1. Introduction

Contract farming, which is an effective method to improve production efficiency and realize supply chain coordination, has been widely applied in agricultural production among developing countries. There are many benefits for farmers in contract farming, including access to new markets, technical assistance, employment opportunities, stable income, and poverty alleviation[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. At the same time, contract farming can reduce fluctuations in crop prices and help farmers shoulder production and market risks[

6,

7]. In northern China, there are arid and semi-arid areas where temperatures are low, with large temperature differences and less precipitation. In these areas, drought-resistant crops, such as cereal grains, millet, and corn, are mainly cultivated. These crops have relatively low yields, and most farmers face such problems as small production scale, low product-added value, and weak risk resilience. Therefore, developing agricultural industry chains through contract farming has a more significant impact on rural areas in China and other developing and less-developed countries. Generally, farming contracts can be divided into sales contracts and resource-providing contracts providing credits, inputs, and technical services. In China, early farming contracts are primarily simple sales contracts. However, with the continuous innovation and evolution of cooperation modes, on the basis of sales contracts of agricultural products, agricultural enterprises and cooperatives and intermediary organizations may sign a series of contracts relating to technical guidance, social services, and financial support with farmers, forming a complete and effective contractual system. The efforts were to construct a long-term and stable community of shared interests and enhance the overall efficiency of industrial chains, thus enabling farmers, businesses, and other members of supply chains to share value chain benefits[

8,

9]. Different types of contracts have different influences[

10,

11,

12,

13]. Existing studies mostly analyzed the influences of sales contracts and resource-providing contracts separately or comparatively. However, contract farming with different product varieties and in different regions has different characteristics and models. Therefore, these studies provide no universal results. Based on this, and with the notions of strong tie and weak tie in the social network theory, this study has constructed an indicator of tie strength of farmers with agricultural enterprises and cooperatives and intermediary organizations to measure the connection degree of contract farming comprehensively, thus overcoming the deficiencies in simply differentiating sales contracts and production contracts.

Formal contracts can be used to specify the rights, responsibilities, and penalty mechanisms of parties involved, thus helping reduce breach rates and opportunistic behaviors[

14]. However, because contract members such as businesses and farmers are independent and rational operation individuals, their objectives to maximize their own interests could lead to decision-making behaviors that conflict with the objectives of supply chain systems. Therefore, it is necessary to coordinate objective conflicts and enhance cooperation stability through embedded relationships[

15]. In recent years, game theory analysis has been widely used in studying relationship stability in contract farming[

16,

17,

18].

However, in the long run, stable and safe relationships among contract members are a prerequisite for the sustainable development of contract farming supply chains. Compared with businesses, farmers present poor sustainability in participating in contract farming. Therefore, this study utilized the contract renewal willingness of farmers to measure their sustainability in participating in contract farming. There is a common consensus that relationship governance is conducive to establishing a long-term, stable cooperative relationship[

19,

20,

21]. However, current research has mostly investigated the cooperative stability among businesses, farmers, and intermediary organizations in the supply chain from the perspective of some single-dimensional connection relationships, such as trust relationships and reciprocity relationships. Less research has explored the mutual relationships among various dimensions and their joint working mechanisms on the contract renewal willingness of farmers. In view of this, this study has utilized the field survey data of farmers in the plant industry in Inner Mongolia, China, and employed the structural equation model to empirically analyze the influences of three constitutional dimensions of tie strength, namely, reciprocity intensity, interaction intensity, and trust level, on the contract renewal willingness of farmers, thus revealing their working mechanisms and providing targeted policy recommendations.

The possible academic contributions of this study primarily include the following two aspects: First, with reference to the social network theory and based on the real situations of farmers participating in supply chain contracts, this study constructed indicator dimensions of tie strength, including trust level, interaction intensity (frequency of communication ) and reciprocity intensity. This measurement system is of important significance in measuring connection degrees. Second, based on empirical analysis, this study has deduced the theoretical logic of tie strength promoting continuous cooperation of farmers. Through exploring the motivation mechanism of farmers continuously involved in agricultural industry chains, this study aims to provide theoretical evidence and practical reference for ensuring the stable operation of overall agricultural product supply chains and long-term equitable sharing of incremental benefits of whole industrial chains among small farmers.

2. Theoretical Analysis

Tie strength, first introduced in Granovetter’s article, The Strength of Weak Ties, is a combination of four elements, namely, reciprocity intensity, interaction duration, closeness, and emotional depth, reflecting the communication frequencies and mutual intimacy among individuals in a social network. There are strong ties among social network members who communicate frequently and have close relationships with each other. Otherwise, there are weak ties [

22]. Primarily, an indicator of relationship closeness is applied to measure tie strength [

23,

24]. For individuals who have infrequent communications or tend to conduct one-way communications, there are weak ties. On the contrary, there are strong ties among individuals with high-frequency communications and interactions, intensive emotions, and high mutual reciprocity. Based on those four dimensions proposed by Granovetter, scholars have attempted to expand the concept of tie strength from different perspectives, with rich research outcomes achieved in the domains of sociology and management [

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, current studies have mostly been based on the perspective of enterprises in the construction of tie strength, and fewer studies have investigated the connection strength of supply chains of contract farming from the perspective of farmers. Based on the social network theory, this study has proposed the notion that the tie strength of contract farming supply chain refers to the relationship depths developed through communications and interactions between farmers and agricultural enterprises (farmer cooperatives) that have signed formal contracts with farmers for the purpose of fulfilling long-term contracts.

With reference to relevant studies, this study has measured the tie strength of farmers participating in supply chains of contract farming through three dimensions, including trust level, interaction intensity, and reciprocity intensity[

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. These three dimensions influence one another to a certain extent. Among them, interaction and reciprocity intensities are the conclusive assessment of communications and interactions and mutual benefits achieved during the completed cooperation processes. Understanding and perception of interactions and reciprocity constitute the foundation of trust, further exerting an important influence on trust level. Continuous cooperation primarily relies on trust, while communications among cooperative partners have a significantly positive effect on their mutual trust [

35,

36]. On the basis of instrumental motivation, reciprocity is the key to the generation of cooperative behaviors. Farmers experiencing reciprocity and satisfaction exhibit improved trust levels [

37,

38]. On the other hand, frequent communications and interactions between both parties can promote identification among cooperative partners through the sharing of information and technology, and reciprocity-based transaction trust of farmers can be elevated to their affective or cognitive trust in agricultural enterprises. Furthermore, through interactions and communications, information asymmetry can be reduced, and unnecessary misunderstandings can be avoided, thus enhancing trust levels between both parties. Based on the above analysis, it can be inferred that more intensive interactions of farmers with enterprises and cooperatives will lead to higher trust levels of farmers in their cooperative partners and that higher reciprocity levels of farmers with enterprises and cooperatives will result in higher trust levels of farmers in their cooperative partners. Therefore, in this paper, Hypotheses 1a and 1b were proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1a(H1a). Interaction intensity has a positive influence on trust level.

Hypothesis 1b(H1b). Reciprocity intensity has a positive influence on trust level.

For cooperative economic behaviors to occur and persist, trust is a necessary condition[

39]. Under the uncertainty of cooperative behaviors, trust is an important mechanism to inhibit moral hazards and opportunistic behaviors of reversal selection caused by information asymmetry. A higher level of trust leads to a naturally enhanced possibility of continuous cooperation among organization members[

40]. On the one hand, current reciprocity behaviors have raised the trust levels of farmers in agricultural enterprises and cooperatives. Farmers anticipate that their cooperative partners will not harm their interests with short-term opportunistic actions in the future, thus presenting a higher willingness to renew their contracts. On the other hand, current interaction behaviors have also raised the trust levels of farmers in their cooperative partners. Farmers anticipate that smooth cooperation will be realized in the future through further information and technology exchanges and recognize that their partners are reputable and responsible enterprises, thus further strengthening their willingness to renew their contracts. Based on the above analysis, it can be summarized that farmers with high trust levels in their cooperative partners will accept their future cooperation more and present a stronger willingness to renew their contracts. Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 2 as follows:

Hypothesis 2(H2). Trust level has a positive impact on farmers' willingness to renew their contracts.

Differing from their initial decisions to participate in contract farming, the contract renewal willingness of farmers reflects the willingness degrees of farmers to renew their contracts based on their current cooperative relationships. From the theory of value perception, it can be known that the tie strength of current cooperation has an important influence on farmers’ contract renewal willingness through perceived core economic value. Social trust has a positive impact on benefit perception. With trust in their partners and through horizontal and vertical comparisons of their cooperative benefits, farmers will develop the idea that continuous cooperation with their partners will also bring about high economic benefits for them in the future. Therefore, it can be concluded that higher trust levels of farmers in their cooperative partners will lead to their higher perception levels of economic value. Based on this conclusion, this paper proposes Hypothesis 3 as follows:

Hypothesis 3(H3). Trust level has a positive impact on economic value perception.

Through research, many scholars have found that perceived economic value has a significantly positive impact on the willingness of future cooperation [

41,

42]. The key element influencing farmers deciding to participate in contract farming for the first time and renewing their contracts is their measurement of perceived economic value. That is, their operation decisions must comply with their judgment criteria of perceived economic value. The primary factors influencing their initial participation decisions include the reputations of cooperative enterprises and the anticipation that short-term economic benefits are higher than economic costs (including production costs and opportunity costs). Meanwhile, the influencing factors on contract renewal willingness include the acceptable level of risks and the recognition that economic benefits obtained through sustained long-term cooperative relationships are higher than economic costs. In summary, perceived economic value is conducive to maintaining the cooperative relationships among all cooperative entities in the supply chain. Therefore, this paper proposes Hypothesis 4 as follows:

Hypothesis 4(H4). Perceived economic value has a positive influence on contract renewal willingness.

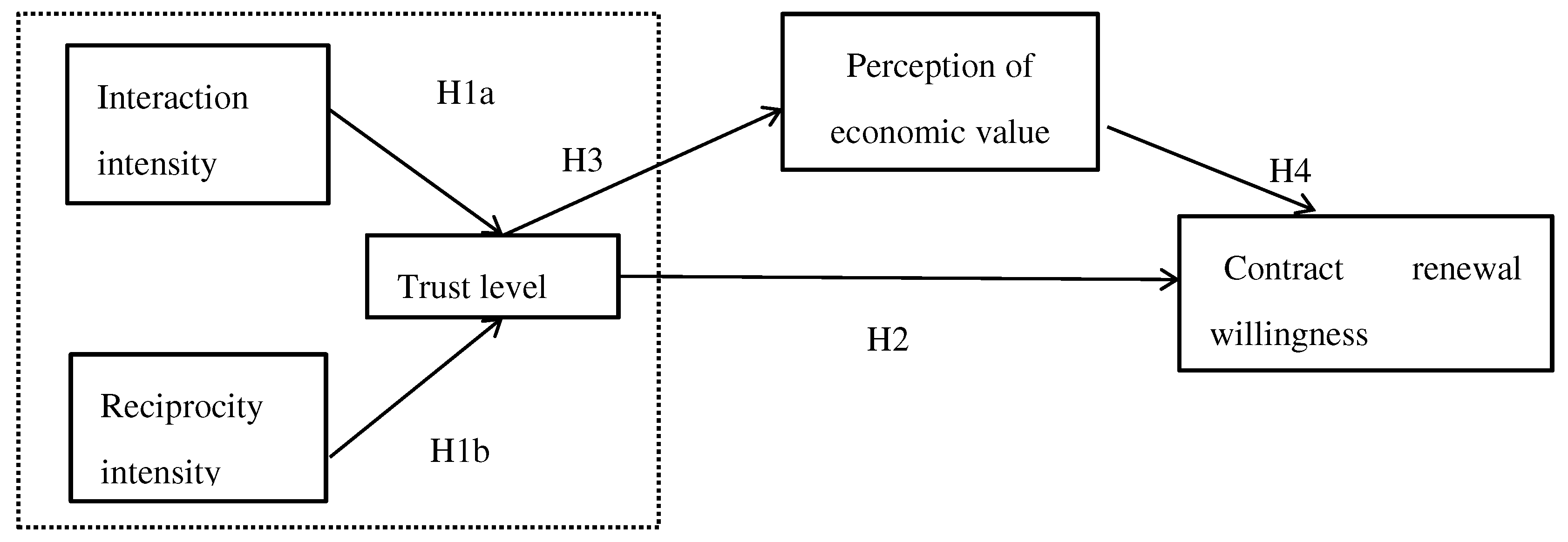

Based on the above analysis, a theoretical analysis framework of tie-strength dimensions, economic value perception, and contract renewal willingness has been obtained in this study. The specific results are shown in

Figure 1.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

Field survey data from thirty-one administrative villages in seven counties of Inner Mongolia, China, were used in this study. Some farmers who have signed official contracts with agricultural enterprises or cooperatives were selected as the subjects of this study. With a combination of residence villages of cooperative farmers randomly selected and farmers intentionally selected, a total of 286 questionnaires were collected through a survey method of face-to-face interviews. With seven invalid questionnaires and three non-compliant questionnaires excluded, a total of 276 valid questionnaires were finally obtained, with a valid questionnaire collection rate of 96.50%. The contract crops of surveyed farmers primarily include millet, miscellaneous grains, beans (mainly buckwheat, sorghum, soybean, and mung bean), oats, potatoes, sweet corn, and sugar beet. Contract crops planted in the survey areas are primarily local specialty crops.

Detailed basic characteristics of survey samples are listed in

Table 1. Ages of sample farmer household heads present a distribution pattern as follows: 151 people, who account for 54.71% of the total sample size, are 60 years old or above, 111 people have an age within the range of 45-59 years, accounting for 40.22% of the total sample size, and 14 people are younger than 45 years, accounting for 5.07% of the total sample size. Among all survey samples, there are primarily elderly farmers aged 60 years or above engaging in the agricultural plant industry, followed by middle-aged farmers aged 45-59 years, and young farmers account for only 5% of the total sample size. Household heads with an education level of elementary school or junior high school hold the highest proportion among all survey samples, accounting for over 85% of the total sample size. Total household demographic data show that farmer households surveyed are primarily “empty-nest households of elderly people” whose children are mostly migrant workers or settle in cities after graduating from universities instead of engaging in local agricultural production. Over 65% of all survey samples have a planting area between 11 mu and 99 mu, and the proportion of large-scale planting households with a planting area exceeding 100 mu has also reached 25%. Followed by agricultural households with an annual income of 90,000 yuan and above, agricultural households with an annual income of 30,000-89,900 yuan hold the most proportion among all those households surveyed. Agricultural households with an annual income of 30,000 yuan and below only account for 10% of all those agricultural households surveyed. The primary reason lies in that low-income agricultural households mostly belong to labor groups devoid of labor abilities or labor groups with low labor competence. Basically, these households do not engage in agricultural planting operations anymore. Therefore, this study has excluded these households from its investigation scope.

3.2. Research method

This study has primarily explored logical relationships among three dimensions of tie strength, perceived economic value, and contract renewal willingness of farmers. It is difficult to measure such variables as interaction intensity, reciprocity intensity, trust level, and farmer contract renewal willingness directly. Compared with other research methods, the method of structural equation modeling can handle complex relationships among all latent variables and obtain their key driving pathways, thus improving the accuracy of predicted results. Therefore, the method of structural equation modeling was primarily applied in this study for analysis, with the following measurement equations:

Equation (1) is a measurement equation with an exogenous variable. In this equation, ξ represents the exogenous latent variable, and Λx is a factor loading matrix reflecting the relationship between the exogenous indicator X and the exogenous latent variable. Equation (2) is an equation with an endogenous variable. In this equation, η represents the endogenous latent variable, and Λy is a factor-loading matrix reflecting the relationship between the endogenous indicator Y and the endogenous latent variable. Also, δ and ε are two measurement error items. In this study, interaction intensity and reciprocity intensity are two exogenous latent variables, while trust level, perceived economic value, and farmer contract renewal willingness are endogenous latent variables. A structural equation can be used to reflect the relationships between exogenous latent variables and endogenous latent variables. The specific structural equation used in this study is as follows:

In equation (3), B reflects the mutual influencing relationships among endogenous latent variables η (trust level, perceived economic value, and farmer contract renewal willingness), and Φ reflects the mutual influencing relationships between the exogenous latent variable ξ (interaction intensity and reciprocity intensity) and the endogenous latent variable η. λ is a random error item of the structural equation, reflecting the unexplained part of the endogenous latent variable η.

3.3. Variable Measurement and Testing

3.3.1. Variable Measurement

In this study, except for the item of net income of contract crop (PEV1), a Likert 5-point scale was applied to each measurement item used in the questionnaire survey. Scores 1-5 are used to represent the assessment degrees of surveyed farmers on the content involved in each questionnaire item. Among them, score 1 represents “completely not concerned," “completely not," and “completely unsatisfied," score 2 represents “not intimate," “not frequent," and “not satisfied," score 3 represents “common," score 4 represents “intimate," “frequent” and “satisfied”, and score 5 represents “very intimate," “very frequent” and “very satisfied."

1. Tie strength: This study divided tie strength into three dimensions, which are trust level, interaction intensity, and reciprocity intensity. Among them, trust level refers to how farmers believe that their cooperative partners are willing and able to fulfill their corresponding obligations[

43,

44]. With reference to the relevant research outcomes and with the combination of reliability analysis based on the trust level scale, this study has selected three items to measure trust level. Interaction intensity reflects how frequently farmers communicate with their cooperative partners and is normally measured with communication degrees and times through different communication approaches (telephone, written communication, face-to-face communication, etc.). With the consideration of farmers’ characteristics, this study has selected four items to measure interaction intensity[

45]. Reciprocity intensity refers to the levels of interest-based cooperation and reciprocal relationships between farmers and their cooperative partners through resource exchanges. With reference to mature scales and with the combination of farmers’ characteristics, this study has selected four items to measure reciprocity intensity[

46].

2. Perceived economic value: With the combination of reliability analysis using scale, this study has selected two items to measure perceived economic value. Among them, PEV1 is the natural logarithm of the net income of the contract crop. The net income of the contract crop can be calculated by reducing input costs from the yield of the contract crop multiplied by the selling price. Specifically, input costs include direct material costs such as seed costs, fertilizer costs, pesticide costs, plastic film costs, and irrigation costs, direct labor costs such as self-harvesting labor costs or hired harvesting labor costs, and machinery costs such as hired machine costs for land plowing, sowing, and harvesting or depreciation costs of self-owned machines and fuel costs.

3. Farmer contract renewal willingness: With reference to relevant research, and based on actual survey results, this study has selected three items to measure the willingness of farmers to renew their contracts[

47]. Specific measurement results and descriptive statistics of all variables mentioned above are listed in

Table 2.

3.3.2. Reliability and Validity

In this study, a factor analysis using SPSS20.0 and Amos26.0 software was performed to test the Reliability and validity of relevant variables, with the specific results listed in

Table 4. In order to examine the Reliability of questionnaire data and the internal consistency of all questionnaire items, this study has calculated the Cronbach’s α values of trust level, interaction intensity, reciprocity intensity, perceived economic value, and farmer contract renewal willingness, which are 0.849, 0.781, 0.905, 0.626, and 0.789, respectively. All these values are higher than 0.6, and their C.R. values are higher than 0.7, indicating good validity of scale.

In terms of validity, the scales used in this study were designed and developed based on the combing of a lot of literature and the reference to relevant study outcomes and mature scales, with a combination with actual survey situations. Results listed in

Table 3 show that except for perceived economic value, the KMO values of all other latent variables fall into a range of 0.609-0.839, which are higher than 0.6. Also, the significance probability P of the Bartlett’s sphere test has reached a significance level, with an overall KMO value of 0.883. This indicates that all these variables are suitable for factor analysis. With all their AVE values greater than 0.5, it indicates that all questionnaire items can precisely reflect the contents to be validated, and the model designed based on previous research exhibits high convergent validity. In this study, an un-rotated principal component analysis was conducted on those sixteen items involved through a Harman single-factor test, with the results indicating a 40.22% variance explanation of the greatest factor, which is below 50%. Therefore, it can be inferred that there is no severe common-method bias problem in this study.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity tests.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity tests.

| Latent variable |

Item |

Factor Loading |

Cronbach's α |

C.R. |

KMO |

AVE |

Trust level

(TR) |

TR1 |

0.834 |

0.849 |

0.853 |

0.718 |

0.660 |

| TR2 |

0.845 |

| TR3 |

0.754 |

Interaction intensity

(IN) |

IN1 |

0.642 |

0.781 |

0.798 |

0.749 |

0.500 |

| IN2 |

0.736 |

| \ |

IN3 |

0.776 |

| IN4 |

0.663 |

Reciprocity intensity

(RE) |

RE1 |

0.796 |

0.905 |

0.907 |

0.836 |

0.709 |

| RE2 |

0.877 |

| RE3 |

0.898 |

| RE4 |

0.791 |

| Perceived economic value(PEV) |

PEV1 |

0.801 |

0.626 |

0.714 |

0.500 |

0.584 |

| PEV2 |

0.571 |

| contract renewal willingness(CRW) |

CRW1 |

0.931 |

0.789 |

0.816 |

0.609 |

0.614 |

| CRW2 |

0.461 |

| CRW3 |

0.871 |

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Correlation Test of Variables

Before the analysis of structural equation modeling, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted in this study on trust level, interaction intensity, reciprocity intensity, perceived economic value, and farmer contract renewal willingness. The specific results are listed in

Table 4. From

Table 4, it can be seen that there are significant correlations among all variables, thus preliminarily validating the research hypotheses. In addition, the correlation coefficient of each variable with other variables is lower than the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) value, indicating good discriminant validity of variables.

Table 4.

The square root of AVE and pearson correlation coefficient.

Table 4.

The square root of AVE and pearson correlation coefficient.

| Construct |

TR |

IN |

RE |

CRW |

PEV |

| TR |

0.8121

|

|

|

|

|

| IN |

0.463 |

0.707 |

|

|

|

| RE |

0.662 |

0.440 |

0.842 |

|

|

| CRW |

0.477 |

0.392 |

0.594 |

0.783 |

|

| PEV |

0.296 |

0.221 |

0.352 |

0.481 |

0.764 |

4.2. Model fit analysis

In this study, Amos26.0 was used to fit the structural equation model, with the overall fit results listed in

Table 5. The fit indexes listed in

Table 5 indicate that the chi-square degree of freedom χ2/df obtains a value of 2.565, which is below 3. Fit indexes like GFI are greater than or close to 0.90, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is less than 0.08, indicating a good fit of the model constructed, which meets the fit criteria and can be used to perform the hypothesis testing.

4.3. Results

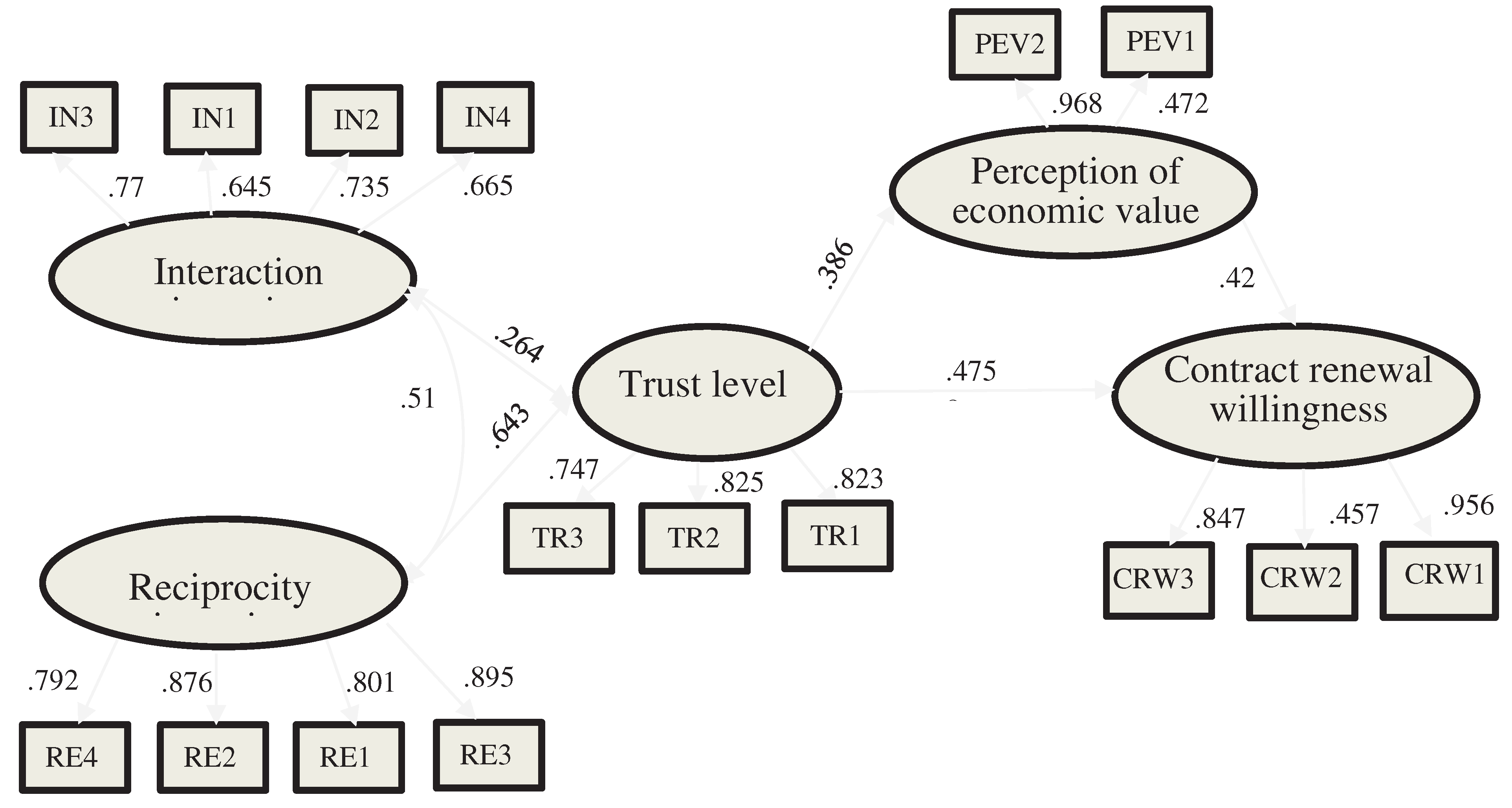

The method of maximum likelihood estimation was used to verify those hypotheses proposed in this research, with analysis diagrams and test results of the standardized influencing pathways of model fit obtained, which are shown in

Table 6. From those parameter estimation values and test results listed in

Table 6, it can be seen that the pathway coefficient of interaction intensity to trust level has a value of 0.264 and is significant at the 1% level, thus confirming Hypothesis 1a. That is, interaction intensity has a significantly positive influence on trust level. Also, the pathway coefficient of reciprocity intensity to trust level obtains a value of 0.643 and is significant at the 1% level, thus confirming Hypothesis 1b. That is, reciprocity intensity has a significantly positive influence on trust level. Therefore, it can be seen that both interaction intensity and reciprocity intensity have a significantly positive influence on trust level. Furthermore, a higher influence level of reciprocity intensity indicates more frequent interactions between agricultural enterprises and farmers with higher intensities of reciprocity and stronger trust relationships. Meanwhile, the direct pathway coefficient of trust level to farmer contract renewal willingness has a value of 0.475 and is significant at the 1% level, thus confirming Hypothesis 2. That is, trust level has a significantly positive influence on farmer contract renewal willingness. Farmers with stronger trust in their cooperative partners have a stronger intention to participate in contract farming continuously. The pathway coefficient of trust level to perceived economic value obtains a value of 0.386 and is significant at the 1% level, thus confirming Hypothesis 3. That is, trust level has a significantly positive impact on perceived economic value. The pathway coefficient of perceived economic value to farmer contract renewal willingness has a value of 0.420 and is significant at the 1% level, thus confirming Hypothesis 4. That is, perceived economic value has a significantly positive impact on farmers' contract renewal willingness. Perceived economic value plays a partial mediating role in the influence of trust level on farmer contract renewal willingness.

The estimation results of the measurement model can reflect the relationship between observation variables and latent variables. From the relevant test results of pathway coefficients listed in

Figure 2, it can be known that:

Measurement variables of IN1, IN2, IN3, and IN4 corresponding to the variable of interaction intensity all passed the significance test at the 1% level, with standardized coefficients of 0.645, 0.735, 0.773, and 0.665, respectively. This indicates that face-to-face communication, telephone contact, and WeChat communication are all conducive to increasing interaction and communication frequencies among supply chain partners, and traditional face-to-face communication and telephone communication are still the most common and effective methods of communication among farmers.

Measurement variables RE1, RE2, RE3, and RE4 corresponding to the variable of reciprocity intensity all passed the significance test at the 1% level, with standardized coefficients of 0.801, 0.876, 0.895, and 0.792, respectively. This indicates that the satisfaction levels of farmers in cooperation with their cooperative partners and their recognition levels of win-win relationships with their partners can significantly increase the reciprocity intensities among supply chain partners.

Figure 2.

Analysis diagram of influencing pathways of farmer contract renewal willingness.

Figure 2.

Analysis diagram of influencing pathways of farmer contract renewal willingness.

Measurement variables TR1, TR2, and TR3 corresponding to the variable of trust level all passed the significance test at the 1% level, with standardized coefficients of 0.823, 0.825, and 0.747, respectively. This indicates that the recognition of farmers on their cooperative partners’ compliance with agreements, contract-fulfilling capabilities, candidness, and trustworthiness can significantly enhance their trust levels in their partners.

Measurement variables PEV1 and PEV2 corresponding to the variable of perceived economic value all passed the significance test at the 1% level, with standardized coefficients of 0.472 and 0.968, respectively. This indicates that compared with the incomes of non-contract farmers, the net incomes of contract farmers during their cooperation periods have a significant impact on the economic value they perceive from future contract cooperation.

Measurement variables CRW1, CRW2, and CRW3 corresponding to the variable of farmer contract renewal willingness all passed the significance test at the 1% level, with standardized coefficients of 0.956, 0.457, and 0.847, respectively. This indicates that the willingness intensities of farmers to participate in contract farming continuously and overcome difficulties of contract farming participation, as well as the difficulty levels for them to participate in further contract farming, are three factors with progressively weakening influences on the contract renewal willingness of farmers.

4.4. Mediating Effect Analysis

Based on the hypotheses proposed in the theoretical analysis section and the above result analysis, it can be inferred that trust level can affect farmer contract renewal willingness through perceived economic value. A Bootstrap method in Amos was used in this paper to test the mediating effect of perceived economic value and its corresponding confidence interval, with the specific results listed in

Table 7. Among them, LLCI and ULCI represent the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval, respectively. The judging criteria for direct and indirect effects are as follows: If the confidence interval of the indirect effect does not include zero, there is a mediating effect among latent variables. If the confidence interval of the direct effect includes zero, those mediating variables play a complete mediating role, while if the confidence interval does not include zero, those mediating variables play a partial mediating role. The mediating effect in the “trust level → perceived economic value → contract renewal willingness” pathway obtains a value of 0.162 (0.386 * 0.420), with a confidence interval of 0.141-0.293 not including zero, indicating that perceived economic value plays a mediating role in the influence of trust level on contract renewal willingness. Meanwhile, the direct effect of the “trust level → contract renewal willingness” pathway has a confidence interval of 0.338 - 0.593, not including zero, indicating that mediating variables play a partial mediating role between trust level and contract renewal willingness. Therefore, the total effect of trust level on farmer contract renewal willingness obtains a value of 0.637 (direct effect value of 0.475 + mediating effect value of 0.162), with the direct effect accounting for 74.57% of the total effect and the mediating effect of perceived economic value accounting for 25.43% of the total effect. Reciprocity and interaction intensities have an indirect impact on contract renewal willingness through trust level. The indirect influencing effect of reciprocity intensity on contract renewal willingness obtains a value of 0.168 (0.264 * 0.637), with the indirect influencing effect of interaction intensity on contract renewal willingness obtaining a value of 0.410 (0.643 * 0.637).

5. Discussion

Contract farming is an important method of vertical collaboration in the value chain of agriculture and has been widely developed in the world because of its advantages in optimizing production organizations, promoting technological progress, and achieving intensive production. Contract farming is of great significance in organically bridging small farmers with agricultural modernization and promoting sustainable development of small-farmer and rural economies. It is of theoretical and practical significance for the government to formulate policies to promote the quality development of contract farming and form a pattern of complementary advantages and labor division between enterprises and farmers in the industrial chain.

Based on existing literature, this study has constructed core variables (interaction, reciprocity, and trust) of tie (relationship) strength in supply chain networks. The study has found that the Chinese government mainly measures the linking-farming effect of agricultural enterprises through the numbers of contracted farmers, which are used as evidence for obtaining political support. This determination criterion, which only focuses on quantity with no measurement of quality, causes many agricultural enterprises to emphasize formal connections without true input of significant human, material, and financial resources to establish stable and effective interest-linking mechanisms with farmers. Therefore, farmers do not have a strong identification of leading agricultural enterprises and farmer-specialized cooperatives. The research conclusions drawn in this paper have provided political evidence for the government to guide agricultural enterprises in establishing quality connection mechanisms with substantial linkage with farmers and constructing an evaluation system for the linkage quality of tie strength and tie duration. For example, evaluation indexes such as trust levels of farmers in cooperative enterprises, identification levels of farmers on relationship reciprocity, income increase levels of farmers, and technology sharing of cooperation can be established.

Through econometric analysis, it is safe to conclude that tie strength has a promoting effect on the stability of contract farming. This conclusion is consistent with the view of Maloku et al. that relationship quality (satisfaction, commitment, and trust) is conducive to acquiring better competitive advantages [

48]. Specific research results show that interaction and reciprocity intensities (including satisfaction level) have a significantly positive influence on trust level, which has a further significantly positive influence on farmer contract renewal willingness. Also, Maloku and Corsten found that trust plays an important role in cooperative relationships [

48,

49]. Likewise, Dlamini-Mazibuko found that satisfaction is a prerequisite for trust [

50]. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the interactions and reciprocity between enterprises and farmers, and under a certain level of trust, the stability of their cooperation can be significantly improved. However, Maloku argued that satisfaction level is a trivial factor in contract farming [

48]. Analysis of the mediating effect shows that perceived economic value is an important pathway of tie strength promoting the stability of cooperation, which indicates that factors of price, yield, and cost play a key role in the continuous and sustainable participation of farmers in contract farming. This insight has complemented the argument that trust has a direct influence on contract farming.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

Based on survey data from farmers, this study has empirically investigated three dimensions of supply chain tie strength, perceived economic value, and contract renewal willingness of farmers using structural equation modeling, with the following results:

(1) Interaction and reciprocity intensities have a significantly positive influence on trust levels. That is, more frequent interactions between agricultural enterprises and farmers will bring about more intensive reciprocity and higher trust levels between them, with a more significant influence on reciprocity intensity.

(2) Trust level has a significantly positive impact on farmer contract renewal willingness. The total effect of trust level on contract renewal willingness has a value of 0.637, which is equal to the direct effect value of 0.475 (trust level → contract renewal willingness) plus the pathway mediating effect value of 0.162 (trust level → perceived economic value → contract renewal willingness).

(3) Reciprocity and interaction intensities have an indirect impact on contract renewal willingness through trust level, with indirect influence effect values of 0.168 and 0.410, respectively.

6.2. Policy Recommendations:

Based on the above conclusions, we propose the following policy recommendations. Firstly, policymakers should provide agricultural enterprises, farmer cooperatives, and farmers with financial support, tax relief, and incentive mechanisms and encourage them to participate in the establishment and operation of the agricultural supply chain actively. Secondly, trust relationships between enterprises and farmers should be fostered through enhanced interactions and communication. Cooperative meetings, training, and communication activities should be regularly carried out among partners to strengthen their communication and cooperation. For example, enterprise workers can carry out regular technical training and guidance for farmers and improve farmers’ technical trust in enterprises through regular field demonstrations combined with knowledge explanations. Also, enterprise values and cultures should be actively delivered to increase the identification trust of farmers in enterprises. Thirdly, win-win cooperative mechanisms of mutual benefits between enterprises and farmers should be advocated on the basis of rational reciprocal relationships. Enterprises should proactively employ reciprocity policies and go beyond their self-interests, allocating more value-added benefits in the industry chain to farmers in a stable and sustainable manner. At the same time, fair benefit distribution mechanisms should be established, and supervision and evaluation measures should be strengthened to ensure that the legitimate rights and interests of farmers are protected.

6.3. Limitations and Prospect

Although this study has conducted theoretical and empirical analyses in a systematic way, there are still some limitations to be addressed. Firstly, this study has explored the construction of relationships from the perspective of farmers without taking into account the different possible views of agricultural enterprises and cooperatives on the nature of cooperative relationships. Secondly, the limitations of this paper lie in its research scope. In this study, only supply chains in the plant industry in northern China have been focused on, and the research results of this paper can provide a reference for China and other developing countries. Future studies can expand the scope of their investigations to enrich their research outcomes. Lastly, this study has only involved research dimensions of tie strength, such as trust level, interaction intensity, and reciprocity intensity, without considering other dimensions like closeness level. In future studies, these dimensions should be further explored.

Author Contributions

Z.G. contributed to the methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, resources, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation. X.L. contributed to the methodology, software and data curation. X.Z. contributed to the conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research on Improving Grassland Ecological Compensation Mechanism under the Strategyof Revitalizing Pasturing Areas (grant number No.19BJY043).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Minten, B.; Randrianarison, L.; Swinnen, J.F. Global retail chains and poor farmers: Evidence from Madagascar. World development 2009, 37, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S.; Minot, N.; Hu, D. Impact of contract farming on income: linking small farmers, packers, and supermarkets in China. World development 2009, 37, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. As you sow, so shall you reap: The welfare impacts of contract farming. World development 2012, 40, 1418–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.M.; Bellemare, M.F. Smallholder farmers and contract farming in developing countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahaman, A.; Abdulai, A. Vertical coordination mechanisms and farm performance amongst smallholder rice farmers in northern Ghana. Agribusiness 2020, 36, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.; Runsten, D. Contract farming, smallholders, and rural development in Latin America: the organization of agroprocessing firms and the scale of outgrower production. World development 1999, 27, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Moustier, P.; Loc NT, T. Economic impact of direct marketing and contracts: the case of safe vegetable chains in northern Vietnam. Food Policy 2014, 47, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F. Research on modern agricultural industrialization patterns and mechanism innovation based on investigation of agricultural enterprises in Taizhou, Jiangsu. Acta Agriculturae Shanghai 2013, 29, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi, F.; Sciancalepore, V.D. Dynamics of structural change in agriculture, transaction cost theory and market efficiency: The case of cultivation contracts between agricultural enterprises and the food industry. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2022, 10, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Delgado, M.S. The transition to modern agriculture: Contract farming in developing economies. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2014, 96, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruml, A.; Qaim, M. Effects of marketing contracts and resource-providing contracts in the African small farm sector: Insights from oil palm production in Ghana. World development 2020, 136, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, D.O.; Veettil, P.C.; Qaim, M. Farmers’ preferences for supermarket contracts in Kenya. Food Policy 2017, 68, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N.; Giné, X; Karlan, D. Finding missing markets (and a disturbing epilogue): Evidence from an export crop adoption and marketing intervention in Kenya. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2009, 91, 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, H.H. The problem of low contract compliance rate in grain transactions in China. China: An International Journal 2013, 11, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunte, S.; Wollni, M.; Keser, C. Making it personal: breach and private ordering in a contract farming experiment. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2017, 44, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Cao, E. Risk pooling cooperative games in contract farming. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie 2021, 69, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.L. The cooperative relationship between smallholders and rural brokers in contract farming: the evolutionary game model analysis. Journal of Interdisciplinary Mathematics 2017, 20, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Cao, E. Contract farming problems and games under yield uncertainty. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2020, 64, 1210–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Haugland, S.A.; Magno, F. Fairness and behavioral intentions in discrete B2B transactions: a study of small business firms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 2021, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, S.; Ribeiro, P.F.; Romão, S.Z. Determinants of contract renewals in business-to-business relationships. RAUSP Management Journal 2021, 55, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Expanding business-to-business customer relationships: Modeling the customer's upgrade decision. Journal of marketing 2008, 72, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. American journal of sociology 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, P.V.; Campbell, K.E. Measuring tie strength. Social forces 1984, 63, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, N.C.; Sauer, V.; Ellison, N. The strength of weak ties revisited: Further evidence of the role of strong ties in the provision of online social support. Social Media+ Society 2021, 7, 20563051211024958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, S.; Walker, D. Tie strength, embeddedness, and social influence: A large-scale networked experiment. Management Science 2014, 60, 1352–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Huppertz, J.W.; Khare, A. Customer complaining: the role of tie strength and information control. Journal of retailing 2008, 84, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattie, H.; Engø-Monsen, K.; Ling, R.; Onnela, J.P. Understanding tie strength in social networks using a local “bow tie” framework. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, B.; O’toole, T. Classifying relationship structures: relationship strength in industrial markets. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 2000, 15, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A. Variations in relationship strength and its impact on performance and satisfaction in business relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 2001, 16, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, W. The dynamics of social capital: Examining the reciprocity between network features and social support. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2021, 26, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, C.W.; Lee, S.K. Reconsidering ‘ties’: The sociotechnical job search network. International Journal of Business Communication 2023, 60, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, S.; Schlereth, C. Predicting tie strength with ego network structures. Journal of Interactive Marketing 2021, 54, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, L.M.; Joglekar, S.; Quercia, D. Multidimensional tie strength and economic development. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 22081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapna, R.; Gupta, A.; Rice, S.; Sundararajan, A. Trust and the strength of ties in online social networks. MIS quarterly 2017, 41, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.; Thuillier, D. The success of international development projects, trust and communication: an African perspective. International journal of project management 2005, 23, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Duarte, H. Repairing public trust through communication in health crises: a systematic review of the literature. Public Management Review 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Krueger, F. Default matters in trust and reciprocity. Games 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.; Greiner, B.; Ockenfels, A. Engineering trust: reciprocity in the production of reputation information. Management science 2013, 59, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, M.M.; Stout, L.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and the behavioral foundations of corporate law. U. Pa. L. Rev. 2000, 149, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D.; Van Lange, P.A. Trust, conflict, and cooperation: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin 2013, 139, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietsman, M.L.; Mostert, P.; Svensson, G. A multidimensional approach to the outcomes of perceived value in business relationships. European Business Review 2020, 32, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, K.; Wu, L. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers' perceptions. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 738, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. An empirical examination of the determinants of mobile purchase. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 2013, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.A.; Kuo, T.H.; Lin, C.; Lin, B. The mediate effect of trust on organizational online knowledge sharing: An empirical study. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making 2010, 9, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleemann, L. The relevance of business practices in linking smallholders and large agro-businesses in Sub-Sahara Africa. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2016, 19, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Shahraki, A.A. Exploring the Mutual Relationships between Public Space and Social Satisfaction with Case Studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, H. Intentions of Farmers to Renew Productive Agricultural Service Contracts Using the Theory of Planned Behavior: An Empirical Study in Northeastern China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloku, S.; Çera, G.; Poleshi, B.; Lushi, I.; Metzker, Z. The effect of relationship quality on contract farming: The mediating role of conflict between trading partners in Albania. Economics and Sociology 2021, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsten, D.; Felde, J. Exploring the performance effects of key-supplier collaboration: An empirical investigation into Swiss buyer-supplier relationships. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2005, 35, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini-Mazibuko, B.P.; Ferrer, S.; Ortmann, G. Examining the farmer-buyer relationships in vegetable marketing channels in Eswatini. Agrekon 2019, 58, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).