1. Introduction

Cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) are 5-30 amino acid long peptides, capable of breaching cell membrane barriers without change in cell viability, while carrying cargoes much larger than themselves in an intact, fully functional form1,2. The first CPP identified was from the HIV coat protein, trans-activator of transcription (Tat)3,4. The cell penetrating abilities of Tat, an 86-amino acid protein, were mapped to short 11 amino acid, cationic, arginine- and lysine-rich domain. Subsequent studies showed that Tat could be fused to a much larger marker protein, beta-galactosidase, and upon systemic administration in wild-type mice resulted in robust transduction of multiple tissues, even crossing the blood-brain barrier and with diffuse uptake in neuronal tissue. However, such ubiquitous transduction was an obstacle to the development of these non-tissue specific CPPs as vectors for clinical use. This drawback was circumvented by use of phage display5. Using this technique6, investigators have identified peptides targeting tumors7, pancreatic islet cells8,9, adipose tissue10, synovial tissue11, and cardiomyocytes12 to name a few.

Our prior work utilizing an in vitro and in vivo phage display combinatorial methodology6 led to the identification of a unique, non-naturally occurring, mildly basic, 12-amino acid long peptide which we termed cardiac targeting peptide (CTP-APWHLSSQYSRT)12, due to its ability to robustly transduce cardiomyocytes in as little as 15 minutes, the earliest time-point tested, after a peripheral, intravenous injection13. This transduction ability was cardiomyocyte-specific and not species-limited13,14,15, with our findings confirmed by 5 independent laboratories from across the world14-19. As part of a larger set of studies intended to study the mechanism of transduction of this peptide, we performed an alanine scan in which each of the 12 amino acids were sequentially replaced by alanine, which led to the surrendipitous identification of two robust, lung targeting peptides (LTPs), S7A (APWHLSAQYSRT) and R11A (APWHLSSQYSAT). In the current body of work, we detail the work leading to identification of these LTPs, compare linear versus cyclized versions, and show that our lead LTP, cyclic R11A (cR11A) is taken up by lung tissue in as little as 15 minutes after an intravenous injection, and specifically targets alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells, the resident progenitor cells critical for post-injury lung regeneration, along with basal cells and ionocytes. We also present data on mechanism of cR11A’s uptake. Furthermore, as proof-of-concept, we show that using a linker with a disulfide bond, oligonucleotides can be covalently conjugated to the N-terminus of this peptide. Lastly, we provide an application of cR11A as a vector for delivery of siRNA targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike S and envelope E proteins in an air-liquid interface model of viral infection using human bronchial epithelial cells.

2. Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis: Linear peptides were synthesized on a Liberty CEM microwave synthesizer using Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chemistry. The N-terminal amino group of the peptides were conjugated with Cy5.5-NHS (Lumiprobe Corporation, Cat # 27020). Cyclic Cy5.5 labeled peptides were synthesized as above with a lysine added to the N-terminus, followed by head to tail cyclization using 3-(diethoxyphosphoryloxy)-1,2,3-benzotriazin-4(3H)-one in Dimethylformamide/Dichloromethane for 5 days at room temperature. The epsilon amino group of lysine was then labelled with Cy5.5-NHS in 0.1M Triethylammonium bicarbonate/acetonitrile at pH 8.5. The resulting Cy5.5 labelled peptides were purified by preparative C-18 RP-HPLC on a Waters Delta Prep 4000 chromatography system followed by lyophilization. All synthesized peptides underwent MALDI-TOF analysis of the purified conjugates for confirmation of the expected mass and identity of the final product.

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Rat cardiomyoblast cell line (H9C2, ATCC, Cat # CRL-1446) or human bronchial epithelial cell lines (HBEC, ATCC, Cat# PCS-300-010) were passaged and plated onto 6-well plates at a cell density of 100,000 cells/well. 48-hours later cells were incubated with 10μM of CTP, 1μM of linear LTPs, or 100nM of cyclic LTPs, with simultaneously co-incubation with 1μL/ml of yellow Live-Dead stain (Invitrogen, Cat # L34968) for 30 minutes, washed, trypsinized, cells collected, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 10 mins, washed, resuspended in 500μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and FACS performed on 10,000 cells. Untreated cells, cells treated with Live-Dead stain alone, and cells treated with 1μM of a scrambled, random peptide (RAN: TALACYPHTVGQ) were used as controls. All groups were tested in technical quadruplicates, and experiment repeated on different days to provide biological triplicates. Gating was performed on cells that were negative for the Live-Dead stain, thereby excluding dead cells. Serum Stability Studies: Linear and cyclic R11A were added to fetal bovine serum (FBS) at a final concentration of 10µg/ml, with 250µl of this aliquoted into Eppendorf tubes, and placed in a 37°C/5% CO2 incubator for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 and 360 minutes. At the end of each incubation time-point, tubes were removed, placed on ice, 25µL of 1µM C-peptide as an internal standard added to the tube, and vigorously vortexed for 15 seconds, followed by addition of 500μL of acetonitrile to each tube, vortexed for 30secs, and centrifuged at maximum speed in a tabletop centrifuge for 5 minutes at 4°C. The clear supernatant was transferred to a new tube andanalyzed using mass spectrophotometry. All peptides and all times were tested in triplicate.

Endocytosis Studies: In order to investigate the mechanism of cell entry, HBECs were serum starved overnight and treated with either Pitstop2 (15μM), Amiloride (400μM), or Nystatin (25μM) for 1 hour, followed by addition of cR11A (1μM) for 30 minutes. At the end of incubation period, the cells were washed, trypsinized, harvested, and fixed with 2% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT), followed by a single wash, resuspension in PBS, and subjected to FACS analysis. In another set of experiments, HBECs were treated with cR11A at 10μM for 30 minutes, followed by removal of cR11A and replacement with media for varying durations (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes). The cells were then fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized with 1× permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience, Cat# 00-8333-56), and blocked with 5% serum in PBS for 1 hour at RT. Cells were incubated with anti-LAMP1 antibody (Abcam, Cat# ab24170) overnight at 4°C, washed, and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody at RT for 1 hour, mounted with DAPI, imaged in 3D using a Zeiss LSM 980 microscope, and analyzed with Imaris software. Lastly, HBECs were grown on coverslips, serum starved for 4 hours at 4°C prior to being co-incubated at 37°C with Cy5.5 labeled linear or cyclic R11A or S7A along with Alexa-488 labeled transferrin for various time points. At the end of the incubation period, cells were washed, mounted in DAPI, and confocal microscopy performed.

Animal Studies: All animal protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh as well as Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Wild type, 6-week-old, CD1 (Charles Rivers, Cat #022) mice were weighed and anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a 1:1 cocktail of Ketamine: Xylazine at 1-2μL/gm body weight, followed by intravenous injection with Cy5.5 labeled peptides that were allowed to circulate for various time points. At the end of circulation times, mice were euthanized, chest cavity opened, right atrium nicked and 3-5ml of 10% formalin injected through the left ventricular apex to perfusion fix the animals. Various organs were harvested, rinsed once in PBS and imaged using an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS; Perkin- Elmer-S5 instrument) with identical instrument settings (stage position, exposure time, binning, F-stop etc.). Organs were placed in 10% formalin at RT for 4 hours, transferred to 15% sucrose at 4°C overnight, followed by 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight, before being embedded and cryo-sectioned at 6μm thickness. The sections were cross-stained with various primary antibodies for ATII cells (ABCA3), basal cells (p63, KRT5), ionocytes (FOXI1), goblet cells (MUC5AC), ATI cells (HOPX), ciliated cells (acetylated tubulin), club cells (Uteroglobin), pulmonary endothelial cells (CD31), and airway smooth muscle cells (α-SMA) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody at RT for 1 hour. Additionally, kidney sections were stained with Lotus tetragonolobus Lectin - FITC (LTL-FITC) at RT for 1 hour. All sections were then washed, mounted with DAPI, and confocal microscopy performed. All peptides and time-points were tested in triplicate (n=3).

Isolation of Single Cells from Mouse Lung Tissue: After injecting mice with cR11A as above, lungs were harvested and immediately placed in cold PBS with 2% FBS, cut into small pieces and transferred into a 50ml tube containing 5ml of digestion buffer (RPMI 1640 medium with 1× collagenase/ hyaluronidase (Stemcell, Cat#07912), and DNase I Solution 0.15mg/ml (Stemcell Cat# 07900), and incubated at 37ºC for 1 hour on a shaking platform at 180 rpm. After incubation, the digested tissue was strained through a 70µm strainer, rinsed with PBS containing 2% FBS and 1mM EDTA, filtered again through a 70µm strainer, and washed with cold PBS containing 2% FBS. Cells were pelleted, washed and treated with 5 mL 1× RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend, Cat# 420301) for 5 minutes, followed by 10 mL PEB buffer (1× PBS + 2 mM EDTA + 1% FBS) to stop the reaction, cells pelleted and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes, washed, and permeabilized with permeabilization buffer (eBioscience, Cat# 00-8333-56) at RT for 10 minutes. After three washes with PBS, the cells were blocked with mouse Fc-receptor blocker (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 14-9161-73) and 5% FBS in 0.1% TBST for 1 hour at RT, cells aliquoted and incubated with the primary antibodies for various cell types (see prior paragraph) at a 1:100 dilution at 4ºC overnight. After incubation, cells were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjungated secondary antibody at a 1:500 dilution, and 1μL/ml of yellow live/dead staining at RT for 1 hour, washed, and resuspended in 500 µL PBS for FACS. All FACS analyses were done in quadruplicate.

Design of anti-SARS-CoV-2 siRNA: An in-silico design of SARS-CoV-2 specific siRNA targeting key viral structural proteins, spike S, envelope E, and nuclear N proteins, was performed. We obtained SARS-CoV-2 complete genome sequence from GenBank (Accession Number: MN908947.3)20, and targeted gene-specific siRNA against SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins21 using siDirect2.0. We selected the optimal 2 siRNAs per target protein, based on thermodynamic stability.

Conjugation of siRNA to LTPs: C6 protected siRNA oligomers (IDT technologies) were reduced to their free thiol form using DL-Dithiothreitol in 0.1M Triethylammonium bicarbonate at pH 8.5 and then reacted with dithio-bis-maleimidoethane in 300mM NaOAc/acetonitrile at pH 5.2. Purification of the siRNA-DTME intermediate by precipitation with ethanol was followed by reaction with the purified cR11A peptide in 300mM NaOAc/acetonitrile at pH 5.2. Analytical C-18 RP-HPLC purification of the resulting siRNA-DTME-cR11A conjugate using triethylamine acetate/Acetonitrile gradients on a Waters Alliance chromatography system was performed, followed by lyophilization. Confirmation of the expected mass and identity of the final siRNA-cR11A conjugate was done by MALDI-TOF analysis on an Applied Biosystems Voyager workstation using 3-hydroxypicolinic acid matrix in ammonium citrate.

Anti-viral Testing of Cyclic R11A-siRNAs: The antiviral activity of two cR11A-siRNA were evaluated against SARS-CoV-2 (strain USA_WA1/2020) in a highly differentiated, three-dimensional, in vitro model of normal HBEC inserts (EpiAirwayTM AIR-100, AIR-112) originating from a single donor, # 9981, a 29-year-old, healthy, non-smoking, Caucasian female. Each siRNA-cR11A conjugate was tested for antiviral activity at 3 concentrations (1.8; 0.18; and 0.018 µM) in triplicate. Remdesivir was included as a positive control at 4 concentrations (2, 0.2, 0.02, and 0.002 µM) in triplicate. Cells were cultured at 37°C for 24 hours, and mucin layer removed by washing with 400µL of pre-warmed 30mM HEPES buffered saline solution. SARS-CoV-2 strain USA-WA1/2020 stock was diluted in AIR-100-MM medium before infection yielding a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 0.0015 cell culture infectious dose, 50% endpoint (CCID50) per cell. Treatment with siRNAs-cR11A (120µL) was applied to the basolateral and apical side for 24 hours prior to infection. For the infection, virus (120µL) was applied to the apical side for a 2-hour incubation, after which the medium was removed, and replaced with fresh medium. As a virus control, 3 of the wells were treated with cell culture medium only. After 5 days of culture, virus released into the apical compartment of the culture was collected and plated on Vero 76 cells for virus yield reduction titration. Collected virus was diluted in 10-fold increments and 200µL of each dilution transferred into four wells of a 96-well plate to determine 50% viral endpoints. After 5 days of incubation, each well was scored positive for virus if any cytopathic effects were observed as compared with the uninfected control. The virus dose that was able to infect 50% of the cell cultures (CCID50 per 0.1 mL) was calculated by the Reed-Muench method (1938) and expressed as log10 CCID50/ml. Untreated, uninfected cells were used as controls.

Statistical analysis: Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (Version 10). For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Dunnett’s test (for comparisons with a control group) or Tukey’s test (for pairwise comparisons among all groups). For comparisons between two groups, a student’s t-test was used. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Significance levels are indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

3. Results

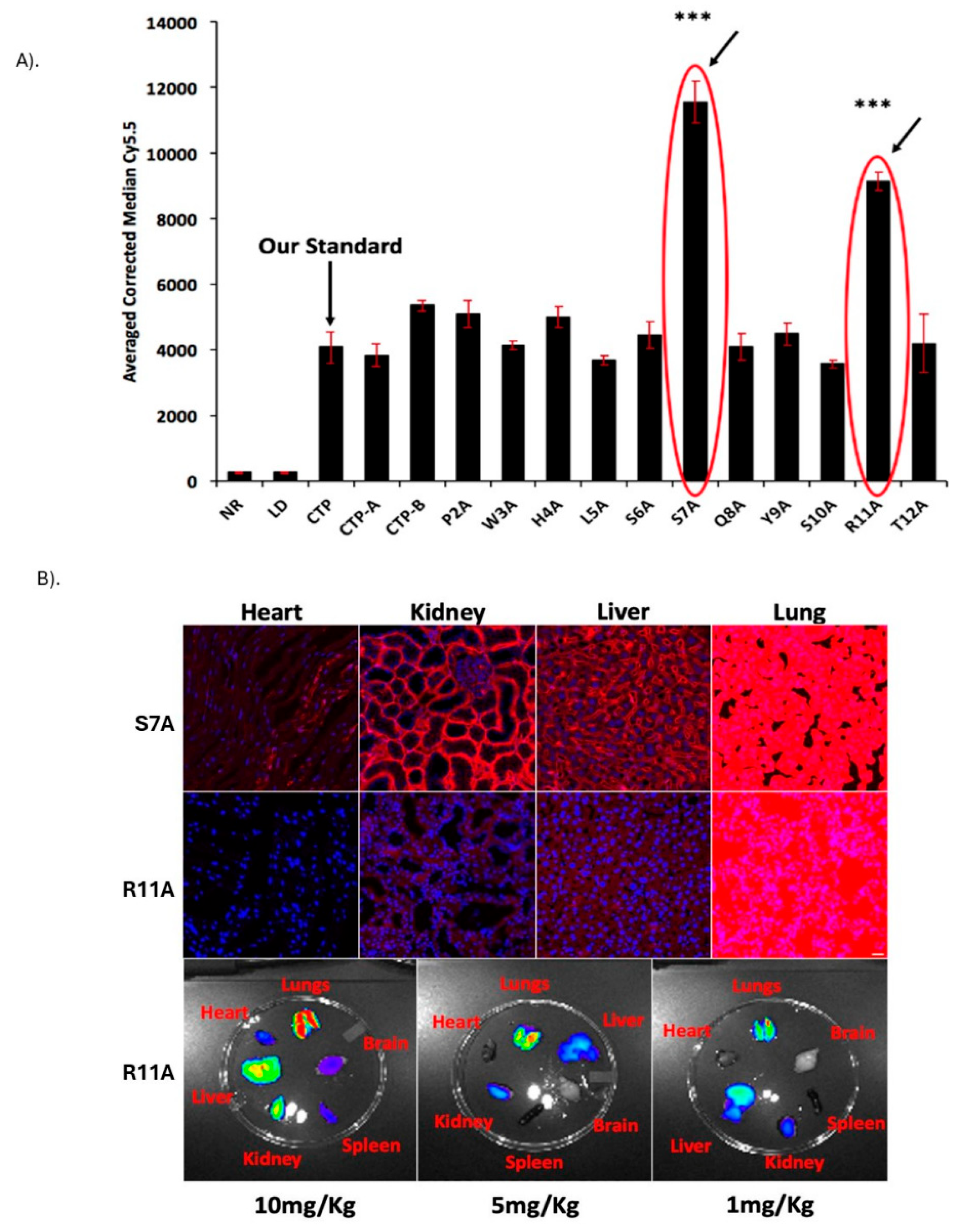

Identification and Biodistribution of Lung Targeting Peptides: Eleven “alanine mutant” versions of CTP were synthesized along with the 6 N-terminus CTP-A (APWHLS) and 6 C-terminus CTP-B (SQYSRT), along with CTP peptide as a standard comparison. H9C2 cells were incubated with 10μM of the fluorescent peptides and FACS performed (

Figure 1A). Two alanine mutant peptides, S7A and R11A, robustly transduced H9C2 cells with 2-3-fold greater uptake than the reference CTP peptide. These were injected intravenously in wild-type CD1 mice at a dose of 10mg/Kg. Counter to our expectations, uptake in the heart was negligible. Instead, there was robust lung uptake of both peptides with some uptake in the liver and kidneys (

Figure 1B: S7A top row; R11A middle row). Lung uptake of R11A was greater than that of S7A, with robust lung uptake of R11A even at 1mg/Kg with an increasingly favorable lung-to-liver ratio with decreasing dose (

Figure 1B-bottom row;

Supplemental Figure S1). To confirm uptake of these peptides by lung epithelial cells, HBECs were incubated with 10μM of S7A, R11A or RAN for 2, 10, and 30 minutes. R11A and S7A were taken up at 10 minutes with uptake increasing at 30 minutes, with no uptake of RAN by these cells (

Supplemental Figure S2).

Cyclization of LTPs: There have been multiple reports of cyclic versions of CPPs having higher transduction abilities

in vivo compared to their linear counterparts

22-24 felt to be secondary to improved serum stability. To test this hypothesis, we tested serum stability of linear versus cR11A using mass spectroscopy. Indeed, cR11A had higher serum stability compared to its linear counterpart (

Figure 2A-B). HBECs were incubated with linear (1μM) or cyclic peptides (100nM) for 30mins, and FACS performed. At 10-fold lower dose the cyclic peptides still showed an ~10-fold higher cellular uptake as assessed by fluorescence intensities, indicating an ~100-fold increase in transduction efficiencies (

Figure 2C).

Biodsitribution of Cyclic R11A: Based on these results, we opted to perform biodistribution study of cR11A. Wild-type, 6-week-old, CD1 mice were injected with 1mg/Kg of cR11A-Cy5.5 and allowed to circulate for 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 minutes, euthanized at the end of the circulation period, and ex-vivo IVIS imaging performed. Peak uptake by lungs had a bimodal distribution with uptake at 15 and 60 minutes. Fluorescence in liver biliary duct cells and renal proximal tubules increased over time indicating a hepatobiliary and renal mode of excretion, respectively, of either cR11A or its breakdown product(s) that remain fluorescently labeled (

Figure 3;

Supplemental Figure S3 and S4).

Studies into Transduction Mechanism: In order to investigate whether the mechanism of uptake involved endocytosis, HBECs were treated with cR11A with or without various endocytosis inhibitors. Uptake of cR11A was significantly reduced by treatment with Pitstop2, but not with Amiloride or Nystatin (

Figure 4A-B;

Supplemental Figure S5). In order to explore this relationship further, cR11A uptake and cellular localization was tracked relative to lysosomes (labeled with LAMP1). Our experiments revealed high colocalization of cR11A with LAMP1 at earliest time point (0 min), with reappearance of cR11A in the cytosol at 120 minutes independent of lysosomes, indicating lysosomal escape of it after cellular uptake (

Figure 4C-D). To confirm this last finding, HBECs were serum starved to stimulate endocytosis, and co-incubated with Alexa-488-transferrin along with S7A, R11A, cR11A, cS7A, or RAN, and confocal microscopy performed. Our results show that the peptides were internalized and did not show co-localization with the green fluorescence of endocytosed transferrin, indicating that the peptides were indeed escaping endocytic vesicles (

Figure 5).

Lung Cell Type Targeting by cR11A: To investigate the cell type in the lungs being targeted, wild-type mice were injected with cR11A or RAN at 1mg/Kg, or PBS, and lungs harvested after 15 minutes (

Supplemental Figure S6) for cryosectioning or single cell isolation for staining with various cellular markers (

Supplemental Table S1). Our single cell FACS indicated that ATII cells had the greatest uptake of cR11A with 33% of cells staining positive for ABCA3A also positive for Cy5.5 labeled cR11A (calculated by [Q2/Q1+Q2]*100), followed by p63+ cells (~23% double-positive) and ionocytes (14% double positive) (

Figure 6;

Supplemental Figure S7). Interestingly, cR11A was retained by ionocytes as far out as 6 hours, the latest time-point tested (

Figure 3-top row insert). Confocal microscopy of these lung sections confirmed our findings of highest colocalization of the cR11A (red) with ABCA3 (green), an ATII cell marker, followed by p63+ (basal cells), and ionocytes (

Figure 7;

Supplemental Figure S8). Linear R11A (10mg/Kg) showed lesser degree of uptake compared to cR11A (

Supplemental Figure S9), similar to our

in vitro findings (

Figure 2).

cR11A as Vector for siRNA Delivery: As proof of concept, we took two optimized siRNA per target proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus based on thermodynamic stability (

Supplemental Table S2) as possible anti-COVID therapy, and conjugated these to the N-terminus of cR11A via a DTME intermediate that contains an internal disulfide bond (

Figure 8A) which has been used to link multiple siRNAs together

25. Our rationale was that cR11A would internalize the siRNAs, and the disulfide bond would subsequently be cleaved in the reducing intracellular environment releasing the cargo siRNA to knock down target viral mRNA via the RISC complex arresting viral replication. The success of the conjugation was confirmed by MALDI-TOF analysis (

Supplemental Figure S10). Percent toxicity as well as percent cytopathic effects of the cR11A-siRNA conjugates in VERO cell lines was tested by pre-treating with the conjugates for 24 hours prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus. Of the conjugates tested, cR11A-S1 and cR11A-E2, appeared to be most promising (

Supplemental Table S3) in VERO cell lines. Therefore, the antiviral activity of these two conjugates was evaluated further against SARS-CoV-2 (strain USA_WA1/2020) in an

in vitro air-liquid interface of normal human bronchial cells. cR11A-S1 inhibited viral replication with an EC90 value of 0.64 ± 0.2 µM, while cR11A-E2 inhibited virus replication with an EC90 value of 1.04 ± 0.2 µM; for comparison purpose Remdesivir inhibited viral replication with an EC90 value of 0.019 µM (

Figure 8B-C).

4. Discussion

In contrast to deep seated organs like the heart and brain, lungs enjoy a dual route of administration via inhalational or systemic delivery. Although the inhalational route has distinct advantages, like decreased dose requirement, less systemic side effects, and bypassing of the hepatobiliary system, it is not a feasible route in conditions riddled by thick mucus secretions, a hallmark of pathologies like cystic fibrosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or primary ciliary dyskinesia, that result in entrapment of drugs. Another factor to consider is that a large fraction of inhaled drug is deposited in the upper airways and may not reach the terminal bronchioles or alveolar epithelial cells. Gene-based therapeutics for lung disorders have failed to develop due to the presence of inherent physical barriers like surface mucus, mucociliary clearance, cell-to-cell tight junctions, and the basolateral cell membrane location of viral receptors for many commonly used viral vectors. In addition, viral vectors are associated with either pre-existing immunity or development of neutralizing antibodies on first exposure, along with potentially lethal side effects like the cytokine release syndrome26,27. In contrast, CPPs have not been reported to trigger immune responses28-31. In fact, our data with the parent CTP have shown significant anti-inflammatory effects (unpublished data). Hence, CPPs that specifically target lung tissue would represent viable, alternative vectors that could bypass this bottleneck and lead to the clinical realization of multiple therapeutics.

Our current body of work has identified a unique, 12-amino acid long CPP, cR11A, that targets 33% of ATII cells of the lungs after an intravenous delivery, as well as p63+ basal cells (22%) and ionocytes (14%) at the dose and time-point (15 minutes) tested, though higher uptake is possible at 60 minutes. As a reference, ATII cells represent ~15% of total lung cell population

32. Interestingly, uptake by Ionocytes was retained as late as 6 hours, the latest time-point tested (

Figure 3-insert). In vitro uptake of cR11A by human bronchial epithelial cells appears to be mediated by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, with escape from these vesicles at later timepoint. We have direct evidence of it by confocal microscopy, as well as indirect evidence in the form of delivered anti-SARS-CoV2 siRNA retaining their anti-viral activity. This would not be possible if there was endosomal entrapment of the cR11A-siRNA conjugate as the inside of an endosome is still outside of the cytoplasm. This endosomal escape mechanism has been reported for other CPPs, postulating an endosomal budding and collapse mechanism

33-35.

We chose to follow detailed biodistribution of cR11A in preference over S7A, as the former showed uptake even at the lowest 1mg/kg dose with lung to liver ratios increasing with lowering of the dose. Lung uptake of cR11A occurred in as little as 15 minutes, which is similar to CTP, where peak uptake also occurred at 15 mins, the earliest time point tested13. At later timepoints there is appearance of fluorescence in the liver and kidneys with the pattern suggesting hepatobiliary and renal tubular excretion, respectively. Interestingly, there was a bimodal distribution pattern with fluorescence in the lungs showing a second peak at 60 minutes. We compared the cyclized version of both S7A and R11A to their linear counterparts and found that cyclization increased serum stability and uptake by ~100-fold, findings similar to other investigator’s experience 35-37. cR11A did not cross the blood-brain barrier with no fluorescence seen in brain tissue on IVIS imaging or confocal microscopy. This is an important observation in light of the recent report of cationic peptides (like Tat or homopolymers of arginine) causing memory loss in mice38. The most exciting finding of our study is that cR11A preferentially targeted one-third of all ATII cells in vivo as well as basal cells and ionocytes, with prolonged retention of cR11A by ionocytes. ATII cells are the resident lung progenitor cells with stem cell-like properties, and responsible for regeneration and replacement of type I alveolar cells in response to myriad different insults39-41, playing a key role in lung regeneration42. Additionally, they produce surfactant proteins to reduce lung surface tension and maintain alveolar patency. Recent investigations have identified cellular senescence of ATII as a critical cause of their stemness failure43 associated with telomere shortening44. Indeed, senescence, apoptosis, and decreased number of ATII cells play a key role in pathophysiology of conditions like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis43 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease45. Lastly as proof-of-concept cR11A was selected to carry duplex siRNA conjugated to its N-terminus via a DTME linker, targeting various structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 virus. RNA interference as a therapeutic strategy against SARS-CoV-2 has been demonstrated by others46,47, utilizing lipid nanoparticles48,49, and peptide-dendrimers50. The advantage of our approach is use of a lung-specific CPP, possibility of systemic delivery bypassing the mucus barrier, with its transduction capabilities further optimized via a cyclization strategy. Our proof-of-concept studies showed anti-viral activity for an siRNA targeting the spike and one targeting the envelope protein.

In the pulmonary space, development of CPPs have been largely in the context of targeting lung cancers51,52. One strategy to target lung cancer takes advantage of the tumor microenvironment by engineering non-tissue specific CPPs and activating them in the tumor microenvironment. This was achieved by neutralizing the polycationic structure of these peptides via linkage to polyanionic peptides via a cleavable linker. These linkers were designed to take advantage of greater metalloproteinase 2 expression in the tumor microenvironment53, or greater oxidative stress, leading to cleaving of the neutralizing peptide and unmasking of the CPP54. In another application, a nine amino acid long cyclic peptide, CARSKNKDC, was reported as targeting multiple layers of pulmonary arteries in a rat model of pulmonary hypertension55, and was used to deliver micelles containing fasudil, a pulmonary hypertension drug, to pulmonary endothelium56. This uptake was limited to pulmonary endothelial cells and did not target deeper lung tissue. More recently, Soto and collegaues used phage display to identify a CPP targeting HBECs, incorporating it into lipid nanoparticles to deliver mRNA to bronchial epithelial cells in wild-type mice57. However, the conjugates were delivered intra-tracheally in wild-type mice making it difficult to extend the findings to cystic fibrosis lungs with thicker mucus layer.

Our study has several exciting, seminal findings. To the best of our knowledge, tissue-specific CPPs targeting ATII cells in vivo has not been reported before. This could open up a field of myriad, pathophysiologically driven, disease-modifying therapeutic cargoes being delivered in conditions where underlying ATII cell defects play a leading role. Additionally, ability of cR11A to target ionocytes after an intravenous injection has profound implications for cystic fibrosis due to these cells having a high expression of CFTR protein58, and their ability to mediate chloride absorption across airway epithelium59. cR11A could be utilized to deliver anti-sense oligonucleotides, like Eluforsen, to correct splicing mutation in F508del cystic fibrosis60. In the CPP field, a multitude of investigators have reported mixing siRNA/miRNA with CPPs to generate nanoparticles by leveraging charge interactions between non-tissue specific positively charged peptides and negatively charged oligonucleotides. For this work, we developed chemistries to allow for a 1:1 conjugation of CPPs to oligonucleotides through a disulfide containing linker that is hydrolyzed in the intracellular reducing environment releasing the cargo. In addition to current work, we have utilized this strategy to deliver miRNA106a using CTP to human cardiomyocyte cell line in vitro and shown reversal of hypertrophy with down regulation of calcium calmodulin kinase IIδ18.

Our studies have identified several new lines of inquiry, top most of which is studying the ability of cR11A to deliver siRNA in vivo. Another line of study would be identification of the specific lung cells being targeted by S7A. These form the basis of ongoing studies.

5. Conclusions

We have identified a novel cyclic CPP, cR11A, that targets ATII, p63+ cells and ionocytes after an intravenous delivery in as little as 15 minutes. We have successfully conjugated cR11A to oligonucleotides and demonstrated an anti-viral effect in an air-liquid interface bronchial epithelial cell culture.

Take Home Message: Cell penetrating peptides cross cell-membrane barriers while carrying cargoes many-fold larger than themselves in a fully functional form. We identified a cyclized peptide that targets the lung alveolar epithelial type II cells, basal cells, and ionocytes in vivo, and show its ability to deliver siRNA ex-vivo in an air-liquid interface culture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

JW: GS did immunofluorescence staining, FACS and endocytosis studies; SM did transferrin studies; KSF did the alanine scan; JS, KM, performed the FACS and animal injections; RF proof-read the manuscript; HY did in silico dentification of SARS-CoV-2 siRNA; RY, KI and JMB did peptide synthesis, cyclization, and conjugation of siRNA to cR11A. MZ procured funding, designed experiments, interpreted data, prepared the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

University of Pittsburgh utilized the nonclinical/pre-clinical services offered by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to perform the SARS-CoV-2 work. We are also deeply grateful to Dr. Brett Hurst, Utah State University, for carrying out all of the viral work in a BSL3 environment. We are also deeply grateful to Drs. Amy Ryan (University of Iowa), Daniel Tschumperlin (Mayo Clinic), Douglas Brownfield (Mayo Clinic), and Michael F. Romero (Mayo Clinic) for their thoughtful review of our work.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by an R01 grant HL153407 from the NHLBI awarded to MZ, and from the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and the DSF Charitable Foundation.

References

- Zahid M, Robbins PD. Cell-type specific penetrating peptides: therapeutic promises and challenges. Molecules. 2015;20:13055-13070. [CrossRef]

- Taylor RE, Zahid M. Cell Penetrating Peptides, Novel Vectors for Gene Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Green M, Loewenstein PM. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell. 1988;55:1179-1188. [CrossRef]

- Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189-1193. [CrossRef]

- Smith, GP. Smith GP. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science. 1985;228:1315-1317. [CrossRef]

- Zahid M, Robbins PD. Identification and characterization of tissue-specific protein transduction domains using peptide phage display. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;683:277-289. [CrossRef]

- Arap W, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Cancer treatment by targeted drug delivery to tumor vasculature in a mouse model. Science. 1998;279:377-380. [CrossRef]

- Rehman KK, Bertera S, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Mai JC, Mi Z, Trucco M, Robbins PD. Protection of islets by in situ peptide-mediated transduction of the Ikappa B kinase inhibitor Nemo-binding domain peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9862-9868. [CrossRef]

- Mi Z, Mai J, Lu X, Robbins PD. Characterization of a class of cationic peptides able to facilitate efficient protein transduction in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2000;2:339-347. [CrossRef]

- Kolonin MG, Saha PK, Chan L, Pasqualini R, Arap W. Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nat Med. 2004;10:625-632. [CrossRef]

- Mi Z, Lu X, Mai JC, Ng BG, Wang G, Lechman ER, Watkins SC, Rabinowich H, Robbins PD. Identification of a synovial fibroblast-specific protein transduction domain for delivery of apoptotic agents to hyperplastic synovium. Mol Ther. 2003;8:295-305. [CrossRef]

- Zahid M, Phillips BE, Albers SM, Giannoukakis N, Watkins SC, Robbins PD. Identification of a cardiac specific protein transduction domain by in vivo biopanning using a M13 phage peptide display library in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12252. [CrossRef]

- Zahid M, Feldman KS, Garcia-Borrero G, Feinstein TN, Pogodzinski N, Xu X, Yurko R, Czachowski M, Wu YL, Mason NS, et al. Cardiac Targeting Peptide, a Novel Cardiac Vector: Studies in Bio-Distribution, Imaging Application, and Mechanism of Transduction. Biomolecules. 2018;8. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Mun D, Kang JY, Lee SH, Yun N, Joung B. Improved cardiac-specific delivery of RAGE siRNA within small extracellular vesicles engineered to express intense cardiac targeting peptide attenuates myocarditis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;24:1024-1032. [CrossRef]

- Avula UM, Yoon HK, Lee CH, Kaur K, Ramirez RJ, Takemoto Y, Ennis SR, Morady F, Herron T, Berenfeld O, et al. Cell-selective arrhythmia ablation for photomodulation of heart rhythm. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:311ra172. [CrossRef]

- Li YJ, Hua X, Zhao YQ, Mo H, Liu S, Chen X, Sun Z, Wang W, Zhao Q, Cui Z, et al. An Injectable Multifunctional Nanosweeper Eliminates Cardiac Mitochondrial DNA to Reduce Inflammation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025:e2404068. [CrossRef]

- Kehr D, Ritterhoff J, Glaser M, Jarosch L, Salazar RE, Spaich K, Varadi K, Birkenstock J, Egger M, Gao E, et al. S100A1ct: A Synthetic Peptide Derived From S100A1 Protein Improves Cardiac Performance and Survival in Preclinical Heart Failure Models. Circulation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gallicano GI, Fu J, Mahapatra S, Sharma MVR, Dillon C, Deng C, Zahid M. Reversing Cardiac Hypertrophy at the Source Using a Cardiac Targeting Peptide Linked to miRNA106a: Targeting Genes That Cause Cardiac Hypertrophy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022;15. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Yun N, Mun D, Kang JY, Lee SH, Park H, Park H, Joung B. Cardiac-specific delivery by cardiac tissue-targeting peptide-expressing exosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;499:803-808. [CrossRef]

- Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, Hu Y, Tao ZW, Tian JH, Pei YY, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265-269. [CrossRef]

- Ui-Tei K, Naito Y, Nishi K, Juni A, Saigo K. Thermodynamic stability and Watson-Crick base pairing in the seed duplex are major determinants of the efficiency of the siRNA-based off-target effect. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:7100-7109. [CrossRef]

- Nischan N, Herce HD, Natale F, Bohlke N, Budisa N, Cardoso MC, Hackenberger CP. Covalent attachment of cyclic TAT peptides to GFP results in protein delivery into live cells with immediate bioavailability. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:1950-1953. [CrossRef]

- Mandal D, Nasrolahi Shirazi A, Parang K. Cell-penetrating homochiral cyclic peptides as nuclear-targeting molecular transporters. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:9633-9637. [CrossRef]

- Cascales L, Henriques ST, Kerr MC, Huang YH, Sweet MJ, Daly NL, Craik DJ. Identification and characterization of a new family of cell-penetrating peptides: cyclic cell-penetrating peptides. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36932-36943. [CrossRef]

- Brown JM, Dahlman JE, Neuman KK, Prata CAH, Krampert MC, Hadwiger PM, Vornlocher HP. Ligand Conjugated Multimeric siRNAs Enable Enhanced Uptake and Multiplexed Gene Silencing. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2019;29:231-244. [CrossRef]

- Somanathan S, Calcedo R, Wilson JM. Adenovirus-Antibody Complexes Contributed to Lethal Systemic Inflammation in a Gene Therapy Trial. Mol Ther. 2020;28:784-793. [CrossRef]

- Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Macasaet R, Liu J, Velasco JV, Peligro PJ, Vallo J, Goldrich N, Lahoti L, Zhou J, et al. Infusion reactions to adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based gene therapy: Mechanisms, diagnostics, treatment and review of the literature. J Med Virol. 2023;95:e29305. [CrossRef]

- Suhorutsenko J, Oskolkov N, Arukuusk P, Kurrikoff K, Eriste E, Copolovici DM, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides, PepFects, show no evidence of toxicity and immunogenicity in vitro and in vivo. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:2255-2262. [CrossRef]

- Carter E, Lau CY, Tosh D, Ward SG, Mrsny RJ. Cell penetrating peptides fail to induce an innate immune response in epithelial cells in vitro: implications for continued therapeutic use. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85:12-19. [CrossRef]

- Young Kim H, Young Yum S, Jang G, Ahn DR. Discovery of a non-cationic cell penetrating peptide derived from membrane-interacting human proteins and its potential as a protein delivery carrier. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11719. [CrossRef]

- Lopuszynski J, Wang J, Zahid M. Beyond Transduction: Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Cell Penetrating Peptides. Molecules. 2024;29. [CrossRef]

- Guo M, Morley MP, Jiang C, Wu Y, Li G, Du Y, Zhao S, Wagner A, Cakar AC, Kouril M, et al. Guided construction of single cell reference for human and mouse lung. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4566. [CrossRef]

- Pei, D. How Do Biomolecules Cross the Cell Membrane? Acc Chem Res. 2022;55:309-318. [CrossRef]

- Sahni A, Qian Z, Pei D. Cell-Penetrating Peptides Escape the Endosome by Inducing Vesicle Budding and Collapse. ACS Chem Biol. 2020;15:2485-2492. [CrossRef]

- Qian Z, Martyna A, Hard RL, Wang J, Appiah-Kubi G, Coss C, Phelps MA, Rossman JS, Pei D. Discovery and Mechanism of Highly Efficient Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biochemistry. 2016;55:2601-2612. [CrossRef]

- Park SE, Sajid MI, Parang K, Tiwari RK. Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides as Efficient Intracellular Drug Delivery Tools. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:3727-3743. [CrossRef]

- Song J, Qian Z, Sahni A, Chen K, Pei D. Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides with Single Hydrophobic Groups. Chembiochem. 2019;20:2085-2088. [CrossRef]

- Stokes EG, Vasquez JJ, Azouz G, Nguyen M, Tierno A, Zhuang Y, Galinato VM, Hui M, Toledano M, Tyler I, et al. Cationic peptides cause memory loss through endophilin-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2025;638:479-489. [CrossRef]

- Aspal M, Zemans RL. Mechanisms of ATII-to-ATI Cell Differentiation during Lung Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [CrossRef]

- Choi J, Park JE, Tsagkogeorga G, Yanagita M, Koo BK, Han N, Lee JH. Inflammatory Signals Induce AT2 Cell-Derived Damage-Associated Transient Progenitors that Mediate Alveolar Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:366-382 e367. [CrossRef]

- Chong L, Ahmadvand N, Noori A, Lv Y, Chen C, Bellusci S, Zhang JS. Injury activated alveolar progenitors (IAAPs): the underdog of lung repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80:145. [CrossRef]

- Shao S, Zhang N, Specht GP, You S, Song L, Fu Q, Huang D, You H, Shu J, Domissy A, et al. Pharmacological expansion of type 2 alveolar epithelial cells promotes regenerative lower airway repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2400077121. [CrossRef]

- Parimon T, Chen P, Stripp BR, Liang J, Jiang D, Noble PW, Parks WC, Yao C. Senescence of alveolar epithelial progenitor cells: a critical driver of lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2023;325:C483-C495. [CrossRef]

- van Batenburg AA, Kazemier KM, van Oosterhout MFM, van der Vis JJ, Grutters JC, Goldschmeding R, van Moorsel CHM. Telomere shortening and DNA damage in culprit cells of different types of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Hu Q, Ansari M, Riemondy K, Pineda R, Sembrat J, Leme AS, Ngo K, Morgenthaler O, Ha K, et al. Airway-derived emphysema-specific alveolar type II cells exhibit impaired regenerative potential in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2024;64. [CrossRef]

- Tolksdorf B, Nie C, Niemeyer D, Röhrs V, Berg J, Lauster D, Adler JM, Haag R, Trimpert J, Kaufer B, et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Replication by a Small Interfering RNA Targeting the Leader Sequence. Viruses. 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Gallicano GI, Casey JL, Fu J, Mahapatra S. Molecular targeting of vulnerable RNA sequences in SARS CoV-2: identifying clinical feasibility. Gene Ther. 2022;29:304-311. [CrossRef]

- Idris A, Davis A, Supramaniam A, Acharya D, Kelly G, Tayyar Y, West N, Zhang P, McMillan CLD, Soemardy C, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 targeted siRNA-nanoparticle therapy for COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Saify Nabiabad H, Amini M, Demirdas S. Specific delivering of RNAi using Spike's aptamer-functionalized lipid nanoparticles for targeting SARS-CoV-2: A strong anti-Covid drug in a clinical case study. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2022;99:233-246. [CrossRef]

- Khaitov M, Nikonova A, Shilovskiy I, Kozhikhova K, Kofiadi I, Vishnyakova L, Nikolskii A, Gattinger P, Kovchina V, Barvinskaia E, et al. Silencing of SARS-CoV-2 with modified siRNA-peptide dendrimer formulation. Allergy. 2021;76:2840-2854. [CrossRef]

- Qiu M, Ouyang J, Wei Y, Zhang J, Lan Q, Deng C, Zhong Z. Selective Cell Penetrating Peptide-Functionalized Envelope-Type Chimeric Lipopepsomes Boost Systemic RNAi Therapy for Lung Tumors. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8:e1900500. [CrossRef]

- Liu D, Angelova A, Liu J, Garamus VM, Angelov B, Zhang X, Li Y, Feger G, Li N, Zou A. Self-assembly of mitochondria-specific peptide amphiphiles amplifying lung cancer cell death through targeting the VDAC1-hexokinase-II complex. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:4706-4716. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Wang T, Perche F, Taigind A, Torchilin VP. Enhanced anticancer activity of nanopreparation containing an MMP2-sensitive PEG-drug conjugate and cell-penetrating moiety. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:17047-17052. [CrossRef]

- Weinstain R, Savariar EN, Felsen CN, Tsien RY. In vivo targeting of hydrogen peroxide by activatable cell-penetrating peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:874-877. [CrossRef]

- Urakami T, Järvinen TA, Toba M, Sawada J, Ambalavanan N, Mann D, McMurtry I, Oka M, Ruoslahti E, Komatsu M. Peptide-directed highly selective targeting of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2489-2495. [CrossRef]

- Gupta N, Ibrahim HM, Ahsan F. Peptide-micelle hybrids containing fasudil for targeted delivery to the pulmonary arteries and arterioles to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Pharm Sci. 2014;103:3743-3753. [CrossRef]

- Soto MR, Lewis MM, Leal J, Pan Y, Mohanty RP, Veyssi A, Maier EY, Heiser BJ, Ghosh D. Discovery of peptides for ligand-mediated delivery of mRNA lipid nanoparticles to cystic fibrosis lung epithelia. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2024;35:102375. [CrossRef]

- Luan X, Henao Romero N, Campanucci VA, Le Y, Mustofa J, Tam JS, Ianowski JP. Pulmonary Ionocytes Regulate Airway Surface Liquid pH in Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;210:788-800. [CrossRef]

- Lei L, Traore S, Romano Ibarra GS, Karp PH, Rehman T, Meyerholz DK, Zabner J, Stoltz DA, Sinn PL, Welsh MJ, et al. CFTR-rich ionocytes mediate chloride absorption across airway epithelia. J Clin Invest. 2023;133. [CrossRef]

- Sermet-Gaudelus I, Clancy JP, Nichols DP, Nick JA, De Boeck K, Solomon GM, Mall MA, Bolognese J, Bouisset F, den Hollander W, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide eluforsen improves CFTR function in F508del cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:536-542. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Identification and Biodistribution of Lung Targeting Peptides. A). Alanine scan of the original CTP peptide. FACS of H9C2 cells incubated with alanine variants of CTP, and C- and N-terminal 6 amino acid versions. Cy5.5 intensities were almost 3-fold higher in the S7A and R11A versions. All cell work done in biological triplicates on different days, and technical quadruplicates. Error bars represent standard deviations. ***p<0.001 compared to CTP (our standard) for uptake. B). Lung uptake of S7A and R11A. Wild-type mice were injected intravenously with 10mg/kg of fluorescently labeled S7A (top row) or R11A (bottom row), euthanized at 15 mins and confocal microscopy performed of heart, kidney, liver, and lung tissues. First three panels imaged using same parameters-lungs imaged with significantly shorter exposure times due to fluorescence saturation. Bottom row-Mice injected with decreasing doses of R11A (10, 5, and 1mg/kg), euthanized at 15 mins and ex vivo imaging of multiple organs performed using IVIS imaging system. There was robust lung uptake of R11A even at the lowest (1mg/kg) dose. N=3. Red-Peptides; Blue-DAPI. Scale bar represents 20μm.

Figure 1.

Identification and Biodistribution of Lung Targeting Peptides. A). Alanine scan of the original CTP peptide. FACS of H9C2 cells incubated with alanine variants of CTP, and C- and N-terminal 6 amino acid versions. Cy5.5 intensities were almost 3-fold higher in the S7A and R11A versions. All cell work done in biological triplicates on different days, and technical quadruplicates. Error bars represent standard deviations. ***p<0.001 compared to CTP (our standard) for uptake. B). Lung uptake of S7A and R11A. Wild-type mice were injected intravenously with 10mg/kg of fluorescently labeled S7A (top row) or R11A (bottom row), euthanized at 15 mins and confocal microscopy performed of heart, kidney, liver, and lung tissues. First three panels imaged using same parameters-lungs imaged with significantly shorter exposure times due to fluorescence saturation. Bottom row-Mice injected with decreasing doses of R11A (10, 5, and 1mg/kg), euthanized at 15 mins and ex vivo imaging of multiple organs performed using IVIS imaging system. There was robust lung uptake of R11A even at the lowest (1mg/kg) dose. N=3. Red-Peptides; Blue-DAPI. Scale bar represents 20μm.

Figure 2.

Cyclization of LTPs increases serum stability and transduction. A). Serum stability studies of linear and cyclic R11A peptides at 0 and 30 minutes. B). Time course of linear and cyclic R11A stability in serum. C). Cyclization of S7A and R11A increases transduction efficiencies by ~100-fold. Human bronchial epithelial cells were incubated with linear (1μM) or cyclic peptides (100nM) and yellow fluorescent live-dead stain, and intensity of Cy5.5 fluorescence evaluated on live cells (yellow-fluorescence negative). Cyclic peptides had an ~10-fold increased fluorescence as compared to the linear counterparts at 10-fold lower concentrations. Results shown are for three separate experiments with 10,000 cells/group evaluated for each experiment.

Figure 2.

Cyclization of LTPs increases serum stability and transduction. A). Serum stability studies of linear and cyclic R11A peptides at 0 and 30 minutes. B). Time course of linear and cyclic R11A stability in serum. C). Cyclization of S7A and R11A increases transduction efficiencies by ~100-fold. Human bronchial epithelial cells were incubated with linear (1μM) or cyclic peptides (100nM) and yellow fluorescent live-dead stain, and intensity of Cy5.5 fluorescence evaluated on live cells (yellow-fluorescence negative). Cyclic peptides had an ~10-fold increased fluorescence as compared to the linear counterparts at 10-fold lower concentrations. Results shown are for three separate experiments with 10,000 cells/group evaluated for each experiment.

Figure 3.

Biodsitribution of Cyclic R11A. Wild-type, 6-week-old, CD1 mice were injected with 1mg/Kg of cR11A-Cy5.5 and allowed to circulate for 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 minutes, euthanized at the end of the circulation period, and confocal micrograph images taken of organs including lungs, heart, brain, liver, kidney, and spleen. The boxed region in the 360-min lung image represents the colocalization of cR11A with FOXI-1, an ionocyte-specific marker. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20µm (N = 3).

Figure 3.

Biodsitribution of Cyclic R11A. Wild-type, 6-week-old, CD1 mice were injected with 1mg/Kg of cR11A-Cy5.5 and allowed to circulate for 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 minutes, euthanized at the end of the circulation period, and confocal micrograph images taken of organs including lungs, heart, brain, liver, kidney, and spleen. The boxed region in the 360-min lung image represents the colocalization of cR11A with FOXI-1, an ionocyte-specific marker. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20µm (N = 3).

Figure 4.

Mechanism of transduction of cR11A studies. A). FACS analysis of cR11A uptake by HBECs with or without endocytosis inhibitors. Pitstop2 significantly reduced cR11A uptake while Amiloride and Nystatin had no effect. B). Quantification confirmed a significant reduction in cR11A uptake with Pitstop2 (p<0.001), whereas Amiloride and Nystatin showed no significant changes (ns). C). 3D visualization of colocalization of cR11A and LAMP1. Arrow A: complete co-localization, B: partial co-localization, C: no co-localization. Red: cR11A-Cy5.5, Green: LAMP1, Blue: DAPI-stained nuclei. Scale bar: 3 µm. D). Confocal microscopy revealed the colocalization of cR11A with lysosomes at 0 minutes indicating initial lysosomal uptake. By 120 minutes, cR11A localized in the cytosol with minimal lysosomal overlap, demonstrating lysosomal escape. Red-cR11A; Green-LAMP1; Blue-DAPI. Scale bars:10μm.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of transduction of cR11A studies. A). FACS analysis of cR11A uptake by HBECs with or without endocytosis inhibitors. Pitstop2 significantly reduced cR11A uptake while Amiloride and Nystatin had no effect. B). Quantification confirmed a significant reduction in cR11A uptake with Pitstop2 (p<0.001), whereas Amiloride and Nystatin showed no significant changes (ns). C). 3D visualization of colocalization of cR11A and LAMP1. Arrow A: complete co-localization, B: partial co-localization, C: no co-localization. Red: cR11A-Cy5.5, Green: LAMP1, Blue: DAPI-stained nuclei. Scale bar: 3 µm. D). Confocal microscopy revealed the colocalization of cR11A with lysosomes at 0 minutes indicating initial lysosomal uptake. By 120 minutes, cR11A localized in the cytosol with minimal lysosomal overlap, demonstrating lysosomal escape. Red-cR11A; Green-LAMP1; Blue-DAPI. Scale bars:10μm.

Figure 5.

Human bronchial epithelial cells take up LTPs without colocalization with endocytosed transferrin. Bronchial cells were serum-starved, followed by incubation with transferrin-488, or Cy5.5 labeled RAN, S7A, or R11A, followed by fixation at indicated time points, and confocal microscopy performed. Cells show very little uptake of the R11A and S7A peptide at 4°C, but increasing uptake at 5 and 30 minutes, without any co-localization with the green signal of transferrin that was endocytosed into cells. Red-Peptides; Green Transferrin; Blue-DAPI. Scale bars represent 20μm. A). Linear peptide colocalization. B). Cyclic peptide colocalization. C). Quantification of relative fluoroscence.

Figure 5.

Human bronchial epithelial cells take up LTPs without colocalization with endocytosed transferrin. Bronchial cells were serum-starved, followed by incubation with transferrin-488, or Cy5.5 labeled RAN, S7A, or R11A, followed by fixation at indicated time points, and confocal microscopy performed. Cells show very little uptake of the R11A and S7A peptide at 4°C, but increasing uptake at 5 and 30 minutes, without any co-localization with the green signal of transferrin that was endocytosed into cells. Red-Peptides; Green Transferrin; Blue-DAPI. Scale bars represent 20μm. A). Linear peptide colocalization. B). Cyclic peptide colocalization. C). Quantification of relative fluoroscence.

Figure 6.

In vivo lung cell type targeting by cR11A. A). FACS analysis of lung single cells isolated from wild-type mice injected with cR11A (1 mg/Kg), RAN (1mg/Kg), or PBS. Staining with various lung cell markers revealed significantly increased uptake of cR11A in ABCA3+ ATII cells, followed by p63+ basal cells, and ionocytes compared to controls. B). Quantification of double-positive events (cR11A-Cy5.5+ and marker +) showed significant uptake in ABCA3+ cells, p63+ cells and FOXI1+ cells in the cR11A-treated group. No significant differences (ns) were observed for KRT5 or HOPX + cells. **p<0.01.

Figure 6.

In vivo lung cell type targeting by cR11A. A). FACS analysis of lung single cells isolated from wild-type mice injected with cR11A (1 mg/Kg), RAN (1mg/Kg), or PBS. Staining with various lung cell markers revealed significantly increased uptake of cR11A in ABCA3+ ATII cells, followed by p63+ basal cells, and ionocytes compared to controls. B). Quantification of double-positive events (cR11A-Cy5.5+ and marker +) showed significant uptake in ABCA3+ cells, p63+ cells and FOXI1+ cells in the cR11A-treated group. No significant differences (ns) were observed for KRT5 or HOPX + cells. **p<0.01.

Figure 7.

cR11A targets lung ATII cells, basal cells and ionocytes. Confocal micrograph of lungs from wild-type mice injected with cR11A-Cy5.5 and euthanized at 15 minutes. Robust uptake of cR11A (red) is observed in AT-II, basal cells and ionocytes, as shown by co-localization with ABCA3, P63, and FOXI1 (all green). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20µm (N = 3).

Figure 7.

cR11A targets lung ATII cells, basal cells and ionocytes. Confocal micrograph of lungs from wild-type mice injected with cR11A-Cy5.5 and euthanized at 15 minutes. Robust uptake of cR11A (red) is observed in AT-II, basal cells and ionocytes, as shown by co-localization with ABCA3, P63, and FOXI1 (all green). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20µm (N = 3).

Figure 8.

In vitro antiviral activity of cR11A-siRNA-S1, and cR11A-E2 against SARS-CoV-2 in human bronchial epithelial cell line. A). Structural representation of the cR11A along with the DTME linker linking to the siRNA represented by double-strands. B). Table showing viral titers from human bronchial epithelial cells treated with the cR11A-siRNA conjugates for 24 hours prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus and the respective EC90 values, along with the EC90 value for remdesivir. C). SARS-CoV-2 viral titers plotted for cR11A-S1, cR11A-E2, and remdesivir against the virus only control. All infections and assays done in triplicate.

Figure 8.

In vitro antiviral activity of cR11A-siRNA-S1, and cR11A-E2 against SARS-CoV-2 in human bronchial epithelial cell line. A). Structural representation of the cR11A along with the DTME linker linking to the siRNA represented by double-strands. B). Table showing viral titers from human bronchial epithelial cells treated with the cR11A-siRNA conjugates for 24 hours prior to infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus and the respective EC90 values, along with the EC90 value for remdesivir. C). SARS-CoV-2 viral titers plotted for cR11A-S1, cR11A-E2, and remdesivir against the virus only control. All infections and assays done in triplicate.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).