1. Introduction

Arboviruses spread by mosquitos are of major relevance in world health because of their expanding ranges and effects, yet there are frequently no effective vaccines or dependable prophylactics available. Dengue virus (DENV), endemic in over 141 countries, affects 390 million people and claims 36,000 lives annually (Ochani et al., 2023). Discovered in 1952, chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is now found in over 60 countries worldwide, facilitated by global travel and trade (Bartholomeeusen et al., 2023). Since 2016, yellow fever (YF) epidemics have been seen as alerts for potential larger outbreaks, with a risk of spreading to countries like India and China (Wigg de Araújo Lagos et al., 2023). Understanding arbovirus transmission necessitates recognizing complicated interactions between the virus, the mosquito host, and other microorganisms. One such microbe Wolbachia has been extensively studied in the past decade due to its critical relevance in the field of public health. The presence of the endosymbiotic bacterium, Wolbachia, has been shown to inhibit microbial and parasite infections, including viruses in insects (Rainey et al., 2014; Sinkins, 2013). Wolbachia provides flexible methods for disease suppression, such as decreasing vector populations through incompatible males, strains with fitness effects, and interfering with disease transmission (Moreira et al., 2009; O'Connor et al., 2012; Rašić et al., 2014; Teixeira et al., 2008). Naturally, Wolbachia inhabits around 65% of all insect species (Werren et al., 2008) and in arthropods, this bacterium exhibits both mutualistic and parasitic characteristics (Reyes et al., 2021). Wolbachia influences host reproduction through various mechanisms, including male killing (Riparbelli et al., 2012), feminization (Rousset et al., 1992), parthenogenesis (Weeks & Breeuwer, 2001), and primarily, cytoplasmic incompatibility (Beckmann et al., 2017). However, this bacterium is also known to offer considerable antiviral protection to mosquitoes. A transinfection with wMel in Ae. albopictus effectively blocked the laboratory transmission capacity for DENV (Blagrove et al., 2013; Blagrove et al., 2012). In addition, the study observed inhibition of YFV in wMel-infected Ae. aegypti (Van Den Hurk et al., 2012). Successful field trials in northern Australia introduced the wMel strain to high frequencies in wild Ae. aegypti populations (Hoffmann et al., 2011). Most interestingly once a disease-blocking Wolbachia strain establishes itself in the target vector population, it can persist without further releases. It makes Wolbachia the best tool to inhibit arboviral transmission.

Investigating mosquito interactions with microorganisms, particularly with Wolbachia, reveals fascinating details about the defence mechanisms of the insects. Mosquitoes, like many insects, possess a robust innate immune system activated through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) upon identifying microbe-associated molecular patterns. In Ae. aegypti, both Toll and immune deficiency (IMD) signalling pathways induce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) through transcription factors REL1 and REL2 (Waterhouse et al., 2007). While it's established that infection of Wolbachia triggers activation of the immune system in transfected mosquito lines (Moreira et al., 2009), and in establishing the symbiotic relationship, the specific role of these immune responses remains unclear. Understanding the mechanisms underlying Wolbachia's inhibition of arboviruses is essential for projecting selection factors that may affect the virus and mosquitoes, ultimately affecting the inhibition phenotype. Gaining this understanding is essential to maximising the strategy's durability and efficacy. This review article will go over how Wolbachia interferes with the way mosquito hosts, Ae. aegypti, interact with DENV, inhibits the entry and replication of viruses, reduces the amount of nutrients required for an arboviral infection, boosts immunity, produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), promotes cellular regeneration for a better midgut barrier, and controls genes involved in a range of cellular functions.

2. Wolbachia-Aedes-Dengue association

Introducing Wolbachia, into Ae. aegypti mosquito eggs lead to a fascinating outcome. Upon hatching, these mosquitoes become incapable of harbouring the dengue virus, which causes the dengue fever. Some scientists suggest that Wolbachia may outcompete the virus for resources like lipids, enhance the mosquito's immune system (FRA, 2021) and possibly this bacterium can lessen Ae. aegypti's susceptibility to DENV (Edenborough et al., 2021). The exact mechanism behind Wolbachia-mediated blocking remains a mystery, primarily due to challenges in isolating the contributions of the three partners in the Wolbachia-Aedes-dengue association. The understanding of this process relies on observations of how these partners interact for a clear comprehension of the specific mechanisms involved (Johnson, 2015).

3. Defence systems of Ae. aegypti as a host

Pathogen-blocking mechanisms vary among host species, and a cellular process involved in pathogen blocking may not be generally applicable. It is commonly known that invertebrates, including

Ae. aegypti, do not possess adaptive immunity. Mosquitoes employ defence mechanisms both within and outside their bodies to prevent pathogens and mainly rely on their innate immune system (Kumar et al., 2018). It is now recognized that innate immunity in mosquitoes provides prompt defence against infections via humoral or cellular responses, which are typically brought on by the invasive microorganism. The cellular part involves special cells called hemocytes, while the humoral part includes various substances like PRR and AMPs However, gene network analysis across insect species highlights strong connections between the pathways controlling the production of nutrients in the insect and the ability of viruses to replicate (Lindsey et al., 2021).

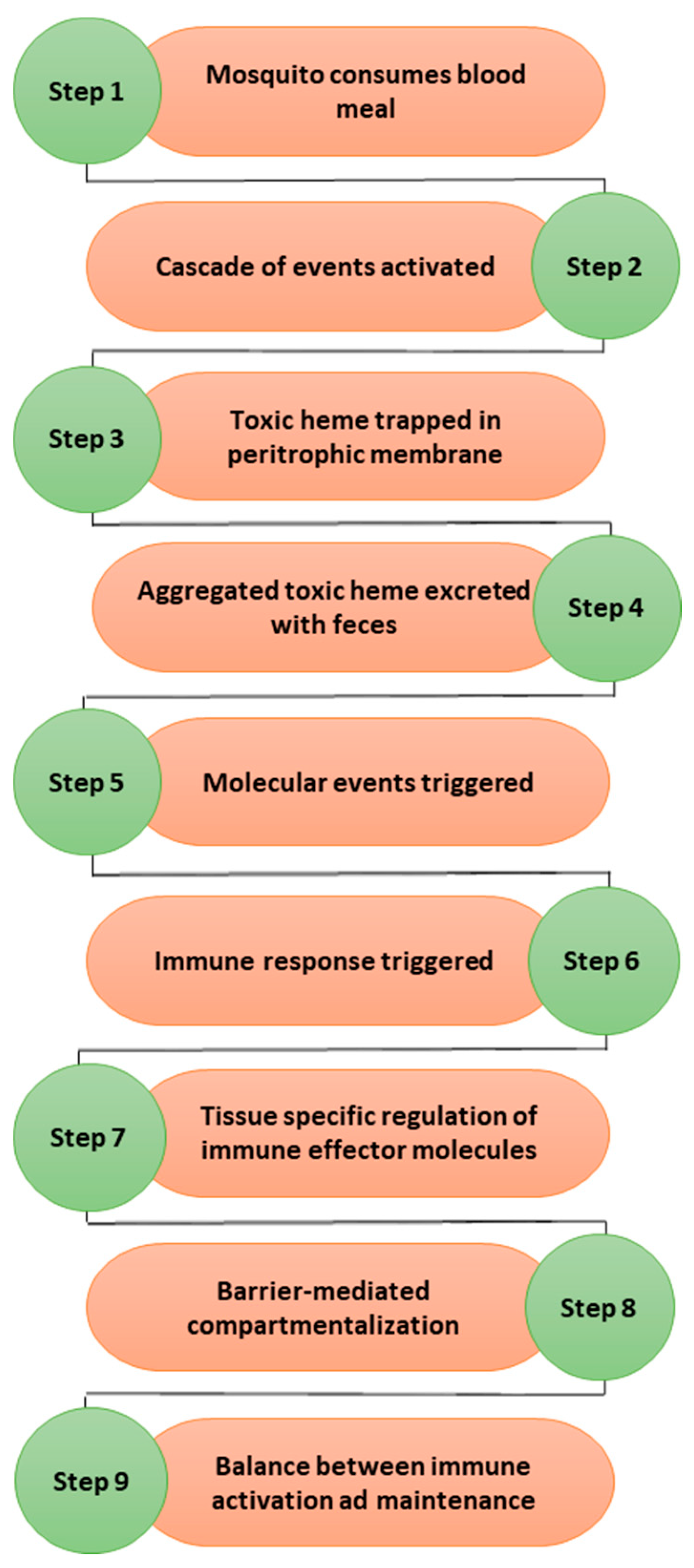

Figure 1.

Defense systems of mosquitoes against infections.

Figure 1.

Defense systems of mosquitoes against infections.

The genetic makeup of

Ae. aegypti is what gives it the natural potential to spread diseases. The genes and markers in

Ae. aegypti's genetic code called the

AaegL5 genome, is crucial for determining how the mosquito interacts with viruses and how prone it is to getting infected. Within this genome, there is a diverse set of gene families, such as chemosensory receptors (related to the mosquito's ability to sense chemicals), glutathione S-transferase (involved in detoxification processes), and C-type lectin (associated with immune responses) (Matthews et al., 2017). The presence of DENV, ZIKV, and CHIKV induces varying transcriptomic changes in

Ae. aegypti (Mukherjee et al., 2019). When these viruses infect

Ae. aegypti, they trigger changes in the mosquito's genetic activity in specific areas like cell structure, genetic processes, immune responses, stress reactions, and metabolic activities (Ramirez & Dimopoulos, 2010; Xi, Ramirez, et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2019).

Wolbachia complicates this relationship between

Ae. aegypti and arboviruses by disrupting the same molecular processes that are necessary for the viruses. This interference causes cellular disturbances that harm the pathogen. Introduction of

Wolbachia into

Ae. aegypti, inhibits arboviruses and controls mosquito populations (Lindsey et al., 2021). However different

Wolbachia strains exhibit differing effects in

Ae. aegypti; some, despite their abundance, are unable to effectively inhibit viral multiplication and transmission (Flores et al., 2020).

Table 1.

Inhibition of DENV in transinfected Ae. aegypti.

Table 1.

Inhibition of DENV in transinfected Ae. aegypti.

| Wolbachia Strain |

Cell line |

Source |

|

wAlbB

|

WB1, |

(Xi et al., 2005), (Pan et al., 2018) |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(Lu et al., 2012) |

| C6/36 cells |

(Hugo et al., 2022) |

| WB2 line |

(Liu et al., 2022) |

| Aag2 |

(Loterio et al., 2023) |

|

wRNase HI |

(Hussain et al., 2023) |

|

Ae. albopictus cell line C6/36 |

(Bian et al., 2010), |

|

Ae. aegypti WB1 |

(Axford et al., 2016), |

| W-Aag2 cell line |

(Pan et al., 2018) |

|

Ae. albopictus C6/36 cells |

(Ahmad et al., 2021) |

| |

(Nazni et al., 2019), |

| C6/36 cells |

(Flores et al., 2020) |

|

wAu and wAlbA

|

C6/36 Ae. albopictus cell culture |

(Ant et al., 2018) |

| wMel |

wMel-Aag2 |

(Loterio et al., 2023) |

| RML-12 cell line |

(Hoffmann et al., 2011), |

| MGYP2 PGYP1 |

(Ye et al., 2013) |

| MGYP2.outAe. albopictus cell line C6/36 |

(Frentiu et al., 2014) |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(Axford et al., 2016), |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(S. L. O'Neill et al., 2018), |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(Indriani et al., 2020) |

|

Ae. aegypti WB1 |

(Utarini et al., 2021) |

| RML-12 cell line |

(Ross et al.,2022) |

|

Ae. albopictus C6/36 cells |

(Pacidônio et al., 2017), |

| |

(Ferguson et al., 2015), (Carrington et al., 2018), (Ryan et al., 2019), (Ford et al., 2019), (Pinto et al., 2021),((Ribeiro dos Santos et al., 2022), (Velez et al., 2023), (Hue et al., 2023), (Duong Thi Hue et al., 2023), (Walker et al., 2011) |

|

wMelPop

|

PGYP1 |

McMeniman et al. (2009) |

|

wRNase HI |

(Hussain et al., 2023) |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(Walker et al., 2011), |

| PGYP1 Ae. aegypti

|

(Axford et al., 2016), |

| |

(Ye et al., 2013), (Ferguson et al., 2015) |

|

wMelPop-CLA

|

C6/36.wMelPop-CLA line, |

(Frentiu et al., 2010), |

|

Ae. aegypti Aag2 cell line |

(Walker et al., 2011) |

| PGYP1 line, PGYP1.out |

(Moreira et al., 2009) |

|

wMelPopCS

|

|

(Flores et al., 2020) |

|

wPip

|

wPip-Aag2 |

(Loterio et al., 2023) |

4. Cellular-level defence against viruses and Wolbachia

The internal structure of

Ae. aegypti is required for arboviruses to successfully move through the stages of viral entrance, replication, assembly. and exit (Foo & Chee, 2015). This framework, sometimes referred to as the cytoskeleton, is made up of an actin filament and microtubule network. Arboviruses boost cytoskeletal structures in their host for their life cycle processes, while

Wolbachia does the opposite, downregulating these structures to block the arboviral binding and entry. In DENV-infected

Ae. aegypti, genes such as dynein, vimentin, tubulin, actin, myosin, tropomyosin, and laminin are substantially expressed (Sim & Dimopoulos, 2010). Effective DENV infection in mosquito cells is essentially achieved by the cooperation of several proteins (Guo et al., 2010). Actin and tubulin support DENV infection in vitro, while NS5 associates with myosin in DENV infection (Paingankar et al., 2010). Tubulin is expected to be an important component in the transit and assembly of DENV in mosquitoes.

Wolbachia on the other hand reduces viral loads in mosquitoes by affecting cytoskeletal proteins. The introduction of the

wAlbB strain appears to influence the cellular environment by reducing the levels of specific proteins associated with cell adhesion (dystroglycan) and cytoskeletal structure (beta-tubulin) in

Ae. aegypti cells infected with DENV. This reveals a mechanism by which

Wolbachia interferes with the virus's development (Lu et al., 2020). Silencing host cytoskeleton proteins inhibited DENV binding to cells, providing evidence of

Wolbachia's role in preventing virus entry. This is a significant finding as it demonstrates how

Wolbachia interferes with the early stages of arboviral infection (Lu et al., 2020).

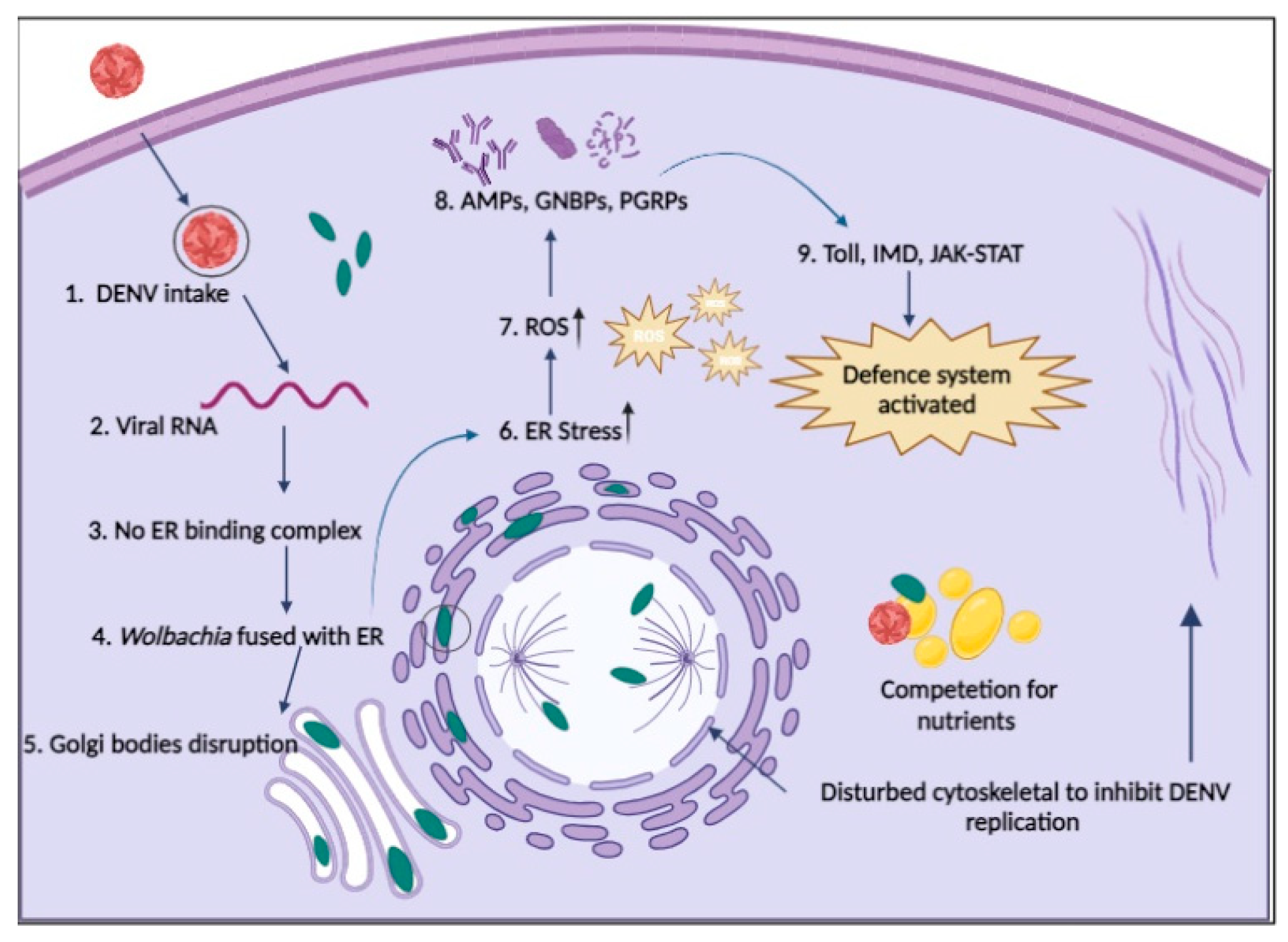

Figure 2.

Possible defence systems of cells in the presence of Wolbachia. 1. DENV enters a Wolbachia-infected cell through endocytosis; 2. Viral RNA starts replication; 3. Replication of DENV is restricted because no binding complex forms on the ER membrane; 4. Wolbachia fused with the ER membrane and disturbs it; 5. No formation of Golgi vesicles due to disturbance of Golgi apparatus membrane by Wolbachia; 6. Wolbachia induces ER stress; 7. Wolbachia produces ROS to increase cellular stress; 8. Upregulation of AMPs, GNBPs and PGRPs to boost immunity; 9. Immune pathways are activated to fight against pathogens (cells take Wolbachia as part of innate immunity); & Wolbachia also competes with DENV for nutrients and also disturbs the cytoskeleton to stop the movement of DENV and maturation.(Figure created using Biorender).

Figure 2.

Possible defence systems of cells in the presence of Wolbachia. 1. DENV enters a Wolbachia-infected cell through endocytosis; 2. Viral RNA starts replication; 3. Replication of DENV is restricted because no binding complex forms on the ER membrane; 4. Wolbachia fused with the ER membrane and disturbs it; 5. No formation of Golgi vesicles due to disturbance of Golgi apparatus membrane by Wolbachia; 6. Wolbachia induces ER stress; 7. Wolbachia produces ROS to increase cellular stress; 8. Upregulation of AMPs, GNBPs and PGRPs to boost immunity; 9. Immune pathways are activated to fight against pathogens (cells take Wolbachia as part of innate immunity); & Wolbachia also competes with DENV for nutrients and also disturbs the cytoskeleton to stop the movement of DENV and maturation.(Figure created using Biorender).

Mosquitoes possess a natural defence mechanism against oxidative stress induced by blood meals. This defence involves activating antioxidants to protect their tissues. In DENV infection, mosquitoes produce ROS like mammalian cells but avoid the harmful effects associated with ROS accumulation (Birben et al., 2012). This unique ability is considered an evolutionary advantage, ensuring the successful transmission of the virus without compromising the mosquito's health. DENV infection in mosquito cells (specifically C6/36 cells), causes endoplasmic reticulum stress by inducing the Unfolded Protein Response, a cellular stress response mechanism. The chaperones GRP78/BiP and GRP94 are used as ER stress sensor genes, and their upregulation is observed against DENV in the cells of mosquitoes (Chen et al., 2017). Alterations in the mitochondrial membrane potential are linked to a noteworthy rise in GST (Glutathione S-Transferase) activity, suggesting the possibility of ER stress induction. Because mosquito cells have more GST activity, there may be less oxidative stress in the environment, which would facilitate viral propagation. Knocking down GST in DENV-infected cells elevates the concentration of Superoxide Dismutase, linking GST activity to oxidative stress regulation during DENV infection in mosquitoes (Chen et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2007). GST also plays a significant role in minimizing cell death triggered by oxidative stress induced by DENV2 in mosquito cells (Balakrishnan et al., 2018). Additionally, eIF5A levels decrease during the ageing of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes and its expression is upregulated in response to actively replicating DENV in the C6/36 cell line. It indicates a potential role for eIF5A in the cellular response to DENV infection (Lin et al., 2007; Shih et al., 2010). Knowing all these cellular defences in Ae. aegypti may help us to understand how Wolbachia control DENV transmission.

5. How Wolbachia control DENV?

There are many possible methods by which the transinfection of various strains of Wolbachia into Ae. aegypti can prevent the spread of disease. This section is all about how DENV affects the genes of Ae. aegypti, how these changes happen together, and how the mosquito responds at the cellular level in the presence and absence of Wolbachia.

5.1. Competition for Intracellular resources

Wolbachia and DENV both want the same things inside the cells of mosquitoes. Wolbachia often triggers a response against pathogens in arthropods by boosting host immunity or competing for host cellular resources (Pan et al., 2018). They compete for resources like cholesterol and iron, necessary for their growth. Transinfecting Wolbachia into Ae. aegypti prevents the DENV from proliferating in the hatched mosquito population. Although the specific mechanism of action is unknown, Wolbachia may be more resource-efficient than the virus. Additionally, it may strengthen the mosquito's immune system. Wolbachia relies on various host factors for replication, transmission, and manipulation of the host. It depends on host-derived membranes (White et al., 2017), altering their morphology, and affecting cholesterol/lipid metabolism (Geoghegan et al., 2017). wMelPop or wMel infected cells of Ae. aegypti exhibit a significant reduction in total cholesterol (Caragata et al., 2014) and this reduction implies that Wolbachia relies on host cellular lipids, indicating a dependence on the host for essential lipids crucial for its survival and function within the mosquito cells. As mentioned earlier, Wolbachia also utilizes the host's cytoskeleton and secretes proteins to manipulate cellular components, such as actin bundling (Ferree et al., 2005). These processes show how the bacterium has clever ways to survive and influence the host's biology.

When a cell is infected the DENV changes the internal membranes of the cell to produce specific locations where the virus can multiply (Perera et al., 2012). By manipulating the cell's fatty acid synthesis pathway, DENV effectively increases the production of lipids to facilitate its replication. Wolbachia also requires unsaturated fatty acids and depends on the host cell to produce these lipids since it lacks the genes necessary to produce them on its own. DENV's replication is also influenced by the production of cholesterol, on the other hand, if Wolbachia is abundant, it may consume so much fatty acid that it interferes with the cell's regular functions and may even affect how viruses replicate.

While Wolbachia is recognized for inhibiting certain viruses, its effectiveness is mainly observed against viruses with positive-sense or double-stranded RNA genomes (Teixeira et al., 2008). Its ability to inhibit negative-sense RNA viruses is less commonly reported. DENV, a positive-strand RNA virus, enters midgut cells following a blood meal (Salazar et al., 2007). Many proteins, including replication factors, are produced when the viral RNA is translated into a polyprotein. Once DENV surpasses the midgut barrier, it can access other tissues like the fat body and the hemocytes. As soon as the virus enters the hemocoel, it can reproduce in the salivary gland cells and travel to the lumen of the glands. From there, the virus can be transmitted to a human host during subsequent mosquito blood-feeding. Interestingly when Wolbachia infected Ae. aegypti were given a substance that stabilizes cholesterol, which allowed the Dengue virus (DENV) to start replicating again (Geoghegan et al., 2017). This suggests that Wolbachia's influence on cholesterol levels plays a role in regulating DENV replication, and stabilizing cholesterol can reverse this effect.

New studies suggest that instead of simply struggling over lipids, there's a more complicated relationship where changes in lipids might work against each other. In one study by Koh et al., when DENV infection alone leads to an abundance of lipids, while Wolbachia strain wMel causes a mild depletion. But when both DENV and wMel infect mosquitoes together, the lipids in the mosquitoes look like the changes caused by DENV alone. This suggests a way the virus might be controlled. Specific lipids, like sphingomyelins and cardiolipins, are highly present in DENV3-infected mosquitoes but depleted when wMel is present, suggesting an indirect antagonistic effect. In another study, the interaction involves elevated acyl-carnitine lipids during DENV and ZIKV infection but a significant reduction in wMel-infected cells (Manokaran et al., 2020). Lowering acyl-carnitine increases wMel density while adding this lipid to wMel-infected cells boosts DENV. A recent study indicates that wMel-transinfected Ae. aegypti suppresses DENV and ZIKV through the downregulation of the insulin receptor (Haqshenas et al., 2019). However, understanding how Wolbachia downregulate the DENV is a matter of interest that is unclear.

5.2. Autophagy

When cells face stress or starvation, autophagy helps get rid of damaged organelles and large protein aggregates. It can be used to degrade invasive bacteria, viruses, and parasites in addition to its function in recycling cell components during development. Autophagy is important for iron scavenging and cellular homeostasis. When Wolbachia is present, it manipulates the cell's autophagy, impacting the replication of arboviruses. This interference limits the nutrients available for the viruses, making it harder for them to grow. DENV has been found to trigger and depend on autophagy for efficient viral replication in mammalian cells (Lee et al., 2008). Particularly, DENV induces a specific type of autophagy that targets lipid droplets, causing alterations in the cell's metabolism. The autophagosomes generated by DENV coincide with lipid droplets and eventually transform into autolysosomes, resulting in free fatty acids. This process showcases how DENV exploits autophagy, specifically targeting lipid droplets, to facilitate its replication and manipulate cellular metabolism.

Activating autophagy decreases bacteria whereas suppressing it boosts bacterial populations in many organisms. Wolbachia levels are regulated by autophagy in a range of hosts, indicating the bacteria's adaptation to resist autophagy and stay inside host cells. Wolbachia secretes a protein that manipulates the autophagy initiation pathway. Activation of the autophagy pathway triggered by Wolbachia infection is controlled by TOR–Atg1 signalling pathway genetic modification (Voronin et al., 2012). Modification of TOR-Atg1 results in increased lysosomal production within the cell. Wolbachia-containing vacuoles can be bound by these lysosomes and eliminated. However, using a substance called 3-MA, autophagy could be inhibited which causes an increase in the quantity of Wolbachia in both animals and cells. Wolbachia most likely evolved anti-autophagy mechanisms to live and proliferate inside host cells. Furthermore, the APG5 is the most important gene of the autophagy. A recent finding revealed that there was no significant effect of Wolbachia infection on APG5 expression. Even though the load of DENV are high with the suppression of APG5, the Wolbachia presence does not alter the level of APG5. We concluded that autophagy is not necessary for Wolbachia-based protection against infections. This indicates that in the presence of a Wolbachia infection autophagy is acting independently, but is probably a crucial factor in the Ae. aegypti against DENV infection.

5.3. Immune priming

To prevent arboviral transmission, Wolbachia employs two strategies. For starters, it competes for limited host cellular resources with arboviruses. Second, when transmitted to non-native hosts, it uses immune priming, which is a preactivation of the host's immune system. This strengthens the arthropod's resistance to arboviral infections. Signalling pathways such as IMD, Toll, and JAK-STAT initiate immune priming (Kamtchum-Tatuene et al., 2017). Rancès et al. (2012) found that Wolbachia activates immunological genes linked to Toll pathways, melanization, and antimicrobial peptides. The JAK-STAT pathway, known for regulating antiviral immunity, has been proven effective in preventing DENV infection in Ae. aegypti (Jupatanakul et al., 2017). Wolbachia activates immunological genes and pathways in Ae. aegypti mosquitos, offering protection against DENV. This immune-priming effect was observed in mosquito larvae exposed to dormant dengue virus, resulting in protection against the virus in maturity (Vargas et al., 2020).

5.3.1. Wolbachia and Toll pathway

Vector-virus interactions have been studied since the initial

Ae. aegypti genome sequence was made public (Nene et al., 2007).

Ae. aegypti’s defence against DENV infection is mediated by this pathway, as demonstrated by early transcriptome analysis in conjunction with functional assessments (Weaver & Vasilakis, 2009). Immune genes of the Toll pathway are upregulated in response to DENV-2 infection, indicating their essential role in controlling mosquito defence against DENV (Xi, Ramirez, et al., 2008).

Wolbachia activation of the Toll pathway induces host release of ROS, leading to the synthesis of AMPs and antioxidants as shown in (Pan et al., 2012). This pathway is responsible for

Ae. aegypti’s antiviral defence in the midgut during DENV infection. The silencing of Myeloid Differentiation factor 88 (MYD88) is responsible for the high level of DENV in the tissues of the midgut. In both the carcass and midgut tissue of

Ae. aegypti infected with DENV, the AMP transcripts are highly marked (Angleró-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Furthermore, AMP gene expression is enhanced by the silencing of Cactus and Caspar (Xi et al., 2008). Viruses can modulate host arboviral susceptibility by downregulating AMP genes, as demonstrated in in-vitro and transcriptomic research on DENV-, ZIKV-, and CHIKV-infected mosquitoes (Carvalho-Leandro et al., 2012). After infection, there's a temporary increase in the expression of Spätzle (spz) and Rel1A, along with a transient rise in Cactus expression, which later decreases after 7 days (Souza-Neto et al., 2019). This upregulation indicates a robust immune response, with the pathway recognizing and combating the presence of the DENV in

Ae. aegypti. When

Ae. aegypti becomes infected with dengue, the Gram-negative binding proteins (GNBPs) may engage with virus particles or cellular debris, which could trigger immunological responses or directly neutralize virus particles, strengthening the mosquito's defences against DENV. Susceptibility has also been directly linked to several immune-related genes.

Caicedo et al., demonstrated that certain genes in

Ae.

aegypti significantly reduce the proliferation of DENV. These genes included Keratinocyte lectin

(AAEL009842), Gram-negative binding protein–GNBP

(AAEL009176), Cathepsin-b

(AAEL007585) and NPC2

(AAEL015136). This demonstrates the significance of these genes and their role in the functioning of DENV infection. In mosquitoes, the midgut serves as a primary site for the replication of the virus and now it’s clear that the Toll pathway activation by RNAi-mediated depletion of Cactus suppresses viral infection in the mosquito midgut.

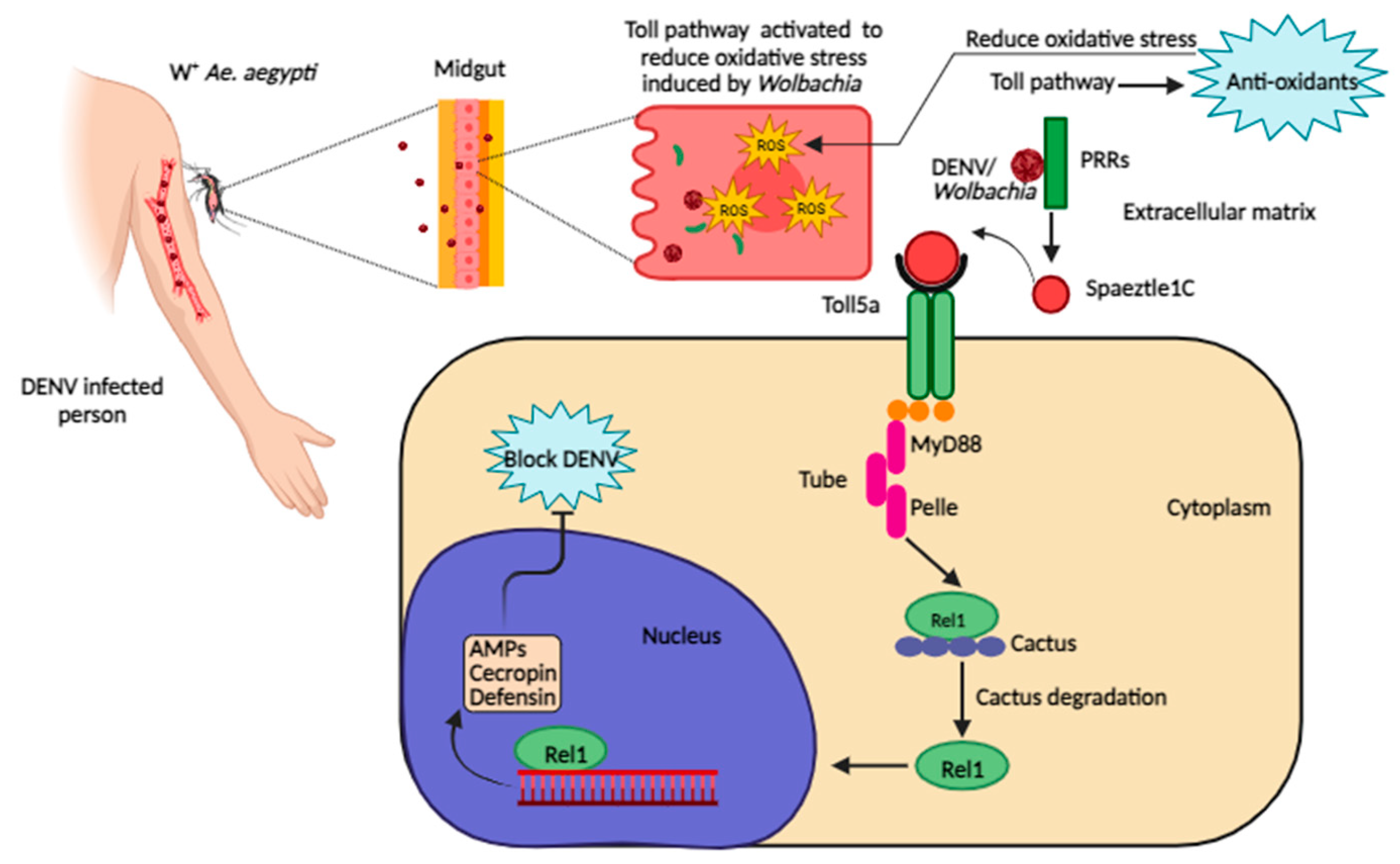

Figure 3.

Dengue virus inhibition by Wolbachia-triggered Toll pathway activation in Ae. aegypti. Wolbachia produces ROS to favour its replication. To produce anti-oxidants to cope with oxidative stress, the Toll pathway is activated. The Toll pathway controls immune responses to Wolbachia and DENV through the systemic production of AMPs. PRRs recognize DENV or Wolbachia-associated molecular patterns and start maturation of spaetzle1C, it binds to Toll5a receptors and initiates the Toll pathway through adaptor proteins MyD88, Tube, and Pelle. The Cactus protein, a negative regulator of Rel1, is degraded by phosphorylation. Rel1 translocate into the nucleus and activates transcription of genes encoding for AMPs, cecropin and defending. These AMPs stop the replication of DENV (the exact mechanism is unknown). Figure created using Biorender.

Figure 3.

Dengue virus inhibition by Wolbachia-triggered Toll pathway activation in Ae. aegypti. Wolbachia produces ROS to favour its replication. To produce anti-oxidants to cope with oxidative stress, the Toll pathway is activated. The Toll pathway controls immune responses to Wolbachia and DENV through the systemic production of AMPs. PRRs recognize DENV or Wolbachia-associated molecular patterns and start maturation of spaetzle1C, it binds to Toll5a receptors and initiates the Toll pathway through adaptor proteins MyD88, Tube, and Pelle. The Cactus protein, a negative regulator of Rel1, is degraded by phosphorylation. Rel1 translocate into the nucleus and activates transcription of genes encoding for AMPs, cecropin and defending. These AMPs stop the replication of DENV (the exact mechanism is unknown). Figure created using Biorender.

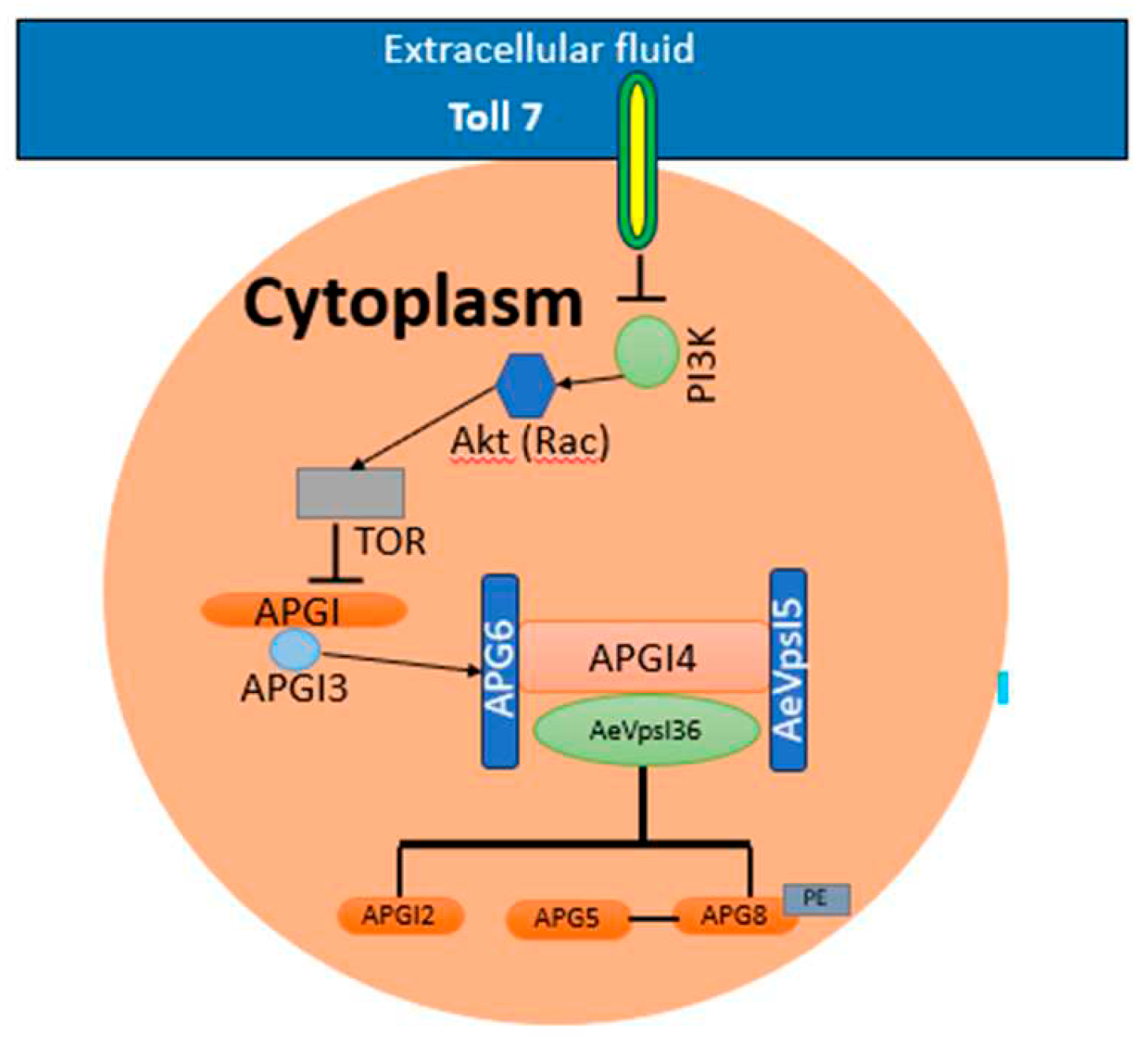

Figure 4.

Activation of autophagy in Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti.

Figure 4.

Activation of autophagy in Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti.

Bonizzoni et al. (2012); (Luplertlop et al., 2011; Sim et al., 2012) found that extracellular PRR attaches to pathogen-derived ligands to initiate the Toll pathway. It triggers a proteolytic cascade that causes the Spätzle processing enzyme (SPE) to convert pro-Spätzle to Spätzle (DeLotto & DeLotto, 1998). Effector gene transcription is started when Spz binds to the transmembrane receptor Toll, triggering a cytoplasmic cascade that results in the nuclear translocation of the NF-kB transcription factor Rel1a. This pathway is noticeably downregulated in response to DENV infection specifically, certain variants of DENV-2, found in the 3' untranslated region 3'UTR, inhibit the Toll pathway within mosquito salivary glands by producing subgenomic flaviviral RNA (Pompon et al., 2017). However, there's evidence suggesting that Wolbachia induces oxidative stress within the mosquito, and this stress, in turn, triggers the Toll pathway (Pan et al., 2012).

In the mosquito's antiviral defence, multiple immune pathways are engaged, with each pathway showing specificity toward particular viruses. DENV virus activates Toll pathway genes, and increased expression of AMPs has been observed in these mosquitoes but their specific function in antiviral defence has yet to be fully understood. Pan et al. (2012) suggested that the Toll pathway is responsible for expressing antioxidants and AMPs such as defensins and cecropins. Defensins were originally assumed to target enveloped viruses by breaking the viral envelope. Their extracellular antiviral impact is indicated by the fact that they are generated in the fat body and released into the hemolymph. Wolbachia infection activates defensins, including DEFA and CECA, to limit DENV proliferation, as demonstrated in DEF/CEC transgenic Ae. aegypti (Kokoza et al., 2010). Hence to fully understand mosquito antiviral defenses and their significance in the fight against infectious illnesses, more research is necessary.

5.3.2. Wolbachia and IMD Pathway

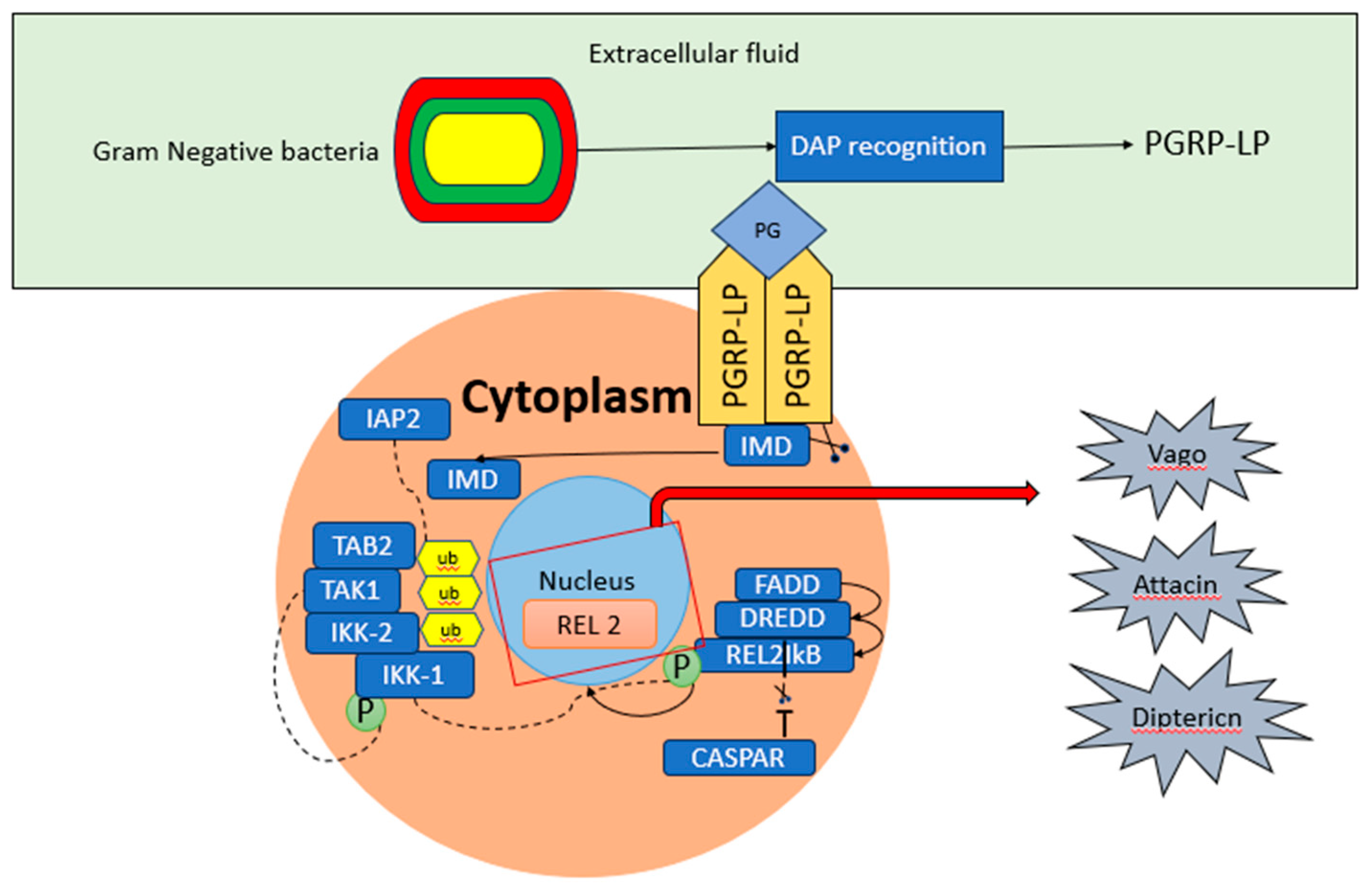

IMD is another innate immune signalling pathway that plays a vital role in multiple responses such as antiplasmodial, antiviral and antibacterial (Barletta et al., 2017; Garver et al., 2012). Peptidoglycan-recognition protein receptors PGPR-LG and PGPR-LC are responsible for the activation of this pathway. There are various proteins including IMD, FADD, DREDD, Tak1 and IKK, that participate in the cascade of the IMD signalling pathways, leading to the formation of transcription factors NF-κB (Relish and REL2). The activated transcription factor REL2 translocates into the nucleus, playing a key role in the activation of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and other immune-related genes (Garver et al., 2009; Gillespie and et al., 1997). Furthermore, in the mosquitoes upregulation of transcription factor REL2 led to the overexpression of many genes such as cecropin A and N and defensin A, C and D (Antonova et al., 2009). Notably, CASPAR negatively regulates the IMD pathway, suppressing the protease DREDD and therefore preventing REL2 nuclear translocation (Basak et al., 2007) resulting in enhanced AMPs. Moreover, in mosquitoes, the formation of REL1 and REL2 is activated by the signaling pathways (Toll and IMD), to promote the AMPs expression (Waterhouse et al., 2007).

During infection with various microorganisms (filamentous fungi, yeast, gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria) insects produce a broad spectrum of AMPs, contributing to both direct killing and innate immune modulation to reduce the entrance of pathogens. Different mosquito species exhibit variations in the production of AMPs, these variations depend upon the regulation of immune signalling pathways as well as dependent upon the pathogen type that produced the response. Furthermore, in Ae. aegypti seveteen AMPs have been identified, belonging to five families: cecropins (α-helical peptides), defensins (cysteine-rich peptides), attacin (glycine-rich peptides) gambicin (cysteine-rich peptides) and diptericin (glycine-rich peptides) each with specific modes of action against different microorganisms. Defensins cause loss of motility by breaking down the membrane permeability barrier, making them extremely poisonous and active against parasites and Gram-positive bacteria. Cecropins are positively charged peptides that attach to negatively charged lipids in membranes to alter the biological structure of those membranes. Other killing modes by cecropins include reducing the synthesis of protein, and nucleic acid and inhibiting enzymatic activity. It has been discovered that after infection of the parasite defensins and cecropins were expressed in the various tissues (midgut, thorax, and abdominal) of An. gambiae.

5.3.3. Role of IMD pathway against the antiviral defence in various hosts

IMD pathway has shown its significant role against antiviral defence in various mosquito-virus interactions. In

An. gambiae, upregulation of the transcription factor REL2 leads to the overexpression of genes such as cecropins A and N and defensin A, C and D, after the injection of the O'nyong-nyong virus (ONNV). However, the IMD pathway’s contribution to antiviral action may be minor, as observed in the context of ONNV in

An.

gambiae. Recently it has been confirmed that LRIM1 and CEC3 are up-regulated in the

An.

gambiae during the IMD. Furthermore, there was no noticeable effect when the IMD pathway and NF-kB-like component REL2 were silenced, indicating that this pathway may have a minor role in the antiviral action (Waldock et al., 2012). Moreover, Avadhanula et al. (2009) have conducted investigations that have revealed the antiviral function of IMD in

D.

melanogaster against the Sindbis and Cricket paralysis viruses. The

Drosophila IMD pathway coordinates defences against viruses and gram-negative bacteria. To investigate the role of the IMD pathway in the infection of DENV, DENV-susceptible strains of

Ae. aegypti by silencing key components of the IMD pathway showed no effect on DENV titer in the midgut (Xi, Ramirez, et al., 2008). Nevertheless, a recent study found that IMD silenced

Ae.

aegypti mosquitoes of a DENV-resistant strain had higher DENV titers. This finding seems to imply that the IMD pathway may play a significant role in the mosquito's antiviral defence against DENV (Sim et al., 2013). Additionally, salivary glands infected with DENV had higher levels of the antimicrobial peptide AAEL000598, which belongs to the

Ae. aegypti cecropin family. This suggests that this pathway may be involved in preventing the replication of DENV in salivary glands Luplertlop et al. (2011). According to a recent study, the Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) associated system of

Ae. aegypti is significantly active during a blood meal. DENV replication can be inhibited by silencing an up-regulated gene that codes for the

Ae. aegypti GABAA receptor component (AaGABAA-R1). This gene is upregulated during DENV-2 infection. Cecropins are increased in mosquitoes carrying the DENV-2 virus in

Ae. aegypti. Cecropins also demonstrate antiviral action against CHIKV. These data revealed that the inhibition of the IMD pathway might be essential for the replication of arbovirus. Numerous studies on the main dengue vector

Ae. aegypti have demonstrated that in the presence of

Wolbachia, the level of ROS, DNA methylation patterns and differential microRNA (miRNA) expression with their antiviral effect against DENV replication become high (Hussain & Asgari, 2014; Ye et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2013). Luplertlop et al. (2011) demonstrated that the DENV infection promotes the expression of cecropin-like peptide AAEL000598 implicated in the innate immune response as well as the activation of the IMD and Toll pathways. Due to the presence of DENV-2 in the salivary glands the Toll and IMD signalling pathways are activated. The salivary glands of

Ae. aegypti also express the AaMCR and AaSR-C, suggesting a potential role in antiviral processes (Xiao et al., 2014). Furthermore, by oral infection with epidemic isolates, the formation of sub-genomic flaviviral RNA (sfRNA) is high in the salivary glands of

Ae. aegypti. Nevertheless, the precise molecular mechanism or mechanisms underlying

Wolbachia-mediated antiviral activity, in general, remain unclear because this research was restricted to the transinfected host species

Ae. aegypti.

Figure 5.

IMD Pathway and its activation.

Figure 5.

IMD Pathway and its activation.

The IMD pathway is accompanied by recruitment of the proteins such as FADD (Fasassociated death domain) and IMD (immunodeficiency) to stimulate the Caspase DREDD (indicated peptidoglycan recognition protein PGRP-LP responsible for the sensing of peptidoglycan (PG). In a phosphorylation-dependent manner, the transcription factor REL2 is activated by the cleavage of DREDD, allowing the translocation of REL2’s into the nucleus and stimulating expression of the gene, while the IκB domain remains in the cytoplasm. After caspases cleave IMD the phosphorylation of REL2 occurs. CASPAR inhibits the cleavage of REL2 cleavage which negatively affects the activation of the IMD pathway.

5.3.4. Transfected Wolbachia and Mosquito Immune Responses

Naturally occurring Wolbachia does not have a major effect on vector competence in mosquito species. For example, Ae. albopictus' wAlbB is unable to produce resistance against DENV (Bian et al., 2010). Bourtzis et al. (2000) demonstrate that the AMP transcripts in Ae. albopictus is not substantially affected by Wolbachia. Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes exhibit resistance to diseases, which is probably the result of an increased host immune response that balances any potential negative consequences resulting from the recently acquired parasite. The key point here is that Wolbachia-induced immune factors activate pre-invasion, contrasting with pathogen-induced factors that activate post-invasion. Compared to the Toll pathway's later activation by DENV, Wolbachia increases its activity before DENV invasion, allowing it to play a more significant role in clearing invasive viruses (Xi, Ramirez, et al., 2008).

Many researchers explained the mechanisms through which Wolbachia activates the immune system of its host. In the case of wAlbB infected Ae. aegypti, Pan et al. (2012) reported increased hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels and a significant increase in the expression of genes that encode NADPH oxidase (NOXM) and Dual Oxidase 2 (DUOX2) enzymes. These enzymes play a role in the production of ROS (Kawahara et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2010). However, an upregulation of antioxidant genes in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes implies the activation of mechanisms to neutralize ROS. Brennan et al. (2008) also show ROS generation and antioxidant protein expression in Wolbachia-infected Ae. albopictus cells. ROS serve as messengers, activating NF-κB, a central regulator, to control immunity, inflammation, and cell survival (Morgan & Liu, 2011).

Pan et al. (2018) demonstrated that Ae. aegypti's IMD and Toll pathways respond to wAlbB introduction, influencing infection levels. Activation increases wAlbB titer, while silencing reduces it, and elevated infection persists through maternal transmission. Remarkably, immune system amplification strongly promotes the synthesis of chemicals that actively promote wAlbB development in Ae. aegypti rather than merely failing to inhibit it. This is likely because there are no specific targets for AMPs in the Wolbachia cell membrane. The mosquito immune pathways trigger the effector molecules, such as Wolbachia-AMPs DEF and CEC, but surprisingly don't impede Wolbachia growth. Wolbachia activates mosquito immune pathways, creating a positive feedback loop that promotes its growth. This immune system boost serves as a survival signal for the successful establishment of a novel Wolbachia symbiosis.

5.4. Phenoloxidase cascade

The third mechanism disrupts arboviral transmission by triggering the phenoloxidase (PO) cascade. Melanin is produced by this cascade, which involves the enzyme phenoloxidase. Melanin exhibits antipathogenic properties when it accumulates around invasive pathogens and at wound sites (Rodriguez-Andres et al., 2012; Thomas et al., 2011). The mosquito's innate immune response to arboviruses depends on this process. Studies reveal that Wolbachia increases melanization in native and non-native arthropod vectors using phenoloxidase activities. Therefore, the phenoloxidase cascade that Wolbachia induces is probably a defence mechanism against different arboviral infections (Rainey et al., 2014).

5.5. miRNA-dependent immune pathways

The miRNA-dependent immune route is the fourth mechanism and it regulates numerous cellular functions, including transposon silencing, antiviral defence, differentiation, timing, cell division, and death, and is greatly aided by miRNAs. This pathway controls arboviral infection in diverse mosquito vectors by regulating arthropod host genes. Hussain et al. (2011) concentrated on comprehending the impact of the wMelPop on cellular miRNAs in female mosquitoes. aae-miR-2940-5p, a mosquito-specific miRNA, is substantially increased in wMelPop-CLA-infected mosquitoes as opposed to uninfected mosquitoes. Mature aae-miR-2940-5p and pelo transcripts were found to co-localize by (Asad, Hussain, et al., 2018), suggesting the potential, in Wolbachia-containing cells, for aae-miR-2940-5p to downregulate the pelo transcripts. The immune response to viral infections consists of RNA interference (RNAi), a protective mechanism (Blair, 2011) that protects mosquitoes against DENV. In Ae. aegypti RNAi is the most important antiviral pathway, shown to reduce the proliferation of multiple viruses (DENV, chikungunya and Sindbis viruses) but seems less crucial for blocking pathogens in naturally Wolbachia-infected insects. Activated by viral dsRNA cleavage, this pathway employs siRNAs to degrade viral ssRNA via cellular machinery. R2D2 and Dicer-2 are essential components of this pathway and if silenced mosquitoes are more susceptible to DENV (Sánchez-Vargas et al., 2009). The RNase III domain of Dcr-2 cleaves the dsRNA after binding of Dicer-2-R2D2 complex to the viral dsRNA, for the formation of siRNA of 21– 23 nucleotides (nt) long. Now the siRNA will initiate the RNAi machinery by binding with RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) which breaks the double-stranded RNA and unwinds one of the siRNA strands keeping the other for targeted degradation of single-stranded viral RNA with sequence complementary to the siRNA by the host endonuclease, Argonaute-2 (Ago2). Although RNAi activates against DENV, it doesn't always stop the virus completely, emphasizing its role but limited effectiveness. To ensure the long-term survival of infected mosquitoes, it might just modify replication of virus to maintain chronic viral infection.

5.6. Wolbachia and specific immunity of Ae. aegypti

Wolbachia infects various tissues in the host, leading to significant impacts on host physiology (Dobson et al., 1999). These effects extend to the cellular, individual, and population levels, affecting gene expression (Xi, Gavotte, et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2011), macromolecule availability (Molloy et al., 2016), and fecundity, (Stouthamer & Luck, 1993). The diversity of Wolbachia’s effects on the host highlights the complexity of this symbiotic relationship. Wolbachia combines reproductive manipulation, like cytoplasmic incompatibility, with mutualistic benefits, such as pathogen protection. The relationship spans a range between parasitism and mutualism. This dual impact makes Wolbachia a promising tool for controlling vector-borne diseases, using its influence on host reproduction and immune enhancement to reduce disease transmission. The mechanism through which Wolbachia provides antiviral protection is still a subject of ongoing research and discussion.

The example of DENV replication being seriously disrupted in the presence of Wolbachia is arguably the most thoroughly researched. Experimental evidence by Asad et al. (2016) supports AeCHD7, a host component in Ae. aegypti, supporting DENV replication, while Wolbachia's downregulation of it may inhibit DENV replication. They also examine whether the CHD family may play a role in the interactions among Wolbachia, Aedes and DENV. CHD proteins are a type of proteins classified within the ATP-dependent chromatin modifiers, specifically belonging to the SNF2 superfamily. Reduction in the expression levels of AeCHD genes is observed in mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. AeCHD7 promotes DENV replication, but Wolbachia reduces its expression in female Ae. aegypti, limiting the replication of DENV. This mechanism is only for female mosquitoes and not universally applicable across different hosts for Wolbachia to inhibit viral replication.

Asad, Parry, et al. (2018) discovered two vago proteins, AeVago1 and AeVago2, in Ae. aegypti. Vago is a special antiviral protein found in insects. They investigated AeVago1 production increased in Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti Without changing the density of Wolbachia, AeVago1 knockdown in Wolbachia-infected cells boosted DENV replication. Based on the data, it appears that AeVago1 which Wolbachia induces in Aag2 cells, prevent DENV replication. Lapidot et al. (2015); (Wu et al., 2014) have revealed the significance of the pelo protein for efficient viral replication, specifically for the Drosophila C virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus TYLCV. Asad, Hussain, et al. (2018) reported that wMelPop-CLA inhibits the pelo protein, and this inhibition might protect Ae. aegypti mosquitoes against DENV particles. Ae. aegypti’s tissues exhibit widespread expression of the pelo gene, with salivary gland expression being especially high but interestingly (Shamsadin et al., 2000), but the presence of Wolbachia results in the suppression of pelo in various cell lines, salivary glands, muscles, and ovaries. In summary, the pelo protein promotes replication of DENV and on the other hand, Wolbachia inhibits the pelo protein in female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, which may reduce DENV in these mosquitoes.

6. Discussion

Early in DENV infection, mosquitoes enhance innate immune genes, but as the infection progresses, it can suppress mosquito defences, through the inhibition of immune-related genes (Sim & Dimopoulos, 2010; Xi, Ramirez, et al., 2008). However, the mosquitoes’ ability to compete with viruses can be modified by their microbiota. Wolbachia, a microbe, inhibit disease transmission by vectors, either by directly blocking virus transmission or reducing mosquito lifespan, but the exact mechanism remains unclear due to Wolbachia's inability to be cultured in a lab. Experimental evidence has repeatedly shown that Wolbachia is effective at preventing the replication of different flaviviruses, such as CHIKV, ZIKV, WNV, and DENV (Dutra et al., 2016; Hussain et al., 2013; Moreira et al., 2009) with numerous studies demonstrating its significant inhibition of DENV replication (Bian et al., 2010; Hughes & Britton, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Transinfecting Wolbachia into Ae. aegypti, a vector not naturally hosting it, effectively inhibited DENV and CHIKV replication (McMeniman et al., 2008). Though much research has been done, the true mechanism or mechanisms through which Wolbachia inhibits viral reproduction in its host environment are still predominantly unknown. Wolbachia is believed to induce pathogen interference by activating the host's innate immune system, particularly immune genes in the Imd and Toll pathways, such as REL1 and REL2. (Bian et al., 2010; Kambris et al., 2009; Moreira et al., 2009). Upregulation of immune effector genes is shown by wMelPop-CLA (Moreira et al., 2009) and wAlbB (Pan et al., 2018) infected Ae. aegypti, by activation of IMD and Toll pathway. This activation increases the density of Wolbachia while turning off these pathways reduces it. The density increase may result from effector molecules that support Wolbachia replication and enhance the immune system. Such as the production of ROS that in turn initiates the Toll pathway (Pan et al., 2012) that is responsible for the inhibition of DENV. It demonstrates a positive feedback loop between the host immune system and Wolbachia density. Another possibility for the observed effects of Wolbachia on DENV could be related to competition for essential nutrients. Cholesterol is recognized as a key fatty acid essential for the successful replication of DENV and Wolbachia. Substantive evidence suggests that wMel competes with the DENV for limited sub-cellular fatty acid resources crucial for viral replication (Hoffmann et al., 2011). Besides this when mosquitoes get infected with DENV there's a natural defence system called autophagy that usually helps the virus grow. Chen and Smartt (2021) discovered a surprising twist that this defence system might fight against the virus. DENV uses autophagy to help it grow. This special kind of autophagy focuses on lipid droplets and changes how the cell works. Interestingly, the Wolbachia hijack the cell's internal process, to acquire nutrients it needs from the host. ATG8a, which indicates activation of autophagy, is found in large amounts in tissues of the host, where Wolbachia is also abundant (Voronin et al., 2012). The reason is that Wolbachia relies on host cells for unsaturated fatty acids and may deplete these fatty acids, upsetting DENV replication. The hypothesis suggests that Wolbachia's presence at high densities could inhibit viruses by competing for cholesterol, but experimental testing is needed for confirmation. Several aspects of immunity have been changed by Wolbachia in Ae. aegypti have been included in this review. Several other mechanisms are still not clear like, the connection between the lncRNA and the Toll pathway as Wolbachia uses lncRNA to activate the Toll pathway. Recent studies are looking at immunity more completely. We discussed novel mechanisms of Wolbachia-mediated innate immune pathways activation in Ae. aegypti. This review provides useful information about using Wolbachia to increase host immunity. Approaches aiming to modify Ae. aegypti's ability to transmit DENV experimentally focuses on specific mosquito immune pathways, with successful interventions enhancing the mosquito's inherent antiviral defence mechanisms. Mosquito strains, carrying Wolbachia are currently bred and experimentally released in areas with a high public health burden of DENV transmission (Carrington et al., 2018; Scott L O'Neill et al., 2018). In the future, studies will try to understand how Wolbachia deals with the immune system, hormones, metabolism, and behaviour of the host. To project the long-term stability of Wolbachia–Ae. aegypti mosquito system that controls mosquitoes and prevents dengue, we need to understand how Wolbachia and the host's immunity work together.

7. Conclusions

Manipulation of mosquitoes’ innate immunity by Wolbachia to control diseases like malaria, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika is a rising strategy these days. However, its successful implementation relies on a thorough understanding of mosquito immunity and interactions with Wolbachia and viruses. This review concludes that Ae. aegypti’s innate immune response is essential to its ability to spread DENV, and using Wolbachia to boost immunity helps prevent DENV transmission. Even while the understanding of the host-Wolbachia-virus relationship has advanced significantly, there are still gaps in our understanding. Although the precise mechanism of antiviral defence is unknown. Determining the mechanism of Wolbachia-induced viral inhibition requires an understanding of mosquito innate immune responses in the presence of Wolbachia. This information is crucial for a major plan against arboviruses.

Author Contributions

The first author MSS make a draft of the manuscript. And great contribution in the writeup of the manuscript IM and IM wrote the whole article.

References

- Ahmad, N. A., Mancini, M.-V., Ant, T. H., Martinez, J., Kamarul, G. M., Nazni, W. A., Hoffmann, A. A., & Sinkins, S. P. Wolbachia strain wAlbB maintains high density and dengue inhibition following introduction into a field population of Aedes aegypti. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2021, 376, 20190809.

- Ant, T. H., Herd, C. S., Geoghegan, V., Hoffmann, A. A., & Sinkins, S. P. The Wolbachia strain wAu provides highly efficient virus transmission blocking in Aedes aegypti. PLoS pathogens 2018, 14, e1006815.

- Antonova, Y., Alvarez, K. S., Kim, Y. J., Kokoza, V., & Raikhel, A. S. The role of NF-κB factor REL2 in the Aedes aegypti immune response. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2009, 39, 303–314. [PubMed]

- Asad, S., Hussain, M., Hugo, L., Osei-Amo, S., Zhang, G., Watterson, D., & Asgari, S. Suppression of the pelo protein by Wolbachia and its effect on dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2018, 12, e0006405.

- Asad, S., Parry, R., & Asgari, S. Upregulation of Aedes aegypti Vago1 by Wolbachia and its effect on dengue virus replication. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2018, 92, 45–52. [PubMed]

- Avadhanula, V., Weasner, B. P., Hardy, G. G., Kumar, J. P., & Hardy, R. W. A novel system for the launch of alphavirus RNA synthesis reveals a role for the Imd pathway in arthropod antiviral response. PLoS pathogens 2009, 5, e1000582.

- Axford, J. K., Ross, P. A., Yeap, H. L., Callahan, A. G., & Hoffmann, A. A. Fitness of wAlbB Wolbachia infection in Aedes aegypti: parameter estimates in an outcrossed background and potential for population invasion. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2016, 94, 507. [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, B. , Su, S., Wang, K., Tian, R., & Chen, M. Identification, expression, and regulation of an omega class glutathione S-transferase in Rhopalosiphum padi (L.)(Hemiptera: Aphididae) under insecticide stress. Frontiers in Physiology 2018, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barletta, A. B. F. , Nascimento-Silva, M. C. L., Talyuli, O. A., Oliveira, J. H. M., Pereira, L. O. R., Oliveira, P. L., & Sorgine, M. H. F. Microbiota activates IMD pathway and limits Sindbis infection in Aedes aegypti. Parasites & vectors 2017, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomeeusen, K. , Daniel, M., LaBeaud, D. A., Gasque, P., Peeling, R. W., Stephenson, K. E., Ng, L. F., & Ariën, K. K. Chikungunya fever. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2023, 9, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S. , Kim, H., Kearns, J. D., Tergaonkar, V., O'Dea, E., Werner, S. L., Benedict, C. A., Ware, C. F., Ghosh, G., & Verma, I. M. A fourth IκB protein within the NF-κB signaling module. Cell 2007, 128, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, J. F. , Ronau, J. A., & Hochstrasser, M. A Wolbachia deubiquitylating enzyme induces cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature Microbiology 2017, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, G. , Xu, Y., Lu, P., Xie, Y., & Xi, Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathogens 2010, 6, e1000833. [Google Scholar]

- Birben, E. , Sahiner, U. M., Sackesen, C., Erzurum, S., & Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organization Journal 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blagrove, M. S. , Arias-Goeta, C., Di Genua, C., Failloux, A.-B., & Sinkins, S. P. A Wolbachia wMel transinfection in Aedes albopictus is not detrimental to host fitness and inhibits Chikungunya virus. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2013, 7, e2152. [Google Scholar]

- Blagrove, M. S., Arias-Goeta, C., Failloux, A.-B., & Sinkins, S. P. Wolbachia strain wMel induces cytoplasmic incompatibility and blocks dengue transmission in Aedes albopictus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 255–260.

- Blair, C. D. Mosquito RNAi is the major innate immune pathway controlling arbovirus infection and transmission. Future Microbiology 2011, 6, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonizzoni, M. , Dunn, W. A., Campbell, C. L., Olson, K. E., Marinotti, O., & James, A. A. Complex modulation of the Aedes aegypti transcriptome in response to dengue virus infection. PLoS One 2012, 7, e50512. [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K. , Pettigrew, M., & O’Neill, S. L. Wolbachia neither induces nor suppresses transcripts encoding antimicrobial peptides. Insect Molecular Biology 2000, 9, 635–639. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L. J. , Keddie, B. A., Braig, H. R., & Harris, H. L. The endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis induces the expression of host antioxidant proteins in an Aedes albopictus cell line. PLoS One 2008, 3, e2083. [Google Scholar]

- Caragata, E. P. , Rancès, E., O’Neill, S. L., & McGraw, E. A. Competition for amino acids between Wolbachia and the mosquito host, Aedes aegypti. Microbial Ecology 2014, 67, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, L. B. , Tran, B. C. N., Le, N. T. H., Luong, T. T. H., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, P. T., Nguyen, C. V. V., Nguyen, H. T. C., Vu, T. T., & Vo, L. T. Field-and clinically derived estimates of Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus transmission potential in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-H. , Chiang, Y.-H., Hou, J.-N., Cheng, C.-C., Sofiyatun, E., Chiu, C.-H., & Chen, W.-J. XBP1-mediated BiP/GRP78 upregulation copes with oxidative stress in mosquito cells during dengue 2 virus infection. BioMed Research International 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.-H. , Tang, P., Yang, C.-F., Kao, L.-H., Lo, Y.-P., Chuang, C.-K., Shih, Y.-T., & Chen, W.-J. Antioxidant defense is one of the mechanisms by which mosquito cells survive dengue 2 viral infection. Virology 2011, 410, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.-Y. , & Smartt, C. T. Activation of the autophagy pathway decreases dengue virus infection in Aedes aegypti cells. Parasites & Vectors 2021, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- DeLotto, Y., & DeLotto, R. Proteolytic processing of the Drosophila Spätzle protein by easter generates a dimeric NGF-like molecule with ventralising activity. Mechanisms of Development 1998, 72(1-2), 141-148.

- Dobson, S. L. , Bourtzis, K., Braig, H. R., Jones, B. F., Zhou, W., Rousset, F., & O'Neill, S. L. Wolbachia infections are distributed throughout insect somatic and germ line tissues. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 1999, 29, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duong Thi Hue, K., da Silva Goncalves, D., Tran Thuy, V., Thi Vo, L., Le Thi, D., Vu Tuyet, N., Nguyen Thi, G., Huynh Thi Xuan, T., Nguyen Minh, N., & Nguyen Thanh, P. Wolbachia wMel strain-mediated effects on dengue virus vertical transmission from Aedes aegypti to their offspring. Parasites & vectors 2023, 16, 308.

- Dutra, H. L. C. , Rocha, M. N., Dias, F. B. S., Mansur, S. B., Caragata, E. P., & Moreira, L. A. Wolbachia blocks currently circulating Zika virus isolates in Brazilian Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Cell Host & Microbe 2016, 19, 771–774. [Google Scholar]

- Edenborough, K. M. , Flores, H. A., Simmons, C. P., & Fraser, J. E. Using Wolbachia to eliminate dengue: Will the virus fight back? Journal of Virology 2021, 95, e02203–02220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, N. M. , Hue Kien, D. T., Clapham, H., Aguas, R., Trung, V. T., Bich Chau, T. N., Popovici, J., Ryan, P. A., O’Neill, S. L., & McGraw, E. A. Modeling the impact on virus transmission of Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus infection of Aedes aegypti. Science translational medicine 2015, 7, 279ra237–279ra237. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, P. M. , Frydman, H. M., Li, J. M., Cao, J., Wieschaus, E., & Sullivan, W. Wolbachia utilizes host microtubules and Dynein for anterior localization in the Drosophila oocyte. PLoS Pathogens 2005, 1, e14. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, H. A. , Taneja de Bruyne, J., O’Donnell, T. B., Tuyet Nhu, V., Thi Giang, N., Thi Xuan Trang, H., Thi Thuy Van, H., Thi Long, V., Thi Dui, L., & Le Anh Huy, H. Multiple Wolbachia strains provide comparative levels of protection against dengue virus infection in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008433. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, K. Y. , & Chee, H.-Y. Interaction between flavivirus and cytoskeleton during virus replication. Interaction between flavivirus and cytoskeleton during virus replication. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, S. A. , Allen, S. L., Ohm, J. R., Sigle, L. T., Sebastian, A., Albert, I., Chenoweth, S. F., & McGraw, E. A. Selection on Aedes aegypti alters Wolbachia-mediated dengue virus blocking and fitness. Nature Microbiology 2019, 4, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- FRA, K. Wolbachia goes to work in the war on mosquitoes. Nature 2021, 598, S33. [Google Scholar]

- Frentiu, F. D. , Robinson, J., Young, P. R., McGraw, E. A., & O'Neill, S. L. Wolbachia-mediated resistance to dengue virus infection and death at the cellular level. Plos one 2010, 5, e13398. [Google Scholar]

- Frentiu, F. D. , Zakir, T., Walker, T., Popovici, J., Pyke, A. T., van den Hurk, A., McGraw, E. A., & O'Neill, S. L. Limited dengue virus replication in field-collected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014, 8, e2688. [Google Scholar]

- Garver, L. S. , Bahia, A. C., Das, S., Souza-Neto, J. A., Shiao, J., Dong, Y., & Dimopoulos, G. Anopheles Imd pathway factors and effectors in infection intensity-dependent anti-Plasmodium action. PLoS pathogens 2012, 8, e1002737. [Google Scholar]

- Garver, L. S. , Dong, Y., & Dimopoulos, G. Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS pathogens 2009, 5, e1000335. [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan, V. , Stainton, K., Rainey, S. M., Ant, T. H., Dowle, A. A., Larson, T., Hester, S., Charles, P. D., Thomas, B., & Sinkins, S. P. Perturbed cholesterol and vesicular trafficking associated with dengue blocking in Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti cells. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 526. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie and, J. P. , Kanost, M. R., & Trenczek, T. Biological mediators of insect immunity. Annual review of entomology 1997, 42, 611–643. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. , Xu, Y., Bian, G., Pike, A. D., Xie, Y., & Xi, Z. Response of the mosquito protein interaction network to dengue infection. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Haqshenas, G. , Terradas, G., Paradkar, P. N., Duchemin, J.-B., McGraw, E. A., & Doerig, C. A role for the insulin receptor in the suppression of dengue virus and Zika virus in Wolbachia-infected mosquito cells. Cell Reports 2019, 26, 529–535.e523. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A. , Montgomery, B., Popovici, J., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Johnson, P., Muzzi, F., Greenfield, M., Durkan, M., Leong, Y., & Dong, Y. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 2011, 476, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hue, K. D. T., Goncalves, D. S., Vi, T. T., Long, V. T., Nhu, V. T. T., Giang, N. T., Trang, H. T. X., Nguyet, N. M., Phong, N. T., & Yacoub, S. (2023). Wolbachia wMel-mediated effects on dengue virus vertical transmission from Aedes aegypti to their offspring.

- Hughes, H. , & Britton, N. F. Modelling the use of Wolbachia to control dengue fever transmission. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2013, 75, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hugo, L. E., Rašić, G., Maynard, A. J., Ambrose, L., Liddington, C., Thomas, C. J., Nath, N. S., Graham, M., Winterford, C., & Wimalasiri-Yapa, B. R. Wolbachia wAlbB inhibit dengue and Zika infection in the mosquito Aedes aegypti with an Australian background. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16, e0010786.

- Hussain, M. , & Asgari, S. MicroRNA-like viral small RNA from Dengue virus 2 autoregulates its replication in mosquito cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M., Frentiu, F. D., Moreira, L. A., O'Neill, S. L., & Asgari, S. Wolbachia uses host microRNAs to manipulate host gene expression and facilitate colonization of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 9250–9255.

- Hussain, M. , Lu, G., Torres, S., Edmonds, J. H., Kay, B. H., Khromykh, A. A., & Asgari, S. Effect of Wolbachia on replication of West Nile virus in a mosquito cell line and adult mosquitoes. Journal of Virology 2013, 87, 851–858. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M. , Zhang, G., Leitner, M., Hedges, L. M., & Asgari, S. Wolbachia RNase HI contributes to virus blocking in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Iscience 2023, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Indriani, C., Tantowijoyo, W., Rancès, E., Andari, B., Prabowo, E., Yusdi, D., Ansari, M. R., Wardana, D. S., Supriyati, E., & Nurhayati, I. Reduced dengue incidence following deployments of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: a quasi-experimental trial using controlled interrupted time series analysis. Gates open research 2020, 4.

- Johnson, K. N. The impact of Wolbachia on virus infection in mosquitoes. Viruses 2015, 7, 5705–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupatanakul, N. , Sim, S., Angleró-Rodríguez, Y. I., Souza-Neto, J., Das, S., Poti, K. E., Rossi, S. L., Bergren, N., Vasilakis, N., & Dimopoulos, G. Engineered Aedes aegypti JAK/STAT pathway-mediated immunity to dengue virus. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11, e0005187. [Google Scholar]

- Kambris, Z. , Cook, P. E., Phuc, H. K., & Sinkins, S. P. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science 2009, 326, 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kamtchum-Tatuene, J. , Makepeace, B. L., Benjamin, L., Baylis, M., & Solomon, T. The potential role of Wolbachia in controlling the transmission of emerging human arboviral infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2017, 30, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, T. , Quinn, M. T., & Lambeth, J. D. Molecular evolution of the reactive oxygen-generating NADPH oxidase (Nox/Duox) family of enzymes. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2007, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kokoza, V. , Ahmed, A., Woon Shin, S., Okafor, N., Zou, Z., & Raikhel, A. S. Blocking of Plasmodium transmission by cooperative action of Cecropin A and Defensin A in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 8111–8116. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A. , Srivastava, P., Sirisena, P., Dubey, S. K., Kumar, R., Shrinet, J., & Sunil, S. Mosquito innate immunity. Insects 2018, 9, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Molina-Cruz, A., Gupta, L., Rodrigues, J., & Barillas-Mury, C. A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science 2010, 327, 1644–1648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lapidot, M. , Karniel, U., Gelbart, D., Fogel, D., Evenor, D., Kutsher, Y., Makhbash, Z., Nahon, S., Shlomo, H., & Chen, L. A novel route controlling begomovirus resistance by the messenger RNA surveillance factor pelota. PLoS Genetics 2015, 11, e1005538. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-R. , Lei, H.-Y., Liu, M.-T., Wang, J.-R., Chen, S.-H., Jiang-Shieh, Y.-F., Lin, Y.-S., Yeh, T.-M., Liu, C.-C., & Liu, H.-S. Autophagic machinery activated by dengue virus enhances virus replication. Virology 2008, 374, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C. , Yang, C.-F., Tu, C.-H., Huang, C.-G., Shih, Y.-T., Chuang, C.-K., & Chen, W.-J. A novel tetraspanin C189 upregulated in C6/36 mosquito cells following dengue 2 virus infection. Virus Research 2007, 124, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, A. R. , Bhattacharya, T., Hardy, R. W., & Newton, I. L. Wolbachia and virus alter the host transcriptome at the interface of nucleotide metabolism pathways. Mbio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.-L., Yu, H.-Y., Chen, Y.-X., Chen, B.-Y., Leaw, S. N., Lin, C.-H., Su, M.-P., Tsai, L.-S., Chen, Y., & Shiao, S.-H. Lab-scale characterization and semi-field trials of Wolbachia strain wAlbB in a Taiwan Wolbachia introgressed Ae. aegypti strain. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16, e0010084.

- Loterio, R. K., Monson, E. A., Templin, R., de Bruyne, J. T., Flores, H. A., Mackenzie, J. M., Ramm, G., Helbig, K. J., Simmons, C. P., & Fraser, J. E. (2023). Antiviral Wolbachia strains associate with Aedes aegypti endoplasmic reticulum membranes and induce lipid droplet formation to restrict dengue virus replication. mBio, e02495-02423.

- Lu, P., Bian, G., Pan, X., & Xi, Z. Wolbachia induces density-dependent inhibition to dengue virus in mosquito cells. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2012, 6, e1754.

- Lu, P., Sun, Q., Fu, P., Li, K., Liang, X., & Xi, Z. Wolbachia inhibits binding of dengue and Zika viruses to mosquito cells. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 1750.

- Luplertlop, N. , Surasombatpattana, P., Patramool, S., Dumas, E., Wasinpiyamongkol, L., Saune, L., Hamel, R., Bernard, E., Sereno, D., & Thomas, F. Induction of a peptide with activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens in the Aedes aegypti salivary gland, following infection with dengue virus. PLoS Pathogens 2011, 7, e1001252. [Google Scholar]

- Manokaran, G., Flores, H. A., Dickson, C. T., Narayana, V. K., Kanojia, K., Dayalan, S., Tull, D., McConville, M. J., Mackenzie, J. M., & Simmons, C. P. Modulation of acyl-carnitines, the broad mechanism behind Wolbachia-mediated inhibition of medically important flaviviruses in Aedes aegypti. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 24475–24483.

- Matthews, B. J., Dudchenko, O., Kingan, S., Koren, S., Antoshechkin, I., Crawford, J. E., Glassford, W. J., Herre, M., Redmond, S. N., & Rose, N. H. Improved Aedes aegypti mosquito reference genome assembly enables biological discovery and vector control. BioRxiv 2017, 240747.

- McMeniman, C. J. , Lane, A. M., Fong, A. W., Voronin, D. A., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Yamada, R., McGraw, E. A., & O'Neill, S. L. Host adaptation of a Wolbachia strain after long-term serial passage in mosquito cell lines. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2008, 74, 6963–6969. [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman, C. J. , Lane, R. V., Cass, B. N., Fong, A. W., Sidhu, M., Wang, Y.-F., & O'Neill, S. L. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. science 2009, 323, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, J. C. , Sommer, U., Viant, M. R., & Sinkins, S. P. Wolbachia modulates lipid metabolism in Aedes albopictus mosquito cells. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2016, 82, 3109–3120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moreira, L. A. , Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Jeffery, J. A., Lu, G., Pyke, A. T., Hedges, L. M., Rocha, B. C., Hall-Mendelin, S., Day, A., & Riegler, M. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 2009, 139, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M. J. , & Liu, Z.-g. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Research 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, D. , Das, S., Begum, F., Mal, S., & Ray, U. The mosquito immune system and the life of dengue virus: what we know and do not know. Pathogens 2019, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nazni, W. A. , Hoffmann, A. A., NoorAfizah, A., Cheong, Y. L., Mancini, M. V., Golding, N., Kamarul, G. M., Arif, M. A., Thohir, H., & NurSyamimi, H. Establishment of Wolbachia strain wAlbB in Malaysian populations of Aedes aegypti for dengue control. Current biology 2019, 29, 4241–4248.e4245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nene, V. , Wortman, J. R., Lawson, D., Haas, B., Kodira, C., Tu, Z., Loftus, B., Xi, Z., Megy, K., & Grabherr, M. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science 2007, 316, 1718–1723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O'Connor, L. , Plichart, C., Sang, A. C., Brelsfoard, C. L., Bossin, H. C., & Dobson, S. L. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a Wolbachia biopesticide: field performance and infection containment. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2012, 6, e1797. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill, S. L., Ryan, P. A., Turley, A. P., Wilson, G., Retzki, K., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Dong, Y., Kenny, N., Paton, C. J., & Ritchie, S. A. Scaled deployment of Wolbachia to protect the community from dengue and other Aedes transmitted arboviruses. Gates open research 2018, 2.

- O'Neill, S. L. , Ryan, P. A., Turley, A. P., Wilson, G., Retzki, K., Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I., Dong, Y., Kenny, N., Paton, C. J., Ritchie, S. A., Brown-Kenyon, J., Stanford, D., Wittmeier, N., Jewell, N. P., Tanamas, S. K., Anders, K. L., & Simmons, C. P. Scaled deployment of Wolbachia to protect the community from dengue and other Aedes transmitted arboviruses. Gates open research 2018, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochani, S. , Ochani, S., Ochani, A., Ochani, K., Adnan, A., & Ullah, K. The ongoing surge of dengue amidst a multidemic era in Pakistan. IJS Global Health 2023, 6, e125. [Google Scholar]

- Pacidônio, E. C. , Caragata, E. P., Alves, D. M., Marques, J. T., & Moreira, L. A. The impact of Wolbachia infection on the rate of vertical transmission of dengue virus in Brazilian Aedes aegypti. Parasites & vectors 2017, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Paingankar, M. S. , Gokhale, M. D., & Deobagkar, D. N. Dengue-2-virus-interacting polypeptides involved in mosquito cell infection. Archives of Virology 2010, 155, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, X. , Pike, A., Joshi, D., Bian, G., McFadden, M. J., Lu, P., Liang, X., Zhang, F., Raikhel, A. S., & Xi, Z. The bacterium Wolbachia exploits host innate immunity to establish a symbiotic relationship with the dengue vector mosquito Aedes aegypti. The ISME Journal 2018, 12, 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., Zhou, G., Wu, J., Bian, G., Lu, P., Raikhel, A. S., & Xi, Z. Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the Toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, E23-E31.

- Perera, R. , Riley, C., Isaac, G., Hopf-Jannasch, A. S., Moore, R. J., Weitz, K. W., Pasa-Tolic, L., Metz, T. O., Adamec, J., & Kuhn, R. J. Dengue virus infection perturbs lipid homeostasis in infected mosquito cells. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8, e1002584. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, S. B. , Riback, T. I., Sylvestre, G., Costa, G., Peixoto, J., Dias, F. B., Tanamas, S. K., Simmons, C. P., Dufault, S. M., & Ryan, P. A. Effectiveness of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments in reducing the incidence of dengue and other Aedes-borne diseases in Niterói, Brazil: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15, e0009556. [Google Scholar]

- Pompon, J. , Manuel, M., Ng, G. K., Wong, B., Shan, C., Manokaran, G., Soto-Acosta, R., Bradrick, S. S., Ooi, E. E., & Missé, D. Dengue subgenomic flaviviral RNA disrupts immunity in mosquito salivary glands to increase virus transmission. PLoS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006535. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, S. M. , Shah, P., Kohl, A., & Dietrich, I. Understanding the Wolbachia-mediated inhibition of arboviruses in mosquitoes: progress and challenges. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95, 517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, J. L., & Dimopoulos, G. The Toll immune signaling pathway control conserved anti-dengue defenses across diverse Ae. aegypti strains and against multiple dengue virus serotypes. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2010, 34, 625–629.

- Rancès, E. , Ye, Y. H., Woolfit, M., McGraw, E. A., & O'Neill, S. L. The relative importance of innate immune priming in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8, e1002548. [Google Scholar]

- Rašić, G. , Endersby, N. M., Williams, C., & Hoffmann, A. A. Using Wolbachia-based release for suppression of Aedes mosquitoes: insights from genetic data and population simulations. Ecological Applications 2014, 24, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, J. I. L. , Suzuki, Y., Carvajal, T., Muñoz, M. N. M., & Watanabe, K. Intracellular interactions between arboviruses and Wolbachia in Aedes aegypti. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 690087. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro dos Santos, G., Durovni, B., Saraceni, V., Souza Riback, T. I., Pinto, S. B., Anders, K. L., Moreira, L. A., & Salje, H. Estimating the impact of the wMel release program on dengue and chikungunya incidence in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. medRxiv 2022, 2022.2003. 2029.22273035.

- Riparbelli, M. G., Giordano, R., Ueyama, M., & Callaini, G. Wolbachia-mediated male killing is associated with defective chromatin remodeling. PloS One 2012, 7, e30045.

- Rodriguez-Andres, J. , Rani, S., Varjak, M., Chase-Topping, M. E., Beck, M. H., Ferguson, M. C., Schnettler, E., Fragkoudis, R., Barry, G., & Merits, A. Phenoloxidase activity acts as a mosquito innate immune response against infection with Semliki Forest virus. PLoS Pathogens 2012, 8, e1002977. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset, F., Bouchon, D., Pintureau, B., Juchault, P., & Solignac, M. Wolbachia endosymbionts responsible for various alterations of sexuality in arthropods. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1992, 250, 91–98.

- Ryan, P. A., Turley, A. P., Wilson, G., Hurst, T. P., Retzki, K., Brown-Kenyon, J., Hodgson, L., Kenny, N., Cook, H., & Montgomery, B. L. Establishment of wMel Wolbachia in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and reduction of local dengue transmission in Cairns and surrounding locations in northern Queensland, Australia. Gates open research 2019, 3.

- Salazar, M. I. , Richardson, J. H., Sánchez-Vargas, I., Olson, K. E., & Beaty, B. J. Dengue virus type 2: replication and tropisms in orally infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. BMC Microbiology 2007, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vargas, I. , Scott, J. C., Poole-Smith, B. K., Franz, A. W., Barbosa-Solomieu, V., Wilusz, J., Olson, K. E., & Blair, C. D. Dengue virus type 2 infections of Aedes aegypti are modulated by the mosquito's RNA interference pathway. PLoS Pathogens 2009, 5, e1000299. [Google Scholar]