1. Introduction

Ionizing radiation is routinely utilized for cancer treatment and is often combined with other therapeutic modalities. It is estimated that radiotherapy is applied in more than 50% of cancer patients as radical, adjuvant or palliative treatment [

1,

2].

In recent years, increasing interest has focused on the immunomodulatory properties of radiotherapy and the potential for exploiting this phenomenon for therapeutic benefit. Although the mechanisms of interaction with a patient's immune system have not been fully elucidated, the observed alterations include changes in innate and adaptive immunity, influences on various immune cell subsets, and modifications of the tumor microenvironment [

3].

Of particular interest appears to be the effect of radiotherapy on regulatory T cells (Tregs), a key subpopulation of immunosuppressive cells hampering antitumour immune responses. Preclinical studies harnessing animal models and cell lines have demonstrated that ionizing radiation can promote systemic antitumour immunity through inducing various changes in malignant cells. These include upregulated production of chemokines such as CXCL16 and HMGB1, as well as the release of tumor antigens [

4,

5]. Tumor cells destroyed by radiotherapy may also constitute a source of specific antigens for uptake by dendritic cells and presentation to T lymphocytes [

6].

In murine models, T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells, have been shown to accumulate at tumor sites following high-dose fractionated radiotherapy (8-10 Gy) [

7]. CD8+ T-cell deficiency markedly dampens the therapeutic antitumour efficacy of radiation [

8]. Conversely, suppression of T-cell effector functions, e.g., via whole-body irradiation prior to ablative treatment, negatively impacts the tumor radiological response and intensifies immunosuppression within the tumor microenvironment [

9,

10].

Available data indicate that single high radiation doses in stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (10, 15 or 20 Gy) upregulate inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) expression on T cells, suggesting systemic activation in melanoma patients. A signature of low naive CD8+ T cells and heightened TIM-3 expression before treatment better predicted treatment response [

11]. Moreover, fractionating the dose into smaller fractions (2-7 Gy) appears to elicit only minor, transient increases in Treg counts [

12].

Further studies have shown that altering the dose per fraction or number of fractions can modulate the immune response. Hypofractionated regimens using ablative doses per fraction (>8-10 Gy) may preferentially lead to immunogenic modulation and synergistic effects with immunotherapy [

13]. This is thought to be due to the induction of immunogenic cell death and release of tumor antigens and danger signals that promote dendritic cell maturation and subsequent T-cell priming [

14].

Optimizing radiotherapy parameters such as dose, fractionation, and timing relative to immunotherapy appears vital to tipping the balance from immunosuppression toward an antitumour response. Schaue et al. provided evidence that the removal of Treg cells can impact the generation of radiation-induced antitumour immune responses [

15].

On the other hand, conventional fractionation (1.8-2 Gy/fraction) induces more reproducible Treg expansion, which dampens immunity [

16]. This is possibly due to the increased production of immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGF-beta, which promote Treg proliferation and accumulation [

17].

Additionally, the timing of radiotherapy relative to immunotherapy has been shown to influence outcomes. Preclinical studies indicate that sequencing radiation prior to immunotherapy creates a proinflammatory window of 7-10 days, during which checkpoint blockade occurs synergistically before progressing into an immunosuppressive phase [

18].

Furthermore, as demonstrated by Ratnayake et al., the timing of SBRT administration relative to immunotherapy may influence treatment efficacy. They found that both PFS and OS improved when SBRT was given during the third cycle of immunotherapy [

19].

Optimizing radiotherapy parameters such as dose, fractionation and timing appears vital to tip the balance from immunosuppression toward antitumour immunity. Additional investigations are warranted to determine the precise treatment schedules that prime systemic immunity to improve patient outcomes.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the impact of conventional fractionated radiotherapy (frRT) on systemic regulatory T (Treg) cell levels in patients with malignant skin melanoma. We analysed changes in peripheral blood parameters versus those in a control group and correlated them with patient survival. These results provide novel insights into radiation-induced immune alterations in advanced melanoma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study Participants

Sixty-two patients treated at the Oncology Center in Bydgoszcz, Poland, were enrolled. Participants were divided into two subgroups.

The study group comprised 32 patients with skin melanoma who underwent radical radiotherapy (RTH) of regional lymph nodes. Patients were irradiated with an external beam using the 3D-IMRT conformal technique, with 6 MV/15 MV photon beams at a total dose of 50 Gy or 55 Gy.

Treg levels were determined before commencing RTH and at 1 and 3 months after completing treatment.

The control group included 30 patients in whom malignant melanoma was suspected based on dermatoscopic examination and medical history. These patients were qualified for surgical excision of the suspicious lesion. After histopathological analysis, no neoplastic changes were found in this group. The control group consisted of patients without a prior history of cancer. In the control group, Treg measurements were performed in peripheral blood collected before surgery.

2.2. Blood Sampling and Treg Quantification

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture into tubes containing tripotassium EDTA and the cell antigen stabilization solution TransFix (Cytomark, Great Britain). The samples were stored at 4°C for up to 96 hours before analysis.

Treg levels were determined by direct three-color flow cytometry. One hundred microliters of whole blood was added to tubes containing the following fluorochrome-conjugated anti-human monoclonal antibodies: APC-Cy7-anti-CD4, V500-anti-CD8, PE-Cy7-anti-CD25 and FITC-anti-CD127 (BD Biosciences, USA). After 30 minutes of incubation in the dark at 4°C, erythrocytes were lysed using 2 ml of FACS Lysing Solution (BD Biosciences, USA). The samples were promptly analysed on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

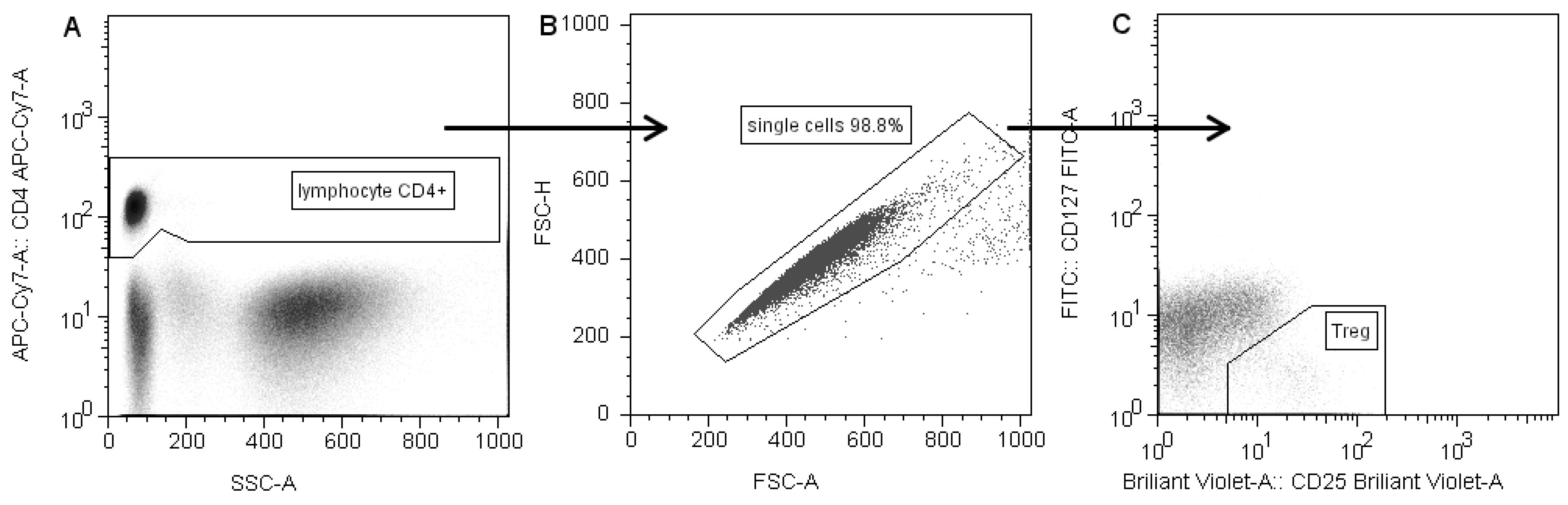

The gating strategy is presented in

Figure 1. CD4+ T cells were selected based on forward scatter (FSC) and CD4 expression, with exclusion of debris and platelets. Doublets were excluded by FSC-A/FSC-H gating [

13]. Next, within the CD4+ population, CD25highCD127low/- cells were gated as Tregs [

14].

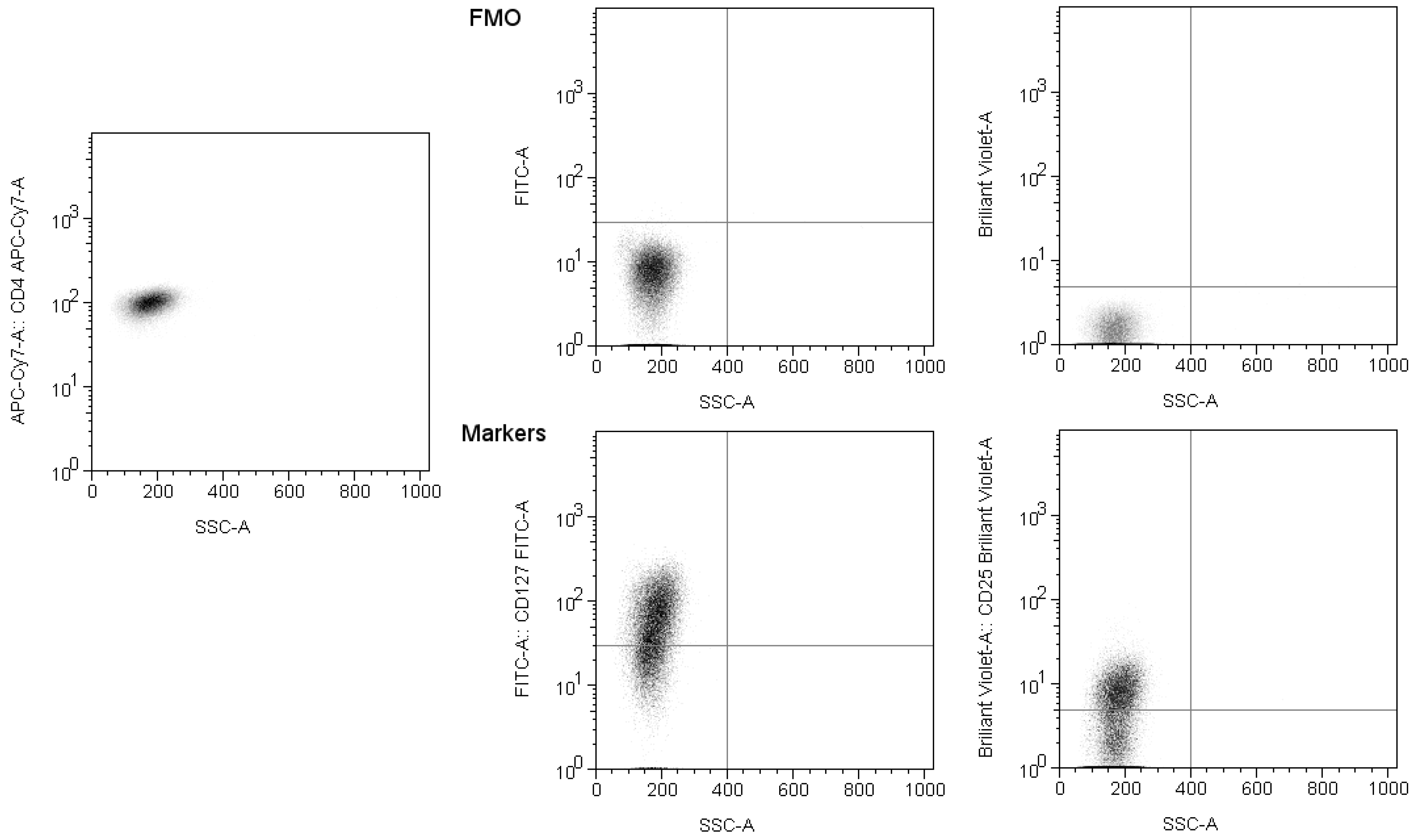

The precise gate setting was achieved using compensation and fluorescence minus one control (

Figure 2). The flow cytometer was calibrated using BD CS&T beads. The data were acquired using BD FACSDiva v8.0 software and analysed with FlowJo v10.

3. Results

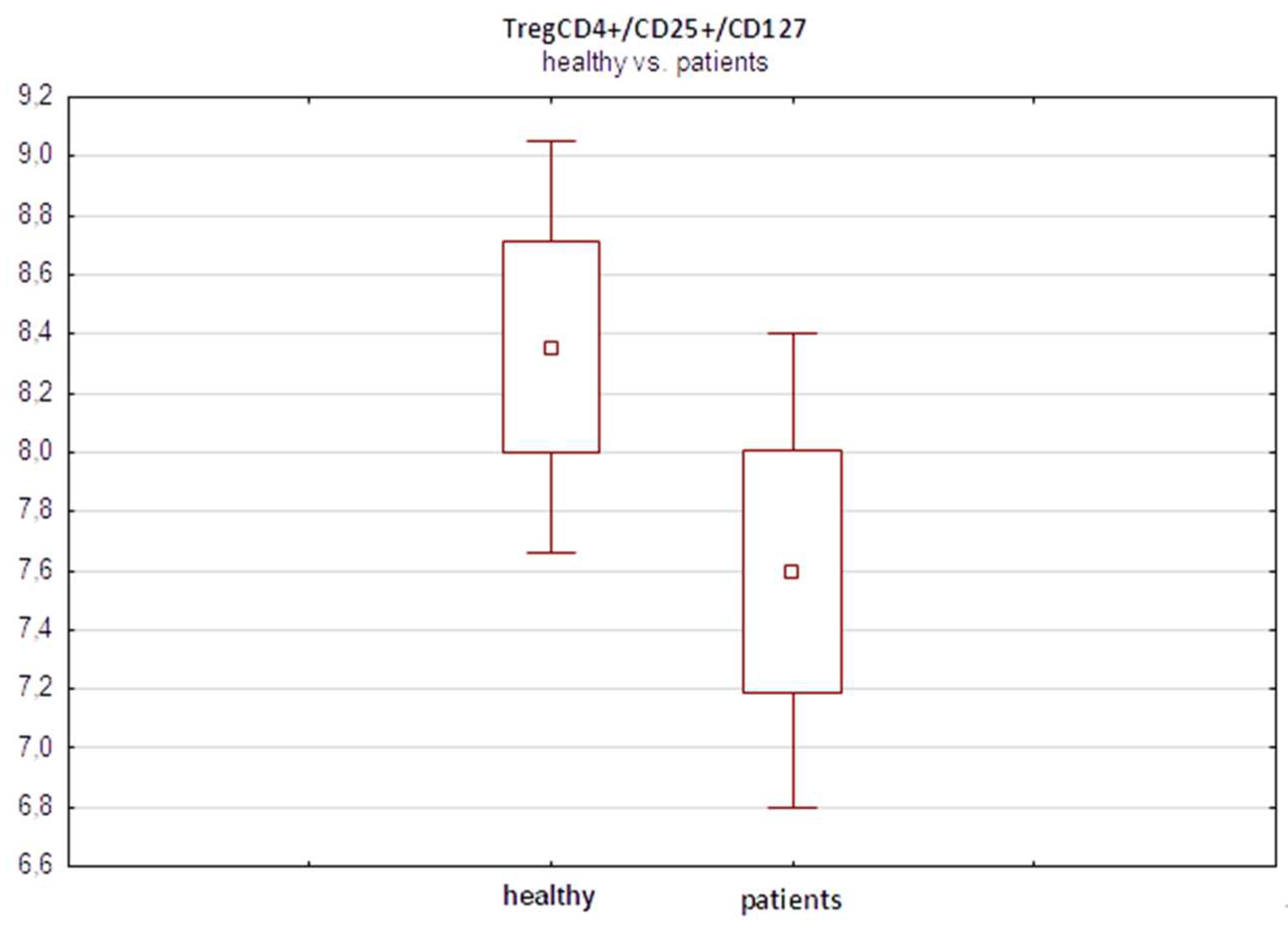

In a preliminary analysis before treatment, we observed a slightly greater percentage of TregCD4+/CD25+/CD127- lymphocytes in the control group of healthy subjects (n=30) than in the melanoma patients (n=32), 8.32% vs 7.4%, respectively (

Figure 3). However, these differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.17, Student’s t test).

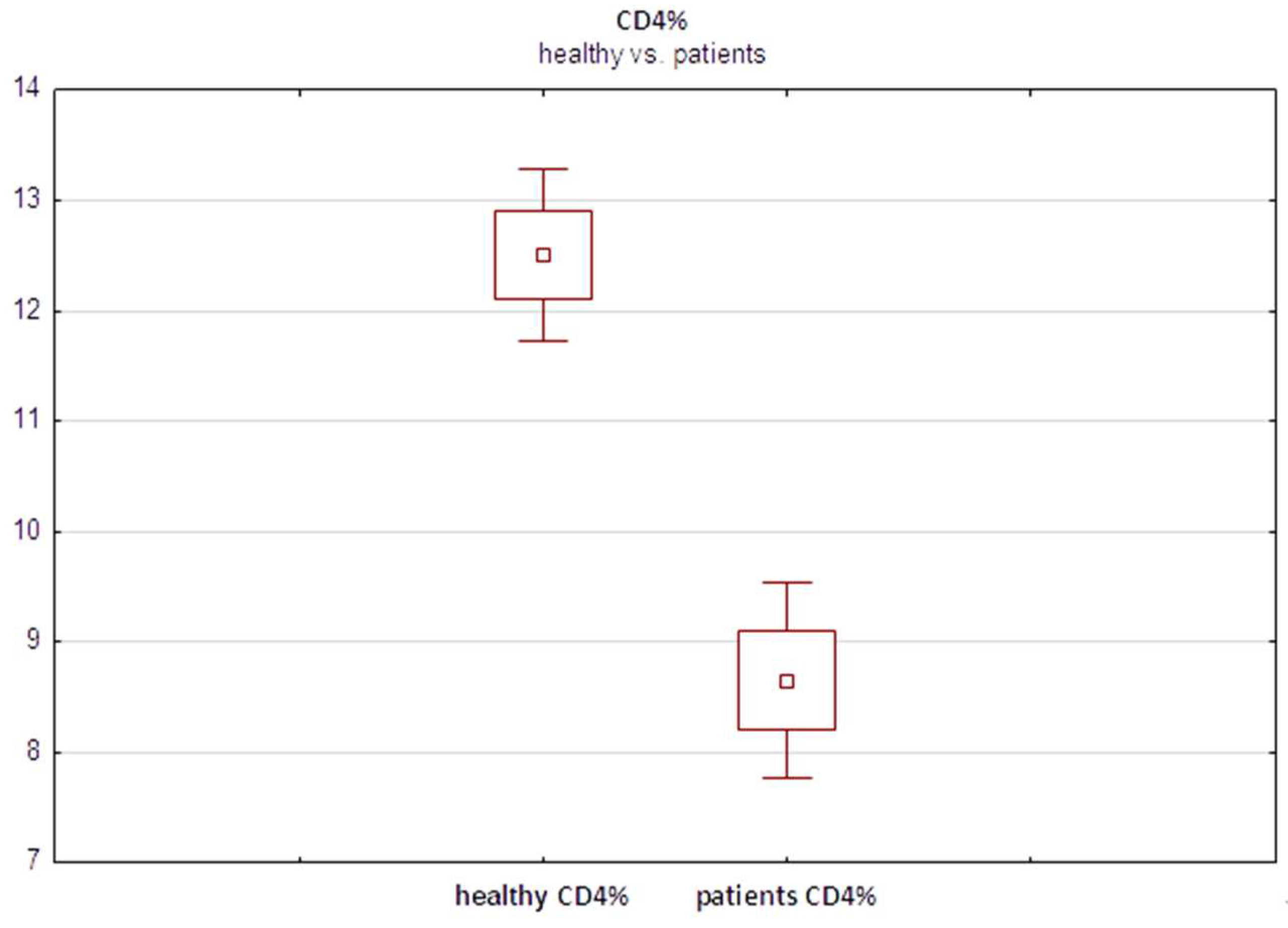

Furthermore, interestingly, the median fraction of total CD4+ T cells was significantly lower in melanoma patients (8.27%) than in healthy controls (12.52%) (

Figure 4) (p=0.001, Student’s t test). These findings suggested relative depletion of the total CD4+ population, of which Tregs constitute only a minor subset, in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. This may result from chronic activation of the immune system in response to advancing malignancy. However, further studies are warranted to elucidate this relationship and the seemingly paradoxical lower Treg content in advanced melanoma patients than in healthy individuals.

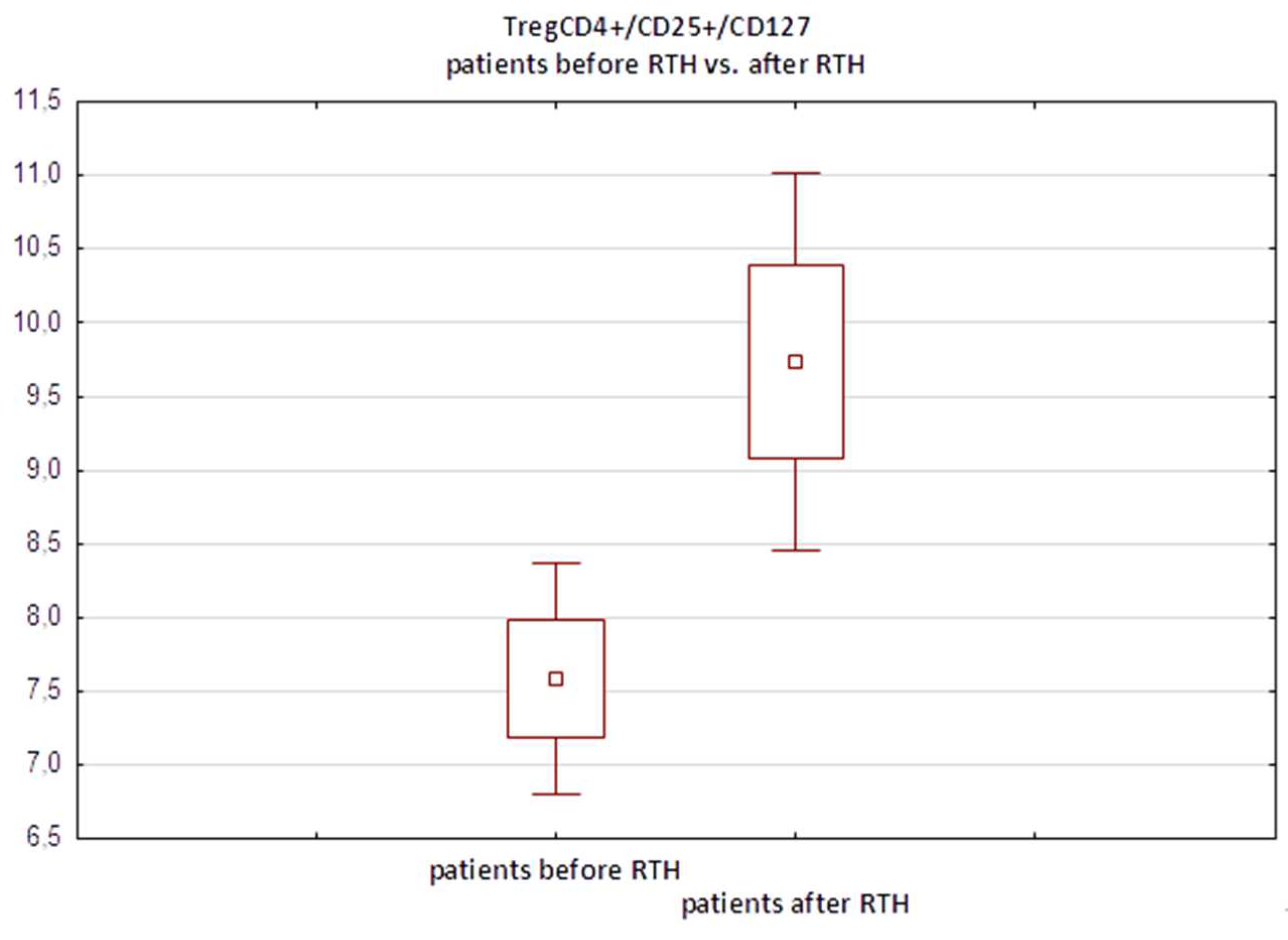

In the subgroup of 32 melanoma patients who underwent regional lymph node radiotherapy, we observed a significant increase in the median percentage of TregCD4+/CD25+/CD127- cells following treatment compared to preradiotherapy values, from 7.94% to 10.01% (p=0.0008, paired Student’s t test). These findings indicate that ionizing radiation induces selective, nearly twofold expansion of this immunosuppressive T-cell subset (

Figure 5).

Notably, the degree of Treg expansion varied among patients, with a subset showing a marked increase >15%, while others demonstrated no change or minimal increase. Analysing factors associated with divergent Treg dynamics could reveal insights into harnessing systemic immunity.

Additionally, we noted a concurrent significant increase in the median total CD4+ T-cell fraction postradiotherapy (from 8.27% to 11.71%, p=0.001), signifying a broader reinvigoration effect on this immune cell population by ionizing radiation (

Figure 6). However, increases in CD4+ T cells also vary among patients and do not always correlate precisely with elevated Treg counts.

Further analyses of additional lymphocyte subsets revealed no significant changes in median CD8+ cytotoxic T cells following radiotherapy. However, the memory CD8+ T-cell population decreased slightly. These findings indicate that conventional fractionated radiotherapy induces specific alterations in certain systemic lymphocyte pools. Additional studies analysing NK cells and B cells are warranted.

Survival analysis revealed that patients who responded to radiotherapy with coordinated increases in both Treg and CD4+ percentages had markedly improved prognoses, with a median overall survival (OS) of 27.8 months versus 13.1 months in nonresponders (

Figure 7) (p=0.001, log-rank test).

In a small subset of patients exhibiting coordinated increases in both Treg and CD4+ percentages after radiotherapy, markedly prolonged survival times of more than 40 months were observed. The results for this subset (n=5) are shown in

Table 1. The underlying features of this subset associated with excellent outcomes merit further study.

Conversely, patients displaying concurrent decreases in Treg and CD4+ T-cell counts postradiotherapy demonstrated poor survival, with a median OS of only 6.5 months (

Table 2). Again, additional factors likely contribute to poor outcomes in these patients.

In summary, our results demonstrated that systemic alterations induced by conventional fractionated radiotherapy preferentially expand immunosuppressive Tregs and CD4+ cells. The coordinated dynamics of these subsets correlate with divergent clinical outcomes, emphasizing the importance of tailored immune modulation. Additional analyses are warranted to elucidate predictors of patient response to guide personalized therapy.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrating significant increases in the Treg and CD4+ lymphocyte fractions after radiotherapy in melanoma patients are consistent with the literature. Similar increases in Tregs after irradiation have been observed in preclinical animal models [

21] as well as in clinical studies of various cancers, such as rectal cancer [

22] and head and neck cancer [

23]. Persa et al. also reported that ionizing radiation can induce Treg expansion under physiological and pathological conditions [

24].

The proposed mechanisms underlying this phenomenon include increased resistance of Tregs to radiation-induced apoptosis compared to that of other lymphocytes [

22] and upregulated production of certain chemokines, such as CCL22, after RT, which attracts circulating Tregs to the tumor microenvironment [

23]. Additionally, tumor cells damaged by radiation release antigens for uptake and presentation by T cells [

25]. Muroyama et al. showed that stereotactic radiotherapy increases the pool of immunosuppressive Tregs in the tumor microenvironment [

26]. This may explain the poorer prognosis in patients with concurrent decreases in Treg and CD4+ fractions after radiotherapy in our study.

Interestingly, we observed a greater percentage of Tregs in the healthy control group than in the melanoma patient group, contrary to findings indicating that elevated systemic Treg levels are an adverse prognostic factor in malignancies. A probable explanation is that the advanced melanoma tumors in our cohort exhibited active Treg-mediated suppression, a phenomenon described in the literature [

27]. However, further studies in larger populations are necessary to elucidate the intricate relationship between tumors and the immune system.

Notably, patients exhibiting coordinated expansion of Tregs and total CD4+ cells after radiotherapy demonstrated markedly improved survival compared to nonresponding patients. In contrast, concurrent decreases in Treg and CD4+ fractions after radiotherapy correlated with unfavorable prognoses. Our data indicate the prognostic utility of monitoring the dynamics of systemic lymphocyte subsets in irradiated melanoma patients. An immune signature of coordinated Treg/CD4+ rise appears to herald clinically beneficial effects, while decreased levels may signal impaired antitumour immunity. Although expanded Tregs likely retain their immunosuppressive function, an overall increase in CD4+ predominance can overcome this alteration and promote cytotoxic Th1 responses [

28]. Elucidating the precise mechanisms governing this phenomenon warrants further investigation.

The intriguing findings of divergent clinical outcomes based on circulating T-cell dynamics deserve additional study. In particular, determining why some patients overexpress lymphocyte subsets while others demonstrate depletion may reveal insights into harnessing systemic immunity. One hypothesis is that intrinsic tumor biology and microenvironmental factors influence the immune response to radiotherapy. Patients with more immunogenic tumors and fewer immunosuppressive mechanisms at baseline may undergo productive immune activation upon irradiation. In contrast, nonresponding patients may harbor tumors adjacent to subverting immunity despite radiotherapy [

29]. Further analyses incorporating tumor genomic and transcriptomic profiles along with circulating biomarkers could aid in testing this hypothesis.

Previous research has shown that radiation-induced immune modulation is governed by various factors, such as dose, fractionation, sequencing with other therapies, and intrinsic radiosensitivity [

30,

31]. Hypofractionated high-dose regimens appear to elicit abscopal responses more readily than conventional fractionation [

32]. This difference may be related to differences in lymphocyte apoptosis induction between regimens. Additionally, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) induces greater CD8+ T-cell infiltration and PD-L1 upregulation than does conventional radiotherapy [

33]. Animal studies have revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between dose/fraction and immune effects [

34]. Identifying the optimal dose to shift the balance from immunosuppression toward antitumour immunity appears vital.

The sequential rather than concurrent combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapy has demonstrated superior outcomes in clinical and preclinical studies [

35,

36]. Specifically, SBRT followed by anti-PD1 therapy results in hyperprogression when given concurrently [

37]. The timing likely relates to cycles of immune activation and subsequent checkpoint inhibition. Finally, intrinsic tumor radiosensitivity may impact radiation-induced immunogenic modulation and warrants investigation.

Overall, our findings reveal significant alterations in circulating lymphocyte subsets induced by conventional fractionated radiotherapy in melanoma patients. The data indicate that tailored modulation of systemic immunity may improve the efficacy of combination regimens. Monitoring T-cell dynamics provides an opportunity for response-adapted therapy. Additional studies elucidating the complex interplay between radiotherapy parameters and antitumour immunity are warranted to improve clinical outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that conventional fractionated radiotherapy induces specific alterations in systemic T-cell subsets, preferentially expanding immunosuppressive Tregs and CD4+ cells. The coordinated dynamics of these populations correlate with significantly divergent clinical outcomes, emphasizing their prognostic utility.

In particular, concurrent increases in circulating Tregs and CD4+ T cells following radiotherapy are associated with markedly improved survival times, whereas decreases in these parameters correlate with poor outcomes.

Moreover, our findings reveal a complex relationship between advanced melanoma and baseline systemic immunity that warrants further investigation. We observed a slightly greater Treg fraction in healthy controls than in melanoma patients, contrary to the finding that elevated Treg levels are an adverse prognostic marker.

Overall, monitoring changes in circulating lymphocyte subsets allows response-adapted therapy in irradiated melanoma patients. Tailoring radiotherapy parameters such as dose and sequencing with immunomodulators may shift the balance from immunosuppression toward productive antitumour immunity based on an individual’s immune response signature.

Additionally, intrinsic features of the tumor likely govern the immune effects of ionizing radiation. Incorporating genomic, transcriptomic and microenvironmental profiling could reveal insights into the subset of patients likely to benefit from rationally designed regimens.

Ultimately, deciphering and harnessing the systemic immune alterations induced by radiotherapy will be key to improving outcomes for melanoma patients. Our study established circulating T-cell dynamics as a tool to guide personalized combinatorial therapy based on individual response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., A.B., K.R.; methodology, S.S., L.G., A.B.; software, L.G. and Z.D.; validation, A.W. and E.Z.; formal analysis, Z.D.; investigation, S.S., L.G., E.Z.; resources, A.B.; data curation, L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, K.R.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, K.R.; project administration, K.R.; funding acquisition, K.R. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nicolaus Copernicus University “Excellence Initiative-Research University” Emerging Fields: “Applying New Technologies and Artificial Intelligence in Oncology”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń (opinion no. KB/136/2016 of 23.02.2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Prior to commencing the research, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research was conducted with respect to the fundamental rights of the participants.

Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

References

- Delaney, G.; Jacob, S.; Featherstone, C.; Barton, M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. Cancer 2005, 104(6), 1129-1137. [CrossRef]

- Begg, A.C.; Stewart, F.A.; Vens, C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11(4), 239-253. [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Ng, B.; Devitt, M.L.; Babb, J.S.; Kawashima, N.; Liebes, L.; Formenti, S.C. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 58(3), 862-870. [CrossRef]

- Garnett, C.T.; Palena, C.; Chakraborty, M.; Tsang, K.Y.; Schlom, J.; Hodge, J.W. Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2004, 64(21), 7985-7994. [CrossRef]

- Reits, E.A.; Hodge, J.W.; Herberts, C.A.; Groothuis, T.A.; Chakraborty, M.; Wansley, E.K.; Camphausen, K.; Luiten, R.M.; de Ru, A.H.; Neijssen, J. et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203(5), 1259-1271. [CrossRef]

- Lugade, A.A.; Sorensen, E.W.; Gerber, S.A.; Moran, J.P.; Frelinger, J.G.; Lord, E.M. Radiation-induced IFN-gamma production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 2008, 180(5), 3132-3139. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Auh, S.L.; Wang, Y.; Burnette, B.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Beckett, M.; Sharma, R.; Chin, R.; Tu, T.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Fu, Y.X. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 2009, 114(3), 589-595. [CrossRef]

- Farhood, B.; Najafi, M.; Mortezaee, K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234(6), 8509-8521. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chan, C.K.; Weissman, I.L.; Kim, B.Y.S.; Hahn, S.M. Immune Priming of the Tumor Microenvironment by Radiation. Trends Cancer 2016, 2(11), 638-645. [CrossRef]

- Klug, F.; Prakash, H.; Huber, P.E.; Seibel, T.; Bender, N.; Halama, N.; Pfirschke, C.; Voss, R.H.; Timke, C.; Umansky, L. et al. Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS+/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2013, 24(5), 589-602. [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, G.; Reinwald, S.; Edwards, J.; Wong, N.; Yu, D.; Ward, R.; Smith, R.; Haydon, A.; Au, P.M.; van Zelm, M.C.; Senthi, S. Blood T-cell profiling in metastatic melanoma patients as a marker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 173, 299-305. [CrossRef]

- Kachikwu, E.L.; Iwamoto, K.S.; Liao, Y.P.; DeMarco, J.J.; Agazaryan, N.; Economou, J.S.; McBride, W.H.; Schaue, D. Radiation enhances regulatory T cell representation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 81(4), 1128-1135. [CrossRef]

- Maecker, H.T.; McCoy, J.P.; Nussenblatt, R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12(3), 191-200. [CrossRef]

- Vanpouille-Box, C., Alard, A., Aryankalayil, M. J., Sarfraz, Y., Diamond, J. M., Schneider, R. J., Inghirami, G., Coleman, C. N., Formenti, S. C., & Demaria, S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat. Comm. 2017, 8, 15618. [CrossRef]

- Schaue, D., Xie, M. W., Ratikan, J. A., McBride, W. H. Regulatory T cells in radiotherapeutic responses. Frontiers Oncol. 2012, 2, 90. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Putnam, A.L.; Xu-Yu, Z.; Szot, G.L.; Lee, M.R.; Zhu, S.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Kapranov, P.; Gingeras, T.R.; Fazekas de St Groth, B. et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203(7), 1701-1711. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Cabrera, R.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C.; Nelson, D. Gamma irradiation alters the phenotype and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2009, 33(5), 565-571. [CrossRef]

- Dovedi, S. J., Adlard, A. L., Lipowska-Bhalla, G., McKenna, C., Jones, S., Cheadle, E. J., Stratford, I. J., Poon, E., Morrow, M., Stewart, R., Jones, H., Wilkinson, R. W., Honeychurch, J., Illidge, T. M. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res. 2014, 74(19), 5458–5468. [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, G., Reinwald, S., Shackleton, M., Moore, M., Voskoboynik, M., Ruben, J., van Zelm, M. C., Yu, D., Ward, R., Smith, R., et al. Stereotactic Radiation Therapy Combined With Immunotherapy Against Metastatic Melanoma: Long-Term Results of a Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108(1), 150–156. [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Song, C.; Li, Y.; Xia, J.; Wu, Y.; Jia, J.; Cui, X.; Yu, S.; Gu, J. Combination of radiotherapy and suppression of Tregs enhances abscopal antitumor effect and inhibits metastasis in rectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8(2), e000826. [CrossRef]

- Dutsch-Wicherek, M.; Chaberek, K.; Makarewicz, A.; Antoni, S.I.; Witwicki, J.; Bielecki, I.; Wicherek, Ł. The analysis of Treg lymphocyte blood percentage changes in patients with head and neck cancer during combined oncological treatment: a preliminary report. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 45(4), 409-413. [CrossRef]

- Hindley, J.P.; Ferreira, C.; Jones, E.; Lauder, S.N.; Ladell, K.; Wynn, K.K.; Betts, G.J.; Singh, Y.; Price, D.A.; Godkin, A.J. et al. Analysis of the T-cell receptor repertoires of tumor-infiltrating conventional and regulatory T cells reveals no evidence for conversion in carcinogen-induced tumors. Cancer Res. 2011, 71(3), 736-746. [CrossRef]

- Deaglio, S.; Dwyer, K.M.; Gao, W.; Friedman, D.; Usheva, A.; Erat, A.; Chen, J.F.; Enjyoji, K.; Linden, J.; Oukka, M. et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204(6), 1257-1265. [CrossRef]

- 24. Persa E, Balogh A, Sáfrány G, Lumniczky K. The effect of ionizing radiation on regulatory T cells in health and disease. Cancer Lett. 2015, 368(2), 252-261. [CrossRef]

- Reits, E.A.; Hodge, J.W.; Herberts, C.A.; Groothuis, T.A.; Chakraborty, M.; Wansley, E.K.; Camphausen, K.; Luiten, R.M.; de Ru, A.H.; Neijssen, J. et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203(5), 1259-1271. [CrossRef]

- Muroyama, Y., Nirschl, T. R., Kochel, C. M., Lopez-Bujanda, Z., Theodros, D., Mao, W., Carrera-Haro, M. A., Ghasemzadeh, A., Marciscano, A. E., Velarde, E., et al. Stereotactic Radiotherapy Increases Functionally Suppressive Regulatory T Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5(11), 992–1004. [CrossRef]

- Fourcade, J.; Sun, Z.; Chauvin, J.M.; Ka, M.; Davar, D.; Pagliano, O.; Wang, H.; Saada, S.; Menna, C.; Amin, R. et al. CD226 opposes TIGIT to disrupt Tregs in melanoma. JCI Insight 2018, 3(14), e121157. [CrossRef]

- Brody, J.R.; Costantino, C.L.; Berger, A.C.; Sato, T.; Lisanti, M.P.; Yeo, C.J.; Emmons, R.V.; Witkiewicz, A.K. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in metastatic malignant melanoma recruits regulatory T cells to avoid immune detection and affects survival. Cell Cycle 2009, 8(12), 1930-1934. [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chu, X.; Tanzhu, G.; Zhou, R. Optimal timing and sequence of combining stereotactic radiosurgery with immune checkpoint inhibitors in treating brain metastases: clinical evidence and mechanistic basis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21(1), 244. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Sun, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gong, Y.; Xie, C. Immunological modulation of the Th1/Th2 shift by ionizing radiation in tumors (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 59(1), 50. [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.; Galloway, A.; Kawashima, N.; Dewyngaert, J.; Babb, J.; Formenti, S.; Demaria, S. Fractionated but Not Single-Dose Radiotherapy Induces an Immune-Mediated Abscopal Effect when Combined with Anti–CTLA-4 Antibody. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5379-5388. [CrossRef]

- 32. Takanen S, Bottero M, Nisticò P, Sanguineti G. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Hypofractionated and Stereotactic Radiotherapy on Immune Cell Subpopulations in Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14(21), 5190. [CrossRef]

- Sturman, M.C. Searching for the Inverted U-Shaped Relationship Between Time and Performance: Meta-Analyses of the Experience/Performance, Tenure/Performance, and Age/Performance Relationships. Journal of Management. 2003, 29(5), 609-640. [CrossRef]

- Dovedi, S.; Adlard, A.; Lipowska-Bhalla, G.; McKenna, C.; Jones, S.; Cheadle, E.; Stratford, I.; Poon, E.; Morrow, M.; Stewart, R.; Jones, H.; Wilkinson, R.; Honeychurch, J.; Illidge, T. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5458-5468. [CrossRef]

- Twyman-Saint Victor, C.; Rech, A.J.; Maity, A.; Rengan, R.; Pauken, K.E.; Stelekati, E.; Benci, J.L.; Xu, B.; Dada, H.; Odorizzi, P.M.; Herati, R.S.; Mansfield, K.D.; Patsch, D.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Schuchter, L.M.; Ishwaran, H. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature 2015, 520(7547), 373-377. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, M.; Huang, Z.; Yu, J.; Meng, X. SBRT combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in NSCLC treatment: a focus on the mechanisms, advances, and future challenges. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Gray, M.; Martínez-Pérez, C.; Kay, C.; Pang, L.; Fraser, J.; Poole, A.; Kunkler, I.; Langdon, S.; Argyle, D.; Turnbull, A. Precision Medicine and the Role of Biomarkers of Radiotherapy Response in Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).