Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

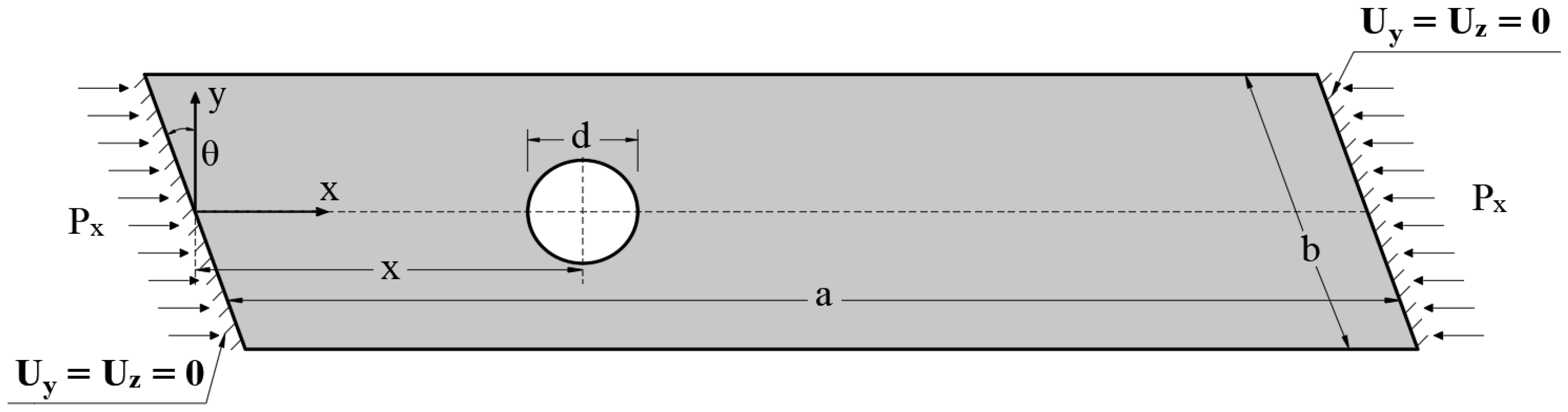

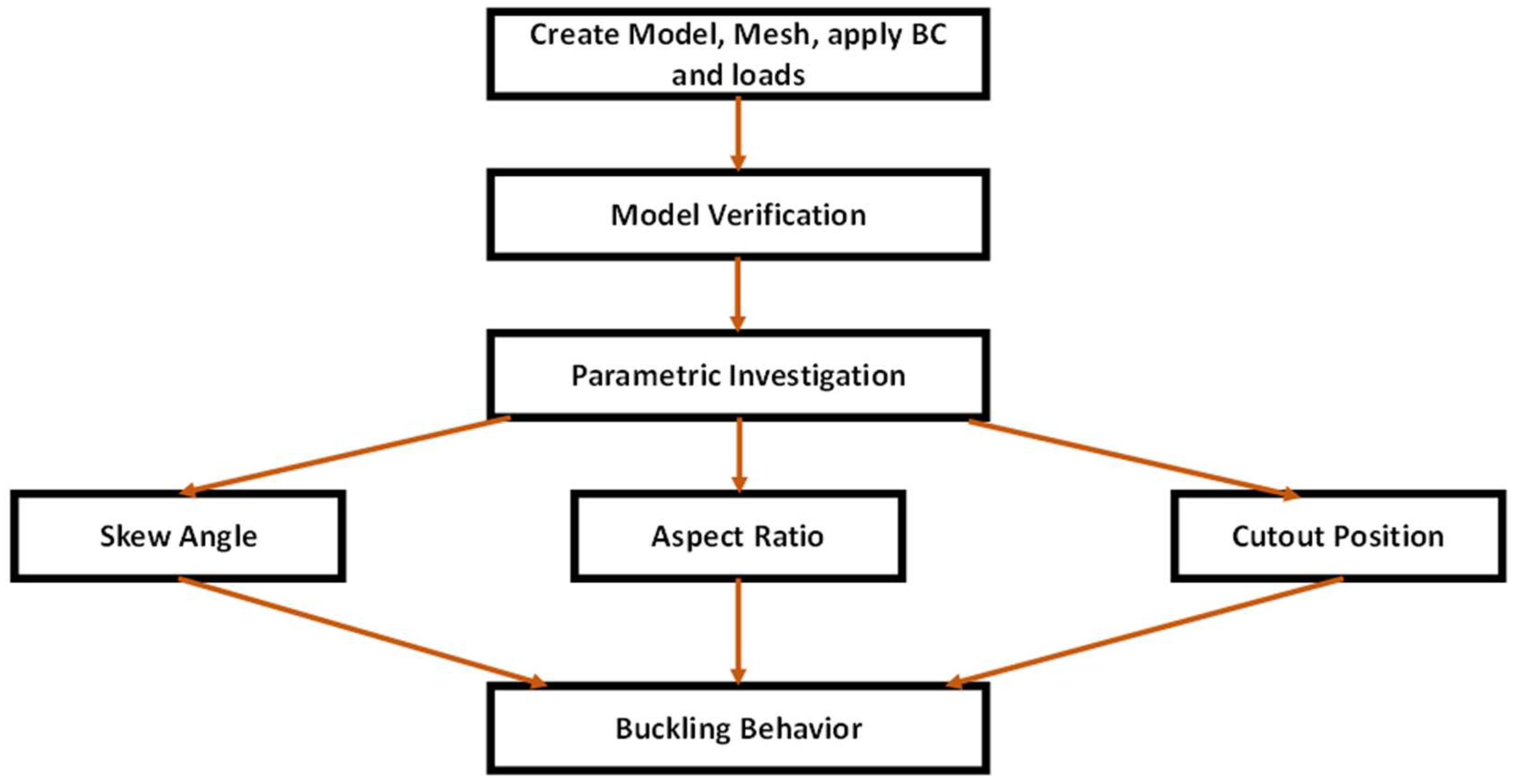

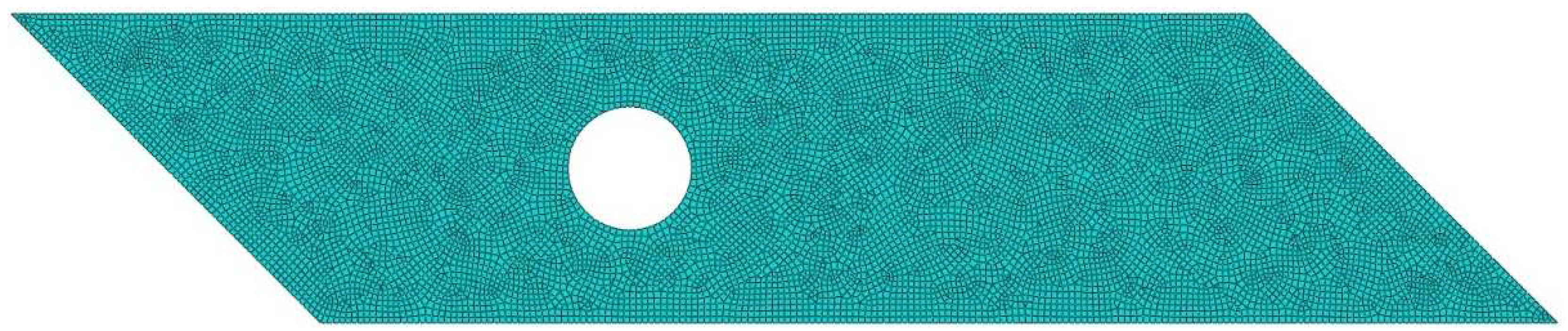

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

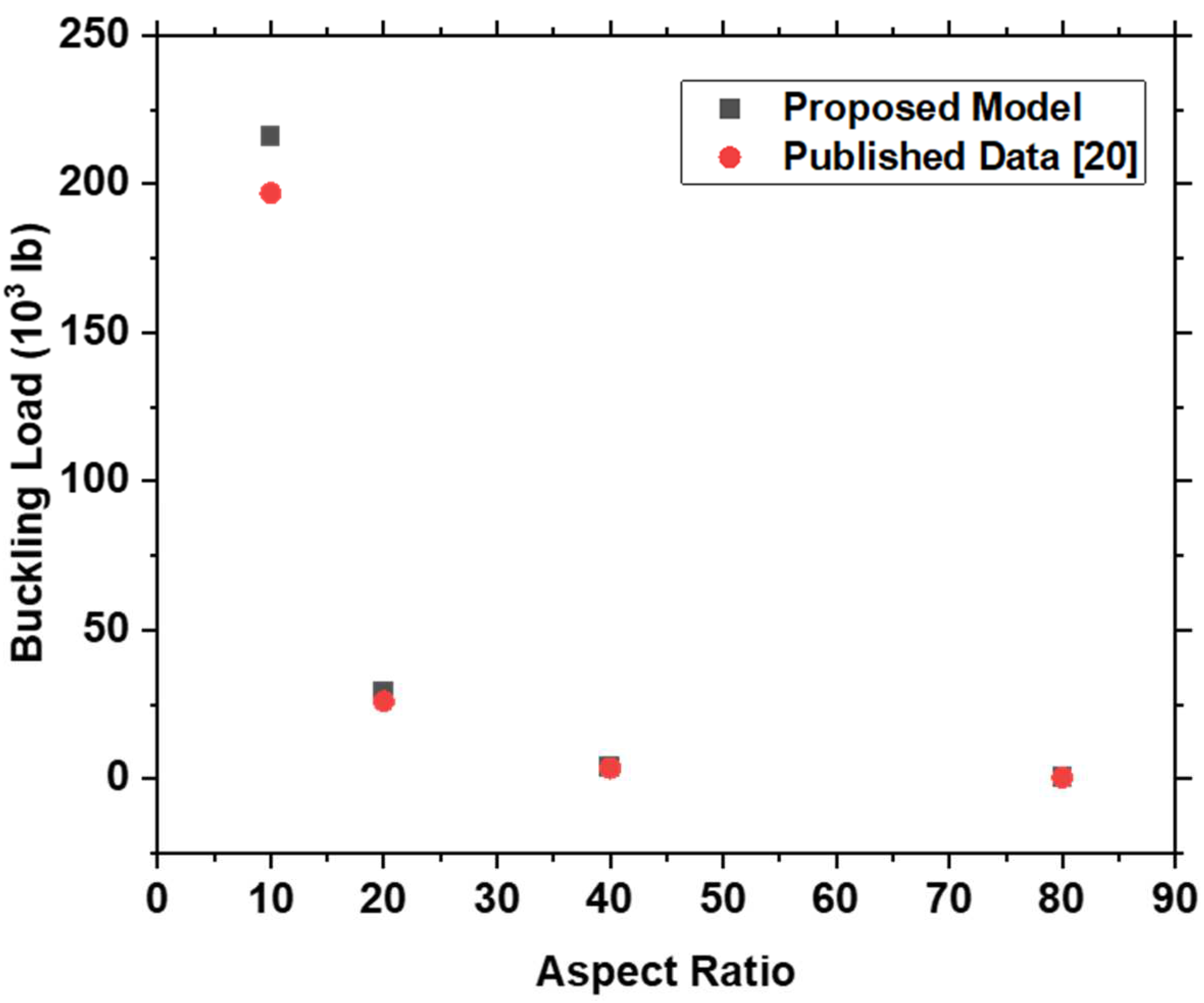

3.1. Model Verification

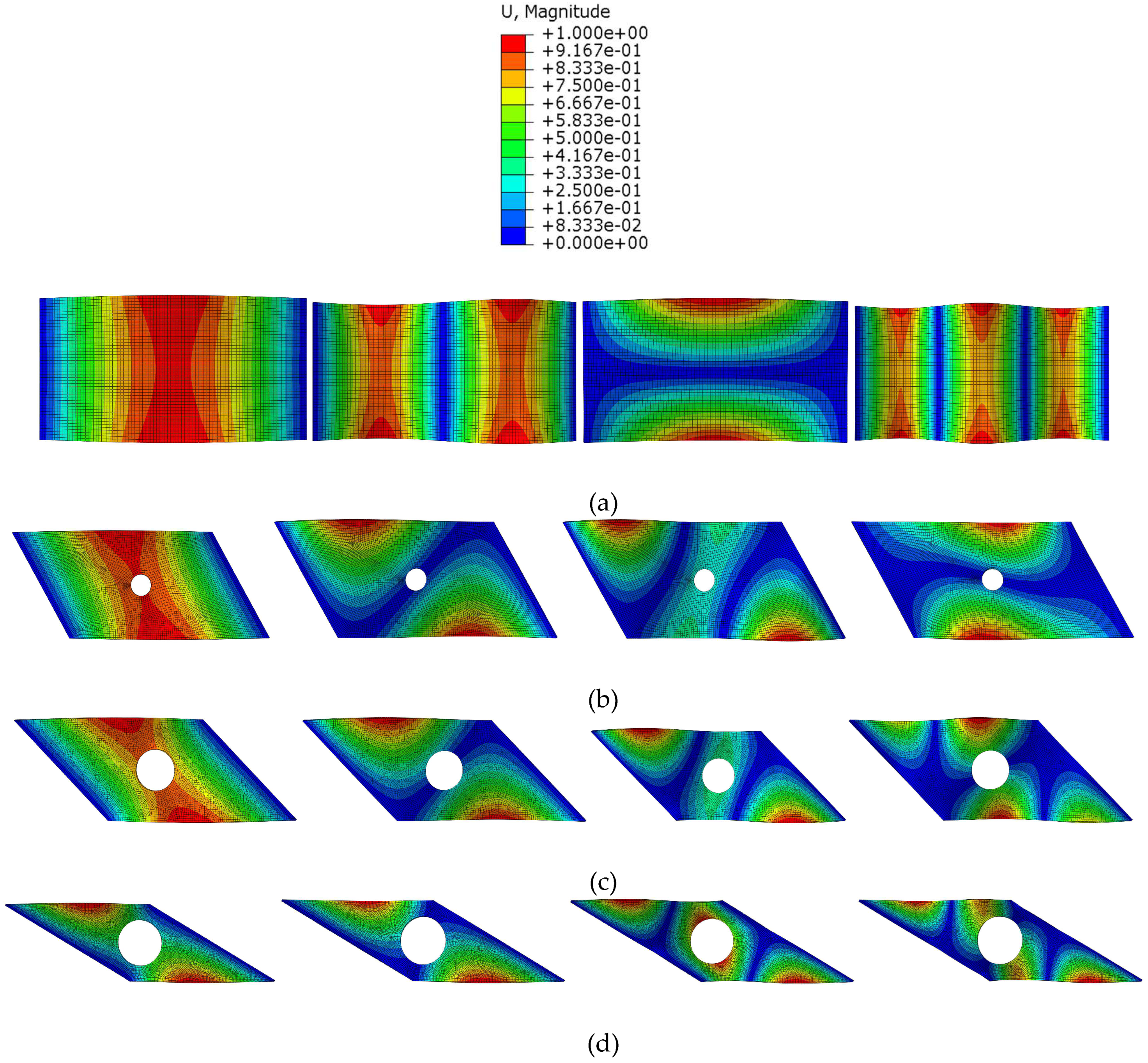

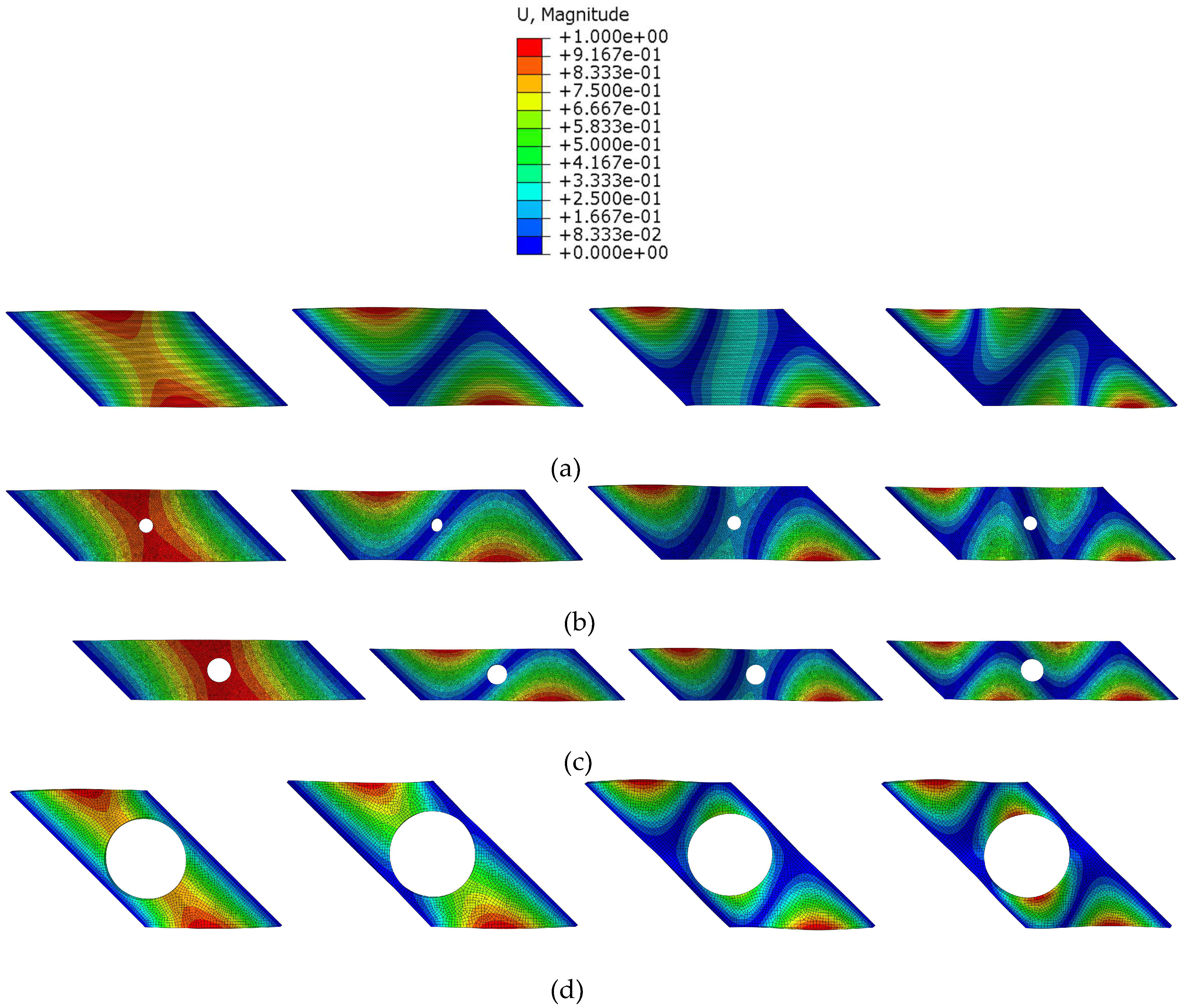

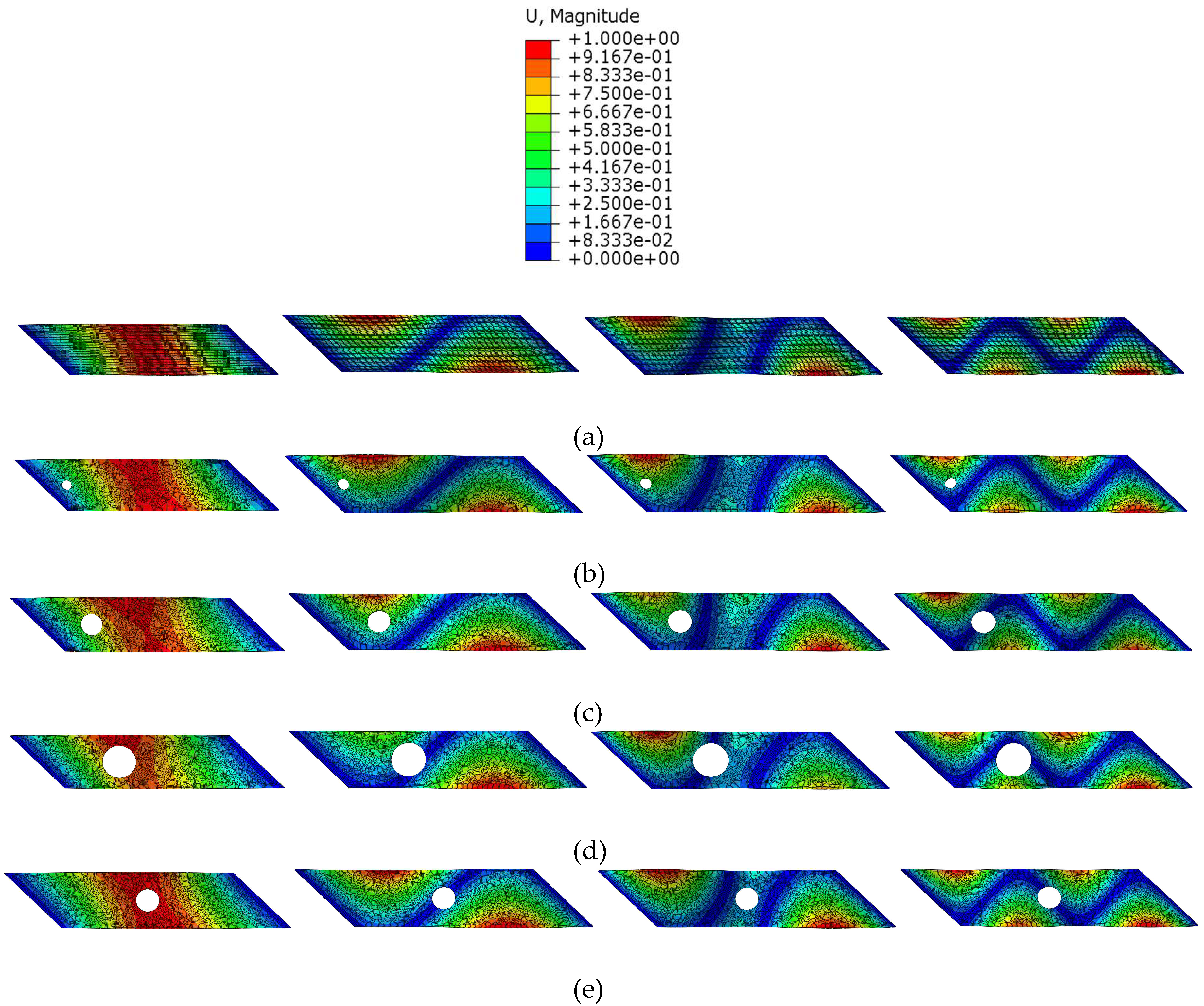

3.2. Parametric Investigation

4. Conclusions

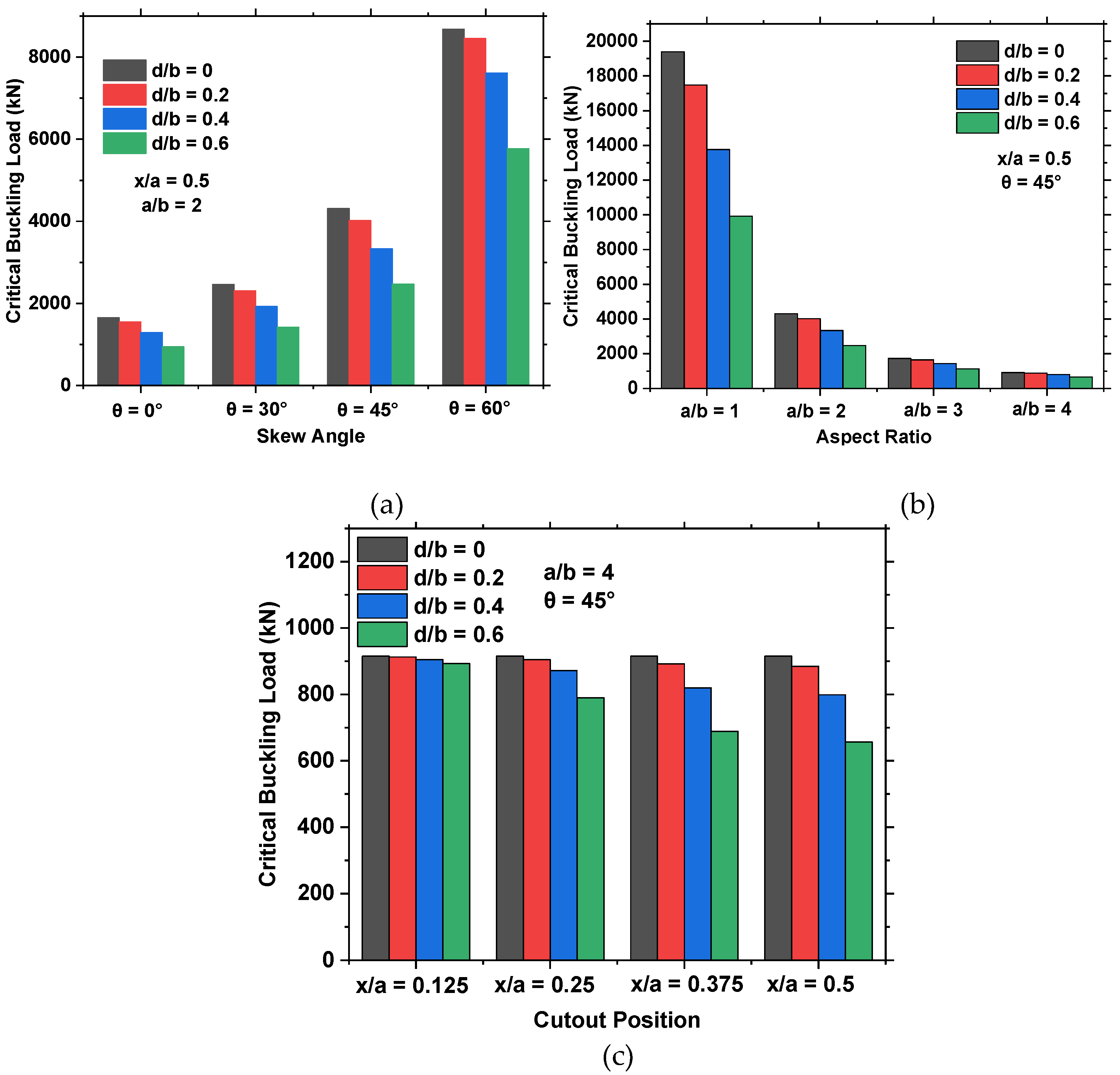

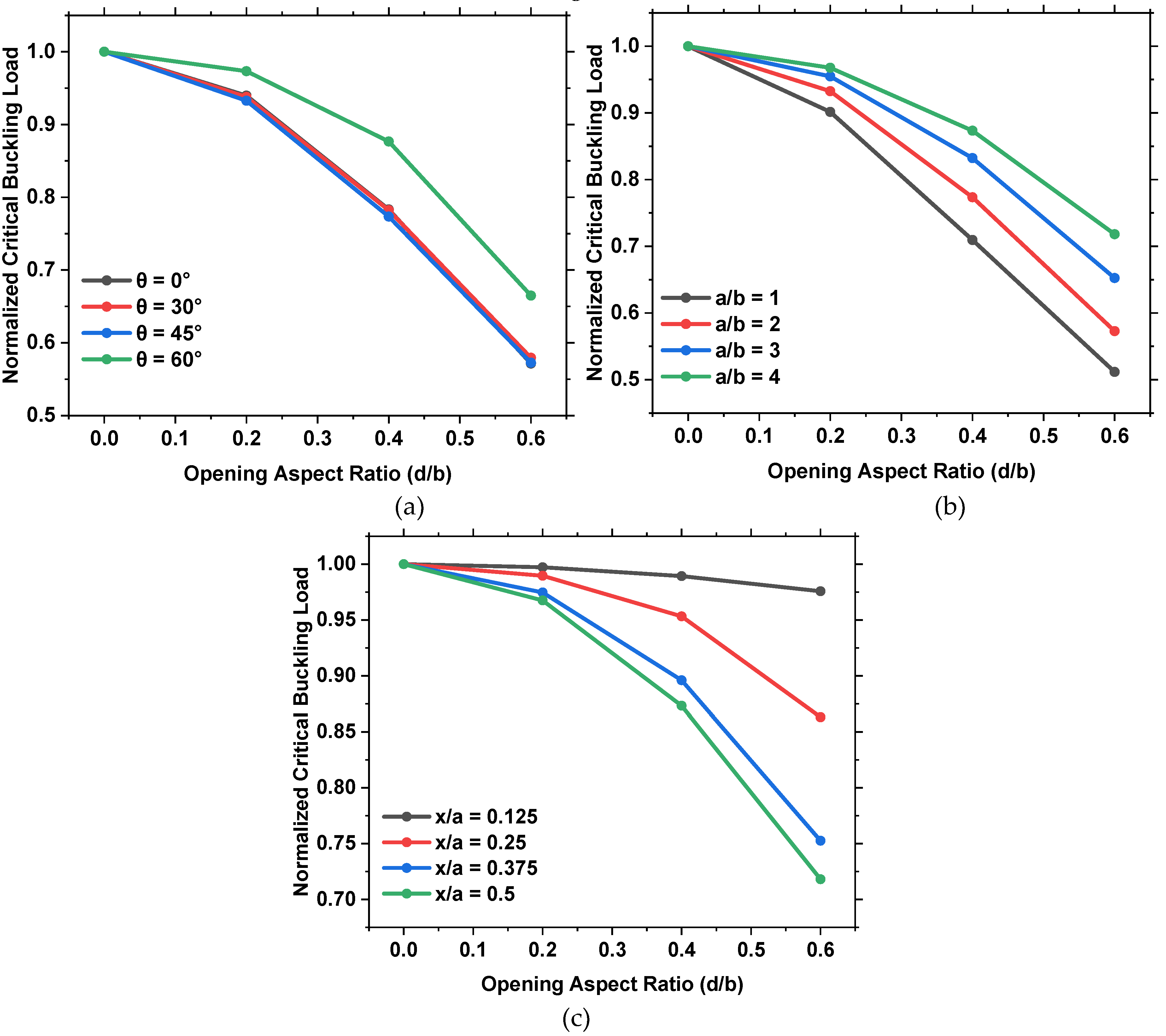

- The presence of a cutout and the increase in its size decreases the critical buckling load of the plate.

- Thin plates with skew angle of 60° obtained higher critical buckling loads by 206%, 134%, and 65%, compared to plates with skew angles of 0°, 30°, and 45°, respectively.

- An inversely proportional relationship between the critical buckling load and the aspect ratios of the plate is present.

- The position of the opening also affects the buckling load, as an opening closer to the plate’s edge showed a higher buckling load than that close to the center of the plate.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saleh, B.; Jiang, J.; Fathi, R.; Al-Hababi, T.; Xu, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, D.; Ma, A. 30 Years of functionally graded materials: An overview of manufacturing methods, Applications and Future Challenges. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 201, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elishakoff, I.; Eisenberger, M.; Delmas, A. Buckling and Vibration of Functionally Graded Material Columns Sharing Duncan's Mode Shape, and New Cases. Structures 2016, 5, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Foster, A.; Su, M. Elastic local buckling behaviour of beetle elytron plate. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 165, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieber, A.; Gardner, L.; Macorini, L. Formulae for determining elastic local buckling half-wavelengths of structural steel cross-sections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 159, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tran, P.; Mouritz, A.P. Compression and buckling analysis of 3D printed carbon fibre-reinforced polymer cellular composite structures. Compos. Struct. 2022, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoram-Nejad, E.S.; Moradi, S.; Shishehsaz, M. Effect of crack characteristics on the vibration behavior of post-buckled functionally graded plates. Structures 2023, 50, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moita, J.S.; Araújo, A.L.; Correia, V.F.; Soares, C.M.M. Mechanical and thermal buckling of functionally graded axisymmetric shells. Compos. Struct. 2020, 261, 113318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.H.; Arvin, H. Thermo-rotational buckling and post-buckling analyses of rotating functionally graded microbeams. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2021, 17, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenkour, A.M.; Aljadani, M.H. Buckling analysis of actuated functionally graded piezoelectric plates via a quasi-3D refined theory. Mech. Mater. 2020, 151, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Saran, V.; Harsha, S. Effect of elastic foundation and porosity on buckling response of linearly varying functionally graded material plate. Structures 2023, 55, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.E.-H.; Etman, E.; Atta, A.; Essam, M. Nonlinear behavior of RC beams strengthened with strain hardening cementitious composites subjected to monotonic and cyclic loads. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHamaydeh, M.; Elkafrawy, M.; Banu, S. Seismic Performance and Cost Analysis of UHPC Tall Buildings in UAE with Ductile Coupled Shear Walls. Materials 2022, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Elkafrawy, M.; Abuzaid, W.; Hawileh, R.; AlHamaydeh, M. Flexural Performance of RC Beams Strengthened with Pre-Stressed Iron-Based Shape Memory Alloy (Fe-SMA) Bars: Numerical Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitli, Y.; Mhada, K.; Bourihane, O.; Rhanim, H. Buckling and post-buckling analysis of a functionally graded material (FGM) plate by the Asymptotic Numerical Method. Structures 2021, 31, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuria, M.; Grover, N.; Goyal, K. Influence of porosity distribution on static and buckling responses of porous functionally graded plates. Structures 2021, 34, 1458–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vinh, P.; Van Chinh, N.; Tounsi, A. Static bending and buckling analysis of bi-directional functionally graded porous plates using an improved first-order shear deformation theory and FEM. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids 2022, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MJamali; Shojaee, T. ; Mohammadi, B.; Kolahchi, R. Cut out effect on nonlinear post-buckling behavior of FG-CNTRC micro plate subjected to magnetic field via FSDT. Adv. Nano Res. 2019, 7, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Thanh, C.C.; Nguyen, T.N.T.N.; Vu, T.H.T.H.; Khatir, S.; Wahab, M.A. A geometrically nonlinear size-dependent hypothesis for porous functionally graded micro-plate. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, A.R.; Ridwan, R.; Muttaqie, T. On the Resistance to Buckling Loads of Idealized Hull Structures: FE Analysis on Designed-Stiffened Plates. Designs 2022, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashkar, A.; Elkafrawy, M.; Hawileh, R.; AlHamaydeh, M. Buckling Analysis of Functionally Graded Materials (FGM) Thin Plates with Various Circular Cutout Arrangements. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkafrawy, M.; Alashkar, A.; Hawileh, R.; AlHamaydeh, M. FEA Investigation of Elastic Buckling for Functionally Graded Material (FGM) Thin Plates with Different Hole Shapes under Uniaxial Loading. Buildings 2022, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civalek, O.; Jalaei, M.H. Buckling of carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced composite skew plates by the discrete singular convolution method. Acta Mech. 2020, 231, 2565–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H. Accurate mechanical buckling analysis of couple stress-based skew thick microplates. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Prasad, R.B. Vibration and Buckling Analysis of Skew Sandwich Plate using Radial Basis Collocation Method. Mech. Adv. Compos. Struct. 2017, 10, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.T.; Shanmugam, N. Elastic buckling of uniaxially loaded skew plates containing openings. Thin-Walled Struct. 2011, 49, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Sahmani, S.; Safaei, B. Size-dependent shear buckling response of FGM skew nanoplates modeled via different homogenization schemes. Appl. Math. Mech. 2020, 41, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrestani, M.G.; Azhari, M.; Foroughi, H. Elastic and inelastic buckling of square and skew FGM plates with cutout resting on elastic foundation using isoparametric spline finite strip method. Acta Mech. 2018, 229, 2079–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems, D. Abaqus: Finite Element Analysis for Mechanical Engineering And Civil Engineering. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/ (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Ali, E.Y.; Bayleyegn, Y.S. Analytical and numerical buckling analysis of rectangular functionally-graded plates under uniaxial compression. Struct. Stab. Res. Counc. Annu. Stab. Conf. 2019, 2, 534–547. [Google Scholar]

- Shariat, B.S.; Javaheri, R.; Eslami, M. Buckling of imperfect functionally graded plates under in-plane compressive loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2005, 43, 1020–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.-H.; Chung, Y.-L. Mechanical behavior of functionally graded material plates under transverse load—Part I: Analysis. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 3657–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect Ratio (a/b) |

Opening Position (x/a) |

Opening Size (d/b) |

Skew Angle () |

Critical Buckling Load (kN) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1652 |

| 30 | 2461 | ||||

| 45 | 4311 | ||||

| 60 | 8683 | ||||

| Small Opening | 2 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 1552 |

| 30 | 2308 | ||||

| 45 | 4021 | ||||

| 60 | 8450 | ||||

| Medium Opening | 2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 1294 |

| 30 | 1926 | ||||

| 45 | 3335 | ||||

| 60 | 7613 | ||||

| Large Opening | 2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0 | 944 |

| 30 | 1426 | ||||

| 45 | 2469 | ||||

| 60 | 5772 |

| Skew Angle () |

Opening Position (x/a) |

Opening Size (d/b) |

Aspect Ratio (a/b) |

Critical Buckling Load (kN) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 45 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 19392 |

| 2 | 4311 | ||||

| 3 | 1728 | ||||

| 4 | 915 | ||||

| Small Opening | 45 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1 | 17482 |

| 2 | 4021 | ||||

| 3 | 1650 | ||||

| 4 | 885 | ||||

| Medium Opening | 45 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1 | 13758 |

| 2 | 3335 | ||||

| 3 | 1438 | ||||

| 4 | 799 | ||||

| Large Opening | 45 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1 | 9922 |

| 2 | 2469 | ||||

| 3 | 1128 | ||||

| 4 | 657 |

| Skew Angle () |

Aspect Ratio (a/b) |

Opening Size (d/b) |

Opening Position (x/a) |

Critical Buckling Load (kN) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 45 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 915 |

| Small Opening | 45 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.125 | 913 |

| 0.250 | 905 | ||||

| 0.375 | 892 | ||||

| 0.500 | 885 | ||||

| Medium Opening | 45 | 4 | 0.4 | 0.125 | 905 |

| 0.250 | 872 | ||||

| 0.375 | 820 | ||||

| 0.500 | 799 | ||||

| Large Opening | 45 | 4 | 0.6 | 0.125 | 893 |

| 0.250 | 790 | ||||

| 0.375 | 689 | ||||

| 0.500 | 657 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).