Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

11 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

Data Analysis and Interpretation

3. Discussion

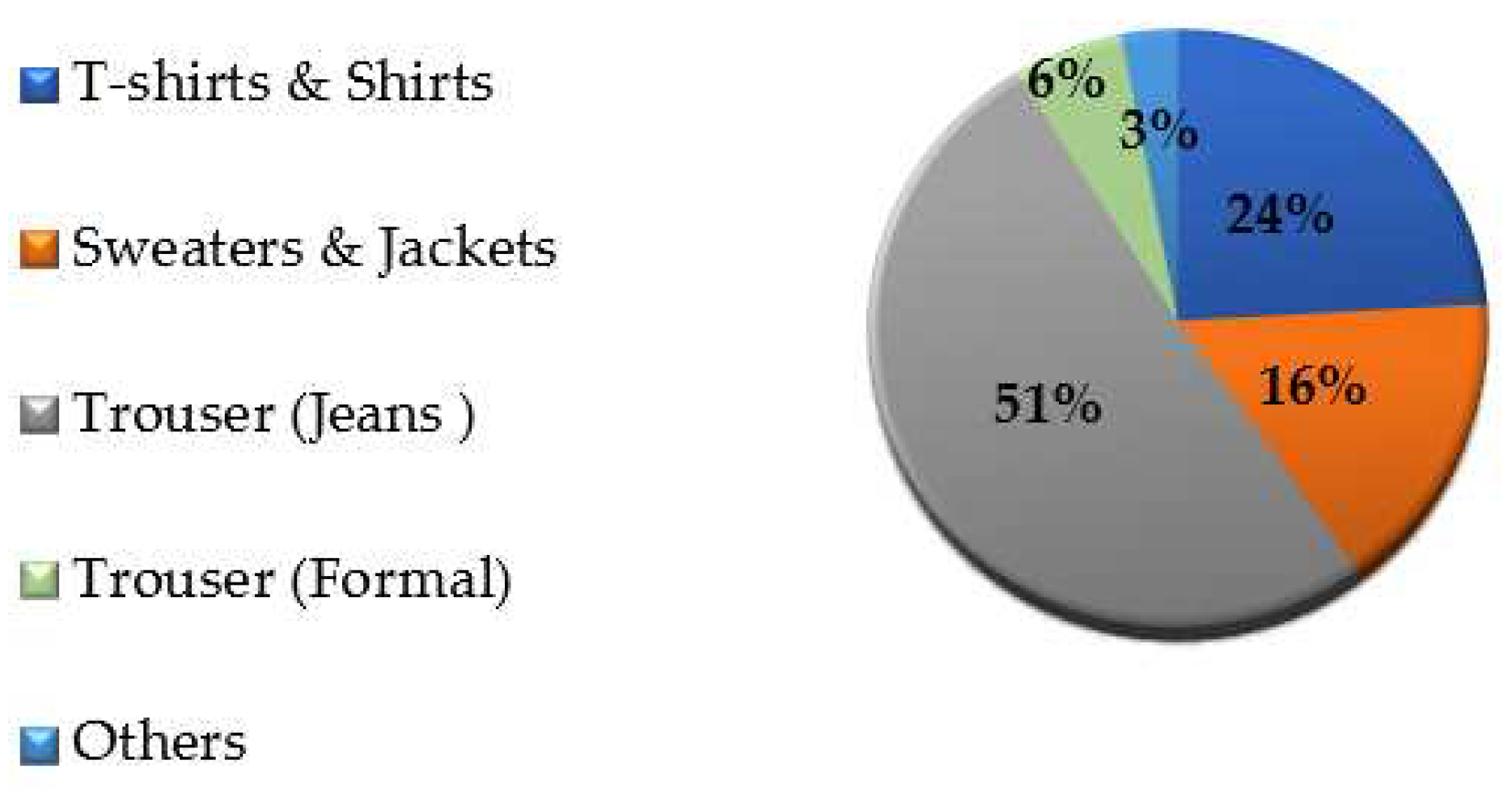

3.1. Level of PCCW Generation Survey Result

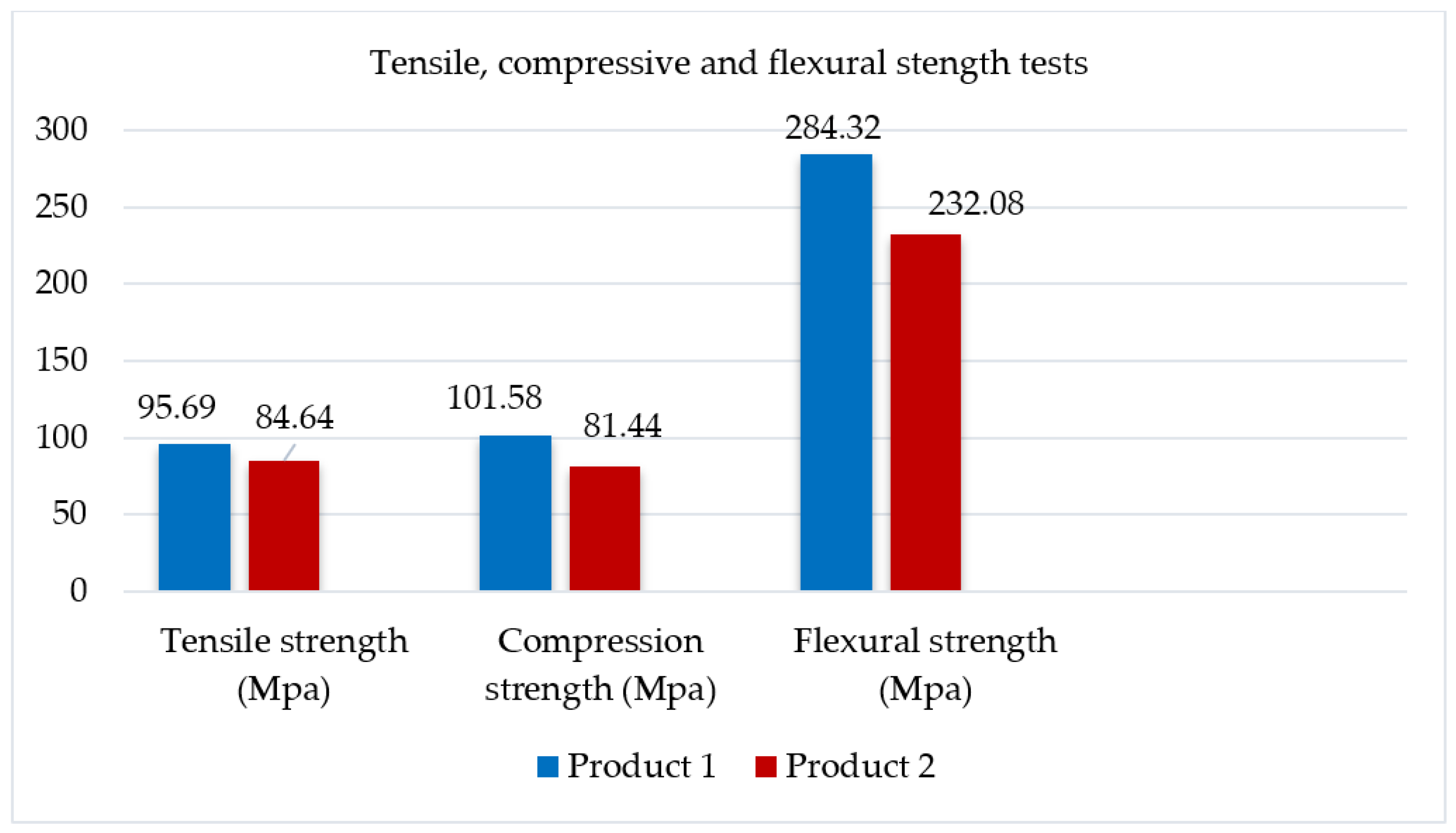

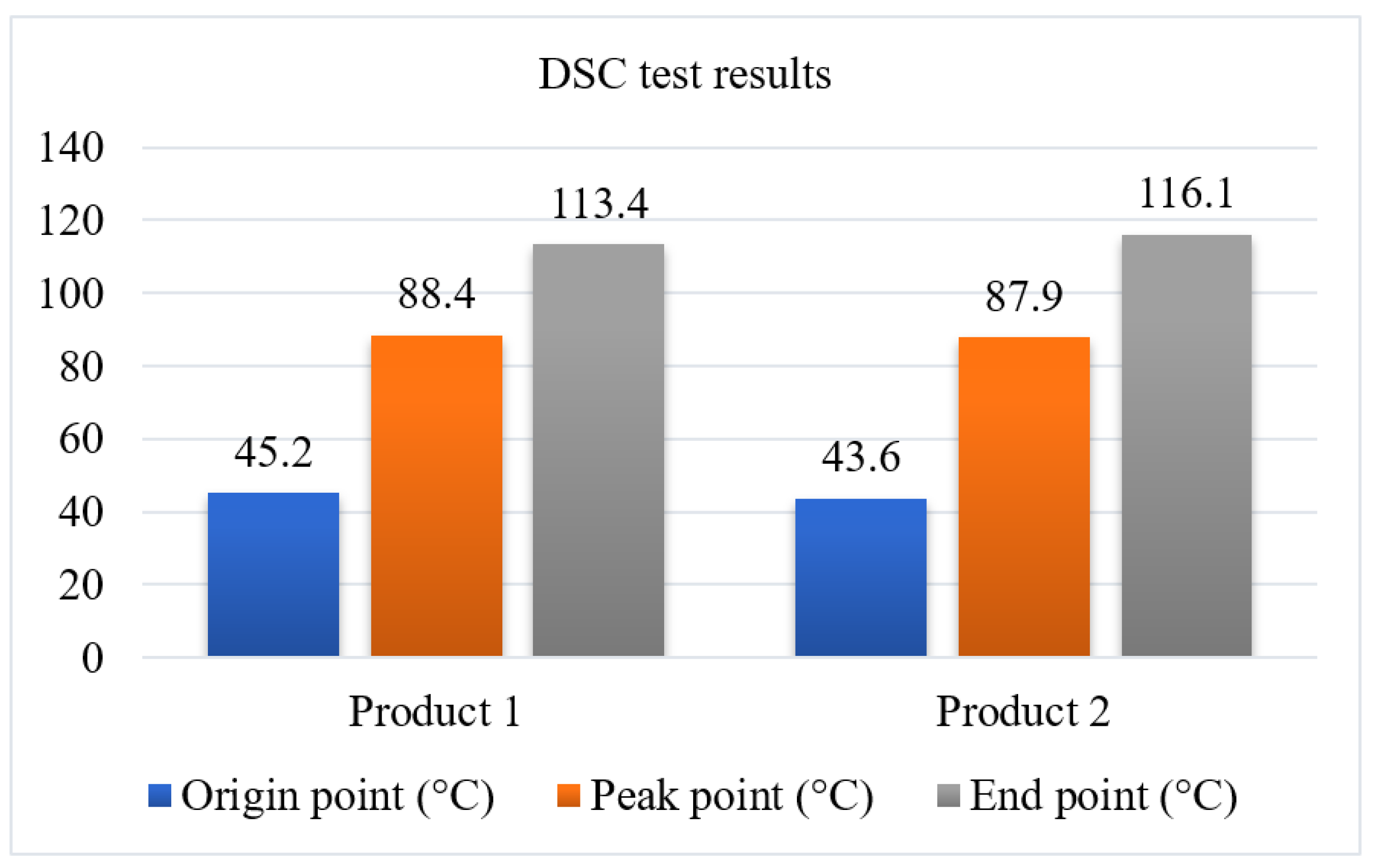

3.2. Results of Mechanical Strengths, Physical and Thermal Property Tests

3.3. Comparison of Commercial Products with Manufactured Composite Samples

3.4. Feasibility Study of Composite Manufacturing from PCCW

3.5. Financial Feasibility Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Research Methods

4.2. Data Collection Methods

4.3. Sampling Techniques and Sample Sizes

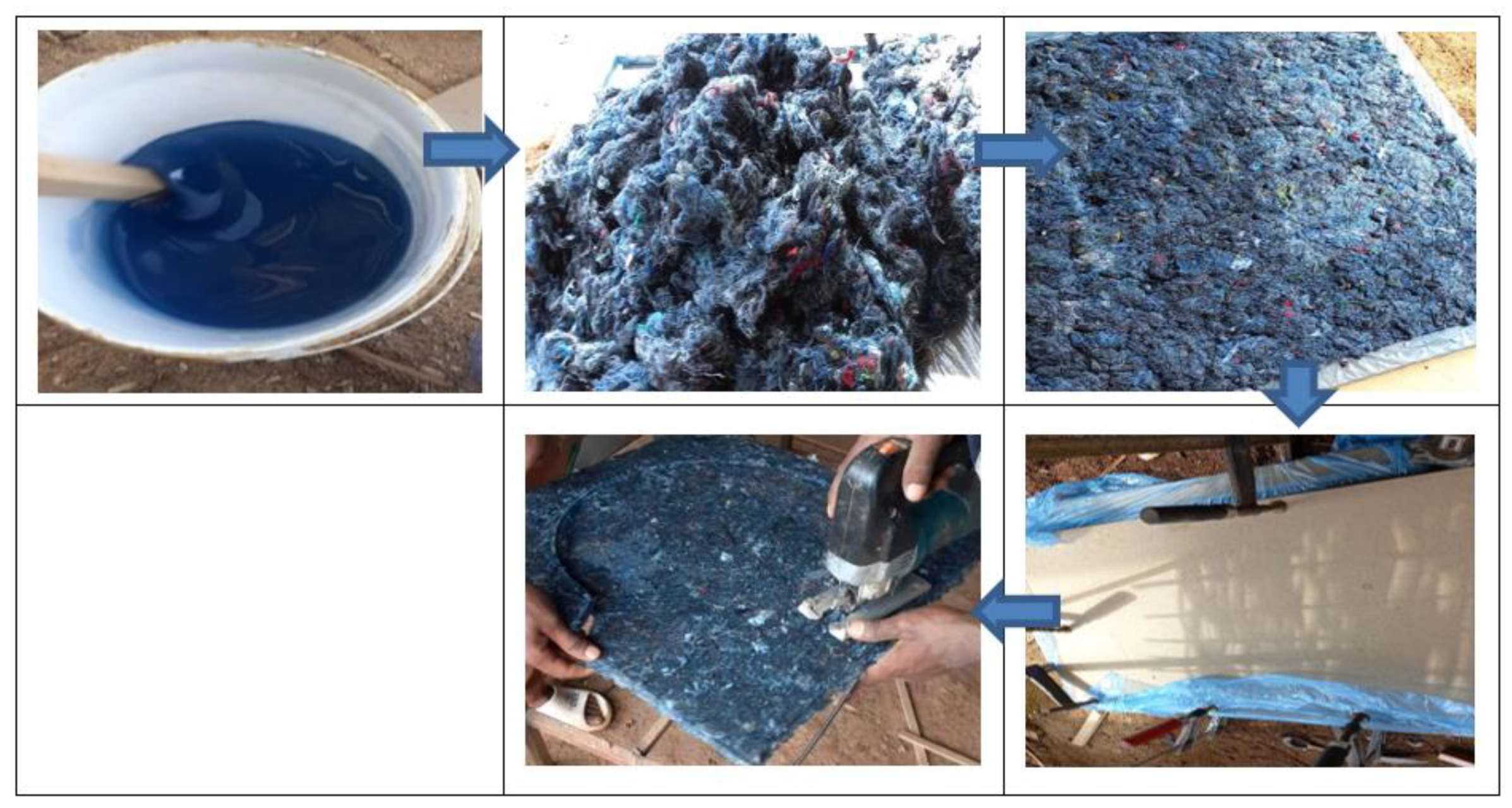

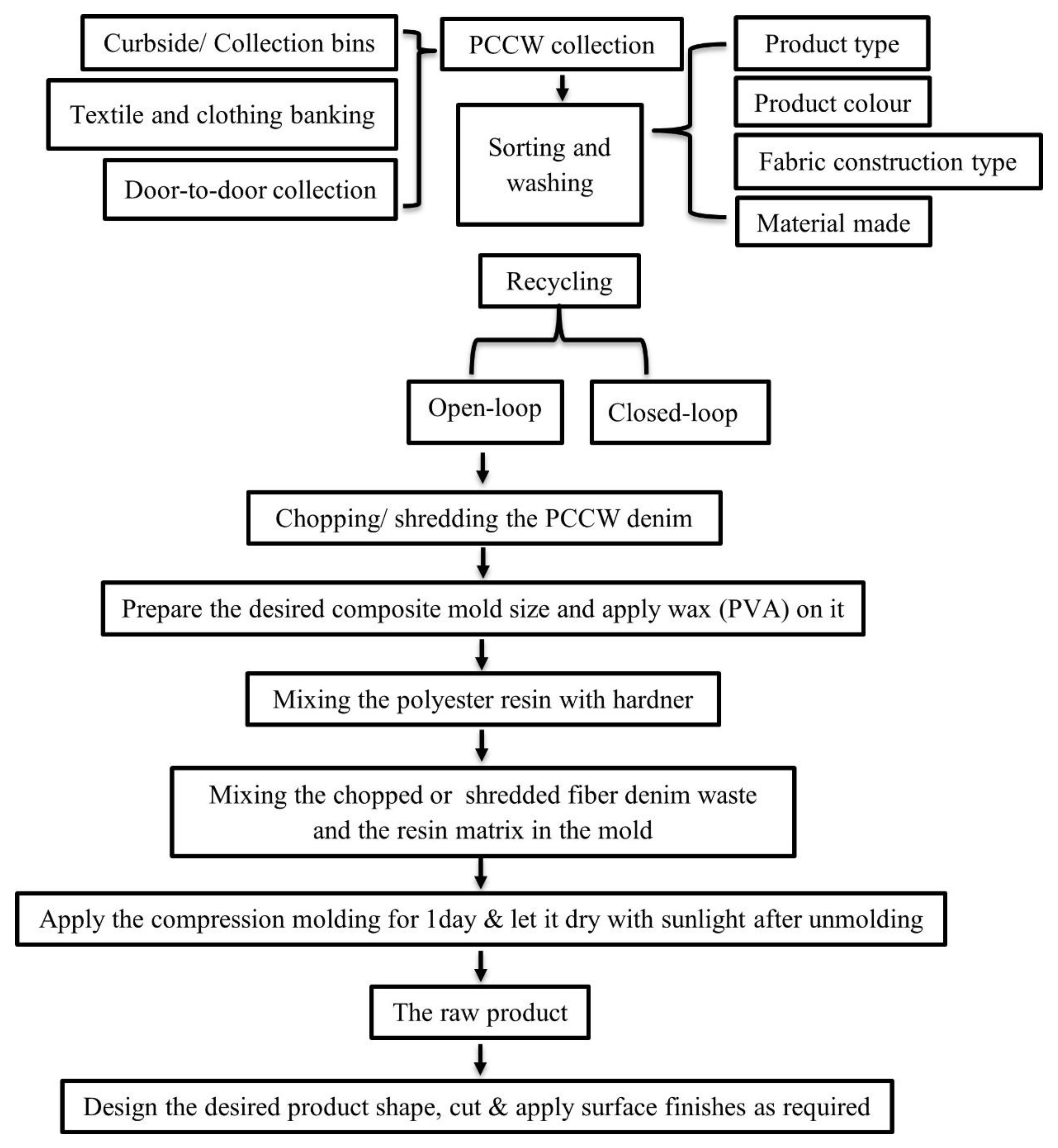

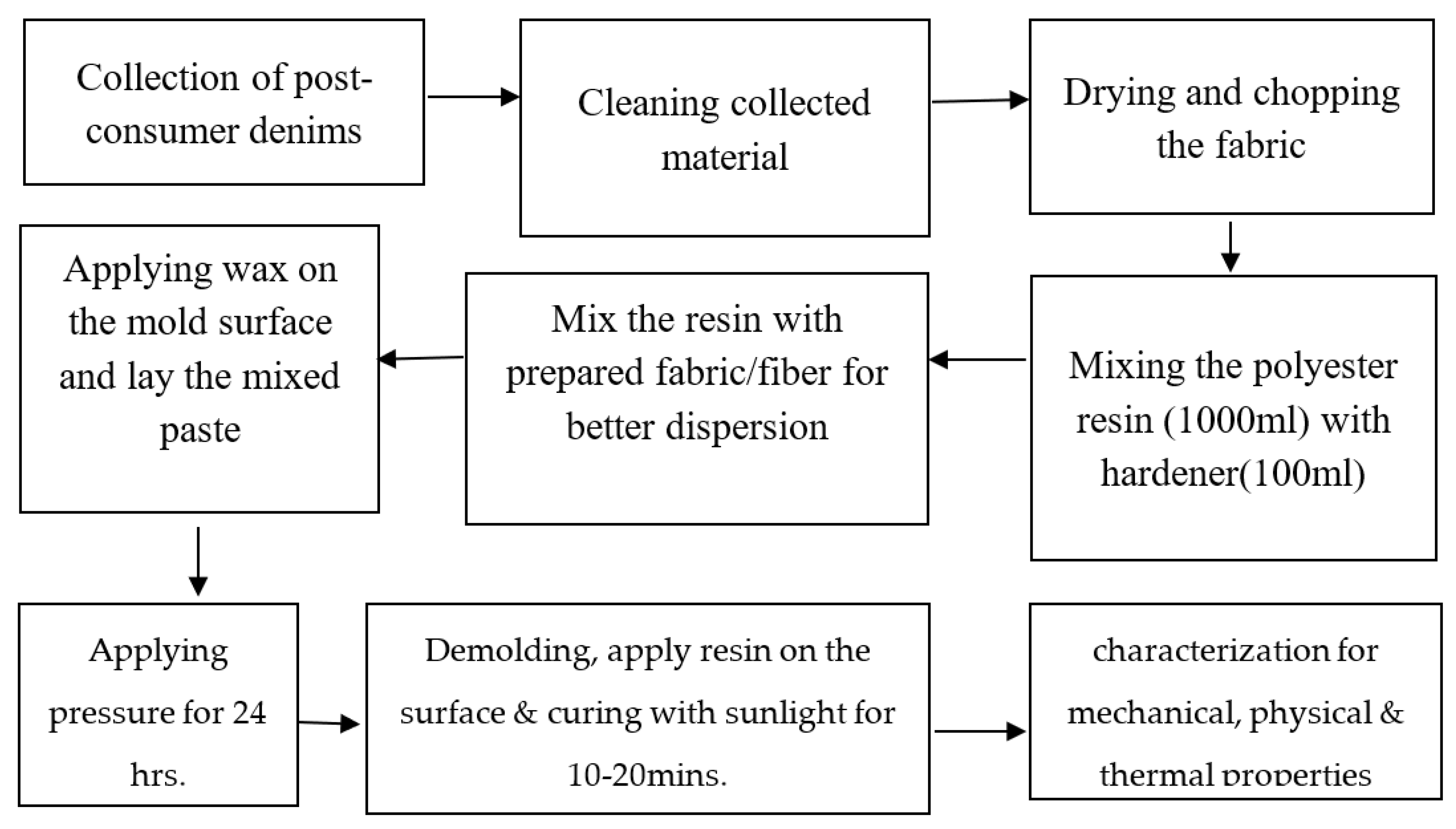

4.4. Composite Manufacturing Procedures

4.5. Characterization of Composite Products

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaimal, M.M.; Sajoy, P.B. Circular Economy–A Paradigm Shift for Sustainable Development. Perspectives on Business Management & Economics 2020, 1, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pui-Yan Ho, H.; Choi, T.M. A Five-R analysis for sustainable fashion supply chain management in Hong Kong: a case analysis. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 2012, 16, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowoshegbe, A.O.; Emmanuel, U.; Gina, A. Sustainability and triple bottom line: An overview of two interrelated concepts. Igbinedion University Journal of Accounting 2016, 2, 88–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of industrial and production engineering 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.J.D.; Bastein, T.; Tukker, A. Business model innovation for resource-efficiency, circularity and cleaner production: What 143 cases tell us. Ecological Economics 2019, 155, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cyamani, A. Disrupting the Linear Textile Model at the Community Scale. In State-of-the-Art Upcycling Research and Practice; Lecture Notes in Production, Engineering; Sung, K., Singh, J., Bridgens, B., Eds.; Springer: Switzerland, 2021; pp. 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, P.S.; Campos, L.M. Practices for garment industry’s post-consumer textile waste management in the circular economy context: an analysis on literature. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management 2021, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, P.; Dissanayke, D.G.K.; Abeysooriya, R.P.; Bulathgama, B.H.N. Addressing post-consumer textile waste in developing economies. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2022, 113, 1887–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behavior: A comparative study. International journal of consumer studies 2012, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domina, T.; Koch, K. Consumer reuse and recycling of post-consumer textile waste. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 1999, 3, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichart, E. (Washington, USA); Drew, D. (Washington, USA). By the numbers: The economic, social and environmental impacts of “fast fashion”. 2019.

- Hoang, N.L. An Analysis of the Effects of Donating Secondhand Clothing to Sub-Saharan Africa. Bachelor of Arts, Scripps College: California, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Geremew, S.; Tizazu, B. Developing Anthropometric Standards for Ethiopian Clothing Design. International journal on recent & innovative trend in technology 2017, 3, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Motamed, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Naebe, M. Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 718, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, K. An overview of textile and apparel business advances in Ethiopia. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 2018, 22, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Hedrich, S.; Russo, B. East Africa: The next hub for apparel sourcing; McKinsey & Company, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, P.; Nadathur, G.T.; Jose, S. Upcycled and low-cost sustainable business for value-added textiles and fashion. In Circular Economy in Textiles and Apparel processing, manufacturing and design; Subramanian Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M.A.; Omar, E.D.; Baharum, N.A. A review on sample size determination for Cronbach’s alpha test: a simple guide for researchers. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences 2018, 25, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajila, K.O. Analysis of post-consumer solid textile waste management among households in Oyo State of Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Protection 2019, 10, 1419–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žurga, Z.; Hladnik, A.; Forte Tavčer, P. Environmentally sustainable apparel acquisition and disposal behaviors among Slovenian consumers. Autex Research Journal 2015, 15, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nencková, L.; Pecáková, I.; Šauer, P. Disposal behavior of Czech consumers towards textile products. Waste Management 2020, 106, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, M.A. Effect of Household Solid Waste Management on Environmental Sanitation in Hargeisa, Somaliland. International Journal of Environmental Protection and Policy 2021, 9, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Elias, E. Domestic solid waste management and its environmental impacts in Addis Ababa city. Journal of Environment and Waste Management 2017, 4, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, J.M.; Schenck, C.J.; Volschenk, L.; Blaauw, P.F.; Grobler, L. Household waste management practices and challenges in a rural remote town in the Hantam Municipality in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todor, M.P.; Kiss, I.; Cioata, V.G. Development of fabric-reinforced polymer matrix composites using bio-based components from post-consumer textile waste. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 45, 4150–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükaslan, E.; Jevsnik, S.; Kaloğlu, F.J.M.J. o. P.; Sciences, A. A sustainable approach to collect post-consumer textile waste in developing countries. Marmara Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2015, 27, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Carrasco-Gallego, R.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Developing a national programme for textiles and clothing recovery. Waste Management & Research 2018, 36, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey, D.J. How to interpret a correlation coefficient r. Statistics for dummies 2016, 26, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Achim, N.; Abd Razak, N. Assinteressing Intercultural Communication Competency and Health Communication. Proceedings of International Conference of Social and Humanities, IPEDR 2012; Volume 57, pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Dickey, M.D.; Wang, H. Wicking–polarization-induced water cluster size effect on triboelectric evaporation textiles. Advanced Materials 2021, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowaluk, G. Machining processes for wood-based composite materials. In Machining Technology for Composite Materials; Hocheng H.; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 412–425. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, G.R. Feasibility analysis for the new venture nonprofit enterprise. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship 2017, 20, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aissaoui, O.; El Alami El Madani, Y.; Oughdir, L.; Dakkak, A.; El Allioui, Y. A multiple linear regression-based approach to predict student performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development, Morocco, 8–11 July 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Ge, S.; Fan, W. Development of 3D needled composite from denim waste and polypropylene fibers for structural applications. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 314, 125583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Jawaid, M.; Md Shah, A.U.; Safri, S.N.A. Mechanical Properties of Flax/Kenaf Hybrid Composites. In Structural Health Monitoring System for Synthetic, Hybrid and Natural Fiber Composites. Composites Science and Technology; Jawaid, M., Hamdan, A., Hameed Sultan, M.T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

| Model variables | Tolerance | VIF |

| Gender | .702 | 1.425 |

| Age | .523 | 1.912 |

| Educational level | .400 | 2.501 |

| Income level | .588 | 1.700 |

| Religion | .842 | 1.188 |

| Geographical area | .659 | 1.517 |

| Attitude | .592 | 1.690 |

| PSE | .745 | 1.343 |

| Correlations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | Educational level | Income level | Religion | Geographical area | Attitude | PSE | PCCW | ||

| Gender | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .863 | .951 | .872 | .916 | .907 | .745 | .785 | .843 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .001 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Age | Pearson Correlation | .863 | 1 | .867 | .94 | .857 | .786 | .915 | .774 | .861 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Educational level | Pearson Correlation | .951 | .867 | 1 | .858 | .899 | .770 | .821 | .801 | .588 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Income level | Pearson Correlation | .872 | .94 | .858 | 1 | .695 | .737 | .806 | .834 | .904 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Religion | Pearson Correlation | .916 | .857 | .899 | .695 | 1 | .656 | .673 | .754 | .334 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .007 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Geographical area | Pearson Correlation | .907 | .786 | .770 | .737 | .656 | 1 | .77 | .883 | .788 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| Attitude | Pearson Correlation | .745 | .915 | .821 | .806 | .673 | .776 | 1 | .888 | .780 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| PSE | Pearson Correlation | .785 | .774 | .801 | .834 | .754 | .883 | .888 | 1 | .866 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| PCCW | Pearson Correlation | .843 | .861 | .588 | .904 | .334 | .788 | .780 | .866 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .007 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | 474 | |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | ||||||||||

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | ||||||||||

| Variables | Types of variances | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Sig. |

| Gender | Between Groups | 10.017 | 12 | .835 | 3.983 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 96.616 | 461 | .210 | |||

| Total | 106.633 | 473 | ||||

| Age | Between Groups | 66.203 | 12 | 5.517 | 3.028 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 839.915 | 461 | 1.822 | |||

| Total | 906.118 | 473 | ||||

| Educational level | Between Groups | 125.585 | 12 | 10.465 | 5.709 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 845.039 | 461 | 1.833 | |||

| Total | 970.624 | 473 | ||||

| Income level | Between Groups | 49.487 | 12 | 4.124 | 3.580 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 531.004 | 461 | 1.152 | |||

| Total | 580.492 | 473 | ||||

| Religion | Between Groups | 21.857 | 12 | 1.821 | 1.226 | .262 |

| Within Groups | 684.846 | 461 | 1.486 | |||

| Total | 706.703 | 473 | ||||

| Geographical area | Between Groups | 10.008 | 12 | .834 | 4.714 | .000 |

| With in Groups | 81.553 | 461 | .177 | |||

| Total | 91.561 | 473 | ||||

| Attitude | Between Groups | 2.549 | 12 | .212 | 2.051 | .019 |

| Within Groups | 47.749 | 461 | .104 | |||

| Total | 50.298 | 473 | ||||

| PSE | Between Groups | 30.090 | 12 | 2.507 | 4.551 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 254.011 | 461 | .551 | |||

| Total | 284.101 | 473 | .000 |

| Coefficients | |||||

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | T | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 2.158 | .163 | 13.271 | .000 | |

| Gender | .033 | .030 | .254 | 4.072 | .000 |

| Age | .076 | .012 | .379 | 5.361 | .001 |

| Educational level | .082 | .013 | .411 | 6.164 | .000 |

| Income level | .089 | .014 | .537 | 7.666 | .000 |

| Religion | -.016 | .011 | -.367 | 4.463 | .054 |

| Geographical area | .201 | .034 | .309 | 5.942 | .000 |

| Attitude | .160 | .048 | .182 | 3.325 | .001 |

| PSE | .025 | .018 | .514 | 3.282 | .003 |

| Dependent Variable: PCCW | |||||

| Material costs | Quantity | Unit cost (USD) | Total cost per product(USD) | |

| Product 1 | Product 2 | |||

| PCCW jeans | 2 Pcs | 2 Pcs | 0.94 | 1.88 |

| Unsaturated polyester(L) | 1 | 1 | 1.89 | 1.89 |

| Hardener (ml) | 100 | 100 | 0.38 | 38 |

| PVA (gm) | 25 | 25 | 0.47 | 11.75 |

| Wooden mica sheet (45 cm diameter) | 2 Pcs | 2 Pcs | 0.47 | 0.94 |

| No. | Justification | Type and model no. | Origin |

| 1 | PCCW (Denim waste) | Cotton made | Ethiopia |

| 2 | Unsaturated polyester resin | GP resin 1003 | UAE |

| 3 | Wax | PVA (Polyvinyl alcohol) | China |

| 4 | Hardener | Cycloaliphatic hardener | India |

| 5 | Detergent | Omo detergent powder (500g) | Nigeria |

| 6 | Scissors | Fabric scissor (tailoring scissor) | China |

| 7 | Mixer | Manual mixer (wooden material) | Ethiopia |

| 8 | Manual molding material | Morsa | China |

| 9 | MDF | Melamine MDF board | Ethiopia |

| 10 | Grinder | GWS 600 angle grinder | India |

| 11 | Jig saw cutter | Makita (450W) | USA |

| 12 | Universal testing machine | WAW-600D | China |

| 13 | Differential Scanning Calorimeter | DSC-100 | China |

| 14 | Electronic balance | METTLER TOLEDO | China |

| 15 | Shredding machine | XRD30 OXRD | China |

| 16 | Wooden mica sheet | Sunmica | India |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).