Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

27 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

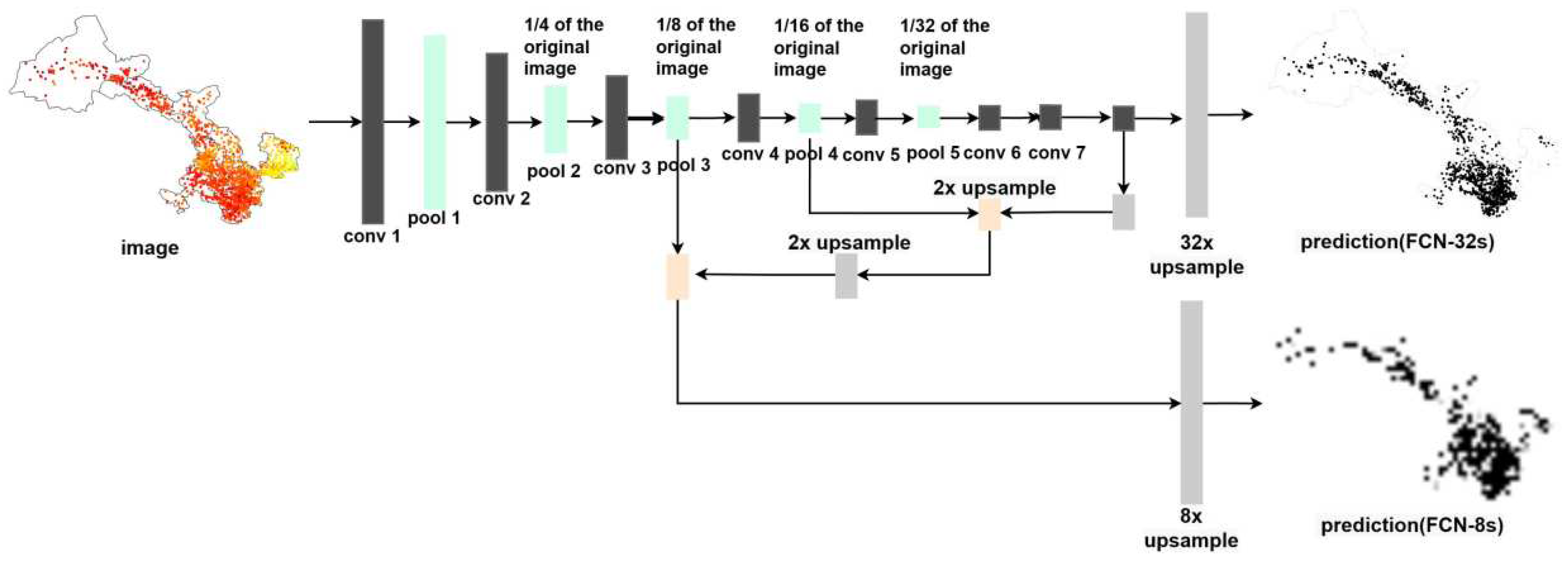

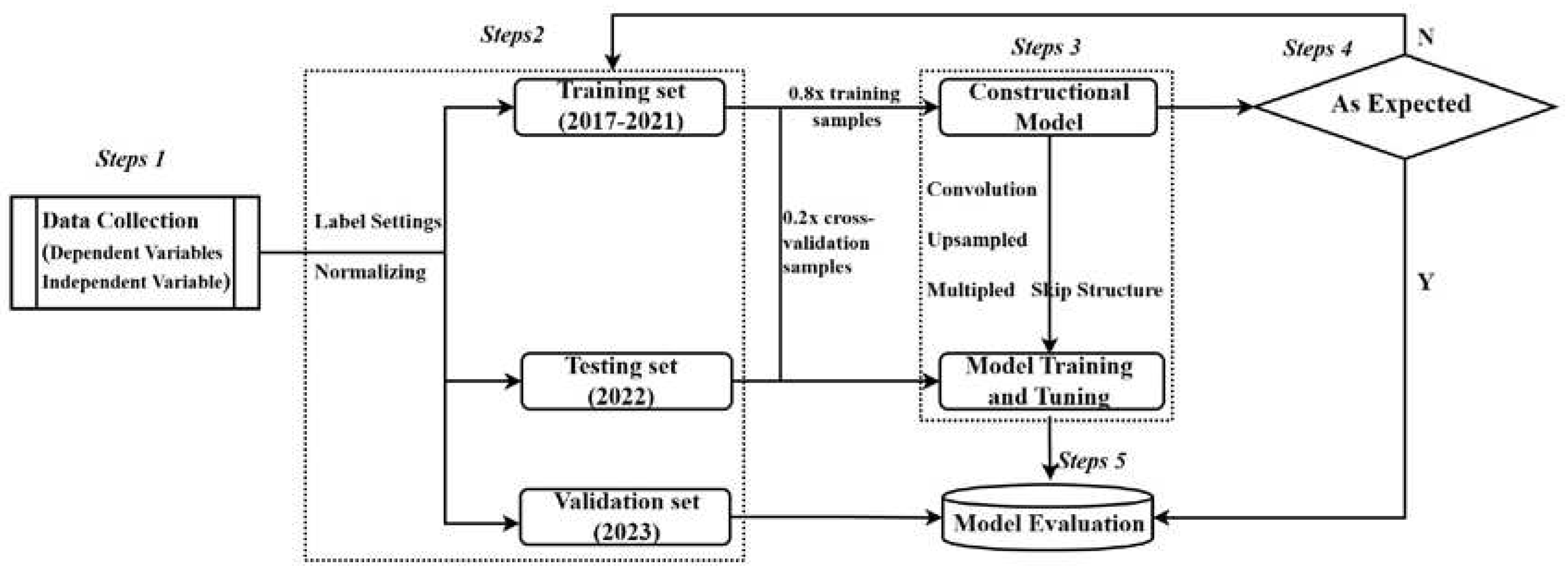

2. FCN Algorithm and Model Construction

3. Data Used and Model Validation Methods

3.1. Introduction of Independent Variables for Modeling

3.2. Introduction of Dependent Variables and Samples for Modeling

3.3. Model Validation Indicators

4. Results Analysis

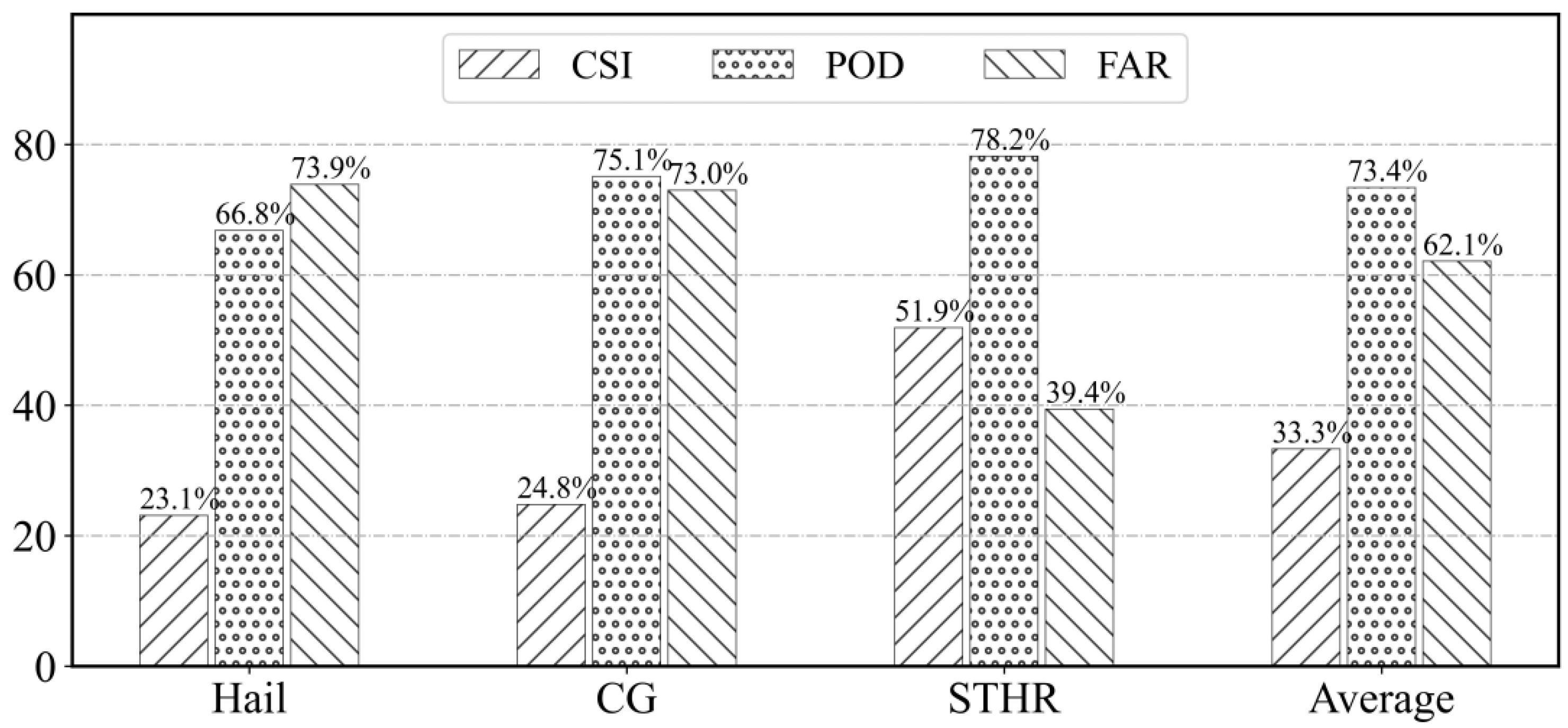

4.1. Training Set Effectiveness Evaluation

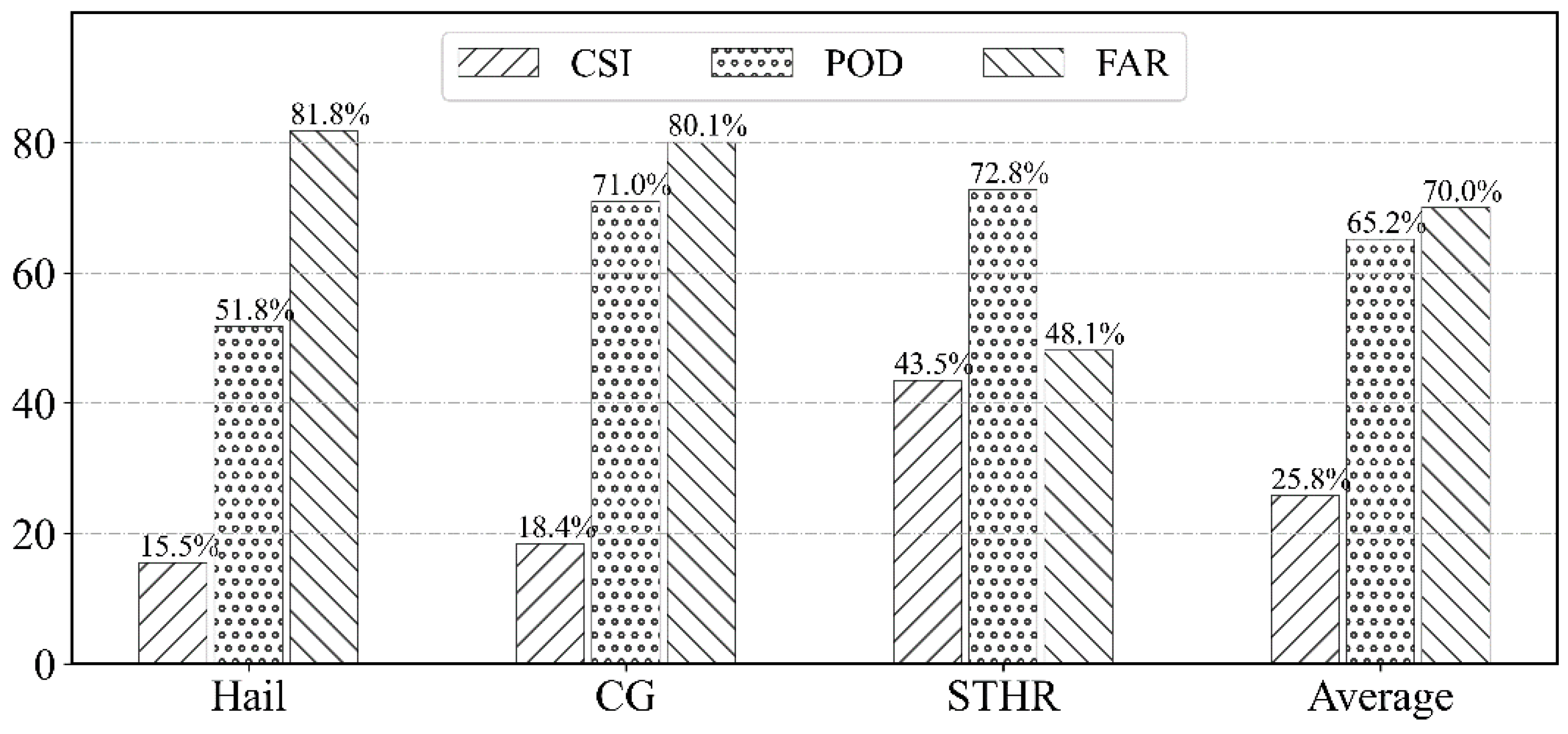

4.2. Independent Test Set Effectiveness Evaluation

4.3. Independent Validation Set Effectiveness Evaluation

4.4. Hourly Effectiveness Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussions

- (1)

- Within the 2017-2021 training set, the FCN model attained an overall misjudgment rate of 16.6% for severe convective weather. Specifically, the lowest misjudgment rate was for STHR at 21.8%, while the highest was for hail at 33.2%, and the misjudgment rate for non-severe convective weather was 15.7%. In terms of scoring, the FCN model's average CSI for the three types of severe convective weather was 33.3%, with an average POD of 73.4% and an average FAR of 62.1%. Among these, STHR had the highest POD and CSI, accompanied by the lowest FAR values. On the other hand, CG and hail had similar CSI and FAR scores, but CG had a higher POD than hail.

- (2)

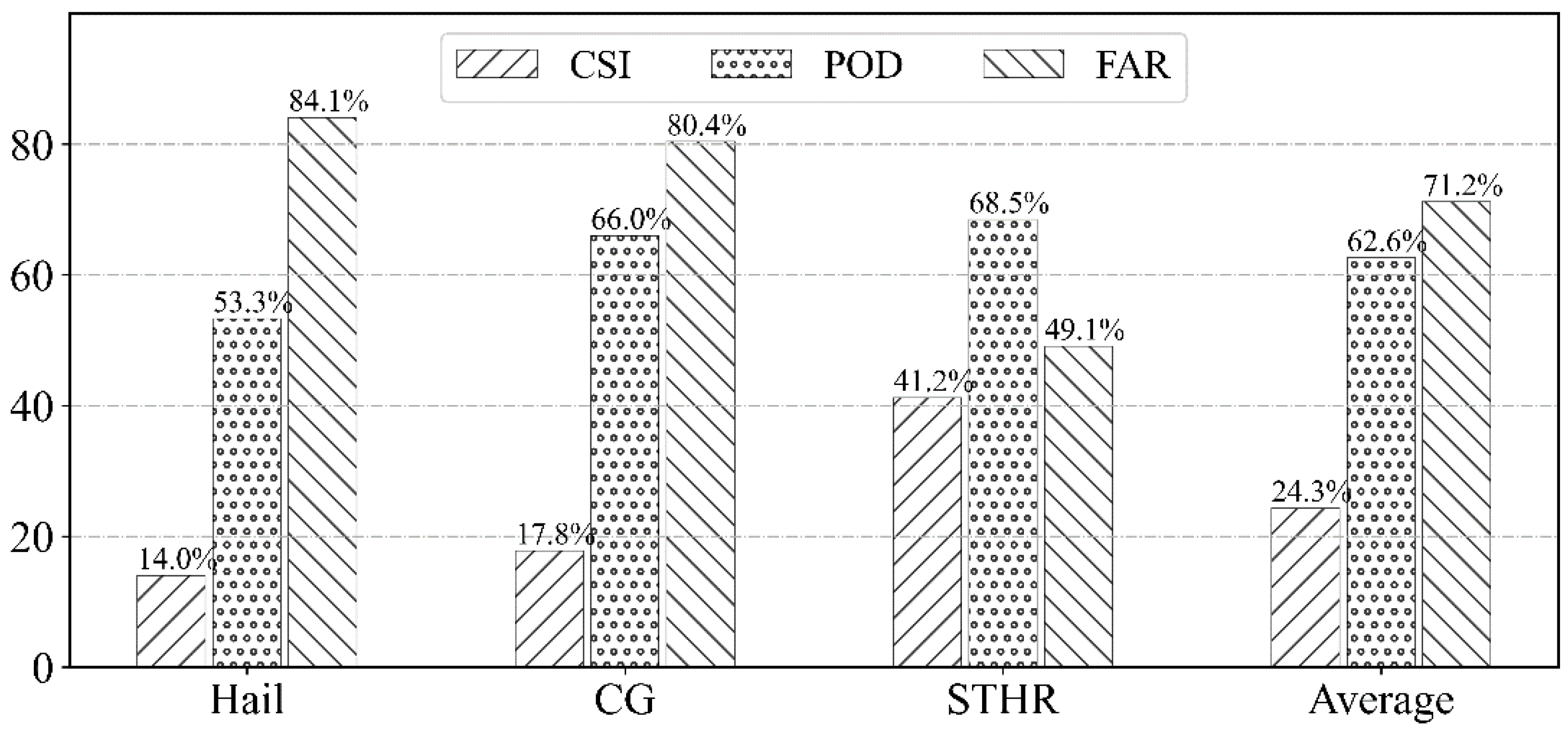

- The FCN model was tested using ground observation data of severe convective weather from 2022, indicating an overall misjudgment rate of 18.6% for the three types of severe convective weather as well as non-severe convective weather. The misjudgment rates for hail, CG, and STHR were 48.2%, 29.0%, and 27.2%, respectively. The misjudgment rate is 14.5% for non-severe convective weather. The scores obtained from the test set were lower than those in the training set, with an average CSI of 25.8%, an average POD of 65.2%, and an average FAR of 70.0%. Nevertheless, STHR still showed the best in terms of forecast performance.

- (3)

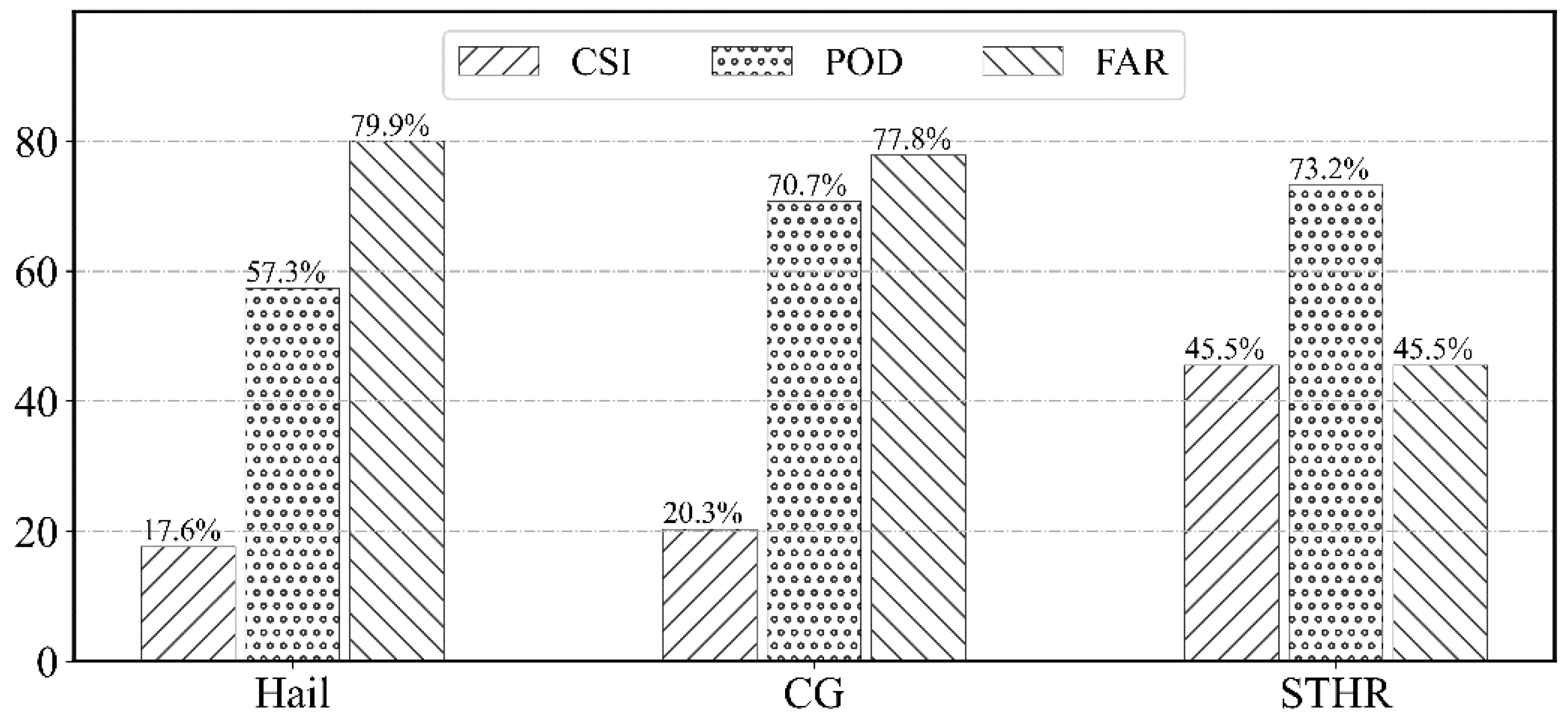

- After operationalizing the FCN model, independent validation using ground observation data of severe convective weather from 2023 demonstrated an overall misjudgment rate of 18.3%. The misjudgment rates for hail, CG, and STHR were 46.7%, 34.0%, and 31.5%, respectively, with a rate of 13.3% for non-severe convective weather. The average CSI was 24.3%, the average POD remained at 62.6%, and the average FAR was 71.2%, with STHR continuing to have the best forecast performance. The performance of the independent validation set was slightly lower than the training period cross-validation set and the test set, , indicating that despite a slight performance decline in operational implementation, the model still demonstrates a degree of accuracy and stability in classifying severe convective weather.

- (4)

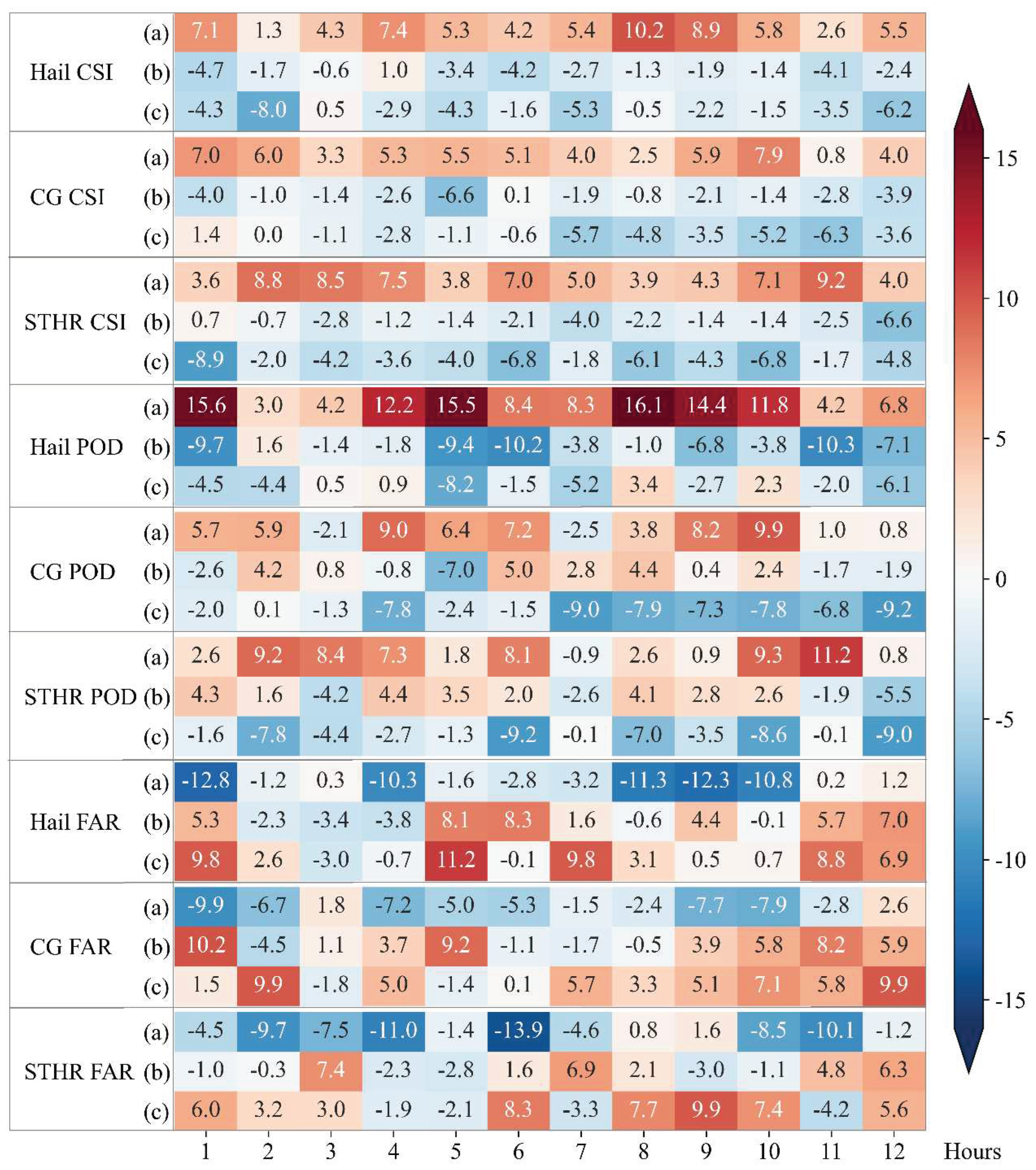

- The hourly analysis illustrated that the fluctuations in the CSI, POD, and FAR metrics across different time intervals. In a comprehensive assessment, it was found that the FCN model exhibited optimal performance in hail classification analysis during the fourth, eighth, and tenth hours. As for CG, its peak performance was observed at the sixth hour, whereas STHR demonstrated the best accurate performance during the second and fourth hours., Conversely, the least favorable performance was witnessed across all three categories of severe convective weather at the twelfth hour. Across the entire 2017-2023 sample, hail had a CSI of 17.6%, CG of 20.3%, and STHR of 45.5%. The best POD for STHR was 73.2%, followed by CG, with hail being the lowest at 57.3%. The FAR for hail and CG was comparable, with STHR having the lowest score, which was 45.5%. Thus, the FCN can be treated as a reliable short-term forecasting model, which can provide an accurate classification forecast for severe convective weather

References

- Liu Xinwei, Jiang Yingsha, Huang Wubin, et al, 2021. Classified Identification and Nowcast of Hail Weather Based on Radar Products and Random Forest Algorithm[J]. Plateau Meteorology, 40(4):898-908. [CrossRef]

- Liu Xinwei, Huang Wubin, Jiang Yingsha, et al, 2021. Study of the Classified Identification of the Strong Convective Weathers Based on the LightGBM Algorithm[J]. Plateau Meteorology, 40(4):909-918. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Kanghui, Zheng Yongguang, Li Bo, et al., 2019. Forecasting Different Types of Convective Weather: A Deep Learning Approach[J]. J. Meteor. Res., 33(5), 797–809. [CrossRef]

- Stensrud David J., Xue Ming, Wicker Louis J. , et al., 2009. Convective-Scale Warn-on-Forecast System: A Vision for 2020[J]. Bull. Amer.Meteor. Soc., 90, 1487–1500. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Yongguang, Zhou Kanghu, Sheng Jie, et al., 2015.Advanc es in Techniques of Monitoring, Forecasting and Warning of Severe Convective Weather[J].Journal Of Applied Meteorological Science, 26(6):641-657. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Kanghui, Zheng Yongguang, Han Lei, et al, 2021.Advances in Application of Machine Learning to Severe Convective Weather Monitoring and Forecasting[J]. Meteor Mon,47(3) :274-289(in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Sun Jisong, Dai Jianhua, He Lifeng, et al. 2014. Fundamental Principles and Technical Methods for Severe Convective Weather Forecasting: Manual for Severe Convective Weather Forecasting in China [M]. Beijing: China Meteorological Press, p. 282.

- Yu Xiaoding, Wang Xiuming, Li Wanli, et al. 2020. Thunderstorm and Severe Convective Nowcasting [M]. Beijing: China Meteorological Press, p. 416.

- Yu Xiaoding, Zhou Xiaogang, Wang Xiuming.2012.The Advances in the Nowcasting Techniques on Thunderstorms and Severe Convection[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 70(3):311-337.

- Guo Hanyang, Chen Mingxuan, Han Lei, et al, 2019.High Resolution Nowcasting Experiment of Severe Convections Based on Deep Learning[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 77(4):715-727. [CrossRef]

- Yu Xiaoding, Zheng Yongguang. 2020. Advances in Severe Convective Weather Research and Operational Service in China[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 78(3):391-418. [CrossRef]

- Miller Robert C.. 1972. Notes on Analysis and Severe Storm Forecasting Procedures of the Air Force Global Weather Central. Technical Report 200(Rev)[M]. Omaha: Air Weather Service, 181pp.

- Mcnulty Richard P.. 1995. Severe and Convective Weather:A Central Region Forecasting Challenge[J]. Wea Forecasting, 10(2):187-202. [CrossRef]

- Doswell Charles A., Brooks H E, Maddox R A. 1996. Flash Flood Forecasting:An Ingredients-Based Methodology[J]. Wea Forecasting, 11(4):560-581. [CrossRef]

- Moller Alan R.. 2001. Severe local storms forecasting//Doswell III C A. Severe Convective Storms[J]. Boston, MA:American Meteorological Society, 433-480. [CrossRef]

- Huang Wubin, Zhao Yang, Sun Chan, et al, 2020.Climate modulation of summer rainstorm activity in eastern China based on the Tibetan Plateau spring heating[J].Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 13(3). 1007. [CrossRef]

- Qian Zhuolei, Lou Xiaofen, Shen Xiaoling, et al, 2023.Research on Classified Severe Convection Weather Forecastin Zhejiang Province Based on Extreme Forecast Index of Ensemble Prediction[J].Meteorological Science and Technology, 51(04):582-594. [CrossRef]

- Wang Guo’an, Qiao Chungui, Zhang Yiping, et al, 2023.Statistical Characteristics of Thunderstorm Gale and Hail Severe Convection in Henan Under the Background of Cold Vortex[J].Meteorological and Environmental Sciences, 46(4): 27–37. [CrossRef]

- Tan Dan, Huang Yuxia, Sha Hong'e.Characteristic Analysis of Severe Convective Weather in Gansu Province[J].Journal of Natural Disasters, 31(02):222-232. [CrossRef]

- Mao Chengyan, Zheng Qian, Gong Liqing, et al, 2021. Diagnosis and Forecast Method of Severe Convection Under Different Synoptic Situations in the West-Central of Zhejiang[J].Journal of the Meteorological Sciences, 41(5): 687–695. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Yan, Zhai Danhua, Wu Zhipeng, et al, 2021.A Methodof Short-Duration Heavy Rain Forecast Based on Xgboost Algorithm[J].Meteorological Science And Technology, 49(3):406-418. [CrossRef]

- Li Boyong, Hu Zhiqun, Zheng Jiafeng,et al, 2021. Using Bayesian Method to Improve Hail Identification in South CHINA[J]. Journal of Tropical Metrorology, 37(1): 112-125. [CrossRef]

- Han Feng, Yang Lu, Zhou Chuxuan, et al, 2021.An Experimental Study of the Short- time Heavy Rainfall Event Forecast Based on Ensemble Learning and Sounding Data[J].Journal of Applied Meteorological Science, 32(2):188-199, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Hualong, Wu Zhifang, Xiao Liusi, et al, 2020. A Probabilistic Forecast Model of Short-time Heavy Rainfall in Guangdong Province Based on Factor Analysis and its operational experiments[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 79(1):15-30. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Tian, Yang Zhao, Seok-Woo Son, Jing-Jia Luo, Seok-Geun Oh, Yinjun Wang, 2023:A Deep-Learning Ensemble Method to Detect Atmospheric Rivers and Its Application to Projected Changes in Precipitation Regime. [CrossRef]

- Chen Jinpeng, Feng Yerong, Meng Weiguang, et al, 2021.Acorrection Method of Hourly Precipitation Forecast Based on Convolutional Neural Network[J] .Meteor Mon, 47(1):60-70. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Kanghui, Zheng Yongguang, Wang Tingbo. 2021. Very Short-range Lightning Forecasting With NWP and Observation Data: A Deep Learning Approach[J]. Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 79(1):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Yuchen, Long Mingsheng, Chen Kaiyuan, et al.2023.Skilful Nowcasting of Extreme Precipitation With NowcastNet[J]. Nature, 619(7970):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Yann LeCun , Bengio Yoshua, Hinton Geoffrey. 2015.Deep learning[J]. nature 521(7553): 436-444. [CrossRef]

- Maryam M Najafabadi, Flavio Villanustre, Taghi M Khoshgoftaar, et al. 2015. Deep Learning Applications and Challenges in Big Data Analytics[J]. Journal of Big Data, 2(1): 1-21. [CrossRef]

- ZhangXiaodong, Wang Tong, Chen Guanzhou, et al.2019. Convective Clouds Extraction From Himawari–8 Satellite Images Based on Double-stream Fully Convolutional Networks[J]. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 17(4): 553-557. [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer Evan, J.Long, T.Darrell. 2015. Fully Convolutional Networksfor Semantic Segmentation[C]J//Proceedings of the /IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 3431-3440. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Hengshuang, Shi Jianping, Qi Xiaojuan, et al.2017.Pyramid scene Parsing Network[C]V/Proceedings of the lEEE conference on computervision and pattern recognition.2881-2890. [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan Vijay, A. Kendall, R. Cipolla. 2017. Segnet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation[J]. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 39(12): 2481-2495. [CrossRef]

- Romero Adriana, C. Gatta, G. Camps-Vall. 2016 .Unsupervised Deep Feature Extraction for Remote Sensing Image Classification[J].IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 54(3), 1349–1362. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Kanghui, Zheng Yongguang, Dong Wansheng, et al. 2020. A Deep Learning Network for Cloud-to-Ground Lightning Nowcasting with Multisource Data [J]. J Atmos Oceanic Technol, 37(5):927-942. [CrossRef]

- Li Mengya, Shi Xiaomeng, Wu Xiaojing, et al.2023.Detection of Nighttime Sea Fog / Low Stratus Over Western North Pacific Based on Geostationary Satellite Data Using Convolutional Neural Networks[ J]. Journal of Marine Meteorology, 43( 1):1⁃11. (in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Zhang Xin, Yao Qing’an, Zhao Jian, et al.2020.Image Semantic Segmentation Based on Fully Convolutional Neural Network[J] .Computer Engineering and Applications, 58(08):45-57. [CrossRef]

- Maggiori E, Tarabalka Y, Charpiat G, et al. 2016. Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Remote Sensing Image Classification[C]//2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS). IEEE, 5071-5074. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Hualong, Wu Zhifang, Xiao Liusi, et al.2021.A Probabilistic Forecast Model of Short-time Heavy Rainfall in Guangdong Province Based on Factor Analysis and its Operational Experiments[J].Acta Meteorologica Sinica, 79(1):15-30. [CrossRef]

- Lü Xiaona, Niu Shuzhen, Zhang Yiping, et al.2020.Research on Objective Forecast Method of Thunderstorm Potential Based on Probability and Weight [J].Torrential Rain and Disasters, 39(1):20-29. [CrossRef]

- Mo Lixia, Gao Xianquan, Ou Huining, et al., 2020. Study of Objective Forecast Method of Guangxi Hail Based on Numerical Model Product[J]. Journal of Arid Meteorology, 38(3):480-489. [CrossRef]

- Huang Yuxia, Wang Baojian, Wang Yong, et al. 2017. Mesoscale Analysis Operational Technical Specifications for Severe Convective Weather in Gansu Province [M]. Beijing: China Meteorological Press, pp. 20-47.

- Liu Na, Wang Yong, Duan Bolong, et al., 2023. The Objective Forecast of Hourly Gird Temperature Based on LPSC Algorithm and its’ Evaluation[J]. Transactions of Atmospheric Sciences, 1-12.

| Factors | PVORT | TMP | HGT | DIV | UV | Q | W | SPFH | CAPE | PW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level (hPa) |

200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | |||||

| 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | |||

| 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | |||

| surface | surface | all layers |

| Non-SCW | Hail | CG | STHR | |

| Training set | 167108 | 1125 | 11972 | 5890 |

| Testing set | 51024 | 168 | 2258 | 1667 |

| Validation set | 51614 | 167 | 2331 | 1169 |

| Label value | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Obs. | Classification of the FCN model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hail | CG | STHR | Non-SCW | FIR | Overall FIR | |

| Hail | 150 | 46 | 16 | 13 | 33.2% | 16.6% |

| CG | 36 | 1798 | 320 | 241 | 24.9% | |

| STHR | 22 | 194 | 921 | 41 | 21.8% | |

| Non-SCW | 366 | 4619 | 262 | 28174 | 15.7% | |

| Obs. | Classification of FCN model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hail | CG | STHR | Non-SCW | FIR | Overall FIR | |

| Hail | 87 | 44 | 18 | 19 | 48.2% | 18.6% |

| CG | 67 | 1603 | 128 | 460 | 29.0% | |

| STHR | 44 | 281 | 1214 | 128 | 27.2% | |

| Non-SCW | 281 | 6117 | 980 | 43646 | 14.5% | |

| Obs. | Classification of FCN model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hail | CG | STHR | Non-SCW | FIR | Overall FIR | |

| Hail | 89 | 58 | 12 | 8 | 46.7% | 18.3% |

| CG | 58 | 1539 | 340 | 394 | 34.0% | |

| STHR | 23 | 222 | 801 | 123 | 31.5% | |

| Non-SCW | 388 | 6053 | 421 | 44752 | 13.3% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).