1. Introduction

Sustainability benchmarking is a crucial practice within higher education institutions, enabling the systematic assessment and comparison of their environmental, social, and economic performance. This study explores the significance of sustainability benchmarking, methodologies specific to academic institutions, and the impact on promoting sustainable practices within the higher education sector. Sustainability benchmarking in higher education involves evaluating and comparing institutions' sustainability performance against established standards, peers, or best practices. This process is integral to identifying areas for improvement, measuring progress, and enhancing the overall sustainability efforts of universities and colleges.

Sustainability is the reflection of an organisation’s performance in economic, social, and environmental terms [

1]. Sustainability benchmarking can elevate the performance of the organisation providing necessary feedback related to the effectiveness of the operations. Higher education institutes are indicative organisations with complex multiple operations that could rely on sustainability benchmarking for the assessment of their efficiency and the transformation of their operations adapting optimal solutions as regards sustainability standards. In particular, the higher education institutes face the challenging process of combining their developmental priorities and the universal policy objectives with the educational settings.

Higher education institutions (HEIs) can function as experiential places of learning for sustainability and should, therefore, orient all their processes toward sustainability principles. HEIs must consider sustainability in all aspects of the institution (Leicht, Heiss, and Byun, 2018). In practice, a whole-institution approach suggests incorporating sustainable development not only through the elements of the curriculum but also through integrated management and governance of the institution (incl. Campus operations, organizational culture, student participation, application of a sustainability ethos, engagement of community and stakeholders, long-term planning, and sustainability monitoring and evaluation), making them microcosms of sustainability [

2].

It is becoming increasingly imperative that HEIs take a more holistic perspective to strengthen their contribution to sustainable development. HEIs behave as complex systems, and sustainability should be seen as an emergent quality that arises from interactions within and between those institutions and the environmental and social contexts in which they operate. The programmatic responses that HEIs often create to address sustainability issues have been inadequate for the deeply embedded problems they face, but coordination of programs based on a systems framework can reach strategic leverage points for organizational change.

A systems’ understanding can enhance the effectiveness of programs that manage campus sustainability by helping to identify key leverage points for action to improve. Viewing an HEI as a whole system can allow measures to evolve the institutional elements and interactions in more sustainable directions while illuminating opportunities to advance sustainability with targeted campaigns aimed at key leverage points [

3].

The whole-system approach should be used for knowledge elicitation among several stakeholders to create a shared understanding related to the complexity of the desired transition, and it should be used as a facilitation tool for assessing, evaluating, and planning strategies toward desired goals. It is a comprehensive and holistic framework considering all interconnected elements and relationships within a system. It involves analyzing and addressing complex problems or challenges by understanding the interdependencies and interactions among various system components. This approach emphasizes the need to view the system, rather than focusing on isolated parts or individual components. The system, such as an HEI, is seen as a dynamic and adaptive entity, where changes in one part can have cascading effects on other factors. It recognizes that systems are often nonlinear, meaning small changes can lead to significant and unexpected outcomes.

This review identifies best practices of institutional sustainability self-assessment models and tools, presenting at least five of those practices covering methods and approaches from Systems Thinking and the whole system. It covers the most prominent and recent research on whole-system approaches. The mapping and review will focus on designing and implementing whole-institution sustainability plans, including models that prioritize using self-assessment tools. The study will emphasize systemic thinking and institutional dynamics, especially from the perspectives of educational leadership and governance structures that embed sustainable principles in organizational transformations at all operational levels and in all institutional practices. It also presents indicative examples of effective self-assessment models for sustainability benchmarking applied by higher education institutes (HEIs) and reported in the literature as effective ones. The goal of the review is to provide sustainability benchmarking tools that have already been implemented with positive outcomes and can be transferred to different university settings so that they facilitate the adoption and implementation of sustainable-friendly every-day practices.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of the research that was carried out followed a structured process of establishing a common framework to ensure that the research outputs would exhibit a satisfactory level of methodological rigour through a comprehensive and systematic approach. We first established fundamental research principles and concepts for the broader conceptualization of the framework, then identified the key research areas to be examined.

2.1. Research Areas

The research was divided in the following four areas:

Fundamental principles, concepts, and policy framework parameters. We also mapped and reviewed the state-of-the-art on the incorporation of green skills and competences in educational activities, both from the perspective of educators and that of learners. The research encompassed pedagogical perspectives such as curricular development and assessment methodologies, professional development, and interdisciplinarity in the implementation of systemic transformations towards the embeddedness of sustainable principles.

General approaches to benchmarking sustainability with an emphasis on organization transformation and operational optimization. The mapping and review also explored the link between developmental priorities and educational settings, especially with respect to universal policy objectives such as the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals at a global level and the European Green Deal at an EU level.

The most prominent and recent research on whole-system approaches. The mapping and review focused on the design, implementation of whole-institution sustainability plans, including models that prioritize the use of self-assessment tools. The research emphasized systemic thinking and institutional dynamics, especially from the perspectives of educational leadership and governance structures that embed sustainable principles in organizational transformations at all operational levels and in all institutional practices.

Benchmarking institutional performance with specific application to HEIs. The mapping and review focused on institutional operations that embed sustainability with particular emphasis on the implementation and monitoring of sustainable practices in campus site operation, as well as the promotion and development of sustainability culture in an educational setting.

2.2. Methodology

The carried-out literature map does not seek to be exhaustive. On the contrary, it is an exploratory study to depict a general outlook of the literature aligned with the stated goals. The initial search strings used to retrieve the articles related to the objective of the present review in each research area. Further variations of search strings were used based on the results obtained and the analysis of the selected articles.

Assuming the transcendence and importance that the term sustainability will have in the coming decades, it is important to observe its evolution within the scientific community. For this, a brief bibliometric analysis was performed. One of the advantages of bibliometrics is that there is no entity as such that can unilaterally impose a criterion or conclusion, but rather it is the scientific community itself—that is, the sum of all their work—that will lead to quantitative results. Furthermore, the publication of a document, from the point of view of the researcher or the scientific community, is not only a publication as such, but it is the result of a creativity process that is shared, judged, and incorporated into existing knowledge. Thus, the knowledge cycle is completed when the new discovery is published and accepted by the scientific community in the same field [

4,

5].

WOS is the most used database, generating useful information for researchers evaluating scientific activity. It is also considered a good option due to its multidisciplinary character, the ability to filter searches using several bibliographic parameters, and because it provides easy access to the full texts of the searched papers. The results on WoS of this search, without applying any filters, were 2.614 documents. These results were adjusted and refined, according to the search criteria defined for this research. Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index were selected, obtaining 1.767 documents. This WOS Core Collection was subsequently filtered, redefining and filtered including articles published in scientific journals. This facilitated the research, since besides guaranteeing the quality of the publications; the journals include multidimensional elements, such as citation, time, language, etc. After debugging the database, the initial query on these terms in the titles, abstracts and keywords resulted in 1.623 documents.

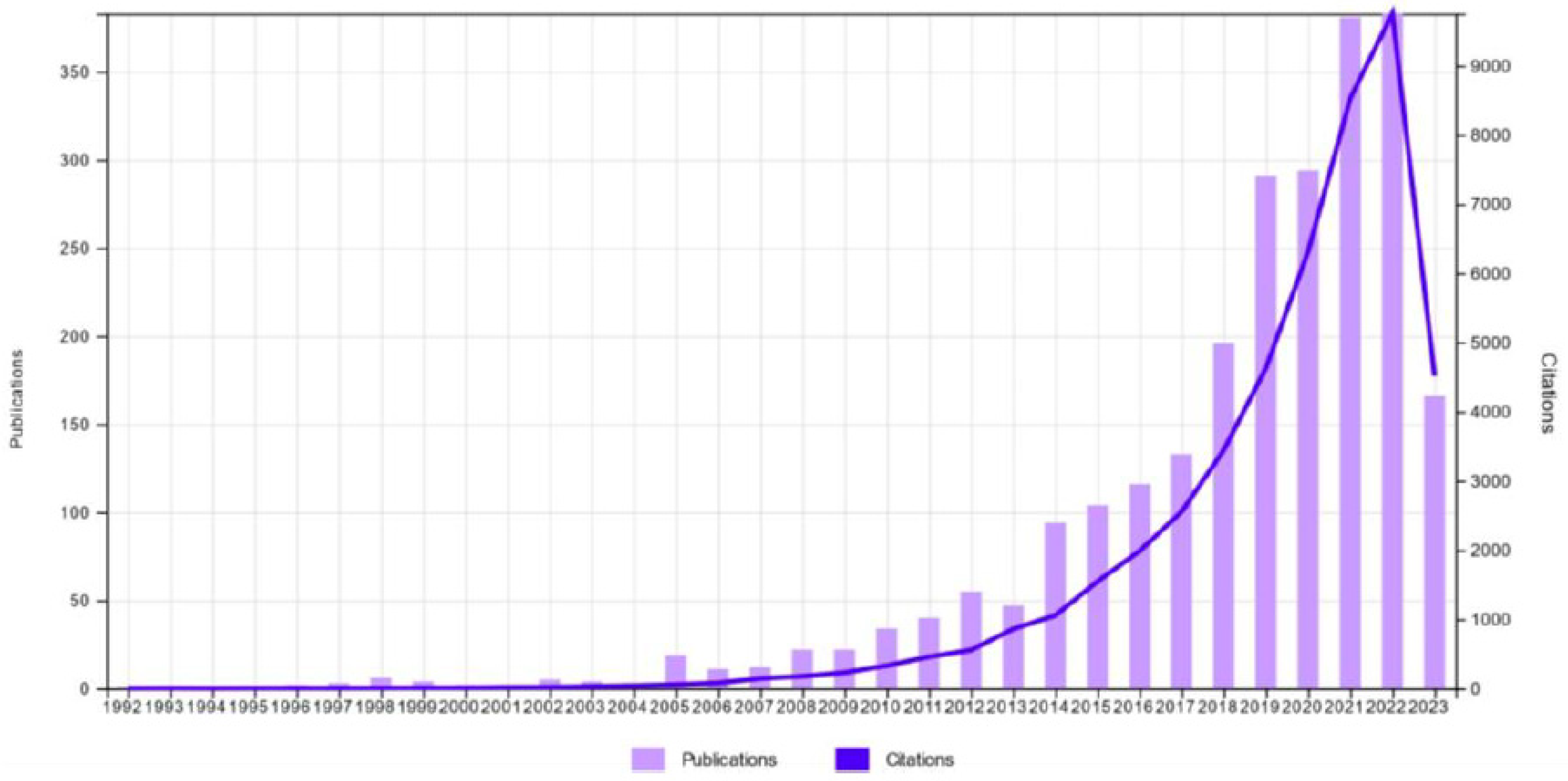

The initial search returned 2.454 articles from the Web of Science Core Collection, and its distribution over the year is shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the number of publications and the number of citations they received over time, and it is possible to note that the scientific community’s interest in these topics is steadily increasing (apparently, following an exponential growth trend).

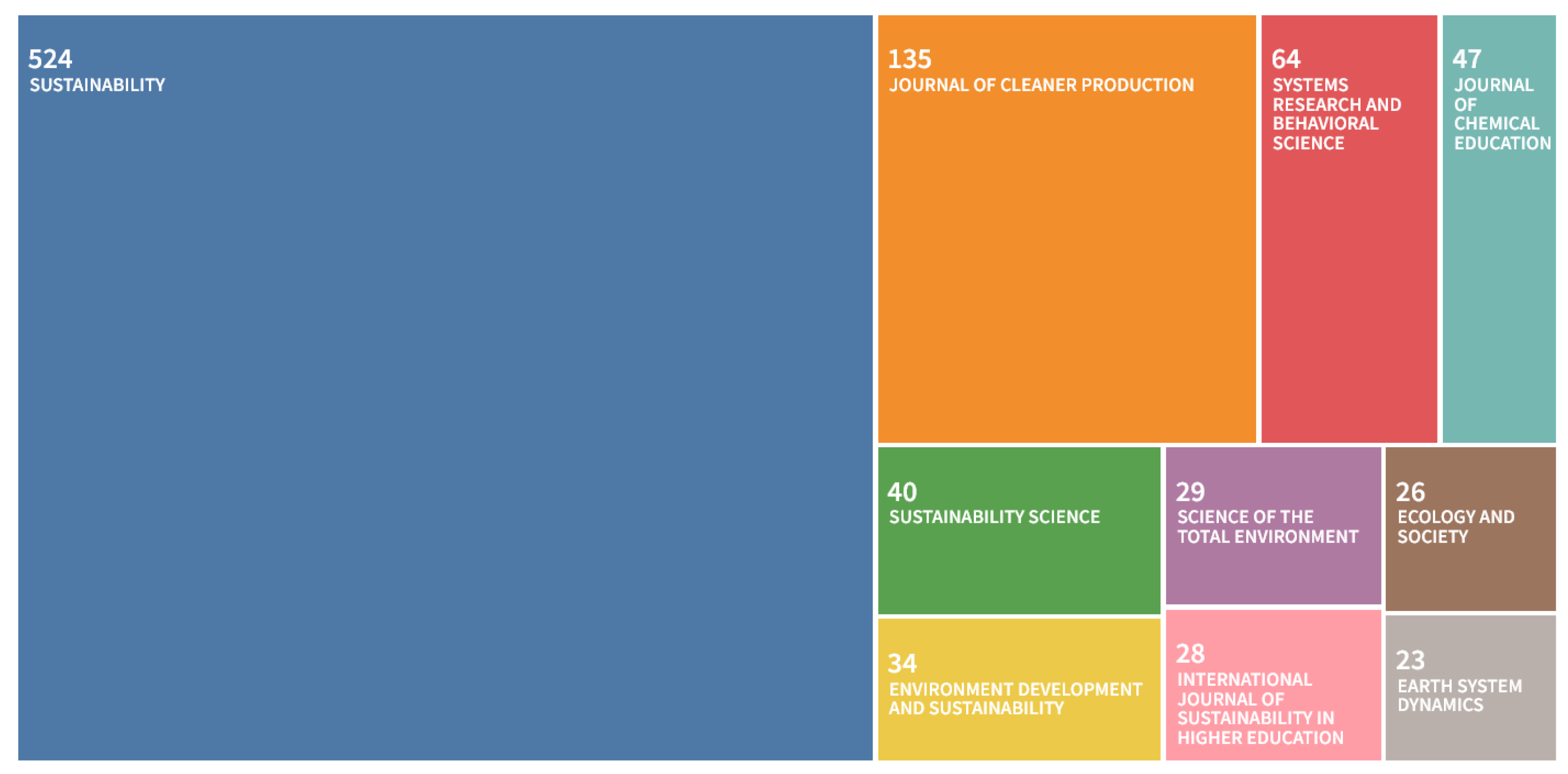

The TreeMap in

Figure 2 shows the leading venues where articles from the retrieved dataset were published. Most of the articles, almost a quarter, were published in “Sustainability” (MDPI, IF - 3.889), “Journal of Cleaner Production” (Elsevier, IF - 11.072), and “System Research and Behavioral Science” (Wiley, IF - 3.64).

3. Results

3.1. Whole Systems Approaches

Organizations are systems, and they are nested within larger systems. In order to survive, their investments must secure both short- and long-term goals. Bansal and DesJardine [

6] argued that sustainability goals should analyze the balance or consistency between organizational and macro-systems over time. Besides, organizations must consider atemporal trade-offs and not omit the time concern from strategic management, which can contribute to short-termism focus and systems’ failure. The authors then conclude that a dynamic systems perspective, which shifts the lens to a bigger picture, could make temporal effects more salient as the feedback mechanisms between levels of analysis come into view.

Hjorth and Bagheri [

7] described sustainable development as an unending process defined neither by fixed goals nor by specific means of achieving them. Thus, System Dynamics operates in a whole-system fashion, and it is seen as a robust methodology for dealing with sustainability issues. They defined sustainability as

… neither a state of the system to be increased or decreased, nor is it a static goal or target to be achieved. But sustainable development is a process in which, in terms of system dynamics, the destroying reinforcing loops are controlled by means of some balancing mechanisms and where these balancing loops are allowed to act normally, as they must do in order to guarantee the system to work everlastingly. [

7]

(p. 86)

In addition, they presented a set of examples of successful applications of such an approach in this context, and then they demonstrated how causal loop diagrams can be used to find the leverage points of a system. The authors also argued that there are key loops in the real world responsible for the viability of all ecosystems, including human-based ecosystems, that they called “Viability loops.” Thus, sustainable development is a process in which those loops remain intact, and planning for sustainability is to identify the viability loops and to keep them properly operating.

The role HEIs play in increasing our society’s capabilities for continuous self-renewing and dealing with the complexities of current and future challenges is not new. Jantsch [

8] discussed how universities should develop interdisciplinary links between the pragmatic and normative systems levels. Then he presented a transdisciplinary structure for the university centered on three organizational units: systems design laboratories, function-oriented and discipline-oriented departments. Jantsch identified policy sciences as a crucial linkage between those three system levels.

Pittman [

9] discussed the use of whole systems design in higher education. The author then proposed a sustainable development framework based on systemic design principles, which he considered a systemic design as a holistic approach that considers the interconnectedness of all the parts of a system. This approach is essential for addressing complex problems like climate change and sustainability.

Sterling [

10] argued that for an HEI appropriately respond to the sustainability challenge, it needs to have a deep appreciation of three fundamental areas of concern, which he metaphorically summarized as the nature of the territory now occupied, the nature of territory that sustainability implies, and the journey that is required to shift from one grounding to another. He used ideas and tools from Systems Thinking to map those grounds and compared the staged social and educational responses to sustainability. Those learning responses vary from “very weak” to “very strong,” and changes in environmental and economic policies and degrees and types of public awareness characterize them.

Faghihimani [

11] proposed a systemic approach based on Systems Thinking, Cybernetics theory, and the Viable System Model for measuring environmental sustainability at HEIs. The proposed method contains fifty indicators for measuring and comparing several international universities’ environmental sustainability performance. Those indicators are organized into five categories: 1) governance and administration, 2) curriculum and study opportunities, 3) research and innovation, 4) operation, and 5) other related activities.

Stephens and Graham [

12] offer a systems approach to promoting sustainability in higher education through their Transition Management Framework (TMF). This framework provides a structured way to guide research and implement sustainable change within HE. The authors highlight the importance of reflective activities and strategic dynamics at a critical level to facilitate and accelerate the transition.

Based on a systematic literature review, Blizzard and Klotz [

13] presented a framework for sustainable whole systems design that included methods such as Systems Thinking, participative design, and ecosystem services. The framework is organized into the following processes:

Problem framing: understanding the problem as a whole, including its root causes and the different stakeholders involved.

Visioning: creating a shared vision for the future based on understanding the problem.

Designing: developing solutions that address problems at the system level.

Implementing: This is the process of putting the solutions into practice.

Evaluating: This is the process of measuring the effectiveness of the solutions and making adjustments as needed.

Several other authors proposed similar processes-oriented frameworks for a systems approach for dealing with sociotechnical complex systems, which include a phase of problem definition, elaboration of plausible hypotheses, creating a model-based representation of the system under investigation, building confidence on the designed formulation, and finally addressing the initial problem by developing intervention policies and uncovering new knowledge [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Those approaches were developed based on well-established literature on methods for planned organizational change and group interventions [

21,

22,

23], which seek to guide multiple stakeholders through the learning process on their challenges. Argyris [

23] labelled this learning process as the “double-learning loop,” where information from the real world not only changes decisions taken but also feeds back to alter mental models, and by changing mental models, it could be possible to intervene and change the system’s structure.

For this learning process and initial phases of problem framing, elaboration of hypotheses, and design of model-based representation of the context, the literature on group model building (GMB) can be of great value. This field of study is vast, and several authors contributed [17, 24, 25]. GMB aims to elicit stakeholders’ knowledge on various aspects and register them on a formal representation while also seeking to build understanding, support, and test assertions. This approach usually consists of presenting the problem, the divergence of interpretations, the convergence of understanding, and the evaluation of alternatives [

26].

Schalok, Verdugo, and Lee [

27] proposed a systematic approach to organization sustainability incorporating key aspects of multiple methods. The proposed approach adapted the quality improvement PDCA cycle and identified three critical characteristics of organizational sustainability: accountability (effectiveness and efficiency), leadership (transformational and strategic execution), and organization process (high-performance teams and quality improvement). The authors emphasized the crucial role of the evaluation process in closing the quality improvement loop, incorporating multiple performance-based perspectives, best practice indicators, collaborative assessment, and a standardized self-assessment instrument. Then, the authors proposed a set of guidelines for evaluation, which consists of:

Make evaluation understandable and a collaborative process

Distinguish between micro and macro-level evaluation

Clarify the intended uses of the information

Use a logic model to frame customer-referenced evaluation questions (i.e., input = customer-referenced factors; throughput = support strategies; output = personal outcomes)

Schalok, Verdugo, and van Loon [

28] proposed a transformation model to support organizations to rapidly adapt to changing challenges and opportunities and increase their effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability. The model is centered on three pillars (values, critical thinking skills, and innovation) and is organized around four components: transformation strategies, organization capacity, and organization outputs and outcomes. The four components integrate current literature and reflect a systems approach aligning transformation pillars and strategies. For evaluation purposes, a set of indicators with multiple perspectives on performance management was defined that considers perspectives such as customer, growth, financial, and internal process.

Besides discussing the principles and practices of the whole system design (WSD), Stansinoupolos et al. [

29] presented several case studies demonstrating how WSD has been used to improve the sustainability of engineered systems. These case studies showed how WSD can help reduce energy consumption, water consumption, and waste production while improving engineered systems’ performance and reliability.

Williams et al. [

30] identified that the interest in the intersection between Systems Thinking and sustainability management topics is increasing, and they found eight research themes applying the Systems Thinking lens to understand sustainability management: behavioral change, leadership, innovation, industrial ecology, social-ecological systems, transition management, paradigm shifts, and education.

3.2. Sustainability Benchmarking

The importance of sustainability as reflecting the economic, social and environmental performance of an organisation for its viability was highlighted by Yakovleva et al. [

1] who suggested a multi-stage procedure to evaluate supply chains sustainability performance. They argue that the combination of quantitative data with the opinions of specialists in the field can provide stakeholders with an index appropriate for sustainability benchmarking of supply chains. The sustainable supply chain management after the Covid-19 pandemic has also caught the attention of Cherrafi et al. [

31] who implemented a qualitative research approach revealing the challenges facing supply chains such as the uncertainty in demand and supply, the regional concentration of suppliers, the globalized supply chains, the limited supplier capacity, and the reduced visibility in the supply network. To the purpose of developing sustainability, the authors suggested the promotion of health and wellbeing of employees and the stabilization of supply chain. The case of logistics service providers was examined by Gupta and Singh [

32] concluding that they utilize green practices to achieve long-term sustainability. Dupada et al. [

33] highlight the knowledge-based value chains as a key factor to organizational sustainability and suggest the utilization of Generic Benchmarking Integrated Innovation Framework for transforming knowledge to results following the organizational objectives. The transformative potential of benchmarking as a mode of governance has also been illuminated by Lecavalier et al. [

34] arguing that benchmarking should be combined with various performance indicators and reflective practices for the support of urban transformation.

The systems perspective of sustainability is pointed out by Dzoro and Telukdarie [

35]. The authors draw upon a banking sector South African company case study measured against global green information and communication technology benchmarks and best practices to propose the most cost-effective data center. A cross-country comparison of socio-economic sustainability based on the intensity of information and communication technologies between advanced, emerging and developing countries using Data Envelopment Analysis was made by Apaydin et al. [

36]. The authors confirmed the strong and significant relationship between ICT and macroeconomic development. However, they found that the socio-economic impact of technologies in emerging markets is relatively lower than in developing countries.

Al Shaiba et al. [

37] focused on sustainability benchmarking of Qatari organisations. They used sustainability as a point of reference and compared the efficiency of local organisations based on international good practices to identify the reasons for inefficiency and facilitate the improvement of organizational efficiency. Overall organization culture and behaviour, human resources and leadership and governance are the three top areas for improvement of local organisations.

Benchmarking as a necessary tool for health care sustainability was illuminated by Huf et al. [

38] who concluded that the integration of laboratories in the clinical care process could improve laboratory management. The barriers and facilitators for the creation of School Health Research Networks in England to address the need for prevention and early intervention of adolescent health and well-being were determined by Widnall et al. [

39].

Florez et al. [

40] suggested the use of an optimization model in the case of project management so that the sustainability performance of a construction program can be maximized. Brady and Hanmer-Dwight [

41] examined the application of energy benchmarking for sustainable buildings. Brondi et al. [

42] used sustainability-based optimization criteria to foster industrial symbiosis within industrial clusters concluding that industrial symbiosis is complementary to industrial sustainability.

Van Staden et al. [

43] applied optimization strategies in the case of a South African gold mine and examined the performance of mobile cooling units. The findings show a decrease in pumped water volumes and operating costs. Gordon and McCann [

44] describe a stakeholder-based sustainable optimization indicator system for activated sludge wastewater treatment plants in the Republic of Ireland that facilitates optimized operation. The low-carbon sustainable operation of wastewater treatment plants was the subject of literature review of Lu et al. [

45] who suggest an innovative design framework to this purpose. Flores-Alsina et al. [46, 47] note the importance of multiple evaluation criteria to operational strategies of wastewater treatment plants. Niayifar and Perona [

48] found that dynamic water allocation policies improve the global efficiency of storage systems relative to constant minimal flows. Sharifi et al. [

49] evaluated 20 algorithms for multi-reservoir dams to determine the optimal operating policy. Souza et al. [

50] worked on reducing physical water losses and rationalizing the use of energy in water supply systems in a case study of Brazil.

Siirola and Edgar [

51] paid attention to the way operational changes could improve energy efficiency in power steam plant systems and how process control affects it. Damgacioglou and Tselik [

52] developed a two-stage decomposition algorithm in an optimization model to solve a multi-period AC grid operation scheduling problem and network reconfiguration outperforming other IEEE testbeds previously used in the literature. Masoudi et al. [

53] applied a novel hybrid workflow to improve economic recovery factor of oilfields in Malaysia. The increase in the operational capacity of harvesting planning techniques through a linear programming model was the aim of the paper by Banhara et al. [

54].

3.3. Sustainability Benchmarking in Higher Education

The sustainable development performance of OECD countries was evaluated by Lamichhane et al. [

55] finding that Quality Education (SDG 4) is worsening. A methodology to measure research for sustainable development was proposed by Hands and Anderson [

56]. The authors tried to map the contributions to sustainable development research and its effects on university research excellence with a replicable content and thematic analysis in a large university. Nobre et al. [

57] based on a literature review suggested new learning processes on sustainability education aligned with the UN education goals and tested in undergraduate business students. Their findings support that students prefer a holistic sustainability learning approach and changes in curricula and learning processes depend mostly on professors’ and deans’ support. To avoid the drawbacks of subject-matter context about sustainability, Lemarchand et al. [

58] used natural language processing to identify sustainability root keywords in module descriptions. The methodology proposed requires minimum analytical skills and is effective to benchmark university curricula to SDGs.

The innovative management strategy of the University of Johannesburg after its merge is illuminated by Barnard and Van der Merwe [

59]. Their findings suggest that institutional innovation is the outcome of planning, brainstorming, benchmarking reviewing, processing, analyzing, and managing and sustainable development can be achieved through strategic leadership, inclusive planning, and constant monitoring. Cardozo et al. [

60] identified the benchmarks of four best ranked higher education institutions and four Brazilian HEIs following the UI GreenMetric World University Ranking. The HEIs with the best ranking make structural changes and capital investments, invest in actions with long-term return, in alternative technologies and students’ participation. A regional sustainability in higher education assessment performance was made by Beringer et al. [

61] who found that the majority of higher education institutes in Atlantic Canada have integrated sustainable development in their curricula, but steps remain to be taken as regards staff development, physical operations and student opportunities.

Abdul Razak et al. [

62] highlights the benefits of the Alternative University Appraisal for the sustainability ratings of higher education institutions which offers benchmarking tools to support diversity. Shriberg [

63] reviewed 11 cross-institutional sustainability assessment tools concluding that decreasing throughput, simultaneous systematic changes and cross-institutional efforts are critical parameters to enhance sustainability in higher education.

The integration of principles of responsible management education (PRME) in business schools was examined by Peschl et al. [

64]. The authors combined a standard benchmarking process and an analytical framework of PRME best practices to set a benchmark for PRME signatories to improve their sustainability performance. The awareness of sustainability by faculty members of a private university in Riyadh was the purpose of the study of Alkhayyal et al. [

65] which served to embed sustainability in the benchmark university. The integration of sustainability courses in Lebanese universities was the focus of the paper of El Hajj et al. [

66] whose multimodal qualitative study showed that reforms in both the products and the processes of universities as well as government support are necessary to help sustainability. A bibliometric analysis was used by Deda et al. [

67] to benchmark the sustainability of higher education institutes and the integration of Life Cycle Assessment on their sustainability impact. Their results indicate that the main barriers for the limited adoption of LCA are the lack of internal information and managing commitment. Cappelletti et al. [

68] followed the Life Cycle Assessment approach to estimate the environmental performance of the members of University of Foggia. The sustainable mobility indicator provided by the authors can be used to identify the benchmark which is the best mobility scenario. Kartikowati et al. [

69] conducted a map analysis of benchmarking in higher education and found that there is a lack of sustainability benchmarking studies. The nexus between GRI sustainability guidelines, Key Performance indicators and strategic goals was the focus of the paper of Yeung [

70]. The benchmarks for the case tertiary education institution were self-financed institutions with impacts developed through media reporting. The development of machine learning models for sustainability assessment of high education institutes was presented by Yang and Guo [

71] including key performance indicators, factor analysis and DEA as necessary steps for high efficiency of the model. Findler et al. [

72] examined whether sustainable assessment tools can measure the impact of higher education institutes on sustainable development and found that they usually neglect it.

A survey of sustainable education on students was carried out by Watson et al. [

73] so as to benchmark the quality of civil and environmental engineering curricula and plan their reformation. The findings showed that the integration of sustainability in the design courses would be helpful for the students. The benchmarking of criteria to validate the content of a rubric that can be used by educators to assess student sustainable design work in engineering was the goal of the paper of Cowan et al. [

74] confirming the importance of some criteria and proposing the removal of other. The case of engineering capstone projects is presented by Brunell et al. [

75]. The authors proposed a Sustainability Implications Scorecard rubric which evaluates the effectiveness in addressing sustainability in engineering design and project. An industry developed design method named Planet Centric Design combined with systems thinking was introduced to master level students by Väätäjä and Tihinen [

76] promoting the concept of sustainability which was perceived by them as applicable for working and personal life.

Alfayozan and Almasri [

77] studied the benchmarking of energy consumption in a University in Saudi Arabia to promote sustainable solutions. Hanieh and Hasan [

78] developed a Go-Green integrated model for sustainability benchmarking of higher education institutions drawing upon an opinion survey of academic experts in Palestinian universities. The carbon footprints of Spanish Universities were analysed by Guerrero-Lucendo et al. [

79] concluding that this could serve as a valid indicator for benchmarking only if including standardized greenhouse gas and electricity consumption sources, using the same emission factors and the activity ratios were calculated from standardized functional units. Alghamdi et al. [

80] applied a probabilistic fuzzy synthetic evaluation framework to operational, academic, and residential buildings at the British University of Colombia to assess the spatiotemporal variability of water, energy and carbon flows so that the higher education institutes can follow more sustainable patterns. Good practices in sustainability are revealed by Benevides et al. [

81] comparing Brazilian universities with European and American ones and applying benchmarking on the implementation of policies in relation to Green Campuses, Living Labs, and socioeconomic sustainability initiatives. Mendoza et al. [

82] suggested a methodological framework for the resource efficiency and environmental sustainability of campuses so that the universities integrate circular economy. The framework was applied in the case of the University of Manchester and illuminated the way circular economy principles can benchmark sustainability practices and key stakeholders could contribute to this purpose. Benchmarking the sustainability of food environments in tertiary education was the target of Mann et al. [

83]. The proposed University Food Environment Assessment tool was assessed as reliable, and a pilot test identified moderate diversity in food environments in Australia. Melles et al. [

84] aimed to provide a country-specific but sector-wide study of campus sustainability in the case of Australia as portrayed in reports, plans and targets and found that higher education institutes present weak institutionalization of sustainability and sector benchmarking could be beneficial.

Cronemberger de Araújo Góes et al. [

85] provided a base upon which the Brazilian HEIs could develop their sustainability assessment tools comparing eight international SATs. Kamal and Asmuss [

86] analysed the effectiveness of benchmarking tools for assessing the University of Saskatchewan sustainability performance and found that the Sustainability Tracking Assessment and Rating System responds effectively in all areas of campus life. Madeira et al. [

87] developed a methodological framework in the case study of Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto which can be used by other higher education institutes to enable sustainability reporting and benchmarking. Comm and Mathaisel [

88] used Wal Mart’s best supply chain management practices to benchmark the sustainability of higher education. Caeiro et al. [

89] critically analysed the assessment and benchmarking tools the holistic approach of integrating Education for Sustainable Development in the case of a Portuguese and a Spanish university. The study revealed the need for common objectives identification of the tools.

The case of women STEM faculty career success in a large private university is the focus of an institutional transformation project named NSF ADVANCE [

90]. A study conducted within the framework of the project confirmed obstacles in career navigation, climate, flexibility in the management of work/life balance and evaluated the university methods to address them. Following these steps, an institutional transformation strategy plan was drafted based on the organizational analysis of Bolman and Deal. Hitch et al. [

91] reviewed the professional development of sessional staff in higher education institutes using as point of reference among others the sustainability principle which refers to quality teaching and good staff, identifying good practices and challenges to be addressed.

Govindarahu et al. [

92] identified factors that enhance sustainability in private universities in Malaysia. Fonseca et al. [

93] mapped the curricula of BSc and MSc courses in Portuguese HEIs which addressed sustainability issues finding that Social Sciences, Engineering and Management courses are the ones that cover the most this subject. Viegas et al. [

94] provided a benchmark of practices of sustainability in higher education institutes by identifying and classifying its critical attributes. Benchmarking Spanish and European universities as regards sustainability approaches was the focus of the paper of Bernaldo et al. [

95] arguing that students’ engagement in the action plan is necessary. The gender differences of university students about cooperative learning as a sustainable benchmark were presented by Baena-Morales et al. [

96]. Females relate cooperative learning to future teaching roles and prefer groups divided following academic criteria.

Pati and Lee [

97] analysed the presidents’ compensation in US higher education institutions in order to benchmark it so that it produces sustainability initiatives. The authors found a significant and positive relationship between the compensation and independent variables such as environmental sustainability, but the proliferation of sustainability is not among the key criteria for the salary.

3.4. Sustainability Research in Higher Education

In addition to the research area on sustainability benchmarking in higher education, which encompasses the thematic areas of general assessment and campus operations, there is a growing literature on substantive sustainability research in higher education. This is further sub-divided into several interrelated but sufficiently distinct areas that are outlined below.

Much of the focus on the integration of sustainability concepts in education has been devoted to various methodologies, pedagogies, and analytical tools that aim to capture the level of integration of sustainable development as a concept. While there is substantial variation in approaches, two key themes characterize the state of the art in the relevant academic literature: 1) various methods of assessing adherence to the SDGs, and 2) various attempts to evaluate the conceptualization, operationalization, and outcomes borne out of the implementation of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014). Both are clearly based on fundamental principles of the growing international consensus on defining and applying concepts and methodologies in pursuit of sustainable development.

Further to this thematic breakdown, the development and evolution of the state of the art in the academic literature exhibits distinct periodicity. Early contributions followed the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals. In this time-period, the integration of sustainable development in education placed primary emphasis on the environmental dimension. Wright’s [

98] meta-analysis concluded that there was no consistent approach to the definition or to the method of integration of sustainable development. While many institutions adhered to the conceptualizations promoted by international agreements, others prioritized a national level approach, while others synthesized elements from a variety of sources in order to produce a distinct institutional implementation that did not necessarily adhere to any one established standard. The study also highlighted the complexity – and inherent lack of consensus at the time – of what the integration of sustainable development elements meant in practice; implementations ranged from sustainable campuses, to academic research, to the environmental literacy of faculty, staff and/or students, to the incorporation of responsibility principles as ethical pronouncements, to intra-institutional cooperation, to the development of interdisciplinary pedagogies, and to outwards relations with state and non-state entities, including liaising with industry in appropriate sectors.

The next major milestone in the literature was the end of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) that was launched in 2005 and ran until 2014, leading to a sharp increase in research output evaluating the impact of the international initiative. The main purpose of the UN Decade was to promote and integrate sustainable development principles into educational systems worldwide. The objectives included raising awareness about sustainable development issues, enhancing the quality of education through the incorporation of sustainable development concepts, and fostering a sense of responsibility and commitment among learners to create a more sustainable future. The official appraisal of the UN Decade came in the form of a final report compiled for UNESCO by Buckler and Creech [

99] that concluded positively that ESD was increasingly effective as an enabler for sustainable development, that stakeholder engagement proved vital to its success and would be even more instrumental in the future, that ESD is increasingly galvanizing pedagogical innovation, and that ESD has spread across all levels and areas of education. The report specifically highlighted the importance of whole institution approaches to help practice ESD. The report also concluded with several themes, trends, and recommendations for the future of ESD integration in higher education institutions:

Leading change for sustainability in higher education presents a significant challenge. In order to advance whole-institution approaches to ESD, leadership development for senior university executives and governors should be expanded and promoted, including coaching, peer learning, action learning and mentoring support.

Student demand for sustainability-related education is on the rise.

Every student, regardless of discipline or career focus should learn to contribute to a more sustainable world. New approaches to curriculum reform are needed, including capacity-building for academic staff, to move sustainable development beyond a specialist ‘career’ focus to a learning outcome and lifelong orientation across all fields of study. The increase in student demand for a sustainability-centered education may be a significant driver for changes in curriculum and teaching practice and should be monitored more closely.

Online learning should be explored further to advance ESD in higher education.

Academic staff development and organizational learning are important for creating sustainable universities.

Networks of higher education institutions build capacity and expand influence on ESD.

Interest in sustainability-related research is on the rise. Sustainability-related research should be more systematically tracked, noting whether and how it is influencing change in policy and practice beyond the institutions. ESD research, as an important area of academic pursuit, should be recognized and supported, and grounded in national ESD research agendas and plans.

Research into ESD itself has increased significantly during the UN Decade

Campus operations have made significant advances in sustainability. Greening campus operations can be strengthened through mechanisms to share tools and approaches, including carbon footprint reductions.

HEIs are extending the value and impact of their teaching and research at the local level and catalyzing community change. Collaboration and partnerships between university researchers and community stakeholders should be scaled up as mechanisms to deepen learning, strengthen the knowledge base on local social, environmental, and economic issues and contribute to solutions for local-level sustainability.

The report was followed by seminal contributions to the literature assessing the effects of the UN Decade and establishing approaches for future implementation. Wals’ [

100] meta-study of the literature led to numerous conclusions, primary among which was the recognition of an emerging trend: while the use of ESD prior to the UN Decade referred primarily to operational optimization (environmental management, university greening and reducing a university's ecological footprint), the use since shifted towards pedagogy, learning, instruction, community outreach and partnerships. Leal Filho et al. [

101] describe the achievements of the UN Decade but also highlight the gaps in terms of moving from rhetoric to action, of implementing more pillars towards a widened conception of sustainable development, and of targeting and engaging policymakers. Most importantly, the paper presents a list of measures aimed at translating the principles of sustainable development into reality:

- 11.

To strengthen sustainable development-related competencies

- 12.

To encourage multi-stakeholder dialogue among individuals and organisations that represent the economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects (and other relevant dimensions) of sustainable development.

- 13.

To emphasize a methodological justification of research as opposed to paying attention to details about methods and outcomes.

- 14.

To pay attention to questions about ends in research.

- 15.

In addition to the use of benchmarking as tools for assessing and tracking sustainability in institutions of higher education, the creation of accessible ESD knowledge-sharing platforms for different kinds of audiences making use of information and communication technologies can make ESD resources much more accessible.

- 16.

Raising funds for ESD activities and projects is very important for materialising the goals of the UN Decade.

- 17.

To exchange of experiences at an international level

- 18.

To use a systems approach to education for sustainability in higher education

- 19.

To further understand and promote campus sustainability, using a systems framework

Lastly, Beynaghi et al. [

102] studied the effects of the UN Decade in the context of the recently adopted SDGs and presented a set of policy measures for a “second decade” to coincide with their pursuit. They framed future scenarios in three distinct areas of sustainable development in HEIs: a social, an environmental, and an economic orientation. Respectively, their suggested policy measures were as follows:

- 20.

Social orientation

- 21.

Signals need to be sent to universities and faculty that societal engagement is valued and desired [

103]

- 22.

University performance appraisal systems have a large potential to influence university behavior in a desired direction [104, 105]

- 23.

Government funding programmes can stipulate socially orientated themes for research and engagement with external stakeholders, surrounding communities and regions [

106]

- 24.

Universities and departments could consider societal engagements and impacts along with conventional outputs when evaluating faculty performance for tenure.

- 25.

The alignment of education, research and outreach with local needs is vital for authentic social engagement

- 26.

Environmental orientation

- 27.

National governments can allocate performance-based research funds according to contributions to the environment.

- 28.

The campus itself represents a ripe occasion for the university to demonstrate environmental sustainability and innovation [107, 108]

- 29.

Universities can increasingly position their campuses, buildings, and real estate assets as “living laboratories” [

109]

- 30.

University-led urban reform can function as a driver of green building innovation and environmental improvements [

110]

- 31.

Universities can generate diverse opportunities for students and faculty to exploit urban environmental transformations processes as platforms for experiential and project-based sustainability education [111, 112]

- 32.

Economic orientation

- 33.

Governments can take measures to encourage universities to forge closer industrial ties and harness their resources to the goal of driving economic growth.

- 34.

Governments can shift their expectations regarding university-industry exchanges from traditional “hard” outcomes such as patents, licenses, and technological prototypes [

113] to “softer” forms of industry exchange and economic activity that would also compliment ESD implementation such as internships [

114], student consulting to industry [

115] and collaborative teaching.

- 35.

Universities can offer incentives to faculty to encourage commercialization of research outcomes [

116].

Following the adoption of the SDGs in the post-2015 international developmental agenda, research on the integration and attainments of the goals has by far and away attracted the most scholarly attention in the relevant academic literature. Given the expansive scope of the SDGs that adopt a holistic approach that aims to enhance the interrelated aspects of developmental attributes, a comprehensive review of the state of the art is beyond the scope – and size limitations – of this study. As a result, we devote our attention to the causal linkages between the attainment of the SDGs and the degree to which higher education institutions can both benefit from and contribute towards these causal pathways.

Albareda-Tiana et al. [

117] produced the first seminal case study in the implementation of the SDGs at University level through a case study of the International University of Catalonia. The study concluded that the consistent incorporation of ESD as well as specific references to the SDGs into university curricula is essential for HEIs to make a robust commitment towards the promotion of a culture of sustainability. This will require a fundamental reconceptualization of the principles that guide a university’s mission, in addition to the adoption of practices to put these principles into effect. Reworked curricula must exemplify the interconnections between different dimensions of sustainability to properly train individuals for constantly evolving job markets. Lastly, implementing ESD and the SDGs in higher education can lead to synergies within HEIs in addition to linkages outside the institutions to society at large. Leal Filho et al. [

118] further emphasize this transformative aspect in all institutional characteristics of HEIs but especially highlight the need to prioritize the transformation of curricula. They place particular focus on the role of faculty to accommodate and expedite this transformative process through the development of collaborative processes, as well as the necessity for a whole institution approach towards the embeddedness of a culture and a set of practices for sustainability. Kioupi and Voulvoulis [

119] place singular emphasis on education through an examination of SDG4. While they do not focus exclusively on HEIs, they conclude that a systems perspective is essential for the transformative potential to be realized at all levels of education.

Subsequent contributions to the state of the art in the literature have emphasized the importance of curricular development even further. Leal Filho et al. [

120] assert that HEIs must align both their curricula and their research to SDGs. In so doing, HEIs may develop, test, and use new contents, learning methods and transformative approaches. Furthermore, they must develop more applied research around the SDGs and suggest that doctoral programmes are best suited for this purpose. Lastly, they highlight the role of active student engagement. Similarly, Purcell et al. [

121] conceptualize universities as “living labs” for sustainability where the experimental aspects of this transformation can serve as a guide towards the recognition and adoption of good practices.

Lozano et al. [

122] assess the connections between difference competence areas in sustainable development education and pedagogical approaches used and find that while economic, environmental, and cross-cutting dimensions tend to be addressed almost equally, the social dimension remains the most underdeveloped and the least addressed by university curricula. More specifically, they identify gaps in the development of competences in justice, responsibility, and ethics; interpersonal relations and collaboration; empathy and change of perspective; communication and use of media; tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty; and critical thinking and analysis. They also identify that the pedagogical approaches least likely to develop ESD competences are case studies; supply chain/life cycle; and lecturing. Instead, they suggest prioritizing pedagogies such as: eco-justice and community; project- and/or problem-based learning; community service learning; mind and concept maps; jigsaw/interlinked teams; and place-based environmental education. Similarly, Tejedor et al. [

123] suggest five active learning strategies as good didactic strategies to promote competencies in sustainability: service learning, problem-based learning, project-oriented learning, simulation games and case studies.

As the literature matures, more recent contributions have focused more thoroughly on individual issues and challenges to be met along the transformative path towards the integration of ESD. For example, Okanovic et al. [

124] provide a framework whereby universities can assess green content and eco-labeling in their curricula as the means towards increasing their competitiveness by meeting the increasing requirements of green jobs. Lastly, Kioupi and Voulvoulis [

125] present a framework that encompasses six steps that offer tools on how to assess the alignment of university programs’ Learning Outcomes (LOs) to sustainability and how to translate them into competences for sustainability. They suggest that teaching staff and program coordinators should:

- 36.

Assess the alignment of their program’s LOs to their sustainability vision.

- 37.

Translate the aligned LOs into a set of competences.

- 38.

Define sustainability competences using clear statements on what the students need to master and describe their cognitive, affective, behavioral, and metacognitive dimensions.

- 39.

Evaluate a course’s assessment methods to establish how well these methods assess students’ competence development and, if necessary, adopt new methods.

- 40.

Evaluate student performance or progress and provide evidence on the efficacy of the learning and teaching process.

- 41.

Identify the contribution of a program to developing sustainability competences in its learners.

4. Discussion

The map study presented identified several approaches related to the systems approach to sustainability. These approaches rely on the whole-system, whole-institution, transformation management, and assessment methods. By merging and adopting these tools, HEIs can embrace a sustainable mindset, implement environmentally responsible practices, and foster a culture of sustainability within their campus, contributing significantly to a more sustainable future for the institution and the broader community.

Whole-system approaches to sustainability in higher education focus on the interconnectedness of all institution aspects, from teaching and research to campus operations and community engagement. This approach recognizes that sustainability is not just about changing one or two areas of the institution but transforming the entire institution to be more sustainable. Whole-institution approaches to sustainability go a step further than whole-system approaches by requiring the active participation of all stakeholders, from students and faculty to staff and administrators, ensuring that sustainability is not just a few people’s responsibilities but something everyone in the institution is committed to.

Self-assessment tools can help higher education institutions assess their sustainability performance and identify areas for improvement. These tools can also help institutions to track their progress over time. When used together, whole-system, whole-institution, and self-assessment tools can provide HEIs with the framework and support necessary to plan and design strategies for transitioning to more sustainable operation, development, and education.

In further research, the approaches described in this review shall be tailored to design a framework that will support incorporating sustainability principles and strategies within HEIs. One example of such transformation is the incorporation of the whole-institution sustainability approach in HEI through systems thinking (e.g., by changing/adapting existing curricula), promoting green and sustainable transitions (e.g., developing short/medium/long-term plans), and supporting education and training on the systems approach to addressing cross-cutting policies (e.g., European Commission’s Green Deal). The framework resulting from the combination of such approaches can help to achieve systemic integration of sustainability and promote an institutional model to support strategic planning that effectively responds to evolving needs and conditions to attain systemic integration of sustainability at the institutional level.

In addition, the research produces the following recommendations for higher educational leaders:

Acknowledge that the HEI system is comprised of several interrelated elements (including institutional framework, education, research, campus operations, community outreach, collaboration with other higher education institutions, on-campus life experiences, assessment and reporting, collaboration with other HEIs, Sustainable Development as an integral part of the institutional framework, on campus life experiences, and ‘Educate-the-Educators’ programmes).

Commit to Sustainable Development by integrating it into the HEI's policies and strategies.

Show the HEI's commitment by signing an array of Declaration, Charters and Initiatives.

Establish short-, medium-, and long-term plans for the institutionalisation of Sustainable Development; and ensure that Sustainable Development is implemented throughout the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.C., S.A., and I.P.; methodology, O.C., D.M., S.A., E.F., A.B., and I.P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.C., D.M., S.A., E.F., A.B., and I.P.; writing—review and editing, O.C., D.M., and I.P.; visualization, S.A. and E.F.; supervision, O.C. and I.P.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, S.A. and I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by the European Commission’s Erasmus+ program, grant number 101086809.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yakovleva, N.; Sarkis, J.; Sloan, T. Sustainable benchmarking of supply chains: The case of the food industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1297–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Global citizenship education: Preparing learners for the challenges of the 21st century. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014.

- Posner, S. M.; Stuart, R. Understanding and advancing campus sustainability using a systems framework. Int. J. Sustain. High. Edu. 2013, 14, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Gadd, E.; Petersohn, S.; Sbaffi, L. Competencies for bibliometrics. J. Libr. & Info. Sci. 2019, 51, 746-762. [CrossRef]

- Donner, P.; Schmoch, U. The implicit preference of bibliometrics for basic research. Scientometrics 2020, 124, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M. R. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strat. Org. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, P.; Bagheri, A. Navigating towards sustainable development: A system dynamics approach. Futures 2006, 38, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantsch, E. Inter-and transdisciplinary university: A systems approach to education and innovation. High. Edu. 1972, 1, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J. Living Sustainably Through Higher Education: A Whole Systems Design Approach to Organizational Change. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability; Corcoran, P.B., Wals, A.E.J., Eds. Springer: Dordrecht, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Higher education, sustainability, and the role of systemic learning. In Higher education and the challenge of sustainability: Problematics, promise, and practice (pp. 49-70). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Faghihimani, M. A Systemic approach for measuring environmental sustainability at higher education institutions: A case study of the University of Oslo. Master's thesis, University of Oslo, Norway, December 2012.

- Stephens, J. C.; Graham, A. C. Toward an empirical research agenda for sustainability in higher education: exploring the transition management framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizzard, J. L.; Klotz, L. E. A framework for sustainable whole systems design. Design Studies 2012, 33, 456–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K. Strategic management dynamics. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- Sterman, J. Business dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Homer, J. Why we iterate: Scientific modeling in theory and practice. Sys. Dyn. Rev. 1996, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, J. D.; Sterman, J. D. (Eds.) Modeling for learning organizations. Productivity Press, 2000.

- Senge, P. M.; Sterman, J. D. Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1992, 59, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randers, J., Ed. Elements of the System Dynamics Method. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications, 1980.

- Roberts, E. Ed. Managerial Applications of System Dynamics. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications, 1978.

- Michael, D. N. Learning to Plan-and Planning to Learn. Miles River Press, 1997.

- Beckhard, R.; Harris, R. Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Change, 2nd ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987.

- Argyris, C. Strategy, change and defensive routines. Pitman Publishing, 1985.

- Vennix, J.; Richardson, G.; Andersen, D. (Eds.) Special Issue: Group model building, Sys. Dyn. Rev. 1997, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vennix, J. Group Model Building: Facilitating Team Learning Using System Dynamics. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons, 1996.

- Ackermann, F.; Andersen, D. F.; Eden, C.; Richardson, G. P. ScriptsMap: A tool for designing multi-method policy-making workshops. Omega 2011, 39, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R. L.; Verdugo, M.; Lee, T. A systematic approach to an organization’s sustainability. Eval. & Prog. Plan. 2016, 56, 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R. L.; Verdugo, M. A.; van Loon, J. Understanding organization transformation in evaluation and program planning. Eval. & Prog. Plan. 2018, 67, 53-60. [CrossRef]

- Stansinoupolos, P.; Smith, M. H.; Hargroves, K.; Desha, C. Whole system design: An integrated approach to sustainable engineering. London: Taylor & Francis, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Kennedy, S.; Philipp, F.; Whiteman, G. Systems thinking: A review of sustainability management research. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrafi, A.; Chiarini, A.; Belhadi, A.; El Baz, J.; Chaouni Benabdellah, A. Digital technologies and circular economy practices: Vital enablers to support sustainable and resilient supply chain management in the post-COVID-19 era. TQM J. 2022, 34, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, R. K. Managing operations by a logistics company for sustainable service quality: Indian perspective. Manag. Env. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupada, S.; Gedela, R. K.; Aryasri, R. C.; Acharya, R. Building value chain through actionable benchmarking for sustainability and excellence. In Proceedings of the 2013 2nd International Conference on Information Management in the Knowledge Economy, IMKE 2013, 24-30.

- Lecavalier, E.; Arroyo-Currás, T.; Bulkeley, H.; Borgström Hansson, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Lenhart, J.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Can you standardise transformation? Reflections on the transformative potential of benchmarking as a mode of governance. Loc. Env. 2023, 28, 918-933. [CrossRef]

- Dzoro, M.; Telukdarie, A. The development of a rapid deployment tool set for green ict evaluations in the banking sector. In Proceedings of the IAMOT 2016 - 25th International Association for Management of Technology Conference, Proceedings: Technology - Future Thinking, 1212-1233.

- Apaydin, M.; Bayraktar, E.; Hossary, M. Achieving economic and social sustainability through hyperconnectivity: A cross-country comparison. Benchmarking 2018, 25, 3607–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaiba, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S. G.; Koç, M. Measuring efficiency levels in Qatari organizations and causes of inefficiencies. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huf, W.; Mohns, M.; Bünning, Z.; Lister, R.; Garmatiuk, T.; Buchta, C.; Ettl, B. Benchmarking medical laboratory performance: Survey validation and results for Europe, Middle East, and Africa. Clin. Chem. & Lab. Med. 2022, 60, 830-841. [CrossRef]

- Widnall, E.; Hatch, L.; Albers, P. N.; Hopkins, G.; Kidger, J.; de Vocht, F.; Kaner, E.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Fairbrother, H.; Jago, R.; Campbell, R. Implementing a regional school health research network in England to improve adolescent health and well-being, a qualitative process evaluation. BMC Pub. Health 2023, 23, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez, L.; Castro, D.; Medaglia, A. Program management optimization model using sustainability performance indicators. In Proceedings of the 53rd Conference of the Operational Research Society 2011, 99-104.

- Brady, L.; Hanmer-Dwight, R. The management and control of energy at the design stage of buildings. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference, ARCOM 2016, 1171-1180.

- Brondi, C.; Cornago, S.; Ballarino, A.; Avai, A.; Pietraroia, D.; Dellepiane, U.; Niero, M. Sustainability-based optimization criteria for industrial symbiosis: The Symbioptima case. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP, 2018, 69, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Staden, H. J.; van Rensburg, J. F.; Groenewald, H. J. Optimal use of mobile cooling units in a deep-level gold mine. Int. J. Min. Sci. & Tech. 2020, 30, 547-553. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G. T.; McCann, B. P. Basis for the development of sustainable optimisation indicators for activated sludge wastewater treatment plants in the republic of Ireland. Water Sci. & Tech. 2015, 71, 131-138. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, Q.; Luo, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, B.; Si, Q.; Zheng, S.; Guo, W.; Ren, N. Automatic control and optimal operation for greenhouse gas mitigation in sustainable wastewater treatment plants: A review. Sci. Total Env. 2023, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Alsina, X.; Arnell, M.; Amerlinck, Y.; Corominas, L.; Gernaey, K. V.; Guo, L.; Lindblom, E.; Nopens, I.; Porro, J.; Shaw, A.; Snip, L.; Vanrolleghem, R. A.; Jeppsson, U. Balancing effluent quality, economic cost and greenhouse gas emissions during the evaluation of (plant-wide) control/operational strategies in WWTPs. Sci. Tot. Env. 2014, 466-467, 616-624. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Alsina, X.; Arnell, M.; Corominas, L.; Sweetapple, C.; Fu, G.; Butler, D.; Vanrolleghem, P. A.; Gernaey, K. V.; Jeppsson, U. Benchmarking strategies to control GHG production and emissions. In: Quantification and Modelling of Fugitive Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Urban Water Systems: A report from the IWA Task Group on GHG; Ye, L., Porro, J., Nopens, I., Eds.; IWA Publishing, 2022, pp. 213-228. [CrossRef]

- Niayifar, A.; Perona, P. Dynamic water allocation policies improve the global efficiency of storage systems. Adv. Water Res. 2017, 104, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M. R.; Akbarifard, S.; Madadi, M. R.; Akbarifard, H.; Qaderi, K. Comprehensive assessment of 20 state-of-the-art multi-objective meta-heuristic algorithms for multi-reservoir system operation. J. Hydro. 2022, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E. V.; Covas, D. I. C.; Soares, A. K. Towards the improvement of the efficiency in water resources and energy use in water supply systems. In Proceedings of the 10th International on Computing and Control for the Water Industry, CCWI 2009, 583-590.

- Siirola, J. J.; Edgar, T. F. Process energy systems: Control, economic, and sustainability objectives. Comp. & Chem. Eng. 2012, 47, 134-144. [CrossRef]

- Damgacioglu, H.; Celik, N. A two-stage decomposition method for integrated optimization of islanded AC grid operation scheduling and network reconfiguration. Int. J. Elec. Power & Energy Sys 2022, 136. [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, R.; Jalan, S.; Sinha, A. K. Application of a novel hybrid workflow with data analytics and analog assessment for recovery factor benchmarking and improvement plan in malaysian oilfields. In Proceedings of the Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition 2020.

- Banhara, J. R.; Rodriguez, L. C. E.; Seixas, F.; Moreira, J. M. M. A. P.; Da Silva, L. M. S.; Nobre, S. R.; Cogswell, A. Optimized harvest scheduling in eucalyptus plantations under operational, spatial and climatic constraints. Forest Sci. 2010, (85), 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, S.; Eğilmez, G.; Gedik, R.; Bhutta, M. K. S.; Erenay, B. Benchmarking OECD countries’ sustainable development performance: A goal-specific principal component analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hands, V.; Anderson, R. Benchmarking Sustainability Research: A Methodology for Reviewing Sustainable Development Research in Universities. In: Sustainable Development Research at Universities in the United Kingdom; Leal Filho, W. Eds. World Sustainability Series. Cham: Springer, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F. S., Arevalo, J. A., & Mitchell, S. F. (2017). Sustainability learning processes: Concepts, benchmarking, development, and integration. In: Handbook of Sustainability in Management Education: In Search of a Multidisciplinary, Innovative and Integrated Approach; Arevalo, J. A., Mitchell, S. F., Eds. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc., 2017, v. 1, p. 242-261. [CrossRef]

- Lemarchand, P.; McKeever, M.; MacMahon, C.; Owende, P. A computational approach to evaluating curricular alignment to the United Nations sustainable development goals. Front. Sust. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Z.; Van der Merwe, D. Innovative management for organizational sustainability in higher education. Int. J. Sust. High. Edu. 2016, 17, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, N.H.; da Silveira Barros, S.R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Filho, E.R.M.; Salles, W. Benchmarks Analysis of the Higher Education Institutions Participants of the GreenMetric World University Ranking. In: Universities and Sustainable Communities: Meeting the Goals of the Agenda 2030; Leal Filho, W., Tortato, U., Frankenberger, F., Eds. World Sustainability Series. Cham: Springer, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Beringer, A.; Wright, T.; Malone, L. Sustainability in higher education in Atlantic Canada. Int. J. Sust. High. Edu. 2008, 9, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Razak, D.; Sanusi, Z. A.; Jegatesen, G.; Khelghat-Doost, H. Alternative university appraisal (AUA): Reconstructing universities’ ranking and rating toward a sustainable future. In: Sustainability assessment tools in higher education institutions: Mapping trends and good practices around the world; Caeiro, S., Filho, W., Jabbour, C., Azeiteiro, U., Eds. Springer, Cham, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Shriberg, M. Institutional assessment tools for sustainability in higher education: Strengths, weaknesses, and implications for practice and theory. High. Edu. Pol. 2002, 15, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschl, H.; Sug, I. I.; Ripka, E.; Canizales, S. Combining best practices framework with benchmarking to advance principles for responsible management education (PRME) performance. Int. J. Manag. Edu. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhayyal, B.; Labib, W.; Alsulaiman, T.; Abdelhadi, A. Analyzing sustainability awareness among higher education faculty members: A case study in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M. C.; Moussa, R. A.; Chidiac, M. Environmental sustainability out of the loop in Lebanese universities. J. Int. Edu. Bus. 2017, 10, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deda, D.; Gervásio, H.; Quina, M. J. Bibliometric analysis and benchmarking of life cycle assessment of higher education institutions. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, G. M.; Grilli, L.; Russo, C.; Santoro, D. Benchmarking sustainable mobility in higher education. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartikowati, R. S.; Putra, Z. H.; Gimin; Dahnilsyah. Map analysis of benchmarking in higher education using VOSViewer. In: Proceedings of URICET 2021 - Universitas Riau International Conference on Education Technology 2021, 436-440. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S. M. Innovation in the application of GRI to visualize strategic goals for sustainable development – The case of tertiary institution, Hong Kong. Corp. Own. & and Contr. 2015, 12(4CONT5), 572-585. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, L. Research on diagnostic test and treatment for higher education system. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Frontiers Technology of Information and Computer, ICFTIC 2021, 291-300. [CrossRef]

- Findler, F.; Schönherr, N.; Lozano, R.; Stacherl, B. Assessing the impacts of higher education institutions on sustainable development-an analysis of tools and indicators. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. K.; Noyes, C.; Rodgers, M. O. Student perceptions of sustainability education in civil and environmental engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Edu. & Pract. 2013, 139, 235-243. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, C.; Barrella, E.; Watson, M. K.; Anderson, R. Validating Content of a Sustainable Design Rubric Using Established Frameworks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio. [CrossRef]

- Brunell, L. R.; Dubro, A.; Rokade, V. V. Assessing the sustainability components of engineering capstone projects. In: Proceedings of the 2021 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition.

- Väätäjä, H. K., & Tihinen, M. K. Developing future working life competencies with earth-centered designs. In: Proceedings of the SEFI 2022 - 50th Annual Conference of the European Society for Engineering Education, 797-805. [CrossRef]

- Alfaoyzan, F. A.; Almasri, R. A. Benchmarking of energy consumption in higher education buildings in Saudi Arabia to be sustainable: Sulaiman al-Rajhi university case. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanieh, A.A.; Hasan, A.A. A Proposed System for Greening Higher Education Institutions in Palestine. In: Manufacturing Driving Circular Economy; Kohl, H., Seliger, G., Dietrich, F., Eds. Cham: Springer, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Lucendo, A.; García-Orenes, F.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Alba-Hidalgo, D. General mapping of the environmental performance in climate change mitigation of spanish universities through a standardized carbon footprint calculation tool. Int. J. Env. Res. & Pub. Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.; Hu, G.; Chhipi-Shrestha, G.; Haider, H.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Investigating spatiotemporal variability of water, energy, and carbon flows: A probabilistic fuzzy synthetic evaluation framework for higher education institutions. Environments 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevides, M.C.d.S.e.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.; Birch, R.S.; Deggau, A.B. Corporate Sustainability Benchmarking in Academia: Green Campus, Living Labs, Socioeconomic and Socioenvironmental Initiatives in Brazil. In: Universities, Sustainability and Society: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A.L., Brandli, L., Azeiteiro, U.M., Pretorius, R., Eds. World Sustainability Series. Cham: Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J. M. F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. A methodological framework for the implementation of circular economy thinking in higher education institutions: Towards sustainable campus management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]