Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

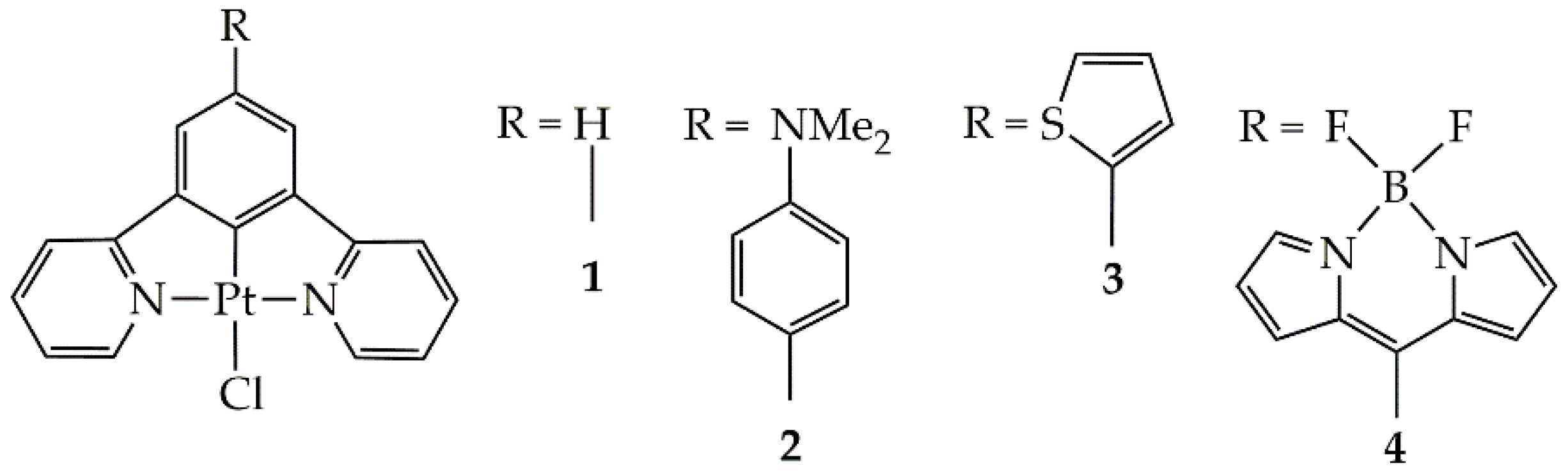

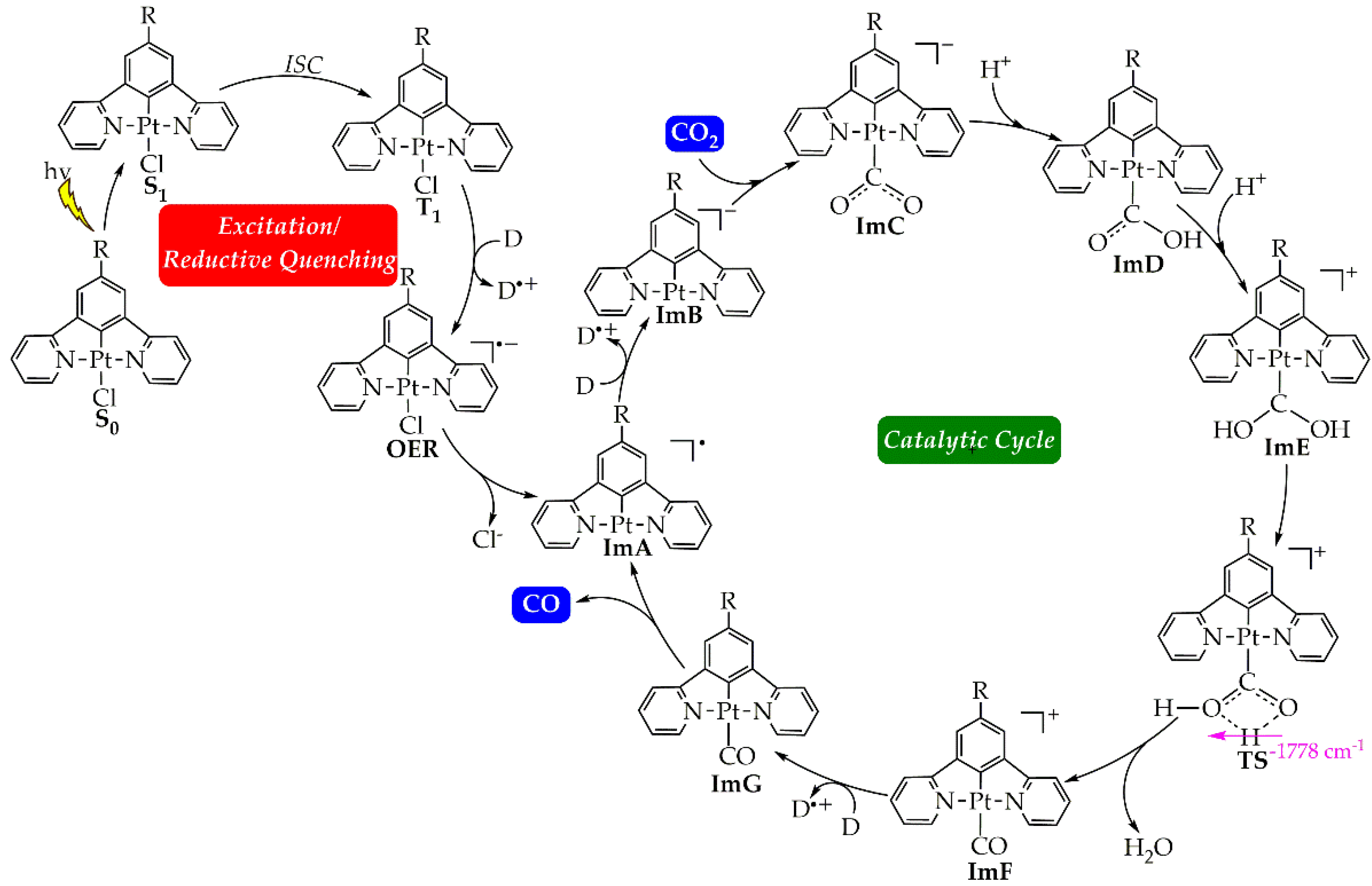

2. Results and Discussion

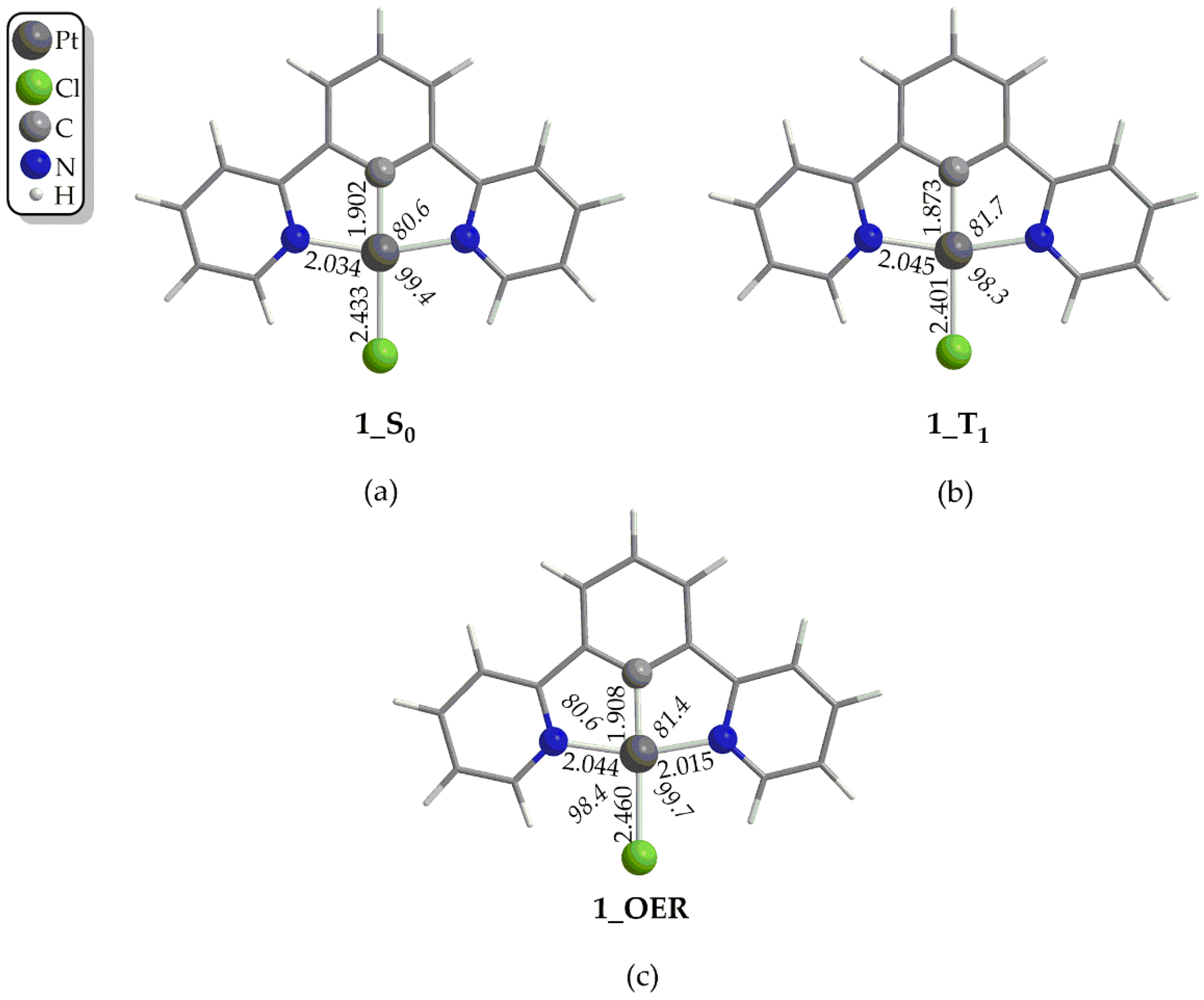

2.1. Photoexcitation/Reductive Quenching step

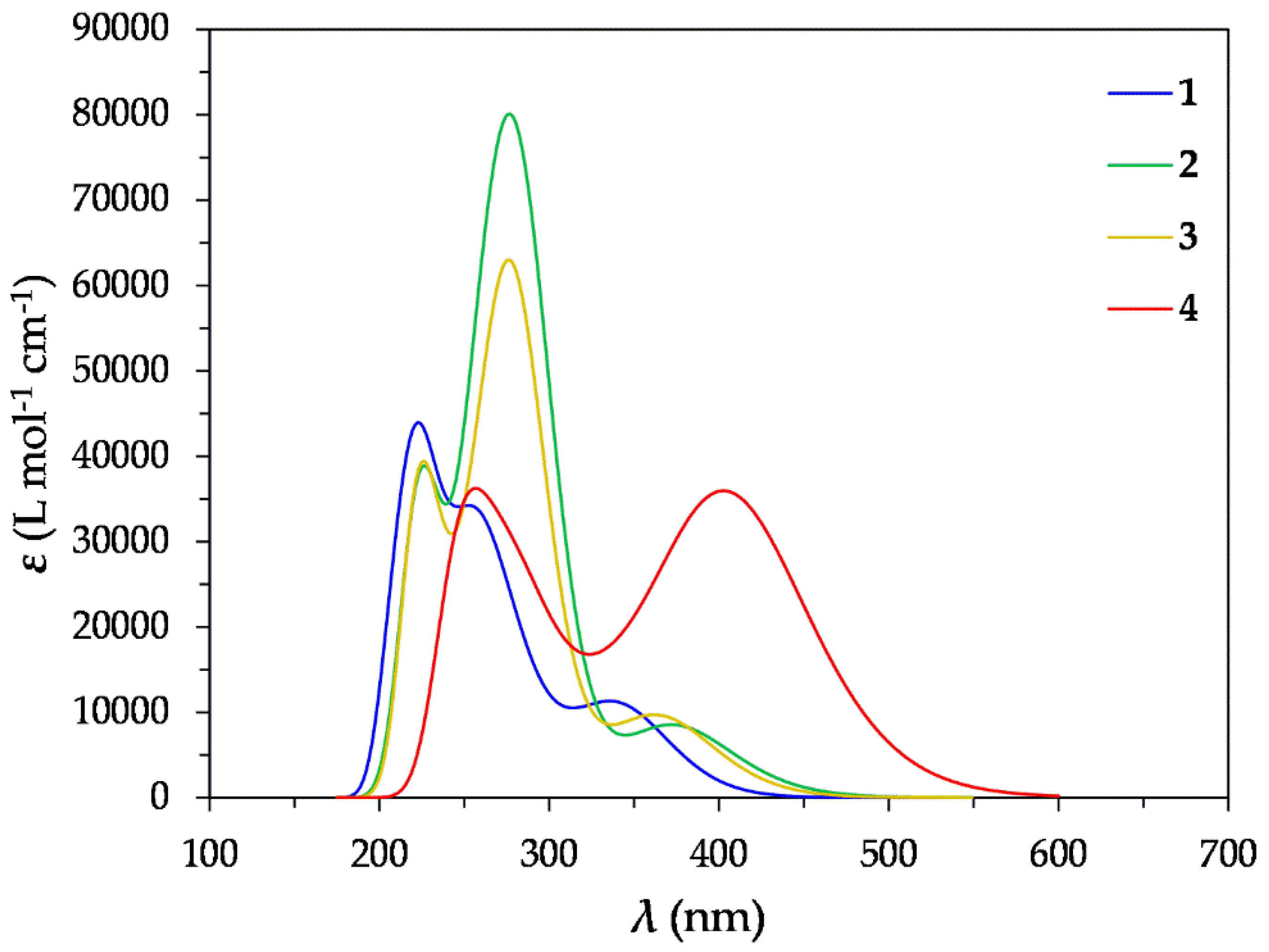

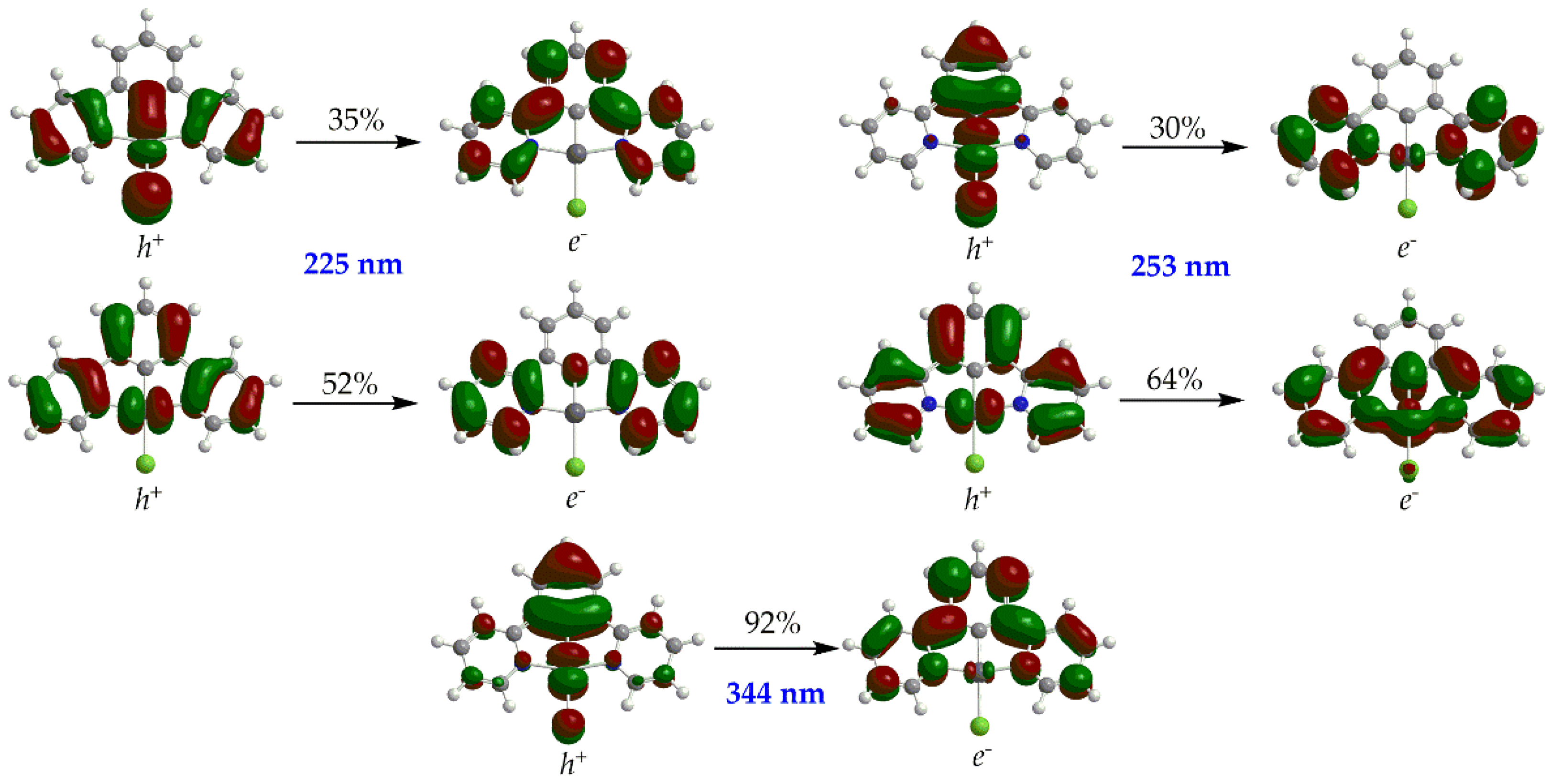

2.1.1. Absorption Spectra

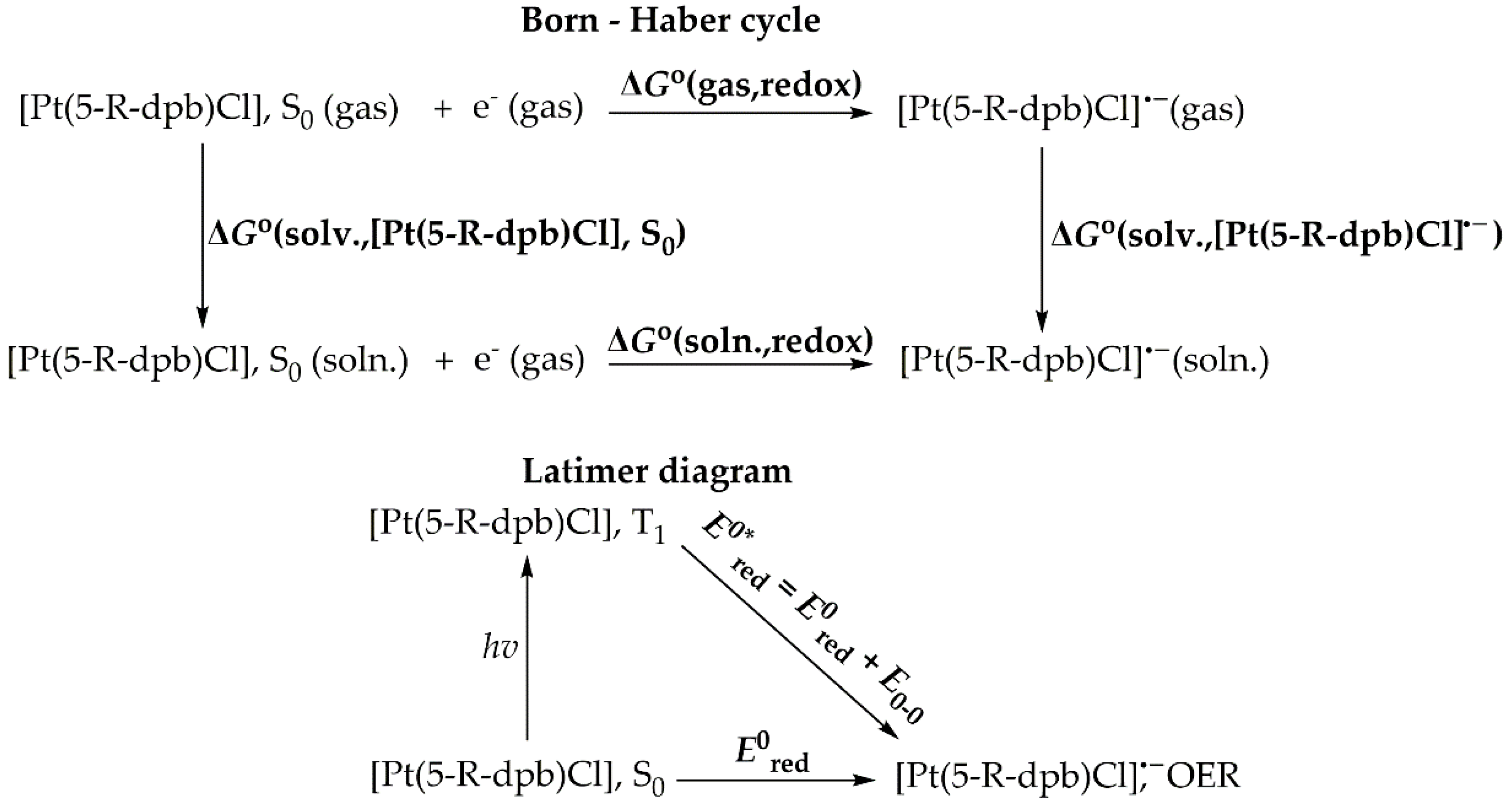

2.1.2. Excited State Electrochemistry

2.2. Catalytic Cycle Step

2.2.1. The η1-CO2 complex

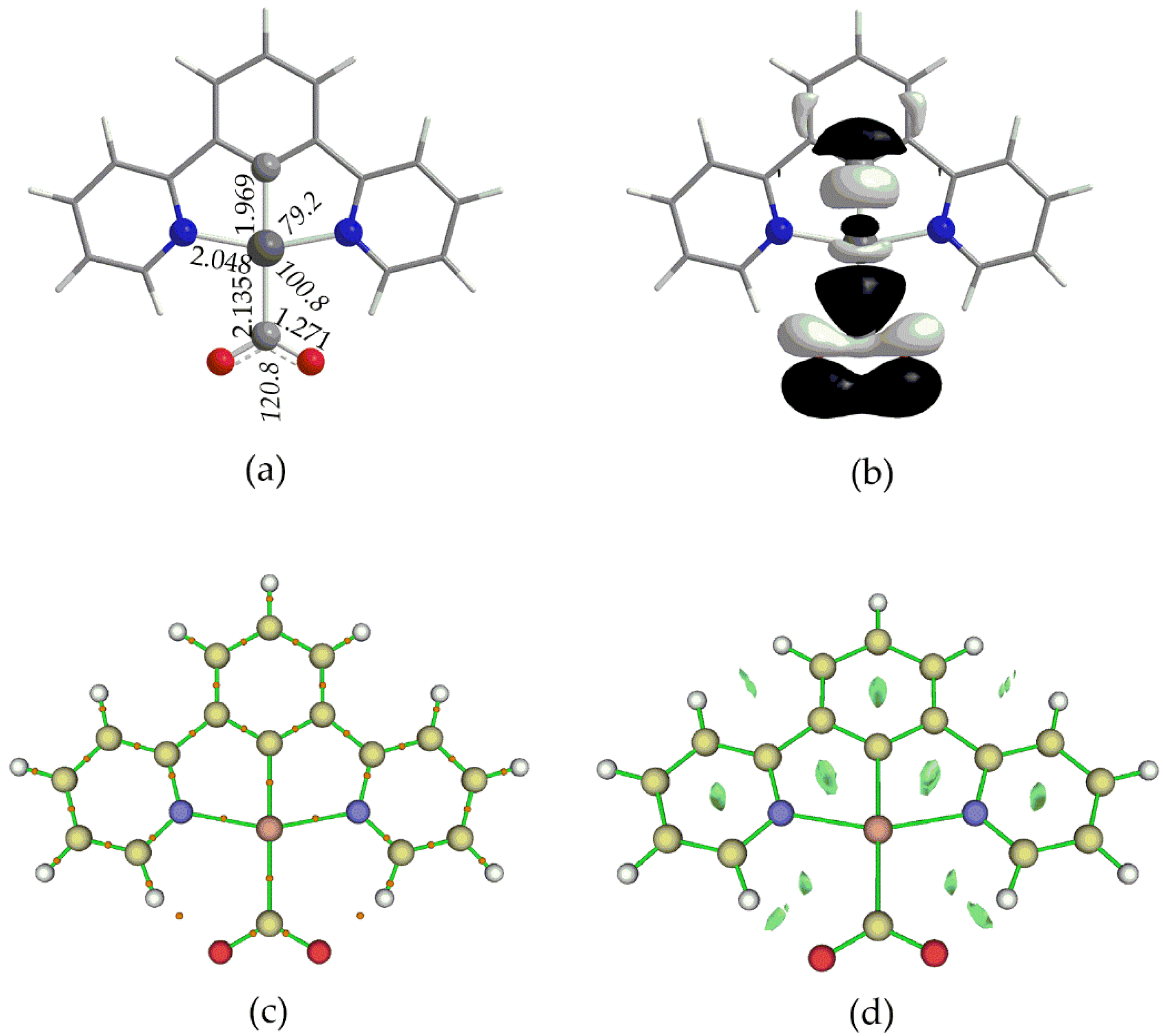

Structural Properties

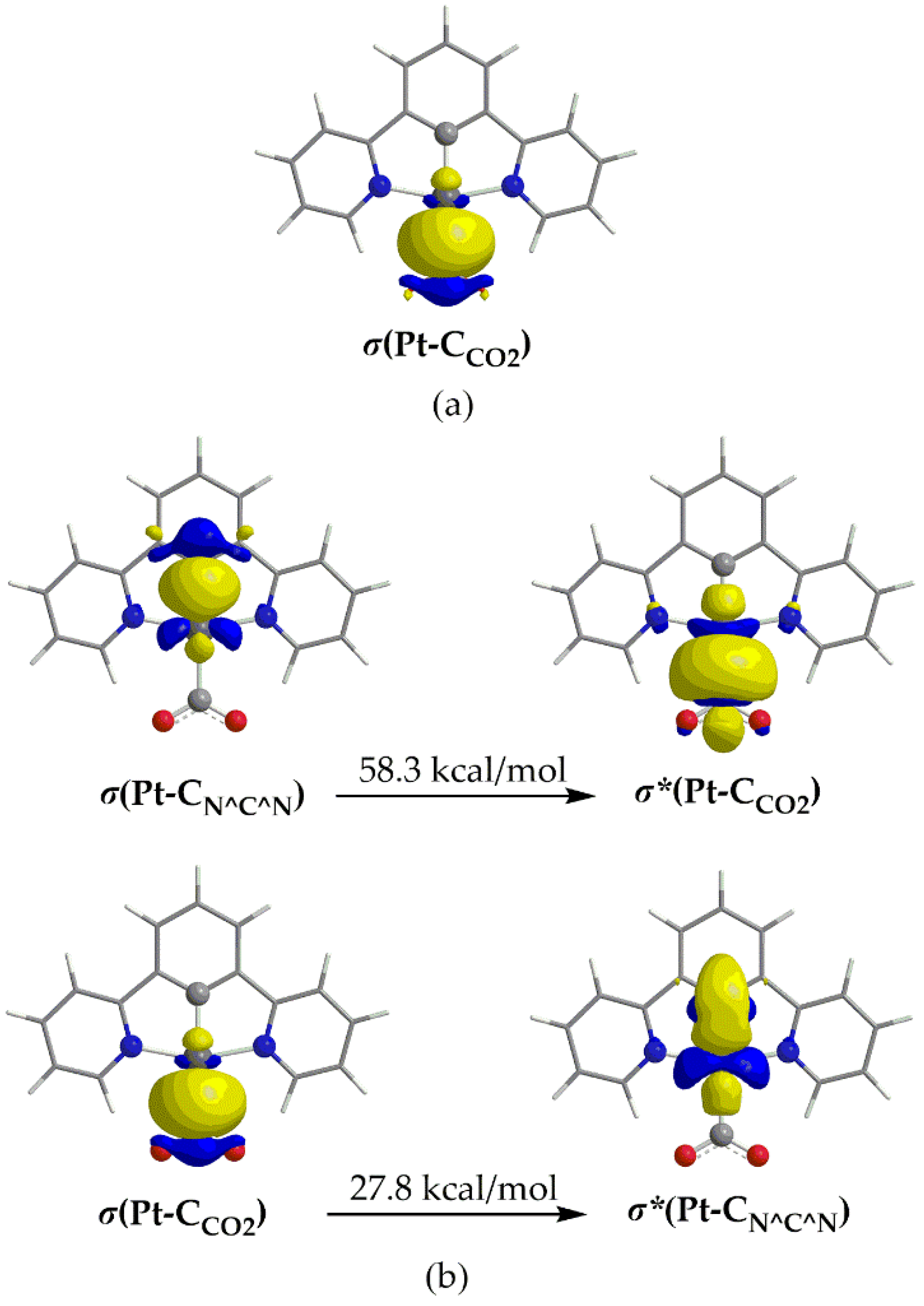

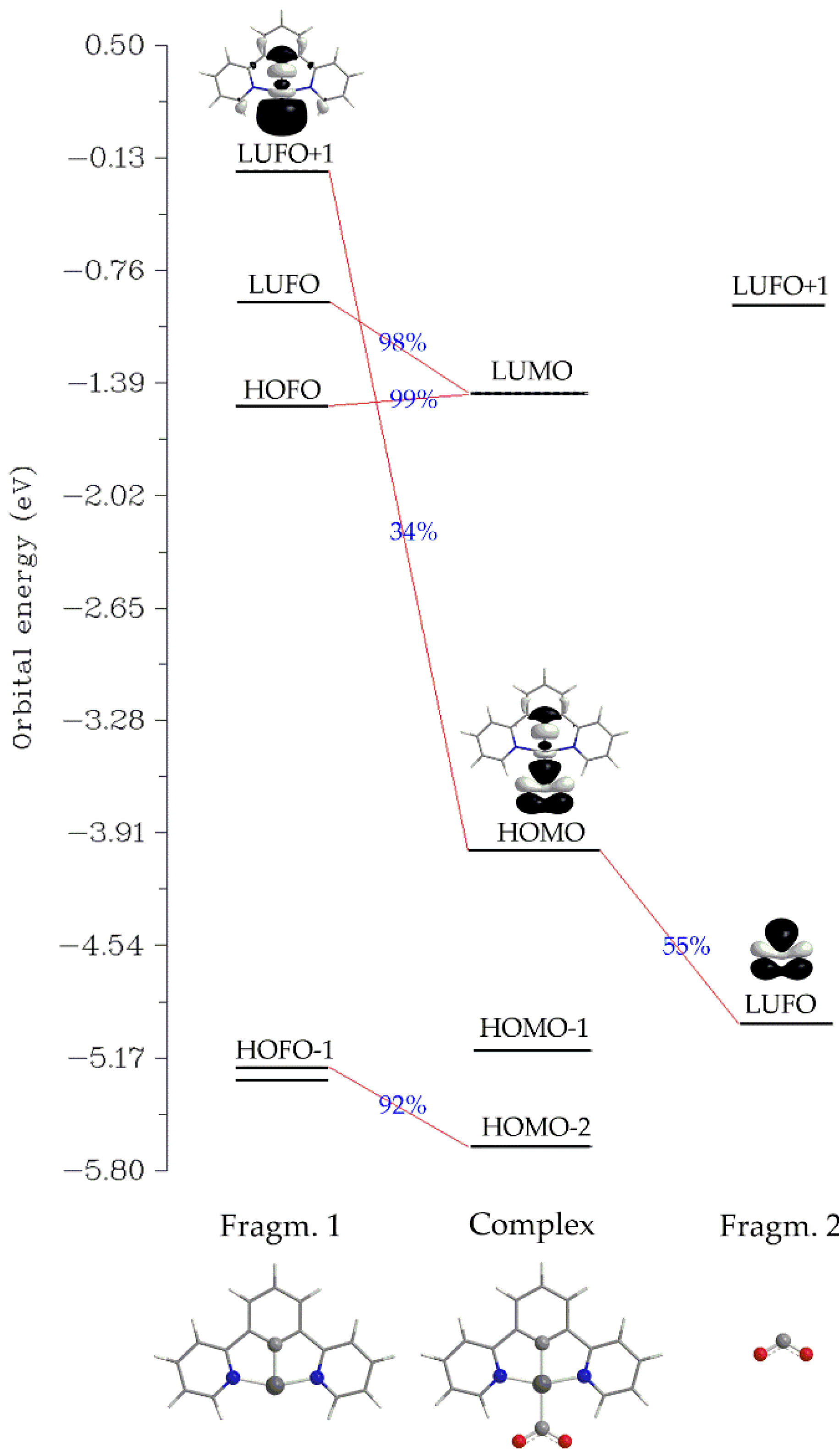

Bonding and Electronic Properties

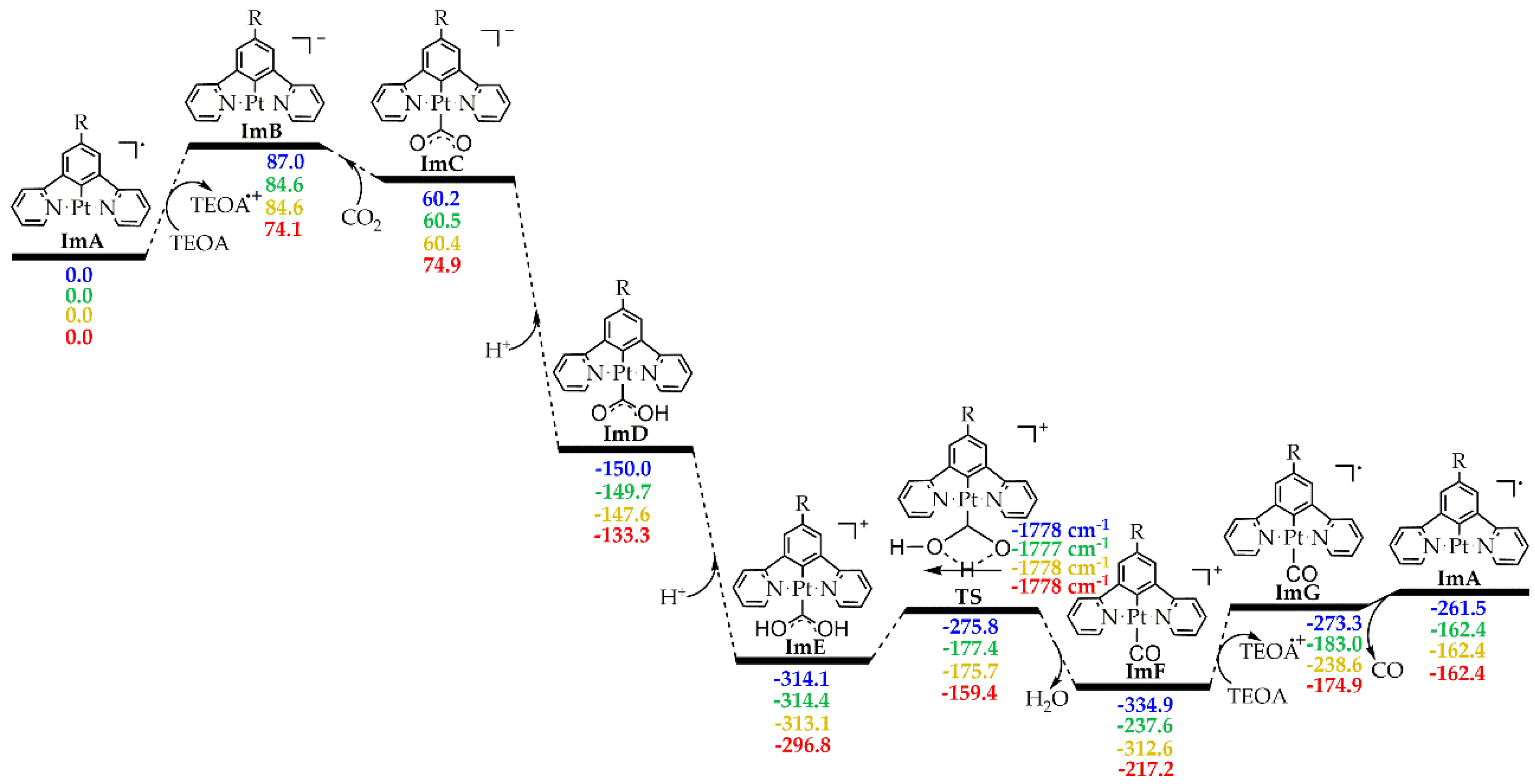

2.2.2. Energetic Reaction Profiles

3. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lahijani, P.; Zainal, Z. A.; Mohammadi M.; Mohamed, A. R. Conversion of the greenhouse gas CO2 to the fuel gas CO via the Boudouard reaction: A review Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.08.034. [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, Y.; Ishitani, O.; Ishida, H. Reaction mechanisms of catalytic photochemical CO2 reduction using Re(I) and Ru(II) complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 373, 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2017.11.023. [CrossRef]

- Cokoja, M.; Bruckmeier, C.; Rieger, B.; Herrmann, W. A.; Kühn, F. E. Transformation of carbon dioxide with homogeneous transition-metal catalysts: A molecular solution to a global challenge? Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8510–8537. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201102010. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. J.; Meyer, G. J.; Fujita, E. Molecular approaches to the photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide for solar fuels. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1983–1994. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar9001679. [CrossRef]

- Benson, E. E.; Kubiak, C. P.; Sathrum, A. J.; Smieja, J. M. Electrocatalytic and homogeneous approaches to conversion of CO2 to liquid fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1039/b804323j. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, H.; Koike, K.; Morimoto, T.; Inumaru, H.; Ishitani, O. Photochemistry and photocatalysis of rhenium(I) diimine complexes, Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 63, 137-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385904-4.00007-X. [CrossRef]

- Costentin, C.; Robert M.; Savéant, J. M. Catalysis of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 2423–2436. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cs35360a. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Wan Daud, W. M. A. Photocatalytic CO2 transformation into fuel: A review on advances in photocatalyst and photoreactor. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 765–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.046. [CrossRef]

- Vandezande, J. E.; Schaefer, H. F. CO2 Reduction Pathways on MnBr(N-C)(CO)3 Electrocatalysts. Organometallics 2018, 37, 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00743. [CrossRef]

- Paquin, F.; Rivnay, J.; Salleo, A.; Stingelin, N.; Silva, C. Multi-phase semicrystalline microstructures drive exciton dissociation in neat plastic semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2015, 3, 10715–10722. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1310.8002. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Qian, L.; Al-Enizi, A. M.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, G. Heterogeneous Electrocatalysts for CO2 Reduction. Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 1034−1044. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.0c02648. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Peng, B.; Peng, T. Recent Advances in Heterogeneous Photocatalytic CO2 Conversion to Solar Fuels. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7485−7527. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.6b02089. [CrossRef]

- Ishida H., Electrochemical/Photochemical CO2 Reduction Catalyzed by Transition Metal Complexes. In Carbon Dioxide Chemistry, Capture and Oil Recovery. Iyad, K., Shaya, J., Srour, H., Eds.; InTechOpen Ltd. London, UK, 2018; pp. 17 – 40.

- Lehn, J.-M.; Ziessel, R. Photochemical generation of carbon monoxide and hydrogen by reduction of carbon dioxide and water under visible light irradiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1982, 79, 701–704. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.79.2.701. [CrossRef]

- Hawecker, J.; Lehn, J.-M.; Ziessel, R. Efficient photochemical reduction of CO2 to CO by visible light irradiation of systems containing Re(bipy)(CO)3X or Ru(bipy)32+–Co2+ combinations as homogeneous catalysts. Chem. Commun., 1983, 536–538. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39830000536. [CrossRef]

- Hawecker, J.; Lehn, J.-M.; Ziessel, R. Photochemical and Electrochemical Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Carbon Monoxide Mediated by (2,2′-Bipyridine)tricarbonylchlororhenium(I) and Related Complexes as Homogeneous Catalysts. Helv. Chim. Acta 1986, 69, 1990–2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/hlca.19860690824. [CrossRef]

- Elgrishi, N.; Chambers, M. B.; Wang, X.; Fontecave, M. Molecular polypyridine-based metal complexes as catalysts for the reduction of CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 761-796. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5cs00391a. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Takeda, H.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 using metal complexes. J. Photochem. & Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2015, 25, 106–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2015.09.001. [CrossRef]

- Voyame, P.; Toghill, K. E.; Méndez, M. A.; Girault, H.H. Photoreduction of CO2 Using [Ru(bpy)2(CO)L]n+ Catalysts in Biphasic Solution/Supercritical CO2 Systems. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10949–10957. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic401031j. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Nakajima, T.; Sawa, S.; Nakanishi, R.; Imori, D.; Ishitani, O. CO2 Capture by a Rhenium(I) Complex with the Aid of Triethanolamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16825−16828. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja409271s. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, Y.; Morimoto, T.; Koike, K.; Ishitani, O. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction with high turnover frequency and selectivity of formic acid formation using Ru(II) multinuclear complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 15673–15678. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118336109. [CrossRef]

- Tsipis,A. C.; Sarantou, A. A. Dalton Trans. DFT insights into the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO by Re(I) complexes: the crucial role of the triethanolamine “magic” sacrificial electron donor. 2021, 50, 14797–14809. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1dt02188e. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Kita, S.; Brunschwig, B. S.; Fujita E. Involvement of a Binuclear Species with the Re-C(O)O-Re Moiety in CO2Reduction Catalyzed by Tricarbonyl Rhenium(I)Complexes with Diimine Ligands: Strikingly Slow Formation of the Re-Re and Re-C(O)O-Re Species from Re(dmb)(CO)3S (dmb = 4,4’-Dimethyl-2,2’-bipyridine, S = Solvent). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11976-11987. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja035960a. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B. P.; Bolinger, C. M.; Conrad, D.; Vining, W. J.; Meyer, T. J. One- and Two-electron Pathways in the Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 by fac-Re(bpy)(CO)3Cl (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridine). J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985, 1414–1416. https://doi.org/10.1039/C39850001414. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.; Fujita, E.; Schaefer, III, H. F.; Muckerman, J. T. Mechanisms for CO Production from CO2 Using Reduced Rhenium Tricarbonyl Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5180-5186. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja2105834. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos B. M.; Yang, J. Y. Directing the reactivity of metal hydrides for selective CO2 reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 12686–12691. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811396115. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. H.; Han, W. D.; Hong Y. J.; Yu, J. G. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on Pt-loaded TiO2 catalyst. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2009.07.081. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; An, W.; Ramalingam, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Niedzwiedzki, D. M.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Biswas, P. Size and Structure Matter: Enhanced CO2 Photoreduction Efficiency by Size-Resolved Ultrafine Pt Nanoparticles on TiO2 Single Crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11276−11281. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja304075b. [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, K. I.; Sakai, K.; Ikeda, K.; Carja, G.; Matsushita, N.; Okada, K. Preparation and photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on noble metal (Pt, Pd, Au) loaded Zn-Cr layered double hydroxides. Mater. Lett. 2013, 107, 138–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2013.05.132. [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, W.; Denga, W.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O: Significant enhancement of the activity of Pt–TiO2 in CH4 formation by addition of MgO. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2451–2453. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CC00107E. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Lei, Z.; Kuang, C. C.; Chen, X.; Gong, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Wu, J. C. S. Selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 into CH4 over Pt-Cu2O TiO2 nanocrystals: The interaction between Pt and Cu2O cocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Kočí, K.; Dang Van, H.; Edelmannová, M.; Reli, M.; Wu, J. C. S. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 using Pt/C3N4 photocatalyts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 503, 144426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144426. [CrossRef]

- Tasbihi, M.; Kočí, K.; Edelmannová, M.; Troppová, I.; Reli, M.; Schomäcker, R. Pt/TiO2 photocatalysts deposited on commercial support for photocatalytic reduction of CO2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 366, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.04.012. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, L.; Liu, L.; Xu, M. Platinum Nanoparticles with Low Content and High Dispersion over Exfoliated Layered Double Hydroxide for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Energy and Fuels 2021, 35, 10820–10831. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00820. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. A. G.; Beeby, A.; Davies, S.; Weinstein, J. A.; Wilson, C. An Alternative Route to Highly Luminescent Platinum(II) Complexes: Cyclometalation with N^C^N-Coordinating Dipyridylbenzene Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 8609–8611. https://doi.org/10.1021/ic035083+. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, D. J.; Echavarren, A. M.; Ramírez de Arellano, M. C. Divergent Behavior of Palladium(II) and Platinum(II) in the Metalation of 1,3-Di(2-pyridyl)benzene. Organometallics 1999, 18, 3337–3341. https://doi.org/10.1021/om990125g. [CrossRef]

- Demissie, T. B.; Ruud, K.; Hansen, J. H. DFT as a Powerful Predictive Tool in Photoredox Catalysis: Redox Potentials and Mechanistic Analysis. Organometallics, 2015, 34, 4218–4228. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00582. [CrossRef]

- Nandal, N.; Jain, S. L. A review on progress and perspective of molecular catalysis in photoelectrochemical reduction of CO2. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 451, 214271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214271. [CrossRef]

- Grice, K. A. Carbon dioxide reduction with homogenous early transition metal complexes: Opportunities and challenges for developing CO2 catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 336, 78-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2017.01.007. [CrossRef]

- Kinzel, N. W.; Werl, C.; Leitner, W. Transition Metal Complexes as Catalysts for the Electroconversion of CO2: An Organometallic Perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11628–11686. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202006988. [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. F. W. Atoms in molecules—a quantum theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Bader, R. F. W. A Bond Path: A Universal Indicator of Bonded Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 7314–7323. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp981794v. [CrossRef]

- Macchi, P.; Sironi, A. Chemical bonding in transition metal carbonyl clusters: complementary analysis of theoretical and experimental electron densities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 383, 238–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00252-7. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, E; Alkorta, I; Elguero, J; Molins, E. From weak to strong interactions: A comprehensive analysis of the topological and energetic properties of the electron density distribution involving X–H⋯F–Y systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 5529−5542. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1501133. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E. R.; Shahar Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A. J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498−6506. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja100936w. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Moss, J. R. Recent developments in the activation of carbon dioxide by metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 181, 27-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-8545(98)00171-4. [CrossRef]

- Reed, A. E.; Curtiss, L. A.; F. Weinhold, F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899-926. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00088a005. [CrossRef]

- Dapprich, S.; Frenking, G. Investigation of Donor-Acceptor Interactions: A Charge Decomposition Analysis Using Fragment Molecular Orbitals. J. Phys. Chem.1995, 99, 9352-9362. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100023a009. [CrossRef]

- Vetere, V.; Adamo, C.; Maldivi, P. Performance of the `parameter free' PBE0 functional for the modeling of molecular properties of heavy metals. Chem. Phys. Lett., 2000, 325, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2614(00)00657-6. [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Inexpensive and accurate predictions of optical excitations in transition-metal complexes: the TDDFT/PBE0 route. Theor. Chem. Acc., 2000, 105, 169–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002140000202. [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys., 1999, 110, 6158–6170. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.478522. [CrossRef]

- Ernzerhof, M.; Scuseria, G. E. Assessment of the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional. J. Chem. Phys., 1999, 110, 5029–5036. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.478401. [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Scuseria, G. E.; Barone, V. Accurate excitation energies from time-dependent density functional theory: Assessing the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys., 1999, 111, 2889–2899. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.479571. [CrossRef]

- Adamo, C.; Barone, V. Toward reliable adiabatic connection models free from adjustable parameters. Chem. Phys. Lett., 1997, 274, 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2614(97)00651-9. [CrossRef]

- Gaussian 16W, Revision C.01, Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B. G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H. P.; Ortiz, J. V.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Williams-Young, D.; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M. J.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E. N.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T. A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A. P.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory, J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21759. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Chaudret, R.; Hu, X.; Yang, W. Noncovalent Interaction Analysis in Fluctuating Environments. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 2226–2234. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct4001087. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyser. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.22885. [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr9904009. [CrossRef]

- Van Gisbergen, S. J. A.; Kootstra, F.; Schipper, P. R. T.; Gritsenko, O. V.; Snijders, J. G. Baerends, E. J. Density-functional-theory response-property calculations with accurate exchange-correlation potentials Phys. Rev. A - At. Mol. Opt. Phys., 1998, 57, 2556–2571. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.57.2556. [CrossRef]

- Jamorski, C.; Casida, M. E.; Salahub, D. R. Dynamic polarizabilities and excitation spectra from a molecular implementation of time-dependent density-functional response theory: N2 as a case study. J. Chem. Phys., 1996, 104, 5134–5147. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.471140. [CrossRef]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett., 1996, 256, 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(96)00440-x. [CrossRef]

| Complex | E0red | E0*red | E0red vs SHE | E0*red vs SHE c |

| 1 | -2.48 | 1.80 | 0.32 | 4.60 |

| 2 | -2.46 | 1.82 | -0.36 | 3.92 |

| 3 | -2.54 | 1.74 | -0.34 | 3.94 |

| 4 | -3.48 | 0.80 | -1.88 | 2.40 |

| Species | ρBCPa | ρBCPb | GBCPc | VBCPc | |VBCP|/GBCP | HBCPc | GBCP/ρBCP |

| 1_ImC | 0.124 | 0.137 | 0.089 | -0.145 | 1.629 | -0.056 | 0.718 |

| 2_ImC | 0.125 | 0.138 | 0.090 | -0.147 | 1.633 | -0.057 | 0.720 |

| 3_ImC | 0.125 | 0.135 | 0.090 | -0.147 | 1.633 | -0.057 | 0.720 |

| 4_ImC | 0.125 | 0.130 | 0.088 | -0.145 | 1.648 | -0.057 | 0.704 |

| Species | QPt | QC1 | BD[σ(Pt-CO2)] | ΔE(2) | |

| σ(Pt-CN^C^N)→σ*(Pt-CO2) | σ(Pt-CO2)→σ*(Pt-CN^C^N) | ||||

| 1_ImC | 0.235 | 0.495 | 0.558hPt + 0.830hC | 58.3 | 27.8 |

| 2_ImC | 0.237 | 0.494 | 0.540hPt + 0.842hC | 58.1 | 26.4 |

| 3_ImC | 0.244 | 0.495 | 0.538hPt + 0.843hC | 58.3 | 27.2 |

| 4_ImC | 0.260 | 0.497 | 0.535hPt + 0.845hC | 56.9 | 23.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).