1. Introduction

Intraocular lenses (IOLs) are implanted surgically replacing opacified cataractous lenses. A range of materials are used at present for IOLs, including collamer lenses, hydrophobic acrylic, hydrophilic acrylic, PHEMA copolymer, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), and silicone [

1]. Polymers of exceptional quality, characterized by unique physical and optical properties, have been developed for the manufacture of intraocular lenses (IOLs). These materials adhere to the highest quality standards in the market, meeting the specific requirements of medical applications [

2]. PMMA and Poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) are the dominant materials used currently for cataract treatment. In the last two decades, instances of calcification have been reported for hydrophilic intraocular lenses (IOLs). Consequently, several of these IOLs have been explanted [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The calcification response following intraocular lens (IOL) implantation depends on both the composition of the aqueous humor (AH) and the material used in the fabrication of the IOLs. Reports [

3] of post-operative formation of calcium phosphate deposits on intraocular lenses, attributed the formation of mineral salts to the use of viscoelastic material, specifically hyaluronic acid, during the surgical procedure. However, the mineral deposit, was not adequately and convincingly identified. It has also been reported that silicon-based intraocular lenses (IOLs), are favorable substrates for the development of calcific deposits, the composition of which was identified with physicochemical methods [

5]. It appears that the sulfate and carboxylic functional groups of the viscoelastic materials used in cataract IOL surgery, , play important role promoting the nucleation and subsequent growth of calcium phosphates [

6]. The formation of calcium phosphate on implanted biomaterials is the result of heterogeneous nucleation and subsequent crystal growth of the mineral phase. According to classical nucleation theory, two critical factors come into play: the aqueous humor (AH) being supersaturated with respect to calcium phosphate crystal phases, and the substrate on which heteronuclei form—specifically, on the intraocular lens (IOL) material in our case of interest [

7]. The hydrophilic polymeric substrates provide favorable sites for initiation of HAP growth, in contrast with hydrophobic IOLs, which do not calcify. It may be suggested that there is a correlation between the material composition of IOLs and the formation and further growth of calcium phosphate, potentially impacting vision and posing challenges for replacement [

8,

9]. The most frequently used polymer for the fabrication of hydrophilic IOLs is PHEMA, a hydrophilic polymer, which can absorb significant amounts of water. Hydrogels of this type are extensively used for the fabrication of biomaterials. Recent studies suggested that PHEMA promotes nucleation and growth of hydroxyapatite (Ca

5(PO

4)

3OH, HAP) upon contact with solutions supersaturated with respect to HAP [

10,

11,

12].

Next generation of biomaterials suitable for the fabrication of IOLs, fulfill requirements of biocompatibility, refractive index and prevention of posterior capsular opacification. Copolymers of hydrophobic and hydrophilic polymers are now the dominant materials in the IOL market [

2]. Surface-treated polymers are novel materials, which have found useful applications in microfluidics textiles, electronics, water treatment and energy industries [

13,

14,

15]. Surface modification of polymers by chemical treatment has been used for specific applications. Most of the chemical surface treatment methods, employ wet processes in which polymers are immersed, coated, or sprayed with specific chemical substances, which modify the polymer’s surface properties. Polymers surface modification with graphene and its derivatives, has attracted considerable research interest [

16]. Polymeric biomaterials are processed with graphene oxide (GO) or graphene, for bone scaffolds [

17]. Graphene has been deposited in contact lenses providing protection from radiation [

18]. GO is a 2-D material obtained by oxidation of graphite with strong oxidizing agents [

19]. In contrast to graphene, GO is hydrophilic because of the excess oxygen content and high surface-to-volume ratio [

20]. A significant advantage of GO is that it is amenable to surface modification. The chemical structure of GO renders it appealing for various biomedical applications, including tissue engineering, drug delivery, wound healing, and the development of medical devices [

21]. The oxidized form of graphene, consists of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, featuring carbonyl, carboxyl, hydroxyl, and epoxy groups. The composition of GO allows the formation of stable water dispersions [

22,

23]. While the surface of GO sheets exhibits some defects, the fundamental structure of the material closely resembles that of pure graphene [

24]. The flexibility and hydrophilicity of GO facilitates cell growth and imparts antibacterial and antimicrobial properties. It is important to note that high concentrations of GO can potentially lead to reduced biocompatibility [

25,

26]. However, the presence of functional groups enables GO combination with fully biocompatible, non-toxic polymeric materials.

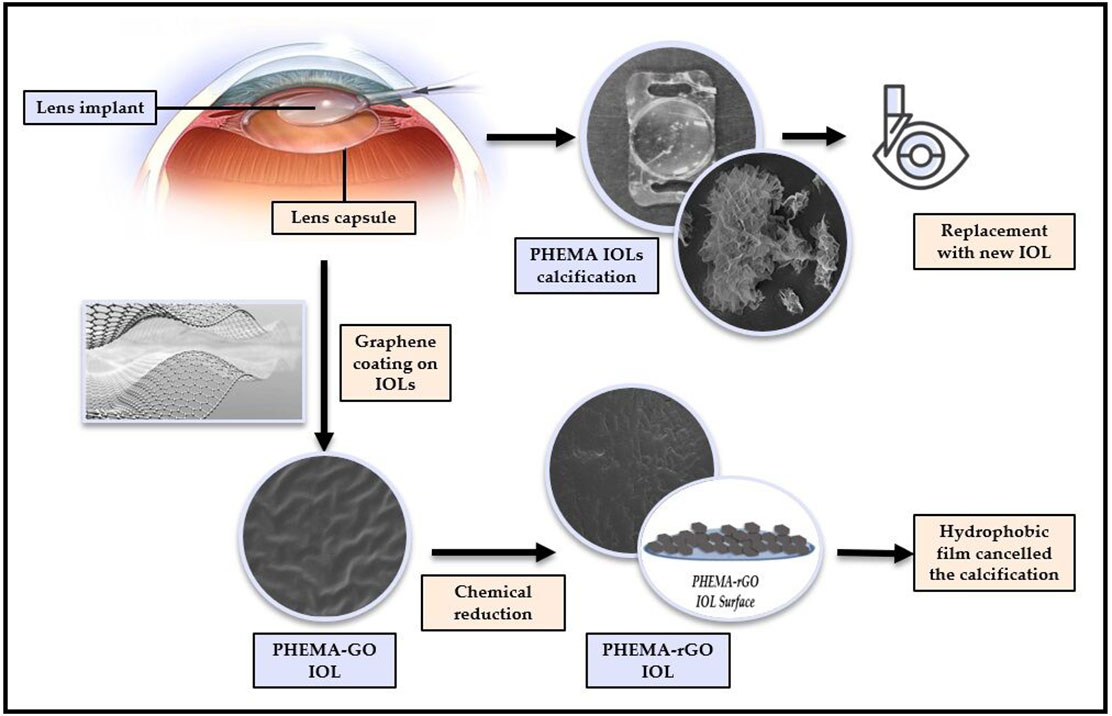

In this study, we have tested the hypothesis of the relationship between surface hydrophilicity and induction of nucleation and growth of HAP on PHEMA which was modified with layers of hydrophilic graphene oxide (GO). Hydrophobic reduced GO (rGO) coatings on PHEMA hydrophilic IOLs were developed by the reduction of GO with phenylhydrazine at room temperature. Both GO and rGO treated IOLs were tested for their ability to induce nucleation and crystal growth of HAP by heterogeneous nucleation upon immersion in stable calcium phosphate supersaturated solutions and by comparison of the respective crystal growth rates.

2. Materials and Methods

All solutions were prepared using triply distilled, deionized water. Stock calcium and phosphate solutions were prepared from crystalline calcium chloride (CaCl

2·2H

2O) and sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH

2PO

4) (Puriss. Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Calcium chloride solutions were standardized with standard EDTA solutions (Merck) using calmagite indicator and by atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS, air-acetylene flame, Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 300, Norwalk, CT, USA). The phosphate stock solutions were standardized with potentiometric titrations with standard sodium hydroxide solutions (Titrisol®, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and by spectrophotometric analysis using the vanadomolybdate method spectrophotometrically (Perkin Elmer lambda 35, Norwalk, CT, USA) [

27]. Sodium chloride stock solutions were prepared from the crystalline solid. The graphene oxide suspensions were prepared from concentrated aqueous suspension (0.4% w/v Graphenea S.A., San Sebastian, Pais Vasco, Spain) with appropriate dilutions with water.

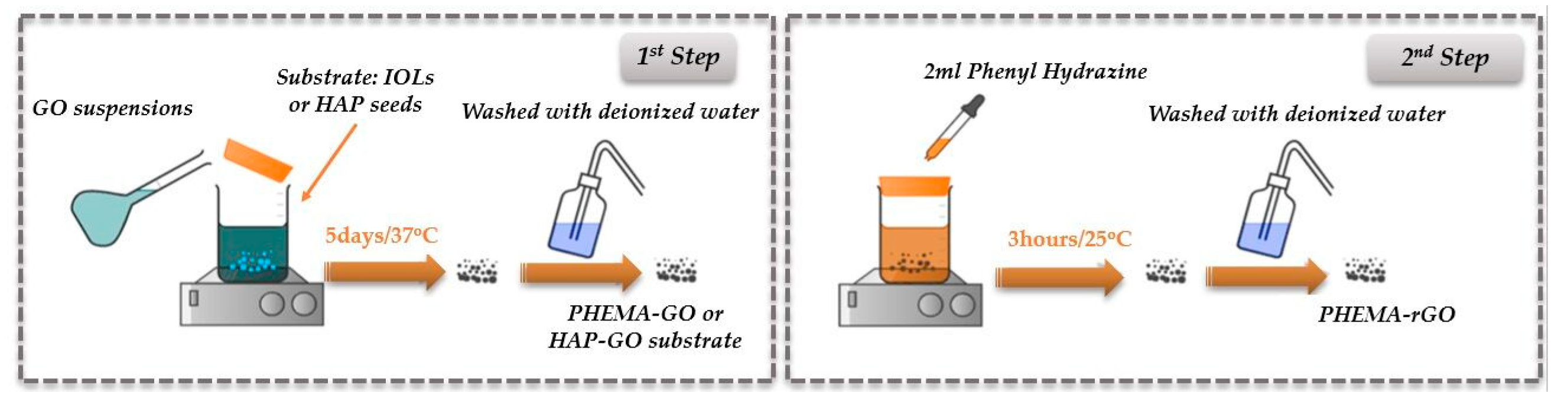

2.1. Treatment of IOLs with Graphene Oxide

Hydrophilic IOLs (consisting mainly of PHEMA with 18% water content) were equilibrated with well mixed GO suspensions to deposit graphene oxide layers on their surface. The IOLs were introduced in 50 mL of GO suspensions in HDPE vials of various concentrations between 1 - 10x10

-4 % w/v, prepared from the stock suspension of 0.4 g/l. The capped vials were rotated end over end to ensure homogeneity of the suspensions in a constant temperature chamber at 37

oC (1

st step,

Figure 1) for a period of five days. The rotation speed was adjusted to 5 rpm, sufficient to keep the suspensions homogeneous. Past the equilibration time, the IOLs were carefully removed from the suspensions and were thoroughly rinsed with at least 500 mL of triply distilled, demineralized water. 6 IOLs were treated in each vial and they were used for the subsequent characterization (Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman spectroscopy (RS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For the calcification tests, three of the treated IOLs were used, with a total geometric surface of 3.72 cm

2. Past the first processing stage, the GO layer deposited on the IOLs was subjected to chemical reduction [

28]. Specifically, GO coated IOL specimens were suspended in a solution of a strong reducing solution of phenylhydrazine, for three hours at 25

oC (2

nd step,

Figure 1). Next, the IOLs were removed carefully with plastic forceps to avoid surface scratches and they were rinsed thoroughly with triply distilled, demineralized water, before use in the mineralization experiments. The reduced IOLs were kept at room temperature. Following chemical reduction, were characterized and tested as the IOL-GO coated specimens.

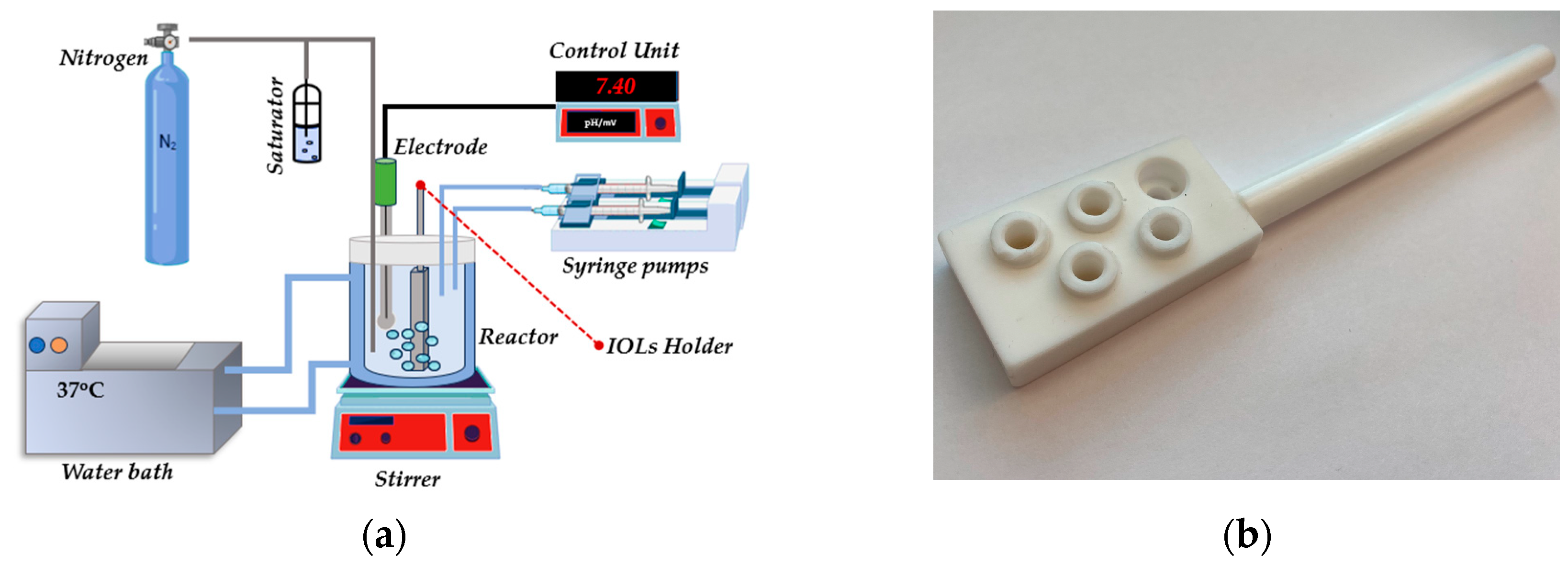

2.2. Mineralization Experiments-Constant Composition Reactor (CCR)

Supersaturated solutions were prepared in a water-jacketed, double-walled borosilicate glass reactor, maintained at a constant temperature of 37.0 ± 0.1 °C by circulating water from a thermostat. Equal volumes (0.100 dm

3 each) of calcium chloride and sodium dihydrogen phosphate solutions were simultaneously transferred in the reactor, volume totaling 0.220 dm

3 under continuous stirring at ca. 200 rpm with a magnetic stirrer and a Teflon-coated stirring bar. The solution's pH was adjusted to 7.40 by adding standard sodium hydroxide solution. pH measurements were conducted using a combination glass ‖Ag |AgCl electrode, s standardized before and after each experiment with NIST standard buffer solutions [

29]. The ionic strength of the supersaturated solutions, was adjusted with NaCl at 0.15 mol·dm

-3 by the addition of the appropriate volume of the respective stock solutions. The final concentrations of total calcium (Ca

t) and total phosphate (P

t) were adjusted to levels ensuring that the driving force for the formation of calcium phosphates simulated that found in the aqueous humor healthy humans [

10,

30]. Before, during, and after adjusting the pH of the supersaturated solutions, an inert atmosphere was maintained by continuously bubbling pure water vapor saturated pure nitrogen gas through the solutions. Once the stability of the supersaturated solutions was confirmed, as suggested by the solution pH stability for at least two hours, hydrophilic IOLs or treated IOLs (3–5) were securely mounted on a special holder, made of TEFLON®, allowing exposure of both the anterior and posterior sides. The mounted IOLs were fully immersed in the supersaturated solutions. The pH of the solutions was continuously monitored and the pH measuring electrode was connected to the controller unit connected through the appropriate interface and software with a computer. A motorized stage, with a stepper motor capable of moving two mechanically coupled, calibrated precision borosilicate glass syringes, delivering volumes as small at 30 μL was controlled by the controller unit. The onset of precipitation was identified by a drop in the solution's pH, due to the proton release accompanying the formation of the solid precipitate. For HAP precipitation, the reaction is shown in Equation (1).

Drop of the solution's pH, approximately equal to the sensitivity limit of the electrode (around 0.005 pH units), prompted the addition of equal volumes of titrant solutions from the two syringes. The composition of the solutions in the syringes (in terms of calcium, phosphorous and hydroxide reactants) was calculated according to the stoichiometry of the precipitating solid Cat:Pt:OHt = 5:3:1 (subscript t stands for total) .The composition of the titrant solutions was calculated as shown in Equations (2) to (5).

Titrant solution A: Calcium chloride solution and sodium chloride represented as:

Titrant solution B: Sodium dihydrogen phosphate and sodium hydroxide as:

where [] denote analytical concentrations of the enclosed species, superscript R denotes the supersaturated solution, TA and TB denote the titrant solutions in the two syringes A and B respectively, m is an arbitrary constant determined by preliminary experiments and n is a constant such that

.

The composition of the titrant solutions A and B was the proper to maintain the activities of the ion species in the supersaturated solutions throughout the precipitation of HAP. From a series of preliminary experiments, the value obtained for .

By monitoring the volume of titrants added as soon as the IOLs were immersed in the supersaturated solutions (time, t = 0), it was possible to precisely measure the induction time (elapsed time from t = 0 until the beginning of titrant addition) and to calculate the rates of precipitation of the salt forming on the introduced substrate. The rates are calculated from the slope of the corresponding volume-time profiles (moles HAP/s). The rates were moreover normalized per unit surface area of the substrate responsible for the formation of the precipitate selectively. The experimental setup used for the investigation of the kinetics of hydrophilic IOL mineralization is illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.3. Characterization of the Solid Substrates and Precipitates

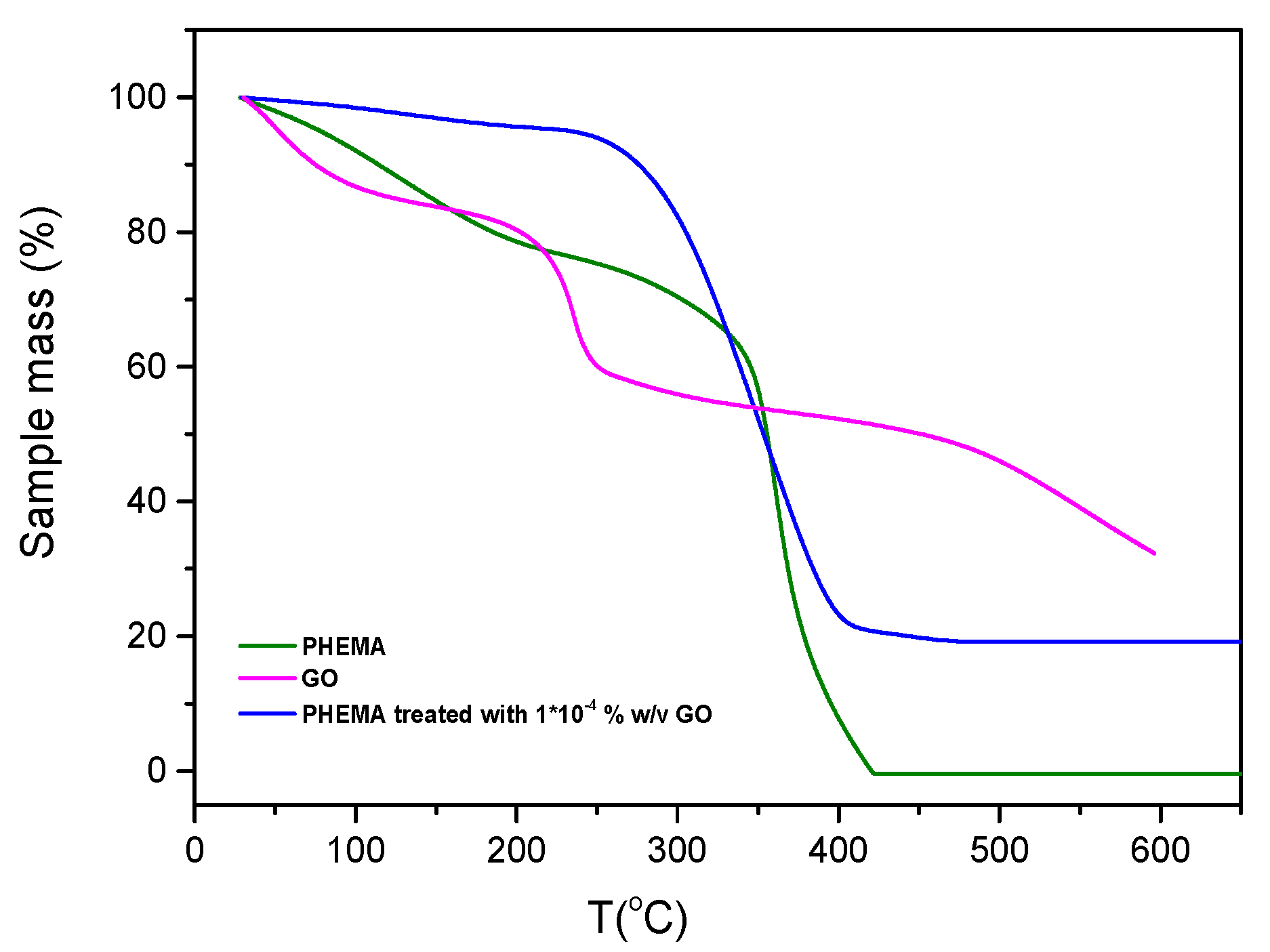

2.3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted with the analyzer TA Q50 (Newcastle, Delaware TA instruments / WATERS) in the temperature range 25 - 700 oC, nitrogen atmosphere and heating rate of 10 oC/min.

2.3.2. Contact Angle Measurements

Contact angle measurement of IOLs before and after treatment was carried out using an optical microscope (x4) and a camera. Photographs were taken for each IOL with or without treatment. The contact angle was measured using ImageJ® software.

2.3.3. UV-VIS Spectroscopy

UV-Vis absorption spectra of the modified IOLs were collected at room temperature using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, Model Lambda 35). The IOLs samples were placed in Teflon holders, specifically designed to fit in quartz cuvettes of 1 cm optical path, allowing UV radiation to reach the exposed specimens.

2.3.4. Raman Spectroscopy

A Raman spectrometer (iRaman Plus BWS465-785H, B&W Tek Inc., Newark, DE, USA) equipped with an optic microscope (B&W Tek Inc., Newark, DE, USA) and a laser with a 785 nm excitation line was used. An Olympus objective lens (20×) was used for focusing onto the IOLs surface. The system was equipped with a high quantum efficiency CCD array detector. The nominal power of the incident laser was 455 mW and 10% of the laser power was used for recording the Raman spectra of IOLs specimens. Each spectrum was recorded in the region of 200–2800 cm−1. Software BwSpec4® (B&W Tek Ink, Newark, DE, USA) used for spectra recording.

2.3.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

The XPS measurements of the samples past the formation GO coatings and their reduction with phenyl hydrazine, were carried out in a UHV chamber with a SPECS LHS-10 hemispherical electron analyzer. An unmonochromatized Al Kα line at 1486.6 eV and an analyzer pass energy of 36 eV giving a full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of 0.9 eV for the Ag 3d5/2 peak were used. The analyzed area was a spot of 3 mm diameter. The XPS peaks were fitted by decomposing each spectrum into individual mixed Gaussian-Lorentzian peaks. For spectra collection and treatment, including fitting, the commercial software SpecsLab Prodigy (Specs GmbH, Berlin) was used.

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) LEO SUPRA with Bruker 145 XS EDX microanalysis unit (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used for the morphological analysis and the chemical microanalyses of the specimens. The specimens were gold sputtered.

2.3.7. Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS)

Samples were withdrawn during mineralization experiments, filtered through membrane filters (0.2 μm Millipore) and the filtrates were acidified and then analyzed for calcium concentration with atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS, Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 300) using air-acetylene mix of gases and the appropriate hollow cathode lamp at 422.7 nm.

Figure 1.

Schematic outline of the preparation of GO and rGO coatings on hydrophilic, PHEMA IOLs.

Figure 1.

Schematic outline of the preparation of GO and rGO coatings on hydrophilic, PHEMA IOLs.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of: (a) the experimental setup for the investigation of mineralization of hydrophilic IOLs and (b) photo of the IOLs mounting system.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of: (a) the experimental setup for the investigation of mineralization of hydrophilic IOLs and (b) photo of the IOLs mounting system.

Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) profiles of IOLs before and after equilibration with GO suspensions and of GO flakes. (-) Hydrophilic IOL (PHEMA), (-) IOL treated with-GO suspension_1x10-4 % w/v, (-) GO. Mass change of the test material (%) as a function of temperature; nitrogen atmosphere, 10 oC/min.

Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) profiles of IOLs before and after equilibration with GO suspensions and of GO flakes. (-) Hydrophilic IOL (PHEMA), (-) IOL treated with-GO suspension_1x10-4 % w/v, (-) GO. Mass change of the test material (%) as a function of temperature; nitrogen atmosphere, 10 oC/min.

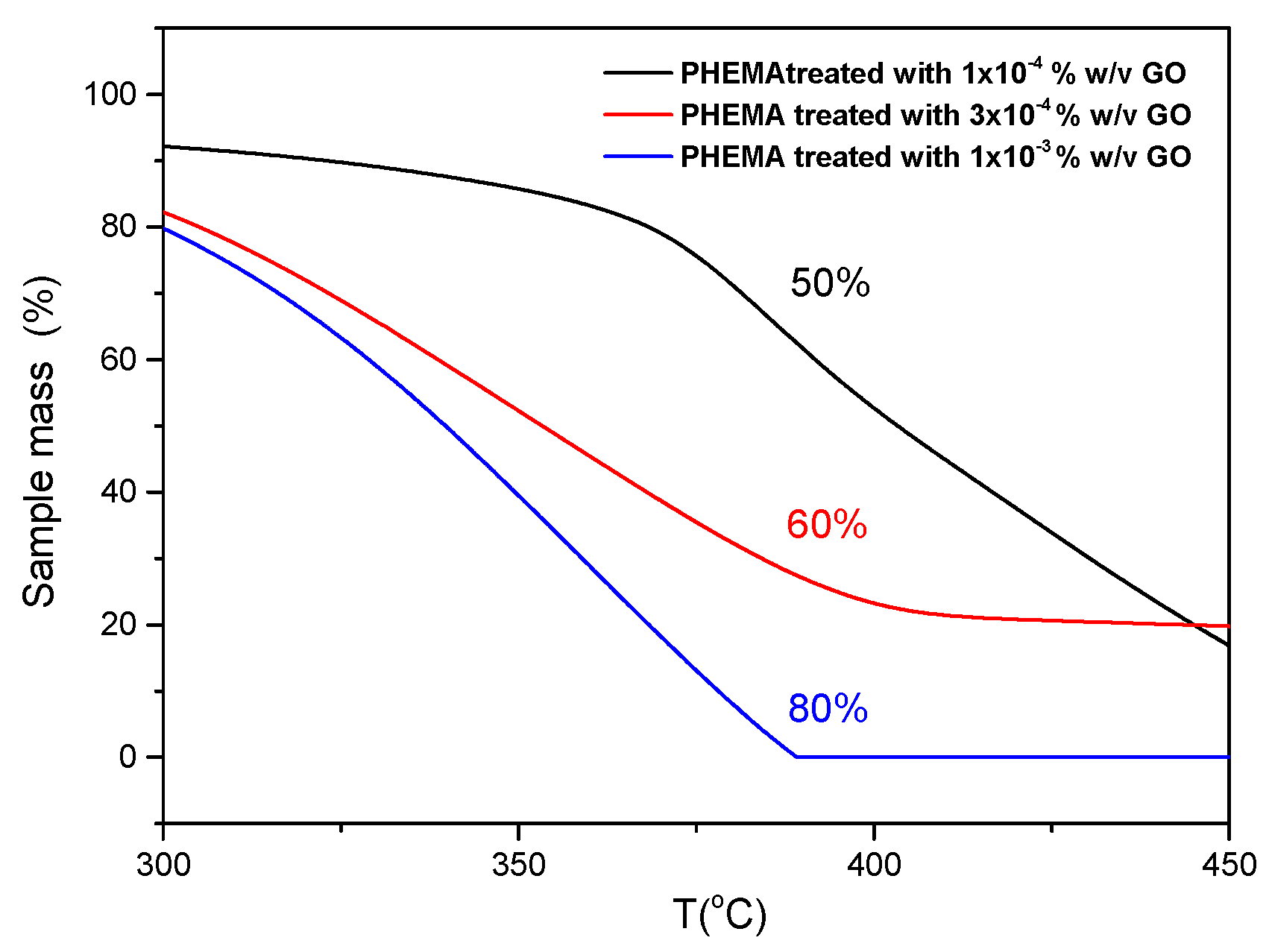

Figure 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of hydrophilic IOLs treated with GO suspensions: (-) 1x10-4 % w/v; (-)3x10-4 % w/v; (-) 1x10-3 % w/v; nitrogen atmosphere; 10 oC/min.

Figure 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of hydrophilic IOLs treated with GO suspensions: (-) 1x10-4 % w/v; (-)3x10-4 % w/v; (-) 1x10-3 % w/v; nitrogen atmosphere; 10 oC/min.

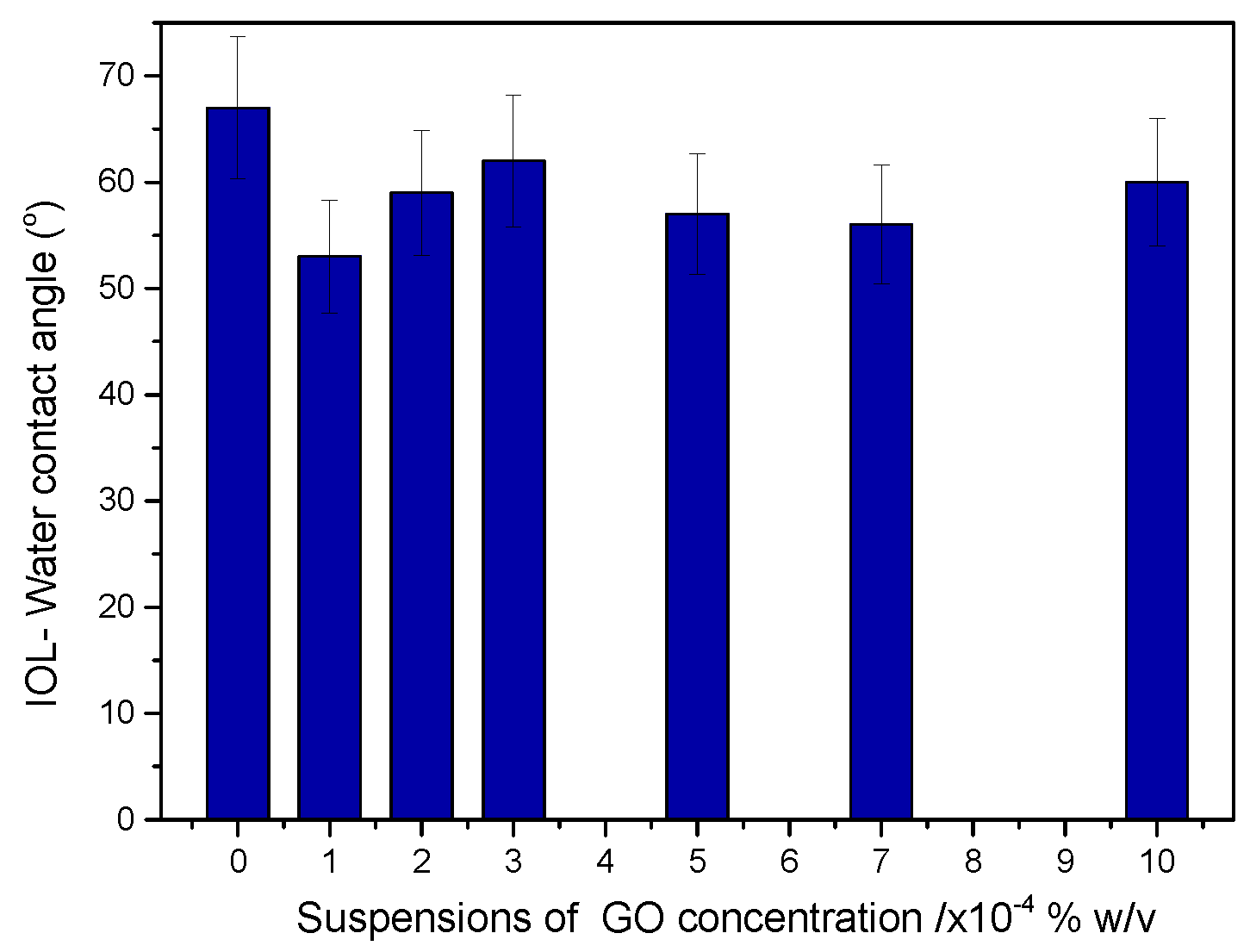

Figure 5.

IOL- water contact angle of IOLs treated with GO suspensions in water with different solid concentrations.

Figure 5.

IOL- water contact angle of IOLs treated with GO suspensions in water with different solid concentrations.

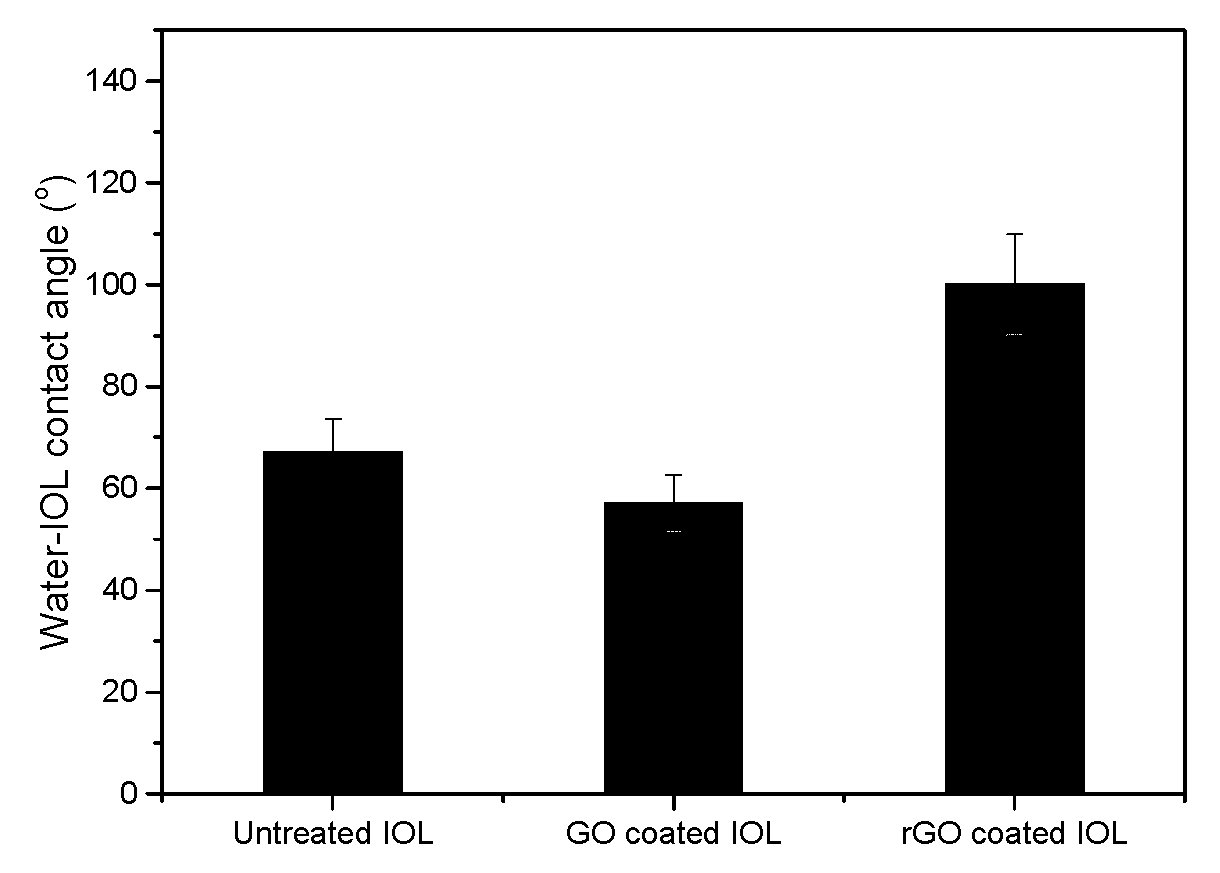

Figure 6.

IOL- water contact angles before and after treatment with GO suspensions (5x10-4 % w/v) and following treatment with phenyl hydrazine which converted GO into rGO.

Figure 6.

IOL- water contact angles before and after treatment with GO suspensions (5x10-4 % w/v) and following treatment with phenyl hydrazine which converted GO into rGO.

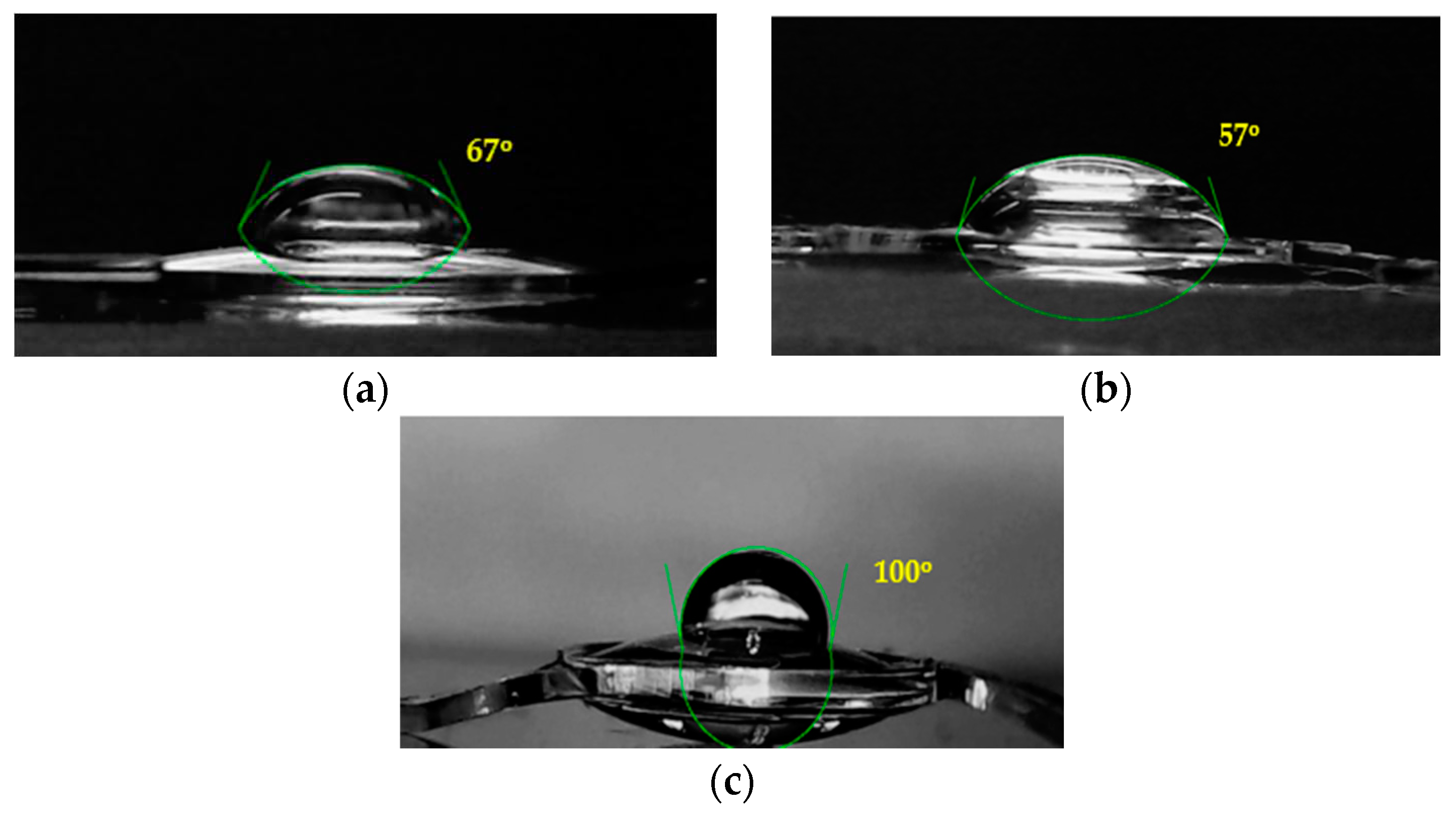

Figure 7.

Water drops on IOLs for the measurement of contact angles: (a) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (b) Hydrophilic IOL following equilibration with GO suspensions (5x10-4 % w/v); (c) Hydrophilic IOL following reduction of the GO layer into rGO.

Figure 7.

Water drops on IOLs for the measurement of contact angles: (a) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (b) Hydrophilic IOL following equilibration with GO suspensions (5x10-4 % w/v); (c) Hydrophilic IOL following reduction of the GO layer into rGO.

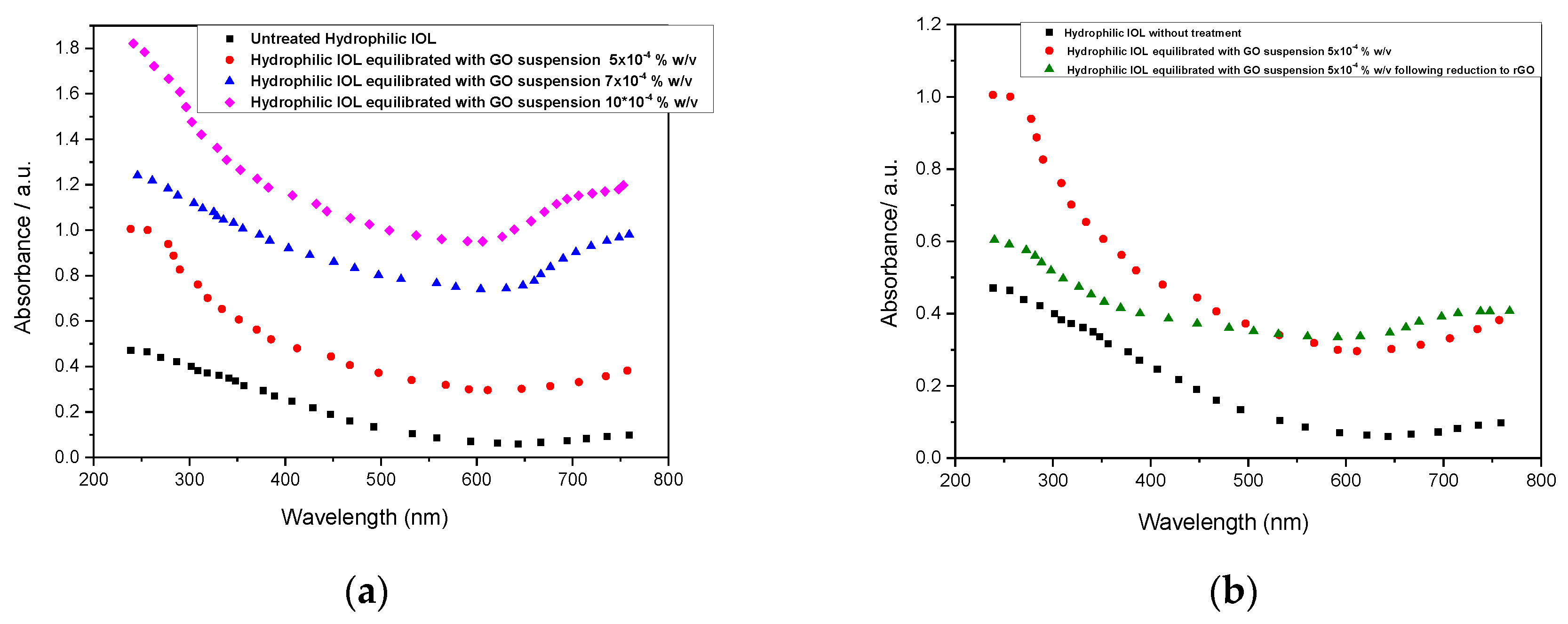

Figure 8.

UV-Vis spectra of IOLSs treated with GO suspensions; (a) (-) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 7x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 1x10-3 % w/v; (b) (-) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v following reduction with phenyl hydrazine in which GO was converted to rGO.

Figure 8.

UV-Vis spectra of IOLSs treated with GO suspensions; (a) (-) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 7x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 1x10-3 % w/v; (b) (-) Untreated hydrophilic IOL; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v; (-) Hydrophilic IOL treated with GO suspension 5x10-4 % w/v following reduction with phenyl hydrazine in which GO was converted to rGO.

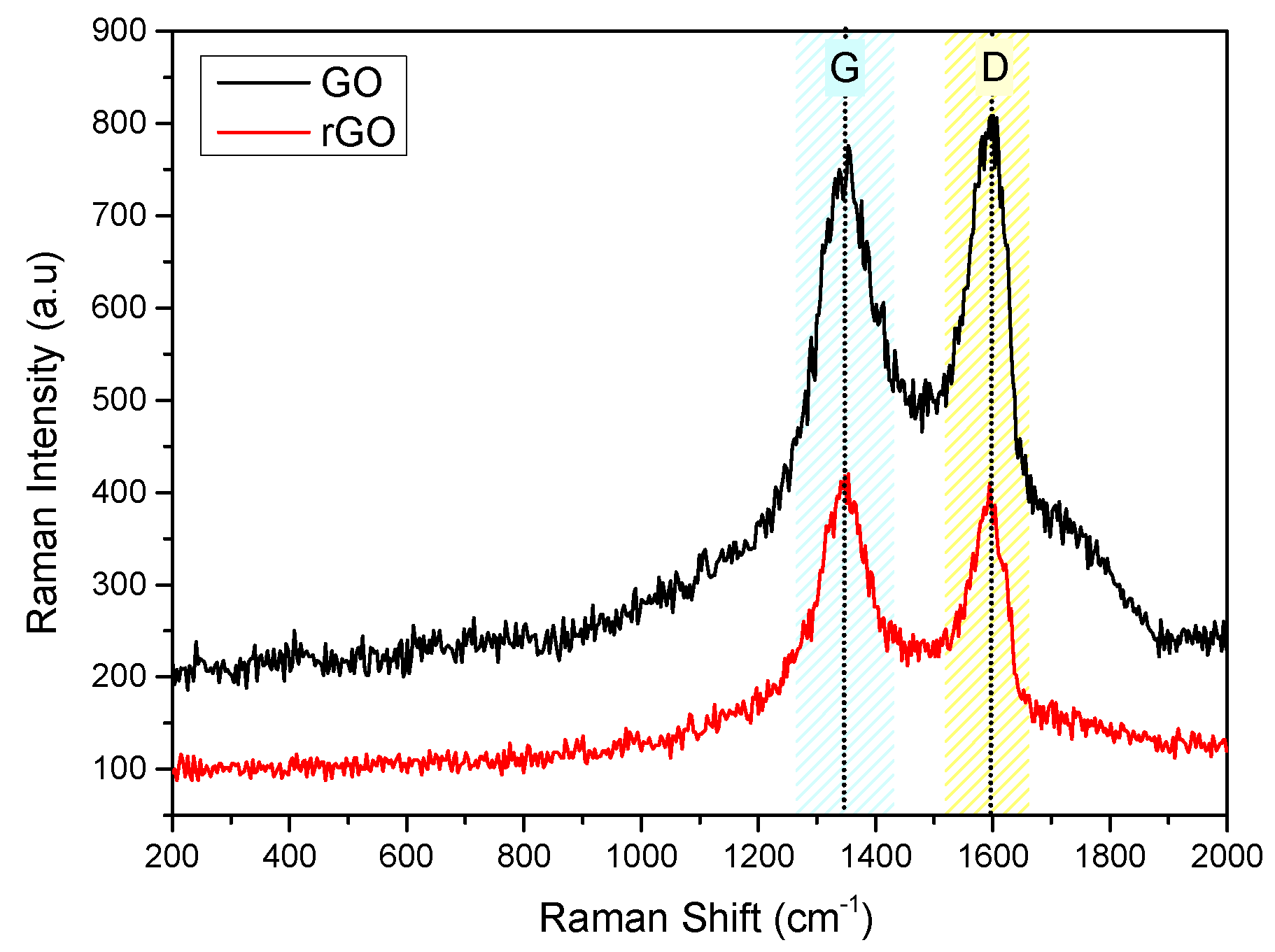

Figure 9.

Raman Spectra of Graphene oxide (GO) and Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) samples.

Figure 9.

Raman Spectra of Graphene oxide (GO) and Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) samples.

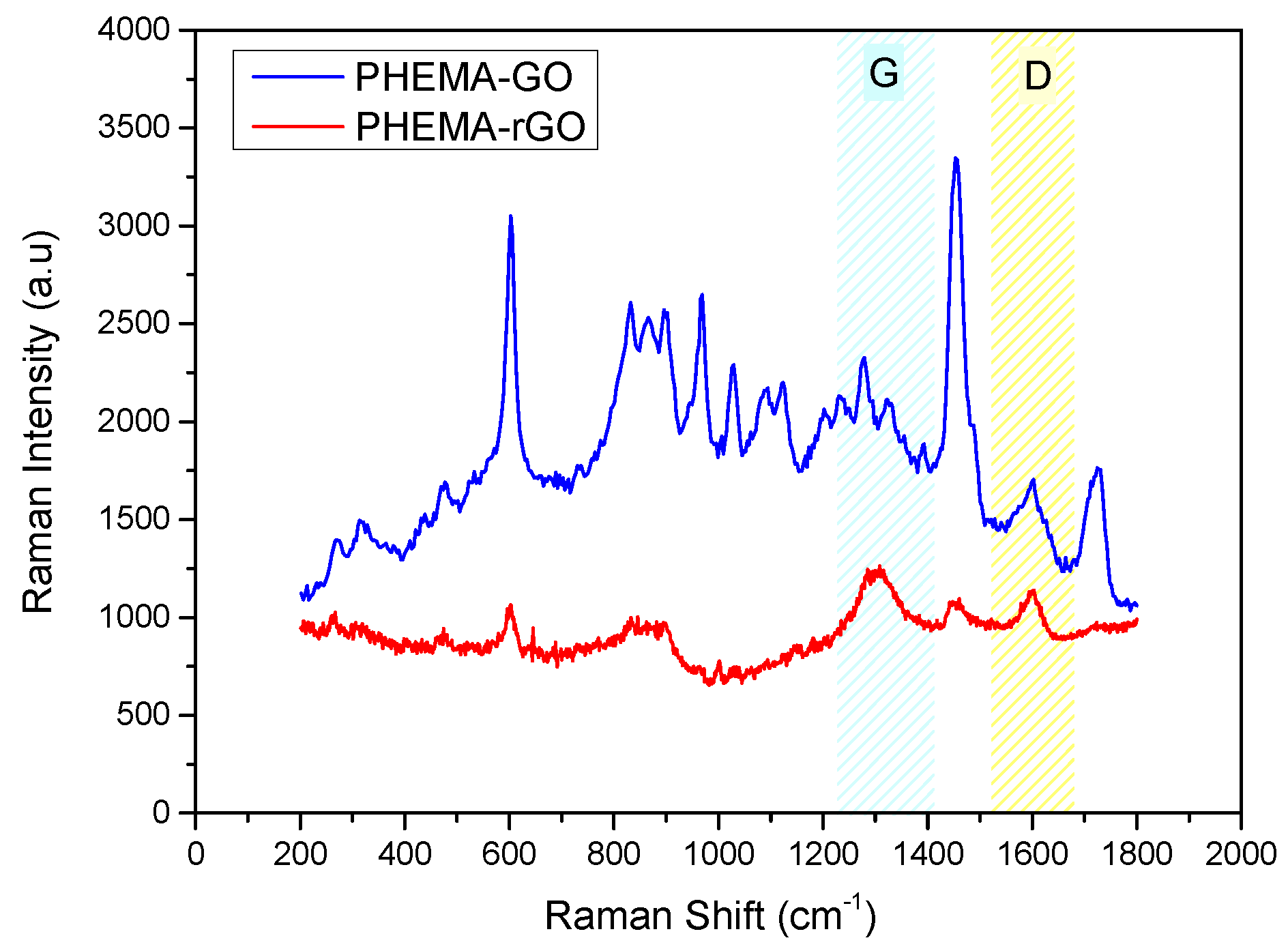

Figure 10.

Raman Spectra of hydrophilic IOLs coated with GO and rGO.

Figure 10.

Raman Spectra of hydrophilic IOLs coated with GO and rGO.

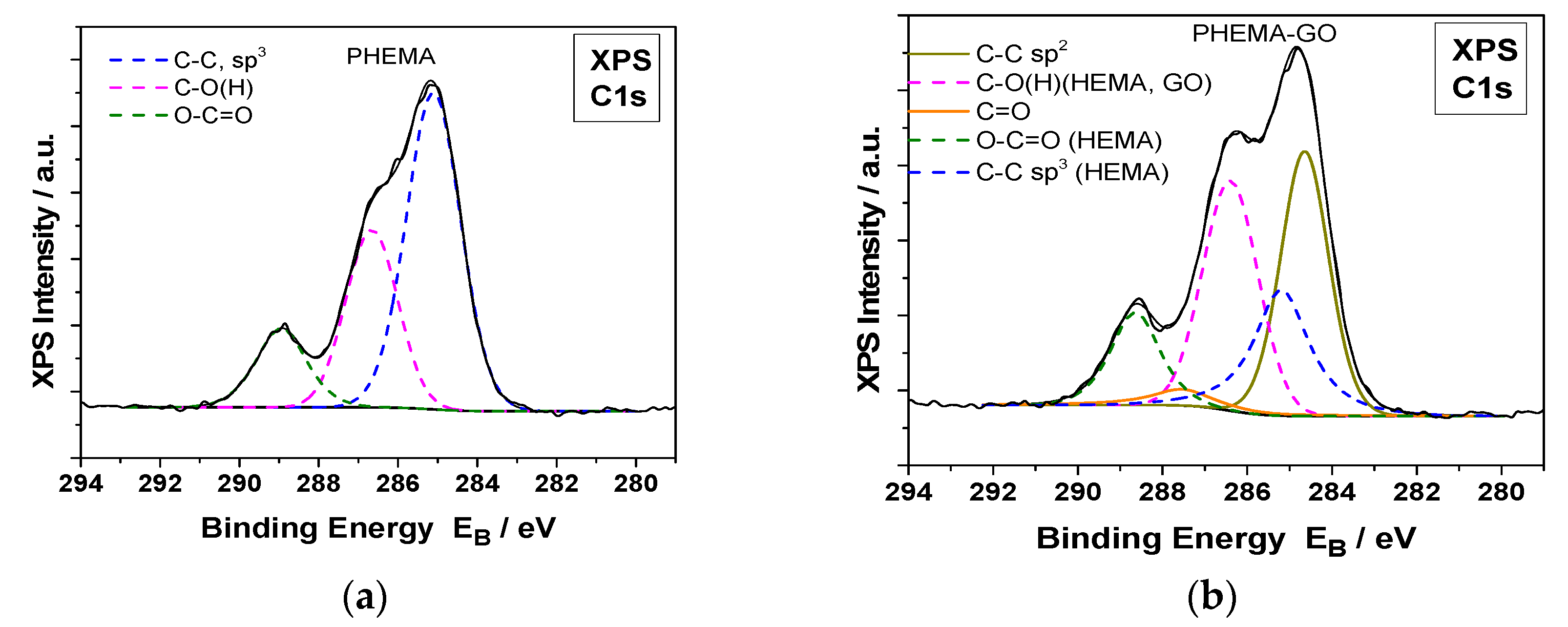

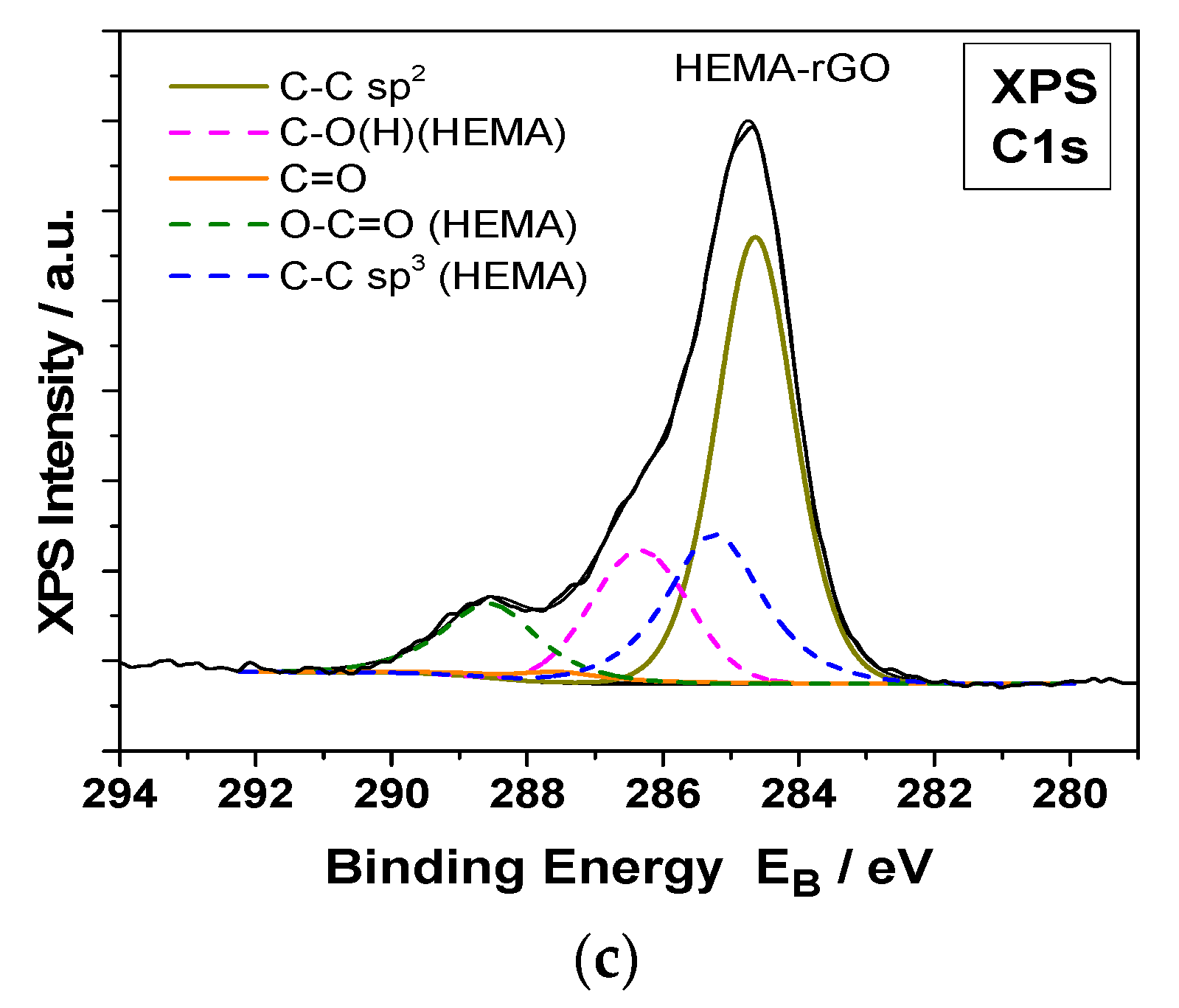

Figure 11.

Deconvoluted C1s XPS spectra of hydrophilic IOLs (PHEMA) after equilibration in GO suspensions (PHEMA-GO) and past reduction with phenyl hydrazine (PHEMA-rGO); (a) PHEMA, (b) GO coated PHEMA hydrophilic IOLs (PHEMA-GO) (c) rGO coated following reduction of the GO layers on the IOLs with phenyl hydrazine (PHEMA-rGO).

Figure 11.

Deconvoluted C1s XPS spectra of hydrophilic IOLs (PHEMA) after equilibration in GO suspensions (PHEMA-GO) and past reduction with phenyl hydrazine (PHEMA-rGO); (a) PHEMA, (b) GO coated PHEMA hydrophilic IOLs (PHEMA-GO) (c) rGO coated following reduction of the GO layers on the IOLs with phenyl hydrazine (PHEMA-rGO).

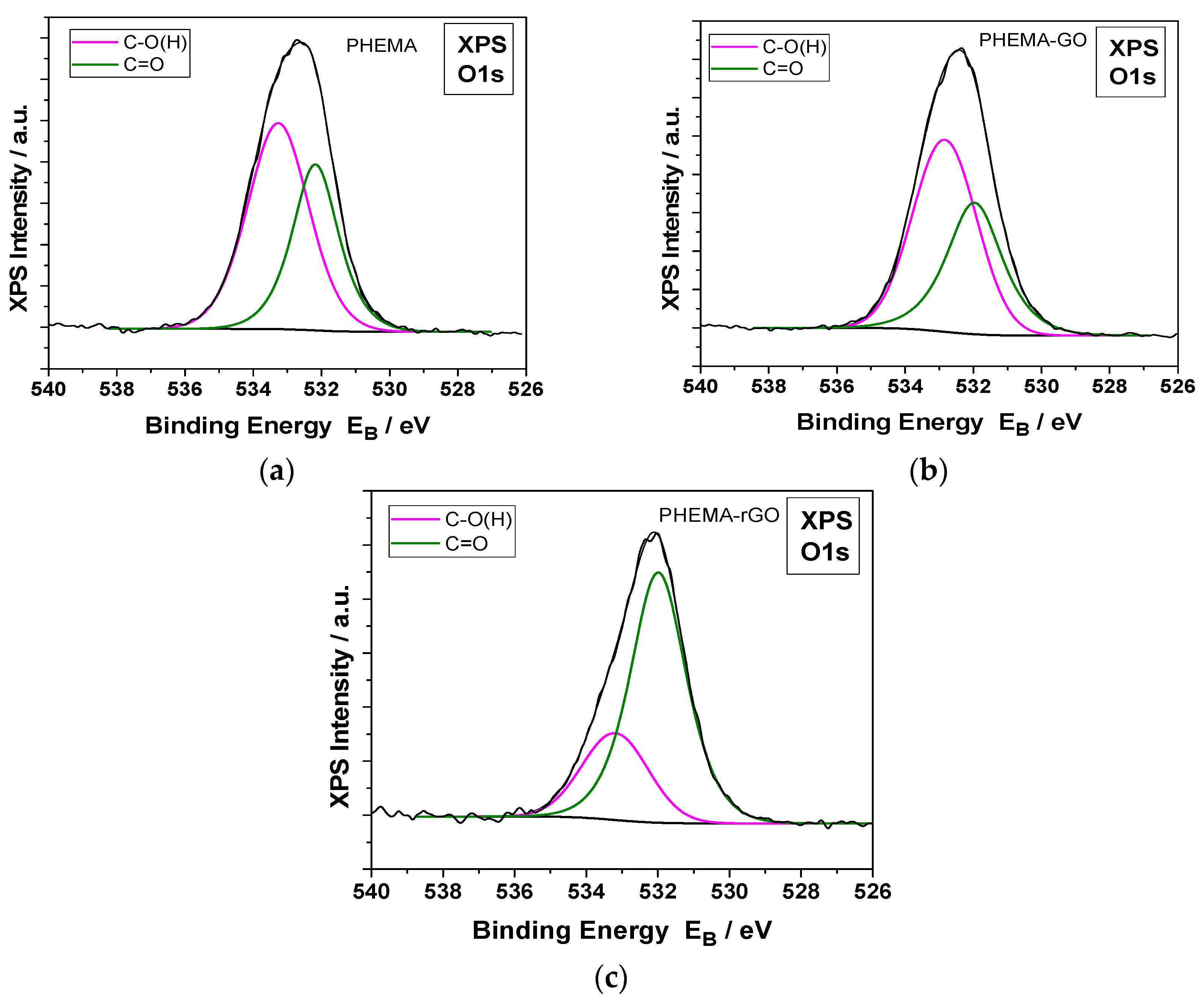

Figure 12.

Deconvoluted O 1s XPS spectra of hydrophilic IOLs past equilibration in GO suspensions and following reduction with phenyl hydrazine; (a) PHEMA, (b) PHEMA -GO and (c) PHEMA-rGO.

Figure 12.

Deconvoluted O 1s XPS spectra of hydrophilic IOLs past equilibration in GO suspensions and following reduction with phenyl hydrazine; (a) PHEMA, (b) PHEMA -GO and (c) PHEMA-rGO.

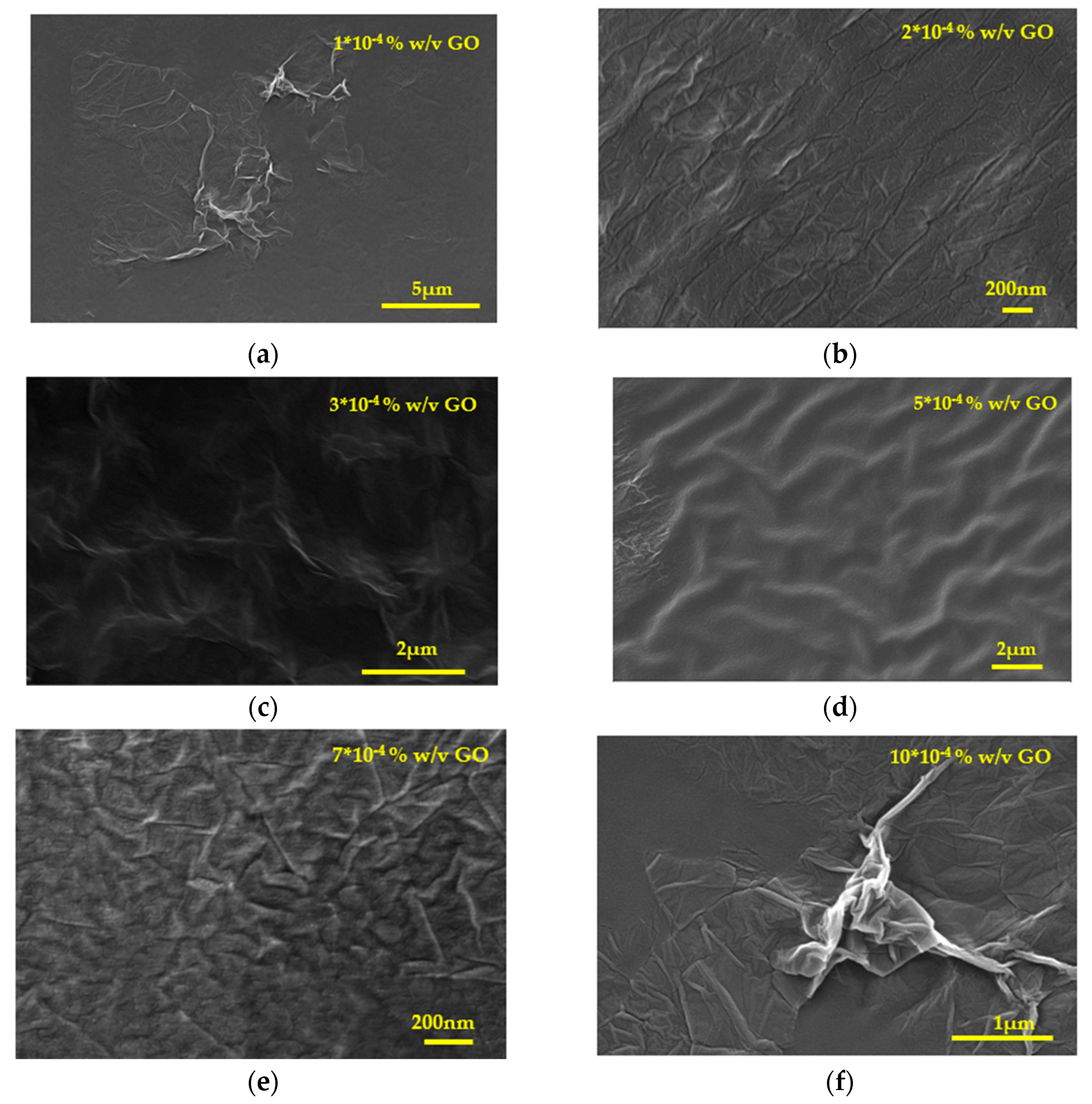

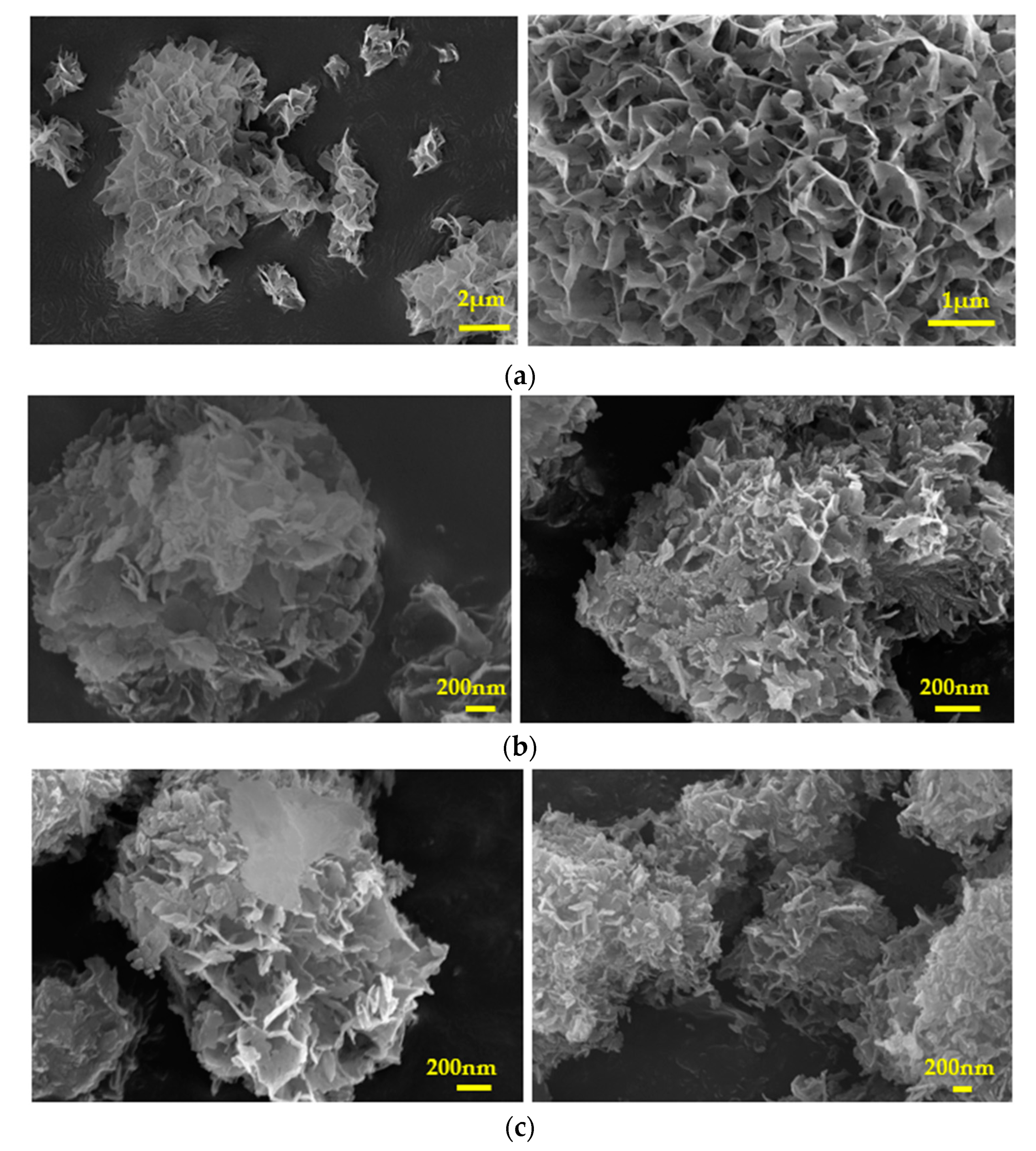

Figure 13.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of IOLs past equilibration with GO suspensions (a)10x10-4 % w/v GO, (b) 2x10-4 % w/v GO, (c) 3x10-4 % w/v, (d) 5x10-4 % w/v GO, (e) 7x10-4 % w/v GO and (f) 10x10-4 % w/v GO.

Figure 13.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of IOLs past equilibration with GO suspensions (a)10x10-4 % w/v GO, (b) 2x10-4 % w/v GO, (c) 3x10-4 % w/v, (d) 5x10-4 % w/v GO, (e) 7x10-4 % w/v GO and (f) 10x10-4 % w/v GO.

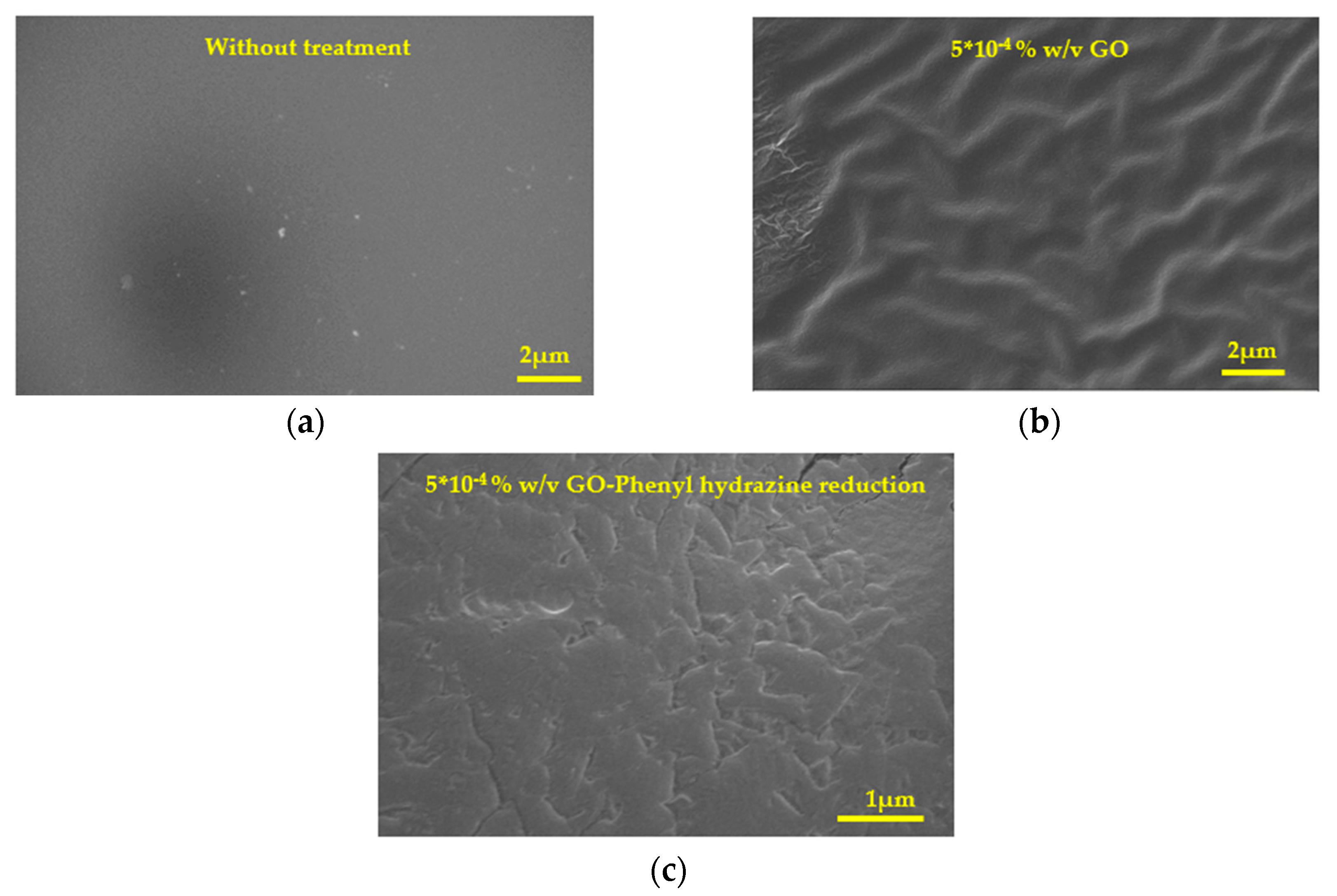

Figure 14.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of hydrophilic IOLs coated with GO past their chemical reduction with phenyl hydrazine (a) Without treatment, (b) Coating developed after equilibration with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension and (c) Coating after chemical reduction of (b).

Figure 14.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of hydrophilic IOLs coated with GO past their chemical reduction with phenyl hydrazine (a) Without treatment, (b) Coating developed after equilibration with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension and (c) Coating after chemical reduction of (b).

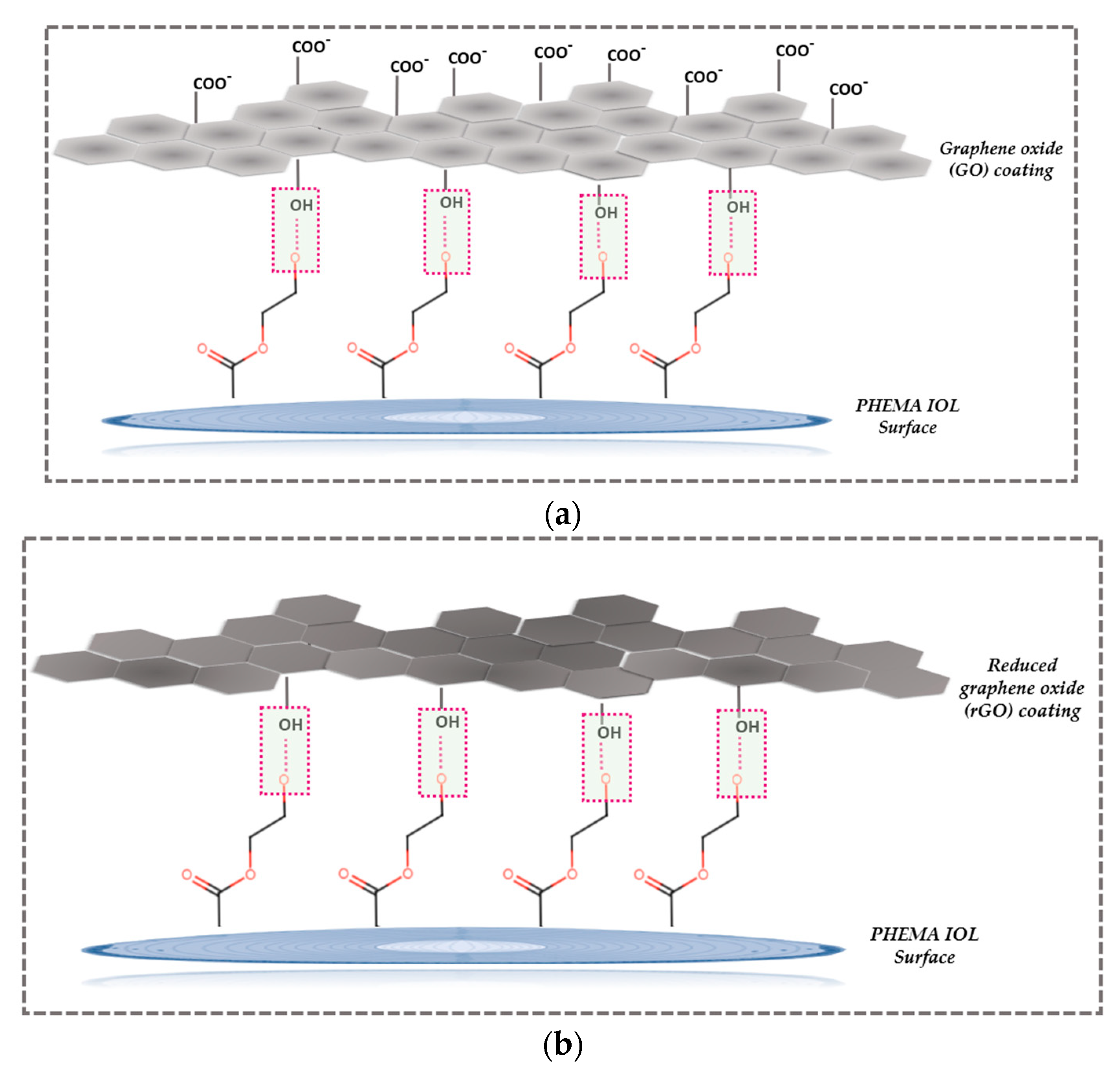

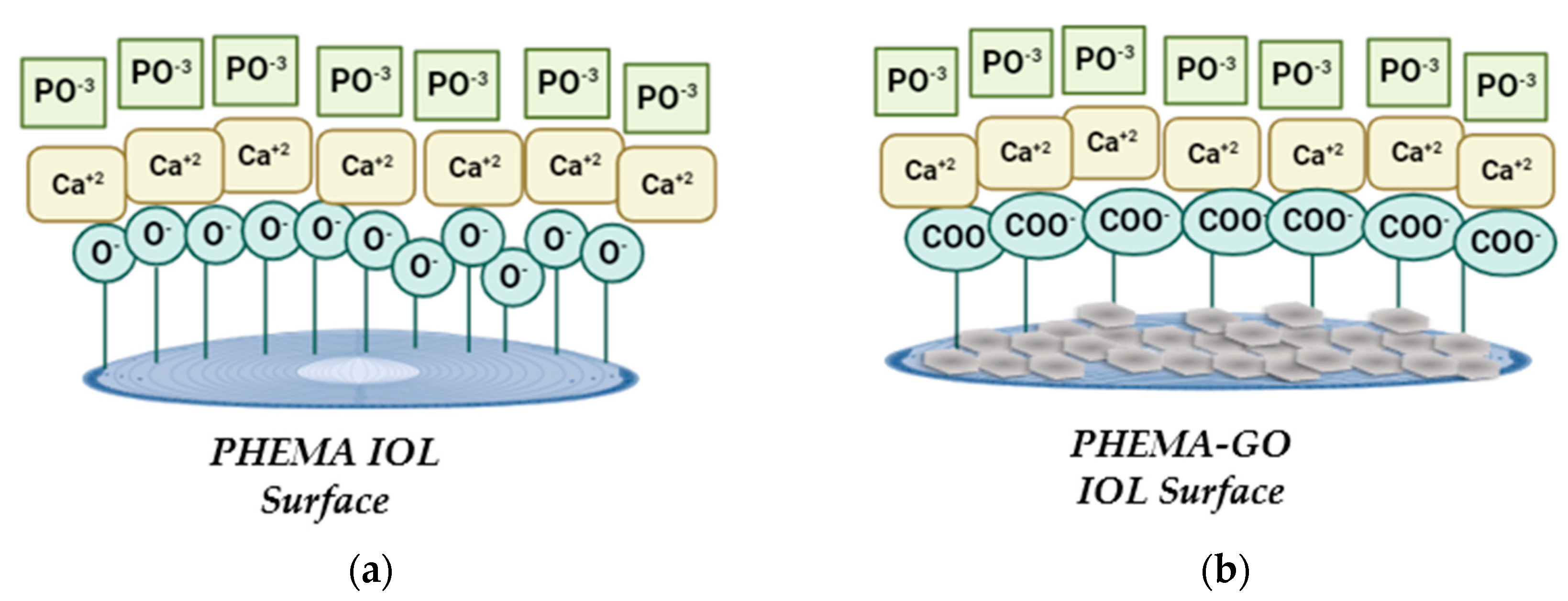

Figure 15.

Illustrations of possible mechanism of PHEMA and GO interaction (a) before and (b) after reduction of the GO coating with phenyl hydrazine.

Figure 15.

Illustrations of possible mechanism of PHEMA and GO interaction (a) before and (b) after reduction of the GO coating with phenyl hydrazine.

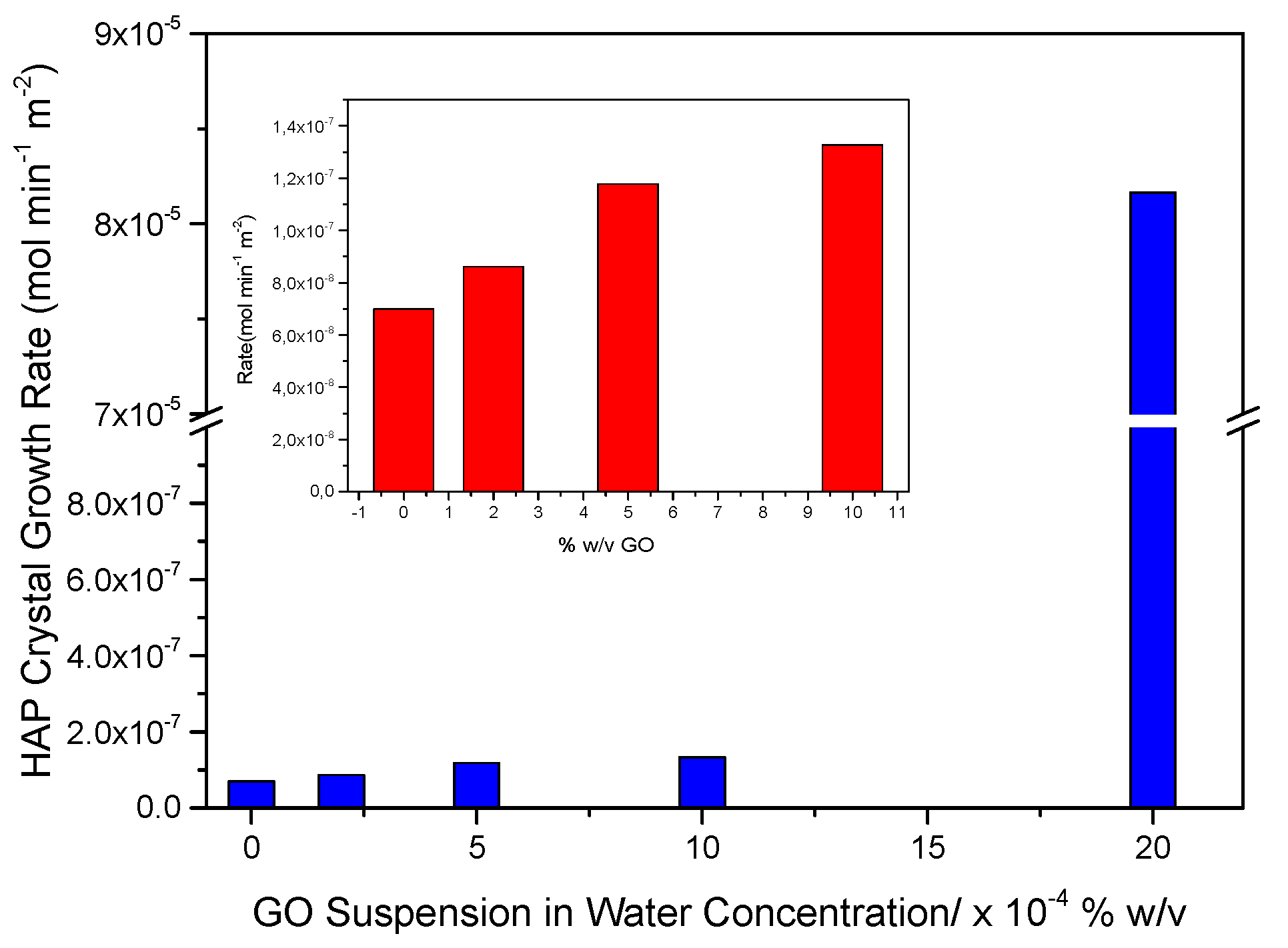

Figure 16.

Rates of HAP crystal growth on HAP crystals equilibrated with GO suspensions in water, as a function of the concentration of the GO suspensions, from supersaturated solutions. Relative solution supersaturation with respect to HAP, σHAP=9.99, pH 7.40, 0.15 M NaCl.

Figure 16.

Rates of HAP crystal growth on HAP crystals equilibrated with GO suspensions in water, as a function of the concentration of the GO suspensions, from supersaturated solutions. Relative solution supersaturation with respect to HAP, σHAP=9.99, pH 7.40, 0.15 M NaCl.

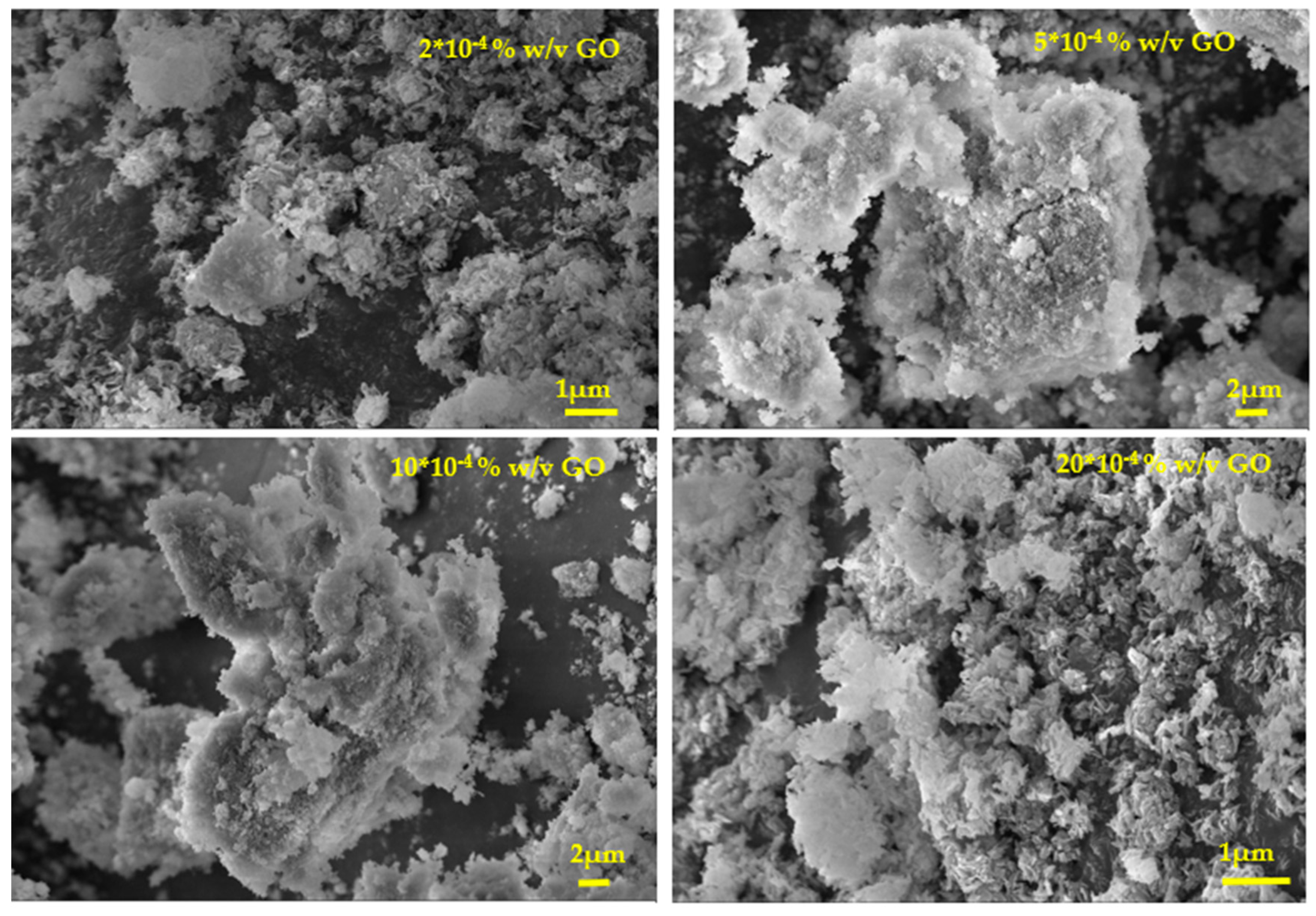

Figure 17.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of HAP crystals grown at constant supersaturation on HAP seed crystals equilibrated with GO suspensions in water of different concentrations as shown on the individual frames; σHAP=9.99, 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M.

Figure 17.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of HAP crystals grown at constant supersaturation on HAP seed crystals equilibrated with GO suspensions in water of different concentrations as shown on the individual frames; σHAP=9.99, 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M.

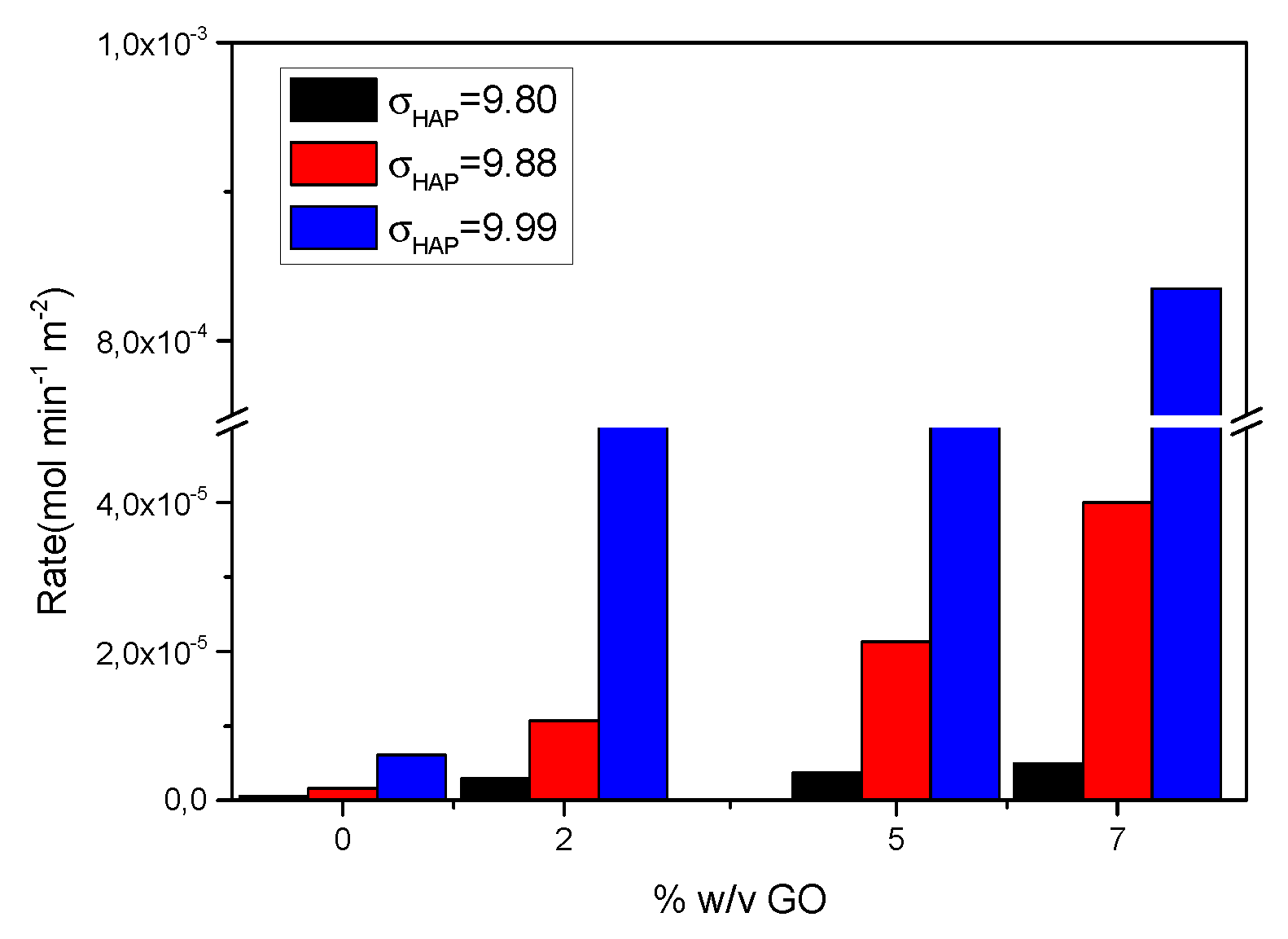

Figure 18.

HAP crystal growth rates on GO-coated IOLs as a result of their equilibration with aqueous suspensions of GO of various concentrations (2x10-4, 5 x10-4 and 7x10-4 %w/v GO), at different relative supersaturation values with respect to HAP; 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M.

Figure 18.

HAP crystal growth rates on GO-coated IOLs as a result of their equilibration with aqueous suspensions of GO of various concentrations (2x10-4, 5 x10-4 and 7x10-4 %w/v GO), at different relative supersaturation values with respect to HAP; 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M.

Figure 19.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of HAP crystals grown from supersaturated solutions, of different relative supersaturation values with respect to HAP, on GO-coated IOLs (a) σHAΡ=9.80 (IOLs equilibrated with 2x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water); (b) σHAP=9.88 (IOLs equilibrated with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water), (c) σHAP=9.99 (from IOLs equilibrated with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water); 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl.

Figure 19.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of HAP crystals grown from supersaturated solutions, of different relative supersaturation values with respect to HAP, on GO-coated IOLs (a) σHAΡ=9.80 (IOLs equilibrated with 2x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water); (b) σHAP=9.88 (IOLs equilibrated with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water), (c) σHAP=9.99 (from IOLs equilibrated with 5x10-4 % w/v GO suspension in water); 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl.

Figure 20.

HAP crystal nucleation and growth on hydrophilic, PHEMA IOLs with different types of functional groups on their surface (a) without treatment and (b) coated with graphene oxide.

Figure 20.

HAP crystal nucleation and growth on hydrophilic, PHEMA IOLs with different types of functional groups on their surface (a) without treatment and (b) coated with graphene oxide.

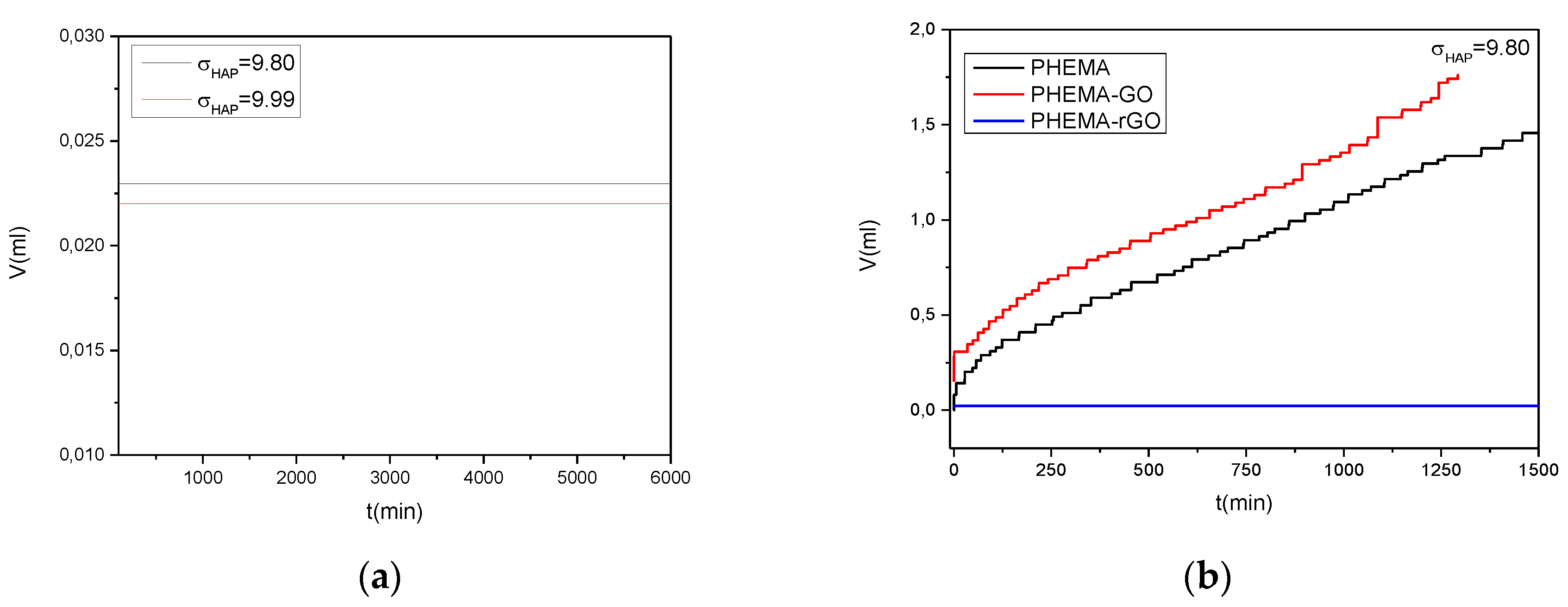

Figure 21.

Added volume of titrant solutions to maintain constant supersaturation, during HAP crystal growth in supersaturated solutions, induced by hydrophilic IOLs coated with rGO; (a) rGO coated hydrophilic IOLs; σHAP=9.80 and σHAP=9.99 (b) Coating free, GO coated and rGO coated hydrophilic IOLs, σHAP=9.80; 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl.

Figure 21.

Added volume of titrant solutions to maintain constant supersaturation, during HAP crystal growth in supersaturated solutions, induced by hydrophilic IOLs coated with rGO; (a) rGO coated hydrophilic IOLs; σHAP=9.80 and σHAP=9.99 (b) Coating free, GO coated and rGO coated hydrophilic IOLs, σHAP=9.80; 37oC, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl.