1. Introduction

Anthracene (hereinafter referred to as

"AN") is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon that is used as an

insecticide, a gasoline stabilizer, a triplet sensitizer, and a quenching

agent. As AN is generated unintentionally by the burning of the fossil fuels

such as petroleum and coal, it is discharged into the environment from numerous

emission sources, including automobiles, incinerators and factories (Shen et

al. 2011, Aydin et al. 2014, Satri et al. 2017, Lin et al.

2019, Thang et al. 2019). Accordingly, AN has been detected in air,

water, and other environmental media around the world (Zhou et al. 2013,

Obist et al. 2015, Subramanian et al. 2015, Adekulea et al.

2017, Li et al. 2017, Wang et al. 2017, Pratt et al. 2018,

Hazarika et al. 2019, Yang et al. 2019). In an evaluation by the

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), AN is categorized as a

compound that cannot be evaluated with respect to carcinogenicity in humans

(Group 3) in 2010 (IARC 2021). However, due to its persistence, accumulation in

ecosystems, and toxicity, it was included in the first list of substances of

very high concern (SVHC) released by the European Chemicals Agency in October

2008, and it can be considered a harmful chemical substance of note (ECHA

2021). Accurately calculating the health risk of AN requires collecting

information on exposure level; accumulating data on concentration in

environmental media including water, air, and foods; and considering the

substance's environmental dynamics.

The authors conducted a study on vegetables,

targeting the radish Raphanus sativus. This vegetable of the Brassicaceae

family is native to Europe. It can be harvested around one month after sowing

under temperature conditions of approximately 20 °C . In large specimens,

leaves grow to a height of approximately 30 cm and the root grows into a red

sphere with a diameter of approximately 3 cm. The radish was selected for this

study as the time until harvest is short and management of growth is relatively

easy. The study attempted to understand the absorption and concentration

properties of the radish, including the degree to which AN in contaminated soil

is absorbed by the radish and how AN is transported and accumulates within the

organism.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Overview of the study

Studies were conducted to grow radishes from the

sowing stage in soil contaminated with AN, and to grow radishes in soil

contaminated with AN following maturity (27 days after sowing). Experiments

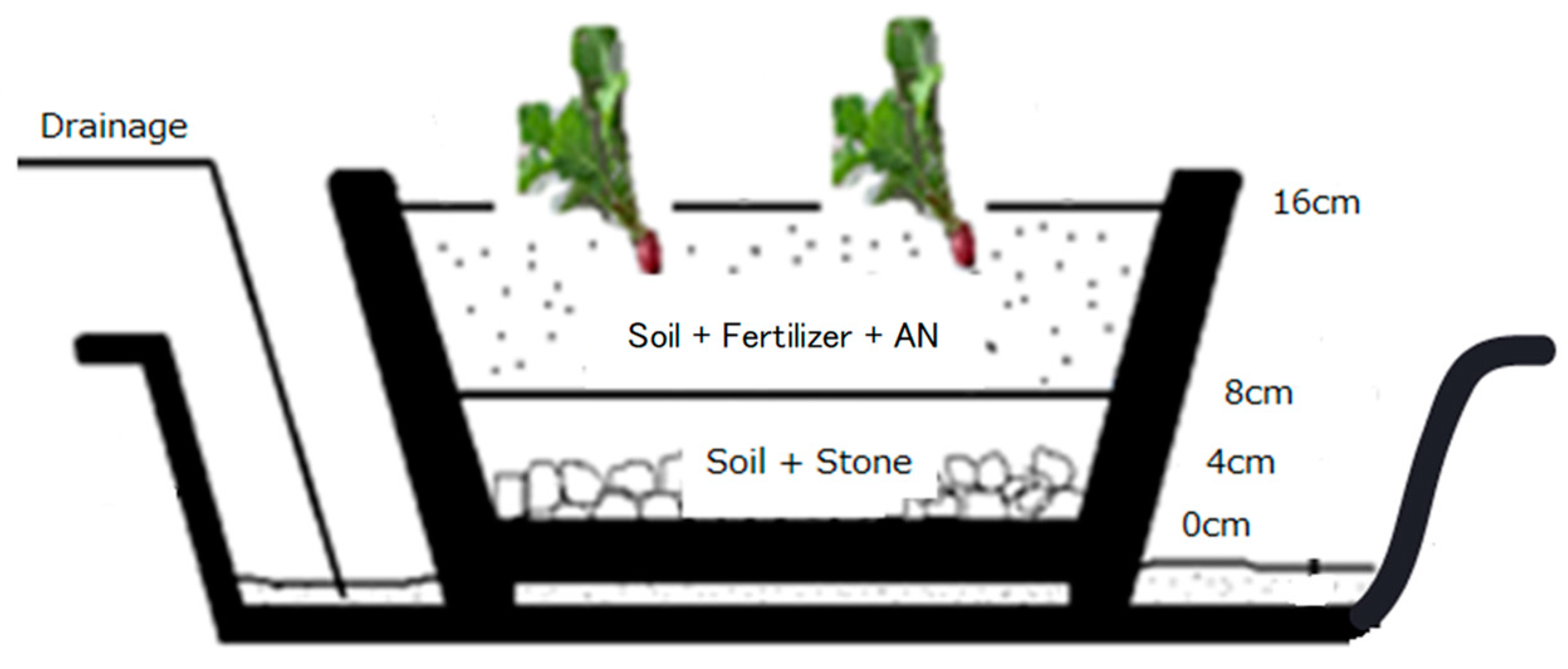

were performed using four types of planters, as shown in

Table 1. The study of growth in contaminated

soil from sowing onward was conducted using planters P1 and P2 from June 3 to

July 1, 2019, and using planter P3 from July 2 to July 30, 2019. The study of

growth in contaminated soil from maturity onward was conducted using planter P4

from June 1 to July 22, 2019. The average daily outdoor air temperature during

the growing period, as reported by the Japan Meteorological Agency, was 24.0 °C

for P1 and P2, 26.7 °C for P3, and 25.3 °C for P4. The average indoor

temperature in the growing room was 26.7 °C for the experiment with P1 and P2,

28.2 °C for P3, and 27.6 °C for P4.

2.2. Radish growth

The radishes were grown in planters in a room with

abundant sunlight from windows. The planters used had dimensions of 45 cm in

width, 30 cm in length, and 18 cm in depth. As

Figure

1 indicates, approximately 400 g of potting stones were laid evenly on

the bottom of each planter, which was then covered with garden-use potting soil

to a depth of approximately 8 cm (approximately 400 g). The planters were

further prepared using potting soil mixed with fertilizer and AN, with the soil

laid to a depth of approximately 16 cm. The mass of the potting soil was

approximately 1600 g, the fertilizer approximately 15 g, and the AN additive

0.05 g in P1, 0.10 g in P2, and 0.20 g in P3. AN was not added to P4. After the

planters were readied, approximately 2 L of water was sprinkled into the

planters, and approximately sixty radish seeds were buried in two rows. The

radishes were grown with 300 mL to 500 mL of water sprinkled nearly every day.

When the air temperature was high, windows were opened to adjust the temperature

inside the growing room, except when raining and windy. In P4, which was used

to study growth in contaminated soil after maturity, a suspension of AN (1.6 mg

to 4.5 mg of AN added to approximately 20 mL of pure water) was sprayed water

round the roots 27 days after sowing, after which growth was continued.

2.3. Sampling of specimens

For the radishes grown in contaminated soil from

sowing onward, radishes and soil were collected five times in P1, P2, and P3:

immediately after sowing and at 6 days, 14 days, 21 days, and 28 days after

sowing. In these, 20 to 27 plant seeds were collected 6 days after, 10 to 17

plants were collected 14 days after, 5 to 6 plants were collected 21 days

after, and 3 plants were collected 28 days after sowing. Soil specimens with a

diameter of about 3 cm and a depth of about 3 cm were collected from five

locations (the center of the planter and near the four corners). The specimens

were collected and mixed to create test samples.

In P4, which was used to study growth in

contaminated soil after maturity, plants and soil were collected six times:

before application of AN and 1 day, 4 days, 11 days, 19 days, and 24 days after

application (27 days, 28 days, 31 days, 38 days, 46 days, and 51 days after sowing).

One radish was collected on each of the days. Soil with a diameter of about 5

cm and depth of about 5 cm surrounding the collected radish was collected and

mixed to prepare a test sample.

2.4. Analysis

The radish samples were thoroughly washed with water,

wiped with the paper towel, and weighed using an electronic scale. Each sample

was then cut into pieces several millimeters in size using scissors. The pieces

were placed in a cylindrical cellulose filter paper (Whatman, UK) and were

weighed again to assess the exact sample mass for ultrasonic extraction using

hexane. As the radishes 6 days after sowing in P1, P2, and P3 were small and

could not be divided into roots, stems, and leaves, the 20- to 27-day plants

were combined, chopped into pieces several millimeters in size, and mixed,

after which a portion of the sample was placed in the cylindrical cellulose

filter paper and weighed. As the plants in P1, P2, and P3 on days other than 6

days after sowing and the plants in P4 had grown large, these were separated

into roots, stems, and leaves, each of which was chopped into pieces several

millimeters in size and mixed thoroughly. A portion of the samples of each part

was placed in cylindrical cellulose filter papers and weighed. The soil samples

were also placed in cylindrical cellulose filter papers and weighed.

The cylindrical cellulose filter papers containing

the samples were set in 260 mL bottles into which 150 mL of hexane (for

pesticide residues and polychlorinated biphenyl analysis from Wako Pure Chemical

Industries, Ltd.) was added, after which ultrasonic extraction was performed

for 15 minutes. Anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to the extract liquid. After

dehydration for 30 minutes, the solution was concentrated to approximately 2 mL

using a rotary evaporator. This concentrated solution was combined with the

solution obtained by rinsing the rotary evaporator device with hexane;

anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to the combination and the mixture was

dehydrated for 30 minutes. The dehydrated solution was filtered by a syringe

filter (Whatman Puradisc 25 TF; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway NJ, USA)

and was concentrated to 1.5 mL under a stream of nitrogen. Next, 0.2 mL of

internal standards solution (100-fold diluted solution of hexane, 3 Internal

Standards Mixture Solution from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) was added.

The mixture was accurately adjusted to 2.0 mL using hexane, and a sample

solution for GC/MS measurement was prepared.

The GC/MS used for measurement was the 5975B inert

XL E/CI MSD (Agilent Technologies). The capillary column used was the HP-5MS

(30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The injection port temperature was 250 °C, with

splitless injection used. The injection volume was 2 μL; the column temperature

rise condition was 70 °C (1.5 min) → 20 °C/min → 180 °C (0 min) → 5 °C/min →

290 °C (10 min). The carrier gas was helium and the interface temperature was

230 °C. A mass spectrometer was used to perform measurements under electron

impact ionization mode conditions of 70 eV ionizing voltage. For AN, mass

numbers 178.1 and 176.1 were selected, and for the internal standards substance

AN-d10, mass numbers 188.2 and 189.2 were selected for use in qualitative

evaluation. The quantitative evaluation was performed using the internal calibration

curve method, using the mass numbers with the highest sensitivity (178.1 for AN

and 188.2 for AN-d10). Preparations were produced through mixing and through

dilution with hexane as appropriate, using Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Mix (CRM48905; Sigma-Aldrich) for AN and 3 Internal Standards Mixture Solution

(091-05791; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) for AN-d10.

3. Findings and considerations

3.1. Results for radishes grown from sowing onward in soil contaminated with anthracene

Table 2 shows

the detailed results of the study (P1, P2, and P3) in which radishes were grown

in AN-contaminated soil from sowing onward.

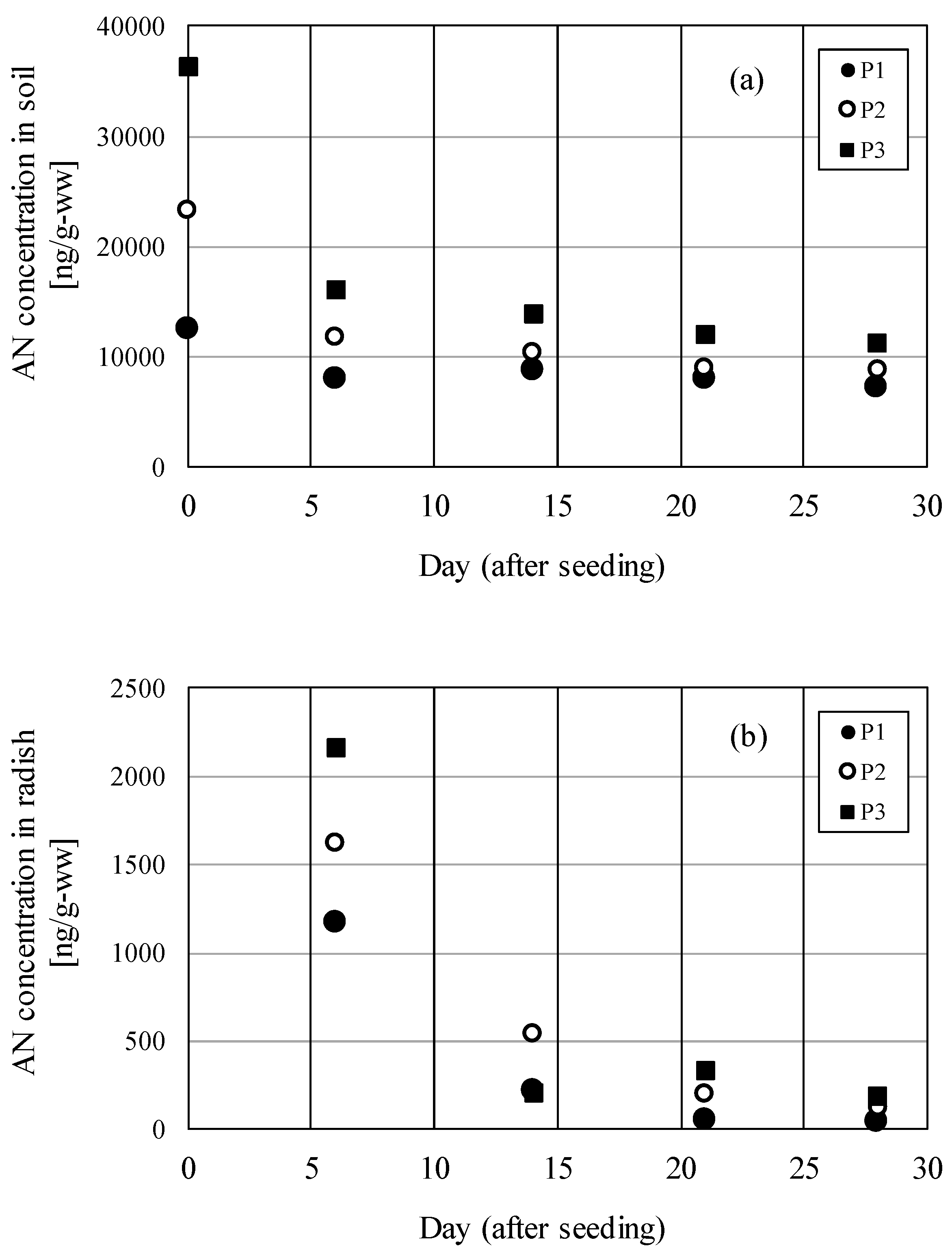

Figure

2(a) shows the AN concentration in the contaminated soil and

Figure 2(b) shows the AN concentration in

radishes over time. Conditions for P1 and P2 were an average outdoor air

temperature of 24.0 °C during the growing period, with 0.05g and 0.10 g of AN,

respectively, added to the topsoil in the planters (approximately 1600 g of

potting soil and approximately 15 g of fertilizer). Conditions for P3 were an

average outdoor air temperature of 26.7 °C during the growing period, with 0.20

g of AN added. The AN concentration in collected soil that had been sprinkled

with approximately 2 L of water immediately after sowing was 12,500 ng/g-ww in

P1, 23,300 ng/g-ww in P2, and 36,300 ng/g-ww in P3. As shown by the figure, the

concentration subsequently decreased exponentially. The AN concentration in the

soil 28 days after sowing was 7140 ng/g-ww in P1, 8770 ng/g-ww in P2, and

11,300 ng/g-ww in P3. The AN concentration in radishes 6 days after sowing was

1170 ng/g-ww in P1, 1620 ng/g-ww in P2, and 2160 ng/g-ww in P3. The

concentration subsequently decreased exponentially 28 days after sowing to 38.2

ng/g-ww in P1, 122 ng/g-ww in P2, and 189 ng/g-ww in P3.

3.2. Results for radishes grown after maturity in soil contaminated with anthracene

Table 3 shows the detailed results of the study (P4) in which radishes were grown in AN-contaminated soil after maturity. The conditions were an average outdoor air temperature of 25.3 °C during the growing period, with AN not added at the time of sowing, and a suspension of AN sprinkled around the roots of the radishes 27 days after sowing. Concentration in the soil was highest 4 days after application of AN (31 days after sowing), at 22,100 ng/g-ww, and was lowest 11 days after application of AN (38 days after sowing), at 5670 ng/g-ww. Although there were some fluctuations due to AN suspensions of differing content being sprinkled around the roots, the concentration generally showed a decreasing trend.

In the same manner as the concentration in the soil, the concentration in the radishes tended to decrease over time following the addition of AN, with the highest concentration 4 days after application of AN, at 2270 ng/g-ww, and the lowest concentration 24 days after application of AN, at 342 ng/g-ww. Tendencies in concentration differed by part of the radish. The concentration in roots and stems was highest 1 day after application of AN, at 3470 ng/g-ww and 230 ng/g-ww, respectively. Concentration in the leaves was highest 4 days after application of AN, at 5750 ng/g-ww. Concentration was lowest in the roots 4 days after application of AN, at 228 ng/g-ww, and in the stems and leaves 24 days after application of AN, at 39.5 ng/g-ww and 55.9 ng/g-ww, respectively.

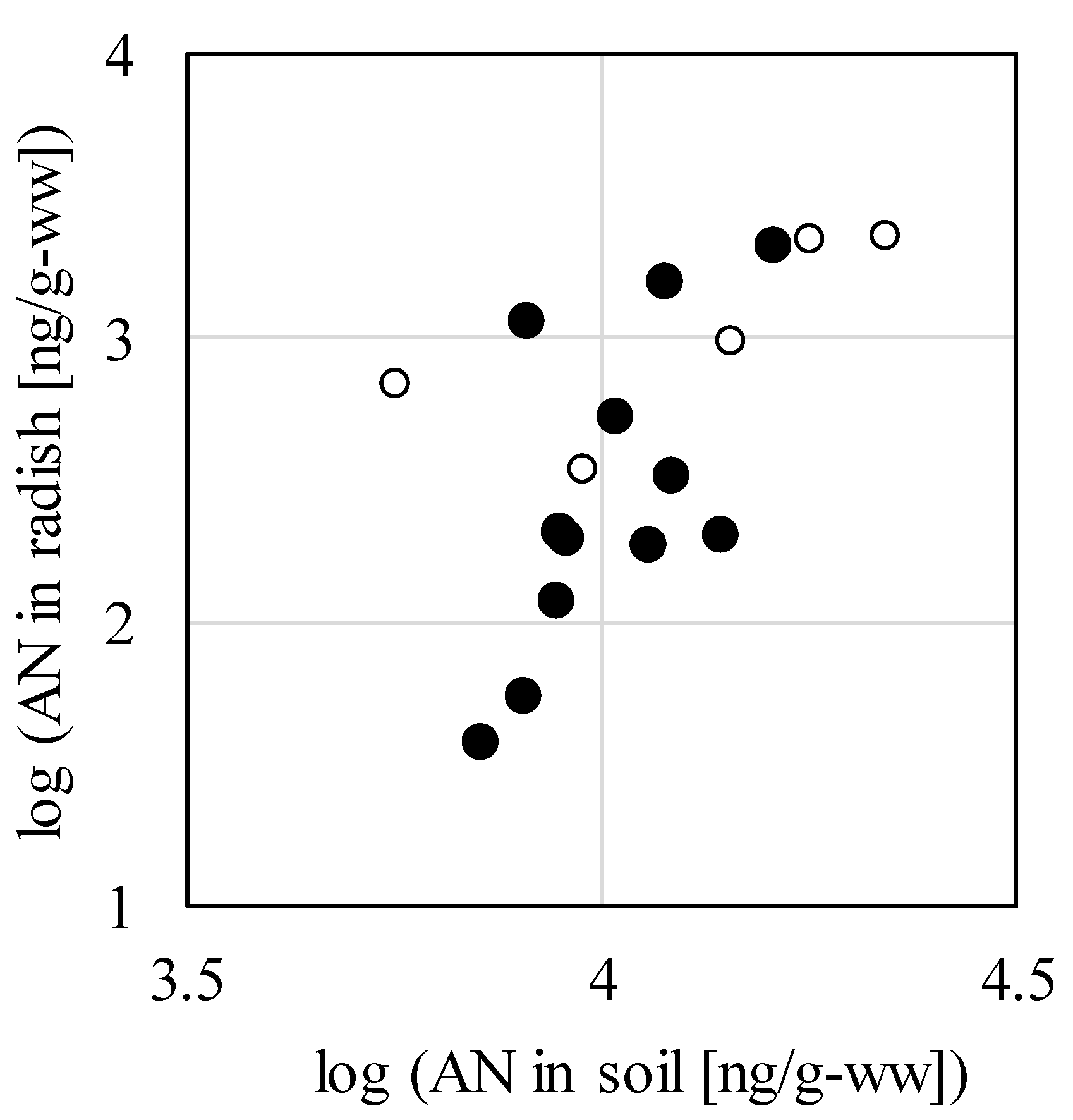

3.3. Relationship between anthracene concentration in soil and concentration in radishes

Figure 3 shows the relationship between AN concentration in soil and concentration in radishes in the study. In the figure, "●" indicates the common logarithmic values of the detected concentration in both soil and radishes in P1, P2, and P3, and "○" indicates the values in P4. While P1, P2, and P3 were used in a survey to grow plants from sowing onward in AN-contaminated soil and P4 was used in a methodologically different survey to grow plants after maturity in AN-contaminated soil, positive correlations were observed in each study. It is inferred that the greater the degree of soil contamination, the greater the effect on the amount of AN assimilated by the radishes.

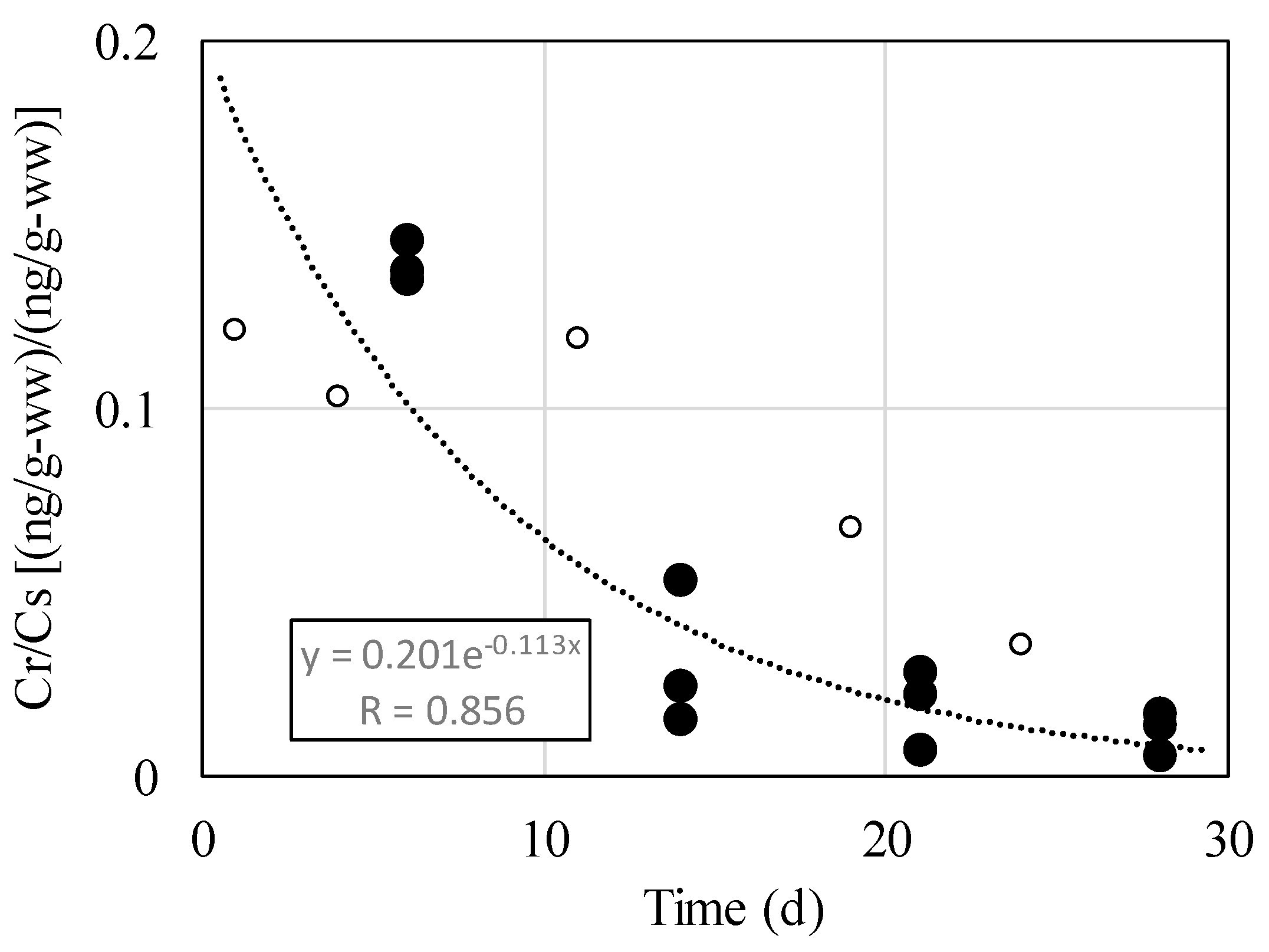

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the number of days since application of AN and Cr/Cs. In the figure, "●" indicates results for radishes grown in contaminated soil from sowing onward in P1, P2, and P3. The relationship between the number of days elapsed after application of AN, x, and the concentration ratio, y, can be expressed as y = 0.201×e−0.113x. The correlation coefficient was 0.856, with the concentration ratio decreasing exponentially. In P4, "〇" indicates results for growth in contaminated soil after maturity. Despite the different growing conditions, the results were generally close to the expression. From this, it is thought that concentration ratio is affected by time in contact with AN.

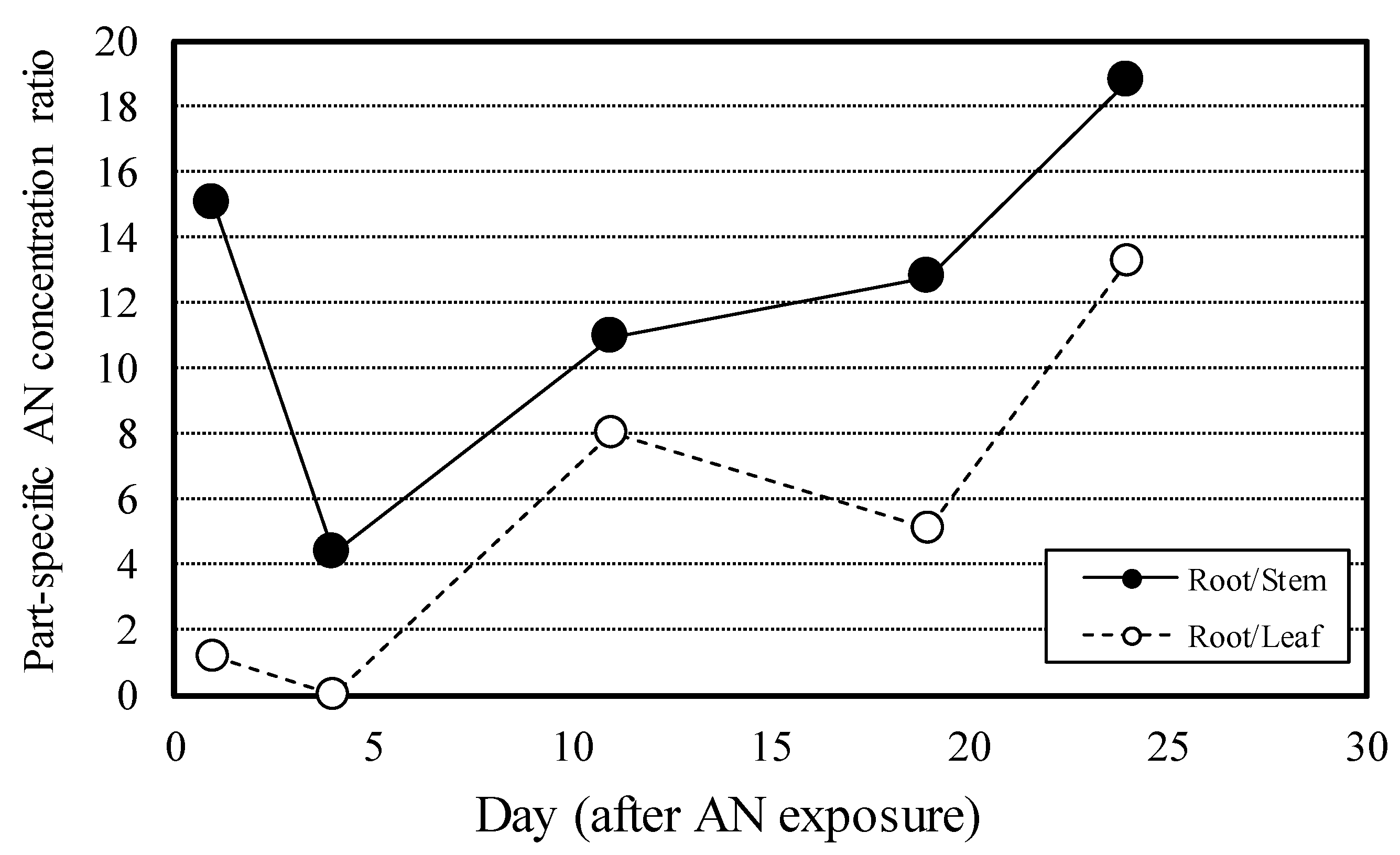

3.4. Concentration ratio and content composition ratio of anthracene by radish part

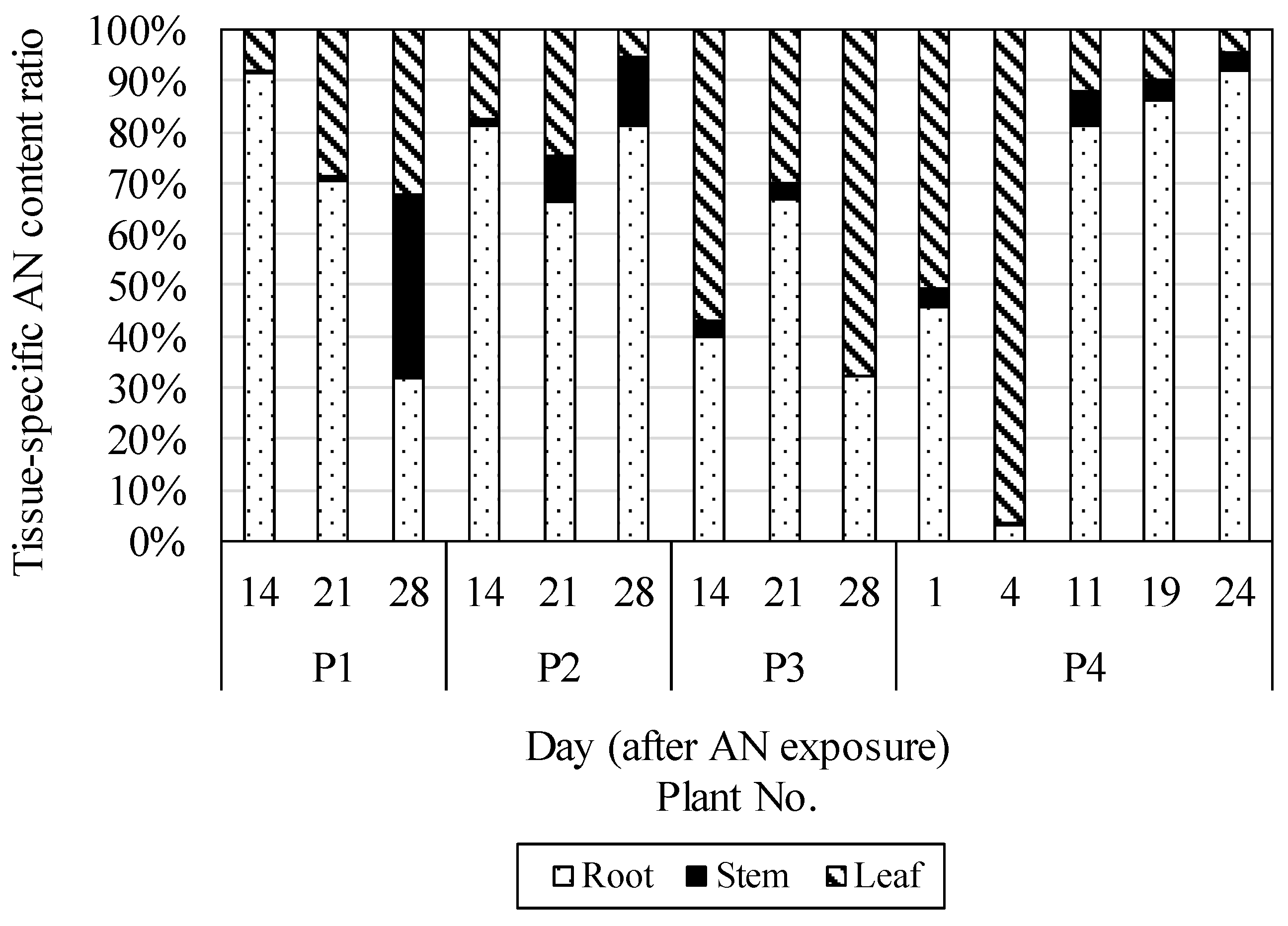

Figure 5 shows the change over time in the concentration ratio of AN by radish part in P4. The concentration ratio in roots and stems was high 1 day after AN application at 15.1, but declined sharply 4 days after application to 4.4. It subsequently increased to 18.8 at 24 days after application of AN. The concentration ratio in roots and leaves was 1.2 at 1 day after AN application and it declined 4 days after application to 0.04 and subsequently rose (with fluctuations) to reach 13.2 at 24 days after application.

Figure 6 shows the change over time in the content composition ratio of AN by radish part in planters P1 to P4. The median AN content ratio in roots was 68.4%, with a range of 2.9–92.0%. The median AN content ratio in the stems was 3.3%, with a range of 0.3–35.8%. The median AN content ratio in the leaves was 26.8%, with a range of 4.5–96.3%. The median was highest in the roots, followed by the leaves and then by the stems. No characteristic tendencies were observed in the fluctuations in change over time for each content ratio. The moisture content of the radishes by part under dehydrating conditions of 105 °C and the organic matter content of radishes by part under combustion conditions of 650 °C, obtained in separate studies, yielded average moisture contents of 88.1%, 93.2%, and 94.4% and average organic matter contents of 87.1%, 81.9%, and 79.6% for roots, leaves, and stems, respectively. Taking into consideration that AN is a hydrophobic substance with a logKow value of 4.45 (Hansh

et al. 1995) as well as the water content and organic matter content of radishes by part, it is thought that AN in the soil is absorbed through the roots to circulate within the organism, and is preferentially distributed and accumulated in the roots and leaves, which have high organic matter content.

4. Conclusions

The present study aims at understanding the absorption and concentration of anthracene (AN) in the garden radish. Here, empirical data for AN absorption and accumulation in the radish Raphanus sativus were analyzed and considered their implications. Studies were conducted to grow radishes from the sowing stage in soil contaminated with AN, and to grow radishes in soil contaminated with AN following maturity (27 days after sowing). In both experimental conditions, the relationship between AN concentrations in soil and radishes were positive. Radishes absorbed greater AN quantities the higher its concentration in soil. The concentration ratio (Cr/Cs) decreased exponentially with days since AN application. This suggests that the degree of AN absorbed by radishes is affected by exposure time. According to the results for the time series of part-specific AN concentration ratios and AN contents, it seems that AN in the soil were taken up through the roots to circulate within the organism, and were preferentially distributed and accumulated in the roots and leaves, which have organic matter content.

References

- Adekunlea, A.S. , Oyekunlea, J.A.O., Ojoa, O.S., Maxakatob, N.W., Olutonac, G.O., and Obisesanaa, O.R. “Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon levels of groundwater in Ife north local government area of Osun state. Nigeria. Toxicology Reports 2017, 4, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, Y.M. , Kara, M., Dumanoglu,Y,. Odabasi, M., and Elbir, T. “Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in ambient air of an industrial region in Turkey”. Atmospheric Environment 2014, 97, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHA (2021), Candidate List of substances of very high concern for Authorisation; ECHA, Helsinki, Finland. https://www.echa.europa.eu/candidate-list-table.

- Hansh, C. , Leo, A., and Hoekman. (1995), Exploring QSAR - Hydrophobic, Electronic, and Steric Constants, American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

- Hazarika, N. , Das, A., Kamal, V., Anwar, K., Srivastaba, A., and Jain, V.K. “Particle phase PAHs in the atmosphere of Delhi-NCR: With spatial distribution. source characterization and risk approximation. Atmospheric Environment, 2019; 200, 329–342, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231018308483. [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2021), Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–129; IARC, Lyon, France. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/agents-classified-by-the-iarc/.

- Li, J. , Li, F., and Liu, Q. “PAHs behavior in surface water and groundwater of the Yellow Riverestuary: Evidence from isotopes and hydrochemistry”. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 143–153, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653517304150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C. , Li, Y.C., Shangdiar, S., Chou, F.C., Sheu. Y.T., and Cheng, P.C. “Assessment of PM2.5and PAH content in PM2.5emitted from mobilesource gasoline-fueled vehicles in concomitant with the vehicle modeland mileages”. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 502–508, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653519305831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrist, D. , Zielinska, B., and Perlinger, J.A. “Accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) in organic and mineral soil horizons from four U.S. remote forests”. Chemosphere 2015, 134, 98–105, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653515003318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, G.C. , Herbrandson, C., Krause, M., Schmitt, C., Lippert, C.J., McMahon, C.R., and Elickson, K.M. “Measurements of gas and particle polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in air at urban. rural and near-roadway sites. Atmospheric Environment 2018, 179, 268–278, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231018301201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satri, E. , Pasti, L., Scaroni, I., Casali, P., Cavazzini, A., and Rossi, M. “Determination of n-alkanes. PAHs and nitro-PAHs in PM2.5and PM1sampled in the surroundings of a municipal waste incinerator. Atmospheric Environment 2017, 149, 12–23, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231016308913. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H. , Tao, S., Wang, R., Wang, B., Shen, G., Li, W., Su, S., Huang, Y., Wang, X., Liu, W., Li, B., and Sun, K. “Global time trends in PAH emissions from motor vehicles”. Atmospheric Environment, 2011; 45, 2067–2073, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231011000951. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A. , Kunisue, T., and Tanabe, S. “Recent status of organohalogens. heavy metals and PAHs pollution in specific locations in India. Chemosphere 2015, 137, 122–134, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653515006840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, P.Q. , Kim, S.J., Lee, S.J., Ye, J., Seo, Y.K., Baek, S.O., and Choi, S.D. “Seasonalcharacteristicsofparticulatepolycyclicaromatichydrocarbons(PAHs)inapetrochemicalandoilrefineryindustrialareaonthewestcoastofSouthKorea”. Atmospheric Environment 2019, 198, 398–406, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S135223101830774X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. , Zhou, S., Wu, S., Song, J., Shi, Y., Li, B., and Chen H. “Surface water polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in urban areas of Nanjing. China. Water Science & Technology, 2017; 76, 2150–2157, https://iwaponline.com/wst/article/76/8/2150/19239/Surface-water-polycyclic-aromatic-hydrocarbons-PAH. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. , Cheng, H, Wang, H., Drews, M., Li, S., Huang, W., Zhou, H., Chen, C.M., and Diao, X. “Comparative study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heavy metals (HMs) in corals. surrounding sediments and surface water at the Dazhou Island, China. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 157–168, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045653518321702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C. , Zhu, X., Wang, Z., Ma, X., Chen, J., Ni, Y., Wang, W.E.I.,, Mu, J.U.N., and Li, X. “Gas-Particle Partitioning of PAHs in the urban air of Dalian. China: measurements and assessments. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2013; 33, 31–51, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10406638.2012.683467. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).