1. Introduction

“We know more about the Moon and Mars surface than

we do about the Ocean depths” is a common sentence when we speak about the

deep-sea environments. Truly, the deep Ocean is the largest unexplored place on

Earth—less than 5 percent of it has been explored so far. As of 2023, 24.9% of the global seafloor had been mapped

with modern high-resolution technology (multibeam sonar systems), usually

mounted to ships, that can reveal the seafloor in greater detail [

1]. Mapping the seafloor is crucial for sustainable ocean

management. It can be overwhelming thinking about mapping the entire seafloor

whilst 2023 is approaching, but this task is crucial to improving human life

[

2,

3]. The deep-sea habitats conditions are extreme to life but many species

physiologically adapted to cope with this challenging conditions. The

importance of a rigorous knowledge of ocean seafloor relies also on its

implication for coastal resilience and oceanographic implications. The

extensive exploration and the punctual knowledge of deep-sea environments is

crucial also for the understanding of climate-change impact on the global

carbon cycling pump mechanism [

4]. The biodiversity investigated and the exploration

outcomes highlighted in this contribution belongs to one of the less known

areas of the Pacific Ocean and its role as biodiversity hotspot can be crucial

even in the understanding of climate-related dynamics. To overcome the extant

knowledge gaps the expedition onboard the E/V Nautilus were planned considering

also the cultural aspect and the local ecological knowledge of indigenous

people, whose local traditions are inextricably connected to the Ocean and its

yet undisclosed lifeforms. This multiperspective approach [

5] is deeply in line

with the UN Decade of Ocean Sciences objectives, particularly the challenges:

2, 7, 8, 9 and 10 and the endeavors accomplished so far contributed to shed

light on Ocean Literacy Principle n. 7 which deliberately states “the Ocean is

largely unexplored”. The main target of this expedition season was the largely

unexplored northwestern section of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and the Kingman and Palmyra Atoll area which

fall within the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone.

2. Materials and Methods

The outcome of this paper comes from a research

experience joining the 2023 edition of the E/V Nautilus Ocean Exploration Trust

campaigns in the Pacific Ocean as scientist ashore. The exploration rationale

deeply focused on establishing a trust relationship with indigenous people. For

this reason, some representatives of the indigenous local communities have been

included in the cruise crew contributing to the toponyms’ identification, ROV

surveys and expedition routes planning. The cruise included high-resolution

habitat mapping and has been finalized including some videoconference sessions

to allow also the participation of more than a hundred of scientists even

operating remotely. All the exploration sessions occurred regularly engaging

the broader scientific community and public audiences via telepresence

technology.

2.1. Study area

The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument,

herein indicated as PMNM, is the largest conservation area established in the

United States Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and one of the largest marine

protected areas of the world, covering over 1.5 million square kilometers [

6]. Its designation dates back to June 2006. The

field data herein described belong to the NA153 and NA154 expeditions performed

during the field season 2023, near Johnston Atoll to map many unnamed seamounts

and seabed areas in the nearby. The images were obtained thanks to the ROV

Hercules dives along the Hawaiian Ridge and around the Gardner Pinnacles area (

Figure 1 a, b).

2.2. High resolution habitat mapping surveys

The expeditions season 2023 included some habitat

mapping surveys to fill the gaps on some uncharted portions of the investigated

area. Particularly the charting target were some seamounts to date identified

with numbers which required to be charted more in detail (6 of the 8

investigated seamounts were unexplored before). Both acoustic sonars and ROVs

were used to survey the northwesternmost and least explored portion of the

Monument (

Table 1).

The expedition completed 12 successful ROV dives

for a total dive time of over 264 hours and over 218 hours of seafloor

exploration. ROV dives focused on exploring deep environments relevant for

their conservation value. These include: seamounts (

Figure 2), ridges, and underwater cultural

heritage sites associated with the Battle of Midway. Dives surveyed seafloor at

depths ranging between 589-5,437 meters, which included the deepest dives ever

conducted off E/V

Nautilus [

7].

2.3. Native Hawaiian cultural protocol entering Papahānaumokuākea Monument

The NA154 leg of the 2023 Expedition focused on the most culturally valuable part of the exploration onboard the E/V Nautilus. Entering the Ala ‘Aumoana Kai Uli expedition, the crew was asked to observe a peculiar protocol to observe the Native Hawaiian values, practices, cultural protocols and respectfully engage with this ‘Āina Akua, a sacred realm, and the biological, geological, and archaeological elements found here, which are considered all cultural resources by locals.

Table 2.

Toponyms of explored areas during the NA154 expedition leg surveys.

Table 2.

Toponyms of explored areas during the NA154 expedition leg surveys.

| TOPONYMS OF MAPPED AREAS |

Ōiwi name |

English name |

Expedition leg |

| |

ʻŌnūnui, ʻŌnūiki

|

Gardner Pinnacles |

NA154

|

|

|

King George Seamount

Loudoun Seamount

Seamount 17*

Seamount 11*

Gambia Shoal |

NA154

NA154

NA154

NA154

NA154 |

3. Results

3.1. Benthic diversity detected during the expedition

The most relevant structure forming taxa characterizing the seafloor mapped during the expedition is the dominated by octocorals and sponges (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3).

Chrysogorgia and

Siphonogorgia are the main genera observed among soft corals (

Figure 3 a,b ). Among the hard corals Isididae spp. (

Figure 4) dominated the main benthic assemblages particulary in some unexplored seamounts detected during the NA154 expedition. Many colonies of the spiral corals belonging to the

Iridogorgia genus were also observed (

Figure 3 c-e).

Many glass sponges showing peculiar adaptations to the environmental conditions were observed [

8,

9,

10]. Among the Hexactinellid sponges detected some pedunculate euplectellid specimens belonging to the subfamily Bolosominae, bearing the main choanosomal spicules of diactins (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) resembling similar biodiversity patterns on other comparable seabed regions of the Pacific Ocean previously explored [

11].

The most representative groups of vagile fauna detected were: decapods crustaceans soft corals symbiont crabs (

Neolithodes sp.), squat lobsters, picnogonidae, jellyfishes (

Solmaris spp.), abyssal fishes (

Caunachops sp., toothy goosefishes) and echinoderms mainly represented by sea stars, soft-bottoms sea urchins and crinoids (

Figure 5 a-g).

Figure 5.

(a-g). Images of the most characteristic benthic organisms detected during the ROV dives.

Figure 5.

(a-g). Images of the most characteristic benthic organisms detected during the ROV dives.

Figure 6.

Glass sponges Bolosoma sp., Rossellidae sp. detected during the ROV surveys.

Figure 6.

Glass sponges Bolosoma sp., Rossellidae sp. detected during the ROV surveys.

Figure 7.

A glass sponge (family Euplectellidae) entrapping a small shrimp detected in the yet unnamed Seamount n.17 during NA154 expedition.

Figure 7.

A glass sponge (family Euplectellidae) entrapping a small shrimp detected in the yet unnamed Seamount n.17 during NA154 expedition.

3.2. The social value of local community engagement within the field expedition

The engagement of indigenous people beside giving insightful advices during the expedition, has been an unprecedented occasion to turn a language almost extinct into a cutting-edge source of knowledge, to fill the extant gaps into the deep-ocean exploration ad to enforce a trust relationship between the scientific world representatives and the locals holding cultural values on the area. This goal was accomplished through:

Onboard engagement of indigenous representatives

Teleconference shared presence

Pre-expedition documentation and route planning

Honoring the native indigenous knowledge is the main added value of the activities performed during this field expedition. Collaboration is at the basis of trust and the engagement of local people in seafloor exploration within the PMNM boundaries, beside adding values to the seafloor mapping itself, contributed also to the enforcement of the social dimension of scientific research and mapping endeavors aimed at filling the main deep-sea exploration gaps in the explored areas. The biodiversity patterns observed included many taxa holding a high ecological value. The strong relationship between the indigenous people and the Ocean is confirmed by the wide variety of terms specifically indicating marine organisms and the plethora of sacred figures belonging to the local traditions which have a strong relationship with the Ocean itself (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

The importance on relying on generational knowledge even in the field of deep-sea charting gaps filling is confirmed by the surprising event occurred in a deep portion of the PNMN where once deployed the Hercules ROV an endless field of precious pink corals unveiled to the investigators eyes. The deep-corals field is located around the Pō island, a sacred realm of gods and ancestral spirits, was supposed to be according to the local traditions (

Figure 8 a-f).

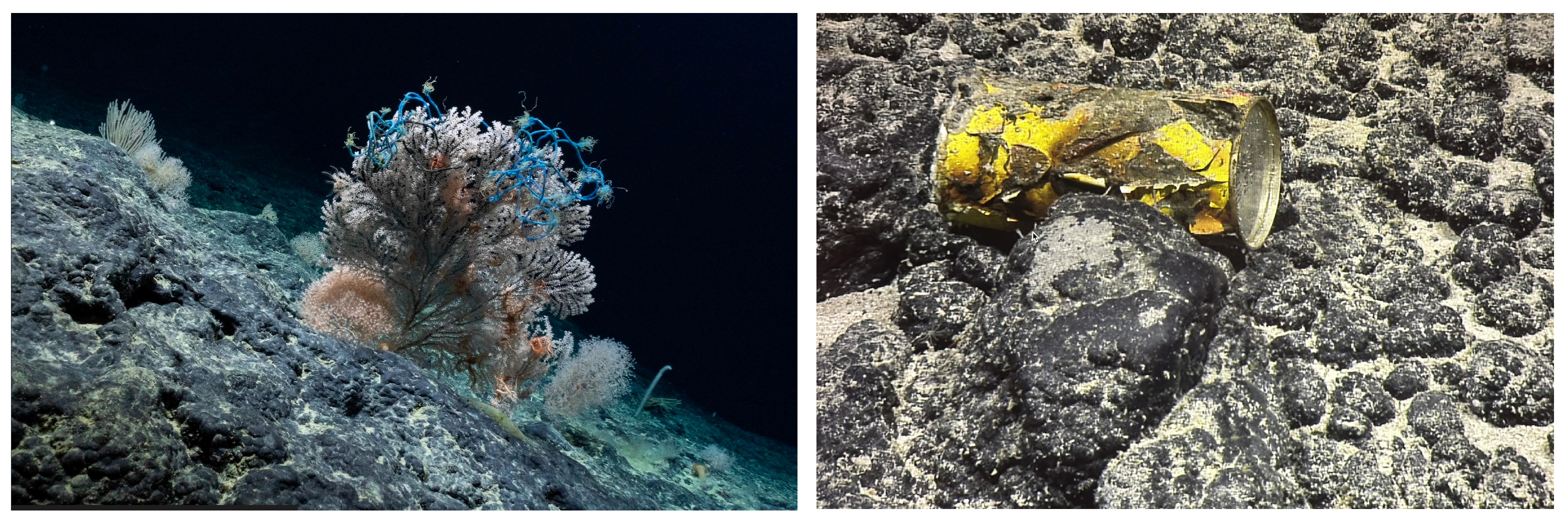

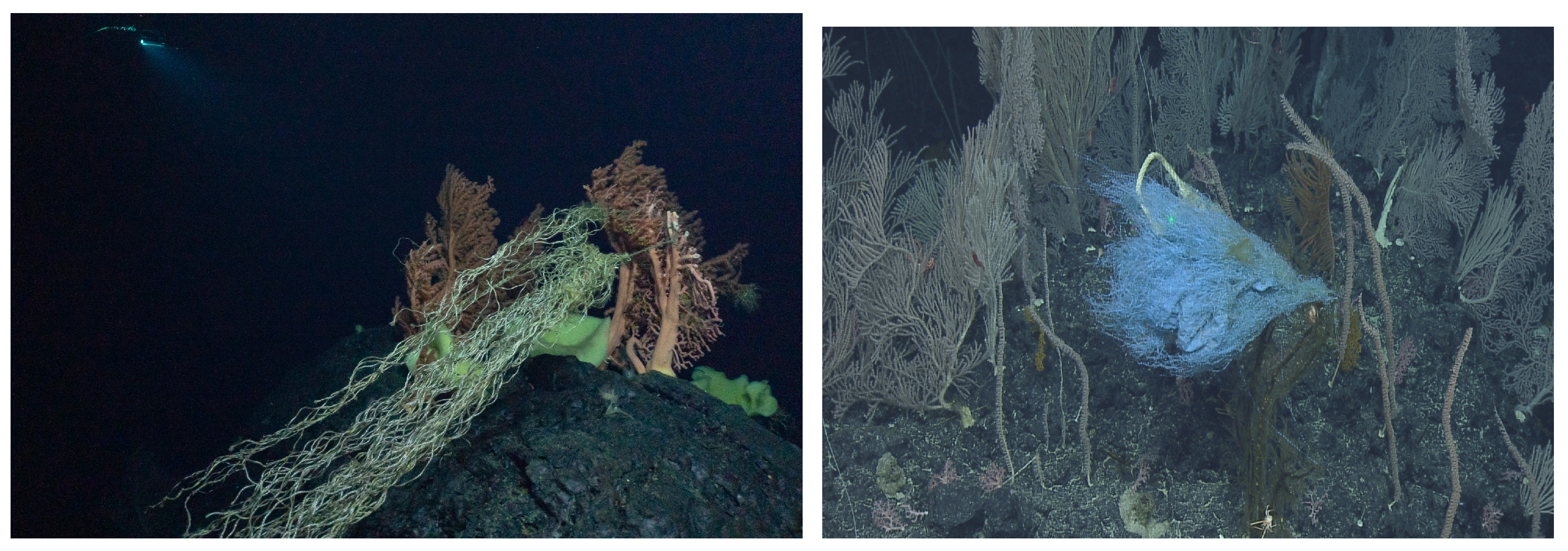

3.3. Human impacts detected along the ROV route

Despite the remoteness of the explored area some hints of human-driven impacts were detected during the ROV dives and charting sessions (

Figure 9 a-d). The most peculiar and visible debris detected in the deep portion of the PMNM were:

4. Discussion

Despite the advancements in technological tools and exploration endeavors many aspects of the deep-sea environments still being underknown. In the near future to fill the gaps in the most marginalized areas of the world what is important is establishing a trust relationship with local people, fostering at the same time the intangible and natural heritage preservation [

12]. This is what extensively happened during the Nautilus Expedition season 2023, where the local communities held a pivotal role in each stage of the field mission accomplishment. The generational knowledge and the traditional aspects of the local cultures are essential to drive the resilience of indigenous people, even facing with the upcoming challenges in facing the climate change issues and the biodiversity loss consequences, even in the deepest portion of the ocean which is expected to significantly warm up in the upcoming years [

13,

14]. According to the Deep Ocean Observing Strategy (DOOS) community-driven initiatives facilitating collaboration across disciplines and fields, is essential to foster an intergenerational and multicultural dialogues connecting scientific advancements to societal needs which will need a coordinated effort [

15].

Species richness normally decreases with depth in the ocean reflecting wider geographic ranges of deep sea than coastal species [

16]. Deepsea biodiversity show maximum richness at higher latitudes (30-50°) with diversity patterns usually reflecting the energy availability (Woolley et al.,). Also, deep-sea patterns depend on energy availability, this is why many benthic species such as the sponges or corals observed during the E/V Nautilus expedition in the deep-sea environment adapted some alternative metabolic strategies to come with the oligotrophic conditions of the deep-sea environments where they live. Differently to many corals and sponges detected in shallow waters here the organisms are all predators due to the absence of photosynthetic symbionts in their tissues. Among the other physiological and functional adaptation observed there is the mild or totally absent pigmentation of body cells (as in some cephalopods detected during ROV surveys), bigger and more specialized eyes, less bones in organisms’ skeletons and larger body sizes (as observed in many massive sponges or in some hermit crabs detected on the explored seafloor).

5. Conclusions

The outcome of this paper is a proof of a successful integration between exploration, educational goals fulfillment, scientific approach and cutting-edge technology use on field. This expedition marked a significant step ahead in deep-sea knowledge even toward the 2030 target goal for the attainment of an exhaustive ocean seafloor habitat mapping. The field activities performed so far allowed contributing to gathering data urgently needed to address local management and science needs of extant Natural Monuments as Papahānaumokuākea [

17] and likely candidates for new National Sanctuaries designations such as Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll, including a better understanding of the deep-sea natural and cultural resources, biogeographic patterns of species distributions, and seamount geological history. Whilst the expedition main focus was to explore the geology and biology of unexplored seamounts, the operating area included also several historically-significant shipwrecks associated with the Battle of Midway. By the way, for ethical reasons and in sense of respect for the victims engaged in this historically sounding event which dates back to the Second World War [

18,

19,

20] a special code of conduct was observed by every expedition participant and since its sharing goes beyond the aim of this paper these images won’t be showed in this occasion. The upcoming steps of deep-sea exploration hopefully will be addressed with the same attention for ethical aspects besides the scientific aims. The most sounding lesson learned from this experience with such an inspiring culture belonging to people who lived for millennia in harmony with the Ocean is their shared generational knowledge which allowed them to adapt and be resilient in the long term. Besides building trust with locals.

Funding

This research was funded by NOAA Ocean Exploration via the Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute within the 2023 field expedition season.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments are due to E/V Nautilus expedition team-mates, to Daniel Wagner as Chief Scientist of the expedition, Megan Cook as Director of Education and Outreach and to all the people engaged in the field season who made the data collection possible. Photo credits are due to: Ocean Exploration Trust, NOAA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The Ocean Exploration Trust and NOAA colleagues contributed to the data collection and positively evaluated the suggestion to publish the results and the expedition outcomes for outreach and dissemination purposes.

References

- Wölfl, A. C., Snaith, H., Amirebrahimi, S., Devey, C. W., Dorschel, B., Ferrini, V., ... & Wigley, R. (2019). Seafloor mapping– the challenge of a truly global ocean bathymetry. Frontiers in Marine Science, 283. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L., Jakobsson, M., Allen, G., Dorschel, B., Falconer, R., Ferrini, V., ... & Weatherall, P. (2018). The Nippon Foundation—GEBCO seabed 2030 project: The quest to see the world’s oceans completely mapped by 2030. Geosciences, 8(2), 63. [CrossRef]

- Smith Menandro, P., & Cardoso Bastos, A. (2020). Seabed mapping: A brief history from meaningful words. Geosciences, 10(7), 273. [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E., Burdon, D., & Shellock, R. J. (2023). The evolution of ocean literacy: A new framework for the United Nations Ocean Decade and beyond. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 186, 114467. [CrossRef]

- Hauck, J., Nissen, C., Landschützer, P., Rödenbeck, C., Bushinsky, S., & Olsen, A. (2023). Sparse observations induce large biases in estimates of the global ocean CO2 sink: an ocean model subsampling experiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 381(2249), 20220063. [CrossRef]

- Nautilus Live Website. Available online: https://nautiluslive.org/video/2023/12/19/2023-expedition-season-highlights-deep-sea-science-and-collaboration (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument website. Available online: https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/new-about/ (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- EcoMagazine website. Available online: http://digital.ecomagazine.com/eco-2023-dd3-deep-sea-exploration?m=9890&i=806038&p=34&ver=html5 (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Woolley, S. N., Tittensor, D. P., Dunstan, P. K., Guillera-Arroita, G., Lahoz-Monfort, J. J., Wintle, B. A., ... & O’Hara, T. D. (2016). Deep-sea diversity patterns are shaped by energy availability. Nature, 533(7603), 393-396. [CrossRef]

- Falcucci, G., Amati, G., Fanelli, P., Krastev, V. K., Polverino, G., Porfiri, M., & Succi, S. (2021). Extreme flow simulations reveal skeletal adaptations of deep-sea sponges. Nature, 595(7868), 537-541. [CrossRef]

- Schönberg, C. H. L. (2021). No taxonomy needed: sponge functional morphologies inform about environmental conditions. Ecological Indicators, 129, 107806. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C., Cheng, H., Zhang, D., & Wang, C. (2022). Two New Species and One New Genus of Glass Sponges (Hexactinellida: Euplectellidae and Euretidae), From a Transect on a Seamount in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9, 852498. [CrossRef]

- Strati, A. (2021). The protection of the underwater cultural heritage: an emerging objective of the contemporary law of the sea (Vol. 23). Brill.

- Sweetman, A. K., Thurber, A. R., Smith, C. R., Levin, L. A., Mora, C., Wei, C. L., ... & Roberts, J. M. (2017). Major impacts of climate change on deep-sea benthic ecosystems. Elem Sci Anth, 5, 4. [CrossRef]

- Danovaro, R., Fanelli, E., Aguzzi, J., Billett, D., Carugati, L., Corinaldesi, C., ... & Yasuhara, M. (2020). Ecological variables for developing a global deep-ocean monitoring and conservation strategy. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(2), 181-192. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. M., Cimoli, L., LaScala-Gruenewald, D., Pachiadaki, M., Phillips, B., Pillar, H., ... & Wright, D. J. (2022). The deep ocean observing strategy: addressing global challenges in the deep sea through collaboration. Marine Technology Society Journal, 56(3), 50-66. [CrossRef]

- Costello, M. J., & Chaudhary, C. (2017). Marine biodiversity, biogeography, deep-sea gradients, and conservation. Current Biology, 27(11), R511-R527. [CrossRef]

- Kekuewa Kikiloi, Alan M. Friedlander, 'Aulani Wilhelm, Nai'a Lewis, Kalani Quiocho, William 'Āila Jr. & Sol Kaho'ohalahala (2017) Papahānaumokuākea: Integrating Culture in the Design and Management of one of the World's Largest Marine Protected Areas, Coastal Management, 45:6, 436-451. [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, D. W. (2015). The Search for the Japanese Fleet: USS Nautilus and the Battle of Midway. U of Nebraska Press.

- Roth, M. J., Raupp, J. T., & Keogh, K. A. (2017). Exploring the Sunken Military Heritage of Midway Atoll. Underwater Cultural Heritage, 123.

- Allen, M. W. (2023). Midway Submerged: American and Japanese Submarine Operations at the Battle of Midway, May June 1942. Casemate.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).