Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and discussion

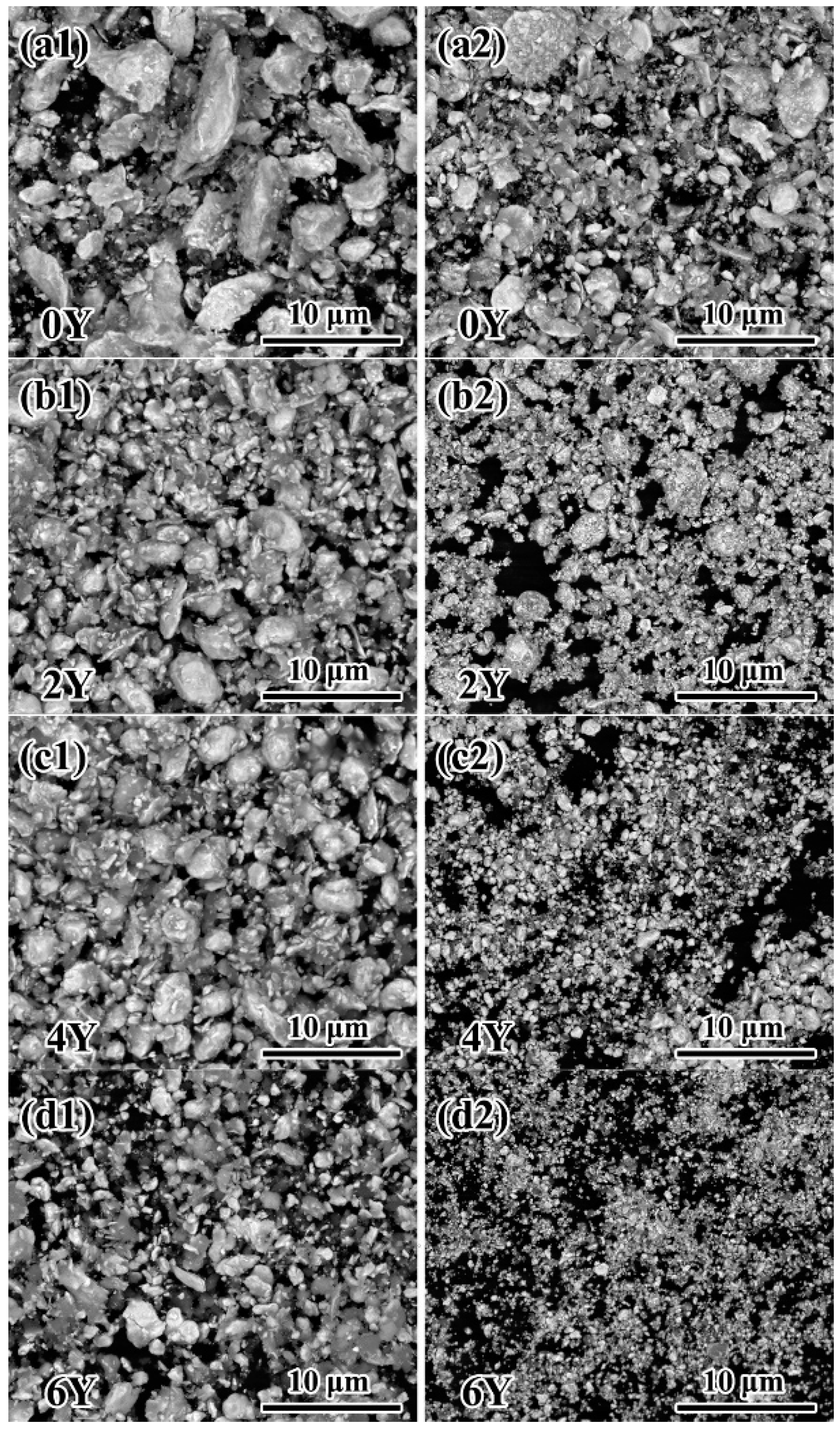

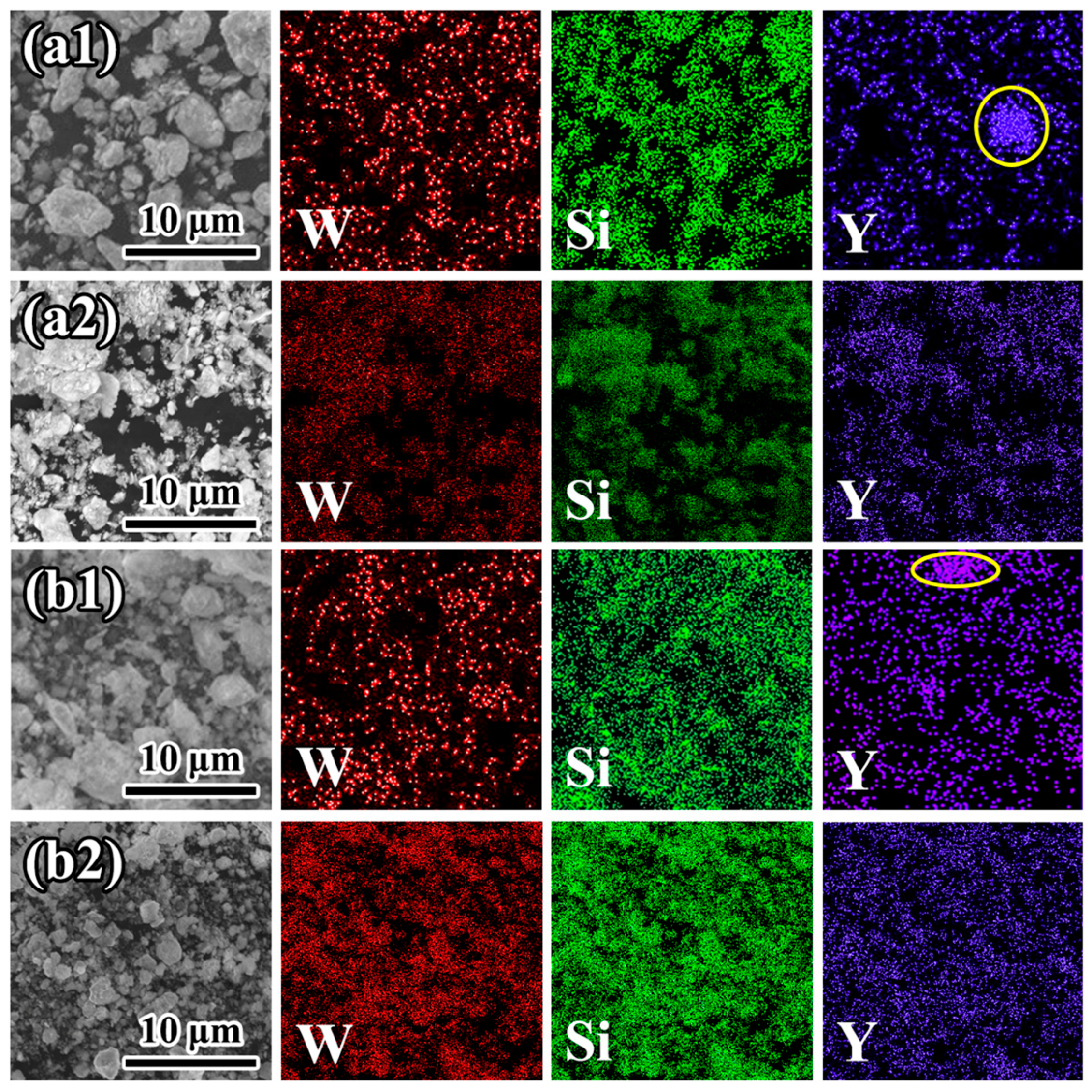

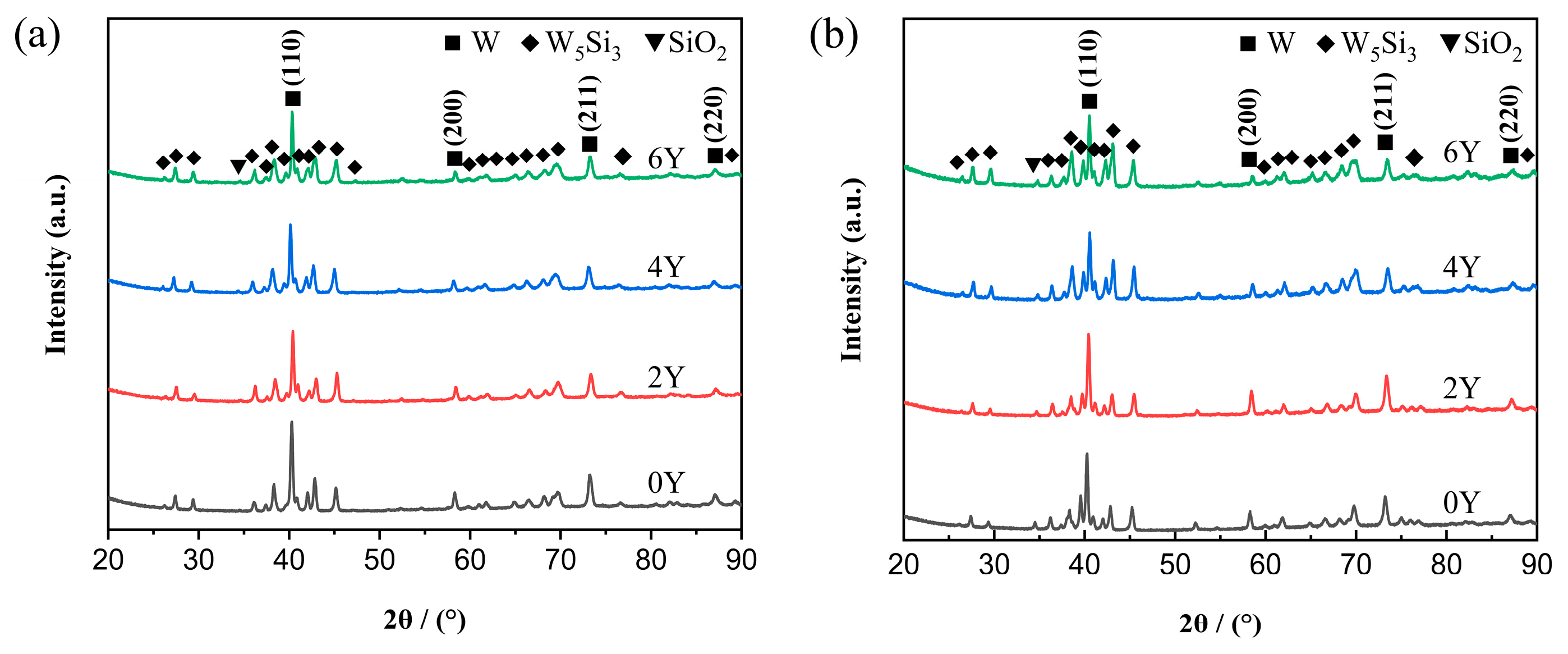

3.1. Microstructures of the as-prepared powders

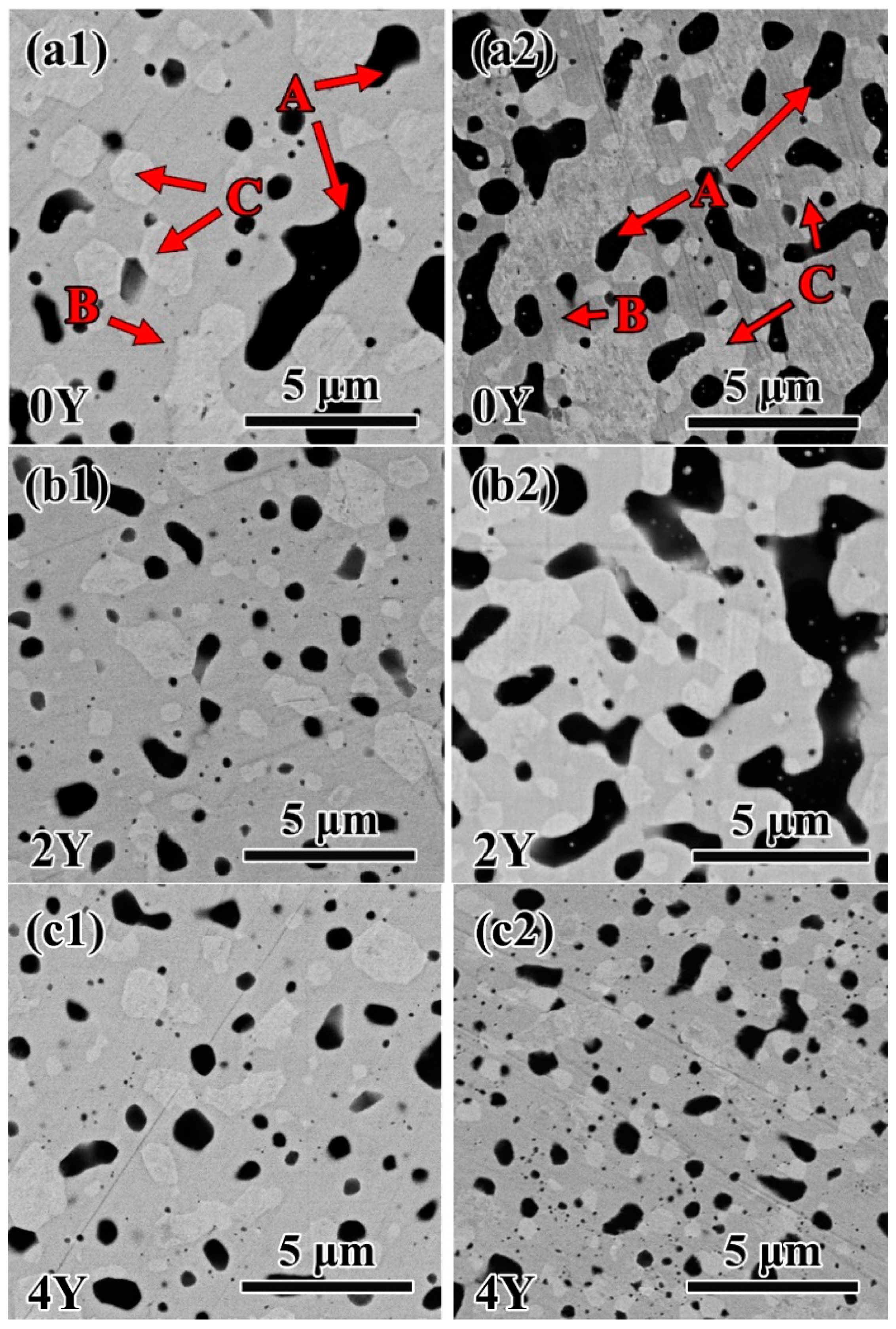

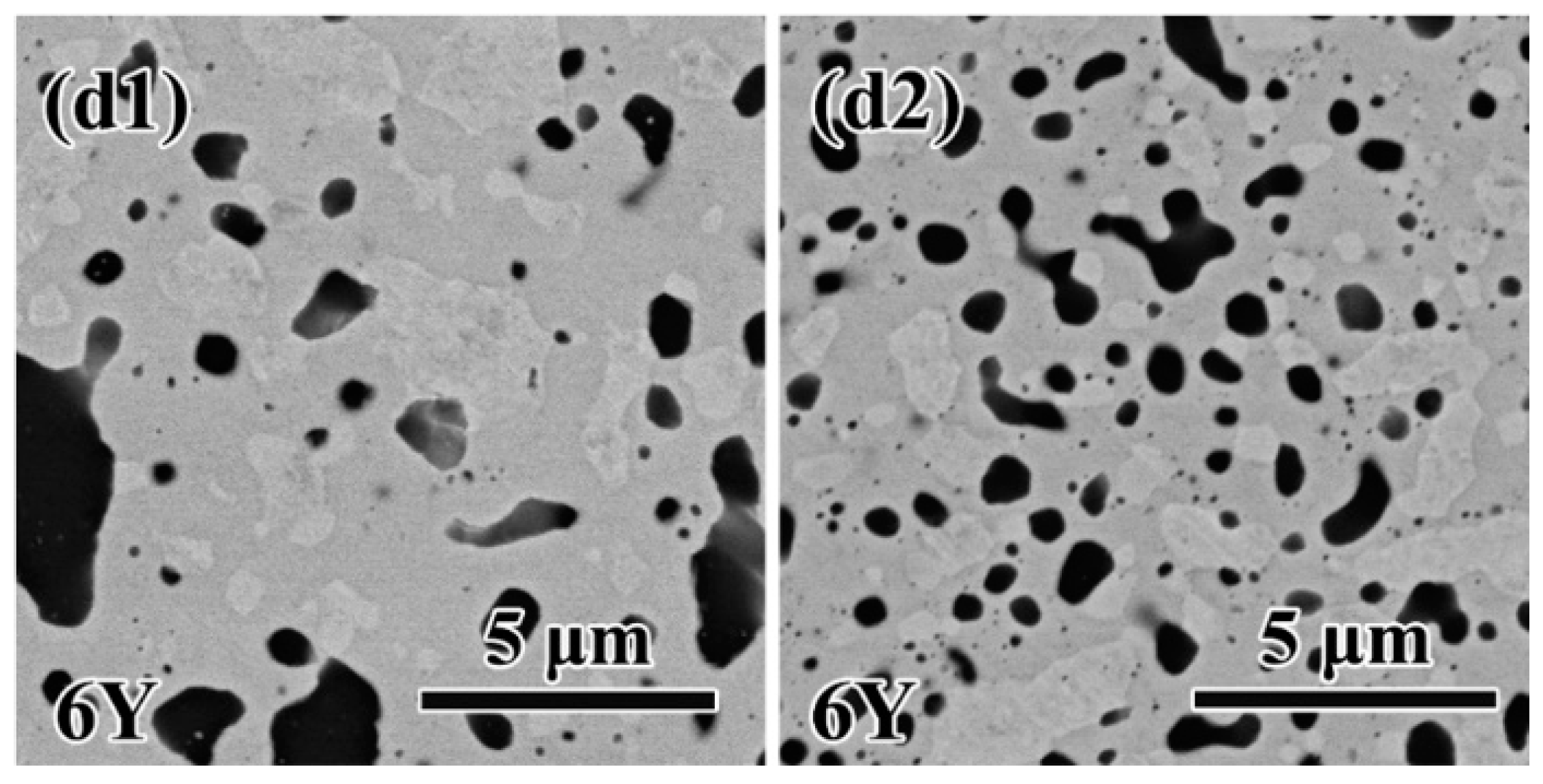

3.2. Microstructures of W-Si-Y sinter alloys

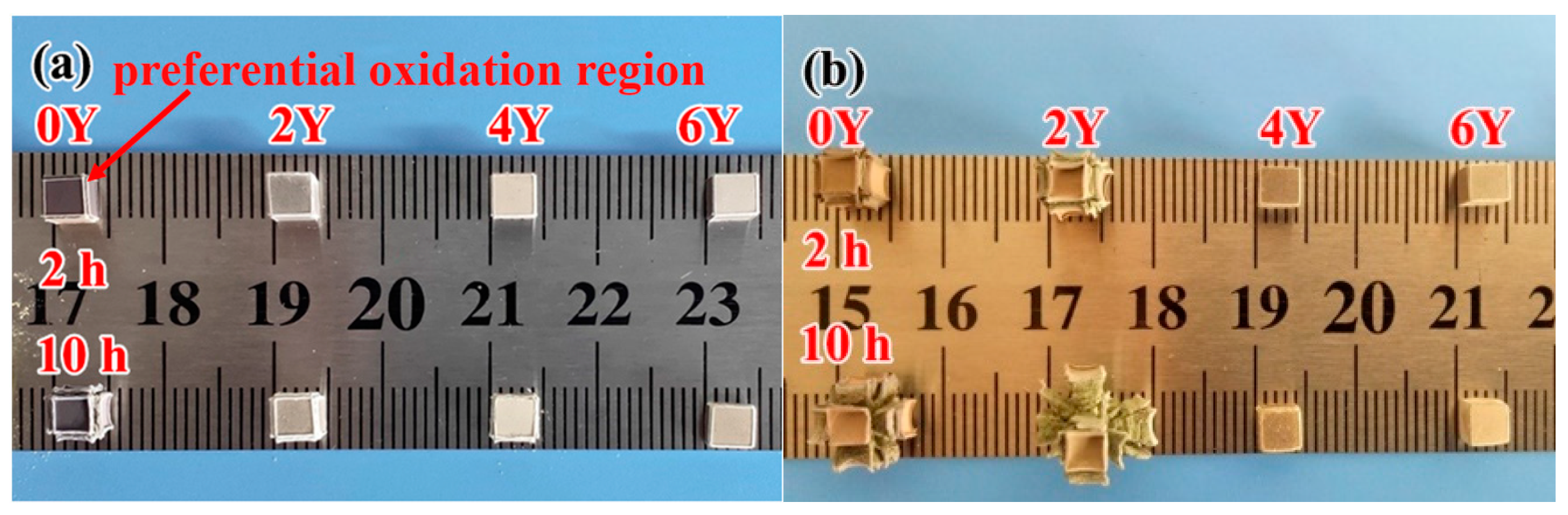

3.3. Oxidation tests

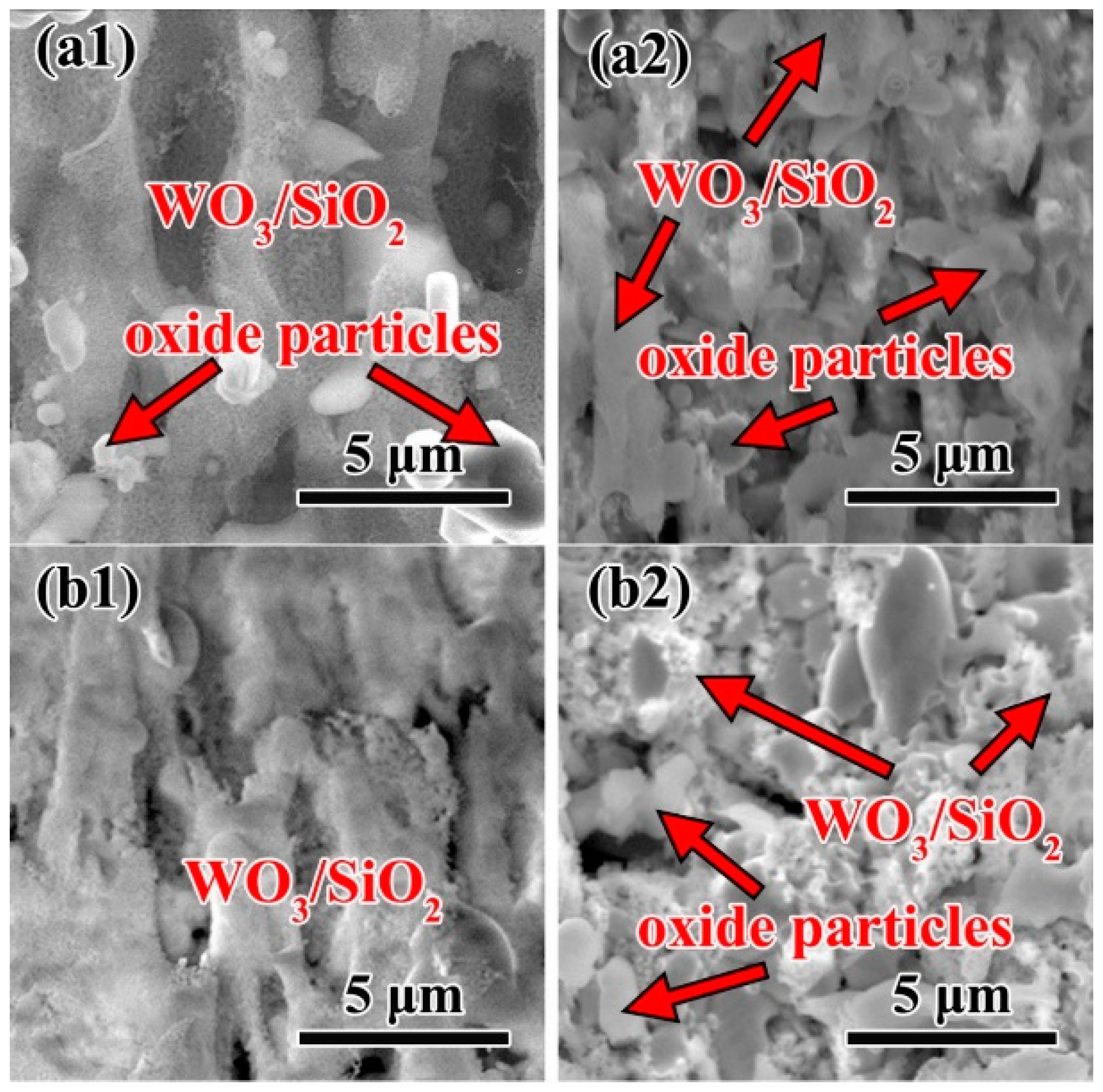

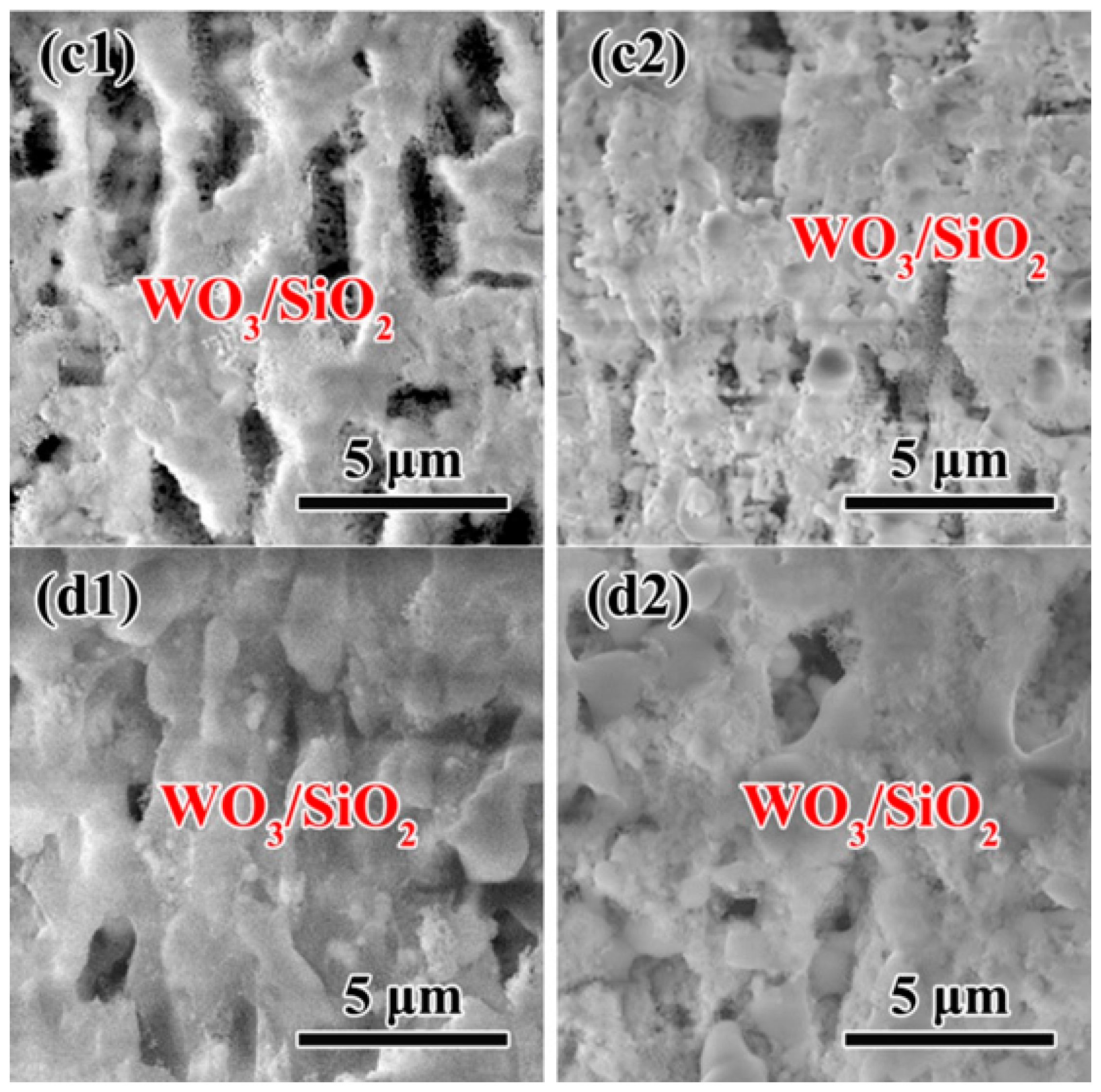

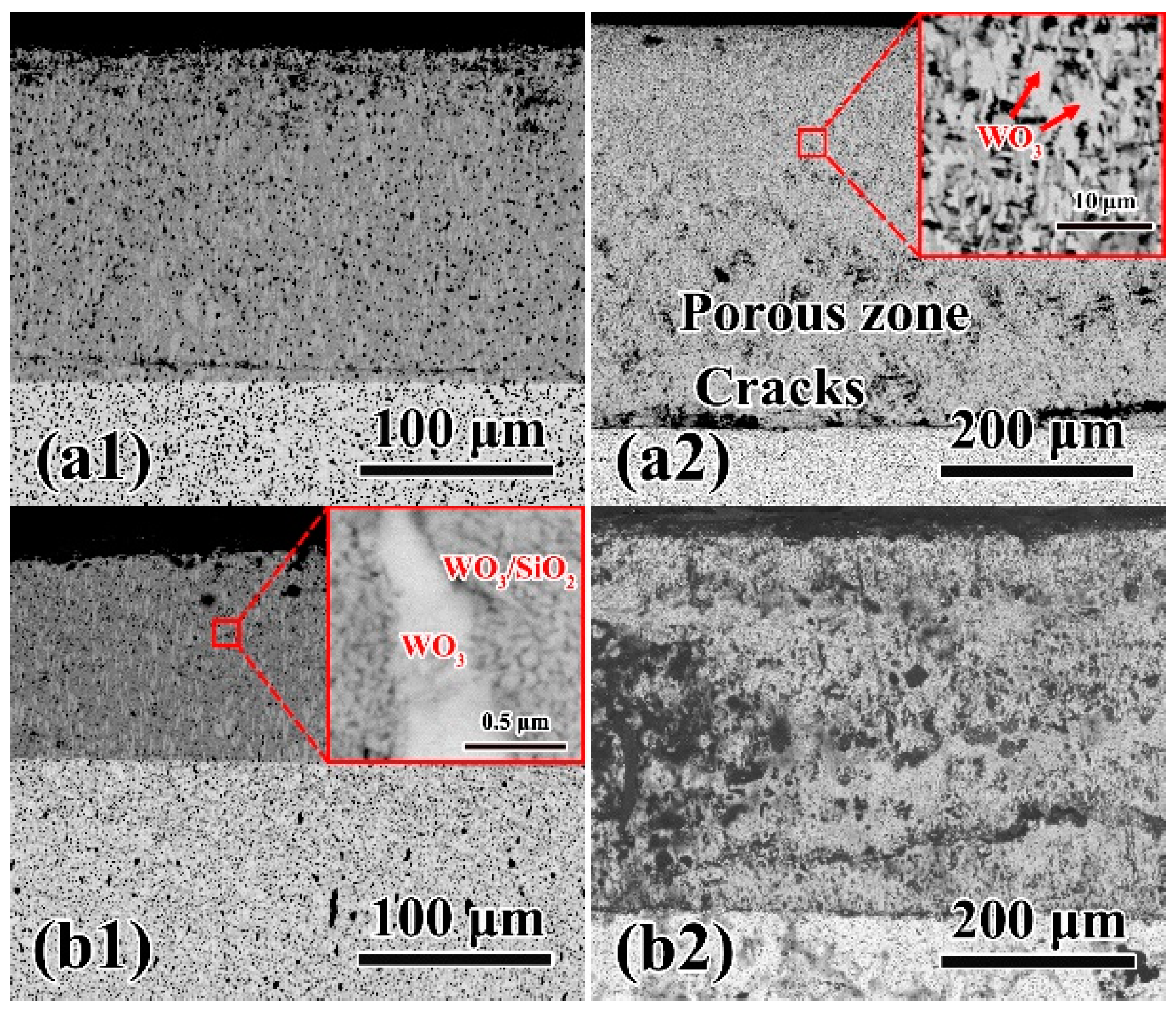

3.4. Microstructure of oxidation layer analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.J.; Peng, H.X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, G.M. Influence of ZrC content on the elevated temperature tensile properties of ZrCp/W composites. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2011, 528, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharchenko, V.; Bukhanovskii, V. High-temperature strength of refractory metals, alloys and composite materials based on them. Strength of Materials 2012, 44, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Bai, R.; Wang, D.H.; Cai, X.M.; Wang, F.; Xia, X.M.; Yu, L.J. Research Development of Refractory Metal Materials Used in the Field of Aerospace. Rare Metal Materials and Engineering 2011, 40, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmakov, A; Bannykh, I.; Antipov, V.; Vinogradov, L.; Sevost’yanov, M. Materials for bullet cores. Advanced Materials and Technologies, 2021, 4, 351-362. [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G.; Matteis, P; Scavino, G. Impact behavior and ballistic efficiency of armor-piercing projectiles with tool steel cores. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2018, 115, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Pitts, R.; Bonnin, X.; Escourbiac, F.; Frerichs, H.; Gunn, J.; Hirai, T.; Kukushkin, A.; Kaveeva, E.; Miller, M.; Moulton, D.; Rozhansky, V.; Senichenkov, I.; Sytova, E.; Schmitz, O.; Stangeby, P.; Temmerman, G; Veselova, I.; Wiesen, S. Physics basis for the first ITER tungsten divertor. Nuclear Materials and Energy. 2019, 20, 100696. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.Y.; Sun, J.R.; Gao, X; Wang, Y.Y.; Cui, J.H.; Wang, T.; Chang, H.L. Irradiation effects in high-entropy alloys and their applications. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2023, 930, 166768. [CrossRef]

- Bucalossi, J.; Achard, J.; Agullo, O.; Alarcon, T.; Allegretti, L.; Ancher, H.; Antar, G.; Antusch, S.; Anzallo, V.; Arnas, C . Operating a full tungsten actively cooled tokamak: overview of WEST first phase of operation. Nuclear Fusion. 2023; 62; 042007. [CrossRef]

- Philipps, V. Tungsten as material for plasma-facing components in fusion devices. Journal of Nuclear Materials. 2011, 415, S2-S9. [CrossRef]

- Habainy, J.; Iyengar, S.; Surreddi, K.; Lee, Y.; Dai, Y. Formation of oxide layers on tungsten at low oxygen partial pressures. Journal of Nuclear Materials. 2018, 506, 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Koch, F.; Bolt, H. Self-passivating W-based alloys as plasma facing material for nuclear fusion. Physica Scripta. 2007, T128, 100-105. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, T.; Klein, F.; Litnovsky, A.; Rasinski, M.; Brinkmann, J.; Koch, F.; Linsmeier, C. Development of yttrium-containing self-passivating tungsten alloys for future fusion power plants. Nuclear Materials and Energy. 2016, 9, 394-398. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Klein, F.; Litnovsky, A.; Wegener, T.; Schmitz, J.; Linsmeier, C.; Coenen, J.; Breuer, U.; Rasinski, M.; Li, P.; Luo, L.M.; Wu, Y.C. Evaluation of the high temperature oxidation of W-Cr-Zr self-passivating alloys. Corrosion Science. 2019, 147, 201-211. [CrossRef]

- Klein, F.; Gilbert, M.; Litnovsky, A.; Gonzalez-Julian, J.; Weckauf, S.; Wegener, T.; Schmitz, J.; Linsmeier, C.; Bram, M.; Coenen, J. Tungsten–chromium–yttrium alloys as first wall armor material: Yttrium concentration, oxygen content and transmutation elements. Fusion Engineering and Design. 2020, 158, 111667. [CrossRef]

- Sal, E.; Garcia-Rosales, C.; Schlueter, K.; Hunger, K.; Gago, M.; Wirtz, M.; Calvo, A.; Andueza, I.; Neu, R.; Pintsuk, G. Microstructure. oxidation behaviour and thermal shock resistance of self-passivating W-Cr-Y-Zr alloys. Nuclear Materials and Energy. 2020, 24, 100770. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Tan, X.Y.; Liu, J.Q.; Chen, X.; Wu, M.; Luo, L.M.; Zhu, X.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Mao, Y.R.; Litnovsky, A.; Coenen, J.W.; Linsmeier, Ch.; Wu, Y.C. The influence of heating rate on W-Cr-Zr alloy densification process and microstructure evolution during spark plasma sintering. Powder Technology. 2020, 370, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- de Prado, J.; Sal, E.; Sanchez, M.; Garcia-Rosales, C.; Urena, A. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of self-passivating W-Eurofer joints processed by brazing technique. Fusion Engineering and Design. 2021, 169, 112496. [CrossRef]

- Litnovsky, A.; Klein, F.; Tan, X.; Ertmer, J.; Coenen, J.; Linsmeier, C.; Gonzalez-Julian, J.; Bram, M.; Povstugar, I.; Morgan, T.; Gasparyan, Y.; Suchkov, A.; Bachurina, D.; Nguyen-Manh, D.; Gilbert, M.; Sobieraj, D.; Wrobel, J.; Tejado, E.; Matejicek, J.; Zoz, H.; Benz, H.; Bittner, P.; Reuban, A. Advanced self-passivating alloys for an application under extreme conditions. Metals. 2021, 11, 1255. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Wu, T.; Tian, L.H.; Lin, N.M.; Wang, Z.X.; Qin, L.; Wu, Y.C. Preparation of self-passivation W-Cr-Y alloy layer and its oxidation resistance. Heat Treatment of Metals. 2023, 48, 202-206. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Di, J.; Xue, L.H.; Li, H.P.; Oya, Y.; Yan, Y.W. Phase evolution progress and properties of W-Si composites prepared by spark plasma sintering. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2018, 766, 739-747. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Di, J.; Zhang, W.X.; Xue, L.H.; Yan, Y.W. Oxidation resistance behavior of smart W-Si bulk composites. Corrosion Science. 2020, 163, 108222. [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.Q.; Liu, W.; Ye, C.; Xue, L.H.; Yan, Y.W. A self-passivating W-Si-Y alloy: Microstructure and oxidation resistance behavior at high temperatures. Corrosion Science. 2021, 192, 109820. [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz, P.; Koch, F.; Ordás, N.; Lindig, S.; García-Rosales, C. Manufacturing of self-passivating W-Cr-Si alloys by mechanical alloying and HIP. Fusion Engineering and Design. 2011, 86, 1719-1723. [CrossRef]

- López-Ruiz, P.; Ordás, N.; Lindig, S.; Koch, F.; Iturriza, I.; García-Rosales, C. Self-passivating bulk tungsten-based alloys manufactured by powder metallurgy. Physica Scripta. 2011, T145, 014018. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Shen, J.; Ye, X.; Jia, L.; Li, S.; Umeda, J.; Takahashi, M.; Kondoh, K. Length effect of carbon nanotubes on the strengthening mechanisms in metal matrix composites. Acta Materialia. 2017, 140, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.G.; Zhai, T.T.; Yuan, Z.M.; Liu, F.C.; Feng, D.C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.H. Improved Electrochemical Performances of Ti-Fe Based Alloys by Mechanical Milling. International Journal of Electrochemical Science. 2023, 17, 221285. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ye, C.; Xue, L.H.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.W. A self-passivating tungsten bulk composite: Effects of silicon on its oxidation resistance. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials. 2021, 100, 105631. [CrossRef]

- Gulbransen, E.A.; Andrew, K.F. Kinetics of the oxidation of pure tungsten from 500° to 1300 ◦C. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 1960, 107, 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Telu, S.; Patra, A.; Sankaranarayana, M.; Mitra, R.; Pabi, S. Microstructure and cyclic oxidation behavior of W-Cr alloys prepared by sintering of mechanically alloyed nanocrystalline powders. International Journal of Refractory Metals & Hard Materials. 2013, 36, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Telu, S.; Mitra, R.; Pabi, S. Effect of Y2O3 Addition on Oxidation Behavior of W-Cr Alloys. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A-Physical Metallurgy and Materials Science. 2015, 46A, 5909-5919. [CrossRef]

| Alloys | Thickness(μm) | |

|---|---|---|

| 4 h of milling | 20 h of milling | |

| W-32Si | 173.6 | 413.8 |

| W-32Si-2Y | 108.1 | 395.7 |

| W-32Si-4Y | 104.7 | 84.0 |

| W-32Si-6Y | 83.6 | 70.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).