1. Introduction

Cell junctions are specialized structures located at specific domains of the cell membrane, consisting of gap junctions (GJs), tight junctions, adherence junctions and desmosomes, allowing cells to survive and proliferate. These junctions control key processes in multicellular development, including cell-to-cell communication, cell communication with the extracellular environment, tissue integrity and homeostasis and acting as a site for protein-protein interaction to regulate signaling pathways

[1]. In order to carry out these functions, cell junction dynamically reorganize their structure to respond to the needs of cells. Although the main mechanism regulating the architecture and functioning of cell junction has been thoroughly examined through cell junctions imaging of immunofluorescence staining

[2,3] or electrochemiluminescence (ECL) microscopy

[4], these technological tools are inherently limited in their performance. For instance, immunofluorescence staining is susceptible to non-specific binding signal or intense background fluorescent signal

[5] and production of the antibodies is costly and laborious. A major limitation in the development of ECL microscopy is the dramatic decrease in the ECL signal observed when recording successive ECL images

[6]. Hence, the establishment of a simplistic, petite molecule to track cell junction behaviors is imperative to understand the intricacies of cell junctions and their regulatory mechanism.

Tight junctions are the most apical of the cell junctions. They consist of transmembrane proteins called claudins and occludins interacting with cytoplasmic proteins like the zonula occludens (ZO) protein ZO-1. Indeed, the ZO-1 antibody can be used for the immunostaining of cell-cell junctions

[7], but immunofluorescence staining has the limitations described above. The ZO-1 protein contains three PDZ domains, which are modular protein-binding motifs found in various organisms and play a crucial role in scaffolding protein complexes. The second PDZ domain (PDZ2) binds to the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of connexins and crystal structure of PDZ2 domain revealed the reconstitution of peptide-binding groove

[8].Therefore, we choose connexins to analyze the ZO-1-binding peptide for recognition unit of labeling cell junction. Connexin 43 (Cx43) is a specific connexin protein and widely expressed in various tissues and organs, including the heart, brain, and skin. The C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 has been shown to interact with PDZ2 domain of ZO-1. The specific residues involved in the interaction between Cx43 and PDZ2 vary among different connexins, but they generally include a conserved ASSR/K sequence. Based on the structural basis of the interaction between ZO-1 and Cx43, we aimed to create a fluorescent peptide derived from Cx43 and delivered it into cells through a strategy involving a cell-penetrating peptide.

2. Results

2.1. Design of a Cx43-derived tridecapeptide for monitoring cell junction

PDZ domains are protein interacting modules that attach to brief peptide fragments of target proteins in eukaryotic proteomes

[9–11]. Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) is a tight junction protein that plays a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of tight junctions

[12,13]. Jia Chen

et al[8] discussed the domain-swapped dimerization of ZO-1 PDZ2 and its role in generating specific and regulatory connexin43 (Cx43)-binding sites. Based on the finding, we firstly analyzed the carboxyl tail region of Cx43 and the PDZ2 domain of ZO-1 by docking using a molecular docking procedure GalaxyWEB

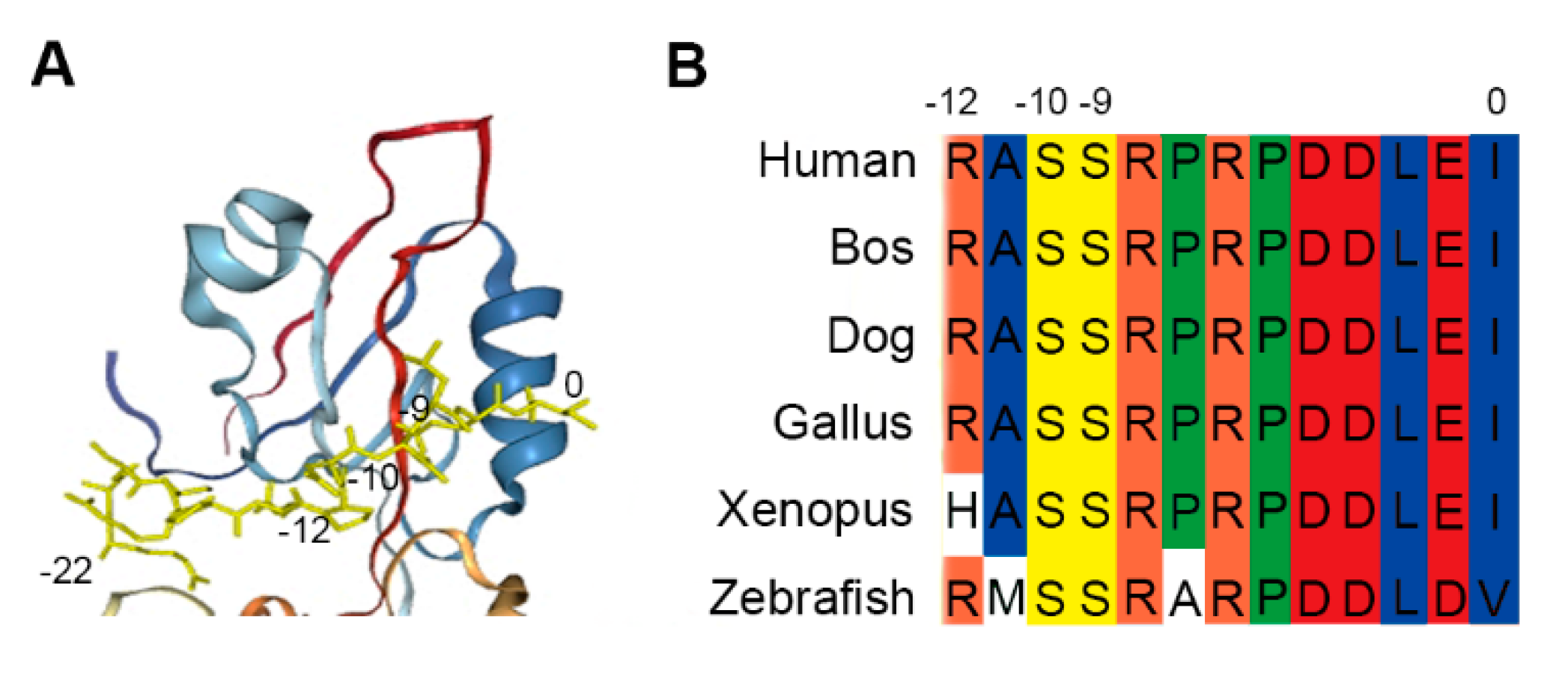

(https://galaxy.seoklab.org/index.html). The result showed that the PDZ domain-swapped assembly creates a symmetric pocket binding to the canonical carboxyl tail (-22 ~ 0, the last twenty-three residues) of Cx43 (Figure 1A). Besides, the Cx43/ZO-1 complex can be further regulated by the phosphorylations of Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) in Cx43

[8], as Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) are substrates of various kinases, such as PKC and Akt

[14-16]. Here, we extended the Cx43 peptide by two residues (-12 ~ 0, the last thirteen residues). The tridecapeptide fragments are highly conserved in different species (Figure 1B) and further confirmed that the peptide can be used as recognition unit of ZO-1 for labeling cell junction, which is just as the 17 conserved amino acids act as recognition units of F-actin for labeling microfilament

[17,18].

Figure 1.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide. (A) The conformational image represents the docking analysis between the last twenty-three residues (-22 ~ 0) from carboxyl tail region (yellow) of Cx43 and the PDZ domain protein of ZO-1. The final three residues of the Cx43 peptide attach to the groove and Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) intimately interact with the pocket. (B) Amino-acid sequence alignment of the C-terminal tail (-12 ~ 0) of Cx43 from different species. Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) of Cx43 are highly conserved and regulate the Cx43/ZO-1 complex. To guarantee binding, the Cx43 peptide was elongated by two residues. This peptide is known as the recognition unit of ZO-1 for labeling cell junction.

Figure 1.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide. (A) The conformational image represents the docking analysis between the last twenty-three residues (-22 ~ 0) from carboxyl tail region (yellow) of Cx43 and the PDZ domain protein of ZO-1. The final three residues of the Cx43 peptide attach to the groove and Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) intimately interact with the pocket. (B) Amino-acid sequence alignment of the C-terminal tail (-12 ~ 0) of Cx43 from different species. Ser (-9) and Ser (-10) of Cx43 are highly conserved and regulate the Cx43/ZO-1 complex. To guarantee binding, the Cx43 peptide was elongated by two residues. This peptide is known as the recognition unit of ZO-1 for labeling cell junction.

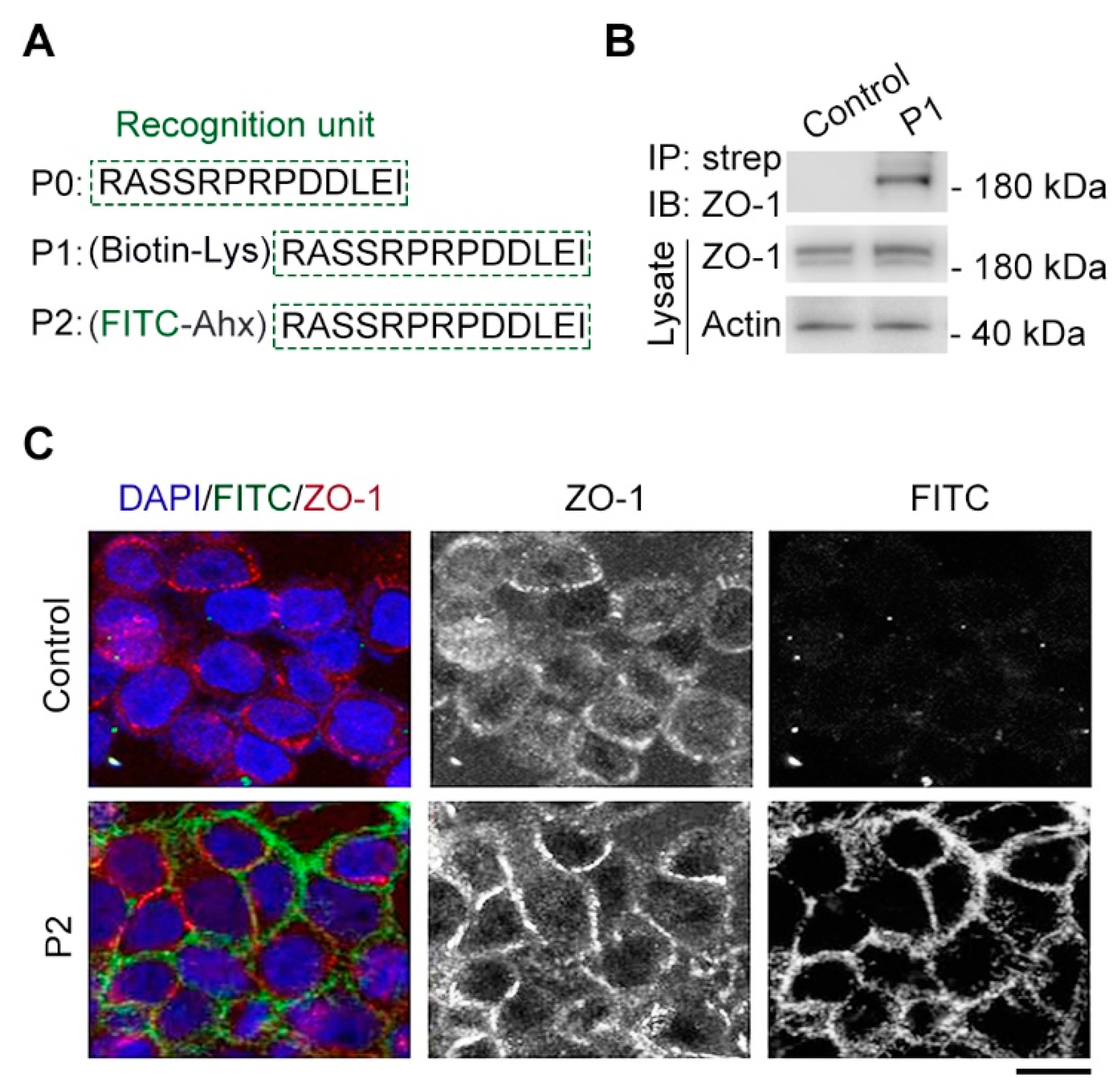

2.2. Modified tridecapeptide can bind ZO-1 and label cell junction of fixed cells

The tridecapeptide RASSRPRPDDLEI motif was referred to P0 as the recognition unit of cell junction and modified with biotin through introducing lysine (Lys) to test the binding between the tridecapeptide motif with ZO-1 protein by using streptavidin pulldown technique

[19] (Figure 2A). We performed transfection of HEK293 cells using the constructed ZO-1 plasmid for ZO-1 protein overexpression and after 24 hours, incubated the synthesized biotin-modified peptide (P1) in the cell lysates at room temperature for 4 hours. Then, the binding capacity of P1 with ZO-1 protein was confirmed through streptavidin-biotin pulldown and immunoblotting assays. As expected, biotinylated peptide could pull ZO-1 protein from cell lysates, whereas binding was not detected in the control group with only biotin (Figure 2B), suggesting the tridecapeptide RASSRPRPDDLEI motif could be used as recognition unit of ZO-1.

Next, the tridecapeptide was modified with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for fluorescent labeling of cell junction and an aminohexanoic (Ahx) acid was introduced as a protective group to improve the stability of FITC (Figure 2A). We then examined the synthesized FITC-modified peptide (P2) instead of antibody to label cell junction by immunofluorescence assay[3,7]. Pleasantly, there is some degree of colocalization between the FITC-modified peptide labeling and the tight junction component ZO-1 antibody staining, whereas colocalization was not detected in the control group with only FITC-Ahx (Figure 2C), suggesting the FITC-modified tridecapeptide could label cell junction of fixed cells.

Figure 2.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can bind ZO-1 and label cell junction. (A) The components of synthesized Cx43-derived peptide, which contains a recognition unit (P0), an introduced lysine (Lys) conjugated to biotin (P1), an introduced aminohexanoic (Ahx) acid conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dye (P2). (B) Gel images of streptavidin-biotin pulldown and immunoblotting reveal the binding between P1 and tight junction protein ZO-1. P1: (biotin-Lys) RASSRPRPDDLEI, strep: streptavidin. For the control group, a biotin-Lys (without the recognition unit) was used. (C) The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, fluorescent labeling location (green) for P2 and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. P2: (FITC-Ahx) RASSRPRPDDLEI, DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the control group, a FITC-Ahx (without the recognition unit) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Figure 2.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can bind ZO-1 and label cell junction. (A) The components of synthesized Cx43-derived peptide, which contains a recognition unit (P0), an introduced lysine (Lys) conjugated to biotin (P1), an introduced aminohexanoic (Ahx) acid conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dye (P2). (B) Gel images of streptavidin-biotin pulldown and immunoblotting reveal the binding between P1 and tight junction protein ZO-1. P1: (biotin-Lys) RASSRPRPDDLEI, strep: streptavidin. For the control group, a biotin-Lys (without the recognition unit) was used. (C) The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, fluorescent labeling location (green) for P2 and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. P2: (FITC-Ahx) RASSRPRPDDLEI, DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the control group, a FITC-Ahx (without the recognition unit) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm.

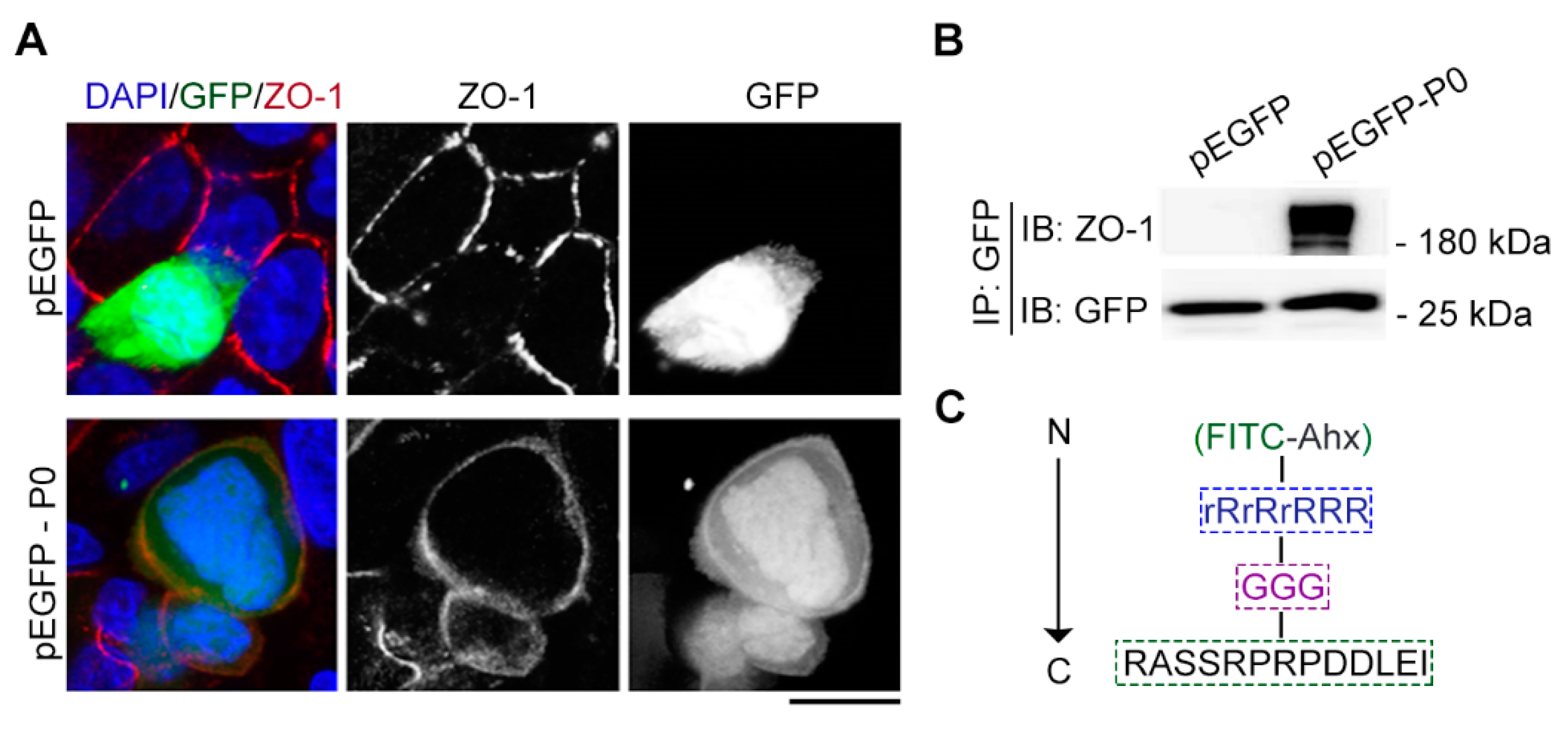

2.3. The tridecapeptide can localize at cell junction of living cells by plasmid expressing rather than using the membrane-penetrating peptide

Next, we examined whether the tridecapeptide could localize at cell junction of living cells. We successfully constructed an expression plasmid incorporating GFP for the tridecapeptide, and then transfected into Caco-2 cells with Lipofectamine 3000. Strikingly, microscopic observation of the living cell workstation

[20] showed that the tridecapeptide was also able to localize at cell junction of living cells, which can be confirmed by the co-localization of ZO-1 antibody staining after fixation of the cells (Figure 3A). To further validate the binding between tridecapeptide and cell junction protein ZO-1, we conducted immunoprecipitation assay based on beads coupled with GFP antibody. Consistent with microscopically observed co-localization results, the tridecapeptide fused with GFP could pull ZO-1 protein from cell lysates, whereas binding was not detected in the control group with only GFP (Figure 3B).

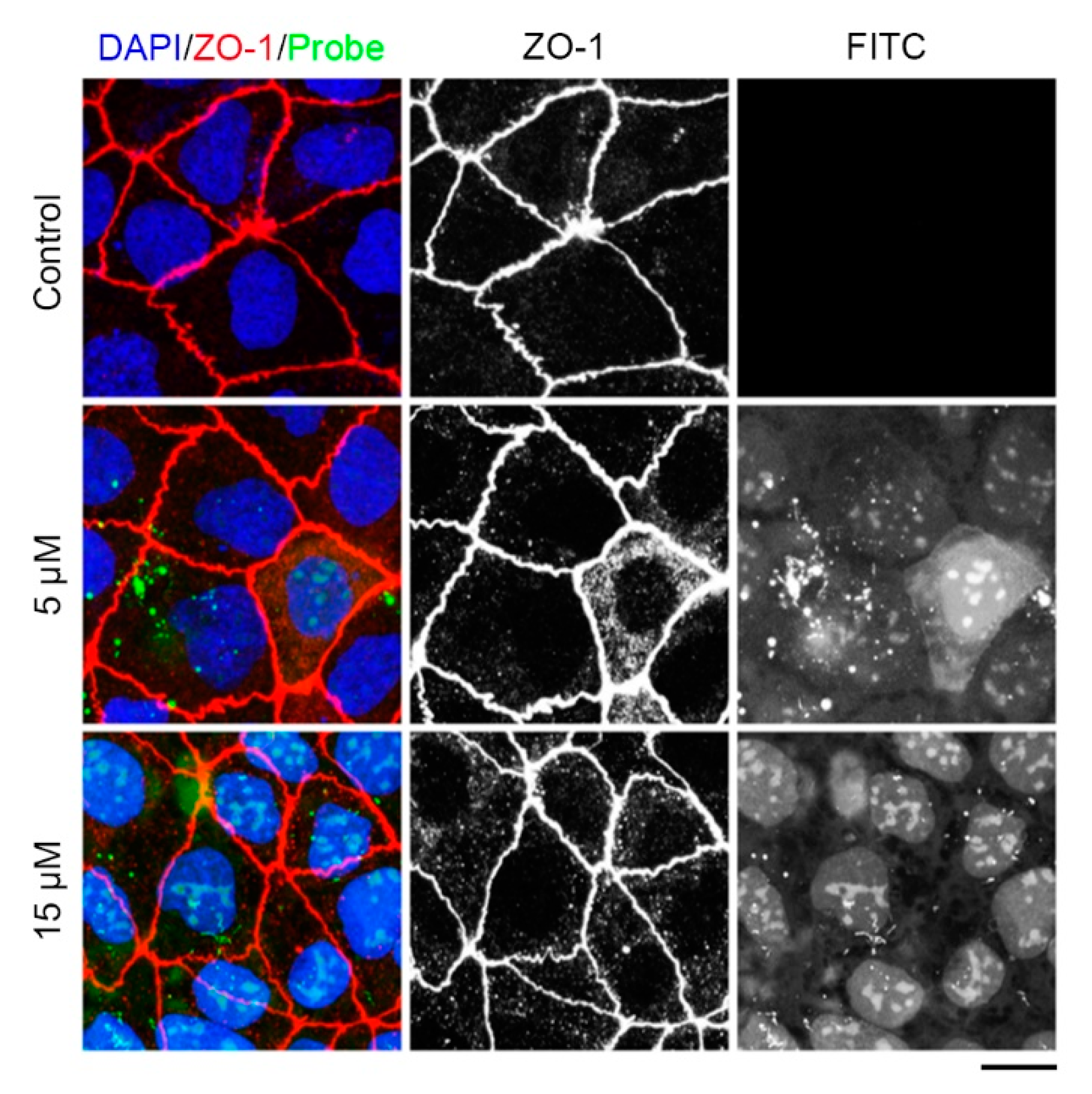

We supplemented an oligoarginine (rR)3R2 (r: D-Arg, R: L-Arg), a well-established cell-penetrating peptide[21,22] in order to more quickly transport the tridecapeptide into cells. To maintain the natural conformation of the tridecapeptide, three glycine residues were introduced as a spacer and to improve the stability of FITC, the Ahx acid was introduced as a protective group (Figure 3C). Then, we synthesized the designed fluorescent polypeptide and the control peptide that did not contain the cell-penetrating peptide. Last, we investigated whether the fluorescent polypeptide could effectively enter into living cells and label cell junctions. The cell-penetrating peptide (rR)3R2 was able to successfully deliver the fluorescent polypeptides into Caco-2 cells, whereas the control peptide lacking cell-penetrating peptide was unable to enter the cells (Figure 4). However, the fluorescent polypeptides were localized to the nucleus instead of the cell junction. After fixing the living cells, immunofluorescence staining with ZO-1 antibody indicated that cell junctions had been formed, which eliminate that the cell junctions had been not yet formed. Given these facts, we speculate that it is probably due to the stronger mutual attraction between the positively charged membrane-penetrating peptide and the nucleus than between the tridecapeptide and ZO-1 protein. Therefore, in order to label cell junction of living cells, it is necessary to retrofit the amino acid residues for increasing the tridecapeptide's affinity to ZO-1 protein.

Figure 3.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can localize at cell junction of living cells by binding ZO-1. (A) The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, location of the tridecapeptide (P0) fused with GFP (green) and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. P0: RASSRPRPDDLEI, DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the pEGFP group, an empty plasmid vector (without the P0) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Gel images of immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting reveal the binding between P0 and tight junction protein ZO-1. P0: RASSRPRPDDLEI. For the pEGFP group, an empty plasmid vector (without the P0) was used. (C) The component of fluorescent Cx43-derived peptide which contains a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dye at the N-terminus, a cell-penetrating peptide (rR)3R2, a spacer (GGG), and a ZO-1 recognition unit (RASSRPRPDDLEI) at the C-terminus. Ahx, e-aminocaproic acid; r denotes D-arginine, and R denotes L-arginine.

Figure 3.

Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can localize at cell junction of living cells by binding ZO-1. (A) The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, location of the tridecapeptide (P0) fused with GFP (green) and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. P0: RASSRPRPDDLEI, DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the pEGFP group, an empty plasmid vector (without the P0) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B) Gel images of immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting reveal the binding between P0 and tight junction protein ZO-1. P0: RASSRPRPDDLEI. For the pEGFP group, an empty plasmid vector (without the P0) was used. (C) The component of fluorescent Cx43-derived peptide which contains a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dye at the N-terminus, a cell-penetrating peptide (rR)3R2, a spacer (GGG), and a ZO-1 recognition unit (RASSRPRPDDLEI) at the C-terminus. Ahx, e-aminocaproic acid; r denotes D-arginine, and R denotes L-arginine.

Figure 4.

Examination of the tridecapeptide labeling cell junction in living cells. Caco-2 cells were treated with 5μM, 15 μM of the tridecapeptide or control peptide, together with Hoechst 33342, and 30 minutes later, the cells were imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, location (green) of the tridecapeptide in living cells and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the control group, a FITC fluorescence-modified peptide (without the cell-penetrating peptide) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Figure 4.

Examination of the tridecapeptide labeling cell junction in living cells. Caco-2 cells were treated with 5μM, 15 μM of the tridecapeptide or control peptide, together with Hoechst 33342, and 30 minutes later, the cells were imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. The images represent immunofluorescence staining (red) tight junction for ZO-1 antibody, location (green) of the tridecapeptide in living cells and staining nuclei (blue) for DAPI. DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. For the control group, a FITC fluorescence-modified peptide (without the cell-penetrating peptide) was used. Scale bars, 5 μm.

3. Discussion

Electron microscopy and immunofluorescence staining are currently major methods of observing cell junctions. For example, Hadate

et al., (2020)

[23] examined the structure of tenocytes by using transmission electron microscopy and serial block face-scanning electron microscopy and showed diverse forms of cell junctions, such as those between the cytoplasmic processes of adjacent tenocytes and between tenocytes' cytoplasmic processes and fibroblasts. Bao

et. al., (2019)

[24] observed the ultrastructure of cell junctions in mouse RPE by transmission electron microscope and explored the relationship and interplay between junction-associated proteins. A major limitation of the platforms is the autofluorescence of IP-S, the photoresin for TPP fabrication, which significantly increases background signal and makes fluorescent imaging of stretched cells difficult. Besides the method, immunofluorescence staining is also used to observe cell junctions. For instance, Li

et. al., (2019)

[25] assessed the expression and localization of cell junction molecule integrinβ1 in the stably transfected cell line by immunofluorescence staining. Edechi

et. al., (2021)

[26] was undertaken to determine the optimal fixation method, methanol or formalin, for the detection of cell junction molecule claudin 1 and E-cadherin by immunofluorescence. Rouaud

et. al., (2022)

[27] show by immunofluorescence that coronavirus receptor ACE2 colocalizes with ADAM17 and CD9 and the tight junction protein cingulin at apical junctions of intestinal (Caco-2), mammary (Eph4) and kidney (mCCD) epithelial cells. According to Edechi

et. al., (2021)

[26], immunofluorescence staining involves fixing living cells for the purpose of studying cell junctions. This also leads to the inability of the method to observe the dynamic assembly of cell junctions in real time. Therefore, our study aims to develop fluorescent molecules that label cell junction in living cells using a peptide-based strategy.

Increasing evidence suggests that the homologous motif peptide sequences are critical for the interactions between molecules. The first 17 aa of Abp140 is homologous among close relatives of

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is used as a marker to visualize F-actin structures in eukaryotic cells and tissues

[17]. Our previous research showed that tau-derived homologous motif peptide is able to bind both tubulins and microtubules

[22]. In this study, we tested Cx43-derived homologous tridecapeptide for its ability to label cell junction. Our data revealed that the modified tridecapeptide from Cx43 can bind tight junction protein ZO-1 and label cell junction of fixed cells. Furthermore, we founded that Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can localize at cell junction of living cells by binding ZO-1. The dynamic assembly of cell junctions in living cells is associated with many cellular activities. Alterations in the assembly of the tight junctions impair blood-brain barrier properties, particularly influenced barrier integrity and permeability. Kota

et. al., (2019)

[28] reported that activated M-Ras recruits Shoc2 to cell surface junctions where M-Ras/Shoc2 signaling contributes to the dynamic regulation of cell-cell junction turnover required for collective cell migration. Formation and maintenance of tissue barriers require the coordination of cell mechanics and cell-cell junction dynamic assembly. Recently, Kim

et. al., (2023)

[29] build bioengineered platforms using genetically modified human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes to model the early spatiotemporal process of cardiomyocyte junction assembly in vitro. Here, the modified tridecapeptide from Cx43 binds ZO-1 specifically and labels cell junction, providing an alternative tool for convenient cell junction labeling without the need of pricey antibodies, which may facilitate the studies about cell junctions. Although the modified tridecapeptide conjugated (rR)

3R

2 may not have a satisfactory image in living cells, our data suggest that using a peptide-based strategy for imaging subcellular structures is feasible. It is recommended that attempts be made to identify novel peptides with higher affinity in the future.

4. Materials & Methods

4.1. Materials

Antibodies against ZO-1 (33-9100) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), β-actin (A5316) (Sigma-Aldrich), GFP (50430-2-AP) (Proteintech) were purchased from the indicated sources. The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Abcam. Nocodazole, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and Streptavidin beads were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Caco-2 cells [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) number: HTB-37] were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries, BioInd).

4.2. Peptide synthesis

Using standard Fmoc chemistry from GenScript (Nanjing, China), Cx43-derived and scrambled control peptides were synthesized by solid phase methodology. N-terminal fluorescein labelling was carried out according to a previously described method

[30]. The synthesized peptides were purified by high performance liquid chromatography using a C-18 reversed phase column. They were then analyzed by mass spectrometry and tested solubility by double-distilled water, phosphate buffered solution or dimethyl sulfoxide.

4.3. Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells were disrupted in the lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific). The resulting lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4℃. For the immunoprecipitation,the samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with either streptavidin or agarose beads that were coated in a GFP antibody. The beads were rinsed five times, and affiliated proteins were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting techniques. For immunoblotting, Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The PVDF membranes were blocked in a solution of 5% fat-free dry milk in tris-buffered saline that contained 0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were blocked prior to incubation with primary and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. The proteins of interest were detected using enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pierce Biotechnology).

4.4. Fixed cell assays

The cells were fixed 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. This was followed by permeabilization using 0.5% Triton X-100.The fixed cells then underwent blocking with 4% bovine serine albumin in PBS and incubation with ZO-1 antibody. Subsequently, the secondary antibodies conjugated with either Alexa Fluor 568 was applied, and DAPI was used for staining. The FITC-conjugated peptide was added into the fixed cells, and incubated for 30 minutes. After washing three times in PBS, the fixed cells were imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using an HC PL APO CS2 63x /1.40 oil objective at 1024 x 1024 resolution and 1 x zoom factor. Tile scans were stitched with the Leica LAS AF software.

4.5. Living cell assays

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (ATCC number: CRL-1573) and Caco-2 cells (ATCC number: HTB-37) were cultured in the minimum essential medium (provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific) along with 10% fetal bovine serum (provided by Biological Industries) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 environment. After cell adherence, pEGFP-N1 plasmids expressing the peptide were transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS after 8 hours of transfection. On the other hand, the membrane-penetrating peptide-conjugated peptide was added into the Caco-2 cells, and incubated for 30 minutes. Then, the cells were washed three times with PBS. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime). The cells were imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using an HC PL APO CS2 63x /1.40 oil objective at 1024 x 1024 resolution and 1 x zoom factor. Tile scans were stitched with the Leica LAS AF software.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we revealed that the modified tridecapeptide from Cx43 can bind tight junction protein ZO-1 and label cell junction of fixed cells. Furthermore, we founded that Cx43-derived tridecapeptide can localize at cell junction of living cells by binding ZO-1. Here, the modified tridecapeptide from Cx43 binds ZO-1 specifically and labels cell junction, providing an alternative tool for convenient cell junction labeling without the need of pricey antibodies, which may facilitate the studies about cell junctions. Our data suggest that using a peptide-based strategy for imaging subcellular structures is feasible.

Author Contributions

Jingrui Li, Yuhan Wu, Chunyu Liu, Shu Zhang and Xin Su performed the assays search and data analysis. Jingrui Li and Songbo Xie carried out the study design. Jingrui Li drafted the manuscript amd Fengtang Yang revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR202102280532).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Sinyuk, M., E.E. Mulkearns-Hubert, O. Reizes, and J. Lathia. Cancer Connectors: Connexins, Gap Junctions, and Communication. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniagua, A.E., A. Segurado, J.F. Dolón, J. Esteve-Rudd, A. Velasco, et al., Key Role for CRB2 in the Maintenance of Apicobasal Polarity in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021. 9: p. 701853. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W., D. Li, D. Dong, Y. Li, Y. Zhang, et al., HIV-1 exposure triggers autophagic degradation of stathmin and hyperstabilization of microtubules to disrupt epithelial cell junctions. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020. 5(1): p. 79. [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., P. Zhou, W. Fu, L. Ding, W. Guo, et al., Spatially Selective Imaging of Cell-Matrix and Cell-Cell Junctions by Electrochemiluminescence. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2021. 60(21): p. 11769-11773. [CrossRef]

- Zaqout, S., L.L. Becker, and A.M. Kaindl, Immunofluorescence Staining of Paraffin Sections Step by Step. Front Neuroanat, 2020. 14: p. 582218. [CrossRef]

- Han, D., B. Goudeau, D. Jiang, D. Fang, and N. Sojic, Electrochemiluminescence Microscopy of Cells: Essential Role of Surface Regeneration. Anal Chem, 2021. 93(3): p. 1652-1657. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Z. Xu, H. Hu, M. Zheng, L. Zhang, et al., The Bacillus cereus toxin alveolysin disrupts the intestinal epithelial barrier by inducing microtubule disorganization through CFAP100. Sci Signal, 2023. 16(785): p. eade8111. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., L. Pan, Z. Wei, Y. Zhao, and M. Zhang, Domain-swapped dimerization of ZO-1 PDZ2 generates specific and regulatory connexin43-binding sites. Embo j, 2008. 27(15): p. 2113-23. [CrossRef]

- Javorsky, A., J.C. Maddumage, E.R.R. Mackie, T.P. Soares da Costa, P.O. Humbert, et al., Structural insight into the Scribble PDZ domains interaction with the oncogenic Human T-cell lymphotrophic virus-1 (HTLV-1) Tax1 PBM. Febs j, 2023. 290(4): p. 974-987. [CrossRef]

- Javorsky, A., P.O. Humbert, and M. Kvansakul, Structural basis of coronavirus E protein interactions with human PALS1 PDZ domain. Commun Biol, 2021. 4(1): p. 724. [CrossRef]

- Ashkinadze, D., H. Kadavath, A. Pokharna, C.N. Chi, M. Friedmann, et al., Atomic resolution protein allostery from the multi-state structure of a PDZ domain. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 6232. [CrossRef]

- Hisada, M., M. Hiranuma, M. Nakashima, N. Goda, T. Tenno, et al., High dose of baicalin or baicalein can reduce tight junction integrity by partly targeting the first PDZ domain of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1). Eur J Pharmacol, 2020. 887: p. 173436. [CrossRef]

- Imafuku, K., M. Kamaguchi, K. Natsuga, H. Nakamura, H. Shimizu, et al., Zonula occludens-1 demonstrates a unique appearance in buccal mucosa over several layers. Cell Tissue Res, 2021. 384(3): p. 691-702. [CrossRef]

- Solan, J.L. and P.D. Lampe, Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction channel assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2005. 1711(2): p. 154-63. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.J., C.J. Wallick, K.D. Martyn, A.F. Lau, C. Jin, et al., Akt phosphorylates Connexin43 on Ser373, a "mode-1" binding site for 14-3-3. Cell Commun Adhes, 2007. 14(5): p. 211-26. [CrossRef]

- Yogo, K., T. Ogawa, M. Akiyama, N. Ishida, and T. Takeya, Identification and functional analysis of novel phosphorylation sites in Cx43 in rat primary granulosa cells. FEBS Lett, 2002. 531(2): p. 132-6. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, J., A.H. Crevenna, K. Kessenbrock, J.H. Yu, D. Neukirchen, et al., Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nature Methods, 2008. 5(7): p. 605-607. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D., Z. Hu, F. Qiu, Z.-L. Huang, Y. Ma, et al., A general strategy for developing cell-permeable photo-modulatable organic fluorescent probes for live-cell super-resolution imaging. Nature Communications, 2014. 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., P. Zhou, Y. Kong, J. Li, Y. Li, et al., Inducible Degradation of Oncogenic Nucleolin Using an Aptamer-Based PROTAC. J Med Chem, 2023. 66(2): p. 1339-1348. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., M. Chen, J. Li, R. Hong, J. Yang, et al., A cilium-independent role for intraflagellar transport 88 in regulating angiogenesis. Sci Bull (Beijing), 2021. 66(7): p. 727-739. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., M. Chen, X. Zhang, S. Xie, J. Qin, et al., Peptide-based PROTACs: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Curr Med Chem, 2024. 31(2): p. 208-222. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Y. Li, M. Liu, and S. Xie, Modified heptapeptide from tau binds both tubulin and microtubules. Thorac Cancer, 2020. 11(10): p. 2993-2997. [CrossRef]

- Hadate, S., N. Takahashi, K. Kametani, T. Iwasaki, Y. Hasega, et al., Ultrastructural study of the three-dimensional tenocyte network in newly hatched chick Achilles tendons using serial block face-scanning electron microscopy. J Vet Med Sci, 2020. 82(7): p. 948-954. [CrossRef]

- Bao, H., S. Yang, H. Li, H. Yao, Y. Zhang, et al., The Interplay Between E-Cadherin, Connexin 43, and Zona Occludens 1 in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2019. 60(15): p. 5104-5111. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., C. Xu, K. Wang, Y. Ding, and L. Ding, Non-tight junction-related function of claudin-7 in interacting with integrinβ1 to suppress colorectal cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Manag Res, 2019. 11: p. 1443-1451. [CrossRef]

- Edechi, C.A., M. Amini, M.K. Hamedani, L.E.L. Terceiro, B.E. Nickel, et al., Comparison of Fixation Methods for the Detection of Claudin 1 and E-Cadherin in Breast Cancer Cell Lines by Immunofluorescence. J Histochem Cytochem, 2022. 70(2): p. 181-187. [CrossRef]

- Rouaud, F., I. Méan, and S. Citi, The ACE2 Receptor for Coronavirus Entry Is Localized at Apical Cell-Cell Junctions of Epithelial Cells. Cells, 2022. 11(4). [CrossRef]

- Kota, P., E.M. Terrell, D.A. Ritt, C. Insinna, C.J. Westlake, et al., M-Ras/Shoc2 signaling modulates E-cadherin turnover and cell-cell adhesion during collective cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019. 116(9): p. 3536-3545. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L., M.A. Trembley, K.Y. Lee, S. Choi, L.A. MacQueen, et al., Spatiotemporal cell junction assembly in human iPSC-CM models of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Reports, 2023. 18(9): p. 1811-1826. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D., Z. Hu, F. Qiu, Z.L. Huang, Y. Ma, et al., A general strategy for developing cell-permeable photo-modulatable organic fluorescent probes for live-cell super-resolution imaging. Nat Commun, 2014. 5: p. 5573. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).