5.2.1. Effectiveness validation under small-batch instances

36 configurations, each of 30 instances, are solved using the proposed heuristic and algorithm . Each configuration has containers, in which S is the number of stacks of the bay, T is the maximum number of tiers in a stack, and the is the occupancy rate of the slots in the bay. In this experiment, the value of S varies between 5 and 10, and the T varies between 3 and 6. The is divided into two cases: 50% and 67%.

The experiments aim to validate the effectiveness of our algorithms. Usually, many container terminals stack their containers in not more than six tiers, and there are rare cases in which the number of target containers within a bay during an operation round is more than 5. Suppose our algorithms perform well regarding runtime and optimization objectives under small-batch instances. In that case, our algorithm can be applied to most container terminals.

(1) Comparison of complete time

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the experiment’s results of Case 1 with two storage space occupancy rates, 50% and 67%. The rows labeled as “C” indicate the container number of each configuration, and the rows labeled as “Solved” show us the number of instances solved in the form

. We can find that all 30 instances for each configuration are solved optimally by the algorithm

and heuristic

, respectively. The solution time in the two tables refers to the runtime of the most time-consuming instance of each configuration. The running time of the algorithms is related to the number, the location of target containers per batch, and the bay layout. Since we introduce the flexible pick-up order mechanism into our algorithms, iterating through all possible pick-up sequences may result in a more time-consuming solution process. The worst case in

Table 1 is that an instance with configuration (5 stacks and three layers) and with 67% fill rate has four target containers, and it takes about 0.134 seconds to solve, which exceeds ten times that of the solution time of the other instances. In this case, the solution time of most instances is less than 0.02s.

(2) Analysis of the results

Table 3 and

Table 4 show us the experiment results of the

heuristic and

algorithm under 50% and 67% fill rate, respectively. In the two tables, the notation “

” refers to the initial number of blocking containers for each instance. Its value equals the sum of the number of forced relocations and potential relocations of a bay’s initial layout, determined by the number of the

inverted-placement and

level-placement containers, respectively. Considering that the pickup order is adjustable during the realized operations, some potential relocations (determined by

level-placement containers) may not occur in the realized operations. So, the actual number of relocations (

for short) generated during practical operations may be smaller than the theoretical value (

). The

indicates the sum of the increment in the expected number of new additional blocking containers and the number of movements other than the forced relocations during all operation rounds of a bay.

Columns and indicate each configuration’s average values of 30 instances. The is nearly half the sum of the maximum and minimum values of the initial expected number of blocking containers in a bay. In addition, the value of increased gradually with the size of the instance configurations. However, its standard deviation does not reflect a clear pattern, indicating a high degree of randomness in the data of the instances. In other words, it has a high degree of representativeness in the data of the instances in this study. The values of heuristic are significantly different from those of the algorithm due to the differences between the two methods. The heuristic only employs the flexible pick-up order policy, whereas the algorithm incorporates, in addition to this, two relocation rules— rule and rule. So, the values of the algorithm contain many relocations generated by the two relocation rules, which would be required in subsequent rounds and were executed in advance by the two relocation rules.

Table 5 shows each configuration’s actual number of relocations (

), obtained by simulating the optimal operation plan for each round. According to Eq.

8, the value of

is smaller than the value of

and is closer to the optimal solution. Column

G denotes the error rate between

and

(the value equals

). We find a negative value in column

G of the

heuristic at a fill rate of 50%, which indicates that the value of

is more than

, the theoretical upper bound of the CRP model. Similarly, more such cases appear in column

G of the

heuristic at a fill rate of 67%. The reason for this is because the

heuristic, when selecting a position for the blocking container, will prioritize a

level stack in the absence of sequential candidate stacks (selecting

level stack produces an increment of the expected number of potential blocking container less than 1). However, some potential blocking containers turn out to be real during subsequent operations (producing one realized relocation), so there are more realized relocations than the theoretical optimal operation solution. However, this case does not appear in column

G of the

algorithm because the

algorithm reduces the selection of

level stacks through both relocation rules —

and

so that the performance of the theoretical upper bound of the

algorithm meets the anticipative optimization objective. In terms of the values of

, they are much larger in the

algorithm than in the

heuristic because the

and

rules perform some relocations in advance or freeing up the

sequential stacks for the blocking containers, which in fact would cause relocations inevitably during the subsequent operations. These advance relocations are counted in

and

. Therefore, the

algorithm generally shows a stable optimization effect regarding the number of actual relocations.

(3) Comparison between heuristic and algorithm

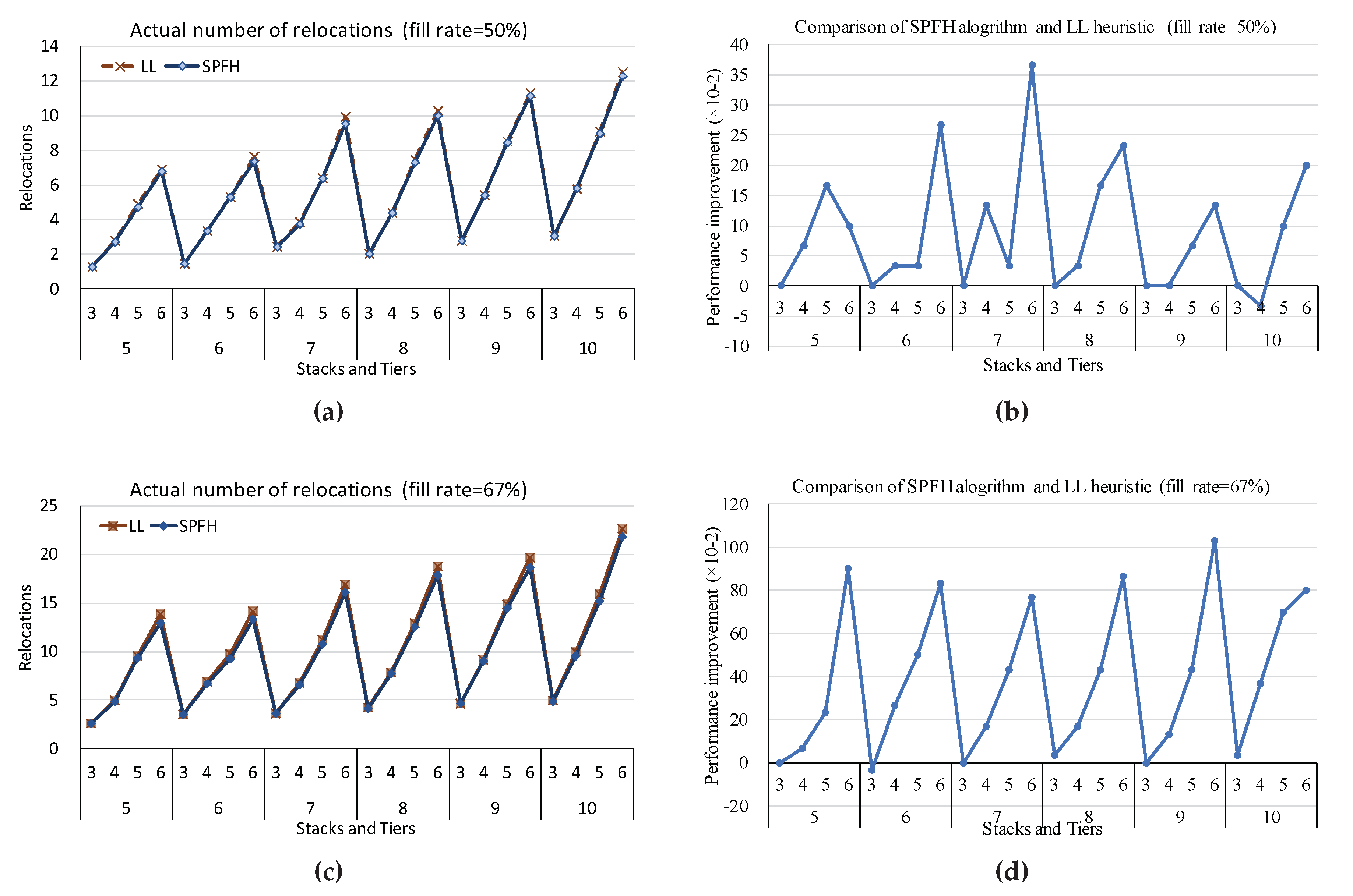

As shown in

Figure 5 (a) and (c), the

values of

and

are very close to each other and are even identical when the number of stack tiers is equal to three.

Figure 5 (b) and (d) demonstrate the error of the two algorithms at fill rate 50% and 67%, respectively, and the results of the

algorithm perform better than that of the

heuristic. Meanwhile, we find that the

values increase with the number of stacks and the number of stack tiers, where the number of stacks has a slight effect on the value of

while the increase in the number of stack tiers brings about a rapid increase of the value of

. The errors between the

algorithm and the

heuristic also have the same trend.

5.2.2. Effectiveness validation under large-batch instances

In this case, the configuration sizes of the experimental instances vary from stacks and tiers. These experimental parameters meet the current production conditions of the busier container terminals and their development trends.

Table 6 summarises the validation of the algorithm

and the heuristic

for the large-size instances (each instance has

operation rounds and each round has

target containers) in the real-time operation scenarios. The column titled “MT” refers to the runtime of the most time-consuming instance out of 30 instances. The column “AT” refers to the average runtime of 30 instances. The meanings of other variables, namely

I,

,

, and

, are the same as those in the previous tables.

The results in

Table 6 imply that both algorithms

and

can solve most instances quickly. However, when the number of target containers per round exceeds 9, the solution time of a few cases exceeds 3600 seconds, which means that the algorithms can no longer meet the needs of real-time optimization operations. Fortunately, in the actual operation scenario, there are rarely more than nine target containers during a real-time operation round.

The reason for the time-consuming solution process in the large-size batch instances is that the flexible pickup order mechanism requires iterating through all possible target pickup orders during the real-time operation round to explore the optimal operation plan. The number of iterations of the solution process increases rapidly with the target container number (n), which is approximately equal to . Two perspectives can be considered to solve this problem: First, reducing the solution quality, using heuristics for selecting target containers (e.g., always retrieving the target containers with the lowest number of blocking containers) instead of complete iteration to improve the solution efficiency and second, dividing the current larger batch into several smaller batches before processing, e.g., the current batch of 10 containers is divided into two small batches of 5 containers.