1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are primarily used in the electric vehicle (EV) and power storage industries [

1,

2,

3]. Owing to the need for improved energy density and fast charging, research on anode materials other than graphite is essential. In particular, the energy density of LIB technology is currently at its limit. This problem is primarily due to the relatively low specific capacity of commercially available graphite-based negative electrodes (372 mAh g

-1) [

4]. Owing to the rapidly increasing demand for LIBs, researchers have focused on high-performance anode materials [

5,

6,

7].

As shown in

Table 1, various materials, including metal oxides and group IV elements (such as Si, Ge, and Sn), have been considered as potential high-capacity anodes.

In particular, Si- and Sn-based anode materials can store more than four moles of Li per mole of active material, which is a significant increase in capacity compared to graphite anodes (theoretical capacity of 372 mAh g

-1). However, the biggest challenge with group 14 elements is volume expansion, and numerous studies have been conducted to improve anode delamination from the copper foil after cycling [

9]. The cycle retention and processing costs of Si- and Sn-based anode materials still require further improvement [

10].

In 2021, a study proposed Pb, which has not received much attention because of its toxic nature, as an anode material [

11,

12]. Several studies have been conducted on this topic because of lead’s affordability [

13,

14,

15,

16]. A volume expansion problem similar to that of Si was observed in Pb (233%). Carbon was used to suppress volume expansion, and an easy synthesis method was introduced through a high-energy ball milling (HEBM) process. Inspired by the above-mentioned studies, we utilized Ge as an anode material. Ge, another group 14 element, has not received any serious consideration as a new anode material for Li-ion batteries because of its high cost. Recently, Ge has garnered significant interest due to its impressive characteristics, which include a high theoretical capacity of 1624 mAh g

-1, excellent electronic conductivity, and ionic diffusivity. Despite the relatively high cost of Ge, these attributes make Ge-based materials a promising choice for anodes in high-power LIBs [

17,

18,

19,

20].

In this study, we synthesized a Ge/GeO2/C composite anode material (Ge@GeO2-C composite) for practical applications via HEBM. The exceptional chemical and physical properties of Ge@GeO2-C particles were thoroughly characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses. To assess its suitability as an anode material in LIBs, the electrochemical properties of Ge@GeO2-C were evaluated using dQ/dV and galvanostatic charge-discharge procedures. Additionally, postmortem characterization was performed to enhance our understanding of the Ge@GeO2-C composite materials. Our findings offer compelling evidence that Ge@GeO2-C has significant potential for advancing high-energy-density LIBs owing to its interesting material properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation & Characterization of Ge@GeO2-C anode

Ge@GeO2-C was produced via HEBM using GeO2 (Sigma Aldrich, 99%) and Super P carbon (Timcal, C45). A stainless-steel jar containing GeO2 and Super P in a 7:3 weight ratio was assembled in an argon-filled glove box, and ball milling (SPEX 8000 M mill grinder, Spex Sample Prep Co.) was performed for 1, 3, and 5 h. Subsequently, an electrode was fabricated by applying the slurry to the copper foil current collector.

High-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) images were obtained using an ultra-corrected, energy-filtered TEM microscope (Libra 200 HT MC Cs, Carl Zeiss, Germany) at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Sample morphologies were assessed using field-emission scanning microscopy at the Korea Basic Science Institute in Daejeon (FE-SEM, S-4800, Hitachi, Japan).

The XPS analysis was conducted using a Thermo Fisher Scientific X-ray photoelectron spectrometer. The spectra were obtained using Al-Kα radiation (spot size: 200 µm), and the depth profile was collected via Ar ion beam etching. Prior to sputtering, a surface profile was collected; then the profile was collected after 30 min. The XPS analysis was performed at the Converging Materials Core Facility of Dong-Eui University.

2.2. Cell assembly and electrochemical testing

The slurry used for the electrode comprised 73% Ge@GeO2-C powder, 9% Super P carbon, and 18% polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, Solvay Olef 5130). The cast electrode foil was then dried in a convection oven at 90 °C for 12 h.

CR-2032 Li half-cells (Li metal/Ge@GeO2-C electrode) were assembled in an argon-filled glove box with oxygen and moisture levels of less than 0.1 ppm. Commercial 1 M LiPF6 in EC:DEC (1:1 vol) (10 wt% FEC added) electrolytes and a Celgard® separator were used to conduct electrochemical performance tests under a 30 °C chamber for discharge-charge cycling studies.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of Ge@GeO2-C

The HEBM method involves subjecting raw materials to forceful impact, grinding, and stirring of hard balls through the rotation or vibration of the ball mill. This crushes the bulk materials into nano- and microparticles, resulting in mechanical alloying. This method has gained popularity in industry owing to its advantages over the traditional chemical route, including lower cost-effectiveness, the lack of need for precise temperature or pressure control in large-scale production processes, and the effective production of fine, uniformly dispersed particles.

Figure 1 shows the Ge@GeO

2-C composite material production scheme using the simple HEBM technique. Owing to the high malleability of alloy metals (Ge, Pb, Sn, Si, etc.), size control cannot be achieved by directly milling the material. To obtain mechanically well-pulverized particles, bulk GeO

2 particles were reduced to metallic Ge by carbon-thermal reduction of GeO2 with Super P (2GeO

2 + 2C → 2Ge + 2CO

2) during HEBM. This produces Ge@GeO

2-C core-shell particles that are evenly implanted in a carbon matrix in the form of a composite.

Figure 2a displays the Ge@GeO

2-C’s XRD patterns with respect to the milling time (1, 3, and 5 h). The XRD pattern of the commercial GeO

2 used as starting material exhibited a sharp GeO

2 (101) peak. The prepared Ge@GeO

2-C patterns clearly displayed a prominent peak corresponding to the metallic Ge (111) peak as the synthesis time increased. As can be seen by comparing the (111) peaks, the peak broadening increases as ball milling progresses, which indicates that the particle size decreases. The Scherrer equation calculated the Ge@GeO

2-C (5 h) crystalline size to be approximately 4.2 nm. The wide background at approximately 25–35° was attributed to Super P. Subsequently, XPS was performed to confirm the origin of GeO

2 (

Figure 2b). A prominent peak was observed in the pre-sputter data at 33 eV, which corresponds to the binding energy of Ge-O. The metallic Ge signal at 30 eV had a minimal peak strength, indicating that GeO

2 was the primary surface chemical component of the Ge@GeO

2-C particles. In contrast to that of pre-sputtering, the XPS spectra obtained after surface sputtering exhibited a larger metallic Ge signal (30 eV) because the underlying metallic Ge core was visible owing to the etching of the GeO

2 layer.

The shapes and morphologies of the prepared Ge@GeO

2-C were confirmed by field-emission SEM (Figures 3a–c). The average diameter of the Ge@GeO

2-C particles was assumed to be submicron, providing a core-shell structure and a mostly spherical shape. HRTEM was performed to further elucidate the cluster morphology. Figures 3d and e show spherical Ge@GeO

2-C nanoparticles that are approximately 10 nm in size. EDS maps showed a uniform elemental distribution of Ge, O, and C throughout Ge@GeO

2-C. In particular, in

Figure 3d, the low- and high-magnification TEM images clearly show that crystalline nanoparticles a few nanometers in size are uniformly embedded in the carbon matrix. Based on the abovementioned results, we confirmed that Ge@GeO

2-C particles can be successfully obtained with a facile synthesis compared to previous methods using HEBM.

3.2. Electrochemical performance & fundamental consideration of Ge@GeO2-C

The electrochemical properties of Ge@GeO

2-C were compared with respect to the samples (1, 3, and 5 h) by voltage profiles and differential capacity (dQ/dV), which were cycled in a lithium half-cell at a current rate of 1/60 between 0.005 and 1.5 V vs Li/Li+. In the initial cycle, the specific capacities for discharging (i.e., lithiation) and charging were 1782/528 mAh g

-1 (1 h), 1795/780 mAh g

-1 (3 h), and 1765/838 mAh g

-1 (5 h) (1C = 1800 mAh g

-1, Figures 4a and b). As expected, the first discharge showed high capacities, and the initial Coulombic efficiencies were 30%, 43%, and 47%m, respectively. The various voltage plateaus and dQ/dV peaks are generally linked to two electrochemical processes: (1) the displacement-conversion reaction from GeO

2 to Ge in the upper voltage region (>1.0 V) and (2) the alloying reaction of Ge with Li in the lower voltage region (1.0 V). During the initial discharging process, the occurrence of voltage plateaus (corresponding dQ/dV peaks) at 1.2 V can be attributed to the conversion reaction of GeO

2. (1) Conversion of GeO

2 to the metallic Ge phase. The two peaks below 1.0 V (0.2 and 0.54 V) are attributed to the alloying reaction of Ge with Li in the lower-voltage region. During the reverse step, the peaks at 0.4 V are attributed to the de-alloying and oxidation of Ge. Based on the aforementioned results, the capacity difference among the three samples (1, 3, and 5 h) is attributed to the higher amount of metallic Ge (5 h > 3 h > 1 h).

Figures 4c and d show the charge-discharge performance for the first cycles and dQ/dV plots cycled at a current rate of 1/30 between 0.005 and 1.5 V vs Li/Li+. The specific capacities for discharging/charging are 1729/525 mAh g-1 (1 h), 1741/803 mAh g-1 (3 h), and 1752/811 mAh g-1 (5 h). The initial Coulombic efficiencies are 30%, 46%, and 46.2%, respectively. The overall trend was found to be consistent with the aforementioned description, showing no significant deviation.

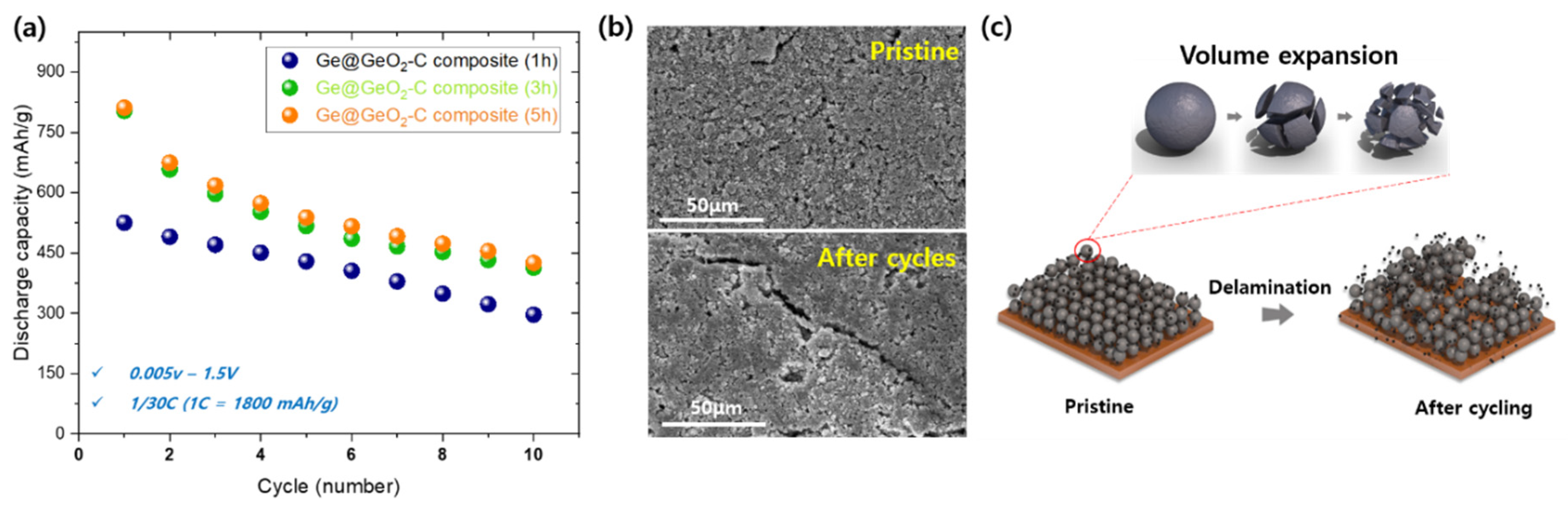

Figure 5a illustrates the cyclic characteristics of Ge@GeO

2-C cells (1, 3, and 5 h) at a current rate of 1/30 between 0.005 and 1.5 V for 10 cycles, which show an increased discharge capacity with increased milling time, as described above. However, the cyclic performance requires improvement. To understand the capacity fading, the corresponding post-mortem SEM images were characterized (

Figure 5b) after 30 cycles. The surface SEM images show increased cracks on the surface and size at the same scale, which may have decreased the performance of the cell by isolating active particles from the Cu foil compared to the pristine sample.

Based on these results, poor cycling properties were considered: (1) huge volume change of Ge upon lithiation/de-lithiation, resulting in pulverization; and (2) delamination during the cycles leading to electrical isolation as well as SEI layer decomposition, as shown in

Figure 5c. These results indicate that further research is required to improve the performance by considering the parameters (milling time, ratio of components, synthesis temperature, etc.). Similar to the previous study on Pb, carbon was expected to act as a sufficient buffer layer during volume expansion; however, the Ge particles appear to have broken down rapidly during cycling. Further research is required to form a good SEI layer, including studies on electrolyte additives, carbon and Ge mixing composition ratios, and other water-based binders. Nevertheless, we hope that the HEBM synthesis method, which is simple and easy to mass-produce compared to previous studies, will contribute to the development of next-generation Ge anode materials.

4. Conclusions

GeO2/Carbon (Ge@GeO2-C composite) was synthesized using a simple HEBM process to address the limitations of current anodes. The GeO2-shell-on-Ge-metal core composite was characterized using XPS, XRD, SEM, and TEM analyses. As the ball milling time increased, the proportion of metallic Ge increased because of the reduction reaction, and the discharge capacity also increased. The Ge@GeO2-C composite was evaluated for its electrochemical properties via differential capacity analysis (dQ/dV) and the galvanostatic charge-discharge technique to determine its suitability as an anode material for LIBs. The initial discharge capacity reached approximately 1800 mAh g-1 at a rate of C/30 (Ge@GeO2-C composite, 5 h); however, it exhibits poor cycling retention over 10 cycles. The carbon matrix was expected to alleviate the volume expansion of Ge (370%); however, the postmortem SEM images showed that the composite cracked and delaminated from the Cu foil after only 30 cycles. Although improvements are required, we hope that these findings will contribute to the future development of advanced LIBs.

Author Contributions

Jinhyup Han and Hyun Woo Kim contributed equally to this paper.

Conceptualization, J. Han; methodology, J. Han and H. W. Kim; formal analysis, J. Han and H. W. Kim; investigation, J. Han and H. W. Kim; writing—original draft preparation, J. Han and H. W. Kim; Data curation, J. Han and H. W. Kim; writing—review and editing, J. Han and H. W. Kim; supervision, J.Han; project administration and funding acquisition, J. Han and H. W. Kim. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by the Bisa Research Grant of Keimyung University in 2023 (Project No: 20230674) and a Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes (COMPA) grant funded by the Korean Government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (grant number RS-2023-00304768).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, T.; Song, W.; Son, D.-Y.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Lithium-ion batteries: outlook on present, future, and hybridized technologies. Journal of materials chemistry A 2019, 7, 2942–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Amine, K. 30 years of lithium-ion batteries. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1800561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthiram, A. An outlook on lithium ion battery technology. ACS central science 2017, 3, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Sun, Y.-K. Nano/microstructured silicon–graphite composite anode for high-energy-density Li-ion battery. ACS nano 2019, 13, 2624–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, X.; Zhu, J.; Müller-Buschbaum, P.; Cheng, Y.-J. Silicon based lithium-ion battery anodes: A chronicle perspective review. Nano Energy 2017, 31, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrovac, M.; Christensen, L.; Le, D.B.; Dahn, J.R. Alloy design for lithium-ion battery anodes. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2007, 154, A849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Zhang, X.F.; Cui, Y. High capacity Li ion battery anodes using Ge nanowires. Nano letters 2008, 8, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.-Y.; Chang, B.; Wang, K.-X. Recent progress on germanium-based anodes for lithium ion batteries: Efficient lithiation strategies and mechanisms. Energy Storage Materials 2020, 30, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nature reviews materials 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; Kashkooli, A.G.; Xiao, X.; Cai, M.; Chen, Z. Silicon-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries: from fundamentals to practical applications. Small 2018, 14, 1702737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Park, J.; Bak, S.M.; Son, S.B.; Gim, J.; Villa, C.; Hu, X.; Dravid, V.P.; Su, C.C.; Kim, Y. New High-Performance Pb-Based Nanocomposite Anode Enabled by Wide-Range Pb Redox and Zintl Phase Transition. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31, 2005362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Han, J.; Gim, J.; Garcia, J.; Iddir, H.; Ahmed, S.; Xu, G.-L.; Amine, K.; Johnson, C.; Jung, Y. Evidence of Zintl Intermediate Phase and Its Impacts on Li and Na Storage Performance of Pb-Based Alloying Anodes. Chemistry of Materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A. Electrochemical alloying of lithium in organic electrolytes. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 1971, 118, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipparoni, F.; Bonino, F.; Panero, S.; Scrosati, B. Electrochemical properties of metal oxides as anode materials for lithium ion batteries. Ionics 2002, 8, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, M.; Morales, J.; Sanchez, L. Lead-based systems as suitable anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Electrochimica acta 2003, 48, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraldo Bicelli, L.; Rivolta, B.; Bonino, F.; Maffi, S.; Malitesta, C. Lead oxides as cathode materials for voltage-compatible lithium cells. J. Power Sources;(Switzerland) 1986, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza, L.C.; Monconduit, L.; Seznec, V. Si and Ge-based anode materials for Li-, Na-, and K-ion batteries: a perspective from structure to electrochemical mechanism. Small 2020, 16, 1905260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seng, K.H.; Park, M.H.; Guo, Z.P.; Liu, H.K.; Cho, J. Self-assembled germanium/carbon nanostructures as high-power anode material for the lithium-ion battery. Angewandte Chemie 2012, 124, 5755–5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Park, C.-M.; Sohn, H.-J. Electrochemical characterizations of germanium and carbon-coated germanium composite anode for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters 2008, 11, A42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chockla, A.M.; Klavetter, K.C.; Mullins, C.B.; Korgel, B.A. Solution-grown germanium nanowire anodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2012, 4, 4658–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).