Submitted:

04 January 2024

Posted:

05 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of art

2.1. Roofs technologies

2.1.1. Photovoltaic and thermal panels integrated in the roof

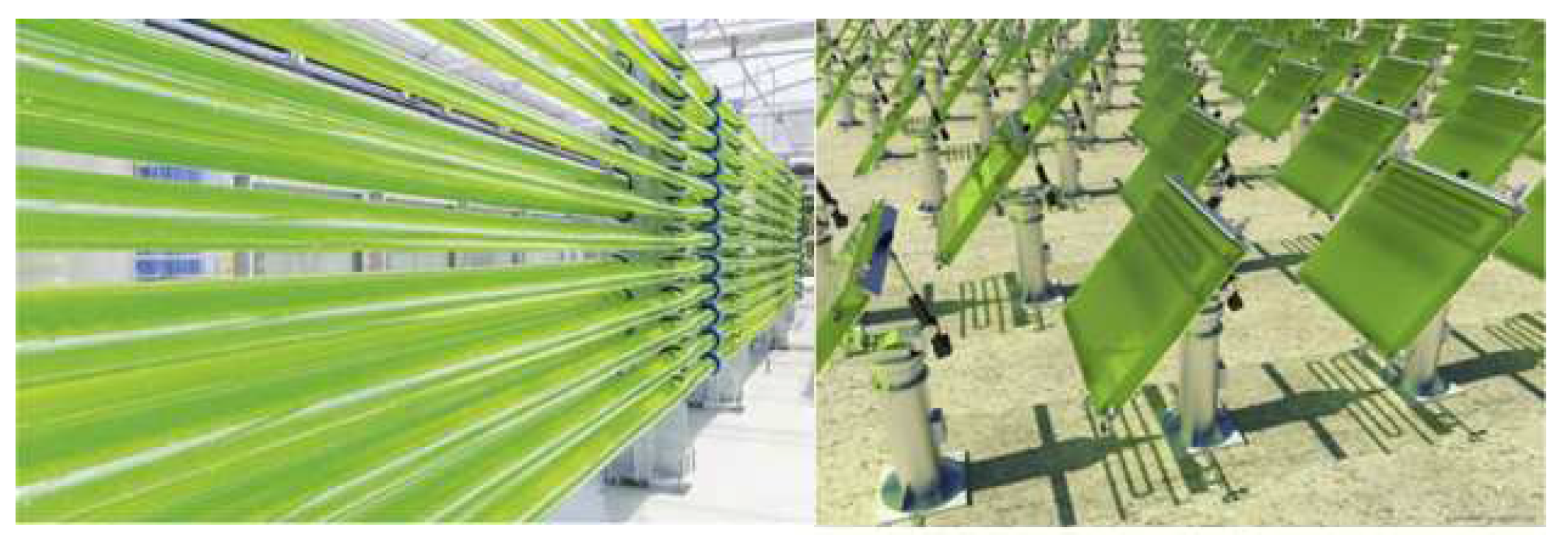

2.1.2. Photobioreactors roofs

2.1.3. Building-integrated wind turbines

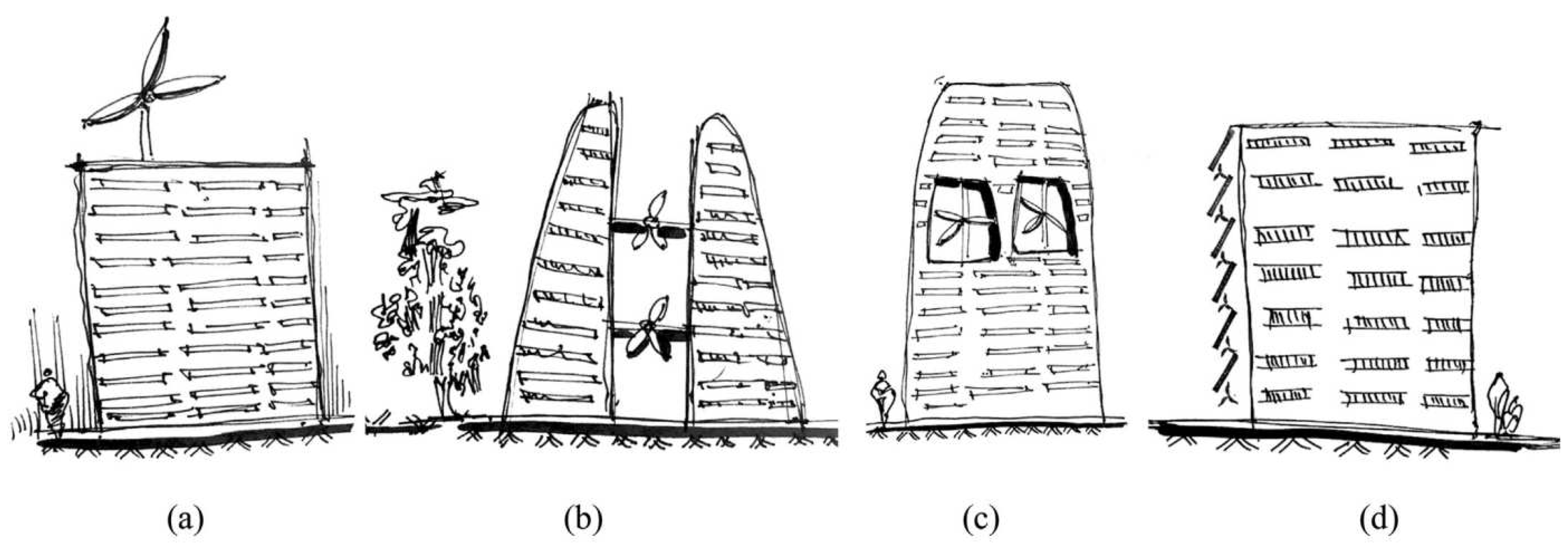

2.1.4. Hybrid solar-wind systems

2.2. Facades technologies

2.2.1. Solar paint wall

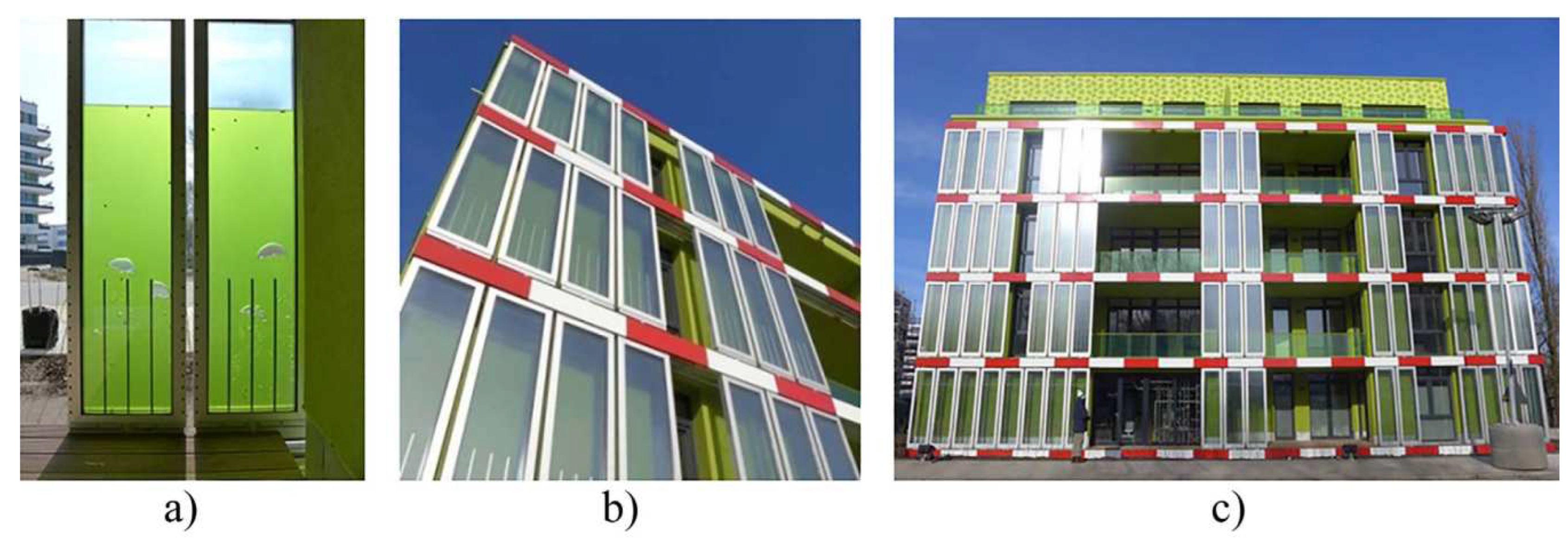

2.2.2. Photobioreactors facade panels

2.2.3. Microbial biophotovoltaic wall technology

2.3. Windows technologies

2.3.1. Photovoltaic glasses

2.3.2. Triboelectric nanogenerators glasses

3. Discussion: SWOT analysis systems coupling in the building envelope

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-purpose: Both the electricity and heat energy can be obtained from the same system [44] PVT system has better efficiency than the PV system [8] Flexible and efficient [44] Can help reduce fossil fuel consumption [3] Has wide application area [44] Inexpensive and convenient [44] It keeps the architectural uniformity on roofs [45] Installation cost may be reduced for the need of only one system to be installed instead of two systems [45] Lower space utilization than the two systems alone [45] Reduce the temperature of the photovoltaic panels and take advantage of the excess heat [8] Abundance of raw materials [46] |

The cost of installation can be relatively high [44] The absence of the sun at night and cloudy days [47] PV/T systems have a intermittent energy production depending on weather [3] Need for an energy storage system to address the issues of intermittency and meet local energy needs [4] Accumulated dust can reduce power output and therefore system efficiency [4] |

Improving the optical properties of the working fluid can improve efficiency [8] The better the performance of the PVT system, the higher the transmittance of visible light and solar infrared rays absorbed. [8] The thermal energy generated by the system can be convert to electrical energy by the Peltier effect [33] It can be integrated into a building and forms a part of the building (BIPVT) [48] PV/T systems integrated into the building envelope avoid additional land use [5] Can be integrated with other energy sources for enhanced efficiency [3] Can be coupled to another electricity production system [33] Applying PV systems to the roof can markedly decrease the heat flux through the roof [6] |

Planning of site and orientation [4] Exposure to the elements and risk of premature deterioration [46] The efficiency of the modules varies significantly depending on weather conditions, climate, and the presence of shading effects. [6] and [46] Thermal losses within the photovoltaic panel [33] Overproduction of electricity [46] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generate energy [9] Algae can grow in seawater, wastewater, or harshwater [9] Algae have a high rate of growth (higher than most other productive crops) [9] More microalgae species can be developed (compared to an open pond) [9] Can produce 5 to 10 times higher yields per aerial footprint (than open pond) [9] Biogas production [9,33] Significantly decrease the building’s energy demands [33] Biomass production high-efficiency (compared to open pond) [9,33] Preventing culture evaporation [33] Effective light distribution [33] Climate change resistance [33] Tubular PBRs do not need a specific orientation for good exposure to solar light [10] Lower environmental impact than solar panel [9] Need less area (compared to an open pond)Lower water consumption (compared to an open pond)Less weather dependent (compared to an open pond)Work also during the nightAvoid bacterial and dirt contamination [49] PBR design permits more effective use of light (compared to open ponds) [49] |

An ideal temperature range is required for algae to bloom (being 16 to 27°C) [9] Required indirect, middle-intensity light levels [9] Nutrients required (salinity, CO2, ammonia, phosphate...) [9] Specific pH required (7-9 is ideal) [9] Air circulation need (harvest CO2) [9] Initially require a higher investment (compared to an open pond) [49] Required a high control of algae cultivation [49] Lack of experience in building applications [18] Negative net present values (NPV) after 15 years [11] |

Algae production can be used for wastewater treatment [50] Oxygen production [50] CO2 capture capacity (absorbing as much as 85% of CO2 content) [50] The yield of oil production far exceeds that of soybeans (by 60 times) or palm (by 5 times) [50] Heat production (biogas-to-electricity conversion in the generator) [11] Recovering waste heat as steam supply [11] Able to produce food grade biomass (compared to open pond) [9] Able to produce by-products [33] Can produce light energy [33] Provide thermal insulation [33] |

A necessity to adapt algae species according to climate and location [18] Specific and tight regulations for real-life building [18] Need to study the lifetime of the system [18] Need to study the maintenance and cleaning requirements [18] Higher investment and production costs (compared to an open pond) [18] Not economically viable for the moment [18] Oxygen in the water affect directly the cultivation [9] Excessive light intensity can inhibit the photosynthesis process [33] Face a lack of natural light during the night that causes biomass losses (25%) [33] Risks of poor, or, non-performance [17] Other renewables produce more energy [17] Human health risks with some algae species [17] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced wind farms needs (off-grid system) [9] Limiting cables connection and infrastructure for electricity delivery [9] Decrease energy losses (off-grid system) [9] Wind wall are flexible systems (wind harvesting panels are demountable) [51] VAWTs wind walls are able to capture incoming wind from any direction (unlike HAWTs) [22] VAWTs wind walls do not need to be oriented [22] VAWTs wind walls can take advantage of turbulences [22] The noise is almost zero for normal winds and even for low winds with VAWTs [22] For VAWTs no yaw mechanisms are needed [22] VAWTs have lower wind startup speeds than typical HAWTs [22] |

Vibration and noise problems [22] Classic HAWTs need to be always aligned to the wind direction [22] VAWTs have decreased efficiency (than common HAWTs) [22] VAWTs have rotors located close to the ground where wind speeds are lower [22] VAWTs cannot take advantage of higher wind speeds above [22] Intermittent energy production depending on weather [22] |

Small wind turbines may be coupled to street lighting systems (smart lighting) [22] Can be paired with a photovoltaic system Can contribute to aesthetic design for the buildings (in double skin facade for instance) [22] VAWTs can be located nearer the ground [22] VAWTs may be built at locations where taller structures are prohibited [22] Wind walls minimizing glare circulating air [51] Wind walls control radiation [51] Wind walls provide insulation [51] Wind walls collection of heat [51] Wind walls generate energy [51] Wind walls sequester emissions [51] Wind walls provide aesthetic [51] Wind walls increase property value [51] |

Wind turbines have a negative response from the public [52] Visual pollution [52] Turbulent and low-velocity wind conditions in urban areas [52] Adjacent buildings can cause wind shadow [53] Urban terrain roughness is high [53] If close to the ground, turbines between 2 buildings may cause discomfort for pedestrians (high wind speed) [23] Heat effects may affect the turbine (buoyancy needs to be considered) [23] Turbines between 2 buildings need early urban planning in the design of neighboring buildings [23] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Produce electricity [25,26,27] Does not require any fossil fuel [25] Has greater potential to reduce carbon dioxide emissions than the 2 systems alone [25,26,27] Lower climate condition dependence than the 2 systems alone [27] Need less area than 2 separated systemsBetter LCOE (Levelized cost of electricity) [27] More environmental-friendly than the 2 systems alone [25,26] Better in terms of payback time than the 2 systems alone [27] More efficient than the 2 separated systems [27] The wind turbine can also rotate during the nighttime and improve the economics of the system by more electricity generation [25] |

Require a larger initial investment than a unique system (solar panels, wind turbines and energy storage) [27] Climate condition dependence[27] Intermittent production [27] Need more area than a unique solar or wind system [27] |

Coupled with a solar chimney, using mirrors can increase the heat gain of the system [25] Add a wind turbine and a solar chimney to a PV/T panels system reduce payback period [25] Add a wind turbine and a solar chimney to a PV/T panels system increase the potential to reduce CO2 emissions [25] Low operation and maintenance cost [25] Produce low noise [25] Can be equipped with a storage system for electricity and heat [25] Excess power can be sold [26] |

May not be sufficient to cover all needs [26] May not fit into areas with limited space [27] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| High conversion efficiency [54] Produce clean energy [31] Gas phase water splitting is predicted to require less energy [31] Efficient light absorption with minimal light scattering [30] Adaptable to many surfaces [30] [55] Provide aesthetic integration into the building envelope [30] [55] Easy and quick application with a simple brush [56] Low cost technology [55] It deliver an adjustable electrochemical performance [57] Environmentally friendly and emits no ozone-depleting substances after use [55] |

Very low efficiency [58] Doubt regarding the sustainability of this technology [55] |

A large moisture adsorption capacity for binding water molecules [30] It should be a semiconductor with good conductivity [30] Providing light adsorption capabilities [30] Feature high catalytic activity [30] Utilize the standard inverter technology employed by traditional solar cells for connecting to the electricity grid network [55] |

Competition with more efficient and reliable traditional solar cells [58] Very recent technology that necessitates additional studies to ascertain its viability [58] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generate energy [9] Algae can grow in seawater, wastewater, or harsh water [9] Algae have a high rate of growth (higher than most other productive crops) [9] Several levels of valorization (biogas, biofuel, bioethanol) [9] Work also during the night [33] Biomass production [33] Biogas production [33] Significantly decrease the building’s energy demands [33] Preventing culture evaporation [33] Effective light distribution [33] Climate change resistance [33] Lower environmental impact than a solar panel [9] |

Higher facade costs (multiplied by 10 for the BIQ Building) [33] An ideal temperature range is required for algae to bloom (being 16 to 27°C) [9] Required indirect, middle intensity light levels [9] Nutrients required (salinity, CO2, ammonia, phosphate...) [9] Specific pH required (7-9 is ideal) [9] Air circulation need (harvest C2) [9] Required a high control of algae cultivation [49] Lack of experience in building applications [18] |

Slidable PBR panels create a thermally controlled microclimate around the building [17,51] Slidable PBR panels reduce unwanted external sound transmission [17,51] Provide dynamic shading [17,51] Increase the energy-saving potential of the building [59] Maximizing daylight [51] Providing view [51] Circulating air [51] Control radiation [51] Rejection of heat [51] Sequestrating emissions [51] Absorbing emissions [51] Provide aesthetic [51] Increase property value [51] Bioluminescent algae can replace artificial lighting by night [59] Reduce wind effects [33] |

Need to study its adaptability to face natural and fire hazard [33] Design affects the microalgae growth and productivity (orientation, thickness, material, temperature, light intensity, CO2, nutrient, and water) [10] Real performances likely unknown (only one experimental application: BIQ Building) |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very great capacity for growth [36] Work in the dark (for several hours even if the range is lower) [36] Improving water-use efficiency (considering the minor volume of starting culture) [36] Using a gel (which replaces the liquid reservoir normally used in conventional BPV devices [36] Great power output compared with conventional liquid culture-based BPV devices [36] Electrical output can be sustained for more than 100 hours (paper-based MFCs can only operate for 1 h) [36] Can provide a short burst of power [36] Disposable and environmentally friendly power [36] |

Low electricity production [36] Damage possibility of cyanobacteria cells during printing [36] Power output is less in the dark that in the light [36] Printed CNT cathode is a limiting factor in microbial fuel cell performance [36] |

Feasibility of using an inexpensive commercial inkjet printer without (really) affecting cell viability [36] Paper is an inexpensive widespread material and biodegradable [36] The potential of miniaturization for cyanobacteria culture [36] Use of high-performance CB could increase the power output [36] Use of desert CB might reduce the material and energy costs of scale-up [36] Could be developed for bioenergy wallpaper [36] Hydrogel between anode and cathode would improve the power output (by exposing the cathode to more air) [36] |

Solar energy is an intermittent energy source (inevitably drops in low light) [36] Production depends greatly on external conditions (location, weather, time of the day, and seasons of the year) [36] Optimizing cell design [36] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| It obtains clean electric energy [37] Realizing active energy saving of windows [60] The implementation of PV glazing and shading devices has the potential to decrease lighting loads and electricity consumption [6] Sustainable electricity production system [6] Integrated glazing reduces the environmental and economic impact of buildings [5] The CoPVTG device results to provide always the highest energy yield [61] Provide a uniform daylight distribution [6] Provide solar contribution control [6] Economically feasible [6] It can meet the needs of natural lighting while satisfying architectural aesthetics [37] CoPVTG devices provide higher energy yield than CoPEG [61] CoPVTG systems provide exploitable hot air [61] |

The performance of BIPV depends highly on the climate and location site [6] Intermittent electricity production depending on weather conditions [6] Building orientation affect performances of the system [6] |

Providing adequate ventilation (BIPV windows) [4] Reduce building cooling load or heat load [6,60] Can be installed as a facade window and balustrade or sloped as an exterior element [5] They are capable to insulate the building [61] PV windows demonstrated superior energy-saving performance compared to conventional insulating glass windows [62] PV insulating glass units have greater energy saving potential than PV double skin facades [62] Low-E coatings have the potential to minimize heat transfer through radiation [6] |

Colored modules can lead to significant efficiency losses depending on the materials and colors used [5] The timeframe for recovering energy investment and the associated uncertainty in greenhouse gas emissions remains unclear [5] Competition with traditional roof PV systems |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convert ambient mechanical energy (from wind impact and water droplets) into electricity [39] Can be used for a self-powered smart window system [39] TENGs are transparent (don’t cover or sacrifice surface area window) [39] High transmittance of over 60% [39] Low water contact angle hysteresis with SLIPS addition [41] More efficient energy conversion with SLIPS addition [41,42] Anti-fouling, anti-icing, and drag reduction with SLIPS addition [41,42] Sustainable and renewable energy [63] Low cost [63] Lightweight [63] Take advantage of both wind and rain [39] Solid–solid/liquid–solid convertible TENG increases the conditions under which energy can be produced [40] |

Very low power output compared to conventional systems such as PV panels and wind turbines [41] Climate conditions dependence [39] Temperature and humidity may affect the performances of this system [39] |

Act as a rain-sensor to prevent rainwater from entering the house [41] Integrating an electrochromic device (ECD) (change color or opacity) [39] Can be paired with other electricity production system such as PV glasses [64] Can be used as a sensor for self-powered window closing system [41] |

Lower durability [65] Limited short circuit output current [65] Competition with more efficient and reliable systems |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy production on sunny days and rainy days [64] PV/TENG hybrid systems represent a great potential to complement vulnerable aspects of individual PV and TENG components [64] Good transparency (visible light transmittance (VLT) of 23.49%), color rendering (CRI of 92), and window insulation [64] Convert ambient mechanical energy (from water droplets) into electricity [39] Low water contact angle hysteresis with SLIPS addition [41] More efficient energy conversion with SLIPS addition [41] Anti-fouling, anti-icing, and drag reduction with SLIPS addition [41] Sustainable and renewable energy [63] Low cost [63] Lightweight [63] |

Very low power output [41] Specific transmittance (blue layer) [64] |

Shading effects [64] Hampered the heat transfer [64] Decreased the air temperature [64] Greenhouse applications (high plant growth factor of 25.3%) [64] |

Climatic conditions dependence [65] Lower durability [65] Limited short circuit output current [65] |

4. Conclusions

References

- Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie. Climat Air et Énergie; ADEME Editions, 2018. https://librairie.ademe.fr/changement-climatique-et-energie/1725-climat-air-et-energie-9791029712005.html.

- Ministères Écologie Énergie Territoires. Energie dans les bâtiments, 2021. https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/energie-dans-batiments.

- Olabi, A.G.; Shehata, N.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Heikal, L.A.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Shah, S.K.; Sayed, E.T. Progress in Solar Thermal Systems and Their Role in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Energies 2022, 15, 9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodapally, S.N.; Ali, M.H. A Comprehensive Review of Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Technologies, Architecture, and Its Applications to Improved Efficiency. Energies 2023, 16, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.E.; Erban, C.; Heinrich, M.; Eisenlohr, J.; Ensslen, F.; Neuhaus, D.H. Review of technological design options for building integrated photovoltaics (BIPV). Energy and Buildings 2021, 231, 110381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşer, A.; Koyunbaba, B.K.; Kazanasmaz, T. Thermal, daylight, and energy potential of building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) systems: A comprehensive review of effects and developments. Solar Energy 2023, 251, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhani, R.; Ennawaoui, C.; Hajjaji, A.; Boughaleb, Y.; Rivenq, A.; El Hillali, Y. Photovoltaic-thermoelectric (PV-TE) hybrid system for thermal energy harvesting in low-power sensors. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maythem, A.; Al-Shamani, A.N. Using Hybrid System Photovoltaic Thermal/Phase Change Materials/Thermoelectric (PVT/PCM/TE): A Review. Forest Chemicals Review 2022, pp. 1365–1400. http://www.forestchemicalsreview.com/index.php/JFCR/article/view/1241.

- Biloria, N.; Thakkar, Y. Integrating algae building technology in the built environment: A cost and benefit perspective. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2020, 9, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrayies, G.M. Microalgae: prospects for greener future buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 81, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A. Cost and Benefit Analysis of Implementing Photobioreactor System for Self-Sustainable Electricity Production from Algae. Master work 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohutskyi, P.; Bouwer, E. Biogas production from algae and cyanobacteria through anaerobic digestion: a review, analysis, and research needs. Advanced biofuels and bioproducts 2013, 873–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, R.; Pandey, A.K.; Ranganathan, P.; Singh, S.; Udayan, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Hoang, A.T.; Chilakamarry, C.R.; Kim, S.H.; Sim, S.J. Design and applications of photobioreactors-A review. Bioresource technology 2022, 126858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, P.M.; Thomas-Hall, S.R.; Stephens, E.; Marx, U.C.; Mussgnug, J.H.; Posten, C.; Kruse, O.; Hankamer, B. Second generation biofuels: high-efficiency microalgae for biodiesel production. Bioenergy research 2008, 1, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Berzin. Photobioreactor and process for biomass production and mitigation of pollutants in flue gases, 2002. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20050260553A1/en?oq=+patent+US+20050260553.

- Araji, M.T.; Shahid, I. Symbiosis optimization of building envelopes and micro-algae photobioreactors. Journal of Building Engineering 2018, 18, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Biloria, N.; Ralph, P. The technical issues associated with algae building technology. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation 2020, 38, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncel, S.; Köse, A.; Öncel, D. Façade integrated photobioreactors for building energy efficiency. In Start-Up Creation; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 237–299. [CrossRef]

- Schott, A. Tubular Glass Photobioreactors: Bringing Light to Algae. SCHOTT, Mitterteich 2015. https://media.schott.com/api/public/content/3975a579843c4251a9d4777201b19fb2?v=b60e4a2c&download=true.

- Drew, D.; Barlow, J.; Cockerill, T. Estimating the potential yield of small wind turbines in urban areas: A case study for Greater London, UK. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2013, 115, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.S.; Su, Y.M.; Wen, C.Y.; Juan, Y.H.; Wang, W.S.; Cheng, C.H. Estimation of wind power generation in dense urban area. Applied Energy 2016, 171, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, M. Small vertical axis wind turbines for energy efficiency of buildings. Journal of Clean Energy Technologies 2016, 4, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanli, S.; Hu, G.; Kwok, K.C.; Fletcher, D.F. Utilizing cavity flow within double skin façade for wind energy harvesting in buildings. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2017, 167, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Park, J. A new building-integrated wind turbine system utilizing the building. Energies 2015, 8, 11846–11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, K.; Ebrahimi, M.; Lahonian, M.; Babamiri, A. Micro-scale heat and electricity generation by a hybrid solar collector-chimney, thermoelectric, and wind turbine. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 53, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deymi-Dashtebayaz, M.; Baranov, I.V.; Nikitin, A.; Davoodi, V.; Sulin, A.; Norani, M.; Nikitina, V. An investigation of a hybrid wind-solar integrated energy system with heat and power energy storage system in a near-zero energy building-A dynamic study. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 269, 116085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdian, M.H.; Sohani, A.; Pedram, M.Z.; Sayyaadi, H. An optimal strategy for application of photovoltaic-wind turbine with PEMEC-PEMFC hydrogen storage system based on techno-economic, environmental, and availability indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 384, 135499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlou, Y.; Abdelghani, H.; Mohammed, A.; Mohammed, I. Système compact de production d’énergie renouvelable hybride PV-Eolien, 10, 2021. https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/fr/detail.jsf?docId=WO2021137680.

- Elçiçek, H. Determination of critical catalyst preparation factors (cCPF) influencing hydrogen evolution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 3824–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeneke, T.; Dahr, N.; Atkin, P.; Clark, R.M.; Harrison, C.J.; Brkljaca, R.; Pillai, N.; Zhang, B.Y.; Zavabeti, A.; Ippolito, S.J.; others. Surface water dependent properties of sulfur-rich molybdenum sulfides: electrolyteless gas phase water splitting. ACS nano 2017, 11, 6782–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, C.J.; Hisatomi, T.; Domen, K.; Metha, G.F. Gas phase photocatalytic water splitting of moisture in ambient air: Toward reagent-free hydrogen production. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2020, 401, 112757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, D.; Yang, Y.; Feng, S.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Shen, Y.; others. ZnIn2S4-based photocatalysts for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution via water splitting. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2023, 475, 214898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, M.; Mahdavinejad, M.; Azari, R. Thermal and energy performance of algae bioreactive façades: A review. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 28, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaei, M.; Mahdavinejad, M. Probable cause of damage to the panel of microalgae bioreactor building façade: Hypothetical evaluation. Engineering Failure Analysis 2019, 101, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, A.J.; Bombelli, P.; Scott, A.M.; Philips, A.J.; Smith, A.G.; Fisher, A.C.; Howe, C.J. Photosynthetic biofilms in pure culture harness solar energy in a mediatorless bio-photovoltaic cell (BPV) system. Energy & Environmental Science 2011, 4, 4699–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, M.; Fantuzzi, A.; Bombelli, P.; Howe, C.J.; Hellgardt, K.; Nixon, P.J. Electricity generation from digitally printed cyanobacteria. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cai, B.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Study on natural lighting and electrical performance of louvered photovoltaic windows in hot summer and cold winter areas. Energy and Buildings 2022, 271, 112313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y. Design, development and characterisation of a Building Integrated Concentrating Photovoltaic (BICPV) smart window system. Solar Energy 2021, 220, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.H.; Lin, L.; Yang, P.K.; Wang, Z.L. Motion-driven electrochromic reactions for self-powered smart window system. ACS nano 2015, 9, 4757–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Cho, H.; Yong, H.; Heo, D.; Rim, Y.S.; Lee, S. Versatile surface for solid–solid/liquid–solid triboelectric nanogenerator based on fluorocarbon liquid infused surfaces. Science and technology of advanced materials 2020, 21, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Lu, Y.; Cao, X. Self-powered rain droplet sensor based on a liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2022, 98, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, R.; Orlando, R.J.; Manica, R.; Liu, Q. Liquid-solid triboelectric nanogenerators for a wide operation window based on slippery lubricant-infused surfaces (SLIPS). Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 439, 135688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Park, J.G.; Kim, K.N.; Thokchom, A.K.; Bae, J.; Baik, J.M.; Kim, T. Transparent-flexible-multimodal triboelectric nanogenerators for mechanical energy harvesting and self-powered sensor applications. Nano Energy 2018, 48, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan Volkan, Ö.; YEŞİLYURT, M.K.; YILMAZ, E.Ç.; ÖMEROĞLU, G. Photovoltaic thermal (PVT) solar panels. International journal of new technology and research 2016, 2, 13–16. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/ 30641980/Photovoltaic_Thermal_PVT_Solar_Panels.

- Jia, Y.; Alva, G.; Fang, G. Development and applications of photovoltaic–thermal systems: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 102, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, E.; Belmonte, L.M.; Morales, R.; Somolinos, J.A. A Strategic Analysis of Photovoltaic Energy Projects: The Case Study of Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouhi, A.; Rehman, S.; Buker, M.S.; Said, Z. Recent technical approaches for improving energy efficiency and sustainability of PV and PV-T systems: A comprehensive review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 56, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Yang, H.; Yan, Z.; Ansah, M.K. A review of designs and performance of façade-based building integrated photovoltaic-thermal (BIPVT) systems. Applied thermal engineering 2021, 182, 116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHOTT. Open Raceway Pond, Plastic Bags or Glass Tube Photobioreactor, 2018. https://knowledge.schott.com/art_resource.php?sid=qhwy.2rri80a.

- Proksch, G. Growing sustainability-integrating algae cultivation into the built environment. Edinburgh Architectural Research Journal 2013, 33, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Valladares, O.P.; Peña, D.M. Sustainability performance by ten representative intelligent Façade technologies: A systematic review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 52, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.K.; Kang, B. Integrating a wind turbine into a parking pavilion for generating electricity. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 32, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.L. Building mounted wind turbines and their suitability for the urban scale—A review of methods of estimating urban wind resource. Energy and Buildings 2011, 43, 1852–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, P.; Noh, J. Photocatalytic Water Splitting: How Far Away Are We from Being Able to Industrially Produce Solar Hydrogen? Molecules 2022, 27, 7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Baral, R. Solar Photovoltaic Paint for Future: A Technical Review. Advanced Journal of Engineering 2022, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.A.; Basit, M.A.; Yoon, S.J.; Lee, G.J.; Lee, M.D.; Park, T.J.; Kamat, P.V.; Bang, J.H. Revival of solar paint concept: air-processable solar paints for the fabrication of quantum dot-sensitized solar cells. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 17658–17670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Albaqami, M.D.; Bahajjaj, A.A.A.; Ahmed, F.; Din, E.; Arifeen, W.U.; Ali, S. Wet-Chemical Synthesis of TiO2/PVDF Membrane for Energy Applications. Molecules 2022, 28, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, M.P.; Lightcap, I.V.; Kamat, P.V. Sun-believable solar paint. A transformative one-step approach for designing nanocrystalline solar cells. ACS nano 2012, 6, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H. A feasibility study of an algae façade system. International Conference on Sustainable Building Asia, 2013, pp. 8–10. https://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB_DC26782.pdf.

- Wang, H.; Lin, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Cheng, Y. Study on indoor adaptive thermal comfort evaluation method for buildings integrated with semi-transparent photovoltaic window. Building and Environment 2023, 228, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Buonomano, A.; Chang, R.; Forzano, C.; Giuzio, G.F.; Mondol, J.; Palombo, A.; Pugsley, A.; Smyth, M.; Zacharopoulos, A. Modelling and simulation of building integrated Concentrating Photovoltaic/Thermal Glazing (CoPVTG) systems: Comprehensive energy and economic analysis. Renewable Energy 2022, 193, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Peng, J.; Li, N.; Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Lu, T. Comparison of energy performance between PV double skin facades and PV insulating glass units. Applied energy 2017, 194, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, R.; Kumar, C.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Pillai, S.C. Opportunities and challenges in triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) based sustainable energy generation technologies: a mini-review. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2021, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Yu, L.; Fahlman, M.; Li, X.; Murto, P.; Chen, J.; others, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Semitransparent polymer solar cell/triboelectric nanogenerator hybrid systems: Synergistic solar and raindrop energy conversion for window-integrated applications. Nano Energy 2022, 103, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Tripathi, R.K.; Gupta, M.K.; Dzhardimalieva, G.I.; Uflyand, I.E.; Yadav, B. 2-D self-healable polyaniline-polypyrrole nanoflakes based triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered solar light photo detector with DFT study. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 600, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).