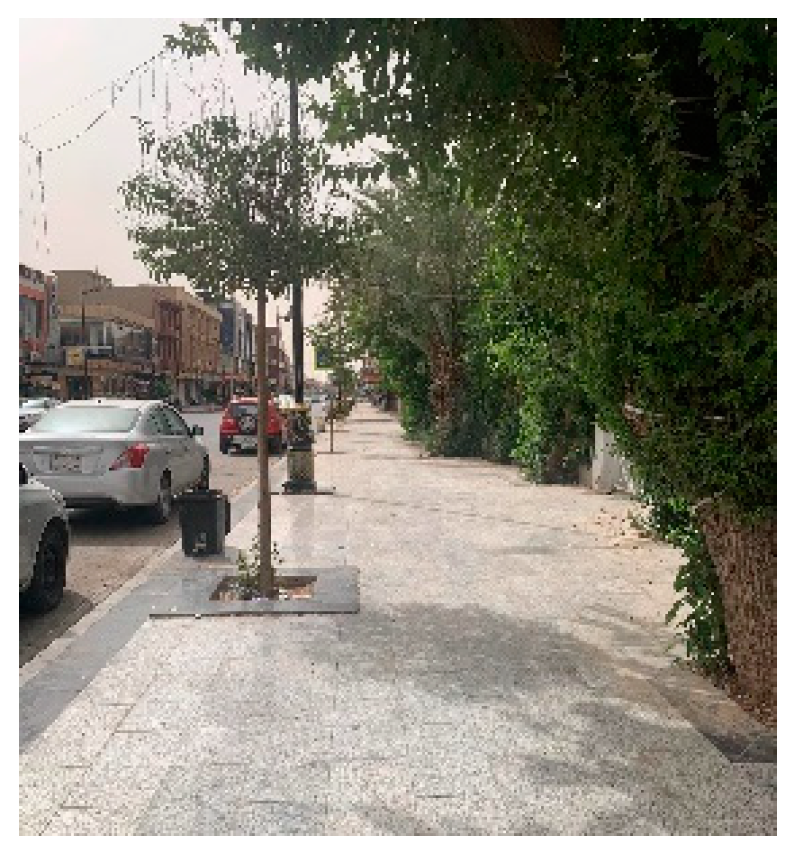

- The percentage of vegetation cover was limited as well as the number of trees, except for the afforestation on the right side of the street, due to the presence of a garden that covers approximately (6,592) m2, which works as a café and sitting area, Figure 27.

- Number of trees is very limited; most are not maintained. The approximate number of trees in the whole street is (40) only, Figure 28. The garden is occupied by many trees, Figure 29. It is important to give more attention to trees as they protect pedestrians from the sun, soften the weather, and give an aesthetic and attractive image to the commercial street.

- The general line of the building’s facades and within the perspective of the street was somewhat proportional and uniform in height. Most of the buildings were two floors high, except for a few buildings that exceeded three, and one of the buildings reached (8) floors. Figure 30.

3.1.3. Imageability

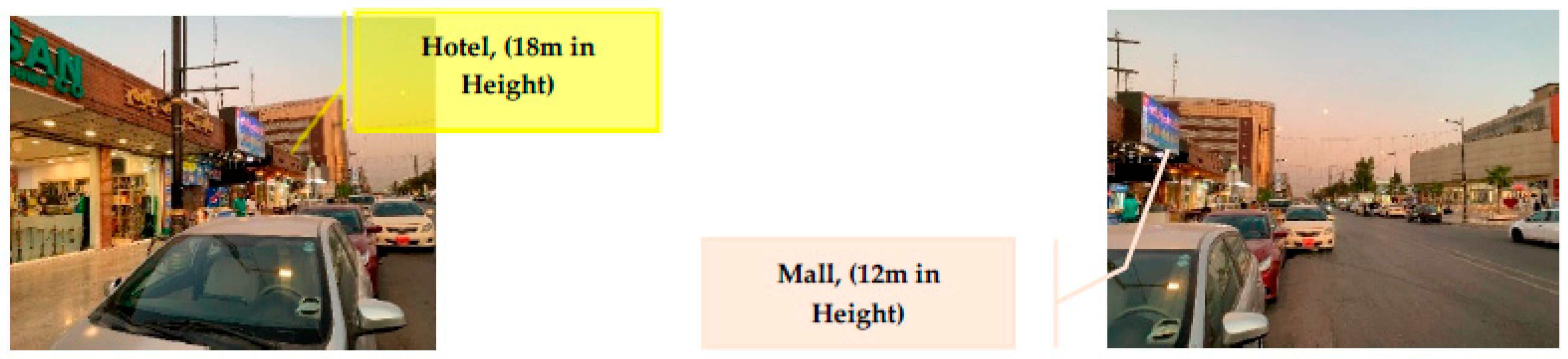

- Among the important things that define the street and distinguish it from others are points of attraction and the well-known buildings in it. Better to define a street with buildings, either of a different height or functions or even an architectural style. Two buildings were the identification for Eskan street in general, both were from the (30m) street side, Figure 31.

- Short poles were observed in some parts, serving as an edge demarcating sidewalk from the street and car overtaking. These columns are very important in terms of providing safety.

- Within the Furnishing zone, there were electricity poles, trees, billboards, and trash bins. These elements define the edge, preventing cars from overtaking, and forming a clear visual axis for the street and the sidewalks on both sides, Figure 32.

- Although sidewalks were suitable for the movement of people, the shop owners took advantage of them to display their goods, sell food and juices, or put chairs that belongs to the restaurant.

- Some buildings and restaurants took advantage of the frontage zone to add structural elements such as some levels and a few steps for entry. These elements were considered an obstacle to the movement of people, and in some places, people were forced to go down to the street to continue their movement and expose themselves to confrontation with cars, Figure 33.

- One of the positive and negative points at the same time is the availability of sitting places on some parts of sidewalks, but they belong to the private property of restaurants and cafe owners, and passers-by cannot use them. The street is devoid of public seating. Furniture and its availability on the sidewalks and the street provide comfort for pedestrians, Figure 34.

- Although trees are limited, they provide shade and enrich the visual aesthetics of this part of the street. The differences are clear between parts with trees and parts without, Figure 35.

- One of the pedestrian attractions on the commercial street is the transparency of shop fronts. The problem is that most of the shops on Eskan street are restaurants and cafeterias, and some others are various shops. Many restaurants relied on using sidewalks as sitting places, while shop owners used sidewalks to display their goods. The interface has almost disappeared except for a few of them.

- For other shops the fronts were completely transparent, showing what is inside, this raised the visual connection between pedestrians and shops. at night This sensory connection and visual transparency increased due to lighting. Figure 36.

- Sidewalks show a clear visual connection, uniform tiling materials, and limited obstacles within the pedestrian zone. This visual connection had an impact on many levels, including giving a unified character to sidewalks, encouraging walking, feeling comfortable when moving, and presenting a beautiful street image, Figure 37.

- Some uses of street furniture and Tree planting boxes positively attracted people to sit and enjoy with friends and created an interactive atmosphere, especially since the space in front of the mall was spacious and could hold many activities, Figure 38.

- One of the points that negatively affect the aesthetic image of the street is the weakness of cleaning and maintenance for the street, its furniture, and lighting. Cleanliness is very important in attracting people and the constant desire to return and use it. In general, there is interest in cleanliness, but not at high levels, Figure 39.

- The street did not include standardization in architectural styles, elements, and forms designs were individual and did not follow general frameworks. One of the positive points is that some restaurant owners use traditional materials such as bricks, which add a local character to the facades. Figure 40.

3.2. Practical Framework and Questianeer Results

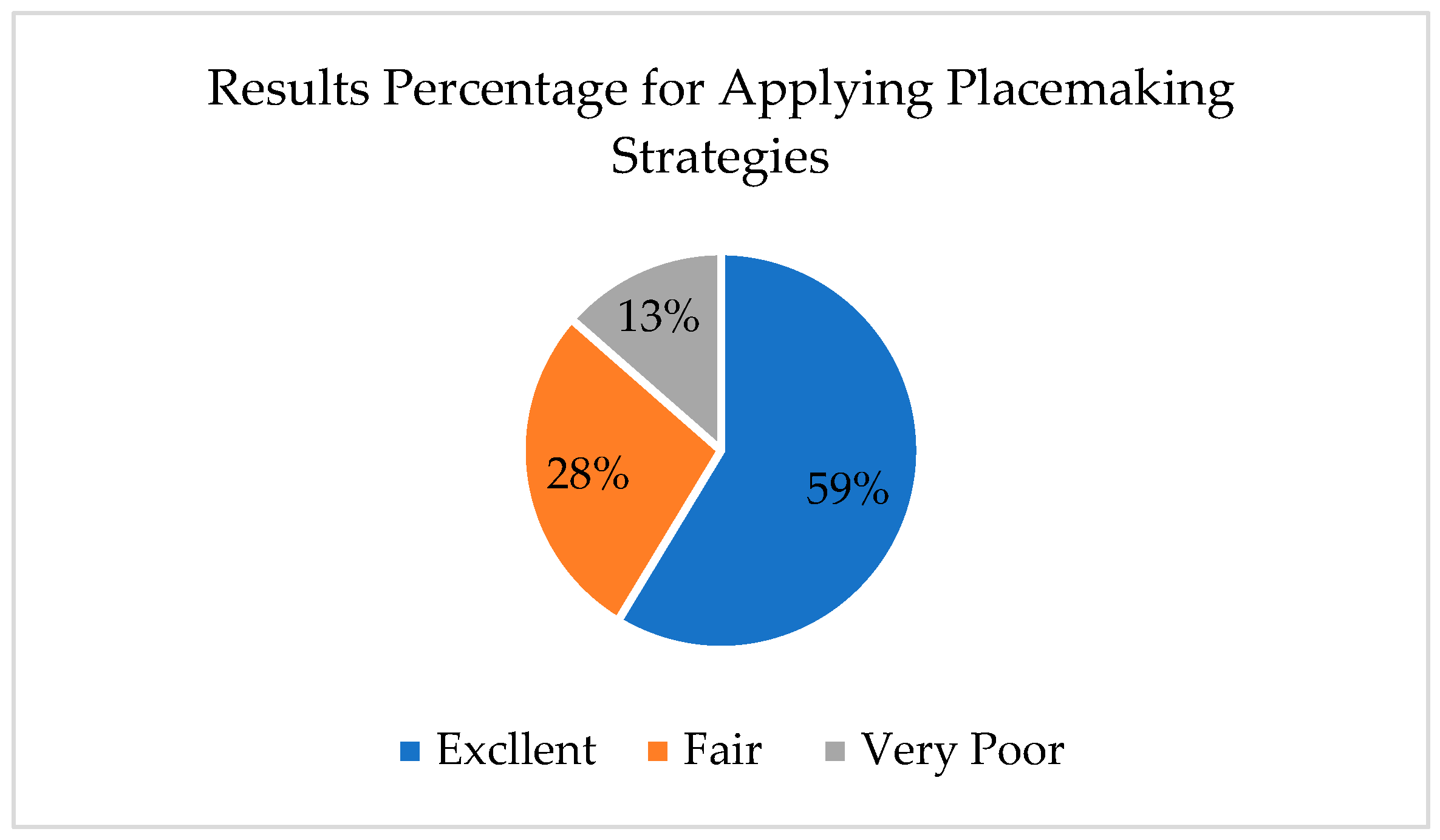

3.2.1. Practical Framework Results

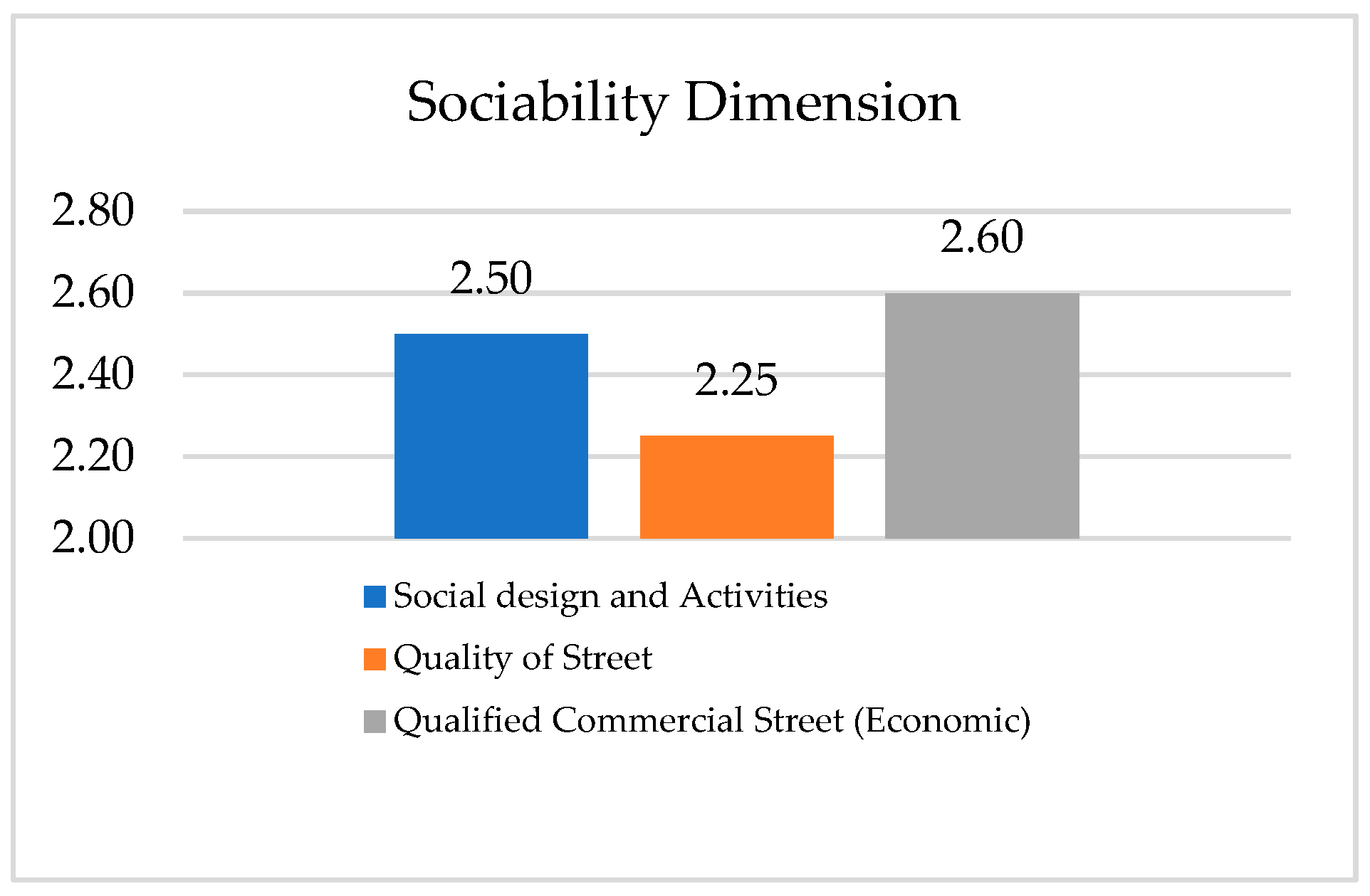

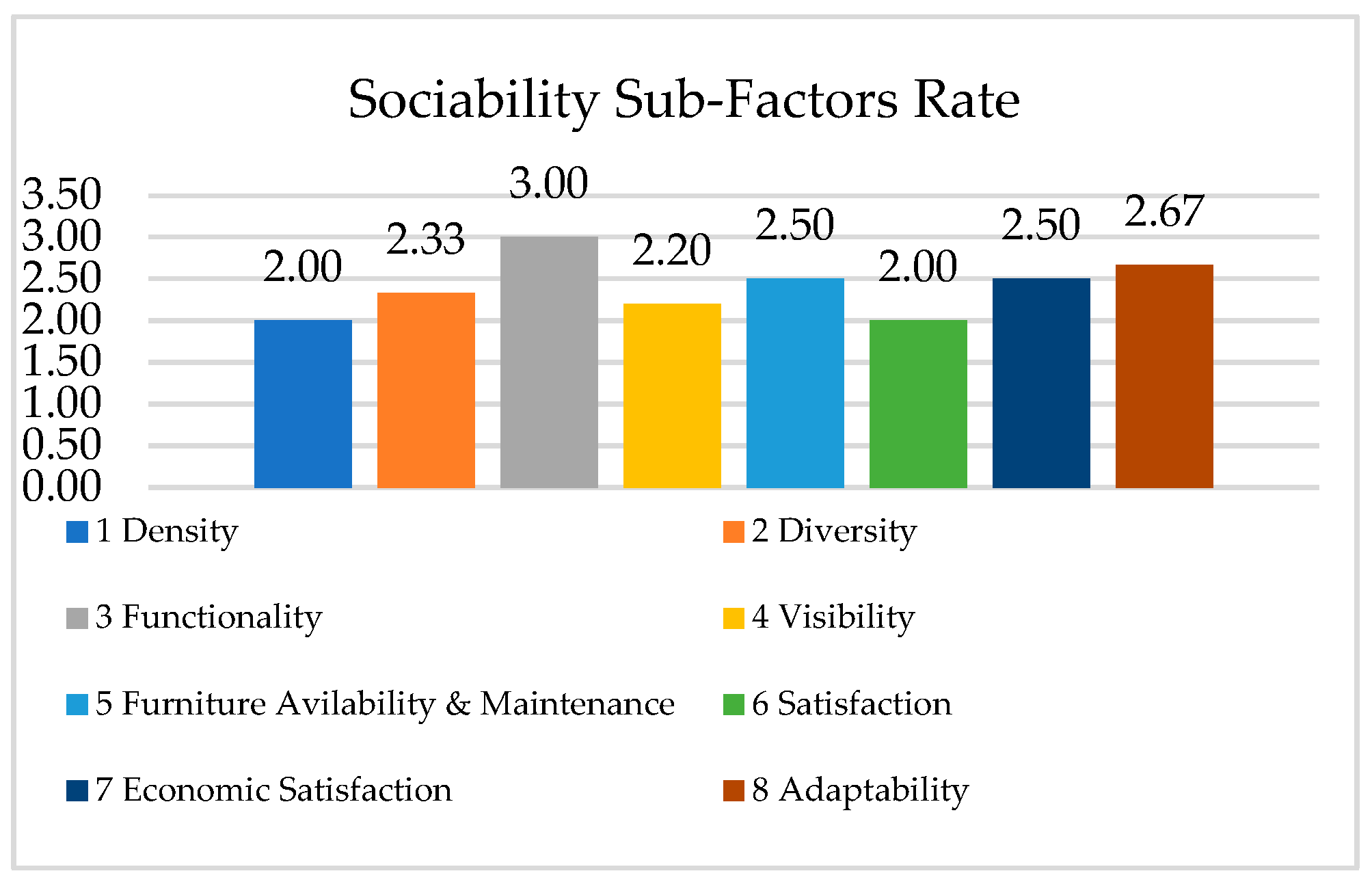

3.2.1.1. Sociability Results

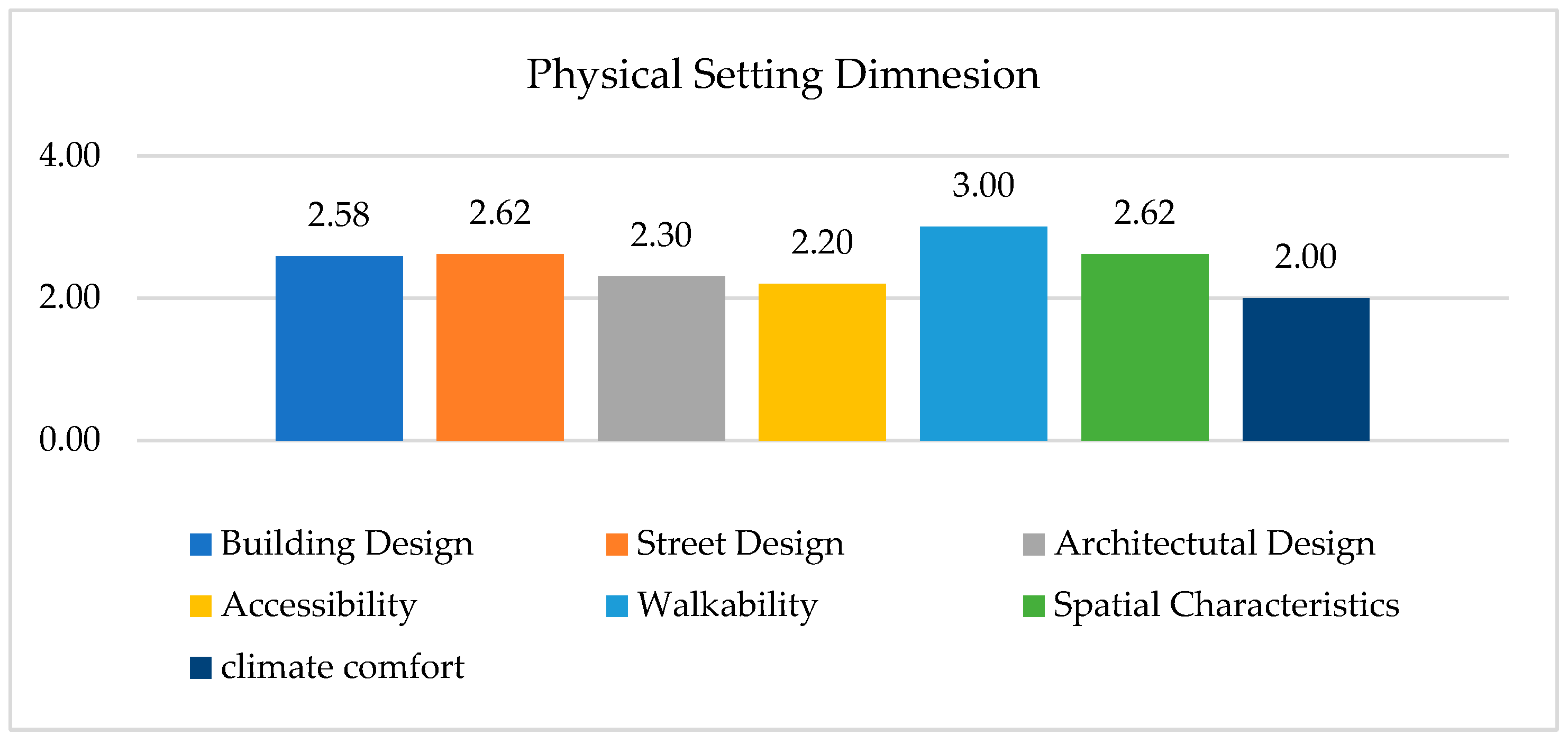

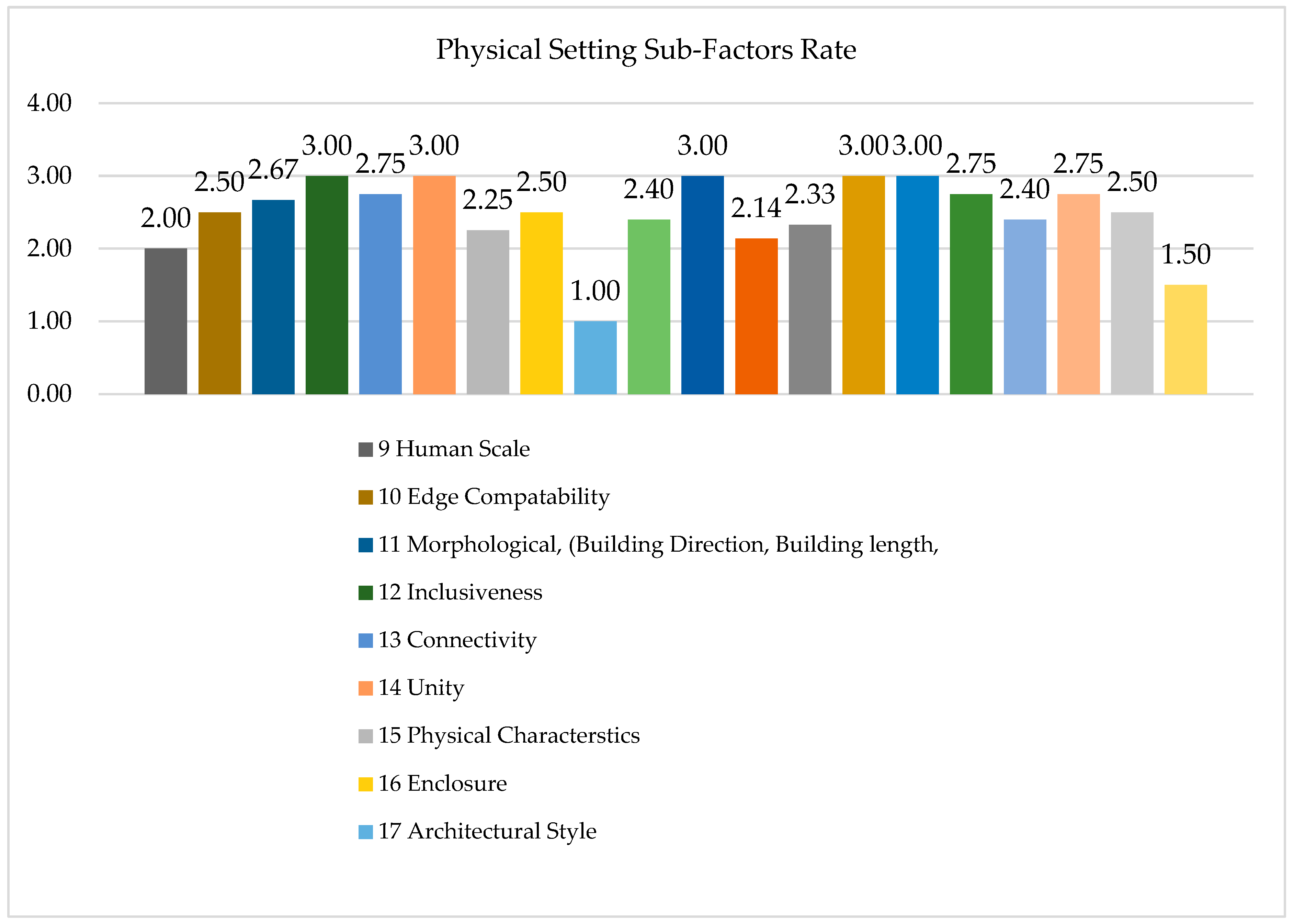

3.2.1.2. Physical Setting Results

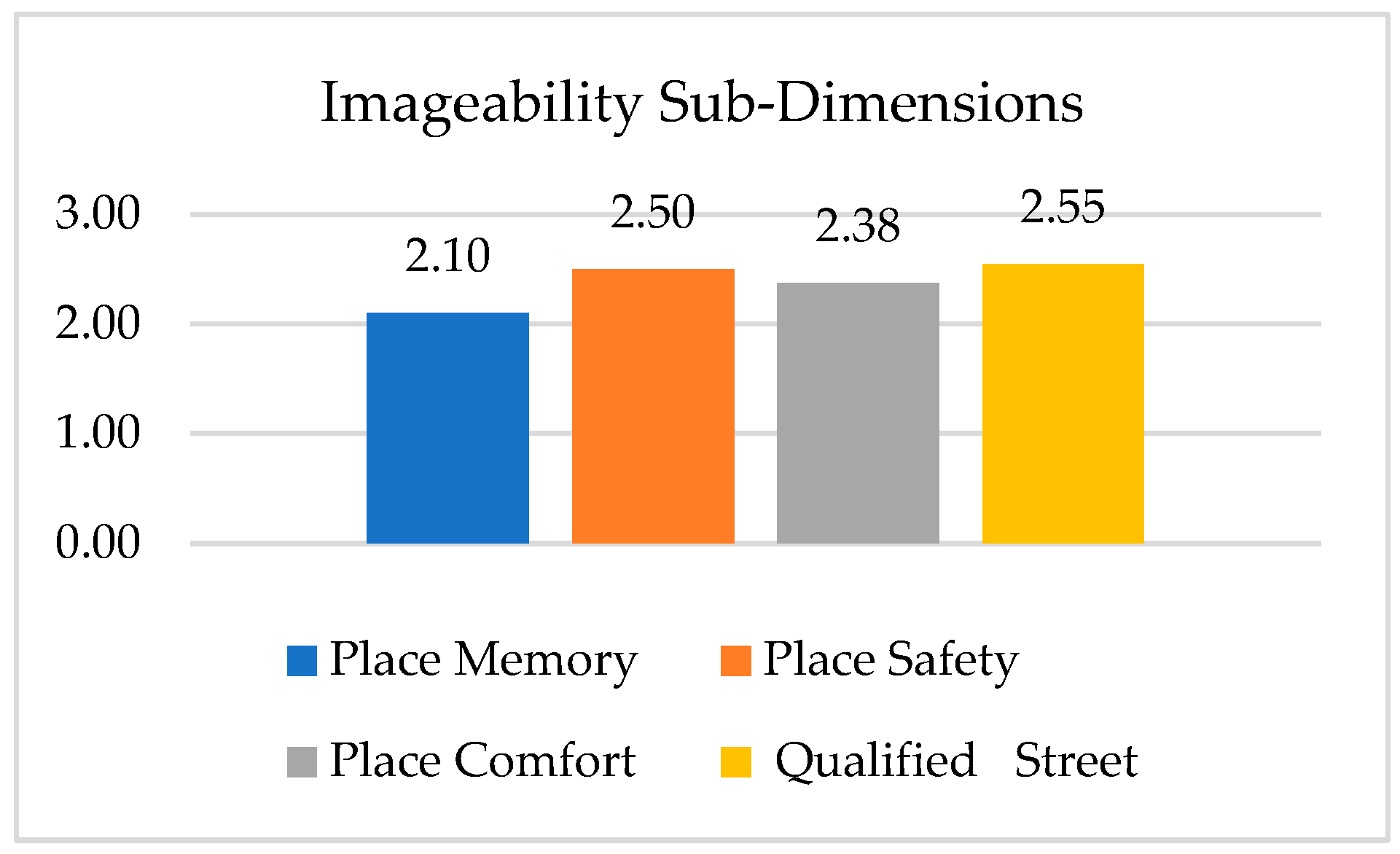

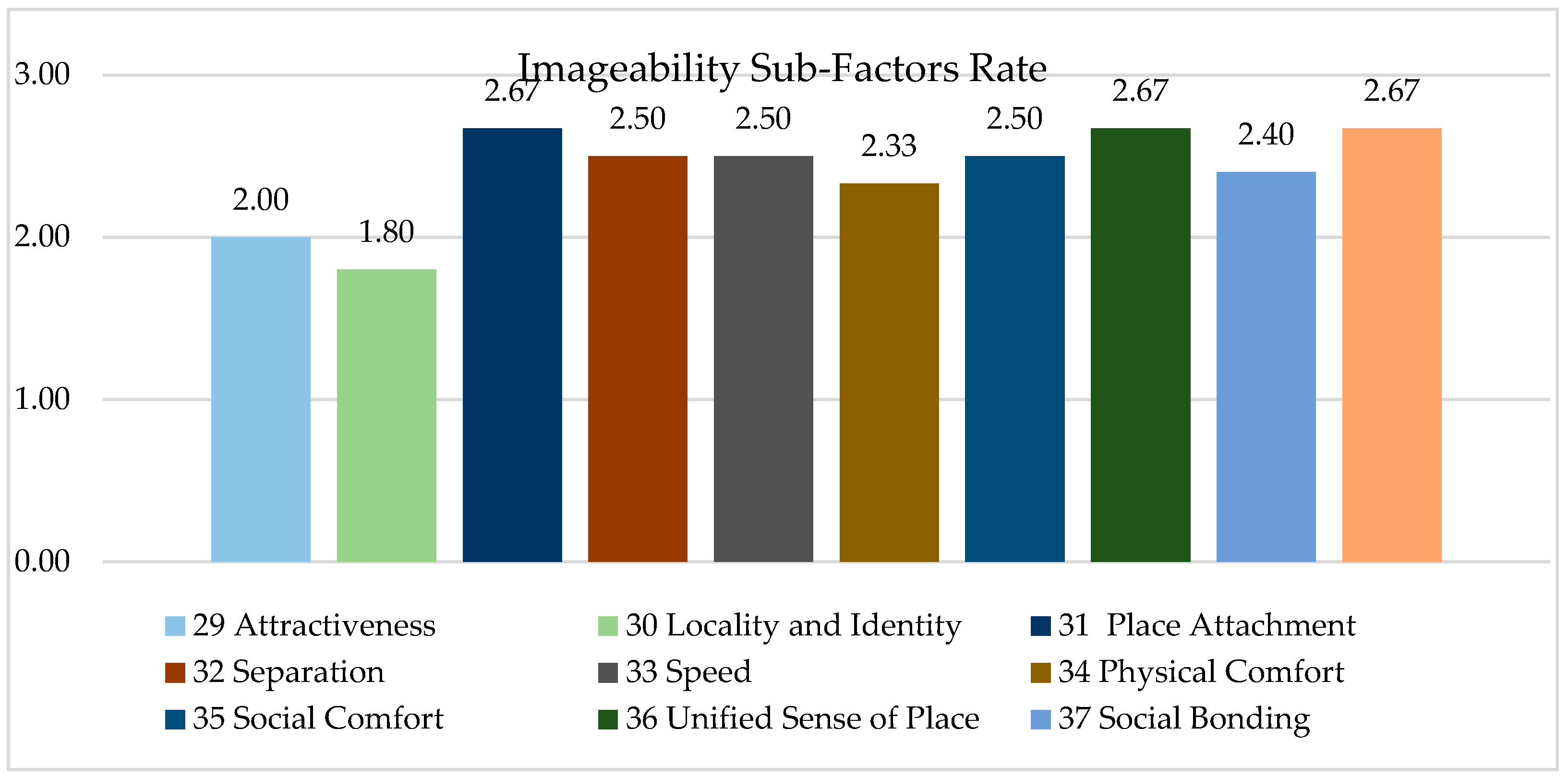

3.2.1.3. Imageability Results

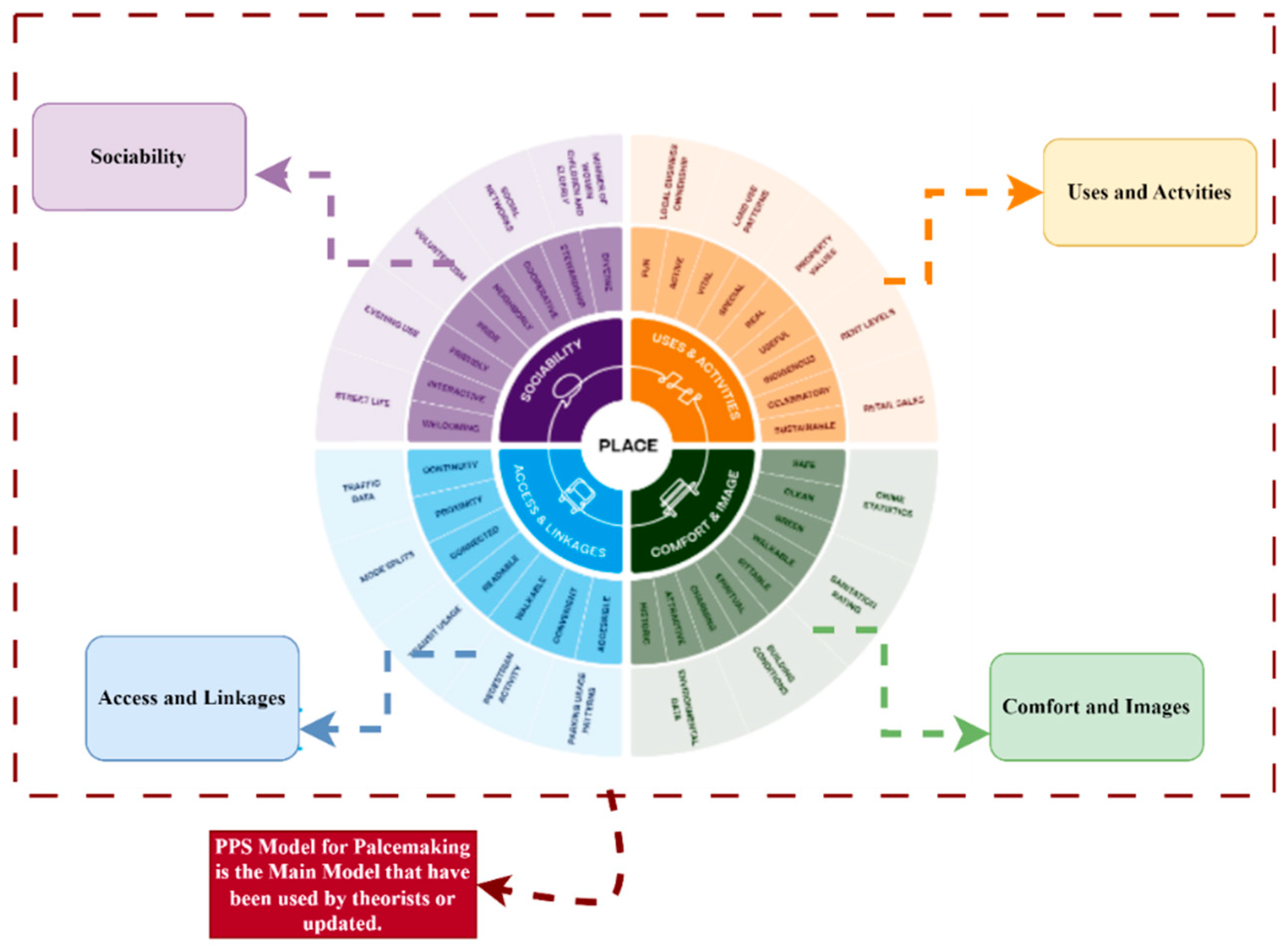

3.2.2. Questionnaire Results

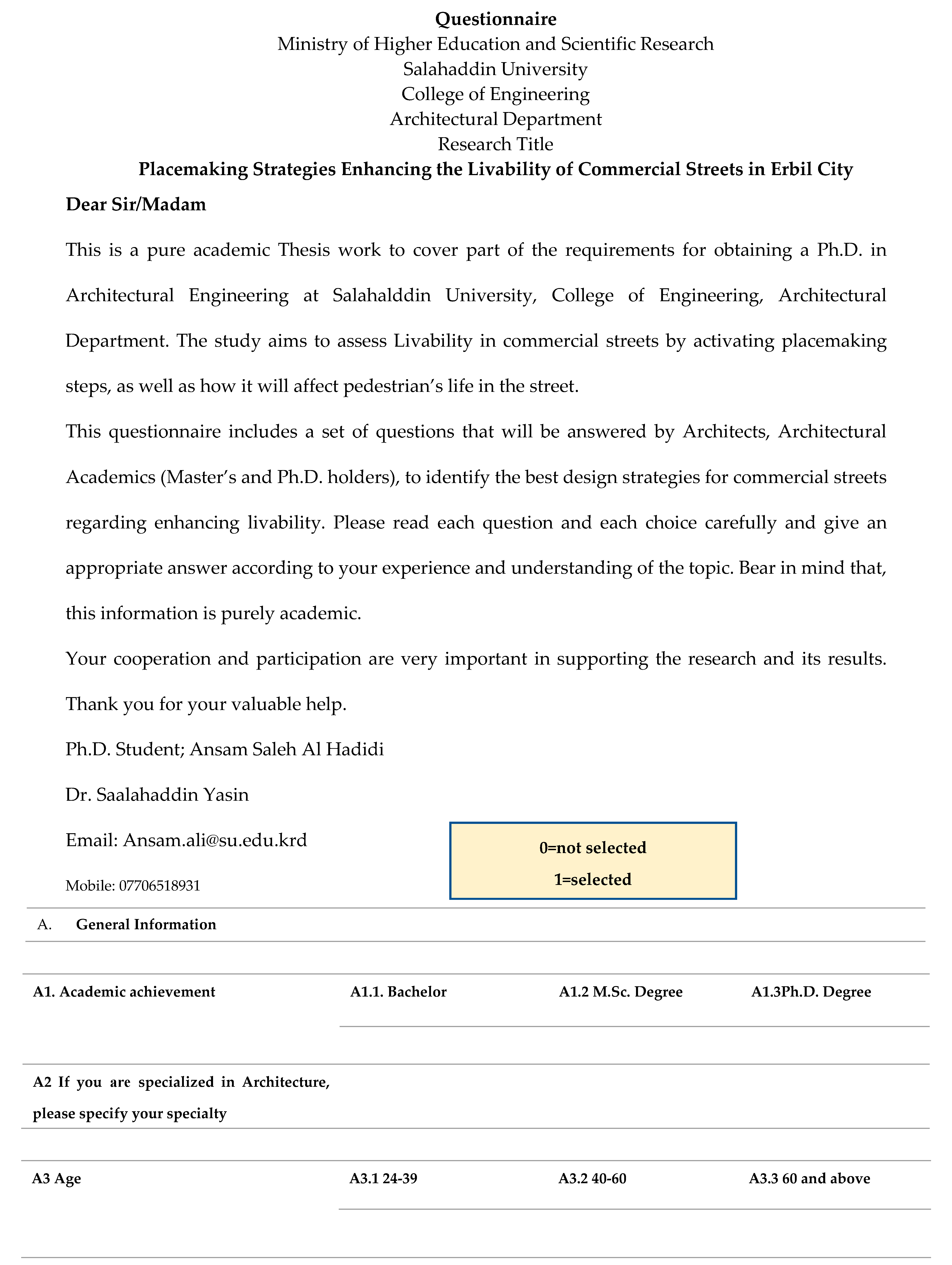

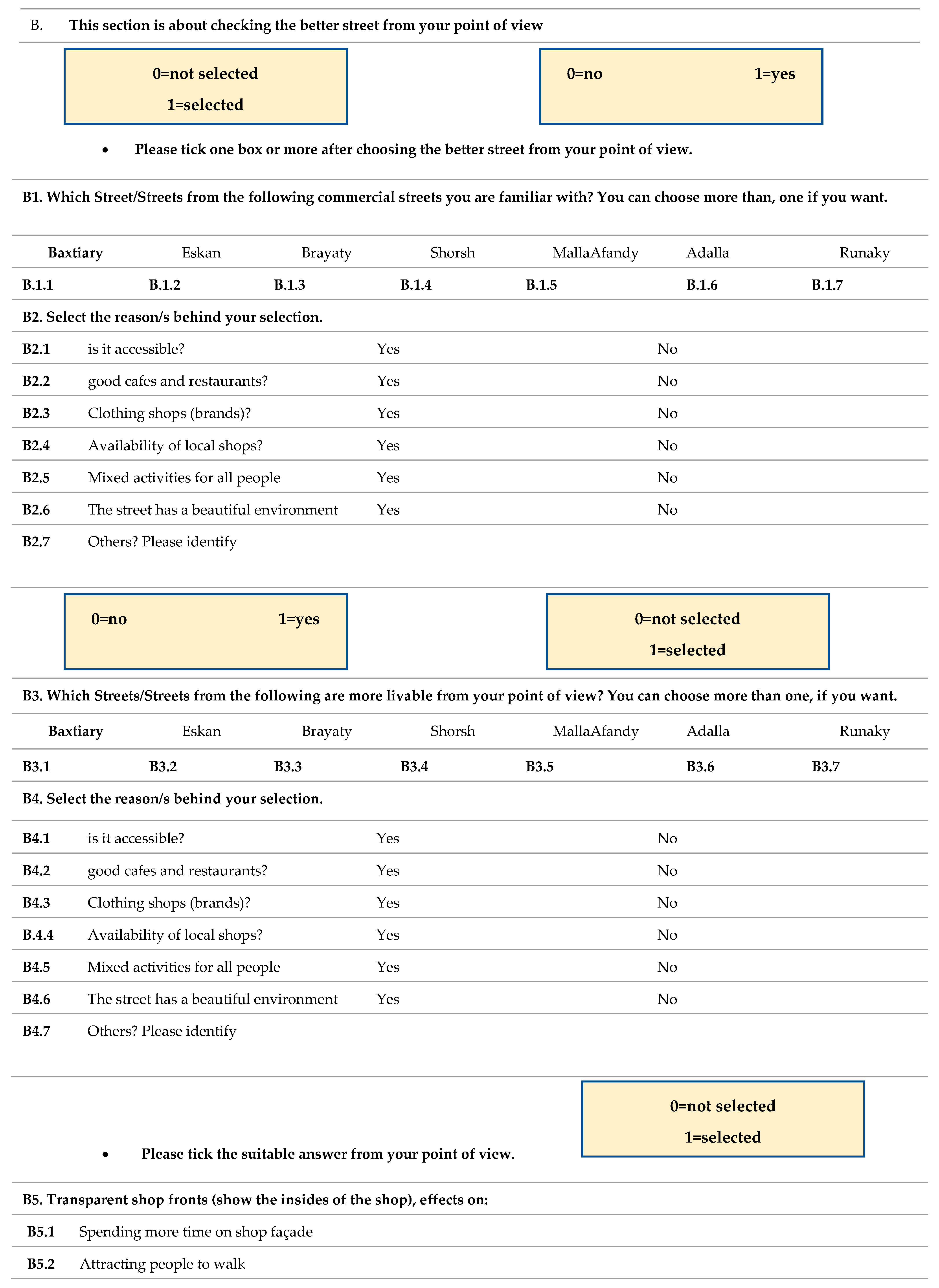

- The questionnaire was directed to architects and urban designers as the research aims to reach systematic strategies and detailed steps for placemaking.

- (100) lists were distributed to architects, only (62) were received, (and 7) contained inconsistent answers (where the researchers added six pairs of verification questions if the answers were different for more than three pairs, the questionnaire will be canceled).

- The Questionnaire consisted of two main parts. The first presents a group of general questions about age and architectural specialization, as well as their opinion on a comparison between seven commercial streets.

- The second part included two main aspects of the research, the placemaking (which included questions regarding the three basic pillars identified by the research, physical setting, sociability, and imageability), as well as questions related to livability, Appendix (C), shows the Questionnaire list.

- The questionnaire list was created in the same way as the basic components of the checklist (the practical framework), and with the same approach, as well as the outputs of the field survey, in sequence, conforming to the dimensions and basic factors.

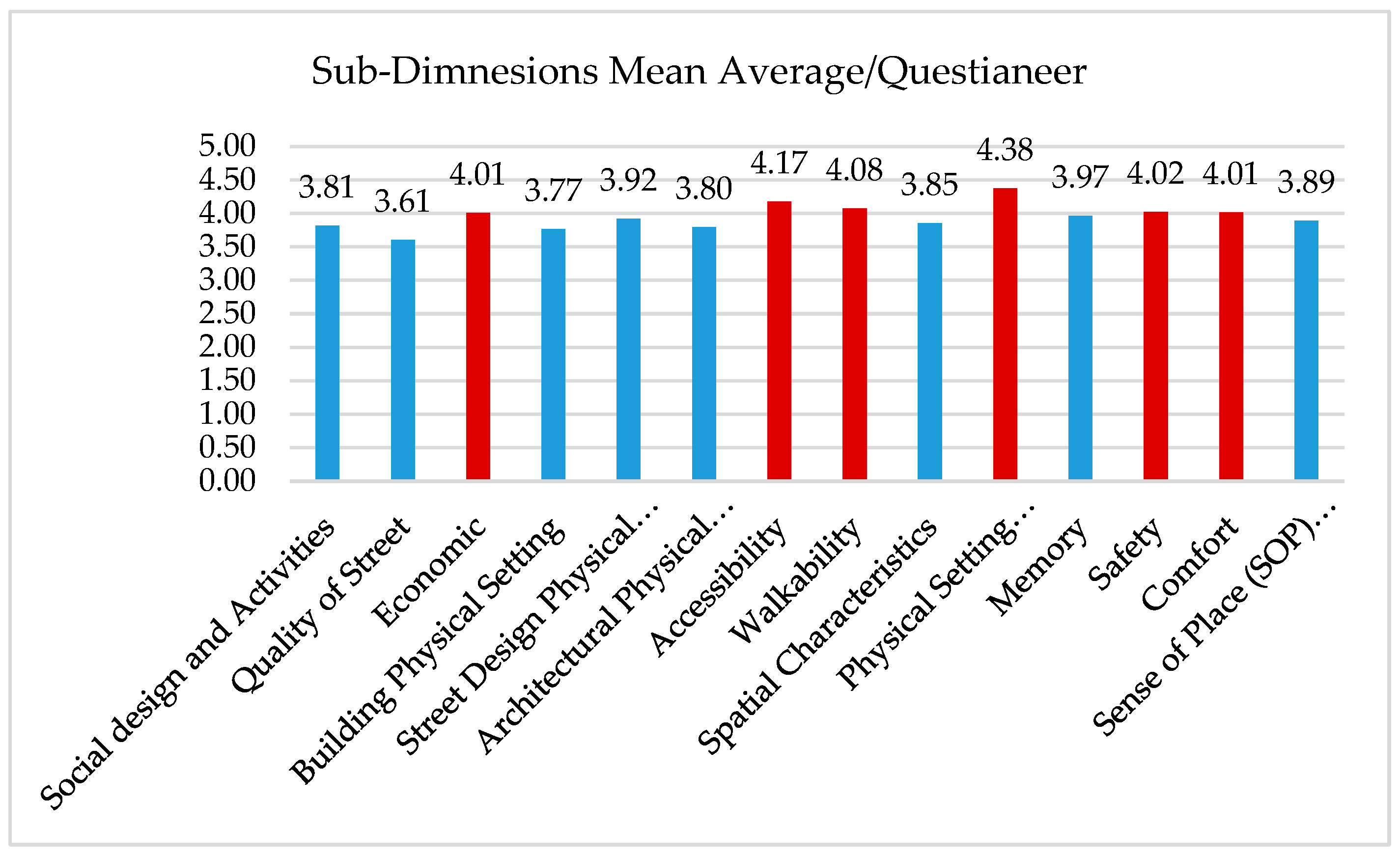

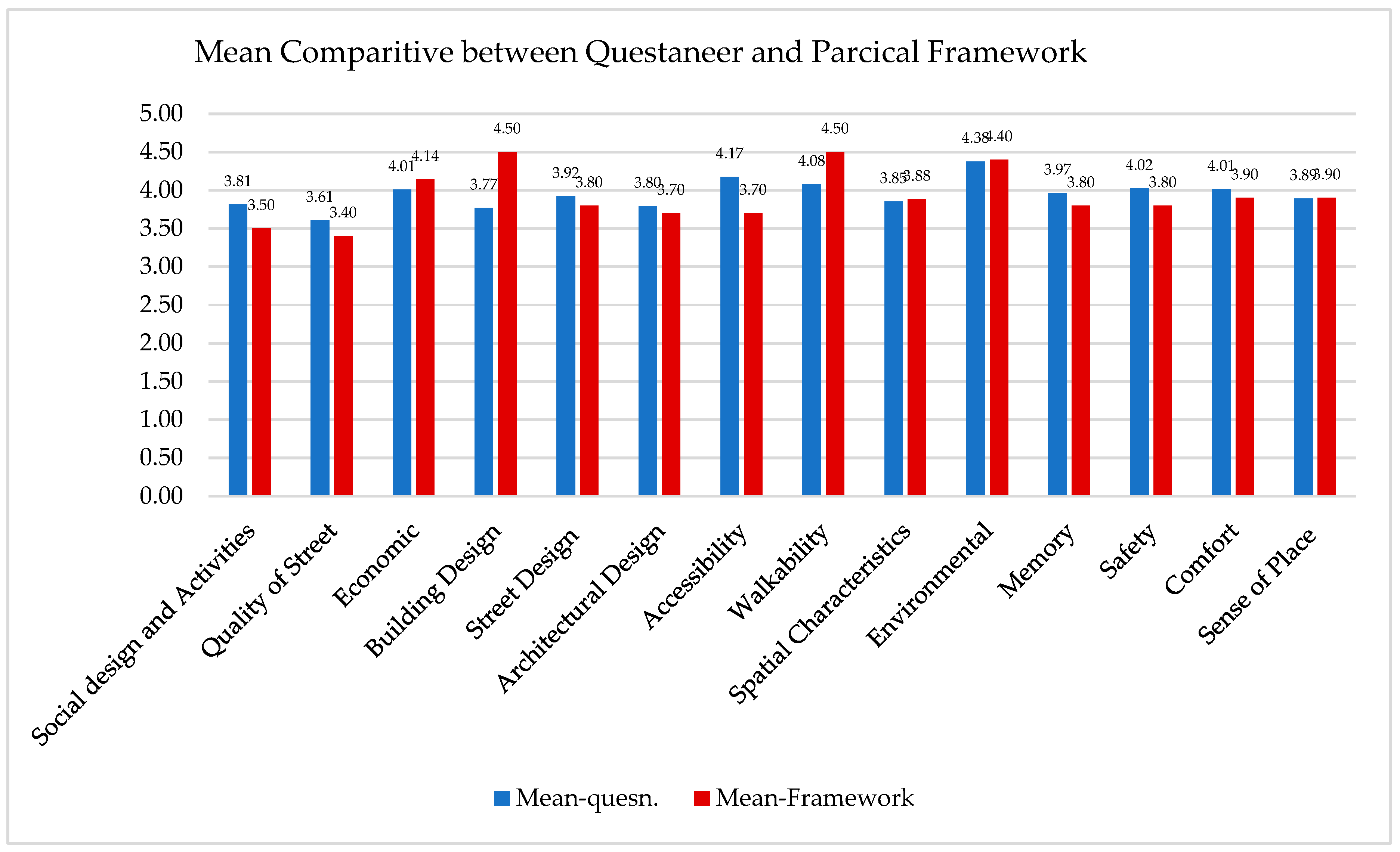

- The research took this format to easily compare both approaches. By comparing the averages of the results of the questionnaire regarding main and secondary dimensions, and factors, the most influencing dimensions are comfort and safety, along with the economic factor, accessibility, and walkability. Figure 47, Each of the physical dimensions of the street in terms of sidewalks width and the availability of furniture, activities, and their diversity, and the formation of a beautiful image, were among the most influential that came in second place. These are regarded as the most important steps in activating livability.

- Among the important things that the research noticed, which appeared more clearly in the pilot study, people were asked about the reason for choosing this commercial street, and the reasons as mentioned previously in this research, land use diversity, variety of restaurants, and plenty of cafeterias, being a comfortable street as the car movement is limited, in addition to the existence of a mall on the street which contains many activities, services, and various shops, in addition to entertainment services for children.

- Females’ participant showed their desire to roam the street which is not totally possible to use by women at all times, as it is considered a (male street) more than a female one (although there is no objection to using the female gender), since the quality of food in restaurants and cafeterias and the gathering of young people, especially in soccer watch periods.

- Therefore, this point must be taken into consideration when aiming to develop the street, as most women want to use the street. It is noted that there are a large number of women users of the mall more than men and at different times.

- The first is to compare the secondary dimensions to find out the differences between the two sides and the importance according to the different points of view.

- The second was at the level of comparison of the three basic dimensions.

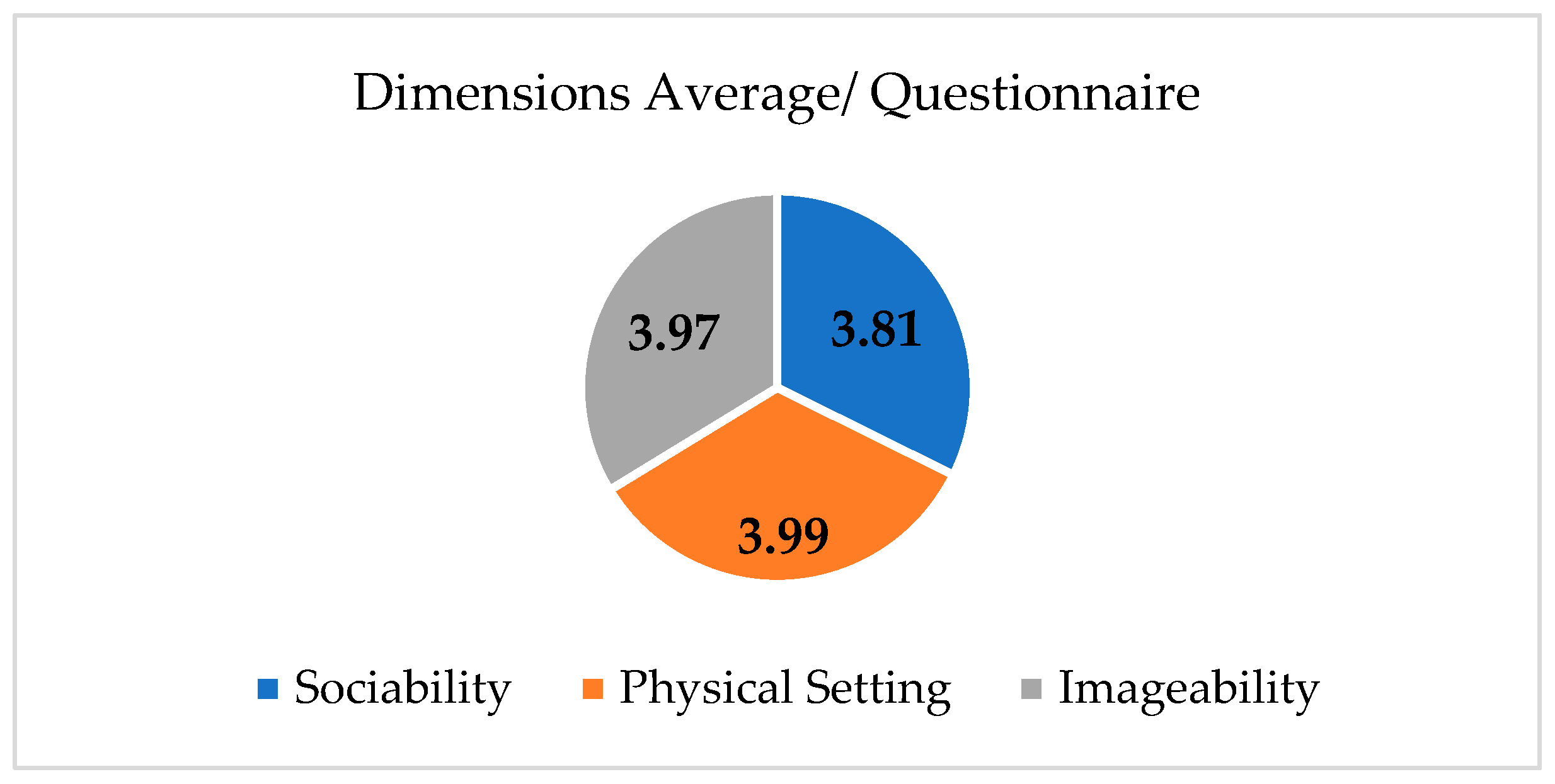

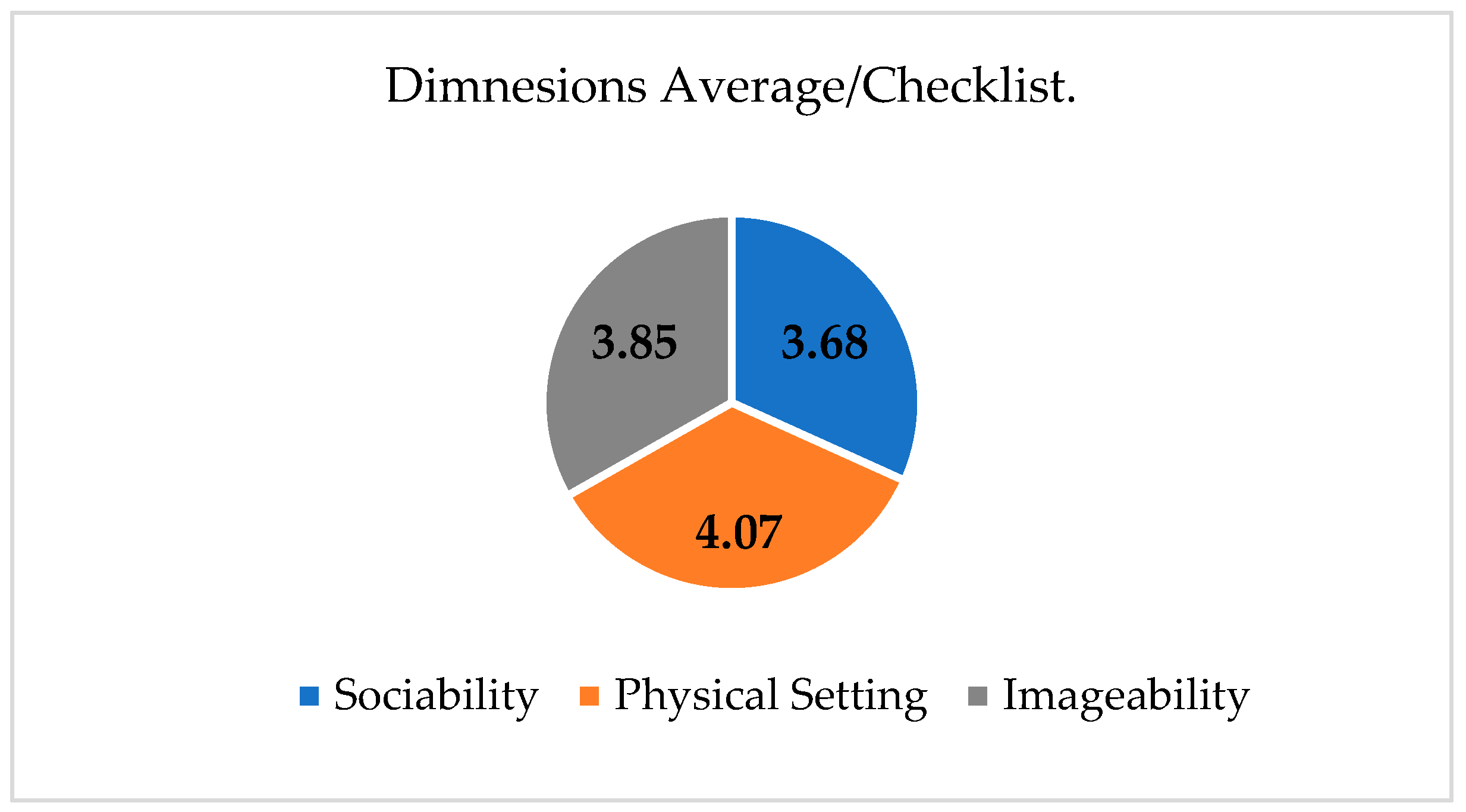

- And by comparing the averages and despite the close consistency between the results, it is clear that the physical aspect was the highest among the group in both methods, with (3.99) and (4.07) for the questionnaire and the practical framework, followed by the imageability aspect by (3.97) and (3.85).

- And the last dimension in the ranking is for the sociability dimension of (3.81) and (3.50).

| Sub-Dimensions | Mean-questionnaire. | Dimensions | Dimensions Percentage | Mean-Checklist | Dimensions | Dimensions Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social design and Activities | 3.81 | Sociability | 3.81 | 3.50 | Sociability | 3.68 |

| Quality of Street | 3.61 | 3.40 | ||||

| Economic | 4.01 | 4.14 | ||||

| Building Design | 3.77 | Physical Setting | 3.99 | 4.50 | Physical Setting | 4.07 |

| Street Design | 3.92 | 3.80 | ||||

| Architectural Design | 3.80 | 3.70 | ||||

| Accessibility | 4.17 | 3.70 | ||||

| Walkability | 4.08 | 4.50 | ||||

| Spatial Characteristics | 3.85 | 3.88 | ||||

| Environmental | 4.38 | 4.40 | ||||

| Memory | 3.97 | Imageability | 3.97 | 3.80 | Imageability | 3.85 |

| Safety | 4.02 | 3.80 | ||||

| Comfort | 4.01 | 3.90 | ||||

| Sense of Place | 3.89 | 3.90 |

3.3. Discussion and Conclusion

Appendix A

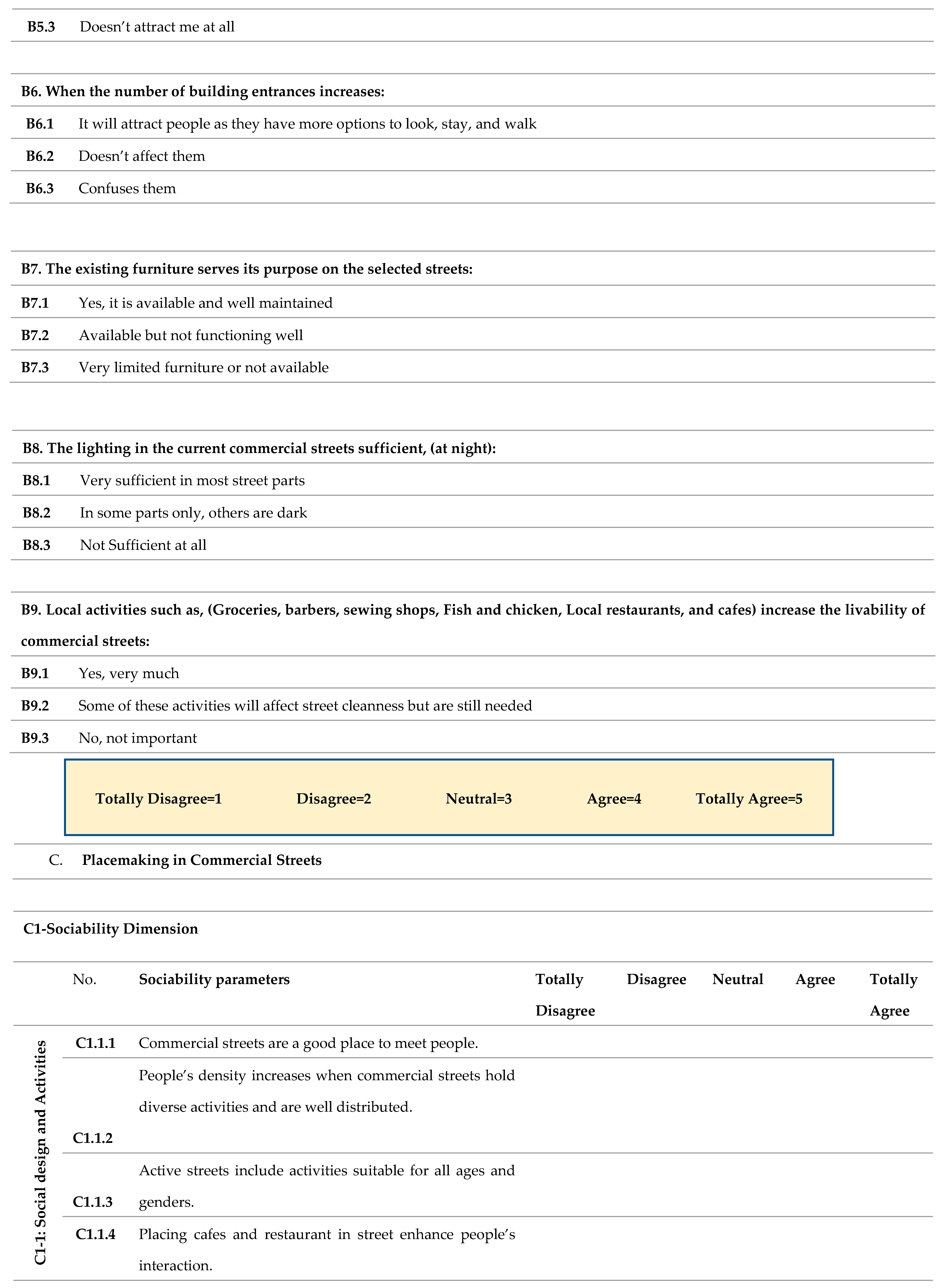

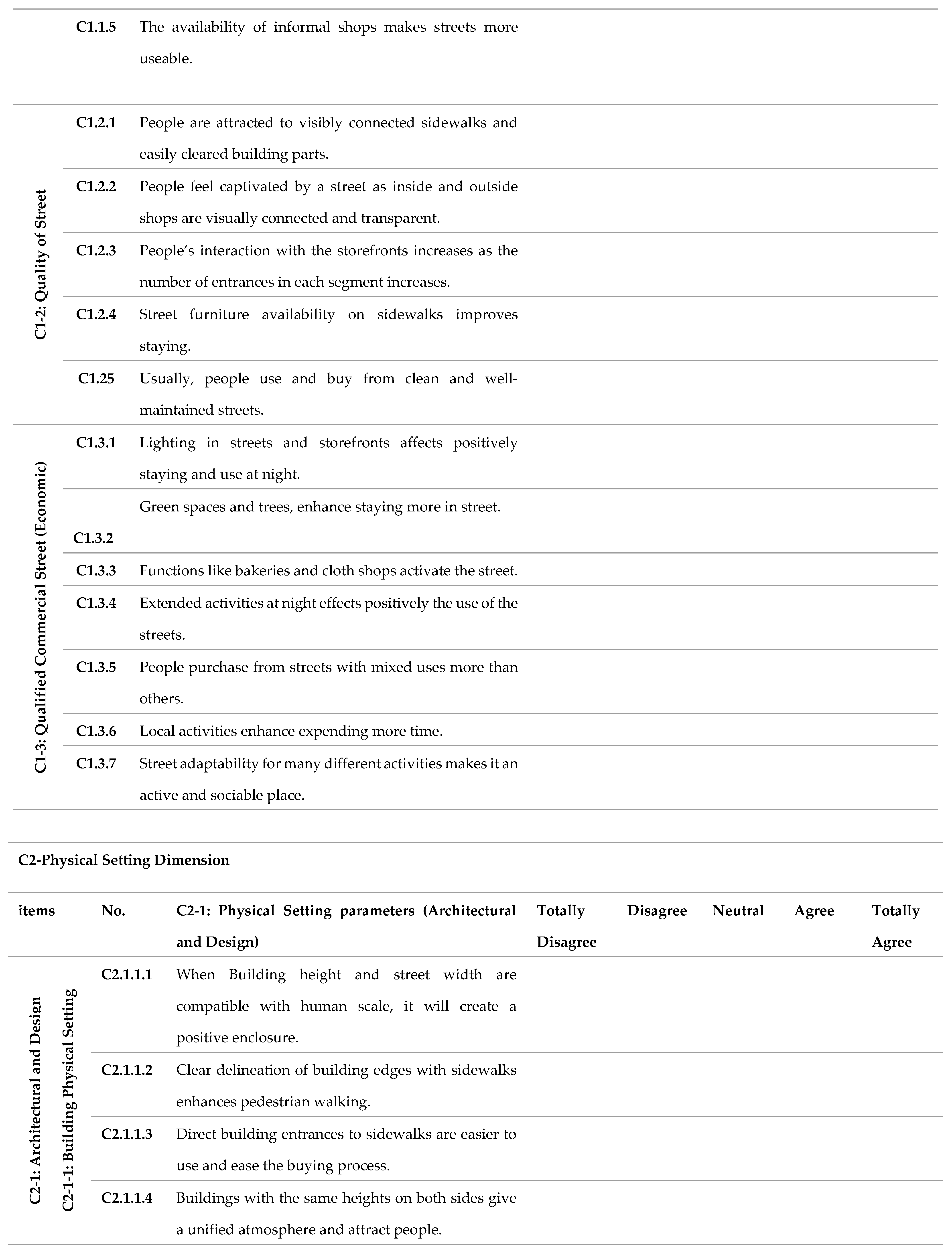

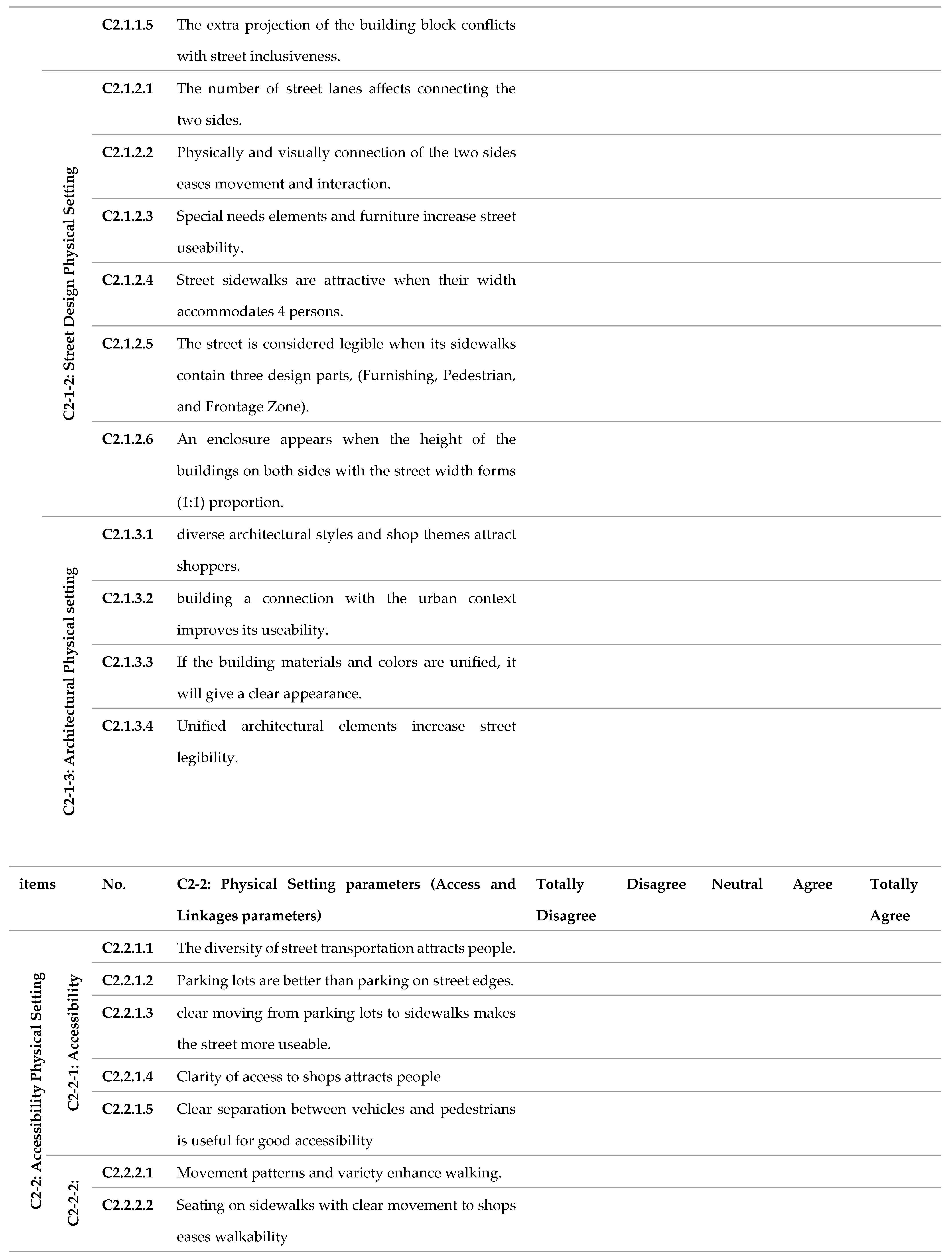

Appendix B

|

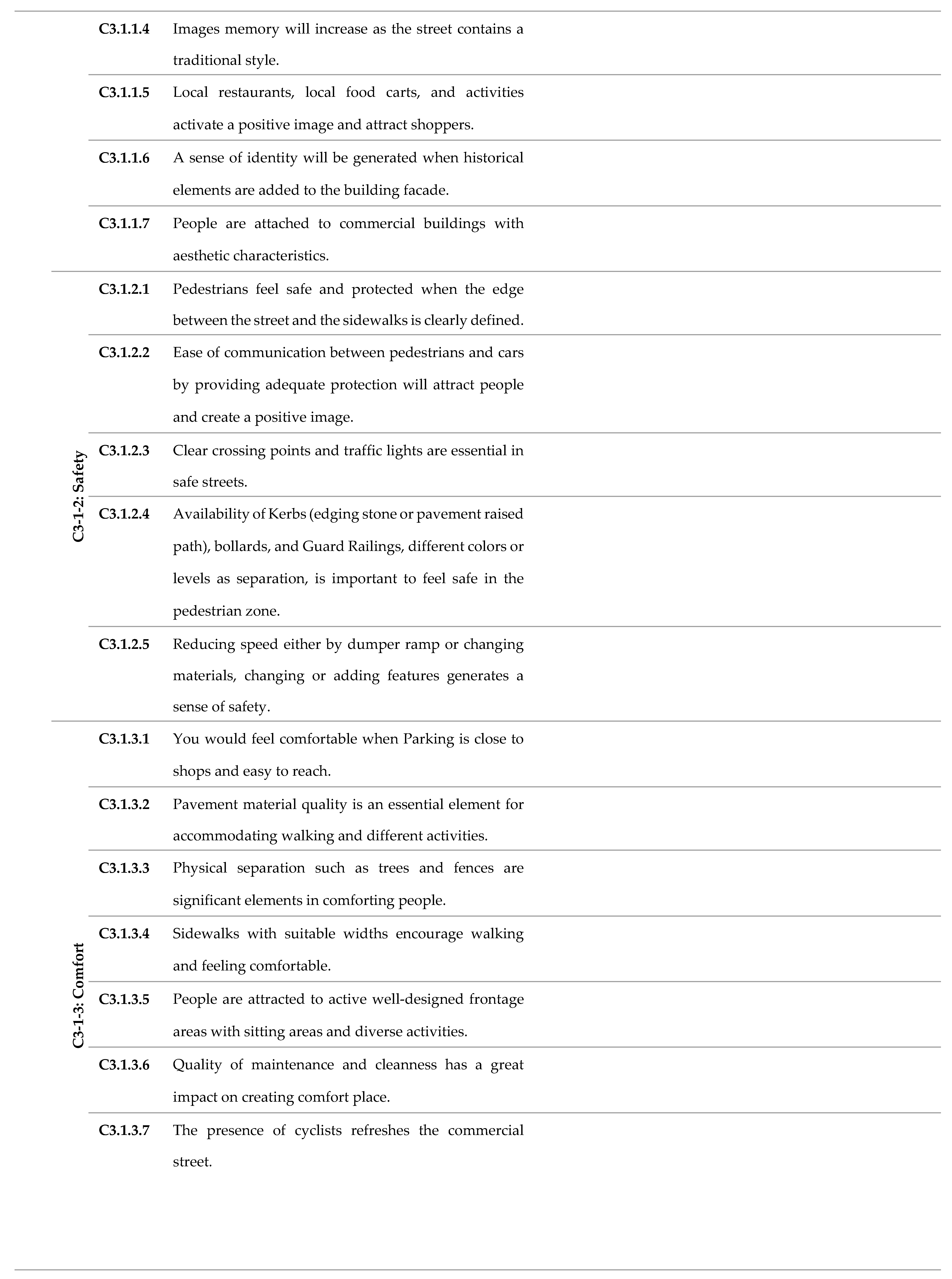

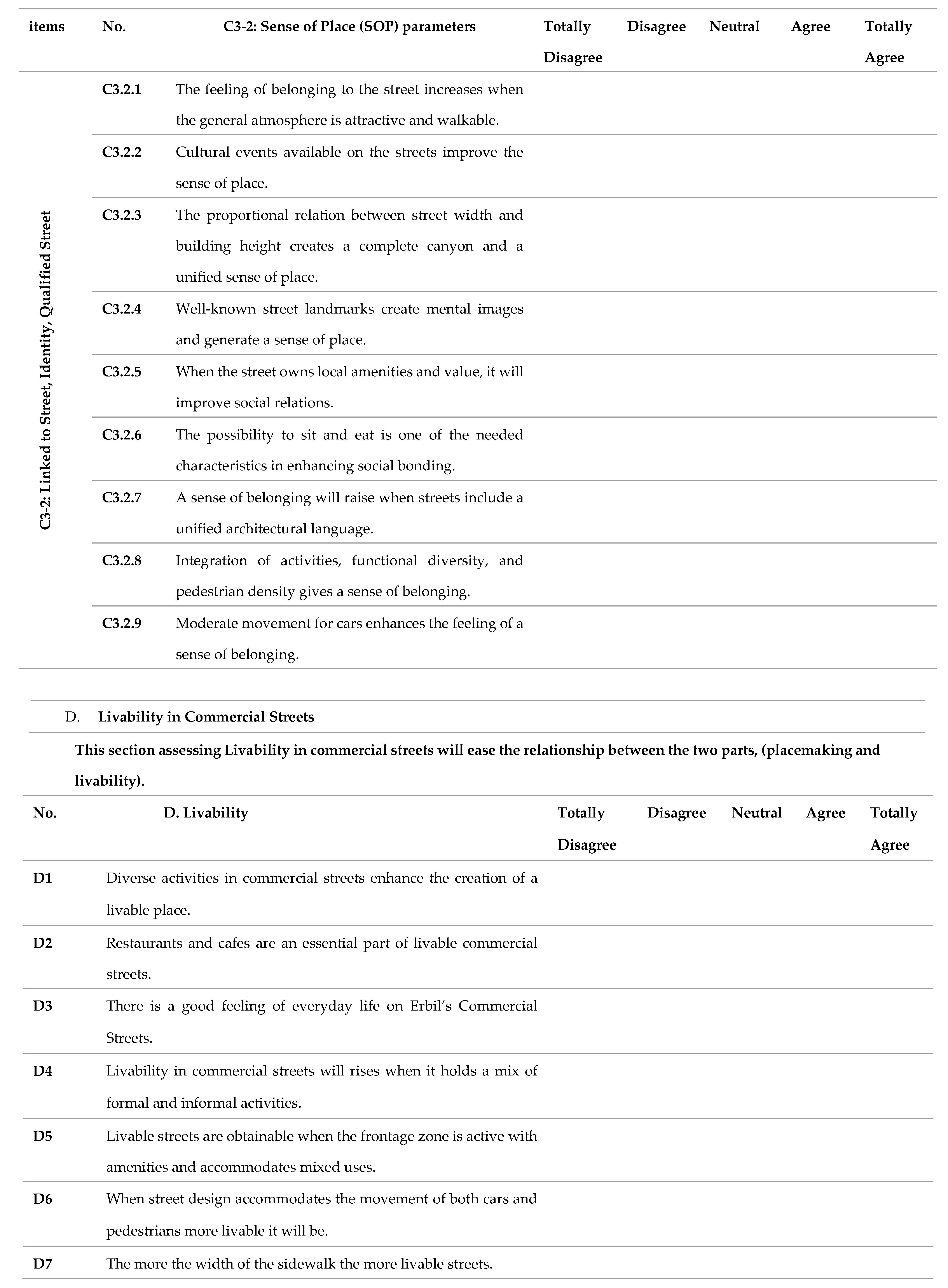

Appendix C

|

References

- N. A. Rahman, S. Shamsuddin, and I. Ghani, “What Makes People Use the Street?: Towards a Liveable Urban Environment in Kuala Lumpur City Centre,” Procedia Soc Behav Sci, vol. 170, 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Appleyard, “Livable streets: protected neighborhoods,” Ekistics, vol. 45, no. 273, pp. 412–417, Dec. 2016, Accessed: Feb. 21, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.orgURL:http://www.jstor.org/stable/.

- A. Jacobs and D. Appleyard, “Toward an urban design manifesto,” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 112–120, 1987. [CrossRef]

- K. Marthya, R. Furlan, L. Ellath, M. Esmat, and R. Al-Matwi, “Place-making of transit towns in Qatar: The case of qatar national museum-souq waqif corridor,” Designs (Basel), vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Joan Clos, The city at eye level: lessons for street plinths. 2016. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://thecityateyelevel.com/app/uploads/2018/06/eBook_The.City_.at_.Eye_.Level_English.pdf.

- J. Gehl, Cities for People. Washington, ISLAND PRES, 2010. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://umranica.wikido.xyz/repo/7/75/Cities_For_People_-_Jan_Gehl.pdf.

- Fred Kent, “Project of Public Spaces (PPS),” https://www.pps.org/category/placemaking, 2020. INQUIRIES@PPS.ORG OR 212.620.5660.

- J. Jacobs, The DEATH and LIFE of GREAT AMERICAN CITIES, 1st Vintage Books. New York: Urban renewal-—United States.3. Urban policy—United States I. TitleHT167.J33 1992, 1961. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.buurtwijs.nl/sites/default/files/buurtwijs/bestanden/jane_jacobs_the_death_and_life_of_great_american.pdf.

- non-profit foundation, “Placemaking Week Europe,” Sep. 27, 2022. https://placemaking-europe.eu/ (accessed Feb. 07, 2023).

- Rita Nohra and Chirine Salha, “Placemaking: Putting life and soul into neighborhood spaces,” Hospitality news Middle East, Jul. 02, 2018. https://www.hospitalitynewsmag.com/placemaking-putting-life-and-soul-into-neighborhood-spaces/ (accessed Feb. 07, 2023).

- A. M. R. M. Mohamed, S. Samarghandi, H. Samir, and M. F. M. Mohammed, “The role of placemaking approach in revitalising AL-ULA heritage site: Linkage and access as key factors,” International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 921–926, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- North Norfolk District Council., “https://designguide.north-norfolk.gov.uk/getting-started/the-value-of-placemaking/,” www.north-norfolk.gov.uk, 2023. https://designguide.north-norfolk.gov.uk/getting-started/the-value-of-placemaking/ (accessed Feb. 08, 2023).

- A. Santos Nouri and J. P. Costa, “Placemaking and climate change adaptation: new qualitative and quantitative considerations for the ‘Place Diagram,’” J Urban, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 356–382, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Ellery, J. Ellery, and M. Borkowsky, “Toward a Theoretical Understanding of Placemaking,” International Journal of Community Well-Being, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 55–76, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Ghavampour and B. Vale, “Revisiting the ‘model of place’: A comparative study of placemaking and sustainability,” Urban Plan, vol. 4, no. 2 Public Space in the New Urban Agenda: Research into Implementation, pp. 196–206, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jack Backen, “THE VALUE OF PLACEMAKING,” The City at Eye Level Asia, Nov. 04, 2020. https://thecityateyelevel.com/stories/the-value-of-placemaking/ (accessed Feb. 07, 2023).

- P. and U. D. Tribal and A. and U. D. O’ Mahony Pike, “Urban Design Manual A best practice guide A companion document to the Guidelines for Planning Authorities on Sustainable Residential Development in Urban Areas,” Ireland and across Europe, May 2009. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.opr.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1999-Urban-Design-Manual-1.pdf.

- K. Al-Kodmany, “High-Rise Buildings Placemaking in the High-Rise City: Architectural and Urban Design Analyses,” International Journal of High-Rise, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 153–169, 2013, [Online]. Available: www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php.

- National Associations of Realtors, “Placemaking: Big Impacts, Small Towns,” Jan. 13, 2020. https://www.nar.realtor/blogs/spaces-to-places/placemaking-big-impacts-small-towns (accessed Feb. 21, 2023).

- Aras an Chontae, “URBAN CENTRES & PLACEMAKING 7,” Mullingar, Mount Street. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://consult.westmeathcoco.ie/en/consultation/draft-westmeath-county-development-plan-2021-2027/chapter/07-urban-centres-and-place-making.

- Tim Cresswell, “Place: A Short Introduction,” 13th ed., Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Accessed: Feb. 08, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://docplayer.net/87556924-Place-a-short-introduction-tim-cresswell-ij-blackwell-l-publishing.html.

- Kevin Lynch, THE IMAGE OF THE CITY, 20th ed. London: The M.I.T. Press, 1961.

- I. Aravot, “Back to phenomenological placemaking,” J Urban Des (Abingdon), vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 201–212, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Toolis, “Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space,” Am J Community Psychol, vol. 59, no. 1–2, pp. 184–199, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Seamon and J. Sowers, “Place and placelessness (1976): Edward Relph,” in Key Texts in Human Geography, SAGE Publications Inc., 2008, pp. 43–52. [CrossRef]

- F. Ryfield, D. Cabana, J. Brannigan, and T. Crowe, “Conceptualizing ‘sense of place’ in cultural ecosystem services: A framework for interdisciplinary research,” Ecosyst Serv, vol. 36, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Shamsuddin and M. S. Al-Obeidy, “Evaluating Diversity of Commercial Streets by the Approach of Sense of Place,” Adv Environ Biol, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 193–196, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://www.aensiweb.com/AEB/.

- S. Fayez, A.-N. Supervisor, D. Kamel, and O. Mahadin, “TOWARDS A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO DEFINING SENSE OF PLACE AND CHARACTER ‘THE STREET AND THE CITY OF AMMAN,’” 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Khemri, A. Melis, and S. Caputo, “Sustaining the Liveliness of Public Spaces in El Houma through Placemaking,” The Journal of Public Space, no. Vol. 5 n. 1, pp. 129–152, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Mcdonough, “PLACE-MAKING: A STUDY OF EMERGING PROFESSIONALS’ PREFERENCES OF PLACE-MAKING ATTRIBUTES,” 2013. Accessed: Feb. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/2768.

- N. 10276 U. PO Box 1073 New York, “The Power of 10+, How Cities Transform Through Placemaking,” 2020. https://www.pps.org/article/the-power-of-10 (accessed Feb. 21, 2023).

- Christopher Alexander, A PATTERN LANGUAGE. NEW YORK: OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1977.

- Christopher Alexander, NEW CONCEPTS IN COMPLEXITY THEORY. 2003. Accessed: Mar. 12, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.katarxis3.com/SCIENTIFIC%20INTRODUCTION.pdf.

- J. Gehl, “A Changing Street Life in a Changing Society,” Places, vol. 6, no. 1, 1989, Accessed: Feb. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/46r328ks.

- J. Gehl, LIFE BETWEEN BUILDINGS. Washington, DC: ISLAND PRESS, 2011. Accessed: Feb. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://kupdf.net/download/jan-gehl-life-between-buildingspdf_59d293dd08bbc53f7868720b_pdf.

- J. Montgomery, “Making a city: urbanity, vitality and urban design,” J Urban Des (Abingdon), vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 93–116, 1998. [CrossRef]

- D. v. Canter, “The psychology of place,” Architectural Press, 1977, p. 198. Accessed: Feb. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232600712_The_Psychology_of_Place.

- M. Rasouli, “Analysis of Activity Patterns and Design Features Relationships in Urban Public Spaces Using Direct Field Observations, Activity Maps and GIS Analysis Mel Lastman Square in Toronto as a Case Study,” University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013. Accessed: Feb. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/7383/Rasouli_Mojgan.pdf;sequence=1.

- D. V. Canter, “The Facets of Place,” Dartmouth, 1996, p. 330. Accessed: Feb. 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247875806_The_Facets_of_Place.

- David Seamon, “Awakening to the World as Phenomenon. The value of phenomenology for a pedagogy of place and place making,” 2020.

- David Seamon, Life Takes Place, Phenomenology, Life worlds, and place Making, 1st ed. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Abusaada and A. Elshater, “Effect of people on placemaking and affective atmospheres in city streets,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 3389–3403, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Ghazi and Z. R. Abaas, “Toward liveable commercial streets: A case study of Al-Karada inner street in Baghdad,” Heliyon, vol. 5, no. 5, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Carmona, “Contemporary public space: Critique and classification, part one: Critique,” J Urban Des (Abingdon), vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 123–148, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- V. Mehta, “Lively streets: Determining environmental characteristics to support social behavior,” J Plan Educ Res, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 165–187, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Del Aguila, E. Ghavampour, and B. Vale, “Theory of place in public space,” Urban Plan, vol. 4, no. 2 Public Space in the New Urban Agenda Research into Implementation, pp. 249–259, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Harb, “EXAMINING THE VIBRANCY OF URBAN COMMERCIAL STREETS IN DOHA,” Master of Arts in Urban Planning and Design, QATAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, 2016. doi: http://hdl.handle.net/10576/5118.

- M. Hu and R. Chen, “A Framework for Understanding Sense of Place in an Urban Design Context,” Urban Science, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 34, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Marzbani, J. Awad, and M. Rezaei, “The Sense of Place: Components and Walkability. Old and New Developments in Dubai, UAE,” The Journal of Public Space, vol. 5, no. Vol. 5 n. 1, pp. 21–36, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Al-Kodmany, “Planning guidelines for enhancing placemaking with tall buildings,” Archnet-IJAR, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 5–23, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Erbil Governorate, “Erbil Governorate Profile,” 2015. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.jauiraq.org/documents/380/GP-Erbil%202013.pdf.

- Erbil Governorate, “Eskan neighborhood guide in Erbil, Iraq,” دليل المناطق, السوق المفتوح. https://guide.opensooq.com/%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%82/%d8%a3%d8%b1%d8%a8%d9%8a%d9%84/%d8%af%d9%84%d9%8a%d9%84-%d8%ad%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a5%d8%b3%d9%83%d8%a7%d9%86-%d9%81%d9%8a-%d8%a3%d8%b1%d8%a8%d9%8a%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%82/ (accessed Feb. 22, 2023).

- W. Salih Mohammed and S. M. Al-Jawari, “Spatial Organization of Commercial Streets and Its Impact on the Urban Scene-A Case Study of Al-Jawahiri Street in Al-Najaf, Iraq the divan of Al-Najaf Al-Ashraf Governorate, the Construction Commission, the Resident Engineer Department for Kufa Projects,” International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), vol. Vol. 10 Issue 02, Feb. 2021, [Online]. Available: www.ijert.org.

| No. | Dimensions | Factors | Sub-Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sociability And Diverse Activity Dimension | Social design and Activities | Density | |

| Diversity | ||||

| Functionality | ||||

| Quality of Street | Visibility | |||

| Furniture Availability & Maintenance | ||||

| Satisfaction | ||||

| Economic | Economic Satisfaction | |||

| Adaptability | ||||

| 2 | Physical Setting Dimension | Architectural and Design Sub-Dimension | Building Design | Human Scale |

| Edge Compatibility | ||||

| Morphological, (Building Direction, Building length, | ||||

| Inclusiveness | ||||

| Street Design | Connectivity | |||

| Unity | ||||

| Physical Characteristics | ||||

| Enclosure | ||||

| Architectural Design | Architectural Style | |||

| Urban Context | ||||

| Legibility | ||||

| Access and Linkages Sub-Dimensions | Accessibility | Proximity & Transitivity | ||

| Clarity | ||||

| Walkability | Movement Patterns | |||

| Continuity | ||||

| Spatial Characteristics | Spatial Layout (Patterns) | |||

| Spatial Configuration | ||||

| Spatial-Temporal | ||||

| Environmental Dimension | Sub-Climate Comfort | Climate protection | ||

| Greenery Convenience | ||||

| 3 | Imageability Dimension | Images | Memory | Attractiveness |

| Locality and Identity | ||||

| Place Attachment | ||||

| Safety | Separation | |||

| Speed | ||||

| Comfort | Physical Comfort | |||

| Social Comfort | ||||

| Sense of Place (SOP) | Qualified Street |

Unified Sense of Place | ||

| Social Bonding | ||||

| Sense of Belonging | ||||

|

| No. | selection items | Sub-Numbers | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | location | 1.1 | The selected streets between (Street 30m) and (Street 120m) ring roads. |

| 1.2 | (Street 60 or 100) are not included, while the internal streets link the main traffic circles in Erbil city, connecting two important streets or (the connector roads between circle roads). | ||

| 1.3 | The street falls within the framework of commercial streets that have developed over the years. | ||

| 1.4 | people identified this street as a commercial street. | ||

| 2 | social characteristics | 2.1 | A clear density of pedestrians on the sidewalks of these streets. |

| 2.2 | Functional diversity in activities and services is clear. | ||

| 2.3 | Provides some activities of economic attraction. | ||

| 2.4 | Providing the daily needs of people. | ||

| 2.5 | Each selected sample must have a sidewalk at least allows the passage of 2 people. | ||

| 2.6 | The commercial street includes some activities that provide places to sit and rest. | ||

| 3 | commercial approach | 3.1 | The ground floor is dedicated to commercial activities. |

| 3.2 | should be mixed-use activities, (diversity). | ||

| 3.3 | The possibility of shopping in the street. | ||

| 3.4 | The streets include a mixture of formal and informal shops | ||

| 4 | Architectural feature | 4.1 | some important buildings available within street spaces |

| 4.2 | The presence of common spaces within the commercial street space | ||

| 4.3 | At least one or two types of street furniture are present in the selected samples | ||

| 4.4 | Street height and width are convenient or (in acceptable proportion) | ||

| 5 | street type | 5.1 | The street should be either the type of shared street or integrated activities |

| 5.2 | Being a Minor Streets type where this size will provide spatial enclosure within the three dimensions | ||

| 5.3 | Specified within the commercial street from the municipality | ||

| 5.4 | Collector street, between two main rings in Erbil city | ||

| 6 | sizes & dimensions (physical Attributes) | 6.1 | street length is between (600-2000) m |

| 6.2 | The sidewalk’s dimensions are similar. | ||

| 6.3 | The height of the buildings on both sides is no more than 10 floors | ||

| 6.4 | There are designated places for pedestrians to cross between both sides of the street | ||

| 6.5 | The width of the street is between (20-50) meters, and there are at least two lanes on each side, back and forth |

| Erbil Sectors | No. of Connector Roads | Road Connector width (30-60 m) | Length (500-2000) | Connectors specified as a Commercial | Changed from Commercial to Another function | Changed to Commercial | Street Name | No Colleges or Universities | Functions Compatible with Research need | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector-2 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | Eskan | 0 | 1 |

| Sector-3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Shorsh | 0 | 1 |

| Sector-4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Bryati | 0 | 1 |

| Sector-5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Malla Afandi | 0 | 1 |

| Sector-6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Runaki | 2 | 1 |

| Sector-7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | Adalla | 1 | 1 |

| Sector-8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nawroze | 0 | 0 |

| Sector-9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Baxhtyari | 0 | 1 |

| Sector-10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Ainkawa | 0 | 0 |

| Total Street Number | 45 | 41 | 31 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 27 | 3 | 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).