1. Introduction

Earth’s biodiversity and ecosystem services are declining globally [

1]. An estimated one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction [

2]. A sixth mass extinction event is predicted if the unsustainable use of land, water, energy, and climate change continue unabated [

3]. In the last half-century, humans have degraded 75% of the land, 66% of the ocean, and 85% of the wetlands on Earth [

2]. Currently, 40% of all land has been converted for food production [

1]. After the failure to reach the 2010 and 2020 global biodiversity targets [

4,

5], will the United Nations (UN)’s Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) be our last hope to prevent massive biodiversity loss? Can Indigenous-led conservation help states achieve their GBF targets, succeed this third time?

The UN Kunming-Montreal GBF was signed by 196 countries in 2022 to reverse biodiversity loss through area-based conservation and ecological restoration by engaging Indigenous Peoples and local communities [

6]. The GBF’s first target aims “to bring the loss of areas of high biodiversity importance, including ecosystems of high ecological integrity, close to zero by 2030 while respecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities” [

6] (p. 9). The GBF’s third target is to conserve at least 30% of high biodiversity terrestrial, inland water, coastal, and marine areas by 2030 (30 by 30) “through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing Indigenous and traditional territories” [

6] (p. 9). Some progress has been made in protected and conserved areas (PCAs), covering 9.9% of the world’s oceans and 17.5% of the land and water globally as of 2025 [

7]. Nevertheless, more effort is needed from Canada and other countries, which are behind the target [

8]. The 30 by 30 GBF target acknowledges Indigenous rights, alongside six other GBF targets that mention Indigenous Peoples’ rights or roles (

Figure 1).

The UN prioritizes Indigenous Peoples’ roles and rights in biodiversity conservation under the GBF targets [

9]. The GBF’s 30 by 30 biodiversity target requires governments to recognize Indigenous rights as proclaimed by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) [

8]. By recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ rights, the GBF aims to transition area-based biodiversity conservation from displacing Indigenous Peoples from their land to recognizing their knowledge, innovation, rights, and roles as land stewards. Indigenous Peoples are effective protectors of biodiversity and ecosystems globally [

1,

2,

6,

10]. Comprising 6% of the global population, Indigenous Peoples govern at least 28% of the land on Earth [

11] and steward more than four-fifths of the global biodiversity [

1,

11,

12,

13]. Indigenous Peoples’ active stewardship of land and water has created biodiversity-rich landscapes.

Indigenous-governed conservation efforts through Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) are considered vital to achieving the GBF’s 30 by 30 area-based biodiversity conservation target [

14]. IPCAs can have a crucial role in land protection and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in settler colonial countries like Canada. Canada’s 2030 Nature Strategy adopted the GBF targets verbatim, including the commitment to uphold Indigenous rights [

15]. The 2030 Nature Strategy acknowledges Indigenous Peoples—First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Nation—as the stewards of land, water, and ice in Canada and aligns with Canada’s commitment to UNDRIP. Complying with UNDRIP is the 43rd call to action from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission [

16]. UNDRIP recognizes the self-determination, self-government, free and prior informed consent, and rights to ancestral land of Indigenous Peoples, along with many other inherent rights [

17]. Canada has enacted the UNDRIP Act, a federal law designed to ensure the legal implementation of UNDRIP within the country [

18]. Canada’s vast area, spanning almost ten million square kilometers (sq km) of land and water, requires massive conservation efforts. In early 2025, Canada protected 13.7% (1.37 million sq km) of its land and freshwater, and 14.7% (0.84 million sq km) of marine PCAs [

19]. Thus, Canada needs to protect an additional 16.3% (1.63 million sq km) of land and freshwater, and 15.3% (0.88 million sq km) of sea by 2030 [

5].

This paper examines the potential to protect 30% of Canada’s critical habitat by 2030 within IPCAs that honour Indigenous rights and UNDRIP. We map IPCAs and review IPCA agreements, considering ecologically important areas, mining interests, and Indigenous self-determination. We focus on Manitoba and northern Ontario to provide a close overview of IPCAs and mining before concluding.

2. Literature Review

This literature review explores the history of area-based conservation. It discusses how the GBF differs from earlier biodiversity targets. Additionally, the IPCAs are defined and examined to demonstrate how they require Indigenous leadership and self-determination.

2.1. The History of Area-Based Biodiversity Conservation

Area-based biodiversity conservation has historically excluded and displaced Indigenous Peoples, often contradicting Indigenous rights [

20,

21]. Protected and Conserved Areas (PCAs) have led to land grabs and the removal of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands in many colonized regions worldwide [

22,

23]. These land grabs by colonial governments accelerated after the 1980 World Parks Congress, which recommended that countries protect 10% of their land area [

24]. Excluding Indigenous Peoples from their territories resulted in displacement, loss of livelihoods, and erosion of culture. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted in 1992 at the first Earth Summit, recognized the connection of Indigenous and local communities to biodiversity and emphasized equitable sharing of benefits with them [

25].

Until 2020, the CBD’s strategic plan did not recognize Indigenous Peoples’ rights to self-determination and self-government, while states incorporated Indigenous territories within PCAs. The CBD’s 2002-2010 strategic plan reinforced the 1980 World Parks Congress’s protection target of 10% of the world’s land, primarily through protected areas [

4], without recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ rights. The CBD’s Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2011-2020 emphasized area-based conservation through PCAs, which included other effective conservation approaches alongside the protected areas [

24]. Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 aimed to protect 17% of land and freshwater and 10% of coastal and marine areas [

24], without mandating Indigenous rights and roles.

Indigenous rights to self-determination and self-government of PCAs have been recognized within the GBF [

26]. Before the GBF, CBDs reasserted states’ sovereignty over Indigenous territories, which contradicted the laws of Indigenous Peoples, notably in settler colonial states such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. The 30 by 30 area-based target builds on Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 from the CBD’s strategic plan for 2011-2020 [

27]. Further, the GBF prioritizes the rights and roles of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in biodiversity conservation, particularly in the 30 by 30 target [

21,

24].

2.2. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in Canada

Indigenous Peoples-led conservation of Indigenous ancestral lands is the crux of IPCAs [

23,

28]. The IPCAs protect the Indigenous ecological and cultural values of land and water, considering traditional land use and occupancy on ancestral lands. The term IPCA includes Indigenous-led other effective conservation measures, protected areas with Indigenous governance, or Indigenous-led area-based conservation.

The Indigenous Circle of Experts made three key requirements for IPCAs in Canada. The IPCAs are to be: “Indigenous-led,” involve a “long-term commitment to conservation,” and “elevate Indigenous rights and responsibilities” [

29] (p. 5). The First Nations, Inuit, and Métis in Canada are deeply connected to their Native land. Conservation through IPCAs is considered a “turning point” in the PCA model, strengthening Indigenous Peoples’ land-based activities [

30] (p. 201).

The IPCAs offer a means of land back. Land back through returning governance of Indigenous ancestral land and water is considered key to reconciliation and UNDRIP implementation [

31]. Land back affirms Indigenous Peoples’ rights to ancestral land guardianship, use, and governance [

32]. Land back is to rematriate Native land to Indigenous Peoples, which the Crown holds, without Indigenous Peoples’ consent, using executive and legislative power, as federal or provincial Crown land in Canada [

33]. Historic and numbered treaties with the Crown were made with most Indigenous Nations in Canada’s southern provinces. The Crown did not honor its treaty promises, controlling unceded Indigenous lands.

Canada claims legal control over Indigenous Peoples and their land through both the Constitution Acts of 1867 and 1982. Sections 91(24) and 92(5) of the Constitution Act (or British North America Act) 1867 and the Indian Act confer the Crown the power to control Indigenous Peoples and their land and grant exclusive powers to Canadian provinces to control provincial land, including land sales [

34]. This legal control through the sections 91(24) and 92(5) contravenes Indigenous Peoples’ rights to own, occupy, develop, conserve, and control their land, which is UNDRIP’s Article 26 [

17]. Also, these laws contradict Indigenous Peoples rights to declare their ancestral land as IPCAs, according to UNDRIP’s Article 29. Canadian Constitution and laws, such as the Indian Act, break the true intent of the Crown’s treaty promises to Indigenous Peoples in the historic and numbered treaties.

Some Indigenous Nations in Canada see IPCAs as crucial for stewarding and protecting their ancestral land from Canada’s colonization and industrial development [

28,

35,

36]. The IPCAs incorporate Indigenous land guardianship through land-based learning, spirituality hunting, fishing, trapping, harvesting, and cultural ceremonies [

23]. IPCAs are about Indigenous Peoples’ reconnection to their ancestral land [

29] and access to their ancestral land, food, wood, medicine, and sacred sites [

37]. Protected areas displaced Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral land under Canada’s genocidal colonial policies, including the Indian Act

Canada first mentioned IPCAs in its sixth national report to the CBD in 2018 [

38]. However, Canada considered IPCAs too ambitious for their 2020 target, requiring extensive consultations with Indigenous Peoples and the negotiation of land claim agreements. The IPCA approach was lobbied for by the Indigenous Peoples in Canada and other geographies to be enshrined in the GBF’s 2030 targets and verbatim in Canada’s 2030 Nature Strategy,

recognizing and respecting Indigenous rights.

3. Materials and Methods

This research explored the potential of IPCAs to help Canada meet its 30 by 30 GBF target and fulfill its UNDRIP commitments for Indigenous self-determination. We begin by assessing Canada’s progress on the GBF and Aichi Biodiversity targets, with a focus on Indigenous Peoples. The progress of the GBF for area-based conservation is mapped for PCAs and IPCAs, considering ecologically important areas (like peatlands), mining interests (such as greenstone belts), and Indigenous self-governance (like PCA governance). To illustrate how Indigenous-led IPCAs can protect ecologically significant areas, this research provides a close overview of IPCAs in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario.

3.1. Data Gathering

3.1.1. Protected and Conserved Area (PCA) data gathering for Canada

We gathered data from the 2024 PCA database of the Canadian federal government’s Department of Environment and Climate Change Canada [

39]. This database does not include the proposed IPCAs. Proposed IPCAs were accessed on ArcGIS Online and digitized for Wildlife Conservation Society Canada using Canada’s database [

40]. Boundaries for provinces, territories, and the Seal River watershed were retrieved from Esri’s Living Atlas [

41]. The greenstone belt feature layer was accessed through ArcGIS Online as “Canada_Greenstone_Belt.” The critical minerals advanced projects, mines, and processing facilities were accessed through Open Data Canada [

42].

3.1.2. Peatland Analysis for Canada

For peatland areas, we accessed the Tag Image File Format (TIFF) raster database curated and shared by Hugelius and colleagues for northern countries [

43]. The raster database had a resolution of 100 sq km and over 7,000 peat cores with peat depth data, the global soil grids 250m dataset, and harmonized national and regional soil maps [

44].

3.1.3. Vegetation Data Gathering for Manitoba

A vegetation analysis of Manitoba, rather than Canada, was undertaken due to time constraints. For the Manitoba vegetation map, we accessed Sentinel 2 images covering June 1st to August 31st

, 2024, using the Geemap Python package [

44] in Visual Studio Code version 1.100. A cloudy pixel percentage of 5% was set, which filtered 1056 suitable images for analysis. A cloud mask was applied to the image collection, and a median normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was computed to measure land health based on vegetation cover [

45]. The Python code was generated in Deepseek for a 2024 summer vegetation NDVI map. The Deepseek-generated codes were verified and adjusted manually.

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Analyzing Data to Form Maps

We used ArcGIS Pro 3.3.2 to analyze spatial data and prepare maps in the Canada Albers Equal Area Conic coordinate system. For Manitoba, we used the projected coordinate system that uses North American Datum 1983 Universal Transverse Mercator Zone 14 North (NAD 1983 UTM Zone 14N). In ArcGIS Pro, we imported several feature layers from ArcGIS Online and provinces and territories of Canada from Esri’s Living Atlas layer to obtain the provinces and territories of Canada, providing credit for each data source. We calculated zonal statistics by using “summarize data” in ArcGIS Pro to calculate the areas and overlaps.

3.2.2. Analyzing Data to Calculate Impacts

We used proximity analysis tools to calculate the overlaps and impacts. The clip tool extracted the overlap of PCAs with greenstone belts and buffers for each province and territory. The buffer tool estimated the land and water impacted if greenstone belts were mined. The buffers were consolidated into a single feature. To model the mining impact, we calculated a 1 km and a 50 km buffer around each greenstone belt boundary. The 1 km buffer includes the immediate impact areas due to structural collapse, oil and chemical spills, water contamination, etc., from mining activity, while the 50 km buffer indicates the large footprint of mining projects for not only pollution but their requirement for utility corridors, access roads, transfer stations, site preparations, including draining of lakes, accommodating skilled workers flown in and tailing ponds [

46,

47].

For peatland maps, the raster TIFF files were reclassified at equal intervals of ten to calculate areas. The raster pixels for Canada were masked using the Extract by Mask tool. After extraction, the raster pixels for Canada were converted into polygons using the raster-to-polygon tool. Peatlands overlapping with greenstone belts and PCAs were clipped to assess the impact of mining and current protection through PCAs. For the NDVI map, the “greater than or equal to” tool was used to extract NDVI pixel values of 0.6 and above to show the dense vegetation cover areas in Manitoba during summer 2024.

4. Results and Discussion

First, an analysis is provided of Canada’s progress on the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the GBF, focusing on Indigenous Peoples. Then, we discuss PCA governance. Additionally, we complete an examination of the potential of IPCAs in reaching the 30 by 30 GBF target three and in protecting ecologically important areas, especially peatlands, from mining interests.

4.1. Canada’s Progress on Indigenous Peoples-related Biodiversity Targets

Table 1 shows that one-third of the GBF targets focus on Indigenous Peoples. Although the paper’s focus is target three, the focus of other targets on Indigenous People is noteworthy. For example, target five is supported by Canada’s implementation of laws to protect wild species, incorporating mechanisms for Indigenous Peoples’ customary use, and improving access. Also, Target 22 requires respecting Indigenous People’s territory and People, which is foundational to IPCAs. Progress on Target 22 has been made by Canada with its UNDRIP Act Action Plan, collaboratively developed with Indigenous Peoples, for the implementation of UNDRIP in Canada.

Table 1 shows that progress has been made for all Canada’s Nature Strategy targets. However, the spatial planning (target one) and area-based conservation (target three) is less than halfway towards their targets. In 2024, 36,500 sq km of PCAs are under different levels of Indigenous governance.

4.2. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in Canada

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) exist in Canada. Four PCAs were documented as IPCAs in Canada’s 2024 PCA database. Through Indigenous-led area-based conservation programs, Canada provided some limited funding to develop 62 IPCA proposals.

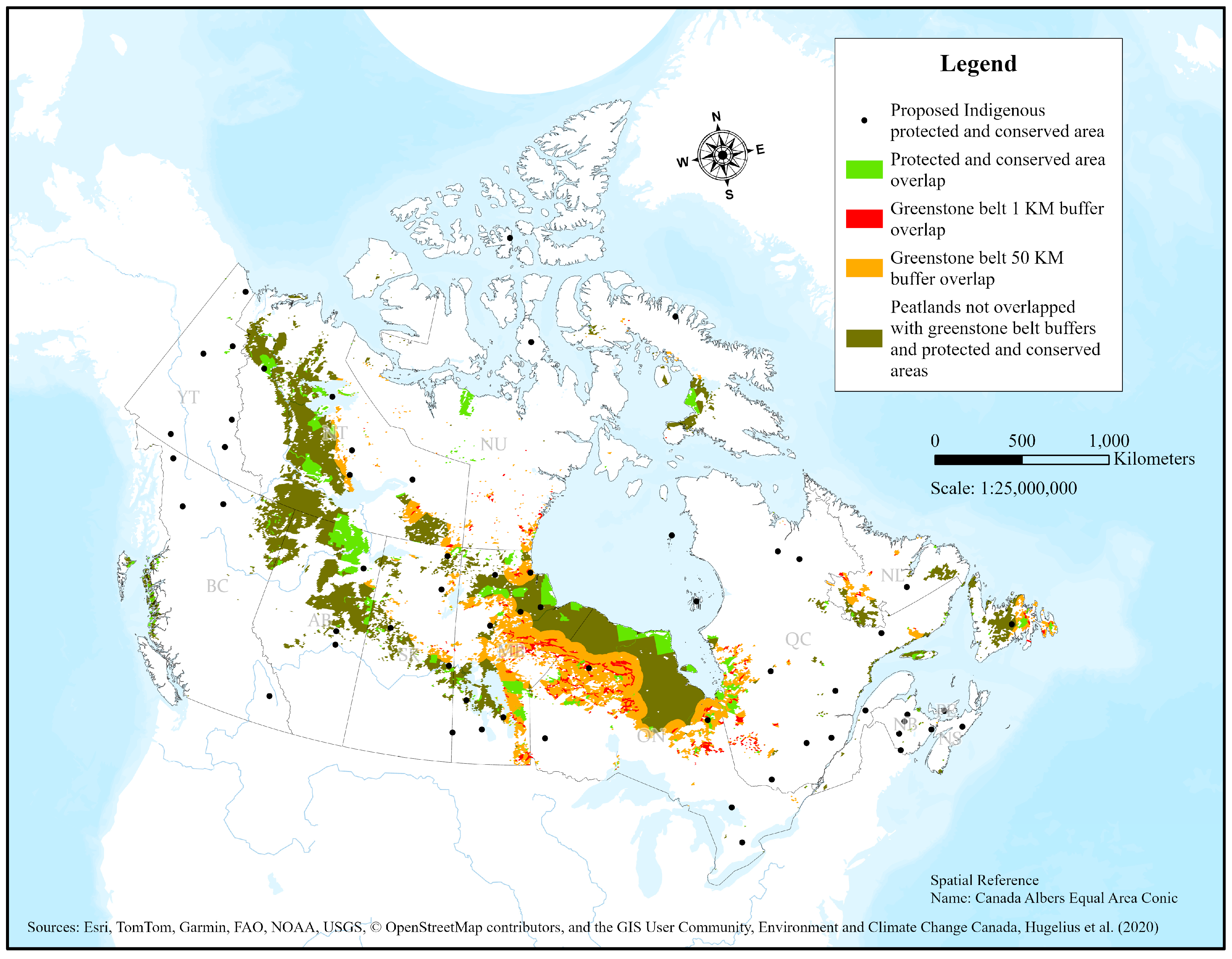

Figure 2 shows the four IPCAs, 62 proposed IPCAs, and non-Indigenous PCAs. PCAs occupy 2.24 million square kilometers (sq km) of land and water in Canada. The four IPCAs cover 31,500 sq km, comprising 1.5% of Canada’s PCAs and 0.3% of Canada’s total area. Three of the four IPCAs are in the Northwest Territories, which include the Ts’udé Niljné Tuyeta Territorial Protected Area (10,100 sq km), Thaidene Nëné Territorial Protected Area (9,102 sq km), and Edéhzhíe Protected Area (12,249 sq km). The Gwa̱xdlala/Nala̱xdlala (Lull/Hoeya) marine refuge (21 sq km) in British Columbia is a coastal Pacific marine IPCA.

Canadian law administers the four IPCAs in

Figure 2 as Crown land through territorial parks, habitat protection areas, and similar designations. Although some provinces, such as Quebec’s Natural Heritage Conservation Act [

50] and Nova Scotia’s Environmental Goals and Climate Change Reduction Act [

51], include provisions for Indigenous-led PCAs, the IPCAs are on so-called Crown lands according to the Indian Act and provincial Crown land laws [

33] so are not fully Indigenous governed. Although the Canadian PCA database lists these four PCAs as IPCAs, the Canadian government has designated them as territorial protected areas, wildlife conservation areas, national wildlife areas, and habitat protection areas, among others. According to the Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (also known as the White Paper), 1969, the Canadian government, as the land trustee, supervises all matters related to the land in Canada [

52]. Unless Indigenous governments self-determine and self-govern PCAs on their ancestral land, the PCAs are not truly IPCAs because a Crown trustee takes away Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination over their land [

53,

54]. Furthermore, the Crown Land Acts of Canadian provinces do not acknowledge the inherent and treaty rights of Indigenous Peoples to their ancestral land [

55,

56].

4.2.1. Indigenous Peoples Governed PCAs

Indigenous Peoples legally hold land rights to only 0.23% (5,000 sq km) of PCAs in Canada. This land right constitutes 0.05% of the country’s total area.

Figure 3 shows Canada’s 12 types of legal ownership for PCAs [

57]. Indigenous Peoples in Canada self-govern only four PCAs.

Indigenous governments self-govern and self-determine the PCAs mapped as Indigenous-owned. The four IPCAs shown in

Figure 3 are all located on modern treaty lands. Indigenous governments enact their laws and protocols on modern treaty lands (land claim agreements or self-governance agreements). The respective Indigenous Nations have declared these lands as IPCAs, which appears to meet the Indigenous Circle of Experts’ definition of an IPCA, i.e., Indigenous-led, long-term conservation commitments and the elevation of Indigenous rights.

One IPCA is in the Northwest Territories and three are in Yukon. In the Northwest Territories, the Tłįchǫ Government governs Wehexlaxodıale (976 sq km) under Tłįchǫ law and protocol through a self-government agreement in 2003 [

58] and has protected two historical areas—Gots’ôkàtì (Mesa Lake) and Hoòdoòdzo (Wolverine Hill and Sliding Hill)—as Wehexlaxodiale IPCA in 2013 [

59]. In Yukon, the Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation governs Tsâwnjik Chu (Nordenskiold) (77 sq km) under a collaborative governance model on the First Nation’s settlement land parcel R-2B [

60]. In comparison, the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation owns Van Tat K’atr’anahtii (Old Crow Flats) (3,947 sq km) and Ni’iinlii Njik (Fishing Branch) (140 sq km) PCAs in Yukon within the self-government agreement land under the First Nation’s jurisdiction [

61]. The Yukon government, under the Wildlife Act of 1986, supported the Vuntun Gwitchin’s IPCAs through the Nordenskiold Wetland Habitat Protection Area agreement, which requires Canada to withdraw mining, oil, and gas claims, leases, interests, or rights and to stop new licenses, permits, and other rights [

60]. Modern treaty lands are not the Crown land within the meaning of the Constitution Act, 1867-1982, and/or the Indian Act, so modern treaties facilitated Indigenous self-determination of IPCAs. However, modern treaties as such are not the panacea for Indigenous self-determination in Canada.

Modern treaties should enable every aspect of Indigenous self-determination and self-government, recognizing Aboriginal titles to traditional territory, but modern treaties have some flaws [

62,

63]. Canada has signed 29 modern treaties with Indigenous governments, covering 40% of the country’s area, almost exclusively situated in the far north [

64]. Modern treaties are criticized as the settler government’s strategies for extinguishing Aboriginal title to traditional territory in Canada, to continue exploiting Indigenous lands and waters for Canada’s economic accumulation [

63]. Canada imposes taxes on the citizens of Indigenous governments and corporations operating within the self-government land, while reducing federal fund transfers [

62]. The pros and cons need to be weighed carefully when facilitating IPCAs through the fast-tracking of modern treaties.

4.3. Significance of IPCAs for Canada to Meet 30 by 30 Targets and Indigenous Rights

Can the area-based conservation under IPCAs protect millions of acres of land, water, and ocean in Canada? Possibly. To achieve the 30 by 30 target, Canada requires 1.63 million sq km of land and freshwater ecosystems as well as 0.88 million sq km of ocean and coastal ecosystems by 2030 [

5]. The proposed IPCAs aim to protect at least 0.5 million sq km (5%) of land and water [

65]. Although the exact areas are not officially reported, if we consider the areas of proposed IPCAs for the land category, these are estimated to increase the protection of land to about 19% (1.87 million sq km) [

19]. Still, Canada needs to protect an additional 1.1 million sq km in less than five years, while respecting Indigenous rights.

Canada has provided short-term funding for 62 IPCAs [

40], but their long-term protection is uncertain. These IPCAs cover vast regions. For instance, an IPCA funding in the Northwest Territories covers 0.2 million sq km of land and water [

66]. The Seal River Watershed Indigenous Protected Area in northern Manitoba encompasses 50,000 sq km of land and water, with five Indigenous Nations collaborating to protect critical ecosystems in the watershed from wildlife decline, mining encroachment, hydro dams, and road construction [

36]. The Simpcw First Nation in British Columbia has self-declared Raush Valley an IPCA to conserve biodiversity and uphold their traditional land uses [

35,

67]. Five Ininew Nations—York Factory, Fox Lake, Tataskweyak, Shamattawa, and War Lake—have begun an IPCA named “kitaskeenan kweekanawaynichikatek: our land we want to protect” to protect over 46,600 sq km of their ancestral land from hydro dams and mining [

68,

69]. Through IPCAs, Indigenous Nations aim to protect their ancestral land and vital ecosystems primarily from extractive industries and to exercise their rights to self-determination and self-government of ancestral land [

65]. More IPCAs can help safeguard ecologically vital areas from greenstone belt mining and contribute to the 30 by 30 GBF target. As IPCA agreements require the removal of existing resource extraction claims, these provide the potential for protecting ecologically important mining areas, even green stone belts [

60,

70,

71,

72].

4.3.1. Protecting Greenstone Belts’ Ecologically Important Land Through IPCAs

Greenstone belts are vast rock formations rich in gold and other critical minerals, covering a large part of northern Canada [

73]. These zones comprise 2% of Canada (0.4 million sq km), which is 1.6 times the size of the United Kingdom. Mining in greenstone belts affects a much larger area because mining requires energy, water, land, roads, and settlement. Canadian federal and provincial governments’ mining interests in greenstone belt regions challenge land protection efforts in Manitoba, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Ontario, and Quebec.

Land use planning for PCAs must avoid greenstone belts to gain acceptance.

Figure 4 shows that funded IPCAs bypass greenstone belts and how their nearby areas threaten biodiversity. By avoiding these belts, only 1.75% (39,200 sq km) of Canada’s PCAs protect biodiversity in greenstone belt regions. However, greenstone belts with a 1 km buffer for mining pollution and development overlap with 40% (890,000 sq km) of existing PCAs. At a 50 km buffer, the larger ecological footprint of mines covers 24% (3.8 million sq km) of Canada’s land and water, overlapping with 50% (1.13 million sq km) of existing PCAs. Therefore, mining land impacts are estimated to affect 3,114 PCAs, 1 IPCA, and 20 proposed IPCAs. Globally, half of the world heritage sites, including the Pimachiowin Aki located south of Island Lake in Manitoba, overlap with the 1 km boundary of at least one of the mining, oil, and gas extraction sites [

74].

Areas near greenstone belts often lack funded IPCA proposals.

Figure 4 shows that the greenstone belts in northeastern Manitoba and northwestern Ontario lack funded IPCAs proposals. Northwestern Ontario has 15 advanced critical mineral projects, with more expected in Ontario’s Ring of Fire and Manitoba’s Island Lake region. This vast area, home to many First Nations, is a focus for mining development and holds significant economic potential for Canada and the global mining industry. The prioritization of mining land use over conservation and Indigenous Peoples’ land uses explains why Manitoba’s Island Lake IPCA proposal was rejected, and only two proposed IPCAs received funding in northwestern Ontario.

Mining rights and Indigenous Peoples’ rights clash. Canada’s legal system for registering mining claims on land, known as the free entry system, is deeply problematic for conservation and Indigenous rights. Mining claims are made without Indigenous Peoples’ free, prior, and informed consent on Indigenous territories, called Crown land under Canadian law [

75]. The free entry system infringes on Indigenous self-determination in Canada [

76,

77,

78]. In June 2025, Canada passed Bill C-5 for the Building Canada Act to expedite projects of national interest, including resource extraction projects, despite rejection from Indigenous leaders and human rights organizations [

79].

4.3.2. Indigenous Guardianship of Peatlands Through IPCAs

Peatlands are vital for regulating the Earth’s climate, as they are the most significant terrestrial carbon sink. These ecosystems store significantly more carbon than other vegetation types combined and are essential for wildlife and Indigenous food sources [

80]. Canada has 1.61 million sq km of peatlands with ≥50% peat per unit area and 2.5 million sq km with ≥30% peat. Manitoba, Ontario, and the Northwest Territories contain 0.33 million sq km of critical peatlands with a peat proportion of 80% or greater. Canada’s Native land hosts the most extensive peatlands in the world [

81]. However, only 10% of peatlands are conserved under existing PCAs in Canada [

82], compared to 19% globally [

81]. Due to their importance in ecological regulation, peatlands should be protected within existing PCAs or proposed IPCAs.

Much of Canada’s peatlands need to be in PCAs [

82]. However, existing PCAs conserve only 13.5% of peatlands in Canada and exclude all the critical peatlands with a proportion of ≥80% peat. Peatlands with 100% peat occupy 2,553 sq km of land in Canada, yet current PCAs conserve less than one sq km (0.03%) of this type of peatland. Canada’s vast peatlands support biodiversity and store five times more carbon than the Amazon rainforest [

44,

80]. If half of the peatlands with more than 30% peat were protected, and all the proposed IPCAs were implemented, Canada would meet its 30 by 30 GBF target on high-priority lands.

Protecting Canada’s peatland extraction is crucial for enhancing carbon storage and preventing biodiversity loss [

44,

80,

81]. These peatlands to protect include the Hudson Bay lowland ecoregion in northern Ontario and Manitoba [

44,

80,

81], which face substantial threats from the mining of greenstone belts in Canada.

Figure 5 shows the peatlands (≥30% peat) and greenstone belts overlap, which is directly at 3% (0.07 million sq km), expanding to 4% peatlands (0.1 million sq km) for a 1 km buffer and 33% peatlands (0.82 million sq km) for a 50 km buffer. Peatlands in Ontario, Manitoba, Quebec, and Saskatchewan are vulnerable to the impacts of land use changes due to greenstone belt mining. Mining infrastructure and impacts can destroy peatlands due to mining pits, road construction, hydro development, and indirectly through water fluctuation, pollution, and land degradation [

81].

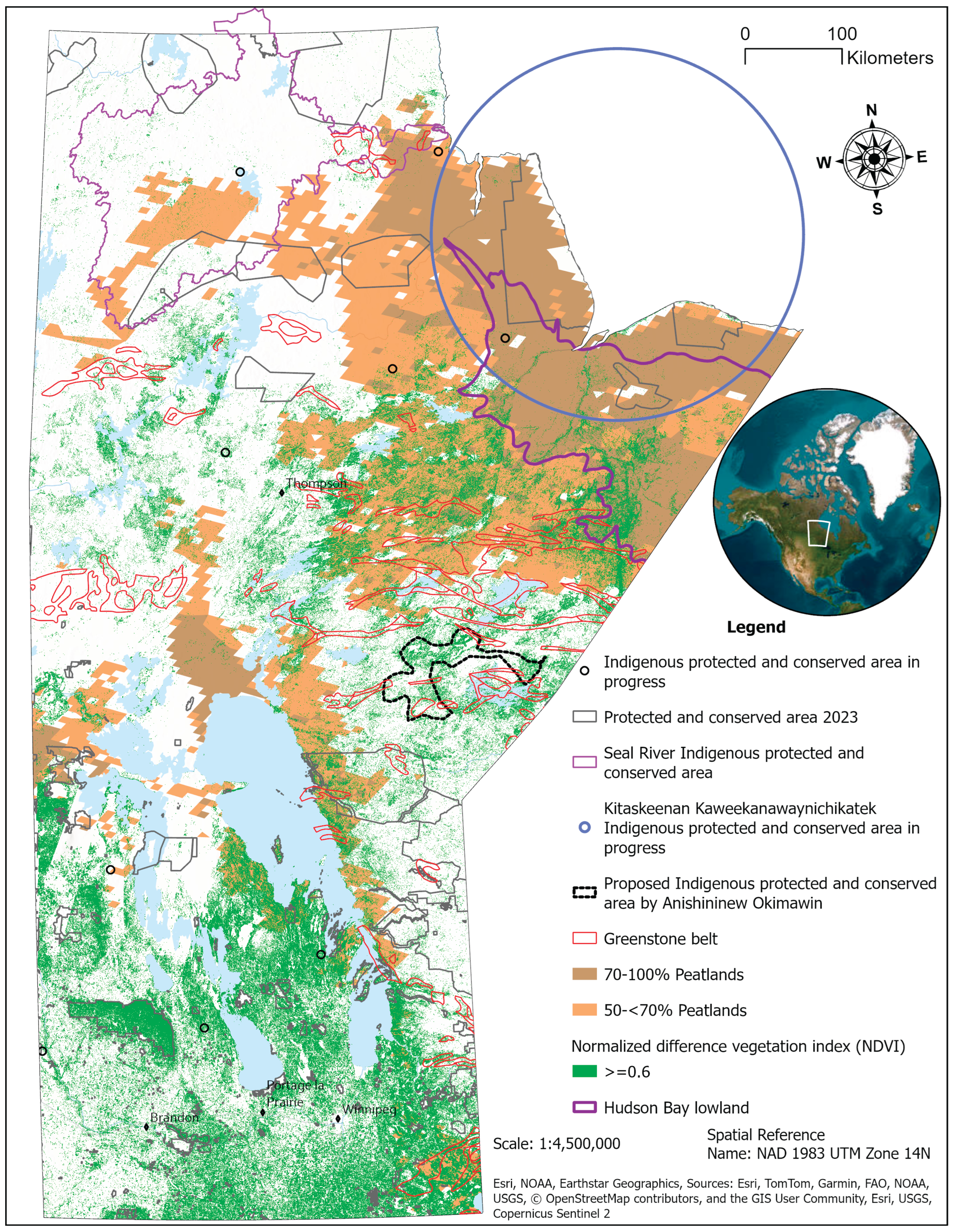

Mining interests in northeastern Manitoba and Ontario’s Ring of Fire threaten some critical peatlands, which are largely unprotected [

83,

84]. These Hudson Bay lowlands are unprotected peatlands, except for three proposed IPCAs in northern Manitoba (

Figure 6). Specifically, the Kitaskeenan Kaweekanawaynichikatek IPCA proposed by Fox Lake Cree Nation, Shamattawa First Nation, Tataskweyak Cree Nation, War Lake First Nation, and York Factory First Nation aims to protect ecologically important peatlands in northern Manitoba’s Hudson Bay lowland. These proposed IPCAs in Manitoba do not cover lands with dense vegetation (high NDVI areas) and peatlands in the Island Lake region. An IPCA proposal by Anisininew Okimawin was presented to protect ecologically important areas in the Island Lake region in northeastern Manitoba. However, the Anisininew proposed IPCA was declined (

Figure 6) due to Canada’s mining interests in the region [

85]. There may be many other proposed IPCA areas declined by Canada, including peatlands, due to mining and other development interests.

5. Conclusions

To achieve the 30 by 30 GBF targets, Canada needs to protect further areas, which will require working with Indigenous Peoples. This requires protecting 30% (3 million sq km) of land and freshwater and 30% (1.72 million sq km) of sea and coastal ecosystems as PCAs in total. As of early 2025, Canada protects 13.7% (1.37 million sq km) of its land and freshwater, along with 14.7% (0.84 million sq km) of marine PCAs [

19]. Canada needs to protect an additional 16% (1.6 million sq km) of land and freshwater, and 15% (0.88 million sq km) of sea and coastal areas, by 2030, while recognizing the Indigenous rights proclaimed by UNDRIP. With the 62 proposed IPCAs and the protection of at least half of the more than 30% of peatlands in Canada, the land and water goal of the 30 by 30 GBF target would be met. Further, First Nations in the Island Lake region and the Hudson Bay Lowlands have a keen interest in protecting their ancestral lands and peatlands through IPCAs. As the Hudson Bay Lowlands area’s further protection could extend into the sea, this would contribute to reaching the 30% marine PCAs.

The IPCAs constitute respect for Indigenous rights to land, water, and the ocean [

86]. Researchers advocating for IPCAs oppose the colonial regulation and control of PCAs [

87]. Conservation in IPCAs applies Indigenous knowledge, protocols, and laws with Western knowledge through two-eyed seeing, which emphasizes the strength of both Indigenous and Western knowledge systems for land protection and restoration [

88]. Indigenous-governed IPCAs embrace Indigenous law, protocols, and ceremonies, fostering ecological integrity and high biodiversity for area-based conservation. The legal recognition of Indigenous Peoples governed IPCAs in Canada would facilitate the 30 by 30 GBF targets [

89] to meet the goal of being Indigenous-led, a long-term conservation commitment, and an elevation of Indigenous rights as recommended by the Indigenous Circle of Experts.

Whether historic, numbered, or modern treaties, self-determination will allow Indigenous Peoples to govern land according to their law and protocols in Canada [

90]. The IPCAs provide an innovative pathway for Canada’s reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples in Canada [

10,

29,

30,

87,

88,

91] can facilitate reconciliation of Indigenous Peoples with their land in Canada [

29] with the following two preconditions. First, the Canadian law enables the return of governance of IPCAs to the respective Indigenous Nations through fast-tracking modern treaties [

29,

50,

91,

92] or other mechanisms as deemed necessary by Indigenous governments. Second, Canada ought to clarify that the land and water designated to achieve the 30 by 30 GBF target and IPCAs recognize Indigenous rights, which transcend sections 91(24) and 92(5) of the Constitution Acts, 1867-1982, to recognize Indigenous rights. Meeting the GBF’s requirement of respecting Indigenous rights necessitates Indigenous self-determination and self-government over ancestral lands and water in Canada [

93]. Reconciliation through IPCAs can face challenges from settlers and governments due to Canada’s existing resource extraction priority.

Competing interests for mineral and resource rights remain a barrier to the 30 by 30 GBF targets and IPCAs. Canada’s prioritization of mineral extraction over other land uses poses a barrier to IPCAs. Mining of greenstone belts across Canada significantly threatens many pristine areas and traditional lands, including peatlands, that Indigenous Peoples have protected for generations. Buffered analysis predicts that mining these belts could disrupt approximately one-quarter of Canada’s land and freshwater (3.8 million sq km), with 40%-50% (0.9-1.13 million sq km) overlapping with existing PCAs. Mining interests and legal systems, with the free entry system [

94], complicate area-based conservation in Canada through IPCAs [

22,

83]. The Building Canada Act prioritizes the development of critical minerals. To colonial governments, mining is the first and best use of lands where mining law prevails over Indigenous land claims and IPCA proposals, as occurred at Island Lake in Manitoba [

95]. Being surrounded by greenstone belts, the IPCA proposal of the Anisininew Nations in Island Lake, Manitoba, was rejected in 2022, although its proposed areas avoided existing claims and greenstone belts. With the need for IPCA areas that protect peatlands and critical habitat, this IPCA and others should be revisited. Protecting critical lands and water bodies, such as peatlands, from extractive industries, including mining, is crucial for biodiversity conservation and the recognition of Indigenous rights.

This paper’s strategic analysis of key PCA factors in Canada uniquely considers Indigenous rights. The recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and Indigenous-governed PCAs implications for other settler states globally in meeting the GBF’s 30 by 30 target. Although this paper’s examination of land uses highlights mining interests, other industries such as forestry and lumber, oil, hydropower, and roads also impact PCAs. While other factors are significant for biodiversity conservation and future research, they are beyond the scope of this paper.

6. Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Stewart Hill for his input that contributed to the analysis. We also appreciate Dr. Myrle Ballard, Dr. Kyle Bobiwash, Dr. Marleny Bonnycastle, Land’s two anonymous reviewers, and the academic editor for their feedback.

We thank Parinaz Joneidi Shariat Zadeh for helping design Figure 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T and S.T.; methodology, KT.; software, K.T.; validation, K.T. and S.T.; formal analysis, K.T.; investigation, K.T.; resources, S.T.; data curation, K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T. and KT; visualization, K.T.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACS Accelerate grant number IT24601 and the SSHRC partnership grant number 895-2017-1014 REF 47534—the Mino Bimaadiziwin partnership.

Data Availability Statement

Canada’s protected and conserved areas database, northern peatlands, and provincial boundaries are publicly available. The mining claims and greenstone belts data shared publicly in Esri’s ArcGIS Online system used in this research are also publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WWF 2024 Living Planet Report. Available online: https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/2024-living-planet-report (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- IPBES Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Zenodo, 2019.

- Barnosky, A.D.; Matzke, N.; Tomiya, S.; Wogan, G.O.U.; Swartz, B.; Quental, T.B.; Marshall, C.; McGuire, J.L.; Lindsey, E.L.; Maguire, K.C.; et al. Has the Earth’s Sixth Mass Extinction Already Arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Global Biodiversity Outlook 3—Executive Summary; Montréal, 2010.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Global Biodiversity Outlook 5—Summary for Policy Makers; Montréal, 2020.

- Convention on Biological Diversity Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity: 15/4. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework 2022.

- Protected Planet Discover the World’s Protected and Conserved Areas. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Protected Planet Report 2024; 2024.

- Watson, J.E.M.; Venter, O.; Lee, J.; Jones, K.R.; Robinson, J.G.; Possingham, H.P.; Allan, J.R. Protect the Last of the Wild. Nature 2018, 563, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuy, N.; Staley, D.; Alook, S.; Parlee, B.; Thomson, A.; Littlechild, D.B.; Munson, M.; Didzena, F. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs): Canada’s New Path Forward for Biological and Cultural Conservation and Indigenous Well-Being. FACETS 2023, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, S.T.; Burgess, N.D.; Fa, J.E.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C.J.; Watson, J.E.M.; Zander, K.K.; Austin, B.; Brondizio, E.S.; et al. A Spatial Overview of the Global Importance of Indigenous Lands for Conservation. Nat Sustain 2018, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Fa, J.E.; Brockington, D.; Brondízio, E.S.; Cariño, J.; Corbera, E.; Farhan Ferrari, M.; Kobei, D.; v, P.; Márquez, G.Y.H.; et al. No Basis for Claim That 80% of Biodiversity Is Found in Indigenous Territories. Nature 2024, 633, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauli-Corpuz, V.; Alcorn, J.; Molnar, A.; Healy, C.; Barrow, E. Cornered by PAs: Adopting Rights-Based Approaches to Enable Cost-Effective Conservation and Climate Action. World Dev 2020, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzyreva, M.; Jang, N.; Qi, J.; Terton, A.; Saleh, T. Manitoba’s Hudson Bay Lowlands: Ecosystem Goods and Services Valuation; Winnipeg, 2025.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canada’s 2030 Nature Strategy: Halting and Reversing Biodiversity Loss in Canada; Environment and Climate Change Canada = Environnement et changement climatique Canada, 2024.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015.

- United Nations United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2008.

- An Act Respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; Canada, 2021; p. 22.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database; 2023.

- Antonelli, A. Five Essentials for Area-Based Biodiversity Protection. Nat Ecol Evol 2023, 7, 630–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Cazalis, V.; Dudley, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stolton, S.; Visconti, P.; Woodley, S.; Kingston, N.; Lewis, E.; et al. Area-Based Conservation in the Twenty-First Century. Nature 2020, 586, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.K. The Promise and Peril of Canada’s Approach to Indigenous Protected Areas. The Narwhal 2022.

- Cyca, M. The Future of Conservation in Canada Depends on Indigenous Protected Areas. So What Are They? The Narwhal 2023.

- Gurney, G.G.; Adams, V.M.; Álvarez-Romero, J.G.; Claudet, J. Area-Based Conservation: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead. One Earth 2023, 6, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Convention on Biological Diversity: Text and Annexes; Montreal, 2011.

- Convention on Biological Diversity Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at Its Seventh Meeting (UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/VII/30); 2004.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Targets; 2010.

- Rutgers, J.-S. What an Effort to Preserve Cree Homelands in Northern Manitoba Means to the People behind It. The Narwhal 2024.

- Indigenous Circle of Experts’ Report and Recommendation We Rise Together: Achieving Pathway to Canada Target 1 through the Creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the Spirit and Practice of Reconciliation; 2018.

- Moola, F.; Roth, R. Moving beyond Colonial Conservation Models: Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas Offer Hope for Biodiversity and Advancing Reconciliation in the Canadian Boreal Forest1. Environmental Reviews 2018, 27, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiaiake, A. It’s All about the Land: Collected Talks and Interviews on Indigenous Resurgence; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak, S.; King, H. Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper; 2019.

- Kwasniak, A.J. Sources of Jurisdiction and Control. In Public Lands and Resources Law in Canada; Hughes, E.L., Kwasniak, A.J., Lucas, A.R., Eds.; IrwinLaw, 2016; pp. 53–88.

- The Constitution Act The Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982 1982.

- Cox, S. “It Is so Beautiful”: Rare Inland Rainforest in B.C. Declared Indigenous Protected Area. The Narwhal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Seal River Watershed Alliance Seal River Watershed Indigenous Protected Area Initiative 2023.

- Wall, J.; Moola, F.; Lukawiecki, J.; Roth, R. Indigenous-Led Conservation Improves Outcomes in Protected Areas. Nature Reviews Biodiversity 2025, 1, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada’s Sixth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity; 2018.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canadian Protected Conserved Areas Database; 2023.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Canada Target 1 Challenges. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/nature-legacy/canada-target-one-challenge.html#events (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- EsriCanadaContent Provinces and Territories of Canada 2024.

- Natural Resources Canada Critical Minerals Advanced Projects, Mines and Processing Facilities in Canada. Available online: https://osdp-psdo.canada.ca/dp/en/search/metadata/NRCAN-FGP-1-22b2db8a-dc12-47f2-9737-99d3da921751 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Hugelius, G.; Loisel, J.; Chadburn, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.; MacDonald, G.; Marushchak, M.; Olefeldt, D.; Packalen, M.; Siewert, M.B.; et al. Maps of Northern Peatland Extent, Depth, Carbon Storage and Nitrogen Storage [Dataset]. Available online: https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.7m0cfxprn#citations (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Hugelius, G.; Loisel, J.; Chadburn, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.; MacDonald, G.; Marushchak, M.; Olefeldt, D.; Packalen, M.; Siewert, M.B.; et al. Large Stocks of Peatland Carbon and Nitrogen Are Vulnerable to Permafrost Thaw. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 20438–20446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, K.; Laforest, M.; Banning, C.; Thompson, S. “Where the Moose Were”: Fort William First Nation’s Ancestral Land, Two–Eyed Seeing, and Industrial Impacts. Land 2024, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Werner, T.T. Global Mining Footprint Mapped from High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. Commun Earth Environ 2023, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonter, L.J.; Dade, M.C.; Watson, J.E.M.; Valenta, R.K. Renewable Energy Production Will Exacerbate Mining Threats to Biodiversity. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environment and Climate Change 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets for Canada; 2016.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada Towards a 2030 Biodiversity Strategy for Canada: Halting and Reversing Nature Loss 2023.

- Kacer, V.; Gansworth, L.; Innes, L.; Cormier, K.L.; Scarfone, K.; Green, M. A Review of Crown Legislation for Protected and Conserved Areas: A Guide for Indigenous Leadership; 2023.

- Environmental Goals and Climate Change Reduction Act; NovaScotia,Canada, 2021.

- Blacksmith, C.; Thapa, K.; Stormhunter, T. Indian Act Philanthropy: Why Are Community Foundations Missing from Native Communities in Manitoba, Canada? Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy 1969.

- Yellowhead Institute Cash Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper; 2021.

- The Crown Lands Act; Manitoba Governmnt, 1987; p. 42.

- Crown Lands Act; NovaScotia,Canada, 1989.

- Environment and Climate Change Canada 2023 Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database (CPCAD) User Manual; 2023.

- Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement among the Tłı̨chǫ and the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Government of Canada; 2003.

- Tłı̨chǫ Government Tłı̨chǫ Wenek’e Tłı̨chǫ Land Use Plan; 2013.

- Nordenskiold Steering Committee Tsâwnjik Chu (Nordenskiold) Habitat Protection Area Management Plan; 2010.

- Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Self-Government Agreement among the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation and the Government of Canada and the Government of the Yukon; 1993.

- Neszo, C. The Fallacy of Reconciliation: Self-Determination, Self-Government, and Modern Treaty Fiscal Taxation Regimes. Thesis, McGill University, 2025.

- Kulchyski; Peter Trail to Tears: Concerning Modern Treaties in Northern Canada. Can J Native Stud 2015, 35, 69.

- Government of Canada General Briefing Note on Canada’s Self-Government and Comprehensive Land Claims Policies and the Status of Negotiations; 2016.

- Wood, S.K. The Mamalilikulla’s Long Journey Home. The Narwhal 2022.

- Williams, C. $375M Indigenous-Led Conservation Deal Just Signed in the Northwest Territories. The Narwhal 2024.

- Simpcw First Nation 2022/2023 Annual Report; 2023.

- Rutgers, J.-S. Devastated by Manitoba Hydro, Five Cree Nations Are Working Together to Conserve Traditional Lands. The Narwhal 2024.

- Youth Advisory Council Kitaskeenan Kaweekanawaynichikatek - Our Land We Want to Protect. Available online: https://janegoodall.ca/our-stories/kitaskeenan-kaweekanawaynichikatek-our-land-we-want-to-protect/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Agreement to Establish Ts’udé Nilįné Tuyeta as a Protected Area between the Fort Good Hope Dene Band and the Yamoga Lands Corporation and the Fort Good Hope Métis Nation Local #54 Land Corporation and the Ayoni Keh Land Corporation and the Behdzi Ahda” First Nation and the Government of Northwest Territories as Represented by the Minister of Environment and Natural Resources (“Northwest Territories”); 2019.

- Agreement Regarding the Establishment of Edéhzhíe between Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as Represented by the Minister of the Environment Who Is Responsible for the Department of the Environment (“Canada”) and Dehcho First Nations; 2018.

- Agreement to Establish Thaidene Nene Indigenous Protected Area, Territorial Protected Area, and Wildlife Conservation Area between Lutsel K’e Dene First Nation and the Government of Northwest Territories as Represented by the Minister of Environment and Natural Resources (“Northwest Territories”); 2019.

- Bogossian, J. Canadian Greenstone Belts. Available online: https://www.geologyforinvestors.com/canadian-greenstone-belts/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

-

UNESCO; Church of England Pensions Board; Greenbank; International Union for Conservation of Nature; World Wide Fund for Nature Extractive Activities in UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Commitments, Risks and Investments Implications; 2025.

- Ezeudu, M.-J. The Unconstitutionality of Canada’s Free Entry Mining Systems and the Ontario Exception. Asper Review of International Business and Trade law 2020, 20, 156–183. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeneke, C.J. Mining Impact and Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Thesis, University of Manitoba, 2023.

- Thapa, K.; Laforest, M.; Banning, C.; Thompson, S. “Where the Moose Were”: Fort William First Nation’s Ancestral Land, Two–Eyed Seeing, and Industrial Impacts. Land (Basel) 2024, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Hill, S.; Salles, A.; Ahmed, T.; Adegun, A.; Nwanko, U. The Northern Corridor, Food Insecurity and the Resource Curse for Indigenous Communities in Canada. SPP Research Paper 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loverin, E. Building Canada Act a “troubling Threat” to Indigenous Rights, Says Amnesty International Canada. CBC News 2025.

- Southee, M.; Richardson, K.; Harris, L.; Ray, J. Northern Peatlands in Canada. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/19d24f59487b46f6a011dba140eddbe7 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- United Nations Environment Programme Global Peatland Hotspot Atlas: The State of the World’s Peatlands in Maps. Visualizing Global Threats and Opportunities for Peatland Conservation, Restoration, and Sustainable Management; Nairobi, 2024.

- Olmsted, P. ; Sushant; Ray, J.; Harris, L. Protecting Northern Peatlands: A Vital Cost-Effective Approach to Curbing Canada’s Climate Impact [Policy Brief], 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeneke, C.; Harper, B.; Thompson, S. Mining versus Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas: Traditional Land Uses of the Anisininew in the Red Sucker Lake First Nation, Manitoba, Canada. Land (Basel) 2024, 13, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trethewey, L. Inside the Fight for the Ring of Fire. Macleans 2024.

- Thompson, S.; Harper, V.; Whiteway, N. Keeping Our Land the Way the Creator Taught Us: Wasagamack First Nation; Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre: Winnipeg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reytar, K.; Veit, P.; Braun, J. von Protecting Biodiversity Hinges on Securing Indigenous and Community Land Rights. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/indigenous-and-local-community-land-rights-protect-biodiversity (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Zurba, M.; Beazley, K.F.; English, E.; Buchmann-Duck, J. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), Aichi Target 11 and Canada’s Pathway to Target 1: Focusing Conservation on Reconciliation. Land (Basel) 2019, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.; Ford, R. ; The Firelight Group Implementation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area Agreements in Canada; Vancouver, 2023.

- The Nature Conservancy and Equilibrium Research Best Practice in Delivering the 30X30 Target: Protected Areas and Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures; 2023.

- Reed, G.; Donovan, J. Region and Country Reports - Canada. In The Indigenous World 2024; Mamo, D., Berger, D.N., Bulanin, N., García-Alix, L., Jensen, M.W., Leth, S., Madsen, E.A., Parellada, A., Rose, G.R., Rosling, F.R., Thorsell, S., Wessendorf, K., Eds.; The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA): Copenhagen, 2024; pp. 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.C.; Neasloss, D.; Bhattacharyya, J.; Ban, N.C. “Borders Don’t Protect Areas, People Do”: Insights from the Development of an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation Territory. FACETS 2020, 5, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.; Beazley, K.F.; Hum, J.; joudry, shalan; Papadopoulos, A. ; Pictou, S.; Rabesca, J.; Young, L.; Zurba, M. “Awakening the Sleeping Giant”: Re-Indigenization Principles for Transforming Biodiversity Conservation in Canada and Beyond. FACETS 2021, 6, 839–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A.; Roth, R.; McGregor, D.; Moola, F.; Nitah, S. Catalysing Transformative Change in Conservation: Lessons Learned From a Decolonial Conservation Partnership. Conservation and Society 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

DavidSuzukiFDN Land Governance: Present; YouTube: Canada, 2021.

- Kuyek, J. Canadian Mining Law and the Impacts on Indigenous Peoples Lands and Resources; 2005.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).