Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Description

2.1. Problem Statement

2.2. Problem Assumptions

2.3. Decision Variables and Parameters

2.4 Mathematical Model

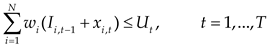

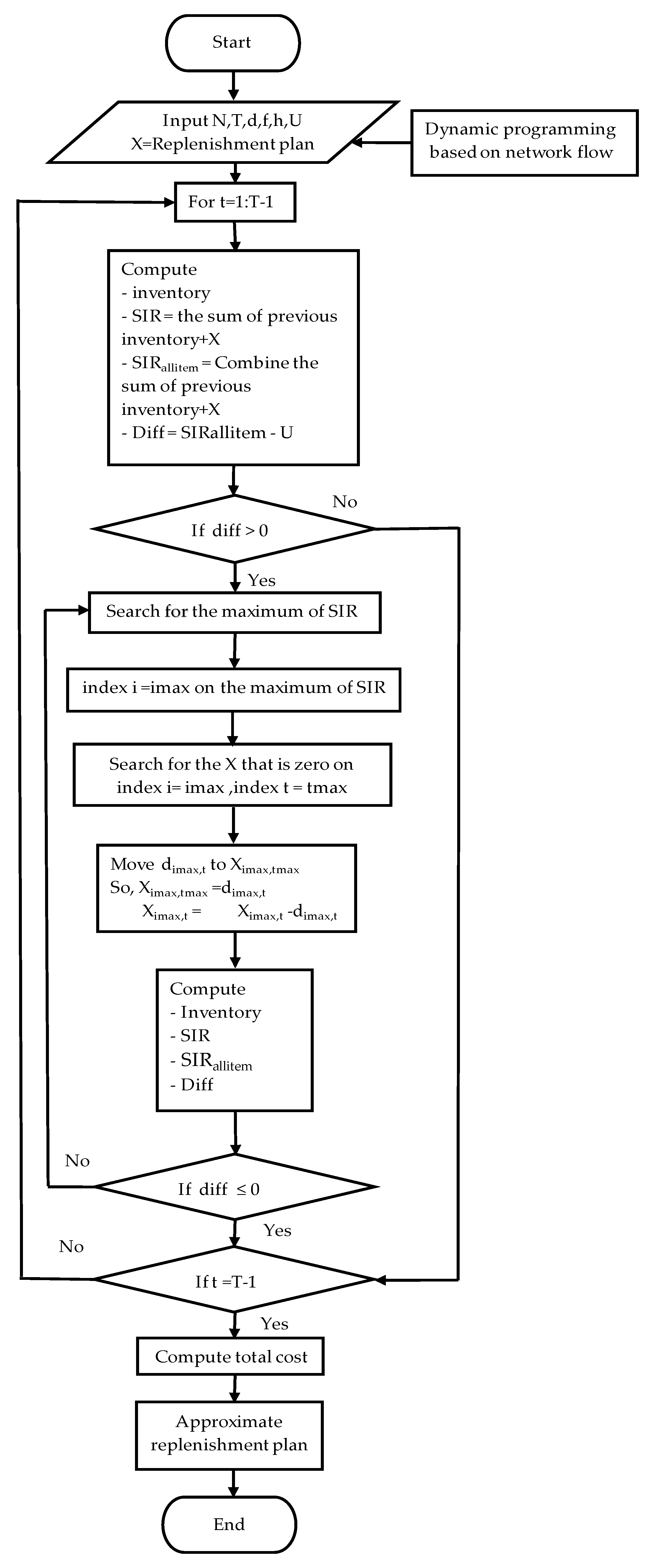

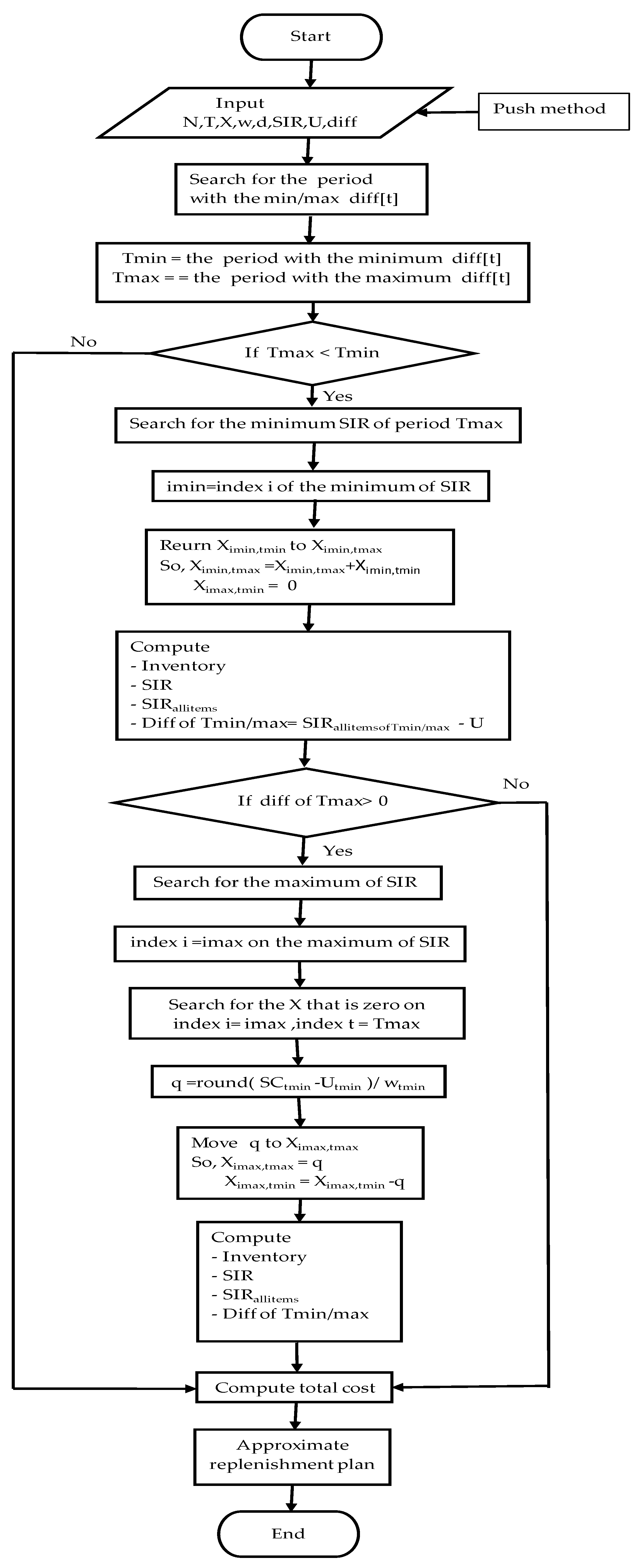

3. The Proposed Heuristic

3.1. The Push Method

3.2. The Pull Method

4. A Numerical Example

4.1. The Initial Solution

4.2. Solution of the Push Method

- Select item 1, which has the maximum SIR (SIRmax) of 567, and find period tzero = 5 on item 1, which has an inventory cost of zero.

- Insert the replenished quantity, which equals the demand of item 1 for period tzero =

- 136 units, on a replenished plan on item 1 for period tzero. For balance demand, de

- crease the replenishment of item 1 for period 1 to 567-136 =431 units.

- Balance a replenished plan and update inventory, SIR,SIRallitems, SIRallitems_U, and total inventory cost (see Table 4).

- SIRallitems_U for period 1 is reduced to 987-756 = +231. Afterward, go to steps 1-4.

- Select item 2, which has SIRmax of 556, and find period tzero = 2 on item 2, which has an inventory cost of zero.

- Insert the replenished quantity, which equals the demand of item 2 for period tzero = 52 units, on a replenished plan on item 2 for period tzero. For balance demand,

- decrease the replenishment of item 2 for period 1 to 139-52 =87 units.

- Balance a replenished plan and update inventory, SIR, SIRallitems, SIRallitems_U, and

- total inventory cost (see Table 5).

- SIRallitems_U for period 2 is still reduced to 779-756 = +23. Then, go to steps 1- 4.

- Select item 1, which has SIRmax of 431, and find period tzero = 4 on item 1, which has an inventory cost of zero.

- Insert the replenished quantity, which equals the demand of item 2 for period tzero= 106 units, on a replenished plan on item 1 for period tzero. For balance demand, decrease the replenishment of item 1 for period 1 to 431-106 = 325 units.

- Balance a replenished plan and update inventory, SIR,SIRallitems, SIRallitems_U, and total

- inventory cost (see Table 6).

- SIRallitems_U for period 1 is reduced to 673-756 = -83. Stop the iteration and select period 3, which has the SIRallitems_U value of +947. Proceed to steps 1-4 for period 3.

- Select item 2, which has SIRmax of 1,484, and find period tzero = 5 on item 2, which has

- an inventory cost of zero.

- Insert the replenished quantity, which equals the demand of item 2 for period tzero=118 units, on a replenished plan on item 2 at period tzero. For balance demand, decrease the replenishment of item 2 for period 3 to 371-118 = 253 units.

- Balance a replenished plan and update inventory, SIR,SIRallitems, SIRallitems_U,

- and total inventory cost (see Table 7).

- SIRallitems_U for period 3 is still reduced to 1,108-633 = +475. Afterward, go to steps 1- 4.

- Select item 2, which has SIRmax of 348, and find period tzero = 4 on item 2,

- which has an inventory cost of zero.

- Insert the replenishment, which equals the demand of item 2 at period tzero =

- 142 units on a replenished plan on item 2 at period tzero. For balance demand, decrease the replenishment of item 2 at period 3 to 253-142 = 111 units.

- Balance a replenished plan and update inventory, SIR,SIRallitems, SIRallitems_U,

- and total inventory cost (see Table 8).

- SIRallitems_U for period 3 is reduced to 540-633= = -93. Stop the loop at

- period 3. Then, find the next SIRallitems_U to be positive. However, all SIRallitems_U values are negative and zero (-83, -255, -93, -84, 0). Thereafter, stop all iterations of the push method.

4.3. Solution of the Pull Method

- Search the SIRallitems_Umin and SIRallitems_SCmax to be -255 and -83 for periods 2 and 1 from Table 8. So,the index of both periods is tmin=2 and tmax=1. So, tmin is more than tmax.

- Find the SIRmin for period tmin to be 208 on item 2 from Table 8. Return the replenishment of item 2 at period 2 to add the original replenished quantity on item 2 for period tmax=1. Thus, the new amount replenished quantity of item 2 for period 1 is 87+52 = 139 units. For balance demand, the replenished quantity of item 2 for period tmin is reduced to zero (see Table 9).

5. Computational Result

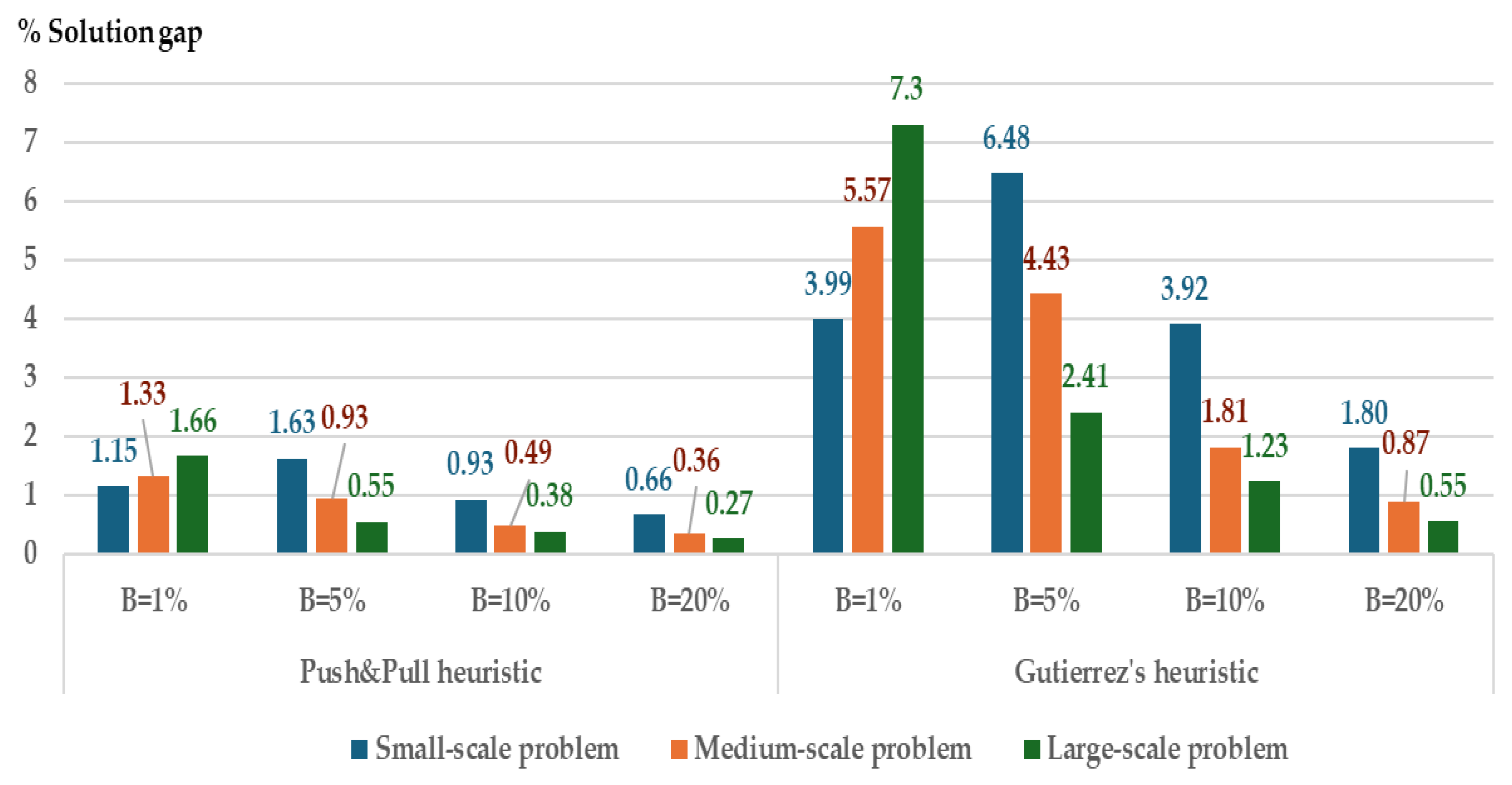

5.1. Experiment Results

5.1. Solution Gap

5.2. Worst Cases Analysis

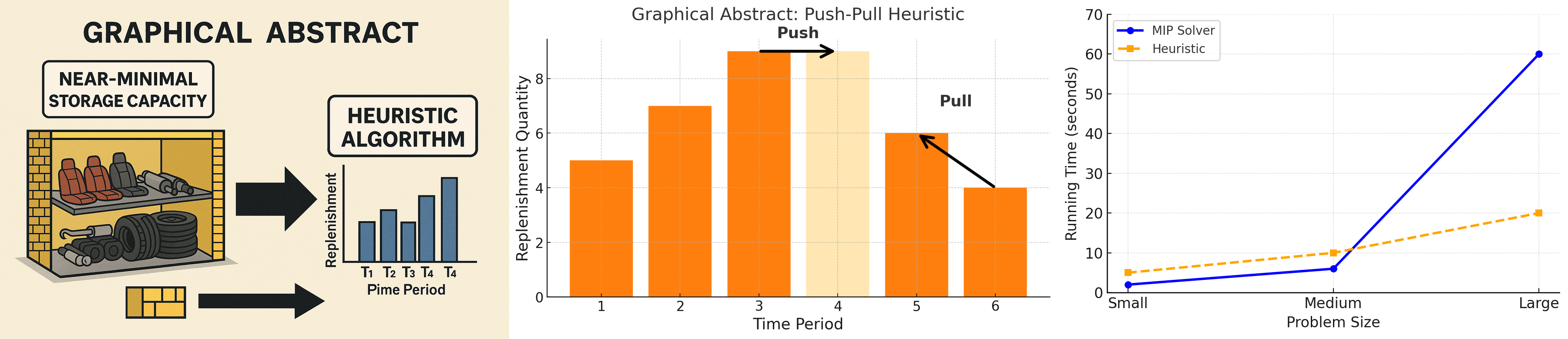

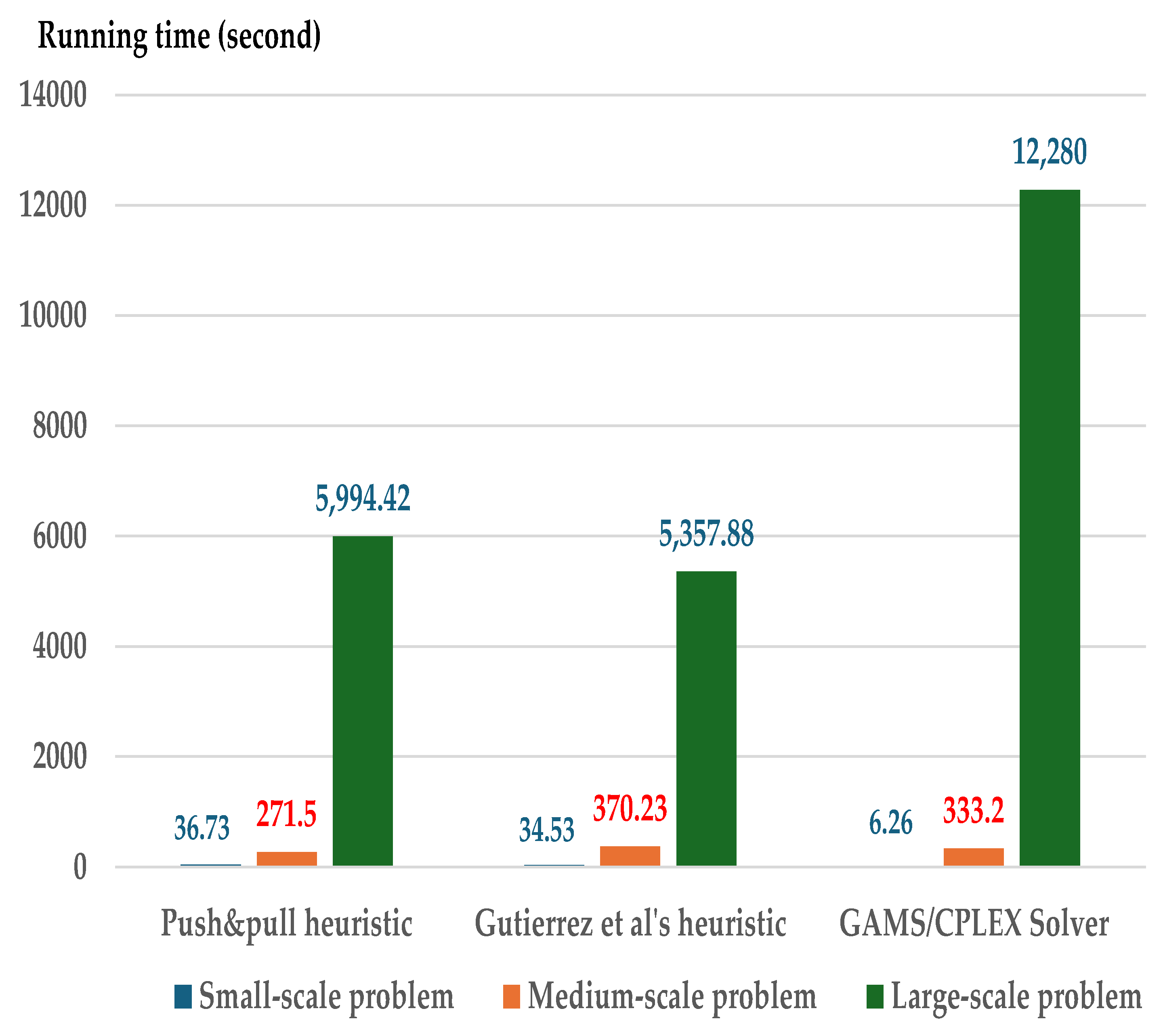

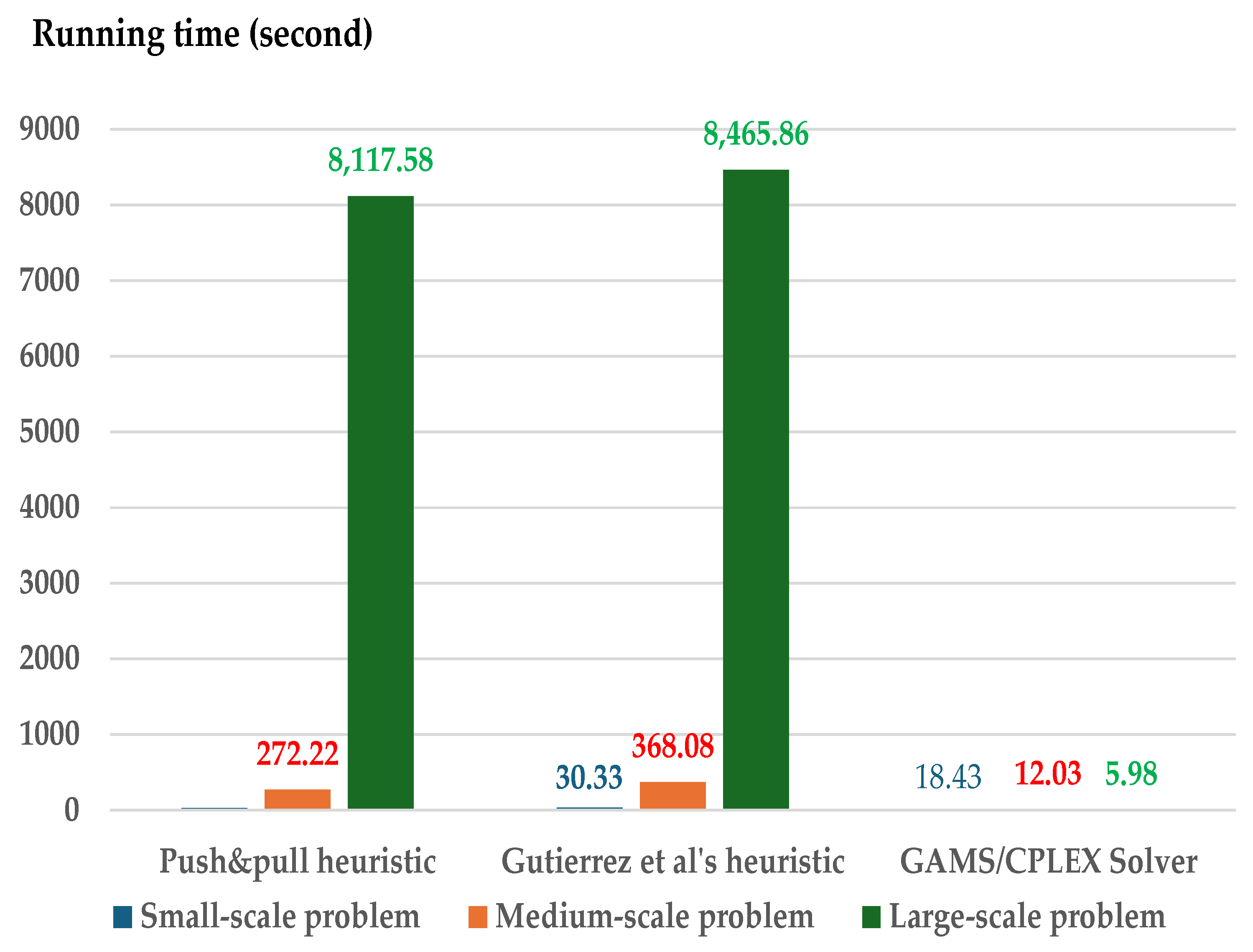

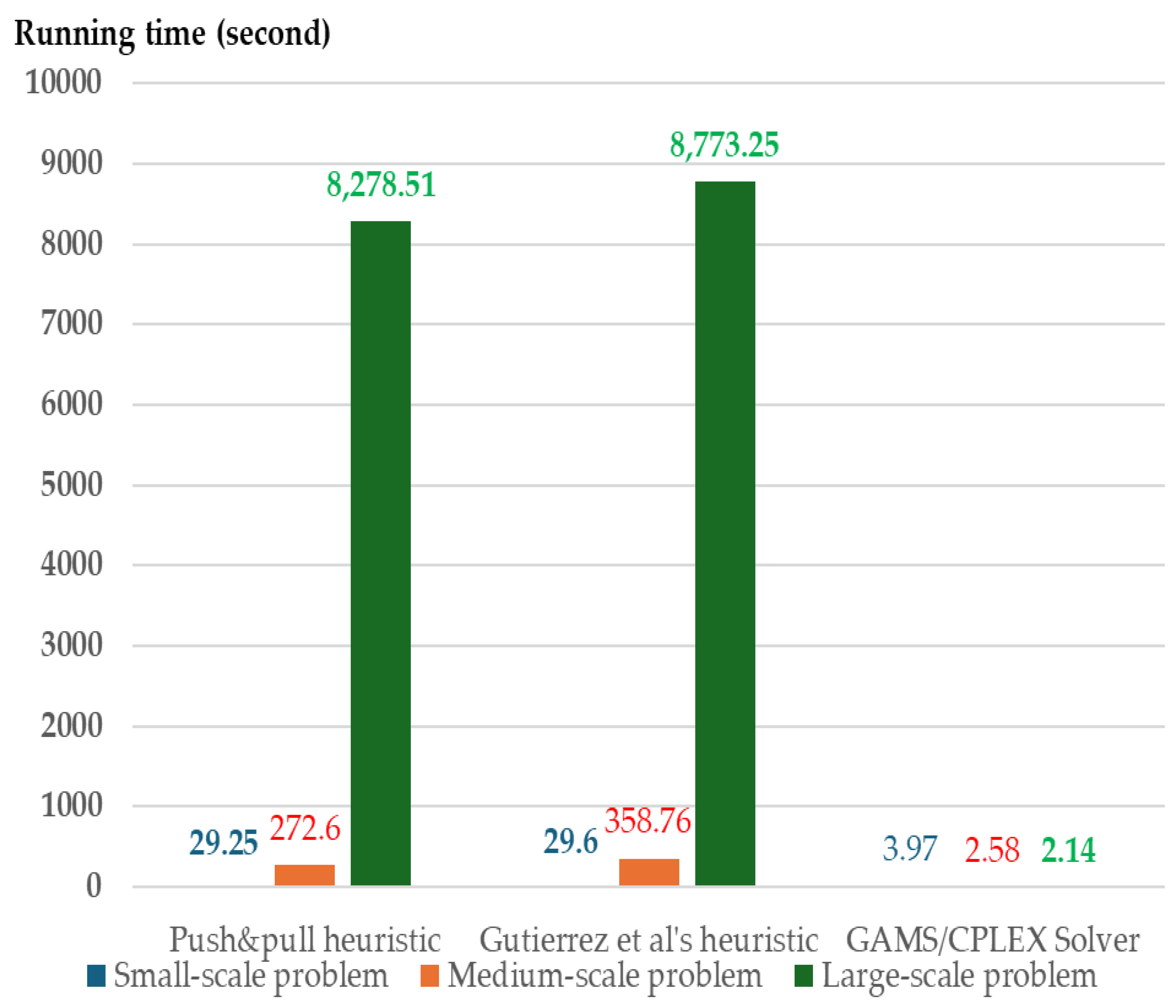

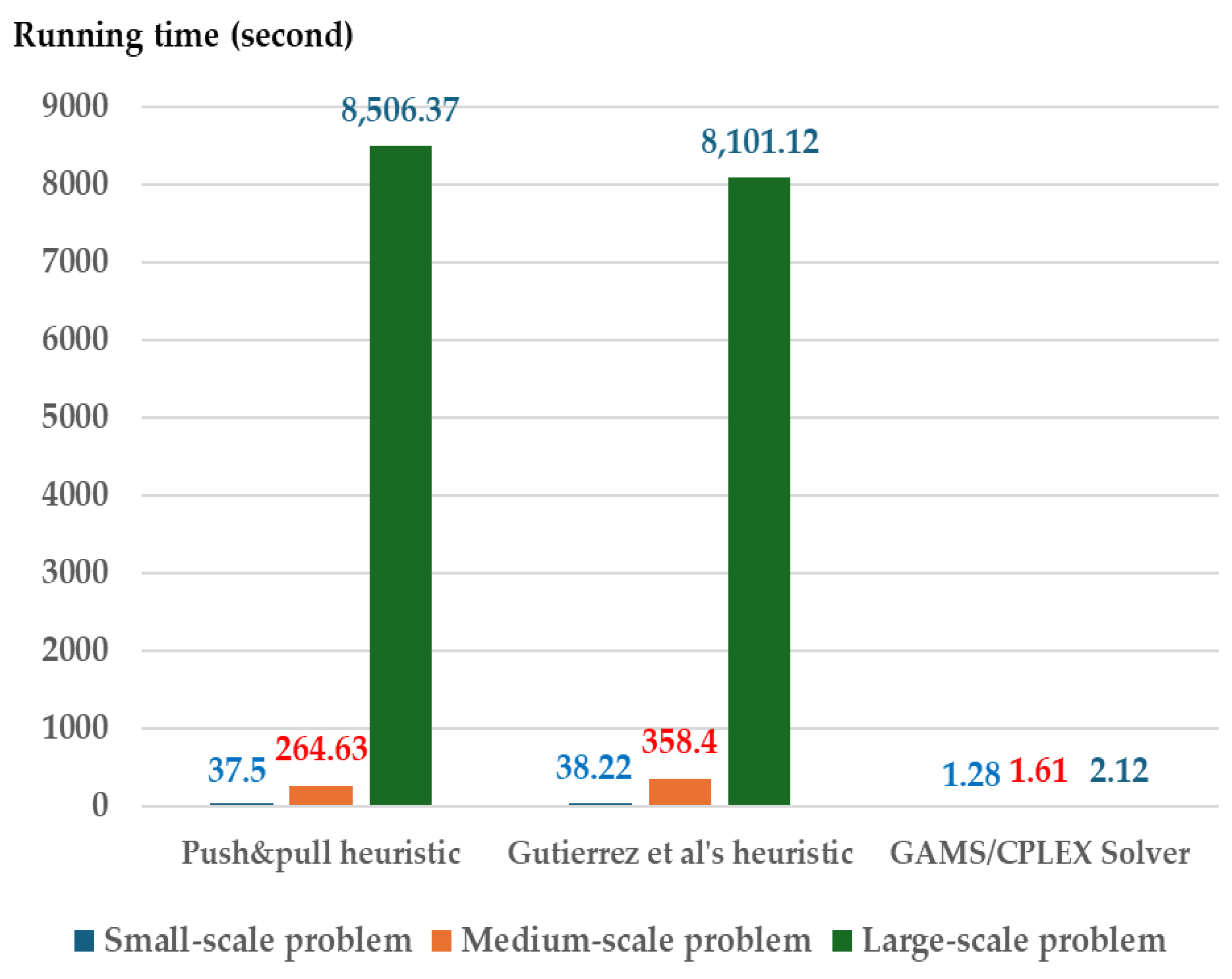

5.3. Computation Time

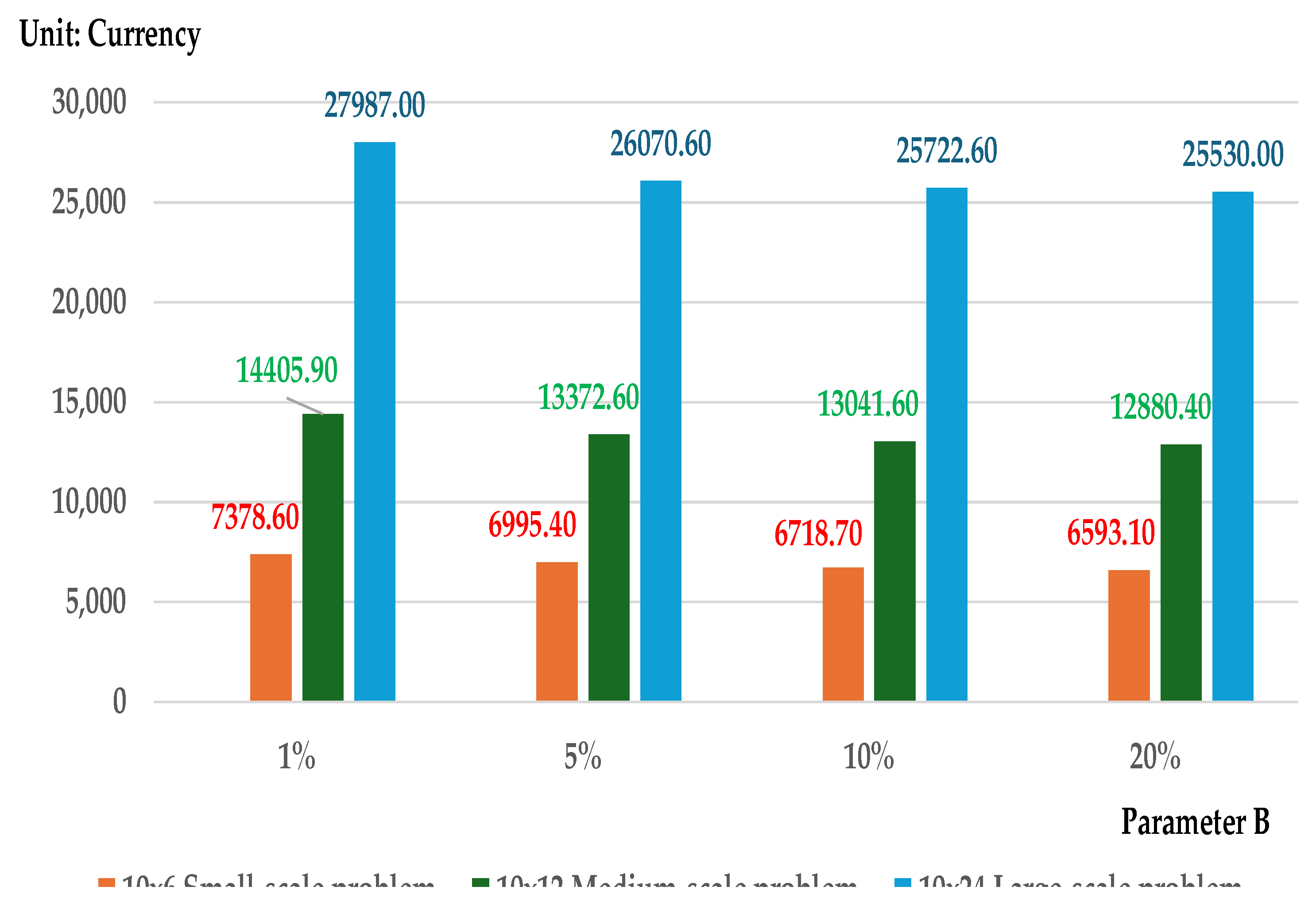

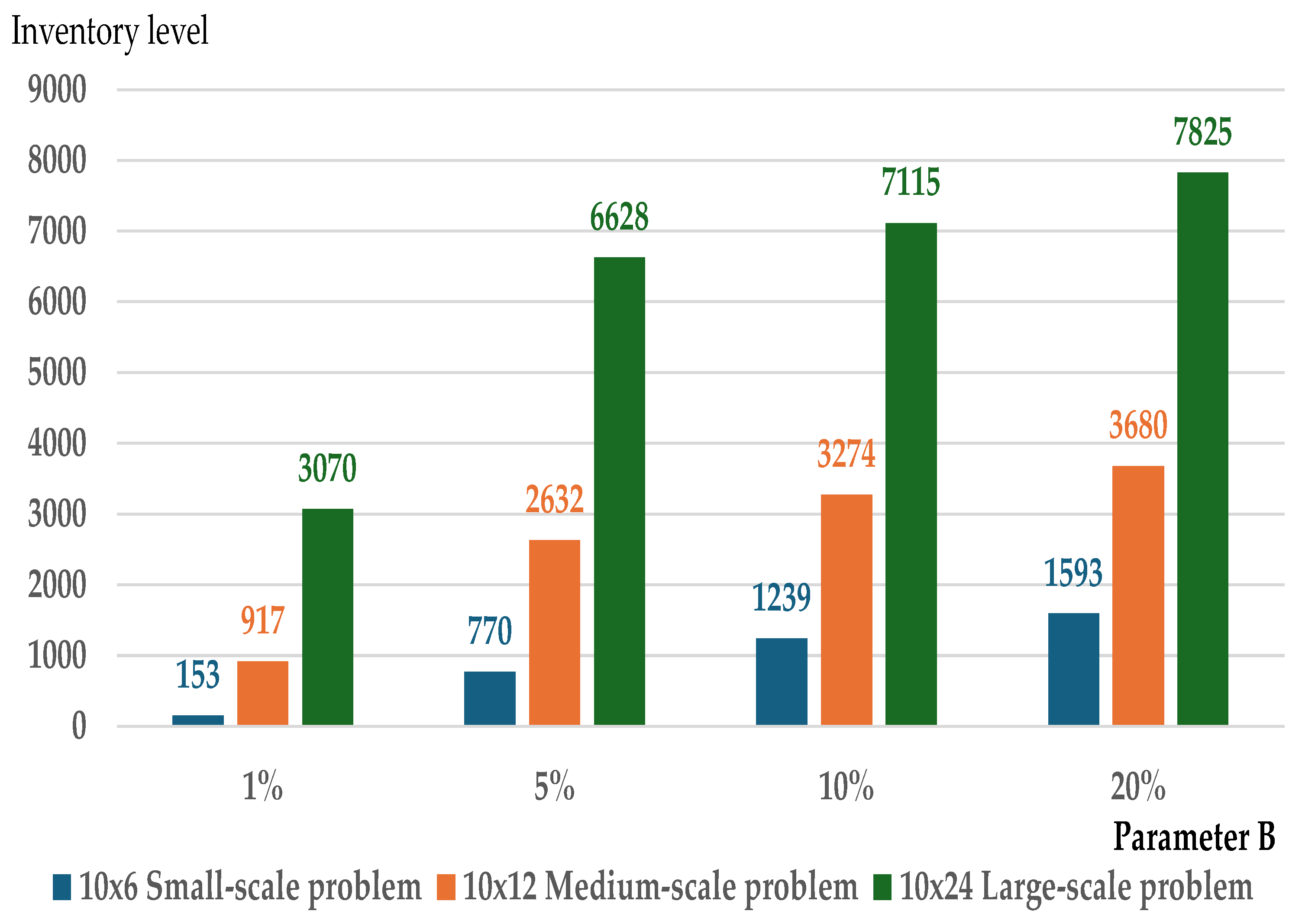

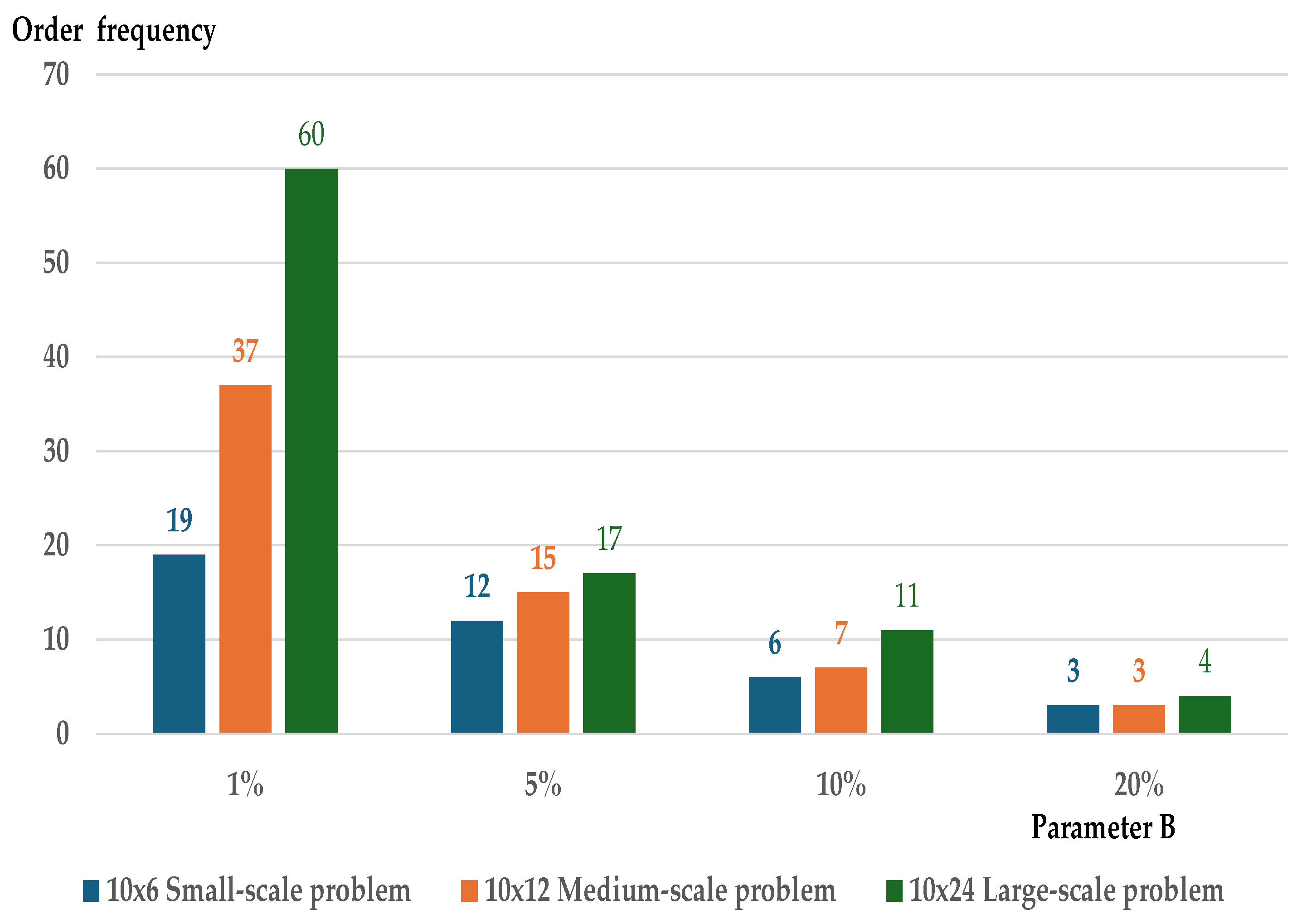

5.4. Sensitivity Analysis

5.5. Statistical Validation of Heuristic Stability and Reliability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Love, S.F. Bounded Production and Inventory Models with Piecewise Concave Costs. Manag. Sci. 1973, 20, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loparic, M.; Pochet, Y.; Wolsey, L.A. The Uncapacited Lot-Sizing Problem with Sales and Safety Stocks. Math. Program. 2001, 89, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamtürk, A.; Küçükyavuz, A. Lot Sizing with Inventory Bounds and Fixed Costs: Polyhedral Study and Computation. Oper. Res. 2005, 53, 711–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Liu, T. Stochastic Lot-Sizing Problem with Inventory-Bounds an Constant Order-Capacities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 1398–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, M.; Heuvel, W.V.D.; Liu, T. A Note on the Economic Lot Sizing Problem with Inventory Bounds. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 223, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Chu, F.; Zhong, F.; Yang, S. A Polynomial Algorithm for a Lot-Sizing Problem with Backlogging, Outsourcing, and Limited Inventory. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 64, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbalik, A.; Penz, B.; Rapine, C. Multi-Item Uncapacitated Lot Sizing Problem with Inventory Bounds. Optim. Lett. 2015, 9, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi1, N.; Absi, N.; Dauzère-Pérès, S.; and Kedad-Sidhoum, S. Models and Lagrangian Heuristics for a Two-Level Lot-Sizing Problem with Bounded Inventory. OR Spectrum. 2015, 37, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.A.; Ribeiro, C.C. Formulations and Heuristics for the Multi-Item Uncapacitated Lot-Sizing Problem with Inventory Bounds. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 55, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A. A Heuristic for the Multi-Level Capacitated Lot Sizing Problem with Inventory Constraints. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2019, 14, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Shegarian, E. A Mixed Integer Linear Programming Model for the Multi-Item Uncapacitated Lot-Sizing Problem: A case study in the trailer manufacturing industry. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedeno-Noda, A.; Gutierrez, J.; Abdul-Julbar, B.; Sicilia, J. An O (T log T) Algorithm for the Dynamic Lot Size Problem with Limited Storage and Linear Costs. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2004, 28, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tu, Y. Production Planning with Limited Inventory Capacity and Allow Stockout. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Chu, C. Single-Item Dynamic Lot-Sizing Models with Bounded Inventory and Outsourcing. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Hum. 2008, 38, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-C.; Heuvel, W.V.D. Improved Algorithms for a Lot-Sizing Problem with Inventory Bounds and Backlogging. Nav. Res. Logist. 2012, 59, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-C.; Heuvel, W.V.D.; Wagelmans, A.P.M. The Economic Lot- Sizing Problem with Lost Sales and Bounded Inventory. IIE Trans. 2013, 45, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Colebrook, M.; Abdul-Jalbar, B.; Sicilia, J. Effective Replenishment Policies for the Multi-Item Dynamic Lot- Sizing Problem with Storage Capacities. Comput. Oper. Res. 2013, 40, 2844–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minner, S. A Comparison of Simple Heuristics for Multi-Product Dynamic Demand Lot-Sizing with Limited Warehouse Capacity. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 118, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.M.; Whitin, T.M. Dynamic Version of the Economic Lot Size Model. Manag. Sci. 1958, 5, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Sedeño-Noda, A.; Colebrook, M.; Sicilia, J. A Polynomial Algorithm for the Production/Ordering Planning Problem with Limited Storage. Comput. Oper. Res. 2007, 34, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toczylowski, E. An O(T2) Algorithm for the Lot-Sizing Problem with Limited Inventory Levels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Paris, France, 10–13 October 1995; p. 78. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=496709&tag=1 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Ojeda, A. Multi-level production planning with raw-material perishability and inventory bounds. Ph.D. Thesis, (Industrial Engineering) of Concordia University, Montreal, Canada, September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boonphakdee, W.; Charnsethikul, P. Column Generation Approach for Solving Uncapacitated Dynamic Lot-Sizing Problems with Time-Varying Cost. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 2022, 23, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Summa, M.; Wolsey, L.A. Lot-Sizing with Stock Upper Bounds and Fixed Charges. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 2010, 24, 853–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.B. An Integrated Approach for Production and Distribution Planning in Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 1205–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emde, S. Sequencing Assembly Lines to Facilitate Synchronized Just-In-Time Part Supply. J. Sched. 2019, 22, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.S.; Poh, C.L. Heuristic Procedures for Multi-Item Inventory Planning with Limited Storage. IIE Trans. 1990, 22, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATLAB code for Heuristic for the multi-item lot-sizing with storage capacities. MATLAB Central File Exchange. Available online: https://www.math works.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/179289-heuristic-for-the-multi-item-lot-sizinng-with-storage-cap (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- MATLAB code for Heurictic of Gutierrez et al. 2013 algorithm. MATLAB Central File Exchange. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/179294-heurictic-of-gutierrez-et-al-2013-algorithm (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- MATLAB code for Smoothing Heuristic Multi-item Lot size with Storage cap. MATLAB CentralFile Exchange. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/181148-smoothing-heuristic-multi-item-lot-size-with-storage-cap (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- CPLEX solver. Available online: https://documentation.aimms.com/platform/solvers/cplex.html (accessed on 23 December 2024).

| References | Model. | Stor. | Algo. | Cap. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dixon and Poh[27] | I&P | BegInv. | DP.&Heu. | Limit.Inv. |

| Park[25] | I&P&R&V | EndInv. | LR.Heu. | Limit.Inv&P&R |

| Akbalik et al. [7] | I&P | EndInv. | DP. | Limit.Inv. |

| Gutiérrez et al. [17] | I&P | BegInv. | DP.&Heu. | Limit.Inv. |

| Melo and Ribeiro [9] | I&P&PT&V | EndInv. | LP.R.Heu.&Heu. | Limit.Inv. |

| Witt[10] | I&P | EndInv. | Heu. | Limit.Inv. |

| Periods t | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ut | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 |

| Item 1,w1=1 | |||||

| d1,t | 115 | 114 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| D1,t | 567 | 452 | 338 | 242 | 136 |

| f1,t | 595 | 100 | 969 | 240 | 945 |

| p1,t | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 4 |

| h1,t | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Item 2,w1=4 | |||||

| d2,,t | 87 | 52 | 111 | 142 | 118 |

| D2,t | 510 | 423 | 371 | 260 | 118 |

| f2,t | 255 | 696 | 125 | 637 | 249 |

| p2,t | 3 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 4 |

| h2,t | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Periods t Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 567 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 139 | 0 | 371 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inventory | 1 | 452 | 338 | 242 | 136 | 0 |

| 2 | 52 | 0 | 260 | 118 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 4x567+1x452+595 =3,315 |

338 | 242 | 136 | 0 |

| 2 | 3x139+1x52+255 =724 | 0 | 385 | 118 | 0 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) | 1 | 567x1=567 | 452 | 338 | 242 | 136 |

| 2 | 139x4=556 | 208 | 1,484 | 1,040 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 1,123 | 660 | 1,822 | 1,282 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | +367 | -13 | 1,189 | 524 | 0 | |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 567-136=431 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 136 |

| 2 | 139 | 0 | 371 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ending inventory |

1 | 316 | 202 | 106 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 52 | 0 | 260 | 118 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 4x431+1x316+595 =2,635 |

202 | 106 | 0 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 724 | 0 | 385 | 118 | 0 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 1x431=431 | 316 | 202 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 556 | 208 | 1,484 | 1,040 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 987 | 524 | 1,686 | 1,146 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | +231 | -149 | +1,053 | +388 | 0 |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 431 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 136 |

| 2 | 139-52 =87 |

52 | 371 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ending inventory |

1 | 316 | 202 | 106 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 260 | 118 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 2,635 | 202 | 106 | 0 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 3x87+255 =516 |

3x52+696 =852 |

3x371+1x260+125 =385 |

118 | 0 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 431 | 316 | 202 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 4x87=348 | 4x87=208 | 1,484 | 1,040 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 779 | 524 | 1,686 | 1,146 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | +23 | -149 | +1,053 | +388 | 0 |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 431-106=325 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 87 | 52 | 371 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ending inventory | 1 | 210 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 260 | 118 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 4x325+1x210+595 =2,105 |

96 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 516 | 852 | 385 | 118 | 0 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 325 | 210 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 348 | 208 | 1,484 | 1,040 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 673 | 418 | 1,580 | 1,146 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | -83 | -255 | +947 | +388 | 0 |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 87 | 52 | 371-118=253 | 0 | 118 | |

| Ending inventory | 1 | 210 | 96 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 142 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 2,105 | 96 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 516 | 852 | 1x142+125=267 | 0 | 721 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 325 | 210 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 348 | 208 | 4x253=1,012 | 568 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 673 | 418 | 1,108 | 674 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | -83 | -255 | +475 | -84 | 0 |

| Periods t Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan | 1 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 87 | 52 | 253-142=111 | 142 | 118 | |

| Ending inventory |

1 | 210 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 2,105 | 96 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 516 | 852 | 125 | 8x142+637 = 1,773 |

721 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 325 | 210 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 348 | 208 | 4x111=444 | 568 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 673 | 418 | 540 | 674 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | -83 | -255 | -93 | -84 | 0 | |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replenished plan |

1 | 325 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 87+52 =139 |

52-52 =0 |

111 | 142 | 118 | |

| Ending inventory |

1 | 210 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 2,105 | 96 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 3x139+1x52+255 = 724 |

0 | 125 | 1,773 | 721 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) | 1 | 1x325 =325 |

210 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 4x139 =556 |

208 | 444 | 568 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 881 | 418 | 540 | 674 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | +125 | -255 | -93 | -84 | 0 |

| Periods t | Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Replenished plan |

1 | 325-125 =200 |

0+125=125 | 0 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 139 | 0 | 111 | 142 | 118 | |

| Ending inventory |

1 | 85 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inventory cost | 1 | 4x200+1x85+595 =1,480 |

1,071 | 0 | 1,300 | 1,489 |

| 2 | 724 | 0 | 125 | 1,773 | 721 | |

| Sum of inventory and replenishment (SIR) |

1 | 1x200 =200 |

210 | 96 | 106 | 136 |

| 2 | 556 | 208 | 444 | 568 | 472 | |

| SIRallitems | 756 | 418 | 540 | 674 | 608 | |

| SC | 756 | 673 | 633 | 758 | 608 | |

| SIRallitems_U | 0 | -255 | -93 | -84 | 0 |

| Gutiérrez et al. [17] | Inventory cost | |||||||

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Item 1 | 200 | 125 | 0 | 106 | 136 | 5,340 | ||

| 2 | 139 | 0 | 111 | 142 | 118 | 3,343 | ||

| Total inventory cost | 8,683 | |||||||

| Nixon and Poh [27] | Inventory cost | |||||||

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Item 1 | 115 | 210 | 0 | 106 | 136 | 5,510 | ||

| 2 | 87 | 52 | 111 | 142 | 118 | 3,987 | ||

| Total inventory cost | 9,497 | |||||||

| Periods t | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ut | 1161 | 529 | 768 | 973 | 721 | 806 |

| Item 1,w1=2 | ||||||

| d1,t | 44 | 47 | 64 | 67 | 67 | 9 |

| f1 | 96 | |||||

| p1 | 6 | |||||

| h1 | 1 | |||||

| Item 2,w2=5 | ||||||

| d2,,t | 83 | 21 | 36 | 87 | 70 | 88 |

| f2 | 74 | |||||

| p2 | 10 | |||||

| h2 | 1 | |||||

| Item 3,w1=4 | ||||||

| d,3,t | 88 | 12 | 58 | 65 | 39 | 87 |

| f3 | 67 | |||||

| p3 | 9 | |||||

| h3 | 1 | |||||

| Heuristics/MIP solver | GAMS/ CPLEX |

Push and Pull | Gutiérrez et al. [17] | Smoothing [27] |

| Total cost | 9,928 | 9,928 | 10,054 | 10,030 |

| % Gap solution | - | 0 | 1.27 | 1.02 |

| No. of additional orders |

- | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of periods, T | 6 | 12 | 24 |

| Number of items, N | 10,20,40,60,80,…,160 | 10,20,30,…,80 | 10,20,…,160 |

| Number of instances | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| Weight distribution, | Uniform, | ||

| Demand distribution, | Uniform, | ||

| Ordering cost distribution, | Uniform, | ||

| Inventory bounds, Ut |

, B = {1%,5%,10%, 20%} |

||

| Cost of procuring raw materials, pi,t = zero and holding cost, hi,t = 1 | |||

| NxT | Avg. Push & pull heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. Gutiérrez’s heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. GAMS/CPLEX time (s.) | Min. gap (%) | Max. gap (%) | Avg. gap (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push & pull heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | ||||

| 10x6 | 6.26 | 6.24 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 2.77 | 3.78 | 0.57 | 1.89 |

| 20x6 | 6 | 11.45 | 11.16 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 1.03 | 5.29 | 8.30 | 1.04 |

| 40x6 | 21.90 | 21.24 | 2.56 | 0.28 | 2.87 | 0.88 | 5.02 | 0.72 | 3.48 |

| 60x6 | 32.48 | 30.99 | 5.31 | 0.44 | 2.24 | 1.05 | 4.53 | 0.82 | 3.57 |

| 80x6 | 44.25 | 41.81 | 7.27 | 0.67 | 2.65 | 1.13 | 4.47 | 0.91 | 3.44 |

| 100x6 | 56.24 | 51.91 | 11.92 | 0.47 | 3.14 | 1.17 | 4.99 | 0.92 | 3.82 |

| 120x6 | 69.42 | 60.82 | 12.28 | 0.55 | 2.90 | 1.15 | 4.60 | 0.89 | 3.64 |

| 140x6 | 84.99 | 71.33 | 15.84 | 0.52 | 3.03 | 1.76 | 5.05 | 0.94 | 4.07 |

| 160x6 | 100.72 | 81.98 | 57.13 | 0.04 | 2.98 | 8.51 | 11.90 | 2.08 | 5.09 |

| 36.73 | 34.53 | 6.26 | 1.16 | 3.99 | |||||

| 10x12 | 61.85 | 64.78 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 2.54 | 1.32 | 7.27 | 0.79 | 5.36 |

| 20x12 | 131.74 | 140.63 | 3.67 | 0.73 | 2.44 | 1.68 | 7.31 | 1.23 | 4.53 |

| 30x12 | 204.64 | 216.34 | 8.57 | 1.24 | 4.21 | 1.93 | 7.17 | 1.51 | 5.66 |

| 40x12 | 260.38 | 273.55 | 39.66 | 1.08 | 4.14 | 1.89 | 7.85 | 1.42 | 5.54 |

| 50x12 | 328.35 | 321.77 | 74.41 | 1.15 | 4.89 | 1.77 | 6.64 | 1.39 | 5.71 |

| 60x12 | 409.28 | 458.70 | 102.65 | 1.18 | 4.98 | 1.90 | 6.16 | 1.39 | 5.65 |

| 70x12 | 495.31 | 679.99 | 380.50 | 0.23 | 4.97 | 1.46 | 6.77 | 1.24 | 5.61 |

| 80x12 | 520.24 | 537.58 | 2388.1 | 1.21 | 4.22 | 1.48 | 6.56 | 1.30 | 5.67 |

| 271.5 | 370.23 | 333.20 | 1.33 | 5.57 | |||||

| 10x24 | 3,037.37 | 3,429.14 | 2.31 | 0.95 | 6.04** | 1.58 | 7.73** | 1.27 | 6.89** |

| 20x24 | 6,507.96 | 5,765.73 | 59.68 | 1.58 | 7.16* | 2.20 | 7.16* | 1.83 | 7.16* |

| 30x24 | 7,303.46 | 8,694.35 | 3,549.2 | 1.11 | 7.42* | 2.21 | 7.42 | 1.84 | 7.42* |

| 40x24 | 12,903.55 | 13,484.40 | 57,788.2 | 0.91 | 7.49* | 2.07 | 7.49* | 1.54 | 7.49* |

| 5,994.42 | 5,357.88 | 12,280 | 1.66 | 7.30 | |||||

| NxT | Avg. Push & pull heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. Gutiérrez’s heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. GAMS/CPLEX time (s.) | Min. gap (%) | Max. gap (%) | Avg. gap (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push & pull heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | ||||

| 10x6 | 5.65 | 5.67 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 3.33 | 6.54 | 1.39 | 3.96 |

| 20x6 | 9.77 | 10.36 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.66 | 2.35 | 9.30 | 1.59 | 5.33 |

| 40x6 | 21.41 | 23.14 | 5.91 | 1.23 | 3.27 | 2.23 | 8.20 | 1.72 | 6.46 |

| 60x6 | 29 | 31.99 | 10.34 | 1.00 | 5.13 | 2.32 | 9.23 | 1.73 | 7.31 |

| 80x6 | 35.13 | 36.28 | 27.42 | 1.00 | 3.98 | 2.59 | 8.53 | 1.76 | 6.88 |

| 100x6 | 44.65 | 46.03 | 33.74 | 0.92 | 5.84 | 1.80 | 8.29 | 1.60 | 6.83 |

| 120x6 | 53.20 | 54.55 | 29.79 | 1.48 | 5.53 | 2.11 | 7.68 | 1.58 | 6.71 |

| 140x6 | 63.23 | 64.96 | 57.33 | 0.92 | 4.89 | 1.85 | 6.95 | 1.53 | 6.23 |

| 160x6 | 72.58 | 76.85 | 33.79 | 0.98 | 5.48 | 2.88 | 8.21 | 1.70 | 6.29 |

| 29.11 | 30.33 | 18.43 | 1.64 | 6.56 | |||||

| 10x12 | 71.52 | 62.86 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 2.49 | 12.53 | 1.47 | 7.01 |

| 20x12 | 142.7 | 132.49 | 2.33 | 0.73 | 2.18 | 1.62 | 7.89 | 1.21 | 4.69 |

| 30x12 | 189.3 | 213.94 | 3.90 | 0.65 | 1.50 | 1.35 | 7.76 | 1.02 | 4.91 |

| 40x12 | 254.2 | 256.25 | 7.00 | 0.63 | 2.90 | 1.23 | 6.24 | 0.93 | 4.38 |

| 50x12 | 319.9 | 339.75 | 14.92 | 0.64 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 5.38 | 0.88 | 3.96 |

| 60x12 | 417.6 | 422.97 | 18.73 | 0.66 | 2.91 | 1.27 | 5.62 | 0.93 | 4.30 |

| 70x12 | 498.1 | 526.02 | 36.40 | 0.69 | 2.99 | 1.18 | 5.36 | 0.87 | 3.94 |

| 80x12 | 523.7 | 519.15 | 24.03 | 0.67 | 2.11 | 1.15 | 6.65 | 0.82 | 4.01 |

| 272.22 | 368.08 | 12.03 | 0.92 | 4.43 | |||||

| 10x24 | 1,398.7 | 1,578.05 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 1.68 | 1.68 | 5.01 | 0.94 | 3.19 |

| 20x24 | 6,592.9 | 7,140.05 | 6.22 | 0.31 | 1.62 | 0.79 | 3.08 | 0.59 | 2.48 |

| 30x24 | 9,608.8 | 9,364.59 | 47.16 | 0.24 | 1.06 | 0.80 | 2.46 | 0.58 | 1.95 |

| 40x24 | 12,824.7 | 13,504.5 | 61.94 | 0.22 | 1.91 | 0.58 | 3.07 | 0.40 | 2.60 |

| 8,117.58 | 8,465.86 | 5.98 | 0.55 | 2.41 | |||||

| NxT | Avg. Push & pull heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. Gutiérrez’s heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. GAMS/CPLEX time (s.) | Min. gap (%) | Max. gap (%) | Avg. gap (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push & pull heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | ||||

| 10x6 | 5.83 | 5.64 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.71 | 12.28 | 0.84 | 4.93 |

| 20x6 | 10.10 | 10.19 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 1.62 | 13.44 | 1.11 | 5.00 |

| 40x6 | 20.40 | 22.22 | 2.35 | 0.51 | 2.29 | 2.16 | 6.55 | 1.12 | 4.66 |

| 60x6 | 29.51 | 28.04 | 2.04 | 0.54 | 2.12 | 1.88 | 7.13 | 1.10 | 3.97 |

| 80x6 | 35.23 | 36.34 | 4.82 | 0.50 | 2.55 | 1.55 | 5.87 | 1.01 | 4.30 |

| 100x6 | 44.68 | 45.50 | 7.19 | 0.48 | 2.00 | 1.28 | 6.22 | 0.87 | 4.06 |

| 120x6 | 54.61 | 54.74 | 11.24 | 0.63 | 2.19 | 4.05 | 5.38 | 1.12 | 4.06 |

| 140x6 | 62.91 | 63.74 | 7.35 | 0.58 | 2.65 | 1.06 | 5.10 | 0.80 | 3.40 |

| 160x6 | 73.68 | 73.68 | 7.30 | 0.56 | 2.45 | 2.04 | 5.25 | 0.96 | 3.63 |

| 29.25 | 29.6 | 3.97 | 0.93 | 3.92 | |||||

| 10x12 | 66.41 | 62.41 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 1.74 | 4.26 | 0.74 | 1.74 |

| 20x12 | 141.27 | 132.11 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 4.26 | 0.57 | 1.58 |

| 30x12 | 187.59 | 210.50 | 1.25 | 0.39 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 3.27 | 0.59 | 1.86 |

| 40x12 | 264.08 | 256.14 | 2.23 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 2.32 | 0.48 | 1.42 |

| 50x12 | 325.22 | 317.78 | 2.91 | 0.26 | 1.02 | 0.64 | 2.92 | 0.46 | 1.67 |

| 60x12 | 414.79 | 408.41 | 3.13 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.63 | 3.22 | 0.47 | 2.01 |

| 70x12 | 496.28 | 495.38 | 5.75 | 0.31 | 1.43 | 0.77 | 2.73 | 0.48 | 1.98 |

| 80x12 | 517.69 | 524.16 | 6.43 | 0.32 | 1.41 | 0.61 | 2.33 | 0.45 | 1.85 |

| 272.6 | 358.76 | 2.58 | 0.49 | 1.81 | |||||

| 10x24 | 3,177.71 | 3,508.17 | 0.53 | 1.60 | 1.08 | 2.52 | 2.65 | 0.56 | 1.74 |

| 20x24 | 6,924.87 | 7,841.10 | 1.72 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 1.90 | 1.74 | 0.45 | 1.15 |

| 30x24 | 9,188.50 | 9,681.13 | 2.38 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 1.82 | 0.31 | 1.10 |

| 40x24 | 13,527.06 | 13,764.70 | 3.32 | 0.16 | 1.03 | 0.65 | 1.78 | 0.34 | 1.24 |

| 8,278.51 | 8,773.25 | 2.14 | 0.38 | 1.23 | |||||

| NxT | Avg. Push & pull heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. Gutiérrez’s heuristic time (s.) |

Avg. GAMS/CPLEX time (s.) | Min. gap (%) | Max. gap (%) | Avg. gap (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push & pull heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | Pull & push heuristic | Gutiérrez ’s heuristic | ||||

| 10x6 | 5.85 | 5.71 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 2.50 | 4.83 | 0.83 | 2.48 |

| 20x6 | 10.02 | 10.25 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.51 | 2.18 | 0.68 | 1.18 |

| 40x6 | 22.22 | 22.94 | 1.74 | 0.26 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 2.40 | 0.57 | 1.76 |

| 60x6 | 29.54 | 29.66 | 0.87 | 0.20 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 2.34 | 0.60 | 1.75 |

| 80x6 | 35.24 | 35.71 | 0.90 | 0.44 | 1.18 | 1.03 | 2.17 | 0.62 | 1.71 |

| 100x6 | 45.18 | 45.34 | 2.02 | 0.31 | 1.14 | 0.84 | 2.07 | 0.61 | 1.71 |

| 120x6 | 53.90 | 55.09 | 1.87 | 0.36 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 1.53 | 0.65 | 1.72 |

| 140x6 | 62.99 | 64.38 | 1.66 | 0.47 | 1.67 | 0.92 | 2.75 | 0.67 | 1.97 |

| 160x6 | 73.13 | 74.91 | 1.81 | 0.35 | 1.53 | 1.66 | 2.82 | 0.76 | 1.87 |

| 37.56 | 38.22 | 1.28 | 0.66 | 1.79 | |||||

| 10x12 | 36.14 | 32.01 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 2.34 | 0.39 | 0.65 |

| 20x12 | 71.55 | 62.07 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 1.65 | 0.34 | 0.91 |

| 30x12 | 185.60 | 205.13 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 1.42 | 0.37 | 0.87 |

| 40x12 | 264.97 | 258.89 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 1.24 | 0.36 | 0.92 |

| 50x12 | 330.85 | 322.59 | 1.20 | 0.19 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 2.38 | 0.35 | 1.03 |

| 60x12 | 491.05 | 501.27 | 3.97 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 1.30 | 0.33 | 0.94 |

| 70x12 | 491.05 | 501.27 | 3.97 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 1.30 | 0.33 | 0.94 |

| 80x12 | 515.24 | 541.88 | 2.10 | 0.25 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 1.16 | 0.34 | 0.84 |

| 264.63 | 358.40 | 1.61 | 0.36 | 0.87 | |||||

| 10x24 | 3,018.94 | 3,196.81 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 1.64 | 1.07 | 0.34 | 0.60 |

| 20x24 | 7,084.67 | 6,422.94 | 1.14 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 2.41 | 0.73 | 0.28 | 0.47 |

| 30x24 | 9,889.41 | 9,612.80 | 1.40 | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.57 |

| 40x24 | 13,706.49 | 12,863.77 | 1.78 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.56 |

| 8,506.37 | 8,101.12 | 2.12 | 0.27 | 0.55 | |||||

| Parameter B | The push and pull heuristic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem size | 10X6 small-scale problem |

10X12 medium- scale problem |

10X24 large-scale problem |

|

| 1% | Avg. | 0.57 | 0.79 | 1.27 |

| Max. | 0.73 | 1.32 | 1.58 | |

| 5% | Avg. | 1.39 | 1.47 | 0.94 |

| Max. | 2.62 | 2.49 | 1.27 | |

| 10% | Avg. | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.56 |

| Max. | 1.81 | 1.74 | 1.2 | |

| 20% | Avg. | 1.84 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Max. | 2.5 | 0.88 | 1.64 | |

| Gutiérrez et al.’s heuristic | ||||

| 1% | Avg. | 1.89 | 5.36 | 6.89 |

| Max. | 3.51 | 7.27 | 7.73 | |

| 5% | Avg. | 3.96 | 7 | 0.94 |

| Max. | 6.54 | 11.84 | 1.04 | |

| 10% | Avg. | 4.92 | 1.74 | 1.74 |

| Max. | 12.28 | 4.26 | 2.65 | |

| 20% | Avg. | 2.48 | 0.65 | 0.6 |

| Max. | 4.83 | 2.34 | 1.07 | |

| Smoothing heuristic [27] | ||||

| 1% | Avg. | 1.89 | 4.24 | 5.97 |

| Max. | 3.4 | 6.24 | 6.79 | |

| 5% | Avg. | 3.96 | 4.68 | 2.3 |

| Max. | 6.54 | 7.53 | 2.46 | |

| 10% | Avg. | 4.13 | 2.04 | 2.8 |

| Max. | 9.83 | 3.51 | 8.46 | |

| 20% | Avg. | 1.7 | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| Max. | 3.35 | 1.53 | 1.35 | |

| Problem |

Average (currency) |

Standard deviation | Lower confidence interval(a) | Upper confidence interval(a) | Min. total cost | Max. total cost |

| 10x6 | 7378.6 | 158.1 | 6904.4 | 7852.7 | 7114 | 7640 |

| 20x6 | 14570 | 261.2 | 13786.2 | 15353.79 | 14200 | 15081 |

| 40x6 | 29012.2 | 340.2 | 27991.6 | 30032.8 | 28409 | 29498 |

| 60x6 | 43445 | 400.0 | 42244.9 | 44645.1 | 42930 | 43941 |

| 80x6 | 58025.2 | 544.1 | 56393.1 | 59657.3 | 57059 | 58883 |

| 100x6 | 72482.8 | 565.9 | 70784.9 | 74180.6 | 71498 | 73354 |

| 120x6 | 86833 | 607.5 | 85010.5 | 88655.5 | 85551 | 87392 |

| 140x6 | 101220.8 | 645.9 | 99282.9 | 103158.7 | 99805 | 101875 |

| 160x6 | 115562.2 | 710.6 | 113430.5 | 117693.9 | 114175 | 116367 |

| 10x12 | 14405.9 | 184.0 | 13853.8 | 14957.9 | 14160 | 14742 |

| 20x12 | 28599.9 | 232.3 | 27902.9 | 29296.9 | 28134 | 28871 |

| 30x12 | 42776.4 | 329.6 | 41787.7 | 43765.1 | 42106 | 43239 |

| 40x12 | 56862.5 | 365.5 | 55765.9 | 57959.1 | 56166 | 57551 |

| 50x12 | 70941.3 | 335.1 | 69936.1 | 71946.5 | 70393 | 71384 |

| 60x12 | 85055.2 | 584.1 | 83302.9 | 86807.5 | 83928 | 85927 |

| 70x12 | 99057.1 | 546.9 | 97416.1 | 100698.1 | 97851 | 99605 |

| 80x12 | 113184.8 | 514.6 | 111641.1 | 114728.5 | 112018 | 114040 |

| 10x24 | 27987 | 335.1 | 26981.6 | 28992.4 | 27722 | 28410 |

| 20x24 | 55547.6 | 460.6 | 54165.7 | 56929.5 | 54820 | 56051 |

| 30x24 | 82909 | 476.8 | 81478.7 | 84339.3 | 82590 | 83730 |

| 40x24 | 110034.8 | 762.3 | 107748.0 | 112321.6 | 108971 | 111105 |

| Problem |

Average (second) |

Standard deviation |

Lower confidence interval(a) | Upper confidence interval(a) | Min. total cost | Max. total cost |

| 10x6 | 6.25 | 0.54 | 4.63 | 7.88 | 5.79 | 7.59 |

| 20x6 | 11.45 | 0.31 | 10.53 | 12.38 | 11.04 | 12.02 |

| 40x6 | 21.90 | 0.37 | 20.78 | 23.04 | 21.37 | 22.54 |

| 60x6 | 32.48 | 0.46 | 31.09 | 33.87 | 31.75 | 33.17 |

| 80x6 | 44.25 | 0.93 | 41.45 | 47.05 | 43.04 | 45.86 |

| 100x6 | 56.24 | 0.94 | 53.43 | 59.05 | 55.02 | 57.71 |

| 120x6 | 69.42 | 1.26 | 65.65 | 73.18 | 67.90 | 71.21 |

| 140x6 | 84.98 | 2.49 | 77.52 | 92.46 | 82.41 | 91.25 |

| 160x6 | 100.72 | 1.46 | 96.35 | 105.09 | 98.57 | 103.74 |

| 10x12 | 61.85 | 5.27 | 46.03 | 77.68 | 55.48 | 71.94 |

| 20x12 | 131.74 | 4.84 | 117.23 | 146.26 | 126.34 | 141.33 |

| 30x12 | 204.63 | 16.03 | 156.53 | 252.74 | 182.15 | 236.27 |

| 40x12 | 260.38 | 23.67 | 189.36 | 331.41 | 229.37 | 311.10 |

| 50x12 | 328.35 | 34.155 | 225.89 | 430.82 | 279.38 | 402.51 |

| 60x12 | 409.28 | 40.99 | 286.31 | 532.24 | 351.43 | 492.47 |

| 70x12 | 495.31 | 40.97 | 372.41 | 618.22 | 443.17 | 585.65 |

| 80x12 | 520.24 | 26.18 | 441.69 | 598.79 | 478.54 | 566.50 |

| 10x24 | 3257.11 | 608.49 | 1431.63 | 5082.59 | 2647.19 | 4108.03 |

| 20x24 | 6507.96 | 340.99 | 5485 | 7530.92 | 6159.20 | 6964.99 |

| 30x24 | 9103.45 | 416.01 | 7855.43 | 10351.48 | 8471.77 | 9610.50 |

| 40x24 | 14628.15 | 1370.03 | 10518.05 | 18738.25 | 11694.79 | 14786.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).