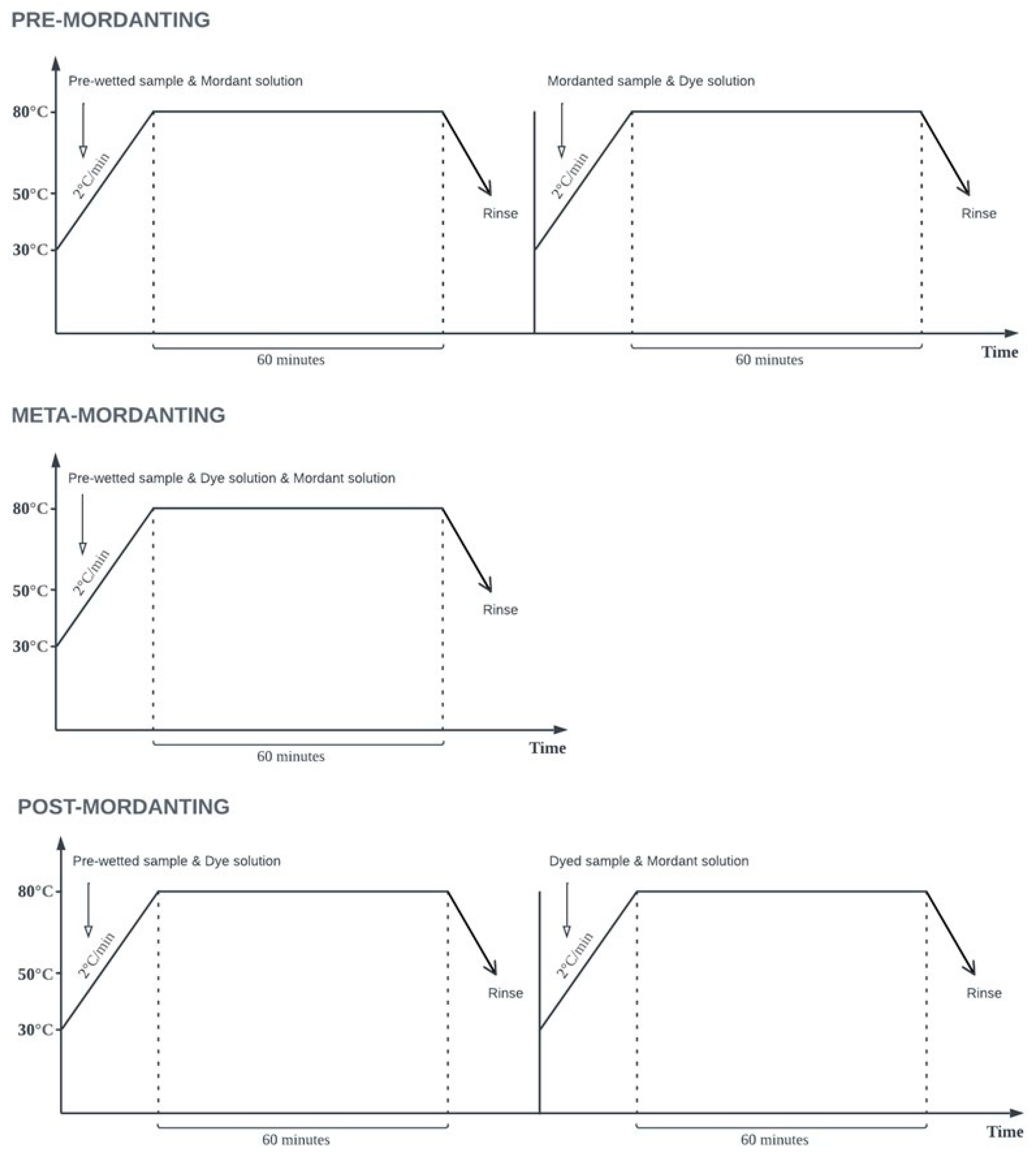

The results of dyeing experiments are presented in two following sub-sections. First, dyeing experiments without mordanting procedure are presented. These experiments are done mainly as a function of increasing dye concentration. Second, the dye concentration is set to a low level and the combination with different mordants using different procedures is presented.

3.1. Dyeing without mordant

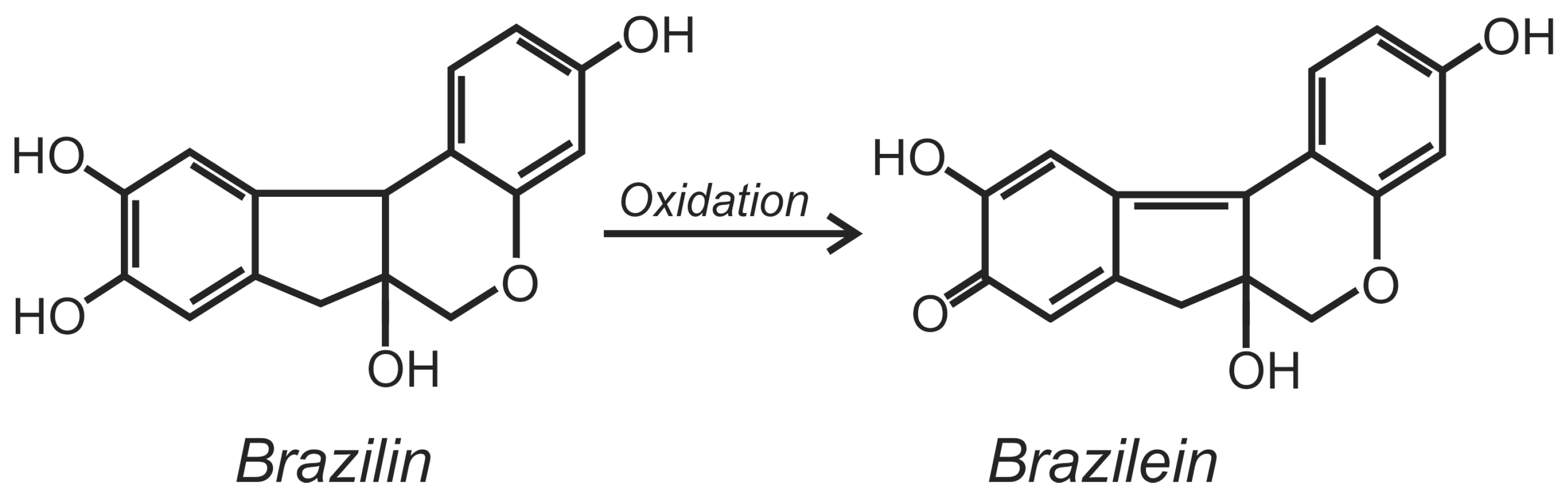

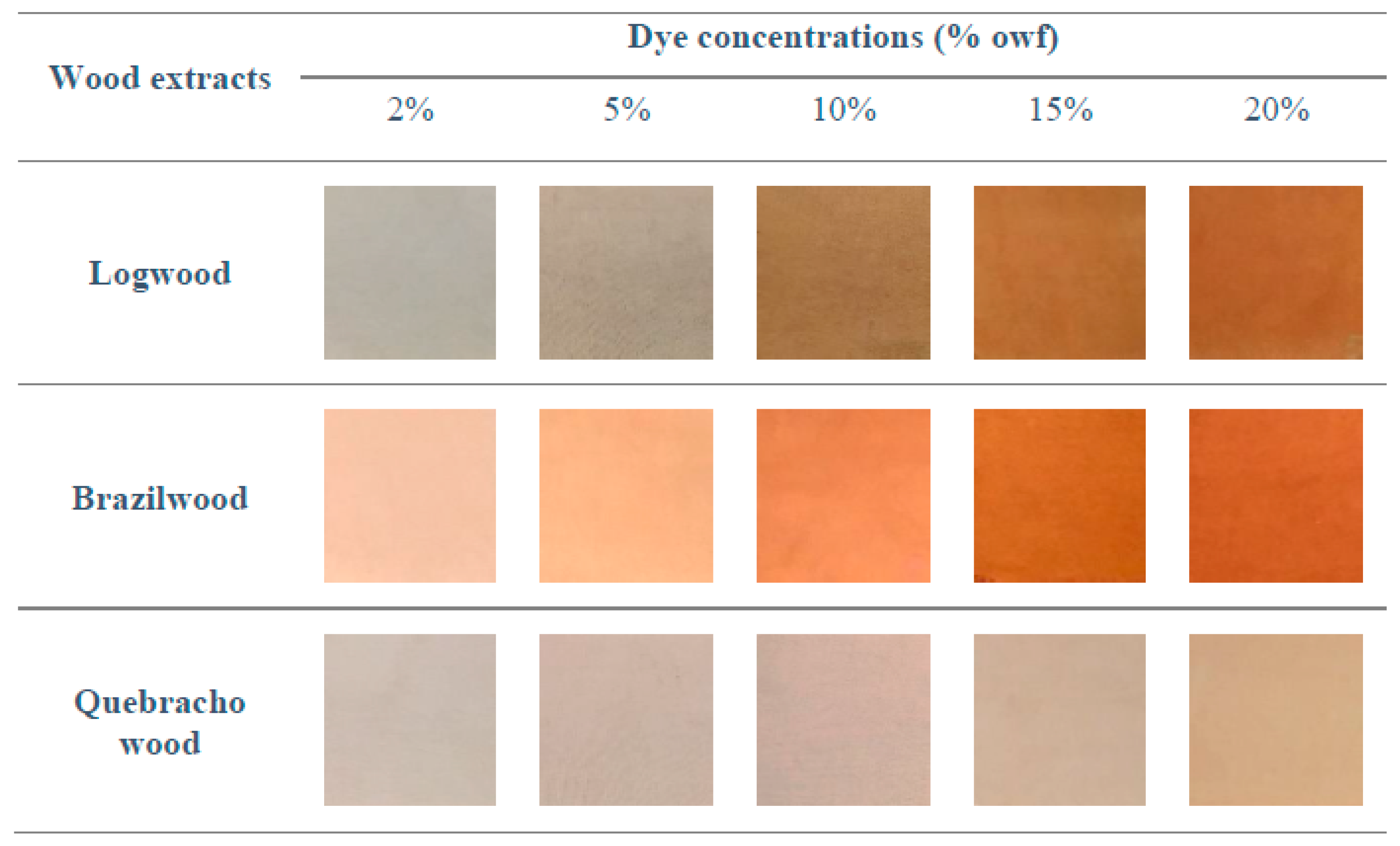

The dye application without mordant are done on cotton with increasing dye concentration from 2 to 20 %owf. The color impression of realized cotton samples are documented by photographs and presented in

Figure 6. As expected, the color intensity increases with increasing dye concentration. The coloration can be best described as different shades of red and brown. Additional to the description of the visual appearance, the coloration is investigated by spectroscopic measurements and color measurements.

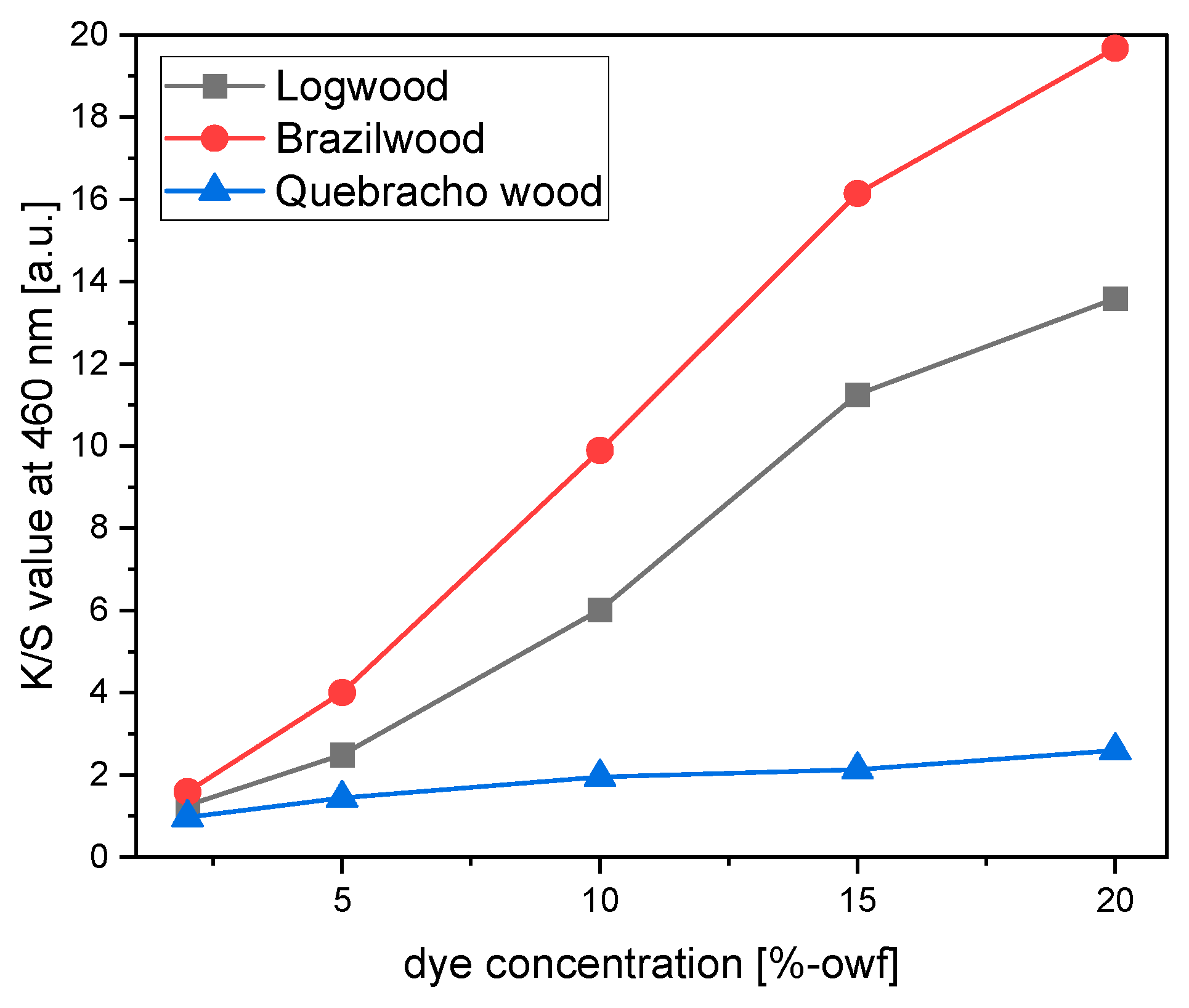

As a general trend, samples dyed with Logwood, Brazilwood, and Quebracho wood showed a maximum absorption wavelength at around 460nm. For this, the reflection values were recorded at 460nm and transferred to K/S values (

Figure 7). Along with the deeper shade of the dyed samples, K/S values moved upwards when extract concentrations are increased.

For logwood and Brazilwood, a rapid increase in K/S value occurred from 5% to 15% extract concentrations. At over 15%, color strength continued increasing, but at a lower rate. This is likely due to decreased colorant absorption rate on cotton fiber. When the extract concentration surpassed 15% owf, the dye in the fabric became saturated. From this point, adding more dyestuff had less effect on the color yield than before. At 20% concentration, the K/S value had not yet achieved equilibrium.

The K/S values of Quebracho wood increased with a growth in the percentage of the applied dye too. However, it displayed a smaller increase compared to Logwood and Brazilwood. Their K/S values were initially close to each other. However, at 20% dye concentration, the color strength of Logwood and Brazil samples were above fivefold and sevenfold higher than that of Quebracho wood respectively.

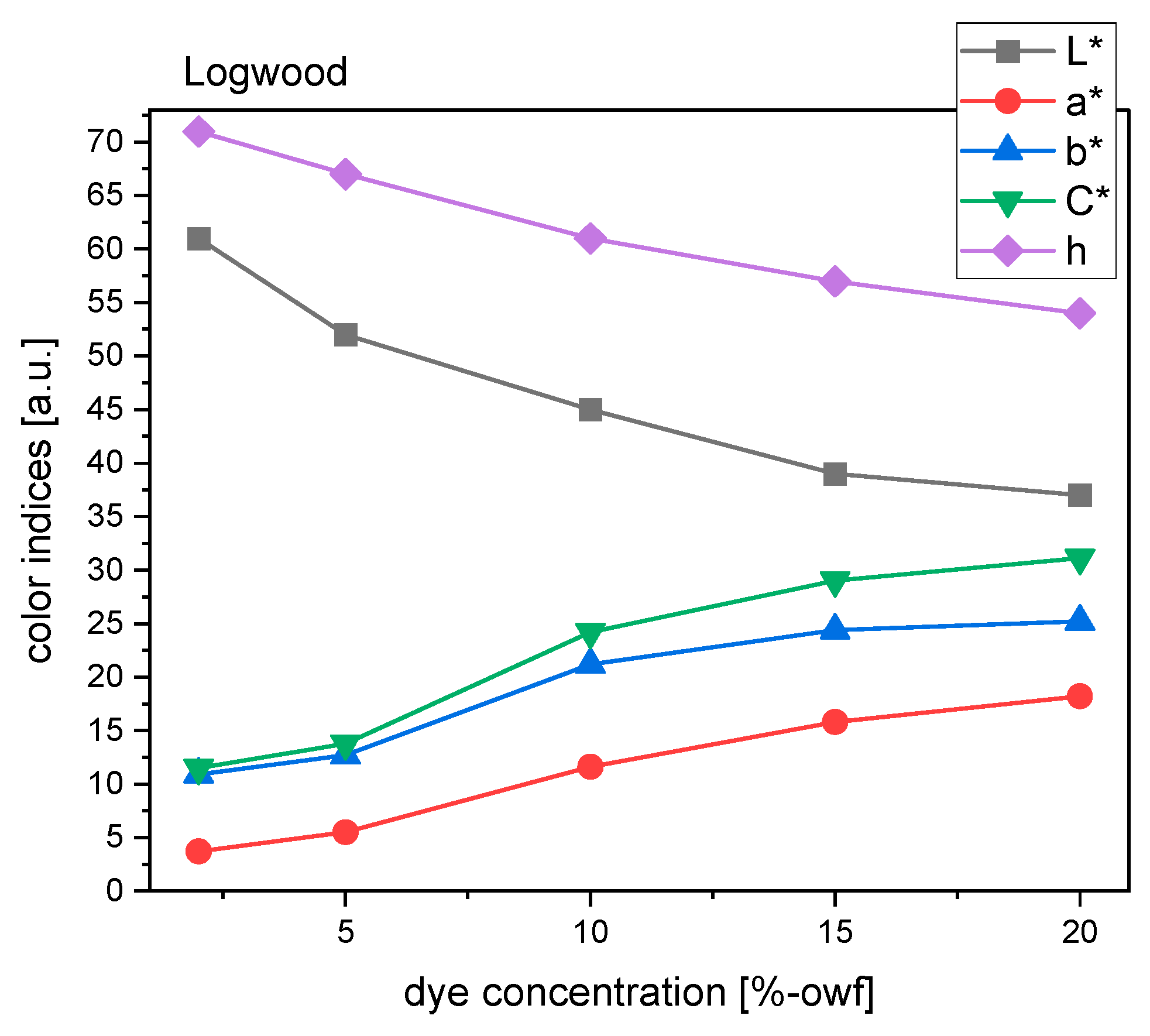

For description of color properties, the L*a*b* values are determined [

40]. L*a*b* values of dyed samples were presented as function of applied dye concentration (

Figure 8 to

Figure 10). At first glance on the L* plane, the reduced value of lightness denoted darker shade of the color, meaning that application of more dyestuff generated darker shades. For Logwood and Brazilwood, luminance fell by more than 22 units when the dye concentrations increased from 2% to 20%. This demonstrated that the visual appearance of samples changed from light- to dark-colored, as can be seen also in

Figure 6. Meanwhile, the fall in L* value of Quebracho wood dye was just over 10 units. As an overall trend, the redness a* as well as yellowness b* value increased due to higher dye concentrations, indicating more intense color. Among the three extracts, Brazilwood had the best color purity. Its samples looked vivid and intense, while with the other dyes, the fabric samples appeared more muted and closer to grey. With regard to color uniformity, dyed fabrics without mordant had nearly a visually uniform color (compare

Figure 6).

For Logwood, the hue of the color appeared yellowish brown. There is a gradual decrease in hue angle, ranging from 71° to 54° (

Figure 8). This tendency meant that the higher the dye concentration, the redder (bluer) the sample became. It is obvious that higher dye concentrations also resulted in a higher level of chroma and lower level of lightness. Especially there was roughly a threefold increase in chroma between 2% at 20% concentration. In short, a redder, darker, and stronger color was achieved applying a higher concentration of dye.

From 5% to 10% concentration, there was a higher increase in C* value, so at this range the greyish brown should transform to a much purer brown. As seen in

Figure 8, greyish brown shades were achieved by 2% and 5%, while a moderate or strong brown was available with higher dye concentrations. With higher dye concentrations, the L* value continued decreasing, but with a lower gradient. The data between 15% and 20% concentration illustrated that three chromatic attributes (L*, h, C*) did not change much.

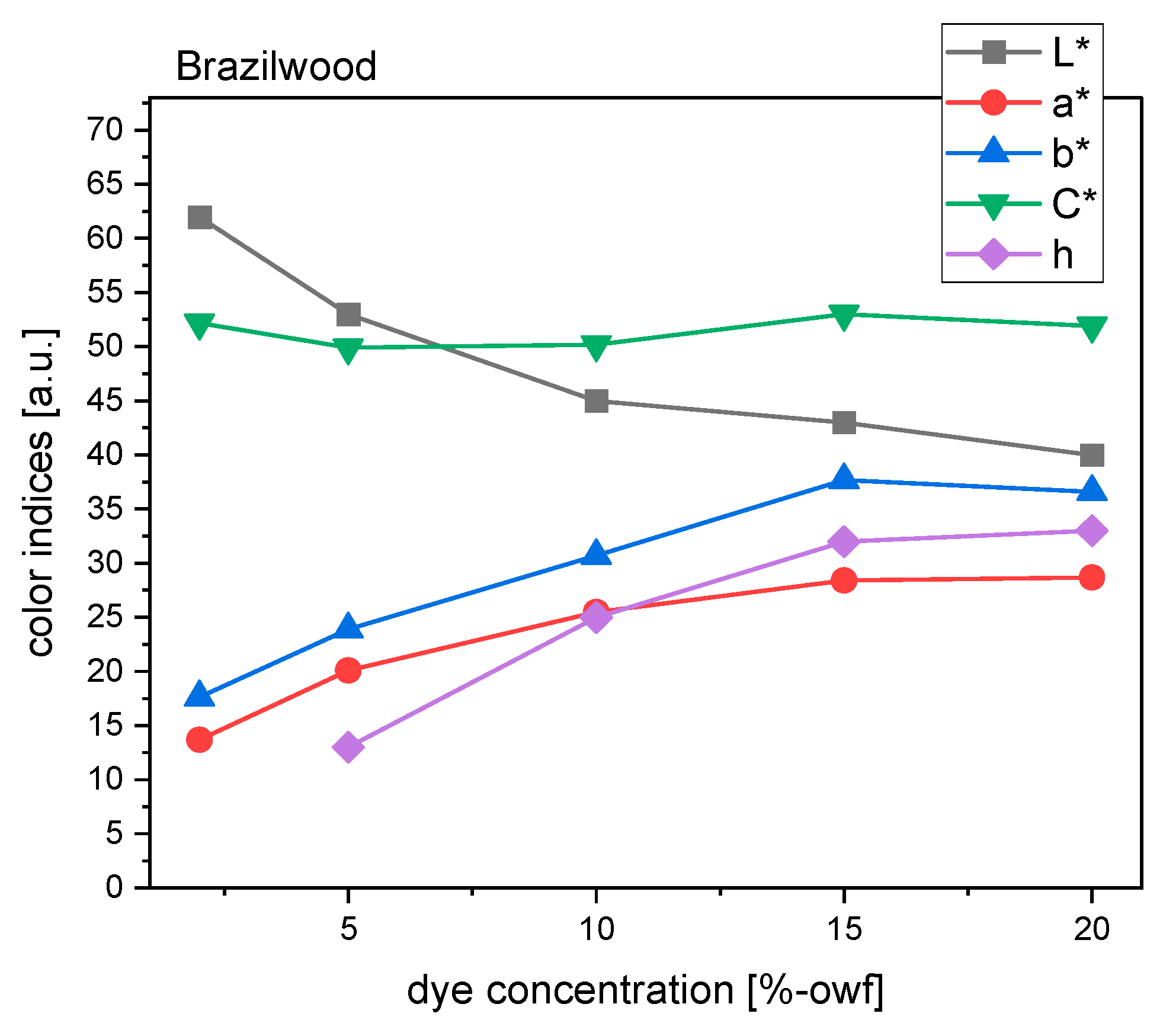

For samples dyed with Brazilwood, an upward tendency of C* value between 2% and 15% dye concentration indicated that the samples became more chromatic or saturated (

Figure 9). At 15% concentration, chroma reached a peak of 47, but afterwards it started to reduce gently. Therefore, a more vivid color was still produced with higher dye concentrations, but not more than 15%. From 2% to 10% concentrations, the L* value went down significantly by nearly one-third. After that, luminous intensity continued to decline but at a slower rate. Similarly, the color difference ΔE did not increase considerably anymore when the dye concentration was more than 15%.

Figure 9.

Color indices determined for cotton fabrics after dyeing with Brazilwood extract using increasing dye concentration without mordanting.

Figure 9.

Color indices determined for cotton fabrics after dyeing with Brazilwood extract using increasing dye concentration without mordanting.

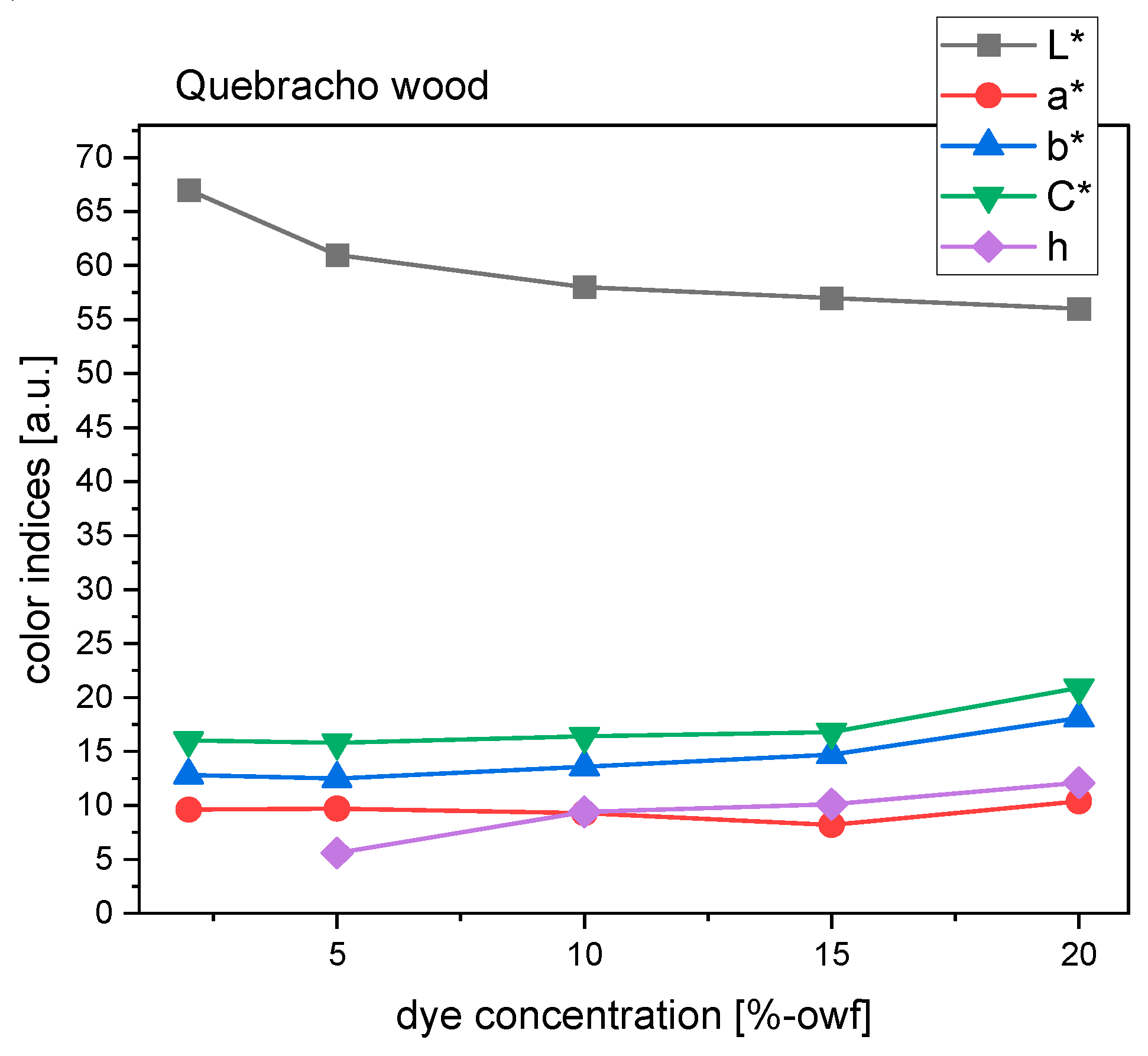

Turning to Quebracho wood, the hues were described as pale orange-yellow and yellowish brown (

Figure 6). The attribute of hue went up and down, but the change is towards the yellow direction. Therefore, from 10% to 20% dye concentration, the hue is perceived as more yellow than that of the control sample (

Figure 10). The hue angle of 5% concentration is a tiny bit smaller than at 2%, so the fabric looked a little redder. As for saturation, C* remained fairly unchanged when concentrations were below 15%, and it saw a moderate growth when the concentration reached 20%. This explains why its visual color in practice looked much more brilliant than the rest of the samples. Regardless, samples dyed with Quebracho wood were generally duller or less chromatic than with the other woods due to lower C*. Higher concentrations witnessed a reduction of lightness, which was indicative of the color being darker. However, the L* value was relatively stable from 10% to 20% dye concentrations (

Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Color indices determined for cotton fabrics after dyeing with Quebracho wood extract using increasing dye concentration without mordanting.

Figure 10.

Color indices determined for cotton fabrics after dyeing with Quebracho wood extract using increasing dye concentration without mordanting.

3.2. Dyeing with mordant

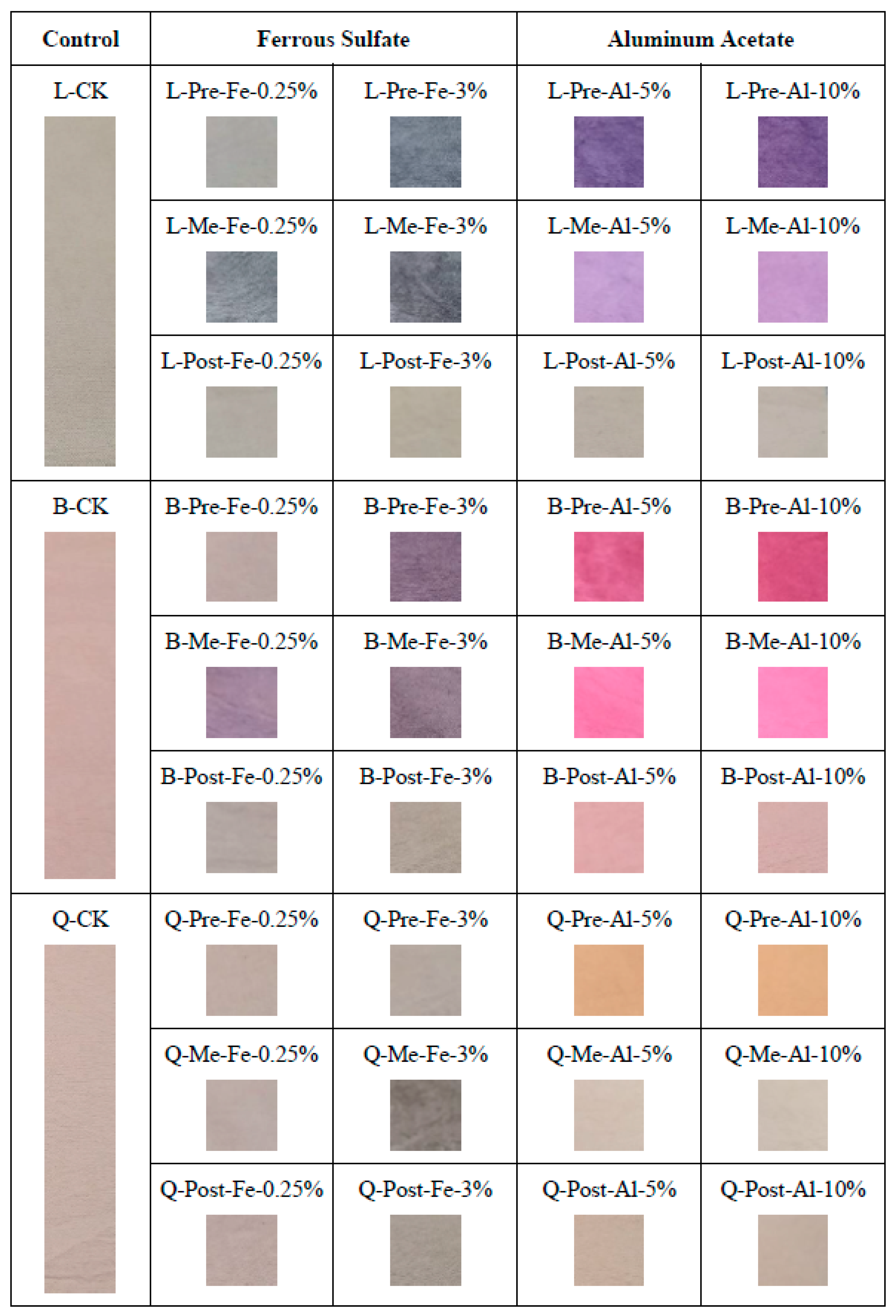

Cotton fabrics dyed with wood extracts and metallic mordants according to three mordanting methods were evaluated in terms of color strength, color coordinates (CIEL*a*b*) and visual appearance. The visual appearance is documented by photographic images of each prepared sample shown in

Figure 11. The control sample, which is dyed without a mordant, is used as a benchmark to assess how the mordants affect color and fastness attributes. The visual appearance of prepared cotton samples exhibits a broad range of different color shades appearing also in different intensity.

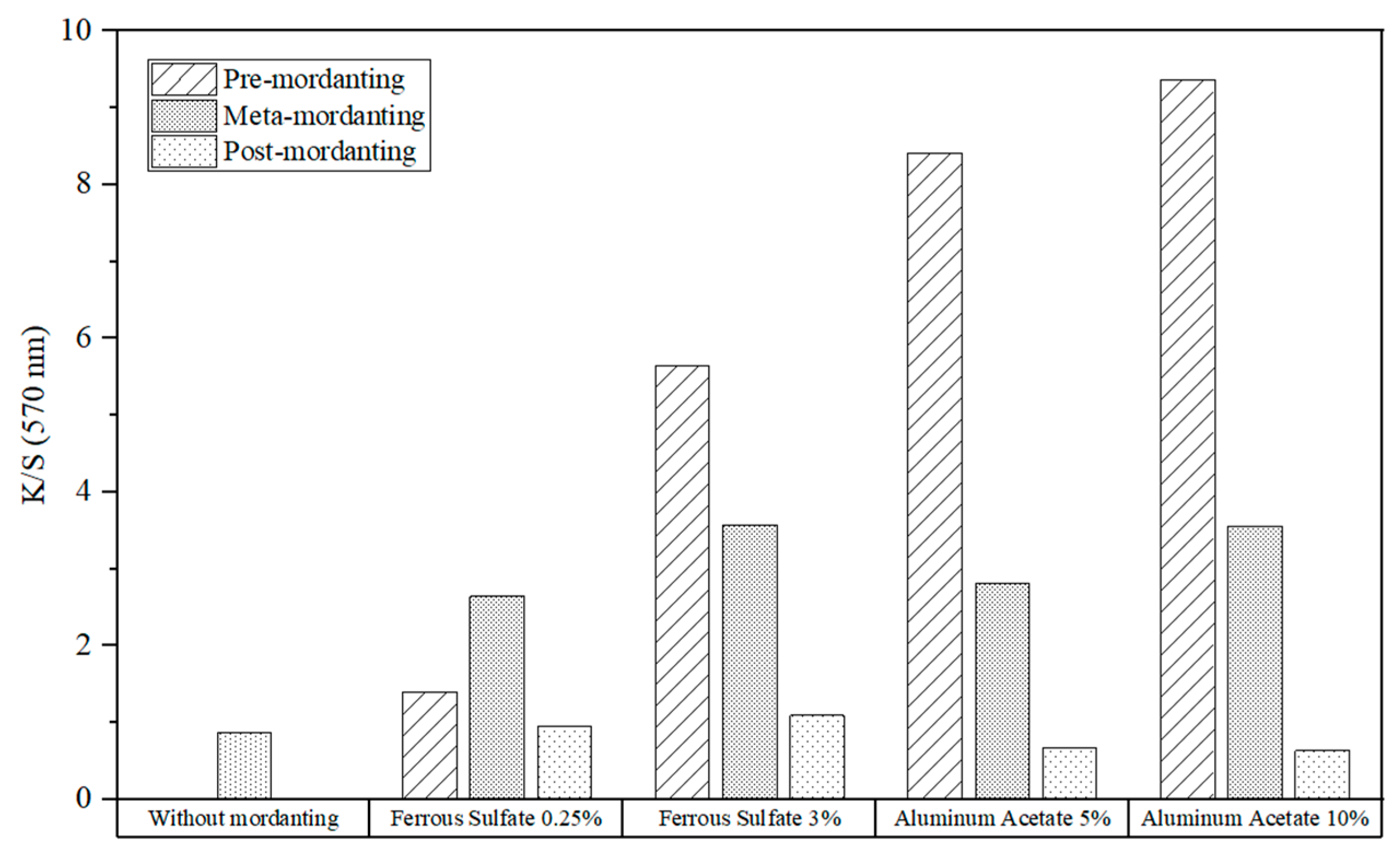

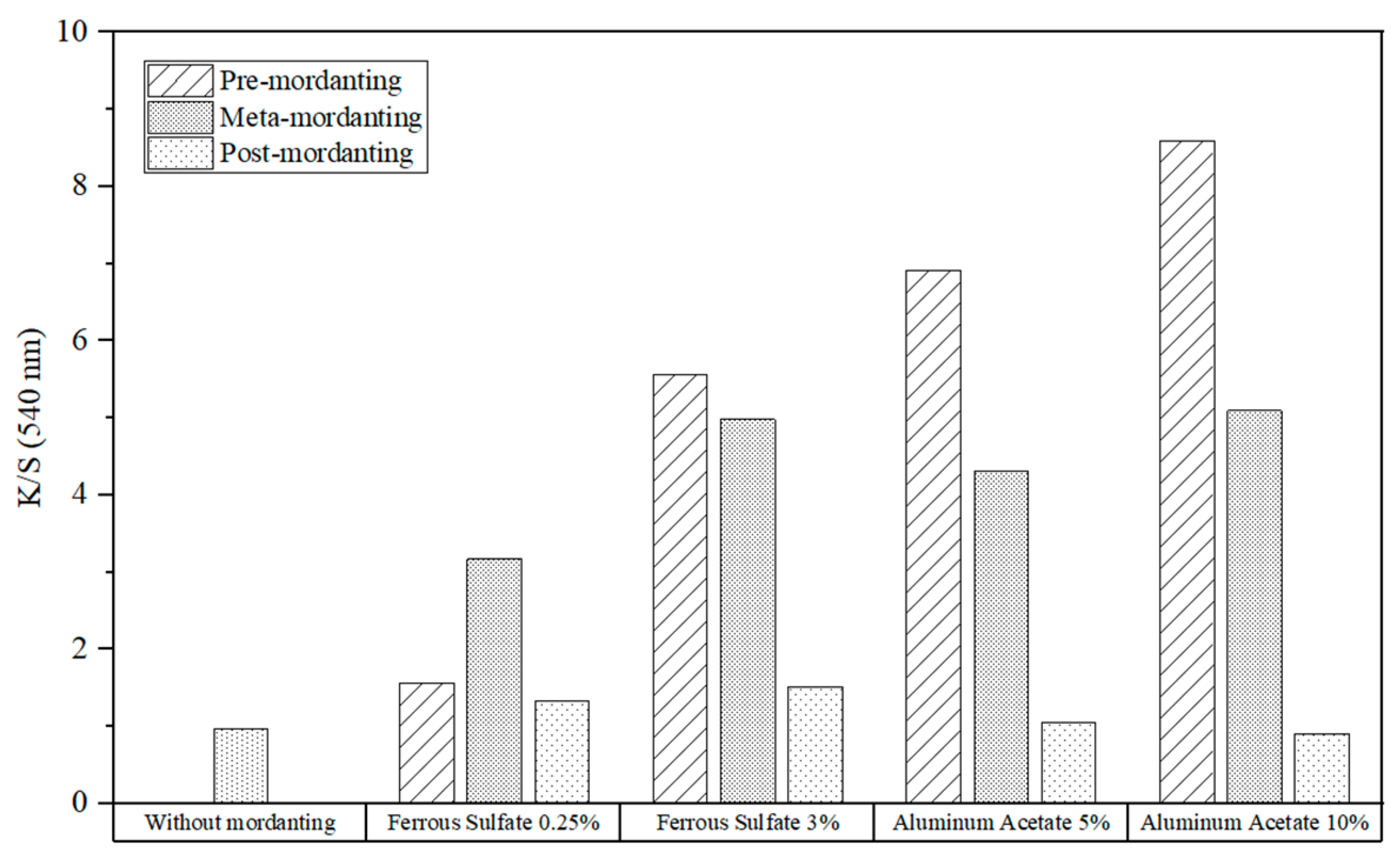

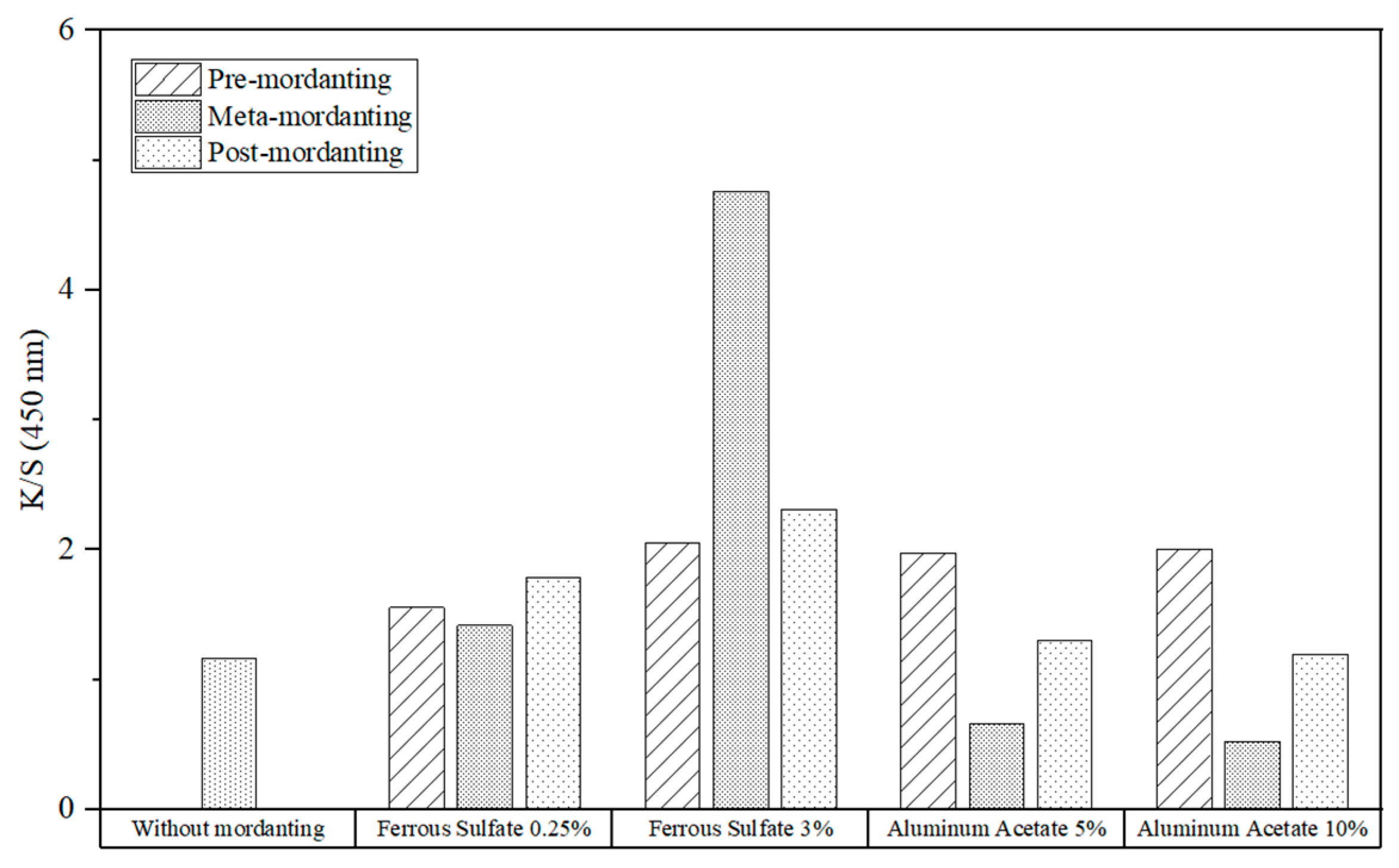

The color strength (K/S-values) of mordanted samples was calculated at 570, 540 and 450 nm for Logwood, Brazilwood and Quebracho wood, respectively (

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). Mordanting had a positive impact on the dye adsorption of cotton in most cases, as indicated by increased K/S values. For Logwood and Brazilwood, pre- and meta- mordant with both metallic salts proved to be more efficient in increasing K/S values than post-mordant. With regards to Quebracho, there is no single technique optimized for both iron and aluminum based mordant. It actually depends on the mordant concentration and the mordant itself.

Figure 12 depicts the impact of mordanting on the K/S values of the cotton fabrics dyed with Logwood extract. A remarkable improvement in color strength was observed in the pre- and meta-mordanting methods using 3% Iron Sulfate, 5% and 10% Aluminum Acetate.

The results confirmed that all samples had improved K/S values due to the used Iron Sulfate, and higher Iron concentrations were necessary to increase the color intensity. However, when it was utilized in the post-mordant procedure, a small loss in color strength was observed compared to the reference without mordant.

Similarly, higher Aluminum Acetate concentrations led to better K/S values except for the post-mordant process, in which its color strength even got lower with larger mordant concentrations.

When utilized in the pre-mordant procedure, Aluminum guaranteed better color yields than Iron sulfate. Overall, the pre- and meta-mordanting processes gave fabrics greater color strength than the post-mordanting technique. With only 0.25% of iron sulfate, one-bath mordant generated the best color strength. However, pre-mordanting is a far more effective way for 3% Iron concentration. In the case of Aluminum Acetate, pre-mordanting obtained the best results no matter in which of both concentrations the mordant is applied.

The K/S-values of the cotton fabrics dyed with Brazilwood extracts were compared in

Figure 13. As it is observed, the biggest enhancement in K/S-value was revealed at the pre- and simultaneous-mordanting processes with a 3% concentration of iron sulfate, and 5% and 10% concentrations of Aluminum Acetate. Similar to Logwood, this analysis demonstrated that mordanting with iron salt always enhanced K/S values, and a higher concentration of iron salt yielded a visible improvement in color strength.

Aluminum Acetate provided higher K/S values than the reference sample, except for the post-mordanting method with 10% Aluminum Acetate. For pre- and one-bath mordanting, but not for post-mordanting, using more Aluminum had a favorable impact on K/S values. When using the pre-mordanting method, mordanting with aluminum provided greater color strengths than using iron sulfate. However, less favorable results were observed by meta- and post-mordanting methods.

Among three mordanting methods at the same mordant concentration, pre- or meta-mordanting could produce the highest K/S value. With 0.25% iron sulfate, the K/S value of the dyed fabric was highest by one-step mordanting. Despite this, pre-mordanting will be the most effective method for 3% Iron sulfate concentration. As for Aluminum Acetate concentrations, pre-mordanting always leads to the best results regardless of the salt concentration.

The influence of mordanting on the K/S values of cotton fabrics dyed with Quebracho extracts is depicted in

Figure 14. The maximum color strength was obtained in one-bath mordanting with a 3% concentration of Iron salt.

For all three mordanting techniques, the K/S values of the Iron-mordanted fabrics exceeded that of the control sample at all concentrations. It also increased as the Iron Sulphate concentration rose from 0.25% to 3%. With a low concentration of Iron Sulphate, there was little change in the K/S values of the mordanted samples. For significantly greater color strength, a concentration of 3% is recommended.

Due to a moderate increase in K/S values, the pre-mordant procedure was best suited for Aluminum Acetate, whereas meta-mordanting resulted in unsatisfactory outcome. In Post-mordanting, the color strength was only slightly improved. It is not always beneficial to use more Aluminum Acetate because K/S values can decrease, as in meta- and post-mordanting methods. As for pre-mordanting, there is just a small jump between the K/S values of samples mordanted with 10% and 5% concentrations. Hence, it is generally not efficient to use more Aluminum Acetate.

Iron Sulphate and Aluminum Acetate are found to have similar color strengths in the pre-mordant method. However, in meta- and post- mordanting, Iron-treated fabrics had much higher K/S values than Aluminum-treated ones. Therefore, Iron Sulphate generally achieved better results. When comparing the three mordant processes, it is hard to identify a single method optimized for both Iron Sulphate and Aluminum Acetate. With just 0.25% Iron Sulfate, the post-mordant process was improved for dyeing. With 3% concentration, however, it is better to employ simultaneous-mordanting because the K/S value is more than doubled compared with other methods. For dyeing process using Aluminum Acetate, pre-mordanting was the best procedure. However, adding more Aluminum Acetate was not very effective because it only marginally increased color strength, as mentioned above.

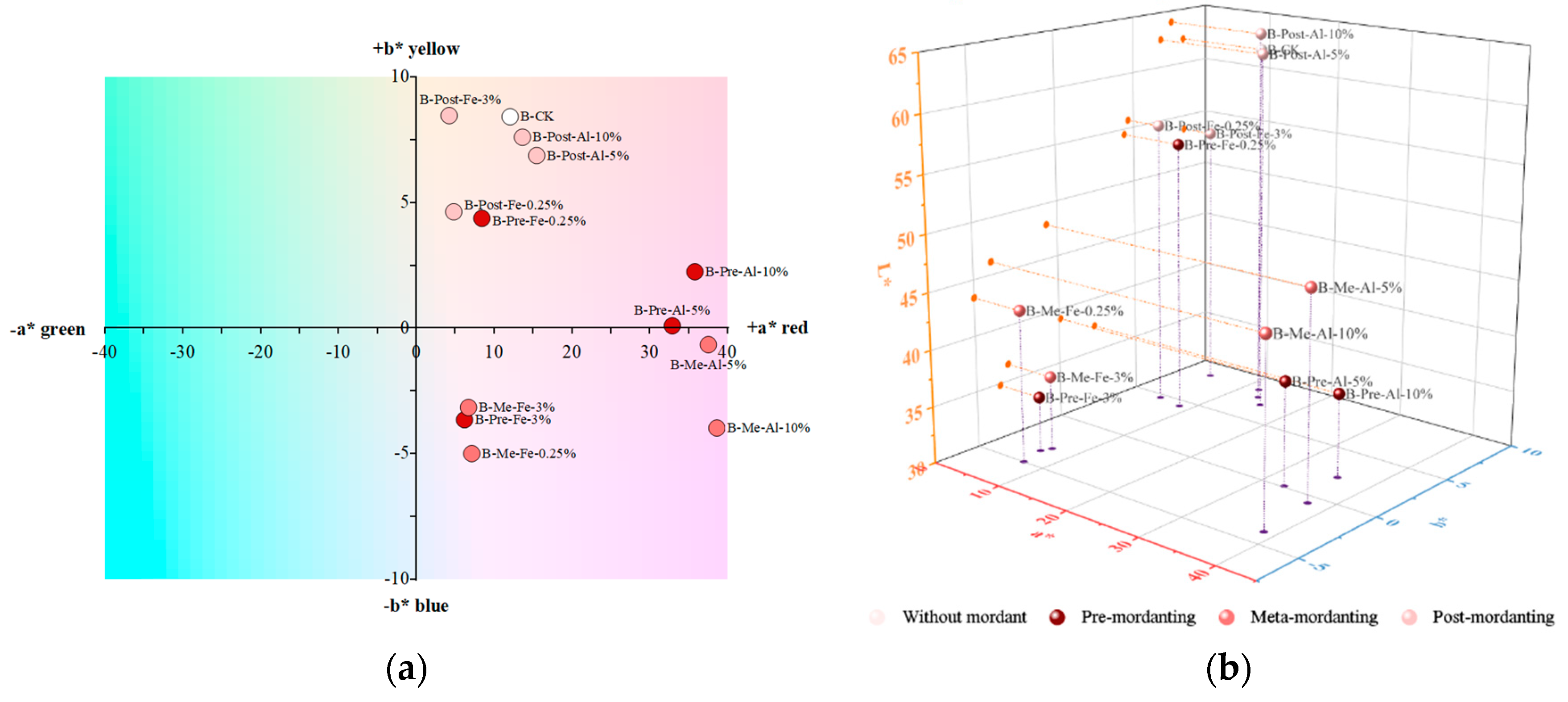

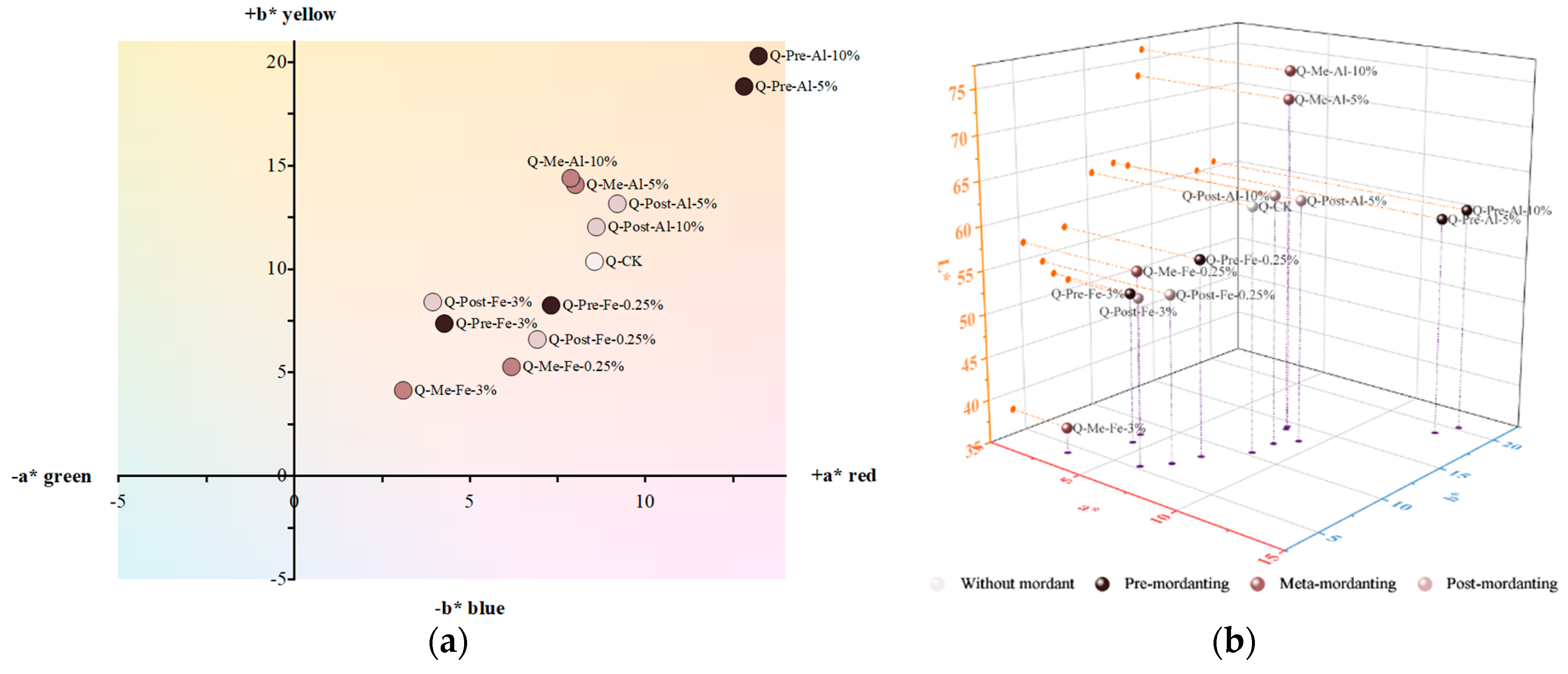

Additional to the discussion of visual appearance and K/S-values, the color indices are determined and presented in

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17.

With the addition of Iron Sulphate, lightness and chroma values of almost all samples in three dyes decreased, making them darker and more greyish (

Figure 15,

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). On the other hand, Aluminum Acetate always increases color saturation. In short, the L* data demonstrated that Iron Sulfate had a comparatively greater darkening effect than Aluminum Acetate, whereas the C* value indicated that Aluminum Acetate produced more saturated colors. Besides, most mordanted samples had high ΔE values (total color difference), particularly for pre- and meta-mordanted ones.

The same wood extract produced a variation of hues or even new color by applying two mordants. There was a remarkable change of the color gamuts when Logwood and Brazilwood extracts interacted with metallic mordants according to pre- and simultaneous-mordanting techniques. This is in contrast to the post-mordanting procedure either by Iron or Aluminum salt, because the colors obtained were relatively similar to those of control samples. Turning to Quebracho, metallic salts did not change its original color completely.

The colorimetric data of samples dyed with Logwood. L*, a* and b* values are plotted in two- and three-dimensional space and presented in

Figure 15.

The hue of not mordanted fabric was specified by a very light yellowish-brown color. Generally, the color shade was darker and duller with iron sulfate, but lighter and stronger with Aluminum Acetate. This is consistent with findings from previous research. As it is presented in

Figure 11, the use of metallic mordants produced new colors. Although few mordanted samples still stayed in the orange range (35-70°) of hue circle like the non-mordanted one, all others shifted to 70-105° yellow, 195-285° blue, and 285-350° violet (

Figure 15).

When Iron Sulfate was combined with Logwood in the pre-mordant process, there were two different colors depending on the concentration of Iron Sulfate as well as the mordant method.

The obtained data show that cotton fabrics meta-mordanted with Iron Sulfate (0.25% and 3%) and pre-treated with Iron Sulfate (3%) produced a bluish grey, because hue angles were inclined towards the blue coordinate of the blue-red zone. Meanwhile, the other Iron-mordanted samples had similar brown color like the not mordanted one since their hue angles moved fractionally from the standard of 67.11°. In general, Iron mordant had a darkening effect (lower L*, C* values) by generating black precipitates when it reacts with the logwood extract. Only in the case of post-mordanting with Iron Sulfate 3% (owf), the sample became slightly saturated, but the darkening effect persisted. The darkest shade was obtained from pre-mordanting with 3% of Iron Sulfate and followed by simultaneous-mordanting.

Aluminum Acetate also generated two different hues. The pre- and meta-mordanted cotton fabrics were violet, as evidenced by hue angles of 304.77° to 310.27°. Meanwhile, post-mordanted samples were still located in the yellow-red zone, and very close to the control sample. Consequently, post-treatment with Aluminum Acetate created the closest hue to the not mordanted one. Likewise, a larger amount of Aluminum Acetate did not significantly modify the color, as demonstrated by minor differences in all L*, C*, h° values. The photographs shown in

Figure 11 visualizes how comparable their colors are.

As it is observed, the post-mordanting method did not bring such a substantial change in colorimetric data than pre- and simultaneous-methods. Compared to control sample, post-mordanted samples guaranteed the most equivalent outcomes of color measurement and visual assessment. Moreover, the L*a*b* values remained fairly static, and thus post-treated samples had the least color differences (ΔE).

When the visual appearances of all samples were mutually compared, it is found that meta-mordanted fabrics suffered most from uneven colorization. The cotton samples treated in the pre-mordanting method showed a more uniform color distribution, but this still needs slight improvement. For these two methods, a smaller amount of Iron Sulfate and a larger amount of Aluminum Acetate resulted in better color uniformity. The post-mordanting process achieved a high degree of uniformity regardless of types and concentrations of the used mordant. One-bath mordant is the most convenient preparation and should come to extensive use.

The colorimetric data of samples dyed with Brazilwood L*, a* and b* values are plotted in two- and three-dimensional space as presented in

Figure 16.

The apparent color of the control sample was greyish orange, while those treated with Iron Sulfate and Aluminum Acetate could have new color shades (

Figure 11). In general, both Iron Sulfate and Aluminum Acetate caused a less reduction in yellowness but an increase in bluish nuance compared to the control sample. Aluminum-treated fabrics have greater C* values and lower L* than the Iron-mordanted ones, and thus their samples are perceived as more vivid and lighter. The application of these two mordants created new colors (see

Figure 11).

For Logwood, Iron Sulfate was used to achieve two distinct hues. Similarly, Iron Sulfate had two distinct hues for Brazilwood dyed cotton. It was not only the Iron itself but also its concentration and the mordanting procedure that determined the hue. Pre-mordanting with Iron Sulfate (0.25%) and post-mordanting with Iron Sulfate (0.25% and 3%) gave a shade comparable to that of the control sample. Their hue angles varied from 27.52° to 63.62°, indicating a red-orange hue. The minor difference was that post-mordanted fabrics looked less red than the others. On the other hand, a violet color was obtained with Iron salt by pre-mordanting (3%) or meta-mordanting (0.25% and 3%). The hues stayed within a small range of 324.92° - 334.72°, specifying violet color. Violet fabrics that were pre-mordanted seemed slightly darker than the meta-mordanted ones.

Like Iron Sulfate, Aluminum Acetate could result in two different hues. In pre- and meta-mordanting, the hue angle shifted clockwise towards the red direction (+a* axis) in a range of 354.13° to 3.6°, indicating a pink color. L* of the samples that had been pre-treated with Aluminum Acetate decreased considerably, roughly about two-thirds of the control sample. However, in meta-mordanted samples, there is a lower loss in L*, accompanied by better C* and lower -b*. Given such that the former is dark pink, and the latter is light pink but stronger and bluer. In contrast to pre- and meta-mordanting methods, the post-mordanting method did not significantly alter the a*, b*, and L* values of samples treated with Aluminum Acetate. Their hue angles of 24.02 - 29.23° indicated a slightly redder hue compared with the not mordanted sample. Their samples were most similar to the control sample, due to minimal ΔE. As a result, Aluminum Acetate post-treatment produced the most comparable shade to the non-mordanted one.

Visual comparisons among all samples revealed that meta-mordanted fabrics are less evenly dyed than those using other techniques. Hence, dye evenness is not feasible with Brazilwood in one-bath mordanting, as with Logwood. The cotton after pre-mordant treatment displayed quite good degrees of uniformity. In order to get better color uniformity, it is recommended to use less Iron Sulfate and more Aluminum Acetate for these two procedures. No matter what kind or how much of a mordant was employed, the post-mordanting process produced highly uniform colors.

The colorimetric data of samples dyed with Quebracho wood extract are plotted in two- and three-dimensional space and presented in

Figure 17.

In the absence of a mordant, Quebracho dyeing resulted in yellowish brown shades on cotton (

Figure 11). The hue of cotton dyed without mordant was not entirely different from those treated with mordants, which was attributed to the positions of the datapoints only moving along the red (+a*) and yellow (+b*) axes. Their h° values are in the same range as the control sample, which is 35-70° (orange) in the color circle. The hue difference between a mordanted sample and the non-mordanted sample was not so large as in Logwood or Brazilwood dyed samples.

In comparison to Iron Sulfate mordanted fabrics, Aluminum Acetate treated fabrics have greater CIEL*a*b* values, reflecting stronger and lighter colors. Regardless of the mordanting method, dyeing with Iron Sulfate would produce darker and less saturated shades, reflected in lower L* and C* values. Results also revealed that fabrics got more red in hue at lower Iron concentrations (0.25%), and yellower at higher concentrations (3%). Higher Iron Sulfate concentrations did not exert a profound darkening effect, with an exception in meta-mordanting with 3% Iron Sulfate. In this case, the lightness value declined sharply from 63.02 to 37.92. This explains why its sample appeared much darker than all other samples, and its ΔE value of 26.43 exhibited a huge difference from the control sample. Undesirably, this sample suffered from a serious uneven dyeing defect, whereas the colors of all other samples looked completely or mostly uniform.

Compared to the control sample, dyeing with Aluminum Acetate mordant (pre-, meta-, and post-mordanting) gave a more yellow and brilliant shade, as evidenced by higher C* and hue difference. As can be seen from the above table, the hue of the standard sample was 50.51°, while the hue of samples treated with Aluminum Acetate ranged from 54.45° to 61.35°, adding a slight yellowish nuance to the brown color. The increase of the C* value indicated that the fabrics were not only more yellow but also stronger in coloration. The chroma levels were at their best in the pre-mordanting method, giving an earth-yellow color. Furthermore, a higher concentration of Aluminum Acetate did not alter the color drastically, as evidenced by small differences in all color attributes (L*, C*, h°). Samples that look nearly identical to the control sample are the post-mordanted ones with Aluminum Acetate because of a slight change in L*, C*, h° values and low color change (ΔE < 3). Meta-mordanted samples are pale orange-yellow due to the highest L* and hue angles closest to the yellow direction.

Except for one-bath dyeing at a 3% Iron Sulfate concentration, the outcome of color uniformity was excellent when utilizing Iron Sulfate as a mordant. Small unevenness appeared with Aluminum Acetate in both pre- and meta-mordant methods. The more Aluminum Acetate used in the pre-mordant process resulted in better evenness, but performed worse in the one-bath dyeing. Additionally, colors produced by the post-mordanting process were highly uniform no matter what type of mordant or how much was applied.

3.3. Effects of mordanting on colour fastness properties

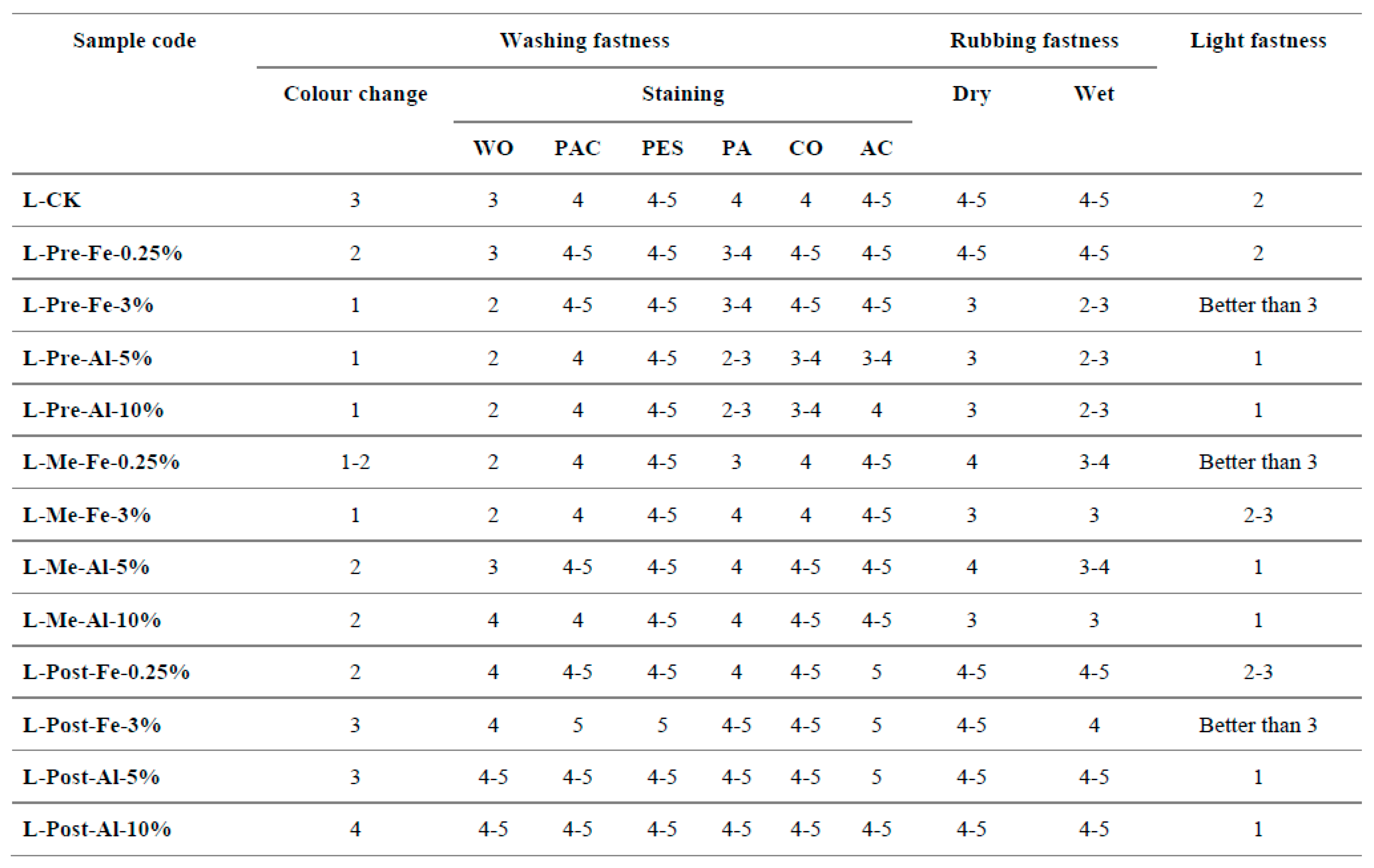

Mordanted fabrics were also tested for fastness to demonstrate their practicability. The

Table 1 to

Table 3 summarize the data about the evaluation of wash, rubbing and light fastness for Logwood, Brazilwood, and Quebracho wood applications, respectively. In general, the dyed fabrics without mordant displayed good color staining and rubbing fastness. However, Brazilwood and Quebracho wood showed fair to poor color change and light colorfastness, while Logwood had acceptable color change but only fair colorfastness to light.

The findings show that the addition of metal ions can enhance the color fastness of fabrics. However, the majority of mordanted and dyed samples did not show good performance in all three fastness tests simultaneously. For instance, Iron Sulfate often improved light fastness but not color change, while the opposite behavior was observed for mordanting with Aluminum salt. The mordant effect of iron sulfate on light fastness was better compared to applications with Aluminum salts.

The results obtained for Logwood dyed samples are displayed in

Table 1. The rubbing and washing fastness of the control sample were all above grade 3. However, the color faded quickly when exposed to light, indicated by a grade of 2 in light fastness.

Following is a sequence starting from the highest to the lowest ratings of staining and rubbing fastness with Iron and Aluminum: post-mordant > meta-mordant > pre-mordant. Regarding color change, post-mordanted samples also showed the highest grade for both metallic mordants. Therefore, post-mordanting is generally the most reliable method for Logwood in terms of fading properties. Despite giving deeper shades, pre- and meta-mordanting did not really improve fastness properties.

Iron-mordanted samples achieved the same or better lightfastness than the control sample, reaching a grade of 2 to better than 3. The staining might be worsened, but in many cases their gradings were still good enough. The main issue of Iron-treated fabrics was the poorer color change than the control sample. Only one sample (L-Post-Fe-3%) could be regarded as good because it showed a rating of 3 or above for all colorfastness to washing (color change and staining), wet and dry rubbing, and light.

Aluminum Acetate generated worse washing, rubbing, and light fastness than the control sample when used as a mordant in pre- and meta-mordanting methods. With the post-mordanting process, it achieved better washing fastness and retained good rubbing fastness, but the light fastness was still less than that of the control sample. As a result, it is not recommended to use Aluminum Acetate with Logwood extracts, if a certain light fastness is demanded.

The results for fastness tests obtained for Brazilwood dyed samples are displayed in

Table 2. For these samples without mordanting a color change of 2, staining of 3-4 to 4-5, rubbing fastness of 4-5 and light fastness of 2 are demonstrated. As shown in

Table 2, the results of color staining and rubbing fastness with Iron Sulfate followed a sequence in following order post-mordant > pre-mordant > meta-mordant. With Aluminum Acetate, they exhibited another order: post-mordant > meta-mordant > pre-mordant. The best light fastness for samples treated with Iron Sulfate was likewise achieved with post-mordant. Overall, when it comes to fading properties, post-mordanting is the best procedure for Brazilwood.

In many cases, Iron-mordanted samples outperformed control samples in terms of lightfastness, with grades exceeding 3. Even though the stains frequently got worse, the grades could be nonetheless acceptable. The main problem with Iron-treated fabrics was mostly no enhancement in color change. Only one sample (B-Post-Fe-3%), which was graded 3 for color change and better than 3 for all other tests, could be considered good.

Regardless of concentration or mordanting method, Aluminum Acetate resulted in a lower light fastness than the control sample, although it can improve other fading properties to some extent. The best washing and rubbing fastness were seen in the post-mordanted sample with 10% Aluminum Acetate; however, its light fastness was still 1. Consequently, the use of Aluminum Acetate for Brazilwood extract was disadvantageous.

Logwood and Brazilwood have several results in common. First, color change and lightfastness ratings of both non-mordanted and mordanted sampled were frequently poor to very poor (1-2). Second, a higher concentration of Aluminum Acetate could slightly improve washing and rubbing fastness in some cases, but under no circumstances it enhanced the light fastness. Another similarity is that the most appropriate process for both dyes is post-treatment with 3% concentration of Iron. Lastly, although pre- and meta-mordanted samples had much higher color strength, their washing and rubbing fastness were actually worse than post-mordanted ones. This is because the dye adsorption has vastly improved, but much of the dye was only superficially absorbed on the surface of the cotton material, making it easy to be removed during wash and crock fastness tests. Although having significantly faded from their original hues after wash, many of them still have much deeper color than post-mordanted ones.

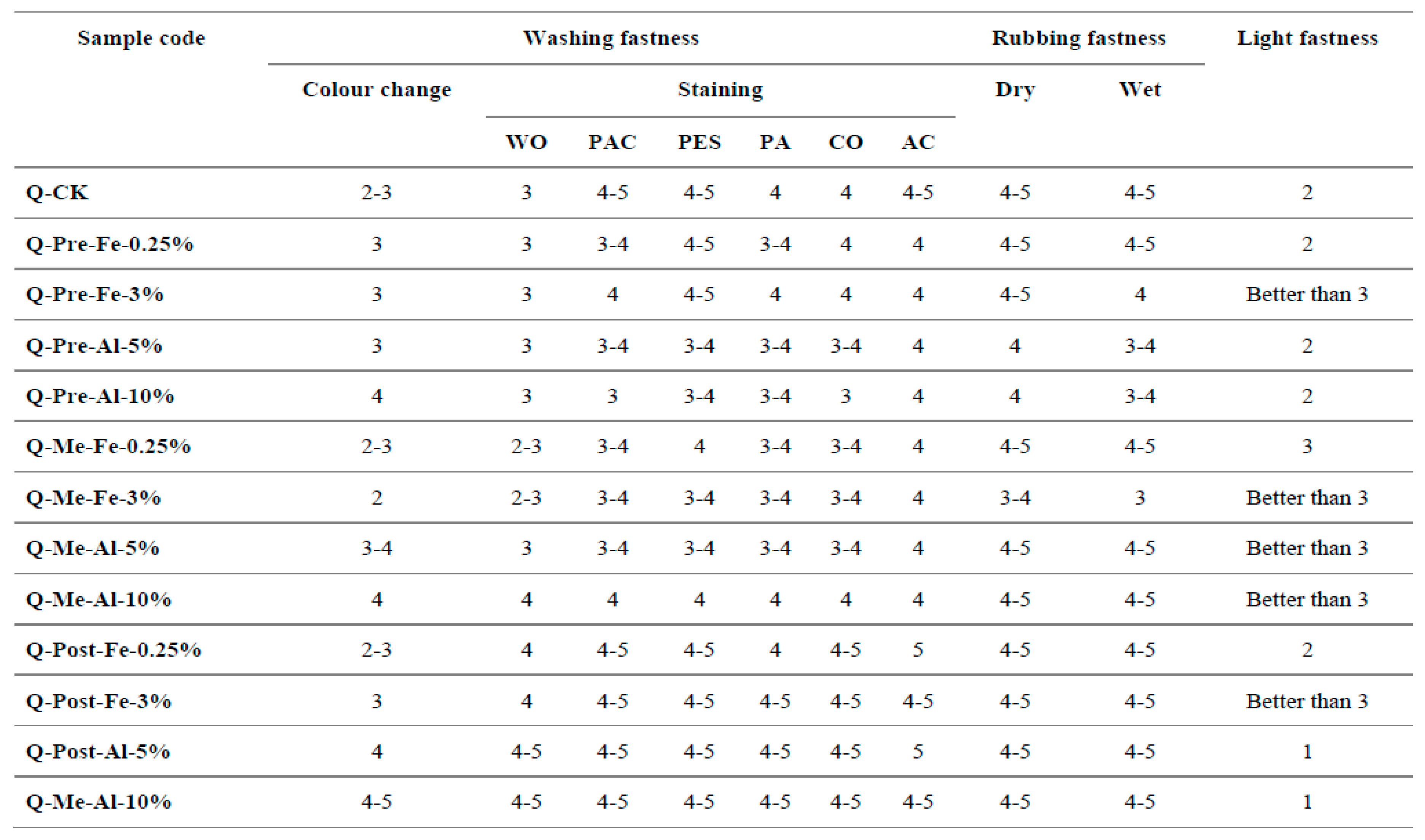

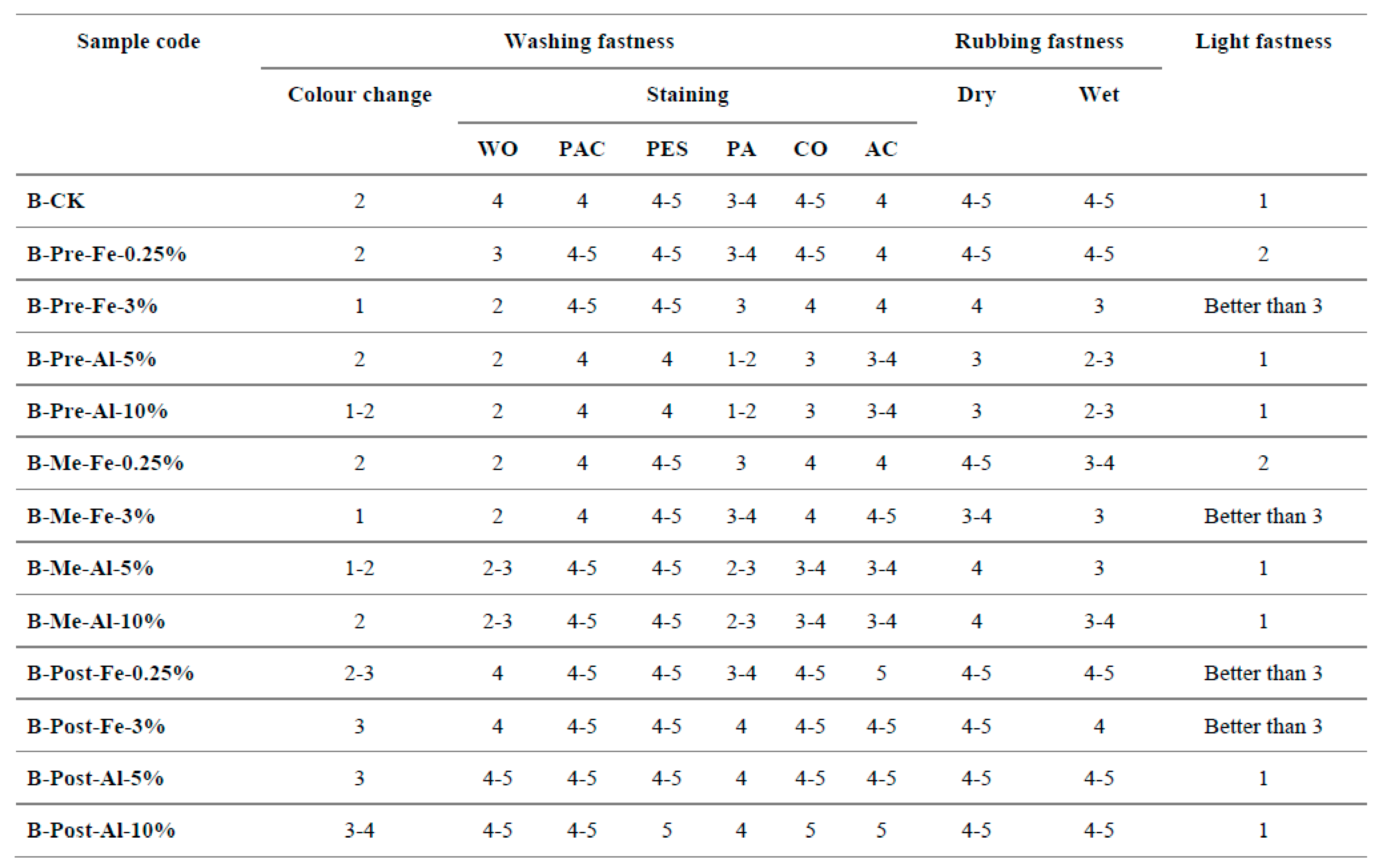

The results for fastness tests obtained for Quebracho dyed samples are displayed in

Table 3. Staining and color fastness to crocking of the control sample were found to be in the range of 3 to 4-5. However, ratings of color change and light fastness were 2 or 2-3 (poor) (

Table 3). The results demonstrated that color change in mordanted samples was better than in the control sample except for meta-mordanted ones with Iron Sulfate. More than half of the dyed samples had staining grades of good to very good (3 to 4-5). Additionally, half of them have shown improvement in light fastness. There would be three effective mordanting processes as described below.

Based on the control sample, Iron Sulfate was consistently effective in improving light fastness and, depending on the mordanting techniques, could also increase washing fastness. The best solution for Quebracho was found to be post-mordanting with 3% iron sulfate, which enhanced both wash and light fastness while maintaining good rubbing fastness. Pre-mordanting with 3% Iron Sulfate is also effective, but its staining is marginally worse than in the control sample.

With Aluminum Acetate, lightfastness values remained unchanged in pre-mordant, decreased in post-mordanting, and increased in meta-mordanting. Light fastness was subjected more to the mordanting method rather than the Aluminum Acetate concentration. In the post-mordanting method, it was undesirable that both washing and rubbing fastness were outstanding, but light fastness is only 1, making this method less efficient. The most effective way to treat cotton with Aluminum Acetate is one-bath mordanting since light fastness is considerably better than that of the control sample, although washing fastness is not that excellent but still acceptable. For an overall good fastness, a minimum concentration (5%) of Aluminum Acetate was sufficient. However, a 10% owf concentration would be recommended for marginally better color change and staining.

Table 3.

Color fastness properties of cotton fabrics after dyeing with Quebracho wood extract using different mordanting procedures.

Table 3.

Color fastness properties of cotton fabrics after dyeing with Quebracho wood extract using different mordanting procedures.

Overall, the fastness grades of Quebracho mordanted samples were higher than those of Logwood and Brazilwood. In terms of coloration durability for Logwood and Brazilwood, post-mordanting with Iron Sulfate 3% is the best option. Turning to Quebracho wood, besides pre- or post-mordanting with Iron Sulfate at 3%, cotton can be also treated well with Aluminum Acetate. One-bath dyeing is a definite advantage of dyeing with Quebracho wood extract because this method saves time and cuts down water and energy consumption. In summary, although Logwood and Brazilwood offer attractive hues like pink and violet, the color durability of these colors is lower and thus less attractive for commercial use. The color produced by all three extracts is greyish brown, and each of them had a different nuance. Wood extracts contain obviously less tannin than raw wood. For instance, tannin and cellulose fibers form strong connections, and Aluminum ions can effectively interact with the complex of tannins and fibers [

41].