Introduction

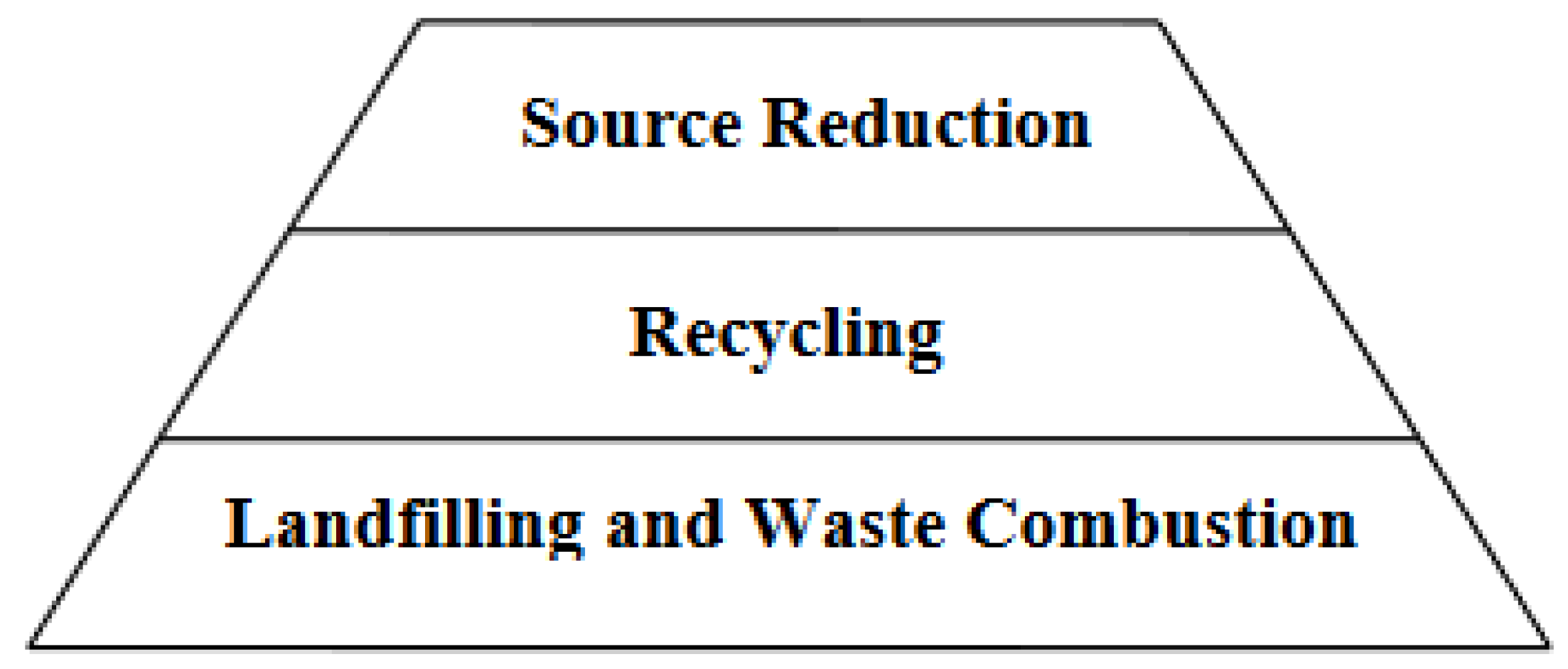

In today’s world, the urgent need for sustainable waste management practices has become increasingly evident. Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex, a major player in the petrochemical industry, recognizes the significance of promoting environmental sustainability in their waste management planning. This research aims to revolutionize waste management strategies within the complex, aligning them with sustainable development principles. By examining the findings of various studies and reports, we can identify effective approaches to enhance waste management practices and minimize their environmental impact. General Overview - Background of the Study: The World Commission on Environment and Development, as highlighted by Brundtland (1987), emphasized the importance of sustainable development in balancing economic growth with environmental conservation. The Waste Management Hierarchy, as outlined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2019), advocates for waste reduction, recycling, and energy recovery as preferred approaches over disposal, providing a framework for sustainable waste management practices.. Gandy (1994) revealed the political and social dimensions of waste management, emphasizing the need to address environmental justice concerns and ensure equitable access to waste management services. The concept of the circular economy, as discussed by McDonough and Braungart (2002), presents a transformative approach by designing products and systems that minimize waste generation and promote resource reuse. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2018) identifies responsible consumption and production as a crucial aspect of sustainable development, urging industries to adopt efficient waste management practices. The World Bank’s report on solid waste management (2012) identifies the global challenges associated with waste generation and emphasizes the need for integrated waste management systems to reduce environmental and health risks. Zhang, Wang, and Zhang (2018) highlight the challenges and prospects of industrial solid waste management in China, providing insights into effective waste management strategies that can be adapted and implemented in other contexts. Meikle (2007) emphasizes sustainable construction practices as part of a comprehensive waste management approach, highlighting the importance of reducing waste generation during the construction phase. Lester, Hill, and Piwowar (2010) outline principles of sustainable development, emphasizing the need to balance economic prosperity with environmental and social considerations, which can guide waste management planning. Avrami, Mason, and deSilva (2010) emphasize the intrinsic value of cultural heritage in waste management planning, suggesting that preservation and reuse of historical structures can contribute to sustainable development.

Adams et al. (2004) highlight the importance of biodiversity conservation in eradicating poverty, emphasizing the need for waste management strategies that minimize ecological disruption and protect natural resources. Campbell (1996) discusses the contradictions of sustainable development in urban planning, emphasizing the need for waste management practices that prioritize social equity and environmental stewardship. Cole (2004) explores the rise of the environmental justice movement and how waste management practices can disproportionately impact marginalized communities, emphasizing the importance of addressing environmental racism in waste management planning. Deakin and Reid (2019) provide a comparative analysis of planning systems, offering insights into different approaches to waste management planning and their effectiveness in promoting sustainability. Ekins (2000) explores the prospects for green growth, highlighting the economic benefits of integrating sustainable waste management practices and the potential for sustainable development. Harvey (2012) discusses the right to the city and the potential for urban revolution, emphasizing the role of waste management planning in promoting social and environmental justice. Jackson (2009) challenges the notion of unlimited economic growth and explores the concept of prosperity without growth, advocating for waste management strategies that prioritize resource efficiency and decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation. Mol (2003) discusses the ecological modernization of the global economy and the potential for waste management practices to drive sustainable development on a global scale. Newman and Kenworthy (2015) provide insights into the twentieth-century experience of urban planning, highlighting the importance of waste management planning in creating sustainable and livable cities. Pearce (2002) discusses the measurement of sustainable development, offering frameworks and indicators that can guide waste management planning and assess its contribution to sustainability. Rittel and Webber (1973) present the concept of wicked problems in planning, emphasizing the complex nature of waste management and the need for innovative and adaptive approaches to address sustainability challenges. Sachs (2015) explores the interconnectedness of social, economic, and environmental factors in sustainable development, highlighting the role of waste management planning in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The UN Environment Programme (2017) provides a global strategy framework for waste and climate change, emphasizing the importance of waste management in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and promoting a low-carbon future. The United Nations Development Programme (2018) highlights the importance of waste management in achieving responsible consumption and production, calling for sustainable waste management practices as part of the global sustainability agenda. World Bank (2012) offers a comprehensive review of solid waste management globally, identifying challenges and providing recommendations for improving waste management systems. The Getty Conservation Institute’s research report on the values and benefits of cultural heritage (Avrami, Mason).

As we delve deeper into the study, we will explore how these findings and concepts can be applied to revolutionize waste management planning in Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex. By integrating sustainable waste management practices, we aim to minimize environmental impact, enhance resource efficiency, and promote a circular economy within the complex.

Significance of Revolutionizing the Waste Management Planning in IEPL

- ➢

Waste management is essential for every type of manufacturing process, and putting forward-thinking practises into effect can have a materially beneficial effect on the outcome. It’s great to see that the Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex is dedicated to figuring out innovative approaches to the problems that arise with waste management.

- ➢

You will be able to reduce the negative effects that the complex’s activities have on the surrounding environment if you modernise the planning for waste management. The implementation of recycling programmes, the reduction of waste creation, and the investigation of alternative waste treatment technologies might all be part of this solution. These activities not only advance the cause of sustainability but also make a contribution to the circular economy by ensuring that items that would otherwise be discarded are given a second chance at life.

- ➢

In addition, the Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex can benefit from a more favourable public view by highlighting the necessity of environmentally friendly waste management practises. Customers and other stakeholders place a high value on environmentally responsible business practise, which may help an organization improve its reputation and entice new environmentally conscientious partners.

The research on revolutionizing waste management planning in Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex aligns with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Here are the Relevant SDGs that the Research Aims to Contribute to:

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production: The research aims to promote responsible consumption and production practices by implementing sustainable waste management strategies that minimize waste generation, promote recycling and resource recovery, and reduce the environmental impact of the complex.

SDG 13: Climate Action: By improving waste management practices and reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with waste generation, the research contributes to climate action efforts.

SDG 14: Life Below Water and SDG 15: Life on Land: The research aims to minimize environmental pollution and protect ecosystems by implementing waste management practices that prevent the release of hazardous substances into water bodies and soil, thereby contributing to the conservation of marine and terrestrial environments.

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure: By exploring innovative waste management strategies and technologies, the research aims to contribute to the development of sustainable and efficient infrastructure within the petrochemical industry.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: The research aims to enhance waste management practices within Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex, which can contribute to the creation of sustainable communities and cities by reducing pollution and promoting circular economy principles.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals: The research highlights the importance of collaboration and partnerships with various stakeholders, including government agencies, industry experts, and local communities, to achieve sustainable waste management practices and the broader SDG agenda. By addressing these SDGs, the research aims to contribute to the global sustainability agenda and promote a more environmentally friendly and socially responsible approach to waste management within Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Operational Complex.

Material and Methods

Research on A Specific Case and the Gathering of DATA

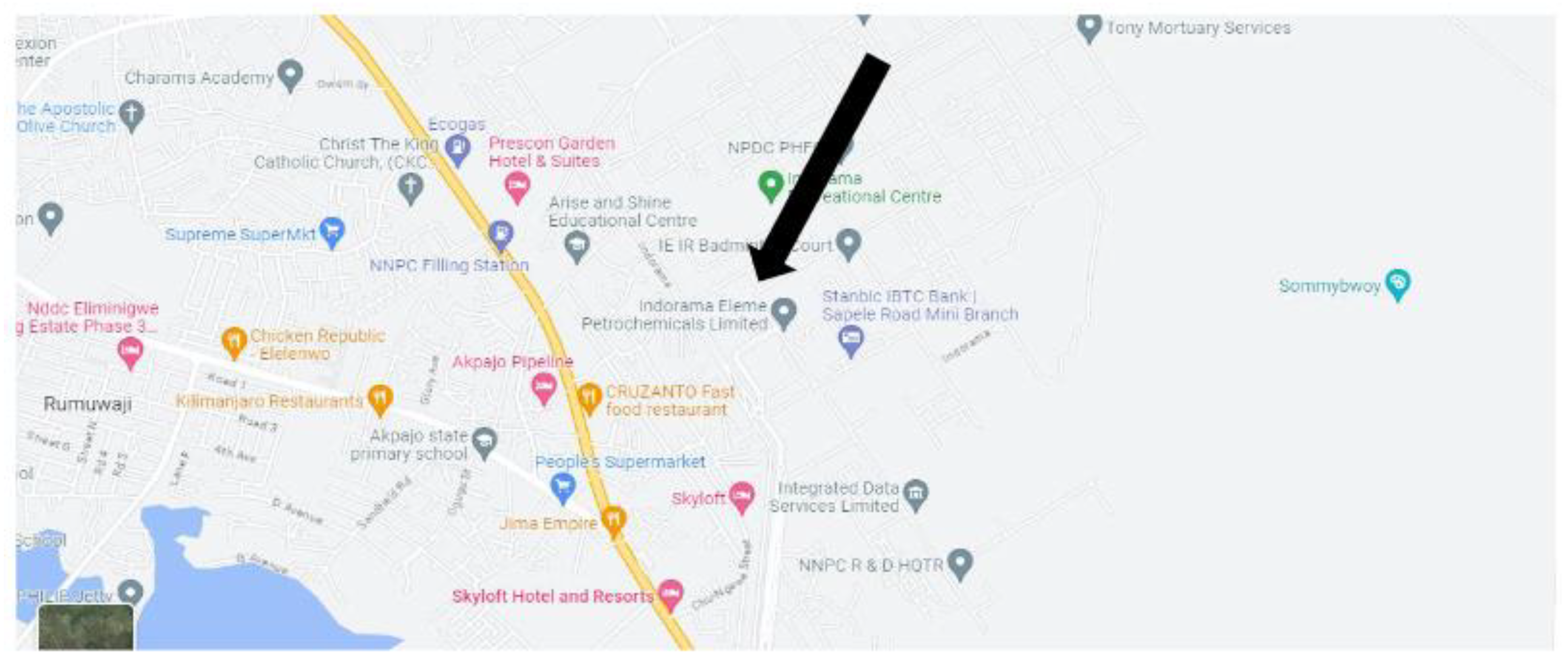

Within the boundaries of the petrochemical exceptional economic zone (PEEZ), there are a total of sixteen petrochemical complexes. The zone may be found in the Eleme port, which is situated on the coast of the Onne Rivers state. One of these complexes is known as Indorama Eleme Petrochemical Limited (IEPL), and it takes up a total of 55 hectares of land.

Figure 1 illustrates where IEPL stands in relation to the several other petrochemical facilities at Eleme port.

IEPL began its activities in 2006 but did not officially launch its operations until 2012. The primary outputs of the complex are crude fuel oil, linear low-density poly ethylene, high-density poly ethylene, 1-butene, propylene, and 1, 3-butadiene. Additionally, the complex produces high-density poly ethylene.

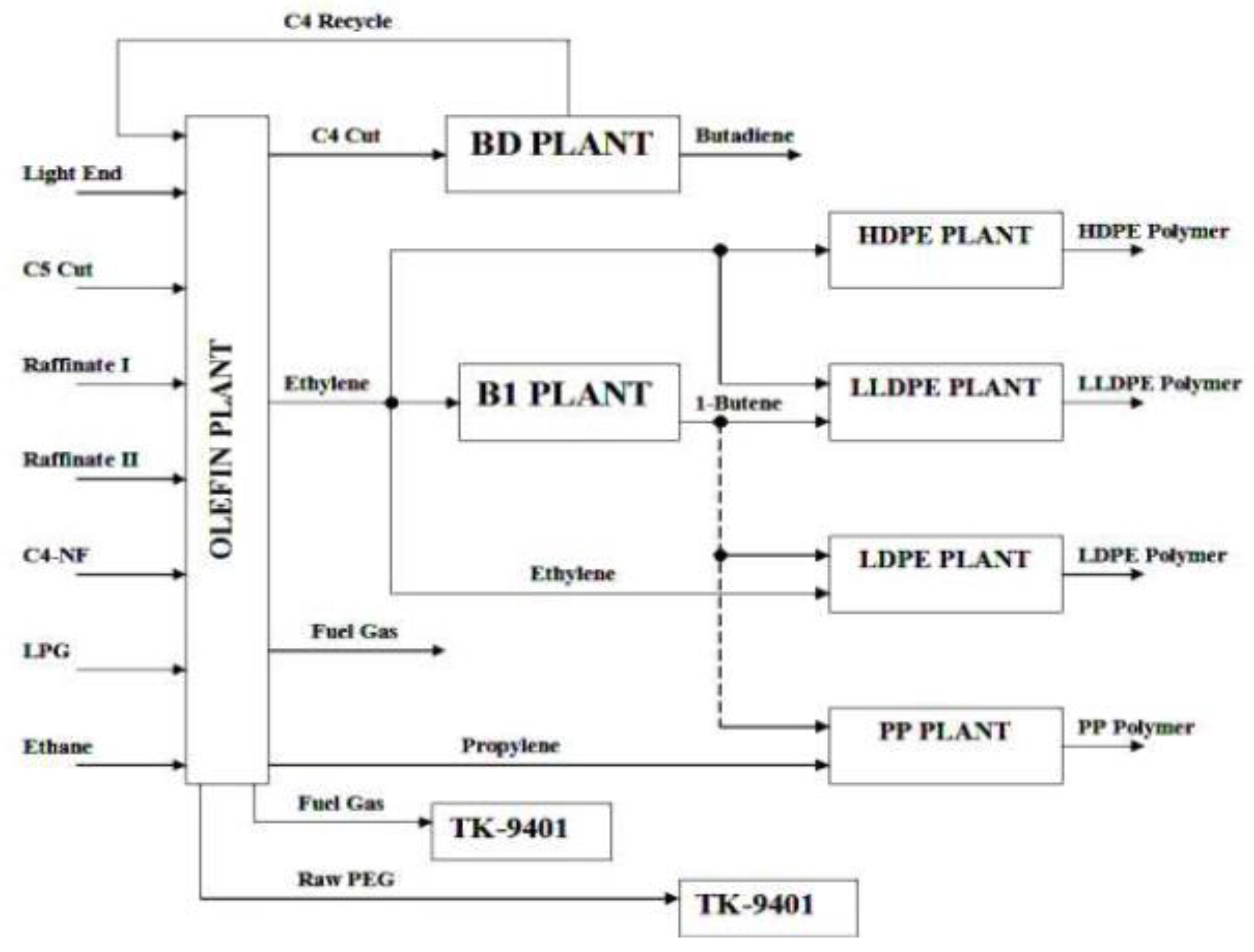

Figure 2 depicts an overarching perspective of generating units along with the associated raw materials and finished goods. As can be seen in

Figure 2, IEPL is composed of five different units, the most notable of which are the linear low-density poly ethylene unit (LDPE), the high-density poly ethylene unit (HDPE), the 1-butene unit, the butadiene unit, and the olefin unit. The production of olefin is a significant part of the petrochemical industry. The thermal breakdown of hydrocarbons is a crucial step in the production of olefin. The LDPE unit and the HDPE unit both receive their input from the olefin unit. Butane, hydrogen, and catalysts are the feedstock for HDPE units. Following the completion of the polymerization process, the output products went into centrifuges, where the powder and hexane were separated. After that, the hexane is purified so that it may be reused, and extruders are used to remove the water from the powder and granulate it. The chemical process that produces LDPE takes place under high pressure. Organic peroxides are introduced at several points during the process in order to initiate the reaction. In the presence of ethylene, propene, and propylene, as well as high pressure, the polymerization process will commence, and extruders will be used to send the powder to be granulated

At the present time, three distinct approaches have emerged as the most popular choices for analyzing the generation, kind, and content of industrial waste (Monahan, 1990):

- ➢

An empirical method that makes use of the information that is readily accessible from the industry

- ➢

A questionnaire surveys

- ➢

The use of control and monitoring data from a waste management system

- ➢

Documentation of waste emission lists that have been provided by designers., to name just a few examples from international research, provide instances of employing questionnaires to examine the amount and quality of industrial wastes, along with the management and control techniques utilized. In light of earlier study carried out not only in Iran but also in other countries (Abduli, 2005), the research group that we belong to produce a questionnaire about the operational components and organizational framework of petrochemical waste management practises. It included details on a number of topics, including the following:

- 1.

Some background information:

- 1.1

The name of the unit;

- 1.2

Primary resources and finished goods;

- 1.3

Types of waste and their constituents.

- 2.

Information on the trash that was produced, including:

- 2.1

The volume or weight of garbage, according to its design and its real value;

- 2.2

The frequency with which waste was produced;

- 2.3

The type of waste containers that were used for on-site storage and the frequency with which they were collected.

- 3.

Information on the present state of waste management

- 3.1

Methods for the collection of trash

- 3.2

Methods now in use for the disposal of waste;

- 3.3

Methods for the disposal of waste that have been suggested by the plant designer for waste that will be generated in the future.

For the purpose of gathering accurate information, questionnaires were distributed to the managers of environmental, processing, operating, repairing, and municipal waste collection sections and laboratories. Additionally, face-to-face interviews were carried out with the managers of the aforementioned sections. The information gathered during these processes was then compiled into a report.

Waste Categorization

An essential process in managing petrochemical wastes effectively. Various classification systems, such as those established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Basel Convention, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), provide guidelines for identifying and managing different types of wastes. To advance waste categorization further, we can explore technological solutions that improve waste identification and segregation. For instance, implementing advanced sensors and artificial intelligence algorithms can help automate the sorting process, ensuring more accurate and efficient waste classification. This technology can identify specific chemical properties, physical characteristics, or even patterns to classify wastes more precisely. Additionally, enhancing waste tracking systems and implementing blockchain technology can contribute to improving waste categorization. This would enable better traceability and transparency throughout the waste management chain, ensuring proper disposal or recycling of petrochemical wastes. By combining these innovative approaches with ongoing research and collaboration between industries, governments, and environmental organizations, we can advance waste categorization to a more comprehensive and meaningful level. This will ultimately lead to better management and reduction of petrochemical waste, promoting a cleaner and more sustainable future. The purpose of waste categorization is to facilitate informed management decisions regarding the appropriate handling and treatment of petrochemical wastes. With the advancement of technology and evolving environmental concerns, categorization methods have indeed been modernized to align with current environmental standards. These modernization efforts aim to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of waste categorization. By incorporating scientific advancements, updated regulations, and considerations for environmental impact, the categorization methods can better reflect the potential risks and opportunities associated with different types of petrochemical wastes. For example, there has been a shift towards promoting waste recovery and recycling as sustainable alternatives to landfilling or incineration. As a result, categorization methods now place greater emphasis on identifying recyclable materials and encouraging their proper reutilization in order to reduce waste generation and minimize environmental harm. Furthermore, the integration of digital platforms and databases has made it easier to access and update waste categorization information. This allows for more efficient decision-making processes and enables stakeholders to make informed choices regarding the sale, treatment, or disposal of petrochemical wastes. Overall, the modernization of waste categorization methods ensures that management decisions align with current environmental concerns and promote sustainable practices. By staying up-to-date with advancements in technology and environmental awareness, we can continue to improve the categorization process and make more informed choices for the betterment of our environment.

Dividing garbage into distinct categories is indeed a crucial step in exercising complete control over its disposal. The ten categories you mentioned, ranging from laboratory waste to plant trash, provide a comprehensive framework for classifying different types of waste. Assigning unique codes, or "form codes," to each group enhances the efficiency and accuracy of waste management processes. By categorizing waste into specific groups, it becomes easier to implement appropriate disposal methods for each category. For instance, laboratory waste may require specialized handling to ensure safe disposal, while organic and inorganic liquids may have different treatment requirements. Having distinct categories helps in making informed decisions about the most suitable disposal methods, such as recycling, incineration, or landfilling. Furthermore, these form codes enable streamlined documentation and tracking of waste throughout its lifecycle. By associating each waste category with a unique code, it becomes easier to record and communicate information about the waste’s origin, composition, and recommended handling procedures. This ensures proper management and enables regulatory compliance. As waste management practices continue to evolve, these categories and form codes can be periodically reviewed and updated to reflect advancements in technology, environmental regulations, and best practices. This ensures that waste disposal remains efficient, safe, and aligned with current environmental standards. Remember, proper waste categorization and disposal are essential for preserving the environment and promoting a sustainable future.

Waste Classification

A consistent waste labelling and classification system is crucial for effective waste management in IEPL petrochemical mills. This system enables waste generators to navigate waste routes seamlessly, ensuring proper handling and disposal throughout the waste management process. To achieve this, a comprehensive coding system should be implemented, incorporating waste characterizations. This means that each waste generated within the mills should be categorized and labeled based on its specific characteristics, such as chemical composition, physical properties, and potential environmental impacts. By including waste characterizations in the coding system, it becomes easier to identify and track the types of wastes being generated. This information is essential for making informed decisions on appropriate treatment, disposal, or recycling methods. For example, hazardous wastes can be identified through specific codes, allowing for their safe handling and disposal in compliance with regulations. Additionally, such a coding system enables waste generators to communicate and coordinate effectively with waste management personnel and facilities. It streamlines the process of identifying the correct disposal routes, ensuring that wastes are transported and treated in accordance with their characterizations and regulatory requirements. Regular updates and training on the coding system are crucial to ensure its effectiveness and to keep up with changes in waste composition or regulations. This ensures that waste management practices remain consistent, efficient, and in line with environmental standards. By implementing a coding system that includes waste characterizations, PPEZ petrochemical mills can enhance waste management processes, promote safe disposal, and contribute to a more sustainable environment.

That sounds like a comprehensive and detailed waste classification system! By utilizing thirteen-digit codes consisting of various elements, such as the waste generator’s name, waste stream number, code form, waste source, and waste hazard component code, each waste type can be uniquely identified and labeled. Having a unique code for each waste type facilitates efficient tracking, documentation, and communication of waste information throughout its lifecycle. This enables waste generators to navigate waste routes accurately and ensures that waste management personnel and facilities can easily identify and handle specific waste types based on their characteristics. The inclusion of the waste source (industrial, agricultural, medical, or non-industrial) in the code provides additional context about the origin of the waste. This information can be valuable in determining appropriate treatment or disposal methods, as different waste sources may have specific regulations or requirements. Furthermore, the incorporation of the waste hazard component code helps in assessing and managing the potential risks associated with handling and disposing of the waste. By including this component, it becomes easier to identify hazardous waste and take necessary precautions to ensure safe handling and disposal. Overall, this detailed labeling system with thirteen-digit codes provides a comprehensive approach to waste classification, enabling efficient waste management and ensuring compliance with regulations. It allows for clear identification and tracking of waste types, enhancing communication and decision-making throughout the waste management process.

Results and Discussion

Trash that isn’t produced by the procedure Process waste and non-process waste are the two categories that make up industrial waste. Sources and processes, other than those involved in production, are responsible for the generation of non-process wastes. The generation rates of the petrochemical solid wastes are connected to their nature and are directly proportionate to the amount of the processes that create them. Since these wastes are formed by a variety of processes that support industrial activities, their generation rates are tied to their nature. Offices of the plant, the staff café, labs, cutting down trees or plants, and other personnel-related activities are all sources of non-process industrial solid waste (ISW). The local council was responsible for collecting and transporting this sort of rubbish to the disposal place along the Onne Highway. In the Eleme medical incinerator, medical wastes were disposed of in a distinct manner before being burned.

Figure 3 depicts the weight percentages of municipal, agricultural, and municipal trash. It should be mentioned that in total, 14.9% of wastes constituted non-process ISW, while 85.1% of wastes were processed ISW.

Waste from the Process

Following an investigation into the procedure, the solid wastes of IEPL’s 68 locations of origin for waste creation were located. These activities result in the annual generation of 3115.98 tonnes of solid garbage. The table below provides an inventory of the wastes produced by the IEPL process. The updated categorization method divides waste into four different danger classifications depending on the specific features of the wastes, which are as follows: According to RCRA, class H refers to wastes that possess hazardous properties. Class 1 wastes are those that are polluted by a toxic pollutant at a level that is above the standard threshold (for example, water that has been contaminated by ethylene glycol). Class 2 wastes have not contained or been mixed with the waste of class H but have a minimal degree of hazard after disposal. Class 3 wastes are considered inert and have no negative impact on the environment. The rate of creation for each class is displayed in

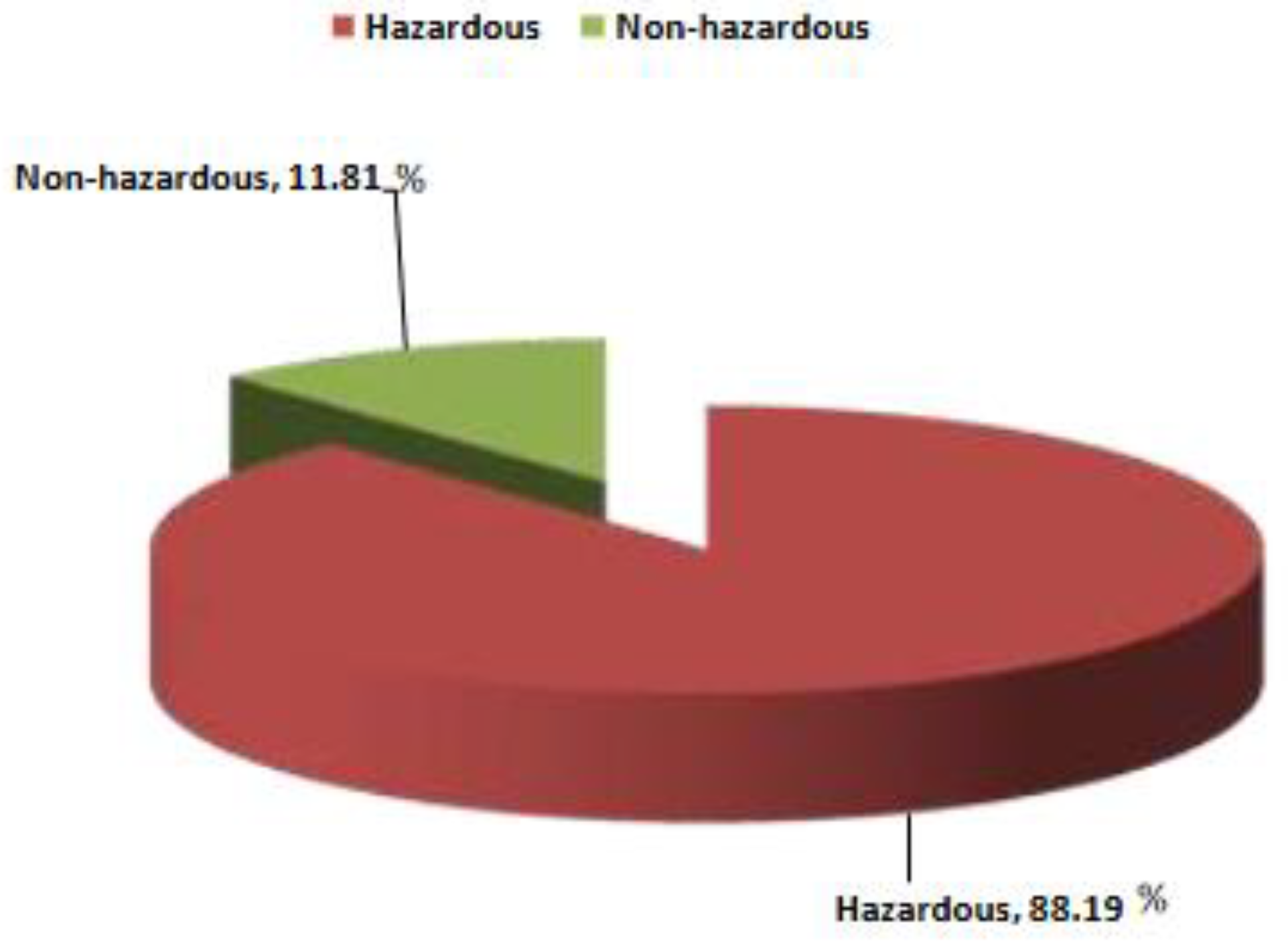

Figure 5. According to the data presented in

Figure 4, 88.19% of the solid wastes created in this complex were hazardous, while only 11.81% of them were a non-hazardous waste. Because of this, potentially harmful waste, especially oil and catalysts, needs to be handled prior to removal.

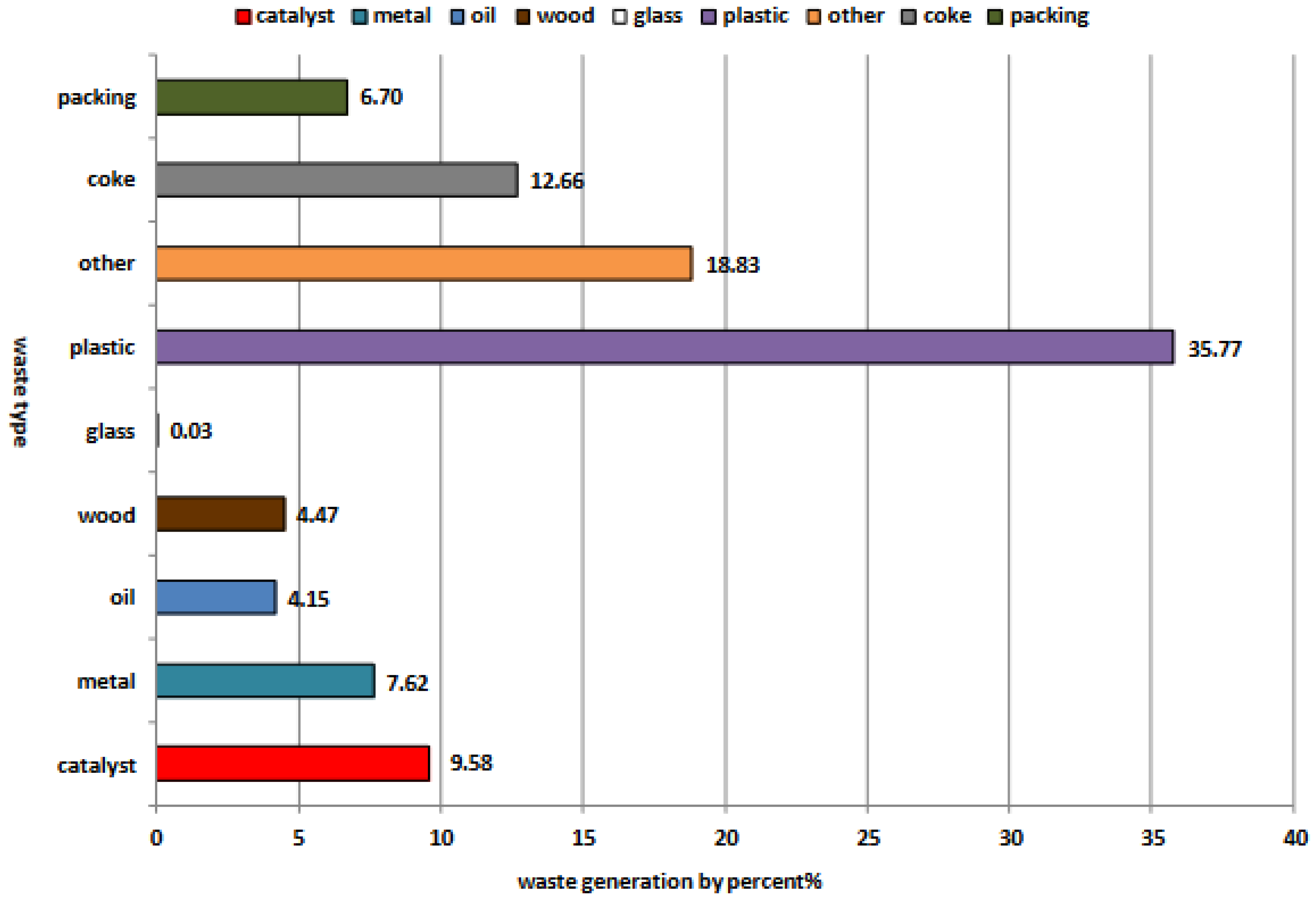

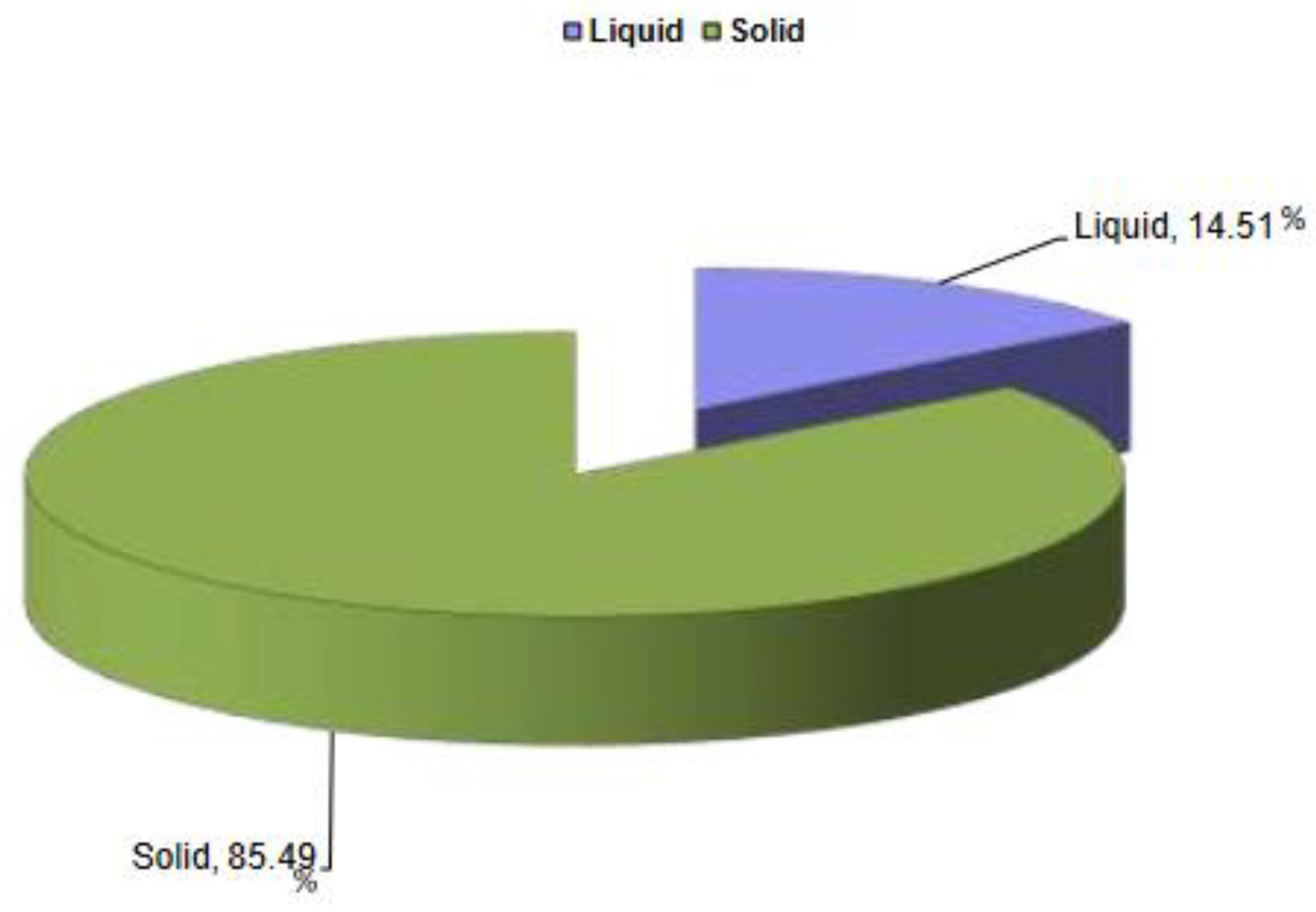

Figure 5 depicts the most common sorts of garbage. It was discovered that the wastes produced at IEPL are composed of 18.83% additional waste material, 9.58% catalysts, 7.62% metallic materials, 35.77% plastic barrels, 12.66% coke, 4.47% wood, 4.15% oil, 0.028% glass, and 6.7% cooling tower packaging. It is important to point out that catalysts make up the bulk of the solid wastes. According to the findings of an examination of the created waste’s physical qualities, only 14.41% of the materials analysed were liquid, while the remaining 85.49% comprised solid (

Figure 6).

An Analysis of the Currently Employed and Suggested Waste Management

The information shown in

Table 2 demonstrates that certain wastes are not managed in an appropriate manner. Handling, processing, and disposal of wastes should not have a negative influence on the surrounding environment. This is the foundation of proper management. Because of this, waste management was an absolute requirement. 35.51% of the total wastes are kept in storage, while 11.92% are burned in an incinerator; this does not include the byproducts that are sold. Additionally, there will be wastes in the future accounting for 11.94% of the total. It has not given any specific thought to the treatment of such garbage. The data analysis reveals several issues with the current IWM, which are outlined in the following order:

- ➢

At the moment of generation, there were no specified conditions for the temporary storage of garbage, particularly hazardous waste.

- ➢

With the exception of certain hazardous trash, we have not explored using labelled containers.

- ➢

The way of handling the salvage was not enough.

- ➢

Some hazardous materials held for more than ninety days.

- ➢

Waste products that are incompatible with one other were kept in the temporary storage location.

- ➢

The temperature, isolation, light, and other aspects of the HW storage site were not under the owner’s control.

- ➢

The landfill was filled with recoverable wastes such as catalytic sludge, catalyst, and plastics.

- ➢

The qualities of the wastes did not measure, and the composition of some of the trash was not clear.Waste that was not generated by the process was let to accumulate.

When it comes to managing a community’s waste stream, integrated solid waste management refers to the practise of employing a variety of strategies and programmes. Planners are able to customize integrated waste management systems to meet the particular requirements of individual communities. This allows them to take into account the fact that different communities generate different types and amounts of garbage. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposes adopting the following hierarchy as a tool for defining objectives and organizing actions related to waste management (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hierarchy of integrated solid waste management.

Figure 6.

Hierarchy of integrated solid waste management.

Source Reduction: At the top of the hierarchy is source reduction, which focuses on minimizing waste generation at the source. This involves implementing practices that reduce the amount of waste produced, such as promoting the use of reusable products, encouraging responsible consumption, and implementing efficient production processes.

Recycling: The next level in the hierarchy is recycling, which involves the collection, sorting, and processing of materials to create new products. Recycling helps conserve resources, reduce energy consumption, and minimize the need for raw: material extraction. It includes processes like paper, plastic, metal, and glass recycling.

Landfilling: Next in the hierarchy is landfilling, which involves the disposal of non-recyclable and non-compostable waste in designated landfill sites. Landfills are engineered to minimize environmental impact and prevent contamination of soil and water. However, landfilling should be considered a last resort due to its negative environmental implications. Waste Combustion: At the bottom of the hierarchy is waste combustion, which includes processes such as incineration and waste-to-energy conversion. Waste combustion involves the controlled burning of waste to generate energy. This can help reduce the volume of waste and recover energy, but it should be implemented with proper emission controls to minimize air pollution. It’s important to note that the hierarchy promotes a shift towards waste reduction, recycling, and reuse, as these options have lower environmental impacts compared to landfilling and waste combustion. By prioritizing source reduction and recycling, we can minimize the amount of waste that ends up in landfills or requires combustion, thereby promoting sustainability in waste management practices.

As previously stated, the majority of wastes created in the petrochemical industry pose a risk. The next section describes the best methods for management. Many companies reuse or recycle waste products as raw materials in their manufacturing processes. There is intra- and inter-industry reuse and recycling. Material waste are collected from point of generation and utilized directly in industrial operations or recycled for ultimate use within the same industry in intra-industrial reuse and recycling. It is worth noting that the recovery of valuable ISW materials for recovery and recycling occurs at virtually all phases of industrial operations, from raw material loading through completed product packaging.

Table 3 shows that 39.34% of wastes are recyclable and reused, whereas 5.12% are ignitable. Waste recovery is cost-effective and one of the finest waste management choices. These technological methods can eliminate trash collection expenses, reduce raw material prices, and generate extra cash by selling garbage to recovery centres. Hexane waste is recyclable and reusable. Because wasted catalysts include precious metals as well as harmful and dangerous elements, they should be retrieved. Recovery potential exists for metallic materials, oil, wasted resin, and absorber. Because of their tiny volume and high toxicity, laboratory samples should be simply cremated. All garbage will be managed correctly when the system for the management of solid waste has been activated. As a result, the negative environmental consequences of wastes may be avoided; waste-occupied space can be eliminated; and extra cash can be acquired.

Conclusions

The use of questionnaires to collect data on the production, characterization, and management of waste from industry should be supplemented by additional studies on the kind of industrial activity in the research region. This would eliminate some of the issues connected with this technique of data collecting. The knowledge that was acquired offered an approximate estimate of the number of created wastes, as well as their features and composition. Nonetheless, the utilization of control/monitoring data from a waste management system is required to gain more exact information. Aside from off-quality goods, the most substantial waste groups in terms of volume are catalyst, oil, absorber, resin, and cooling system packaging. These wastes were categorized based on their physical and toxic qualities. System flaws were discovered after assessing the current waste management system. Occupied waste area and danger potential were quite high, and some wastes were overlooked in an appropriate solution for them. We identified the most effective waste management choices based on the most important type of how to manage waste. Waste may be collected in 39.33% of cases, burnt in 5.12% of cases, and landfilled in 19.05% of cases. An effective waste management system assists us in mitigating the negative environmental effects of trash while also providing numerous additional advantages.

Recommendation

Ø Implement a thorough waste segregation system: Promote the use of a color-coded waste segregation system that distinguishes clearly between different forms of garbage. This will make garbage categorization and handling easier, since recyclable and non-recyclable items will be correctly segregated.

➢

Invest in waste-to-energy technology such as anaerobic digestion or incineration to transform organic waste into sustainable energy sources. This can contribute to the company’s environmental goals by reducing landfill trash.

➢

Create a rewards system that encourages employees to actively participate in recycling efforts by introducing a recycling incentive programme. This might involve offering incentives like as recognition, bonuses, or even modest awards to employees or departments who consistently display outstanding recycling practises.

➢

Implement a strong monitoring and reporting system: Create a waste management tracking system that keeps track of waste creation, disposal methods, and recycling rates. This information will assist in identifying areas for improvement and measuring the impact of adopted efforts, enabling for continual development of waste management techniques.

➢

Collaborate with local communities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs): Build relationships with local communities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that specialise in waste management and sustainability. This collaboration may give significant insights, resources, and knowledge-sharing opportunities, allowing the complex to use collective expertise and promote good change.

➢

Educate and create awareness: Provide frequent training sessions, workshops, and awareness campaigns to staff to educate them on the importance of waste management and sustainable practises. Provide them with the information and resources they need to make sound decisions and actively participate to the complex’s sustainability initiatives.

Author Contributions

The first author wrote the draft under the guidance of the second author on the theme and content of the paper.

Funding

The Author(s) declares no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the researchers and academics who have made important, trustworthy, and accurate material on all areas of Petrochemical Industry readily available. This contributed to the overall success of the study’s development.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, W.M.; Aveling, R.; Brockington, D.; Dickson, B.; Elliott, J.; Hutton, J.; Vira, B. Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty. Science 2004, 306, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avrami, E.; Mason, R.; deSilva, S. Values and Benefits of Cultural Heritage: Research Report; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. The New Science of Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, R.B.; Churchman, A. Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our common future: The World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S. Green cities, growing cities, just cities? Urban planning and the contradictions of sustainable development. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deakin, M.; Reid, A. Comparative Planning Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, P. Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability: The Prospects for Green Growth; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency. 2019. Waste Management Hierarchy. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/smm/waste-management-hierarchy.

- Gandy, M. Recycling and the Politics of Urban Waste; Earthscan: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Indorama Eleme Petrochemicals. (n.d.). Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.indoramaplc.com/sustainability.

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, R.K.; Hill, M.; Piwowar, M.L. Principles of Sustainable Development; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Meikle, J. Sustainable Construction; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P. Globalization and Environmental Reform: The Ecological Modernization of the Global Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J.R. Urban Planning in a Changing World: The Twentieth Century Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W. Blueprint 3: Measuring Sustainable Development; Earthscan: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment Programme. Waste and Climate Change: Global Trends and Strategy Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/waste-and-climate-change-global-trends-and-strategy-framework.

- United Nations Development Programme. Waste Management. 2018. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-12-responsible-consumption-and-production/targets/12-4.html.

- World Bank. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/17388.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Industrial solid waste management in China: Challenges and prospects. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 622–629. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).