1. Introduction

Raw material extraction is essential to meet the growing demands of industrialisation and technological advancement. These raw materials, such as metals, minerals, and fossil fuels, form the backbone of modern economies, powering various sectors like construction, manufacturing, energy production, and transportation. They are crucial for the production of goods and infrastructure, making them indispensable for economic development and societal progress. However, sustainable and responsible extraction practices are increasingly important to balance resource availability with environmental conservation and social considerations.

In addition, the escalating need for a wide range of raw materials, including lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earth elements, and copper, has been catalysed by the global pursuit of carbon neutrality [

1]. The extraction of these raw materials plays a pivotal role in enabling the transition to low-carbon technologies. For instance, lithium-ion batteries, which heavily rely on lithium, cobalt, and nickel, power electric vehicles and store renewable energy, ensuring grid stability and sustainability [

2]. The heightened demand for these critical minerals has led to a significant upswing in mining activities [

3,

4], and now, the sustainable sourcing and responsible extraction of these raw materials has become imperative [

5]. Transparent disclosure of mining practices, environmental impact assessments, and social responsibility initiatives will hold mining companies accountable for their actions [

6]. By embracing process transparency, the mining industry can mitigate the negative impacts of raw material extraction, foster responsible mining practices, and contribute to global carbon neutrality goals [

7,

8]. This requires new methods and approaches that enable efficient monitoring of the mining industry, ensuring process transparency to address the challenges effectively.

The transparency of the processes in the mining industry is a challenge. Even when the data about certain operations and environmental pollution are presented, proving the authorities and local community that the data recorded is true and has not been changed is difficult. The main issue is to make sure that the final form of the data presented does not pose discrepancies that might be caused by the data controller or the data processor.

In this paper, a novel approach for ensuring data integrity and public auditability in the mining industry by using IOTA-based distributed ledger is presented. The provenance of data recorded through such a system will ensure that the data is immutable and traceable. To the best of current knowledge, this is the first attempt to define the methodology and to evaluate the approach in a live environment. The utilization of the IOTA Tangle as a verifiable data registry has proven to be effective for security control purposes. This marks a significant step in applying new technologies to practical, real-world challenges.

This paper presents a comprehensive approach to enhance traceability and accountability within the mining industry through blockchain technology. The approach has been validated within the DIG_IT [

9] project funded by the European Commission that aims to address sustainable use of resources, by developing technology for monitoring of mining operations. The project facilitates Blockchain network to set up monitoring of sustainability compliance of raw material production, as a first step of certification for labelling sustainable material extraction.

However, it is not only transparency and sustainability that are crucial. GDPR compliance, along with technically feasible autonomous monitoring, is essential for ensuring the sustainable extraction of raw materials in the mining industry. More specifically, the methodology proposed in this manuscript for traceability in mining industry contributes with:

Definition of solution for achieving end to end traceability in the mining industry.

Evaluation of the solution in real-world deployment by using IOTA framework technologies and data collections from the mining operations.

Exercising certification and labelling of sustainable material production.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the Related Work, which delves into current research within the existing literature. This section identifies gaps in the field that the proposed approach aims to address, offering a comprehensive overview of how the current study contributes to and differs from existing knowledge. The problem definition can be found in

Section 3. This section comes up with main challenges such as end-to-end security concerns, complex data collection, and ethical considerations. The proposed IOTA-based Traceability Approach is given in

Section 4, which introduces the main solution proposed, leveraging Decentralised Identities and encryption mechanisms to ensure data integrity and confidentiality. The approach is evaluated in

Section 5 together with methodology and application of proposed approach within the DIG_IT Project. Other topics presented in this section are encompassing architecture, end-to-end traceability deployment, encryption for datasets, and permanent DLT storage nodes. This model is extended to include certification and labelling of sustainable material production within the mining sector. In

Section 6, the paper discussess the broader implications of the research and outlines potential directions for future work. Conclusiones can be found in

Section 7.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the domain of effective monitoring of environmental sustainability in the mining industry by using Distributed Ledger Technology. In general, the scalability and energy consumption are among the foremost concerns, as Blockchain networks, particularly proof-of-work-based systems, can be resource-intensive [

10]. While most of the Blockchain strive to move to more energy and price efficient algorithms, the application of these algorithms in real-world use cases for sustainable mining industry is very scarce. In [

11] it is suggested to use Proof-of-Stake Blockchain technology to impose sustainable management of natural resources in two use cases deforestation and groundwater management. The paper proposes tokenized approach with incentive made to land managers for changing land cover to forest or for maintaining forest. The main methodology in this paper is based on the innovative monitoring capacity using remote sensing data and analysis and Blockchain to establish an effective reward/penalty system and improve compliance involving pre-minted “Global Forest Coins (GFC)”; and promote behaviour inconsistent with sustainable development objectives (coercion and corruption) through a decentralised design. This study describes the Blockchain infrastructure, without going into the technical details, deployment issues, and security implications which could be a main point of failure of data traceability and integrity. Similar tokenisation incentivised models are examined in [

12].

In [

13], a system architecture for mining machine inspections using off-the-shelf mobile devices and integrating IoT and blockchain technologies is proposed. This study is very relevant to this research, but the proposed approach is focused on the collection of the data from the inspector carrying the device, considered as a trusted source of data. This means that real time monitoring is not possible unless in cases when the inspector is doing in field measurements.

Blockchain research and application for raw material extraction for mining is underdeveloped in comparison to other supply chain traceability, such as textile [

14], food [

15], pharma [

16]. Currently most of the research and policy work is focused on the analysis of how the distributed blockchain technology can counter specific supply chain and operations management challenges [

17,

18]. OECD reports provide recommendations and due diligence guidance for responsible supply chain of minerals [

19].

The paper presented in [

20] describes a traceability system based on blockchain technology for storage and query of product information in supply chain of agricultural products. Authors provide performance analysis and practical application. The results show that the system improves the query eficiency and the security of private information, guarantees the authenticity and reliability of data in supply chain management, and meets actual application requirements. In [

21], authors present a efficient traceability system for managing products in the fishery supply chain. Negligence in products’ traceability can result in food fraud that may adversely affect the consumer’s health.

Regarding the usage of IOTA ledger, authors in [

22] hightlights main features of the IOTA 2.0. IOTA Tangle initial version faced issues with centralization and scalability. IOTA 2.0 addresses these by removing the centralized coordinator and introducing improvements to enhance decentralization and scalability, along with providing a technical overview and future research directions for IoT applications. The work presented in [

23] leverages IOTA Tangle as part of Microgrid Transactive Energy Systems, demostrating that this technology can be cost-effective for any domain.

Through Blockchain-based systems, each stage of mineral production can be recorded and tracked, ensuring that minerals are ethically sourced and free from conflict zones. Nevertheless, the actual implementation of these approaches in practice is lacking and does not meet a reasonable number of deployments to be considered as a practice.

4. Distributed Ledger Technology-based traceability approach

The goal of this section is to elaborate on the main technical, and non-technical solutions for the identified problems and provide methodological approach of the data collection and preservation in the DLT network for the public transparency and auditability in the mining industry.

4.1. End to end security

Distributed Ledger Technology represents a larger group of mechanisms combined together and protected with reliable, public, private key signature technology, connected to a Blockchain [

28]. End-to-end traceability, a critical aspect of ensuring trust and accountability within complex operations like those in the mining sector, can be effectively realised through the synergistic integration of Public Key Infrastructures (PKIs) within the framework of Blockchain technology. Such an end-to-end approach is necessary to be applied in the data provenance of the mining sector and represent viable solutions with the existing technologies. Therefore, the implementation of the public-private key infrastructure requires libraries on the client (device), which signs the data that ends up in the Blockchain. In this paradigm, Blockchain serves as a decentralised and tamper-proof ledger, ensuring the immutability and transparency of transactions.

4.2. Decentralised Identities

Instead of relying on centralised authorities to validate and manage identities, DIDs leverage blockchain's distributed and immutable nature to grant individuals and entities complete control over their identity data. Coupled with Private Key Infrastructure, an additional layer of security is added through the utilisation of cryptographic keys. Each device possesses a pair of cryptographic keys: a public key, which is shared openly, and a private key, which remains securely held by the owner. Each DID is unique and cryptographically secure, empowering devices to authenticate and authorise themselves and sign the payload they are producing. PKI ensures secure communication and digital signatures, enhancing data integrity and authenticity. When combined, DIDs and PKI create a robust foundation for data integrity on the blockchain as follows:

Immutable Identity Verification: DIDs enable entities to substantiate their identity on the Blockchain without disclosing sensitive information. This ensures that only authorised parties gain access to data, maintaining the privacy of users while facilitating seamless transactions.

Secure Access Control: With PKI, private keys act as digital signatures, permitting only authorised individuals to access and interact with specific data. This controlled access ensures data remains accurate and unaltered.

Tamper-Proof Records: Every data update linked to the DID can be documented on the blockchain. This establishes an auditable trail that cannot be modified, providing a reliable source of truth for data integrity.

Data Provenance and Traceability: DIDs and PKI enable the tracking of data origins and changes over time. This proves particularly valuable for the mining industry and raw material supply chain management.

Fraud Prevention and Reduction: The decentralised nature of DIDs and the security of PKI significantly diminish the risk of identity fraud and unauthorised data access.

Smart Contracts and Automation: Blockchain's smart contracts can be integrated with DIDs and PKI, automating processes while ensuring only authorised parties execute actions, thus preserving data integrity.

Cross-Platform Compatibility: DIDs and PKI are not confined to a solitary blockchain network, permitting interoperability across different systems and platforms, thereby further enhancing data integrity and accessibility.

In conclusion, the Decentralised Identities with Blockchain or DLTs technology offers a comprehensive solution for ensuring data integrity. This pairing addresses a fundamental challenge of the end-to-end security, trust and verifiability of the information written in the Ledger from the Blockchain. To streamline even more the data provenance, and enable data secure access to a collected dataset, the data encryption can be imposed by encrypting the chunks of collected datasets. This will be explained in the next subsection.

4.3. Encryption

Based on the actual use case requirements and if the data are sensitive or not, the encryption can be used to encrypt the datasets. Together with DIDs and PKIs this adds an additional layer of protection to safeguard data integrity and prevent unauthorised access, creating a robust blockchain-based traceability framework. By applying advanced encryption techniques, raw data collected from mining operations can be transformed into encrypted formats before being stored on the blockchain. This ensures that even if unauthorised parties gain access to the data, they are unable to decipher its contents without the corresponding decryption keys.

Encrypted datasets provide the flexibility to selectively share specific portions of data with authorised stakeholders. Through cryptographic mechanisms, data owners can grant access to certain parties by providing them with the necessary decryption keys. This controlled data sharing mechanism strikes a balance between transparency and confidentiality, allowing relevant parties to validate information without compromising sensitive details.

Encrypted datasets do not hinder the auditability of transactions on the Blockchain. While the data itself remains encrypted, the transactions and interactions involving the data are transparent and immutable. This preserves the audit trail and accountability attributes inherent to Blockchain technology, assuring the verifiability and authenticity of actions performed on the encrypted data.

The integration of encrypted datasets aligns with data protection regulations as far as the sensitive data are anonymised. It fosters a robust security posture by safeguarding sensitive information from unauthorised access or data breaches. This is particularly crucial in industries like mining, where compliance with privacy regulations is imperative.

Nevertheless, there are challenges when implementing encrypted datasets, in the form of key management and secure storage of decryption keys. Additionally, efficient encryption methods must be chosen to minimise computational overhead while ensuring data security. Striking the right balance between data protection and operational efficiency is essential to achieve optimal results.

5. Evaluation of the proposed model

This sections reports on the evaluation of the proposed model with the focus on methodology and selection of DLT protocol and evaluation of the technology

5.1. Methodology and selection of DLT protocol

To evaluate the proposed approach, the framework is developed and deployed in a real-world environment, where the data are collected from the mines to monitor emissions. This section encompasses the evaluation of the proposed traceability approach. One of the main requirements for monitoring of mining processes is to support a significant number of transactions in near real-time, to allow auditability without delay. The best possible test to be carried out would be an exact simulation or the live deployment of the system.

There are a number of different Distributed Ledger Technology that can be used to achieve the traceability of the data. Permissioned Blockchains (such as Hyperledger Fabric) were not considered simply because they are consortium led DLT, and the trust necessary to be established in the mining industry explicitly requires public audit.

The choice of DLT depends on the desired level of decentralisation, scalability, security, and energy efficiency. These factors are mainly influenced by the consensus mechanism that specific DLT is using. For instance, the Proof of Work (PoW) has high security due to the computational power required to mine blocks, but it consumes a significant amount of energy, and has slower transaction, thus there are processing and scalability concerns that can affect real-time traceability. The main protocols based on PoW are Bitcoin, Litecoin, Ethereum 1.0, etc. Currently, Ethereum shifted to PoS in its latest version.

The Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism consumes less energy, making it more sustainable, it has faster transactions that can improve traceability and data handling speed in compared to PoW. There are centralisation risks as due to the existence of actors in the network with more influence, and it is less secure. There are still gas fees for writing the data but they are less expensive to be used to store the large amounts of data in compare to PoW based Blockchain. For example, for PoS Blockchain such as Polygon (transaction fee 70 Gwei at the moment of writing this paper - approximately 2 EUR). To some extent the problem with the price can be solved by hashing the bigger chunks of data instead of each value, in which case it is hard to understand which value from the whole dataset has integrity issues. The main PoS Blockchains are Ethereum 2.0 (Polygon as Layer two of Ethereum), Polkadot, Avalanche, Cardano, Solana, etc. Of course, there are more ledgers, but these are the most popular ones and with most stable user and transaction base.

Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS) is a consensus mechanism commonly used in blockchain networks where token holders vote to elect a limited number of delegates or validators who are responsible for validating transactions and producing blocks. DPoS aims to improve scalability and energy efficiency compared to traditional PoW networks. There are also a number of interesting DPoS based DLT such as 0BSnetwork and EOSIO.

Blockchains based on the Proof of Authority (PoA) consensus mechanism offers high transaction throughput for efficient traceability, but the network relies on a limited number of approved validators, which means they are not fully decentralised.

In the DLT ecosystem, there are also other algorithms such as Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), offering high throughput for traceability applications, and lower fees. Implementing and understanding the DAG can be complex, and the DAG- based DLT could face different security challenges compared to traditional blockchains. Furthermore, DAG has very high energy efficiency and the current IOTA protocol, has simplified the integration complexity by providing L2 (layer two) Frameworks that helps implementation of different services on top of L1 (layer one, which is a core protocol).

In

Table 1 the comparison of features is given for different DLT, taking into account supported Transactions Per Second (TPS), price, support for DID on L1 or L2, as well as the Hardware library support for devices as the main metrics. The values are taken from relevant research papers and relevant online sources. The below metric cannot be used as comparative performance evaluation, as it would need to have the same data written in different networks, and as gas price is continually changing - repeating the same transaction may result in different transaction fees, which why this analysis is done to justify the selection DLT used to implement the proposed approach. The transaction fee is calculated by multiplying the sum of the gas price and the current value of the token in dollar/ euro.

The reference number of minimum 1000 TPS was taken using the message count from the DIG_IT project. This number can be significantly higher depending on the number of assets, sensors, and processes monitored. At its best the DLT should support as much as possible TPS with as less fees, and it should have an integrated DID framework, and have a support for the embedded devices. From

Table 1, IOTA and EOSIO are the best candidate taking into account the set criteria. The IOTA protocol is selected as it, at the moment of writing this paper, apart from other criteria, provides OEM support and has additional frameworks required to satisfy proposed methodology. More specifically, IOTA protocol includes L2 Frameworks for seamless integration of the decentralised identities (DIDs), it does not impose any fees for writing data in the Ledger, it has encryption schemes (Streams protocol [

29]) for data anchored on the Tangle, it is very energy efficient [

30], and recently there are 32-bit microcontrollers firmware libraries [

31] expansion software package for STM32Cube that runs on the STM32 and includes middleware to enable the IOTA Distributed Ledger Technology functions. In conclusion, there are different Ledgers that could be used to achieve the same traceability goals with certain ratios of scalability, costs, and deployment complexity. IOTA was selected for the evaluation deployment in the real mining environment as it provides feeless, scalable technology which is lightweight to be integrated with IoT devices [

32], with DIDs, encryption and the Ledger developed as L2 Frameworks [

33].

5.2. Evaluation of the proposed methodology in the mining industry (DIG_IT Project)

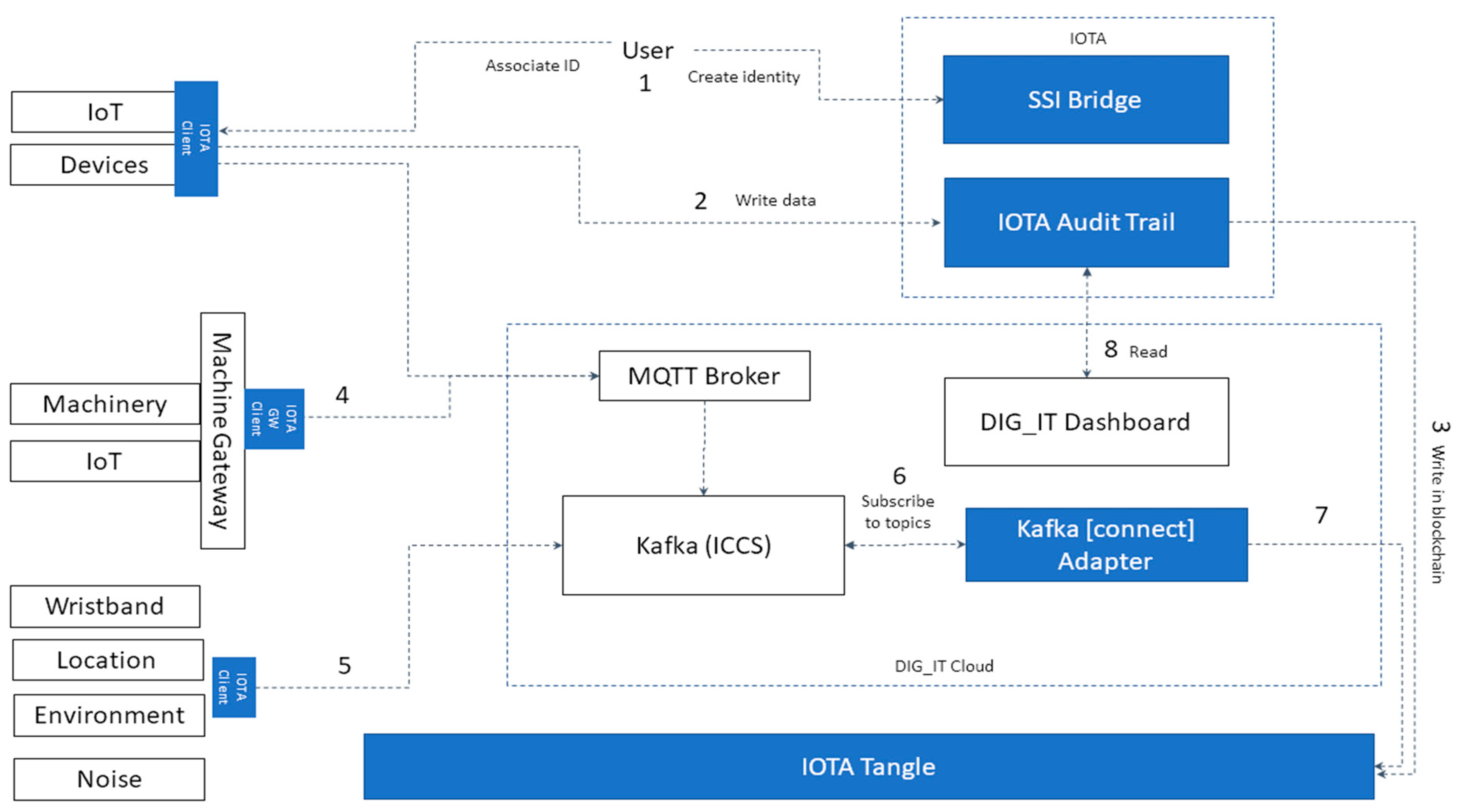

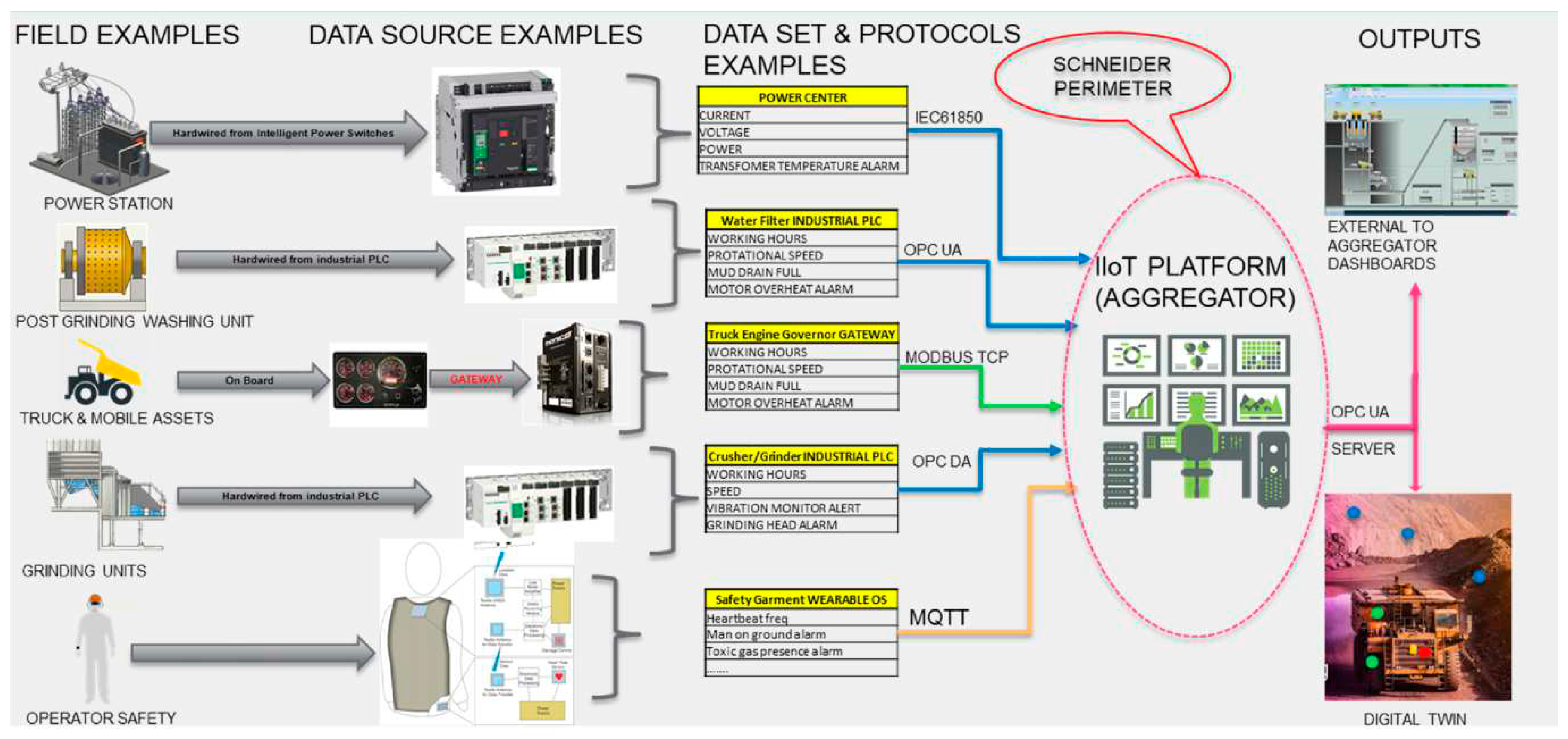

Dig_IT – A human-centred Internet of Things platform for the sustainable digital mine of the future – is a European Commission funded project that aims to address the needs of the mining industry to move towards a sustainable use of resources while keeping people and environment at the forefront of their priorities. In order to achieve that, DIG_IT developed a smart Industrial Internet of Things platform (IIoTp) to improve the efficiency and sustainability of mining operations by connecting cyber and physical systems. The platform collects data from sensors at 3 levels: human, assets, environment and will also incorporate both market real time and historical data (

Figure 1).

Field Examples: These are physical assets or locations where operations are conducted or monitored, like a Power Station, Post Grinding Washing Unit, Truck & Mobile Assets, Grinding Units, and considerations for Operator Safety.

Data Source Examples: These represent hardware devices that gather data from the field examples. They include intelligent power switches, industrial Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), gateways for mobile assets, and wearable devices for safety monitoring.

Data Set & Protocols Examples: The middle section details the kind of data collected (like current, voltage, power, temperature alarms, etc.) and the communication protocols used to transmit this data to the IIoT platform. Protocols mentioned are IEC61850, OPC UA (Unified Architecture), MODBUS TCP, OPC DA (Data Access), and MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport), which are all standard protocols for industrial communication.

Schneider Perimeter: This might indicate that the outlined IIoT ecosystem is within the scope of Schneider Electric's solutions, products, or services.

IIoT Platform (Aggregator): This is likely a software solution that aggregates the data from various sources, processes it, and may also allow for control commands to be sent back to the field assets. It is represented as the central system where all data converges.

Outputs: On the right, the outputs of the IIoT platform are shown. This includes dashboards for data visualization, servers for data processing and storage, and a digital twin, which is a virtual representation of the physical assets, allowing for simulation, analysis, and control.

The Dig_IT project covers a diverse array of mines, each with its unique set of goals and challenges. From underground quarries to expansive open-pit mines, these case studies represent excellence field study for the performance evaluation of the proposed approach. The mines included in the DIG_IT project are Marini Marmi in Italy (underground quarry), La Parrilla mine in Spain (open pit), Titania in Norway (open pit), Hannukainen mine in Finland (open pit), Sotkamo Silver mine in Finland. In the following subsections the deployment of DLT is explained first with the project architecture overview, followed by the implementation of DLT, and description of the approach for certification labelling.

5.3. Architecture

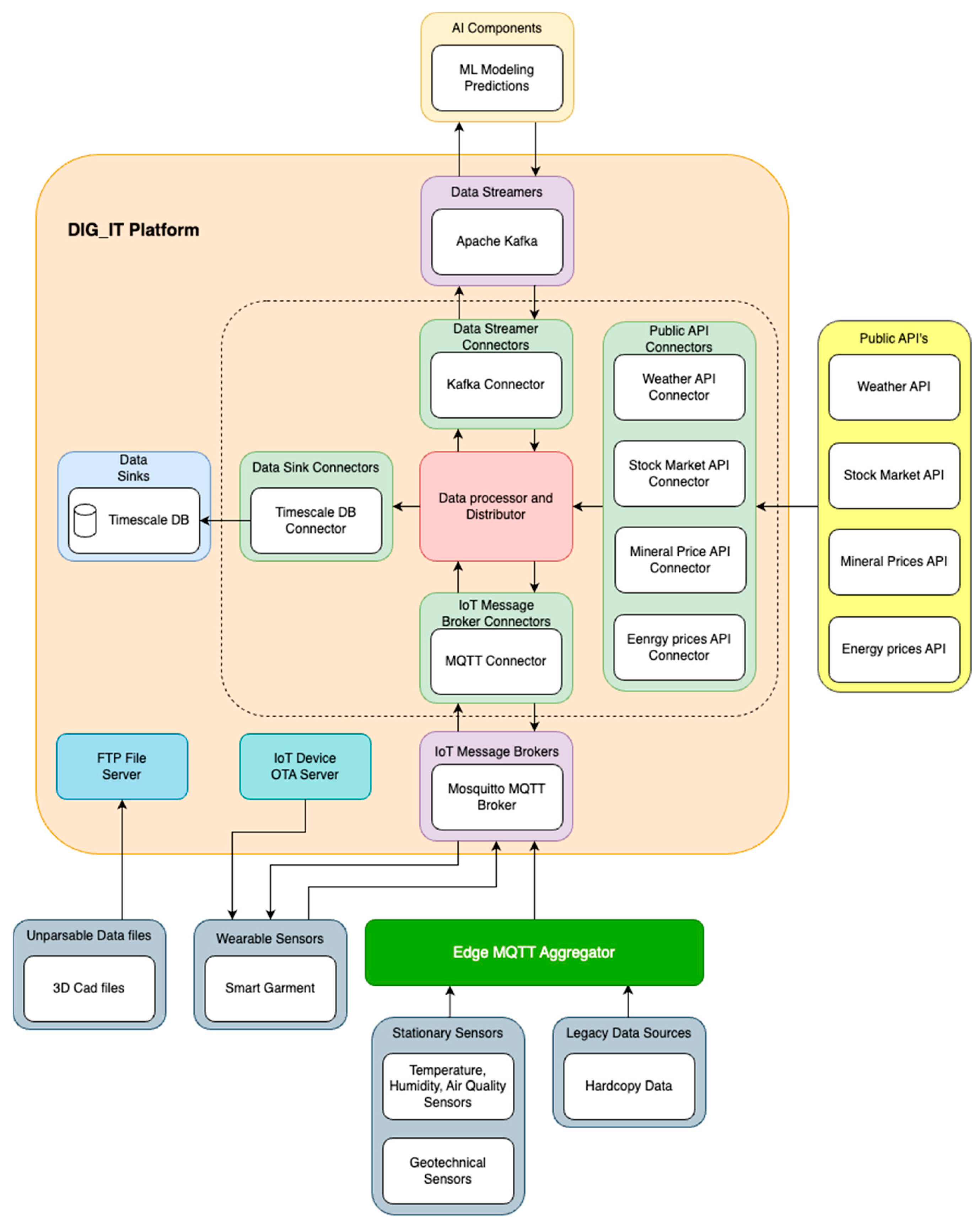

The DIG_IT platform architecture features data collection from devices and sensors, the monitoring units, controllers, as well as other data gathering technologies, all across different worksites. Consequently, near real-time data transmission was implemented with publish-subscribe messaging protocol technologies such as MQTT and Kafka. All the software and hardware infrastructure were designed in such a way that it will expedite and ease the work of end users. The whole architectural design is scalable, flexible and it ensures interoperability and easy information flow between the various components and different data concepts (e.g. real time measurements, input or output of models, economical information etc.).

Therefore, the platform stores data from multiple data sources and sends them to multiple data destinations. All of DIG _IT data is stored in a central location and can be accessed from all DIG _IT components and users.

Figure 2 summarises the high-level architecture of the platform, and its basic building blocks. The DIG_IT architecture represent the fundamental example of the IoT project that collect various types of data from the processes in the mines which is why is used as an example in this study, As shown, Platform consists of the following components: (1) Data processor and Distributor; (2) MQTT broker (integrated with SCHNEIDER systems gathering sensors); (3) Apache Kafka (integrated with ML modelling and UI); (4) Timescale DB; (5) Various Data connectors (Data Streamers, Data Sink, IoT message broker connectors, public API connectors: to be implemented for external data sources), OTA Server for garment updates; (6) FTP Server.

The central software component of the platform is the

Data processor and Distributor block which performs data processing, harmonisation and exporting to various destinations. As shown in

Figure 2, a lot of data comes to the platform from various sources. There is data (mainly sensor’s) coming from the Aggregator, other that comes from the smart garment, ML (machine learning) modelling input/output and other from external sources via APIs. The figure summarises the different data sources from where the data in the project is collected.

Various Data Connectors are implemented so that data is successfully read and written by the Data Processor and Aggregator and the various data sources, data destinations. Data transformation and routing are decoupled from the connector to be able to make platform scale easily in the future and support a vast variety of extra data sources and data sinks. Currently Timescale DB, MQTT and Kafka connectors are used depending on the source from where the data come from. Thus, the data concentrated in the smart garment sent to the platform via MQTT connector. The exact approach is used for the data collected from the Aggregator but by using a different topic. Other data come from APIs and other by parsing files. In addition, different connectors are used for exporting the data to various destinations. Some data are available by directly querying the timescale database while others are published in a Kafka broker to be available for consumption.

The main data sources are Sensors’ data, Machine learning models’ data and data from external sources. Regarding the sensor’s data, there are a lot of several types of sensors and various project partners engaged in data producing and sharing. For example, stationary data contains data from sensors measuring temperature, humidity, PM25, PM10, concentration of CO, NO2, NH3, water level, suspended metals, etc. On the other hand, personal data gathered by using the smart garment and contain measurement obtained by wristband such as scalar and angular acceleration in three axes, the percentage of oxygen saturation in blood, the skin temperature, the heart rate in ppm, the electrodermal activity, the raw PPG and the keywords from the earplug. Simultaneously, it gathers environmental (concentration of CO, NO2 and NH3), noise (noise level in dB) and UWB data such as quality factor and location x, y, z coordinates.

Other sensors’ data includes geotechnical data such as data coming from piezometers and inclinometers are forwarded to the Aggregator.

Having in mind the complexity and the number of different hardware used and available data sources, inability to change the OEM firmware for some of the devices to deploy DID directly on the device - there are number of potential solutions to write the data in the Distributed Ledger Technology:

Writing data directly from the device to Blockchain. This approach requires libraries to be deployed on the device and this approach is conformant with the end to end traceability. It also requires creation of Identity for the device (

Figure 3, step 1), that will write the data in the encrypted channels and in the Blockchain (step 2 and 3).

Writing data from Gateway or Edge to a Blockchain. This approach is not fully compliant as explained in

Section 4.2. It requires Gateway running the script (

Figure 3, step 4), which proxies the communication on behalf of the device.

Writing other sources of data collected by the Kafka event broker. This approach is not fully compliant as explained in

Section 4.2. The devices are sending the data to Kafka (

Figure 3, step 5). The adapter that is subscribed to Kafka can be developed to listen to a specific channel and collect the data that will be written in the Blockchain.

Figure 3.

Methods for writing the data in DLT originated from various sources with different hardware and software capabilities.

Figure 3.

Methods for writing the data in DLT originated from various sources with different hardware and software capabilities.

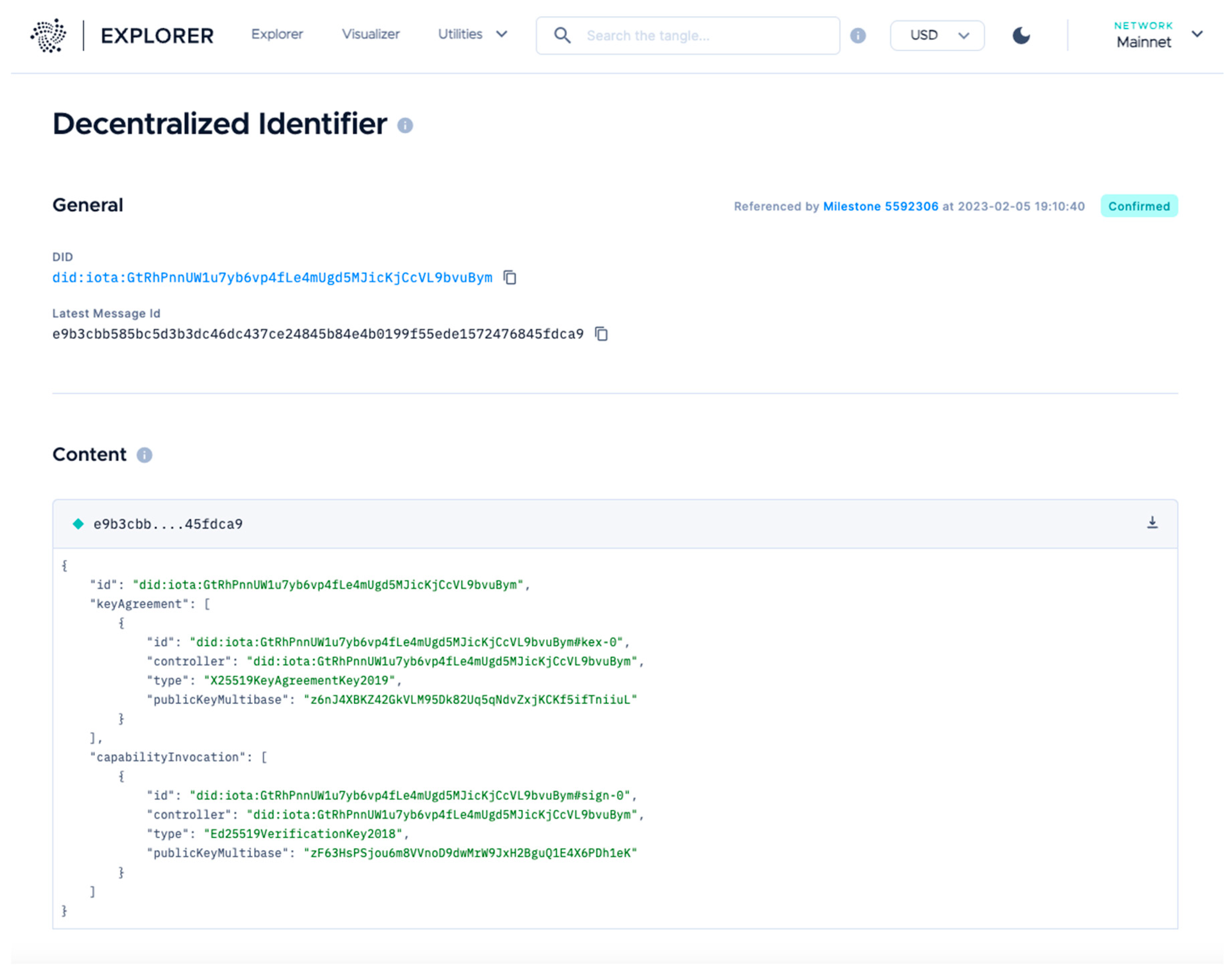

5.3. Device Identity - Data source traceability

IOTA Identity is a Rust implementation of decentralised digital identity, also known as Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI). It implements standards including W3C Decentralised Identifiers (DID) [

34] and Verifiable Credentials [

35] on the IOTA Tangle. It conforms to the DID specifications v1.0 standard [

36] and describes how to publish DID Document Create, Read, Update and Delete (CRUD) operations.

This IOTA Identity library is used to generate a new DID, which results with a basic DID Document created that includes the public key (a public-private key pair), which is coupled with the specific channel use to write the data in the IOTA Streams and control access to the DID document.

Using the following approach the DID Document is formatted as an Integration DID message, signed using the same keypair used to generate the tag, and published to an IOTA Tangle on the index generated out of the public key used in the DID creation process.

Figure 4.

DID document on the IOTA Tangle Explorer.

Figure 4.

DID document on the IOTA Tangle Explorer.

All private keys or seeds used for the

did:iota method should be equally well protected by the users. The signing key is especially important as it controls how keys are added or removed, providing full control over the identity. The IOTA Identity framework utilises the Stronghold project [

37], a secure software implementation isolating digital secrets from exposure to hacks or leaks. Developers may choose to add other ways to manage the private keys in a different manner.

5.4. Encryption for Datasets

IOTA Streams protocol offers a standardised and interoperable structure within the Tangle, ensuring data integrity and immutability. The framework allows any device, acting as a Publisher, to transmit messages into a designated Stream. This data can be made accessible to all or restricted through public key encryption for private interactions. Subscribers, representing other devices, can then retrieve information from the Tangle by subscribing to a Stream.

Figure 5.

Encrypted dataset on the Tangle Explorer.

Figure 5.

Encrypted dataset on the Tangle Explorer.

The dataset can be also made unencrypted, making it fully readable for anyone who accesses the link on the Tangle Explorer. There are two types of encryption used, one for the data written in the Tangle and the second one for storing the data off-chain in the Streams.

5.5. Nodes: Permanent DLT storage

Nodes in the system maintain historical data, including transactions, but periodically perform a 'snapshot' process where older transactions are removed, retaining only unspent transaction output (UTXOs) [

38] in the ledger. These transaction pruning settings are specific to each node, resulting in variations in the length of historical data stored across the network. Consequently, not all nodes will have the same historical DID messages. This poses a challenge for client-side validation, as the complete history of a DID Document is essential. To address this issue, IOTA protocol has released new version of the L1 network (Stardust), which writes the DID documents directly in the Ledger. Nevertheless, it is recommended to deploy an own node that will ensure faster access and data writing in the Ledger.

5.6. Data Management Plan for Distributed Ledger Technologies

All processes that involve data processing and storage with a Blockchain pose a certain level of risk, if the undergoing procedures are not followed up with the adequate GDPR assessment. The Blockchain is not usually used for saving the data - it is not meant to be used as a data storage, but depending on the actual Blockchain implementation it is used for storing hashed messages, which represents part of data transaction as a proof of immutability. The project will store data both locally and on the ledger. The local storage ensures a fast retrieval of the information, while the copy on the Ledger ensures its immutability. To be able to adequately assess the compliance with the GDPR in respect to blockchain use, the project will follow strict guidelines:

It is mandatory to remove any personal information before sending the data to a blockchain.

The data stored locally are encrypted through asymmetric encryption.

For personal data, only the owner of the data will have the access to the data, upon authentication and authorization.

DIG_IT will use permanodes for long-term data storage by implementing filters to store only specific information. The data in permanodes will be encrypted and accessed only by the data owner. The data written in the ledger will remain and could be accessed over the Tangle Explorer, and the reason for having the permanodes is to ensure smooth writing of the big chunks of the datasets in the Ledger. The deployment of the setup in this study is done with the IOTA Mainnet permissionless network. IOTA nodes can be run also by parties other than those part of the DIG_IT environment and permanodes can be hosted by anyone.

However, data related to different data sources in DIG_IT will be accessible only within specific encrypted channels, due to personal data involved, which are known and accessible only by entities who have been verified as party to the DIG_IT environment and rightful entity for data processing. The dataset that are meant to be available to community and public are the dataset from the Hannukainen mine, and they will not include any sensitive data. These datasets are going to remain accessible over the permissionless network unencrypted, and readable without any specific tools, but only using the link to the Tangle Explorer.

In case something needs to be deleted from the Blockchain, this is possible only in a permissioned network, because pruning happens in specific permanodes. Finally, as pruning of data from each of the permanodes is only possible within a permissioned network, its implementation would be better suited to enable the exercise of the data subject's right to deletion of data.

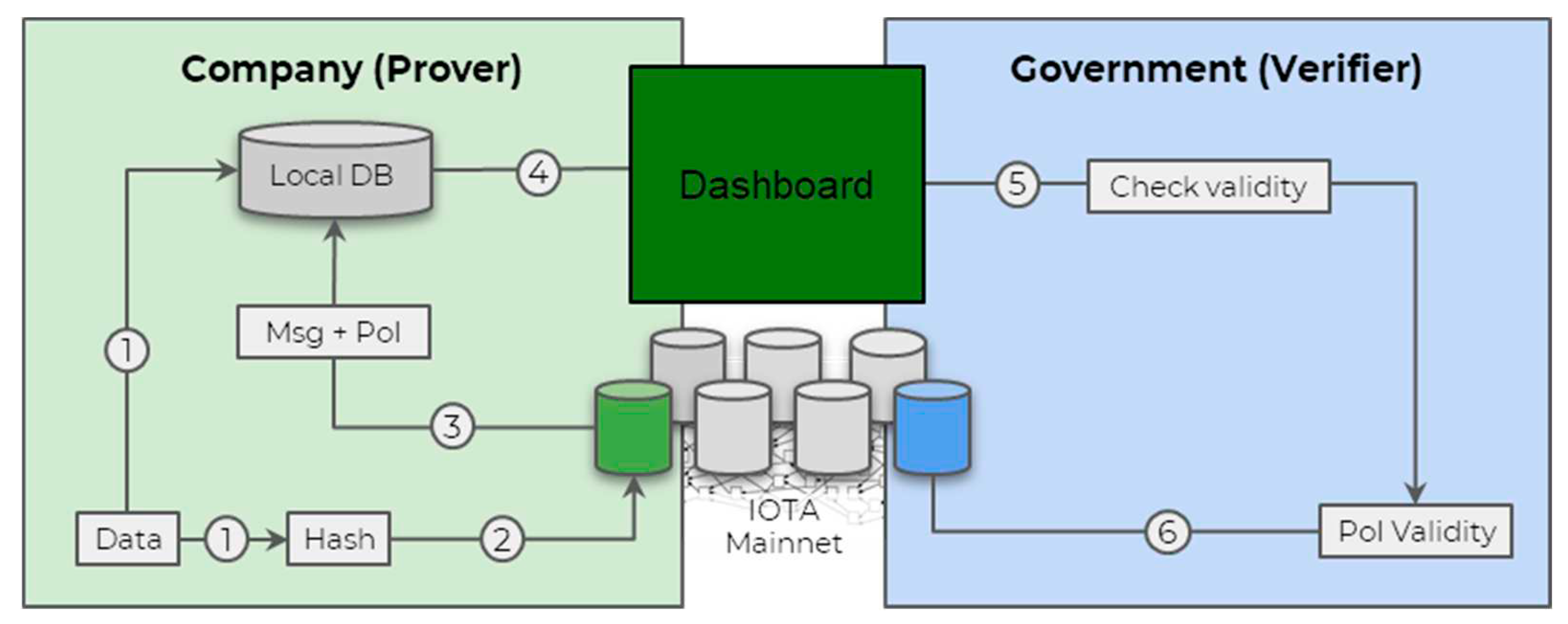

5.7. Labelling Sustainable Material Certification in Mining

In the mining industry, ensuring the integrity and authenticity of reported data, particularly pertaining to emissions and environmental parameters, is of utmost importance for regulatory compliance and transparency. Regulatory bodies, are verifiers, require mining companies, the provers, to maintain an immutable record of their daily emissions, suspended metals, water levels, pH, and related parameters (

Figure 7, steps 1,2,3). This record must be securely stored within the company's infrastructure while also being readily accessible for government scrutiny as well as to local communities over the public (permissionless) Ledger. A key requirement is to demonstrate that the data has not been tampered with since its initial reporting.

The transparency and public accountability of the mining industry can be further enhanced by making the data accessible through a public dashboard (

Figure 7). This ensures that stakeholders, including the general public, can monitor and scrutinise the environmental impact of mining operations. Additionally, the verifier, representing the government agency, can seamlessly access the unique message ID provided by the prover. This message ID serves as a direct link to the Tangle Explorer, a tool that facilitates the verification process by offering an immutable and transparent trail of data provenance.

To better illustrate this concept, let’s consider the following scenario. Government (Verifier) demands companies (Prover) to log their daily emissions (suspended metals, metals, water level, pH, etc) in an immutable way. The data can remain with the company, but they need to be able to show it to the government at any point in time and prove it has not been tampered with, since its reporting day. The data is displayed or accessible using user friendly way such as dashboard, and the Verifier should be able to access the message ID from the Prover that leads straight to the Ledger (Tangle Explorer). Otherwise, the Prover could attach multiple results in the same day and pick the “best fitting” one when being audited.

Figure 6.

Diagram of labelling certification for sustainable mining.

Figure 6.

Diagram of labelling certification for sustainable mining.

The quality and performance data of the enterprises should be considered private and will only be available after granting permission. This being said, where possible and where there are no particular ethical concerns (biometric and personal data from workers, for instance), monitoring data generated and collected during the auditing should be freely distributed.

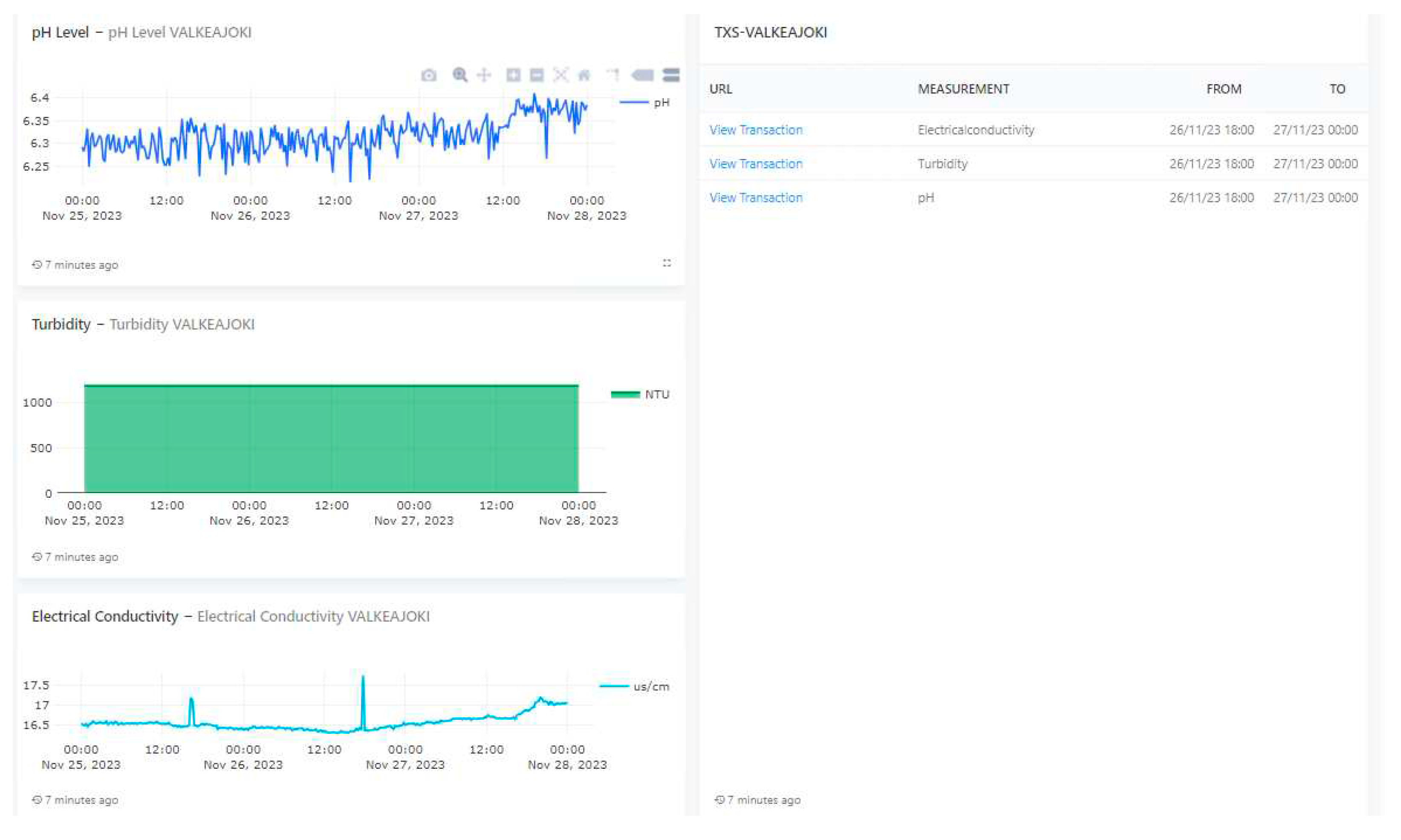

To reproduce the scenario in which Verifier is assessing the traceability of a specific dataset, in

Figure 8 the example of a Dashboard is visually presented, where all values are displayed - in this case water turbidity and water pH level. Verifier can, by clicking the URL that leads to a specific dataset written in the Ledger, access the given data and check on the Blockchain Explorer (

Figure 9) that the dataset values have not been changed. The indexation of the payload with the human-readable dataset presented over the Tangle Explorer are unencrypted so as to be available to the relevant actors, and the message tree provides visual representation of the data stored in the Tangle tree with a specific node (

Figure 9). The message shows that the message has been indexed by the node and that data is included in the ledger.

Unlike IOTA, other DLT can write only the hashed data instead of the data itself. In this case, the hash can be presented over the Dashboard using the very same approach, and the Verifier would need to go to the Explorer and compare the two hashes, linked to a specific value. If the values or hashes do not match, the dataset has been tempered and values changed. Making the immutable data accessible through a public dashboard enhances transparency and accountability. Government verification agencies can easily access and verify data authenticity using a unique message ID linked to the Tangle Explorer. This system ensures data integrity and prevents tampering.

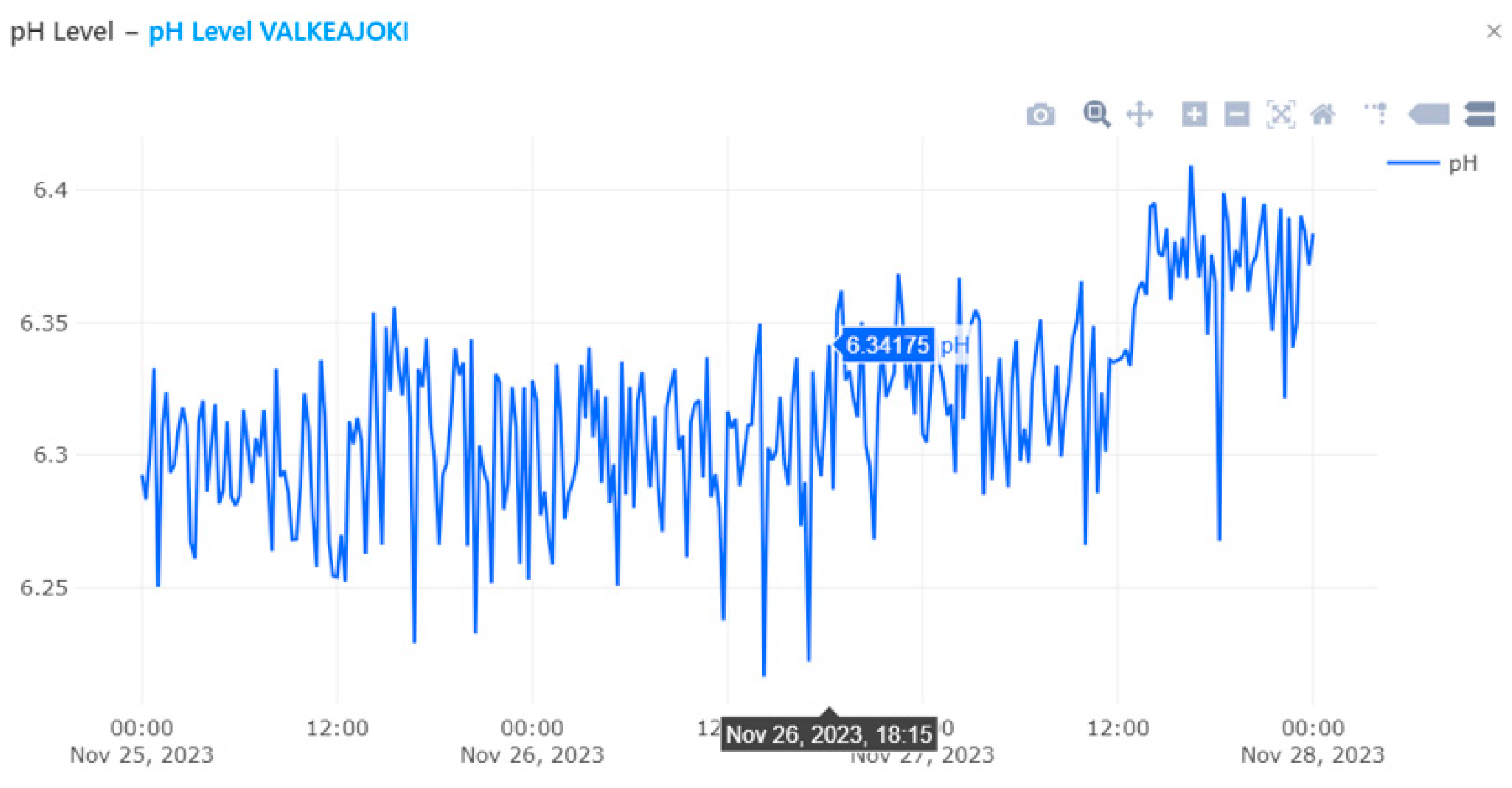

The image below represents the dashboard for environmental or water quality data in the location of Valkeajoki. The interface includes graphs and data on three different parameters: pH level, turbidity, and electrical conductivity, along with some transaction information. Here's a breakdown of each section:

pH Level: This graph displays the pH levels over a period of several days. The pH scale, which measures how acidic or basic water is, ranges from 0 to 14, with 7 being neutral.

Turbidity: The second graph shows the turbidity levels which measure the clarity of the water by assessing how much particles suspended in the water scatter light.

Electrical Conductivity: The third graph shows the electrical conductivity which indicates the water's ability to conduct electricity.

On the right side of the image, there is a table that contains links to data may be recorded on IOTA ledger (Tangle Explorer). Each "View Transaction" link is associated with a specific measurement (Electrical Conductivity, Turbidity, pH) and provides a timeframe thats corresponds to the date and time of the recorded data.

Figure 7.

Compliance Dashboard with pH, Turbidity and Electrical Conductivity and linked to Tangle Explorer.

Figure 7.

Compliance Dashboard with pH, Turbidity and Electrical Conductivity and linked to Tangle Explorer.

Figure 8 highlights one point with a ph Value of 6.34175 at the specific time of November 26, 2023, at 18:15 indicating a pH value of 6.34175. As it has been stated before, this timestamped data is store in IOTA network and can be visualized (

Figure 9) when clicking in “View Transaction” for pH measure.

Figure 8.

Closer look to ph Level Graph.

Figure 8.

Closer look to ph Level Graph.

By recording key environmental metrics such as pH level, turbidity, electrical conductivity, and emissions on an immutable ledger, mining companies can provide verifiable proof of their compliance with regulatory standards. This method effectively addresses the challenges of transparency and accountability in the industry. The immutable nature of blockchain ensures that the recorded data cannot be altered, offering a permanent and trustworthy record of the mining company's environmental impact. This is crucial in demonstrating adherence to environmental regulations and in mitigating the negative consequences of mining operations.

Furthermore, the use of blockchain allows for real-time data sharing with politicians, industrial stakeholders, and local citizens. This transparency ensures that all parties are informed of the mining activities and their environmental impact, fostering trust and collaboration between the mining industry and the affected communities.

6. Discussion and future work

This paper presents a secure, tamper-proof, and user-controlled identity verification and access mechanisms, an approach that lays a sound foundation for a more secure and transparent mining ecosystem. By assigning unique and cryptographically secure identities to each participating device, regardless of their resource constraints or software variations, a unified authentication framework is established. Coupled with PKIs, this setup offers a robust encryption mechanism that ensures secure data transmission between sources and the Blockchain ledger. The original data before hashing is encrypted, offering additional layer of security and minimises the possibility someone unauthorised changing the data. This comprehensive approach underscores that achieving end-to-end traceability extends beyond Blockchain itself, encompassing the intricate interplay of decentralised identities and encryption to ensure confidence in data processing and management within the mining industry’s landscape.

One of the popular methods of low cost IoT monitoring, is using off the shelf sensors, which are then calibrated facilitating offset and other methods on the Edge or in the Cloud. This approach, even affordable and able to cover a lot of points of interest, is prone to errors and is not advisable as these measurements are not legally binding (sensors are not accurate and certified, and the data is changed on the cloud, but the accuracy cannot be guaranteed). The main issue is the number of points where the data should be traced, and complexity to implement such traceability. The use of industry grade certified sensors is one of the key requirements of traceability, and eventually this should be imposed in future for monitoring of the mining industry. This could limit the potential use of certain devices – the fact that devices should be able to run additional libraries to be able to authorise and write data directly in the Ledger. For closed source, and proprietary monitoring hardware and software, these requirements should impact the roadmap, and force OEMs to add as a milestone on their future roadmap to support devices with the embedded DLT libraries. Such an example is STM32 family of 32-bit microcontrollers that embeds the support for Distributed Ledger Technology.

In this study, DIDs and IOTA Streams have been used to implement encryption data records with the hashes anchored on the Tangle. There are other variations, some of them compatible with IOTA technology, such as the L2Sec cryptographic protocol [

35] proposed for IoT constraint devices based on microcontrollers. L2Sec provides all the capabilities for a constraint IoT device to structure a stream of data over the Tangle and enable secure data exchange. L2Sec is enhanced with a Hardware Secure Element to build an HW root-of-trust at the IoT device and further improve the security of the overall solution with a secure-by-design approach. This approach can further enhance the security, and especially mitigate the issue with potential device cloning as it will be impossible to replicate HW function on the device.

The newer version of the IOTA network - Stardust [

36] has compatible version of IOTA Identity which stores the DID documents directly in an unspent output and therefore in the persistent UTXO ledger, which is stored with consensus on every network node. This means that there is more security and less implementation complexity as the DID are written directly on the Ledger.

There is one technological downside of the current implementation of IOTA Streams due to the fact it uses symmetric encryption, which means that an admin with the root access and the key can decrypt the data. Nevertheless, even if he/she changes the dataset in encrypted channel, he/ she could never change the value in the Leger. This can be resolved by replacing the symmetric encryption with another asymmetric cryptographic algorithm.

This paper did not cover use of Smart Contract for automatization of emission compliance. This is proposed in a number of studies and represents the logical next step and future work, which can be easily integrated once the approach as the one proposed in this paper is established. Integration with existing mining systems and processes also requires careful consideration to ensure a seamless transition and effective data interoperability. Moreover, regulatory frameworks and standards for Blockchain implementation in the mining sector are still evolving, necessitating a harmonised approach to legal and governance aspects.

The proposed approach is not only viable in the mining industry. It can be applied to any supply chain project. Further to this, the proposed methodology goes well with the EU conflict minerals regulation (2021) [

37] that came into effect as a union-wide attempt to regulate supply chains and increase transparency between conflict minerals actors. EU importers of tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold will have to carry out checks on their supply chain by following a five-step framework:

Establish strong company management systems;

Identify and assess risk in the supply chain;

Design and implement a strategy to respond to identified risks;

Carry out an independent third-party audit of supply chain due diligence;

Report annually on supply chain due diligence

The proposed methodology could help in establishing the five-step framework and address at least (1) identification of the risks in the supply chain, (4) carrying out third-party audits, and reporting on the due diligence (5).

7. Conclusions

It becomes evident that only advanced technologies hold the potential to comprehensively ensure compliance of the industry 4.0 operation with the sustainable development goals. Blockchain, with its inherent tamper-resistant properties, serves as an ideal platform for storing and certifying these critical records. This ensures that any attempt to modify or manipulate the data is immediately detectable, maintaining the data's credibility and integrity. These innovative safeguards not only provide a shield against unauthorised access and tampering but also establish an immutable record of data transactions. There are different ways to collect the data that influence the ability to ensure the integrity and trustworthy data collection from mining operations. Nevertheless, there are a number of technical challenges for achieving such an approach in practice to be able to make these data legally binding and enforce regulative activities.

To address these challenges, an analysis of the point of failures was conducted, leading to the proposal of a framework involving blockchain technology paired with decentralised identities, on-device firmware, and ethical requirements for data collection. Furthermore, the utilisation of encryption introduces an additional layer of data immutability and sequential ordering. Messages written to an encrypted data channel establish an immutable chain, sequentially numbered for every message. This sequential ordering addresses the concern of attaching multiple results on the same reporting day, as each entry remains bound by its position in the sequence.

End-to-end encryption safeguards data throughout its entire journey, from source to destination, ensuring that only authorised parties can access and interpret the information. Simultaneously, Blockchain's distributed and decentralised ledger system offers an incorruptible chain of custody for each data point, assuring its accuracy and authenticity. By recording waste disposal, emissions, and reclamation efforts on an immutable ledger, mining companies can provide verifiable proof of compliance with regulatory standards and mitigate the negative consequences of their operations. In conclusion, the fusion of sustainable mining practices with Blockchain technology offers a transformative path towards a more ecologically responsible and socially accountable mining industry. By providing transparent, traceable, and automated solutions, Blockchain has the potential to reshape the way mining operations are conducted, monitored, and regulated.